Abstract

Background

Parathyroidectomy is the only curative treatment for tertiary hyperparathyroidism (3HPT). With the introduction of calcimimetics (cinacalcet), parathyroidectomy can sometimes be delayed or avoided. The purpose of this study was to determine the current incidence of utilization of parathyroidectomy in patients with post-transplant 3HPT with the advent of cinacalcet.

Method

We evaluated renal transplant patients between 1/1/2004-6/30/2012 with a minimum of 24 months follow-up who had persistent allograft function. Patients with an increased serum level of parathyroid hormone (PTH) one year after successful renal transplantation with normocalcemia or hypercalcemia were defined as having 3HPT. A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to determine factors associated with undergoing parathyroidectomy.

Results

We identified 618 patients with 3HPT, only 41 (6.6%) of whom underwent parathyroidectomy. Patients with higher levels of serum calcium (p<0.001) and PTH (p=0.002) post-transplant were more likely to be referred for parathyroidectomy. Importantly, those who underwent parathyroidectomy had serum calcium and PTH values distributed more closely to the normal range on most recent follow-up. Parathyroidectomy was not associated with rejection (p=0.400) or with worsened allograft function (p=0.163).

Conclusion

Parathyroidectomy appears to be underutilized in patients with 3HPT at our institution. Parathyroidectomy is associated with high cure rates, improved serum calcium and PTH levels, and is not associated with rejection.

Introduction

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism (3HPT) usually occurs after a successful kidney transplant fails to normalize the production of parathyroid hormone (PTH). Persistently increased serum levels of PTH occur in up to 30% of patients after renal transplantation.1 Parathyroidectomy (PTX) is currently the only curative treatment. Indications for PTX in patients with 3HPT include severe hypercalcemia, persistent hypercalcemia more than three months to one year after transplantation, decreased bone mineral density, or symptoms of hyperparathyroidism, including pruritus, nephrocalcinosis, and pathologic bone fracture.2, 3 The diagnosis of 3HPT is controversial, and has been defined classically by a post-transplant increase in serum PTH with corresponding hypercalcemia. However, as we learn more about the underlying pathophysiology of post-transplant parathyroid function, many patients after successful renal transplantation have increased serum PTH with either a normal or increased serum calcium concentration. Additionally, when left untreated, increased levels of PTH even with normocalcemia have adverse effects on bone health and may worsen osteopenia and fracture rates.4

Recently, calcimimetics, such as cinacalcet, have received attention with respect to treating 3HPT in the hope that PTX can be delayed or even avoided. Several single-center, prospective studies have treated a small number of renal transplant patients with persistent post-transplant hyperparathyroidism with cinacalcet and have reported promising results with the normalization of calcium.5,6 These studies, however, were of short duration and did not examine the effect of cinacalcet on bone markers. Therefore, 3HPT is not an approved indication currently for patients to receive cinacalcet.7 Cinacalcet is being utilized increasingly in the 3HPT population, however, this does not seem to affect rates of cure or recurrence at PTX.8

The purpose of our study was to determine the current use of PTX in patients with 3HPT with the advent of cinacalcet. We also sought to identify patient factors predictive of undergoing PTX. We then examined specific outcomes of PTX after successful renal transplantation on long-term allograft function.

Methods

At the University of Wisconsin, the Division of Transplant Surgery maintains a prospective database of all patients who have undergone transplantation at the institution since 1994. We examined patients who underwent solitary renal transplantation between January 1, 2004 and June 30, 2012. Patients with a minimum of 24 months of follow-up and a functioning allograft were included in the analysis. We identified patients with 3HPT and collected corresponding serum values of calcium, PTH, albumin, vitamin D, and creatinine at two distinct time points for homogeneity. We then excluded secondary reasons for an increased serum PTH, such as graft failure and low Vitamin D. Thereafter, we determined what treatment, if any, 3HPT patients were receiving and trended these treatment patterns by year of transplantation. We then examined how patients with 3HPT and hypercalcemia were being treated. Using patient variables and collected laboratory data, we also sought to determine factors associated with undergoing PTX. The 3HPT patients were then cross referenced with a prospectively kept PTX database to determine the incidence and outcomes of those undergoing PTX, focusing on serum calcium and PTH at most recent follow-up. Lastly, we evaluated the relationship of PTX on long-term renal allograft survival.

