Abstract

Estrogen deprivation is considered responsible for many age-related processes, including poor wound healing. Guided by previous observations that estradiol accelerates re-epithelialization through estrogen receptor (ER)-β, in the present study, we examined whether selective ER agonists [4,4′,4″-(4-propyl [1H] pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)-trisphenol (PPT), ER-α agonist; 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (DPN), ER-β agonist] affect the expression of basic proliferation and differentiation markers (Ki-67, keratin-10, -14 and -19, galectin-1 and Sox-2) of keratinocytes using HaCaT cells. In parallel, ovariectomized rats were treated daily with an ER modulator, and wound tissue was removed 21 days after wounding and routinely processed for basic histological analysis. Our results revealed that the HaCaT keratinocytes expressed both ER-α and -β, and thus are well-suited for studying the effects of ER agonists on epidermal regeneration. The activation of ER-α produced a protein expression pattern similar to that observed in the control culture, with a moderate expression of Ki-67 being observed. However, the activation of ER-β led to an increase in cell proliferation and keratin-19 expression, as well as a decrease in galectin-1 expression. Fittingly, in rat wounds treated with the ER-β agonist (DPN), epidermal regeneration was accelerated. In the present study, we provide information on the mechanisms through which estrogens affect the expression patterns of selected markers, thus modulating keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation; in addition, we demonstrate that the pharmacological activation of ER-α and -β has a direct impact on wound healing.

Keywords: epidermis, estrogens, galectin, menopause, regeneration

Introduction

It is well known that the efficiency of the wound healing process is reduced with aging, and the skin becomes more fragile and susceptible to trauma (1). Estrogen deprivation in post-menopausal women is considered responsible for a number of issues associated with aging, including poor wound healing (2–4). Notably, in females, estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) has been proven to reverse delayed wound healing which is related to aging, and this effect is mediated by at least two basic mechanisms: i) the downregulation of the expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (5), a key player in skin biology and wound healing (6); and ii) the increase of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) production by dermal fibroblasts (7).

Cells with low-level differentiation potential have the ability to stimulate tissue renewal (8), which is of great significance in tumor growth and/or tissue repair (9,10). Keratinocytes proliferate and migrate over the wound to create a barrier between the outer and inner environments (11), through re-epithelialization. The level of keratinocyte differentiation can change during the process of epithelialization, determined by assessing the presence of distinct keratins (12). For example, the expression of keratin-10 is restricted to differentiated keratinocytes located in the suprabasal epidermal layer (13,14). By contrast, keratin-14 positivity is considered a marker of proliferating, non-terminally differentiated keratinocytes located in the basal layer of the epidermis (13,15). In addition, the expression of keratin-19 is confined to cells of hair follicles (16), a characteristic which exemplifies the stem cell-like character of keratinocytes (16,17).

As regards routes of biological information transfer, increasing attention has been paid to glycans attached to proteins and lipids. Notably, sugar-encoded information of glyco-conjugates is translated into cellular responses by endogenous lectins (18–20). Members of the family of adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins are known to be involved in these responses, and their expression is stringently controlled, e.g., during differentiation (21–23). Since galectins play an important regulatory role in cell proliferation, migration and extracellular matrix formation (24–26) and are expressed in tumors (cell lines and clinical specimens) as detected by hemagglutination and purification by affinity chromatography (27,28), it has been postulated that they are biorelevant modulators of wound/tumor microenvironments (29). For example, the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is rich in fibronectin and galectin-1, serves as an active substratum when feeder cells are substituted for keratinocytes (26). Galectin-1, a multifunctional effector in various compartments (30,31), is upregulated during the early phases of healing (25,32), and is known to have anti-inflammatory properties (33).

As keratinocytes are known to express estrogen receptors (ERs) (34), we can posit that the regeneration of the epidermis may be modulated through this route. In this context, it has been previously demonstrated that the administration of exogenous estrogen to ovariectomized ER-β knockout mice delays wound healing and that the beneficial effects of ERT are mediated through epidermal ER-β (35,36). However, little is known about the underlying mechanisms of estrogen regeneration, in particular the cell type-specific role of the two nuclear ERs, ER-α and ER-β. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to assess the effects of two ER agonists on the expression of certain protein markers (Ki-67, keratins-10, -14 and -19, and galectin-1) in HaCaT kerati-nocytes in an attempt to better understand the mechanisms of the ER-β-mediated acceleration of re-epithelialization, which has been previously identified (36). In addition, the in vivo effects of the selective ER agonists were investigated using an open wound healing model with ovariectomized Sprague-Dawley rats.

