Significance

We investigated nonhuman primate prosociality within a decision-making behavioral framework. Our results suggest that macaques have a concept of their peers’ well being. The strength and originality of our experimental design is in challenging monkeys with several decisions involving both pleasant and unpleasant outcomes to self and others, thus allowing us to evaluate social motivation in different contexts. Behavioral measures, such as empathic eye blinking and mutual looking, show that the degrees of empathy and of willingness to interact with peers differ among individuals. These differences were mainly consistent with the preexisting social bonds displayed within our group-housed monkeys. Our results thus provide evidence of partner-dependent behavioral mechanisms shaping primates’ social decisions.

Keywords: social neuroscience, emotions, social gaze, eye blink, prosocial

Abstract

Primates live in highly social environments, where prosocial behaviors promote social bonds and cohesion and contribute to group members’ fitness. Despite a growing interest in the biological basis of nonhuman primates’ social interactions, their underlying motivations remain a matter of debate. We report that macaque monkeys take into account the welfare of their peers when making behavioral choices bringing about pleasant or unpleasant outcomes to a monkey partner. Two macaques took turns in making decisions that could impact their own welfare or their partner’s. Most monkeys were inclined to refrain from delivering a mildly aversive airpuff and to grant juice rewards to their partner. Choice consistency between these two types of outcome suggests that monkeys display coherent motivations in different social interactions. Furthermore, spontaneous affilitative group interactions in the home environment were mostly consistent with the measured social decisions, thus emphasizing the impact of preexisting social bonds on decision-making. Interestingly, unique behavioral markers predicted these decisions: benevolence was associated with enhanced mutual gaze and empathic eye blinking, whereas indifference or malevolence was associated with lower or suppressed such responses. Together our results suggest that prosocial decision-making is sustained by an intrinsic motivation for social affiliation and controlled through positive and negative vicarious reinforcements.

Animal sociality encompasses a broad range of behaviors presumed to influence social bonds and promote group cohesion (1–5). Although higher forms of altruism, such as costly care of unknown individuals or donations to charity, may require uniquely human mentalizing abilities, evidence supports an evolutionary continuity in the motivational and affective mechanisms that regulate attachment and affiliation (6–9). In nonhuman primates, the ubiquitous social play, grooming behavior, and their hormonal correlates suggest an ability to conceive what is pleasant or unpleasant for others (10–12). Pioneering experimental studies have shown that macaques can perceive and seek to alleviate their peers’ distress (13, 14) and more recent studies have attributed even to rodents the possibility of empathy and its promotion of helping behavior (2–4). Empathy is understood to refer to vicarious experiences of the affective states of others and is believed to improve adaptive social behaviors. Different components of empathy could be described, for instance, a cognitive one is related to the capacity to abstract other's experience, and another one depends on the emotional display of a conspecific. All of these components are known to be deeply influenced by the level of closeness existing between individuals (7). The ultimate, evolutionary basis of altruism and empathy is a topic of scientific interest that has been extensively discussed (7, 15–20). One of the recurrent issues is whether the motivations that drive prosocial behavior are selfish or purely altruistic. This question equally concerns the ubiquitous grooming behavior of nonhuman primates that has been shown to be pleasant for both participants (10, 12) or the nature of human altruism, as seen, for example, in the difficulty of discerning the inner motivations of blood donors (21). There are still appealing unanswered questions related to the underlying cognitive and affective mechanisms of nonhuman primates’ social behaviors. In particular, the implication of vicariously induced affective states in nonhuman primates’ social decision-making remains a matter of debate (7, 16, 22). Different theories have emphasized the role of proximate affective mechanisms in shaping behavior mainly through social reinforcement (6, 7, 23, 24). For example, it has been proposed that matching a peer’s affective state to one’s own prior or current state might be involved in social decision-making (7, 25). In addition to that, it is not known whether a common motivation drives social behavior across different contexts, such as sharing food or avoid harming a conspecific.

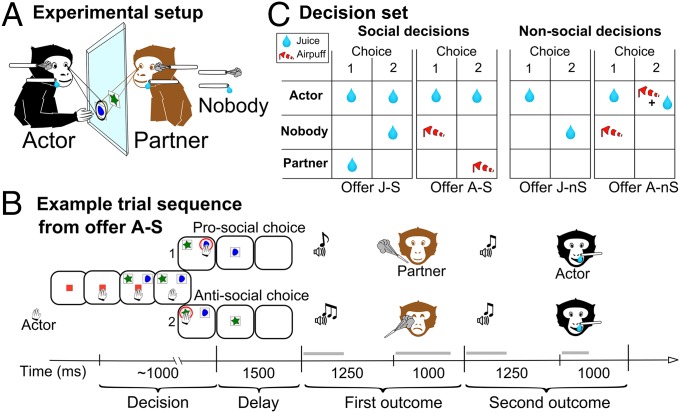

We investigated the motivational and affective basis of prosocial behavior through social decisions, asking whether macaques take into account the welfare of others (defined here as the exposure to a pleasant or unpleasant experience) when making choices leading to positive or negative outcomes on others. Specifically, we sought to determine whether their motivation is consistent for different outcome valences and is predicted by their sensitivity to a peer’s affective state. Pairs of animals sat face to face in a primate chair and alternately made forced-choice decisions by touching one of two visual cues that were projected on a transparent touch-sensitive panel (Fig. 1A), leading to the subsequent delivery of a combination of outcomes (Fig. 1 B and C). Social decisions consisted, for one monkey (the actor), in choosing an outcome for another monkey (the partner) vs. the same outcome to nobody. The outcome was either a drop of juice or an airpuff delivered close to the eyes. From the actor’s perspective, sensory events associated with partner and nobody outcomes were similar in every respect, except for their impact on the partner monkey. Choosing one or the other option did not determine the outcome for the actor monkey, who received a constant juice reward for touching one of the cues. Nonsocial decisions were interleaved with social decisions to control for the animals’ perception of the same outcomes when delivered to self. Eye-tracking devices were used to record the monkeys’ gaze and eye blinks as proxies of, respectively, social engagement and negative affect.

Fig. 1.

Task design. (A) Two monkeys (actor in black, partner in light brown) faced each other on either side of transparent touch panels on which visual stimuli were virtually projected. Both animals could observe the images and each other at all times. Tubes connected to solenoid devices allowed delivering the different outcomes. (B) Monkeys made social decisions regarding potential appetitive (offer J-S) and aversive (offer A-S) outcomes for the partner and nonsocial decisions regarding similar outcomes for self (offers J-nS and A-nS). For nonsocial decisions involving airpuffs and for social decisions, the actor was always rewarded with a drop of juice so as to maintain an adequate motivation level. (C) Typical trial sequence. A visual cue instructed the monkeys as to their role (actor or partner) in the current trial. The actor first touched this cue, triggering the appearance of two additional images. The monkey indicated its choice by touching one of these images. The unchosen image was then turned off and following a delay the partner’s and actor’s outcomes were delivered, preceded by unique 500-ms-long warning tones.

Results

Social and Nonsocial Decisions.

