Abstract

Dependence on and abuse of prescription opioid drugs is now a major health problem, with initiation of prescription opioid abuse exceeding cocaine in young people. Coincident with the emergence of abuse and dependence on prescription opioids, there has been an increased emphasis on the treatment of pain. Pain is now the “5th vital sign” and physicians face disciplinary action for failure to adequately relieve pain. Thus, physicians are whipsawed between the imperative to treat pain with opioids and the fear of producing addiction in some patients. In this article we characterize the emerging epidemic of prescription opioid abuse, discuss the utility of buprenorphine in the treatment of addiction to prescription opioids, and present illustrative case histories of successful treatment with buprenorphine.

Keywords: Prescription, Opioid, Opiate, Addiction, Buprenorphine

Prescription Opioid Abuse in the US – An Emerging Epidemic

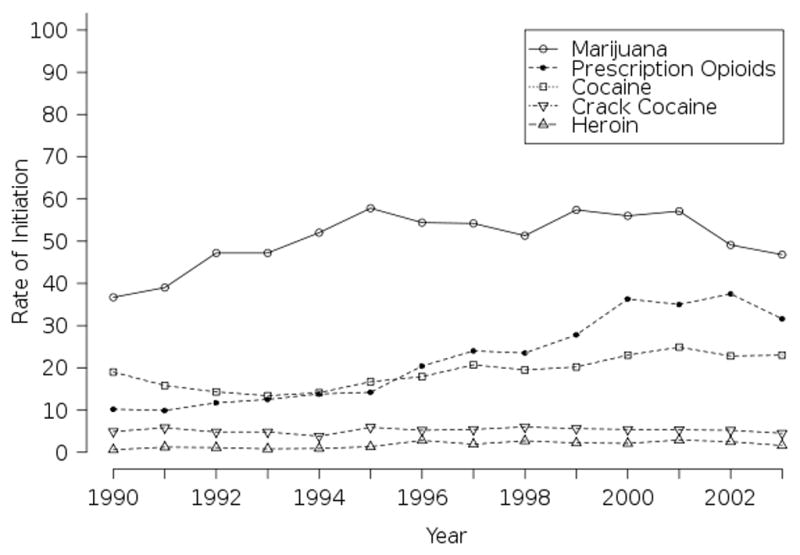

Abuse of prescription opioid analgesics has emerged as a major public health problem in the US (Zacny et al., 2003), with abuse of drugs such as OxyContin® becoming “ubiquitous” (Cicero, Inciardi, & Munoz, 2005). Between 1990 and 2003, the rate at which young adults initiated abuse of prescription opioids (ie use not sanctioned by a physician) tripled, from 10.2/thousand person-years in 1990 to 31.6/thousand person-years in 2003 (Figure 1) (SAMHSA, 2004). Each year since 1999, more than 2 million adults started abusing prescription opioids in the US (SAMHSA, 2006). In 2005, 2.4 percent of the US population aged 18 to 25 (794,000 persons) initiated use of a pain reliever for a non-medical purpose. Abuse of prescription opiates starts later than abuse of marijuana or alcohol: the average age of first non-medical use of a pain reliever was 21.9 years, of marijuana 19.0 years, and of alcohol 16.6 years (SAMHSA, 2006a). “Generation Rx” is the popular name given by the Partnership for a Drug Free America for these young adult prescription opioid abusers. Young adults are much more likely to start abusing prescription opioids than they are to start abusing illegal opioids such as heroin, and initiation of prescription opioids abuse overtook that of cocaine abuse in 1996 (Compton, Darakjian, & Miotto, 1998).

Figure 1.

Rates of first use of select drugs in US adults age 18–25 (per 1,000 person-years of exposure): 1990–2003.

(Source: 2002–2004 NSDUH, SAMHSA)