Materials and methods

Drug preparation

4,4′,4″-(4-propyl [1H] pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)-trisphenol (PPT), a selective ER-α agonist and 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (DPN), a selective ER-β agonist, were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT

Cells of the HaCaT line (37) were obtained from CLS Cell Lines Service (Eppelheim, Germany). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (streptomycin and penicillin) (all from Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). The cells were seeded on coverslips at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2 and cultured for 24 h. The ER agonists, PPT and DPN, were added to the medium to reach a final concentration of 10 nM, as previously described (38), and the cells were then cultured for 4 days.

HaCaT immunocytochemical analysis

The HaCaT cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.2). Non-specific binding of the secondary antibody was blocked by pre-incubation with normal swine serum (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted in PBS for 30 min. Details of the commercial antibodies used in the present study are presented in Table I; the anti-galectin-1 antibody was made in our laboratory, and we tested it to ensure that it was free of cross-reactivity against human galectins-2, -3, -4, -7, -8 and -9 by western blot analysis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), as previously described (39). We controlled antigen-dependent specificity was by replacing the first-step antibody with an antibody of the same isotype directed against an antigen not present in the cells, or omitting the incubation stage with the antibody. The nuclei of the cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich), which specifically recognizes DNA.

Table I.

Commercial reagents used in immunocytochemical analysis.

| Primary antibody | Abbreviation | Host | Produced by | Secondary antibody | Produced by | Channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki-67 | Ki-67 | Mouse monoclonal | DakoCytomation | Goat anti-mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | TRITC-red |

| High-molecular-weight keratin | HMWK | Mouse monoclonal | DakoCytomation | Goat anti-mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | TRITC-red |

| Keratin-10 | K10 | Mouse monoclonal | DakoCytomation | Goat anti-mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | TRITC-red |

| Keratin-14 | K14 | Mouse monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | Goat anti-mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | TRITC-red |

| Keratin-19 | K19 | Mouse monoclonal | Dakopatts | Goat anti-mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | TRITC-red |

| Wide-spectrum keratin | WSK | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | Swine anti-rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FITC-green |

| Sox-2 | SOX-2 | Rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | Swine anti-rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FITC-green |

| Estrogen receptor-α | ER-α | Rabbit polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | Swine anti-rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FITC-green |

| Estrogen receptor-β | ER-β | Rabbit polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | Swine anti-rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FITC-green |

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); Abcam (Cambridge, UK); DakoCytomation (Glostrup, Denmark); Dakopatts (Glostrup, Denmark).

RNA isolation, cDNA preparation by reverse transcription and ER-specific mRNA amplification by real-time (quantitative) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the HaCaT cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Woburn, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was carried out according to the instructions provided by Qiagen with the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, for each sample, 150 ng of total RNA was added to a solution with RT-PCR buffer, deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) mix (10 mM of each dNTP), primers (10 µM each) and enzyme mix. The following primers were used: for ER-α detection forward, 5′-GGA GGG CAG GGG TGA A-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGC CAG GCT GTT CTT CTT CTT AG-3′; for ER-β detection forward, 5′-AGA GTC CCT GGT GTG AAG CAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAC AGC GCA GAA GTG AGC ATC-3′; and for β-actin detection forward, 5′-ACC AAC TGG GAC GAC ATG GAG AA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTA GCC GCG CTC GGT GAG GAT CT-3′. SYBR-Green Supermix (Bio-Rad iQ™; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used with the following thermal cycling steps: 30 min at 50°C for reverse transcription, and 5 min at 95°C for initial PCR activation using the LightCycler Carousel-Based system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). PCR cycles were run as follows: 60 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 55°C, and 15 sec at 72°C (cooling to 37°C).

Acquisition of microphotographs and processing of data

Microphotographs of processed samples labeled with fluorochromes were recorded with identical settings using an Eclipse 90i fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with filterblocks for fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) and DAPI, and a Cool-1300Q CCD camera (Vosskühler, Osnabrück, Germany). Data were processed and analyzed with a LUCIA 5.1 computer-assisted image analysis system (Laboratory Imaging, Prague, Czech Republic).

Animal model

The experimental conditions complied with European rules on animal treatment and welfare. Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice and by the State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic.

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (n=20) at 4 months of age, were used in the present study. The rats were randomly divided into 4 groups with 5 animals in each group: i) the control group: sham-operated rats, treated with the vehicle (NOV-C group); ii) ovariectomized rats treated with the vehicle (OVX-C group); iii) ovariectomized rats treated with the selective ER-α agonist, PPT (OVX-PPT group); and iv) ovariectomized rats treated with the selective ER-β agonist, DPN (OVX-DPN group).

All surgical interventions were performed under general anesthetic induced by the administration of 33 mg/kg of ketamine (Narkamon a.u.v.; Spofa a.s., Prague, Czech Republic), 11 mg/kg xylazine (Rometar a.u.v.; Spofa a.s.) and 5 mg/kg tramadol (Tramadol-K; Krka, Novo Mesto, Slovenia).

