Significance

Immunized animals are a key source of monoclonal antibodies used to treat human diseases. Before clinical use, animal antibodies are typically “humanized” by laborious and suboptimal methods that transfer their full target binding loops (a.k.a. CDRs) into human frameworks. We report an optimal method, where the CDRs from species such as rodents and chickens can be adapted to fit human frameworks in which we have clinical and manufacturing confidence. The Augmented Binary Substitution (ABS) process exploits the fundamental plasticity of antibody CDRs to ultrahumanize antibodies from key species in a single pass. ABS results in a final antibody that is much closer to human germ line in the frameworks and CDRs, minimizing immunogenicity risks in man and maximizing the therapeutic potential of the antibody.

Keywords: antibody, paratope, plasticity, humanization, immunogenicity

Abstract

Although humanized antibodies have been highly successful in the clinic, all current humanization techniques have potential limitations, such as: reliance on rodent hosts, immunogenicity due to high non-germ-line amino acid content, v-domain destabilization, expression and formulation issues. This study presents a technology that generates stable, soluble, ultrahumanized antibodies via single-step complementarity-determining region (CDR) germ-lining. For three antibodies from three separate key immune host species, binary substitution CDR cassettes were inserted into preferred human frameworks to form libraries in which only the parental or human germ-line destination residue was encoded at each position. The CDR-H3 in each case was also augmented with 1 ± 1 random substitution per clone. Each library was then screened for clones with restored antigen binding capacity. Lead ultrahumanized clones demonstrated high stability, with affinity and specificity equivalent to, or better than, the parental IgG. Critically, this was mainly achieved on germ-line frameworks by simultaneously subtracting up to 19 redundant non-germ-line residues in the CDRs. This process significantly lowered non-germ-line sequence content, minimized immunogenicity risk in the final molecules and provided a heat map for the essential non-germ-line CDR residue content of each antibody. The ABS technology therefore fully optimizes the clinical potential of antibodies from rodents and alternative immune hosts, rendering them indistinguishable from fully human in a simple, single-pass process.

Monoclonal antibodies are a highly established technology in drug development and the majority of currently approved therapeutic antibodies are derived from immunized rodents (1). The advent of display libraries and engineered animals that can produce “fully human” antibody v-gene sequences has had a significant positive impact on antibody drug discovery success (1), but these technologies are mostly the domain of biopharmaceutical companies. Antibodies from wild-type animals that are already extant, or can be freely developed, will therefore continue to be a rich source of therapeutic candidates. In addition, phylogenetically distant hosts such as rabbits and chickens may become a valuable source of monoclonals with clinical potential against challenging targets (2, 3).

Chimerization of murine antibodies can reduce anti-IgG responses in man (4), but murine v-domains may still have provocative T-cell epitope content, necessitating “humanization” of their framework regions (5, 6). Classical humanization “grafts” murine CDRs into human v-gene sequences (7), but this typically leads to significant reduction in affinity for target, so murine residues are introduced at key positions in the frameworks (a.k.a. “back-mutations”), to restore function (8). Importantly, humanized antibodies do elicit lower immunogenicity rates in patients in comparison with chimerics (9).

Alternative humanization methods have also been developed based on rational design or empirical selection (10–17), but current methods still all suffer from flaws, such as: high non-germ-line amino acid content retention (5, 6); grafting into poorly understood frameworks (13); resource-intensive, iterative methods (15, 18); requirement for homology modeling of the v-domains, which is often inaccurate (19, 20), or a cocrystal structure with the target antigen (14). Methods that allow humanization into preferred frameworks can add numerous framework mutations (18, 21), which may destabilize the v-domains (22), encode new T-cell epitopes, or introduce random amino acid mutations in CDRs (12, 13) that can drive polyspecificity and/or poor PK properties (23).

Critically, testing of protein therapeutics in monkeys has been shown to be nonpredictive of immune responses in man (24) and animal immunogenicity testing has been suggested to be of little value in biosimilar development (25). Current evidence suggests that the main risk factors for antibody immunogenicity in man are human T-cell epitope content and, to a lesser extent, T-cell independent B-cell responses (6). B-cell epitopes are challenging to predict and B-cell-only responses to biotherapeutics appear to be driven by protein aggregates (26). The key attributes to reduce antibody immunogenicity risk in the clinic appear to be: low T-cell epitope content, minimized non-germ-line amino acid content and low aggregation potential (27).

In recent years, several reports have strongly suggested that CDRs might be malleable in ways that could not be predicted a priori. Random mutagenesis and reselection of a classically humanized rat antibody found that individual framework back mutations and CDR residues could revert to human germ-line sequence, while maintaining or even improving the function of the antibody (28). A number of humanization studies have now also shown that a small number of positions in the CDRs could be substituted for human germ-line residues, through a rational design cycle of reversion mutations (5, 29). In addition to these observations, a number of structural analyses have illustrated the common redundancy of sequence space in antibody binding interfaces. Despite typically large buried interfaces between antibodies and protein targets, only a subset of residues in the CDRs of antibodies usually makes contact with antigen (30–32). Alanine scanning of CDR loops has also shown that only a limited number of residues directly affect antigen binding affinity (33). Indeed, it has even been shown that redundant paratope space in a single antibody may be exploited to engineer binding specificity to two separate targets (34). Additionally, CDR loop structures are known to be restricted to a limited number of canonical classes, despite amino acid variation within those classes at specific positions (35–38). These observations led us to hypothesize that, under the right experimental conditions, a large proportion of residues in grafted animal CDRs could be concurrently replaced by the residues found at the corresponding positions in a given destination human germ-line v-gene.

In this study, we generated combinatorial libraries on the basis of a design principle we have named “Augmented Binary Substitution” (ABS). Each library was based on a single starting antibody: rat anti-RAGE (28), rabbit anti-A33 (2), and chicken anti-pTau (3). These libraries were built into human germ-line frameworks of high predicted stability and solubility, then interrogated via phage display and screened to identify lead clones with epitope specificity and affinity equivalent to the parental clone. ABS proved to be a facile, rapid method that retains only the functionally required CDR content of the parental animal antibody, without the need for prior crystal-structure insight. Notably, this CDR germ-lining approach generated highly stable and soluble human IgGs, from multiple key antibody discovery species, that have minimized predicted human T-cell epitope content. The reproducibility of these findings across three antibodies from three disparate species demonstrates a fundamental plasticity in antibody paratopes that can be broadly exploited in therapeutic antibody optimization.

Results

Library Design, Build, and Characterization.

Rat anti-RAGE XT-M4 (28), rabbit anti-A33 (2), and chicken anti-pTau pT231/pS235_1 (3) IgGs were generated on the human IgG1 backbone with either parental (Par-RAGE, Par-A33, or Par-pTau), grafted (Graft-RAGE, Graft-A33, or Graft-pTau), or classically humanized (CL-Hum-RAGE, CL-Hum-A33) v-domains. In scFv format, the parental form of each of these antibodies retained antigen binding, whereas the human FW-grafted versions demonstrated little to no binding (Fig. S1 A–C). ABS ultrahumanization libraries (ABS-RAGE, ABS-A33, ABS-pTau) were constructed (Fig. 1) to generate 1.8 × 109 independent clones for ABS-RAGE, 1.1 × 1010 for ABS-A33, and 4.9 × 109 for ABS-pTau (theoretical binary diversity for ABS-RAGE is 227 positions = 1.34 × 108, for ABS-A33 232 = 4.29 × 109, and for ABS-pTau 233 = 8.59 × 109). Library build quality was verified by sequencing ≥96 clones/library (Fig. S2). Libraries were rescued using helper phage M13 and selections performed on their cognate targets.

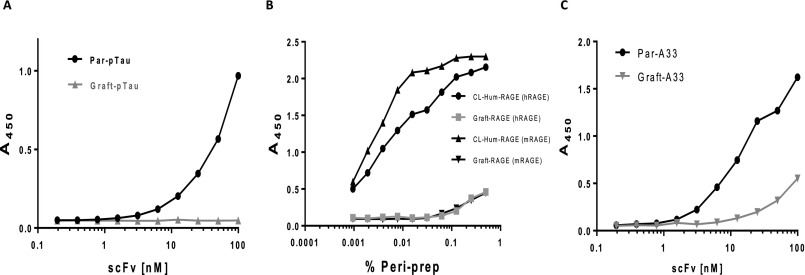

Fig. S1.

ELISA analyses of scFv function after expression in E. coli from phagemid vector pWRIL-1. Binding signals in titration ELISA against: (A) pT231_pS235 peptide for purified VL-VH scFv forms of Par-pTau and Graft-pTau. (B) hRAGE and mRAGE for periplasmic preparation (% Peri-prep) VL-VH scFv forms of CL-Hum-RAGE and Graft-RAGE. (C) Human A33 ectodomain protein for purified VL-VH scFv forms of Par-A33 and Graft-A33. In all cases the grafted scFvs showed significantly impaired binding activity.

