Significance

This work describes an intriguing strategy for the formation of hydrogel-laden multiform structures utilizing paper sheets and suggests a route for trachea tissue engineering. It combines concepts extracted from paper origami, functional thin polymer coating, and thin hydrogel layering on top of the paper scaffolds. A computer-aided design-based lock-and-key arrangement was used for folding the sheets into multiform structures with spatial arrangements. With encapsulating cells in hydrogel-laden paper, the scaffold system was able to deliver biological cues in vivo. In this work, we have successfully applied an origami-based tissue engineering approach to the trachea regeneration model.

Keywords: paper scaffolds, origami, tissue engineering, initiated chemical vapor deposition, hydrogel

Abstract

In this study, we present a method for assembling biofunctionalized paper into a multiform structured scaffold system for reliable tissue regeneration using an origami-based approach. The surface of a paper was conformally modified with a poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) layer via initiated chemical vapor deposition followed by the immobilization of poly-l-lysine (PLL) and deposition of Ca2+. This procedure ensures the formation of alginate hydrogel on the paper due to Ca2+ diffusion. Furthermore, strong adhesion of the alginate hydrogel on the paper onto the paper substrate was achieved due to an electrostatic interaction between the alginate and PLL. The developed scaffold system was versatile and allowed area-selective cell seeding. Also, the hydrogel-laden paper could be folded freely into 3D tissue-like structures using a simple origami-based method. The cylindrically constructed paper scaffold system with chondrocytes was applied into a three-ring defect trachea in rabbits. The transplanted engineered tissues replaced the native trachea without stenosis after 4 wks. As for the custom-built scaffold system, the hydrogel-laden paper system will provide a robust and facile method for the formation of tissues mimicking native tissue constructs.

The living organ changes its shape from a sheet-like arrangement with primitive cells to mature three-dimensional (3D) structures through morphogenetic processes (1–3). To date, a wide range of biomaterials have been used for the total or partial replacement of damaged organs and/or tissue structures (4–7). As the functions of the living organ are realized by periodic changes in the spatial arrangement of tissue elements, multiform scaffold systems mimicking the native tissue are desired. Mold-casting and electrospinning, among various other methods, have been introduced to fabricate diverse scaffolds (8, 9). These fabrication processes, however, possess limitations for organ-like structure productions. Although recent progress in tissue engineering has focused on using 3D printer schemes, there are still limitations such as the shortage of appropriate printing materials and technical challenges related to the sensitivity of living cells (10–12).

Paper-based scaffolds have been used previously for cell culture platforms (13), high-throughput biochemical assay platforms (14), and a point-of-care diagnostic system (15). As a nature-originated substrate, paper has attracted enormous research interest for applications in tissue engineering (16). Cellulose-based paper may serve as a promising material for tissue engineering as it contains macroporous structures that allow nutrient transport and oxygenation (13). In this regard, paper origami is a simple alternative approach for fabricating a multiform scaffold. Based on computer-aided design (CAD) planar figures, a variety of shaped scaffolds could be designed using biofunctionalized paper.

In this report, a vapor-phase method, initiated chemical vapor deposition (iCVD), was used to deposit a functional polymer film onto the surface of paper substrates. Because the iCVD process is performed in the vapor phase at a mild substrate temperature, this process preserves the topological microstructures of various substrates without damaging them, only rendering the paper surface biofunctionalizable (17). Several iCVD-based polymer coatings have been successfully adopted for surface modification in biomedical fields (16, 18, 19). For example, the technique was used to fabricate a functional scaffold platform for bone tissue regeneration and to immobilize peptides for the enhancement of osteogenic differentiation (16, 18).

In this study, we report and evaluate the development of hydrogel-laden paper scaffolds for origami-based tissue engineering. A hydrogel layer encapsulated with chondrocytes was formed on the poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) (PSMa)-coated paper via iCVD. PSMa was immobilized with poly-l-lysine (PLL) to induce a strong electrostatic adhesion with the thin alginate hydrogel layer, allowing the hydrogel to retain its structure upon folding. Furthermore, through a computer-aided design, the hydrogel-laden paper was folded into multiform organ-like structures. For further applications in tissue engineering, rabbit trachea was removed and successfully replaced with a cylindrically shaped scaffold containing rabbit chondrocytes. These findings showed that a simple and bottom-up method to fabricate implantable hydrogel-laden paper scaffolds for origami-based tissue engineering is possible.

