The microtubule catastrophe-promoting complex Sentin-EB1 delays stable kinetochore–microtubule attachment and facilitates bipolar attachment of homologous chromosomes in Drosophila oocytes.

Abstract

The critical step in meiosis is to attach homologous chromosomes to the opposite poles. In mouse oocytes, stable microtubule end-on attachments to kinetochores are not established until hours after spindle assembly, and phosphorylation of kinetochore proteins by Aurora B/C is responsible for the delay. Here we demonstrated that microtubule ends are actively prevented from stable attachment to kinetochores until well after spindle formation in Drosophila melanogaster oocytes. We identified the microtubule catastrophe-promoting complex Sentin-EB1 as a major factor responsible for this delay. Without this activity, microtubule ends precociously form robust attachments to kinetochores in oocytes, leading to a high proportion of homologous kinetochores stably attached to the same pole. Therefore, regulation of microtubule ends provides an alternative novel mechanism to delay stable kinetochore–microtubule attachment in oocytes.

Introduction

Meiosis is a special cell division that differs from mitosis in many aspects. The key event is to establish stable bipolar attachment of homologous chromosomes. For more than a decade, it has been known in mouse oocytes that stable attachments of microtubule ends to kinetochores are not established for hours after nuclear envelope breakdown (Brunet et al., 1999). This delay is likely to help prevent incorrect attachment before the formation of a bipolar spindle, which requires several hours because of the lack of centrosomes. This process was studied at a higher resolution, revealing that each kinetochore undergoes multiple biorientation attempts before stable bipolar attachment (Kitajima et al., 2011). It was shown that a slow increase of Cdk1 activity in oocytes delays kinetochore–microtubule attachments (Davydenko et al., 2013). Most recently, it was shown that phosphorylation of kinetochore proteins by Aurora B/C is responsible for this delay, and gradual increase of the Cdk1 activity induces PP2A-B56 recruitment to kinetochores to stabilize the attachments (Yoshida et al., 2015). Therefore, phosphoregulation of kinetochore proteins is a key mechanism to delay stable attachment in mouse oocytes.

Fine-tuning of kinetochore–microtubule attachment requires precise control of microtubule plus end dynamics and regulation of kinetochore proteins. In recent years, great advances have been made in understanding how the kinetochore complex is assembled and interacts with dynamic microtubule ends (Cheeseman, 2014). In contrast, less attention has been paid to regulation of microtubule ends. One of the critical regulators of microtubule plus ends is the conserved protein EB1, which can track growing microtubule plus ends and recruits many microtubule regulators to plus ends.

Sentin (also known as Ssp2; Goshima et al., 2007) was shown to be a major EB1 effector in a Drosophila melanogaster S2 cell line (Li et al., 2011). Sentin is recruited to microtubule plus ends by EB1, and its depletion increases microtubule pausing in cultured cells (Li et al., 2011). Sentin also enhances the association of the microtubule polymerase Mini spindles (Msps), the XMAP215 orthologue, to the microtubule plus ends. These properties are shared with mammalian SLAIN2 (van der Vaart et al., 2011), a potential functional homologue of Sentin. In vitro reconstitution from pure proteins demonstrated that Sentin, together with EB1, increases the microtubule growth rate and catastrophe frequency (Li et al., 2012). Additionally, in combination with Msps, the Sentin–EB1 complex synergistically increases microtubule growth rates and also promotes rescue. The importance of Sentin in microtubule regulation was shown in S2 cells and in vitro, but Sentin has not previously been studied in a whole organism.

In this study, we examined the role of Sentin in Drosophila oocytes. Little is known in Drosophila oocytes about how or when kinetochores interact with microtubule plus ends to achieve bipolar attachment, except the involvement of kinetochore proteins and the chromosomal passenger complex (Resnick et al., 2009; Radford et al., 2015). sentin mutants are viable with minimal mitotic defects, but they are female sterile. In oocytes lacking Sentin, kinetochores and microtubules precociously form robust interactions, leading to frequent attachment of both homologs to the same pole during meiosis I. Therefore, the catastrophe-promoting protein Sentin is responsible for delaying kinetochore–microtubule attachment until spindle bipolarity is fully established in oocytes.

Results and discussion

sentin mutants are viable and show minimal mitotic defects but are female sterile

To define the role of Sentin in developing flies, we generated four partial deletion mutants of sentin by remobilizing a P element inserted in the 5′ end of the sentin gene (Fig. S1 A). All alleles were viable but female sterile, showing similar defects in mature oocytes (Fig. S1 C), and we focused our analysis on two alleles (ΔB and Δ19). Western blots confirmed that full-length Sentin protein was undetectable in both alleles (Fig. S1 B), and the phenotypes were indistinguishable. Female sterility and the cytological phenotype of sentin oocytes were rescued by transgenes expressing a full-length sentin cDNA (see below). We did not observe significant defects in somatic mitosis of larval central nervous systems or in male meiosis (Fig. S1, D and E), suggesting predominantly oocyte-specific roles of Sentin.

