Abstract

Background

Although Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) is the dominant gastrointestinal pathogen, the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying H.pylori-related diseases have not been fully elucidated. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified in eukaryotic cells, many of which play important roles in regulating biological processes and pathogenesis. However, the expression changes of lncRNAs in human infected by H.pylori have been rarely reported. This study aimed to identify the dysregulated lncRNAs in human gastric epithelial cells and tissues infected with H.pylori.

Methods

The aberrant expression profiles of lncRNAs and mRNAs in GES-1 cells with or without H.pylori infection were explored by microarray analysis. LncRNA-mRNA co-expression network was constructed based on Pearson correlation analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG Pathway analyses of aberrantly expressed mRNAs were performed to identify the related biological functions and pathologic pathways. The expression changes of target lncRNAs were validated by qRT-PCR to confirm the microarray data in both cells and clinical specimens.

Results

Three hundred three lncRNAs and 565 mRNAs were identified as aberrantly expressed transcripts (≥2 or ≤0.5-fold change, P < 0.05) in cells with H.pylori infection compared to controls. LncRNA-mRNA co-expression network showed the core lncRNAs/mRNAs which might play important roles in H.pylori-related pathogenesis. GO and KEGG analyses have indicated that the functions of aberrantly expressed mRNAs in H.pylori infection were related closely with inflammation and carcinogenesis. QRT-PCR data confirmed the expression pattern of 8 (n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, LINC00473, XLOC_005517, LINC00152, XLOC_13370, and n408024) lncRNAs in infected cells. Additionally, four down-regulated (n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, and LINC00473) lncRNAs were verified in H.pylori-positive gastric samples.

Conclusion

Our study provided a preliminary exploration of lncRNAs expression profiles in H.pylori-infected cells by microarray. These dysregulated lncRNAs might contribute to the pathological processes during H.pylori infection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12920-015-0159-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Long non-coding RNAs, Helicobacter pylori, Microarray, Expression profile

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) is a human-specific gastric bacterium that colonizes more than half of the world’s population. The infection of this pathogen is thought to be persisted for lifetime without treatment. The pathogen can evoke both innate and adaptive immune responses. However, immune system fails to eradicate this causative agent, which can lead to the gastric mucosa pathological changes [1]. The clinical outcome, ranging from chronic gastritis to peptic ulcers, even to cancer or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, is caused by multiple interior genetic dysregulation in combination with various environmental factors and bacterial virulence factors [2, 3].

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a little-understood class of transcribed RNA molecules, exceeding 200 nucleotides in length but have no significant protein-coding capacity, which are identified as key regulators in various biological functions.[4]. It has been known that lncRNAs are linked to epigenetic regulation, body development, and physiological responses [5–7]. Moreover, recently evidences have revealed that remarkably expressed lncRNAs are correlated with human diseases, such as neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases, infectious diseases and various cancers [8, 9]. The discovery of lncRNAs and investigation on their functions in regulatory networks could lead us to a deeper comprehension of pathogenesis. Recently, the researchers have made some achievements in understanding lncRNAs. However, the expression patterns and functions of lncRNAs in cells infected by H. pylori have been seldom reported. Considering the wide range of roles that lncRNAs play in cellular and molecular regulatory processes, we do believe that it is possible that the aberrant expression of some lncRNAs might contribute to the H.pylori-infection associated disorders and diseases.

In this study, we identified the expression patterns of lncRNAs in H.pylori-infected gastric epithelial cell GES-1 via microarray analysis. LncRNA-mRNA co-expression networks were built based on Pearson correlation analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway analysis were performed to analyze lncRNA related coding genes involved in distinguishable biological responses. Several aberrantly expressed lncRNAs were confirmed by qRT-PCR in cells and gastric mucosa tissues. Our results suggest that the aberrantly expressed lncRNAs might expand our understanding of pathogenesis in H.pylori related diseases.

Methods

Cell lines and cultures

Cell lines were purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, SIBS, CAS (Shanghai, China). The human normal gastric epithelial cell line GES-1 was routinely cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y., USA). Human gastric cancer cell lines SGC-7901 and BGC-823 were propagated in low-glucose DMEM (Gibco). All the media were supplemented with 10 % (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Wisent Inc., Quebec, Canada). Cells were maintained in humidified air with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C before use.

H. pylori culture and infection model

H.pylori wild-type strain 26695 was obtained from ATCC and cultured on Columbia Agar (OXOID, UK) plates containing 5 % FBS (Wisent Inc.) grown at 37 °C in a microaerophilic atmosphere for 48 to 72 h.

Cells were seeded in six-well cell culture plates before infection. The following day, 80 % confluent monolayer cells were washed in PBS, and the medium was replaced with fresh medium. Then, H.pylori was added to cells for 24 h at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 as experimental groups. Cells without H.pylori infection were maintained for indicated time periods as control groups. After 24h infection, cells were washed in PBS to wash away the non-adherent H.pylori, then harvested in TransZol Up reagent (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and preserved at -80 °C until RNA isolation.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted from cells and tissues using TransZol Up reagent (TransGen Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantification and purity were measured by ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) measuring absorbance ratios of A260/A280 and A260/A230, and RNA integrity assessed by standard denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis.