Statistical analysis

Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were compared between those who did and did not undergo PTX. Pearson's Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests were used, as appropriate, for categorical variables, and Student's t-test was used for continuous variables to compare these two groups. From known pre-operative patient variables, a multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to determine factors associated with undergoing PTX. To evaluate the most recently available laboratory values, dot plots were generated in order to determine the distribution of these data points with respect to the normal range. In addition, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc analysis was employed to compare recent follow-up laboratory profiles of patients according to if they underwent PTX, treatment with cinacalcet alone, or no treatment. Lastly, we used Kaplan-Meier analysis to compare overall renal allograft survival between those who did and did not undergo PTX. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.)

Results

Data collection

A total of 777 of 2,039 solitary renal transplant patients were found to have increased serum PTH levels at 9-12 months from transplantation, defined as PTH > 72 pg/mL, the upper limit of normal in our laboratory system. As PTH is not checked routinely prior to transplantation, we examined only post-transplant labs, because they are obtained at more frequent and regular intervals. In each of these patients, we collected all available corresponding serum levels of creatinine, albumin, calcium, PTH, and vitamin D at two time points: the first at 9-12 months after the date of transplantation, and the second at most recent follow up. Using the serum creatinine level, each patient then had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) calculated via the Cockcroft-Gault equation. According to the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative,9 a severe decrease in renal function occurs when GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2. Exclusion of patients with GFR <30 in our study is in accordance with previously published PTH targets for patients with chronic kidney disease.10 This approach excluded 92 patients from our analysis. We also excluded an additional 67 patients with low vitamin D levels, defined as a total vitamin D level < 30 international units (IU), the lower limit of normal in our laboratory. This approach left 618 patients who met our inclusion criteria, who were then cross-referenced with our PTX database to determine those who underwent parathyroid surgery. All patients who had PTX prior to their transplantation date were excluded in this analysis.

