Abstract

Background and Purpose

α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7 nAChRs) may represent useful targets for cognitive improvement. The aim of this study is to compare the pro‐cognitive activity of selective α7‐nAChR ligands, including the partial agonists, DMXBA and A‐582941, as well as the positive allosteric modulator, 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide (PAM‐2).

Experimental Approach

The attentional set‐shifting task (ASST) and the novel object recognition task (NORT) in rats, were used to evaluate the pro‐cognitive activity of each ligand [i.e., PAM‐2 (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg·kg−1), DMXBA and A‐582941 (0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1)], in the absence and presence of methyllycaconitine (MLA), a selective competitive antagonist. To determine potential drug interactions, an inactive dose of PAM‐2 (0.5 mg·kg−1) was co‐injected with inactive doses of either agonist ‐ DMXBA: 0.1 (NORT); 0.3 mg·kg−1 (ASST) or A‐582941: 0.1 mg·kg−1.

Key Results

PAM‐2, DMXBA, and A‐582941 improved cognition in a MLA‐dependent manner, indicating that the observed activities are mediated by α7 nAChRs. Interestingly, the co‐injection of inactive doses of PAM‐2 and DMXBA or A‐582941 also improved cognition, suggesting drug interactions. Moreover, PAM‐2 reversed the scopolamine‐induced NORT deficit. The electrophysiological results also support the view that PAM‐2 potentiates the α7 nAChR currents elicited by a fixed concentration (3 μM) of DMXBA with apparent EC50 = 34 ± 3 μM and Emax = 225 ± 5 %.

Conclusions and Implications

Our results support the view that α7 nAChRs are involved in cognition processes and that PAM‐2 is a novel promising candidate for the treatment of cognitive disorders.

Abbreviations

- α7 nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with α7 subunit

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- apparent EC50

enhancement potency

- ASST

attentional set‐shifting task

- CD

compound discrimination

- DI

discrimination index

- E

exploration time

- ED

extra‐dimensional

- Emax

ligand efficacy

- ID

intra‐dimensional

- ITI

inter‐trial interval

- MLA

methyllycaconitine

- NORT

novel object recognition task

- nH

Hill coefficient

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PAM‐2

3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide

- Rev

reversal of discrimination

- SD

simple discrimination

- T1

familiarisation trial

- T2

retention trial

Tables of Links

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| A‐582941 | NS‐1738 |

| Dizocilpine | Phencyclidine |

| Donepezil | PNU‐120596 |

| MLA, methyllycaconitine | Scopolamine |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a b Alexander et al., 2013a, 2013b).

Introduction

The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7 nAChR) is a member of the Cys‐loop ligand‐gated ion channel family and these receptors are one of the most abundant subtypes expressed in brain areas such as the hippocampus, amygdala, midbrain, and prefrontal cortex, which are involved in important physiological functions such as memory, cognition, and different types of learning tasks (see Freedman, 2014). Important roles in the development of neurological diseases with cognitive impairments such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), schizophrenia, and Huntington's disease, have been assigned to these nAChRs as well. In this regard, a great effort has been made lately in the synthesis and functional characterization of selective α7 nAChR ligands, including agonists, antagonists, and positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) (Arias et al., 2010; Tietje et al., 2008; reviewed in: Freedman, 2014; Pohanka, 2012; Arias, 2011) as attempts to develop treatment for these diseases.

Allosteric modulation has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy with advantages over the orthosteric activation of α7 nAChRs (Uteshev, 2014; Williams et al., 2011). The structural diversity of allosteric sites allows for greater receptor selectivity. As PAMs do not directly activate nAChRs, the risk of overdosing is limited. Since PAMs do not compete with the agonist binding sites, this approach may be particularly beneficial in schizophrenic patients who usually smoke more tobacco than the general population. Furthermore, type II PAMs, which are less prone to cause prolonged α7 nAChR desensitisation and even reactivate desensitized nAChRs, do not produce the loss of function that may occur after the chronic administration of an agonist.

Recently, a series of PAMs with selectivity for the α7 nAChR has been synthesised and pharmacologically characterized (Arias et al., 2011). Among them, 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide (PAM‐2) presents antidepressant (Targowska‐Duda et al., 2014a; Arias et al., 2015), pro‐mnesic and anxiolytic (Targowska‐Duda et al., 2014b), and antinociceptive and anti‐inflammatory activity (Bagdas et al., 2015) in mice. To complete these preclinical studies, and to determine the pro‐cognitive activity of PAM‐ 2, two animal tests, namely the attentional set‐shifting task (ASST) (Nikiforuk et al., 2010) and the novel object recognition task (NORT) (Nikiforuk et al., 2013), were used with male rats.

The ASST is a rodent version of the Intra/Extra Dimensional set‐shifting task (Roberts et al., 1988) that assesses cognitive flexibility (i.e., the ability to modify behaviour in response to the altering relevance of stimuli). In this paradigm, rats must select a bowl containing a food reward based on the ability to discriminate the odours or the media covering the bait (Birrell & Brown, 2000). The ASST requires rats to initially learn a rule and form an attentional “set” within the same stimulus dimensions. At the extra‐dimensional (ED) shift stage, the essential phase of the task, animals must switch their attention to a previously irrelevant stimulus dimension and, for example, discriminate between the odours and not between the media covering the bait. The animal's performance at the ED stage is considered an index of cognitive flexibility and depends on the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Birrell & Brown, 2000).

The NORT in rodents has been increasingly used as an ethologically relevant paradigm for studying visual episodic memory (Ennaceur & Delacour, 1988). This task is based on the spontaneous exploration of novel and familiar objects. Successful object recognition is displayed by more time spent interacting with the novel object in the retention trial. Introducing longer inter‐trial intervals (e.g., 24 h in the present experiments) abolishes object discrimination. This delay‐induced deficit closely resembles natural forgetting.

The pro‐cognitive activity elicited by PAM‐2 was compared to that of two partial agonists with selectivity for the α7 nAChR, namely DMXBA (also named GTS‐21) (see Freedman, 2014) and A‐582941 (Tietje et al., 2008), and the observed drug activities challenged by the selective competitive antagonist, methyllycaconitine (MLA) (Arias et al., 2010). To determine whether drug interactions occur, the combination of drugs at inactive doses was also tested. Moreover, the ability of PAM‐2 to ameliorate the scopolamine‐induced object recognition deficit was assessed. Finally, electrophysiological experiments using SH‐SY5Y‐α7 cells were performed to determine the potentiation of DMXBA‐evoked α7 nAChR currents elicited by PAM‐2.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments, Institute of Pharmacology (Krakow, Poland). Studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total number of animals used in the experiments described here was 378.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, Germany), weighing 200–250 g on arrival, were housed in a temperature‐controlled (21 ± 1°C) and humidity‐controlled (40–50%) colony room under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 am). For the ASST experiments, rats were individually housed with a mild food restriction (17 g of food pellets per day) for at least one week prior to testing. For the NORT studies, rats were group‐housed (5 rats per cage) with free access to food and water. Behavioural testing was performed during the light phase of the light/dark cycle.

