Abstract

Background

The obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common respiratory pathogen, which has been found in a range of hosts including humans, marsupials and amphibians. Whole genome comparisons of human C. pneumoniae have previously highlighted a highly conserved nucleotide sequence, with minor but key polymorphisms and additional coding capacity when human and animal strains are compared.

Results

In this study, we sequenced three Australian human C. pneumoniae strains, two of which were isolated from patients in remote indigenous communities, and compared them to all available C. pneumoniae genomes. Our study demonstrated a phylogenetically distinct human C. pneumoniae clade containing the two indigenous Australian strains, with estimates that the most recent common ancestor of these strains predates the arrival of European settlers to Australia. We describe several polymorphisms characteristic to these strains, some of which are similar in sequence to animal C. pneumoniae strains, as well as evidence to suggest that several recombination events have shaped these distinct strains.

Conclusions

Our study reveals a greater sequence diversity amongst both human and animal C. pneumoniae strains, and suggests that a wider range of strains may be circulating in the human population than current sampling indicates.

Keywords: Chlamydia pneumoniae, Whole genome sequencing, Phylogenomics, Polymorphisms, Inclusion proteins, Polymorphic membrane protein, Inosine-monophosphate dehydrogenase, Recombination, Infection

Background

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an obligate intracellular bacterium and member of the Chlamydiaceae, a family of pathogens of higher eukaryotes with a distinct biphasic development cycle [1]. Whilst C. pneumoniae is primarily recognised as an aetiological agent of community acquired pneumonia and other respiratory diseases in humans [2], it has a broad host range encompassing both warm [3–5] and cold blooded animals [6, 7]. Members of the Chlamydiaceae are characterised by their compact genomes and highly conserved gene content [8]. C. pneumoniae has the greatest coding capacity of the Chlamydiaceae, with animal strains of C. pneumoniae having between 20Kbp (animal versus human C. pneumoniae) to almost 200Kbp (animal C. pneumoniae versus C. trachomatis serovar D) [9, 10] of extra nucleotide sequence. The additional coding capacity of C. pneumoniae is predominantly accounted for by the expansion of the polymorphic membrane protein (pmp) and inclusion membrane protein (inc) gene families [10–12], both of which are involved in the formation and maintenance of the chlamydial inclusion body, modulation of the host cell response [12, 13], as well as a large number of species-specific metabolic and hypothetical protein genes [9, 10, 14].

In addition to its description as a cause of human respiratory disease, C. pneumoniae has been implicated in a variety of human pathologies, including cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, ischaemic stroke, asthma and lung cancer [15–18]. Until recently, the majority of fully sequenced C. pneumoniae whole genomes were from strains that were isolated from respiratory pathologies [10, 19, 20], and demonstrated highly conserved nucleotide sequence content and gene order. Recently, several genomes from respiratory and cardiovascular strains were reported, as were whole genome sequences from atherosclerotic and Alzheimer’s C. pneumoniae strains, which allowed for comparison of strains isolated from different diseases, and demonstrated that only minor genetic differences were found between these strains [9, 21, 22].

A previous study examining the genetic diversity between human and animal C. pneumoniae suggested that a genetically distinct strain of human C. pneumoniae was present and circulating within Australian indigenous communities [23]. PCR analysis of a small number of selected target genes was performed on two respiratory strains isolated from Indigenous Australian patients in geographically separate regions [24, 25] and these were shown to have nucleotide sequence, that in some instances, placed these strains phylogenetically closer to animal strains of C. pneumoniae than those circulating in human populations in Australia and worldwide [23].

To further explore the genetic diversity of Australian human C. pneumoniae strains, we genome sequenced and performed comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of two human Australian indigenous C. pneumoniae strains and a third strain from an Australian Caucasian patient. In doing so, we (i) demonstrate that the indigenous Australian human strains form a separate clade branching earlier than other human C. pneumoniae strains; (ii) identify genetic markers unique to Australian indigenous and non-indigenous strains; and (iii) reveal evidence of limited recombination within C. pneumoniae strains from the greater human C. pneumoniae clade.

Results

Phylogenetic relationships in human C. pneumoniae reveal a distinct Australian indigenous clade predating European exploration of the continent

C. pneumoniae strains SH511, 1979 [24, 25] and WA97001 [26] were sequenced following capture of C. pneumoniae DNA using a set of species-specific SureSelectXT RNA probes [27–29]. Sequencing reads of C. pneumoniae WA97001, SH511 and 1797 were mapped to the reference genome, C. pneumoniae AR39, to check the efficacy of the SureSelectXT DNA captures. The genome of SH511 had the highest mean read depth of 1944×, followed by 1979, which had an average read depth of 1887×. The SH511 and 1979 assembled into 10 contigs and 31 contigs, respectively. In contrast, C. pneumoniae WA97001 genome had a significantly lower read depth of 15× and assembled into 104 contigs.

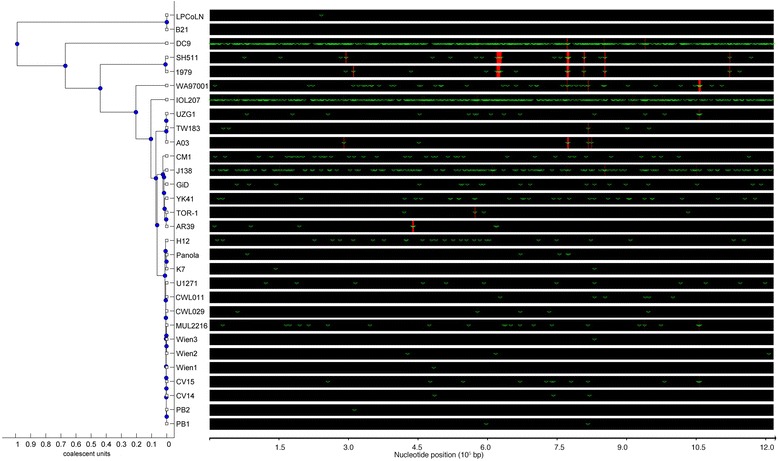

In order to determine the evolutionary and phylogenetic relationships between the Australian C. pneumoniae strains and those previously published, Bayesian and coalescent estimation methods were used to construct phylogenetic trees based on whole genome alignments of all human C. pneumoniae strains and the three published animal C. pneumoniae strains.