Microarray analysis

The Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 (HTA 2.0; manufactured by Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was employed in this study. HTA 2.0 covers global profiling of full-length transcripts, containing more than 40,000 non-coding and 245,000 coding transcripts in human genome; each transcript is accurately identified by specific exon or exon-exon splice junction probes. All of the transcripts were collected from multiple public sources such as NCBI RefSeq, Ensembl, UCSC (known genes and lincRNA transcripts), Vertebrate Genome Annotation (Vega) database, Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC) (v10), www.noncode.org, lncRNA db, Broad Institute, Human Body Map lincRNAs and TUCP catalog. In the cases of small samples, random variance model (RVM) t-test was applied to filter the aberrantly expressed transcripts for experimental and control group. After significant analysis and false discovery rate (FDR) analysis, the differentially expressed transcripts were selected according to the P < 0.05.[10–12]. The cDNA labeling, microarray hybridization and bioinformatics analysis were performed by Genminix Informatics, Shanghai, China.

Construction of the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network

The lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network was built according to the normalized signal intensity of specific expression lncRNAs or mRNAs. The Pearson correlation was calculated for each pair of lncRNA-mRNA, and then, the significant correlation pairs were chosen to construct the network [13, 14]. The co-expression network was built in H.pylori-infected group and control group, respectively. Within a network, “degree” is the simplest and most important measure of the centrality of one gene or lncRNA that determining the relative importance. The “degree” is defined as the link number of one transcript directly had to the other [15]. The “degree” in infected group was recorded as S_Degree, while in control group was recorded as C_Degree. In addition, “clustering coefficient” is a measure of the “degree” to which transcripts in a network tend to cluster together. It was calculated by the local measure [16]. To exclude other transcripts’ impact in each co-expression network, we further performed normalization of the “degree”, i.e., divided by the maximum value of the transcript degree in each network [Normalized degree(X) = degree(X)/degree(Max)]. Then, the difference value of a transcript’s normalized degree (delta normalized degree, represented as |DiffK|) was calculated between the experimental and control co-expression networks. The core lncRNA/mRNA always owned the largest |DiffK|s [17].

Coding gene functional analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG Pathway analysis were performed to clarify the function and biological pathways of differentially expressed lncRNA co-expressed mRNAs from our microarray data. The differentially expressed mRNAs were annotated according to their attributes of gene products. Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org) was then used to assign the genes to different GO terms of their associated aspects: biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions, according to their annotations [18]. Furthermore, the biological function of genes can be better understood via integrated analysis of KEGG (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/) Pathways and gene annotations [19, 20]. The P-value was used to determine the significance of the enrichment, and the false discovery rate (FDR) was used to evaluate the significance of the P-value. The significant GO terms and pathways were filtered in accordance with P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.05.

Patient, specimens, and clinical data collection

The clinical specimens were collected from 126 patients with gastritis or ulcer at the Digestive Endoscopy center, and the gastric cancer tissues were collected from 30 gastric cancer patients undergoing surgery at the Second People’s Hospital of Changzhou in Changzhou, Jiangsu, China. In this study, 67 cases were H.pylori–positive, median age of patients (35 men and 32 women) was 49 years (range 20–81 years); 89 cases were H.pylori–negative as healthy control, median age of patients (45 men and 44 women) was 56 years (range 19–77 years). Three biopsy specimens taken from each patient were for histopathological examination, Rapid Urease Test (RUT; Huitai Medical tech corp., Shanghai, China), and for RNA extraction. The specimens were preserved in TransZol Up reagent at -80 °C until RNA isolation.

The H.pylori infection status was assessed by RUT and H. pylori-specific ureC polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [21]. H.pylori-positive patients were grouped under at least one of the tests yielded positive results. The patients neither received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) nor had taken antibiotics or proton pump inhibitor in the preceding 4 weeks. Informed consents were obtained from all individual participants enrolled in this study before examination. The information of specimens is presented in Additional file 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Following RNA extraction, 1 μg of RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiFiScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (CWBIOTECH, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The differentially expressed candidate lncRNAs in this study were verified by qRT-PCR (Table 1). Each qRT-PCR was performed using 2 × SYBR Green mix (TransGen Biotech) with cycling conditions of 94 °C for 5 min followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 30s, 58 or 60 °C for 25 s. For each sample, we performed qRT-PCR for target genes and a housekeeping gene β-actin as an internal control. The sequences of specific primers are listed in Table 2. After PCR amplification, melt curve analysis was performed to confirm reaction specificity; expression fold change of each lncRNA was calculated via the 2-ΔΔCt method. Differences in expression levels between H.pylori–positive and negative samples were analyzed using Student’s t-test, with a value of P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Microarray expression results of selected lncRNAs. “S” represents H.pylori-infected GES-1 groups, and “C” represents control groups. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

| lncRNA Accession Number | Gene Symbol | Variation trend | Fold change (S/C) | P-value | lncRNA Source | Probe ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n345630 | down | 0.099 | <1e-07 | NONCODE | TC04001940.hg.1 | |