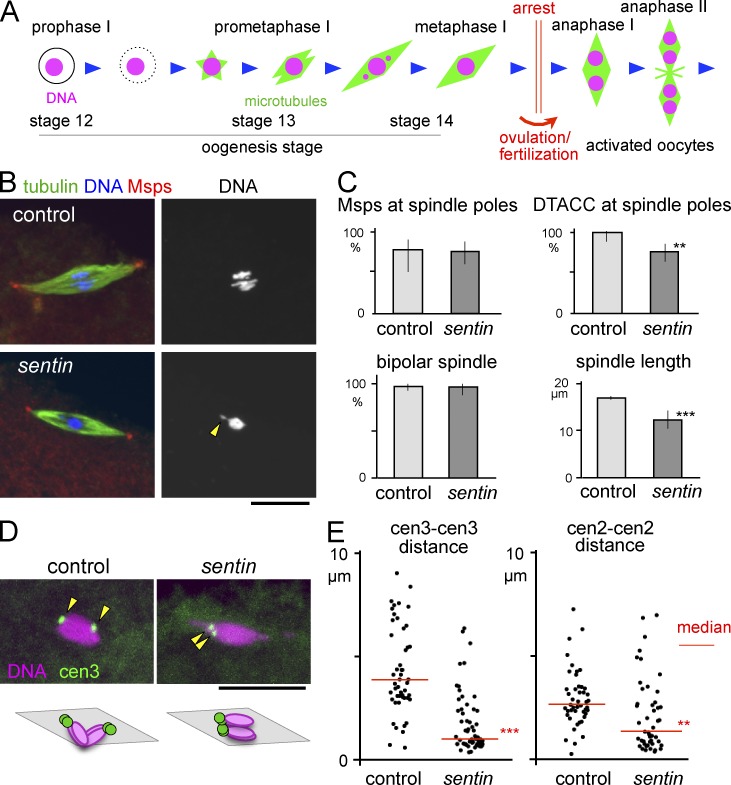

Sentin is crucial for separating homologous centromeres apart in oocytes

To identify the role of Sentin in spindle formation in oocytes, sentin-mutant oocytes were immunostained for α-tubulin and the pole protein Msps or D-TACC. The spindles were bipolar, with Msps and D-TACC accumulated at the poles in most (>75%) mature oocytes that arrest in metaphase I (Fig. 1, B and C). However, D-TACC accumulation was slightly reduced (Fig. 1 C). The spindle was shorter but denser than wild-type control (Fig. 1, B and C; and Fig. S2 A). Short spindles were observed in Sentin-depleted cultured cells, which showed altered microtubule plus-end dynamics (Goshima et al., 2007; Li et al., 2011). Chromosomes, including the achiasmatic fourth chromosomes, were more often clustered compactly at the spindle equator, sometimes (18%) with protrusions (Fig. 1 B and Fig. 2, C and D). In contrast, more stretched, individualized chromosomes were observed in control oocytes (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S2, C and D).

Figure 1.

Sentin is required to separate homologous centromeres in oocytes. (A) Meiotic progression in Drosophila oocytes. The arrowhead indicates a chromosome protrusion. (B) Immunostaining of mature oocytes. (C) Frequency of Msps and D-TACC concentrated at the spindle poles, and bipolar spindles in wild-type (control) and sentin mature oocytes (n = 13, 36, 24, 58, 95, and 66). The error bars of the spindle length indicate the SEM (n = 94 and 120). Other error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, significant differences between wild type and sentin. (D) FISH in oocytes using a dodeca-satellite probe specific to centromere 3. The arrowheads indicate centromere 3 signals. (E) The distances between homologous centromeres from FISH probed by dodeca satellite (cen 3) and AACAC satellite repeat (cen 2). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, significant differences from the medians of wild-type control. Bars, 10 µm.

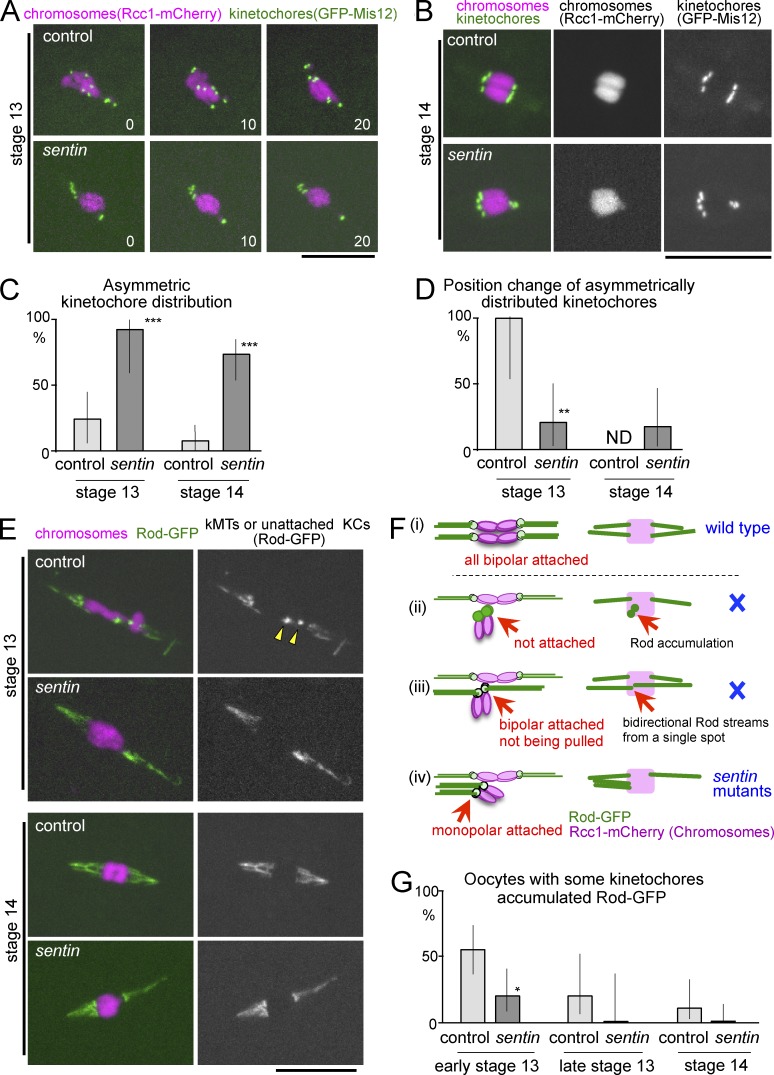

Figure 2.