Treatment of 3HPT

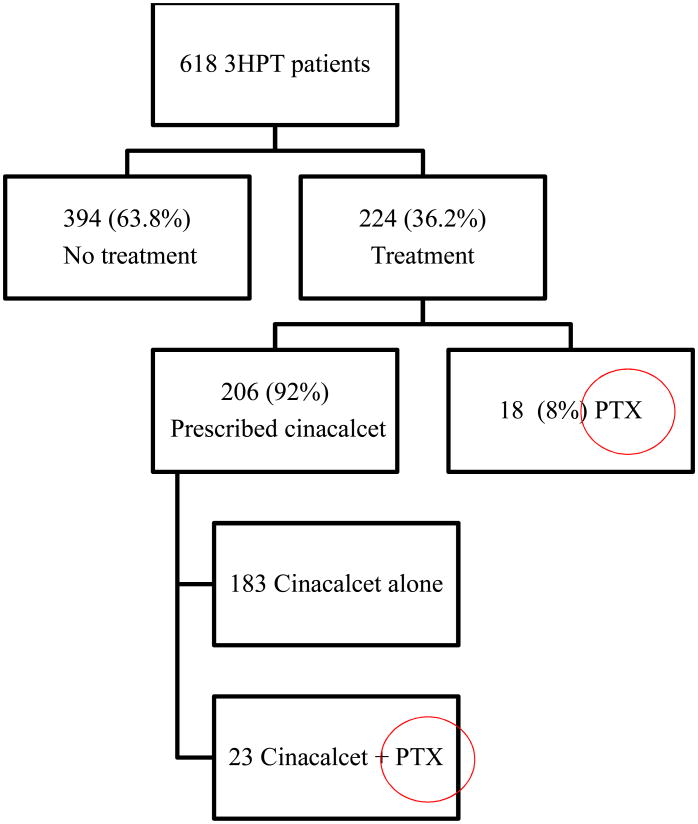

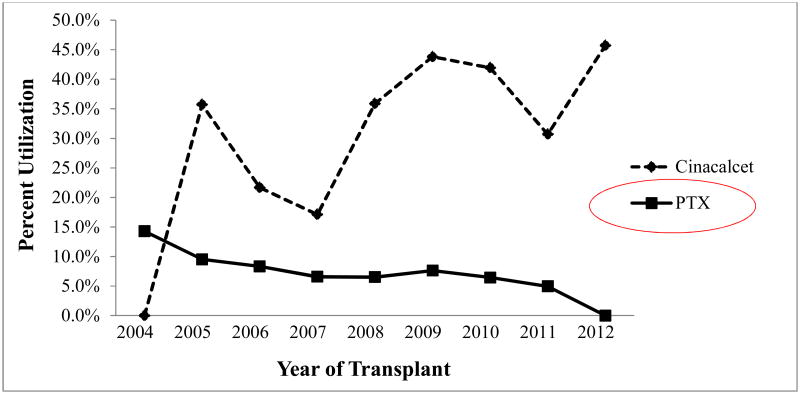

Treatment in our 618 patient cohort with 3HPT included PTX, a prescription for cinacalcet, or both. 394 (63.8%) of the patients with 3HPT did not undergo any treatment. Of the 224 (36.2%) who did get treated, the majority (206, 92%) were prescribed cinacalcet. Of those prescribed cinacalcet, 183 were given cinacalcet alone, while 23 were given cinacalcet and ultimately underwent PTX, and only 18 underwent PTX alone. (See Figure 1) Therefore, 6.6% of patients with 3HPT underwent PTX. Cinacalcet was first approved for use by the FDA in 2004, and since then, annual treatment trends in our contemporary 3HPT cohort of patients revealed that cinacalcet was being utilized increasingly, while the trend for PTX is declining. (See Figure 2)

Figure 1. Treatment categorization for patients with 3HPT after renal transplantation.

3HPT = tertiary hyperparathyroidism, PTX = parathyroid surgery

Figure 2. Annuals treatment trends for patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism by year of transplantation.

PTX = parathyroid surgery

Treatment of hypercalcemic 3HPT

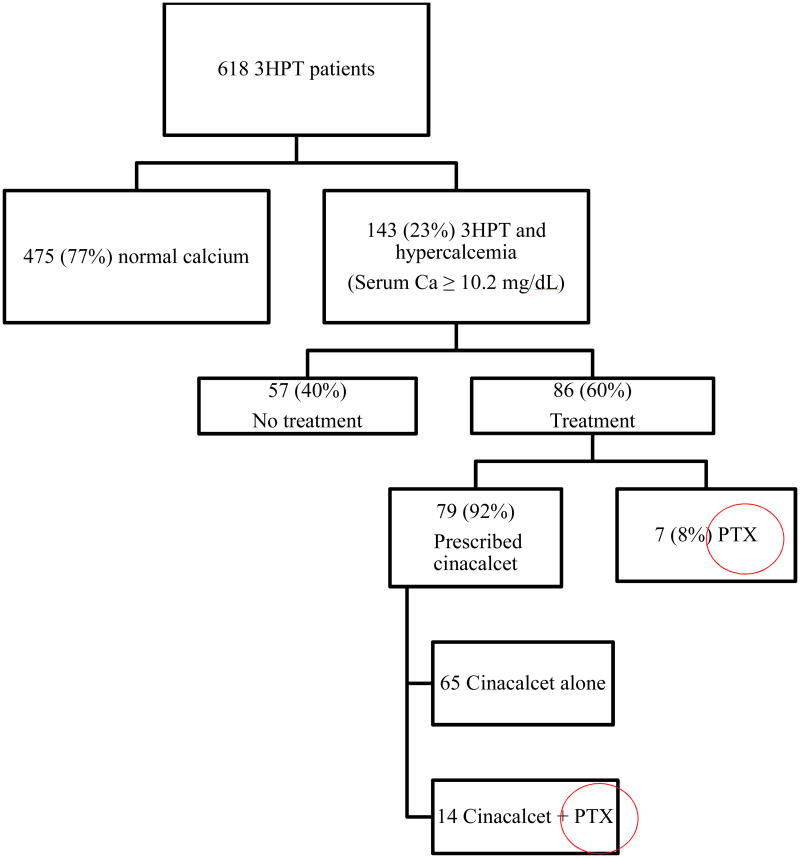

We also performed an analysis on treatment choices in our 3HPT cohort with hypercalcemia, defined as an albumin-adjusted calcium of ≥ 10.2mg/dL, the upper limit of normal in our laboratory system. A total of 143 (23%) patients in our cohort met these inclusion criteria. Among this group, 57 patients (40%) underwent no treatment. Of the 86 patients (60%) treated, cinacalcet was again the most popular modality, being employed in 79 (92%) of cases; 65 patients were prescribed cinacalcet alone, while another 14 were given cinacalcet and also underwent PTX. PTX alone was used to treat 7 patients, therefore, a total of 14.7% of patients with 3HPT and hypercalcemia were treated by PTX over this time period. (See Figure 3)

Figure 3. Treatment categorization for subgroup of patients with 3HPT and hypercalcemia after renal transplantation.