| TCONS_00010304-XLOC_004787 | down | 0.14 | < 1e-07 | Rinn lincRNAs | TC05002959.hg.1 | |

| n378726 | down | 0.15 | < 1e-07 | NONCODE | TC06003993.hg.1 | |

| NR_026860 | LINC00473 | down | 0.16 | < 1e-07 | RefSeq | TC06002302.hg.1 |

| n345729 | down | 0.18 | < 1e-07 | NONCODE | TC05002683.hg.1 | |

| n342056 | down | 0.41 | 1.06E-05 | NONCODE | TC12002644.hg.1 | |

| n384667 | down | 0.42 | 1.80E-06 | NONCODE | TC05003053.hg.1 | |

| TCONS_00011401-XLOC_005517 | up | 1.63 | 4.24E-05 | Rinn lincRNAs | TC06003154.hg.1 | |

| NR_038366 | HOTAIRM1 | up | 1.65 | 1.66E-05 | RefSeq | TC07000165.hg.1 |

| NR_024204 | LINC00152 | up | 2.11 | 1.00E-07 | RefSeq | TC02000535.hg.1 |

| NR_015379 | UCA1 | up | 2.15 | 1.70E-06 | RefSeq | TC19000279.hg.1 |

| TCONS_00027385-XLOC_013370 | up | 2.22 | 1.85E-04 | Rinn lincRNAs | TC19002530.hg.1 | |

| n408024 | up | 4.84 | < 1e-07 | NONCODE | TC0X001624.hg.1 |

Table 2.

Primers designed for qRT-PCR validation of candidate lncRNAs and β-actin

| lncRNA Accession Number | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product length (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n345630 | 5'-TCCGTTGAACCTTCCACAGT-3' | 5'-ACTCTGCTCCGTTCCACATT-3' | 168 | 58 |

| TCONS_00010304-XLOC_004787 | 5'-CTCAGGAAAGGAGTATAGAATG-3' | 5'-GGTGCAAGGTATAGAGTGT-3' | 104 | 58 |

| n378726 | 5'-CCACAATGCAAACAACTGCT-3' | 5'-GAAAGCTGCTCTGTGGTGAA -3' | 161 | 60 |

| NR_026860 | 5'-CTTGGTTGTGCGGGATTCT-3' | 5'-GTCAGAAGGAGGAGCAGGTAG-3' | 204 | 60 |

| n345729 | 5'-AGGGTCATTTAGCCAGAAAGT-3 | 5'-GATAAACCCAGATGCCCTTGTAG-3' | 144 | 58 |

| n342056 | 5'-CAGGCTTATGGAGCGTTAAGAAT-3' | 5'-CATCAGGGAGAAGTTATCAGGT-3' | 177 | 58 |

| n384667 | 5'-TGCCTGATAAGGTCACATACAC-3' | 5'-CCAGGACATGCGATGAAGATTG-3' | 123 | 58 |

| TCONS_00011401-XLOC_005517 | 5'-TCCTGGGTCAAGCTGAGTATC-3' | 5'-TGGAGTCTTACAAATCTTTTA-3' | 131 | 58 |

| NR_038366 | 5'-ACTCCGTGTTACTCATTCC-3' | 5'-TTGCTTCTTCTTCTCCTCTT-3' | 188 | 58 |

| NR_024204 | 5'-GAATAACTGGGAGATGAAACAGG-3' | 5'-CAACAGGTAGAGGTGCTGGA-3' | 102 | 58 |

| NR_015379 | 5'-TCCATTCAGACCGCCACTCAC-3' | 5'-CAAGGTGCCAGTTAGCGTAT-3' | 244 | 58 |

| TCONS_00027385-XLOC_013370 | 5'-GGCTGTCTTAGAAGGATGAA-3' | 5'-AATAGAGCTGGTTGACTGC-3' | 129 | 58 |

| n408024 | 5'-CGGAAGGTTACAGTCTCTAG-3' | 5'-TGCTGTGTCCTCATTTATCA-3' | 125 | 58 |

| β-actin | 5'-GATGACCCAGATCATGTTTGAG-3' | 5'-AGGGCATACCCCTCGTAGAT-3' | 159 | 58-60 |

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Statistical significance of difference in the means between groups was analyzed using Student’s t-test with SPSS software (version 20.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Analysis of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs

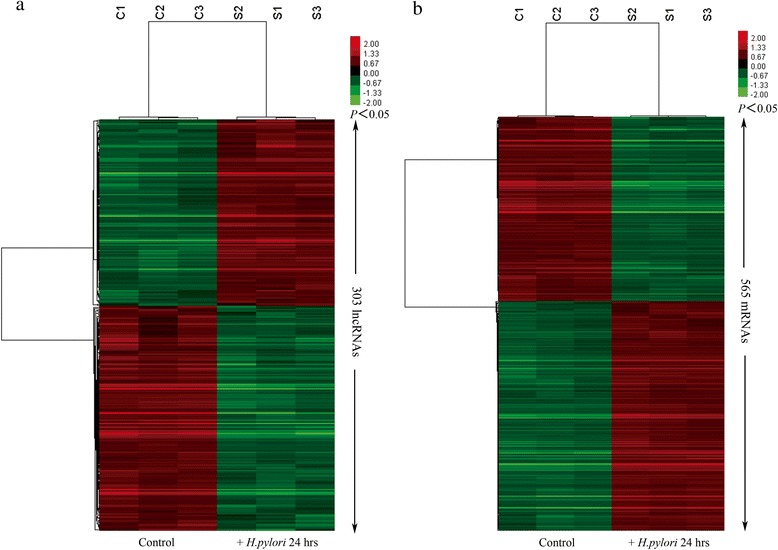

To explore the potential lncRNAs involved in H.pylori–induced gastric mucosa disorders, we examined the lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles in gastric epithelia cell models through microarray analysis (Fig. 1). According to the microarray data and the authoritative data, 303 unique lncRNAs were significantly induced or suppressed in GES-1 following H.pylori infection, of which 56.4 % (171 lncRNAs) were suppressed and 43.6 % (132 lncRNAs) were induced (fold change ≥2 or ≤0.5, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1a, Additional file 2). n335470 (11.48-fold change) was the most significantly up-regulated lncRNA and NR_002763 (CPS1-IT1, 0.075-fold change) was the most significantly down-regulated lncRNA.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of gene expression levels between H.pylori-infected groups and control groups. 303 lncRNAs a and 565 mRNAs b were significantly changed in response to H.pylori infection. The clustering analysis was performed by Cluster 3.0 software with average linkage clustering algorithm and visualized by Treeview. “S” and “C” represent H.pylori-infected groups and control groups. “Red” and “green” indicate up-regulated and down-regulated transcripts, respectively

As to mRNAs, the expression profiling data showed that of the total 1936 mRNAs, 565 were aberrantly expressed mRNAs in H.pylori-infection models relative to their control models (fold change ≥2 or ≤0.5, P < 0.05), of which 49.2 % (278 mRNAs) were up-regulated, while 50.8 % (287 mRNAs) were down-regulated (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2). Among these mRNAs, IGFBP1 (12-fold change) showed the highest degree of up-regulation, while MUC13 (0.11-fold change) was the most down-regulated protein-coding gene.

The complete microarray data are publicly available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE74577.

LncRNA-mRNA co-expression network

We constructed the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network to identify the interactions between mRNA and lncRNA. The value of “Degree” in co-expression network indicated that one mRNA/lncRNA might correlate with several lncRNAs/mRNAs. The core lncRNA/mRNA from the co-expression network were identified according to the |DiffK|s, and supposed to interact in processes of H.pylori infection. The lncRNAs with 30° in experimental group network are listed in Table 3, and the top 10 lncRNAs in co-expression network are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

The “Degree” of lncRNAs in co-expression network of experimental group (only no less than 30° is shown)

| LncRNA | Type | Style | Degree | Clustering Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n336000 | noncoding | up | 32 | 0.8004 |

| TCONS_00027385-XLOC_013370 | noncoding | up | 32 | 0.8004 |

| n326267 | noncoding | down | 32 | 0.7903 |

| n384365 | noncoding | down | 31 | 0.8215 |

| n387010 | noncoding | down | 31 | 0.8215 |

| n345751 | noncoding | down | 30 | 0.8253 |

| NR_038407 | noncoding | down | 30 | 0.8069 |

| n384667 | noncoding | down | 30 | 0.7701 |

| n337099 | noncoding | down | 30 | 0.7563 |

| n344793 | noncoding | down | 30 | 0.754 |

Table 4.

The top ten lncRNAs with largest |DiffK| in co-expression network

| LncRNA | Style | S_Degree | S_K | C_Degree | C_K | DiffK(S-C) | |DiffK| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n334184 | up | 26 | 0.7647 | 9 | 0.2432 | 0.5215 | 0.5215 |

| NR_033917 | down | 11 | 0.3235 | 30 | 0.8108 | −0.4873 | 0.4873 |

| n339262 | up | 28 | 0.8235 | 13 | 0.3514 | 0.4722 | 0.4722 |

| TCONS_00011401-XLOC_005517 | up | 27 | 0.7941 | 12 | 0.3243 | 0.4698 | 0.4698 |

| n340399 | down | 9 | 0.2647 | 27 | 0.7297 | −0.465 | 0.465 |

| TCONS_l2_00005430-XLOC_l2_002852 | down | 12 | 0.3529 | 30 | 0.8108 | −0.4579 | 0.4579 |

| TCONS_00027385-XLOC_013370 | up | 32 | 0.9412 | 18 | 0.4865 | 0.4547 | 0.4547 |

| n335665 | up | 28 | 0.8235 | 14 | 0.3784 | 0.4452 | 0.4452 |

| n335607 | up | 21 | 0.6176 | 7 | 0.1892 | 0.4285 | 0.4285 |

| TCONS_00010304-XLOC_004787 | down | 14 | 0.4118 | 31 | 0.8378 | −0.4261 | 0.4261 |