Monopolar attachment of homologous kinetochores in sentin oocytes. (A) Live stage 13 oocytes expressing GFP-Mis12 and Rcc1-mCherry. (B) Stage 14 oocytes expressing GFP-Mis12 and Rcc1-mCherry. (C) The frequency of asymmetric kinetochore distributions seen by GFP-Mis12 (n = 26, 11, 31, and 29). (D) The frequencies of position change of asymmetrically distributed kinetochores within 20 min, seen by GFP-Mis12 (n = 5, 10, 0, and 12). ND, not done because of no control stage 14 oocytes with asymmetrically distributed kinetochores observable for 20 min. (E) Live mature oocytes expressing GFP-Rod and Rcc1-mCherry. Arrowheads point to accumulated Rod-GFP. kMT, kinetochore microtubule; KC, kinetochore. (F) Diagrams of various attachment modes with expected Rod-GFP localization. Only monopolar attachments can explain the unseparated homologous centromeres observed in sentin-mutant oocytes. (G) The frequency of oocytes with at least one kinetochore accumulating Rod-GFP (n = 25, 20, 10, 12, 18, and 21). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, significant differences from the control. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. Bars, 10 µm.

To determine the positions of homologous centromeres, pericentromeric satellites specific to centromere 3 were visualized by FISH. In control oocytes, two signals were located at opposite ends of the chromosome mass, representing a pair of homologous centromeres pulled toward the opposite poles but connected by chromosome arms with chiasmata (Fig. 1 D). In contrast, homologous centromeres were located closely together (<1 µm) in 45% of the sentin-mutant oocytes (Fig. 1 E). A probe specific to centromere 2 also showed similar results (Fig. 1 E). The defect was rescued by a transgene expressing a wild-type sentin cDNA from the ubiquitin promoter (below), confirming that Sentin is required for separating homologous centromeres.

Taken together, Sentin is a microtubule plus-end regulator crucial for separating homologous centromeres apart in oocytes without an essential role in bipolar spindle formation.

Unseparated homologous centromeres are stably attached to the same pole in sentin oocytes

To establish the cause of unseparated homologous centromeres in sentin mutants, chromosomes and kinetochores were first visualized in live oocytes using Rcc1-mCherry (Colombié et al., 2013) and GFP-Mis12 (Materials and methods), respectively. Live imaging preserves dorsal appendages, which allow staging of oocytes (Fig. 1 A). In control oocytes, asymmetrically distributed kinetochores were found at an earlier stage (stage 13; Fig. 2, A and C), but they were nearly eliminated by a late stage (stage 14; Fig. 2, B and C). In most (>72%) sentin-mutant oocytes, an unequal number of kinetochores was observed at each end of the chromosome mass at both stages (Fig. 2, A–C), in agreement with the centromere FISH results and immunostaining results (Fig. S2 E).

To test whether these misoriented kinetochores were corrected, we followed these oocytes for another 20 min. In all control oocytes, asymmetrically distributed kinetochores in stage 13 changed their positions (Fig. 2, A and D). In contrast, in most (80%) mutant oocytes, asymmetrically distributed kinetochores did not change their positions within the same time frame (Fig. 2, A and D). Therefore, unlike control oocytes, mispositioned kinetochores are stably maintained in the sentin-mutant oocytes.

Next, to determine whether and how kinetochores were attached to microtubules, the Rough deal (Rod) protein tagged with GFP (Basto et al., 2004) was used. Rod is part of the RZZ complex, which is continuously recruited to kinetochores and removed by dynein-dependent transport along kinetochore microtubules (Karess, 2005). Therefore, kinetochore microtubules are highlighted by Rod streams, and unattached kinetochores accumulate Rod as foci. In the wild-type control, more than half (55%) of the early stage 13 oocytes had at least one kinetochore which accumulated Rod-GFP (Fig. 2, E and G). At stage 14, no kinetochores accumulated Rod-GFP, and Rod-GFP streams were symmetrically moving toward both poles (Fig. 2 E and Video 1), indicating all homologous kinetochores have achieved bipolar attachments (Fig. 2 F, i).

Unseparated homologous centromeres observed in sentin-mutant oocytes can be caused by three possibilities, which can be distinguished by the Rod-GFP pattern. Homologous kinetochores either fail to attach microtubules (Fig. 2 F, ii), attach microtubules from opposite poles but fail to be pulled (Fig. 2 F, iii), or attach microtubules from the same pole (Fig. 2 F, iv). At early stage 13, only a small proportion (20%) of sentin-mutant oocytes have Rod-GFP accumulated at kinetochores (Fig. 2, E and G), suggesting microtubules may precociously attach to kinetochores. At stage 14, sentin-mutant oocytes displayed robust Rod-GFP streams, which are often asymmetrical (63% vs. 7% in the control), without accumulation at kinetochores (Fig. 2 E and Video 2). This indicates that kinetochores must be robustly attached to microtubules (excluding ii in Fig. 2 F). We did not see Rod-GFP streams emerging from a single point (or two closely located points) in both directions. This excludes the possibility (Fig. 2 F, iii) that unseparated homologous kinetochores are connected to microtubules from the opposite poles. The Rod-GFP pattern in sentin-mutant oocytes is only consistent with attachment of homologous kinetochores to microtubules from the same pole (“monopolar” or “syntelic” attachment; Fig. 2 F, iv).

In agreement with observations from GFP-Mis12, detachment or direction changes of Rod-GFP streams were rarely observed in stage 14 mutant oocytes, even when they were distributed asymmetrically (one event in a total of 150 min of observation). This demonstrates that kinetochore–microtubule attachments are stable in sentin-mutant oocytes, regardless of whether they are attached in a monopolar or bipolar fashion.

