Significance

Osteoporosis is a major health problem worldwide, as the aging population is soaring. However, molecules involved in the regulation of bone remodeling are still incompletely understood. Nck (noncatalytic region of tyrosine kinase) is an adaptor molecule linking cytoskeleton and cell motility. We now identify that Nck regulates cell migration in vitro as well as in vivo and regulates bone mass via bone formation activity. Nck positively regulates repair of bone injury. This discovery provides a unique insight into the understanding of bone remodeling.

Keywords: Nck, osteoblast, migration, bone remodeling, bone repair

Abstract

Migration of the cells in osteoblastic lineage, including preosteoblasts and osteoblasts, has been postulated to influence bone formation. However, the molecular bases that link preosteoblastic/osteoblastic cell migration and bone formation are incompletely understood. Nck (noncatalytic region of tyrosine kinase; collectively referred to Nck1 and Nck2) is a member of the signaling adaptors that regulate cell migration and cytoskeletal structures, but its function in cells in the osteoblastic lineage is not known. Therefore, we examined the role of Nck in migration of these cells. Nck is expressed in preosteoblasts/osteoblasts, and its knockdown suppresses migration as well as cell spreading and attachment to substrates. In contrast, Nck1 overexpression enhances spreading and increases migration and attachment. As for signaling, Nck double knockdown suppresses migration toward IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1). In these cells, Nck1 binds to IRS-1 (insulin receptor substrate 1) based on immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-Nck and anti–IRS-1 antibodies. In vivo, Nck knockdown suppresses enlargement of the pellet of DiI-labeled preosteoblasts/osteoblasts placed in the calvarial defects. Genetic experiments indicate that conditional double deletion of both Nck1 and Nck2 specifically in osteoblasts causes osteopenia. In these mice, Nck double deficiency suppresses the levels of bone-formation parameters such as bone formation rate in vivo. Interestingly, bone-resorption parameters are not affected. Finally, Nck deficiency suppresses repair of bone injury after bone marrow ablation. These results reveal that Nck regulates preosteoblastic/osteoblastic migration and bone mass.

Bone is a metabolically dynamic tissue, as it is continuously remodeled based on repetition of bone resorption and bone formation (1). Under normal conditions, bone formation and bone resorption are coupled and balanced by the activities of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, respectively (2). Bone remodeling occurs first by osteoclastic bone resorption. Then, preosteoblasts or their precursors migrate into the resorption cavities and attach to the bottom of the cavities, followed by osteoblastic bone formation to start to fill the bone cavity through producing bone matrix (3). Therefore, preosteoblastic migration and attachment during bone remodeling are critical events to maintain bone mass (4–6). Regarding cell migration, most of the important motility and migration in remodeling is undergone by precursors of osteoblasts that are shown to be recruited by TGF-beta1, and these cells differentiate under the control of IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) at the sites of remodeling (7, 8). Migration and attachment of the cells in the lineage of osteoblastic cells are also important in the case of repair after bone injury, as these cells migrate into the bone injury site and start to proliferate and to produce bone. These cellular events are considered to be critical in understanding the pathological state in bone, such as osteoporosis. However, the molecular bases of preosteoblastic/osteoblastic migration with respect to cytoskeletal regulation and its relevance to bone mass determination are still incompletely understood.

The key steps in the migration and attachment of the cells include extension of the cell membrane, remodeling of actin cytoskeleton, formation of adhesion complex, and organization of stress fibers. Remodeling of actin cytoskeleton is a process of dynamic assembly and disassembly of filamentous actin. Such reorganization of actin cytoskeleton governs essential aspects of cell motility and attachment that are required for the formation of cellular structures such as lamellipodia, filopodia, stress fibers, and focal adhesions (9, 10). Preosteoblasts and osteoblasts are known to be capable of migrating toward chemo-attractants such as anabolic cytokines (7, 8). However, the key molecules involved in control of cytoskeleton that regulates osteoblastic cell migration and their relevance to bone mass regulation have yet to be elucidated.

Nck (noncatalytic region of tyrosine kinase) adaptor proteins are cytosolic effectors that regulate remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton (11, 12). Mammals carry two closely related Nck genes, Nck1 and Nck2 (collectively termed Nck), that contain three N-terminal Src homology 3 (SH3) domains and a single C-terminal SH2 domain. Although actin cytoskeleton plays a critical role in cells and Nck is one of the possible factors affecting polymeric actin dynamics, the function of Nck in osteoblastic cells and in regulation of bone mass is incompletely understood. Therefore, we examined the role of Nck in the migration of bone cells and its relevance to the regulation of bone mass.

Results

Nck1 and Nck2 Are Expressed in Preosteoblasts and Osteoblasts.