Attentional set‐shifting task (ASST)

A detailed description of the apparatus and procedure has been provided previously (Nikiforuk et al., 2010). Briefly, rats were presented with two ceramic pots, with only one pot baited with a food reward (Honey Nut Cheerio, Nestle®). Animals had to retrieve the Cheerio on the basis on their ability to discriminate the odours associated with the pot and the digging media that covered Cheerio bait in the pot.

The procedure entailed three days for each rat: habituation, training and testing. During a single test session, rats performed a series of 7 discriminations. In the simple discrimination involving only one stimulus dimension, the pots differed along one of two dimensions (e.g., digging medium). For the compound discrimination (CD), the second (irrelevant) dimension (i.e., odour) was introduced but the correct and incorrect exemplars of the relevant dimension remained constant. For the reversal of this discrimination (Rev 1), the exemplars and relevant dimension were unchanged but the previously correct exemplar was now incorrect and vice versa. The intra‐dimensional (ID) shift was then presented, consisting of new exemplars of both the relevant and irrelevant dimensions with the relevant dimension remaining the same as previously. The ID discrimination was then reversed (Rev 2) so that the formerly positive exemplar became the negative one. This series of discriminations serves to progressively form an attentional set. For the extra‐dimensional (ED) shift, a new pair of exemplars was again introduced, but this time a relevant dimension was also changed. At this essential phase of the task, animals must switch their attention to a previously irrelevant stimulus dimension and, for example, discriminate between the odours and not between the media covering the bait. Finally, the last phase was the reversal (Rev 3) of the ED discrimination. The first four trials at the beginning of each discrimination phase were a discovery period (not included in six trials to criteria). In subsequent trials, an incorrect choice was recorded as an error. All animals were tested once.

Novel object recognition task (NORT)

Apparatus

Rats were tested in a dimly lit (25 Lux) open field made of dull grey plastic (length x width x height: 66 x 56 x 30 cm).

Procedure

Rats were habituated to the arena (without any objects) for 5 min 24 h before testing (Nikiforuk et al., 2013). The test consisted of two 3‐min trials separated by an inter‐trial interval (ITI) of 24 h (or 60 min in the scopolamine study). During the first trial (familiarisation, T1), two identical objects (A1 and A2) were presented in opposite corners, approximately 10 cm from the walls of the open field. In the second trial (retention, T2), one of the objects was replaced by a novel one (A = familiar, and B = novel). The objects used were a glass bulb filled with gravel and a plastic bottle filled with sand. The height of the objects was comparable (~12 cm), and they were heavy enough to not be displaced by the animals. Half of the animals from each group received the glass bulb as a novel object, and the other half received the plastic bottle. The location of the novel object in the recognition trial was randomly assigned for each rat. Exploration of an object was defined by looking, licking, sniffing or touching the object while sniffing but not leaning against, standing or sitting on the object. Any rat that spent less than 5 s exploring the two objects within 3 min of T1 or T2 was eliminated from the study. The behaviour was recorded by the camera placed above the arena, and connected to the Any‐maze® tracking system (Stoelting Co., Illinois, USA), which measured automatically the distance travelled by an animal. The experimenter manually assessed exploratory activity of animals. Based on the exploration time (E) of the two objects in the retention trial, a discrimination index (DI) was calculated as (EB–EA)/(EA+EB). Each rat was tested twice, with a 7‐day washout period between each of two tests. No animal received the same treatment twice.

Drug administration

DMXBA (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), A‐582941 (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1) or PAM‐2 (0, 0.5 or 1.0 mg·kg−1 for the ASST, and 0, 1.0 or 2.0 mg·kg−1 for the NORT) were administered i.p. 30 min before testing, i.e. the acquisition trial (T1) of the NORT or first discrimination stage of the ASST. To determine receptor selectivity, DMXBA (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1) and PAM‐2 (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1 for the ASST, and 0 or 2.0 mg·kg−1 for the NORT) were administered with MLA (0 or 3.0 mg·kg−1; i.p.) 30 min before testing. In the case of A‐582941, rats received MLA (0 or 3.0 mg·kg−1) 30 min before the injection of the agonist (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), and after additional 30 min, the test was performed.

For the drug interaction study, rats were simultaneously injected with inactive doses of PAM‐2 (0 or 0.5 mg·kg−1) and DMXBA (0 or 0.3 mg·kg−1 for the ASST and 0 or 0.1 mg·kg−1 for the NORT) or/and A‐582941 (0 or 0.1 mg·kg−1) 30 min prior to testing. To determine receptor selectivity, MLA (3.0 mg·kg−1) was administered with DMXBA and PAM‐2 and after additional 30 min, the test was performed. In the case of A‐582941, rats received MLA (3.0 mg·kg−1) 30 min before the co‐injection of the agonist and PAM‐2. In the scopolamine study, PAM‐2 (1.0 and 2.0 mg·kg−1) was injected i.p., followed 30 min later by i.p. administration of scopolamine 1.25 mg·kg−1, and after additional 30 min, the test was performed.

Previous in vivo studies indicate that the i.p. administration of 1 µmol·kg−1 (~0.3 mg·kg−1) of A‐582941 produces a maximal concentration of 300 ng/g (~1 μM) in the brain, which is enough to activate α7 nAChRs (Tietje et al., 2008). Oral administration of DMXBA at a dose of 10 mg·kg−1 produces a peak concentration of 664 ng/g (>2 μM) in the brain (Mahnir et al., 1998). The i.p. administration of 6.2 µmol·kg−1 of MLA produces maximal brain levels of ~50‐100 nM, which is enough to inhibit α7 nAChRs (Turek et al., 1995). In addition, our initial pharmacokinetics experiments indicate that a brain concentration of ~0.2 μM of PAM‐2 is attained after the acute injection of 1.0 mg·kg−1 of the compound (unpublished results), which is enough to modulate α7 nAChRs.

Electrophysiological measurements in SH‐SY5Y‐α7 cells

The human neuroblastoma SH‐SY5Y cells were first stably transfected with the human α7 subunit expression plasmid using the SuperFect kit (Quiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Neomycin selection was initiated 48 h after transfection with 0.3 mg·ml−1 and reduced to 0.1 mg·ml−1 after appearance of single clones. About 10 SH‐SY5Y cell clones from this transfection showed specific 125I‐α‐bungarotoxin binding of >70%.