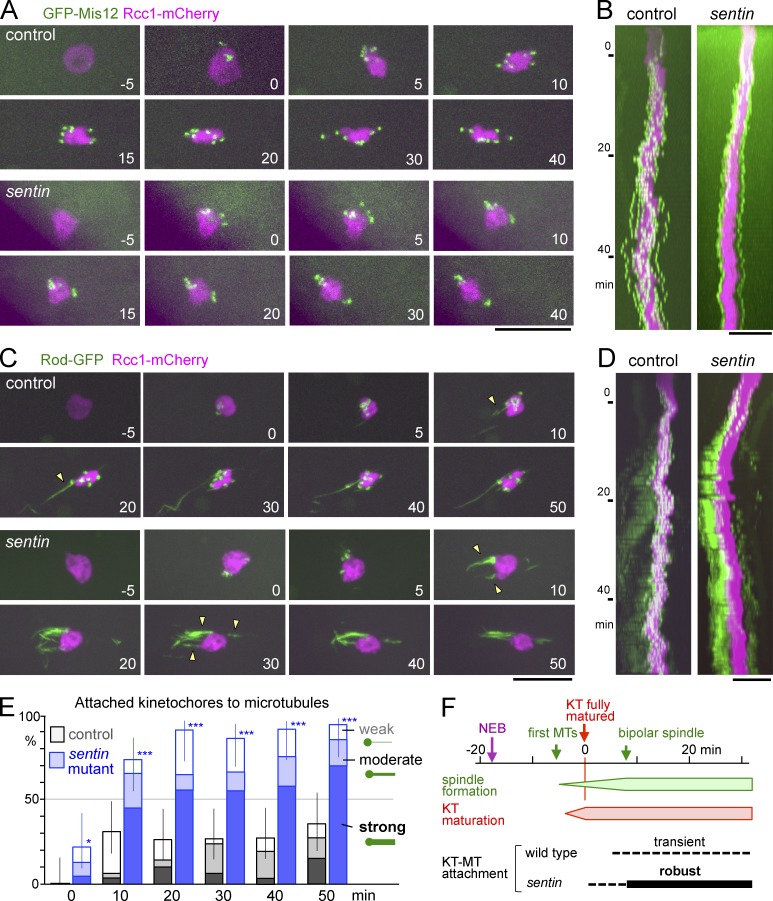

Precocious stable kinetochore–microtubule attachments in the sentin oocytes

To conclusively define when and how monopolar attachments are established, we followed kinetochore positions from the beginning of spindle formation. In control oocytes, after nuclear envelope breakdown, spindle microtubules start assembling at ∼10 min, and spindle bipolarity is established after ∼30 min (Colombié et al., 2008). The start of accumulation of kinetochore proteins (seen by GFP-Mis12 and Rod-GFP) roughly coincides with the start of spindle microtubule assembly (Fig. 3 F). In control oocytes expressing GFP-Mis12, soon after full accumulation of kinetochore proteins (kinetochore maturation), kinetochores dynamically moved from one end of the chromosome mass to the other end, and this dynamic movement persisted even 1 h after kinetochore maturation (Fig. 3, A and B; and Video 3). This persistent dynamic movement in early oocytes has not previously been recognized because kinetochores had not been visualized in live oocytes before, and individual chromosomes could not be resolved. It may be related to previously reported phenomena, such as uncongressed chromosomes (proposed as “prometaphase” figures; Gilliland et al., 2009) or oscillatory movement of achiasmatic chromosomes (Hughes et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Sentin suppresses precocious stable kinetochore–microtubule attachments. (A) Time-lapse images of oocytes expressing GFP-Mis12 and Rcc1-mCherry. The numbers are in minutes from full recruitment of Mis12. (B) Kymographs of the same oocytes with the long axis of the spindle against time (Y-axis). (C) Time-lapse images of oocytes expressing Rod-GFP and Rcc1-mCherry. The numbers are in minutes from full recruitment of Rod. Arrowheads indicate Rod-GFP streams. (D) Kymographs of the same oocytes. (E) The frequency of weakly (open bars), moderately (half-filled), and strongly (filled) attached kinetochores judged by Rod-GFP (Materials and methods). For each genotype, a total of 20–32 kinetochores in five oocytes were followed. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, significant differences from the control. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the proportion of attached kinetochores. (F) The approximate timing of cytological events in oocytes. KT, kinetochore; MT, microtubule; NEB, nuclear envelope breakdown; Time 0, time when full recruitment of kinetochore proteins, Mis12 and Rod, has occurred. Bars, 10 µm.

In sentin oocytes, the behavior of kinetochores during spindle formation was dramatically different (Fig. 3, A and B; and Video 4). In all of the mutant oocytes, kinetochores were much less mobile. Kinetochores usually separated into two (often unequal) groups and migrated to ends of the chromosome mass soon after kinetochore maturation. After they reached the ends, most of the kinetochores rarely changed their positions, even when kinetochores were asymmetrically distributed.

To define the timing of kinetochore-microtubule attachments, oocytes expressing Rod-GFP were followed from the beginning of spindle formation (Fig. 3, C and D). In control oocytes, Rod-GFP first accumulated at kinetochores after nuclear envelope breakdown. Then some kinetochores showed association with a weak stream (Fig. 3 C, arrowheads; and Video 5), whereas Rod-GFP still showed clear accumulation at most kinetochores, indicating weak attachments of microtubules to the kinetochores. Rod-GFP accumulation at most kinetochores persisted well after bipolar spindle formation (Fig. 3, C–E). A delay in end-on kinetochore attachments to microtubules has been reported in mouse oocytes, but it has not been previously described in Drosophila oocytes.

Remarkably, in sentin-mutant oocytes, soon after the Rod-GFP accumulated, strong and persistent Rod-GFP streams appeared (Fig. 3, D and E; and Video 6). The timing of the appearance of robust Rod-GFP streams was earlier, and the intensity and persistence of the streams were much higher than in control oocytes; however, the timings of establishing the spindle bipolarity were comparable (Fig. S2 B). This demonstrated that robust kinetochore-microtubule attachments were formed precociously in the sentin mutant.