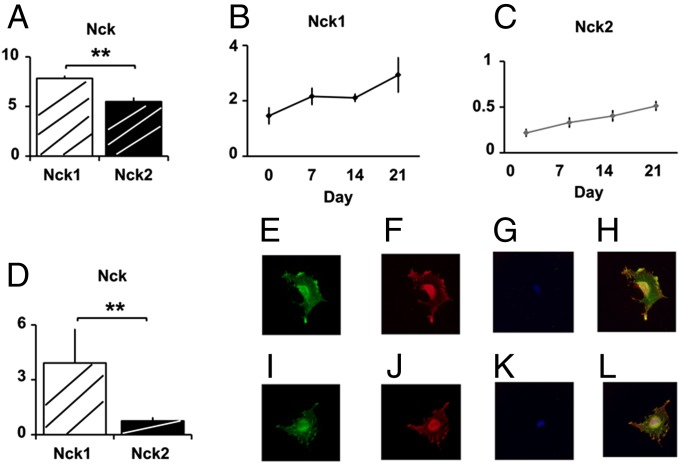

First, we examined the levels of Nck1 and Nck2 expression in preosteoblasts/osteoblasts. Nck1 and Nck2 mRNAs were expressed in the primary cultures of osteoblasts (Fig. 1A). In cultured osteoblasts, Nck1 levels were higher than those of Nck2. Primary osteoblasts cultured in differentiation medium (β glycerophosphate and ascorbate) showed an increase in Nck1 and Nck2 expression as a function of time during the differentiation of osteoblasts in these cultures (Fig. 1 B and C). There was a parallel increase or a trend in increase regarding the expression levels of alkaline phosphatase, bone sialoprotein, PTH receptor, and osteocalcin (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Nck1 and Nck2 mRNAs were also expressed in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 1D). Expression of Nck1 and Nck2 proteins was examined using antibodies. In preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells, polymerized actin was detected by using phalloidin-fluorescein (Fig. 1E), and immnocytochemistry using anti-Nck1 antibody (Fig. 1F) revealed the expression of Nck1 protein. Using DAPI, the nuclei of the cells were stained (Fig. 1G), and a merged image indicated the partial overlap between actin and Nck1 (Fig. 1H). Colocalization was observed as yellow signals in the periphery, cytoplasm, and nuclei of the cells. Similarly, in the other set of cells showing polymerized actin (Fig. 1I), anti-Nck2 antibody detected the expression of Nck2 protein (Fig. 1 J and K, DAPI), and a merged image indicated partial overlap between actin and Nck2 (Fig. 1L). Thus, Nck mRNA and proteins are expressed in these cells.

Fig. 1.

Nck1 and Nck2 are expressed in preosteoblasts and osteoblasts. (A) Nck1 and Nck2 mRNA in primary cultures of osteoblasts. (B) Nck1 and (C) Nck2 expression during differentiation. (D) Nck1 and Nck2 expression in MC3T3-E1. Data were normalized against GAPDH mRNA levels. Experiments were repeated more than twice with similar data. Phalloidin staining in MC3T3-E1 cells (green, E and I), Nck1 and Nck2 (red, F and J), DAPI (blue, G and K), and merged (H and L). **P < 0.01.

Nck Knockdown in Preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells Suppresses Migration.

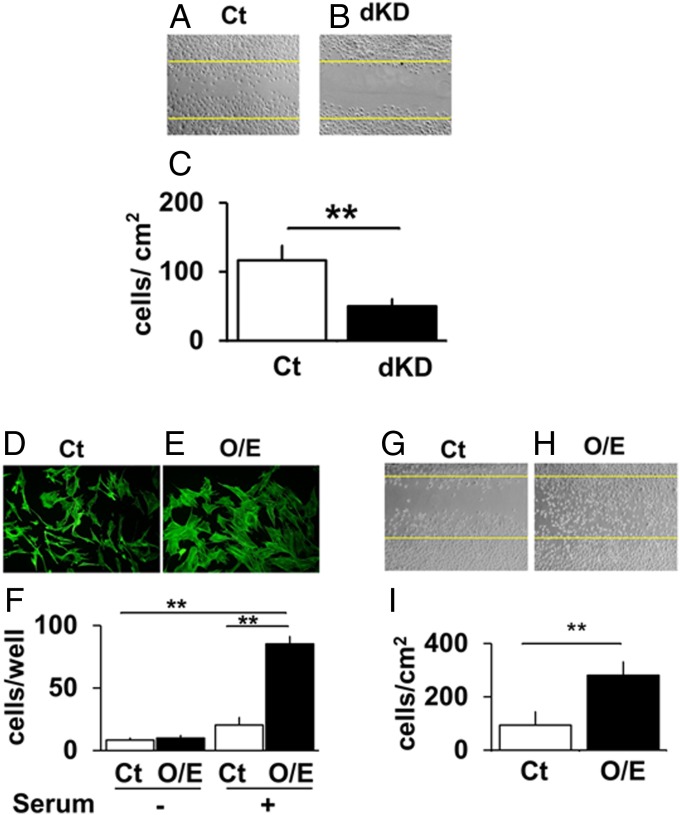

Nck has been reported to play a role in controlling cell motility. To elucidate whether the Nck knockdown in bone cells is associated with alteration in their migration, migration activity was examined using scratch wound assay (Fig. 2A). As Nck1 and Nck2 single knockout mice did not reveal deficiency (12, 13), double knockdown (dKD) of both Nck1 and Nck2 was conducted. By using siRNA, Nck1 and Nck2 mRNA levels were knocked down by 65% and 70%, respectively (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). Nck knockdown in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells (dKD using siRNAs for Nck1 and Nck2) suppressed the appearance of migrating cells in the wound area in monolayer culture (Fig. 2B). Quantification indicated that the Nck knockdown suppressed cell migration by over 50% (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that Nck1 and Nck2 play a role in the migration of preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1cells.

Fig. 2.

Nck knockdown and overexpression in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells suppresses and enhances migration, respectively. Scratch wound healing assay for Ct si (A) and Nck.dKD si (B). (C) Quantification. **P < 0.01. Phallodin staining in Ct (pcDNA) (D) and Nck1 O/E (E). (F) Transwell migration assay for Ct cells and Nck1 O/E. (Scale bar, 200 µm.) Scratch wound healing assay for control (G) and Nck1 O/E (H). (I) Quantification. **P < 0.01.

