Abstract

Family reminiscing is a critical part of family interaction related to child outcome. In this study, we extended previous research by examining both mothers and fathers, in two-parent racially diverse middle-class families, reminiscing with their 9- to 12-year-old children about both the facts and the emotional aspects of shared positive and negative events. Mothers were more elaborative than fathers, and both mothers and fathers elaborated and evaluated more about the facts of positive than negative events, but there were no differences in parental reminiscing about the emotional aspects of these events. Fathers showed a more consistent reminiscing style across event and information type, whereas mothers seem to show a more nuanced style differentiated by topic. Most interesting, maternal elaborations and evaluations about the facts of negative events were related to higher child well-being, whereas paternal elaborations and evaluations about the emotional aspects of both positive and negative events were related to lower child well-being. Implications for the gendered nature of reminiscing are discussed.

Twenty years of research has established individual differences in the ways in which mothers reminisce with their preschool children that are related to multiple aspects of cognitive and socioemotional development (see Fivush, 2007; Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006, for reviews). Through parent-guided reminiscing, children learn the forms and functions of talking and thinking about the past; they learn how to organize and understand their experiences and the value of sharing these experiences with others (Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978). Early research established relations between maternal reminiscing style and children’s autobiographical memory skills; more recent research has extended these findings to show relations between maternal reminiscing style and children’s emotional understanding and regulation. To date, however, research has focused on mothers in dyadic reminiscing with their preschool children, and reminiscing has been examined as a more or less global construct in relation to child outcome. Thus, the overall goals of this study were to extend research on mother-child reminiscing to examine the role of reminiscing within the family as a whole with older children, who are developing more sophisticated cognitive and socioemotional skills, as well as to examine more specific relations between reminiscing and child well-being.

Individual differences in maternal reminiscing vary along a dimension of elaboration, with highly elaborative mothers talking a great deal about the past, asking many questions and providing richly detailed information, as well as confirming their child’s participation. In contrast, less elaborative mothers provide little contextual information about the event under discussion, tending to repeat the same questions over and over in an effort to get their children to recall a particular aspect of the event (see Fivush et al., 2006; Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Reese, 2002, for reviews). Thus, the hallmark of a highly elaborative reminiscing style is the frequent use of elaborations and confirmations, whereas the hallmark of a low-elaborative reminiscing style is the frequent use of repetitions. Importantly, preschool children of more elaborative mothers come to tell more richly detailed and coherent narratives about their own past, both in conversation with their mothers and with unfamiliar adults by the end of the preschool years (Bauer & Burch, 2004; Farrant & Reese, 2000; Fivush & Vasudeva, 2002; Flannagan, Baker-Ward, & Graham, 1995; Haden, 1998; Harley & Reese, 1999; Hudson, 1990; Leichtman, Pillemer, Wang, Koreishi, & Han, 2000; Low & Durkin, 2001; Peterson, Jesso, & McCabe, 1999; Welch-Ross, 1997, 2001).

Not surprisingly, when reminiscing, mothers and children not only focus on the facts of what happened, but also discuss emotional states and reactions. Reflecting on emotion theoretically allows the child to draw connections between how they felt in the past and their current emotions in ways that provide a sense of continuity of self (Fivush & Nelson, 2006; Lagattuta & Wellman, 2002), as well as providing a sense of connection to others through shared emotional bonding (Fivush et al., 1996). Theorists have further argued that elaborated reminiscing, especially about emotionally difficult experiences, may help children better understand their emotional experiences in ways that facilitate emotional regulation and well-being (Bretherton & Mulholland, 1999; Thompson, 2000). Laible (2004a, b; Laible & Thompson, 2000) found that more highly elaborative maternal reminiscing about emotionally difficult events, such as conflicts and transgressions, was related to higher levels of emotional understanding and regulation in preschool children. In fact, elaborated maternal reminiscing was more predictive of preschool children’s emotional development than was mother-child conversations in a storybook reading context (Laible, 2004a), suggesting that reminiscing is a critical context for emotional socialization.

In previous research, maternal elaboration has been assessed across the entire narrative content. However, even when discussing emotionally charged events, mothers can elaborate on the facts of what happened (who, what, where, when) and/or the emotional aspects of the event (emotional states and reactions). Given the findings that maternal elaborative reminiscing style is related to children’s emotional development, it may be the case that elaborating on emotional aspects of the event is particularly helpful for children. That is, mothers who elaborate on emotional states and reactions may be teaching their children how to understand and regulate aversive emotion (e.g., Denham, 1998; Dunn, Bretherton, & Munn, 1987). On the other hand, there is also substantial evidence that focusing on emotion in a way that is ruminative and repetitive may be highly detrimental for adolescents and adults (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987). Thus, a focus on emotions during parent–child reminiscing may not be beneficial for children, and may even be detrimental if done in a repetitive, ruminative style.

In terms of focusing on the facts of the event, there is a growing body of research indicating that adults who are able to construct more coherent narratives of stressful events show higher levels of physical and psychological well-being (see Frattaroli, 2006; Pennebaker, 1997; Smyth, 1998, for reviews). This research suggests that the ability to put emotional experience in a coherent explanatory framework is beneficial, and therefore parents who elaborate on the facts of the event may be helping their children to create more coherent and explanatory narratives that are related to higher levels of well-being.

Elaborating on facts and emotions are obviously not mutually exclusive. Recent research by Sales and Fivush (2005; Fivush & Sales, 2006) suggests that mothers who express more emotion and provide more explanations in co-constructed narratives about stressful events have 8- to 12-year-old children with better coping skills and fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors. However, this research examined the content of mother-child reminiscing; it did not examine style, or the level of elaboration. Theoretically, parents can include factual or emotional information without elaborating on that information, or they can elaborate or repetitively dwell on facts or emotions. Thus, the first major objective of the current research was to examine reminiscing style for factual and emotional aspects of events separately, and to examine differential relations between reminiscing about facts and reminiscing about emotions on child well-being.

Moreover, we chose to examine preadolescent children, the period just before one of the most critical developmental periods—adolescence, a time of significant physical, cognitive, and social advances. At this age, children are developing more sophisticated narrative skills that allow them to integrate their experiences into an overarching life narrative (Habermas & Bluck, 2000; McAdams, 1992), and they are simultaneously developing more sophisticated emotional understanding (Harter, 1999) and emotional regulation skills (Compas & Epping, 1993) that allow them to engage in more self-regulated behavior. One of the most noteworthy developmental transitions concerns the parent–child relationship, specifically with regard to communication. Beginning in preadolescence, parents and adolescents report fewer expressions of positive emotion and more expressions of negative emotions during communications, which only increases throughout adolescence (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Thus, this is a critical period for studying parent-child reminiscing about emotional experiences.

