Abstract

Background and Purpose

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is secreted by intestinal I cells and regulates important metabolic functions. In pancreatic islets, CCK controls beta cell functions primarily through CCK1 receptors, but the signalling pathways downstream of these receptors in pancreatic beta cells are not well defined.

Experimental Approach

Apoptosis in pancreatic beta cell apoptosis was evaluated using Hoechst‐33342 staining, TUNEL assays and Annexin‐V‐FITC/PI staining. Insulin secretion and second messenger production were monitored using ELISAs. Protein and phospho‐protein levels were determined by Western blotting. A glucose tolerance test was carried out to examine the functions of CCK‐8s in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic mice.

Key Results

The sulfated carboxy‐terminal octapeptide CCK26‐33 amide (CCK‐8s) activated CCK1 receptors and induced accumulation of both IP3 and cAMP. Whereas Gq‐PLC‐IP3 signalling was required for the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion under low‐glucose conditions, Gs‐PKA/Epac signalling contributed more strongly to the CCK‐8s‐mediated insulin secretion in high‐glucose conditions. CCK‐8s also promoted formation of the CCK1 receptor/β‐arrestin‐1 complex in pancreatic beta cells. Using β‐arrestin‐1 knockout mice, we demonstrated that β‐arrestin‐1 is a key mediator of both CCK‐8s‐mediated insulin secretion and of its the protective effect against apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells. The anti‐apoptotic effects of β‐arrestin‐1 occurred through cytoplasmic late‐phase ERK activation, which activates the 90‐kDa ribosomal S6 kinase‐phospho–Bcl‐2‐family protein pathway.

Conclusions and Implications

Knowledge of different CCK1 receptor‐activated downstream signalling pathways in the regulation of distinct functions of pancreatic beta cells could be used to identify biased CCK1 receptor ligands for the development of new anti‐diabetic drugs.

Abbreviations

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CCK‐8s

sulfated cholecystokinin fragment 26‐33 amide

- p90RSK

90‐kDa ribosomal S6 kinase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- STZ

streptozotocin

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Bad |

| Bcl2 |

| GPCRs a |

| CCK1 receptor |

| Enzymes b |

| Epac |

| ERK |

| MEK |

| p90RSK, 90‐kDa ribosomal S6 kinase |

| PKA |

| PLC |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Carbamylcholine |

| CCK, cholecystokinin |

| CCK‐8s |

| GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 |

| H‐89 |

| Insulin |

| IP3 |

| Lorglumide |

| Rp‐cAMPS |

| U0126 |

| U73122 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a bAlexander et al., 2013a, 2013b).

Introduction

The gradual impairment of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus is often associated with increased insulin resistance, decreased pancreatic beta cell mass and beta cell function deficiency (Hanley et al., 2010; Rorsman and Braun, 2012). Gastrointestinal hormones, secreted by enteroendocrine cells, are vital components in the regulation of beta cell mass and insulin secretion (Baggio and Drucker, 2007; Koliaki and Doupis, 2011). To date, the regulatory mechanisms for some gastrointestinal hormones, such as glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) on pancreatic beta cells, have been extensively investigated, leading to the successful development of clinically useful compounds such as the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DDP‐4) inhibitor and the synthetic GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Ahren, 2009). Cholecystokinin (CCK) is another gastrointestinal hormone, which is secreted by the I cells in the mucosal epithelium of the small intestine or by neurons and is processed into several different forms in the endocrine system, including peptides of various lengths, for example, 58 to 39, 33, 22, 8 and 4 residues (Cantor and Rehfeld, 1989) The sulfated carboxy‐terminal octapeptide CCK‐8s is the shortest CCK peptide that retains most of biological activities of the parent molecule and is widely used to study CCK or CCK receptor functions (Rehfeld et al., 2007; Irwin et al., 2012, 2013).

Recently, studies have demonstrated that CCK or its derivatives stimulate insulin secretion in both mice and patients with type 2 diabetes (Karlsson and Ahren, 1992a; Ahren et al., 2000). In addition, CCK‐8s increased the beta cell mass in both obese mice and rats with streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetes (Kuntz et al., 2004; Lavine et al., 2010b). Conversely, insulin secretion was impaired in CCK‐deficient mice (Lo et al., 2011). All of these studies demonstrated that CCK is an important physiological regulator of many pancreatic beta cell functions.

Two types of GPCRs, CCK1 receptors and CCK2 receptors, are important mediators of the diverse physiological functions of CCK, which depend on the specific cellular context. Pancreatic beta cells primarily express CCK1 receptors whose selective antagonist L‐364,71 blocks the effects of CCK on insulin secretion (Karlsson and Ahren, 1992a). Moreover, Otsuka Long‐Evans Tokushima Fatty rats, characterized by hyperglycaemia and obesity, were found to lack CCK1 receptors and to display increased beta cell apoptosis (Takiguchi et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2008). These results suggest that CCK1 receptors are an essential component of pancreatic beta cell functions, and low MW compounds targeting CCK1 receptors can be considered for anti‐diabetic therapy.

Activation of CCK1 receptors in pancreatic acinar cells has been reported to couple to two different G proteins, Gq/11 or Gs, which generate the second messengers, inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and cAMP respectively (Dufresne et al., 2006). After activation, many GPCRs are phosphorylated by protein kinases and are associated with β‐arrestins including β‐arrestin‐1 and β‐arrestin‐2 (also termed arrestin2 and arrestin3 respectively) (Evron et al., 2014; Shukla et al., 2014). β‐Arrestins not only mediate receptor internalization but also initiate a second wave of signalling through scaffolding receptors to downstream signalling components, such as Src, ERK, JNK3, NF‐κB or PI3K/Akt (Xiao et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). The distinct signalling mediated by different G protein subtypes or arrestins introduces the concept of ‘biased agonism’, which is utilized to identify novel therapeutic reagents with fewer side effects than the natural ligands (Rajagopal et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2011; Whalen et al., 2011). For example, a biased agonist of the angiotensin AT1 receptor TRV120027 antagonizes G protein‐dependent signalling but activates various kinase pathways via β‐arrestin coupling, resulting not only in reduced arterial pressure but also preserving cardiac performance (Violin et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012). Although the involvement of β‐arrestin in CCK1 receptor signalling in pancreatic beta cells remains unknown, recent studies have demonstrated both G protein‐mediated and β‐arrestin‐mediated insulin secretion and beta cell mass expansion in vitro and in vivo (Sonoda et al., 2008; Broca et al., 2009; Quoyer et al., 2010). Therefore, exploring the biased signalling pathways of CCK1 receptors, particularly their functions in pancreatic beta cells, will provide a foundation for the design and use of novel CCK1 receptor ligands.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the downstream signalling of CCK1 receptors in pancreatic beta cells, particularly G protein signalling and β‐arrestin functions. We tested whether activation of CCK1 receptors stimulates the Gs or Gq/11 pathway by monitoring changes in the levels of the second messengers cAMP and IP3 in pancreatic beta cells and determining their contributions to insulin secretion. More importantly, we characterized the β‐arrestin‐1‐mediated pancreatic beta cell or islet function using small interfering RNA (siRNA)‐mediated knockdown and β‐arrestin‐1 knockout (β‐arrestin‐1−/−) mice. Our work demonstrates a previously unidentified mechanism of CCK1 receptor activation in pancreatic beta cells and suggests that biased agonism of CCK1 receptors can be further exploited to develop novel therapeutic agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Animal treatment

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Shandong University. Studies involving animals are described in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010) and the Concordat on Openness on Animal Research. A total of 250 animals were used in the experiments described here.

β‐Arrestin‐1−/− mice were provided by Dr Robert J. Lefkowitz, who authorized their use (Duke University), and wild‐type (WT) C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) (Wang et al., 2014). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Islet isolation and dispersed islets cells culture

Pancreatic islet cells from adult mice were isolated from adult mice and cultured as described previously (Dou et al., 2012). Briefly, adult mice weighing between 30 and 40 g were killed, by cervical dislocation and islets were collected by hand picking after collagenase P digestion for 10 to 13 minutes at 37°C (Dou et al., 2012, Yu et al., 2004). Freshly isolated islets were dispersed with Dispase II to prepare single beta cells (Dou et al., 2012, Yu et al., 2004). Primary beta cells were cultured in DMEM containing 5.5 mM glucose supplemented with 10% FBS (Victoria, Australia), 100 µg·mL‐1 streptomycin, and 100 U·mL‐1 penicillin at 37°C in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 and 95% air).

Cell culture

The murine beta cell line MIN6 was a generous gift from Debbie C. Thurmond (IUPUI, USA) and was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 25 mM glucose supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone Thermo Scientific, Scoresby, Victoria, Australia), 100 µg·mL‐1 streptomycin, 100 U·mL‐1 penicillin and 50 μM β‐mercaptoethanol at 37°C. HEK293 cells were from Dr. Robert J. Lefkowitz (Duke University) and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 µg·mL‐1 streptomycin, and 100 U·mL‐1 penicillin at 37°C.

Glucose tolerance test

Eight‐ to ten‐week‐old WT C57BL/6J or β‐arrestin‐1‐/‐ C57BL/6J mice were starved for 12 h the night before the experiments and then were injected i.p. with streptozotocin (STZ; 140 mg·kg‐1 body weight) in 0.1 mM citrate‐buffered saline the next morning. During the following 72 h, mice in the CCK‐8s group were fed normally and given two intraperitoneal injections of CCK‐8s (1.14 ng·kg‐1 body weight) per 24 h; normal saline was used as the control. The mice with a fasting blood glucose concentration higher than 16.7 mM were considered as successful diabetic models and then were injected with glucose (2 g·kg‐1 body weight; i.p.) and were used to measure blood glucose from the tail vein(0.6μl per sample) at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min thereafter.