Nck1 Overexpression in Preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells Enhances Migration.

As Nck knockdown in preosteoblasts reduces migration ability, we further examined the reverse side of the phenomenon by overexpression of Nck. To overexpress Nck in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells, the cells were transfected with flag-tagged cDNA encoding the full-length Nck1 sequence cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector containing a neo-expression system in the same plasmid. We chose to overexpress Nck1, as it was suggested that Nck1 and Nck2 are redundant based on individual knockout mouse studies (12), and Nck1 expression levels were higher than Nck2 in the preosteoblastic cells. After 48 h of transfection, Nck1-overexpressing cells were trypsinized and plated into a 35-mm culture dish and treated with G-418 solution (Roche) for a few weeks until the colonies of Nck1-overexpressing cells were visible. For control, pcDNA1 (empty vector) was used. These cells were then used for subsequent analysis. By overexpression, Nck1 levels increased about threefold (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Nck1 overexpression enhanced spreading of the cells and increased the actin fibers [Fig. 2 D, control, and E, Nck1 O/E (overexpression)]. These cells were also used for transwell migration assay. Nck1-overexpressing cells were plated in the upper compartments of the transwell, and serum was added to the lower compartments. The cells were incubated for 24 h and then fixed. The data revealed that Nck1 overexpression in preosteoblasts increased migration toward the serum, compared with the control cells transfected with an empty pcDNA1 vector (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, Nck1 overexpression enhanced the levels of Nck2 mRNA expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), and Nck2 knockdown by siRNA reduced the effects of Nck1 overexpression on cell migration in a transwell assay and a scratch wound healing assay (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7, respectively). These data reveal that Nck1 overexpression in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1cells increases their migration activity.

Nck Overexpression in Preosteoblastic Cells Increases Cell Motility and Repair in a Scratch Wound Healing Assay.

As a transwell assay is dependent on cellular migration activity to move vertically through the micropores of membranes toward serum, we further conducted a scratch wound healing assay that evaluates horizontal migration of the preosteoblasts. We conducted a scratch wound healing assay in a monolayer culture by using Nck1-overexpressing MC3T3-E1 cells and control cells. The cells were plated at 104 cells per well in six-well plates and were allowed to grow until they were confluent. After the cells reached confluence, they were made quiescent (by reducing serum concentration down to 0.5% FBS) for 24 h, and then the wound was made (Fig. 2 G and H) by using the 200 μL pipette tip. The cells moving into the wound were examined after 48 h. Nck1 overexpression enhanced preosteoblastic migration into the wound area (Fig. 2H), compared with the control (Fig. 2G). Quantification of the cells that migrated into the wound area revealed about threefold enhancement by Nck1 overexpression (Fig. 2I), indicating that Nck1 enhances the horizontal motility of preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells in this wound healing assay. Nck1 overexpression similarly enhanced cell migration in other independent Nck1-overexpressing clones, indicating that these observations are not limited to a single overexpressing clone (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Thus, not only the transwell but also the wound healing assay reveals that Nck1 promotes migration of preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells.

Nck Double Deficiency Suppresses Preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cell Migration Toward IGF1.

