Abstract

Assorted challenges in physicochemical characterization, sterilization, depyrogenation, and in the assessment of pharmacology, safety, and efficacy profiles accompany preclinical development of nanotechnology-formulated drugs. Some of these challenges are not unique to nanotechnology and are common in the development of other pharmaceutical products. However, nanoparticle-formulated drugs are biochemically sophisticated, which causes their translation into the clinic to be particularly complex. An understanding of both the immune compatibility of nanoformulations and their effects on hematological parameters is now recognized as an important step in the (pre)clinical development of nanomedicines. An evaluation of nanoparticle immunotoxicity is usually performed as a part of a traditional toxicological assessment; however, it often requires additional in vitro and in vivo specialized immuno- and hematotoxicity tests. Herein, I review literature examples and share the experience with the NCI Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory assay cascade used in the early (discovery-level) phase of pre-clinical development to summarize common challenges in the immunotoxicological assessment of nanomaterials, highlight considerations and discuss solutions to overcome problems that commonly slow or halt the translation of nanoparticleformulated drugs toward clinical trials. Special attention will be paid to the grandchallenge related to detection, quantification and removal of endotoxin from nanoformulations, and practical considerations related to this challenge.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Endotoxin, Pre-clinical, Immunotoxicity, Thrombosis, Coagulopathy, Hemolysis, Complement activation, Cytokines, Anaphylaxis, Phagocytosis, Protein binding

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of a drug prior to its use in the clinic includes a variety of tests aimed at identifying potential safety concerns. Pre-clinical safety studies aid drug discovery by helping select the best candidates for development; support clinical development by assisting design, conduct, and interpretation of the toxicology studies; and provide regulatory documentation required for the development and registration of new pharmaceutical products. The immunotoxicity tests became an essential venue in preclinical safety studies because alterations that hamper the immune system’s ability to protect the host from invading pathogens as well as to identify and eliminate dead and damaged cells lead to changes in healthy homeostasis [1, 2] and, consequently, to various pathophysiological conditions, some of which may become life-threatening [3]. Despite rigorous toxicological studies in the (pre)clinical phase, some products may still fail after they enter the market. For example, recent reports from academia, the pharmaceutical industry, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [4–6] indicate that between 1969 and 2005, 10–20% of drugs have been withdrawn from clinical use due to their unfavorable immunotoxicity (anaphylaxis, allergy, hypersensitivity, idiosyncratic reactions, and immunosuppression) [4–7]. This notion further emphasizes the need for a better understanding of a drug’s immunotoxicity and for establishing more predictive approaches to identifying such immunotoxic patterns.

In addition to being used for the delivery of novel drugs, engineered nanomaterials are increasingly explored for their use in reformulating traditional small molecular drugs as well as therapeutic proteins, antibodies, and nucleic acids. Along with such benefits of nanotechnology-reformulation as improving drug solubility and pharmacokinetics, some nanotechnology formulated drugs display reduced immunotoxicity. For example, the nano-albumin-formulated oncology drug paclitaxel does not induce anaphylaxis, whereas the traditionally formulated version of this drug, which contains Cremophor-EL as the excipient, is known to cause anaphylaxis even after a patient’s premedication and when administered via slow infusion [8]. Likewise, the therapeutic protein tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) failed in clinical studies due to the systemic immunostimulation, but after reformulation using polyethylene glycol (PEG) coated colloidal gold nanoparticles it has successfully passed through Phase I trials [9]. Pre-clinical success stories demonstrating the reduction of immunotoxicity by reformulating a traditional drug using nanotechnology carriers include the formulation of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) using chitosan nanoparticles to decrease the hematotoxicity of the drug [10, 11] and the encapsulation of therapeutic antisense oligonucleotides into liposomes to prevent activation of the complement [12] and to reduce cytokine-mediated toxicities [13]. While reformulation using nanoparticles offers the potential to reduce immunotoxicity, ignorance of the immunological properties of a nanotechnology carrier may lead to exaggeration of the drug’s immunotoxicity. For example, immunotoxicity common for therapeutic nucleic acids (TNAs) is the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Some nanoparticles can also induce pro-inflammatory cytokines, and therefore, using such particles to deliver TNAs may lead to enhanced inflammation [14– 16].

Some of the nanotechnology-formulated drugs have already reached the market. The examples include liposomes (e.g., Doxil®), solid lipid nanoparticles (e.g., Leunesse®), nanocrystals (e.g., Emend®), and protein-based nanoparticles (e.g., Abraxane®). Many other types of nanomaterials are in various stages of pre-clinical and clinical development, and include, among others, metal oxides, metal colloids, nanorods, nanowires, emulsions, dendrimers, polymeric nanomaterials, quantum dots, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and graphene-based particles [17]. The most common therapeutic nanoparticles are biodegradable or dissolve in the body (e.g., nanocrystals, emulsions, and liposomes), while others are durable and are expected to accumulate in the body for an extended period of time. The latter materials raise immunological safety concerns due to their tendency to distribute to the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), potentially altering the normal MPS function, leading to pathologies, e.g., tumor growth [18–21]. The U.S. FDA regulates products containing engineered nanomaterials using the same regulatory framework established for all other therapeutics [22]. The main principle of this framework is based on the understanding of a product’s risk versus its benefit, which are assessed on a case-by-case basis for each product [22]. The type of the drug formulated using a nanotechnology platform determines the regulatory guidance to be followed in performing the immunological safety assessment. For example, the International Conference on Harmonization Safety Guidelines Section 8 (ICH S8) is consulted when a nanoparticle formulation contains a drug with a low molecular weight, while ICH S6 serves as the primary guidance when a nanoformulation contains a biotechnology-derived product (e.g., therapeutic protein or antibody) [22]. Nanotechnology-formulated products are often complex and may contain multiple components, including both a low-molecular-weight drug and a protein or an antibody. Such complexity prompted rigorous discussions among industrial and academic investigators about the classification of these products for the purpose of the regulatory approval [23]. The term “non-biological complex drug,” or NBCD, is used in Europe [23], while in the United States, nanotechnology-formulated drugs are often referred to as “combination products” or “innovative drug delivery systems (IDDS)” [24]. Several recent regulatory documents provide guidance to the manufacturing, characterization, and non-clinical safety evaluation of IDDS [25, 26]. According to these documents, the tests relevant to each component of the nanoparticle-formulated drug are required for the combination products, and among other tests, include compatibility with blood components and effects on the immune system function [25, 26].