3HPT = tertiary hyperparathyroidism, Ca = calcium, PTX = parathyroid surgery

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Of the 618 patients, 41 (6.6%) underwent PTX. The median age and mean body mass index (BMI) were comparable between two groups, with a slight male predominance. Our mean follow up time was 4.4 ± 0.1 years. Table I includes complete clinical characteristics and demographic information for our patient cohort grouped by PTX or no PTX. Univariate analysis revealed that more patients in the non-PTX group received cinacalcet, and that patients who underwent PTX had higher post-transplant serum calcium and PTH levels.

Table I. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

| PTX (n=41) | No PTX (n=577) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, years | 53.8 [44.5, 59.1] | 52.3 [42.6, 61.4] | .873 |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 22 (54%) | 343 (59.2%) | .467 |

| Female | 19 (46%) | 234 (40.6%) | |

|

| |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.8 (27.2-30.5) | 28.6 (28.2-29.0) | .782 |

|

| |||

| Time on dialysis pre-transplant (months) | 28.6 (21.1-36.1) | 24.5 (22.4-26.6) | .292 |

|

| |||

| Cinacalcet | |||

| Yes | 23 (56%) | 394 (68.3%) | .001 |

| No | 18 (44%) | 183 (31.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Serum Calcium (mg/dL) (9-12 mo) | 10.2 (9.9-10.5) | 9.7 (9.65-9.79) | .001 |

|

| |||

| Serum PTH (pg/mL) (9-12 mo) | 209.5 (183.6-235.4) | 140.8 (132.8-148.7) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| GFR (mL/min/1.73m2) (9-12 mo) | 77.5 (69.4-85.6) | 71.0 (69.0-73.0) | .123 |

|

| |||

| Rejection | |||

| Yes | 2 (5%) | 57 (9.9%) | .413 |

| No | 39 (95%) | 520 (90.1%) | |

Results presented as median [25th; 75th percentile], mean (95% CI), or n (%)

PTX = parathyroid surgery, BMI = body mass index, PTH = parathyroid hormone, GFR = glomerular filtration rate

Factors contributing to use of PTX

Using known patient variables at the time of decision making for treatment, a multiple variable, logistic regression model was constructed to determine which factors were associated with undergoing PTX. (See Table II) When adjusted for each other, age, sex, BMI, months on dialysis prior to transplantation, and being prescribed cinacalcet did not appear to affect the decision to undergo PTX. Patients with greater serum calcium levels (p<0.001, OR 2.279) and serum PTH levels (p=0.002, OR 1.004) in the first 9-12 months after transplantation, however, were more likely to undergo PTX.

Table II. A. Multiple variable logistic regression analysis for undergoing parathyroid surgery in all patients with 3HPT.

| A. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Likelihood of parathyroidectomy (n=618), OR, 95% CI | p |

| Age, years | 1.007 (0.977-1.039) | .646 |

| Sex | 1.146 (0.578-2.272) | .697 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.981 (0.915-1.051) | .582 |

| Dialysis time pre-transplant | 0.995 (0.981-1.008) | .432 |

| Cinacalcet | 1.408 (0.670-2.958) | .366 |

| Serum Calcium (mg/dL) (9-12 month) | 2.279 (1.474-3.52) | <0.001 |

| Serum PTH (pg/mL) (9-12 month) | 1.004 (1.001-1.006) | .002 |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73m2) (9-12 month) | 1.01 (0.996-1.024) | .163 |

| Rejection | 0.523 (0.116-2.368) | .400 |

3HPT = tertiary hyperparathyroidism OR = odds ratio, BMI = body mass index, PTH = parathyroid hormone