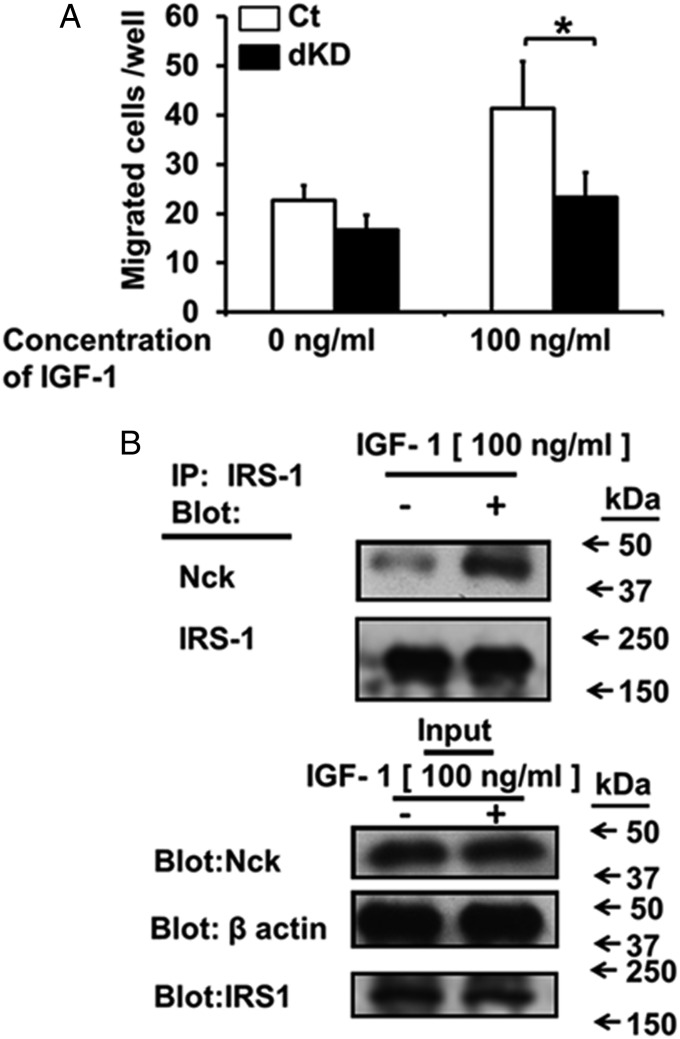

We next examined the target of the Nck-dependent migration. As a candidate molecule, we focused on IGF1 as one of the abundant growth factors present in bone matrix (11). To examine the requirement of the Nck adapter proteins for IGF1-induced migration, we used the transwell migration assay. Control siRNA-transfected MC3T3-E1 cells (Ct si) and Nck siRNA-transfected MC3T3-E1 cells (siNck1 and siNck2 dKD) were seeded in the upper chamber in the transwells, and 100 ng/mL IGF1 was placed in the lower chamber. The number of cells that migrated from the upper to the lower part of the transwells after 24 h was counted. In control (Ct si) cells, IGF1 enhanced the migration of the cells from the upper part of the transwells toward the lower chamber (Fig. 3A, open bar). Compared with the Ct si cells, dKD suppressed MC3T3-E1 cell migration to IGF1 (Fig. 3A, closed bar). As for individual Nck1 and Nck2, single knockdown of each of the Nck forms in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells did not significantly alter the levels of migration. In contrast, dKD of both Nck1 and Nck2 significantly suppressed the levels of migration (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). These observations indicate that the Nck adaptor is needed for the preosteoblastic migration directed toward IGF1.

Fig. 3.

Nck double deficiency suppresses preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cell migration toward IGF1. (A) Transwell migration assay for Ct siRNA (Ct) and Nck1 and Nck2 siRNA (dKD) toward IGF1. *P < 0.05. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) of IRS-1 and Nck proteins.

Nck Binds to Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 in Preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells.

To explore how Nck regulates IGF1-induced migration of MC3T3-E1 cells, we examined the binding of Nck to IRS-1 (insulin receptor substrate 1), a downstream molecule involved in IGF1 action. IGF1-stimulated or -unstimulated MC3T3-E1 cells were subjected to a coimmunoprecipitation assay. Quiescent MC3T3-E1 cells were incubated with or without IGF-I (100 ng/mL) for 10 min. After the cells were lysed in lysis buffer, equal amounts of protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation assay using anti–IRS-1 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS/PAGE. We analyzed the bound proteins based on Western blotting using antibodies against Nck and IRS-1 (Fig. 3B). The anti-Nck antibody used for this Western blotting recognizes both Nck1 and Nck2. We found that Nck binds to IRS-1 at baseline. IGF1 treatment enhanced this binding of Nck to IRS-1 (Fig. 3B). Antibody specificity for IRS-1 or Nck was verified by using a control antibody (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). These data indicate that IGF1 stimulates preosteoblastic migration via Nck and IGF1 receptor activation and that IGF1 enhances binding between IRS-1 and Nck.

Nck Deficiency Suppresses in Vivo Cell Migration in Calvarial Bone.