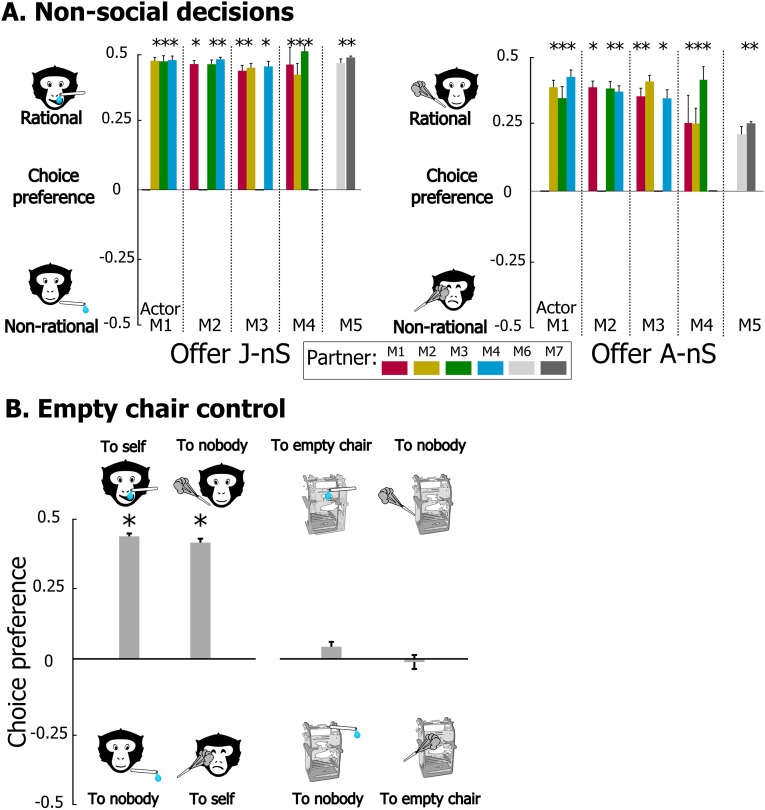

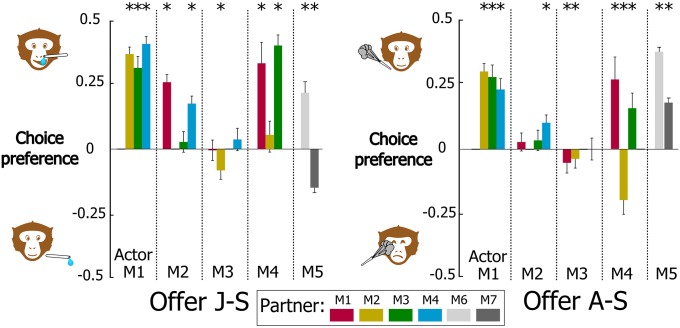

Results were analyzed for 14 dyads of monkeys (Table S1) in which the actor monkey made rational nonsocial decisions, i.e., chose to both acquire juice and avoid airpuffs for itself (respectively, offers J-nS and A-nS; Fig. S1). The dyads were formed of all pairings between four juvenile long-tailed macaques (M1–M4). Two additional dyads of adult rhesus macaques (M5 with M6 and M7) were also tested. Nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank) were used to determine whether choices made by the actor differed significantly from indifference (mean preference score = 0.0 in Fig. 2 and Fig. S1) between the two options. Our findings show that prosocial tendencies predominated over indifferent and antisocial ones (respectively, eight, four, and two dyads for juice outcomes and eight, three, and three dyads for airpuff outcomes, significantly prosocial and antisocial decisions: P < 0.05 or better), but individual monkeys exhibited different patterns of social decisions. One monkey (M1) displayed consistent prosocial choices with all of its partners, whereas all other animals showed a pattern of prosocial, antisocial, or indifferent choices that depended on partner identity and outcome valence (Fig. 2). It should be noted that monkeys were rarely as prosocial toward their partner as they were rational in their nonsocial choices (Fig. S1A). Interestingly, however, monkey M5 refrained from delivering an airpuff to M6, its female grooming partner, more than to itself (permutation test, P < 0.05), suggesting that observing another’s discomfort can be more aversive than experiencing it.

Table S1.

Number of sessions and mean number of trials completed

| Actor | Partner | |||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| Long-tailed monkeys | ||||

| M1 | — | 12 sessions, 654 ± 4 trials/offer | 10 sessions, 327 ± 13 trials/offer | 11 sessions, 454 ± 23 trials/offer |

| M2 | 25 sessions, 806 ± 22 trials/offer | — | 14 sessions, 626 ± 32 trials/offer | 29 sessions, 1,019 ± 12 trials/offer |

| M3 | 14 sessions, 606 ± 10 trials/offer | 13 sessions, 286 ± 20 trials/offer | — | 16 sessions, 534 ± 20 trials/offer |

| M4 | 4 sessions, 100 ± 5 trials/offer | 7 sessions, 267 ± 19 trials/offer | 6 sessions, 238 ± 12 trials/offer | — |

| Rhesus monkeys | M6 | M7 | ||

| M5 | 31 sessions, 1,567 ± 19 trials/offer | 2 sessions, 201 ± 5 trials/offer | — | — |

Trials per offer represent the mean number of trials performed for each of the four choice offers (two nonsocial and two social). Text color indicates the social tendency of the actor in front of each partner: green = benevolent, blue = indifferent, red = malevolent, and black = mixed. —, no data.

Fig. S1.

Choice preferences in nonsocial decisions and control experiments. (A) Nonsocial decisions. Positive values indicate rational decision-making, i.e., preference for granting juice (offer J-nS) and avoiding airpuff (offer A-nS) to self. (B) Control experiments in which monkey actors performed the choice task facing an empty nonhuman primate chair instead of an actual partner. Nonsocial trials were unaffected as monkeys chose to procure themselves juice and to avoid airpuff. On pseudosocial trials, monkeys chose indifferently between outcomes to nobody and to the empty-chair. Bar represented the average of 16 sessions performed by monkeys M1–M3. Mean preference scores for each monkey pair across all experimental sessions were computed as [choice1/(choice1 + choice2)] − 0.5. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Significant preference for one of the two options (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Fig. 2.

Social choice preferences. Positive values indicate prosocial decision-making, i.e., preference for granting juice (offer J-S) and avoiding airpuff (offer A-S) to the partner. Data are presented for M1-5 as actor and M1-4 and M6-7 as partner. Mean preference scores for each monkey pair across all experimental sessions were computed as [choice1/(choice1 + choice2)] − 0.5. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Significant preference for one of the two options (Wilcoxon signed-rank test); error bars represent SEM.

Furthermore, with a few exceptions (e.g., M2 toward M1 and M5 toward M7), in a majority of dyads (10/14), the actor monkey showed consistent tendency toward its partner for the social decisions involving juice and airpuff outcomes (respectively, offers J-S and A-S). As a check for possible uncontrolled factors biasing the monkeys’ decisions, we ran a number of sessions with monkeys facing an empty primate chair and found that their choices did not depart from indifference, whereas nonsocial decisions remained rational (Fig. S1B).

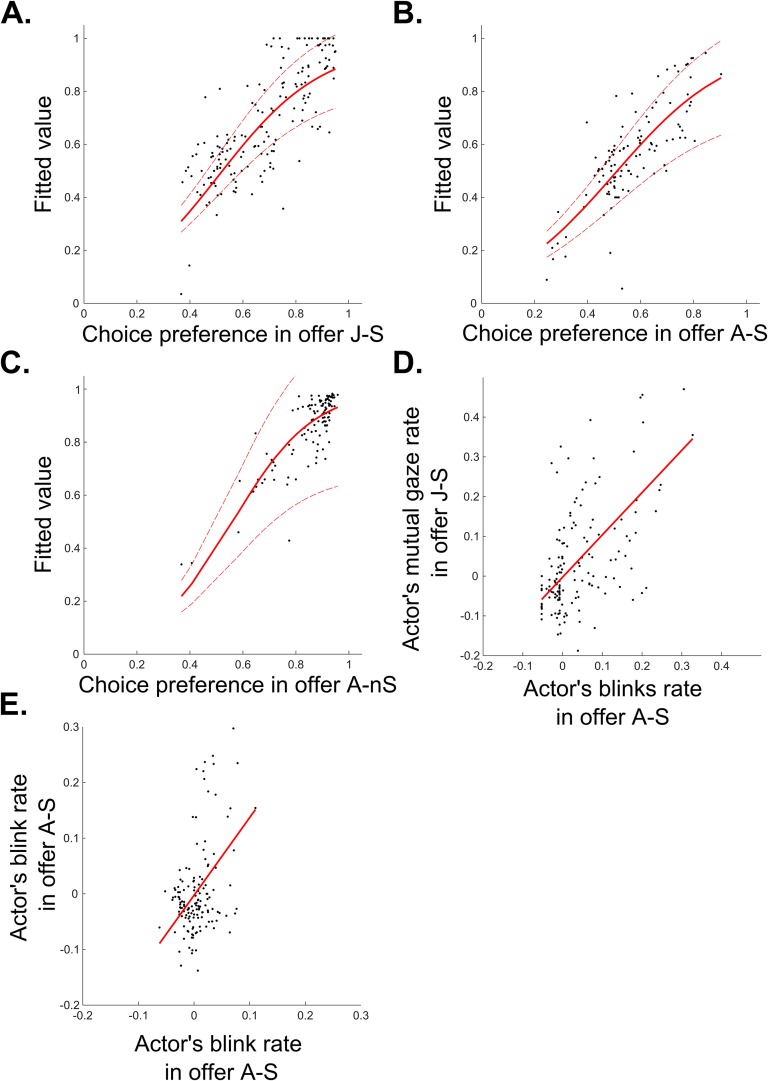

To investigate further what motivated these decisions, the results were analyzed on a session-by-session basis using multilevel models (26) that controlled for individual differences by considering actor and partner identity as a random effect. We found that the tendency to provide a pleasant stimulus to one’s partner reliably predicts withholding of an unpleasant one (P < 0.001; Table 1, Table S2, and Fig. S2 A and B). Consequently, actors’ social tendencies were characterized as “benevolent,” when significantly choosing mostly the prosocial options, “indifferent,” when choosing about equally the prosocial and antisocial options or “malevolent,” when choosing mostly the antisocial options. We then examined the monkey’s oculomotor behavior as potential marker of the underlying affective and motivational process explaining the actor’s decisions.