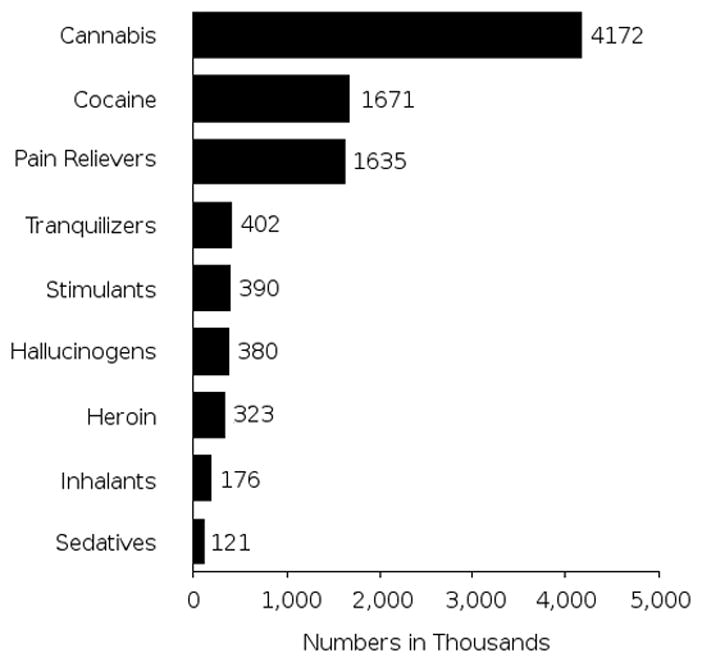

Among all Americans 12 years and older in 2006, 13.6% (more than 33 million) reported a lifetime history of non-medical use of prescription opioids. More than twelve million reported use in the prior year, and 5.2 million during the prior month. By comparison, 3.8 million reported ever using heroin (1.5%), 560,000 in the previous year and 338,000 in the prior month (SAMHSA, 2006b). Approximately 1.6 million Americans met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence of prescription opioids in 2006 (SAMHSA, 2006c). Over five times more Americans abuse or are dependent on prescription pain relievers than abuse or are dependent on heroin. Dependence on or abuse of prescription opioids is now as common as dependence/abuse of cocaine, and more common than dependence/abuse of any other drug except marijuana (Figure 2) (SAMHSA, 2006c).

Figure 2.

Dependence on or abuse of specific illicit drugs in the past year in persons age 12 or older.

(Adapted from 2006 NSDUH. SAMHSA)

Prescription opioids have more “street value” than marijuana and heroin, and are second only to cocaine in that regard, indicating that a market developed in illicit users (Parran, 1997). Because prescription opioids can be legally obtained through a physician, there may be a perception that non-medical use of these drugs is less problematic than abuse of illicit substances. However, a parallel rise in the consequences of misuse belies this perception. US college students abusing prescription opioids are over four times more likely to report frequent binge drinking, over three times more likely to drive after drinking alcohol, four times more likely to drive after binge drinking, and almost six times more likely to be a passenger in a car with a drunk driver (McCabe, Teter, Boyd, Knight, & Wechsler, 2005). According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN), the estimated number of emergency department (ED) visits involving opioid analgesic abuse in the US more than doubled, from 90,232 to 196,225 visits, between 2001 and 2005 (DAWN, 2005). The prescription opioids hydrocodone and oxycodone (and their combination formulations) alone were involved in 6.5% of all drug abuse-related ED visits in 2005, and visits involving either hydrocodone or oxycodone formulations each accounted for more ED visits than methadone (DAWN, 2005). Indeed, the number of ED visits involving these two prescription drugs were more than half the total visits involving heroin. ED visits involving prescription opioids increased 24% between 2004 and 2005 alone, including a 92% increase for hydromorphone formulations (SAMHSA, 2006).

Persons misusing prescription opioids are not just presenting to emergency departments more frequently. According to surveillance data on the number of patients admitted for substance abuse treatment, such persons are also seeking treatment in record numbers. For the decade 1995 – 2005, admissions for the abuse of opioids other than heroin increased from 1 percent to 4 percent. Between 1995 and 2005, rates of treatment admissions involving opioid analgesics more than tripled, from 7 to 26 admissions per 100,000 persons aged 12 and over in the US. In the year 2005, there were more than 64,000 such admissions, and over 1,100 were of patients aged 12–17. While in about half of these visits, opioid analgesics were co-abused with another drug, in the other half an opioid analgesic was the only drug of abuse (TEDS, 2005).