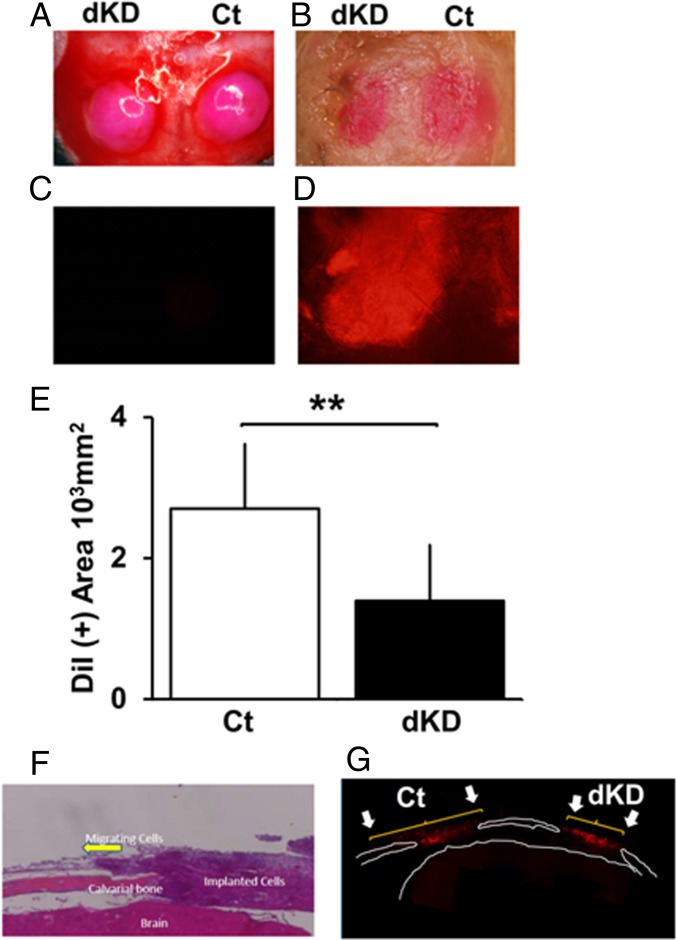

Although Nck knockdown suppresses preosteoblastic migration in vitro, it is still not clear whether such knockdown in MC3T3-E1 cells may affect their migration in vivo. To further examine the function of Nck with respect to preosteoblastic migration, the effects of Nck knockdown on cell migration in vivo were examined by implanting cells in mouse calvaria. Calvarial bone defects were made by using a dental drill with a diameter of 3.5 mm. A round-shaped defect was made in the center of the right and left parietal bones of wild-type mice. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with either Ct si or siNck1 and siNck2 for dKD by siRNAs (Nck.dKD si). Then, the cells were labeled with DiI for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were scraped and lightly centrifuged to form a cell pellet, and then the pellets were cultured for 2 d at the bottom of a conical centrifuge tube. Subsequently, the cell pellet was placed in the calvarial defect (Fig. 4A). As the pellet softened, the DiI-labeled cells were just filling the inner edge of the calvarial defect, but they did not flow out over the defect rim. After 1 wk, the calvariae were examined for the extent of expansion in the area of DiI-labeled red cells (Fig. 4B). When unstained cells were implanted, no red color was observed (Fig. 4C). When DiI-stained cells were placed in the calvarial defects, the red color was observed within the calvarial defect under fluorescent light (Fig. 4D). Thus, the red color tissue observed under normal light indicates the cells stained with DiI. In contrast to Ct si cells, the red area of Nck dKD cells in the calvarial defect was smaller (Fig. 4B, left side). Quantification of the red tissue area at the calvarial defect indicated that there was a suppression by Nck dKD compared with Ct si (Fig. 4E). Histological examination showed that the cells implanted in the calvarial defect went out from the edge of the defect, and some of these cells were observed along with the intact calvarial bone (Fig. 4F). A fluorescent picture indicates that DiI-labeled cells migrated out of the implanted site of calvarial defect and Nck dKD suppressed the extent of migration (Fig. 4G and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Thus, Nck dKD suppresses migration of MC3T3-E1 cells not only under the condition of in vitro culture settings but also within in vivo environments.

Fig. 4.

Nck deficiency suppresses in vivo cell migration in calvarial bone. (A) Immediately after implantation of the calvaria defects with Nck1 and Nck2 siRNA knockdown MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cell pellets. (B) One week after implantation, DiI-labeled Nck.dKD si tissue (left defect) and Ct si tissue (right defect). (C) Fluorescence microscopy of the calvaria defect covered with unstained cells and (D) DiI-labeled cells. (E) Quantification of the area covered by DiI-labeled cells. **P < 0.01. (F) Histological section of the implanted cells in the calvarial defects stained by H&E. Arrow indicates the cells migrating out from the implanted pellet placed in the calvarial defect. (G) Fluorescent image of the histological section revealing that DiI-labeled cells are migrating out from the calvarial defects. Arrows indicate the extent of migrating cells.

Nck1 and Nck2 Are Expressed in Bone.

To examine the expression of Nck in bone in vivo, we chose to observe the levels of Nck1 and Nck2 mRNAs in bone. Nck1 and Nck2 mRNAs were expressed in the calvarial bone, femur, and cortex in vivo (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A, Nck2 and B, Nck1). In bone, Nck1 levels were higher than those of Nck2. This was similar to the observation in the cultured osteoblasts. Thus, Nck mRNA is expressed in bone in vivo.

To address the role of Nck in bone in vivo, we used a genetic approach. Mice with single Nck1 deletion or those with single Nck2 deletion were reported to be similar to wild type (12), whereas double Nck1/Nck2-deficient mice were lethal (12). Therefore, we made use of the conditional double-deletion technique in mice, where double deficiency in Nck1 and Nck2 was established specifically in osteoblasts by using Cre-transgenic mice driven by an osteoblast-specific promoter. To create conditional double Nck1/Nck2-deficient mice, Cre-Nck1−/−,Nck2 fl/fl mice were mated with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of an osteoblast-specific 2.3-kb type I collagen promoter. Verification of the osteoblast-specific activity of the 2.3-kb type I collagen promoter was conducted by using ROSA26 mice. Mice with specific expression of Cre in osteoblasts showed expected expression patterns of LacZ specifically in bone, verifying the osteoblastic selectivity of the 2.3-kb collagen promoter (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 C, Cre- and D, Cre+). We then produced mice with Nck1 and Nck2 double deficiency specifically in osteoblasts (type I collagen Cre+,Nck1−/−,Nck2 fl/fl; from here on referred to as Nck-conditional dKD or Nck-cdKO). Analyses on the genomic DNA extracted from the bone of these mice showed expected loss of both Nck1 and Nck2 genes (Nck-cdKO; SI Appendix, Fig. S12E, Middle lane). These mice were born normally without exhibiting any significant abnormalities in gross skeletal patterning. Successful conditional double deletion of both Nck1 and Nck2 in the bone of Nck-cdKO mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A and B, cdKO-Bone) but not in extraskeletal tissue of the same mice, such as the spleen, was confirmed by PCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A and B, cdKO-Bone vs. cdKO-Spleen). Based on these analyses, conditional double deficiency of both Nck1 and Nck2 in osteoblasts was verified.

Nck Double Deficiency in Osteoblasts Suppresses Bone Mass Levels.