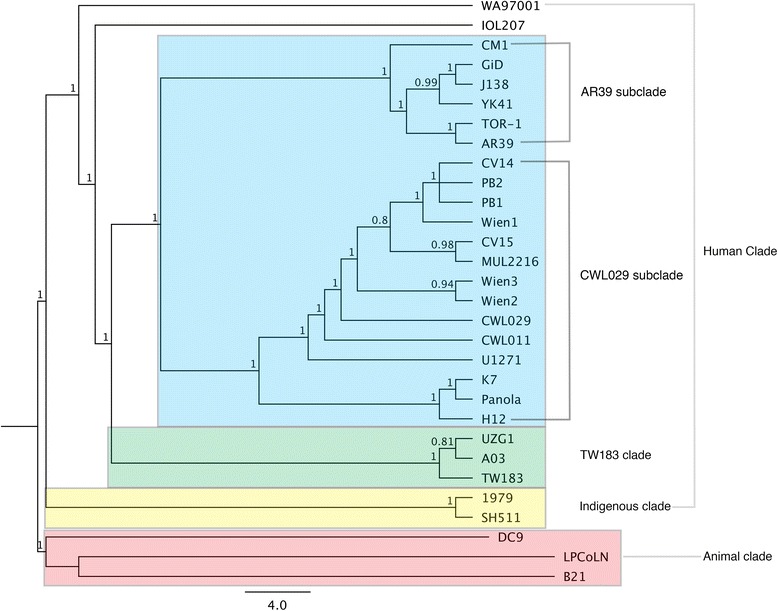

Percentage pairwise identities between indigenous and non-indigenous strains ranged from 98.4 to 98.8 %, whilst non-indigenous strains were 99.0 % or greater. Percentage identities of all strains used in the MrBayes analysis are outlined in Table 1. The resulting phylogenetic tree as represented in Fig. 1, demonstrates a clear demarcation of animal and human clades. The majority of non-indigenous human strains cluster into two clades: a large single clade that contains the AR39 and CWL029 subclades, and the smaller TW183 clade [22]. Interestingly, the two Australian indigenous C. pneumoniae strains, SH511 and 1979, formed their own clade which branched deepest from the main human C. pneumoniae grouping, but was also considerably distant to the animal C. pneumoniae clade. The Australian caucasian strain WA97001 and IOL207 (a strain isolated from a case of acute conjunctivitis) [30] formed their own separate branches in the main human C. pneumoniae clade.

Table 1.

Percentage nucleotide pairwise identities of all C. pneumoniae strains

| CM1 | GiD | TOR-1 | AR39 | YK41 | J138 | CV14 | PB2 | PB1 | CWL011 | Wien3 | CWL029 | U1271 | CV15 | Wien1 | K7 | Wien2 | MUL2216 | Panola | H12 | UZG1 | TW183 | A03 | WA97001 | 1979 | SH511 | IOL207 | DC9 | LPCoLN | B21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| GiD | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| TOR-1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| AR39 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| YK41 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| J138 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 97.9 | 94.8 | 94.8 | |

| CV14 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| PB2 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| PB1 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| CWL011 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| Wein3 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| CWL029 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.5 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 98.9 | 98.9 | 99.3 | 97.9 | 94.6 | 94.6 | |

| U1271 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| CV15 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| Wein1 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| K7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| Wein2 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| MUL2216 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| Panola | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 99.4 | 98 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| H12 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 99.2 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 99.1 | 97.8 | 94.4 | 94.4 | |

| UZG1 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 99.2 | 98.2 | 94.5 | 94.5 | |

| TW183 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 99.2 | 98.2 | 94.5 | 94.5 | |

| A03 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 98.9 | 98.9 | 99.1 | 97.9 | 94.5 | 94.4 | |

| WA97001 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.4 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.2 | 99.3 | 99.3 | 99.3 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 99 | 97.8 | 94.5 | 94.5 | |

| 1979 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.9 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.4 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.9 | 98.8 | 99.7 | 98.4 | 97.5 | 94.2 | 94.2 | |

| SH511 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.9 | 98.8 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.4 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.9 | 98.8 | 99.7 | 98.4 | 97.5 | 94.3 | 94.3 | |

| IOL207 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 99.1 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.1 | 99 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 94.3 | 94.3 | |

| DC9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 97.9 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 97.8 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 97.9 | 97.8 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.6 | 93.6 | 93.6 | |

| LPCoLN | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.8 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.6 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 94.5 | 94.5 | 94.5 | 94.2 | 94.3 | 94.3 | 93.6 | 100 | |

| B21 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.8 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.6 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 94.5 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 94.2 | 94.3 | 94.3 | 93.6 | 100 |

Fig. 1.

Chlamydia pneumoniae whole genome phylogeny constructed using MrBayes. Posterior probabilities >0.75 shown. Animal and human C. pneumoniae strains form the two major clades, with four distinct clades within the human C. pneumoniae tree

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of these deep-branching Australian indigenous human strains further, we determined the date of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the indigenous Australian C. pneumoniae strains by using BEAST [31] and ClonalFrame [32] coalescent estimation methods. BEAST analysis of indigenous and non-indigenous C. pneumoniae strains reveals an MRCA for indigenous strains at 1028, with a 95 % credibility interval between 996 and 1062 years. The mean substitution rate was determined to be 4.64 × 10−4 substitutions per site, per year. ClonalFrame analysis of indigenous and non-indigenous C. pneumoniae strains reveals a MRCA of 1425 for the indigenous strains, with a mean substitution rate of 2.36 × 10−5 per site per year. Though there are minor differences in the predicted MRCA and substitution rates between the two programs, which can be accounted for by the difference in their calculation methods [33], their estimates support similar evolutionary timelines and dates.

Identification of genetic markers that distinguish Australian indigenous strains from non-indigenous and animal C. pneumoniae strains

Using a PCR-based sequencing approach, we previously identified a series of potential genetic markers that could be used to distinguish Caucasian C. pneumoniae strains of different origins [23]. In the current study, fine-detailed genomic comparisons identified a series of novel genetic markers unique to the Australian indigenous strains, as well as unexpected sequence diversity in the DC9, WA97001 and IOL207 strains, which support their distinct phylogenetic positions in the C. pneumoniae tree.