Twelve weeks prior to beginning the wound-healing experiment, as previously described (40), rats from all the OVX groups underwent ovariectomies, whereas the rats from the control group were sham-operated.

One round full-thickness skin wound, 1 cm in diameter, was inflicted under aseptic conditions on the back of each rat (Fig. 1). After wounding, rats from the OVX-PPT and OVX-DPN groups were treated daily (during the first 7 days after surgery) with 1 mg/kg of PPT and DPN subcutaneously, while the other rats received the vehicle (1% DMSO), as previously described (41,42). On day 21 post-surgery, 5 animals from each group were sacrificed by ether inhalation, and the wound tissues were removed for further processing.

Figure 1.

Location and dimensions of the excisional wound on the back of each rat.

Histological analysis of skin wounds and semi-quantitative analysis of histological sections

Tissue specimens were processed routinely for light microscopy [fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)]. The stained sections were evaluated in a blinded manner (without knowing which section belonged with which rat group) using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a DP50 CCD camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

A semi-quantitative method, which has been previously described (43), was used to monitor the re-epithelialization of the epidermis and the presence of inflammatory cells [polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs), fibroblasts, vessels and new collagen]. The sections were evaluated in a blinded manner according on a scale of 0 to 4 (Table II).

Table II.

Definition of scale in the semi-quantitative evaluation of the histological sections.

| Scale | Epithelization | PMNL | Fibroblasts | Luminized vessels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Thickness of cut edges | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| 1 | Migration of cells (<50%) | Mild ST | Mild ST | Mild SCT |

| 2 | Migration of cells (≥50%) | Mild DL/GT | Mild GT | Mild GT |

| 3 | Bridging the excision | Moderate DL/GT | Moderate GT | Moderate GT |

| 4 | Keratinization | Marked DL/GT | Marked GT | Marked GT |

ST, surrounding tissue; DL, demarcation line; SCT, subcutaneous tissue; GT, granulation tissue. PMNL, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was used to compare the differences in the number (percentages) of Ki-67-, keratin-10-, keratin-14-, keratin-19- and galectin-1-positive cells (data are presented as the means ± standard deviation). Data from the semi-quantitative analysis are presented as median and were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