Insulin secretion assay

For insulin secretion measurement in mouse islets, 50 freshly isolated islets from WT or β‐arrestin‐1‐/‐ mice were incubated in modified Krebs Ringer bicarbonate buffer (MKRBB: composition; 5 mM KCl, 120 mM NaCl, 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mg·mL‐1 BSA) with 5.5mM glucose or 16.7mM glucose for 30 minutes in the presence or absence of inhibitors followed by CCK‐8s stimulation for 20 minutes at 37°C. For insulin secretion measurement in dispersed islets cells, about 104 primary beta cells isolated from WT or β‐arrestin‐1‐/‐ mice were seeded in each well and were treated as isolated islets. The supernatants were collected, and the insulin content was measured using an insulin ELISA kit (Merck Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For insulin secretion measurement in primary beta cells, cells from WT or β‐arrestin 1‐/‐ mice were seeded in 24‐well plates, at a density of 106 cells per well, on the day before the experiment. Cells were washed and treated as described for islets. The final insulin concentration was normalized against the protein concentration of the lysate.

IP3 assay

IP3 production was determined with intact mouse islets in the basal state and in response to CCK‐8s using an specific enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for IP3 (EIAab Science). Freshly harvested islets were washed and incubated in MKRBB with 5.5mM glucose for 60 min at 37°C in groups of 50 islets in the presence or absence of lorglumide (1 μM). After 30 s of CCK‐8s stimulation, islets were rapidly centrifuged at 100×g at 4°C and washed with cold PBS followed by three freeze‐thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. The islets were lysed in cold lysis buffer for 20 min at 4°C. After centrifugation at 13800×g for 15 min at 4°C, supernatants were collected for IP3 determination according to the manufacturer's instructions.

cAMP assay

Freshly harvested islets were washed and incubated in MKRBB supplemented for 60 min at 37°C in groups of 50 islets in the presence or absence of lorglumide (1μM). After CCK‐8s stimulation for 15 min, islets were rapidly centrifuged at 100×g at 4°C and washed with cold PBS followed by three freeze‐thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen and lysis in cold lysis buffer containing 500 μM IBMX for 20 min at 4°C. After centrifugation at 13800×g for 15 min at 4°C, supernatants were collected for cAMP determination using an ELISA kit (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was evaluated by Hoechst 33342 staining, and TUNEL and Annexin V‐FITC/PI apoptosis detection kits. Briefly, dispersed islets cells or MIN6 cells were incubated in serum‐free, high‐glucose DMEM for 72 h in the absence or presence of CCK‐8s (100 pM), with or without β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown. For Hoechst 33342 staining, dispersed islets cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution for 10 min and stained with Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Cha) for 10 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus CK40, Tokyo, Japan). For the TUNEL assay, apoptosis was induced in the dispersed islet cells in the presence or absence of CCK‐8s (100 pM). Dispersed islets cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 1 h at room temperature, incubated in 0.1% TritonX‐100 for 2 min on ice and incubated in the TUNEL reaction mixture solution (Roche In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, POD) for 60 minutes at 37°C in the dark. Next, 50 µl of DAB substrate was added to the cells for 10 minutes at room temperature. Finally, the cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus CK40, Tokyo, Japan). For the Annexin V‐FITC/PI assay, MIN6 cells were collected and doubled stained with FITC‐conjugated Annexin V and PI according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were subjected to flow cytometry analysis, and the ratio of apoptotic cells was calculated using Flowjo software. Immunoprecipitation of β‐arrestin 1 and CCK1 receptors in MIN6 cells

The HA‐β‐arrestin‐1 (Rat) construct was a gift from Dr. Robert J Lefkowitz (Duke University). The human CCK1 receptor clone was obtained from Thermo Scientific and then subcloned into pCDNA3.1 with the N‐terminal signal peptide followed by a Flag tag. MIN6 cells were seeded in 10‐cm dishes and transfected with HA‐tagged β‐arrestin 1 and FLAG‐tagged CCK1 receptor plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty‐eight hours after transfection, MIN6 cells were starved in serum‐free DMEM overnight and then were incubated in 4 ml of Dulbecco's phosphate‐buffered saline (D‐PBS) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES for 2 h followed by stimulation with CCK‐8s for various times. Reactions were terminated by transfer of the plates onto ice. The interaction between CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 is stabilized by the addition of 1 ml of crosslinker buffer as described previously (D‐PBS containing 10 mM HEPES and 2.5 mM DSP in 1:1 aqueous DMSO (Xiao et al., 2010). After continuous slow agitation for 30 min at room temperature, crosslinking was stopped by 25 mM Tris‐HCl (pH 7.5) and incubated for another 15 minutes. MIN6 cells were washed with cold PBS and then lysed in 200 µl of cold lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P‐40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.25% (m/v) sodium deoxycholate, protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min and centrifuged 13800×g for 30 min at 4°C to clarify the lysate. Fifty microliters of each supernatant served as the whole‐cell lysate control, and the remaining lysate was incubated with 20 µl of anti‐FLAG M2‐Agarose affinity gel for 10 h at 4°C with gentle end‐to‐end rotation. Beads were washed three times with 500 µl of cold lysis buffer, and the protein was eluted with 40 µl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer.

β‐arrestin‐1 and CCK1 receptor knockdown using small interfering RNA (siRNA)

β‐arrestin‐1 and CCK1 receptor expression levels were silenced in MIN6 cells through transfection with chemically synthesized, double‐strand 19‐nucleotide siRNA with 2‐nucleotide 3’dTdT overhangs in the de‐protected and desalted form. The siRNA sequences targeting mouse β‐arrestin‐1 and CCK1 receptor were 5’‐AAAGCCUUCUGUGCUGAGAAC‐3’ and 5’‐AAGCTTGAGGTTGTACAAGTA‐3’. A non‐silencing RNA duplex, 5’‐AAUUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU‐3’, was used as a negative control. The day before transfection, MIN6 cells were seeded in 6‐well plates in DMEM without antibiotics and grown to approximately 40% confluence. MIN6 cells were transfected transiently with target or control siRNA duplex in opti‐MEM using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Seventy‐two hours after transfection, MIN6 cells were pre‐incubated in MKRBB for 2 h and treated with CCK‐8 for the indicated times in the presence or absence of ligands.

Subcellular fractionation

After stabilization in MKRBB for 2 h, MIN6 cells plated in 10‐cm dishes were stimulated with 100 pM CCK‐8 for 2 or 20 min. Cells were washed with cold PBS and scraped in 400 µl of hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES at pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaHCO3,0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1% Nonidet P‐40 and protease inhibitor cocktail). After 15 min of incubation, MIN6 cells were disrupted 100 times using a Dounce homogenizer on ice and centrifuged at 4100×g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants containing cytosolic and membrane proteins were collected and preserved for protein concentration determination and Western blotting. The pellets containing nuclear protein were mixed with 50 µl of cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 25% (v/v) glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated on ice for 30 min. After a freeze‐thaw cycle in liquid nitrogen, the lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13800×g at 4°C for 15 min, and nuclear proteins were collected for Western blotting analysis by SDS‐PAGE.

Western blotting analysis

To check endogenous CCK1 receptor and β‐arrestin expression in tissues, the fresh pancreatic acinar tissue, islets or muscles were mixed with 5 volumes of cold lysis buffer and then disrupted using a glass Dounce homogenizer for 15 minutes. Next, significant tissue particles were removed prior to centrifugation. Peptide‐N‐glycosidase F (PNGase F) was used to decrease the various glycosylation states of CCK1 receptors.

To examine CCK‐8s‐induced pancreatic beta cell signalling, MIN6 cells were washed twice and incubated in MKRBB for 2 h with starvation at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air, either with or without specific antagonists, and treated with CCK‐8s for various times. Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 25% (v/v) glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail) for 20 minutes at 4°C. After centrifugation at 13800×g at 4°C for 15 min, the protein concentration was quantified by the Bradford protein assay. Equal amounts of lysate proteins were denatured in 2× Laemmli sample buffer and were resolved by SDS‐PAGE (50 µg of protein per lane). After transferring to nitrocellulose membranes and blocking, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C with gentle shaking overnight. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated IgG for ~1–2 h at room temperature followed by chemiluminescence detection with the substrate from Pierce. The films were scanned, and the band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD).

Data analysis

The data are presented as the means ± SEM from four to five independent experiments. All of the results were graphed and statistically analysed using Student's t‐test for differences between two mean values and one‐way or two‐way ANOVA for multiple comparisons followed by Dunnett's and Bonferroni's post hoc tests for multiple comparisons, using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Materials

(Tyr[SO3H]27)‐cholecystokinin fragment 26‐33 amide (CCK‐8s), lorglumide sodium salt, streptozotocin (STZ), carbamylcholine chloride, GLP‐1 fragment 7‐36 amide, H89 dihydrochloride hydrate, U73122 hydrate, U0126 monoethanolate, anti‐FLAG antibody, and anti‐FLAG M2‐Agarose were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Peptide ‐N‐glycosidase F (PNGase F) was purchased from New England Biolabs (Haidian District, Beijing). Antibodies specific for phospho‐ERK1/2, Histone H3, phospho‐p90RSK (Thr573), phospho‐Bad (Ser112), Bad, and cleaved caspase 3 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies specific for ERK2, p90RSK, and β‐actin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti‐ β‐arrestin‐1 antibody ACT‐1 was from Dr. Robert J. Lefkowitz (Duke University, Durham, NC, USA). Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit and anti‐mouse IgG and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen Life Technologies (CarlsBad, CA). Anti‐ CCK1 receptor antibody was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate was from Pierce Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was obtained from Cellgro (Manassas, VA). Opti‐MEM was purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Double‐stranded 19‐nucleotide siRNA duplex with 2‐nucleotide 3’dTdT overhangs was from Xeragon (Germantown, MD). Collagenase P and the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN).