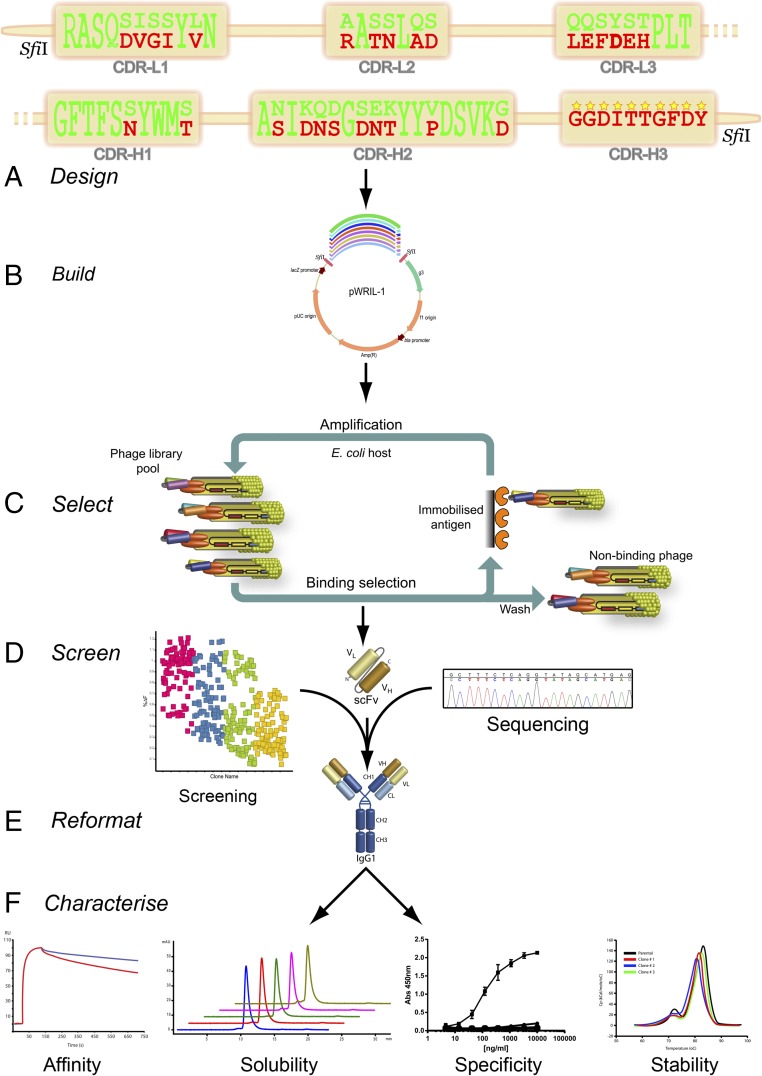

Fig. 1.

Schematic of ABS library design, selection and screening principles. (A) Amino acid sequences are shown for the v-domains of Par-RAGE and destination germ-line (DPK9-DP54) scFvs in VL-VH format. Rat parental antibody-specific residues are highlighted in red, and human germ-line-matching residues are highlighted in green. At each position where the rat and human residues differed, both residues were encoded for in the ABS-RAGE library. This principle was applied to all CDRs other than the CDR-H3, in a single combinatorial library. In the CDR-H3, point mutations were permitted at a frequency of 1 ± 1 per clone. (B and C) Phage libraries were generated (B) and used in selections on cognate antigen (C). (D) Selection output clones were subsequently screened by ELISA, HTRF, and DNA sequencing to identify hits with maintained target binding and epitope specificity. (E and F) Top clones were expressed and purified as IgGs (E), before characterization of affinity by Biacore, solubility and aggregation analyses by SEC, in vitro specificity by ELISA and Biacore, and thermal stability analysis by DSC (F).

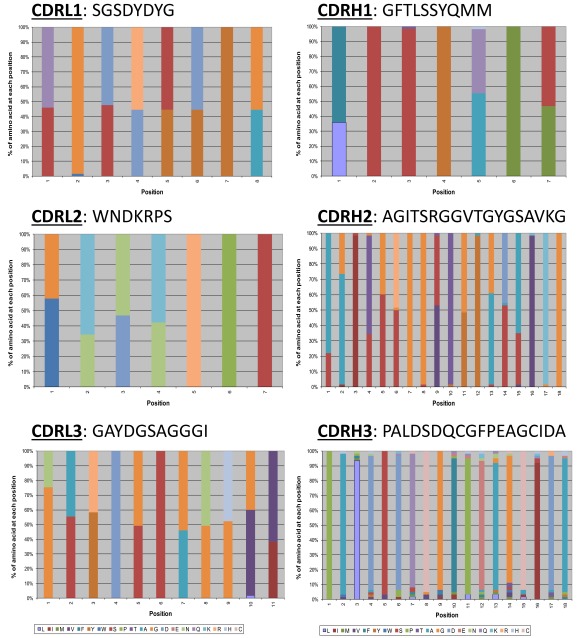

Fig. S2.

Sequence analyses of pTau library build quality. After library transformation, the full scFv insert sequences were obtained for 96 clones, via Sanger sequencing. Positions mutated in the CDRs show the expected (∼50:50) variability at all positions expected to be sampled by binary substitutions and low-level mutagenesis in the CDR-H3, confirming the integrity of the sampled library. <1% of clones contained out of frame or truncated inserts.

Identification and Analysis of Ultrahumanized clones.

Postselection screening (Fig. S3 A and B) and DNA sequencing revealed the presence of numerous scFv clones with significantly increased human content within the CDRs. In the ABS-RAGE and ABS-A33 leads, the FW sequences remained fully germ line. In the ABS-pTau leads (n = 188), all selected clones retained the T46 back-mutation (Kabat numbering used throughout), illustrating that this VL-FW2 residue is essential to humanize chicken antibodies (Fig. S4). From each screen, ABS lead clones were ranked on the basis of HTRF signal vs. level of CDR germ-lining. The top 10 clones from each ranking were then subcloned into IgG expression vectors for further testing as below. Human germ-line amino acid content was quantified within the CDRs of parental antibodies and ABS leads and expressed as a percentage (Table S1). Human content had raised 17–29% in each case. In expression in HEK-293expi cells after transfection with IgG expression plasmids and expifectamine, all IgGs studies (ABS-derived leads and controls) produced >15 mg/L of purified IgG, with the exception of Graft-A33, which could not be expressed.

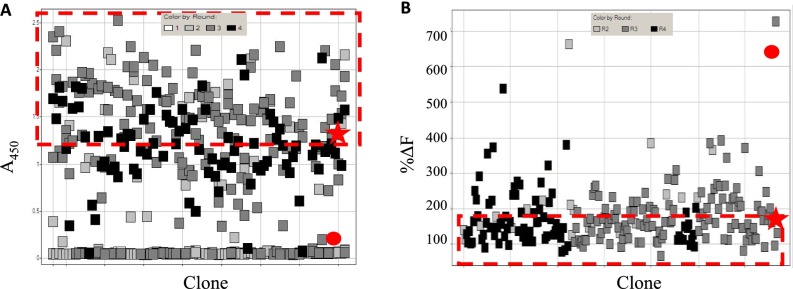

Fig. S3.

Clone selection in ABS library screening – pTau example. (A) Periprep ELISA screening of single clones picked from multiple rounds of phage display selections of the ABS-pTau library. One hundred and eighty-eight clones were prioritized (highlighted in red dashed box) on the basis of retention of binding to the pT231_pS253 phosphopeptide, with A450 readings above the negative control (Anti-RAGE scFv •) and equivalent to or above that of Par-pTau scFv (*). (B) Periprep HTRF screening of single clones picked from B. Clones were prioritized (highlighted in red dashed box) on the basis of neutralization of Par-pTau IgG binding to the pT231_pS253 phosphopeptide, with %ΔF readings lower than the negative control (Anti-RAGE scFv •) and equivalent to or better than Par-pTau scFv (*).

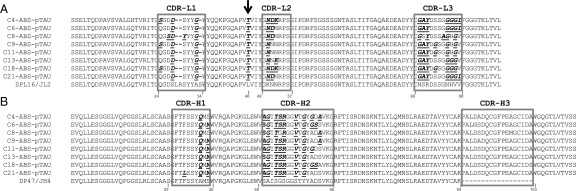

Fig. S4.

Sequence alignments for VL (A) and VH (B) domains of eight prioritized lead clones from the ABS-pTau library. CDR regions are boxed in gray. Amino acids differing from the human DPL16/JL2 and DP47/JH4 germ lines are bold and underlined. Black arrow indicates the position of the L46T mutation positively selected in the FW2 of all clones showing functional binding to target. Kabat numbering scheme.

Table S1.