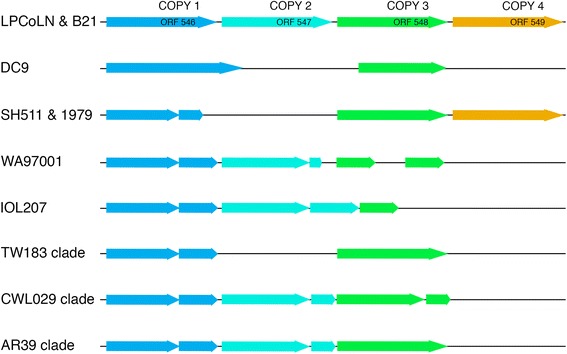

One of the most significant regions of genetic variation identified is located around four full-length IncA genes annotated in koala strain LPCoLN (CPK_ORF00546 to CPKORF00549 [9]); the differences of which support our phylogenetic results. The most notable finding in this region for the three Australian strains was the observation that the Australian indigenous strains contain a full-length homolog of CPK_ORF00549 sharing 99.4 % nucleotide pairwise identity to the koala homolog (Fig. 2). The presence of this gene in strains SH511 and 1979, and its significant sequence identity to the koala/bandicoot homolog supports the branching of the Australian indigenous clade earliest in the greater human C. pneumoniae phylogeny. Conversely, the Australian indigenous strains do not have a copy of CPK_ORF00547. This locus is also absent in the frog (DC9) strain and all strains within the TW183 clade, but is found in fragmented forms in all other human strains. Gene copy numbers and fragmentation with respect to the koala LPCoLN strain is represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The IncA gene expansion and recombination locus spanning homologs of CPK_ORF546 through 549 (LPCoLN locus numbering). Human and frog C. pneumoniae strains encode for either two or three copies with various levels of fragmentation between strains. Different clades within human C. pneumoniae encode for identical sequence length across this locus. The Australian indigenous strains are the only known human C. pneumoniae strains to encode for a CPK_ORF00549 homolog

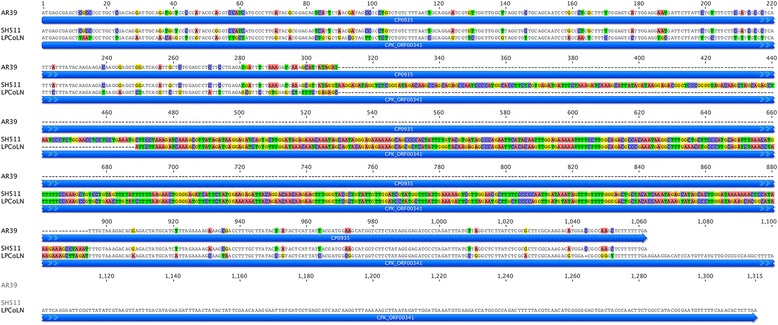

Another genetic marker unique to the Australian indigenous C. pneumoniae strains SH511 and 1979, was the presence of a 159 bp insertion in the gene homologous to koala CPK_ORF0341 (585 bp insertion compared to the AR39 homolog). Translation of the open reading frame suggests that this is a putative IncA gene which is full length in the koala strain. However, this gene is slightly truncated by 84 amino acids in indigenous strains (354 amino acids in length) and is only 154 amino acids in length in all other strains, including frog DC9 - due to a single nucleotide insertion 3’ which results in a frame shift (Fig. 3). Again, the large, strain-specific insertion and its sequence similarity to the koala homolog, supports the earliest branching of the Australian indigenous strains in the major human C. pneumoniae clade.

Fig. 3.

A large sequence insertion is specific to indigenous strains SH511 and 1979, within a putative IncA gene homologous to CPK_ORF341. This insertion encodes an almost full-length IncA homolog similar to that in the koala and bandicoot strains. Sequences at this locus for SH511 and 1979 are identical, and are shown compared to human strain AR39 and koala strain LPCoLN

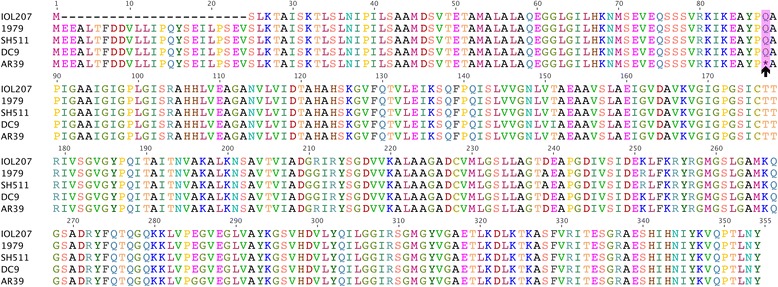

Sequence polymorphism has been described in the guaB/A-add operon in human and animal C. pneumoniae strains, with previous studies detailing that human C. pneumoniae strains encode fragmented inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase (guaB) genes [9]. In this study, we found that like the DC9 frog strain, the Australian indigenous strains and strain IOL207 encode for a full length, intact guaB gene. By comparison, all other human strains have a T/C transition at nucleotide position 262, which results in a stop codon (Fig. 4). Varied levels of sequence decay are evident in the Australian strains for GMP synthase (guaA) and adenosine deaminase (add). Deletions in both the guaA and add homologs of WA97001 result in truncations of these genes with loss of functional domains, whilst the Australian indigenous strains exhibit extensive sequence decay at this locus, resulting in the absence of guaA-add and the downstream hypothetical protein. Interestingly, whilst the entire guaA/B-add operon is absent in both koala and bandicoot strains, these genes are present in the frog strain DC9.

Fig. 4.

A single nucleotide transition in strains SH511, 1979, DC9 and IOL207 results in a full-length guaB gene, compared to fragmented genes in other human C. pneumoniae represented by AR39. The amino acid residue change at position 88 in strains IOL207, 1979, SH511 and DC9 is highlighted in the pink box, whilst the black arrow below the AR39 sequence indicates the guaB stop codon which is present in all other human C. pneumoniae strains. The IOL207 homolog is N-terminal truncated by 23 amino acids

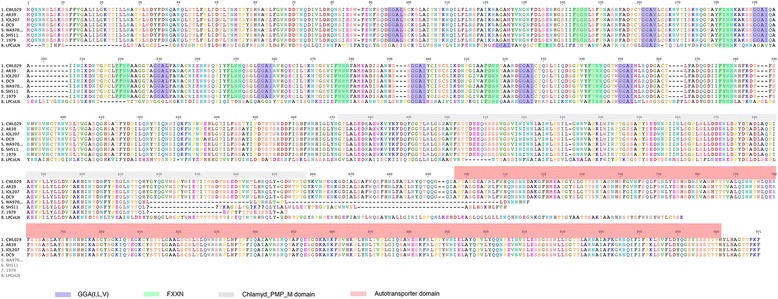

Various sequence polymorphisms are evident in the Australian C. pneumoniae strains for the pmpE/F4 gene. Both indigenous Australian strains 1979 and SH511 are truncated as the result of several deletions, whilst a single nucleotide insertion in WA97001 results in a frameshift causing truncation of this gene. This results in the loss of the C-terminal autotransporter domain for all three strains - however the mid-gene region encoding for nine FXXN and eight GGA(I,L,V) amino acid motifs are highly conserved across all the human C. pneumoniae strains (Fig. 5). Additionally, whilst both the koala and bandicoot homologs of this gene display extensive sequence polymorphism, the DC9 frog homolog is highly similar in sequence to the non-indigenous human pmpE/F4 and encodes for the full-length protein.