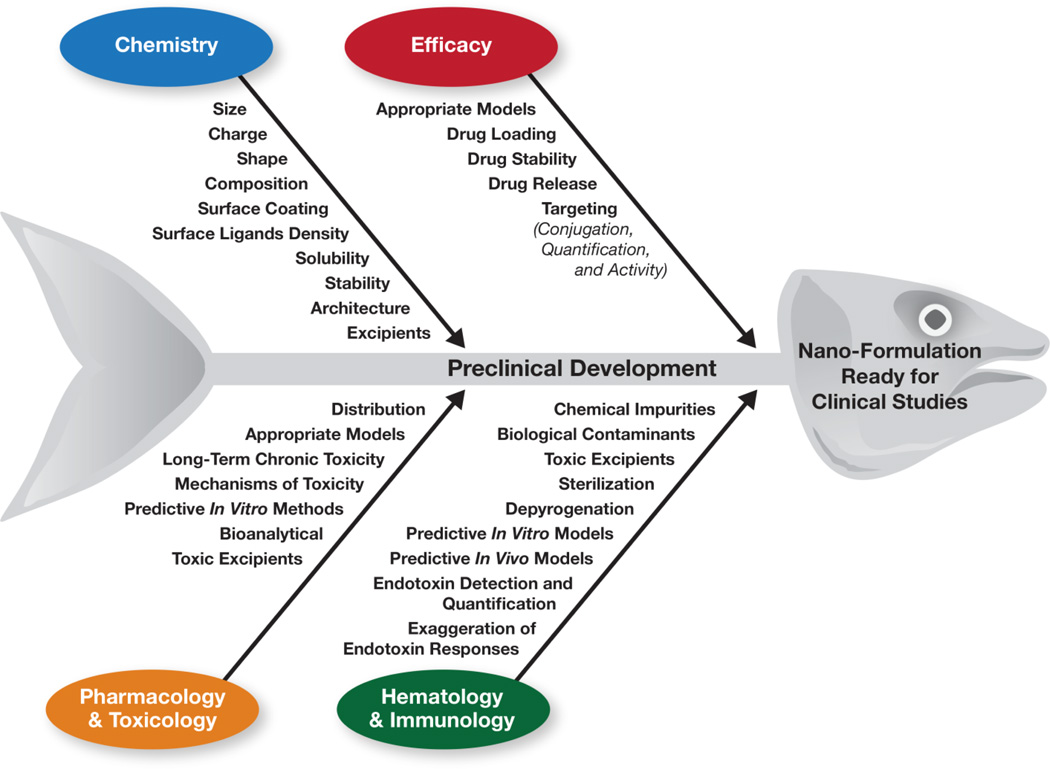

Comprehensive pre-clinical characterization of nanotechnology formulations entails assorted challenges in several major areas, including physicochemical characterization (PCC), efficacy, pharmacology and toxicology (Pharm/Tox), and immunology and hematology (Fig. 1). The PCC challenges include estimating particle size, charge, composition, and surface coatings, as well as determining surface ligand density, solubility, architecture, and stability [27, 28]. Determining efficacy includes such challenges as selection of the appropriate models; drug loading; drug stability; drug release and conjugation; and quantification and determination of biological activity of targeting moieties [29]. Common challenges in Pharm/Tox are related to evaluating the change in a drug’s biodistribution following reformulation using nanoparticle platforms; using sensitive species and relevant animal models to study toxicity; assessing log-term chronic toxicity; determining the mechanisms of toxicity; and addressing other bioanalytical challenges related to the estimation of particle-bound and free drug in biological matrices [30, 31]. The major challenge in immunological characterization is related to the nanoparticle contamination with endotoxin [18, 27, 32–44]. Other immunology/hematology challenges include sterilization and depyrogenation of nanomaterials [43, 45, 46], as well as the in vitro–in vivo correlation between common immunotoxicity tests [47–49]. Some challenges overlap in all areas of pre-clinical characterization. They include developing predictive in vivo models to study efficacy and toxicity, establishing predictive in vitro methods, and distinguishing nanoparticle toxicity from that caused by the presence of chemical impurities and toxic excipients [27]. Challenges in chemistry, efficacy and Pharm/Tox have been reviewed elsewhere [27, 31]. Guidance for conducting immunotoxicity studies required for regulatory approval of the final nanotechnology-formulated drug product has also been provided previously [22]. Herein I will focus on the challenges related to the immunological and hematological characterization performed in the early (discovery-level) phase of preclinical development to select the best lead formulation for further development and assist in the design of the more expensive good laboratory practices (GLP) studies, which provide regulatory documentation necessary for translation of the lead candidates into clinical trials.

Fig. 1. Challenges in pre-clinical development of nanotechnology-formulated drugs.

Pre-clinical studies encompass assorted challenges in four key areas: chemistry, efficacy, pharmacology and toxicology, and hematology and immunology. Critical attributes in particle characterization are summarized in this fishbone diagram according to the relevant area of pre-clinical research.

2. CHALLENGES AND CONSIDERATIONS

2.1. Grand-Challenge: Detection And Quantification Of Endotoxin

Endotoxin is a component of the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria. In contrast to control standard endotoxin (CSE) used as an analytical benchmark to quantify endotoxin contamination in the pharmaceutical products and medical devices, naturally occurring endotoxin is a very stable molecule [50]. Due to its inherent stability and promiscuous presence in biological systems, endotoxin is a potent biological contaminant in bio- and nanotechnology products. The danger of endotoxin contamination is that it induces inflammation at low (picogram level) concentrations, and may lead to serious health conditions, such as septic shock and endotoxin tolerance [51–53]. Moreover, some nanomaterials are not inflammatory themselves but potentiate endotoxin-mediated inflammation. For example, cationic polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers exaggerate endotoxin-induced leukocyte procoagulant activity, which is an essential prerequisite to a serious coagulopathy known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [35, 36]. Likewise, silica- and carbon-based nanomaterials, as well as some metal oxides, are known to exaggerate endotoxin-mediated inflammation in the lungs [54–58]. More than 30% of all nanotechnology formulations fail in early pre-clinical development due to the endotoxin contamination [27, 44]. Because of the nanoparticle interferences with traditional analytical endotoxin-specific tests, the grand challenge of nanomedicine is the detection and accurate quantification of endotoxin in nanoformulations [33, 34, 37, 41, 44]. As such discussing this challenge deserves special attention. One test commonly used to estimate endotoxin pharmaceutical products and medical devices is the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay. Various LAL assay formats, their function to detect and quantify endotoxin, as well as nanoparticle interference and a strategy for selecting the appropriate LAL format were described earlier [33, 34, 37, 44, 59]. Below, I will focus on the types of interference, their source, and potential solutions.