There are several differences between heroin abusers and prescription opioid abusers. Compared to heroin abusers, prescription opioid abusers are more likely to be Caucasian, be younger, have higher incomes, use less opioid per day, and not be injection drug users. Prescription opioid users seek treatment earlier, are more likely to be successfully induced into and complete treatment, and have better outcomes than patients using heroin. Prescription opioid users are also less likely to have hepatitis C infection, and have fewer episodes of drug treatment (Moore et al., 2007). Furthermore, prescription opioid abusers have fewer family and social problems, and report receiving less income from illegal sources (Sigmon, 2006). Brands and coworkers in Toronto found that 83% of the patients presenting for methadone therapy were addicted to prescription opioids. Surprisingly, in 48% of these patients, prescription opioids were the primary source of opioids. 24% used only prescription opioids and 24% started with prescription opioids and migrated to heroin later. In contrast, 35% were primary heroin addicts who also abused prescription opioids; only 17% used heroin exclusively (Brands, Blake, Sproule, Gourlay, & Busto, 2004). These prescription opioid addicts consumed enormous amounts of short-acting codeine and oxycodone formulations - 23±6 and 21±3 tablets per day of codeine and oxycodone respectively - equivalent to about 200 mg of morphine per day. About 80% of these patients started using opioids for the treatment of pain and they obtained almost all of their medications from physicians. It is important to note that most were on short-acting opioids that are usually combined with acetaminophen, aspirin or ibuprofen. Consequently, these patients received enormous exposures to nephro- and hepatotoxic drugs and metabolites (eg 10–20 grams per day of acetaminophen).

Why do people initially become involved with prescription opioids? Brands et al found that most had started using opioids to relieve pain. It is estimated that more than 75 million Americans suffer from chronic, debilitating pain, hence the population at risk is enormous (National Pain Foundation, 2007). Becker et al note that “undertreated chronic pain is a cause of low self-rated health status that may compel individuals to non-medical use of prescription opioids” (Becker, Sullivan, Tetrault, Fiellen et al., 2008). Pain patients may be psuedoaddicted, appearing to abuse opioids secondary to addiction, but in fact trying to relieve undertreated pain (Longo, Parran, Johnson, & Kinsey, 2000).

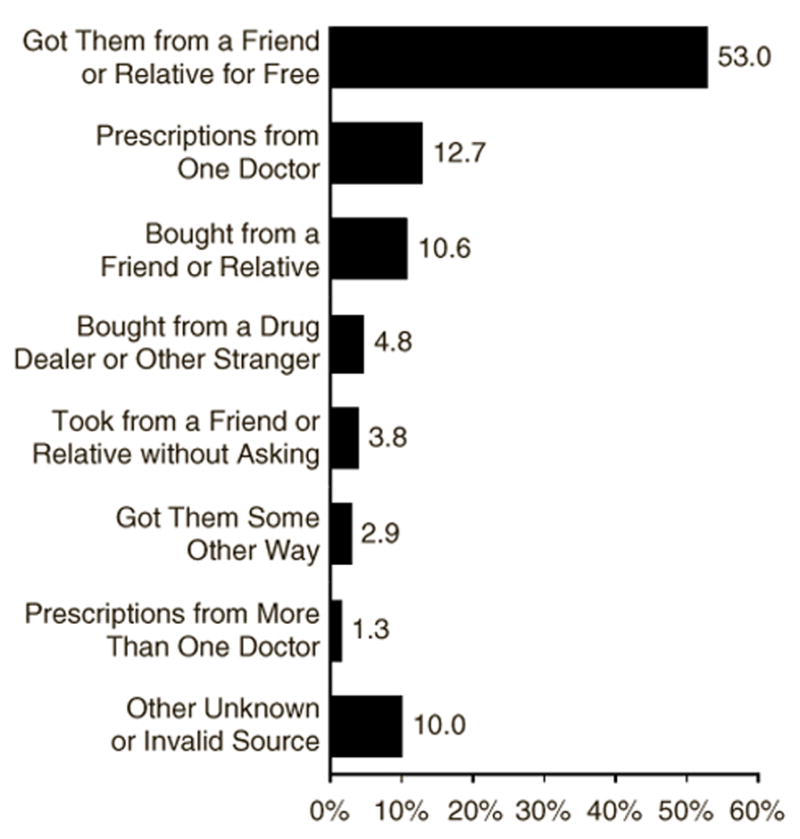

Physicians, of course, are charged with relieving pain – “the fifth vital sign”. We will discuss later how physician prescribing patterns for opioids may affect rates of misuse. However, most prescription opioid abusers obtain their drugs from family members, and not directly from physicians (Figure 3) (Carise et al., 2007; Davis & Johnson, 2008; Rosenblum et al., 2007). For example, in one recent study 70% of the sample obtained prescription opioids (OxyContin®) from friends and only 14% obtained them directly from physicians (Levy 2007).