Table 1.

Multilevel model analysis of monkey’s decisions and oculomotor behaviors

| Observation | Fixed predictor | P | t | R2 |

| Choice preference in offer J-S | Mutual gaze rate in offer J-S | <0.001 | 6.24 | 0.44 |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | <0.001 | 5.43 | ||

| Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | <0.001 | 2.76 | 0.55 |

| Actor's and partner's blink rate in offer A-S | <0.001 | 3.11 | ||

| Choice preference in offer J-S | <0.001 | 3.5 | ||

| Choice preference in offer A-nS | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | <0.001 | 5.46 | 0.56 |

| Mutual gaze rate in offer J-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | <0.001 | 7.2 | 0.31 |

| Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | Partner's blink rate in offer A-S | <0.05 | 1.94 | 0.09 |

All of the models considered actor’s and partner’s identity as random predictors. These models were compared with null models including only the random effects (Table S2, theoretical likelihood ratio test). Then, to find the best fitting model, we compared models with different sets of predictors (Table S2, theoretical likelihood ratio test). Where needed, the pseudo-R2 algorithms of McFadden’s were used to compute R2. See Fig. S2 for a graphical representation.

Table S2.

Comparison between different models of social decision

| Observation | Fixed predictor | Random predictor | AIC | LogLik | P | ||

| Choice preference in offer J-S | Mutual gaze rate in offer J-S | Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor and partner identity | 1,178 | −585 | <0.001 | |

| Choice preference in offer J-S | — | — | Actor and partner identity | 1,254 | −625 | ||

| Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | Actor's and partner's blink rate in offer A-S | Choice preference in offer J-S | Actor and partner identity | 674 | −350 | <0.001 |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | — | — | — | Actor and partner identity | 704 | −332 | |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | Actor's and partner's blink rate in offer A-S | Choice preference in offer J-S | Actor and partner identity | 674 | −350 | <0.001 |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | — | Actor's and partner's blink rate in offer A-S | Choice preference in offer J-S | Actor and partner identity | 886 | −439 | |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | Actor's and partner's blink rate in offer A-S | Choice preference in offer J-S | Actor and partner identity | 674 | −350 | <0.001 |

| Choice preference in offer A-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | Choice preference in offer J-S | Actor and partner identity | 690 | −340 | |

| Choice preference in offer A-nS | Actor's blink rate in offer A-nS | Actor and partner identity | 657 | −324 | <0.001 | ||

| Choice preference in offer A-nS | — | Actor and partner identity | 684 | −339 | |||

| Mutual gaze rate in offer J-S | Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | Actor and partner identity | −192 | 100 | <0.001 | ||

| Mutual gaze rate in offer J-S | — | Actor and partner identity | −151 | 78 | |||

| Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | Partner's blink rate in offer A-S | Actor and partner identity | −282 | 145 | <0.05 | ||

| Actor's blink rate in offer A-S | — | Actor and partner identity | −278 | 143 | |||

The theoretical likelihood ratio test was used to estimate the validity of the mixed effects analyses on session-by-session performances. Here, null models with only the random effects are compared with the models of interest shown in Table 1, to test whether the latter have significantly better predictive value. The AIC (Akaike information criterion) and the Loglik (Log-likelihood) are measures of the relative quality of statistical models for a given set of data. Gray cells highlight the difference predictors used to evaluate the model specified in the row above it.

Fig. S2.

Graphical representation of monkeys’ decisions and behaviors predictions. All of these models considered the actors’ and partners’ identity as a random predictor. Individual data points are mean values on a given testing session. Dotted lines represent the SE of regression Plots in A–C show the best model account for different social and nonsocial decisions. (A) Prediction of the actor’s social decision in offer J-S. The model considered the choice preference in offer A-S and the anticipatory mutual gaze rate in offer J-S as predictor. (B) Prediction of the actor’s social decision in offer A-S. The model considered choice preference in offer J-S, anticipatory blink rate in offer A-nS and the interaction between actor’s and partner’s anticipatory blinks in offer A-S as predictors. (C) Prediction of the actor’s nonsocial decision in offer A-nS. The model considered the anticipatory blink rate in offer A-nS as predictor. (D) Correlation between actor’s blink in offer A-S and mutual gaze rate in offer J-S. (E) Correlation between actor’s and partner’s anticipatory blink rate in offer A-S.

Social Gaze.

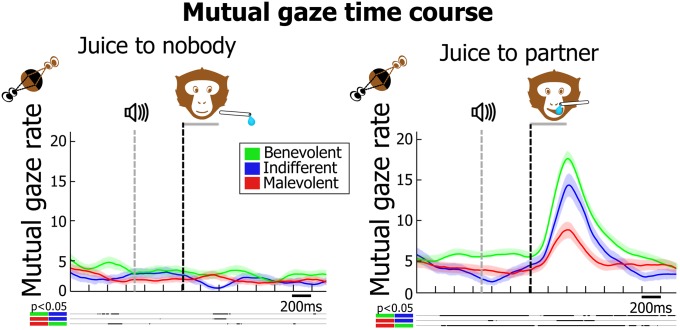

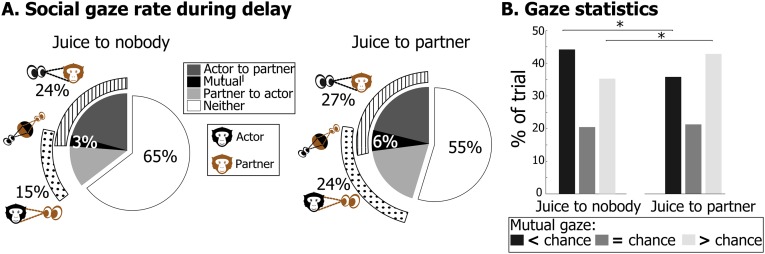

A social region of interest (ROI) was defined as the area encompassing the partner’s face and corresponding to ∼15% of the visual field. Social gaze was defined as the percentage of time a monkey fixated into this ROI, and mutual gaze as the percentage of time the gaze of both monkeys coincided. Social and mutual gaze increased during the delay period and was enhanced on trials in which the actor chose to grant juice to the partner, compared with nobody (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3A; permutation test, P < 0.05). Logically, when both monkeys’ social gaze increases, the probability of gaze coincidence is expected to increase as well. However, if mutual looking is an actively controlled social interaction (i.e., if monkeys deliberately chose to sustain or avoid each other’s gaze), its occurrence might be expected to be different from predicted by chance. This hypothesis was tested using a permutation-based analysis (Fig. S3B). For every trial in the dataset, actual mutual gaze rate was compared with its theoretical distribution and considered to be below or above chance if it was, respectively, inferior or superior to a CI set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed test). For more than 70% of trials, mutual gaze rates could not be explained by random intersection of the actor’s and the partner’s gaze. Interestingly, when the actor chose to grant juice to its partner, the proportion of trials with above- and below-chance mutual gaze rates, respectively, increased and decreased, compared with when the actor withheld juice from its partner. This result suggests that when prosocial decisions were made, both animals actively sought to interact more with each other through gaze. Further analyses show that mutual gaze rate predicts, on a session-by-session basis, the animals’ degree of prosociality (Table 1, Table S2, and Fig. S2A; P < 0.001) and discriminates between different actors’ decisional tendencies [ANOVA, F(2) = 3.77, P < 0.01, before juice delivery; F(2) = 3.07, P < 0.05, after juice delivery]. This modulation is apparent in Fig. 3, Right, showing that mutual gaze increases before and during juice delivery in dyads that include a benevolent actor.