Outcomes of Parathyroidectomy

41 patients underwent PTX after successful renal transplantation. These patients had both their renal transplant as well as their PTX at a single institution with a minimum of 6 months of follow up time after PTX, and a mean follow up time of 3.0 ± 0.34 years. Of these, one patient underwent PTX both before and after transplantation and was, therefore, excluded from analysis of the specific outcomes of PTX. The remaining 40 patients all underwent bilateral exploration, with subtotal PTX being the most commonly performed operation. Hyperplasia was the most frequent etiology, found in 32 (80.0%) patients. Patients achieved a cure rate of 92.5%, defined as normal serum calcium and PTH at 6-month follow up. Because some patients were normocalcemic prior to PTX, long-term recurrence rate, defined as an abnormal PTH after 6-months, was 10.0%. A total of 5 (12.2%) patients had persistent or recurrent disease. All of these patients underwent subtotal PTX initially, and one patient did not undergo reoperation due to negative localization. The remaining four patients were successfully localized preoperatively and underwent reoperation for removal of the abnormal gland. We had 3 (7.5%) patients report transient hoarseness post operatively and 4 (10.0%) developed transient hypocalcemia, while only one patient (2.5%) had a permanent complication- permanent hypocalcemia. There were no cases of wound infection or hematoma after PTX, despite 3 (7.5%) patients being treated with warfarin. Additionally, 26 patients had pre and post-transplant bone-density scans available; 23 (88.5%) showed improved bone mineral density after PTX. Table III illustrates the full details and outcomes of our patients with 3HPT undergoing PTX.

Table III. Parathyroid Surgery details and outcomes in patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

| Parameter | Incidence (n=40)* |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (55%) |

| Female | 18 (45%) |

|

| |

| Operation performed: | |

| Subtotal parathyroidectomy | 35 (88%) |

| Less than subtotal | 5 (12%) |

|

| |

| Etiology: | |

| Hyperplasia | 32 (80%) |

| Adenoma | 6 (15%) |

| Double adenoma | 2 (5%) |

|

| |

| Cure at 6 month follow up | 37 (93%) |

|

| |

| Recurrence | 4 (10%) |

|

| |

| Symptoms: | |

| Yes | 29 (73%) |

| No | 11 (27%) |

|

| |

| Transient complications: | |

| Hoarseness | 3 (8%) |

| Hypocalcemia | 4 (10%) |

|

| |

| Permanent complications | |

| Hoarseness | 0 (0%) |

| Hypocalcemia | 1 (3%) |

|

| |

| Wound complications | |

| Hematoma | 0 (0%) |

| Infection | 0 (0%) |

|

| |

| Improved Bone Density (n=26) | 23 (88%) |

Results represented as n (%)

One patient who underwent parathyroidectomy had previous parathyroid surgery prior to transplant, and was excluded in parathyroidectomy outcomes analysis