Results and Discussion

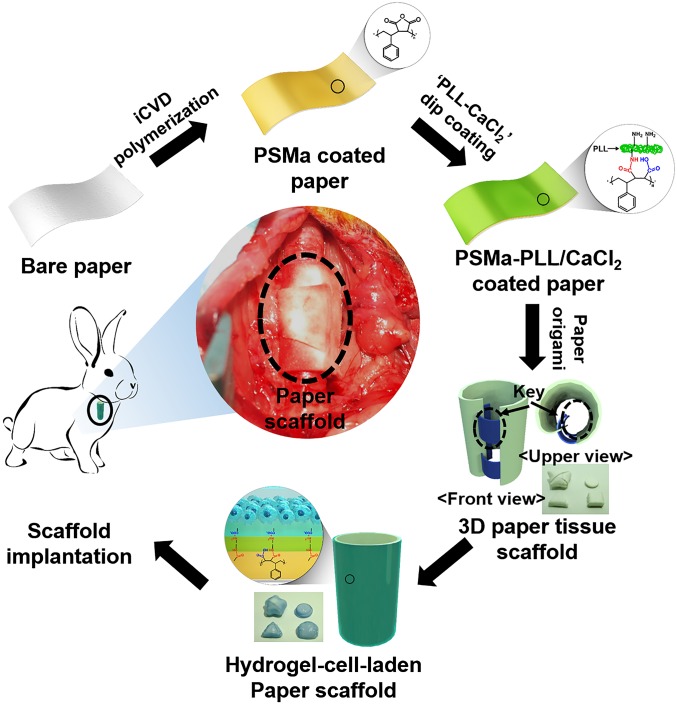

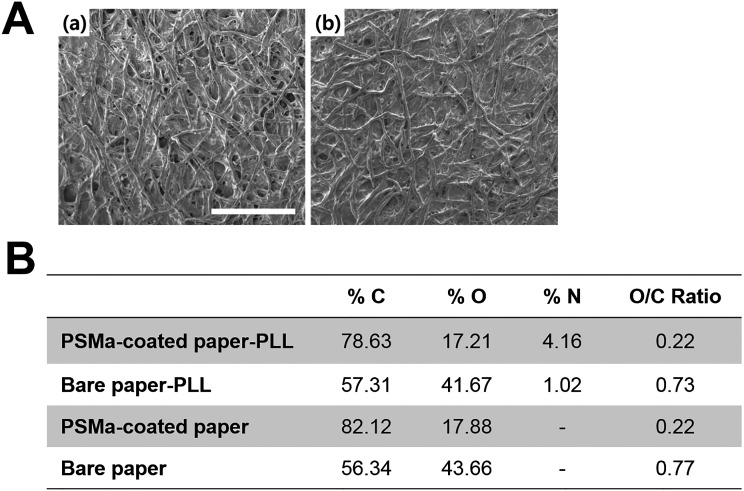

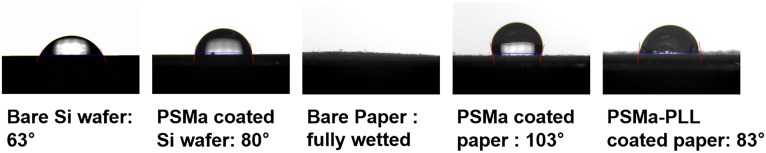

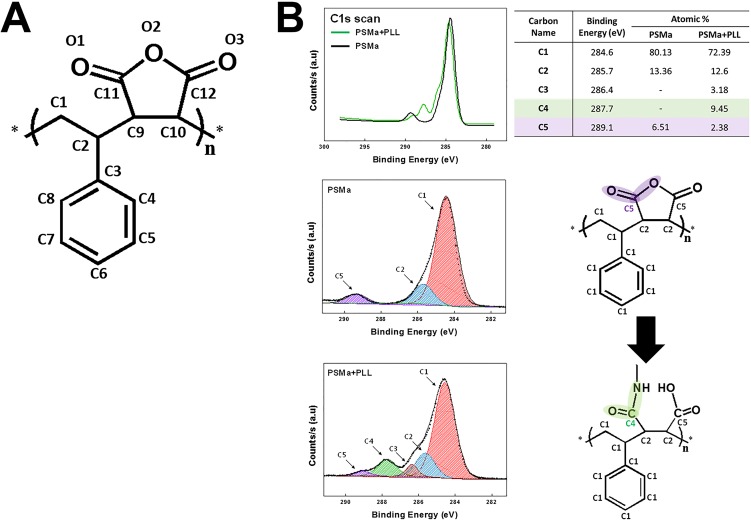

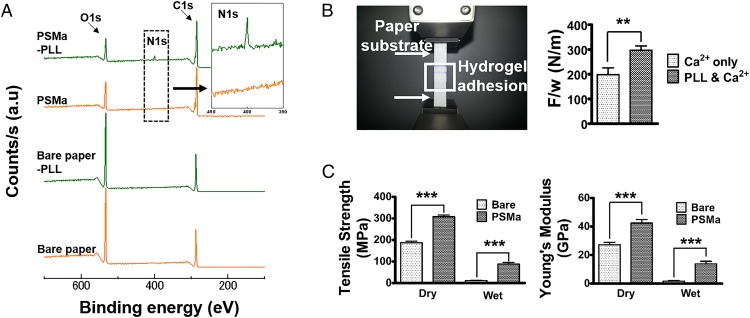

To develop a hydrogel-laden paper for origami-based tissue engineering applications, a paper substrate was modified by applying a functional polymer thin film via iCVD followed by thin hydrogel layer formation (Fig. 1). Through iCVD, a polymer film of PSMa was deposited uniformly on the paper surface (Fig. S1) (20). The scanning electron microscope (SEM) images showed that the surface morphology of the PSMa-coated paper was practically identical to that of bare paper (Fig. S2A). The 500-nm-thick iCVD PSMa film encapsulated the microfibrous structure of the paper with proper hydrophobicity (water contact angle of 103°) (Fig. S3) and kept the paper scaffold from rupture/deformation in the wet culture medium, ensuring the mechanical stability of the paper scaffold under wet conditions. The chemical analysis indicated that the deposition of PSMa copolymer film altered the surface chemical compositions of the paper. The oxygen to carbon ratio (O/C) ratio of the PSMa-coated paper surface in the X-ray photoelectron spectrometry (XPS) survey scan (Fig. S2B) was 1:4, which is fully consistent with the chemical structure of the alternating repeat unit of the PSMa polymer, which is composed of 80% carbon and 20% oxygen (Fig. S4A). Furthermore, functionalities in the PSMa film readily provided reactive anhydride groups to form a covalent bond with the amine functionalities in the PLL, leading to a grafting of cationic PLL onto the paper surface (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2B) (21). The PLL-immobilized PSMa substrate displayed a newly emerged, strong nitrogen (N1s) peak at 400 eV (Fig. 2A). The well-known reaction between maleic anhydride and nucleophile has been widely used for biomedical applications including cell chips and microarrays (20, 22). The coupling reaction that forms a strong binding between the amine functionalities in PLL and the anhydrides in PSMa has also been further confirmed by high-resolution scans of C1s (Fig. S4B). We also checked the PSMa coating uniformity after folding the coated paper by estimating SEM at three different folding spots (Fig. S5). The SEM analysis showed that there is no evident change like a flaking-off property in the PSMa-coated paper without highly textured surface morphology even after folding the coated paper. These results clearly demonstrated that the PLL was covalently conjugated on the PSMa film. The observation strongly infers that the iCVD PSMa allowed the grafting of the cationic PLL on the substrates.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of fabrication of hydrogel-cell–laden paper. Bare paper was coated with PSMa via iCVD, followed by dip coating in an aqueous solution of PLL and calcium chloride. After surface modification, the paper was soaked in a cell-alginate solution for 30 min for gelation. Four different folded paper scaffolds structures were fabricated using paper origami—star, cylindrical, triangular, and square pillar structure—and precisely coated with hydrogel.

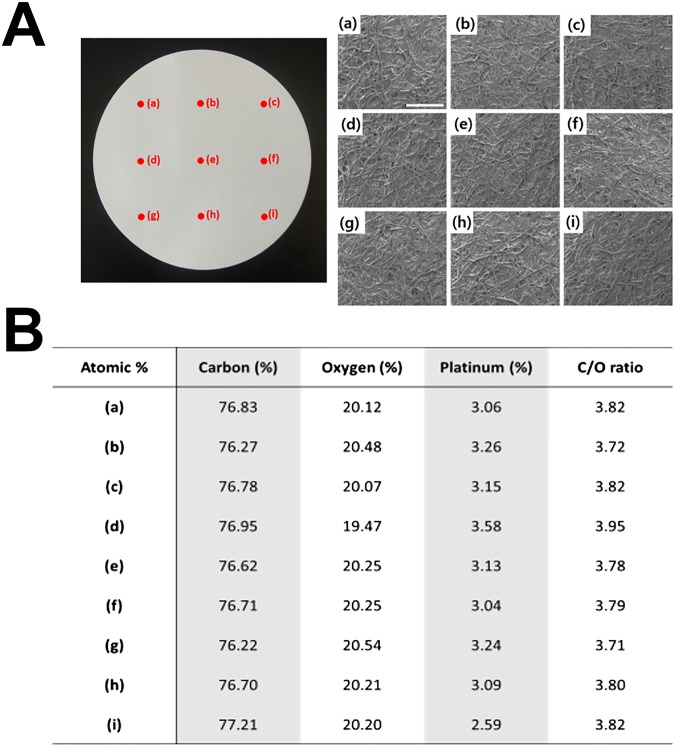

Fig. S1.