CDR sequence, affinity, and stability characteristics of parental, grafted, and ABS-derived lead clones

| CDRL1* | CDRL2 | CDRL3 | CDRH1 | CDRH2 | CDRH3 | % germ line in CDRs | No. of FW mutations | IC50 (nM) HTRF | kDa (nM) SPR | % Agg 60 °C | Tm (°C) | % Loss in pH shock | |

| DPK9/DP54 | RASQSISSYLN | AASSLQS | QQSYSTPLT | GFTFSSYWMS | ANIKQDGSEKYYVDSVKG | n/a | 100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| CL-Hum-RAGE | RASQDVGIYVN | RATNLAD | LEFDEHPLT | GFTFSNYWMT | ASIDNSGDNTYYPDSVKD | GGDITTGFDY | 45 | 5 | 10.3 | 31.0 | 14 | 77 | 4.8 |

| Graft-RAGE | RASQDVGIYVN | RATNLAD | LEFDEHPLT | GFTFSNYWMT | ASIDNSGDNTYYPDSVKD | GGDITTGFDY | 45 | 0 | >61.9 | ND | 0 | 84 | 1.0 |

| C7-ABS-RAGE | RASQSIGSYLN | RASSLAS | LEFDEHPLT | GFTFSSYWMS | ASIDQDGSNKYYPDSVKG | GGDITTGLDY | 74 | 0 | 5.8 | 17.0 | 2 | 85 | 2.3 |

| DPK9/DP47 | RASQSISSYLN | AASSLQS | QQSYS–TPLT | GFTFSSYAMS | SAISGSGGSTYYADSVKG | n/a | 100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Par-A33 | LASEFLFNGVS | GASNLES | LGGYSGSSGLT | GIDFSHYGIS | AYIYPNYGSVDYASWVNG | DRGYYSGSRGTRLDL | 39 | n/a | 2.9 | 2.1 | 7 | 74 | 1.4 |

| Graft-A33 | LASEFLFNGVS | GASNLES | LGGYSGSSGLT | GIDFSHYGIS | SYIYPNYGSVDYASWVNG | DRGYYSGSRGTRLDL | 39 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C6-ABS-A33 | RASQFLFNGVS | AASNLES | QGGYSGSTGLT | GFTFSHYGIS | SYIYPSYGSTDYASSVKG | DRGYYSGSRGTRLDL | 56 | 0 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 8 | 74 | 0.5 |

| DPL16/DP47 | QGDSLRSYYAS | GKNNRPS | NSRDSSGNHVV | GFTFSSYAMS | SAISGSGGSTYYADSVKG | n/a | 100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Par-pTau | SGSD–YDYG- | WNDKRPS | GAYDGSAGGGI | GFTLSSYQMM | AGITSRGGVTGYGSAVKG | PALDSDQCGFPEAGCIDA | 41 | n/a | 1.6 | 0.41 | 17 | 70 | 1.2 |

| Graft-ABS-pTau | SGSD–YDYG- | WNDKRPS | GAYDGSAGGGI | GFTLSSYQMM | AGITSRGGVTGYGSAVKG | PALDSDQCGFPEAGCIDA | 41 | 0 | >64.7 | NB | 90 | 66 | 0.8 |

| C21-ABS-pTau | QGDD–SYYG- | GNDNRPS | GAYDSSGGGGI | GFTLSSYQMM | AGITGRGGVTGYADSVKG | PALDSDQCGFPEAGCIDA | 65 | 1 | 2.1 | 0.25 | 3 | 70 | 1.4 |

| Com-ABS-pTau | QGDD–SYYG- | GNNNRPS | GSYDSSGGHGV | GFTFSSYQMS | SGITGRGGVTGYADSVKG | PALDSDQCGFPEMGCIDA | 76 | 1 | ND | 0.50 | 2 | 71 | 0.8 |

The pTau CDR-L1 is shorter than its DPL16 counterpart by 3 amino acids. Sequence dashes in this CDR are added to show the spacing of sampled residues, based on sequence alignment. Residues differing from human germ line are underlined. CDR definitions used in this manuscript are an expanded definition in comparison with the classical Kabat, including VH positions 26–29 and 49.

Lead IgG Affinity, Stability, and Specificity Characteristics.

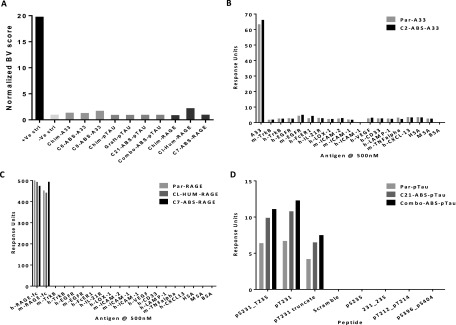

ABS leads in human IgG1 format were analyzed for specificity and stability. HTRF data (Fig. S5 A–C), showed that the lead ABS-derived IgGs had successfully maintained full epitope competition with their respective parental clones (Table S1). Biacore analyses showed approximately twofold affinity improvements for C7-ABS-RAGE and C21-ABS-pTau over Par-RAGE and Par-pTau, respectively, whereas C6-ABS-A33 maintained equivalent affinity to Par-A33 (Table S1).

Fig. S5.

IgG titration HTRF data for representative lead ABS-derived clones. (A) Anti-RAGE clones. (B) Anti-pTau clones. (C) Anti-A33 clones (-ve control non-A33-specific IgG added instead of graft due to graft expression problems). Grafted clones (where available) showed significant reductions in neutralization capacity, whereas the ABS-derived leads recapitulated the binding and competition rates of the parental clones.

A baculovirus ELISA (Fig. S6A) where binding is a risk indicator for poor pK in vivo (39) showed no reactivity for any of the RAGE, A33, or pTau clones in comparison with an internal positive control (40). High-sensitivity Biacore assays were also established, to examine the possibility that v-gene engineering might lead to low-affinity interactions with multiple classes of proteins. A panel of 18 nontarget proteins showed that C7-ABS-RAGE and C6-ABS-A33 both maintained highly specific binding to their respective antigens (Fig. S6 B and C). For the anti-pTau antibodies, specificity for pT231/pS235 was confirmed using previously described Biacore assays (3) (Fig. S6D). All ABS-derived leads in this study were, therefore, absent of the “charge asymmetry,” lipophilicity, off-target protein binding, or other problems that can arise during v-gene engineering (39, 41–43).

Fig. S6.

IgG specificity testing. Parental and lead clones were examined in: baculovirus-based ELISA for off-target binding and clearance risk (A), high sensitivity Biacore binding assay against cognate target and purified proteins of multiple structural classes (B and C), and Biacore binding assay against pS231_T235 -derived cognate phosphopeptides, scrambled pS231_T235 peptide and irrelevant phosphopeptides from other regions of pTau (D). No off-target binding is observed in any assay for the parental clones or their ABS-derived leads.

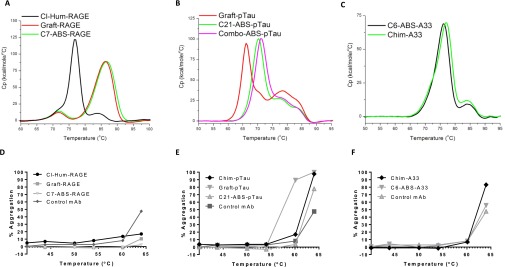

DSC analysis of IgG thermal stabilities demonstrated that C7-ABS-RAGE, C6-ABS-A33, and C21-ABS-pTau were highly stable. C7-ABS-RAGE was particularly thermostable with a Fab Tm of 85 °C; similar to Graft-RAGE, but almost 8 °C higher than that of the CL-Hum-RAGE (Fig. S7A and Table S1). This is a finding of note, as it highlighted that the presence of back-mutations in CL-Hum-RAGE had significantly decreased the stability of the v-domains in comparison with the highly stable graft. C21-ABS-pTau exhibited a Fab Tm of 70 °C, 4 °C higher than Graft-pTau (Fig. S7B). C6-ABS-A33 exhibited a Fab Tm of 74 °C, identical to Chim-A33 (Table S1), but could not be compared with Graft-A33, which could not be expressed at usable levels in our hands (Fig. S7C). In forced aggregation analyses, C7-ABS-RAGE, C21-ABS-pTau, and C6-ABS-A33 all showed <10% aggregation at 60 °C (Fig. S7 D, E, F, Table S1). Graft-pTau, in contrast, exhibited >90% aggregation at 60 °C. Importantly, analysis of pH shock tolerance (which mimics virus-killing pH hold in mAb manufacturing) also showed each of the IgGs to be highly stable, with <3% loss observed (Table S1).

Fig. S7.

Biophysical analyses for ABS-derived clones. Differential Scanning Calorimetry analysis of IgG thermal stability for anti-RAGE (A), anti-pTau (B) and anti-A33 (C) antibodies. Forced IgG aggregation analysis for anti-RAGE (D), anti-pTau (E), and anti-A33 (F) antibodies in comparison with a control antibody of known high stability (55).

Human T-Cell Epitope Minimization in ABS Leads.