Results

CCK‐8s stimulates insulin secretion and inhibits beta cell apoptosis through CCK1 receptors

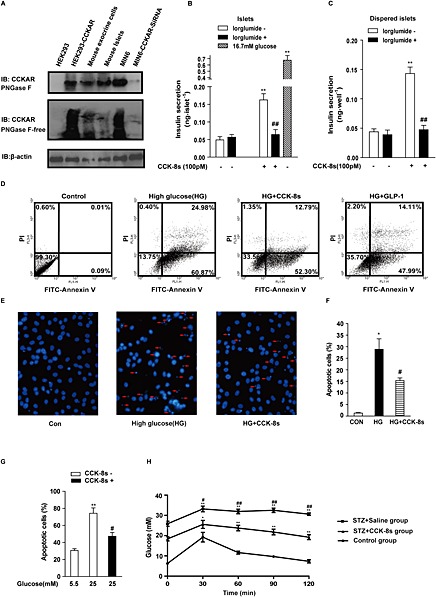

Cholecystokinin is a gastrointestinal hormone that is known to regulate pancreatic beta cell mass and function (Dufresne et al., 2006). Previously, reverse transcription PCR and immunostaining results have shown that CCK1 but not CCK2 receptors are expressed in human and rat pancreatic beta cells (Julien et al., 2004). We first examined the expression of CCK1 receptors in mouse islet beta cells using a specific anti‐ CCK1 receptor antibody. Exogenous overexpression of CCK1 receptors and siRNA‐mediated CCK1 receptor knockdown were used as positive and negative controls respectively (Figure 1A). After peptide‐N‐glycosidase F treatment, CCK1 receptor staining showed a narrow band with a molecular weight of approximately 40 kDa (upper panel, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

CCK‐8s stimulates insulin secretion and inhibits beta cell apoptosis through CCK1 receptors. (A): Representative immunoblot of CCK1 receptor protein expression in various cell types and tissues. The upper panel shows cell lysates pre‐incubated with peptide‐N‐glycosidase F. The lower panel was without peptide‐N‐glycosidase F treatment. (B): CCK‐8s (100 pM) stimulated insulin secretion, which was blocked by lorglumide (1 μM). More than 250 freshly isolated islets from 3 to 5 mice were pooled together and then divided to 50 islets of similar size in each group. The insulin content was measured using ELISA. The data shown are the means of four independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated islets compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for islets pre‐incubated with or without lorglumide; one‐way ANOVA. (C): Dispersed islet cells were treated with CCK‐8s, and insulin secretion was measured as in (B). The data shown are the average of five independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated dispersed islet cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for dispersed islets cells with or without pre‐incubation with lorglumide; one‐way ANOVA. (D): The protective effect of CCK‐8s (100 pM) on apoptosis of the MIN6 cells examined using Annexin V‐FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry. From left to right are MIN6 cells in normal medium, MIN6 cells exposed to high‐glucose (25 mM) medium without serum for 72 h, MIN6 cells simultaneously treated with high glucose (25 mM) and CCK‐8s, and MIN6 cells simultaneously treated with high glucose (25 mM) and GLP‐1. (E): Apoptosis of dispersed islet cells was evaluated by Hoechst‐33342 staining. The arrows indicate apoptotic dispersed islet cells. (F): The graph represents the quantitative analysis of the ratio of late apoptotic cells shown in Figure 1E from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 for high glucose‐treated cells compared with control cells; # P < 0.05 for CCK‐8s (100 pM)‐stimulated cells with high glucose compared with cells treated with high glucose only; one‐way ANOVA. (G): Apoptosis of dispersed islets cells induced by high glucose (25 mM) was confirmed with the TUNEL assay. ** P < 0.01 for high glucose‐treated cells compared with control cells; # P<0.05 for CCK‐8s (100 pM)‐stimulated cells with high glucose compared with cells treated with high glucose only; one‐way ANOVA. (H): CCK‐8s improved glucose tolerance in an STZ‐induced diabetic mouse model (n = 6 in each group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for the STZ‐treated group compared with the control group; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 for the CCK‐8s‐treated group compared with the non‐CCK‐8s‐treated group; two‐way ANOVA.

The sulfated octapeptide cholecystokinin fragment CCK‐8s is the smallest CCK form that retains most of the biological activities of the parent molecule. To investigate the functional roles of CCK in pancreatic islets, we first assessed the effect of CCK‐8s on insulin secretion. Previous studies have demonstrated that 100 nM CCK‐8s stimulates insulin secretion from the islets in a glucose‐independent manner, and this effect can be blocked by the CCK1 receptor‐specific antagonist L‐364,71 (Karlsson and Ahren, 1992a; Simonsson et al., 1996). The 100 nM concentration of CCK‐8s used in this study was markedly higher than the binding affinity of CCK‐8s for CCK1 receptors, which is 180 pM (Silvente‐Poirot et al., 1998). To re‐evaluate CCK‐8s‐mediated insulin secretion at a more physiological concentration, we treated isolated mouse islets with 100 pM CCK‐8s for 20 min. A 3.5‐fold increase in insulin secretion was observed, which was blocked by 1 μM lorglumide, a selective CCK1 receptor antagonist (Figure 1B). The CCK‐8s‐stimulated insulin secretion and its blockade by lorglumide were also observed in dispersed islet cells (Figure 1C). These results demonstrated that CCK‐8s promoted insulin secretion by direct activation of CCK1 receptors.

In addition to the dysfunctional insulin secretion, decreased beta cell mass is another mechanism underlying the progressive development of diabetes. The function of CCK1 receptors in pancreatic beta cell apoptosis has not been investigated. We next examined the protective effect of CCK‐8s on pancreatic beta cell apoptosis. The mouse pancreatic beta cell line MIN6 was exposed for 72 h to 25 mM glucose without serum in the presence of the vehicle control or receptor agonists. DMEM supplemented with serum was used as a negative control for glucose‐induced apoptosis, and 10 nM GLP‐1 was used as a positive control for the protective effect towards pancreatic beta cells. As shown in Figure 1D, the high‐glucose exposure led to 85% apoptotic cells after 72 h, and this effect could be reduced to 62% by the application of GLP‐1, the agonist of GLP‐1R that has been proven to be an efficient inhibitor of beta cell apoptosis (Sonoda et al., 2008; Lavine and Attie, 2010a). As with GLP‐1, CCK‐8s (100 pM) decreased the percentage of apoptotic MIN6 cells from 85% to 65%. To further confirm the protective role of CCK‐8s, we also examined pancreatic beta cells using Hoechst‐33342 staining (Figure 1E), which primarily indicates late apoptotic cells. As shown in Figure 1F, the numbers of late apoptotic cells were reduced from 30% to 15% by treatment with 100 pM CCK‐8s. Furthermore, the TUNEL assay was used to evaluate the protective role of CCK‐8s on the dispersed islet cells. As shown in Figure 1G, the percentage of apoptotic cells decreased from 75% to 45% after treatment with CCK‐8s (100 pM).

To extend the evaluation of the anti‐apoptotic effect of CCK‐8s into a more physiological context, we examined the effects of CCK‐8s on glucose tolerance using a STZ‐induced diabetic mouse model. The injection of STZ impaired glucose tolerance compared with non‐STZ‐treated mice, whereas treatment with CCK‐8s (100 pM) significantly lessened the effect of STZ (Figure 1H). These results demonstrated that CCK‐8s not only promoted insulin secretion but also protected beta cells from apoptosis in vivo.

Different contributions of the Gq/11 and Gs pathways in mediating CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion under low‐glucose or high‐glucose conditions

The CCK1 receptor couples to both Gq and Gs, leading to the accumulation of the second messengers IP3 and cAMP, respectively, in pancreatic acinar cells (Dufresne et al., 2006). In pancreatic beta cells, CCK activated PKC and cPLA2, which are essential for insulin secretion (Simonsson et al., 1996; Simonsson et al., 1998). However, whether activation of CCK1 receptors by CCK‐8s can induce cAMP signalling downstream of Gs and the contribution of these second messengers to CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion has not previously been examined. Therefore, we aimed to determine the CCK‐8s‐induced intracellular levels of cAMP and IP3 downstream of Gs and Gq/11 and to evaluate their contributions to insulin secretion.