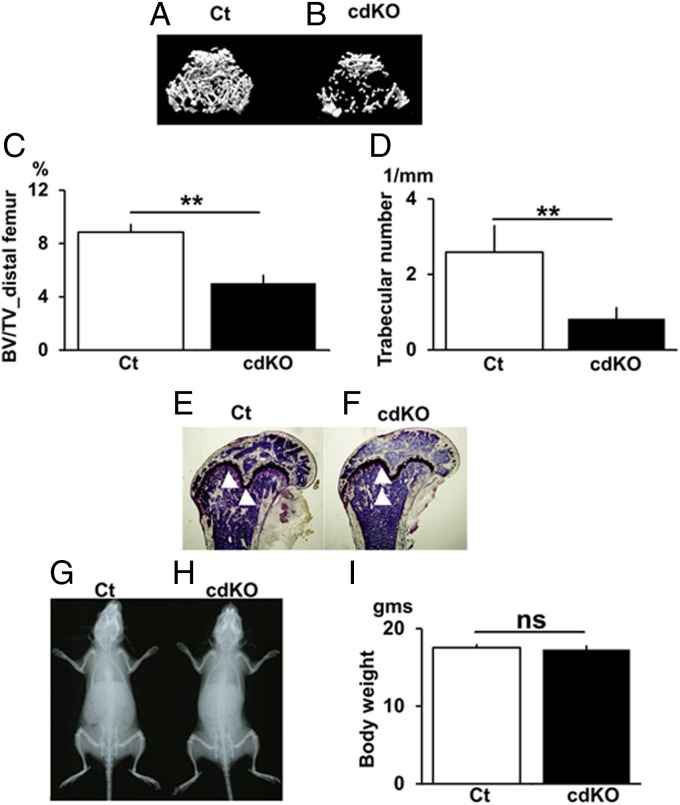

To examine the role of Nck in bone in vivo, 3D micro-CT analysis of bone in the distal femur was conducted. Control (2.3-kb type I collagen Cre–,Nck1+/+,Nck2 fl/fl) mice exhibited the presence of numerous trabecular bone (Fig. 5A, Ct). In contrast, conditional double Nck1/Nck2 deficiency in osteoblasts resulted in the disappearance of such numerous bone, and only scattered trabecular bone islands were observed (Fig. 5B, cdKO-OB). Even for the residual bone, connectivity was reduced and severe disruption of trabecular bone was observed (Fig. 5B). Quantification of the 3D-µCT–based structural parameters indicated that conditional Nck1/Nck2 double deficiency in osteoblasts (cdKO-OB) significantly decreased the trabecular bone mass (BV/TV) compared with wild type (Fig. 5C). Elemental analysis based on micro-CT indicated that Nck cdKO-OB reduced the trabecular number (Tb.N) and increased trabecular spacing (Tb.Spac) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) compared with control mice (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). These micro-CT analyses were conducted using female mice, and the analyses on male mice showed similar results (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). For other parameters, including trabecular thickness, cortical bone volume, cortical thickness, cortical internal line length, and cortical external line length, were similar between mutant and control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Histologically, Nck cdKO-OB induced reduction of trabecular bone islands within the bone marrow compared with control mice (Fig. 5 E and F, bone, white arrowheads; marrow cells, blue). Interestingly, the gross whole body proportion (Fig. 5 G and H) and body weight were similar between Nck cdKO-OB mice and the control (Fig. 5I), suggesting that Nck deficiency does not suppress overall growth of the skeleton, but it specifically suppresses trabecular bone mass. These observations indicate that osteoblast-specific Nck double deficiency causes a reduction in bone mass and deterioration in the structural elements in bone in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Conditional Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts suppresses bone mass levels. The 3D µCT images of the distal metaphyses of the femora of Ct (A) and cdKO-OB mice (B). (C) BV/TV. (D) Tb.N. (E) Villanueva stain Ct. (F) cdKO-OB. X-ray pictures for Ct (G) and cdKO-OB (H) mice and body weight (I). Age, 10 wk old. n = 9. **P < 0.01. ns, not significant.

Conditional Nck Double Deficiency in Osteoblasts Suppresses Bone Formation.