Further, we extended previous research by examining both mothers and fathers. Both autobiographical narratives and emotional processing have been shown to differ by gender. As adults, females tell longer, more detailed, and more vivid autobiographical narratives than males, and these narratives are more emotionally rich (see Fivush & Buckner, 2003, for a review). Adult females also report experiencing a greater variety and intensity of emotions than do males (see Fischer, 2000, for an overview), and there is some suggestion that females are better able to regulate emotional experience than are males (Brody & Hall, 1993); thus, we might expect differences in mother-child compared to father-child reminiscing. There is limited research on father-child reminiscing, and the results seem to be inconclusive. Some studies find mothers to be more elaborative overall than fathers with both preschoolers and preadolescents (Bohanek et al., in press; Fivush, Brotman, Buckner, & Goodman, 2000), whereas other studies find few differences in level of elaboration between mothers and fathers (Reese & Fivush, 1993; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1996). Similarly, some studies find that mothers include more emotional content during reminiscing with preschoolers than do fathers (Fivush et al., 2000; Kuebli & Fivush, 1992), but other studies find no differences (Adams, Kuebli, Boyle, & Fivush, 1995). Reasons why mothers and fathers may or may not differ in reminiscing style may relate to multiple factors, including the kinds of events that are being discussed, the context in which reminiscing is taking place, and age of the child (see Fivush & Buckner, 2003, for a discussion).

In order to examine possible differences between mothers and fathers in this study, we asked the family as a whole to reminisce about events that the family shared together, although we only assessed emotional well-being for the preadolescent target child. We chose to examine the family as a whole because family systems theory suggests that parent-child interactions occur in a dynamic framework in which each family member influences the others (Kreppner, 2002). Thus, we were interested in examining how mothers and fathers might differ and/or complement each other when interacting as a family system. It should be noted that because we chose this way of assessing parents, we were not able to examine how the target child participated in the co-narration in a meaningful way because, for most families, multiple children were participating. Thus, the role of any individual child could not be determined, because parents are assumed to be scaffolding the narrative for all the children present. Obviously, then, we also could not examine how the gender of child might be related to these processes, because most parents were reminiscing with both daughters and sons simultaneously. However, we chose this strategy because this is the situation in which most family reminiscing occurs, with multiple family members engaged and participating, and we wanted to examine family reminiscing in as naturalistic a con- text as possible. We argue that a more complete understanding of how the family system as a whole reminisces will allow us to target future research in more theoretically meaningful ways.

Finally, we chose to examine how families reminisce about both emotionally positive and negative events. Much of the research on relations between maternal reminiscing and child well-being focuses on negative experiences because these are the kinds of experiences that require emotional regulation. However, it is also the case that mothers reminisce about positive and negative events somewhat differently; mothers include more negative emotion, and they focus more on causal explanations, when reminiscing about negative compared to positive events with children ranging from preschool to preteen (Ackil, Van Abbema, & Bauer, 2003; Sales, Fivush, & Peterson, 2003). Reminiscing about positive and negative experiences may serve different functions; reminiscing about positive events may help create a shared history that maintains emotional bonds through time (Fivush et al., 1996), whereas reminiscing about negative events may serve a more didactic function of teaching children how to understand and regulate aversive affect (Sales et al., 2003). Thus, we may see different patterns of reminiscing about positive and negative events, as well as differential relations between reminiscing about positive versus negative events and child well-being.

Thus, the overall goals of this study were to examine how mothers and fathers reminisce about the facts and emotions of both emotionally positive and negative experiences within the family context, and how this may be related to emotional well-being in preadolescent children. We asked middle-class two-parent families with at least one child between the ages of 9 and 12 years to reminisce about shared positive and negative events. It should be noted that we have conducted previous analyses on these narratives that examined the global process of family narrative interaction along dimensions of collaborative versus independent perspectives (Bohanek, Marin, Fivush, & Duke, 2006), as well as a detailed analysis of the emotional content of narratives about the negative events only (Marin, Bohanek, & Fivush, 2008). However, in these first analyses, we examined the family as a unit and did not differentiate between mothers and fathers. In addition, we examined relations between family narrative interactions and children’s self-esteem and self-concept.

In subsequent content analyses of the negative event narratives, we did examine mothers and fathers separately, but again, examined only those parts of the conversations focusing on emotion (Bohanek, Marin, & Fivush, 2008). Mothers who expressed and explained more emotion had adolescents with higher levels of well-being as assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), but fathers who expressed and explained more emotion had adolescents with lower levels of well-being. These findings create something of a paradox that we wanted to examine in more detail in this study. Thus, in the current study, we extended previous analyses by coding the entire narrative — both aspects focused on emotion but also aspects focused on narrating the facts of what happened—using the standard coding for parental reminiscing style examining elaborations, evaluations, and repetitions for mothers and fathers independently for both positive and negative events, and relating these dimensions to child well-being as assessed by the CBCL.

Because this was the first study in the literature to examine reminiscing style among the family as a whole, it was unclear whether mothers and fathers might differ from each other, but given previous research, we expected that if mothers and fathers did differ, it would be in the direction of mothers being more elaborative overall than fathers. However, we expected both mothers and fathers to elaborate more on the emotional aspects of negative rather than positive events as, in this context, a goal of reminiscing would focus on teaching the child about how to understand and regulate emotion. However, it was not clear how reminiscing about the emotional aspects of a negative event might be related to child well-being. On one hand, elaborated reminiscing about emotions might help children better understand and regulate emotion. On the other hand, more elaborative, and especially more repetitive, reminiscing about emotion may lead children to ruminate on emotion and thus be related to lower child well-being.

Method

Participants

As part of a larger study of family narrative interaction, 40 middle-class two-parent families, specifically targeting those with a child between the ages of 9 and 12 (M = 10.7), were recruited through school, summer camps and newspaper advertisements. There were 21 males and 19 females. No family had more than one child between the targeted ages. However, the number of children (older than 12 months) in each family ranged from one to five. Of the 40 target children, 10 were the only child, 30 had at least one sibling (11 males, 19 females), 13 had a second sibling (7 males, 6 females), 5 had a third sibling (1 male, 4 females), and only 1 target child had a fourth sibling (1 male). Of the 40 families, 33 were dual earners and 7 were single earners. Twenty-nine of the families self-identified as Caucasian, six as African or African-American, and five as mixed race. Thirty families were traditional nuclear families, eight were blended, and two were extended. Of those who responded, 17 mothers and 22 fathers completed a postgraduate degree, 13 mothers and 8 fathers completed college, 7 mothers and 6 fathers had some college education, and 1 father completed some high school. All parents signed informed consent and adolescents gave verbal assent to the procedures, as approved by the institutional review board. Families were paid $25, and children were given movie tickets.