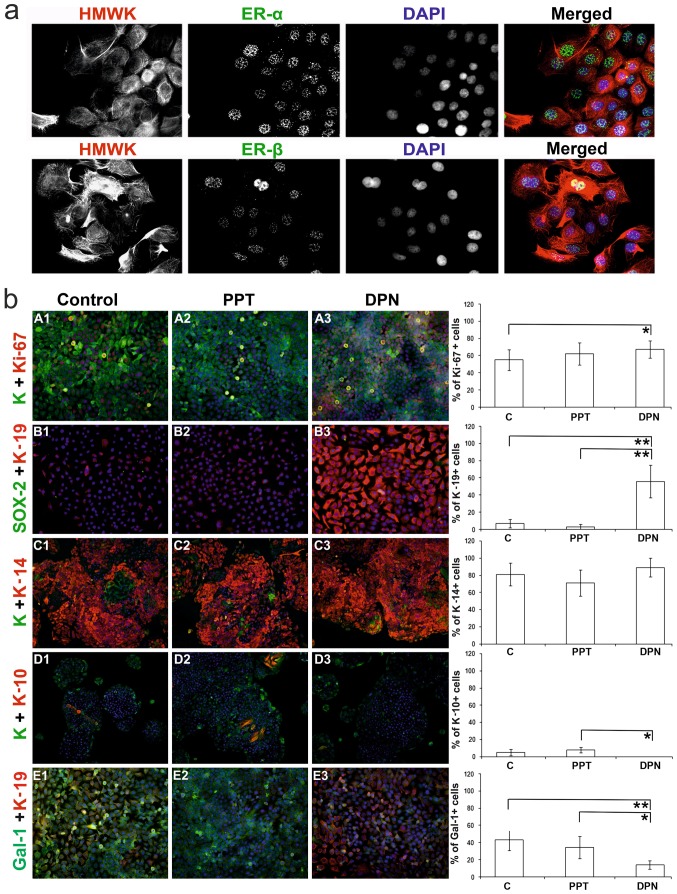

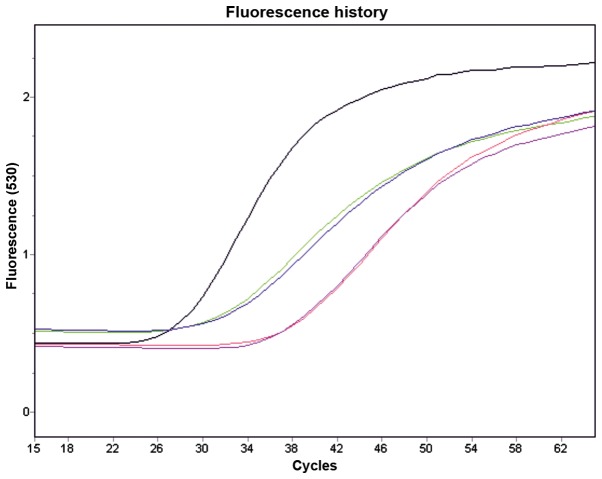

ER detection in HaCaT cells

We noted that the HaCaT keratinocytes expressed both ER-α and -β, mainly in the cell nuclei (Fig. 2a). ERs were detected by RT-qPCR, and the gene transcription of the ER-β receptor was slightly higher when compared to that of the ER-α receptor (Fig. 3). Cytochemically, in comparison to the control and PPT-treated cells, treatment with the ER-β agonist (DPN) increased the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells (Fig. 2b, panels A1-A3). It should be noted that targeting ER-β abolished galectin-1 expression, whereas the control and ER-α agonist-treated cells were positive for galectin-1 (Fig. 2b, panesl E1-E3).

Figure 2.

(a) Culture of HaCaT keratinocytes (magnification, ×600), which express both estrogen receptor (ER)-α and -β mainly in the cell nuclei; cytoskeleton is stained with high-molecular-weight keratins (HMWK), cell nuclei are visualized by DAPI. (b) HaCaT keratinocytes cultured under the influence of selective ER agonists; first line of horizontal panels (A1-A3, magnification, ×200): detection of the proliferation marker Ki-67 and wide-spectrum keratin; second horizontal panel (B1-B3, magnification, ×200): presence of keratin-19 (marker of poorly differentiated keratinocytes with stem-like phenotype) and Sox-2 (stem cels marker); third horizontal panel (C1-C3, magnification, ×100): positivity for keratin-14 (marker of poorly differentiated keratinocytes) and wide-spectrum keratin; fourth horizontal panel (D1-D3, magnification, ×100): expression of keratin-10 (marker of differentiated keratinocytes) and wide-spectrum keratin; fifth horizontal panel (E1-E3, magnification, ×100): presence of keratin-19 and galectin-1 (Gal-1). PPT-, 4,4′,4″-(4-propyl [1H] pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)-trisphenol, a selective ER-α agonist; DPN, 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile, a selective ER-β agonist; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. C, control; K, wide-spectrum keratin.

Figure 3.

Estrogen receptor (ER) expression in HaCaT cells evaluated by quantitative RT-qPCR. Black line, house keeping gene; green and blue lines, ER-β; red and purple, ER-α).

The majority (81±13%) of the HaCaT control cells expressed keratin-14 (Fig. 2b, panels C1-C3). Only a small percentage of the control cells expressed keratin-10 (5±4%; Fig. 2b, panels D1-D3) and keratin-19 (7±5%; Fig. 2b, panels B1-B3). The cells stimulated with the ER-α agonist (PPT) had similar percentages of keratin-based phenotypes (K10, 8±3%; K14, 71±15%; K19, 3±3%; Fig. 2b, panels B2, C2 and D2) compared to the untreated controls (Fig. 2b, panels B1, C1 and D1). The cells stimulated with the ER-β agonist (DPN) had less differentiated phenotypes, with a marked positivity of keratin-19 (64±19%) and the absence of keratin-10 (0±0%) (Fig. 2b, panels B3, C3 and D3). Of note, the level of keratin-14 following treatment with DPN remained relatively consistent (K14, 89±11%). In all the groups, no effects on the expression level of Sox-2 (0±0%) were observed (Fig. 2b, panels B1-B3).

Skin wounds

During the post-surgical period, all animals remained healthy and did not exhibit any clinical symptoms of infection. Of note, the inflammatory phase passed in all groups with no presence of PMNLs noted and only very minor occurrences of tissue macrophages at the sites of injury. The results of semi-quantitative analysis of the histological sections are summarized in Table III.

Table III.

Semi-quantitative analysis of histological structures/changes 21 days post-surgery (data are presented as the median).

| Group | Epithelialization | PMNLs | Fibroblasts | Luminized vessels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOV-C | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| OVX-C | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| OVX-PPT | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| OVX-DPN | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

NOV-C, control [sham-operated rats treated with the vehicle (1% DMSO)]; OVX-C, ovariectomized rats treated with the vehicle; OVX-PPT, ovariectomized rats treated with PPT; OVX-DPN, ovariectomized rats treated with DPN; PMNLs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