Long-term effect of PTX on calcium and PTH

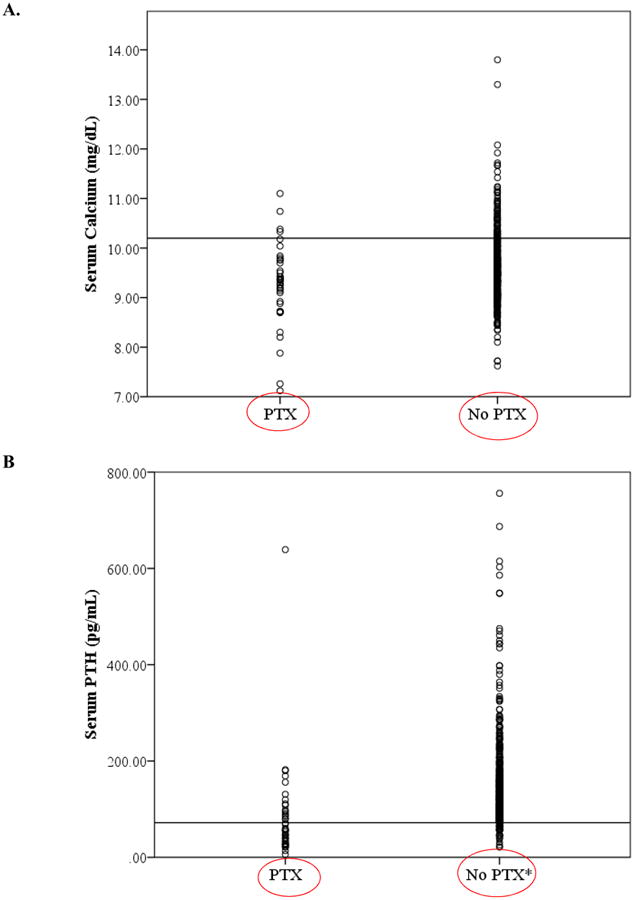

To evaluate the long-term impact of PTX on serum calcium and PTH levels, we examined the serum PTH and albumin-adjusted calcium levels at most recent follow-up. Patients showed a distribution of values for both serum calcium and PTH that were more closely within the normal range than their counterparts who did not undergo PTX. (Figure 4A and 4B) We then used ANOVA and post-hoc testing to examine the serum profiles of those patients who underwent no treatment, cinacalcet alone, or PTX. Significant differences were found with respect to most recent serum levels of albumin-adjusted calcium and serum PTH. In 3HPT patients, the mean serum PTH level in patients who underwent PTX was 82.5 ± 15.7. Those treated with cinacalcet alone achieved a mean serum PTH of 162.1 ± 8.2 (p=0.001), nearly double that of the PTX group. The 3HPT patients who underwent no treatment achieved a mean serum PTH of 142.0 ± 6.9 (p=0.012). In the hypercalcemic 3HPT patients, those patients who underwent PTX achieved normal mean serum levels of albumin-adjusted calcium (9.4 ± 0.15) with mild increases in serum PTH (90.3 ± 28.8) at most recent follow-up. Comparatively, those patients given cinacalcet alone achieved mean serum calcium level at the upper limit of normal (10.0 ± 0.09, p=0.006) with an increased serum PTH (177.0 ± 12.4, p=0.003), and those with no treatment remained hypercalcemic (10.2 ± 0.09, p=0.001) with an increased serum PTH (157.7 ± 12.1, p=0.028).

Figure 4. Dot plot distribution of most current lab values in THPT patients.

A. Serum calcium stratified by parathyroid surgery, reference line drawn at 10.2 mg/dL B. Serum PTH stratified by parathyroid surgery (parathyroid surgery), reference line drawn at 72 pg/mL

*Two PTH values, 1534 pg/mL and 1900 pg/mL not depicted due to scale

Impact of PTX on rejection and renal allograft function

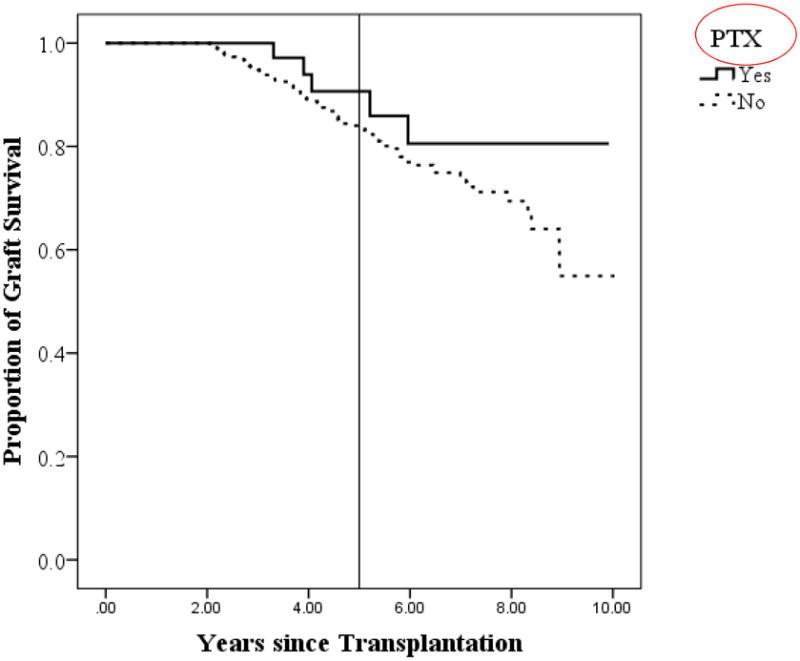

PTX was not associated with episodes of rejection (p=0.400, OR 0.523) in 3HPT patients. In addition, undergoing PTX did not have a negative impact on allograft function at most recent follow-up based on comparable GFR between those who did and did not undergo PTX (73.4 ± 4.4 vs 70.6 ± 1.1, p=0.528). We also analyzed overall renal allograft survival between groups, and found at 5-years the overall allograft survival was 91% in patients who underwent PTX compared to 84% in patients who did not undergo PTX. This difference, however, did not reach statistical significance (p=0.26, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Overall renal allograft survival distributed by patients who did and did not undergo PTX.