Procedure

Families were visited in their homes by one of four research assistants (three females and one male) while all members were present. Families were told that the purpose of the study was to understand how families talk about the past. Specifically, families were asked to sit in a comfortable place in their house (usually the living room) and discuss one positive event and one negative event (counterbalanced across families) that the family had experienced together within the past 2 to 3 years. Families were asked to discuss the events in as natural a manner as possible. The research assistant sat unobtrusively in a corner or in another room. The conversations were tape recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Conversations ranged in length, with most families conversing for approximately 10–20 minutes per narrative.

Following the conversations, the mother filled out the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL was chosen to assess child behaviors because it is widely used in the clinical and developmental literatures to determine the presence or absence of internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalizing (e.g., acting out) problems in children. Internalizing and externalizing scores are calculated independently, with the responses from 32 items summed to create a total internalizing score, and the responses from 33 items summed to create a total externalizing score. Each item is scored from 0–2, with 0 indicating that the item is “not true” of the child, whereas a 2 indicates that the item is “very true or often true” of their child. For example, sample items reflective of internalizing problems include, “Feels worthless or inferior,” and, “Would rather be alone than with others,” and sample items reflective of externalizing problems include, “Gets in many fights,” and, “Swearing or obscene language.” Lower scores on either scale indicate less frequent internalizing or externalizing behaviors, and higher scores indicate more frequent/severe internalizing or externalizing behaviors.

As a measure of internal consistency, Achenbach (1991) calculated Cronbach’s alphas for each scale, with the internalizing scale α = .90 and the externalizing scale α = .93, which indicates strong internal consistency. As reported by Achenbach, overall 1-week test-retest reliability Pearson rs for the internalizing and externalizing scores are .89 and .93, respectively.

Coding

After narratives were transcribed and checked for accuracy, each narrative was divided into utterances. An utterance was defined as a proposition that contained a subject and verb, or the provision of a stand-alone confirmation (e.g., “Yeah” or, “uh-huh”) or negation (e.g., “No”). Each utterance was then coded in two ways; first, each utterance was coded as to whether it focused on emotional or factual aspects of the event, and then each utterance was coded for style (i.e., elaboration, evaluation, repetition). Thus, each utterance could be classified as an elaboration, evaluation, or repetition on either emotional or factual aspects of the event.

Focus

Two experienced coders read through the transcripts of the family narratives together and jointly identified the emotion talk within each narrative (see Bohanek et al., 2008; Marin et al., 2008). Any utterance that pertained to an emotional state or behavior was considered an emotional utterance. Note that the utterance did not have to contain an emotion word per se but had to be part of a conversation about an emotional state or reaction (i.e., all conversational turns referring to whether and why an event was sad whether or not an emotion word was used during that turn), rather than about the facts of what occurred during the event.

Reminiscing style

Each utterance was coded for style, adapted from the standard maternal reminiscing style coding scheme (Fivush & Fromhoff, 1988; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1993).

Elaborations: any statement or question that provides a new piece of information about an event or a particular aspect of the event (e.g., “Memaw and Granddad came over, and Daddy cooked hamburgers on the grill.”)

Repetitions: a family member makes a statement or question which repeats the exact content or the gist (non-verbatim) of their previous utterance (e.g., “We had fun didn’t we?” and in their following conversational turn, “We had fun.”)

Evaluations: Utterances that confirm or negate a family member’s previous utterance (e.g., Child: “Lions.” Mother: “Yes, lions is right.”)

Two researchers independently coded 19 narratives and achieved 89% agreement for inter-rater reliability across utterance type, 90% for elaborations (range from 88% to 94%), 88% for evaluations (range from 86% to 94%), and 100% for repetitions. The remaining narratives were then coded by one of the two researchers.

Results

Results are presented in four sections. We first describe the types of events the families discussed during the reminiscing task, and we then address differences in family reminiscing style by parent, event type, and narrative focus. The third section addresses consistency in reminiscing style between factual and emotional information, across positive and negative events, and between mothers and fathers. The fourth section presents relations between family reminiscing style and children’s adjustment on the CBCL.

Description of Events

Families were asked to select and discuss one positive and one negative event that they had shared together in the past year or so. There was little variability in the topics selected for positive events, with 77% of the narratives being about family vacations; 7% of families discussed the birth of a child, 7% discussed sporting events, 5% discussed visits with relatives, and 2% discussed family ceremonies. However, when asked to discuss a shared negative event, the content was much more variable; 30% of the families discussed the death of a family member or friend, 22% discussed illness or injury, 20% discussed the death of a pet, 20% discussed accidents or disasters, and 7% discussed other events, such as a family conflict, a move to a new city, and mishaps during a vacation.