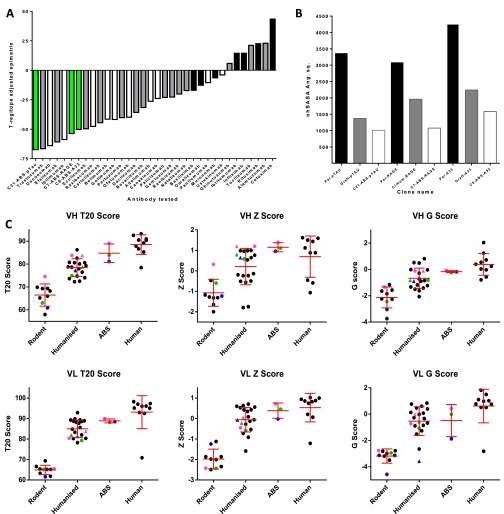

ABS leads and associated precursors were examined for potential T-cell epitope content, as suggested in the recent FDA immunogenicity assessment guidelines (44), using the EpiMatrix software (6) for each clone (Fig. S8A). C7-ABS-RAGE, C6-ABS-A33 and C21-ABS-pTau showed scores of −53.72, −50.22, and −67.33 points, respectively. ABS lowered the projected immunogenicity of all clones into the same range as antibodies such as trastuzumab and lower than fully human antibodies such as adalimumab (Fig. S8A). Analysis at the individual peptide level predicted that T-cell epitope content was clearly reduced for all ABS leads in comparison with their respective parental forms (Fig. S9). Indeed, the removal of the back mutation found in the VL FW2 of CL-Hum-RAGE not only aided stabilization of the v-domains (Fig. S7A), but also removed a predicted T-cell epitope (Fig. S9). Analysis of the sequence of C21-ABS-pTau and C6-ABS-A33 showed that the ABS-derived germ-lining at key positions in multiple CDRs had ablated foreign T-cell epitopes including some that had been introduced by CDR-grafting. However, some potential foreign epitopes were still present, even after ultrahumanization (Fig. S9). This finding reflects the need to retain certain key contact residues in the paratope and balance target recognition with T-cell epitopes and overall “humanness.” The L46T back mutation in C21-ABS-pTau was not predicted to introduce a T-cell epitope and this clone retained only a single predicted foreign T-cell epitope.

Fig. S8.

Assessment of potential immunogenicity in the v-domains of ABS-derived leads. (A) EpiMatrix was used to estimate the potential for T-cell epitope driven immunogenicity in the v-domains of C21-ABS-pTau, C6-ABS-A33 and C7-ABS-RAGE (all green) in comparison with 31 FDA-approved therapeutic antibodies that are rodent (black), humanized (gray) or fully human (white) in sequence. Lower score suggests lower predicted immunogenicity. (B) Comparison of nhSASA (Å2) that contributed to the v-domains of parental (black), grafted (gray) and ABS (white) clones for pTau, A33 and RAGE. Although CDR grafting dramatically lowers the nhSASA score in all cases, the ABS lead clones all exhibit minimized exposure of non-germ-line amino acid motifs. (C) Publically available, online tools which estimate levels of v-gene sequence identity to the human v-domain repertoire were used to calculate T20, Z, and G scores for 31 approved therapeutic antibodies that are rodent, humanized or fully human in origin, plus the parental, graft (triangles) and ABS leads for pTau (blue), RAGE (pink) and A33 (green).

Fig. S9.

In silico predictions for T-cell epitopes within the full VH and VL regions of lead clones were performed with EpiMatrix (Epivax, RI). Possible epitopes are defined as 9-mer sequences with four or more hits and are colored based on potential epitopes different to human germ line, and potential epitopes in germ-line sequence to which most patients should exhibit self-tolerance. Coloring scheme: Underlined, CDRs; yellow, predicted epitopes in the germ line that should be tolerized; red, foreign T epitopes. C7-ABS-RAGE has the lowest immunogenicity potential of the anti-RAGE clones as it contains 2 potential T-cell epitopes, in comparison with 10 potential T-cell epitopes in Par-RAGE. Similarly, C21-ABS-pTau has the lowest immunogenicity potential of the anti-pTau clones as it contains only 1 potential t-cell epitope in comparison with 5 potential T-cell epitopes in Par-pTau. Despite leading to a significant increase in the % human germ-line content in the CDRs over C21-ABS-pTau, Combo-ABS-pTau introduced a further potential epitope. Finally, C6-ABS-A33 has the lowest immunogenicity potential of the anti-A33 clones as it contains 2 potential T-cell epitopes, in comparison with 10 potential T-cell epitopes in Par-A33.

It has previously been argued that another major determinant of antibody immunogenicity is likely to be the amount of non-germ-line surface residue exposure found on the v-domains (45). To assess non-germ-line surface availability, nonhuman solvent-accessible surface area (nhSASA, measured in Å2) was calculated for the parental, graft and ABS lead clones. All ABS leads demonstrated minimized nhSASA (Fig. S8B). Notably, C7-ABS-RAGE exhibited a nhSASA of 1,077.6 Å2, in comparison with the Par-RAGE and Graft-RAGE at 3,084.8 and 1,957.6, respectively, which represents a 45% reduction even in comparison with the Graft-RAGE, where the CDRs are the only source of non-germ-line surface residues.

Further analyses were performed using publically available software to numerically define the human repertoire similarity of the parental and ABS-derived leads, in comparison with 31 antibodies currently approved as therapeutics with murine, humanized or fully human v-domains. These analyses showed that the ABS clones had distinctly improved T20 (46), G (47), and Z (48) scores over parental clones. Indeed, ABS lead clones had scores placing generally in the range of values found for the fully human antibody group (Fig. S8C).

Essential Non-Germ-Line CDR Content Definition via Mutational Tolerance and Structural Analyses.

The screening of output clones from the ABS-pTau library identified 188 sequence-unique hits with binding signals ≥ the parental scFv (Fig. S3A). For residues targeted in the library for binary substitution, positional amino acid retention frequencies were calculated for these hits and expressed as a percentage (Fig. S10 A and B). Amino acid positions with parental residue retention frequencies of >75% were labeled “strongly maintained” (SM), i.e., with the chicken residue being positively selected. Those with frequencies below 25% were labeled “strongly deleted” (SD), i.e., the human germ-line residue being preferred.

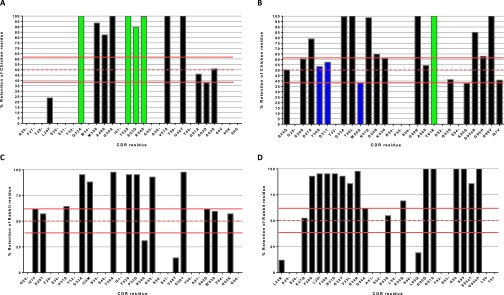

Fig. S10.

CDR redundancy definition in anti-pTau via mutational tolerance analysis of non-germ-line amino acid retention. A plot of chicken and rabbit amino acid retention frequencies in the CDRs of the ELISA-positive population of unique clones from library screening is shown for ABS-pTau VH (A), ABS-pTau VL (B), ABS-A33 VH (C), and ABS-A33 VL (D) domains, respectively. Only those residues targeted for binary substitution are plotted. Residues predicted to be making antigen contacts in a cocrystal structural analysis of the anti-pTau antibody that were also SM are highlighted with green bars. Predicted contact residues not found to be SM are highlighted in blue bars. CDR residues noted on the X-axis whose values are set at 0 were identical human-chicken/rabbit and not sampled in the library, but are included in the figure for clarity (e.g., G26-, etc.). In both plots the mean human-chicken/rabbit frequency (∼50%) in sequenced clones from the starting library is plotted as a dashed red line, with SDs as solid red lines. A single chicken residue (VH L29) and three rabbit residues (VH V58, VL L24 and L89) were all found to be SD.

When the SM residues were compared with those previously predicted to be key contacts via a cocrystal structure (3), the two populations were found to clearly overlap. Across both chains, however, SM positions were found to be only 29.6% (17 of 55) of the total CDR residues outside the CDR-H3. In the VH domain, Q33, T52, S53, R54 were all predicted contact residues and all were SM, with retention frequencies >90%. G55 and G56 were also predicted to be key contacts but were not sampled in the library, as they were fully conserved human to chicken. Interestingly, the S53G substitution, although not heavily favored in the selected population, could clearly be functional, as seen in the C21-ABS-pTau clone, so long as T52, R54, G55, and G56 were maintained (Fig. S4). Other SM residues in the VH were found to be contact-proximal and/or potentially critical for appropriate presentation of the contact residues, such as M35, A49, G50, V57, and G59. Of four predicted contact residues in the VL (3), only Y91 was found to be SM and was retained at 100%. Other SM residues were predominantly found in stem-loop positions of CDR-L3 (G89, G96, G98) and CDR-L1 (G34), which may be influential on loop structure (35). Additionally, the SM N51 site forms structurally supportive hydrogen bonds between the CDR-L1 and VL FW2 (3).