The SH‐SY5Y‐α7 cells overexpressing the α7 nAChR were cultured as described in Arias et al. (2011). More precisely, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 100 µg ml‐1 geneticin. The cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity, and passaged every 3 days by detaching the cells from the cell culture flask by washing with phosphate‐buffered saline and brief incubation (~3 min) with trypsin (0.5 mg·ml−1)/EDTA (0.2 mg·ml−1).

The patch‐clamp recordings were subsequently performed at room temperature in the whole‐cell configuration. During the experiments the cells were continuously perfused at 5 mL/min with standard solution (i.e., 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, and 20 mM sucrose, the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Patch electrodes had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ and were filled with 140 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES, 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM Na2ATP (the pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH). Cells were voltage clamped at −60 mV and access resistance was monitored throughout the recordings. Currents were amplified with an Axopatch 1D amplifier, filtered at 5 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz. Drugs were applied directly by gravity through a Y‐tube perfusion system. Drug application had a fast onset and achieved a complete local perfusion of the recorded cell. Application of 3 μM DMXBA produced a current characterized by a peak and its concomitant plateau that is reached after few milliseconds. Subsequently, the agonist and different concentrations of PAM‐2 (i.e., 1–300 μM) were applied, producing larger currents.

Data analysis

ASST

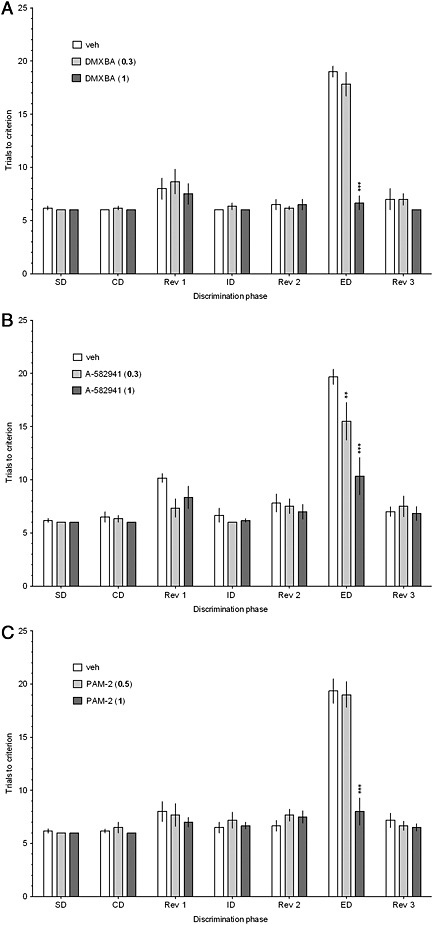

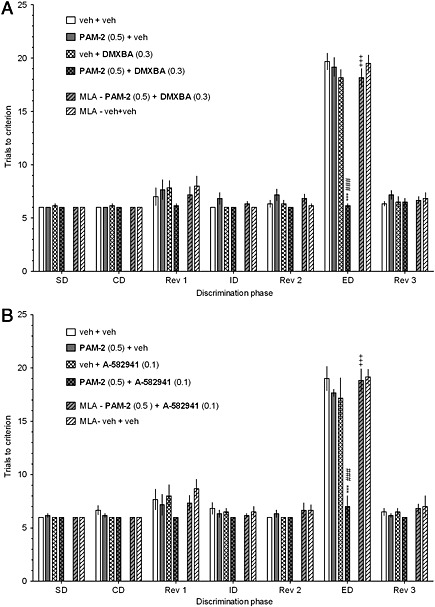

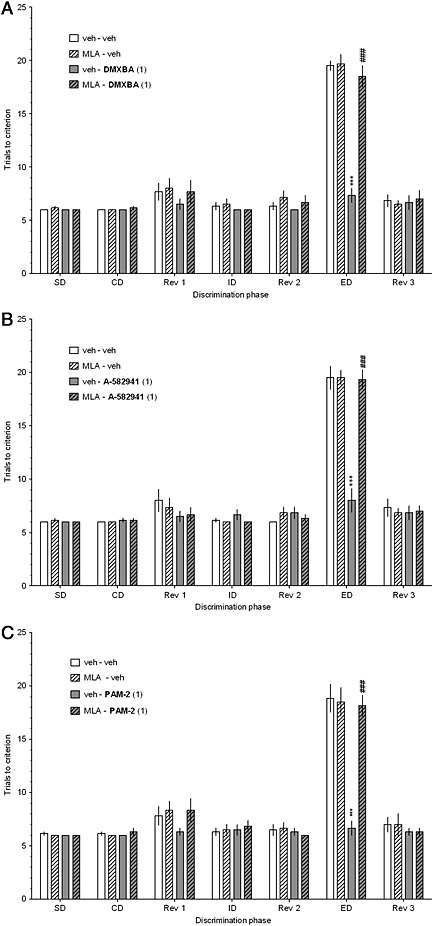

The number of trials required to achieve the criterion of 6 consecutive correct responses was recorded for each rat and for each discrimination phase of the ASST. Data presented in Figures 1a‐c and Figures 5a‐b were calculated using two‐way mixed‐design ANOVAs with the treatment as a between‐subject factor and the discrimination phase as a repeated measure. For the antagonist studies (Figures 3a‐c), data were analysed using three‐way mixed‐design ANOVAs with MLA and the respective drug treatment as between‐subject factors and the discrimination phase as a repeated measure.

Figure 1.

DMXBA (a), A‐582941 (b), and PAM‐2 (c) improve performance in the ASST. DMXBA (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), A‐582941 (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), or PAM‐2 (0, 0.5 or 1.0 mg·kg−1) was given i.p., 30 min before testing. The results represent the mean ± SEM. of a number of trials required to reach the criterion of 6 consecutive correct trials for each of the discrimination phases i.e., simple discrimination (SD), compound discrimination (CD), reversal 1 (Rev1), intradimensional shift (ID), reversal 2 (Rev 2), extradimensional shift (ED) and reversal 3 (Rev 3). N = 6 rats per group. ***p<0.001 and **p<0.01, significant improvement in ED performance compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group.

Figure 5.