To compare microtubule dynamics, we performed FRAP of GFP-tubulin in control and sentin-mutant oocytes. We observed similar recovery at stages 13 and 14 in the control, whereas sentin mutant showed marginally slower recovery at stage 13 compared with stage 14 (Fig. S3). It remains to be seen whether this difference, if any, represents a change in microtubule dynamics.

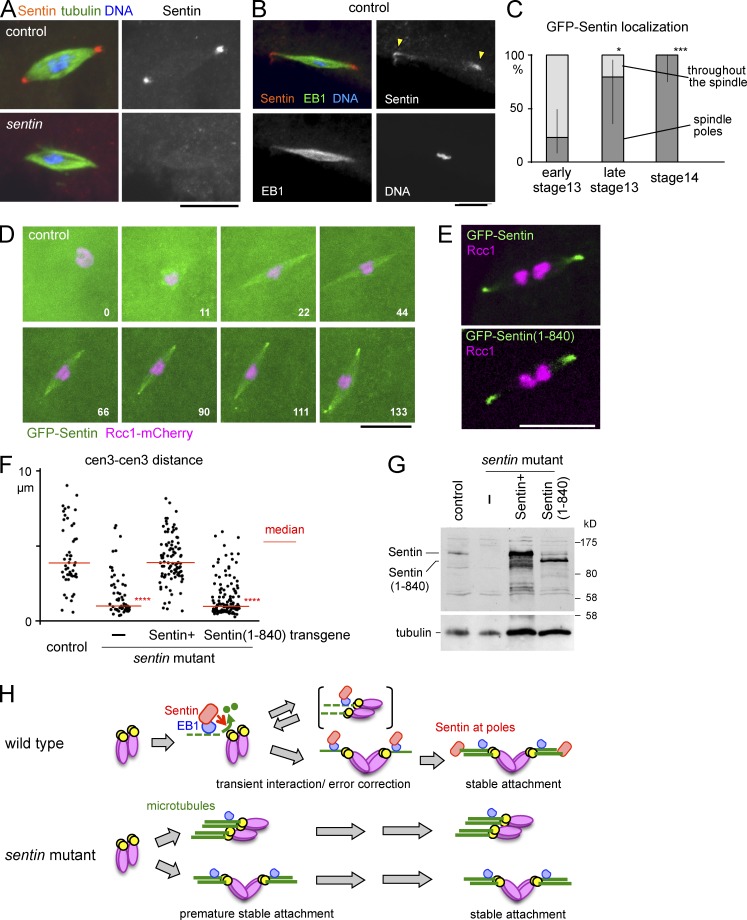

Sentin is enriched at acentrosomal spindle poles in oocytes after establishment of the bipolar spindle

In S2 cells, Sentin is recruited to microtubule plus ends by EB1 through direct physical interaction. During mitosis, EB1 and Sentin colocalize all over the spindle as moving comets. To determine the localization of Sentin on meiotic spindles in oocytes, mature stage 14 control wild-type oocytes were immunostained with Sentin and α-tubulin antibodies. Interestingly Sentin was accumulated at poles of meiotic spindles in most (68%) oocytes (Fig. 4 A). The signal was lost in the sentin mutant (Fig. 4 A), confirming this represents endogenous localization of the Sentin protein. Costaining of Sentin and EB1 highlighted uniform localization of EB1 all over meiotic spindles in all oocytes, in clear contrast with the mostly pole accumulation of Sentin (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Sentin function, not pole localization, depends on EB1 interaction. (A and B) Immunostaining of mature oocytes. (C) Localization of GFP-Sentin at different stages of oocytes (n = 13, 5, and 12). Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01, significant difference from early stage 13. (D) Time-lapse images of oocytes expressing GFP-Sentin and Rcc1-mCherry. The numbers indicate minutes from nuclear envelope breakdown. (E) Live wild-type control oocyte expressing GFP-tagged full-length Sentin and Sentin(1–840) lacking the EB1-interacting domain. (F) The distances between homologous centromeres (cen 3) in mature oocytes from wild-type control and sentin mutants without a transgene (–) and with transgenes expressing full-length Sentin and Sentin(1–840). ****, P < 0.001, significant difference from the control. (G) Immunoblots of adult females from strains shown in F probed with antibodies against Sentin (top) and α-tubulin (bottom). (H) A model of Sentin action. Bars, 10 µm.

To follow Sentin localization through different stages, transgenic flies expressing GFP-tagged Sentin under the control of an ubiquitin promoter were generated; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that it may not accurately reflect the endogenous localization. GFP-Sentin localized all over the spindle in most (23%) oocytes at early stage 13, and by stage 14 it accumulated at the spindle poles in all oocytes (Fig. 4 C). To confirm this observation, we observed the oocytes expressing GFP-Sentin from nuclear envelope breakdown. GFP-Sentin localized all over the spindle at early stages when spindle bipolarity has not been established. In the same oocytes, GFP-Sentin has subsequently accumulated only well after spindle bipolarity is established (Fig. 4 D). Early Sentin localization all over the spindle may contribute to the instability of microtubule-kinetochore attachments, whereas late sequestration of Sentin at the poles may contribute to more stable attachments after establishment of a bipolar spindle.