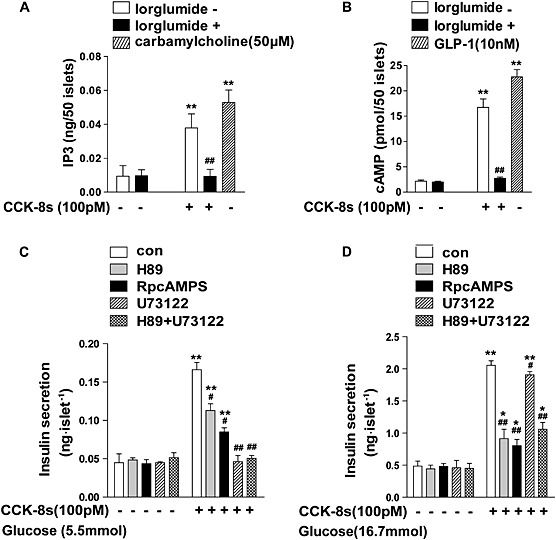

As shown in Figure 2A, CCK‐8s (100 pM) induced a fourfold increase in IP3 accumulation compared with the basal condition: slightly less than the level of IP3 induced by carbamoylcholine. Carbamylcholine activates the Gq ‐coupled muscarinic M3 receptor in pancreatic beta cells (Gautam et al., 2006; Gautam et al., 2007). Similarly, CCK‐8s (100 pM) induced a sixfold increase in cAMP accumulation compared with the basal condition: slightly less than the cAMP increase stimulated by 10 nM GLP‐1, a well‐characterized agonist of a Gs‐coupled GPCR (GLP‐1 receptor) in islets (Figure 2B). The CCK‐8s‐induced accumulation of both cAMP and IP3 was blocked by the CCK1 receptor‐specific antagonist lorglumide (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion is regulated by Gq/11 and Gs signalling downstream of CCK1 receptors. (A): CCK‐8s induces IP3 production in mouse pancreatic islets through activation of CCK1 receptors. More than 250 freshly isolated islets from 3 to 5 mice were pooled and then divided into 50 islets of similar size in each group and the IP3 levels were measured using an ELISA kit. Carbamylcholine (50 μM) was used as a positive control. The data shown are the average of five independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for cells pre‐incubated with or without lorglumide; one‐way ANOVA. (B): CCK‐8s induced cAMP production in mouse pancreatic islets through activation of CCK1 receptors. Islets were prepared as described in (A), and cAMP level were examined using an ELISA kit. GLP‐1 (10 nM) was used as a positive control for cAMP production. The data shown are the average of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for cells pre‐incubated with or without lorglumide; one‐way ANOVA. (C/D): The individual or combined effects of applying the PLC inhibitor U73122 (10 μM), the PKA inhibitor H89 (2 μM) or Rp‐cAMPS (100 μM) on CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion in isolated islets (C) under low‐glucose conditions (5.5 mM) or (D) under high‐glucose conditions (16.7 mM). More than 600 freshly isolated islets from six mice were pooled and then divided into 50 islets in each group of similar size. Data shown are the average of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated islets compared with the vehicle control; # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01 for islets pre‐incubated with specific inhibitors compared with those without the inhibitors; two‐way ANOVA.

Gq couples to PLC, whereas Gs stimulates both PKA and Epac. To dissect the functional roles of the selective signalling elements downstream of the different G subtypes in CCK‐8s‐stimulated insulin secretion, we applied the PLC inhibitor U73122, the PKA inhibitor H89 and a cAMP analogue, Rp‐cAMPS. Rp‐cAMPS is a competitive inhibitor for Epac and a non‐competitive inhibitor for PKA (Dostmann, 1995; Brown et al., 2014). The application of H89, an inhibitor of the PKA downstream from Gs, reduced the insulin secretion under low‐glucose conditions (5.5 mM) by 30%, while application of Rp‐cAMPS decreased the insulin secretion by approximately 50%. These results indicated that both the PKA pathway and Epac functions downstream from Gs contribute to CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion. Moreover, the application of U73122, the inhibitor of the signals downstream from Gq, or the combination of U73122 and H89 completely suppressed the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion, indicating an essential role for the Gq‐PLC pathway under low‐glucose conditions (Figure 2C).

However, in the presence of high glucose (16.7 mM), blocking the Gs downstream pathway by Rp‐CAMPS reduced the insulin secretion by 60%, whereas the application of the Gq‐PLC pathway inhibitor U73122 induced only a 10% decrease (Figure 2D). These results demonstrated that CCK‐8s promoted insulin secretion mainly through the Gq‐PLC signalling pathway in low glucose, whereas the Gs‐PKA/Epac signalling pathway played a more substantial role in the presence of high glucose. Thus, Gs‐mediated and Gq‐mediated CCK1 receptor signalling play distinct roles in insulin secretion under different physiological conditions.

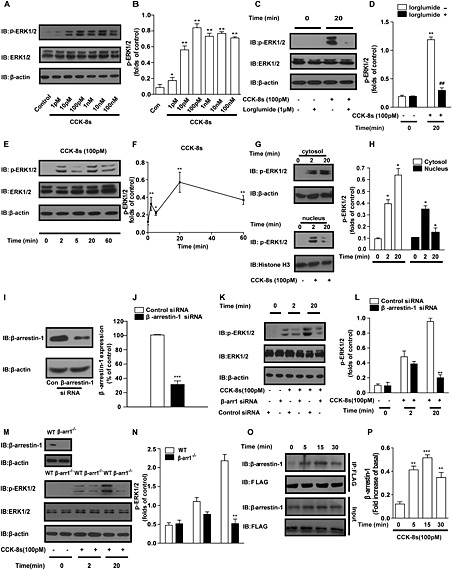

CCK‐8s induces two phases of ERK activation, the later phase of which is dependent on β‐arrestin‐1

The signalling kinases ERK1/2 are important regulators of many pancreatic beta cell functions, which include survival, proliferation, differentiation and insulin gene transcription (Lawrence et al., 2008; Quoyer et al., 2010). To further assess the mechanism(s) underlying the anti‐apoptotic effects of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells, we first examined ERK1/2 activation using a specific phospho‐ERK antibody following CCK‐8s treatment of murine MIN6 cells. As shown in Figure 3A and B, CCK‐8s led to a concentration‐dependent activation of ERK that reached a plateau above 100 pM, with an EC50 value of approximately 8 pM. To test whether CCK‐8s promoted ERK activation through CCK1 receptors, we used the specific CCK1 receptor antagonist lorglumide. Pretreatment of MIN6 cells with the specific CCK1 receptor antagonist lorglumide (1 μM) blocked ERK activation, confirming the involvement of CCK1 receptors (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

CCK‐8s induces transient and sustained two‐phase ERK activation by specific activation of CCK1 receptors in MIN6 cells and islets. (A): Twenty minutes of CCK‐8s stimulation induced ERK activation in a concentration‐dependent manner in MIN6 cells. (C): The CCK1 receptor‐specific antagonist lorglumide (1 μM) blocked the ERK activation induced by CCK‐8s in MIN6 cells. (E): Time course of ERK activation induced by CCK‐8s (100 pM) in MIN6 cells. (A, C, E): A Western blot representative of at least three independent experiments is shown. (B, D, F): Graphs showing the corresponding quantitative analysis of the fold increases of ERK activation from five representative experiments. The phospho‐ERK1/2 bands were quantified and normalized to the total actin levels. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## p < 0.01 for cells pre‐incubated with or without lorglumide; one‐way ANOVA.(G): Rapidly phosphorylated ERK1/2 was mainly observed in the nucleus, but the majority of late‐phase phospho‐ERK1/2 was found in the cytosol. β‐Actin and histone H3 were used as internal controls for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions respectively. Representative images from five independent experiments are shown. (H): Graph representing the relative levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation distributed in the cytosol and nucleus deduced from the quantitative results of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; one‐way ANOVA. (I, J): The β‐arrestin‐1 protein level in MIN6 cells decreased by 70% with specific β‐arrestin‐1 siRNA application. **P < 0.01 for β‐arrestin‐1 siRNA‐treated MIN6 cells compared with control siRNA‐treated cells; Student's t‐test. (K, M): Early‐phase (2 min) ERK activation was decreased by approximately 20%, but late‐phase (20 min) ERK activation was nearly abolished in β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown MIN6 cells (K) and islets isolated from β‐arrestin‐1 knockout mice (M). Representative images from five independent experiments are shown. (L, N): Graphs showing the corresponding quantitative analysis of the fold increases of ERK activation from five independent experiments. The phospho‐ERK1/2 bands were quantified and normalized to total actin levels. **P < 0.01, 20 min of CCK‐8s stimulation in β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown MIN6 cells or islets from β‐arrestin‐1 knockout mice were compared with MIN6 or islets from WT mouse vehicles; one‐way ANOVA. (O): Time course of complex formation between CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 induced by 100 pM CCK‐8s in MIN6 cells. Representative images from at least three independent experiments are shown. (P): Graph representing the relative levels of β‐arrestin‐1 that interacted with flag‐ CCK1 receptors in the MIN6 cells as indicated by the quantitative results of five independent experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; one‐way ANOVA. (B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P) Western blots from Figure 3A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O respectively. were quantified using Image J and analysed with GraphPad software.

The magnitude, duration and subcellular localization of the ERK kinases can alter the final cellular outcome. Analysis of the time course of CCK‐8s‐induced ERK activation showed two phases of ERK1/2 activation; the first was rapid and peaked at 2 min and the second was a slow sustained phase with a peak at 20 min (Figure 3E and F). In addition to the temporal course, the localization of ERK determines which substrates undergo phosphorylation to convey selective ERK functions. To monitor the subcellular localisation of ERK1/2 activation, cellular and nuclear proteins were separated by centrifugation and solubilized. As shown in Figure 3G and H, rapid phosphorylation of ERK1/2 mainly occurred in the nucleus, with most of the late‐phase ERK1/2 phosphorylation found in the cytosolic fraction.