Figure 3.

Percentages of reported method of obtaining prescription opioids for most recent nonmedical use in past year among persons age 18–25.

(Adapted from 2005 NSDUH, SAMHSA)

An increasing number of prescription opioid misusers are being referred for opioid substitution therapy with buprenorphine or methadone. Buprenorphine is marketed for this indication as a single agent, Subutex®, and in combination with naloxone, Suboxone®; the addition of naloxone is to deter parenteral abuse.

Case Reports

AB is a 60 year-old information technology professional who presented with 6 months of escalating prescription analgesic abuse. Prescription opioids (Vicodin®; hydrocodone 7.5 mg and acetaminophen 325 mg every 6 hours; 30 mg per day of hydrocodone) were initiated for pain control following oral surgery. Although pain control was adequate AB rapidly escalated hydrocodone dosing to approximately 150 mg per day, and decreasing or stopping hydrocodone resulted in classic opioid withdrawal symptoms. Hydrocodone was obtained from his physician, but as he increased the amount consumed he obtained drug from friends and later from the Internet. Before the oral surgery there was no history of opioid dependence or abuse but there was a long history of alcoholism in remission (with two years sobriety). The medical history was notable for nicotine dependence (30 pack-years), moderate depression and a spontaneous pneumothorax at age 40. AB is employed, in a stable long-term relationship and has an advanced degree. Physical examination showed no evidence of intravenous drug use and HIV and hepatitis C serology were negative. Treatment options were discussed and he elected buprenorphine substitution therapy. Induction was uneventful and 1.5 years post induction he is stable on 16 mg/day of sublingual Suboxone®. Urine toxicology tests, obtained on each office visit, have showed no evidence of hydrocodone use. After 1 year of treatment he feels good, there are no significant adverse effects of treatment and he is not yet interested in tapering buprenorphine.

CD is a 35 year old with a 10-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus (speckled antinuclear antibodies) with joint and skin involvement. About one year before consultation she was started on hydrocodone-acetaminophen combination analgesic for arthralgias and headache. Although the lupus flair resolved, she continued to use hydrocodone with the dose escalating to more than 200 mg/day (with an acetaminophen dose of approximately 7.5 gm/day). Hydrocodone was obtained from friends and over the Internet. There was no history of nicotine, alcohol or opioid abuse or addiction. CD has a long history of depression and was in psychotherapy at presentation. She is married, has a daughter and is employed in academia. The large hydrocodone dose made induction difficult but she eventually stabilized on Suboxone® 40 mg/day. Three years later, despite attempts, she has not been able to decrease the dose but is not using any other opioids. Notably, despite family stresses (divorce in process, precipitated by husbands alcoholism and depression), her depression is improved; she attributes this to buprenorphine.

Sublingual buprenorphine is approved in a dose range of 2–32 mg with some evidence that more than 98% of all μ-opiate receptors are occupied at doses of 32 mg/day (Greenwald et al., 2003). Buprenorphine has kappa opiate antagonists properties and kappa antagonists may have antidepressant effects (Shirayama et al., 2004; Zhang, Shi, Woods, Watson, & Ko, 2007). Both patients had depression, and perhaps the kappa antagonist-antidepressant properties of buprenorphine account for the higher than usual dose needed by CD.

These cases illustrate some of the challenges in treating iatrogenic dependence. Neither patient had a history of opioid abuse or dependence and the initial opioid pharmacotherapy for pain appears appropriate. Although depression was present in both patients it was not severe. Substantial dose escalation of analgesic opiates occurred over a relatively short period and stopping use resulted in withdrawal symptoms. Fortunately, the patients recognized the need for treatment, and induction on Suboxone® was relatively easily achieved. On the downside substitution treatment has lasted longer than the initial episode of opioid abuse. At present, the best dose and duration of substitution therapy with buprenorphine for prescription opiate addiction remains to be defined. These cases have some features that are commonly seen in our (JM) practice (initiation of opiates for pain with relatively rapid dose escalation) and that are atypical (the long period on substitution therapy and, for CD, the high buprenorphine dose). Thus, much remains to be learned about buprenorphine substitution therapy in prescription opioid addicts.

These cases raise two important issues that we discuss below. First, what is the contribution of opioid prescribing to the burden of addiction? Second, is there evidence of efficacy for opioid substitution therapy in prescription opioid addiction?