The co‐administration of inactive doses of PAM‐2 with either DMXBA (a) or A‐582941 (b) facilitates performance in the ASST. PAM‐2 (0 or 0.5 mg·kg−1) was co‐injected with DMXBA (0 or 0.3 mg·kg−1) or A‐582941 (0 or 0.1 mg·kg−1) 30 min before testing. Results represent the mean ± SEM. of a number of trials required to reach the criterion of 6 consecutive correct trials for each of the discrimination phases, i.e., simple discrimination (SD), compound discrimination (CD), reversal 1 (Rev1), intradimensional shift (ID), reversal 2 (Rev 2), extradimensional shift (ED) and reversal 3 (Rev 3). N = 6 rats per group. ***p<0.001, significant improvement in ED performance compared to that for the vehicle+vehicle‐treated group. ###p<0.001, significant improvement in ED performance compared to that for the vehicle+DMXBA (a)‐ and vehicle+A‐582941 (b)‐treated group. +++p<0.001, significant reduction in ED performance compared to that for the PAM‐2+DMXBA (a)‐ or PAM‐2+A‐58294 (b)‐treated group.

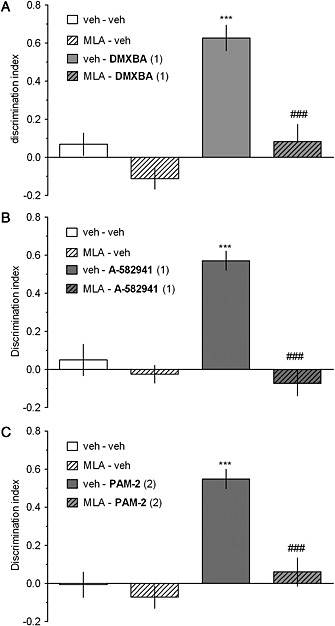

Figure 3.

Methyllycaconitine reverses the facilitation of ASST performance, elicited by DMXBA (a), A‐582941 (b), and PAM‐2 (c). Methyllycaconitine (MLA; 0 or 3.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.) was co‐administered with DMXBA (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.), A‐582941 (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.), or PAM‐2 (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.), 30 min before testing. The results represent the mean ± SEM number of trials required to reach the criterion of 6 consecutive correct trials for each of the discrimination phases i.e., simple discrimination (SD), compound discrimination (CD), reversal 1 (Rev1), intradimensional shift (ID), reversal 2 (Rev 2), extradimensional shift (ED) and reversal 3 (Rev 3). N = 6 rats per group. ***p<0.001, significant improvement in ED performance compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group. ###p<0.001, significant reduction in ED performance compared to that for the DMXBA (a)‐, A‐582941 (b)‐, or PAM‐2 (c)‐treated group.

NORT

Data on exploratory preference were analysed using two‐way (or three‐way for the MLA studies) mixed‐design ANOVAs with the respective drug treatment as between‐subject factors and the object as a repeated measure. DI data were analysed by one‐way (or two‐way for the MLA studies) ANOVAs. Because the analyses of exploration time during retention trial (T2) and DI yielded the same results, only DI data were presented. Distance travelled was analysed using mixed‐design ANOVAs (two‐ or three‐way for the MLA studies) with the respective drug treatments as between‐subject factors and trial as a repeated measure. As there were no significant differences in the time spent exploring two identical objects in the acquisition phase in any drug‐treated group and no significant treatment effects on the distance travelled by rats in the familiarisation and retention trials, these data are not presented.

Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Newman‐Keuls test. The α‐value was set at P<0.05 level. The data fulfilled criteria of normal distribution. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Statistica 10.0 for Windows.

Electrophysiological measurements

The concentration‐potentiation relationship for PAM‐2 was determined by using non‐linear regression (GraphPad‐Prism software, CA, USA), by fitting the experimental data into the modified Hill equation:

| (1) |

where IDMXBA is the response to 3 μM DMXBA, IPAM‐2 is the response to 3 μM DMXBA in the presence of different concentrations of PAM‐2 (i.e., [PAM‐2]), apparent EC50 is the concentration of PAM‐2 producing half‐maximal potentiation, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Materials

PAM‐2, synthesised as described by Bagdas et al. (2015), was suspended in 1% Tween 80 (Sigma–Aldrich, Poznan, Poland) in saline solution, whereas A‐582941, DMXBA (GTS‐21) (Tocris, Bristol, UK) and scopolamine (Sigma–Aldrich, Poznan, Poland) were dissolved in distilled water. Methyllycaconitine citrate (MLA) (Ascent Scientific, Bristol, UK) was dissolved in distilled water, and the solution was neutralised with 0.1 N NaOH. Drugs or vehicle (physiological saline) were administered in a volume of 1 mL·kg−1 of body weight. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and trypsin/EDTA were purchased from Gibco BRL (Paisley, UK). Geneticin and neomycin were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). Salts were of analytical grade.

Results

The pro‐cognitive effects of DMXBA, A‐582941 and PAM‐2

ASST

Two‐way mixed‐design ANOVAs revealed significant interactions between the discrimination phase and respective drug treatment: F [12,90] = 22.39, p <0.001 (DMXBA,Figure 1a), F [12,90] = 6.01, p<0.001 (A‐582941, Figure 1b) and F[12,90] =13.99, p<0.001 (P AM‐2, Figure 1c).

Post hoc analysis revealed that the acute administration of DMXBA (1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 1a), A‐582941 (0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 1b), and PAM‐2 (1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 1c) significantly and specifically enhanced rats’ cognitive flexibility, as indicated by a reduced number of trials to criterion during the ED stage of the ASST. There was no significant drug effect during any other discrimination stage.

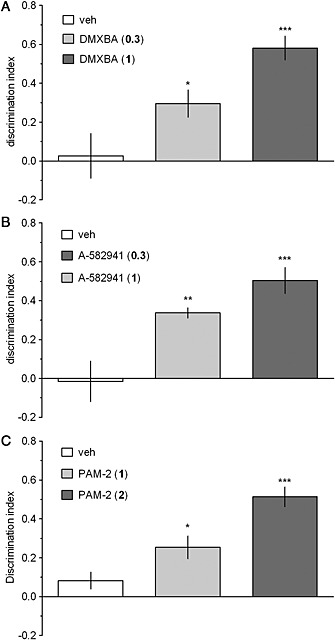

NORT

In the retention trial, vehicle‐treated rats did not discriminate the novel object from the familiar one and this time‐induced natural forgetting was ameliorated by DMXBA (Figure 2a), A‐582941 (Figure 2b), and PAM‐2 (Figure 2c). Accordingly, one‐way ANOVAs revealed a significant effect of drug treatment on the DI measures: F[2,24]=10.85, p<0.001 (DMXBA, Figure 2a), F[2,24]=14.71, p<0.001 (A‐582941, Figure 2b), and F[2,24]=16.38, p<0.001 (PAM‐2, Figure 2c). Post hoc analyses demonstrated that DMXBA (0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 2a), A‐582941 (0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 2b), and PAM‐2 (1.0 and 2.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 2c) significantly increased DI compared to the controls.