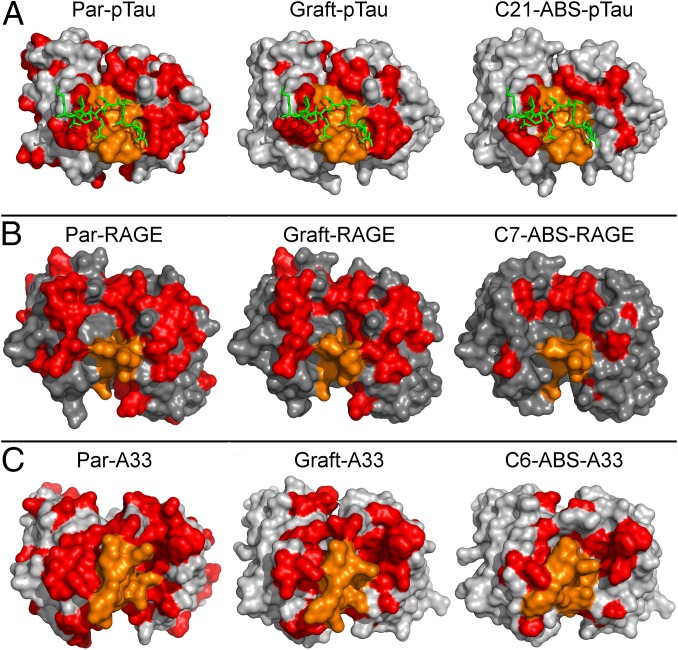

Out of 33 residues sampled by binary substitution, only a single SD residue (VH L29) was identified, suggesting that all 16 other non-SM residues were interchangeable. On the basis of these analyses, we identified the “essential non-germ-line CDR content,” meaning those essential parental residues that cannot be germ-lined, even if compensated by the mutation of a residue elsewhere in the paratope (Fig. 2 A–C). These findings also informed the minimization of chicken residue content by making a combination clone, Combo-ABS-pTau. This clone contains the most “human” variant of each CDR that had been observed in the top ABS-pTau hits (Fig. S4 and Table S1). This reduced non-germ-line content by another 6 residues versus C21-ABS-pTau, pushing the Combo-ABS-pTau to 76% human in the CDRs, but adding one more predicted T-cell epitope than C21-ABS-pTau (Fig. S9). The retained non-germ-line residues in Combo-ABS-pTau closely matched to the SM set of residues described above (Fig. S10 A and B). Combo-ABS-pTau was found to be soluble, stable and maintained the binding affinity and specificity of Par-pTau (Table S1 and Fig. S7B).

Fig. 2.

CDR germ-lining illustration via surface space-fill plots of non-germ-line amino acid retention. (A) Heatmap (based on cocrystal structure PDB 4GLR) of non-germ-line residue content in the anti-pTau binding site for Par-pTau, Graft-pTau and C21-ABS-pTau. Residues matching human DP47/DPL16 germ lines are shown (spacefill) in gray, non-germ-line residues in orange (CDR-H3) or red (all other CDRs). The target pTau phospho peptide is included in green, illustrating the predominant retention of surface-exposed residues involved in the functional paratope in clone C21-ABS-pTau. Although cocrystal structures for anti-RAGE (B) and anti-A33 (C) were not available, structural modeling showed that the ABS process clearly defines residues that may be essential for antigen-binding function.

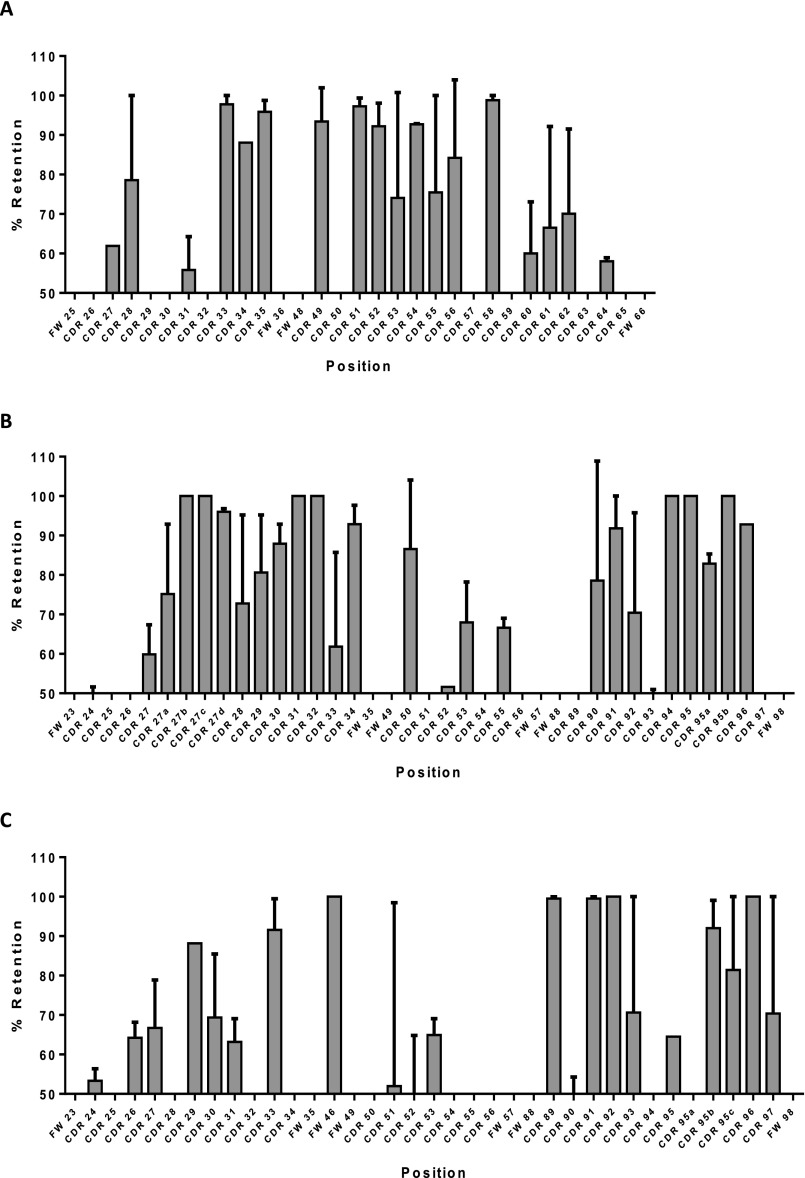

Similar data to that described above was found for ABS-A33 (Fig. S10 C and D). Furthermore, the combined analyses of retention frequencies in 5 separate ABS humanizations showed that some CDR loop regions known to have low potential to form contacts with antigen (32) were highly amenable to humanization. Residues 60–65 of the VH-CDR2, 24–27 of the VL-CDR1 in kappa and lambda chains, 89, 93, and 97 of the VK-CDR3 and multiple VL-CDR2 positions could frequently be germ-lined (Fig. S11 A–C). In the majority of positions sampled, however, no retention frequencies were observed that might allow prediction of humanization success a priori. Germ-lining of positions was not exclusively observed at positions where the amino acids were homologous, as also demonstrated in Table S1.

Fig. S11.

Combined ABS retention frequency plots for 5 anti-protein and anti-peptide antibodies, including ABS-RAGE, ABS-A33, ABS-pTau, and two others (Kabat numbering). Values plotted as mean ± SD per position. (A) VH retention frequency (n = 5). (B) VK retention frequencies (n = 3, rat, rabbit, mouse). (C) Vλ retention frequency (n = 2, both chicken), with L46T being retained in 100% of all hits.

Discussion

Despite considerable investigation, current antibody humanization methods often create therapeutic molecules with significant risk factors for the failure of a lead drug due to potential immunogenicity and/or poor pK in the clinic (6) or because the molecule cannot be manufactured and delivered in a cost-effective manner (49). These risks are potentially exacerbated if the lead is derived from hosts such as rats, rabbits, or chickens, rather than the heavily characterized antibody repertoires of mice and humans.

Antibodies from alternative immune species can provide excellent IgGs with unique functional characteristics against problematic targets (e.g., highly conserved across species), but their antibodies are also known to exhibit unique sequence/structural features (19). These antibodies require maximal humanization and development validation if they are to gain broad acceptance as potential clinical leads. Indeed, despite their therapeutic potential, there are currently no chicken antibodies and only one known humanized rabbit antibody in the clinic (50). In establishing the ABS technology we have shown that it is possible to minimize clinical and manufacturing concerns, by making antibodies from all three sources with excellent drug-like properties: highly expressed, biophysically stable, soluble, and of low immunogenicity risk.