Fig. 5.

pmpE/F4 displays significant sequence polymorphism and decay in Australian C. pneumoniae strains SH511, 1979 and WA97001, resulting in truncated homologs of this protein. The frog DC9 homolog is similar in sequence to human C. pnuemoniae strains, unlike the koala and bandicoot strains which are highly polymorphic at this locus. The GGA(I,L,V) - FXXN amino acid repeat motifs characteristic to the polymorphic membrane protein gene family are highlighted, whilst sequence for the C-terminal autotransporter domain is clearly absent in SH511, 1979, WA97001 and LPCoLN strains

Australian indigenous strains demonstrate characteristic recombination profiles with only a few instances shared with non-indigenous strains

In addition to estimation of the MRCA and mean substitution rate, ClonalFrame was used to determine the recombination profiles and any shared recombination loci in C. pneumoniae. Our study found that the Australian indigenous strains SH511 and 1979 had a distinct and almost identical recombination and nucleotide substitution profile, with only a single difference in recombination locus between the two: SH511 between 296,000 and 298,000 bp and 1979 between 310,000 and 316,000 bp. Additionally, SH511 and 1979 share a strongly supported recombination event with the atherosclerosis strain A03 and to a lesser extent with Australian non-indigenous strain WA97001 between 778,000 and 784,000, which encompasses hypothetical protein and putative IncA genes. In comparing recombination profiles across the non-indigenous C. pneumoniae strains, the Australian WA97001 strain shares a single strong recombination event with A03 and TW183 between 823,600 and 827,100 bp, which encompasses putative IncA genes. Several nucleotide substitution events are shared amongst the various C. pneumoniae strains, though the highest number of nucleotide substitutions occur in strains J138, IOL207 and DC9 (Fig. 6). A Phi test for recombination was performed on the C. pneumoniae whole genome alignment using SplitsTree4 [34], which found a total of 16,329 informative sites and statistically significant evidence of recombination (p = 5.538 × 10−4).

Fig. 6.

Whole genome recombination mappings as predicted by ClonalFrame coalescent methods. Red bars represent recombination events and green ticks represent mutations. Strains SH511 and 1979 share almost identical recombination profiles, with non-indigenous human C. pneumoniae and the DC9 frog strain sharing recombination events at discrete loci. The predicted whole genome phylogeny based on recombination and mutation events is consistent with the groupings demonstrated using BEAST and MrBayes prediction methods

Discussion

C. pneumoniae has been described as an ancient pathogen, with the broadest host range of any member of the Chlamydiaceae [35]. Comparative whole genome studies examining the differences between human respiratory [20], non-respiratory [9, 21, 22, 36] and animal C. pneumoniae strains [9] all demonstrate a highly conserved core genome with subtle strain-specific differences. We previously characterized some of these subtle differences using a PCR/sequencing approach and revealed that the two human Australian indigenous human strains sequenced in this study shared genetic markers with the koala LPCoLN strain [9] for some genes and away from other human non-Australian indigenous strains [23]. To further explore the relationship of Australian indigenous and non-indigenous human strains, in the current study, we obtained whole genome sequences for three Australian respiratory strains (SH511, 1979 and WA97001) and performed comparative analyses to further understand their relationship to other previously characterized human and animal C. pneumoniae strains.

Using a variety of phylogenomic tools, our analysis suggests that the Australian C. pneumoniae indigenous strains form a phylogenetically distinct clade away from all other human C. pneumoniae strains sequenced to date. This is substantiated by unique sequence polymorphisms and recombination profiles associated with the Australian indigenous strains. In contrast to previous phylogenies constructed using sequenced PCR fragments, which alternately placed the Australian indigenous strains within either the human or animal branches of the tree [23], the use of whole genome sequences gives a more accurate description of the position of these strains within the greater C. pneumoniae evolutionary tree. Fine-detailed genomic comparisons also revealed several novel genetic markers in Australian indigenous human C. pneumoniae strains, beyond those previously identified in previous PCR-based studies [23].

The Australian indigenous strains demonstrate a copy number incongruity within the CPK_ORF00546 to CPK_ORF00549 IncA gene family. This gene family expansion was first described in the koala LPCoLN strain [9] with human C. pneumoniae strains exhibiting variable levels of gene fragmentation and gene loss at this locus. The Australian indigenous strains are unique in that they specifically encode a homolog to CPK_ORF00549: to date, SH511 and 1979 are the only human C. pnuemoniae strains that encode for this homolog. Previous studies have shown that C. pneumoniae encodes a far larger number of IncA and putative IncA proteins compared to other Chlamydiae [11, 12], many of which are species-specific. Strong recombination signals were also detected within several human C. pneumoniae strains at loci encoding IncA proteins, which suggests that recombination may account for the expanded number of IncA proteins in C. pneumoniae.

One of the more subtle genetic differences observed between the strains analysed was the maintenance of a partial purine biosynthesis pathway encoded by guaA/B-add [10]. Previous studies demonstrated that the guaB gene is fragmented in human C. pneumoniae strains [14], however in this study we demonstrate that strains DC9, SH511 and 1979 encode for an intact guaB gene. Given that the Australian indigenous strains do not encode guaA-add, it is likely that the sequence for guaB was a recent acquisition from a strain most similar to DC9. Interestingly, in contrast to the koala and bandicoot strains where the entire guaA/B-add operon is absent [9, 37], the frog DC9 strain encodes guaA/B-add genes, with >99.5 % nucleotide pairwise identity to all human C. pneumoniae strains, with the exception of the three Australian strains. Studies in both C. psittaci and Chlamydia caviae have found evidence for horizontal gene transfer of the guaA/B-add operon between different chlamydial strains and species [33, 38], lending further support for the recent acquisition of guaB by the Australian indigenous strains. Whilst it is unclear what effect the presence or absence of guaA/B-add has on the growth and virulence of human and animal C. pneumoniae strains, a previous study examining the effect of mutations in the Chlamydia muridarum plasticity zone suggest that 5’ point mutations of guaB and add result in attenuated virulence in vivo, whilst guaA/B-add mutations do not affect the growth characteristics of these strains in vitro [39]. These observations are similar to those reported for the growth and virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Francisella tularensis guaA/B +/− strains in vitro and in vivo [40, 41].

In order to further explore the evolutionary relationships of the Australian indigenous C. pneumoniae strains, BEAST and ClonalFrame analyses predicted that these strains had an MRCA of 1028 and 1425, respectively. Both of these estimations pre-date the known colonization of the Australian continent by Europeans by several hundred years, but are virtually identical to the previously estimated MRCA for strains within the non-indigenous clade at 1151 +/− 20 years [21].