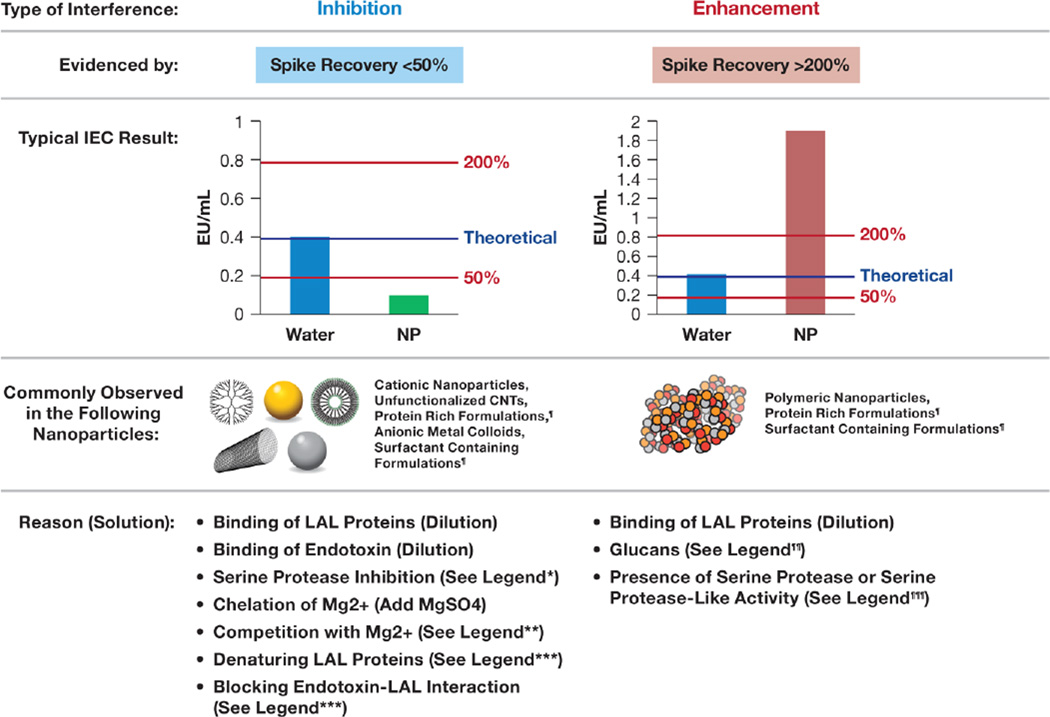

The two types of interferences commonly encountered in pre-clinical studies of nanoparticle-formulated drugs are inhibition and enhancement, which are defined by the U.S. Pharmacopoeia (USP) as spike recovery below 50% or above 200%, respectively [60]. Spike recovery refers to the recovery of CSE in quality control samples prepared by spiking a known amount of CSE into water or a nanoparticle-based formulation. The latter is often referred to as inhibition/enhancement control (IEC), or positive product control. Inhibition leads to the underestimation of endotoxin, while enhancement is often difficult to distinguish from actual endotoxin contamination. Typical IEC results indicative of inhibition and enhancement are summarized in Fig. 2. Inhibition is often seen in cationic nanoparticles, unfunctionalized carbon nanotubes, and anionic metal colloids. LAL inhibition by these nanoparticles occurs because endotoxin binds or adsorbs onto the particle surface. In addition, nanoformulations may contain excipients, which can either chelate or compete with magnesium essential for the activity of serine proteases in the LAL (e.g., ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), citrate, calcium ions), or denature or otherwise inactivate LAL protease activity (e.g., detergents or specific serine protease inhibitors). Chelation and competition with magnesium ions can be overcome by supplementing samples with magnesium sulfate and by adding EDTA at a low concentration, respectively.

Figure 2. Challenges in analyzing nanomaterials for potential endotoxin contamination by LAL assay.

Nanoparticle interference with Limulus amoebocyte lysate assays (LALs) can be detected by inhibition/enhancement controls (IECs), which are prepared by spiking a known amount of control standard endotoxin (CSE) into a quality control (water) or a test nanoparticle. The test results for each of the IECs are then compared to the theoretical value. The non-interfering sample is the one that demonstrates spike recovery between 50% and 200%, according to U.S. Pharmacopoeia Bacterial Endotoxins Test (USP BET) 85 [60]. Spike recovery below 50% is considered inhibition and means that the endotoxin in the test sample is underestimated; recovery above 200% is considered enhancement and signifies that the amount of endotoxin in the test sample may be overestimated or that the test sample is highly contaminated. Most interferences may be overcome by dilutions as long as the tested dilutions are within the maximum valid dilution (MVD) limit [60]. ¶ Proteins and surfactants may either inhibit or enhance endotoxin detection depending on the concentration. Removing or diluting surfactants helps overcome the interference; protein interferences can be eliminated by either heating the sample at 75 °C for 15 min or digestion with endotoxin-free protease (e.g., BioDTech ESP); ¶¶Reconstitution of the lysate in glucan-blocking buffer (e.g., Glucashield) or using recombinant factor C assay helps overcome this interference; ¶¶¶ Proteases (e.g., trypsin) can be inactivated by heating the sample at 75 °C for 15 min; *If proteinaceous in nature, use either heat or endotoxin-free protease treatment to eliminate this interference; **The presence of Ca2+ may inhibit LAL, and in this case, adding low concentrations of EDTA may help overcoming the interference; ***Source specific, consider dilution, removal, or inhibition of the interfering substance.

Enhancement is the type of interference commonly observed with polymeric nanomaterials. Nanomaterials produced via a procedure involving filtration through the cellulose acetate filters are also prone to enhancement because of beta-glucan contamination [44]. The mechanisms of enhancement may include protein binding and consequent change in the protein function, as well as activation of the factor G pathway in the LAL by the beta-glucan contaminants. Detergents and proteins, which may be present in nanoformulations, can cause either inhibition or enhancement, depending on their concentrations. Some of these interferences are not unique to nanomaterials and also serve as a source of the LAL interferences in other pharmaceutical products [61]. Approaches for solving interferences vary and depend on the source and type of interference. Although dilution is the best solution for overcoming interference, it is not always possible because the dilution cannot exceed the so-called maximum valid dilution (MVD), which is determined by the dose of nanoformulation and the sample concentration [60], and many nanoformulations are administered at a high mg/kg dose level. If the source of interference is beta-glucan, inclusion of glucan-neutralizing reagents (e.g., Glucashield®) into the traditional LAL assayor using a recombinant factor C assay helps overcome the interference [37, 44]. If the source of interference is the high protein concentration, which may occur due to either protein excipient (e.g., human serum albumin) or a proteinaceous active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), denaturing the protein by heating the sample to 75 °C or using protease digestion prior to the LAL testing helps overcome the problem. Overcoming the interference originating from endotoxin binding by the cationic particles is possible by adding certain detergents. For example, it has been shown that endotoxin binds to cationic liposomes electrostatically and prevents its recognition by the LAL [62], and that this type of interference can be solved by adding 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) into the test reaction [63].