US Trends in Ambulatory Care Opioid Prescribing From 1993–2005

Opioid prescribing contributes to the supply of abusable opioids, but little is known about how opioid prescribing patterns have changed during this time. We (MP) have studied the contribution of physician prescribing to the rise in prescription opioid dependence. Pletcher evaluated the changes in opioid prescribing for pain by emergency departments using 13 years (1993–2005) of data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Pain-related visits accounted for 156,729 of 374,891 (42%) emergency department visits. Opioid prescribing for pain-related visits increased from 23% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21%–24%) in 1993 to 37% (95% CI, 34%–39%) in 2005 (P < .001 for trend), and this trend was more pronounced in 2001–2005 (P = .02), most likely due to national quality improvement initiatives in the late 1990 stressing adequate treatment of pain (Pletcher, Kertesz, Kohn, & Gonzales, 2008). To estimate prescribing patterns in medical offices we used 10 years of survey data (from 1993–2003) from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (a nationally representative stratified cluster sample of approximately 30,000 physician office visits per year) to estimate how many US office visits included prescription of an opioid medication (an “opioid visit”) to persons aged 12 and over. We calculated rates using US Census denominators and categorized opioid visits by type of opioid in order to explain overall trends. Among the 272,983 evaluated visits we identified 11,327 opioid visits, representing ~32 million office opioid visits/year in the US, an average rate of 0.142 opioid visits per person per year (95%CI: 0.134–0.149).

Two pronounced time trends were evident: a significant increase in the visit rate over the decade from 0.126 in 1993 to 0.166 in 2003, a 32% increase (p<0.001 for trend) and a large shift in the types of opioids prescribed. Whereas codeine and propoxyphene visit rates declined (40% and 28% respectively, paralleling a decline in DAWN mentions), visit rates for higher potency opioids such as hydrocodone and oxycodone increased (115% and 156%). Most of the increased opioid visit trend was explained by hydrocodone visits, which increased at a rate of ~1 million additional visits per year from 1993–2003 up to a total of 18 million hydrocodone visits in 2003 (95%CI: 14–22 million, 45% of all 2003 opioid visits). These data show that opioid prescribing patterns in ambulatory care have changed markedly in the last decade. Even if all opioid prescribing were appropriate, co-occurring increases in opioid abuse and prescribing suggest the possibility that emergency room and office visit prescribing are channels for the supply of abused opioids in the US. Accordingly, methods that decrease the level of potentially harmful prescribing may have a large impact on prescription opioid dependence.

The recognition that opioid pain pharmacotherapy can lead to opioid addiction has fueled calls for increased regulation of opioid prescribing. The most common regulatory solution is to increase the DEA schedule category (from III, IV and V to II) of commonly prescribed prescription opioids. Altering the DEA schedule obviously does not alter the pharmacologic effects of opioid analgesics, but can theoretically decrease the availability of prescription opioid by increasing the barriers to prescribing. However, one argument against a regulatory solution is that current schedule II medications include the oxycodone formulations, which continue to be widely abused. Although decreasing the legitimate supply of prescription opioids might diminish the numbers of new pain patients receiving opioid substitution therapy, many patients with chronic pain would be deprived of an essential medicine.

There has been difficulty quantifying the risk for iatrogenic addiction in patients on opioids (Wasan, Correll, Kissin, O’Shea, & Jamison, 2006). Strategies for minimizing such risk include careful patient evaluation, the use of standardized instruments (see, for example, the Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool, Passik et al., 2004), maximizing first other treatment options, using goal directed therapy, maintaining careful documentation and written patient agreements, prescribing opioids as adjuncts where possible, monitoring pharmacies for opioid quantities used, and weaning and discontinuation if treatment goals are not met (Ballantyne & LaForge, 2007).

Treatments for Addiction to Prescription Opioids

Medications studied for prescription opioid dependence include methadone, naltrexone, levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM), and buprenorphine formulations. Although methadone has been a mainstay of opioid addiction treatment, in the US this treatment may only be provided in specially licensed clinics, and these clinics can only treat a limited number of patients. By one estimate, treatment slots for methadone maintenance are available to only 20% of Americans with opioid addiction (Cunningham, Kunins, Roose, Elam, & Sohler, 2007). Methadone has not been available in some US states (McCance-Katz, 2004), and communities often resist allowing methadone clinics to open or expand. Patients attending a clinic dedicated to treating a socially unpopular disease may feel stigmatized. Methadone medical maintenance, where methadone is prescribed in a medical setting and provides more take-home medication to stable patients, is one alternative to traditional methadone clinics. However, regulatory complexity and protocol development has limited expansion of this model (Merrill et al., 2005).