Fig. 3.

Mutual looking rate for the different social decider profiles for juice to nobody and juice to partner choices. Thick lines below the plot indicate significant pairwise differences (permutation test, P < 0.05); shading overlays on the traces represent SEM. The number of sessions considered for benevolent, indifferent, and malevolent actors is, respectively, equal to 97, 30, and 37 sessions.

Fig. S3.

Gaze behavior of actor and partner during social decisions. (A) Pie charts of mean gaze distribution of all monkey pairs computed during the delay interval that followed decisions to grant juice to nobody or to partner (n = 164). Hatched and dotted arcs represent total social gaze of the actor and partner, respectively. (B) Results of single trial analysis of gaze coincidence. The permutation-based statistical procedure (see main text) allowed to classify mutual gaze rate in each trial as <, =, or > chance intersection of the two monkeys’ gaze within the face ROI.

Eye Blinks.

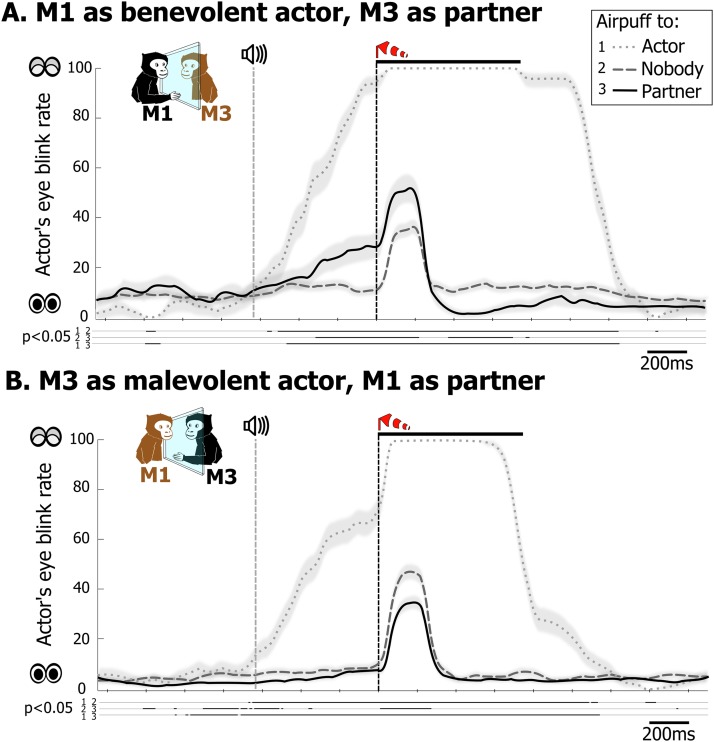

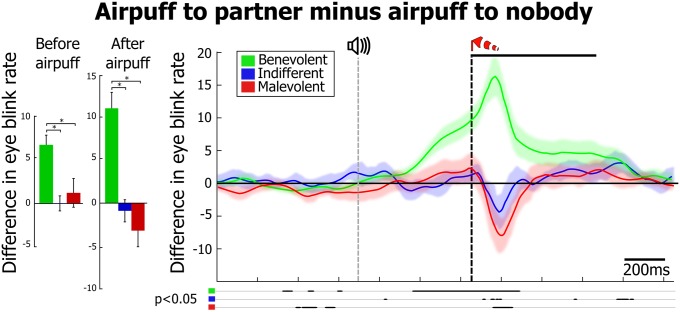

Eye blinking is a primary response to an airpuff near the eyeball. A large increase in eye blinking rate was recorded in the actor monkey when occasionally delivering itself an airpuff (up to 21% of nonsocial decision trials; Fig. S4, dotted curves). This response reached significance (permutation test, P < 0.05) around the onset of the warning tone, indicating that the monkeys anticipated the event. Anticipatory blinking was also associated with increased airpuff avoidance (Table 1 and Fig. S2C; R2 = 0.56, P < 0.001), consistent with a negative affective state being induced by the aversive outcome prediction. More interestingly, observing an airpuff being delivered to the partner was also associated with changes in blink rate, and the strength of this response was a distinctive feature of the actors’ prosocial tendencies: benevolent monkeys showed larger blink response in anticipation of, and in reaction to, the partner’s airpuff [Fig. 4; ANOVA, before airpuff delivery: F(2) = 3.96, P < 0.05, after airpuff delivery: F(2) = 9.04, P < 0.001; Fig. S4; permutation test, P < 0.05]. This response was smaller than during an airpuff to self (P < 0.05), but significantly higher than during an airpuff to nobody (P < 0.05). By contrast, when exhibiting indifferent and malevolent social decision tendencies, monkey actors, respectively, did not react or, surprisingly, underreacted (P < 0.05) to an aversive stimulus on their partner. The specificity of such anticipatory an enhanced blink response to observed airpuffs strongly argues for an intrinsically social underlying process. As the partner monkey, to whom the airpuff was directed, also showed anticipatory blinks, it is possible that the actor’s behavior was mirroring its partner’s. This effect would be consistent with work on motor mimicry in monkeys (27, 28) and with the observation that humans with higher empathy score are more likely to mimic other’s eye blinks (29). The statistical model that best account for social choices involving aversive stimuli includes the interaction of actor and partner anticipatory blinking (Table 1, Table S2, and Fig. S2B), and we found a significant but quite weak degree of synchronization of the actor and partner’s anticipatory blink rates (Table 1 and Fig. S2E; R2 = 0.09, P < 0.05). This low correlation suggests that more covert aspects of the actor monkey’s affective state is involved in the generation of empathic blinking. Overall, these results argue for eye blinking as a meaningful indicator of monkeys’ negative affective reaction to others’ discomfort and suggest that the decision to avoid inflicting an unpleasant stimulus to a conspecific might be dependent both on the partner’s affective display and the actor’s prior experience with aversive stimuli.

Fig. S4.

Examples of monkeys’ eyes blink behavior when experiencing and when observing an airpuff. (A) Time course of mean eye blink rate in the outcome phase for benevolent actor M1 in the M1–M3 dyad, when the actor, the partner, or nobody received an airpuff. (B) Time course of mean eye blink rate for the malevolent actor M3. Both plots show that the strongest eye blink response is to an airpuff to self. Both actors also reacted with an increase in blink rate to the delivery of an airpuff to nobody. However, relative to the latter blink response, M1 anticipated and overreacted to an airpuff to the partner, whereas M3 underreacted to this event. Thick lines below the plots indicate significant pairwise differences (permutation test, P < 0.05); shading overlays on the traces represent SEM.

Fig. 4.

Eye blink behavior when experiencing and when observing an airpuff. Net effect on blink rate of observing the partner receiving an airpuff, computed as the difference [airpuff to partner – airpuff to nobody] for benevolent, indifferent, and malevolent actors (n = 97, 30, and 37 sessions, respectively). Shading overlays on the traces represent SEM. Bar graphs show mean blink rate differences computed 300 ms before and after airpuff delivery. Thick lines below the plot indicate significant pairwise differences (permutation test, P < 0.05). *Significant pairwise difference (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05); error bars represent SEM.

Mutual gaze and eye blinking thus provide two windows into a monkey’s internal affective state. As both are modulated in accordance with the animal’s social tendencies, one could hypothesize a shared motivational basis. Results in Table 1 and Fig. S2D indeed show a relation between mutual gaze (offer J-S) and eye blinking in the context of airpuff avoidance (offer A-S; R2 = 0.31, P < 0.001).

Social Network Structure.