Figure 2.

DMXBA (a), A‐582941 (b), and PAM‐2 (c) improve performance in the NORT. DMXBA (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), A‐582941 (0, 0.3 or 1.0 mg·kg−1), or PAM‐2 (0, 1.0 or 2.0 mg·kg−1) was given i.p., 30 min before T1 (acquisition trial). T2 (retention trial) was performed 24 h after T1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of discrimination index (DI) during T2. N = 7–10 rats per group. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, and *p<0.05, significant increase in DI compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group.

The α7 nAChR antagonist, methyllycaconitine, reverses the pro‐cognitive effects of DMXBA, A‐582941, and PAM‐2

ASST

The selective α7 nAChR antagonist, MLA (3.0 mg·kg−1), blocked the pro‐cognitive effects of active doses of DMXBA (1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 3a), A‐582941 (1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 3b), and PAM‐2 (1.0 mg·kg−1, Figure 3c). However, MLA did not affect performance at any of the ASST stages when co‐administered with a vehicle. Three‐way mixed‐design ANOVAs revealed significant interactions among the discrimination phase, MLA and the respective drug treatment: F[6,120]=14.91, p<0.001 (DMXBA, Figure 3a), F[6,120]=12.56, p<0.001 (A‐582941, Figure 3b), and F[6,120]=12.56, p<0.001 (PAM‐2, Figure 3c).

NORT

As shown in Figure 4a‐c, the DI in rats co‐treated with MLA (3.0 mg·kg−1) and either DMXBA (1.0 mg·kg−1), A‐582941 (1.0 mg·kg−1), or PAM‐2 (2.0 mg·kg−1) was significantly lower than that in groups treated with the respective compound alone. Thus, MLA blocked the pro‐cognitive effects of the tested compounds. Two‐way ANOVA interactions between MLA and the respective drug treatment revealed the following results: F[1,34]=7.14, p<0.05 (DMXBA, Figure 4a), F[1,34]=21.19, p<0.001 (A‐582941, Figure 4b), and F[1,34]=11.42, p<0.01, (PAM‐2, Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Methyllycaconitine reverses the facilitation of NORT performance, elicited by DMXBA (a), A‐582941 (b), and PAM‐2 (c). Methyllycaconitine (MLA; 0 or 3.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.) was co‐administered with DMXBA (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.), A‐582941 (0 or 1.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.), or PAM‐2 (0 or 2.0 mg·kg−1, i.p.) 30 min before T1 (acquisition trial). T2 (retention trial) was performed 24 h after T1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of discrimination index (DI) during T2. N = 9–10 rats per group. ***p<0.001, significant increase in DI compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group. ###p<0.001, significant reduction in DI compared to that for the DMXBA (a)‐, A‐58294 (b)‐, or PAM‐2 (c)‐treated group.

The co‐administration of inactive doses of PAM‐2 with either DMXBA or A‐582941 facilitates cognitive performance

ASST

The co‐administration of inactive doses of PAM‐2 (0.5 mg·kg−1) with either DMXBA (0.3 mg·kg−1; Figure 5a) or A‐582941 (0.1 mg·kg−1; Figure 5b) to rats reduced the number of trials to criterion in the ED phase as compared to the vehicle/vehicle‐treated group and to the vehicle/DMXBA‐ (Figure 5a) or vehicle/A‐582941‐treated (Figure 5b) groups. The pro‐cognitive effects of the drug combinations were blocked by MLA (Figures 5a‐b), indicating that the observed effects are α7 nAChR‐dependent.

NORT

The co‐administration of inactive doses of PAM‐2 (0.5 mg·kg−1) with either DMXBA (0.1 mg·kg−1, Figure 6a) or A‐582941 (0.1 mg·kg−1, Figure 6b) augmented the rats’ ability to discriminate the novel object from the familiar object in the retention trial. The DI in rats co‐treated with PAM‐2 and either DMXBA (F[5,54]=9.31, p<0.001, Figure 6a) or A‐582941 (F[5,54]=25.35, p<0.001, Figure 6b) was significantly higher than that for the vehicle‐treated (control) and drug (alone)‐treated rats. Interestingly, MLA (3.0 mg·kg−1) blocked the pro‐cognitive effects of the drug combinations (Figures 6a‐b).

Figure 6.

The co‐administration of inactive doses of PAM‐2 with either DMXBA (a) or A‐582941 (b) facilitates performance in the NORT. PAM‐2 (0 or 0.5 mg·kg−1) was co‐injected with DMXBA (0 or 0.1 mg·kg−1) or A‐582941 (0 or 0.1 mg·kg−1) 30 min before T1 (acquisition trial). T2 (retention trial) was performed 24 h after T1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of discrimination index (DI) during T2. Symbols: ***p<0.001 significant increase in DI compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group; ###p<0.001 significant increase in DI compared to that for the vehicle+DMXBA (a)‐ or vehicle+A‐582941 (b) ‐ group. +++p<0.001, significant reduction in DI compared to that for the PAM‐2+DMXBA (a)‐ or PAM‐2+A‐582941 (b)‐treated group.

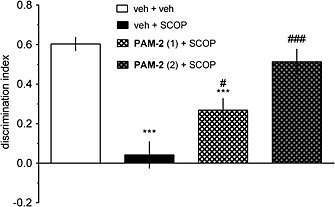

PAM‐2 reverses the scopolamine‐induced object recognition deficit

As demonstrated in Figure 7, the administration of scopolamine abolished the ability to discriminate novel and familiar objects (one‐way ANOVA: F[3.36]=18.41, p<0.001). PAM‐2 (1.0 and 2.0 mg·kg−1) significantly attenuated the observed scopolamine‐induced DI reduction.

Figure 7.

PAM‐2 reverses the scopolamine‐induced deficits in the NORT. PAM‐2 (1.0 and 2.0 mg·kg−1) was given i.p., followed 30 min later by i.p. administration of scopolamine (SCOP; 1.25 mg·kg−1). T1 (acquisition trial) was performed 30 min after scopolamine administration, and T2 (retention trial) was performed 60 min after T1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of discrimination index (DI) during T2. ***p<0.001, significant reduction in DI compared to that for the vehicle‐treated group. ###p<0.001 and #p<0.05, significant increase in DI compared to that for the SCOP‐treated group.