Several GPCRs, such as the angiotensin AT1A receptor and the pituitary adenylate cyclase1 receptor, activate ERK in a temporally biphasic manner (Ahn et al., 2004; Broca et al., 2009). The early phase of ERK activation by these GPCRs is mediated by G proteins, whereas the later phase is dependent on the scaffolding proteins β‐arrestins. Therefore, we next evaluated the role of β‐arrestin‐1 in the ERK activation induced by CCK‐8s, through the depletion of endogenous β‐arrestin‐1 in MIN6 cells using siRNA. As shown in Figure 3I and J, 70% suppression of β‐arrestin‐1 protein expression was observed in specific β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown MIN6 cells compared with cells treated with control siRNA. After CCK‐8s stimulation, the kinetic pattern of ERK activation in β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown MIN6 cells varied significantly. The early phase (2 min) of ERK activation was not changed, whereas the long‐lasting (20 min) ERK activation was 80% diminished (Figure 3K and L). To confirm the role of β‐arrestin‐1 in the kinetic pattern of ERK activation, we used the knockout model and isolated islets from WT and β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice. As shown in Figure 3M and N, the early phase of ERK activation was decreased by approximately 20%, whereas the sustained ERK activation was inhibited by 80% after CCK‐8s stimulation of the islets of β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice.

The earlier results demonstrated that β‐arrestin‐1 governed the sustained ERK activation induced by CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells. In addition to G proteins, β‐arrestins are important signalling molecules that form a complex with GPCRs after their activation and initiate a ‘second wave’ of cellular signalling to regulate cell survival, migration and many other cell functions (Rajagopal et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2011). The formation of a complex between β‐arrestin‐1 and CCK1 receptors could be important for CCK‐8s‐induced ERK activation, but the interaction between CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestins has not previously been examined. Therefore, we co‐transfected flag‐CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 and monitored the association between CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 by co‐immunoprecipitation experiments after CCK‐8s stimulation. As shown in Figure 3O and P, the association between CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 increased after CCK‐8s treatment, and the interaction peaked at 15 min, in agreement with the time course of the sustained ERK activation.

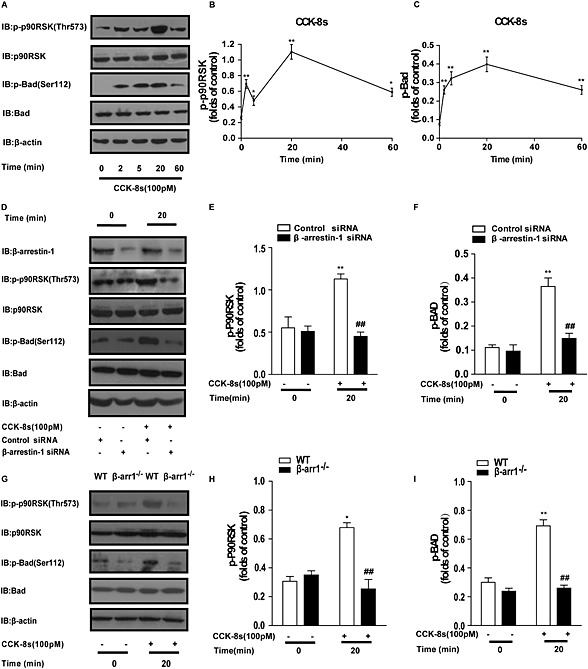

β‐arrestin‐1 is required for the p90RSK‐phospho‐Bad anti‐apoptotic pathway activated by CCK‐8s

Two known ERK substrates have been reported to mediate the ERK functions involved in pancreatic beta cell survival: the 90‐kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK) and the Bcl‐2 family protein Bad, a pro‐apoptotic protein (Jin et al., 2005; Anjum and Blenis, 2008; Danial et al., 2008). Therefore, we evaluated the time dependence of the phosphorylation of both p90RSK and Bad. The time course of p90RSK phosphorylation on Thr573 was also biphasic, having one phase that peaked at 2 and the other at 20 min (Figure 4A and B). The phosphorylation of Bad‐Ser112 had only a slow phase that peaked at 20 min (Figure 4A and C). Importantly, the phosphorylation of Thr573 in the RSK C‐terminal kinase domain by ERK2 is required for RSK activation and its subcellular translocation, after which it can phosphorylate additional substrates including Bad. Phosphorylation of Bad on Ser112promotes its association with 14‐3‐3 and retention in the cytoplasm, which prevents the release of cytochrome C, an important apoptotic regulator (Jin et al., 2005; Danial et al., 2008).

Figure 4.

β‐Arrestin‐1 is required for the CCK‐8s‐activated ERK‐p‐p90RSK‐p‐Bad anti‐apoptotic pathway. (A): Time course of CCK‐8 (100 pM)‐induced p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation in MIN6 cells. β‐Actin was used as the loading control. (B, C): Western blots from Figure 4A for phospho‐RSK or phospho‐BAD were quantified using Image J software, normalized to total actin levels and then analysed using GraphPad. The two graphs show the corresponding quantitative analysis of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation mediated by CCK‐8s. Phospho‐p90RSK‐Thr573 and phospho‐Bad‐Ser112 bands from approximately five experiments were quantified and normalized to the total p90RSK and Bad protein levels respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; one‐way ANOVA. (D): β‐Arrestin‐1 depletion blocked CCK‐8s‐induced p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation in MIN6 cells. (E, F): Western blots were analysed as shown in Figure 4B and C. Quantitative analysis of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation from three to five representative experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for ß‐arrestin‐1 knockdown cells compared with control cells; one‐way ANOVA. (G): More than 200 freshly isolated islets from two WT or β‐arrestin‐1 [knockout (KO)] mice were pooled and then divided into 100 islets in each group of similar size. Data shown are the average of three independent experiments. Representative Western blots from five independent experiment are shown. Data suggested that the CCK‐8s‐activated p90RSK‐phospho‐Bad pathway in isolated islets is impaired in β‐arrestin‐1 KO mice. (H, I): Western blots were analysed as shown in Figure 4B and C. Quantitative analysis of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation from at least five representative experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for β‐arrestin‐1 KO islets compared with control islets; one‐way ANOVA.

Both p90RSK activation and Bad phosphorylation occur downstream of ERK activation, and these events reach peaks at a time that corresponds to the sustained phase of the β‐arrestin‐1‐dependent ERK activation. These observations led us to explore the role of β‐arrestin‐1 in p90RSK‐Thr573 activation and Bad phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 4D–F, in the β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown cells, the CCK‐8s‐induced phosphorylation of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 was significantly suppressed. Moreover, CCK‐8s‐induced phosphorylation of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 was significantly suppressed in islets isolated from the β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice, compared with those from the WT mice (Figure 4G–I). Taken together, these results demonstrated that β‐arrestin‐1 is required for the CCK‐8s‐activated p90RSK‐phospho‐Bad anti‐apoptotic pathway.

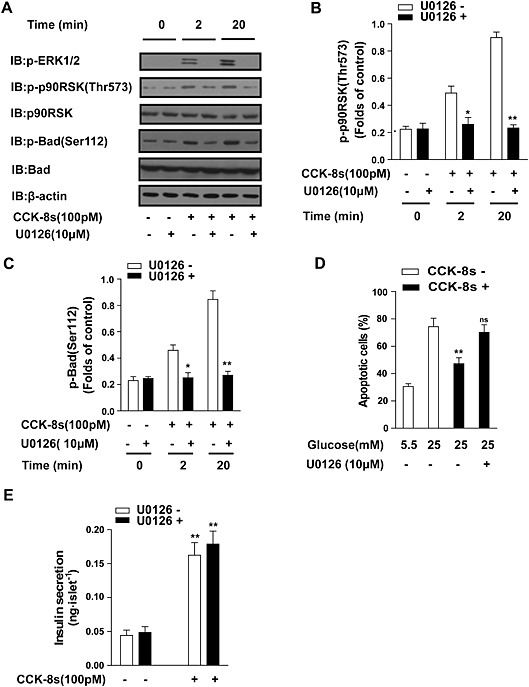

The MEK–ERK pathway underlies the protective effect of CCK‐8s but not insulin secretion

MEK is an upstream ERK, and its inhibitor U0126 is a powerful tool often used to investigate the functions of the MEK–ERK signalling pathway. As shown in Figure 5A, the MEK inhibitor U0126 significantly blocked ERK phosphorylation at both at the early phase (2 min) and late phase (20 min). Accordingly, the CCK‐8s‐induced phosphorylation of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 were both significantly decreased in the presence of U0126 (Figure 5A–C). We further evaluated the contribution of the MEK–ERK pathway to the CCK‐8s‐mediated anti‐apoptosis effect in dispersed islet cells. As shown in Figure 5D, CCK‐8s stimulation decreased the percentage of apoptotic cells from 80% to less than 50%, whereas pre‐incubation with U0126 prevented the anti‐apoptotic effects of CCK‐8s. These results demonstrated that the MEK–ERK pathway underlies the protective effect of CCK‐8s in islet cells. In contrast, application of the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 has no effect on CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion, indicating that the MEK–ERK pathway specifically mediates the anti‐apoptotic effect of CCK‐8s (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

The MEK–ERK pathway underlies the protective effect of CCK‐8s but not insulin secretion. (A): The MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) significantly decreased the late‐phase (20 min) p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation in isolated islets. More than 600 freshly isolated islets from five mice were pooled and then divided into 100 islets in each group of similar size. An image representative of five independent experiments is shown. (B, C): Western blots from Figure 5A for phospho‐RSK or phospho‐BAD were quantified using Image J software, normalized to actin levels and then analysed using GraphPad. The graphs show the corresponding quantitative analysis of p90RSK‐Thr573 and Bad‐Ser112 phosphorylation from five representative experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for U0126‐treated islets compared with the vehicle control; one‐way ANOVA. (D): MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) treatment blocked the CCK‐8s‐mediated protective effect against apoptosis in dispersed islet cells using the TUNEL assay. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐treated pancreatic beta cells compared with control vehicle. ns, no significant difference, U0126 plus CCK‐8s‐treated pancreatic beta cells compared with beta cells treated with CCK‐8s only; two‐way ANOVA. (E): MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) treatment did not decrease CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion in isolated islets. More than 250 freshly isolated islets from 3 to 5 mice were pooled and then divided into 50 islets of similar size in each group. Data shown are the average of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated isolated islets compared with the vehicle control; one‐way ANOVA.