When analyzed in silico, human identity and T-cell epitope risk appeared to be indivisible between C7-ABS-RAGE and currently marketed fully human antibodies, with C21-ABS-pTau and C6-ABS-A33 comparable to the best of the humanized mouse antibodies currently approved for clinical use. This finding is of key importance as it shows that the ABS process intrinsically minimizes the number of non-germ-line residues in the v-domains, reducing the potential for HLA class II peptide content that could drive the CD4+ T-cell help that is believed to be a key component of class-switched, high-affinity, anti-drug IgG responses (5).

The drive toward germ-line content in v-domains is underpinned by core theories of self-tolerance: Thymic tolerance in any given individual that defines “self” is dominated by the deletion of T cells recognizing self-antigens (5). Although individual antibody v-domain sequences often accrue significant deviations from germ line in the CDRs due to somatic hypermutation, those individual unique sequences are only likely to be tolerized in the individual which made the original B cell. The base set of 9-mer peptides that are common to, and likely to be tolerated by, all humans (excepting for allotypic differences), is therefore encoded for by the germ-line v-domain sequences that are expressed at high levels across many individuals (51). Importantly, this theory has been experimentally tested in mice, where CD4+ T cells in adult animals are unresponsive to mouse germ-line v-domains (51). It should be noted, however, that analysis of the predictive power of in silico T-cell epitope prediction has questioned its accuracy. This potential inaccuracy may be due to the observation that current prediction software is accurate at predicting the dominant DR-displayed peptides, but lacks accuracy in predicting DP and/or DQ alleles (52). These findings further support the rationale to drive the full v-domain sequence (inclusive of CDRs) as close as possible to human germ line, due to our inability to fully avoid false negatives in in silico epitope screening. Predictive power of immunogenicity analyses post-ABS could also be improved by performing in vitro antigen stimulation assays (52).

The use of preferred human germ-line frameworks is a critical element of the ABS technology, as this gives great confidence in the stability and solubility qualities of the resulting ultrahumanized lead antibodies. Other humanization methods do not factor in the CDRs themselves as mediators of stability and solubility, in addition to the frameworks. Antibodies from species with limited starting framework diversity in both the VH and VL genes fit the ABS technology particularly well. Indeed, chickens and rabbits use VH repertoires that are highly homologous to human VH3 domain (19). For murine antibodies, FW diversity in the functional repertoire is much higher than for chickens or rabbits (19). Prior estimations of v-domain homology, pairing angle, and VH-VL packing are therefore prudent to predict whether preferred germ lines other than DP54 and DPK9 should be used during ABS of murine clones (13). Additionally, so-called fully human antibody sequences derived from naïve phage display libraries, human B-cell cloning, or transgenic animals will also typically have unnecessary deviations from germ line, caused by somatic hypermutation (1). The ABS process may also be applicable in rapidly germ-lining these antibodies before clinical use.

Although it has previously been shown that some redundant CDR residues can be germ-lined via iterative testing of point mutations (5, 15) or in silico modeling (14), neither of these methods has the power to simultaneously sample e.g., >230, concurrent, potentially synergistic, substitutions that are distal in sequence space, while intrinsically selecting for function. Additionally, methods that maintain the animal CDR-H3 (+/− CDR-L3), then sample human repertoire diversity to return binding affinity (21, 53), may suffer from an inability to recapitulate the critical structural characteristics found outside the CDR-H3s of nonmurine antibodies, as exemplified by our anti-pTau mAb (3). These methods also frequently leave, or generate, significant numbers of framework mutations away from germ line, which can lower the stability of v-domains (22). Indeed, the C7-ABS-RAGE clone illustrated that the CDRs from XT-M4 could be heavily germ-lined and the back mutations from classical humanization fully removed, greatly improving stability in the final molecule.

This study illustrates that three separate antibodies from three species, targeting three different epitopes, all have high levels of sequence tolerance in their paratopes that can be exploited for v-domain risk reduction engineering without the need for prior structural analyses. The retention of SM residues in the CDRs of selected clones after ABS strongly correlated with the prediction of key contact residues in the cocrystal structure of anti-pTau with its target antigen. Residues were also found to be SM if they were likely to be critical in the correct presentation of CDR loops. In only one case was a framework back mutation necessary to include during humanization (VL L46T, anti-pTau). Interestingly, a classical humanization study performed very recently (by another group) on the anti-pTau antibody also sampled the L46 position and found it to be a necessary back mutation to humanize this antibody (54). Importantly, however, four other back mutations in multiple FW regions were also found to be necessary. In the current study we show that the ABS process ameliorates the need for those back mutations to return full binding affinity. This observation suggests that many of the back mutations required during classical humanization of anti-pTau, anti-RAGE, and anti-A33 were likely necessitated by the retention of non-germ-line CDR residues that clash with human framework residue side chains, but are functionally redundant in antigen binding. Importantly, this study therefore suggests that the loss of function in our grafted clones was not due to an inherent defect in VH/VL packing, with the exception of the need for L46T in ABS-pTau clones. Rather, mutations in the CDRs that lead to “local accommodation” improvements are sufficient to recover affinity.

ABS intrinsically minimized redundant animal-derived CDR content by selecting for the retention of essential non-germ-line residues and allowing the rest of the CDR to be converted to the sequence of the destination v-gene. This approach thereby simultaneously optimized all functional parameters of these three potential therapeutic antibodies, which were derived from species often used in monoclonal antibody generation against challenging therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Based on scFv constructs, ABS libraries were synthesized and subjected to phage display selections on their cognate targets. Lead clones identified through sequence analyses and parental IgG competition assays were reformatted to IgG, expressed, purified and their function, structure, and biophysical characteristics were examined as outlined in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

ScFv-Based Library Designs.

Parental and CDR-grafted forms of rat Anti-RAGE (28), rabbit anti-A33 (2), and chicken anti-pTau (3) antibodies, plus a classically humanized (CL-Hum) version of Anti-RAGE were synthesized (Geneart) in VL-VH scFv format, ligated into the phagemid pWRIL-1 and cloned into Escherichia coli TG1 cells as described (28). CDR-grafted forms of each scFv were generated by grafting the CDR sequences shown in Table S1 into the germ-line v-gene sequences DP-54 (IGHV3-7), DP47 (IGHV3-23), DPK9 (IGKV1-39), or DPL16 (IGLV3-19). For these v-domain germ lines, there is extensive published data illustrating their high stability, solubility, expression rates, representation level in the human antibody repertoire and overall manufacturing potential (55–61). The CL-Hum version of Anti-RAGE was also originally grafted onto the DP-54 (IGHV3-7) and DPK9 (IGKV1-39) germ-line frameworks, with the addition of five rat residue back-mutations at positions previously outlined in detail (28).

To ensure that the designed scFvs were suitable for phage display, soluble periplasmic E. coli expression was confirmed by SDS/PAGE and Western blot. Function of each construct was assessed via direct binding ELISA (as purified scFv or periprep), as described (28). Based on these scFv constructs, Augmented Binary Substitution libraries were designed in silico at Pfizer (Fig. 1), then synthesized, via oligonucleotide assembly, as finished dsDNA scFv fragments (Geneart). Anti-pTau is a Type 1 chicken IgG with critical secondary structural characteristics in CDR H2 and H3 (3), and a recent structural study of a humanized chicken antibody suggested that a back mutation at Vλ FW2 position 46 (L46T) is critical to the correct packing of the Vλ against the CDR-H3 stem-loop (3). To examine whether this was still true when random point mutations are also being simultaneously sampled in the CDR-H3, a binary substitution (L/T) was allowed at Vλ position 46 in the ABS-pTau library.

Construction, Selection, and Screening of scFv libraries.

The ABS scFv libraries were constructed, rescued, and selected using methods described in detail (28). Solution phase selection on biotinylated target antigen with streptavidin beads was used throughout. Postselection ELISA and HTRF screening, epitope competition analyses and reformatting were performed as described (28). Selected lead clones were reformatted to IgG, expressed, purified, and characterized as outlined.

IgG Expression and Biophysical Analyses.

IgGs were transiently expressed in HEK-293expi cells after transfection with IgG expression plasmids and expifectamine (Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s protocols. For small-scale expressions: automated purification was carried out using ProPlus resin tips on the MEA system (Phynexus). For larger-scale expression, IgGs were also purified using a 2-step protocol on the Akta 3D system (GE Healthcare). Conditioned media were loaded (neat) onto a 1-mL HiTrap ProA HP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated in PBS pH 7.2. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of PBS pH 7.2, before the protein was eluted with 100 mM glycine, pH 2.7, and subjected to preparative SEC in PBS pH 7.5 using sephacryl S200 column (GE Healthcare).

Differential Scanning Calorimetry.

Proteins were diluted in a PBS solution to 0.3 mg/mL in a volume of 400 µL. PBS was used as a buffer blank in the reference cell. PBS contained 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.47 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2. Samples were dispensed into the sample tray of a MicroCal VP-Capillary DSC with Autosampler (Malvern Instruments). Samples were equilibrated for 5 min at 10 °C and then scanned up to 110 °C at a rate of 100 °C per hour. A filtering period of 16 s was selected. Raw data were baseline corrected and the protein concentration was normalized. Origin Software 7.0 (OriginLab) was used to fit the data to an MN2-State Model with an appropriate number of transitions.

pH Hold Stability Analyses.