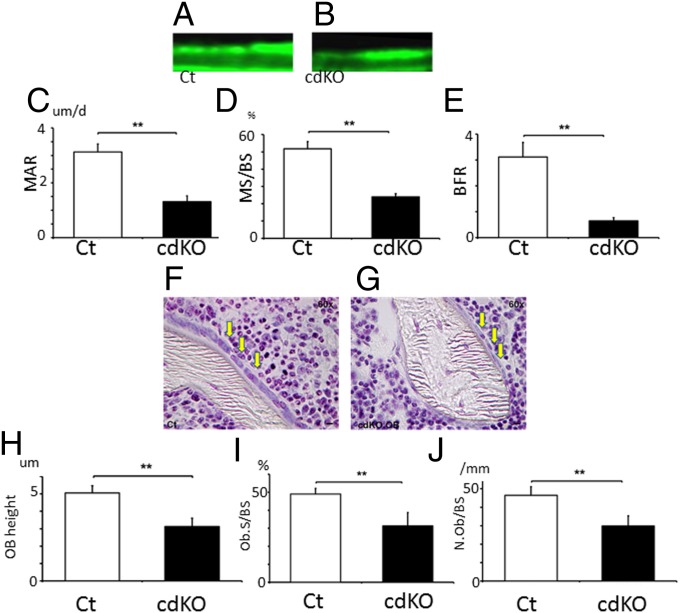

The reduction in bone mass by osteoblast-specific Nck deletion in the cdKO-OB mice could be due to either the reduction in bone formation or the enhancement of bone resorption or both. Therefore, the effects of Nck deficiency on osteoblastic bone formation were examined based on histomorphometry. Calcein-labeling experiments indicated that osteoblast-specific Nck deficiency in cdKO-OB decreased the interval width of the calcein bands compared with control (Fig. 6 A vs. B). Quantification revealed that Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts suppressed the mineral apposition rate (MAR), indicating attenuation in bone formation activity of individual osteoblasts in vivo (Fig. 6C). Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts also suppressed mineralized surface/bone surface (MS/BS), an indicator of the levels of the bone-forming osteoblast population (Fig. 6D). As a result of the suppression of these two parameter levels, Nck deficiency in cdKO-OB significantly suppressed the bone formation rate (BFR), which is obtained by multiplication of MAR and MS/BS (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, osteoblast height in vivo (Fig. 6 F–H), osteoblast surface per BS (Fig. 6I), as well as osteoblast number per BS (Fig. 6J) were all reduced in cdKO-OB compared with the levels of those parameters in the control. Thus, Nck plays a critical role in osteoblasts to support bone formation in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Conditional Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts suppresses bone formation and osteoblast shape. Calcein labeling for Ct (A) and cdKO-OB (B). (C) MAR. (D) MS/BS. (E) BFR. **P < 0.01. Six female mice per group. Ct mice were littermates. Villanueva bone staining of (F) Ct and (G) cdKO.OB. (H) Osteoblast height (n = 3 sections per group and 50 cells from each section were counted). (I) Osteoblast surface per BS. (J) Osteoblast number per BS. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Conditional Nck Double Deficiency in Osteoblasts Does Not Affect Bone Resorption.

As a reduction in bone mass could also be due to an increase in bone resorption, we examined the effects of Nck cdKO on osteoclastic activity. Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase staining of the decalcified sections of the bone in control (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A) and Nck cdKO-OB (SI Appendix, Fig. S15B) mice was conducted to quantify the osteoclast number (N.Oc) and osteoclast surface (Oc.S). Nck1 and Nck2 double deficiency in cdKO-OB mice did not affect the levels of N.Oc/BS (SI Appendix, Fig. S15C) and Oc.S/BS (SI Appendix, Fig. S15D). To further examine the role of Nck action in osteoclast development, bone marrow cells from cdKO-OB (SI Appendix, Fig. S15E) or control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S15F) were cultured in the presence of vitamin D3 and dexamethasone. Nck1 and Nck2 double deficiency in cdKO-OB did not affect the development of osteoclasts in the cultures of bone marrow cells compared with that in the bone marrow cells of control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S15 E–G). Similarly, coculture experiments using cdKO-OB–derived calvarial osteoblasts and wild-type spleen cells indicated that Nck-cdKO did not affect osteoclast development compared with wild-type calvarial osteoblasts (SI Appendix, Fig. S15H). Thus, the main cause for bone loss due to cdKO-OB is the suppression in bone formation.

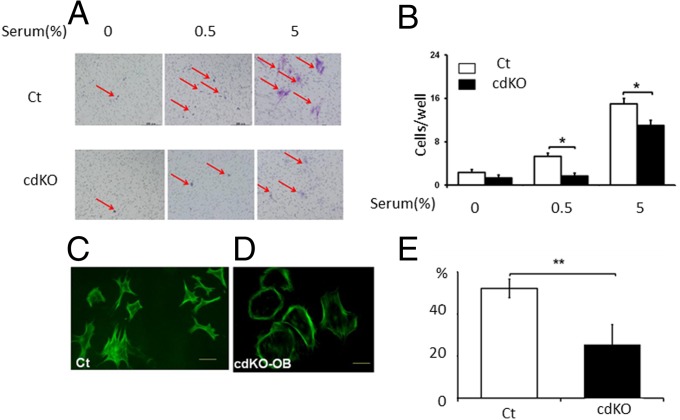

Conditional Nck Double Deficiency in Osteoblasts Suppresses Migration of Osteoblasts.

We further examined whether Nck deficiency in cdKO-OB mice affects the migration of osteoblasts. Primary cultures of osteoblasts were prepared from the calvarial bone of Nck-cdKO-OB mice or control mice, and the cells were subjected to testing for transwell migration activity toward serum. A transwell migration assay showed Nck deficiency in vivo suppressed migration activity of osteoblasts in comparison with the control (Fig. 7 A and B). The Nck-deficient osteoblasts were round in shape, suggesting a defect in actin filament organization in the cells. Phalloidin-fluorescein staining visualized the alteration in the pattern of actin-cytoskeletal organization in Nck cdKO-OB cells (Fig. 7 C vs. D). The effects of Nck deficiency in cdKO-OB cells on cell adhesion were also examined by plating the cells and counting the attached cells to the substrate [coverslips in the presence of 10% (vol/vol) FBS]. Nck deficiency in cdKO-OB suppressed the attachment of the osteoblasts to the substrate (Fig. 7E). Thus, osteoblasts where Nck is knocked down by siRNA and also osteoblasts where Nck is deleted genetically exhibit reduction in migrating activity.

Fig. 7.