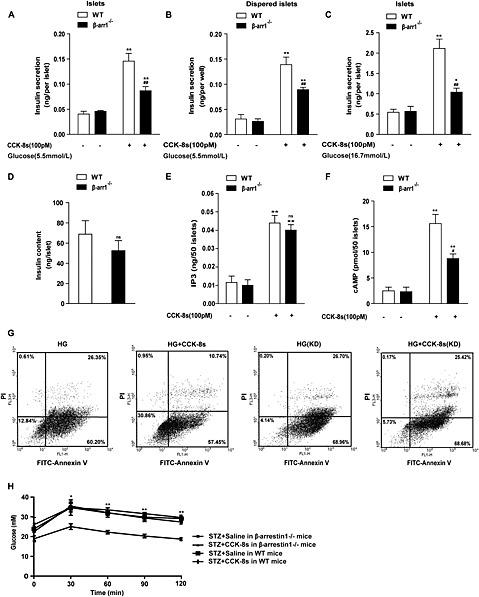

β‐arrestin‐1 is an important regulator of insulin secretion and an essential component of the protective effect downstream of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells.

β‐Arrestin‐1 has been reported to be important in the GLP‐1‐induced, but not potassium chloride‐induced, insulin secretion in islets and INS‐1 cells (Sonoda et al., 2008). To assess the role of β‐arrestin‐1 in CCK‐8s‐stimulated insulin secretion, we examined the insulin secretion induced by CCK‐8s in pancreatic islets isolated from WT and β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice. In the absence of CCK‐8s, there was no significant difference in the basal insulin level between the islets from WT and β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice (Figure 6A). However, the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion from the β‐arrestin‐1−/− islets was decreased by approximately 50% compared with that from the WT mice in the low‐glucose condition and by approximately 70% in the high‐glucose condition (Figure 6A–C). The observed difference in insulin secretion was not due to insulin availability because there was no significant insulin content difference between the WT and β‐arrestin‐1−/− islets (Figure 6D) (Sonoda et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

β‐Arrestin‐1 mediates insulin secretion and the protective effect of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells. (A, B): CCK‐8s induced insulin secretion from (A) islets or (B) dispersed islet cells in β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with WT mice under low‐glucose conditions (5.5 mM). More than 250 freshly isolated islets from 3 to 5 WT or β‐arrestin‐1 [knockout (KO)] mice were pooled and then divided into 50 islets of similar size in each group, and the insulin content was measured using ELISA. The data shown are the average of four independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle control; ## P < 0.01 for β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with WT mice; one‐way ANOVA. (C): CCK‐8s induced insulin secretion from the islets of β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice, and WT mice were examined under high‐glucose conditions (16.7 mM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with control vehicles; ## P < 0.01 for β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with WT mice; one‐way ANOVA. (D): There was no significant difference (ns) of the total insulin content in isolated islets between β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice and WT mice. Insulin content was analysed using Student's t‐test. (E): The CCK‐8s‐induced IP3 production in islets is normal in β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with that in WT mice. More than 250 freshly isolated islets from 3 to 5 WT or β‐arrestin‐1 (KO) mice were pooled and then divided into 50 islets of similar size in each group, and the IP3 levels were measured using an ELISA kit. **P < 0.01 for CCK‐8s‐stimulated cells compared with the vehicle controls; ns, for β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with WT mice; one‐way ANOVA. (F): CCK‐8s‐induced cAMP production in islets is decreased in β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with that in WT mice. Islets were prepared as in (E), and the cAMP level was measured using an ELISA kit. **P < 0.01 for islets from β‐arrestin‐1 KO mice compared with islets from WT mice; one‐way ANOVA. (G): β‐arrestin‐1 depletion abolished the protective effect of CCK‐8s in MIN6 cells. From left to right and from up to down are MIN6 cells exposed to high‐glucose medium without serum for 72 h, MIN6 cells simultaneously treated with CCK‐8s and high glucose, β‐arrestin‐1 KO MIN6 cells exposed to high‐glucose medium without serum, and β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown MIN6 cells simultaneously treated with CCK‐8s and high glucose. (H): CCK‐8s failed to improve glucose tolerance in an STZ‐induced β‐arrestin‐1−/− diabetic mice, as indicated by glucose tolerance tests (n = 6 for each group). β‐Arrestin‐1−/− mice and WT mice were treated with STZ and CCK‐8s as described in Figure 1H. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for the β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice treated with CCK‐8s compared with the WT mice treated with CCK‐8s; two‐way ANOVA.).

To dissect the underlying mechanism of the β‐arrestin‐1 function in insulin secretion, we next examined the effects of β‐arrestin‐1 on IP3 and cAMP accumulation, which we have shown to be important coordinators of insulin secretion after CCK‐8s administration. As shown in Figure 6E, no significant difference in IP3 production induced by CCK‐8s was observed in the β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with the WT mice. However, as shown in Figure 6F, the level of cAMP induced by CCK‐8s was decreased by 40% in β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice compared with WT mice. In summary, β‐arrestin‐1 positively regulates the accumulation of the second messenger cAMP, but not IP3, downstream of CCK1 receptor activation in pancreatic beta cells. This regulatory effect could mediate the functional role of β‐arrestin‐1 in promoting insulin secretion.

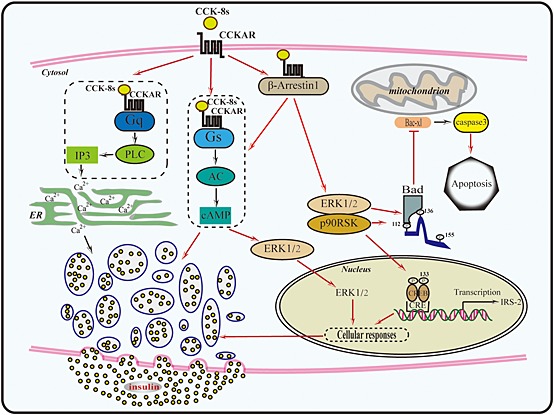

To evaluate the biological significance of the β‐arrestin‐1‐mediated anti‐apoptotic signalling, we tested the CCK‐8s‐induced protective effect on high glucose‐induced pancreatic beta cell apoptosis following the knockdown of β‐arrestin‐1 expression. CCK‐8s treatment reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells from 87% to 68%, whereas this protective effect was not detectable after β‐arrestin‐1 knockdown (Figure 6G). To extend the study of the important role of β‐arrestin‐1 in the protection of islet cell from apoptosis to a more physiological context, we investigated the effect of CCK‐8s on glucose tolerance in STZ‐treated β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice. Although CCK‐8s significantly improved the glucose tolerance in STZ‐treated WT mice, application of the CCK‐8s did not significantly change the glucose tolerance in the β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice (Figure 6H), confirming the physiological relevance of β‐arrestin‐1 in mediating the protective effect of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Diagram of the signalling pathways downstream of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells. CCK‐8s binds to CCK1 receptors on the plasma membrane of pancreatic beta cells, promoting the formation of complexes of CCK1 receptor‐Gq and CCK1 receptor‐Gs. Activation of Gq produces IP3, which induces intracellular calcium release and is critical for insulin secretion. At the same time, CCK1 receptors activate Gs and increases intracellular cAMP. cAMP activates PKA and Epac, leading to the translocation of phosphorylated ERK2 into the nucleus. The Gs‐mediated pathway also underlies the regulation of CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion in high glucose condition. In addition to Gq and Gs, CCK1 receptors also form complexex with β‐arrestin‐1. The CCK1 receptor‐β‐arrestin‐1 complex is responsible for the long‐term cytosol ERK activation and initiates the ERK‐pRSK90‐Bad‐Caspase‐3 anti‐apoptotic pathway. The interplay between β‐arrestin‐1 and the Gs pathway is required for efficient insulin secretion.

Discussion and conclusions

Research towards understanding the mechanism of the functions of the gastrointestinal hormone GLP‐1 in pancreatic beta cells has led to the successful development of clinical therapeutic agents for type 2 diabetes, such as the GLP‐1 mimic exenatide and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (Ahren, 2009). Another gastrointestinal hormone, CCK, is synthesized in the endocrine I cells in the mucosa of the duodenum in response to food intake. This hormone exists in various forms from 4 to 58 amino acid residues (Liddle et al., 1985; Cantor, 1989). Among these peptides, the sulfated octapeptide of CCK‐8 (CCK‐8s) retains full biological activity in terms of insulin secretion (Karlsson and Ahren, 1992b). CCK‐8s has been shown to improve insulin secretion in diabetic patients and positively regulates pancreatic beta cell mass in animal models (Karlsson and Ahren, 1992a; Ahren et al., 2000). Our current work has shown that CCK‐8s potently induces insulin secretion and exerted its protective effect on pancreatic beta cells at a low concentration (100 pM) and is thus at least one order of magnitude more potent than GLP‐1 (Figure 1). Therefore, compounds targeting the CCK‐8s‐mediated pancreatic beta cell signalling pathway could be considered as a novel approach to anti‐diabetic therapy.