Reference line drawn at 5 years. PTX = parathyroid surgery

Discussion

We found a 30.3% (618/2,039) incidence of 3HPT in our contemporary renal transplant population. This high frequency of diagnosing 3HPT is in part due to the increasing success of renal transplantation. According to the National Institutes of Health, while the number of kidney transplants has remained relatively stable since 2005, the numbers of recipients living with a functional kidney continue to increase.11 This difference is also likely related to our 3HPT definition, based on persistently increased PTH that did not necessarily require hypercalcemia in the definition. PTH values were used to define 3HPT because hypercalcemia alone has been shown to be a poor marker for hyperparathyroidism in transplant patients.4 Therefore, in our practice, post-transplant patients with increased serum levels of PTH and normal calcium levels are considered for PTX due to the presence of other factors, such as symptomatology.

It is well recognized that renal function will decline with time, resulting in an increased risk of recurrent hyperparathyroidism in renal transplant patients. Rates of all-cause graft failure are quite substantial in this patient population with five-year failures rates of 29% for deceased donor and 17% for living donor recipients reported by the US Renal Data system.11 Our cohort comprised of 252 patients (40.7%) who had values of GFR between 30-60 mL/min/1.73m2. Evanpoel and colleagues have previously found no significant difference in the natural history of parathyroid function between patients with optimal versus suboptimal graft function.1 The upper limit of normal for serum PTH levels in those with GFR range from 30-59 mL/min is 70 pg/mL, which corresponds closely with the upper limit of normal in our laboratory system.

With the advent of calcimimetics, medical protocols have been used for the treatment of what is classically a surgical disease. Even in the subpopulation of patients with increased PTH levels and hypercalcemia, a clear indication for PTX, only 14.7% (21/143) of patients ultimately underwent PTX. While beyond the scope of this study, further investigation into the cost implication of using cinacalcet off-label versus PTX for 3HPT is warranted. PTX is safe with a high cure rate at 6 months. Our complication rate of 20.0% is comparable to rates that our group has reported previously,12 and is confirmed further by studies from other groups in the 3HPT population. A recent series of 74 renal transplant patients with 3HPT who underwent bilateral neck exploration and PTX reported a perioperative complication rate of 28%, with a 23% incidence of transient hypocalcemia.3

There has also been an overall reluctance in some practices for renal transplant patients with 3HPT to undergo PTX based on previous evidence that PTX was associated with worsening of renal function. Lee and colleagues demonstrated a significant decrease in renal function after PTX.13 However, the study was limited by a small sample size, and this difference was no longer significant once adjusted for other patient factors such as creatinine. As PTH has a positive regulatory effect on renal perfusion and thus GFR, one group postulated that hypoparathyroidism is the mechanism by which PTX decreases allograft function.14 The majority of patients in that study underwent total PTX with auto-transplantation, which places patients at much greater risk for postoperative hypoparathyroidism and is no longer the dominant operative approach in 3HPT patients.

The optimal operative approach in 3HPT is controversial, with some groups advocating subtotal parathyroidectomy,4 while others support bilateral exploration with a more limited resection.12 While four-gland hyperplasia is the dominant etiology in 3HPT, we report a 20% incidence of single and double adenomas which has been reported previously to occur in up to 28% of 3HPT patients.15 Regardless of which operation is undertaken, we demonstrated in this study that GFR is unchanged between those who do and do not undergo PTX. Additionally, patients undergoing PTX did not demonstrate a statistically significantly improvement in overall renal allograft survival.

The expected benefits of PTX in 3HPT include not only normalization of serum levels of calcium and PTH, but also improvement in the metabolic consequences of hyperparathyroidism including bone health and cardiovascular disease.3 Findings from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program, a database launched by the National Kidney Foundation, found that a PTH level greater than 70pg/mL is independently associated with cardiovascular events in those with stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease.16 We demonstrated that PTX portends a distribution of long-term values of serum calcium and PTH toward the normal range. PTX is also expected to correct symptoms such as fatigue and bone pain, which was shown by the 88.5% improvement in bone mineral density on post-PTX bone scans. We report a recurrence rate of 10%, with adjustment for adequate renal function. This finding is likely attributed to recent findings that parathyroid hormone decreases dramatically in the first three months after renal transplantation, 1 and the mean time between receipt of renal transplantation and PTX was well over 2 years.