To understand relationships between the localization, function, and EB1 interaction, we first expressed GFP-tagged full-length Sentin and Sentin(1–840) lacking the EB1-interaction domain (Li et al., 2011) in control oocytes. In both cases, they accumulated to the spindle poles in mature oocytes (Fig. 4 E), indicating that the EB1 interaction is not required for Sentin pole localization. Next, to test whether EB1 interaction is required for the Sentin function, Sentin(1–840) lacking the EB1-interaction domain was expressed in the sentin mutant. A full-length Sentin rescued the sentin defect, whereas Sentin(1–840) under the same promoter failed to rescue it (Fig. 4 F). Immunoblotting confirmed that proteins with the predicted sizes were expressed (Fig. 4 G). These results showed that the EB1 interaction is essential for Sentin function, but not its pole localization, supporting a hypothesis that Sentin functions at microtubule ends, and late localization to the spindle pole may help to stabilize kinetochore-microtubule attachments.

Sentin-EB1 prevents precocious kinetochore attachments to facilitate bipolar attachments of bivalent chromosomes in oocytes

In this study, we showed that Drosophila oocytes delay robust end-on attachments of microtubules to kinetochores. Similar delay is also observed in mouse oocytes (Brunet et al., 1999; Kitajima et al., 2011), demonstrating that this is a widely conserved phenomenon in oocytes. This long delay is oocyte specific and is not seen in mitotic cells. Because establishment of spindle bipolarity takes much longer in oocytes because of a lack of centrosomes, this oocyte-specific long delay is likely to help kinetochores not to form robust microtubule attachments before a bipolar spindle is fully established. We found that the EB1-interacting protein Sentin is responsible for preventing microtubules from precociously forming robust attachments to kinetochores (Fig. 4 H).

We have previously shown in vitro that Sentin, through physical interaction with EB1, directly increases growth and catastrophe rates of microtubule plus ends and also recruits Msps, the XMAP215 orthologue, to increase the microtubule growth and rescue rates (Li et al., 2012). In this study, we showed that the role of Sentin to destabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachments requires the interaction with EB1. A female sterile msps mutant does not have a sentin-like defect (Cullen and Ohkura, 2001), suggesting the catastrophe-promoting activity of Sentin-EB1 is key to destabilizing the attachments.

Sentin-mutant oocytes have a high frequency of homologous centromeres attached to the same pole even at later stages. Live imaging showed that incorrect attachments remain stable and uncorrected. Observation in activated oocytes showed chromosome missegregation in four out of five anaphase I, which explains most of the infertility. We are not sure at the moment whether Sentin specifically destabilizes incorrect attachments or indiscriminately destabilizes all attachments. In mouse oocytes, persistent Aurora B/C at kinetochores destabilizes both correct and incorrect attachments, and later recruitment of the phosphatase PP2A-B56 to kinetochores stabilizes the attachments (Yoshida et al., 2015). Also, in Drosophila oocytes, Aurora B activity is required for normal biorientation of homologous centromeres (Resnick et al., 2009), but it did not appear to be compromised in the sentin mutant (Fig. S2, F–H). We found in Drosophila oocytes that Sentin accumulates at spindle poles well after establishment of spindle bipolarity independently of its EB1 interaction. This late pole localization, which sequesters the catastrophe factor away from kinetochores, may be one of the mechanisms to stabilize kinetochore–microtubule attachments after the establishment of spindle bipolarity.

Taken together, Sentin with microtubule catastrophe-promoting activity facilitates bipolar attachment of homologous chromosomes in oocytes by destabilizing the kinetochore–microtubule attachments during acentrosomal spindle formation. Previously in mouse oocytes, phosphoregulation of kinetochore proteins has shown to be responsible for the delay in forming stable kinetochore–microtubule attachments (Yoshida et al., 2015). Our finding in Drosophila oocytes demonstrates that regulation of microtubule plus ends is a novel mechanism to delay stable attachments. It is possible that Drosophila and mouse use different mechanisms to achieve the same goal, but it also possible that both organisms use these two mechanisms in parallel with different contributions.

Materials and methods

Fly genetics

Genes, mutations, and chromosome aberrations are described in FlyBase (Drysdale, 2008) and Lindsley and Zimm (1992). Standard fly techniques were used (Ashburner et al., 2005). For generation of sentin mutants, chromosomes in progeny of jump-starter males carrying both Δ2-3 and the P element EY00443 were selected for a loss of w+. The regions of deletions were determined by PCR and sequencing from the mutant genomic DNA. For rescue of sentin mutants by a transgene, a single copy of a transgene was introduced in flies carrying sentinΔB mutation over a deficiency, and at least two independent insertions were tested. In most cases, the phenotype of sentin mutants were observed over a deficiency uncovering sentin (Df(3R)ED4515 or Df(3R)BSC737), and a homozygous wild-type allele or a wild-type allele over a sentin mutation with matched transgene combinations were used as a wild-type control.

The frequency of sex chromosome nondisjunction in males was measured according to Meireles et al. (2009). For live imaging, GFP-Mis12 and Rcc1-mCherry under UASp was driven by nos-GAL4 (MVD1), and Rod-GFP is controlled under its own promoter (a gift from R. Karess, Institut Jacques Monod, Paris, France; Basto et al., 2004). All transgenes and sentin mutations are located on the third chromosomes and recombined together on the same chromosome when necessary. These recombined chromosomes were observed over a sentin deficiency (sentin mutant) or wild-type chromosome (control). In some cases, an equivalent recombinant chromosome without a sentin mutation over wild-type chromosome was used as a control.

Molecular work

Standard molecular techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989) were used. For sentin transgenes, the coding region of the full-length sentin or part of sentin corresponding 1–840 residues were cloned into a Gateway vector modified from pWR-Ubq (generated by N. Brown’s laboratory, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, UK). GFP-Mis12 under the UASp promoter was generated using pPGW Gateway vector (generated by T. Murphy's laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC). Transgenic flies were generated by Genetic Service Inc. using P element–mediated transformation. Protein samples for Western blots were prepared by homogenizing whole adult females after heat treatment at 98°C.