Parental Gender Differences in Reminiscing Style

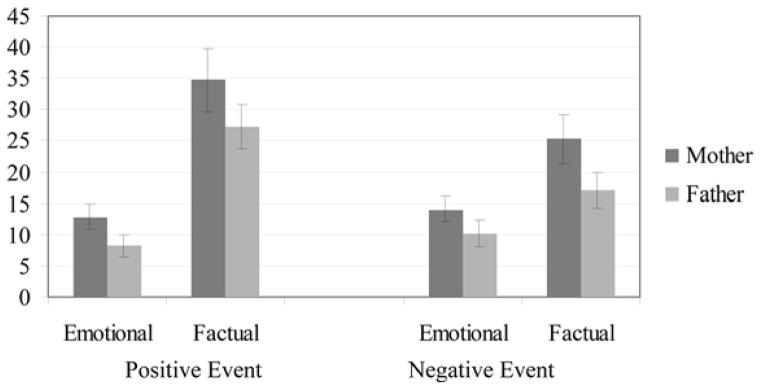

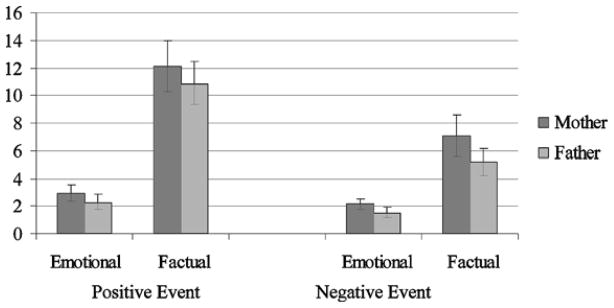

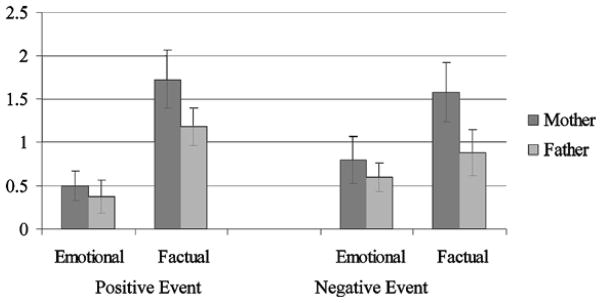

The first set of analyses examined differences in parental reminiscing style as a function of parent gender and event valence. We conducted a 2 (parent: mother, father) x 2 (event: positive, negative) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on each of the six utterance types separately (emotional and factual elaborations, emotional and factual evaluations, and emotional and factual repetitions) as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

Figure 1.

Mean number of emotional and factual elaborations for mothers and fathers within the positive and negative family narratives.

Figure 2.

Mean number of emotional and factual evaluations for mothers and fathers within the positive and negative family narratives.

Figure 3.

Mean number of emotional and factual repetitions for mothers and fathers within the positive and negative family narratives.

For elaborations, mothers contributed more emotional elaborations (M = 26.90, SD = 18.54) than fathers (M = 18.37, SD = 20.43) (F = 3.97, p = .05). Also, mothers contributed more factual elaborations (M = 59.93, SD = 44.96) than fathers (M = 44.35, SD = 33.29) (F = 6.57, p < .05). For evaluations, there were more nonemotional evaluations within the positive event (M = 23.00, SD = 19.09) than the negative event (M = 12.28, SD = 13.72) (F = 24.65, p < .001), but there were no differences in emotional evaluations between the two events (F = 2.62, p > .05). Finally, for repetitions, mothers contributed more factual repetitions (M = 3.30, SD = 3.38) than did fathers (M = 2.05, SD = 2.26) (F = 5.60, p < .05). However, there were no differences in parental contributions for emotional repetitions (F = .62, p > .05).

We note that in language data in general, and narrative data in particular, there remains a controversy over whether frequency or proportions are the correct metric. Along with others, we argue that frequencies are the appropriate metric because sheer amount of a certain type of language has been shown to be a more critical variable in predicting child outcome than proportion (Farrant & Reese, 2000; Fivush, 1998; Reese et al., 1993; Wang, 2001; Wang, 2006). For example, frequency, and not proportion, of variety of parental vocabulary, and frequency, and not proportion, of maternal conversation-eliciting strategies predicts child language outcome (Hoff-Ginsberg, 1986; Naigles & Hoff-Ginsberg, 1995), and frequency of maternal elaboration during reminiscing predicts child language and narrative outcome (Peterson et al., 1999; Reese, 1995) as well as emotional development (Laible, 2004a, 2004b). Still, we acknowledge that proportion may provide additional information. Therefore, we reanalyzed these data using proportions, calculated as the parental frequency of each specific utterance type over the total number of utterances in the narrative (e.g., number of maternal factual elaborations over total number of utterances). ANOVAs on these proportions revealed the same pattern of significant effects as with the frequency data (all analyses available from the first author).

Thus, overall, mothers elaborate and repeat more than fathers, but there are no parental differences in evaluations. Parents also evaluate more about the factual aspects of positive than negative events, but there are no event differences in evaluations for the emotional aspects.

Consistency in Family Reminiscing

Consistency between facts and emotions

We examined consistency of style in multiple ways. Our first question was whether individual parents were consistent in their style across the factual and emotional content of reminiscing. Pearson correlations were conducted on the elaborations, repetitions, and evaluations between the factual and emotional utterances within the positive and negative events independently, as shown in the top half of Table 1. Based on recent arguments in the literature about the interpretation of correlational data, we have chosen to focus on the effect size (see Kine, 2004; Vacha-Haase, Nilsson, Reetz, Lance, & Thompson, 2000; Vacha-Haase & Thompson, 2004, for discussions of this issue). Traditionally, small effect sizes are those around .10 (Aron & Aron, 1999; Cohen, 1992). Thus, we provide information about conventional levels of statistical significance as well as cautiously interpreting correlations of small effect sizes (correlations of about .30) with significance levels of p < .10.

Table 1.

Consistency of Elaborative Style: Correlations Within and Across Emotional and Factual Aspects of Positive and Negative Events for Mothers and Fathers (all N=40)

| Within events: factual to emotional

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive event

|

Negative event

|

|||

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | |

| Elaborations | .30+ | .37* | −.09 | .32* |

| Evaluations | .43** | .50** | .33* | .37* |

| Repetitions | .38* | .29+ | .16 | .00 |

| Across events: positive to negative

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional

|

Factual

|

|||

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | |

| Elaborations | .05 | .46** | .26 | .32* |

| Evaluations | .13 | .58** | .73** | .62** |

| Repetitions | .07 | −.06 | .26 | .08 |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Within the positive event, parents were very consistent in their elaborative style, in that both mothers and fathers who used more factual elaborations, repetitions, and evaluations also used more emotional elaborations, repetitions, and evaluations. Within the negative event, mothers and fathers were consistent in their use of evaluations across factual and emotional aspects of negative events, and fathers who used more factual elaborations also used more emotional elaborations. Mothers were not consistent in elaborating on facts and emotions for the negative events, and neither parent was consistent in using repetitions.

Consistency between positive and negative events

Our second question addressed consistency across positive and negative events for factual information and for emotional information separately for each parent. As can be seen in the bottom part of Table 1, fathers were consistent in their use of elaborations and evaluations for both factual and emotional information across the positive and negative events. Mothers, in contrast, were only consistent in their use of evaluations about factual material across the two events. Neither parent was consistent in their use of repetitions.

Consistency between parents

The third set of analyses addressed whether mothers and fathers were consistent with each other in their reminiscing style. Thus, we calculated Pearson correlations between mothers and fathers on the emotional utterances and the factual utterances within the positive and negative events (see Table 2). Within the positive event, for the factual utterances, mothers and fathers were consistent in elaborations, repetitions, and evaluations, but for emotional utterances, mothers and fathers were only consistent in their use of evaluations, not elaborations or repetitions. A similar pattern emerged for the negative event; for factual utterances, mothers and fathers were consistent in elaborations and evaluations but not repetitions. For the emotional utterances, mothers and fathers were again consistent in their use of evaluations but not elaborations or repetitions.