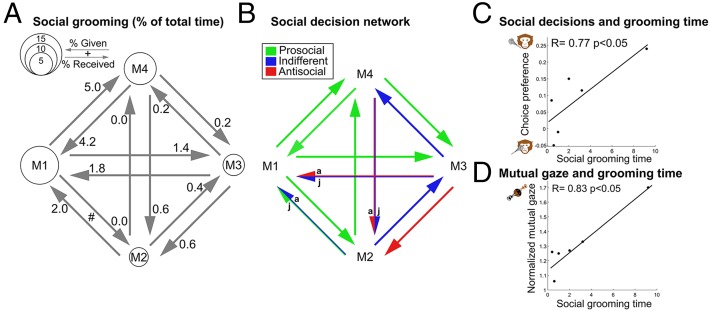

Social organization and affiliative behavior patterns of the four long-tailed macaques were assessed using manual and automatic scoring of their spontaneous interactions (30). (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5). These analyses highlight several characteristics of the studied macaque group: (i) monkeys that cared about others’ welfare in the laboratory spent more time in social grooming than other dyads (Fig. 5 B and C; Spearman rank correlation permutation test, R = 0.77, P < 0.05 for offer A-S; the correlation for offer J-S did not reach significance, R = 0.49, P > 0.1); (ii) the only dyad showing mutually benevolent decision tendencies for both juice granting and airpuff avoidance involved the two monkeys who exhibited the strongest mutual grooming interactions (M1 and M4; Fig. 5A); and (iii) the only monkey who showed benevolent decision tendencies toward all of its partners was M1, the dominant member of the group. These observations, together with the positive correlation found between social grooming and mutual gaze rate (Fig. 5D, Spearman rank correlation permutation test, R = 0.83, P < 0.05), highlights the consistency between actual social affiliation patterns in the monkeys’ living space and the valuation process taking place during social decisions. The observation that the dominant member of this long-tailed minicolony is also the most benevolent monkey is somewhat anecdotal but consistent with prior work (31–33).

Fig. 5.

Social affiliation structure of long-tailed macaques and relation to social decision-making tendencies. (A) Social grooming network. Circle diameter is proportional to the total percentage of time (in a 3-h cycle, 10 recording sessions) spent in allo-grooming activity by each monkey. Arrows show directionality of grooming and numbers, the percentage of time dedicated to grooming a given partner. (B) Schematic of the social decision network based on data from Fig. 2, allowing direct comparisons between spontaneous social behavior and decision tendencies. (C) Correlation between social decisions regarding aversive outcomes (offer A-S) and mean social grooming time in the home environment (R = 0.77, P < 0.05). (D) Correlation between mutual gaze rate of monkeys in the social decision task and mean social grooming time in the home environment (R = 0.83, P < 0.05). Mutual gaze (MG) was normalized using the ratio: MG[juice to partner]/(MG[juice to partner] + MG[juice to nobody]). The dataset includes 10 recording sessions conducted during the same period that social decisions data were collected. Each dot in the correlations represents a monkey dyad.

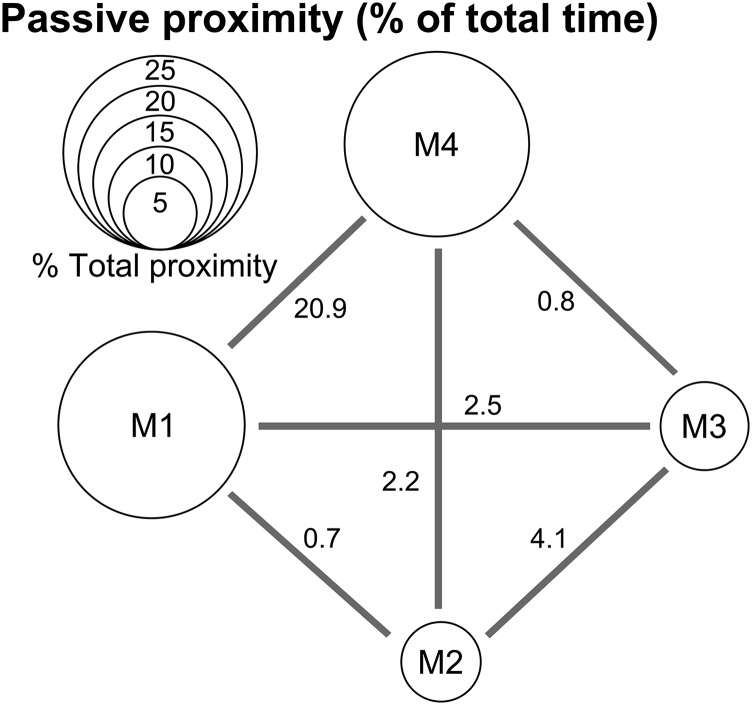

Fig. S5.

Social affiliation structure of the minicolony of long-tailed macaques: proximity network. Circle diameter is proportional to the total percentage of time (in a 3-h cycle) spent in passive proximity to other monkeys [net proximity computed as (total proximity) – (total given grooming + total received grooming)]. Line segments and numbers represent the breakdown of this variable as a function of monkey dyad.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that macaques were spontaneously inclined to act prosocially, even in the absence of explicit, immediate incentives to do so. Whichever decision was taken, the consequence to self, i.e., the expected value, of each option was the same: a fixed amount of juice. Thus, according to a strict utility hypothesis, monkeys should have shown no systematic choice preference: the consequence to the partner was task irrelevant and the two monkeys did not have to coordinate their actions or adopt a joint strategy. Despite this, what happened to the partner shaped decisions in a large majority of the monkey pairs tested (11/14; Fig. 2), with a significant and consistent prosocial bias in more than half of cases. Prior experiments that have used appetitive (32–38) or aversive outcomes (13) to study prosocial behavior in nonhuman primates raise the question of the underlying mechanisms: why do animals make generous choices or refrain from causing harm to others? The observation that monkeys chose to grant juice (or food) to a partner is offered as evidence of motivation for object giving or sharing, but an alternative explanation is that social stimuli preferentially attract the monkeys’ attention, such that the differential salience of the two outcomes is sufficient to positively reinforce prosocial choices. Monkeys might enjoy watching a partner eating or drinking more than waiting passively for the next trial or than seeing a drop of juice falling into a container However, social decisions involving aversive stimuli, such as older studies that challenged monkeys to forego a food reward to save a partner from electrical shock (13), are more difficult to reconcile with a purely attentional interpretation. The present results clearly refute it, as the monkeys did not consistently choose the outcomes that include the social stimulus across appetitive and aversive social decisions. The partner licking a drop of juice in the first case, or wincing in response to an airpuff in the second, were both more salient than their respective alternatives. However, rates of juice giving and of airpuff avoidance to the partner were correlated, which implies that the monkeys’ choice preferences must have been influenced by the social significance, not only by the salience of those events. The kind of social dilemmas that these monkeys were challenged with have no obvious equivalence in more ecological settings, but nevertheless shed light on the cognitive and affective mechanisms underlying prosocial behavior. Previous studies using allocation tasks also reported that, under certain circumstances, monkeys can grant juice or food to their conspecifics. Massen et al. (31, 32, 34, 39) observed such prosocial behavior, especially among dominant animals and between kin in a colony of 20 long-tailed macaques, and Chang et al. (33) found that individually housed, unrelated rhesus monkeys allocated juice to a partner, but needed no reward to reveal a prosocial tendency. Despite differences in experimental procedures, choice contexts, living conditions or species, which might influence the social decision framework of macaques, choices in such tasks appear to involve intrinsically social mechanisms. Interesting partner-dependent and individual differences in decision-making pattern were observed. However, given the relatively small number of animals tested, defining the role of sex difference, hierarchy, or developmental stage in nonhuman primates’ social decisions must await further investigations. The unique features of the present study, particularly the combination of appetitive and aversive social outcomes, the analysis of multiple behavioral markers, and the assessment of social decisions between group-housed animals with well-defined network structure, allowed us to address the following unresolved issues.

Are Social Stimuli Vicarious Reinforcers?