SEM-EDS analysis at nine different spots on PSMa-coated paper with a diameter of 125 mm. A quantitative EDS analysis was also performed during the SEM measurement to check the atomic composition of the surface; it showed that the surface composition of the bare paper changed substantially to that of the PSMa-coated paper. (A) PSMa-coated paper and SEM image of each region on the PSMa-coated paper (a–i). (Scale bar, 500 μm.) (B) The surface atomic percentage of bare paper and PSMa-coated paper extracted from the EDS analysis. The SEM and EDS analyses clearly demonstrated that the paper surface was uniformly covered with iCVD PSMa without alterations to the highly textured surface morphology of the paper substrate.

Fig. S2.

(A) SEM image of (a) bare paper and (b) PSMa-coated paper. (Scale bar, 500 μm.) (B) Summary of quantitative analysis of the XPS survey scan results for substrates: bare paper, PLL-treated bare paper, PSMa-coated filter paper, and PLL-treated, PSMa-coated filter paper.

Fig. S3.

Water contact angles (WCA) of PSMa-coated paper and PSMa-coated paper reacted with PLL. WCA measurement for bare paper was impossible because the water droplet was completely absorbed by the substrate.

Fig. S4.

(A) Expected repeating unit of poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) (PSMa) copolymer films. Each repeating unit had 12 carbons and 3 oxygens. (B) The high-resolution scans of C1s and N1s from PSMa and PLL-grafted PSMa film. The C1s envelope of the iCVD PSMa and the PLL-grafted PSMa were deconvoluted to five peaks, corresponding to C1 (C-C, 284.6 eV), C2 [C-C(O) = O, 285.7 eV], C3 (CH2-NH2, 286.4 eV), C4 (N-C = O, 287.7 eV), and C5 (C(O) = O, 289.1 eV) bindings. Compared with the C1s XPS spectrum of bare PSMa, the spectrum of PLL-bonded PSMa showed a newly emerged energy peak at 287.7 eV assigned to an amide group, which is 3.1 eV higher than the main C1s peak. In addition, peak reduction of the C5 peaks around 289.1 eV was also observed. This was assigned to a carbon atom in the ester linkage (O-C = O) of the anhydride component and indicated an opening in the anhydride ring to form amide functionalities (N-C = O) during the conjugation reaction. The appearance of the C3 peak representing the amine linkage (CH2-NH2) on the spectrum of PLL-bonded PSMa is most probably attributable to the grafted PLL layer on the PSMa.

Fig. 2.

Functionalization of the paper substrate. (A) XPS survey scan spectra for substrates: bare paper, PLL-treated bare paper, PSMa-coated filter paper, and PLL-treated PSMa-coated filter paper. All substrates used were filter papers. (B) Single lap test for adhesion strength of alginate gels (Left). Two substrates coated with PSMa-Ca2+ and PSMa-PLL/Ca2+ were glued using alginate gel. Adhesion strength between alginate gel and the two different types of modified substrate: Ca2+ only and Ca2+ and PLL (Right). Forces were loaded at failure points; F, normalized by the width of the joint; w, for lap joints attached using alginate gel (n = 10). (C) Tensile strength (Left) and Young’s Modulus (Right) obtained from Universal Testing Machine (UTM) analysis. Tensile strength and Young’s Modulus of substrates were measured under dry and wet conditions (n = 10).

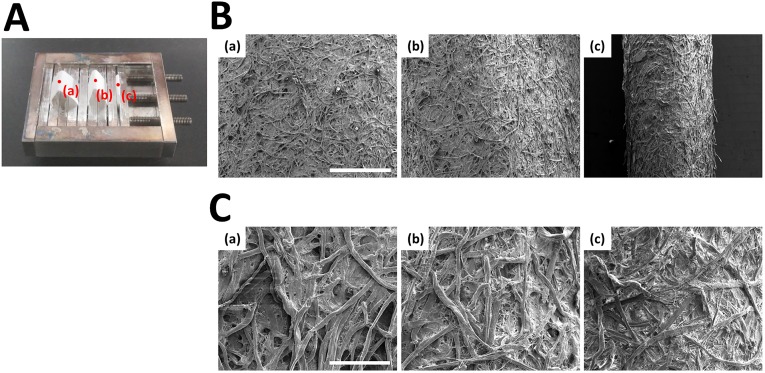

Fig. S5.

SEM analysis at three different folding spots of PSMa-coated paper. (A) Three different folding spots of PSMa-coated paper (a–c). (B and C) SEM images of regions indicated by red spots. (Scale bar: B, 1 mm; C, 200 μm.)

The grafted PLL layer on the paper surface functions as a linker layer allowing the cell-laden alginate hydrogel to attach stably onto the surface of the paper scaffold. The cell-laden alginate solution was dispensed on the cationic PLL-grafted substrate, and the negatively charged alginate was bound tightly to the PLL by the electrostatic attraction. The gelation of the alginate was also achieved spontaneously by the Ca2+ initially included in the PLL solution. When the alginate solution was dispensed on the PLL surface, the Ca2+ on the surface of the paper scaffold was released into the alginate solution to form a hydrogel that bound firmly to the surface of the paper scaffold (Movie S1). A single lap shear test showed that the average adhesion force between the alginate gel and the paper bound to the PLL layer was about 297 ± 0.18 N/m, which was 49% better than that of the specimen without a PLL layer, 200 ± 0.30 N/m, confirming the PLL-mediated attachment of the cell-laden alginate gel to the paper scaffold (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the PSMa-coated paper material displayed considerably higher values for tensile strength and Young’s Modulus even under wet conditions, whereas bare paper showed extremely poor mechanical strength under the same wet conditions (Fig. 2C).