Table 2.

Consistency Across Mothers and Fathers Within Positive and Negative Events (all N=40)

| Positive event | Negative event | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Emotional | Factual | Emotional | Factual | |

| Elaborations | .16 | .51** | .12 | .55** |

| Evaluations | .38* | .59** | .35* | .56** |

| Repetitions | .19 | .29+ | −.05 | .17 |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Summary

Overall, fathers were more consistent in their reminiscing style than were mothers. Fathers were consistent in elaborating and evaluating on facts and emotions within both positive and negative events, as well as consistent in elaborating and evaluating across positive and negative events. Mothers, in contrast, were consistent in their evaluations of facts and emotions within both positive and negative events and across positive and negative events, but there was little consistency in their elaborations. Neither mothers nor fathers were very consistent in their use of repetitions. Finally, mothers and fathers showed similar styles to each other when reminiscing about the factual aspects of both positive and negative events, but they were only consistent in the extent to which they used evaluations, not elaborations or repetitions, when reminiscing about the emotional aspects of events. Thus, evaluations emerged as the most consistent aspects of parental reminiscing style across event type, narrative focus, and parent.

Family Reminiscing and Child Adjustment

Our final analyses were designed to determine the relations between parental elaborative style and children’s adjustment. Thus, we calculated Pearson correlations between elaborations, repetitions, and evaluations for the emotional and factual narrative utterances within the positive and negative events and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors as measured by the CBCL (see Table 3). For the positive events, there were virtually no relations between parental utterances and child well-being. Only 2 of 24 correlations were of at least a small effect size.

Table 3.

Relations between children’s adjustment and parental elaborative style (all N=40)

| Mothers

|

Fathers

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | External | Internal | External | |

| Positive Events | ||||

| Emotional | ||||

| Elabs | .09 | −.07 | .06 | .32* |

| Evals | .06 | .04 | .00 | .33* |

| Reps | −.20 | −.07 | −.08 | .23 |

| Factual | ||||

| Elabs | .00 | −.06 | .03 | .27 |

| Evals | −.14 | .01 | .06 | .19 |

| Reps | −.10 | −.13 | −.04 | .17 |

| Negative Events | ||||

| Emotional | ||||

| Elabs | .14 | .01 | .29+ | .20 |

| Evals | −.18 | −.09 | .19 | .41** |

| Reps | .14 | .07 | .42** | .39* |

| Factual | ||||

| Elabs | −.07 | −.30+ | −.26 | −.23 |

| Evals | −.30+ | −.26 | −.19 | −.15 |

| Reps | −.06 | −.28+ | −.18 | −.07 |

p<.10.

p<.05.

p<.01.

For the negative events, 7 of 24 correlations, or 30%, were of at least a small effect size. Mothers who contributed more factual elaborations and repetitions had children with fewer externalizing behaviors, and mothers who contributed more factual evaluations had children with fewer internalizing behaviors. In addition, fathers who contributed more emotional elaborations and repetitions had children with more internalizing behaviors, and fathers who contributed more emotional repetitions and evaluations had children with more externalizing behaviors.

Because there were multiple relations between parental utterances and child well-being for the negative events, we further examined the differential effects of parental scaffolding within these events only, in a series of regression analyses with parental utterances as the predictor variables and child well-being as the outcome variable. Because we had no a prior assumptions to order entry of the predictor variables, we entered variables simultaneously.

The first analyses examined elaborations; maternal factual elaborations, maternal emotional elaborations, paternal factual elaborations, and paternal emotional elaborations were entered as predictor variables, and child internalizing behavior was the outcome variable. The overall model was significant, F(4, 34) = 2.68, p < .05. Both paternal elaboration about the emotional aspects of the event, t = 2.67, β = .43, p < .01, and factual aspects of the event, t = 2.47, β = .48, p < .05, were significant predictors, indicating that fathers who elaborated more about both the factual and emotional aspects of the negative event had children with higher levels of internalizing behaviors. For externalizing behaviors, the overall model was not significant.

The second analyses examined evaluations; maternal factual evaluations, maternal emotional evaluations, paternal factual evaluations, and paternal emotional evaluations were entered as predictor variables. The model with internalizing behaviors as the outcome variable was not significant, but the model with externalizing behaviors as the outcome variable was significant, F(4, 34) = 3.87, p < .01. Paternal emotional evaluations was a significant predictor, t = 3.49, β = .62, p < .001, and paternal factual evaluations approached significance, t = 1.72, β = .34, p = .09, indicating that fathers who provided more evaluations about the emotional aspects of negative events, and to some extent about the factual aspects of negative events, had children with higher levels of externalizing behaviors.

Finally, the third analysis examined repetitions; maternal factual repetitions, maternal emotional repetitions, paternal factual repetitions, and paternal emotional repetitions were entered as predictor variables. The model with internalizing behaviors as the outcome variable approached significance, F(4, 34) = 2.52, p =.06, and paternal emotional repetition was significant, t = 2.80, β = .18, p < .01. The model with externalizing behaviors as the outcome variable was significant, F(4, 34) = 2.53, p < .05, and again, paternal emotional repetition was the only significant predictor, t = 2.44, β = .37, p < .05, indicating that fathers who repeat more when reminiscing about the emotional aspects of a negative event have children with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

Overall, then, the regression analyses indicate that higher paternal involvement in reminiscing about negative events is consistently related to lower child well-being, especially when focused on the emotional aspects of the event. Fathers who elaborate, evaluate, and repeat when focused on emotion have children with higher levels of both internalizing and externalizing behaviors. When focused on facts, fathers who elaborate more have children with higher levels of internalizing behaviors, and fathers who evaluate more have children who show higher levels of externalizing behaviors. Although mothers who elaborate and repeat more about the facts of negative events have children with higher well-being in the first-order correlations, maternal utterances were not significant predictors in any of the regression analyses.

Discussion

In this study, we extended previous literature on maternal reminiscing style in several ways: we examined mothers and fathers reminiscing as a family about both positive and negative events, as well as about both emotional and factual aspects of those events, with preadolescent children, and we examined relations to child well-being. Overall, we found that mothers were more elaborative than fathers, and both parents were more evaluative when reminiscing about the factual aspects of positive compared to negative events, but not about the emotional aspects of these events. Fathers were also consistent in their reminiscing style for both elaborations and evaluations across factual and emotional information and across both positive and negative events. Mothers, in contrast, were consistent in their use of evaluations across event valence and type of information, but not in their use of elaborations. Related to this finding, mothers and fathers were consistent with each other in their use of evaluations across event and information type, but were consistent in their level of elaboration only for factual aspects of positive and negative events. Finally, maternal elaborations and evaluations on the factual aspects of a negative event were related to higher child well-being, whereas paternal elaborations, evaluations, and repetitions of the emotional aspects, and to some extent the factual aspects, of negative events, were related to lower child well-being.