Of the two known CCK receptors, the CCK1 receptor is the only receptor that receives the CCK‐8s signal at the pancreatic beta cell membrane and transmits the information into the cytoplasm (Julien et al., 2004). CCK1 receptors are GPCRs and activate both the Gs and Gq signalling pathways in pancreatic acinar cells (Dufresne et al., 2006). In addition to the G protein‐mediated receptor signalling, the β‐arrestin scaffolding proteins not only mediate receptor desensitization but also initiate a ‘second wave’ by forming a complex with specific receptors and recruiting unique sets of effectors (Rajagopal et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2010; Shukla et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2012). Whether β‐arrestins interact with CCK1 receptors and mediate specific CCK1 receptor functions after CCK‐8s stimulation has not been previously characterized. Moreover, detailed knowledge of the contribution of different downstream signalling events after CCK1 receptor activation in pancreatic islets would be valuable in designing CCK1 receptor‐targeted therapeutic agents to minimize unwanted side effects. On the basis of these considerations, we investigated the function of Gs‐mediated, Gq‐mediated or β‐arrestin‐mediated signalling downstream from CCK1 receptor activation in pancreatic islets, using specific inhibitors and β‐arrestin knockout mice.

In pancreatic beta cells, CCK‐8s is known to stimulate insulin secretion through the Gq‐phosphoinositide‐calcium pathway. Whether the Gs pathway is activated downstream of CCK‐8s in pancreatic beta cells has not previously been evaluated (Zawalich et al., 1987). The same GPCR can couple to one or more G proteins as a function of the specific cellular context due to differential protein expression. To acquire a detailed view of the G protein‐mediated CCK signalling in pancreatic beta cells, we measured the IP3 and cAMP levels evoked by CCK‐8s and evaluated their relative contributions to the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion under both low‐ and high‐glucose conditions. CCK‐8s (100 pM) elicited the accumulation of IP3 and cAMP in the pancreatic beta cells at levels comparable with the levels elicited by the other physiological stimulators, carbamylcholine and GLP‐1 (Figure 2A and B). Furthermore, using U73122, H89 and Rp‐CAMPS, which selectively block Gq downstream PLC activity and Gs downstream PKA/Epac activities, we demonstrated that the Gq‐PLC signalling pathway mainly contributed to CCK‐8s‐promoted insulin secretion under low‐glucose conditions (Figure 2C). However, Gs‐PKA/Epac signalling contributed more to the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion under high‐glucose conditions (Figure 2D). Therefore, the observed signalling activities distinguished the CCK8–CCK1 receptor pathways from both the GLP‐1‐GLP‐1receptor and muscarinic cholinoceptor pathways in beta cells: specifically, the Gs‐mediated and Gq‐mediated CCK‐8s pathways differentially regulated insulin secretion under different physiological contexts.

Recent studies of islets have shown that β‐arrestin‐1 is required for both the GLP‐1‐promoted insulin secretion and its protective effect through the cAMP and ERK pathways respectively (Sonoda et al., 2008; Quoyer et al., 2010). Moreover, β‐arrestin‐1 is responsible for the sustained late phase of ERK activation downstream of both GLP‐1 and pituitary adenylate cyclase‐activating peptide action on pancreatic beta cells (Broca et al., 2009; Quoyer et al., 2010). We also observed that the β‐arrestin‐1‐ERK‐PAX6 pathway regulated somatostatin transcription downstream of β‐adrenoceptor signalling in pancreatic beta cells (Wang et al., 2014). All of these studies revealed important roles of β‐arrestin‐1 in islets. Therefore, we investigated the relevance of β‐arrestin‐1 in CCK‐8s‐mediated signalling. We observed that CCK‐8s promoted the association of CCK1 receptors and β‐arrestin‐1 that mediate the late phase of ERK activation (Figure 3O and P). Although the early phase of ERK activation occurred in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, the late phase of ERK activation primarily occurred in the cytoplasm. This localization controls the ERK substrate specificity and determines the ERK‐mediated cellular functions (Figure 3G and H). Specifically, nuclear phospho‐ERK regulates insulin gene transcription by phosphorylating transcription factors such as Pdx‐1, MafA and Foxo1 (Lawrence et al., 2008). Activated ERK in the cytoplasm can phosphorylate other sets of substrates, such as p90RSK and Bad, that are involved in regulating the anti‐apoptotic pathway (Lawrence et al., 2008). Our results showed that CCK‐8s stimulated successive long‐term ERK activation, p90RSK phosphorylation at Thr573 and Bad phosphorylation at Ser112 (Figures 3 and 4). Phosphorylation of Bad‐Ser112 facilitated its interaction with the scaffold protein 14‐3‐3, avoiding the mitochondria and blocking the release of cytochrome C, which is the key step in the regulation of cell apoptosis. Thus, β‐arrestin‐1 could participate in the cytoplasmic ERK‐p90RSK‐phospho‐Bad anti‐apoptotic pathway and mediate the protective effect of CCK‐8s. In agreement with such a hypothesis, the knockdown of β‐arrestin‐1 in MIN6 cells impaired the late phase ERK activation, the p90RSK‐phospho‐Bad anti‐apoptotic pathway and the anti‐apoptotic effect of CCK‐8s (Figure 4D–F). These phenomena were also confirmed using β‐arrestin‐1−/− mice (Figure 4G–I). The observed β‐arrestin‐1‐mediated protective effect of CCK‐8s is very similar to the function of β‐arrestin‐1 downstream of GLP‐1. Accordingly, both β‐arrestin‐2 and β‐arrestin‐1 activated ERK in HEK‐293 cells and several other cell types (Milasta et al., 2005; Ren et al., 2005; Coffa et al., 2011a; Coffa et al., 2011b; Nobles et al., 2011).

In addition to the anti‐apoptotic effects, our data revealed that β‐arrestin‐1 is an important component in the stimulation of insulin secretion, downstream of CCK signalling acting through crosstalk with cAMP in pancreatic beta cells. In model systems such as HEK293 cells or COS‐7 cells, β‐arrestins negatively regulate cAMP and IP3 accumulation by recruiting PDE to the β2‐adrenoceptors or diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs) to the muscarinic M1 receptors respectively (Perry et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2007). In pancreatic beta cells, previous results (Sonoda et al., 2008) as well as our current results suggest that β‐arrestin‐1 is a positive regulator of cAMP accumulation downstream of GLP‐1 or CCK‐8s. These results distinguish the β‐arrestin functions in pancreatic beta cells from those in other cell types. The receptor activation was accompanied by multiple phosphorylations, which could enable multiple conformations of arrestins and convey distinct downstream signal information. Recently, a direct interaction between β‐arrestin‐1 and Gs has been observed (Li et al., 2013). Although the arrestin and Gs may compete for a single receptor, it does not exclude the possibility that a receptor could activate Gs indirectly through a specific arrestin conformation or that there is other unknown mechanism for a specific receptor to activate Gs through β‐arrestin‐1. Moreover, recent studies have indicated that endocytosis is required for the full cAMP production downstream of specific GPCRs (Li et al., 2013; Tsvetanova and von Zastrow, 2014). Therefore, the observed differences of function of β‐arrestin‐1 in regulating intracellular cAMP level could be due to the cell type and receptor specificity (Nobles et al., 2011; Shukla et al., 2013). The specific modulation of Gs activity and cAMP production by β‐arrestin‐1 might be unique to pancreatic beta cells. Further studies on arrestins, particularly those in pancreatic beta cells, are required to elucidate the details of receptor function in insulin secretion.

Biased signalling of GPCRs has been extensively studied and reviewed in recent years. Understanding this process is essential to developing new drugs because it can lead to the elimination of unwanted side effects by developing compounds that specifically induce one effector downstream of the receptor but do not activate others (Cnop et al., 2005; Rajagopal et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2011; Whalen et al., 2011). As a widely expressed receptor, full agonists of CCK1 receptors also promote gall bladder contraction, pancreatic enzyme secretion and other physiological activities besides their effects on the promotion of insulin secretion and anti‐apoptotic effects in pancreatic beta cells (Dufresne et al., 2006). The current work demonstrated that Gq‐PLC signalling was essential in mediating CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion under low‐glucose conditions, whereas the Gs‐PKA/Epac‐mediated CCK1 receptor signalling played a more vital role in the control of CCK‐8s‐stimulated insulin secretion under high‐glucose conditions. Downstream of CCK1 receptors, Gq‐PLC‐mediated insulin secretion under normal glucose conditions may be an unwanted effect, whereas Gs‐PKA/Epac‐mediated insulin secretion under high blood glucose conditions may be valuable for the treatment of diabetic patients. This hypothesis should be tested by specific CCK1 receptor mutations or our recently developed receptor–effector fusion method in more physiological/pathological contexts (Wu et al., 1999; Strachan et al., 2014).