Proteins were diluted to 1.5 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.2. The proteins were acidified by adding 0.4 M glycine pH 2.8 to lower the pH from 7.2 to 3.4. The acidified samples were incubated for 5 h at 25 °C. The proteins were neutralized by adding 0.25 M Tris Base. Along with the acidified then neutralized samples, there were control samples that followed the same protocol, except that sample buffer PBS pH 7.2 was added instead of glycine and Tris Base. In some cases the protein concentration was 1.0 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.2 and samples were acidified using citric acid and then incubated for 24 h at 4 °C and neutralized with Tris Base.

Samples were analyzed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on YMC-Pack Diol-200, 300 × 8 mm column with isocratic running buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.2, 400 mM NaCl. Native SEC was used to determine the relative amounts of high molecular mass (aggregate) and monomeric intact antibody. The percent aggregate was calculated as the peak area of the high molecular mass divided by the total (aggregate and monomer) peak area multiplied by 100.

Forced Aggregation Analyses.

Proteins were diluted to 1.0 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.2. Sample (20µl) was dispensed into appropriate wells of a 96-well V-bottom plate and briefly centrifuged to move sample to the bottom of the well. Mineral oil (40 µL) was added to overlay the samples and prevent evaporation. The plate was covered with sealing tape and transferred to a PCR block for heating at 40.0, 43.8, 50.0, 54.0, 60.1, and 64.0 °C using the gradient function. A control sample was also included (20-µL sample, 40 µL of mineral oil in a V-bottom PCR plate) incubated at 4 °C. Samples were incubated for 24 h. Plates were then spun at 4,000 RPM for 5 min, and 15-µL sample was transferred to a vial for injection (10 µL) on YMC-Pack Diol-200, 300 × 8 mm column with isocratic running buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.2, 400 mM NaCl. The monomer peak area for the heated samples was compared with the nonheated control to calculate percent aggregate in comparison with a control antibody of known high stability (55).

Biacore Analysis of Binding Kinetics.

Biacore analysis was performed using the T-200 biosensor, series S CM5 chips, an amine-coupling kit, 10 mM sodium acetate immobilization buffer at pH 5.0, 10× HBS-P running buffer and NaOH for regeneration (GE Healthcare). Kinetic assay conditions were established to minimize the influence of mass transfer, avidity and rebinding events. A predefined ligand immobilization program was set up to immobilize ∼100 Response Units (RU) of IgG on the chip. Purified target proteins were diluted in HBS-P running buffer to a range of final concentrations and injected at 50 µL/min for 3 min. Dissociation was allowed to proceed for 10 min followed by a 5-s pulse of 20 mM NaOH for regeneration of the chip surface. All sensorgrams were analyzed using the Biacore T-200 evaluation software.

Binding Specificity Analyses.

Anti-RAGE, pTau, and A33 antibodies were tested for polyreactivity by ELISA and Biacore analyses. ELISAs were performed against single stranded DNA, double stranded DNA, insulin and lipopolysaccaride (62), and against Baculovirus particles (39). All polyreactivity analyses used parental antibodies and Pfizer in-house positive and negative control antibodies (40).

Biacore specificity analyses were performed using the T-200 biosensor, series S CM5 chips, an amine-coupling kit, 10 mM sodium acetate immobilization buffer at pH 5.0, 10× HBS-P running buffer and NaOH for regeneration (GE Healthcare). A predefined ligand (IgG) immobilization program was set up to immobilize ∼300 Response Units (RU) on the flow cell for each IgG to be tested. For Anti-RAGE and anti-A33, panels of purified, recombinant, target and nontarget antigens were diluted in HBS-P running buffer to a final concentration of 500 nM. Four groups of antigens were examined, including: cell membrane proteins (mTRKB, hTRKB, mEGFR, hEGFR, hFceR1, hIL-21R, mICAM1, mICAM2, hICAM1, hCD33, hLAMP-1, hLOX-1), soluble signaling molecules (mTNFa, hVEGF, hCXCL13), and albumins (BSA, HSA and MSA). These proteins were injected at 50 µL/min for 3 min, followed by a 5 s pulse of 20 mM NaOH for regeneration of the chip surface. For pTau, a series of pTau-derived phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides were flowed, as in Shih et al. (3). All sensorgrams were analyzed using the Biacore T-200 evaluation software.

Modeling Analyses.

Variable domain structural models were generated for the parental, humanized and ABS humanized variants of the anti-pTAU, the anti-RAGE and the Anti-A33 antibodies. The Protein Databank (PDB) crystal structure 4GLR of the anti-pTau antibody was used for the parental pTau model. For the humanized and ABS humanized pTau antibodies, we generated homology models using Modeler version 9.12 (63) with the PDB structures of 4GLR and 3G6A as templates. For all three XTM4 structures, homology models were also generated using Modeler with template structure 1fvd, 1dql, 3hns, 1mhp, 1bbj, 1bog, 1aif, 1ar1, and 1rmf for the parental; 1fvd, 1dql, 1mhp, 3hns, 1bbj, 1bog, 1aif, 1ar1, and 1rmf for the humanized; and 1mhp, 3hns, 2cmr, 1gig, 2ghw, 1aif, and 1rmf for the ABS humanized. For all three anti-A33 structures, homology models were also generated using Modeler with template structures 3qos, 4d9q, 3v9g, 3tt1, 1nfd, 4ht1, 2or9, 1tzh, and 3ojd for the parental; 3hr5, 2or9, 1tzh, 3ojd, 3vg9, 3tt1, and 1nfd for the humanized; and 3hr5, 2orb, 1tzh, 3ojd, 3vg9, 3e8u, and 4d9l for the ABS humanized. The nonhuman solvent accessible surface area (nhSASA) was calculated using the “Solvent Accessibility” calculator in the molecular modeling software suite Discovery Studio Client 4.0 (Accelrys). The nhSASA was defined as the sum of the side-chain SASA of residues that were not identical to germ line.

In Silico T-Cell Epitope Assessment.