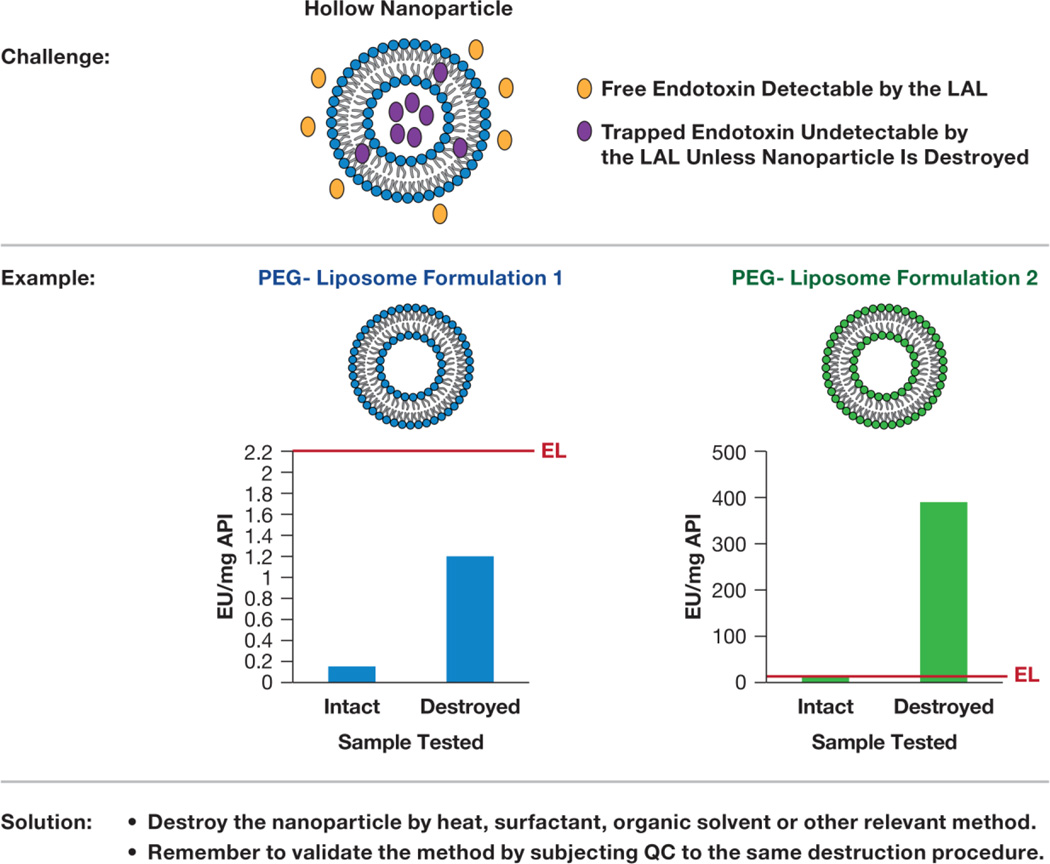

The types of interferences discussed above can be detected by IEC. However, endotoxin may also be entrapped in the hollow nanoparticles (Fig. 3). Such entrapment is common for lipid-based and porous nanomaterials. Entrapped endotoxin is “masked” from the recognition by the LAL assay, resulting in an underestimation of the endotoxin in formulations, even when CSE spike recovery falls within the USP acceptable limits of 50–200% [60]. The solution for this type of interference is to destroy the integrity of the nanoparticles prior to the LAL analysis [64, 65]. It is important to note that when any sample manipulation is used to recover entrapped endotoxin, it is essential to prepare a quality control sample (LAL-grade water with a known concentration of CSE) and subject it to the same manipulation in order to verify that the destruction procedure eliminates only nanoparticle interference and does not inactivate the endotoxin.

Figure 3. Nanoparticle interference with LAL is not detectable by the IEC.

Endotoxin may get trapped by lipid and/or hollow nanoparticles during synthesis. Only free endotoxin is detectable by the LAL; trapped endotoxin is masked from the recognition. Case studies show examples of 2 PEG-liposomes in which particle destruction by heat resulted in higher endotoxin recovery. In the case of liposome 1, the higher endotoxin level recovered from the particle is still within the endotoxin limit (EL), shown as a red line. In case of the liposome 2, the recovered endotoxin is above the EL. QC: quality control prepared by spiking a known amount of endotoxin into LAL-grade water; API: active pharmaceutical ingredient; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Several studies suggest that applying one LAL format may be insufficient to obtain accurate quantification of the endotoxin levels in the nanoformulation [33, 34, 37, 41, 44]. One way to overcome this challenge is to select the LAL assay type based on the nanoparticle’s physicochemical properties and perform LAL assays using two different formats for the same formulation, and then to follow the comparison between the test results. When the data from two formats are comparable, the LAL result is reported; when the data show a more than 25% difference, then a bioassay is used to verify LAL findings [59]. Two common biological assays are used: the rabbit pyrogen test (RPT) and the macrophage activation test (MAT) [44]. We have reported earlier that both RPT and MAT are very helpful in verifying ambiguous LAL findings; however, the application of these methods may be limited by the type of drug. For example, using a MAT to assess the endotoxin levels in nanoparticle formulations containing cytotoxic oncology drugs results in an underestimation of endotoxin contamination in such formulations due to the drug’s cytotoxicity to macrophages [34]. Several endotoxin-neutralizing reagents have been traditionally used to discriminate between endotoxin- and non-endotoxin-mediated inflammation. Such reagents include cationic amphiphylic drugs (polymyxin B [PMB], pentamidine, primaquine, trifluoperazine, chlorhexidine); Rhodobacter sphaeroides lipopolysaccharide (LPS); and endotoxin receptor Toll-Like Receptor (TLR4) -neutralizing antibody (reviewed in [44]). Some of them, e.g., cationic amphiphilic drugs, are species independent, while others, e.g., TLR4-neutralizing antibody and R. sphaeroides LPS, are species specific. For example, R. sphaeroides LPS antagonizes E. coli LPS in human and murine cells but acts like an agonist in equine and hamster cells, presumably because of the differences in components of the endotoxin receptor complex [66, 67]. Because of these nuances and a broader availability, PMB is the most commonly used reagent; however, it may affect the integrity of anionic nanoparticles, and therefore, its use should be accompanied by the assessment of nanoparticle physicochemical properties with and without PMB [44]. The same is true for any other cationic amphiphylic molecules used to inhibit endotoxin. When the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory (NCL) obtains a positive MAT result for a nanoformulation, we apply a panel of inhibitors, including pentamidine, TLR4-neutralizing antibody, and R. spheroides LPS. Endotoxin-mediated cytokine production is expected to decrease with all of these reagents despite their mechanism of action. In our experience, the inclusion of these control reagents is important for ruling out potential particle effects on the secretion of pyrogenic marker cytokines by the macrophages. Such data is also informative to the owners of the pyrogenic nanoformulations because it helps their understanding whether to switch to a different platform (in case the platform per se is pyrogenic) or to optimize the synthesis procedure to eliminate the endotoxin (in case pyrogenicity is the result of endotoxin contamination).

2.2. Sterilization And Depyrogenation

While any nanotechnology-based formulation may become contaminated with endotoxin during synthesis, formulations containing plasmid DNA or recombinant proteins are especially prone to contamination because plasmid DNA and recombinant proteins are traditionally generated using bacterial strains, particularly E.coli. For such formulations, additional endotoxin purification steps may be required prior to adding these biological moieties to nanoparticles. The best way to minimize endotoxin contamination is to optimize the synthesis of nanomaterials in such a way that prevents the contamination. However, if, after all such efforts, a nanoformulation still contains endotoxin at levels exceeding the USP limit of 5EU/kg/h, a purification (i.e., endotoxin removal) or depyrogenation (i.e., endotoxin inactivation) of the nanomaterial is needed prior to its use in biomedical applications and immunotoxicity tests. Currently, there is no guidance regarding the acceptable endotoxin limit for formulations containing nanoparticles capable of enhancing endotoxin-mediated inflammation. Intuitively, when such a property is identified for a given nanoparticle, it is important to purify and depyrogenate the particle so it is essentially endotoxin free. Methods commonly used for endotoxin removal from recombinant proteins and nucleic acids are reviewed in detail elsewhere [68–72]. These methods cannot be universally applied to different types of nanoparticles, as they may affect the integrity of some nanomaterials. For example, a traditional and commonly used depyrogenation method is to expose a material to extreme temperature for a prolonged time (at least 30 min at ≥ 200 °C). Although this method is very efficient for inactivating endotoxin, it may not be tolerated by many engineered nanomaterials, especially those that contain such biological components as targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies or recombinant receptors), active pharmaceutical ingredients (e.g., therapeutic proteins or antibodies), or macromolecular excipients (e.g., albumin). Nevertheless, this method is the best and most cost efficient for depyrogenation of glassware and other common laboratory tools used in the synthesis of nanomaterials. Ethylene oxide and gamma irradiation are also commonly used traditional methods that can be applied for both sterilization and depyrogenation. The main limitation of these methods is that many polymer-based nanoparticles do not tolerate ethylene oxide, and some nanoparticles (e.g., silver colloids) do not withstand gamma irradiation [44–46].