That mothers are generally more elaborative than fathers confirms previous findings that, when gender differences emerge in reminiscing, females are more elaborative than males beginning at the end of the preschool years and throughout adulthood (see Fivush & Buckner, 2000, for a review). Specific to parents, again when differences emerge, mothers have been found to be more elaborative than fathers (Bohanek et al., 2008; Fivush et al., 2000). Here, we extend these findings to reminiscing among the whole family; when mothers and fathers are reminiscing together with their children, mothers are again more elaborative. Higher levels of maternal compared to paternal elaboration are consistent with the idea that one of the roles that mothers play is family historian or “kin-keeper” (Rosenthal, 1985), helping to ensure that the family has a shared set of memories that unite them through time. This sense of shared history serves to create and maintain family relations and family identity in the present (Pratt & Fiese, 2004).

Intriguingly, although mothers are generally more elaborative than fathers, they seem to be less consistent in their reminiscing style than fathers. Fathers’ consistency in their level of elaboration and evaluation across positive and negative events, and across factual and emotional aspects of those events, might suggest that fathers are not tuning their reminiscing to the specific topic. Mothers, in contrast, may be more sensitive to the topic, and adjust their reminiscing style accordingly. It should be noted, however, that previous research has suggested that mothers are consistent in their level of elaboration across positive and negative events when reminiscing in dyads with their preschool children (Sales et al., 2003). That we found consistency in maternal evaluations but not elaborations suggests that evaluations may play an increasingly important role in defining reminiscing style as children grow older and develop more sophisticated memory and language skills that allow them to participate to a greater extent in co-constructing narratives. As children participate more in family narratives, maternal elaborations may no longer be as critical in eliciting and maintaining children’s participation, but evaluations would still play this role, by confirming and validating children’s contributions. Alternatively, in the more complex family reminiscing studied here, with two parents and multiple children co-constructing the narrative, the parental scaffolding necessary may be more complex. This may lead to mothers’ adjustments in level of elaborations, but consistency in evaluations as a mechanism to validate contributions creating a collaboratively constructed narrative.

Related to this finding, although mothers were not consistent in their level of elaboration across type of event and type of information, mothers and fathers were reasonably consistent with each other in their level of elaboration, especially when reminiscing about the factual aspects of events, suggesting that there may be a family style of reminiscing (see also Bohanek et al., 2006; Sameroff & Fiese, 1999). However, when reminiscing about emotional aspects of events, only evaluations emerged as consistent across parents, again suggesting that evaluations are critical in defining family reminiscing style.

Turning to the type of information focused on, both mothers and fathers evaluated the facts of positive events more than negative events but evaluated the emotional aspects of positive and negative events to the same extent. We had predicted that parents would reminisce more about the emotional aspects of negative rather than positive events, as negative events create a problem to be solved. That we did not find this suggests that the emotional aspects of positive events may be just as important as the emotional aspects of negative events, although most likely for different reasons. Moreover, parents elaborated and evaluated more about the factual aspects of positive rather than negative events, suggesting that families create richer, more detailed narratives of shared positive rather than negative events. Previous research on differences in length and elaboration between positive and negative co-constructed narratives has been mixed. In research in which the negative event is the target of investigation (e.g., a natural disaster or injury as compared to a non-specified positive event; e.g., Ackil et al., 2003; Sales et al., 2003), negative narratives are longer than positive narratives, but when comparisons are made between family-selected negative and positive events, there are either no differences in narrative length (Burch, Austin, & Bauer, 2004), or the positive narrative is longer than the negative narrative (Wang & Fivush, 2005). One reason why families may engage in highly elaborated reminiscing about shared positive events is that these kinds of events serve to create and maintain emotional bonds through time (Fivush et al., 1996), which may help to create a family identity (Fivush, Bohanek, & Duke, 2008; Sameroff & Fiese, 1999).

Perhaps the most surprising findings were the relations between parental reminiscing and child well-being. Although there were no discernable relations between parental scaffolding during reminiscing and child well-being for the positive events, maternal elaborations and evaluations on the factual aspects of negative events are related to higher levels of child well-being. Research with preschoolers has shown that maternal elaboration about emotionally difficult events is related to higher levels of emotional regulation (Laible, 2004a,b), perhaps because negative events create a problem and heighten negative affect that needs to be resolved. In examining reminiscing style for the emotional and factual aspects of events separately in this study, our findings suggest that mothers who help to create a more coherent framework for understanding when, where, what, and how a negative event happened may be more associated with higher emotional regulation than mothers who elaborate and evaluate specifically on the emotion. In support of this interpretation, Sales and Fivush (2005) found that mothers who use more explanations when discussing stressful events have children with higher levels of emotional well-being. Thus, it seems that creating a coherent narrative account of what happened may be more related to well-being than focusing on emotional states and reactions.

In contrast, paternal elaborations, evaluations, and repetitions on the emotional aspects of negative events, and to a lesser extent the factual aspects of negative events, are related to lower child wellbeing. We must put this in context of previous findings on this dataset. Previous microcoding of just the emotional content of these conversations indicated that families that, as a whole, expressed and explained emotion when reminiscing about negative events are related to higher self-esteem and social competence (Marin et al., 2008), and when divided by gender, maternal expressions and explanations of emotions are related to higher child emotional well-being, but paternal expressions and explanations of emotions are related to lower child well-being (Bohanek et al., 2008). Here, we extend these results in finding that maternal elaborations and evaluations on the factual aspects of events are related to higher well-being, but paternal elaborations, evaluations, and repetitions of emotional aspects of negative events are related to lower child well-being.

This is a counterintuitive finding and begs some explanation. One possibility is that mothers may be helping their children to create coherent, detailed narratives of what happened, which is beneficial, but fathers may simply be focusing and ruminating on emotions, which may be detrimental. We emphasize here that the same child who scores high on well-being is simultaneously related to higher levels of maternal elaboration and evaluation of factual information and lower levels of paternal elaboration, evaluation, and repetition of emotional information. As the regression analyses indicate, when mothers and fathers are considered simultaneously, the variance that fathers account for in predicting child well-being is greater than the variance that mothers account for in this conversational context in which the family as a whole is reminiscing together.