In addition to the G protein‐mediated CCK1 receptor pathway, our study also demonstrated that β‐arrestin‐1‐mediated CCK1 receptor signalling played important roles in regulating the CCK‐8s‐induced insulin secretion and the anti‐apoptotic effects in pancreatic islets (Figure 6). Therefore, binding of selective ligands to CCK1 receptors that induce only the β‐arrestin‐1 and Gs signalling pathways could improve desirable functions of pancreatic beta cells and eliminate unnecessary side effects. Further work in developing biased agonists for CCK1 receptors and evaluating their effects in the regulation of beta cell and other CCK1 receptor functions will broaden the scope of studies to develop novel anti‐diabetic treatments.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest regarding to this work were reported.

Supporting information

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2012CB910402 to JP. S. and 2013CB967700 to X. Y.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271505 and 31470789 to JP. S.; 31270857 to X. Y. and 31171097 to C. W.), the Shandong Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (JQ201320 to X. Y.), the Fundamental Research Fund of Shandong University (2014JC029 to X. Y.), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2014CP007 to DL. Z.) and Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT13028).

Ning, S.‐l. , Zheng, W.‐s. , Su, J. , Liang, N. , Li, H. , Zhang, D.‐l. , Liu, C.‐h. , Dong, J.‐h. , Zhang, Z.‐k. , Cui, M. , Hu, Q.‐X. , Chen, C.‐c. , Liu, C.‐h. , Wang, C. , Pang, Q. , Chen, Y.‐x. , Yu, X. , and Sun, J.‐p. (2015) Different downstream signalling of CCK1 receptors regulates distinct functions of CCK in pancreatic beta cells. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172: 5050–5067. doi: 10.1111/bph.13271.

References

- Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ (2004). Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta‐arrestin and G protein‐mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J Biol Chem 279: 35518–35525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahren B (2009). Islet G protein‐coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8: 369–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahren B, Holst JJ, Efendic S (2000). Antidiabetogenic action of cholecystokinin‐8 in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al. (2013a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein‐Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1459–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al. (2013b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1797–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum R, Blenis J (2008). The RSK family of kinases: emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ (2007). Biology of incretins: GLP‐1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 132: 2131–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broca C, Quoyer J, Costes S, Linck N, Varrault A, Deffayet PM et al. (2009). beta‐Arrestin 1 is required for PAC1 receptor‐mediated potentiation of long‐lasting ERK1/2 activation by glucose in pancreatic beta‐cells. J Biol Chem 284: 4332–4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LM, Rogers KE, McCammon JA, Insel PA (2014). Identification and validation of modulators of exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) activity: structure‐function implications for Epac activation and inhibition. J Biol Chem 289: 8217–8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor P (1989). Cholecystokinin in plasma. Digestion 42: 181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor P, Rehfeld JF (1989). Cholecystokinin in pig plasma: release of components devoid of a bioactive COOH‐terminus. Am J Physiol 256 (1 Pt 1): G53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jorns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL (2005). Mechanisms of pancreatic beta‐cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes 54 (Suppl 2): S97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffa S, Breitman M, Hanson SM, Callaway K, Kook S, Dalby KN et al. (2011a). The effect of arrestin conformation on the recruitment of c‐Raf1, MEK1, and ERK1/2 activation. PLoS One 6: e28723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffa S, Breitman M, Spiller BW, Gurevich VV (2011b). A single mutation in arrestin‐2 prevents ERK1/2 activation by reducing c‐Raf1 binding. Biochemistry 50: 6951–6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danial NN, Walensky LD, Zhang CY, Choi CS, Fisher JK, Molina AJ et al. (2008). Dual role of proapoptotic BAD in insulin secretion and beta cell survival. Nat Med 14: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JH, Chen X, Cui M, Yu X, Pang Q, Sun JP (2012). beta2‐adrenergic receptor and astrocyte glucose metabolism. J Mol Neurosci: MN 48: 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostmann WR (1995). (RP)‐cAMPS inhibits the cAMP‐dependent protein kinase by blocking the cAMP‐induced conformational transition. FEBS Lett 375: 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou HQ, Xu YF, Sun JP, Shang S, Guo S, Zheng LH et al. (2012). Thiopental‐induced insulin secretion via activation of IP3‐sensitive calcium stores in rat pancreatic beta cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C796–C803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne M, Seva C, Fourmy D (2006). Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors. Physiol Rev 86: 805–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evron T, Peterson SM, Urs NM, Bai Y, Rochelle LK, Caron MG et al. (2014). G protein and beta‐arrestin signaling bias at the ghrelin receptor. J Biol Chem 289: 33442–33455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam D, Han SJ, Duttaroy A, Mears D, Hamdan FF, Li JH et al. (2007). Role of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in beta‐cell function and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes Metab 9 (Suppl 2): 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam D, Han SJ, Hamdan FF, Jeon J, Li B, Li JH et al. (2006). A critical role for beta cell M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in regulating insulin release and blood glucose homeostasis in vivo. Cell Metab 3: 449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley SC, Austin E, Assouline‐Thomas B, Kapeluto J, Blaichman J, Moosavi M et al. (2010). {beta}‐Cell mass dynamics and islet cell plasticity in human type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology 151: 1462–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin N, Frizelle P, Montgomery IA, Moffett RC, O'Harte FP, Flatt PR (2012). Beneficial effects of the novel cholecystokinin agonist (pGlu‐Gln)‐CCK‐8 in mouse models of obesity/diabetes. Diabetologia 55: 2747–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin N, Frizelle P, O'Harte FP, Flatt PR (2013). Metabolic effects of activation of CCK receptor signaling pathways by twice‐daily administration of the enzyme‐resistant CCK‐8 analog, (pGlu‐Gln)‐CCK‐8, in normal mice. J Endocrinol 216: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Zhuo Y, Guo W, Field J (2005). p21‐Activated Kinase 1 (Pak1)‐dependent phosphorylation of Raf‐1 regulates its mitochondrial localization, phosphorylation of BAD, and Bcl‐2 association. J Biol Chem 280: 24698–24705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien S, Laine J, Morisset J (2004). The rat pancreatic islets: a reliable tool to study islet responses to cholecystokinin receptor occupation. Regul Pept 121: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson S, Ahren B (1992a). CCK‐8‐stimulated insulin secretion in vivo is mediated by CCKA receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 213: 145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson S, Ahren B (1992b). Cholecystokinin and the regulation of insulin secretion. Scand J Gastroenterol 27: 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Abraham DM, Williams B, Violin JD, Mao L, Rockman HA (2012). beta‐Arrestin‐biased AT1R stimulation promotes cell survival during acute cardiac injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1001–H1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliaki C, Doupis J (2011). Incretin‐based therapy: a powerful and promising weapon in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther 2: 101–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz E, Pinget M, Damge P (2004). Cholecystokinin octapeptide: a potential growth factor for pancreatic beta cells in diabetic rats. JOP 5: 464–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine JA, Attie AD (2010a). Gastrointestinal hormones and the regulation of beta‐cell mass. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1212: 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine JA, Raess PW, Stapleton DS, Rabaglia ME, Suhonen JI, Schueler KL et al. (2010b). Cholecystokinin is up‐regulated in obese mouse islets and expands beta‐cell mass by increasing beta‐cell survival. Endocrinology 151: 3577–3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M, Shao C, Duan L, McGlynn K, Cobb MH (2008). The protein kinases ERK1/2 and their roles in pancreatic beta cells. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 192: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Wang C, Zhou Z, Zhao J, Pei G (2013). beta‐Arrestin‐1 directly interacts with Galphas and regulates its function. FEBS Lett 587: 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle RA, Goldfine ID, Rosen MS, Taplitz RA, Williams JA (1985). Cholecystokinin bioactivity in human plasma. Molecular forms, responses to feeding, and relationship to gallbladder contraction. J Clin Invest 75: 1144–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CM, Obici S, Dong HH, Haas M, Lou D, Kim DH et al. (2011). Impaired insulin secretion and enhanced insulin sensitivity in cholecystokinin‐deficient mice. Diabetes 60: 2000–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1573–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milasta S, Evans NA, Ormiston L, Wilson S, Lefkowitz RJ, Milligan G (2005). The sustainability of interactions between the orexin‐1 receptor and beta‐arrestin‐2 is defined by a single C‐terminal cluster of hydroxy amino acids and modulates the kinetics of ERK MAPK regulation. Biochem J 387 (Pt 3): 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CD, Perry SJ, Regier DS, Prescott SM, Topham MK, Lefkowitz RJ (2007). Targeting of diacylglycerol degradation to M1 muscarinic receptors by beta‐arrestins. Science 315: 663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lam CM, Rajagopal S et al. (2011). Distinct phosphorylation sites on the beta(2)‐adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of beta‐arrestin. Sci Signal 4: ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, Davenport AP, McGrath JC, Peters JA, Southan C, Spedding M, Yu W, Harmar AJ; NC‐IUPHAR. (2014) The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (Database Issue): D1098–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SJ, Baillie GS, Kohout TA, McPhee I, Magiera MM, Ang KL et al. (2002). Targeting of cyclic AMP degradation to beta 2‐adrenergic receptors by beta‐arrestins. Science 298: 834–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoyer J, Longuet C, Broca C, Linck N, Costes S, Varin E et al. (2010). GLP‐1 mediates antiapoptotic effect by phosphorylating Bad through a beta‐arrestin 1‐mediated ERK1/2 activation in pancreatic beta‐cells. J Biol Chem 285: 1989–2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ (2010). Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven‐transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9: 373–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld JF, Friis‐Hansen L, Goetze JP, Hansen TV (2007). The biology of cholecystokinin and gastrin peptides. Curr Top Med Chem 7: 1154–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]