Conditional Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts suppresses migration and attachment of the osteoblasts. (A) Transwell migration assay of the primary osteoblasts obtained from the 3–5-d-old Ct and cdKO-OB newborn calvaria. (B) Quantification. F-actin b in Ct (C) and cdKO-OB osteoblasts (D). (E) Ct and cdKO-OB–derived primary osteoblast cells adhered to the substrate. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

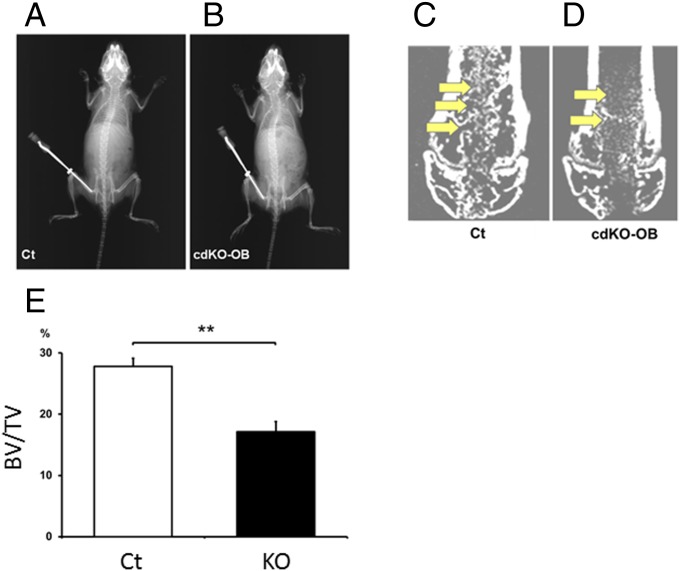

Conditional Nck Double Deficiency in Osteoblasts Suppresses the Levels of Newly Formed Bone in Vivo During the Repair of Bone Injury.

We asked whether the function of Nck in osteoblastic regulation observed in our experiments would be related to the repair of bone in vivo (Fig. 8 A and B). In wild type, newly formed bone in the region of bone defect was observed when the bone was examined 8 d after bone marrow ablation, based on micro-CT (Fig. 8C, arrows). In contrast, Nck deficiency (Nck cdKO-OB mice) reduced the levels of newly formed bone in the ablated defect region in comparison with the repair in wild-type mice, revealing that Nck deficiency suppresses the bone repair in the defect after marrow ablation in vivo (Fig. 8 D, arrows and E and SI Appendix). Histological examination revealed that newly formed bones in the ablated area in the bone marrow were woven bone and they were located in accordance with the new bones detected in micro-CT observation (SI Appendix, Fig. S16, arrows). Therefore, Nck deficiency in Nck cdKO-OB mice suppresses the repair of bone in the ablated region in vivo.

Fig. 8.

Conditional Nck double deficiency in osteoblasts suppresses new bone formation in vivo during the repair of bone injury. X-ray picture of Ct (A) and cdKO-OB (B) mice. Micro-CT analyses of the distal metaphyses of the femur of Ct (C) and cdKO-OB (D) mice 7 d after bone marrow ablation. (E) Quantification of the newly formed bone within the ablated region of Ct (C) and cdKO-OB (D) mice. **P < 0.01. Six mice were used per group.

Discussion

We discovered that Nck is involved in preosteoblastic/osteoblastic migration in in vitro as well as in vivo assays. Nck conditional double deficiency in osteoblasts suppresses BFR in vivo (SI Appendix, Discussion). Thus, Nck is a previously unidentified determinant of bone mass accrual. In conclusion, Nck is a critical regulator of preosteoblastic and osteoblastic migration and bone formation to maintain bone mass.

Materials and Methods

The knockdown system including Cre-flox, conditional knockout mice, bone histomorphomery, cell migration analysis, real-time RT-PCR, and the bone injury system were used for the analyses of Nck function (SI Appendix). All experiments were approved by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University institutional review board (IRB).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Tony Pawson and Nina Jones for providing us Nck knockout mice. We also thank Dr. T. J. Martin for advice. This research was supported by Japanese Ministry of Education (26253085), Tokyo Biochemistry Foundation (TBF), Investigator-Initiated Studies Program (IISP), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Abnormal Metabolism Treatment Research Foundation (AMTRF).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518253112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sims NA, Martin TJ. Coupling the activities of bone formation and resorption: A multitude of signals within the basic multicellular unit. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:481. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeman E. Bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19(3):219–233. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delaisse JM. The reversal phase of the bone-remodeling cycle: Cellular prerequisites for coupling resorption and formation. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:561. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2014.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirckx N, Van Hul M, Maes C. Osteoblast recruitment to sites of bone formation in skeletal development, homeostasis, and regeneration. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2013;99(3):170–191. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirakawa J, et al. Migration linked to FUCCI-indicated cell cycle is controlled by PTH and mechanical stress. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229(10):1353–1358. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eleniste PP, Huang S, Wayakanon K, Largura HW, Bruzzaniti A. Osteoblast differentiation and migration are regulated by dynamin GTPase activity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;46:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Y, et al. TGF-beta1-induced migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with formation. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):757–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xian L, et al. Matrix IGF-1 maintains bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1095–1101. doi: 10.1038/nm.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailly M, Condeelis J. Cell motility: Insights from the backstage. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(12):E292–E294. doi: 10.1038/ncb1202-e292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthukumaran P, Lim CT, Lee T. Estradiol influences the mechanical properties of human fetal osteoblasts through cytoskeletal changes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423(3):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birge RB, Knudsen BS, Besser D, Hanafusa H. SH2 and SH3-containing adaptor proteins: Redundant or independent mediators of intracellular signal transduction. Genes Cells. 1996;1(7):595–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bladt F, et al. The murine Nck SH2/SH3 adaptors are important for the development of mesoderm-derived embryonic structures and for regulating the cellular actin network. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(13):4586–4597. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4586-4597.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones N, et al. Nck adaptor proteins link nephrin to the actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes. Nature. 2006;440(7085):818–823. doi: 10.1038/nature04662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.