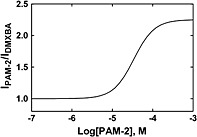

PAM‐2 enhances the α7 nAChR activity elicited by DMXBA

The electrophysiological results indicated that PAM‐2 enhances the activity elicited by a fixed concentration (3 μM) of DMXBA, a selective α7 nAChR partial agonist (Figure 8). The observed plateau current elicited by 3 μM DMXBA on α7 nAChRs was considered the control value (IDMXBA). Increasing concentrations of PAM‐2 (i.e., 1–300 μM) potentiated the initial current (IPAM‐2), reaching an Emax value of 225 ± 5 %. This value is practically the same as that determined by Ca2+ influx experiments (204 ± 13 %), where (±)‐epibatidine was used as the agonist (Arias et al., 2011). The concentration‐response curve gave an apparent potentiating EC50 value of 34 ± 3 μM, which is larger than that determined previously by Ca2+ influx assays (~5 μM; (Arias et al., 2011). Several possible causes might account for this difference: (1) methodological differences between the used electrophysiological (this paper) and Ca2+ influx (Arias et al., 2011) techniques, (2) the use of different cell types: GH3‐α7 cells for the Ca2+ influx assays (Arias et al., 2011) vs. the SH‐SY5Y‐α7 cells for this study, (3) the use of a very low initial concentration of (±)‐epibatidine (EC5 = 20 nM) for the Ca2+ influx experiments (Arias et al., 2011) compared to the used concentration of DMXBA (3 μM) which corresponds approximately to its EC25 value (Papke & Porter Papke, 2002). This possibility is supported by the fact that at a higher concentration of DMXBA (10 μM), the potentiation elicited by 100 μM PAM‐2 was 175 ± 28 % (n = 4), a value slightly lower than that using 3 μM DMXBA (i.e., 212 ± 20 %; see Figure 8), and finally, (3) that the used PAM‐2 was synthetized by a new method which yields molecules with slightly less activity (Bagdas et al., 2015). On the other hand, the fact that the calculated nH value (1.71 ± 0.23) is higher than unity suggests cooperative interactions for PAM‐2, as was described previously (Arias et al., 2011;Bagdas et al., 2015).

Figure 8.

PAM‐2 enhances DMXBA‐evoked α7 nAChR currents. SH‐SY5Y‐α7 cells were initially treated with a fixed concentration of DMXBA (3 μM) (n = 27), and the observed plateau current was considered the control (IDMXBA). To determine the potentiating effect of PAM‐2, increasing concentrations of PAM‐2 (1–300 μM; n = 4–8) were tested on the DMXBA‐evoked α7 nAChR currents (IPAM‐2). The concentration‐response data were analysed by non‐linear regression, according to Eq. (1). The results indicated that PAM‐2 potentiates DMXBA‐evoked α7 nAChR currents with apparent EC50 = 34 ± 3 μM, Emax = 225 ± 5 %, nH = 1.71 ± 0.23, and goodness of fit r2 = 0.997.

Discussion

The present study demonstrate that PAM‐2, a selective α7 nAChR PAM, as well as DMXBA and A‐582941, selective α7 nAChR agonists, facilitate cognitive flexibility, as assessed by the ASST, and attenuate the delay‐induced impairment in NORT performance in rats. As MLA, a selective α7 nAChR competitive antagonist, fully blocked the pro‐cognitive effects mediated by the tested compounds, we inferred that the observed activities are mediated by α7 nAChRs. Interestingly, the co‐injection of inactive doses of PAM‐2 and DMXBA or A‐582941 also improved rats’ performance on the ASST and NORT in a MLA‐dependent manner, suggesting agonist‐PAM synergism.

The observed effects of α7 nAChR ligands in the ASST corroborate previous results suggesting an involvement of the nicotinic receptor system in processes underlying cognitive flexibility. Accordingly, Allison and Shoaib (2013) demonstrated that either sub‐chronic or acute administration of nicotine improves rat performance on the ASST. Although α7−/− mice did not demonstrate impaired performance on the ASST (Young et al., 2011), recent preclinical data suggest that an approach based on α7 nAChR stimulation may be useful in treating schizophrenia‐like cognitive inflexibility in the neurodevelopmental or NMDA receptor blockade‐based model. Likewise, acute administration of RG3487 and SSR180711, two other α7 nAChR partial agonists, reversed ED deficits in rats sub‐chronically treated with the NMDA receptor antagonist, phencyclidine (Wallace et al., 2011), and in rats with transient inactivation of the neonatal ventral hippocampus (Brooks et al., 2012), respectively. DMXBA, used in our experiments, has been also demonstrated to be effective in alleviating dizocilpine‐evoked deficits in a rat maze‐based strategy set‐shifting paradigm (Jones et al., 2014). However, the active dose of DMXBA was much higher (i.e., 30 mg·kg−1) than that used in the current experiments (i.e., 1.0 mg·kg−1). This discrepancy may arise from differences in the applied paradigm (perceptual vs strategy set shifting) or in the testing condition (cognitively unimpaired vs impaired animals). In addition, such high doses may produce enough endogenous concentrations to inhibit non‐α7 nAChRs. To our knowledge, A‐582941 has not been evaluated in any set‐shifting procedure.

Less is known about the effects of α7 nAChR PAMs on set‐shifting performance, and the only published data in this regard concern to PNU‐120596. This type II α7‐selective PAM was effective in reversing sub‐chronic phencyclidine‐induced ED set‐shifting deficits on the ASST (McLean et al., 2012). Hence, our study supports the involvement of α7 nAChRs in the modulation of cognitive flexibility by demonstrating that selective agonists, DMXBA and A‐582941, as well as PAM‐2, a selective α7‐PAM, facilitate set‐shifting performance in cognitively unimpaired control rats. These effects were blocked by MLA, a selective α7 nAChR competitive antagonist, supporting the notion that the observed drug activities are mediated by α7 nAChRs. However, a direct comparison of our findings to other studies is not possible because most of the previous experiments did not include α7 nAChR agonist‐treated control rats (Wallace et al., 2011; McLean et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2014). As relatively high levels of performance were achieved in those studies (Brooks et al., 2012), further improvement could not be accomplished.

Our results also demonstrated that the efficacy of PAM‐2 to enhance rats’ object recognition memory is comparable to those mediated by the partial agonists, DMXBA and A‐582941. The effectiveness of α7 nAChR agonists has been widely documented in NORT studies (Lyon et al., 2012). In line with our data, Callahan et al. (2014) demonstrated that DMXBA (1–10 mg·kg−1) enhanced rats’ object recognition memory at the 48 h delay and that this effect was antagonised by MLA in a dose‐dependent manner (1.25 and 5 mg·kg−1). Moreover, A‐582941 (at doses <0.3 mg·kg−1) improved recognition memory in the social discrimination task in rats (Bitner et al., 2007).