The quest for proximal mechanisms of prosociality has led authors to hypothesize that prosocial behavior is shaped by the reinforcing value of certain social events (33). For instance, the view of a conspecific receiving a drop of juice could be experienced as pleasant, recruit brain reward circuits and lead to a preference for the prosocial option (33). Conversely, a conspecific receiving an airpuff could be perceived as unpleasant, deactivate reward circuits, and negatively reinforce the antisocial option. The view that prosocial actions generate their own rewards is somewhat related to the “warm glow” hypothesis of human altruism: doing good makes us feel good (40, 41). Similarly, empathy theories (7, 8) postulates that prosocial behavior aimed at suffering individuals alleviates vicariously experienced pain (23). In this study, what is the evidence for the involvement of such empathy-like mechanisms and are these satisfactory explanations of macaque prosocial decision-making? The behavioral data presented here suggest that granting juice to a partner triggers social interactions that might act as positive or negative vicarious reinforcers, depending on preexisting bonds. We also found that viewing a partner experiencing an airpuff triggers a defensive blinking response, indicative of the negative affective impact of the partner’s discomfort upon the observer. However, the monkey’s social decision-making clearly exhibited partner selectivity, as previously observed in primates and rodents (4, 31–33, 35, 42, 43). There thus seems to be more at play than vicarious rewarding or punishing “social stimuli.” Factors related to personality traits and preexisting social bonds should also modulate social decision-making, suggesting that macaque’s vicarious affect is cognitively controlled. These different points are discussed next.

Is Mutual Gaze a Marker of Social Reward?

In a social context, gaze is used both to gather information and to communicate with peers, mainly through gaze following and joint attention as well as direct eye contact (44–47). Social gaze started during the delay following the actor’s choice, ruling out exclusively stimulus-driven responses, and was particularly enhanced in the partner monkey. In agreement with other observations (46), we found that macaques actively control their social looking. Indeed, actor and partner monkeys either avoided meeting the other’s gaze or sustained it more than would be predicted if their respective gaze patterns were independently generated. This interaction is expected because, in the social environment of macaques, staring at conspecifics may be risky and its potential cost needs to be balanced with its usefulness (47). Indeed, during negative social interactions, eye contact is generally threatening for macaques. Here, we find that mutual gaze rate is correlated with prosociality and with another proxy of affiliation: the rate of social grooming. These associations indicate that, in the context of juice allocation, mutual gaze could express an intrinsic motivation for social affiliation. Thus, consistently with other observations, we suggest that monkeys’ eye contact can also represent a form of positive social interaction (44, 48–50). The vicarious reward hypothesis suggests that viewing a conspecific receiving juice might activate, through some form of mirror mechanism, the same reward circuit as an actual drop of juice (33). Here, consistently with other nonhuman primate study (22), we propose that, rather than the mere sight of juice delivery, it is the social attention received from the partner and the gaze exchanges that act as social rewards or punishment, promoting or preventing prosocial behavior through the monkeys’ social attachment system. In other words, our results suggest that voluntary social interaction through gaze might be a social reinforcer and thus play an important role in the experience of juice allocation in macaques. This hypothesis is coherent with the fact that macaques display partner-dependent cofeeding tolerance (42) (a tendency which might be evolutionary rooted as humans and bonobos are usually seeking to eat in social context rather than alone) (51, 52).

Is Eye Blinking a Marker of Negative and Vicarious Affect?

Enhanced eye blinking when watching a peer receiving an airpuff offers evidence of induced negative affect in the observer. Our finding of similar, and correlated behavioral responses to the direct experience of an aversive stimulus and to the observation of its impact upon a peer would appear consistent with simulation theories of empathy (7–9, 21). Empathic-like responses have already been reported in others animal studies (2, 5, 7, 53–56). Such behavioral responses are usually either contagious, modulated by past experience, and/or dependent on the partner identity. The singular empathic response that we have described here contains all of these features. However, further experiment would be needed to know to which extent the macaques’ empathic response reflected their understanding of what their peers were experiencing. In addition, eye blinking is also related to the generalized startle reflex, which has been shown to be gated by affective states (57, 58). Thus, anticipatory eye blinking to observed airpuffs may involve a form of conditioned startle response modulated by the perceived facial affective state of the partner monkey. Regardless of its nature, the fact that the presence and amplitude of this physiological response were related to the monkeys’ prosocial tendencies further argues for the implication of vicarious mechanisms in shaping nonhuman primates social decisions.

Why Is Rudimentary Empathy Involved in Macaques’ Social Decision-Making?

Ethological observations of complex social behaviors such as coalition building or reconciliations (59, 60) emphasize that nonhuman primates maintain preferential relationships that can be influenced by diverse social variables such as personality traits, rank, or services that a peer can provide (61, 62). Hence, to act in accordance with their motivation for social interaction, macaques need to be able to predict the consequences of their behavior on future social bonds. Moreover, greeting rituals constitute evidence that macaques react to other’s absence, suggesting a persistent mental representation and a specific need to interact with a given conspecific (63, 64). Beyond the claim that macaques are natural born politicians, we believe that a cognitive control of vicarious affect allows macaques to include (or discard) others’ welfare into their social decision framework and thus shape their social network. From an evolutionary and ecological perspective, the cognitive abilities of each species should be adapted to their social challenges. Different factors can strengthen or weaken social cohesion, including the affective state of individual group members (65–69). Seemingly gratuitous aggressions are used, especially in despotic species, to maintain the group’s hierarchy, but a disproportionate use of aggressive behaviors would needlessly weaken the troop’s cohesion. We can thus propose that the evolutionary benefit of rudimentary empathy would be linked to a better management of social structure which consequently might increase individual fitness.

To conclude, the convergence of our measures of social decision-making, online social interaction, vicarious affect, and social affiliation demonstrate the existence of internal states that coherently shape the value nonhuman primates assign to others’ welfare and to their social interactions, together fostering prosocial behaviors. Our results provide insights into the proximal mechanisms that drive primate social preferences and pave the way toward understanding the biological basis of the cognitive and affective mechanisms involved in nonhuman primates’ social decision-making.

Methods

Four nonkin juvenile male long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) and three rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were used as subjects. The social status and interaction patterns of the long-tailed macaques were characterized by both manual and automated ethological measures using a custom-designed multicamera 3D tracking system (30) (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5). Choice preferences, eye position, and eye blink signals of actor and partners monkeys in the social decision task were recorded and processed using experimental and data analysis procedures detailed in SI Methods. All experimental procedures were approved by the animal care committee (Department of Veterinary Services, Health & Protection of Animals, permit no. 69 029 0401) and the Biology Department of the University Claude Bernard Lyon 1, in conformity with the European Community standards for the care and use of laboratory animals (European Community Council Directive No. 86–609).

SI Methods

Animals.

Four nonkin but group-housed juvenile male long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) (aged 3 ± 0.15 y; weight, 5.7 ± 0.8 kg) with well-characterized social status and interaction patterns were used as subjects. They were housed as a minicolony in a large enclosure (15 m3) that allowed direct physical interaction but also allowed isolating the monkeys when needed through a system of sliding partitions. When isolated, the monkeys could communicate visually and vocally at all times. Animals were fed with monkey chow, fresh fruits, and vegetables and placed under water restriction with 1 d of free access to water each week. The cages were enriched with different toys or substrates that promote social play, curiosity, object manipulation, and foraging. Three rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta, two males and one female, aged 14, 16, and 14 y and weight 8.8, 11.8, and 5.6 kg, respectively), were also used. To motivate the animals to perform the social decision task, and notably because of the presence of mildly aversive stimuli, access to water in the home cage was controlled. The animals normally earned between 50 and 200 mL juice during an experimental session. If the criterion of 25 mL/kg was not reached during a given session, extra fluid and fruits were given as needed at the end of each day to maintain proper fluid balance. Because the experiments were conducted over a period of several months, daily fluid intake was adjusted as needed to maintain an optimal motivation level corresponding to the monkey performing at least 100 correct trials per experimental session. No animal was let to reach a dehydration criterion (i.e., a loss of more than 10% of its weight) Water restriction is likely to involve a certain level of unavoidable stress, and whether this may alter social decision tendencies at the group level (e.g., increase or decrease overall prosocial tendencies) is an open question.

Surgery.

All experimental procedures were approved by the animal care committee (Department of Veterinary Services, Health & Protection of Animals; permit no. 69 029 0401) and the Biology Department of the University Claude Bernard Lyon 1, in conformity with the European Community standards for the care and use of laboratory animals [European Community Council Directive No. 86–609]. During a single sterile surgery performed under isoflurane anesthesia, animals were prepared for implantation of a head-restraint device to allow eye tracking. The monkeys were then left to recover for at least 1 mo with the proper antibiotic coverage, and pain-relievers given as needed.

Behavioral Procedures.