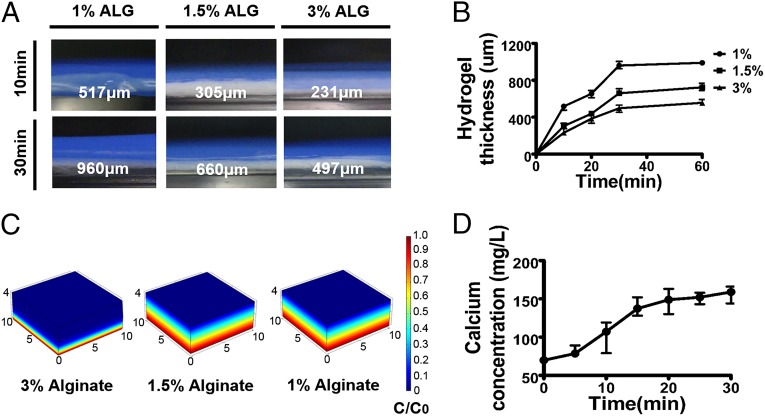

Hydrogel thickness and cross-linking density has a significant influence on cell viability, oxygen supply, and nutrient diffusion (23–25). The hydrogel thickness on the paper-based scaffold was directly governed by the alginate concentration and reaction time. Increase of the gelation time resulted in the gradual increase of the hydrogel thickness, ranging from 517 μm (10 min) to 960 μm (30 min) for a 1% (wt/vol) aqueous alginate solution and from 231 μm (10 min) to 497 μm (30 min) for a 3% (wt/vol) alginate solution (Fig. 3 A and B). Assuming a constant Ca2+ flux toward the alginate solution, the increased alginate concentration would lead to rapid consumption of the Ca2+ ions by cross-linking reactions near the surface of the paper scaffold, resulting in a thinner hydrogel layer. As the gelation time increased, the total amount of Ca2+ that diffused in would also increase, leading to a thicker hydrogel on the paper scaffold. Additionally, we hypothesized that increasing the hydrogel concentration reduced the Ca2+ diffusion length as the diffusion coefficient for Ca2+ exponentially declined. To evaluate these hypotheses, we simulated the scenarios using COMSOL Multiphysics (COMSOL). The data indicated that the decrease in the diffusion coefficient occurred due to the high concentration of alginate with greater cross-linking density. The Ca2+ diffusion length according to hydrogel concentration showed a precise correlation with the observed hydrogel thickness pattern (Fig. 3C). Moreover, it took less than 30 min to fabricate the alginate layer as the total amount of Ca2+ that diffused in became saturated within 30 min (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, alginate concentration-dependent swelling ratio changes and corresponding mechanical property changes were also observed (Figs. S6 and S7). From the change in mechanical and swelling properties, we determined that 1% (wt/vol) alginate would be suitable for further tissue-engineering applications, as it showed high degrees of swelling ratio as well as stable mechanical properties. These data demonstrate that hydrogel thickness can be controlled in the range of 200 μm to 1 mm.

Fig. 3.

Fabrication of hydrogel-laden paper scaffolds. (A) Photographs showing the side view of the hydrogel on paper scaffold. (B) The hydrogel thickness was measured at desired time points (10, 20, 30, and 60 min) with various hydrogel percentages [1, 1.5, and 3% (wt/vol) (n = 4)]. Profile of calcium release from paper-based iCVD substrate by (C) COMSOL simulation and (D) experiment (n = 4).

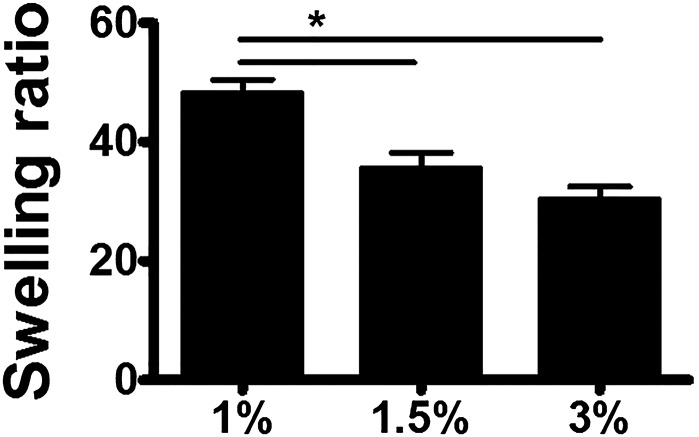

Fig. S6.

Equilibrium mass swelling ratios for hydrogels according to hydrogel percentage (wt/vol). Data are means ± SD; *P < 0.05 (n = 4).

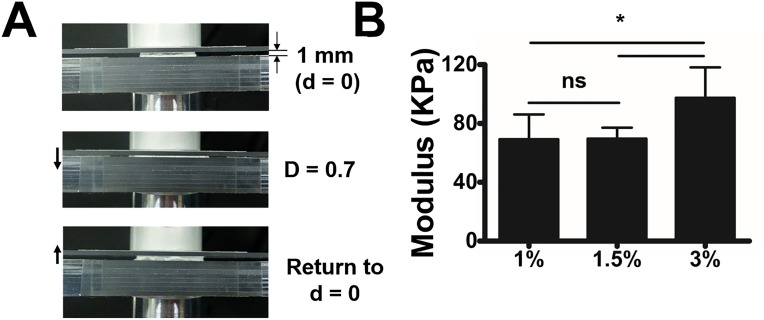

Fig. S7.

(A) Compression test set for measuring elastic modulus of alginate gels. Compression was applied until the alginate gel was completely crushed. (B) Elastic moduli of alginate gels obtained from compression test. Data are means ± SD; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant; n = 4.

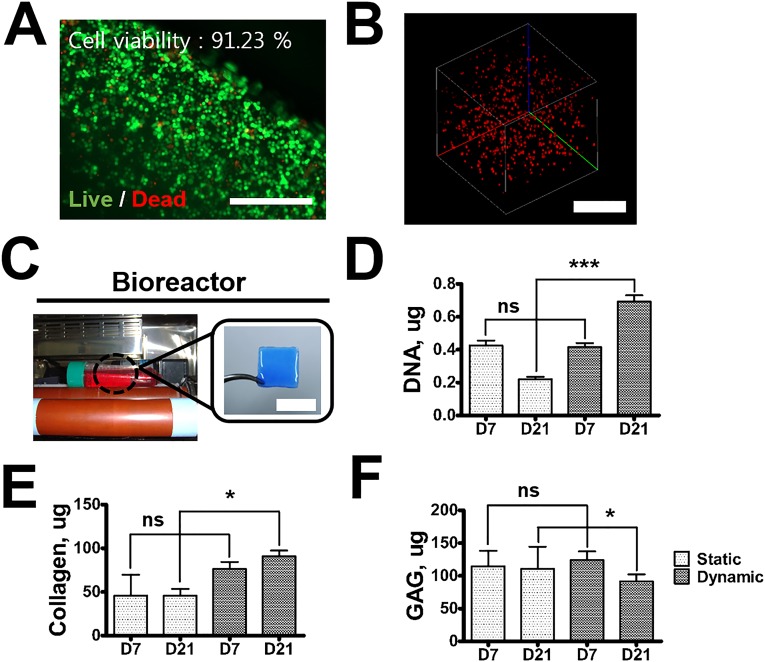

We further explored the use of paper substrates as the tissue-engineering platform for in vitro and in vivo culture. To this end, a hydrogel layer with rabbit articular chondrocytes (1 × 107 cells/mL) coated on the PSMa-modified paper (1 × 1 cm) was prepared and incubated in two different environments: dynamic culture in a modified bioreactor (9–11 rpm) and static culture. The chondrocytes survived the encapsulation process and maintained their viability in the 3D alginate hydrogels (Fig. S8 A and B). In the dynamic culture, the metabolic activity of cells in hydrogel was more up-regulated than in the static culture, and the amount of DNA, collagen, and glycosaminoglycan (GAGs) in the sample increased continuously until day 21 (Fig. S8). The hydrogel-laden paper was also able to support cartilaginous tissue formation in vivo (Fig. S9).