GO analysis and KEGG Pathway analysis of aberrantly expressed mRNAs

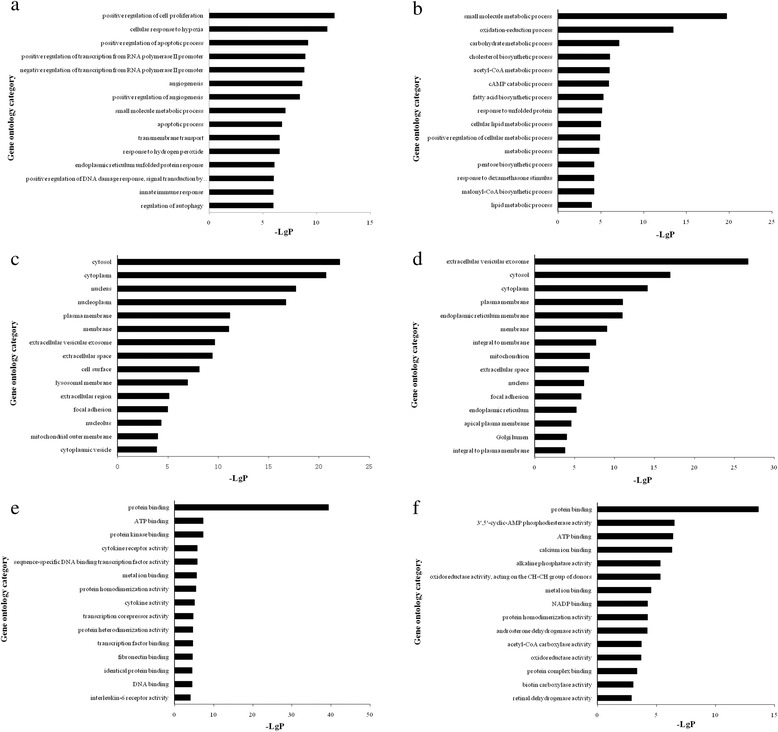

GO analysis was applied to investigate the potential functions of the lncRNAs co-expressed mRNAs on the regulation of the pathological responses against H.pylori infection. In this study, corresponding to the up-regulated mRNA, there were 189 aberrantly expressed mRNAs assigned to biological process, 213 assigned to cellular component and 181 assigned to molecular function; while among the down-regulated genes, there were 133 aberrant expressed mRNAs assigned to biological process, 170 assigned to cellular component and 137 assigned to molecular function. The significance of enrichment of each GO term was assessed by P-value <0.05 and FDR < 0.05, then the GO terms were filtered by the enrichment scores (-Lg (P)) in aberrantly expressed mRNAs. The enrichment analyses of top fifteen GO terms were listed in Additional file 3 and shown in Fig. 2. The GO enrichment analysis revealed that positive regulation of cell proliferation (GO: 0008284), cytosol (GO: 0005829), protein binding (GO: 0005515) were the most enriched GO terms targeted by aberrantly up-regulated mRNAs in biological process, cellular component and molecular function, respectively (Fig. 2 a, c, e). While the small molecule metabolic process (GO: 0044281), extracellular vesicular exosome (GO: 0070062) and protein binding (GO: 0005515) were the most enriched GO terms targeted by aberrantly down-regulated mRNAs in biological process, cellular component and molecular function, respectively (Fig. 2 b, d, f).

Fig. 2.

GO enrichment analysis of aberrantly expressed mRNAs. GO analysis of lncRNA co-expressed mRNAs according to biological process a, b, cell component c, d and molecular function e, f. a, c, e: the enriched GO terms targeted by up-regulated mRNAs; b, d, f: the enriched GO terms targeted by down-regulated mRNAs. The most enriched GO terms were filtered in accordance with P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.05. The bar plot “-Lg (P)” represents the enrichment score of enriched GO term

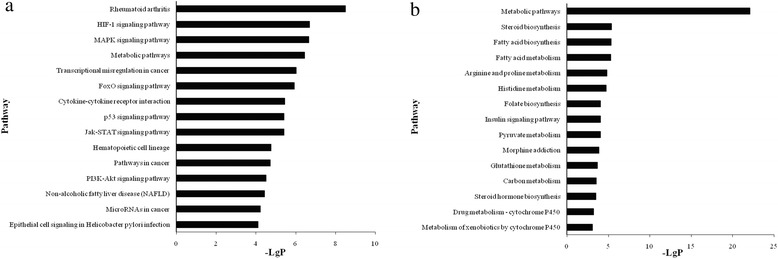

KEGG Pathway analysis offered us a reliable way to elucidate the candidate biological pathways that the lncRNAs interacted with mRNAs. We identified 54 up-regulated pathways comprising 90 differentially expressed genes, among them, the top three enriched pathways were rheumatoid arthritis (pathway ID: 05323), HIF-1 signaling pathway (pathway ID: 04066), and MAPK signaling pathway (pathway ID: 04010). 40 down-regulated pathways containing 61 differentially expressed genes were identified, and the top three enriched pathways were metabolic pathways (pathway ID: 01100), steroid biosynthesis (pathway ID: 00100), and fatty acid biosynthesis (pathway ID: 00061). The enrichment analyses of top fifteen pathways were showed in Fig. 3, the pathways and genes were listed in Additional file 4.