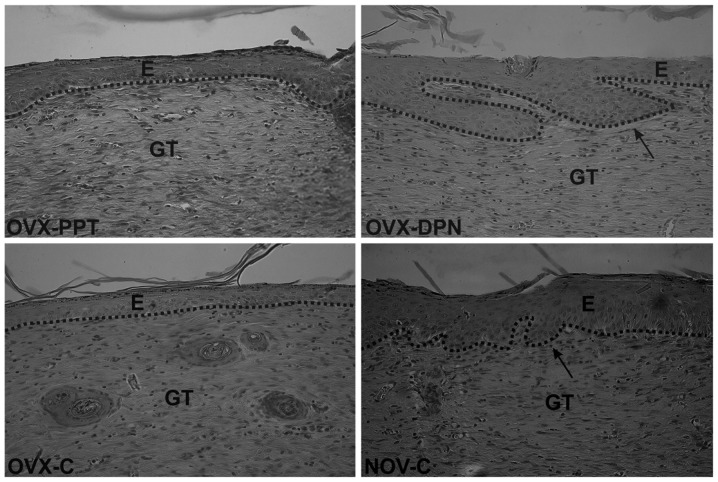

On day 21 after wounding, a thin keratin layer was present in all wounds (Fig. 4), demonstrating that a normal keratinocyte differentiation had occurred. However, differences were noted in the process of epidermal regeneration. In the rats from the OVX-C and OVX-PPT groups, we noted that hair follicle regeneration and epidermal thickening were both delayed (Fig. 4). Treatment with the ER-β agonist (Fig. 4; OVX-DPN) resulted in a normalized process of epidermal regeneration, comparable to that of the sham-operated animals (NOV-C). In comparison to both control groups (OVX-C and NOV-C), the number of luminized vessels slightly increased upon treatment with the estrogen agonists treatment (OVX-PPT and OVX-DPN). A moderate number of fibroblasts in the granulation tissues of all wounds was observed, reflecting the progression of in tissue fibrosis. Of note, no significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of the presence of luminized vessels or of fibroblasts.

Figure 4.

Healing of skin wounds 21 days post-surgery (magnification, ×400). The maturation phase of healing was noted in all groups, and differences were observed in epidermal regeneration, which was impaired in the ovariectomized rats treated with the vehicle (1% DMSO; OVX-C) and ovariectomized rats treated with the ER-α agonist, PPT (OVX-PPT. Black arrows indicate growing hair follicles in sham-operated vehicle-treated rats (NOV-C) and ovariectomized rats treated with the ER-β agonist, DPN (OVX-DPN). The dotted line distinguishes the epidermis from the granulation tissue; staining was done with H&E. E, epidermis; GT, granulation tissue; PPT-, 4,4′,4″-(4-propyl [1H] pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)-trisphenol, a selective ER-α agonist; DPN, 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile, a selective ER-β agonist.

Discussion

Monitoring markers for differentiation revealed that the ER-β agonist, DPN, decreases the expression of galectin-1 in HaCaT cells. The expression of this lectin is known to be sterol-sensitive (please see below), and this observation provides direction to further assessments of its impact on other members of the galectin network and also on glycosylation, making cells susceptible to galectins. These lectins can have site-specific additive or antagonistic effects, and when co-expressed they form a network, as in tumors (44–46). Therefore, their regulation may alter the clinical course of a tumor, and in this context, the phytoestrogen, genistein, and its potential chemopreventive effects on breast cancer also deserve attention (47,48). Following initial immunohistochemical detection of this class of tumors, galectin-1 has been shown to be upregulated in invasive breast carcinoma with a positive correlation with the TNM staging system (49,50). Fittingly, as previously demonstrated, the silencing of galectin-1 in a breast carcinoma model overcame breast cancer-associated immunosuppression, inhibited tumor growth and prevented metastatic disease (51). Of note, in our previous studies, we found that galectin-1 was upregulated during the early phases of wound healing (25,32). Since long-term estradiol deprivation enhances estrogen sensitivity (52), by upregulating ER-α expression, further studies focusing on this receptor are warranted in order to reduce tumor cell proliferation (53). Antagonizing ER-α, together with agonizing ER-β, may ameliorate galectin-1-induced immunosuppression in breast cancer; however, further consideration based on detailed network and glycosylation studies is necessary.

Although estrogen is considered a key regulator of wound healing, an incomplete understanding of the molecular mechanisms of action of estrogen, as well as the well-documented adverse effects of estrogens during menopause in clinical trials, preclude the common clinical use of ERT as a wound-healing treatment. One example of the negative effects of estrogens is that the activation of ER-α leads to a decrease in the tensile strength of wounds during the proliferation phase of healing (41,54), whereas the activation of ER-α and/or -β significantly increases this parameter during the early maturation phase (54). The ER-α agonist, TGF-β1-dependently increases fibroblast migration and keratinocyte proliferation. By contrast, the ER-β agonist does not affect cell migration (55,56) and increases keratinocyte proliferation in a TGF-β1-independent manner (57). Accordingly, in vivo experiments have shown that targeting ER-β, but not ER-α leads to accelerated re-epithelialization in mice (36) and rats (54). Furthermore, ER-α has been proven to be responsible for impaired wound healing in male mice (58). In the present study, we demonstrated that the pharmacological activation of ER-β, but not that of ER-α, led to a significant alteration in the pattern of differentiation and the proliferation activity of keratinocytes. In relation to markers, previous research has demonstrated that the ER-β agonist does not induce Sox-2 expression, a characteristic of stem-like properties (59), in keratin-19-positive cells.