Fig. S8.

In vitro cartilage tissue engineering. (A) Live/dead image of chondrocytes encapsulated in alginate. (Scale bar, 400 μm.) (B) Cells labeled with PKH 26 encapsulated in 3D alginate (Scale bar, 500 μm.) (C–F) Sample was incubated in two different environments: dynamic culture in a modified bioreactor (rpm, 9–11) (C) and static culture. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) Engineered cartilage tissues were analyzed. GAG (D), collagen (E), and DNA (F) assays. Data are means ± SD; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant; n = 4.

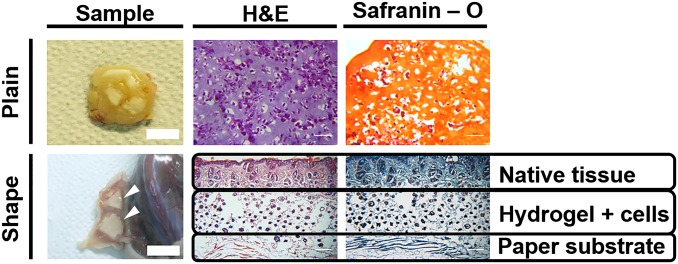

Fig. S9.

Photographs of plain and shaped samples with chondrocytes after implantation in BALB/c-nude mice at 6 wk and histologic evaluation by hematoxylin-eosin and Safranin-O staining. In triangular and pillar-shaped scaffolds (indicated by white arrowheads), the structure maintained its shape without dislocation of the hydrogel membrane and attached to the normal native tissue without granulation. (Scale bar, 1 cm.)

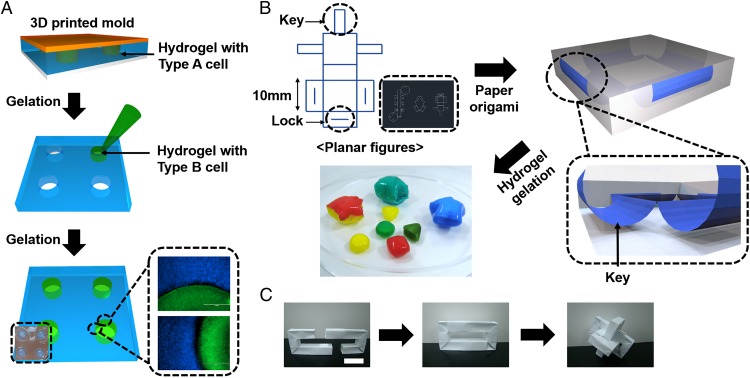

We applied a prepatterned mold onto an PSMa-modified paper substrate to fabricate a multi-cell-culture platform that could be further used in origami-based tissue engineering. Placement of a prepatterned mold with a defined shape on top of the paper substrate, followed by injection of alginate solution mixed with labeled cells, resulted in spatially patterned gelation of cell-laden hydrogel (Fig. 4A). In this regard, using large area paper and a prepatterned mold, this paper-scaffold platform could be developed into a scalable level to build a full-sized organ with multi-arrays of different cell types. Furthermore, by applying alginate solutions with two different cell types on each side of the paper substrate, two distinct cell types can be located in a multilevel format (Movie S2). It is well appreciated that multiform-structured shapes can be readily reconfigured by using CAD (Fig. 4B). To construct arbitrary shapes mimicking various types of tissues, we used the lock-and-key method to fabricate complexly shaped scaffolds without the need for additional adhesives (Fig. 4 B and C and Movie S3).

Fig. 4.

Versatility of multiform constructs based on paper origami. (A) Schematic for the fabrication of patterned coculture platform in 3D. Hydrogel-containing HeLa cells labeled with CellTracker Blue were applied to the substrate, and a prepatterned mold consisting of four equally distributed square pillars (2-mm radius and 8-mm distance for each pillar) was placed on the sample. After gelation, the mold was removed, and the hole was filled with hydrogel-containing HeLa cells labeled with CellTracker Green. (Scale bar, 1,000 μm.) (B) CAD-based planar figure for precise paper origami and the folded structures in 3D coated with hydrogel dyed using water-soluble dyes. Adopting the lock-and-key method, paper origami was completed without additional adhesive. (C) Assembling paper-building block to fabricate multiform structures. (Scale bar, 2 cm.)