Fig. 3.

KEGG Pathway analysis of aberrantly expressed mRNAs. Top ten enriched up-regulated a and down-regulated pathways b. The most enriched pathways were filtered in accordance with P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.05. The bar plot “-Lg (P)” represents the enrichment score of enriched pathway

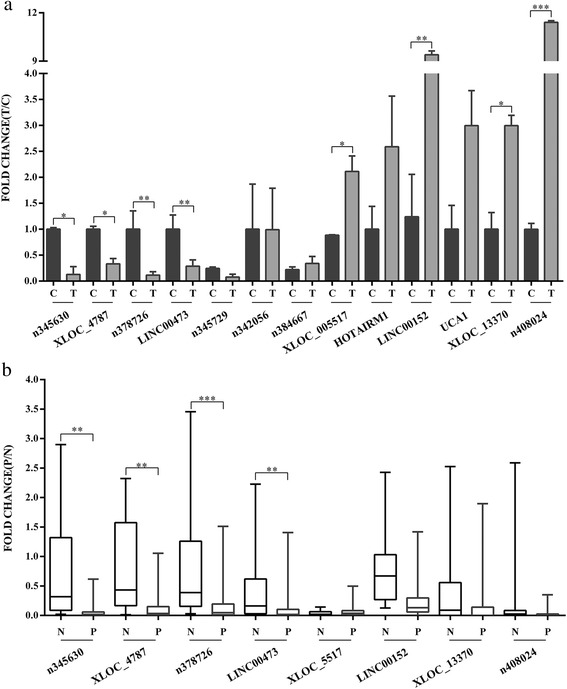

Validation of the expression levels of lncRNAs by qRT-PCR

To confirm the accuracy and repeatability of the microarray data, 13 candidate lncRNAs were selected for validation by qRT-PCR based on their features, such as fold change, adjacent co-expressed mRNAs, and literatures reported. PCR was first carried out to confirm the expression of candidate lncRNAs in GES-1 cells (Additional file 5). The lncRNAsexpression pattern detected by qRT-PCR analysis was the same as that determined by microarray analysis. The changes were statistically difference for only 8 of the 13 lncRNAs (Fig. 4a). We confirmed that n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, and LINC00473 were suppressed during H. pylori infection, whereas the expression of XLOC_005517, LINC00152, XLOC_13370 and n408024 were induced (P < 0.05). The 13 candidate lncRNAs were also assessed in other two kinds of gastric cancer cell lines upon H.pylori treatment. However, the expression patterns of candidate lncRNAs in BGC-823 and SGC-7901 were very different from those in GES-1 cell lines under the same conditions (Additional file 6).

Fig. 4.

Expression patterns of the candidate lncRNAs in cells and clinical tissue samples. a: QRT-PCR validation of 13 candidate lncRNAs relative expression levels in H.pylori-infected GES-1 cells compared with controls. “Column T” represents experimental groups, and “column C” represents control groups. b: QRT-PCR validation of eight lncRNAs in 156 clinical tissue samples. “Column P” stands for H.pylori-positive tissue samples, and “column N stands for H.pylori-negative tissue samples. All results were expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments with significant P-values (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Then we confirmed the aberrant expression pattern of the 8 candidate lncRNAs in 156 clinical specimens by qRT-PCR. The results indicated that n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, and LINC00473 were down-regulated (P < 0.05) in 67 H.pylori–positive specimens compared with 89 negative specimens (Fig. 4b), whereas no significant changes were observed in XLOC_005517, XLOC_13370 or n408024. Interestingly, there was an opposing expression pattern of LINC00152 in clinical specimens compared with the microarray data (P < 0.001).

Discussion

H.pylori possesses numerous factors to successfully colonize the gastric mucosa, influence host immune system, and induce gastric pathology. For the past several decades the molecular mechanisms of H.pylori have been widely studied, while the pathogenesis of this agent is still indefinite and most of the involved gene transcriptional regulations remain to be defined. The recent studies on microRNAs (miRNAs) have expanded our insights on H.pylori pathogenesis. MiRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs, short in length, participate in post-transcriptional regulation, and play an important role in multiple biological functions. Aberrantly expressed miRNAs contributed to human diseases and carcinogenesis. Numerous miRNAs have been reported to involve in H.pylori-associated gastric pathology by changing the expression of target mRNAs [22, 23]. Zhang et al. reported that miR-21 over-expression was associated with increased cellular proliferation and antiapoptosis in H.pylori-positive gastric tissues [24]; miR-146a and miR-155 were specifically involved in the attenuation of the proinflammatory responses against H.pylori [25, 26].