Although α7 nAChR PAMs have been demonstrated to be effective against the pharmacologically induced deficits of object recognition (Pandya & Yakel, 2013;Eskildsen et al., 2014), the restoration of delay‐induced forgetting by this class of compounds has not been demonstrated. In contrast to the effectiveness of PAM‐2 in alleviating spontaneous forgetting, Callahan et al. (2013) showed that PNU‐120596 did not have a significant effect on Sprague–Dawley rats’ NORT performance when tested with a 48 h delay. However, the combination of PNU‐120596 with a subthreshold dose of donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used for the treatment of AD, reversed delay‐induced forgetting in that task (Callahan et al., 2013).

Our result also demonstrated that PAM‐2 reversed object recognition impairment induced by scopolamine, a pharmacological model of cholinergic deficits known to be associated with AD. These results are corroborated by the previous study demonstrating that PAM‐2 was also effective against the scopolamine‐induced impairment in the passive avoidance test in mice (Targowska‐Duda et al., 2014b). In line with these data, PNU‐120596 restored object recognition memory in scopolamine treated rats (Pandya & Yakel, 2013), and another α7 nAChR PAM, NS‐1738, reversed scopolamine‐induced deficits in the Morris water maze task in rats (Timmermann et al., 2007). Several studies demonstrated the efficacies of α7 nAChR agonists against AD‐like pathology. For example, DMXB ameliorated the spatial memory deficits induced by i.c.v injection of β‐amyloid25–35 to mice (Chen et al., 2010). Moreover, A‐582941 restored learning and memory in aged 3xTg‐AD mice with robust AD‐like pathology (Medeiros et al., 2014). Determining the efficacy of α7 nAChR PAMs awaits further studies.

The electrophysiological results indicated that PAM‐2 potentiates DMXBA‐evoked α7 nAChR activity. Studies in hippocampal interneurons demonstrated that either PAM‐2 (Arias, unpublished experiments) or PNU‐120596 (Lopez‐Hernandez et al., 2009) potentiates the activity of 4OH‐DMXBA, an active DMXBA metabolite with selectivity for the α7 nAChR. These results fit very well with our behavioural results showing that the co‐administration of an inactive dose of PAM‐2 with either DMXBA or A‐582941 enhanced cognitive flexibility and recognition memory in rats in a MLA‐dependent manner. Our results in the NOR test, in turn, are in agreement with studies using passive avoidance tests, showing that PAM‐2 improves memory consolidation and that nicotine potentiates the pro‐mnesic activity elicited by PAM‐2 (Targowska‐Duda et al., 2014b). Taking together, these results support the view that the pro‐cognitive and pro‐mnesic activity elicited by PAM‐2 alone or in combination with agonists are mediated by α7 nAChRs.

One may notice that the dose response‐relationship to PAM‐2 is very steep. A similar trend was observed for the activity of PAM‐2 on memory acquisition determined by the passive avoidance test (Targowska‐Duda et al., 2014b). More precisely, 1.0, but not 0.5, mg·kg−1 of PAM‐2 increased memory acquisition. Likewise, another α7 nAChR PAM, CCMI, exerted pro‐cognitive effects at a dose of 1 mg·kg−1 but was inactive when administered at a dose of 0.3 mg·kg−1 (Nikiforuk et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the dose of 0.5 mg·kg−1 PAM‐2 was effective when co‐administered with α7 nAChR agonists. A possibility is that the attained brain concentration at 0.5 mg·kg−1 PAM‐2 is not enough to modulate endogenous ACh‐activated α7 nAChRs. Alternatively, the cognitive‐enhancing effects of a lower dose of PAM‐2 may be revealed in cognitively‐impaired animals, in which the level of performance is low enough to allow for further improvement.

A wide body of evidence suggests that α7 nAChRs are involved in the modulation of the release of a number of neurotransmitters that have been implicated in cognitive functions such as glutamate, GABA, and dopamine (Bencherif et al., 2012). Alternatively, stimulation of α7 nAChRs may activate signalling pathways known to be involved in cognitive functions. For example, Bitner et al. (2007) demonstrated that the pro‐cognitive efficacy of A‐582941 correlates with increases in extracellular‐signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and cAMP response element‐binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation. Interestingly, the chronic treatment with 0.5 mg·kg−1 PAM‐2 also increases ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the mouse hippocampus, a brain area involved in memory and cognition (paper in preparation).

The present study demonstrates the role of α7 nAChRs on recognition memory and cognitive flexibility in rat preclinical tasks, as well as the ability of α7 nAChR ligands to enhance these important functions. The pro‐cognitive efficacy of PAM‐2 is comparable to those of orthosteric agonists. Thus, PAM‐2, alone or in combination with lower doses of selective agonists, is likely to represent a useful pharmacological approach for cognitive enhancement. The compound's efficacy against disease‐like cognitive impairments awaits further studies.

Authors contributions

AP, AN and TK carried out behavioural tests. FR and GP performed electrophysiological study. AN, HRA and PP conceived the study. AN and HRA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PP contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Polish National Science Centre grant NCN 2012/07/B/NZ/01150 and the Statutory Activity of the Institute of Pharmacology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, Poland.

Potasiewicz, A. , Kos, T. , Ravazzini, F. , Puia, G. , Arias, H. R. , Popik, P. , and Nikiforuk, A. (2015) Pro‐cognitive activity in rats of 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide, a positive allosteric modulator of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172: 5123–5135. doi: 10.1111/bph.13277.