In conclusion, our data suggest that marker-based cytochemical monitoring provides new information on ER-modulated keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation. The stimulation of epidermal regeneration may ensue after treating wounds with an ER-β agonist. In order to activate the TGF-β1 pathway to this end, ER-α should be targeted (57). However, the nature of the animal model and restrictions on extrapolations must be taken into consideration, as we did in our study, by combining a human in vitro model with in vivo data on rats.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Iva Burdová, Ladislava Kratinová and Marcela Blažeková for providing technical assistance. The present study was supported in part by the Grant Agency of Ministry of the Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic (VEGA 1/0299/13, VEGA 1/0404/15, and VEGA 1/0048/15), the Agency for Science and Research under the contract no. APVV-0408-12 and APVV-14-0731, the Charles University in Prague (project for support of specific university student research, project UNCE 204013 and project PRVOUK 27), as well as by the project BIOCEV (Biotechnology and Biomedicine Centre of the Academy of Sciences and Charles University in Vestec - CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0109, from the European Regional Development Fund) and by EC funding for GlycoHIT (contract no. 260600) and the Marie Curie ITN network GLYCOPHARM (contract no. 317297).

References

- 1.Calleja-Agius J, Brincat M. The effect of menopause on the skin and other connective tissues. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:273–277. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2011.613970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall G, Phillips TJ. Estrogen and skin: the effects of estrogen, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.039. quiz 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kloepper JE, Tiede S, Brinckmann J, Reinhardt DP, Meyer W, Faessler R, Paus R. Immunophenotyping of the human bulge region: the quest to define useful in situ markers for human epithelial hair follicle stem cells and their niche. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:592–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer DF. Postmenopausal skin and estrogen. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(Suppl 2):2–6. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.705392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashcroft GS, Mills SJ, Lei K, Gibbons L, Jeong MJ, Taniguchi M, Burow M, Horan MA, Wahl SM, Nakayama T. Estrogen modulates cutaneous wound healing by downregulating macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1309–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI16288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilliver SC, Emmerson E, Bernhagen J, Hardman MJ. MIF: a key player in cutaneous biology and wound healing. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashcroft GS, Dodsworth J, van Boxtel E, Tarnuzzer RW, Horan MA, Schultz GS, Ferguson MW. Estrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing associated with an increase in TGF-beta1 levels. Nat Med. 1997;3:1209–1215. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Bai J, Ji X, Li R, Xuan Y, Wang Y. Comprehensive char-acterization of four different populations of human mesenchymal stem cells as regards their immune properties, proliferation and differentiation. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:695–704. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu T, Park HC, Son KM, Kwon JH, Park JC, Yang HC. Effects of thymosin β4 on wound healing of rat palatal mucosa. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:816–821. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Du L, Wen Z, Yang Y, Li J, Dong Z, Zheng G, Wang L, Zhang X, Wang C. Sex determining region Y-box 2 inhibits the proliferation of colorectal adenocarcinoma cells through the mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:59–66. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Törmä H, Lindberg M, Berne B. Skin barrier disruption by sodium lauryl sulfate-exposure alters the expressions of involucrin, transglutaminase 1, profilaggrin, and kallikreins during the repair phase in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1212–1219. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedberg IM, Tomic-Canic M, Komine M, Blumenberg M. Keratins and the keratinocyte activation cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichelt J, Büssow H, Grund C, Magin TM. Formation of a normal epidermis supported by increased stability of keratins 5 and 14 in keratin 10 null mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1557–1568. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter CA, Jolly DG, Worden CE, Sr, Hendren DG, Kane CJ. Platelet-rich plasma gel promotes differentiation and regeneration during equine wound healing. Exp Mol Pathol. 2003;74:244–255. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4800(03)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peryassu MA, Cotta-Pereira G, Ramos-e-Silva M, Filgueira AL. Expression of keratins 14, 10 and 16 in marginal keratoderma of the palms. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2005;13:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michel M, Török N, Godbout MJ, Lussier M, Gaudreau P, Royal A, Germain L. Keratin 19 as a biochemical marker of skin stem cells in vivo and in vitro: keratin 19 expressing cells are differentially localized in function of anatomic sites, and their number varies with donor age and culture stage. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1017–1028. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dvoránková B, Smetana K, Jr, Chovanec M, Lacina L, Stork J, Plzáková Z, Galovicová M, Gabius HJ. Transient expression of keratin 19 is induced in originally negative interfollicular epidermal cells by adhesion of suspended cells. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:525–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabius HJ, André S, Jiménez-Barbero J, Romero A, Solís D. From lectin structure to functional glycomics: principles of the sugar code. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.André S, Kaltner H, Manning JC, Murphy PV, Gabius HJ. Lectins: getting familiar with translators of the sugar code. Molecules. 2015;20:1788–1823. doi: 10.3390/molecules20021788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solís D, Bovin NV, Davis AP, Jiménez-Barbero J, Romero A, Roy R, Smetana K, Jr, Gabius HJ. A guide into glycosciences: How chemistry, biochemistry and biology cooperate to crack the sugar code. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:186–235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villalobo A, Nogales-Gonzalez A, Gabius HJ. A guide to signaling pathways connecting protein-glycan interaction with the emerging versatile effector functionality of mammalian lectins. Trends Glycosci Glyc. 2006;18:1–37. doi: 10.4052/tigg.18.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaltner H, Gabius HJ. A toolbox of lectins for translating the sugar code: the galectin network in phylogenesis and tumors. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:397–416. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzenmaier EM, André S, Kopitz J, Gabius HJ. Impact of sodium butyrate on the network of adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins in human colon cancer in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:5429–5438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy N, Bronckart Y, Camby I, Legendre H, Lahm H, Kaltner H, Hadari Y, Van Ham P, Yeaton P, Pector JC, et al. Galectin-8 expression decreases in cancer compared with normal and dysplastic human colon tissue and acts significantly on human colon cancer cell migration as a suppressor. Gut. 2002;50:392–401. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klíma J, Lacina L, Dvoránková B, Herrmann D, Carnwath JW, Niemann H, Kaltner H, André S, Motlík J, Gabius HJ, Smetana K., Jr Differential regulation of galectin expression/reactivity during wound healing in porcine skin and in cultures of epidermal cells with functional impact on migration. Physiol Res. 2009;58:873–884. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dvořánková B, Szabo P, Lacina L, Gal P, Uhrova J, Zima T, Kaltner H, André S, Gabius HJ, Sykova E, et al. Human galectins induce conversion of dermal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and production of extracellular matrix: potential application in tissue engineering and wound repair. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;194:469–480. doi: 10.1159/000324864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teichberg VI, Silman I, Beitsch DD, Resheff G. A beta-D-galactoside binding protein from electric organ tissue of Electrophorus electricus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1383–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabius HJ, Engelhardt R, Cramer F, Bätge R, Nagel GA. Pattern of endogenous lectins in a human epithelial tumor. Cancer Res. 1985;45:253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smetana K, Jr, Szabo P, Gál P, André S, Gabius HJ, Kodet O, Dvořánková B. Emerging role of tissue lectins as microenviron-mental effectors in tumors and wounds. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:293–309. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smetana K, Jr, André S, Kaltner H, Kopitz J, Gabius HJ. Context-dependent multifunctionality of galectin-1: a challenge for defining the lectin as therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:379–392. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.750651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Moussodia RO, Murzeau C, Sun HJ, Klein ML, Vértesy S, André S, Roy R, Gabius HJ, Percec V. Dissecting molecular aspects of cell interactions using glycodendrimer-somes with programmable glycan presentation and engineered human lectins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:4036–4040. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gál P, Vasilenko T, Kostelníková M, Jakubco J, Kovác I, Sabol F, André S, Kaltner H, Gabius HJ, Smetana K., Jr Open wound healing in vivo: Monitoring binding and presence of adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins in rat skin during the course of complete re-epithelialization. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2011;44:191–199. doi: 10.1267/ahc.11014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper D, Norling LV, Perretti M. Novel insights into the inhibitory effects of Galectin-1 on neutrophil recruitment under flow. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1459–1466. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1207831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emmerson E, Hardman MJ. The role of estrogen deficiency in skin ageing and wound healing. Biogerontology. 2012;13:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9322-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krahn-Bertil E, Dos Santos M, Damour O, Andre V, Bolzinger MA. Expression of estrogen-related receptor beta (ERRβ) in human skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:719–723. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell L, Emmerson E, Davies F, Gilliver SC, Krust A, Chambon P, Ashcroft GS, Hardman MJ. Estrogen promotes cutaneous wound healing via estrogen receptor β independent of its antiinflammatory activities. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1825–1833. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo J, Duckles SP, Weiss JH, Li X, Krause DN. 17β-Estradiol prevents cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction by an estrogen receptor-dependent mechanism in astrocytes after oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:2151–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaltner H, Seyrek K, Heck A, Sinowatz F, Gabius HJ. Galectin-1 and galectin-3 in fetal development of bovine respiratory and digestive tracts. Comparison of cell type-specific expression profiles and subcellular localization. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s004410100457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gál P, Kilík R, Mokrý M, Vidinský B, Vasilenko T, Mozeš S, Bobrov N, Tomori Z, Bober J, Lenhardt L. Simple method of open skin wound healing model in corticosteroid-treated and diabetic rats: standardization of semi-quantitative and quantitative histological assessments. Vet Med. 2008;53:652–659. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gál P, Novotný M, Vasilenko T, Depta F, Šulla I, Tomori Z. Decrease in wound tensile strength following post-surgical estrogen replacement therapy in ovariectomized rats during the early phase of healing is mediated via ER-alpha rather than ER-beta: a preliminary report. J Surg Res. 2010;159:e25–e28. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wegorzewska IN, Walters K, Weiser MJ, Cruthirds DF, Ewell E, Larco DO, Handa RJ, Wu TJ. Postovariectomy weight gain in female rats is reversed by estrogen receptor alpha agonist, propylpyrazoletriol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:67.e1–67.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gál P, Toporcer T, Vidinský B, Mokrý M, Grendel T, Novotný M, Sokolský J, Bobrov N, Toporcerová S, Sabo J, Mozes S. Postsurgical administration of estradiol benzoate decreases tensile strength of healing skin wounds in ovariectomized rats. J Surg Res. 2008;147:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Ruderisch H, Fischer C, Detjen KM, Welzel M, Wimmel A, Manning JC, André S, Gabius HJ. Tumor suppressor p16 INK4a: Downregulation of galectin-3, an endogenous competitor of the pro-anoikis effector galectin-1, in a pancreatic carcinoma model. FEBS J. 2010;277:3552–3563. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amano M, Eriksson H, Manning JC, Detjen KM, André S, Nishimura S, Lehtiö J, Gabius HJ. Tumour suppressor p16(INK4a) - anoikis-favouring decrease in N/O-glycan/cell surface sialylation by down-regulation of enzymes in sialic acid biosynthesis in tandem in a pancreatic carcinoma model. FEBS J. 2012;279:4062–4080. doi: 10.1111/febs.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawson H, André S, Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I, Gabius HJ. The growing galectin network in colon cancer and clinical relevance of cytoplasmic galectin-3 reactivity. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3053–3059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shon YH, Park SD, Nam KS. Effective chemopreventive activity of genistein against human breast cancer cells. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;39:448–451. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2006.39.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:52–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabius HJ, Brehler R, Schauer A, Cramer F. Localization of endogenous lectins in normal human breast, benign breast lesions and mammary carcinomas. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1986;52:107–115. doi: 10.1007/BF02889955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung EJ, Moon HG, Cho BI, Jeong CY, Joo YT, Lee YJ, Hong SC, Choi SK, Ha WS, Kim JW, et al. Galectin-1 expression in cancer-associated stromal cells correlates tumor invasiveness and tumor progression in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2331–2338. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dalotto-Moreno T, Croci DO, Cerliani JP, Martinez-Allo VC, Dergan-Dylon S, Méndez-Huergo SP, Stupirski JC, Mazal D, Osinaga E, Toscano MA, et al. Targeting galectin-1 overcomes breast cancer-associated immunosuppression and prevents metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1107–1117. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santen RJ, Song RX, Zhang Z, Kumar R, Jeng MH, Masamura A, Lawrence J, Jr, Berstein L, Yue W. Long-term estradiol deprivation in breast cancer cells up-regulates growth factor signaling and enhances estrogen sensitivity. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S61–S73. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anbalagan M, Rowan BG. Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 Jan 15; doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.016. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novotný M, Vasilenko T, Varinská L, Smetana K, Jr, Szabo P, Sarišský M, Dvořánková B, Mojžiš J, Bobrov N, Toporcerová S, et al. ER-α agonist induces conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, while ER-β agonist increases ECM production and wound tensile strength of healing skin wounds in ovariectomised rats. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:703–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevenson S, Nelson LD, Sharpe DT, Thornton MJ. 17beta-estradiol regulates the secretion of TGF-beta by cultured human dermal fibroblasts. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19:1097–1109. doi: 10.1163/156856208784909354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevenson S, Sharpe DT, Thornton MJ. Effects of oestrogen agonists on human dermal fibroblasts in an in vitro wounding assay. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:988–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merlo S, Frasca G, Canonico PL, Sortino MA. Differential involvement of estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta in the healing promoting effect of estrogen in human keratinocytes. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:189–197. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilliver SC, Emmerson E, Campbell L, Chambon P, Hardman MJ, Ashcroft GS. 17beta-estradiol inhibits wound healing in male mice via estrogen receptor-alpha. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2707–2721. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grinnell KL, Bickenbach JR. Skin keratinocytes pre-treated with embryonic stem cell-conditioned medium or BMP4 can be directed to an alternative cell lineage. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:685–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]