LncRNAs are emerging non-coding RNAs in molecular research, longer in length, involved in almost each level of gene expression and regulate diverse functions, such as genome rearrangement, chromatin modification, imprinting, transcription, splicing and translation [27–29]. Increasing discoveries indicated that, like miRNAs, lncRNAs played distinguished roles in pathogenesis and tumorigenesis, and could be novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in diseases [30]. However, only few of lncRNAs were studied to be related to diseases, majority of which are unrevealed and so are those in the H.pylori-induced diseases. Thus, we conducted the current study to uncover the role of H.pylori in gastric pathological development from a brand new sight of lncRNA. There was only one report exploring the expression profiles of lncRNAs in gastric epithelial cell response to H.pylori infection. Liu et al. found that two differentially expressed lncRNAs, XLOC_014388 and XLOC_004122, in H.pylori-positive tissues, might be involved in the immune response against H. pylori infection [31].

In this study, we used HTA 2.0 microarray to detect the expression profiles of lncRNAs in H.pylori-infected GES-1 cells in vitro. We chose gastric epithelial cell line GES-1 for its versatility, non-malignancy and widely used in studying cell signaling cascades response to H.pylori infection [32]. Our data showed a set of differentially expressed lncRNAs, including 171 down-regulated and 132 up-regulated lncRNAs in infected cells. Construction of lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network displayed aberrantly expressed lncRNAs/mRNAs which were significantly correlated with their adjacent mRNAs/lncRNAs. From the network of experimental group, we observed that two lncRNAs (n336000 and XLOC_013370) were involved in the most connections (32°) with other transcripts, including 10 target mRNAs (Table 3). As for mRNAs, IER2 was correlated with 23 lncRNAs of the total 34 connections (data not shown). In addition, we found that IER2 and n334184 owned the highest value of |DiffK| in lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network, which indicated that they might play key roles in the development of H.pylori–associated disorders and diseases through interaction with many other transcripts (Table 4).

Furthermore, in order to predict the potential functions of lncRNAs, we used GO analysis and KEGG Pathway annotation to investigate the lncRNA co-expressed mRNAs. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the number of genes corresponding to up-regulated mRNAs was larger than that corresponding to down-regulated mRNAs. Pathway annotation showed that there were 54 up-regulated pathways and 40 down-regulated pathways. The significantly enriched up-regulated pathways like HIF-1 signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, p53 signaling pathway, and Jak-STAT signaling pathway, contained significantly up-regulated mRNAs, such as VEGFA, MMP1, JUN, MYC, EGFR, FGF2, HK2, ICAM1, CSF1, IL1A, etc (Additional file 4). The overexpression of these genes is contributed to promoting cell proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, antiapoptosis, immune responses, and multiple genetic transcriptions. The aberrantly expressed lncRNAs which were co-expressed with these genes in network might have involved in and play collective roles in mediating such processes in H.pylori infection.

We initially validated a number of interesting candidate lncRNAs for further study,including 7 down-regulated and 6 up-regulated lncRNAs. We finally found that 8 lncRNAs (n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, LINC00473, XLOC_005517, LINC00152, XLOC_13370, and n408024) were consistent with microarray results in cell models. There were discrepancies between the results of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs detected in different cell models (SGC-7901 and BGC-823). SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cell lines are from human gastric adenocarcinoma; their cellular responses against H.pylori were very different from those in normal gastric mucosal epithelial cells (showed in Additional file 6). So we concluded that the lncRNA expression profiles of those two cancer cell lines were also very different. The lncRNAs, n345630, XLOC_004787, n378726, and LINC00473 were exhibited down-regulation in 67 H.pylori–positive mucosa specimens compared with negative specimens. Increased expression of LINC00152 has been reported in gastric cancer and was involved in cell proliferation [33, 34]. At first we supposed that LINC00152 might be involved in pathogenesis of H.pylori associated digestive diseases. The qRT-PCR validation of LINC00152 expression pattern in H.pylori–infected cells was confirmed to be consistent with microarray data (2.11-fold change). However, when it came to the gastric mucosa tissues, we found reversed expression pattern (P < 0.001) out of expectation.

Conclusions

In this preliminary study, we identified a subset of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs in H.pylori-infected models and gastric mucosa tissues. Our data suggested that these novel lncRNAs might contribute to the pathological responses and development of H.pylori related disorders and diseases. However, there are still a lot of problems remained to be addressed. Further mechanism studies of these versatile molecules are most important required, which will broaden our understanding of pathogenesis and provide new approaches to the diagnosis and therapies of H.pylori infection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81301396, 81271795), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (Grant no. BK20130542), Specialized Fund of Clinical Medicine in Jiangsu Province (Grant no. BL2012047), and the China Postdoctoral Science Found (Grant no.2013 M531290). We thank Genminix Informatics for their microarray service and bioinformatics assistance.