Antibodies used for Western blotting were mouse anti–α-tubulin (DM1A; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Sentin (Li et al., 2011), and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and detected by ECL (GE Healthcare). To generate the rat anti-Sentin antibody, the insoluble fraction of BL21/pLysS expressing MBP-Sentin was run on SDS gel, and MBP-Sentin was extracted from the gel and used to immunize two rats by the Scottish Blood Transfusion Service.

Cytological study

For live imaging, ovaries were dissected in halocarbon oil (700; Halocarbon) from adult females matured for 4–7 d at 18°C. The morphology of dorsal appendages was used to determine the stage of oocytes. Oocytes were observed at room temperature under a microscope (Axiovert; Carl Zeiss) attached to a spinning disk confocal head (Yokogawa) controlled by Volocity (PerkinElmer). Z-slices with a 0.8-µm interval were captured every half minute or minute and are presented after maximum intensity projection onto the XY plane. To generate kymographs using Volocity, a 3D image of each time point was first projected onto the XY plane, and this 2D image was then projected onto the long axis of the spindle using maximum intensity projection. This compressed 1D image was aligned against time. Fisher exact test and t test were used for categorical and parametrical data, respectively.

The strength of kinetochore attachment to microtubules was classified into four levels using Rod-GFP patterns by the following criteria: (1) no visible Rod-GFP stream with clear accumulation on the kinetochore was classified as no attachment, (2) a faint stream with clear accumulation on the kinetochore was classified as weak attachment, (3) a clear stream with significantly less intensity than the signal at the kinetochore was classified as moderate attachment, and (4) a clear stream as strong as the kinetochore signal was classified as strong attachment.

FRAP was performed and analyzed as previously described (Colombié et al., 2013) with the following modifications. The rectangular box (12 × 8.5 µm) covering a half-spindle was bleached using 25 iterations of the 488-nm laser at 100% power, and three Z-slices were taken at 1-µm intervals every 5 s. After maximum intensity projection, the total signal intensity of a 1- × 1-µm square within the bleached area on the spindle was measured. The signal intensity was normalized so that the prebleached value was one and the value at the first time point after bleaching was zero.

Mitosis was analyzed after the aceto-orcein staining of squashed larval central nervous systems as described in Cullen et al. (1999). Postmeiotic figures in testes were analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy after gentle squashing as described in Bonaccorsi et al. (2000). Oocytes were immunostained after methanol fixation as described in Cullen and Ohkura (2001). FISH of oocytes was performed according to Meireles et al. (2009) and Loh et al. (2012). Immunostaining and FISH in oocytes were performed after the maturation of young adults for 3–5 d at 25°C or for 4–7 d at 18°C. Under these conditions, most fully grown oocytes were arrested at stage 14 and generally considered as mature stage 14 oocytes for our immunostaining because there are no accurate staging methods because of a loss of dorsal appendages. Immunostained oocytes were examined using a PlanApochromat objective lens (63×, 1.4 NA) on LSM5.10 Exciter (Carl Zeiss) unless stated otherwise, and images were presented after maximum intensity projection onto the XY plane. To take higher-resolution images (Fig. S2 E), mature oocytes were fixed in formaldehyde/heptane and stained with Hoechst 33342, and images were taken on an SP5 (Leica) with 63×, 1.4 NA lens (pixel size of 53.4 nm) as previously described (Radford et al., 2012). The Ndc80 antibody was a gift of T. Maresca (University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA). Activated oocytes were collected every 10 min and fixed in methanol for immunostaining to observe anaphase I and later stages. Chromosome missegregation in meiosis I was estimated by unequal numbers of segregated chromosomes. Antibodies used were mouse anti–α-tubulin (1:250; DM1A; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-EB1 (1:500; HN285; Elliott et al., 2005), rabbit anti-Sentin (1:1,000; Li et al., 2011), rabbit anti-Msps (1:100; HN264; Cullen and Ohkura, 2001), rabbit anti–D-TACC-CTD (1:1,000; Loh et al., 2012), and secondary antibodies conjugated with Cy3 or Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescent dyes (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories or Molecular Probes). DNA was stained with 0.4 µg/ml DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). For a pericentromeric satellite specific to the second chromosome, a synthetic oligonucleotide (aacac)6 was used as a probe.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows generation of sentin mutants and their phenotypes. Fig. S2 shows detailed phenotypes of sentin-mutant oocytes, including evidence for unaltered Aurora B activity and localization. Fig. S3 presents FRAP analysis of GFP–α-tubulin in control and sentin-mutant oocytes. The videos show wild-type and sentin stage 14 oocyte expressing Rod-GFP Rcc1-mCherry (Videos 1 and 2), wild-type and sentin stage 13 oocyte expressing GFP-Mis12 Rcc1-mCherry (Videos 3 and 4), and wild-type and sentin stage 13 oocyte expressing Rod-GFP Rcc1-mCherry (Videos 5 and 6). Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201507006/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Karess, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) and Resource Center (NIH 2P40OD010949-10A1), and the Drosophila gene disruption project for providing reagents and fly stocks. We thank A. Satoh for helping with mutant generation, S. Beard and H. Gray for generating antibodies, T. Maresca for reagents, R. Beaven for critical reading of the manuscript, and members of McKim and Ohkura Laboratories for discussion.