References

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al. (2013a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1582–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1797–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison C, Shoaib M (2013). Nicotine improves performance in an attentional set shifting task in rats. Neuropharmacology 64: 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR (2011). Allosteric modulation of nicotine acetylcholine receptors In: Arias HR. (ed.). Pharmacology of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors from the Basic and Therapeutic Perspectives. E. Research Signpost: Kerala, India, pp. 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Gu RX, Feuerbach D, Wei DQ (2010). Different interaction between the agonist JN403 and the competitive antagonist methyllycaconitine with the human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry 49: 4169–4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Targowska‐Duda KM, Feuerbach D, Jozwiak K (2015). The antidepressant‐like activity of nicotine, but not of 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide, is regulated by the nicotinic receptor β4 subunit. Neurochem Int 87: 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Gu RX, Feuerbach D, Guo BB, Ye Y, Wei DQ (2011). Novel positive allosteric modulators of the human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry 50: 5263–5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdas D, Targowska‐Duda KM, Lopez JJ, Perez EG, Arias HR, Damaj MI (2015). Antinociceptive and anti‐inflammatory properties of 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide (PAM‐2), a positive allosteric modulator of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, in mice. Anesth Analg. In press [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 26280585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencherif M, Stachowiak MK, Kucinski AJ, Lippiello PM (2012). α7 nicotinic cholinergic neuromodulation may reconcile multiple neurotransmitter hypotheses of schizophrenia. Med Hypotheses 78: 594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ (2000). Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci 20: 4320–4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner RS, Bunnelle WH, Anderson DJ, Briggs CA, Buccafusco J, Curzon P et al. (2007). Broad‐spectrum efficacy across cognitive domains by α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonism correlates with activation of ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation pathways. J Neurosci 27: 10578–10587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JM, Pershing ML, Thomsen MS, Mikkelsen JD, Sarter M, Bruno JP (2012). Transient inactivation of the neonatal ventral hippocampus impairs attentional set‐shifting behavior: reversal with an α7 nicotinic agonist. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 2476–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan PM, Terry AV Jr, Tehim A (2014). Effects of the nicotinic α7 receptor partial agonist GTS‐21 on NMDA‐glutamatergic receptor related deficits in sensorimotor gating and recognition memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 3695–3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan PM, Hutchings EJ, Kille NJ, Chapman JM, Terry AV Jr (2013). Positive allosteric modulator of α7 nicotinic‐acetylcholine receptors, PNU‐120596 augments the effects of donepezil on learning and memory in aged rodents and non‐human primates. Neuropharmacology 67: 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang H, Zhang Z, Li Z, He D, Sokabe M et al. (2010). DMXB (GTS‐21) ameliorates the cognitive deficits in beta amyloid(25‐35(−)) injected mice through preventing the dysfunction of alpha7 nicotinic receptor. J Neurosci Res 88: 1784–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Delacour J (1988). A new one‐trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav Brain Res 31: 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen J, Redrobe JP, Sams AG, Dekermendjian K, Laursen M, Boll JB et al. (2014). Discovery and optimization of Lu AF58801, a novel, selective and brain penetrant positive allosteric modulator of alpha‐7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Attenuation of subchronic phencyclidine (PCP)‐induced cognitive deficits in rats following oral administration. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 24: 288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R (2014). α7‐nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Med 65: 245–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KM, McDonald IM, Bourin C, Olson RE, Bristow LJ, Easton A (2014). Effect of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists on attentional set‐shifting impairment in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez‐Hernandez GY, Thinschmidt JS, Morain P, Trocme‐Thibierge C, Kem WR, Soti F et al. (2009). Positive modulation of alpha7 nAChR responses in rat hippocampal interneurons to full agonists and the alpha7‐selective partial agonists, 4OH‐GTS‐21 and S 24795. Neuropharmacology 56: 821–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon L, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ (2012). Spontaneous object recognition and its relevance to schizophrenia: a review of findings from pharmacological, genetic, lesion and developmental rodent models. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 220: 647–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnir V, Lin B, Prokai‐Tatrai K, Kem WR (1998). Pharmacokinetics and urinary excretion of DMXBA (GTS‐21), a compound enhancing cognition. Biopharm Drug Dispos 19: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1573–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SL, Idris NF, Grayson B, Gendle DF, Mackie C, Lesage AS et al. (2012). PNU‐120596, a positive allosteric modulator of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reverses a sub‐chronic phencyclidine‐induced cognitive deficit in the attentional set‐shifting task in female rats. J Psychopharmacol 26: 1265–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros R, Castello NA, Cheng D, Kitazawa M, Baglietto‐Vargas D, Green KN et al. (2014). α7 Nicotinic receptor agonist enhances cognition in aged 3xTg‐AD mice with robust plaques and tangles. Am J Pathol 184: 520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforuk A, Golembiowska K, Popik P (2010). Mazindol attenuates ketamine‐induced cognitive deficit in the attentional set shifting task in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 20: 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforuk A, Kos T, Potasiewicz A, Popik P (2015). Positive allosteric modulation of alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors enhances recognition memory and cognitive flexibility in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25: 1300–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforuk A, Kos T, Fijal K, Holuj M, Rafa D, Popik P (2013). Effects of the selective 5‐HT7 receptor antagonist SB‐269970 and amisulpride on ketamine‐induced schizophrenia‐like deficits in rats. PLoS One 8: e66695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya AA, Yakel JL (2013). Activation of the α7 nicotinic ACh receptor induces anxiogenic effects in rats which is blocked by a 5‐HT(1)a receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology 70: 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Porter Papke JK (2002). Comparative pharmacology of rat and human alpha7 nAChR conducted with net charge analysis. Br J Pharmacol 137: 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (Database Issue): D1098–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohanka M (2012). Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is a target in pharmacology and toxicology. Int J Mol Sci 13: 2219–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (1988). The effects of intradimensional and extradimensional shifts on visual discrimination learning in humans and non‐human primates. Q J Exp Psychol B 40: 321–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targowska‐Duda KM, Feuerbach D, Biala G, Jozwiak K, Arias HR (2014a). Antidepressant activity in mice elicited by 3‐furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide, a positive allosteric modulator of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neurosci Lett 569: 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targowska‐Duda KM, Budzynska B, Jozwiak K, Biała G, Arias HR (2014b). 3‐Furan‐2‐yl‐N‐p‐tolyl‐acrylamide, a positive allosteric modulator of α7 nicotinic receptors produces pro‐cognitive, antidepressant, and anxiolytic activities in mice. In 3rd Welcome Trust conference on Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Cambridge, UK, July 23–26, 2014.

- Tietje KR, Anderson DJ, Bitner RS, Blomme EA, Brackemeyer PJ, Briggs CA et al. (2008). Preclinical characterization of A‐582941: a novel alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptor agonist with broad spectrum cognition‐enhancing properties. CNS Neurosci Ther 14: 65–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann DB, Gronlien JH, Kohlhaas KL, Nielsen EO, Dam E, Jorgensen TD et al. (2007). An allosteric modulator of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor possessing cognition‐enhancing properties in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323: 294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek JW, Kang CH, Campbell JE, Arneric SP, Sullivan JP (1995). A sensitive technique for the detection of the alpha 7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist, methyllycaconitine, in rat plasma and brain. J Neurosci Methods 61: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uteshev VV (2014). The therapeutic promise of positive allosteric modulation of nicotinic receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 727: 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TL, Callahan PM, Tehim A, Bertrand D, Tombaugh G, Wang S et al. (2011). RG3487, a novel nicotinic alpha7 receptor partial agonist, improves cognition and sensorimotor gating in rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336: 242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DK, Wang J, Papke RL (2011). Positive allosteric modulators as an approach to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor‐targeted therapeutics: advantages and limitations. Biochem Pharmacol 82: 915–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Meves JM, Tarantino IS, Caldwell S, Geyer MA (2011). Delayed procedural learning in α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav 10: 720–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]