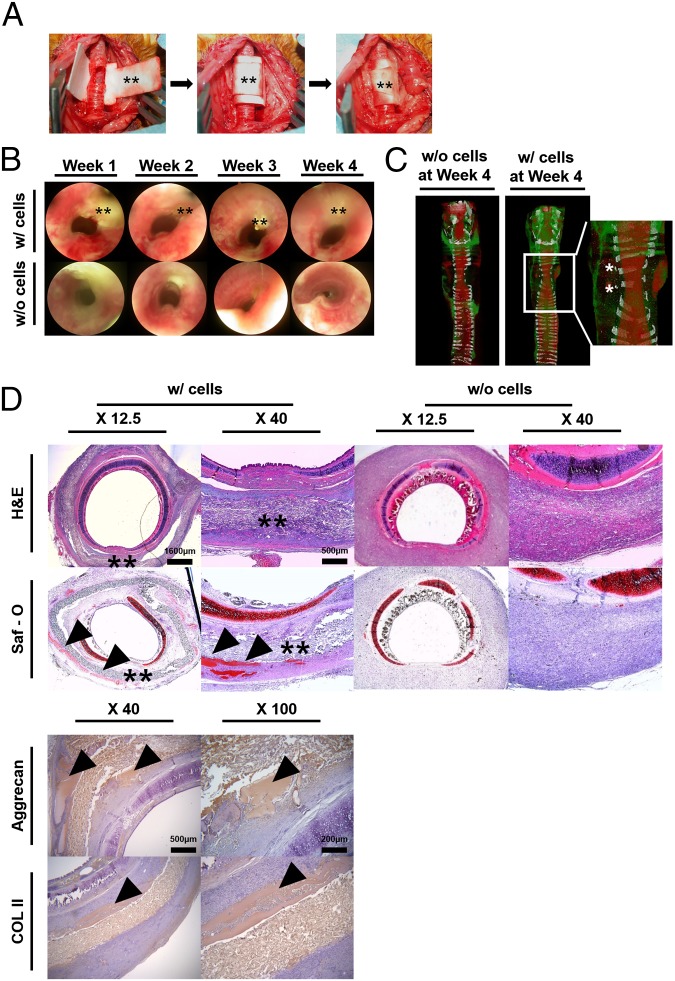

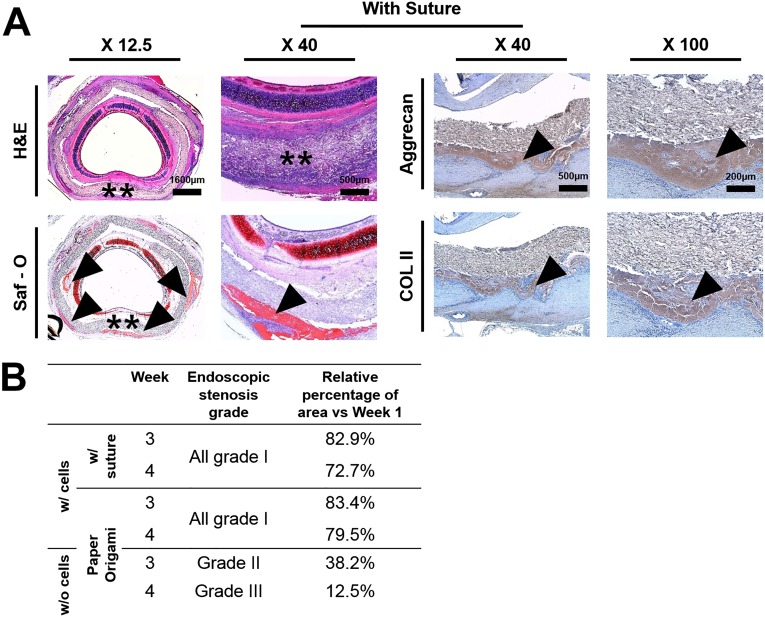

For further applications of the hydrogel-laden paper scaffold, we fabricated cylindrically shaped scaffolds via an origami-based lock-and-key mechanism and applied for tracheal reconstruction. A cylindrically shaped scaffold (2-cm length and 8-mm diameter) was coated with alginate hydrogel with or without rabbit articular chondrocytes (4 × 107 cells/mL). A three-ring, 120° tracheal ring was removed, and the tracheal defect was sealed with hydrogel-laden paper scaffold and firmly secured in place via a lock-and-key method (Fig. 5A). In trachea engineering, a tight fixation of the tracheal tube is a key point in preventing air leakage, which can cause emphysema and inflammation in the surrounding soft tissue due to the bacteria inhaled with air (26). Although forming a cylindrical shape appears to be a trivial origami-based method, we have used this simple origami structure and applied to complete the tracheal tube structures in an animal model. Moreover, wrapping and folding steps were used to seal the defect area tightly without the use of sutures. This paper scaffold provided air tightness and adequate strength to prevent airway collapse. Paper origami with a simple lock-and-key method was a facile process and did not require significant surgical time. In comparison, we additionally performed the trachea model using paper-based scaffold wrapping with the use of sutures (Fig. S10A). Similar to the lock-and-key method, the suture around the paper-based scaffolds was applied to prevent the air leakage and keep it in place. Accordingly, the sutured sample resulted in trachea tissue regeneration and showed no tissue granulation at week 4 (i.e., similar to lock-and-key samples).

Fig. 5.

Functionally defined paper scaffold transplantation for tracheal reconstruction. (A) Procedure for tracheal reconstruction using the cylindrically shaped scaffold using lock and key. After a three-ring, 120° trachea wall defect was made on the tracheal ring (i), the sample was used to cover the defect (ii), and the key was inserted into the lock (iii). (B) Endoscopic images at 1, 2, 3, and 4 wks. Double asterisk (**) indicates the paper scaffold. (C) Computed tomographic (CT) images at 4 wks. Asterisks show signs of regenerated chondrocytes. No obvious stenosis was observed on the CT images. White, red, and green colors indicate the cartilage, airway, and muscles, respectively. (D) Histologic evaluation of cross-sections of specimens taken after implantation. All samples were collected at 4 wks and analyzed by hematoxylin-eosin, Safranin-O, Aggrecan, and collagen type II. Double asterisks (**) and arrowheads indicate the paper scaffold and immature chondrogenesis, respectively. (Scale bar, X 12.5: 1,600 µm; X 40: 500 µm.)

Fig. S10.

(A) Table of endoscopic stenosis grade. (B) Histological evaluation of tracheal reconstruction with suture. (Scale bar, X 12.5: 1,600 µm; X 40: 500 µm.)

All animals survived without respiratory distress until the scheduled time for euthanasia. On endoscopic examination, none of the animals showed an ingrowth of granulation tissue on the inner surface of the grafts, and there was no evidence of infection or distal accumulation of secretions in the cell-loading samples (Fig. 5B). However, acellular samples showed a narrowing of the internal lumen (Fig. 5B). In cellular samples, the respiratory mucosal layer did not cover the prosthesis completely, but the airway lumen was well maintained (Fig. 5B). Airway stenosis was minimal in the cellular samples, and the endoscopic airway stenosis grading is summarized in Fig. S10B. At autopsy, the reconstructed tracheal surface in the animals was clear and smooth without profuse inflammatory reactions between the tracheal and pretracheal tissue in the cell-loading samples. These samples were also completely attached to the normal trachea without any granulation or dislocation of the membranes (Fig. 5B). Computed tomography (CT) images revealed a luminal contour at the regenerated site, even though the tracheal cartilage ring was not fully regenerated in the cellular samples (Fig. 5C). Signs of regenerated cartilage from the implanted chondrocytes were detected at the edge of the defected cartilage ring. In histologic evaluation, all samples were integrated into the surrounding soft tissue (Fig. 5D). Multiple spots of immature chondrogenesis were found at the edge of the membrane at week 2 in the cell-laden samples, and immature chondrogenesis was up-regulated at week 4 as more chondrogenic spots appeared. All acellular samples showed no tissue granulation at week 4 in histologic evaluation (Fig. 5D). The cell-laden scaffolds regenerated the tracheal defect perfectly without granulation tissue ingrowth or graft failure.

Conclusion

This work describes a strategy for the formation of hydrogel-laden multiform structures starting with paper scaffolds and suggests a new route for trachea tissue engineering. It combines concepts adapted from origami coupled with a vapor-based functional thin-film–coating process, the iCVD process, for preserving the morphology of paper microstructure and keeping the paper robust under wet conditions. This work also identifies a solution in the field of multiform scaffold fabrication: the CAD-based lock-and-key design of planar sheets that can be folded into multiform structures with spatial arrangements of tissue elements. Additionally, a structured paper scaffold was able to deliver the encapsulated chondrocytes to enhance tissue regeneration in vivo. In summary, an origami-based tissue-engineering approach was successfully applied in the trachea regeneration model.

Materials and Methods

Fabrication of Chemically Modified Substrates.