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, has little abuse potential, but treatment outcomes in studies have been mixed, and its use is inappropriate in abusers with chronic pain. There is also poor compliance and retention with its use (Minozzi et al., 2006), although better treatment retention has been reported with a naltrexone depot formulation (Comer et al., 2006).

LAAM is a pure opioid agonist and is approved for treatment of opioid dependence, although there are no studies of its use in prescription opioid abusers. Unfortunately, the US Food and Drug Administration required a ‘black box’ warning on the drug in 2001 after reports of QT interval prolongation and cases of torsades de pointes in patients treated with LAAM (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2001) and since 2004 LAAM has not been available in the United States.

In contrast to methadone, buprenorphine may be prescribed in a physician’s office, and dosing is done not in the clinic but at home. When treatment is initiated in a physician’s office, the concomitant physical and mental health issues that so often accompany opioid dependence can also be addressed. Offering office-based treatment with buprenorphine is associated with new types of patients entering treatment (Sullivan, Chawarski, O’Connor, Schottenfeld, & Fiellin, 2005). Buprenorphine appears less likely to produce an overdose due to a ceiling effect on respiratory depression (Dahan, 2006). Buprenorphine causes less QT prolongation than LAAM or methadone (Wedam, Bigelow, Johnson, Nuzzo, & Haigney, 2007). Like methadone, buprenorphine treatment may decrease risky behaviors, including drug-related HIV risk behaviors (Sullivan et al., 2007). Rapeli reported that buprenorphine-naloxone treatment is preferable to methadone treatment for preserving cognitive function in early treatment – an important benefit for prescription opioid addicts who are employed (Rapeli et al., 2007). Barry found that patients were satisfied with office-based buprenorphine treatment and expressed strong willingness to refer a substance-abusing friend for the same treatment (Barry et al., 2007).

Studies consistently show efficacy of buprenorphine treatment in opioid dependence, but most describe results in heroin users or mixed populations of heroin and prescription opioid users. A study of 99 patients treated with buprenorphine in four primary care clinics found 54% were sober at 6 months. Of the abstinent group, 40% were prescription opioid users, compared to 38% of the nonabstinent patients (Mintzer et al., 2007). The NIDA Clinical Trials Network Field Experience assessed buprenorphine for short-term opioid detoxification, and reported high compliance and treatment engagement, excellent safety, and a 68% completion rate. However, only 8% of that study population reported exclusive use of opioids other than heroin (Amass et al., 2004). Fiellin found reductions in the frequency of opioid use with three different patterns of buprenorphine dispensing and counseling in a treatment group that included 15–20% prescription opioid users (Fiellin et al., 2006). Caldiero reported that subjects maintained on buprenorphine (30% of whom were exclusively prescription opioid users) were more likely to initiate outpatient therapy and remained in outpatient treatment longer when compared to patients detoxified with tramadol (Caldiero, Parran, Adelman, & Piche, 2006). In another study of retention in primary care based buprenorphine treatment, 59% remained in treatment at 24 weeks. In this study 50% were heroin users, compared with 27% whose primary drug was another opioid, and heroin users were more likely to terminate treatment early. As previously noted, a study by Sullivan suggested that office based buprenorphine treatment expands access for patients who may not enroll in methadone clinics, and facilitates earlier access to treatment for patients who have more recently started opioid use (Sullivan et al., 2005). In that study, approximately 10% of subjects used a primary opioid other than heroin. The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Association (SAMHSA) evaluation of the buprenorphine waiver program in the US, in which 40% of the subjects were prescription opioid-only misusers, found that treatment with buprenorphine was “clinically effective”, “well accepted by patients”, and “increased the availability of medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction”. There were minimal problems with diversion or adverse clinical events (Stanton et al., 2006).

The optimal duration of therapy with buprenorphine remains to be determined. The issue of termination of therapy is not trivial. In both clinical cases we presented above, the duration of therapy has exceeded the time spent abusing and there is no evidence-based data to suggest when or if substitution therapy can be discontinued. It appears that most heroin dependent patients on methadone maintenance should be treated on an ongoing basis (Sorensen, Trier, Brummett, Gold, & Dumontet, 1992), but similar studies have not been conducted with prescription opioid dependent patients on buprenorphine.