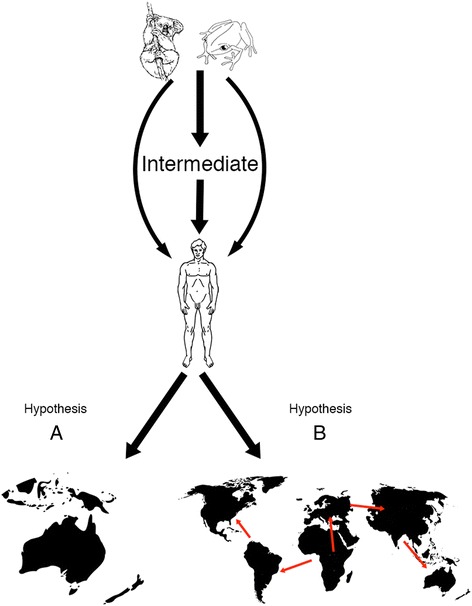

Given this new evidence and our previous data suggesting that C. pneumoniae strains in humans likely originated from a zoonotic event(s) [9, 23], it is interesting to speculate on the origin of these indigenous human C. pneumoniae strains. Two possible evolutionary hypotheses to explain the deep-branching of these strains are proposed: (A), the Australian indigenous strains have evolved from a separate zoonotic transmission event, or alternate intermediate strain, to that of the other human C. pneumoniae strains. These ancestral strains were subsequently endemic on the Australian continent and continued to evolve in isolation to the non-indigenous C. pneumoniae strains. Alternatively (B), all human C. pneumoniae strains disseminated from a common intermediate strain, resultant from a single zoonotic event several thousand years ago, and evolved separately in response to their different ecological niches (Fig. 7). Our findings provide support for both hypotheses.

Fig. 7.

Evolutionary hypothesis model describing two alternate hypotheses for the characteristic deep-branching of the Australian indigenous strains SH511 and 1979. In hypothesis A, Australian indigenous strains evolved from a separate zoonotic (or intermediate) transmission event, and continued to evolve in isolation from non-indigenous human C. pneumoniae strains. In hypothesis B, all human C. pneumoniae strains disseminated from a single zoonotic (or intermediate) transmission event and evolved separately in response to differing ecological functions

With respect to hypothesis (A), estimations from both BEAST and ClonalFrame analyses indicate an MRCA for the indigenous strains several hundred years prior to the first reported visitation of the Australian continent by Dutch or British explorers [42, 43]. This suggests the possibility that an endemic strain similar to our strains may have been circulating within the indigenous population prior to the arrival of European colonisation. Given the sequence similarity of the indigenous strains to the koala and bandicoot C. pneumoniae strains at several key loci (the absence of guaA-add, polymorphisms in pmpE/F4 and the IncA gene expansion), as well as those previously described [23], it is possible that a strain similar to these animal strains was zoonotically transmitted to humans on the Australian continent. Hunter-gatherer communities lived in close proximity and interacted with wild animals throughout human history, which would facilitate the transmission of a pathogen to humans. Serological studies examining the prevalence of chlamydial infection in remote indigenous communities have reported levels of almost 60 % adult female seroprevalence to C. pneumoniae [24]. Several species of native Australian marsupials [9, 23, 37, 44] as well as an amphibian [7, 23] have been demonstrated to have genetic sequence similar to that of the koala LPCoLN strain. Studies have shown that koala and bandicoot C. pneumoniae strains readily infect various human-derived cell lines [3, 45, 46], and evidence for human carotid artery and PBMC strains which are genotypically similar to the koala strain at the ompA and yge-urk intergenic spacer loci have been reported [47]. If the distinct phylogenetic clustering of SH511 and 1979 is a result of a separate zoonotic event to that of the main human C. pneumoniae lineage, then it is likely that the animal strain that they have evolved from is still unknown, and probably more similar to the frog DC9 strain in sequence and nucleotide content.

The alternate hypothesis (B), is that all human C. pneumoniae strains disseminated from a single zoonotic event (presumably in Americas or Europe) and then differentiated along separate evolutionary paths, dependent on their geographical and disease niche. The estimated MRCA for indigenous and non-indigenous human strains differs by less than 200 years, whilst their phylogenetic distance is significantly closer, compared to the animal strains. The overall nucleotide pairwise identity of the Australian indigenous strains is more similar to other human strains of C. pneumoniae, even when significant similarities to animal strains at discrete loci are included. There are two possible mechanisms to explain the dissemination of these particular strains: Firstly - various strains of C. pneumoniae were circulating in the worldwide human population approximately 40 thousand years ago, which is well prior to the colonisation of the Australian continent [48], and that one or some of these strains came to the continent with the arrival of the indigenous peoples. This would account for the characteristic sequence polymorphisms present in the SH511 and 1979 but not in other human C. pneumoniae strains. Alternately - the worldwide variation in human C. pneumoniae is far greater than has yet been determined, and several strain types were introduced to the Australian continent with European colonisation. This in turn accounts for the overall sequence similarity of the SH511 and 1979 strains to non-indigenous human C. pneumoniae strains, in particular WA97001, with which it shares a considerable number of SNPs, as opposed to the Australian marsupial strains, LPCoLN and B21. In both cases, genetically distinct subpopulations of C. pneumoniae could have spread throughout, and evolved in isolation within the indigenous Australian population. Genotypic variation amongst concurrent populations of monomorphic bacteria resulting from selective sweeps is well documented in both Chlamydia [49, 50] and other bacterial species [51]. The differentiation of the main human C. pneumoniae lineage from both the indigenous and animal lineages could be explained by adaptation of these strains to selective and antigenic pressure as a result of extensive antibiotic treatment regimes [52].

Whilst our study provides evidence for a phylogenetically and genetically distinct branch of human C. pneumoniae, these inferences are made on a relatively small sample size, taken from two individuals from remote communities in the same state, over two decades ago. It is highly unlikely that sampling from the same remote communities and wider ranging communities will uncover the same strains as documented in this study; given the increased interaction between members of remote indigenous communities and neighbouring townships, as well as expanded antibiotic treatment regimes for a range of bacterial infections, including Chlamydia, within these communities. It is also possible that greater sampling for C. pneumoniae in countries outside Australia would uncover a wider range of strains, some of which may be similar to those described in this study.