Experiments were conducted in a semidark room. Two monkeys were seated in a primate chair with their head immobilized, facing each other but separated by two transparent touch-sensitive panels (Elo Touch Solutions; 6-mm Securetouch) mounted back to back (Fig. 1A). The setup was designed to allow the two monkeys to interact visually with each other and to make behavioral choices using the touch panel interface. Each monkey had a feeder tube placed near its lips to deliver finite quantities of juice, using a gravity-based solenoid device (Crist Instruments). Discrete air puffs (4 bars, 800 ms) could also be delivered close to the monkeys’ left or right eye through a tubing system connected to solenoid device and pressure gauge. Each animal’s eye position was monitored using two Eye-Trac 6 (ASL) infrared video eye trackers (200-Hz sampling rate). Using a video projector and two semitransparent mirrors (beam splitter, 30% reflection, 70% transmission; Edmund Optics), the same visual stimuli were virtually projected in the visual plane of the two touch panels. Every trial began with the appearance of a central square target, the color of which specified which monkey was to be the actor (Fig. 1B). In the decision phase, this monkey had to touch and hold this target, triggering the appearance, 500 ms later, of two visual cues at randomly selected locations on the screen. Each cue shape was associated with a unique set of outcomes to the actor, the partner, or nobody. Five hundred milliseconds after the onset of the cues, the square target was extinguished, prompting the monkey to make its choice by touching the corresponding cue. During the delay phase, the unchosen cue was extinguished, and the chosen target reappeared at the center of the screen for 500 ms to confirm the actor’s choice. Monkeys waited a further 1,000 ms to enter into the outcome sequence. The partner’s (or nobody’s) outcome was delivered first, preceded by a warning tone (for the nobody choice, the drop of juice visibly fell into an empty container, and the airpuff was delivered in an empty space). The actor’s outcome was delivered next, also preceded by a tone. The two monkeys alternated as actor and partner on successive blocks of 45 s. Different outcome pairs were presented on successive trials from a predefined set of four possible offers (Fig. 1C), in randomly interleaved order. To facilitate learning of the association between a given cue shape, blue LEDs were attached to the juice reward tube and white LEDs to airpuff tubes. The LEDs were turned on simultaneously with the opening of the solenoids. In addition, a specific 500-ms-long sound was also played 1,250 ms before the onset of each outcome event. Unique sets of visual and auditory cues were associated with the outcomes delivered to each monkey. Visual cues were equalized for luminance and sound cues for intensity using Matlab R2010 (The Mathworks). Behavioral control and visual displays were under the control of PCs running the REX/VEX system (70). All analog and digital data were logged and synchronized using Spike2 (Cambridge Electronic Design).

Because of the presence of mildly aversive stimuli in the experimental task, monkeys needed to be maintained under fluid control. Extra fluid and fruits could be given as needed at the end of each day to maintain proper fluid balance. Because the experiments were conducted over a period of several months, daily fluid intake was adjusted as needed to maintain an optimal motivation level corresponding to the monkey performing a number of at least 100 correct trials per experimental sessions.

Automatic and Manual Home Cage Social Interaction Assessment.

Rate and direction of allo-grooming behavior was scored manually from raw video recordings (Fig. 5A). In addition, we used a custom-designed multicamera 3D tracking system (30) to record and monitor the behavior of primates in their living space. This system can track the location of multiple animals in real time, provided they are wearing a unique color marker (restraining collar or head-post). Animal positions (X, Y, Z) were estimated by triangulation from the set of image coordinates of their respective color targets when viewed by at least two cameras. Measurements for four animals and one colored toy were taken simultaneously at a 15-Hz rate, with a nominal spatial accuracy of 1 cm. Toy manipulation was also used to assess the hierarchy within the group (71). Position recordings were then processed to derive animal relevant behavioral measurements such as the proximity with a peer (Fig. S5). Group hierarchy was established using order of access to a water bottle and novel objects (hence the attribution of the labels M1 through M4 to these monkeys, in descending social rank order; Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05) (71–73). Social bonding was determined by computing both a proximity network (defined as interdistance < 30 cm) and a social grooming network (10 recording sessions of 3 h each; Fig. 5A and Fig. S5).

Data Analysis.