Participants in a March 2003 conference on the US national buprenorphine implementation program called for physicians to “move opioid addiction treatment into the mainstream of American medicine through office-based practice” by expanding use of buprenorphine-naloxone (Kosten & Fiellin, 2004). Education and experience should help this effort, but other barriers remain. Horgan et al reported that about one third of insurance plans excluded buprenorphine from formularies, and if it was included, it was usually placed in the highest cost-sharing tier (Horgan, Reif, Hodgkin, Garnick, & Merrick, 2008). At the time of their study, retail prices for buprenorphine formulations (Subutex® and Suboxone®) were US$ 170–274/month. Effective treatment of drug dependence can translate into public benefit, and there are advocates for additional public funding of opioid treatment to include buprenorphine therapy (Becker, Fiellin, Merrill, Schulman, Finkelstein et al., 2008).

Conclusions

Prescription opioids remain safe and effective pharmacotherapies for surgical, traumatic, and malignant pain, and although controversial, are widely prescribed for chronic non-malignant pain. However, over the last decade marked increase in abuse of and addiction to prescription opioids has occurred. Opioid prescribing by physicians for pain has increased in medical offices and emergency rooms, and some of these appropriately treated patients develop addiction. Fortunately, for those who do develop addiction, opioid substitution with buprenorphine and medical management of iatrogenic addiction in office settings appears safe and efficacious.

Although the treatment of pain is better than the disease, the ethical imperatives of pain relief and therapeutic beneficence mandate development of analgesics with lower abuse liability, better methods to detect patients at risk for developing addiction, and improved treatments for patients who become addicted.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH P50 DA018179. The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance of Jayme Mulkey.

References

- Amass L, Ling W, Freese TE, Reiber C, Annon JJ, Cohen AJ, et al. Bringing buprenorphine-naloxone detoxification to community treatment providers: the NIDA Clinical Trials Network field experience. The American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:S42–66. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne JC, LaForge KS. Opioid dependence and addiction during opioid treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 2007;129:235–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DT, Moore BA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Sullivan LE, O’Connor PG, et al. Patient satisfaction with primary care office-based buprenorphine/naloxone treatment. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:242–245. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Merrill JO, Schulman B, Finkelstein R, Olsen Y, et al. Opioid use disorder in the United States: insurance status and treatment access. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellen DA, et al. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among US adults: Psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brands B, Blake J, Sproule B, Gourlay D, Busto U. Prescription opioid abuse in patients presenting for methadone maintenance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;73:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldiero RM, Parran TV, Jr, Adelman CL, Piche B. Inpatient initiation of buprenorphine maintenance vs. detoxification: can retention of opioid-dependent patients in outpatient counseling be improved? The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10550490500418989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carise D, Dugosh KL, McLellan AT, Camilleri A, Woody GE, Lynch KG. Prescription OxyContin abuse among patients entering addiction treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1750–1756. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.07050252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002–2004. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2005;6:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Yu E, Rothenberg JL, Kleber HD, Kampman K, et al. Injectable, sustained-release naltrexone for the treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:210–218. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1998;16:355–363. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Kunins HV, Roose RJ, Elam RT, Sohler NL. Barriers to obtaining waivers to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction treatment among HIV physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1325–1329. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0264-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A. Opioid-induced respiratory effects: new data on buprenorphine. Palliative Medicine. 2006;20:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WR, Johnson BD. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and diversion among street drug users in New York City. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWN (US Drug Abuse Warning Network) US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Drug Abuse Warning Network. 2005 from dawninfo.samhsa.gov/files/DAWN2k5ED.htm#Tab1. [PubMed]

- Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, O’Connor PG, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:365–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald MK, Johanson CE, Moody DE, Woods JH, Kilbourn MR, Koeppe RA, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2000–2009. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Reif S, Hodgkin D, Garnick DW, Merrick EL. Availability of addiction medications in private health plans. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MS. An exploratory study of OxyContin use among individuals with substance use disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(3):271–6. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10400613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo LP, Parran T, Jr, Johnson B, Kinsey W. Addiction: part II. Identification and management of the drug-seeking patient. American Family Physician. 2000;61:2401–2408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ, Knight JR, Wechsler H. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among U.S. college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:789–805. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF. Office-based buprenorphine treatment for opioid-dependent patients. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2004;12:321–338. doi: 10.1080/10673220490905688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JO, Jackson TR, Schulman BA, Saxon AJ, Awan A, Kapitan S, et al. Methadone medical maintenance in primary care. An implementation evaluation. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:344–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M, Kirchmayer U, Verster A. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006:CD001333. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001333.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzer IL, Eisenberg M, Terra M, MacVane C, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Treating opioid addiction with buprenorphine-naloxone in community-based primary care settings. Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5:146–150. doi: 10.1370/afm.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, et al. Primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment: comparison of heroin and prescription opioid dependent patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:527–530. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Pain Foundation. National Pain Awareness Campaign: Questions and Answers on Pain. 2007 from www.painconnection.org/NationalPainAwareness/Factsheet.pdf.

- Parran T., Jr Prescription drug abuse. A question of balance. The Medical Clinics of North America. 1997;81:967–978. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L, Portenoy RK, Katz NP, Kleinman L, et al. A new tool to assess and document pain outcomes in chronic pain patients receiving opioid therapy. Clinical Therapeutics. 2004;26:552–561. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299:70–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapeli P, Fabritius C, Alho H, Salaspuro M, Wahlbeck K, Kalska H. Methadone vs. buprenorphine/naloxone during early opioid substitution treatment: a naturalistic comparison of cognitive performance relative to healthy controls. BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Schnoll SH, Fong C, Maxwell C, Cleland CM, et al. Prescription opioid abuse among enrollees into methadone maintenance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables - Tables 4.1a-4.4a and 4.10a. 2004 from www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k4nsduh/2k4tabs/Sect4peTabs1to50.htm.

- SAMHSA, NSDUH. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) How Young Adults Obtain Prescription Pain Relievers for Nonmedical Use. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2005. 2005 from www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k6/getPain/getPain.htm.

- SAMHSA. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Washington, D.C: 2006. from www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k6nsduh/2k6Results.cfm#TOC. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Detailed Tables - Table 4.13b. 2006a from www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k6nsduh/tabs/Sect4peTabs1to16.htm.

- SAMHSA. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Detailed Tables - Table 1.1a. 2006b from www.oas.samhsa.gov/HSDUH/2k6NSDUH/tabs/Sect1peTabs1to46.htm.

- SAMHSA. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Detailed Tables - Table 5.2a. 2006c from www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k6nsduh/tabs/Sect5peTabs1to56.htm.

- Shirayama Y, Ishida H, Iwata M, Hazama GI, Kawahara R, Duman RS. Stress increases dynorphin immunoreactivity in limbic brain regions and dynorphin antagonism produces antidepressant-like effects. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;90:1258–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC. Characterizing the emerging population of prescription opioid abusers. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:208–212. doi: 10.1080/10550490600625624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Trier M, Brummett S, Gold ML, Dumontet R. Withdrawal from methadone maintenance. Impact of a tapering network support program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90006-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton A, McLeod C, Luckey B, Kissin WB, Sonnefeld LJ. SAMHSA/CSAT Evaluation of the Buprenorphine Waiver Program. SAMHSA (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration); 2006. from www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/ASAM_06_Final_Results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Moore BA, Chawarski MC, Pantalon MV, Barry D, O’Connor PG, et al. Buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in primary care is associated with decreased human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;35:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEDS. (US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) Treatment Episode Data Set 2005. 2005 from wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/teds05/TEDSAd2k5Index.htm.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Letter to Roxane Laboratories. 2001 Retrieved Feb 9, 2008, from http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/appletter/2001/20315S6LTR.PDF.

- Wasan AD, Correll DJ, Kissin I, O’Shea S, Jamison RN. Iatrogenic addiction in patients treated for acute or subacute pain: a systematic review. Journal of Opioid Management. 2006;2:16–22. doi: 10.5055/jom.2006.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedam EF, Bigelow GE, Johnson RE, Nuzzo PA, Haigney MC. QT-interval effects of methadone, levomethadyl, and buprenorphine in a randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: position statement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Shi YG, Woods JH, Watson SJ, Ko MC. Central kappa-opioid receptor-mediated antidepressant-like effects of nor-Binaltorphimine: behavioral and BDNF mRNA expression studies. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;570:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]