Conclusion

In summary, we used a combination of comparative genomic and phylogenetic methods to determine the evolutionary position of three Australian human C. pneumoniae strains within the greater C. pneumoniae tree. Our study demonstrated a phylogenetically distinct human C. pneumoniae clade consisting of two Australian indigenous strains, that branched earlier in the human C. pneumoniae evolutionary tree with an estimated MRCA predating the exploration and colonisation of the continent by European settlers by several hundred years. Our findings indicate that a unique strain of C. pneumoniae evolved in isolation within the Australian indigenous population, as evidenced by the unique recombination profiles and distinct sequence polymorphisms in these strains. This suggests that a far greater level of sequence diversity is present amongst human and animal C. pneumoniae strains than previously surmised, and that further sampling of C. pneumoniae isolates from wider geographical regions may uncover strains which have evolved similarly to this unique C. pneumoniae clade.

Methods

Description of Chlamydia pneumoniae strains, cell culturing and DNA purification

Three Australian C. pneumoniae cultured isolates (WA97001, SH511 and 1979) were used for comparative analyses in this study. The non-indigenous isolate WA97001 is a clinical nasopharyngeal isolate from Western Australia [26] whilst isolates SH511 and 1979 are indigenous Australian isolates from two separate patients in remote Northern Territory communities [24, 25].

Isolate WA97001 was propagated on McCoy cells in T75 flasks for five passages, based on a previously described method [46]. Infected cells were pooled and semi-purified using a sonication and centrifugation method prior to passage. The final semi-purified product was stored in an equal volume of SPG media [53]. 500 μl of this semi-purified material was used for DNA extraction. Isolates SH511 and 1979 were extracted from non-viable archival culture material [23]; 500 μl of each isolate was used for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction was performed using phenol:chloroform:IAA, based on a well described method [54], with the addition of 2 μl of glycogen prior to ethanol precipitation at −20 °C overnight. Precipitated DNA was dissolved in 50 μl of TE buffer. 500 ng of extracted DNA was used to perform pan-Chlamydiales 16S rRNA [55] and C. pneumoniae specific RpoB [56] PCR to confirm the presence of C. pneumoniae DNA, and 500 ng of stock DNA was electrophoresed on a 0.8 % TBE agarose gel to confirm high molecular weight DNA. Each DNA extraction yielded greater than 2 μg of high molecular weight genomic DNA, which was used for sequence capture and Illumina HiSeq 2500 whole genome sequencing at the Institute for Genome Sciences, Baltimore, Maryland.

Sequence capture, whole genome sequencing and assembly

Sequence capture was performed on total DNA extracted from WA97001, SH511 and 1979 with Agilent SureSelectXT DNA capture probes designed to C. pneumoniae reference strain AR39, using a hybridisation capture and amplification process [27–29]. Captured and amplified products were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform, resulting in paired-end 100 base pair reads. Read quality was checked with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and genomes were assembled de novo using SPAdes 3.0.0 with SPAdes 3.0.0 with k-mer values set to of 15, 21, 33, 51 and 71 [57]. All assembled contigs were aligned to the reference C. pneumoniae AR39 genome using BLASTn to remove non-chlamydial contigs. Concatenated genome contigs were annotated using the RAST pipeline [58] and manually curated using ARTEMIS [59]. Total read depth of WA97001, SH511 and 1979 was calculated by mapping the raw reads to complete genome of C. pneumoniae AR39 using the BWA-backtrack algorithm with BWA aligner [60]. Raw reads were also mapped to the complete genome of C. pneumoniae LPCoLN for comparison. The BWA parameters used include the number of differences allowed between the reference and query set at 0.04 and the number of differences allowed in the seed was 2. The maximum number of gaps allowed in the alignment was 1 and the gap penalty was set at 11.

Phylogenetic and recombination analyses

De novo assemblies and readmapped assembled consensus sequences for WA97001, SH511 and 1979 were aligned to the existing human C. pneumoniae whole genome sequences [10, 19–22, 61] and animal C. pneumoniae strains LPCoLN, B21 and DC9 [9, 22, 37] in Geneious 6.1.8 [62] using the MAFFT plugin implementation [63]. Coverage analyses for readmapped assemblies and manual curation of annotated genomes was performed using ARTEMIS [59].

Phylogenetic analyses were performed on whole genome alignments, with the LPCoLN koala [9] C. pneumoniae strain indicated as an outlier. Whole genome alignments were also filtered for poorly aligned and gap regions using Gblocks 0.91b [64]. Mid-point rooted trees were constructed with the MrBayes plugin [65] in Geneious, utilising a Jukes-Cantor substitution model with with four Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains and 1.1 million cycles, sampled every 1000 generations and the first 10,000 trees discarded as burn-in. Estimates of strain evolution over time were performed on whole genome alignments using the BEAST package [31]. Indigenous, non-indigenous and animal isolates were defined in separate taxon sets and a GTR nucleotide substitution model was employed. MRCA priors were set at a normal distribution with a mean of 95.2 +/− 7.4 [66]. MCMC chain length was set to 5 × 107 to ensure effective sample sizes were sufficient for strong posterior distribution statistics. ClonalFrame [67] was used to determine homologous recombination within C. pneumoniae genomes, and progressive MAUVE [68] was used to generate the input alignments. Three successive runs of ClonalFrame were performed on the whole genome alignment, each with 20,000 iterations and 10,000 of these discarded as burn-in. The three runs were checked for convergence and their trees combined for analysis. An additional Phi test for recombination was performed in SplitsTree4 [34] using the whole genome alignment generated by MAFFT in Geneious.

The accession numbers for the C. pneumoniae whole genome sequences used in the comparative analyses and phylogenies are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

C. pneumoniae strain designations and accession numbers

| Strain designation | Accession number | Reference/s |

|---|---|---|

| A03 | SRP056807 | [15, 21] |

| AR39 | NC_002179.2 | [19] |

| B21 | NZ_AZNB01000000 | [37] |

| CM1 | ERS640705 | [22] |

| CV14 | ERS640706 | [22] |

| CV15 | ERS640707 | [22] |

| CWL011 | ERS640708 | [22] |

| CWL029 | NC_000922.1 | [10] |

| DC9 | ERS640710 | [22] |

| GiD | ERS640711 | [22] |

| H12 | ERS640712 | [22] |

| IOL207 | - | [22] |

| J138 | NC_002491.1 | [20] |

| K7 | ERS640713 | [22] |

| LPCoLN | NC_017285.1 | [9] |

| MUL2216 | ERS640714 | [22] |

| Panola | ERS640715 | [22] |

| PB1 | ERS640716 | [22] |

| PB2 | ERS640717 | [22] |

| SH511 | SRP061961 | [25] This study |

| TOR-1 | SRP056806 | [16, 21] |

| TW183 | NC_005043.1 | Unpublished |

| U1271 | ERS640718 | [22] |

| UZG1 | ERS640719 | [22] |

| WA97001 | SRP062032 | [26] This study |

| Wien1 | ERS640720 | [22] |

| Wien2 | ERS640721 | [22] |

| Wien3 | ERS640722 | [22] |

| YK41 | ERS640723 | [22] |

| 1979 | SRP062031 | [25] This study |

Description of polymorphic hotspots in C. pneumoniae whole genome alignments

De novo and readmapping assemblies were used to construct whole genome alignments with previously described human and animal C. pneumoniae whole genomes in MAFFT [63] in Geneious [62]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions were detected using the Variations/SNPs tool in Geneious, and larger scale differences were detected via manual scanning of the genome alignment. Sequence for genes which appeared to have significant deletions or insertions were manually extracted and sequence run against the BLAST [69] database to determine closest homologs. Sequences were translated and searched against the SMART database [70] to predict any changes in functional domains or protein motifs.