We speculate that a possible reason for this seemingly odd finding is the context of reminiscing. Past research has established that mothers are typically the “family historians” and are responsible for integrating important family happenings and milestones into an ongoing narrative of family life (McDaniel, 1999; Sherman, 1990; Wamboldt & Reiss, 1989). Further, they are also often responsible for the “emotion work” in the household (Hochschild, 1979). This may be particularly important as children get older, because the preadolescent and adolescent period marks a transition in the parent-child relationship, and research suggests that this transition may be different for mothers and fathers (Parke, 2004). Both sons and daughters report being closer to their mothers than to their fathers (LeCroy, 1988), and mothers and fathers may play differing roles in their children’s lives during this time. Specifically, children report asking their mothers for more emotional support, whereas fathers are often seen as a source of information and material support (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Thus, in the context of reminiscing about specifically emotional events, fathers who focus on emotions may be at odds with their canonical role within the family. It is also important to consider the developmental age of the children in the present study as we interpret these findings. Particularly as children transition into adolescence and identity becomes a primary developmental task, particular expressions of gendered behavior may become more salient (McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003).

Also, of course, our data are correlational. It is possible that children who display more behavior problems, for whatever reason, have fathers who then focus more on emotions when reminiscing as a way of addressing these behaviors. Examining these processes at one point in time does not allow a more sophisticated analysis of how these processes unfold developmentally, or how the parent-child relationship evolves in a dialectical fashion, each influencing the others’ emerging behaviors. What we do see by examining the family as a whole is that patterns of dyadic behaviors between mothers and children and fathers and children may be different than the behaviors we see when the family interacts as a unit (Kreppner, 2002). Longitudinal research with mothers and preschoolers has suggested that direction of effect is from maternal reminiscing to child outcome (see Fivush et al., 2006, for a full discussion of this issue), but as children grow older and develop more differentiated and complex relationships with each parent, these patterns may also change. Future research must take this possibility into account, and longitudinal research should be conducted in such a way that causal modeling can be conducted.

Finally, although we had a good size and quite diverse sample for this type of research, we are limited in many other ways. Because we were interested in pursuing ideas within family systems theory, we examined the family as a unit, and we only included families with two opposite sex parents. Clearly, alternative family structures, as well as other cultures, must be investigated. Second, because we were interested in the family as a unit, we included all children living in the house in the family narratives, not just the preadolescent target child. Thus, aspects of parents’ reminiscing style may have been more directed at older or younger siblings, and we could not examine the target child’s participation in a meaningful way. As discussed in the introduction, we chose this strategy in order to better investigate how family reminiscing may occur in more naturalistic settings, when multiple members of the family are present and engaged. Now that we have these data, future research needs to systematically investigate how family reminiscing varies by participants, for example, both parents together reminiscing with a single one of their children, each parent independently with their preadolescent child, and so on. These combined comparisons would allow us to better understand how and when reminiscing about facts and emotions about positive and negative events are beneficial or, possibly, detrimental, and would further allow a more nuanced understanding of how gender of parent and gender of child might influence the reminiscing process.

Still, this first step in examining reminiscing style within the family as a whole has yielded interesting results. Overall, mothers are more elaborative than fathers, although maternal reminiscing style is also more tuned to the content of the narrative than is paternal reminiscing style. Evaluations may emerge in later childhood as a more critical component of reminiscing style. Especially as children become older, parental confirmations and validations of what children contribute may be more important than working to elicit information more generally. Finally, and most intriguing, mothers who help their preadolescent children create elaborated, coherent narratives of the facts of what happened concerning a stressful event have children with higher levels of well-being. In contrast, fathers who elaborate and evaluate on the emotional aspects of both negative and positive experiences have preadolescent children with greater behavior problems. These findings confirm that reminiscing is a gendered activity; the gendered values and meanings placed on this activity within the home will play a substantial role in how children come to interpret and integrate parental reminiscing style into their own understanding of highly emotional events.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Sloan Foundation Center for Myth and Ritual in American Life at Emory University, while the second and fourth authors were graduate fellows of the center.

Contributor Information

Robyn Fivush, Emory University.

Kelly Marin, Manhattan College.

Kelly McWilliams, Emory University.

Jennifer G. Bohanek, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the cross-informant program for the CBCL=4-18, YSR and TRF. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ackil JK, Van Abbema DL, Bauer PJ. After the storm: Enduring differences in mother-child recollections of traumatic and non-traumatic events. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2003;84:286–309. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0965(03)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams S, Kuebli J, Boyle PA, Fivush R. Gender differences in parent- child conversations about past emotions: A longitudinal investigation. Sex Roles. 1995;33:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Aron E. Statistics for psychology. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Burch MM. Developments in early memory: Multiple mediators of foundational processes. In: Lucariello JM, Hudson JA, Fivush R, Bauer PJ, editors. The development of mediated mind: Sociocultural context and cognitive development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Fivush R, Zaman W, Thomas-Lepore C, Merchant S, Duke MP. Narrative interaction in family dinnertime conversations: Relations to child well- being. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0031. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Marin K, Fivush R. Family narratives, self, and gender in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek JG, Marin KA, Fivush R, Duke MP. Family narrative interaction and children’s sense of self. Family Process. 2006;45:39–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Mulholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relation- ships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Hall JA. Gender and emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Burch MM, Austin J, Bauer PJ. Understanding the emotional past: Relations between parent and child contributions in negative and non-negative events. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;89:276–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Epping JE. Stress and coping in children and families: Implications for children coping with disaster. In: Saylor CF, editor. Children and disasters: Issues in clinical child psychology. New York: Springer; 1993. pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Emotional development in young children. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Bretherton I, Munn P. Conversations about feeling states between mothers and their young children. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Farrant K, Reese E. Maternal style and children’s participation in reminiscing: Stepping stones in children’s autobiographical memory development. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2000;1:193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Sameroff A, Grotevant HD, Wamboldt FS, Dickstein S, Fravel DL, et al. The stories that families tell: Narrative coherence, narrative interaction, and relation- ship beliefs. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64:1–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AH. Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R. The stories we tell: How language shapes autobiography. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1998;12:483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R. Owning experience: Developing subjective perspective in autobiographical narratives. In: Moore C, Lemmon K, editors. The self in time: Developmental perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001. pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R. Maternal reminiscing style and children’s developing understanding of self and emotion. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2007;35:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Bohanek JG, Duke M. The intergenerational self: Subjective perspective and family history. In: Sani F, editor. Individual and collective self-continuity. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman MA, Buckner JP, Goodman SH. Gender differences in parent-child emotion narratives. Sex Roles. 2000;42:233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Buckner JP. Gender, sadness, and depression: The development of emotional focus through gendered discourse. In: Fischer AH, editor. Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Buckner JP. Constructing gender and identity through autobiographical narratives. In: Fivush R, Haden C, editors. Autobiographical memory and the construction of a narrative self: Developmental and cultural perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Fromhoff FA. Style and structure in mother-child conversations about the past. Discourse Processes. 1988;11:337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Haden C, Reese E. Remembering, recounting, and reminiscing: The development of autobiographical memory in social context. In: Rubin DC, editor. Remembering our past: Studies in autobiographical memory. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Haden CA, Reese E. Elaborating on elaborations: Role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development. 2006;77:1568–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Nelson K. Parent-child reminiscing locates the self in the past. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2006;24:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Sales JM. Coping, attachment, and mother-child reminiscing about stressful events. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Vasudeva A. Remembering to relate: Socioemotional correlates of mother-child reminiscing. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2002;3:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan D, Baker-Ward L, Graham L. Talk about preschool: Patterns of topic discussion and elaboration related to gender and ethnicity. Sex Roles. 1995;32:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:748–769. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden CA. Reminiscing with different children: Relating maternal stylistic consistency and sibling similarity in talk about the past. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:99–114. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley K, Reese E. Origins of autobiographical memory. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1338–1348. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology. 1979;85:551–575. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff-Ginsberg E. Function and structure in maternal speech: Their relation to the child’s development of syntax. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JA. The emergence of autobiographic memory in mother-child conversation. In: Fivush R, Hudson JA, editors. Knowing and remembering in young children. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 166–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kine R. Beyond significance testing: Reforming data analysis methods in behavioral research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner K. Retrospect and prospect in psychological study of families as systems. In: McHale JP, Grolnick WS, editors. Retrospect and prospect in psychological study of families as systems. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuebli J, Fivush R. Gender differences in parent-child conversations about past emotions. Sex Roles. 1992;27:683–698. [Google Scholar]