The works in Goshima, Ohkura, and McKim Laboratories are supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15H01317; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan), the Wellcome Trust (081849, 086574, 092076, 098030, and 099827), and the National Institutes of Health (GM10955), respectively.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- Msps

- microtubule polymerase Mini spindles

- Rod

- Rough deal

References

- Ashburner M., Golic K.G., and Hawley R.S.. 2005. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 1409 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Scaerou F., Mische S., Wojcik E., Lefebvre C., Gomes R., Hays T., and Karess R.. 2004. In vivo dynamics of the rough deal checkpoint protein during Drosophila mitosis. Curr. Biol. 14:56–61. 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccorsi S., Giansanti M.G., Cenci G., and Gatti M.. 2000. Cytological analysis of spermatocyte growth and male meiosis in Drosophila melanogaster. In Drosophila Protocols. Sullivan W., Ashburner M., and Scott Hawley R., editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet S., Maria A.S., Guillaud P., Dujardin D., Kubiak J.Z., and Maro B.. 1999. Kinetochore fibers are not involved in the formation of the first meiotic spindle in mouse oocytes, but control the exit from the first meiotic M phase. J. Cell Biol. 146:1–12. 10.1083/jcb.146.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M. 2014. The kinetochore. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6:a015826 10.1101/cshperspect.a015826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombié N., Cullen C.F., Brittle A.L., Jang J.K., Earnshaw W.C., Carmena M., McKim K., and Ohkura H.. 2008. Dual roles of Incenp crucial to the assembly of the acentrosomal metaphase spindle in female meiosis. Development. 135:3239–3246. 10.1242/dev.022624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombié N., Głuszek A.A., Meireles A.M., and Ohkura H.. 2013. Meiosis-specific stable binding of augmin to acentrosomal spindle poles promotes biased microtubule assembly in oocytes. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003562 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen C.F., and Ohkura H.. 2001. Msps protein is localized to acentrosomal poles to ensure bipolarity of Drosophila meiotic spindles. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:637–642. 10.1038/35083025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen C.F., Deák P., Glover D.M., and Ohkura H.. 1999. mini spindles: A gene encoding a conserved microtubule-associated protein required for the integrity of the mitotic spindle in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 146:1005–1018. 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydenko O., Schultz R.M., and Lampson M.A.. 2013. Increased CDK1 activity determines the timing of kinetochore-microtubule attachments in meiosis I. J. Cell Biol. 202:221–229. 10.1083/jcb.201303019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale R., FlyBase Consortium 2008. FlyBase: a database for the Drosophila research community. Methods Mol. Biol. 420:45–59. 10.1007/978-1-59745-583-1_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S.L., Cullen C.F., Wrobel N., Kernan M.J., and Ohkura H.. 2005. EB1 is essential during Drosophila development and plays a crucial role in the integrity of chordotonal mechanosensory organs. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:891–901. 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland W.D., Hughes S.F., Vietti D.R., and Hawley R.S.. 2009. Congression of achiasmate chromosomes to the metaphase plate in Drosophila melanogaster oocytes. Dev. Biol. 325:122–128. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G., Wollman R., Goodwin S.S., Zhang N., Scholey J.M., Vale R.D., and Stuurman N.. 2007. Genes required for mitotic spindle assembly in Drosophila S2 cells. Science. 316:417–421. 10.1126/science.1141314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S.E., Gilliland W.D., Cotitta J.L., Takeo S., Collins K.A., and Hawley R.S.. 2009. Heterochromatic threads connect oscillating chromosomes during prometaphase I in Drosophila oocytes. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000348 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karess R. 2005. Rod-Zw10-Zwilch: a key player in the spindle checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 15:386–392. 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T.S., Ohsugi M., and Ellenberg J.. 2011. Complete kinetochore tracking reveals error-prone homologous chromosome biorientation in mammalian oocytes. Cell. 146:568–581. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Miki T., Watanabe T., Kakeno M., Sugiyama I., Kaibuchi K., and Goshima G.. 2011. EB1 promotes microtubule dynamics by recruiting Sentin in Drosophila cells. J. Cell Biol. 193:973–983. 10.1083/jcb.201101108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Moriwaki T., Tani T., Watanabe T., Kaibuchi K., and Goshima G.. 2012. Reconstitution of dynamic microtubules with Drosophila XMAP215, EB1, and Sentin. J. Cell Biol. 199:849–862. 10.1083/jcb.201206101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley D.L., and Zimm G.G.. 1992. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press, New York. 1133 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Loh B.J., Cullen C.F., Vogt N., and Ohkura H.. 2012. The conserved kinase SRPK regulates karyosome formation and spindle microtubule assembly in Drosophila oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 125:4457–4462. 10.1242/jcs.107979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meireles A.M., Fisher K.H., Colombié N., Wakefield J.G., and Ohkura H.. 2009. Wac: a new Augmin subunit required for chromosome alignment but not for acentrosomal microtubule assembly in female meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 184:777–784. 10.1083/jcb.200811102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S.J., Harrison A.M., and McKim K.S.. 2012. Microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin KLP10A restricts the length of the acentrosomal meiotic spindle in Drosophila females. Genetics. 192:431–440. 10.1534/genetics.112.143503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S.J., Hoang T.L., Głuszek A.A., Ohkura H., and McKim K.S.. 2015. Lateral and end-on kinetochore attachments are coordinated to achieve bi-orientation in Drosophila oocytes. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005605 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick T.D., Dej K.J., Xiang Y., Hawley R.S., Ahn C., and Orr-Weaver T.L.. 2009. Mutations in the chromosomal passenger complex and the condensin complex differentially affect synaptonemal complex disassembly and metaphase I configuration in Drosophila female meiosis. Genetics. 181:875–887. 10.1534/genetics.108.097741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., and Maniatis T.. 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 1751 pp. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart B., Manatschal C., Grigoriev I., Olieric V., Gouveia S.M., Bjelic S., Demmers J., Vorobjev I., Hoogenraad C.C., Steinmetz M.O., and Akhmanova A.. 2011. SLAIN2 links microtubule plus end-tracking proteins and controls microtubule growth in interphase. J. Cell Biol. 193:1083–1099. 10.1083/jcb.201012179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S., Kaido M., and Kitajima T.S.. 2015. Inherent instability of correct kinetochore-microtubule attachments during meiosis I in oocytes. Dev. Cell. 33:589–602. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.