Availabilty of supporting data

The WA97001, SH511 and 1979 whole genome sequencing projects can be found on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioProject under accession numbers [Bioproject:PRJNA291806, Bioproject:PRJNA291802 and Bioproject:PRJNA291805] with reads deposited in the Short Reads Archive under accession numbers [SRA:SRR2144962, SRA:SRR2144961 and SRA:SRR2144960] respectively.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Queensland University of Technology and Menzies School of Health Research, Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethics approval for the collection and analysis of strains SH511, 1979 and WA97001 were obtained from Queensland University of Technology, Menzies School of Health Research and the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Val Asche, Susan Hutton and the Menzies School of Health in the Northern Territory for their initial work in isolating the Australian indigenous strains. We would also like to thank Avinash Kollipara for his assistance with cell culture propagation of the WA97001 strain. This work was funded by an Australian Government NHMRC grant (#APP1004666). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- bp

base pair

- pmp

polymorphic membrane protein

- inc

inclusion protein

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- MRCA

most recent common ancestor

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- guaA

guanine monophosphate synthetase

- guaB

inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase

- add

adenosine deaminase

- AA

amino acid

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ER performed the cell culture, DNA purification, sequence alignments, comparative genomics and phylogenetic analyses, data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. NB performed the assembly and read mapping of the genomes and assisted with drafting the manuscript. MH and GM performed the whole genome sequencing and assisted with data analysis. WH and AP aided in data interpretation and assisted with drafting the manuscript. PT conceived of the study, participated in the design and drafting of the manuscript, aided in data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Eileen Roulis, Email: eileen.roulis@qut.edu.au.

Nathan Bachmann, Email: nbachman@usc.edu.au.

Michael Humphrys, Email: MHumphrys@som.umaryland.edu.

Garry Myers, Email: Garry.Myers@uts.edu.au.

Wilhelmina Huston, Email: w.huston@qut.edu.au.

Adam Polkinghorne, Email: apolking@usc.edu.au.

Peter Timms, Email: ptimms@usc.edu.au.