Choice data (14 dyads, >30,000 individual decision trials) and oculomotor signals were analyzed using custom scripts written in Matlab R2010 and R2015. In Fig. 2, choice preference was computed as a simple proportion: [choice1/(choice1 + choice2)] − 0.5, such that a ratio of 0 corresponds to the point of indifference between the two options. Eye position traces from one eye of each monkey were filtered and smoothed and used to compute social gaze epochs. Eye blinks detected by the eye tracker were also smoothed and logged as blink events if lasting longer than 50 ms. The data thus obtained were plotted using custom software, and statistical analyses were conducted on temporal windows of interest. For the nonparametric Spearman rank correlation analysis, mutual gaze was normalized using the following methods: choice1/(choice1 + choice2). Because dyads cannot be treated as independent data points, random permutation evaluation of the correlations were used (Fig. 5 C and D; 1,000 permutations). The time windows used to analyze the anticipatory or reactive variations in social gaze or blinking rate were 300 ms, before or after the outcome delivery. Results were also analyzed using multilevel algorithms (generalized linear mixed-effects models), controlling for actor and partner identity as random effects (26). As fixed effects, we included choice preferences and oculomotor behaviors that were averaged on a 300-ms window taken either before or after the outcome delivery. We checked for normality and homogeneity by visual inspection of plots of residuals against fitted values. To assess the validity of the mixed effects analyses, we compared the models of interest with the null models with only the random effects and models with different predictors (Table S2, theoretical likelihood ratio test). Pseudo-R2 algorithms used were McFadden’s.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mathieu Pozzobon for assistance in animal training, Pierre Baraduc for statistical analysis support and helpful comments on the manuscript, Serge Pinède for technical support, and Angela Sirigu and Gilles Reymond for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also thank Jean-Luc Charieau and Fabrice Hérant for expert animal care. This work was supported by the “Laboratory of Excellence” framework (ANR-11–LABEX-0042) of University de Lyon within the program “Investissement d’Avenir” and by grants from the Rhône-Alpes Region and from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (BLAN-SVSE4-023-01, BS4-0010-01) (to J.-R.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1504454112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cheney D, Seyfarth R, Smuts B. Social relationships and social cognition in nonhuman primates. Science. 1986;234(4782):1361–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.3538419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ami Bartal I, Decety J, Mason P. Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science. 2011;334(6061):1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.1210789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atsak P, et al. Experience modulates vicarious freezing in rats: A model for empathy. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Ami Bartal I, Rodgers DA, Bernardez Sarria MS, Decety J, Mason P. Pro-social behavior in rats is modulated by social experience. eLife. 2014;3:e01385. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostojić L, Shaw RC, Cheke LG, Clayton NS. Evidence suggesting that desire-state attribution may govern food sharing in Eurasian jays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(10):4123–4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209926110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decety J. The neuroevolution of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1231(1):35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25(1):1–20, discussion 20–71. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batson CD. These things called empathy: Eight related but distinct phenomena. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2009. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Insel TR, Young LJ. The neurobiology of attachment. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(2):129–136. doi: 10.1038/35053579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keverne EB, Martensz ND, Tuite B. Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1989;14(1-2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada M. Social object play among young Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) in Arashiyama, Japan. Primates. 2006;47(4):342–349. doi: 10.1007/s10329-006-0187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shutt K, MacLarnon A, Heistermann M, Semple S. Grooming in Barbary macaques: Better to give than to receive? Biol Lett. 2007;3(3):231–233. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masserman JH, Wechkin S, Terris W. “Altruistic” behavior in rhesus monkeys. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;121:584–585. doi: 10.1176/ajp.121.6.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller RE, Banks JH, Jr, Kuwahara H. The communication of affects in monkeys: Cooperative reward conditioning. J Genet Psychol. 1966;108(1st Half):121–134. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1966.9914438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Waal FBM, Ferrari PF. Towards a bottom-up perspective on animal and human cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14(5):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Waal FB. Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59(1):279–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panksepp J, Panksepp JB. Toward a cross-species understanding of empathy. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(8):489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decety J, Jackson PL. A social-neuroscience perspective on empathy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(2):54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decety J, Svetlova M. Putting together phylogenetic and ontogenetic perspectives on empathy. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2012;2(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Liencres C, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Brüne M. Towards a neuroscience of empathy: Pntogeny, phylogeny, brain mechanisms, context and psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1537–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans R, Ferguson E. Defining and measuring blood donor altruism: A theoretical approach from biology, economics and psychology. Vox Sang. 2014;106(2):118–126. doi: 10.1111/vox.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Waal FB, Leimgruber K, Greenberg AR. Giving is self-rewarding for monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(36):13685–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807060105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson PL, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. How do we perceive the pain of others? A window into the neural processes involved in empathy. Neuroimage. 2005;24(3):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallese V. Before and below ‘theory of mind’: Embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362(1480):659–669. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niedenthal PM, Barsalou LW, Winkielman P, Krauth-Gruber S, Ric F. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2005;9(3):184–211. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aarts E, Verhage M, Veenvliet JV, Dolan CV, van der Sluis S. A solution to dependency: Using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(4):491–496. doi: 10.1038/nn.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paukner A, Anderson JR, Borelli E, Visalberghi E, Ferrari PF. Macaques (Macaca nemestrina) recognize when they are being imitated. Biol Lett. 2005;1(2):219–222. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paukner A, Suomi SJ, Visalberghi E, Ferrari PF. Capuchin monkeys display affiliation toward humans who imitate them. Science. 2009;325(5942):880–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1176269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandel A, Helokunnas S, Pihko E, Hari R. Brain responds to another person’s eye blinks in a natural setting—The more empathetic the viewer the stronger the responses. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;42(8):2508–2514. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballesta S, Reymond G, Pozzobon M, Duhamel J-R. A real-time 3D video tracking system for monitoring primate groups. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;234:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massen JJM, Luyten IJAF, Spruijt BM, Sterck EHM. Benefiting friends or dominants: Prosocial choices mainly depend on rank position in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Primates. 2011;52(3):237–247. doi: 10.1007/s10329-011-0244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massen JJM, van den Berg LM, Spruijt BM, Sterck EHM. Generous leaders and selfish underdogs: Pro-sociality in despotic macaques. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang SWC, Winecoff AA, Platt ML. Vicarious reinforcement in rhesus macaques (macaca mulatta) Front Neurosci. 2011;5:27. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterck EHM, Olesen CU, Massen JJM. No costly prosociality among related long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) J Comp Psychol Wash DC. 2015;129(3):275–282. doi: 10.1037/a0039180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horner V, Carter JD, Suchak M, de Waal FBM. Spontaneous prosocial choice by chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(33):13847–13851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burkart JM, Fehr E, Efferson C, van Schaik CP. Other-regarding preferences in a non-human primate: Common marmosets provision food altruistically. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(50):19762–19766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710310104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claidière N, et al. Selective and contagious prosocial resource donation in capuchin monkeys, chimpanzees and humans. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7631. doi: 10.1038/srep07631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drayton LA, Santos LR. Insights into Intraspecies Variation in Primate Prosocial Behavior: Capuchins (Cebus apella) Fail to Show Prosociality on a Touchscreen Task. Behav Sci (Basel) 2014;4(2):87–101. doi: 10.3390/bs4020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massen JJM, Van Den Berg LM, Spruijt BM, Sterck EHM. Inequity aversion in relation to effort and relationship quality in long-tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Am J Primatol. 2012;74(2):145–156. doi: 10.1002/ajp.21014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aknin LB, Hamlin JK, Dunn EW. Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preston SD. The origins of altruism in offspring care. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(6):1305–1341. doi: 10.1037/a0031755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dubuc C, Hughes KD, Cascio J, Santos LR. Social tolerance in a despotic primate: Co-feeding between consortship partners in rhesus macaques. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2012;148(1):73–80. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabbatini G, De Bortoli Vizioli A, Visalberghi E, Schino G. Food transfers in capuchin monkeys: An experiment on partner choice. Biol Lett. 2012;8(5):757–759. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomsen CE. Eye contact by non-human primates toward a human observer. Anim Behav. 1974;22(1):144–149. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emery NJ. The eyes have it: The neuroethology, function and evolution of social gaze. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(6):581–604. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bard KA, et al. Group differences in the mutual gaze of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Dev Psychol. 2005;41(4):616–624. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coss RG, Marks S, Ramakrishnan U. Early environment shapes the development of gaze aversion by wild bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata) Primates. 2002;43(3):217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02629649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leonard TK, Blumenthal G, Gothard KM, Hoffman KL. How macaques view familiarity and gaze in conspecific faces. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126(6):781–791. doi: 10.1037/a0030348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosher CP, Zimmerman PE, Gothard KM. Videos of conspecifics elicit interactive looking patterns and facial expressions in monkeys. Behav Neurosci. 2011;125(4):639–652. doi: 10.1037/a0024264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrari PF, Paukner A, Ionica C, Suomi SJ. Reciprocal face-to-face communication between rhesus macaque mothers and their newborn infants. Curr Biol. 2009;19(20):1768–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sommer W, Stürmer B, Shmuilovich O, Martin-Loeches M, Schacht A. How about lunch? Consequences of the meal context on cognition and emotion. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hare B, Kwetuenda S. Bonobos voluntarily share their own food with others. Curr Biol. 2010;20(5):R230–R231. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Waal FBM. The antiquity of empathy. Science. 2012;336(6083):874–876. doi: 10.1126/science.1220999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atsak P, et al. Experience modulates vicarious freezing in rats: A model for empathy. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palagi E, Leone A, Mancini G, Ferrari PF. Contagious yawning in gelada baboons as a possible expression of empathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(46):19262–19267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910891106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romero T, Konno A, Hasegawa T. Familiarity bias and physiological responses in contagious yawning by dogs support link to empathy. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis M, Antoniadis EA, Amaral DG, Winslow JT. Acoustic startle reflex in rhesus monkeys: A review. Rev Neurosci. 2008;19(2-3):171–185. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2008.19.2-3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S. Startle modulation by affective faces. Biol Psychol. 2010;83(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cords M. Post-conflict reunions and reconciliation in long-tailed macaques. Anim Behav. 1992;44(1):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Widdig A, Streich WJ, Tembrock G. Coalition formation among male Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) Am J Primatol. 2000;50(1):37–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(200001)50:1<37::AID-AJP4>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fruteau C, Voelkl B, van Damme E, Noë R. Supply and demand determine the market value of food providers in wild vervet monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(29):12007–12012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss A, King JE, Murray L. Personality and Temperament in Nonhuman Primates. Springer; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Marco A, Cozzolino R, Dessì-Fulgheri F, Thierry B. Collective arousal when reuniting after temporary separation in Tonkean macaques. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;146(3):457–464. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Marco A, Sanna A, Cozzolino R, Thierry B. The function of greetings in male Tonkean macaques. Am J Primatol. 2014;76(10):989–998. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehmann J, Korstjens AH, Dunbar RIM. Group size, grooming and social cohesion in primates. Anim Behav. 2007;74(6):1617–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishikawa M, Suzuki M, Sprague DS. Activity and social factors affect cohesion among individuals in female Japanese macaques: A simultaneous focal-follow study. Am J Primatol. 2014;76(7):694–703. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kazahari N. Maintaining social cohesion is a more important determinant of patch residence time than maximizing food intake rate in a group-living primate, Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) primates. J Primatol. 2014;55(2):179–184. doi: 10.1007/s10329-014-0410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sugiura H, Shimooka Y, Tsuji Y. Japanese macaques depend not only on neighbors but also on more distant members for group cohesion. Ethology. 2014;120(1):21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 69.McFarland R, Majolo B. Coping with the cold: Predictors of survival in wild Barbary macaques, Macaca sylvanus. Biol Lett. 2013;9(4):20130428. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hays A, Richmond B, Optican L. 1982. Unix-Based Multiple-Process System, for Real-Time Data Acquisition and Control (Electron Conventions, El Segundo, CA)

- 71.Ballesta S, Reymond G, Pozzobon M, Duhamel J-R. Compete to play: Trade-off with social contact in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Varley M, Symmes D. The hierarchy of dominance in a group of macaques. Behaviour. 1966;27(1):54–75. doi: 10.1163/156853966x00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chamove AS. Role or dominance in macaque response to novel objects. Motiv Emot. 1983;7(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]