Elimination of endotoxin from nanoformulation can be achieved through several approaches, including: evaluation of the starting materials and depyrogenation of those that contain high levels of endotoxin; terminal sterilization and depyrogenation, provided these approaches are not destructive to the final nanoformulation; and extraction of endotoxin from the final formulation. For example, Triton X-114 extraction, as described by Aida and Pabst [68] for recombinant proteins, has been successfully applied for endotoxin extraction from a combination product composed of a polymer-based carrier, polyethylene glycol surface coating, an endosome escape moiety, and a therapeutic nucleic acid [33]. Common methods used for sterilization and endotoxin inactivation are summarized in Table 1. The applicability of these methods to different types of nanotechnology platforms has been reviewed in detail elsewhere [43].

Table 1. Methods commonly used for sterilization and depyrogenation.

Information presented in the table is prepared based on references 43, 68–72.

| Depyrogenation | Endotoxin Removal | Sterilization |

|---|---|---|

| 200 °C ≥ 30 min | Triton-X114 extraction | Autoclaving |

| Ethylene oxide | Ultrafiltration | Filtration |

| Gamma-irradiation | Anion-exchange chromatography | Gamma-irradiation |

| Acid hydrolysis | Polymyxin B columns | Ethylene oxide |

| Alkylation | Affinity adsorption | Formaldehyde |

| Hydrogen-peroxide gas plasma | Immunoaffinity chromatography | Gas-plasma |

| Soft hydrothermal process | Hydrophobic interaction chromatography |

2.3. Selecting Assays And Controls

The selection of an appropriate test model, end point, and positive and negative controls, as well as the identification of nanoparticle interference with in vitro assays, represent common challenges in nanoparticle immunotoxicity studies. Other challenges relate to the consideration of the role of nanoparticle biodistribution and metabolism when interpreting in vitro immunotoxicity data, and the ability of in vitro tests to accurately predict immunotoxicity in vivo [47, 48].

2.3.1. Selecting appropriate cells and toxicity end points

In vitro cytotoxicity assays involving an immune cell line are not good indicators of nanoparticle immunotoxicity because a single cell line does not accurately represent the various types of immune cells (e.g., monocytes, macrophages, T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells) and because such assays do not allow for the evaluation of the immune cell systemic function. A better approach to understanding immunocompatibility of nanoformulations in vitro is to create a battery of in vitro immunotoxicity assays involving multiple primary cell types and estimate both the integrity of the cells and their function. A recent study conducted by several European laboratories to understand the suitability of various in vitro cytotoxicity methods as well as the more specific monocyte and T-cell immunostimulatory assays demonstrated the need for method harmonization as well as for standardization of the reagents and procedures used to estimate nanoparticle cytotoxicity and its effect on the immune cells [40]. Some nuances with analyzing cytotoxicity and immunotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles have also been recently discussed [73]

2.3.2. Selecting appropriate positive and negative controls

The choice of appropriate controls requires understanding the specificity of different materials to the end point of interest. For example, cytotoxic compounds are good controls for cell viability assays, but they are not optimal for assays assessing immune cell function. Moreover, due to the inherent differences between different cell types, transformed cell lines, and mechanism of action of cytotoxic compounds, the compound’s potency may differ between the cell types and immune cell lines, which may require adjusting the compound concentration or choosing different compound. Immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive compounds are good controls for functional assays; however, their concentration has to be selected based on the cell viability tests, so that non-cytotoxic concentrations are used. Often, different controls are also needed depending on the assay end point. For example, to simulate the production of Th1 cytokines, bacterial LPS is better than phytohemagglutinin-M (PHA-M), but PHA-M is better to induce Th2 type cytokines. When a nanoparticle carries a therapeutic nucleic acid, the analysis of type I interferons is a more sensitive indicator of the immunostimulation. In this case, using ligands for TLR3, TLR7, or TLR9 provides more relevant and better positive control. For example, oligonucleotide ODN2216 is very potent in inducing type I interferons in peripheral blood mononuclear cells commonly used for in vitro cytokine and interferon induction [74]. Often, researchers prepare cocktails containing several immunostimulatory compounds, including cytokines and/or various TLR ligands (e.g., LPS, polyinosinic polycytidylic acid, peptidoglycan, and resiquimod) for use as a positive control in immunological in vitro tests [75]. PHA-M is a good positive control for the leukocyte proliferation assay; however, one has to keep in mind that PHA-M is mitogenic to T cells, so if proliferation of B cells is of interest, then using LPS is more appropriate. Other positive controls stimulating lymphocyte proliferation are concanavalin A or a combination of CD3- and CD28-specific antibodies for T cells, and S. typhimurium mitogen (STM) or a combination of anti-CD40 and IL-4 for B cells. If antigen-dependent leukocyte proliferation is of interest, neither LPS nor PHA-M is appropriate; instead, a specific antigen (e.g., flu hemagglutinin) should be used. When available, in addition to the traditional immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive compounds (e.g., LPS, PHA-M, zymosan, dexamethasone), nanoparticle relevant controls should be included. For example, nanosized micellar excipient Cremophor EL is known to cause complement activation, which is responsible for the hypersensitivity reaction to Cremophor EL–formulated paclitaxel (Taxol) [76, 77]. Likewise, complement activation–related pseudoallergy (CARPA) is the known undesirable side effect of the PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin formulation Doxil [78]. For these reasons, the inclusion of Taxol, Cremophor-EL, or Doxil into the in vitro complement activation assay serves as an internal nanoformulation-relevant positive control.

2.3.3. Understanding the impact of endotoxin on the assay results

Early stage preclinical development often entails multi-parameter optimization of nanoparticle-based formulations. While estimation of endotoxin, sterility and depyrogenation are important steps during this phase, calculation of the endotoxin limit is often not feasible because the information about the maximum dose at which the nanoformulation will be used is not known at that time and the sample concentration may change during optimization process. Ideally, early development stage nanoparticle-based formulations should be endotoxin free. However, they oftenly contain some endotoxin and focusing the development efforts on depyrogenating the formulation may leave behind addressing other critical attributes. For example, one may optimize the synthesis to have pyrogen-free particle which is completely inefficacious or have undesirable toxicity unrelated to endotoxin. It is important to optimize nanoparticle properties to achieve best stability, toxicity, pharmacokinetics and efficacy profiles of the lead formulation, but running such efforts in parallel is a common challenge. A frequent question therefore for many researchers during this stage is whether or not the amounts of endotoxin detected in the formulation will affect the results of in vitro tests used to optimize its biological properties. Below I will review few points which are helpful in prioritizing biological tests when the test particle is known to contain some amounts of endotoxin but the information enabling the comparison of this level to the USP-mandated limits is unavailable.