Chemically modified paper was prepared from filter paper (Whatman; Grade 3, GE Healthcare Life Science) commonly available in the laboratory. The filter paper was used as received, with no pretreatment or cleaning process before the application of the iCVD process. The PSMa polymer film was deposited in an iCVD vacuum reactor chamber (Daeki Hi-Tech). Maleic anhydride (Ma) (99%) and styrene (99%) were used as monomers. Tert-butyl peroxide (TBPO, 99%) was used as the initiator. All monomers and initiator were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any further purification. Ma was heated to 55 °C whereas styrene and TBPO were maintained at room temperature for addition into the chamber as vapor. The flow rate of Ma, styrene, and TBPO was 1.6, 6.0, and 1.2 standard cubic centimeter per minute (sccm), respectively. The filter paper was placed on the substrate, which was maintained at 25 °C, for adsorption of monomers. The iCVD chamber pressure was fixed at 600 mTorr. The filament temperature was maintained at 180 °C to initiate the free radical polymerization of PSMa. The deposition rate was monitored in situ with the He-Ne laser (JDS Uniphase). The calcium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, 96%) was solubilized in distilled water at a concentration of 0.25 M. The PLL solution [Sigma-Aldrich, 0.1% (wt/vol) in H2O] and calcium chloride solution were mixed in a 1:10 volumetric ratio. The PSMa-deposited filter paper was dip-coated in PLL and calcium chloride solution for 2 h.

Organ-Shaped 3D Hydrogel Structure Fabrication and Cell Encapsulation.

For precise design of the structure, a planar figure was created using a CAD program. Tubular, rectangular, parallel-piped, or star-shaped structures were readily constructed through the classic paper origami method. The structure was then soaked in alginate. After 30 min of gelation, the paper-based structure was coated with alginate hydrogel and washed three times with PBS (Gibco-BRL). For cell encapsulation, rabbit articular chondrocytes were trypsinized and resuspended in alginate hydrogel at a density of 1 ∼4 × 106 cells/mL depending on the experiment. Other steps for fabricating the 3D hydrogel structure encapsulated with cells were the same as for the method described above. The medium was changed every 2 d.

Sustained Release of Calcium Ion from Paper-Based iCVD Substrate.

The release profile for calcium ion from the paper-based iCVD substrate was measured using Pointe Scientific Calcium Liquid Reagents (Pointe Scientific). The paper-based iCVD substrate (1 × 1 cm) was soaked in distilled water at room temperature. ddH2O purified for the desired time points (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min) were collected and quantified using Infinite 200 PRO TECAN Ltd. Relative absorbance intensity values were converted into the actual concentration of calcium ion by correlation with a standard curve.

Hydrogel Thickness Depending on Time and Hydrogel Concentration.

The paper-based iCVD substrate (1 × 1 cm) was soaked in 1, 1.5, and 3% (wt/vol) sodium alginate (FMC biopolymer), respectively. Samples at the desired time points (10, 20, 30, and 60 min) were collected and imaged using AM413MT Dino-Lite X (Dino-Lite). The hydrogel thickness was analyzed as three random points were chosen, and the average was calculated by DinoCapture 2.0 (Dino-Lite).

Cell-Laden–Based Paper Scaffold for Tracheal Implantation and Surgical Procedures.

All protocols (no. 14–0199-S1A0) were performed in accord with the guidelines of the Animal Care Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Hospital. New Zealand White rabbits (Koatech Laboratory Animal Company) weighing 2.6 to ∼3.0 kg were placed under anesthesia with an intramuscular injection of zoletile (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (4.5 mg/kg). Surgery was performed as follows. The animal was placed in a supine position. The relevant area was shaved and disinfected. A vertical incision was made at the midline of the neck. The strap muscles were separated at the midline until the tracheal cartilages were encountered. A three-ring, 120° anterior tracheal wall defect was then made in the tracheal rings, and the paper-based tubular structure was placed in the trachea. The paper-based tubular structure (4-mm radius and 2-cm height) was coated with 1% (wt/vol) alginate hydrogel containing P1 rabbit chondrocytes (cell density, 2.8 × 107 cells/mL). This tracheal defect size has been shown to result in severe tracheal stenosis and subsequent death in rabbits. The tracheal defect was covered by wrapping the paper around the trachea and inserting the key into the lock to finish the implantation. The skin incision was closed using 4–0 nylon (Johnson & Johnson). Postoperatively, the animals were observed for 2 h before being returned to their cages where water and standard feed were available. For the following 4 d, the rabbits were given 20 mg/kg kanamycin as prophylaxis. Clinical signs were monitored daily with special attention to weight, cough, sputum production, wheezing, and dyspnea.

Immunohistochemical Staining with Aggrecan and Collagen Type II.

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and dehydrated with a graded ethanol series. The fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, and the paraffin sections were stained with aggrecan and collagen type II. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4-µm-thick serial sections mounted on poly-l-lysine–coated slides. The sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval using pressure cooking in 1× citrate buffer (pH 6.0) (Invitrogen) for 10 min followed by slow cooling for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with monoclonal anti-aggrecan antibody (1:500 dilution; Novus Biological) and monoclonal anti-collagen type II antibody (1:500 dilution; Novus Biological) for 1 h and developed using the Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector) and Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma) as a counterstain.

SI Materials and Methods

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Analysis.

XPS (K-alpha, Thermo VG Scientific) was used to analyze the chemical composition of the paper scaffolds. An Kα X-ray radiation source [200 W, 12 kV, kinetic energy (KE) = 1,486.6 eV] was used to record the spectra under an ultra-high vacuum (10−10 Torr). XPS spectra were recorded in the 0- to 1,100-eV range with a resolution of 1.0 eV and a pass energy of 50 eV. The atomic ratios of the surfaces were calculated using each area of peaks for C1s, O1s, and N1s in the survey scans multiplied by the atomic sensitivity factors. XPS high-resolution scans of each atom were performed using the Avantage data system (Thermo VG Scientific).

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Scanning electron microscopy and energy disperse spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) (Magellan 400, FEI Company) was used to analyze the surface morphology and surface chemical composition of the paper scaffolds.

Tensile Strength and Young’s Modulus Analysis.

The mechanical strength of the paper scaffolds under dry and wet conditions was analyzed by measuring the tensile strength and Young’s Modulus at room temperature using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM) (INSTRON 5583, Instron). The crosshead speed was 3 mm/min with a sample size of 10-mm width and 40 mm between the jaws.

Water Contact Angle Analysis.

Water contact angles were measured with a contact angle meter (Phoenix 150, SEO, Suwon), using an 8-μL deionized water droplet at room temperature to evaluate the hydrophilicity on the surface of the paper samples.

Mechanical Test of Hydrogel and Paper: Adhesion Strength and Elastic Modulus.

Adhesion strength was quantitatively measured by a laboratory shear test using a Universal Tensile Machine (INSTRON 5965, 1-kN load cell, INSTRON). Adhesion joints were fabricated as a single lap mode (Fig. S7) with total length and gauge length of 125 and 70 mm, respectively. Measurements were conducted with a 5-mm/min loading velocity. Before the test, overflown gels were removed with a razor blade, and the humidity of the specimen and the gauge length were controlled under the same conditions to ensure an accurate test with optimized conditions. The Young’s Modulus of the alginate gel was analyzed by a compression test using a universal tensile machine (INSTRON 5965, 50-N load cell). The alginate gel layer was formed on the surface of solid glass and used as a flat punch for the test. Each specimen used in this experiment was fabricated as a disk (Ø15 mm, thickness < 1 mm).