Sequences of antibody VH and VL regions were analyzed by EpiMatrix (Epivax, RI) (64). Briefly, each domain was parsed into overlapping 9-mer peptides with each peptide overlapping the last by eight amino acids. Each peptide was then scored for predicted binding to each of eight HLA Class II alleles (DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0701, DRB1*0801, DRB1*1101, DRB1*1301, and DRB1*1501) which represent HLA supertypes covering 97% of human populations worldwide (65). Any peptide scoring above 1.64 on the EpiMatrix “Z” scale (approximately the top 5% of the random peptide set) was classed as a “hit” for binding to the MHC molecule for which it was predicted. Peptides scoring four or more hits from the eight alleles predicted are considered as possible epitopes. Some germ-line sequences have been suggested to induce t regulatory cells. A previous study with a therapeutic protein demonstrated a correlation between an immunologically active peptide, i.e., T-cell epitope, and the EpiMatrix prediction (66).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pfizer Post-Doctoral Research program, Will Somers, Eric Bennett, and Davinder Gill for their support and insightful commentary.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors are current or former employees of Pfizer.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1510944112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nelson AL, Dhimolea E, Reichert JM. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(10):767–774. doi: 10.1038/nrd3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rader C, et al. The rabbit antibody repertoire as a novel source for the generation of therapeutic human antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(18):13668–13676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih HH, et al. An ultra-specific avian antibody to phosphorylated tau protein reveals a unique mechanism for phosphoepitope recognition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(53):44425–44434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller RA, Oseroff AR, Stratte PT, Levy R. Monoclonal antibody therapeutic trials in seven patients with T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1983;62(5):988–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding FA, Stickler MM, Razo J, DuBridge RB. The immunogenicity of humanized and fully human antibodies: Residual immunogenicity resides in the CDR regions. MAbs. 2010;2(3):256–265. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jawa V, et al. T-cell dependent immunogenicity of protein therapeutics: Preclinical assessment and mitigation. Clin Immunol. 2013;149(3):534–555. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PT, Dear PH, Foote J, Neuberger MS, Winter G. Replacing the complementarity-determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature. 1986;321(6069):522–525. doi: 10.1038/321522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almagro JC, Fransson J. Humanization of antibodies. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1619–1633. doi: 10.2741/2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang WY, Foote J. Immunogenicity of engineered antibodies. Methods. 2005;36(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baca M, Presta LG, O’Connor SJ, Wells JA. Antibody humanization using monovalent phage display. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(16):10678–10684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dall’Acqua WF, et al. Antibody humanization by framework shuffling. Methods. 2005;36(1):43–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis MS. CDR repair: A novel approach to antibody humanization. Current Trends in Monoclonal Antibody Development and Manufacturing. 2010;1(1):9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fransson J, et al. Human framework adaptation of a mouse anti-human IL-13 antibody. J Mol Biol. 2010;398(2):214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanf KJ, et al. Antibody humanization by redesign of complementarity-determining region residues proximate to the acceptor framework. Methods. 2014;65(1):68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazar GA, Desjarlais JR, Jacinto J, Karki S, Hammond PW. A molecular immunology approach to antibody humanization and functional optimization. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(8):1986–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan P, et al. “Superhumanized” antibodies: Reduction of immunogenic potential by complementarity-determining region grafting with human germline sequences: Application to an anti-CD28. J Immunol. 2002;169(2):1119–1125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padlan EA. A possible procedure for reducing the immunogenicity of antibody variable domains while preserving their ligand-binding properties. Mol Immunol. 1991;28(4-5):489–498. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90163-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haidar JN, et al. A universal combinatorial design of antibody framework to graft distinct CDR sequences: A bioinformatics approach. Proteins. 2012;80(3):896–912. doi: 10.1002/prot.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finlay WJ, Almagro JC. Natural and man-made V-gene repertoires for antibody discovery. Front Immunol. 2012;3:342. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almagro JC, et al. Second antibody modeling assessment (AMA-II) Proteins. 2014;82(8):1553–1562. doi: 10.1002/prot.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowers PM, et al. Humanization of antibodies using heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 grafting coupled with in vitro somatic hypermutation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(11):7688–7696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun SB, et al. Mutational analysis of 48G7 reveals that somatic hypermutation affects both antibody stability and binding affinity. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(27):9980–9983. doi: 10.1021/ja402927u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Bumbaca D, et al. Highly specific off-target binding identified and eliminated during the humanization of an antibody against FGF receptor 4. MAbs. 2011;3(4):376–386. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.4.15786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Meer PJ, et al. Immunogenicity of mAbs in non-human primates during nonclinical safety assessment. MAbs. 2013;5(5):810–816. doi: 10.4161/mabs.25234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Aerts LA, De Smet K, Reichmann G, van der Laan JW, Schneider CK. Biosimilars entering the clinic without animal studies. A paradigm shift in the European Union. MAbs. 2014;6(5):1155–1162. doi: 10.4161/mabs.29848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg AS. Effects of protein aggregates: An immunologic perspective. AAPS J. 2006;8(3):E501–E507. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadi M, et al. Small amounts of sub-visible aggregates enhance the immunogenic potential of monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Pharm Res. 2015;32(4):1383–1394. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finlay WJ, et al. Affinity maturation of a humanized rat antibody for anti-RAGE therapy: Comprehensive mutagenesis reveals a high level of mutational plasticity both inside and outside the complementarity-determining regions. J Mol Biol. 2009;388(3):541–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernett MJ, et al. Engineering fully human monoclonal antibodies from murine variable regions. J Mol Biol. 2010;396(5):1474–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacCallum RM, Martin AC, Thornton JM. Antibody-antigen interactions: Contact analysis and binding site topography. J Mol Biol. 1996;262(5):732–745. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almagro JC. Identification of differences in the specificity-determining residues of antibodies that recognize antigens of different size: Implications for the rational design of antibody repertoires. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17(2):132–143. doi: 10.1002/jmr.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raghunathan G, Smart J, Williams J, Almagro JC. Antigen-binding site anatomy and somatic mutations in antibodies that recognize different types of antigens. J Mol Recognit. 2012;25(3):103–113. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vajdos FF, et al. Comprehensive functional maps of the antigen-binding site of an anti-ErbB2 antibody obtained with shotgun scanning mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 2002;320(2):415–428. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bostrom J, et al. Variants of the antibody herceptin that interact with HER2 and VEGF at the antigen binding site. Science. 2009;323(5921):1610–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1165480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chailyan A, Marcatili P, Cirillo D, Tramontano A. Structural repertoire of immunoglobulin λ light chains. Proteins. 2011;79(5):1513–1524. doi: 10.1002/prot.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.North B, Lehmann A, Dunbrack RL., Jr A new clustering of antibody CDR loop conformations. J Mol Biol. 2011;406(2):228–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chothia C, Lesk AM. Canonical structures for the hypervariable regions of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol. 1987;196(4):901–917. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin AC, Thornton JM. Structural families in loops of homologous proteins: Automatic classification, modelling and application to antibodies. J Mol Biol. 1996;263(5):800–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hötzel I, et al. A strategy for risk mitigation of antibodies with fast clearance. MAbs. 2012;4(6):753–760. doi: 10.4161/mabs.22189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vugmeyster Y, et al. Correlation of pharmacodynamic activity, pharmacokinetics, and anti-product antibody responses to anti-IL-21R antibody therapeutics following IV administration to cynomolgus monkeys. J Transl Med. 2010;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampei Z, et al. Identification and multidimensional optimization of an asymmetric bispecific IgG antibody mimicking the function of factor VIII cofactor activity. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li B, et al. Framework selection can influence pharmacokinetics of a humanized therapeutic antibody through differences in molecule charge. MAbs. 2014;6(5):1255–1264. doi: 10.4161/mabs.29809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu H, et al. Ultra-potent antibodies against respiratory syncytial virus: Effects of binding kinetics and binding valence on viral neutralization. J Mol Biol. 2005;350(1):126–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.USFDA 2014. Guidance for Industry - Immunogenicity Assessment for Therapeutic Protein Products. Available at www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm338856.pdf.

- 45.Roguska MA, et al. Humanization of murine monoclonal antibodies through variable domain resurfacing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(3):969–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao SH, Huang K, Tu H, Adler AS. Monoclonal antibody humanness score and its applications. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:55. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thullier P, Huish O, Pelat T, Martin AC. The humanness of macaque antibody sequences. J Mol Biol. 2010;396(5):1439–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abhinandan KR, Martin AC. Analyzing the “degree of humanness” of antibody sequences. J Mol Biol. 2007;369(3):852–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, et al. Developability studies before initiation of process development: Improving manufacturability of monoclonal antibodies. MAbs. 2013;5(5):787–794. doi: 10.4161/mabs.25269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strohl WR. Modern therapeutic antibody drug discovery technologies. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2014;11(1):1–2. doi: 10.2174/157016381101140124160256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogen B, Ruffini P. Review: To what extent are T cells tolerant to immunoglobulin variable regions? Scand J Immunol. 2009;70(6):526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazor R, Tai CH, Lee B, Pastan I. Poor correlation between T-cell activation assays and HLA-DR binding prediction algorithms in an immunogenic fragment of Pseudomonas exotoxin A. J Immunol Methods. 2015;425:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rader C, Cheresh DA, Barbas CF., 3rd A phage display approach for rapid antibody humanization: Designed combinatorial V gene libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(15):8910–8915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baek DS, Kim YS. Humanization of a phosphothreonine peptide-specific chicken antibody by combinatorial library optimization of the phosphoepitope-binding motif. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463(3):414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.King AC, et al. High-throughput measurement, correlation analysis, and machine-learning predictions for pH and thermal stabilities of Pfizer-generated antibodies. Protein Sci. 2011;20(9):1546–1557. doi: 10.1002/pro.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ewert S, Huber T, Honegger A, Plückthun A. Biophysical properties of human antibody variable domains. J Mol Biol. 2003;325(3):531–553. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knappik A, et al. Fully synthetic human combinatorial antibody libraries (HuCAL) based on modular consensus frameworks and CDRs randomized with trinucleotides. J Mol Biol. 2000;296(1):57–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahon CM, et al. Comprehensive interrogation of a minimalist synthetic CDR-H3 library and its ability to generate antibodies with therapeutic potential. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(10):1712–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prassler J, et al. HuCAL PLATINUM, a synthetic Fab library optimized for sequence diversity and superior performance in mammalian expression systems. J Mol Biol. 2011;413(1):261–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi L, et al. De novo selection of high-affinity antibodies from synthetic fab libraries displayed on phage as pIX fusion proteins. J Mol Biol. 2010;397(2):385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tiller T, et al. A fully synthetic human Fab antibody library based on fixed VH/VL framework pairings with favorable biophysical properties. MAbs. 2013;5(3):445–470. doi: 10.4161/mabs.24218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mouquet H, et al. Polyreactivity increases the apparent affinity of anti-HIV antibodies by heteroligation. Nature. 2010;467(7315):591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature09385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eswar N, et al. Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr Protocols Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 5:Unit 5 6. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schafer JR, Jesdale BM, George JA, Kouttab NM, De Groot AS. Prediction of well-conserved HIV-1 ligands using a matrix-based algorithm, EpiMatrix. Vaccine. 1998;16(19):1880–1884. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Southwood S, et al. Several common HLA-DR types share largely overlapping peptide binding repertoires. J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3363–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koren E, et al. Clinical validation of the “in silico” prediction of immunogenicity of a human recombinant therapeutic protein. Clin Immunol. 2007;124(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.03.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]