First important point is to consider the sensitivity to endotoxin between test-models used for in vitro and in vivo toxicology. This property widely varies between different species: humans are more sensitive than rodent species commonly used in the preclinical toxicity studies. For example, according to different sources the list of species organized in the order of decreasing sensitivity to the endotoxin will be either human, horse, rabbit, dog, swine, guinea pig, hamster, Rhesus monkey, mouse and rat [79] or human, rabbit, sheep, calves, guinea pig, hamster, dog, rat, mouse, Rhesus monkey [80]. This means that if a preclinical study is conducted in vitro using human blood cells or in vivo using rabbits, then even low levels of endotoxin in the test-formulation will likely lead to endotoxin-mediated inflammatory reactions, however if the study is conducted in rats or mice, the same level of endotoxin contamination at the same dose of the tested material will not pose such concern. Another important factor to recognize is the difference in sensitivity to endotoxin within the same species. For example, rats of Wistar strain are more resistant to endotoxin than Sprague-Dawley rats [79]. For mice the strains are listed in the order of decreasing sensitivity to endotoxin as follows: DDY, ICR, CD1, DBA/2, DDD, C57/BL6J, A/J, C3H/HeN, Crj, Balb/c, C3H/HeJ and C57Bl10/ScCr [80]. The two strains (C3H/HeJ and C57Bl10/ScCr) are unresponsive to LPS due to alterations in the TLR4 gene, and as such they may serve as a useful tool in situations when undesirable inflammatory reactions were noted during animal studies and one wants to discriminate between the particle- and endotoxin-mediated reactions. Another interesting notion is that even in the endotoxin sensitive species different systems (e.g. MPS and complement) show different responsiveness to endotoxin. For example, in the highly endotoxin-sensitive species such as human, monocytes produce cytokines in response to picogram quantities of endotoxin while complement system is activated only by milligram quantities [81]. In practical world it means that if a nanoparticle contains 1 endotoxin unit, which is equivalent to approximately 100pg of endotoxin, per milligram of API and the highest concentration of the formulation assessed in the in vitro cytokine release assay using human whole blood is 10 mg of API/mL, the final concentration of the contaminating endotoxin (1ng/mL) will complicate the interpretation of the test results. However, if the same nanoparticle will be used in the in vitro complement activation test, this level of endotoxin is not a concern. One always has to consider amount of endotoxin in nanoparticles in relation to the nanoparticle dose used in toxicological studies to understand whether it will affect the data. In addition, it is important to remember that some nanoparticles may exaggerate inflammatory properties of endotoxin, and that endotoxin may change physicochemical properties of some nanomaterials. While a lot of data is available to guide researchers about testorganism and test-system sensitivity to endotoxin, the data about endotoxin effects on nanoparticle physicochemical properties as well as particles effects on inflammatory properties of endotoxin are scarce. The unique nature of each nanoformulation suggests that the best way to understand the effects of endotoxin on nanoparticle physicochemical parameters and to assess nanoparticle effects on inflammatory properties of endotoxin is to include relevant controls into material characterization.

2.3.4. Considering the role of nanoparticle biodistribution and metabolism

In vitro immunotoxicity testing of engineered nanomaterials is often done with the assumption that all nanoparticles administered to the body stay in circulation or accumulate in the target organ represented by a given cell line. Nanoparticle-unique physicochemical properties may affect the biodistribution of both the nanoparticle and the drug it carries [82], which creates a significant challenge for in vitro tests. For example, the myelosuppression test, which is commonly used in immunotoxicity studies, evaluates the effect of a test substance on bone marrow precursors. According to the decision tree used for in vitro testing of direct immunotoxicity of xenobiotics and low-molecular-weight pharmaceuticals, if the test compound is found positive in this test, the compound is considered immunotoxic and no additional tests are needed [83]. However, if the nanoparticle does not distribute to the bone marrow, performing an in vitro assay using bone marrow cells would be irrelevant to the interpretation of the particle toxicity in vivo. There is now sufficient evidence for making an educated guess about the potential particle distribution to the bone marrow based on existing knowledge of nanoparticle physicochemical properties. For example, it is now widely recognized that nanoparticles without a protective coating, such as PEG as well as PEGylated lipid-based particles are taken by the phagocytic cells of the MPS [84–86]. Such particles have greater potential to distribute to the bone marrow, and therefore, testing these particles for myelosuppression is reasonable in vitro, using colony-forming assays, e.g., CFU-GM.

Drug metabolism is another systemic process, which traditional in vitro immunotoxicity tests do not emulate faithfully. If there is a prior knowledge or an indication of a drug being metabolized, one has to assess the metabolism of a nanoparticle-formulated drug prior to designing an immunotoxicity study. Such an assessment can be included in the immuntoxicity tests by either introducing microsomes or co-culturing immune cells with engineered cell lines expressing the cytochrome P-450 enzyme [83, 87–89]. However, when selecting such an approach, one should consider the type of immune assay. For example, Langezaal et al. demonstrated that adding microsomes into the whole blood cytokine assay does not interfere with the test, while co-culture with P-450-expressing cells interferes with the cytokine secretion [89]. If no prior knowledge about a particular immunoassay exists, either metabolism approach may be used, but the assay performance should be qualified to rule out the interference.

2.3.5. Nanoparticle interference with in vitro assays

Composition, size, surface chemistry, surface area, color, charge, and catalytic properties of engineered nanomaterials have all been recognized as attributes that interfere with common in vitro assays [38, 40, 90–92]. Contamination of commercial metal oxide nanomaterials with bacterial endotoxins or chemical synthesis byproducts, particle agglomeration in cell culture media, and optical interference limit the utility of in vitro assays for immunotoxicity testing [38, 40]. For example, carbon nanotubes were shown to cause false-positive results in cell viability assays because of their interaction with MTT-formazan crystals [93]. ELISA analysis of the immune-cell supernatants containing carbon-based nanoparticles was reported to be associated with falsenegative results due to the cytokine adsorption to the particle surface, which masked the cytokine from recognition by the cytokine-specific antibody [91]. The presence of surfactants and the intrinsic fluorescent and catalytic properties of many nanoparticles may also lead to over- or underestimation of their toxicity [48].