- Lagattuta KH, Wellman HM. Thinking about the past: Early knowledge about links between prior experience, thinking, and emotion. Child Development. 2001;72:82–102. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Mother-child discourse surrounding a child’s past behavior at 30 months: Links to emotional understanding and early conscious development at 36 months. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004a;50:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Mother-child discourse in two contexts: Links with child temperament, attachment security, and socioemotional competence. Developmental Psychology. 2004b;40:979–992. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laible DJ, Thompson RA. Mother-child discourse, attachment security, shared positive affects, and early conscience development. Child Development. 2000;71:1424–1440. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCroy C. Parent-adolescent intimacy: Impact on adolescent functioning. Adolescence. 1988;23:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichtman MD, Pillemer DB, Wang Q, Koreishi A, Han JJ. When baby Maisy came to school: Mothers’ interview styles and preschoolers’ event memories. Cognitive Development. 2000;15:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Low J, Durkin K. Individual differences and consistency in maternal talk style during joint story encoding and retrospection: Associations with children’s long-term recall. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marin KA, Bohanek JG, Fivush R. Positive effects of talking about the negative: Family narratives of negative experiences and preadolescents’ perceived competence. Journal of Research in Adolescence. 2008;18:573–593. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. Unity and purpose in human lives: The emergence of identity as a life story. In: Zucker RA, Rabin AI, Aronoff J, Frank SJ, editors. Personality structure in the life course: Essays on personology in the Murray tradition. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1992. pp. 323–375. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SG. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Arizona State University; 1999. It’s bedlam in this house!: Investigating subjective experiences of family communication during holiday celebrations. [Google Scholar]

- McHale S, Crouter AC, Whiteman SD. The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2003;12:125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR, Hoff-Ginsberg E. Input to verb learning: Evidence for the plausibility of syntactic bootstrapping. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:827–837. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K, Fivush R. The emergence of autobiographical memory: A social-cultural developmental theory. Psychological Review. 2004;111:486–511. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:259–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fathers, families, and the future: A plethora of plausible predictions. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:456–470. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Opening up. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Jesso B, McCabe A. Encouraging narratives in preschoolers: An intervention study. Journal of Child Language. 1999;26:49–67. doi: 10.1017/s0305000998003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MW, Fiese BH. Family stories and the life course: Across time and generations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E. Predicting children’s literacy from mother-child conversations. Cognitive Development. 1995;10:381–405. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E. Social factors in the development of autobiographical memory: The state of the art. Social Development. 2002;11:124–142. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Fivush R. Parental styles of talking about the past. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:596–606. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Haden CA, Fivush R. Mother-child conversations about the past: Relationships of styles and memory over time. Cognitive Development. 1993;8:403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Haden C, Fivush R. Mothers, fathers, daughters, sons: Gender differences in autobiographical reminiscing. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 1996;29:27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal CJ. Kin keeping in the familial division of labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1985;47:965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Fivush R. Social and emotional functions of mother-child reminiscing about stressful events. Social Cognition. 2005;23:70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Fivush R, Peterson C. Parental reminiscing about positive and negative events. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2003;4:185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Fiese BH. Narrative connection in the family context: Summary and conclusions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64:105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman MH. Family narratives: Internal representations of family relationships and affective themes. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 1998;66:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silk JS. Parenting adolescents. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. The legacy of early attachments. Child Development. 2000;71:145–152. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase T, Nilsson JE, Reetz DR, Lance TS, Thompson B. Reporting practices and APA editorial policies regarding statistical significance and effect size. Theory & Psychology. 2000;10:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase T, Thompson B. How to estimate and interpret various effect sizes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, Reiss D. Defining a family heritage and a new relationship identity: Two central tasks in the making of a marriage. Family Processes. 1989;28:317–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1989.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Qi. Did you have fun? American and Chinese mother-child conversations about shared emotional experiences. Cognitive Development. 2001;16:693–715. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Qi. Relations of maternal style and child self-concept to autobiographical memories in Chinese, Chinese immigrant, and European-American 3-year olds. Child Development. 2006;77:1794–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Fivush R. Mother-child conversations of emotionally salient events: Exploring the functions of emotional reminiscing in European-American and Chinese families. Social Development. 2005;14:473–495. [Google Scholar]

- Welch-Ross M. Mother-child participation in conversations about the past: Relations to preschoolers’ theory of mind. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:618–629. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch-Ross M. Personalizing the temporally extended self: Evaluative self-awareness and the development of autobiographical memory. In: Moore C, Lemmon K, editors. The self in time: Developmental perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001. pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]