Abbreviations

- LncRNAs

Long non-coding RNAs

- H.pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Additional files

Clinical specimens information. (XLSX 15 kb)

Aberrantly expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in GES-1 cells infected by H.pylori. (XLSX 621 kb)

GO analysis of aberrantly expressed mRNAs. (XLSX 24 kb)

KEGG Pathway analysis of aberrantly expressed mRNAs. (XLSX 32 kb)

Confirmation of expression of 13 candidate lncRNAs in GES-1 cells. (TIFF 9954 kb)

Expression patterns of the candidate lncRNAs in BGC-823 and SGC-7901 cells. (TIFF 2680 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZH and WH designed the study. ZH conducted the majority of the experiments. YYZ and SYX contributed to the H.pylori culture. WQ and ZH collected the clinical specimens and data. FJ and NY performed RNA extractions. ZH, SFY, and FJ carried out RT-PCR reactions and the data analysis. ZH drafted the manuscript. SSH and WH provided advice and suggestions, revised the manuscript, and provided financial support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Hong Zhu, Email: emeraldzh@sina.com.

Qiang Wang, Email: wqyx80513@126.com.

Yizheng Yao, Email: yaoyizheng1228@163.com.

Jian Fang, Email: 510264709@qq.com.

Fengying Sun, Email: sfy7432160@126.com.

Ying Ni, Email: Ali_Fantasy@yeah.com.

Yixin Shen, Email: 1017448491@qq.com.

Hua Wang, Email: wangjiahan1979@163.com.

Shihe Shao, Email: shaoshihe2006@163.com.

References

- 1.Kalali B, Mejias-Luque R, Javaheri A, Gerhard M. H. pylori virulence factors: influence on immune system and pathology. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:426309. doi: 10.1155/2014/426309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polk DB, Peek RM., Jr Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):403–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, Qiao L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23(13):1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatica A, Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(1):7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrg3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152(6):1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi X, Sun M, Liu H, Yao Y, Song Y. Long non-coding RNAs: a new frontier in the study of human diseases. Cancer Lett. 2013;339(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maass PG, Luft FC, Bahring S. Long non-coding RNA in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92(4):337–346. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright GW, Simon RM. A random variance model for detection of differential gene expression in small microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(18):2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Crawford N, Lukes L, Finney R, Lancaster M, Hunter KW. Metastasis predictive signature profiles pre-exist in normal tissues. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22(7):593–603. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-6244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke R, Ressom HW, Wang A, Xuan J, Liu MC, Gehan EA, et al. The properties of high-dimensional data spaces: implications for exploring gene and protein expression data. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(1):37–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pujana MA, Han JD, Starita LM, Stevens KN, Tewari M, Ahn JS, et al. Network modeling links breast cancer susceptibility and centrosome dysfunction. Nat Genet. 2007;39(11):1338–1349. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prieto C, Risueno A, Fontanillo C, De las Rivas J. Human gene coexpression landscape: confident network derived from tissue transcriptomic profiles. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(2):101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393(6684):440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson MR, Zhang B, Fang Z, Mischel PS, Horvath S, Nelson SF. Gene connectivity, function, and sequence conservation: predictions from modular yeast co-expression networks. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SI, Oyedeji KS, Arigbabu AO, Cantet F, Megraud F, Ojo OO, et al. Comparison of three PCR methods for detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA and detection of cagA gene in gastric biopsy specimens. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(13):1958–1960. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushima K, Isomoto H, Inoue N, Nakayama T, Hayashi T, Nakayama M, et al. MicroRNA signatures in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(2):361–370. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadamuro AC, Rossi AF, Maniezzo NM, Silva AE. Helicobacter pylori infection: host immune response, implications on gene expression and microRNAs. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(6):1424–1437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Li Z, Gao C, Chen P, Chen J, Liu W, et al. miR-21 plays a pivotal role in gastric cancer pathogenesis and progression. Lab Invest. 2008;88(12):1358–1366. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Xiao B, Tang B, Li B, Li N, Zhu E, et al. Up-regulated microRNA-146a negatively modulate Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammatory response in human gastric epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2010;12(11):854–863. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao B, Liu Z, Li BS, Tang B, Li W, Guo G, et al. Induction of microRNA-155 during Helicobacter pylori infection and its negative regulatory role in the inflammatory response. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(6):916–925. doi: 10.1086/605443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran VA, Perera RJ, Khalil AM. Emerging functional and mechanistic paradigms of mammalian long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(14):6391–6400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holoch D, Moazed D. RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(2):71–84. doi: 10.1038/nrg3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergmann JH, Spector DL. Long non-coding RNAs: modulators of nuclear structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;26:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutschner T, Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9(6):703–719. doi: 10.4161/rna.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L, Long Y, Li C, Cao L, Gan H, Huang K, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Long Noncoding RNA Profile in Human Gastric Epithelial Cell Response to Helicobacter pylori. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68(1):63–66. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Luo LD, Pan JH, Huang LH, Lv HW, Guo Q, et al. Comparative genomic study of gastric epithelial cells co-cultured with Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(48):7212–7224. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pang Q, Ge J, Shao Y, Sun W, Song H, Xia T, et al. Increased expression of long intergenic non-coding RNA LINC00152 in gastric cancer and its clinical significance. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(6):5441–5447. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao J, Liu Y, Zhang W, Zhou Z, Wu J, Cui P, et al. Long non-coding RNA Linc00152 is involved in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, cell migration and invasion in gastric cancer. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(19):3112–3123. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1078034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]