2.3.6. In vitro–in vivo correlation

As evidenced by the recent clinical trial outcome of the biotechnology product TGN1412, conducting an in vitro test using peripheral blood mononuclear cells helps prevent toxicities not identified by pre-clinical in vivo studies using rodents and nonhuman primates and is essential for saving patients’ lives [94–99]. While using animal models is unarguably important and should not be excluded from pre-clinical toxicity studies of nanoformulations, supplementing the in vivo studies by informative predictive in vitro assays using human blood–derived mononuclear cells helps avoid mishaps like the one that ruined the reputation of a biotechnology firm and fueled the public fear of experimental therapeutics [95, 97, 98]. Since the toxicities commonly observed with nanoparticles is not unique to nanotechnology-based products, we should leverage existing knowledge of pre-clinical development of other types of drugs (small molecules, biotechnology products, therapeutic nucleic acids) and use best practices to develop nanotechnology-formulated drugs. Common markers for acute toxicities in nanoparticle are: hemolysis, complement activation, thrombogenicity, phagocytosis, pyrogenicity, and cytokine induction. Most of these toxicities can be rapidly assessed in vitro prior to more resource- and time-consuming in vivo studies. Lower cost and higher throughput of in vitro assays made them very attractive for the early-phase pre-clinical studies and forced many researchers to estimate the correlation between these in vitro tests and their relevant in vivo counterparts. These efforts led to the realization that many in vitro tests are helpful in identifying acute toxicities. For example, performing in vitro blood compatibility assays was shown to be helpful in identifying acute toxicities due to the hemolysis and anaphylaxis [100–106]. Understanding of a nanoparticle’s plasma protein binding capacity is now widely accepted as a “marker” for the particle’s clearance from circulation and distribution into the cells of the MPS [107–112]. The induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro is considered a marker of cytokine-associated toxicities in vivo, including (but not limited to) DIC, pyrogenicity, and hypercytokinemia. While pyrogenicity and a cytokine storm can be predicted using in vitro assays utilizing human blood specimens, the interpretation of in vitro data to predict DIC and thrombosis is not as straightforward. Vascular thrombosis and DIC were reported as common toxicities for certain types of engineered nanomaterials [35, 113–115]. However, screening for these toxicities in vitro using one assay is complicated because blood coagulation involves multiple players (platelets, coagulation factors, leukocytes, and endothelial cells). Therefore, we suggested that several in vitro coagulation assays targeting the activity of platelets, endothelial cells, leukocytes, and plasma coagulation factors can be used to identify potentially thrombogenic nanoparticles, but such studies need verification by an in vivo study in the sensitive species (e.g., rabbits or dogs) [47]. Immunosuppression is another important type of immunotoxicity, which can be assessed initially through assays targeting multiple immunological end points. Analysis of the macrophages’ ability to perform phagocytosis of pathogens following exposure to nanoparticles and assessment of leukocyte function are the most popular methods for identifying immunosuppressive nanocarriers [3]. In vitro assays probing macrophage phagocytic function and leukocyte proliferation showed good correlation with relevant in vivo immunotoxicities (reviewed in [47]). More details about these assays, considerations, case studies, and in vitro–in vivo correlation have been reviewed earlier [47].