References

- 1.Horn M, Collingro A, Schmitz-Esser S, Beier CL, Purkhold U, Fartmann B, et al. Illuminating the evolutionary history of Chlamydiae. Science. 2004;304(5671):728–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1096330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn DL, Azenabor AA, Beatty WL, Byrne GI. Chlamydia pneumoniae as a respiratory pathogen. Front Biosci. 2002;7:E66–E76. doi: 10.2741/hahn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutlin A, Roblin PM, Kumar S, Kohlhoff S, Bodetti T, Timms P, et al. Molecular characterization of chlamydophila pneumoniae isolates from western barred bandicoots. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56(3):407–417. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storey C, Lusher M, Yates P, Richmond S. Evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae of nonhuman origin. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2621–2626. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girjes AA, Carrick FN, Lavin MF. Remarkable sequence relatedness in the DNA encoding the major outer membrane protein of chlamydia psittaci (koala type I) and chlamydia pneumoniae. Gene. 1994;138(1):139–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90796-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodetti TJ, Jacobson E, Wan C, Hafner L, Pospischil A, Rose K, et al. Molecular evidence to support the expansion of the host range of chlamydophila pneumoniae to include reptiles as well as humans, horses, koalas and amphibians. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2002;25(1):146–152. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger L, Volp K, Mathews S, Speare R, Timms P. Chlamydia pneumoniae in a free-ranging giant barred frog (Mixophyes iteratus) from Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(7):2378–2380. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2378-2380.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collingro A, Tischler P, Weinmaier T, Penz T, Heinz E, Brunham RC, et al. Unity in variety-the pan-genome of the chlamydiae. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(12):3253–3270. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers GSA, Mathews SA, Eppinger M, Mitchell C, O’Brien KK, White OR, et al. Evidence that human chlamydia pneumoniae was zoonotically acquired. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(23):7225–7233. doi: 10.1128/JB.00746-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalman S, Mitchell W, Marathe R, Lammel C, Fan L, Hyman RW, et al. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nat Genet. 1999;21(4):385–389. doi: 10.1038/7716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lutter EI, Martens C, Hackstadt T. Evolution and conservation of predicted inclusion membrane proteins in chlamydiae. Comp Funct Genomics. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehoux P, Flores R, Dauga C, Zhong GM, Subtil A. Multi-genome identification and characterization of Chlamydiae-specific type III secretion substrates: the Inc proteins. BMC Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimwood J, Olinger L, Stephens RS. Expression of Chlamydia pneumoniae polymorphic membrane protein family genes. Infect Immun. 2001;69(4):2383–2389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2383-2389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell CM, Hovis KM, Bavoil PM, Myers GSA, Carrasco JA, Timms P. Comparison of koala LPCoLN and human strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae highlights extended genetic diversity in the species. BMC Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez JA, Ahkee S, Summersgill JT, Ganzel BL, Ogden LL, Quinn TC, et al. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(12):979–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreses-Werringloer U, Bhuiyan M, Zhao YH, Gerard HC, Whittum-Hudson JA, Hudson AP. Initial characterization of Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae cultured from the late-onset Alzheimer brain. Int J Med Microbiol. 2009;299(3):187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasan ZN. Association of chlamydia pneumoniae serology and ischemic stroke. South Med J. 2011;104(5):319–321. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182114954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhan P, Suo LJ, Qian QA, Shen XK, Qiu LX, Yu LK, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(5):742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, et al. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(6):1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirai M, Hirakawa H, Kimoto M, Tabuchi M, Kishi F, Ouchi K, et al. Comparison of whole genome sequences of Chlamydia pneumoniae J138 from Japan and CWL029 from USA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(12):2311–2314. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roulis E, Bachmann NL, Myers GS, Huston W, Summersgill J, Hudson A, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of human Chlamydia pneumoniae isolates from respiratory, brain and cardiac tissues. Genomics. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinmaier T, Hoser J, Eck S, Kaufhold I, Shima K, Strom TM, et al. Genomic factors related to tissue tropism in Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell CM, Hutton S, Myers GSA, Brunham R, Timms P. Chlamydia pneumoniae is genetically diverse in animals and appears to have crossed the host barrier to humans on (at least) Two occasions. PLoS Pathog. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asche LV, Hutton SI, Douglas FP. Serological evidence of the three chlamydial species in an aboriginal community in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 1993;158(9):603–604. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutton S, Dodd H, Asche V. C. pneumoniae successfully isolated. Today’s Life Science. 1993;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coles KA, Timms P, Smith DW. Koala biovar of Chlamydia pneumoniae infects human and koala monocytes and induces increased uptake of lipids in vitro. Infect Immun. 2001;69(12):7894–7897. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7894-7897.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gnirke A, Melnikov A, Maguire J, Rogov P, LeProust EM, Brockman W, et al. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotech. 2009;27(2):182–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christiansen MT, Brown AC, Kundu S, Tutill HJ, Williams R, Brown JR, et al. Whole-genome enrichment and sequencing of Chlamydia trachomatis directly from clinical samples. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachmann NL, Sullivan MJ, Jelocnik M, Myers GSA, Timms P, Polkinghorne A. Culture-independent genome sequencing of clinical samples reveals an unexpected heterogeneity of infections by Chlamydia pecorum. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1128/JCM.03534-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forsey T, Darougar S. Acute conjunctivitis caused by an atypical chlamydial strain: Chlamydia IOL 207. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(6):409–411. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.6.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012 doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175(3):1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Read TD, Joseph SJ, Didelot X, Liang B, Patel L, Dean D. Comparative analysis of Chlamydia psittaci genomes reveals the recent emergence of a pathogenic lineage with a broad host range. MBio. 2013 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00604-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(2):254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roulis E, Polkinghorne A, Timms P. Chlamydia pneumoniae: modern insights into an ancient pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodetti TJ, Timms P. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA and antigen in the circulating mononuclear cell fractions of humans and koalas. Infect Immun. 2000;68(5):2744–2747. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2744-2747.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roulis E, Bachmann N, Polkinghorne A, Hammerschlag M, Kohlhoff S, Timms P. Draft genome and plasmid sequences of chlamydia pneumoniae strain B21 from an Australian endangered marsupial, the western barred bandicoot. Genome Announcements. 2014 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01223-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Read TD, Myers GSA, Brunham RC, Nelson WC, Paulsen IT, Heidelberg J, et al. Genome sequence of Chlamydophila caviae (Chlamydia psittaci GPIC): examining the role of niche specific genes in the evolution of the Chlamydiaceae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(8):2134–2147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajaram K, Giebel AM, Toh E, Hu S, Newman JH, Morrison SG, et al. Mutational analysis of the Chlamydia muridarum plasticity zone. Infect Immun. 2015 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jewett MW, Lawrence KA, Bestor A, Byram R, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. GuaA and GuaB Are Essential for Borrelia burgdorferi Survival in the Tick-Mouse Infection Cycle. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(20):6231–6241. doi: 10.1128/JB.00450-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santiago AE, Mann BJ, Qin A, Cunningham AL, Cole LE, Grassel C, et al. Characterization of Francisella tularensis Schu S4 defined mutants as live-attenuated vaccine candidates. Pathog Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heeres JEJE, Genootschap KNA. The part borne by the Dutch in the discovery of Australia 1606–1765. Luzac: Leiden : E.J. Brill; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett S. Australian discovery and colonisation. Part II. Sydney: Hanson & Bennett; 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bodetti TJ, Viggers K, Warren K, Swan R, Conaghty S, Sims C, et al. Wide range of Chlamydiales types detected in native Australian mammals. Vet Microbiol. 2003;96(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chacko A, Barker CJ, Beagley KW, Hodson MP, Plan MR, Timms P, et al. Increased sensitivity to tryptophan bioavailability is a positive adaptation by the human strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/mmi.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell CM, Mathews SA, Theodoropoulos C, Timms P. In vitro characterisation of koala chlamydia pneumoniae: morphology, inclusion development and doubling time. Vet Microbiol. 2009;136(1–2):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cochrane M, Walker P, Gibbs H, Timms P. Multiple genotypes of Chlamydia pneumoniae identified in human carotid plaque. Microbiology. 2005;151:2285–2290. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen M, Guo X, Wang Y, Lohmueller KE, Rasmussen S, Albrechtsen A, et al. An aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia. Science. 2011;334(6052):94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1211177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Millman K, Black CM, Johnson RE, Stamm WE, Jones RB, Hook EW, et al. Population-based genetic and evolutionary analysis of chlamydia trachomatis urogenital strain variation in the United States. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(8):2457–2465. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2457-2465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunes A, Nogueira PJ, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP. Adaptive evolution of the chlamydia trachomatis dominant antigen reveals distinct evolutionary scenarios for B- and T-cell epitopes: worldwide survey. PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro BJ, Friedman J, Cordero OX, Preheim SP, Timberlake SC, Szabo G, et al. Population genomics of early events in the ecological differentiation of bacteria. Science. 2012;336(6077):48–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1218198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandoz KM, Rockey DD. Antibiotic resistance in Chlamydiae. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(9):1427–1442. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warford AL, Rekrut KA, Levy RA, Drill AE. Sucrose phosphate glutamate for combined transport of chlamydial and viral specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;81(6):762–764. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/81.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambrook J, Russell DW, Irwin N. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Everett KDE, Bush RM, Andersen AA. Emended description of the order Chlamydiales, proposal of Parachlamydiaceae fam. nov. and Simkaniaceae fam. nov., each containing one monotypic genus, revised taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, including a new genus and five new species, and standards for the identification of organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:415–440. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell LA, Perez Melgosa M, Hamilton DJ, Kuo CC, Grayston JT. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(2):434–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.434-439.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(10):944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grayston JT, Kuo CC, Campbell LA, Wang SP. Chlamydia pneumoniae sp. nov. for Chlamydia sp. Strain TWAR. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1989;39(1):88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma KÄ, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(4):540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson DE, Taylor LD, Shannon JG, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, McClarty G, et al. Phenotypic rescue of Chlamydia trachomatis growth in IFN-gamma treated mouse cells by irradiated Chlamydia muridarum. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(9):2289–2298. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rattei T, Ott S, Gutacker M, Rupp J, Maass M, Schreiber S, et al. Genetic diversity of the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydophila pneumoniae by genome-wide analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms: evidence for highly clonal population structure. BMC Genomics. 2007 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56(4):564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. ProgressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(11):5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]