Our study has several limitations. First is the heterogeneous nature of the follow-up. In order to correct for differences in laboratory values obtained at different times, lab values were captured within 24 hours of each other whenever possible. Whereas serum levels of creatinine and calcium were frequently monitored, PTH levels were far more infrequent thus limiting our useable data points. This limitation also made concurrent serum phosphorous levels difficult to capture. Second, as a tertiary referral center, many patients come from quite a distance, and some ultimately become lost to follow-up. These patients may potentially undergo PTX at an outside institution and, therefore, the incidence of PTX, recurrence, and cinacalcet prescription may be greater than reported. Last, our cohort included 22% of patients who have received more than one allograft. These patients are at greater risk of graft failure and thus hyperparathyroidism. This latter group, however, comprised a small portion of our total study population, and there were no significant differences in the number of re-transplant recipients between the groups (not shown). Additional work will need to be done to further our understanding of the effects of multiple renal transplants on parathyroid function and calcium homeostasis. Importantly, our study examines a contemporary cohort of patients who have undergone isolated renal transplantation and the benefits of PTX. These results may, therefore, be more accurate and generalizable to current patients undergoing renal transplantation.

In conclusion, we quantified the underutilization of PTX, the only known cure for 3HPT, in patients after successful renal transplantation at our institution. PTX is also notably not associated with episodes of rejection or worsening renal allograft function. Therefore, PTX is safe, with high cure rates, and portends long-term improvements of serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the American Association for Endocrine Surgeons, Nashville, TN May 2015

References

- 1.Evenepoel P, Claes K, Kuypers D, et al. Natural history of parathyroid function and calcium metabolism after kidney transplantation: a single-centre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(5):1281–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitt SC, Sippel RS, Chen H. Secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, state of the art surgical management. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(5):1227–39. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triponez F, Clark OH, Vanrenthergem Y, et al. Surgical treatment of persistent hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation. Ann Surg. 2008;248(1):18–30. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181728a2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triponez F, Kebebew E, Dosseh D, et al. Less-than-subtotal parathyroidectomy increases the risk of persistent/recurrent hyperparathyroidism after parathyroidectomy in tertiary hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation. Surgery. 2006;140(6):990–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.039. discussion 997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra AL, Schwarz AA, Wick FH, et al. Successful treatment of hypercalcemia with cinacalcet in renal transplant recipients with persistent hyperparathyroidism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(7):1315–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruse AE, Eisenberger U, Frey FJ, et al. The calcimimetic cinacalcet normalizes serum calcium in renal transplant patients with persistent hyperparathyroidism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(7):1311–4. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. Full Prescribing Information, Sensipar (cinacalcet) [Accessed May 5, 2015];2011 Aug 1; http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/021688s017lbl.pdf.

- 8.Somnay YR, Weinlander E, Schneider DF, et al. The effect of cinacalcet on intraoperative findings in tertiary hyperparathyroidism patients undergoing parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 2014;156(6):1308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.003. discussion 1313-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goolsby MJ. National Kidney Foundation Guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(6):238–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eknoyan G, Levin A, Levin NW. Bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003;42(Supplement 3):S1–S201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Renal Data System. 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichol PF, Starling JR, Mack E, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism treated by resection of a single or double adenoma. Ann Surg. 2002;235(5):673–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00009. discussion 678-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee PP, Schiffmann L, Offermann G, et al. Effects of parathyroidectomy on renal allograft survival. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2004;27(3):191–6. doi: 10.1159/000079810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz A, Rustien G, Merkel S, et al. Decreased renal transplant function after parathyroidectomy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(2):584–91. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilgo MS, Pirsch JD, Warner TF, et al. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation: surgical strategy. Surgery. 1998;124(4):677–83. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.91483. discussion 683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhuriya R, Li S, Chen SC, et al. Plasma parathyroid hormone level and prevalent cardiovascular disease in CKD stages 3 and 4: an analysis from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(4 Suppl 4):S3–10. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]