Computer Simulation of Sustained Release of Calcium Ions.

We hypothesized that the increased alginate concentration would result in rapid consumption of the Ca2+ ions by cross-linking reactions near the surface of the paper scaffold, resulting in a thinner hydrogel layer. To examine this hypothesis, we modeled the concentration profile of calcium ions through the alginate hydrogel structure by COMSOL Multiphysics (COMSOL).

Fabrication of the Coculture Platform.

Hydrogel with cells fluorescently labeled with CellTracker Blue (Life Technologies) was applied to the paper substrate and covered with a 3D printed mold. After 30 min of gelation, the mold was removed and the residue was washed three times using PBS (Gibco-BRL). Void chambers were then filled with hydrogel-containing HELA cells fluorescently labeled with CellTracker Green (Life Technologies).

Cell Viability Test.

The sample was stained with live/dead assay reagents (Invitrogen) to quantify cell viability within hydrogels according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Biochemical Analysis.

Samples were collected and DNA content was quantified using a Quanti-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen). The GAG content was quantified using dimethylmethylene blue spectrophotometric assay at A525, as previously described (27). Total collagen content was determined by measuring the amount of hydroxyproline within the constructs after acid hydrolysis and reaction with p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde and chloramine-T.

In Vivo Subcutaneous Transplantation.

For in vivo analysis, female BALB/c-nude mice at 4 wks of age (16–20 g of body weight, OrientBio, Gyeonggi province, Republic of Korea) were anesthetized and samples were implanted into s.c. tissue.

Histological Analysis.

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and placed in 20% (wt/vol) sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS overnight at 4 °C. Samples were then incubated with an infiltration solution [1:1 of optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (CellPath) and 20% (wt/vol) sucrose in PBS] overnight at room temperature. After transferring the sample to a cryomold, the cryomold was filled with OCT compound and frozen with isopentane in a container filled with liquid nitrogen. Cryosectioning was performed on the frozen blocks using a cryostat (Leica CM 1500; Leica Microsystems). Five-micrometer histologic sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Safranin-O.

Endoscopic Airway Examination.

Animals in each group were scheduled to be euthanized at 2 and 4 wks after operation to evaluate the reconstructed tracheas. Immediately after euthanization, bronchoscopy was performed with a 4-mm, 30° rigid endoscope (Richards). Images were taken for each animal’s airway with a digital camera (E4500, Nikon, Japan) attached to the rigid endoscope. Airways were graded for the maximal degree of stenosis: grade I, 0–33% stenosis; grade II, 33–66% stenosis; and grade III, 66–100% stenosis. The reconstructed airway segments were then harvested for histologic examination.

Radiologic Assessment.

A micro-CT scanner (NFR Polaris-G90, Nanofocusray) and a human CT scanner (Sensation 64, Siemens) were used to determine tracheal cartilage regeneration and tracheal airway narrowing, respectively. Three-dimensional images of rabbit trachea were obtained and reconstructed using software programs (Lucion, Infinitt Healthcare, for cartilage evaluation, and Inspace, Siemens, for airway evaluation, respectively).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean SD. Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (Student’s t test) with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (Grants HI13C1789010014, HI13C0451020013, and HI14C15410100); by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Grant NRF-2012M3A9C6050102); and by the Advanced Biomass R&D Center of the Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Science, Information & Communication Technology (ICT), and Future Planning (ABC-2011-0031350).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1504745112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: Building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(11):887–901. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens MM, George JH. Exploring and engineering the cell surface interface. Science. 2005;310(5751):1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Designing materials for biology and medicine. Nature. 2004;428(6982):487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khademhosseini A, Langer R, Borenstein J, Vacanti JP. Microscale technologies for tissue engineering and biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(8):2480–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507681102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinke M, et al. An engineered 3D human airway mucosa model based on an SIS scaffold. Biomaterials. 2014;35(26):7355–7362. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, et al. Phage nanofibers induce vascularized osteogenesis in 3D printed bone scaffolds. Adv Mater. 2014;26(29):4961–4966. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakab K, Neagu A, Mironov V, Markwald RR, Forgacs G. Engineering biological structures of prescribed shape using self-assembling multicellular systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(9):2864–2869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400164101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang JH, Castano O, Kim HW. Electrospun materials as potential platforms for bone tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(12):1065–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross BC, Erkal JL, Lockwood SY, Chen C, Spence DM. Evaluation of 3D printing and its potential impact on biotechnology and the chemical sciences. Anal Chem. 2014;86(7):3240–3253. doi: 10.1021/ac403397r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy SV, Atala A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):773–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schubert C, van Langeveld MC, Donoso LA. Innovations in 3D printing: A 3D overview from optics to organs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(2):159–161. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derda R, et al. Paper-supported 3D cell culture for tissue-based bioassays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18457–18462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910666106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deiss F, et al. Platform for high-throughput testing of the effect of soluble compounds on 3D cell cultures. Anal Chem. 2013;85(17):8085–8094. doi: 10.1021/ac400161j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez AW, Phillips ST, Whitesides GM, Carrilho E. Diagnostics for the developing world: Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. Anal Chem. 2010;82(1):3–10. doi: 10.1021/ac9013989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HJ, et al. Paper-based bioactive scaffolds for stem cell-mediated bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2014;35(37):9811–9823. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaydin-Ince G, Dubach JM, Gleason KK, Clark HA. Microworm optode sensors limit particle diffusion to enable in vivo measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(7):2656–2661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015544108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MJ, et al. BMP-2 peptide-functionalized nanopatterned substrates for enhanced osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(30):7236–7246. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang BJ, et al. Umbilical-cord-blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells seeded onto fibronectin-immobilized polycaprolactone nanofiber improve cardiac function. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(7):3007–3017. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenhaeff WE, Gleason KK. Initiated chemical vapor deposition of alternating copolymers of styrene and maleic anhydride. Langmuir. 2007;23(12):6624–6630. doi: 10.1021/la070086a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandes TG, et al. Three-dimensional cell culture microarray for high-throughput studies of stem cell fate. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106(1):106–118. doi: 10.1002/bit.22661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MY, et al. Three-dimensional cellular microarray for high-throughput toxicology assays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(1):59–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708756105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsunaga YT, Morimoto Y, Takeuchi S. Molding cell beads for rapid construction of macroscopic 3D tissue architecture. Adv Mater. 2011;23(12):H90–H94. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napolitano AP, et al. Scaffold-free three-dimensional cell culture utilizing micromolded nonadhesive hydrogels. Biotechniques. 2007;43(4):494, 496–500. doi: 10.2144/000112591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosadegh B, et al. Three-dimensional paper-based model for cardiac ischemia. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(7):1036–1043. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon SK, et al. Tracheal reconstruction with asymmetrically porous polycaprolactone/pluronic F127 membranes. Head Neck. 2014;36(5):643–651. doi: 10.1002/hed.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.