2.4. CONSIDERING NANOCARRIER CONTRIBUTION TO THE FORMULATION’S IMMUNOTOXICITY

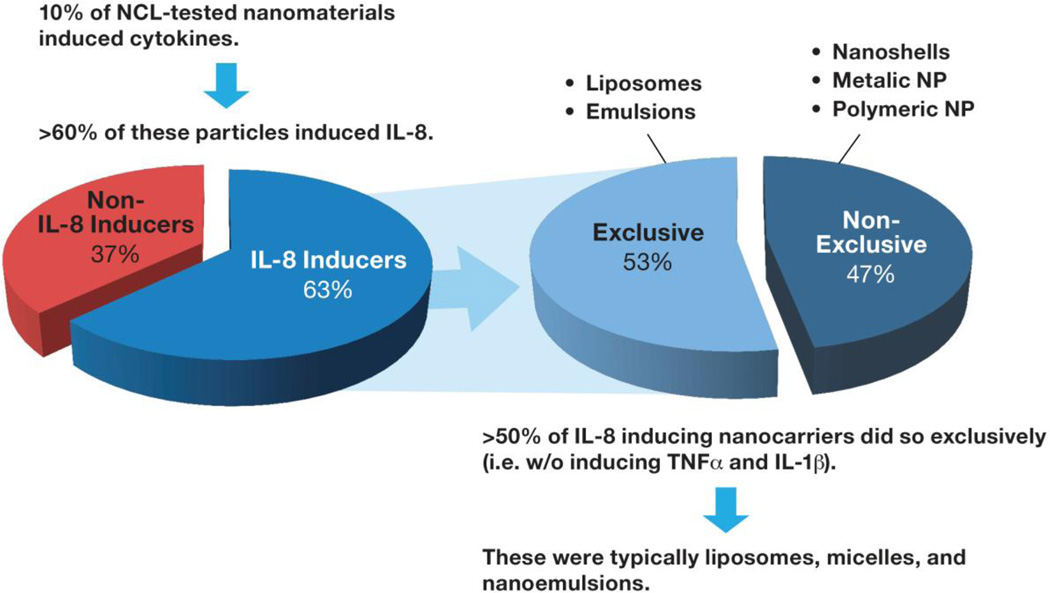

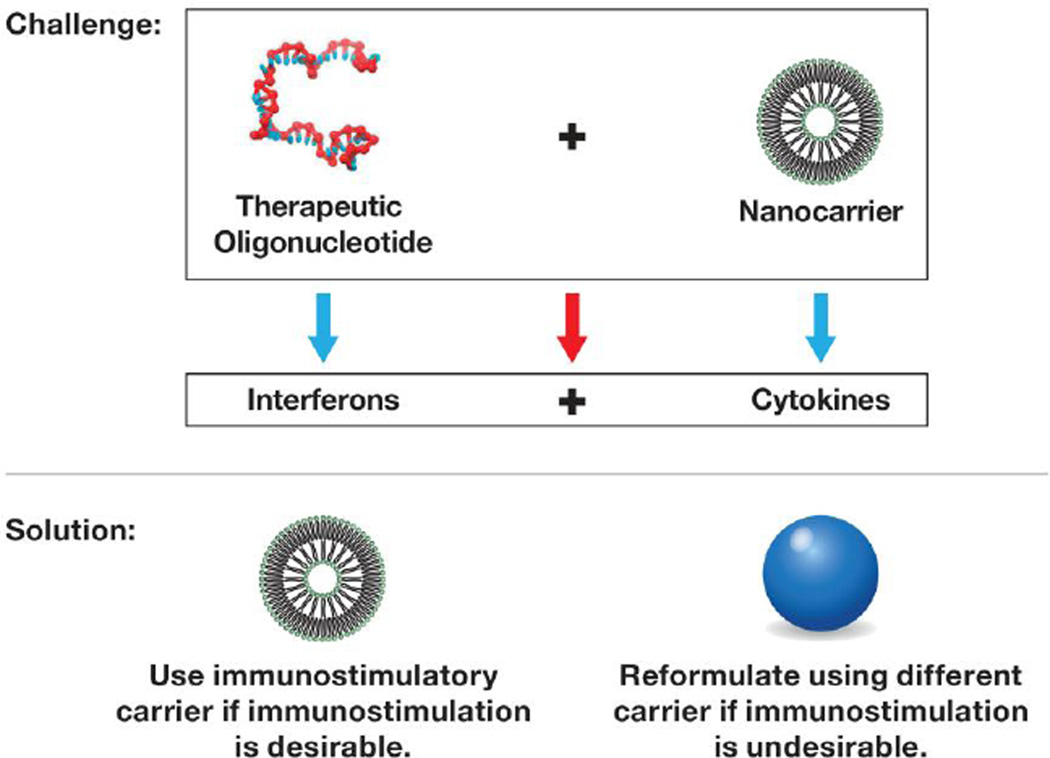

It is important to realize that many nanotechnology carriers, formulation excipients, and drugs are not immunologically inert and can either stimulate, modulate, or inhibit the immune system function or affect its structure [116–118]. For example, gold nanoparticles have been shown to inhibit TLR9 function and reduce immune cell response to bacterial DNA [119]. The gold colloids and their therapeutic payload can be masked from the immune recognition by adding the PEG coating to the particle surface [120]. Dendrimers and certain cationic polymers are pro-thrombogenic in that they induce platelet aggregation and promote DIC-like reactions [35, 113–115, 121]. PEGylated liposomes with an oval shape activate the complement system, which is responsible for acute anaphylactic reactions [77]. Cremophor-EL, a nanosized micellar excipient commonly used to solubilize hydrophobic drugs, activates the complement system and induces mononuclear cells to produce pro-inflammatory chemokine IL-8 without inducing TNFα and IL-1β [76, 122]. Some nanoparticles (e.g., cationic dendrimers, and carbon-based and titanium dioxide particles) are not immunostimulatory alone but can exaggerate endotoxin-mediated inflammation [47, 54– 57]. Iron oxide nanoparticles have been shown to be immunosuppressive and inhibit the antigen-mediated antibody response [123]. Approximately one-tenth of the nanomaterials evaluated by the NCI NCL induced pro-inflammatory cytokines; more than 60% of these materials induced pro-inflammatory chemokine IL-8, and more than 50% of IL-8-triggering nanoparticles did so exclusively, i.e., without inducing TNFα and IL-1β (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the exclusive IL-8 inducers were typically liposomes and emulsions. The mechanism of such exclusivity is not fully understood, but a recent study suggests the involvement of an oxidative stress–mediated stabilization of the presynthesized IL-8 mRNA maintained by the mononuclear cells [122]. Sakurai et al. have also reported that the cytokine-inducing properties of the lipid-based carriers are greater than those of other types of platforms [124]. Many small molecule drugs (e.g., doxorubicin, paclitaxel, dexamethasone) are immunosuppressive and affect the immune system by targeting diverse cell types and molecular pathways [125]. Biotechnology-derived drugs (therapeutic proteins and antibodies) are immunostimulatory and can induce cytokines and the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADA) [118]. Common immuno- and hemato-toxicities that delay the clinical development of therapeutic nucleic acids are the prolongation of plasma coagulation time, fever, and fever-line reactions triggered by cytokine secretion as well as effects on neutrophils[126]. This is why understanding the immunocompatibility of each component of a nanoformulation is essential for developing safe and effective nanomedicines. As discussed earlier, nanotechnology holds a great potential to reduce the immunotoxicity of traditional drugs; however, when the immunotoxicity of a selected nanotechnology platform overlaps with that of the drug it is intended to deliver, the final formulation of the drug and the nanotechnology platform may exhibit even greater synergistic immunotoxicity. For example, phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotides and PEGylated liposomes share the ability to activate the complement system, and thus combining them in one formulation is expected to lead to the augmented toxicity related to the complement activation (e.g., CARPA syndrome) [77, 127]. Likewise, using lipid-based nanocarriers for delivery of siRNA or other types of therapeutic oligonucleotides is not ideal because an interferon-inducing oligonucleotide combined with a cytokine-inducing carrier in the final formulation triggers the production of both cytokines and interferons (Fig. 5). The solution for overcoming the exaggerated immunotoxicity in this case is to reformulate cytokine-inducing drug (e.g. siRNA) using different nanotechnology-carrier. Avoiding the use of nanocarriers able to amplify immunostimulatory properties of low concentrations of endotoxin [35, 128] when formulating drugs inherently prone to containing traces of endotoxin due to production using bacterial cells (e.g. recombinant proteins) is important to prevent increased immunostimulation by the carrier and antigenicity of the therapeutic payload [129–131].

Figure 4. Trend in pro-inflammatory cytokine induction by nanotechnology carriers.

Of the nanomaterials tested by the NCL during its 10 years of operation, approximately 10% induced cytokines; many of them induced IL-8, and the majority of the IL-8 inducers did so exclusively (i.e., without inducing TNFα and IL-1β). These materials were typically liposomes, micelles, and nanoemulsions. The example of such a micelle which can induce IL-8 without triggering TNFα and IL-1β production is nanosized excipient Cremophor-EL commonly used to formulate hydrophobic drugs.

Figure 5. Combining a cytokine-inducing nanotechnology carrier with an pro-inflammatory API results in a pro-inflammatory formulation.

Some nanoparticles are pro-inflammatory and induce cytokines. Using such carriers to formulate an API known to induce interferons (e.g., therapeutic nucleic acids) may cause the final formulation to induce both cytokines and interferons. Such a combination may be beneficial when immunostimulation is desirable (e.g., vaccines), but other carriers should be considered when the immunostimulation is unwanted.

3. STRATEGY FOR DESIGNING EARLY PHASE PRE-CLINICAL IMMUNOTOXICITY SCREENING FRAMEWORK

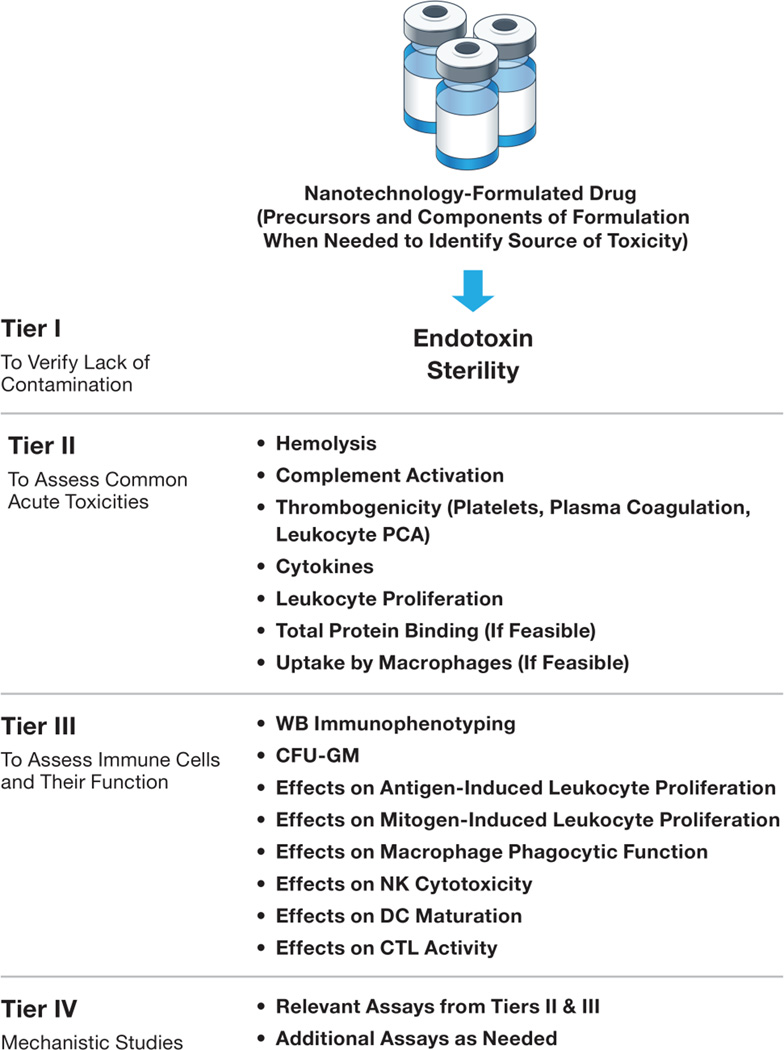

The framework shown in Fig. 6 and described in more detail below is based on the common immunotoxicities that halt the translation of nanotechnology-formulated drugs from the bench to late-phase pre-clinical Investigational New Drug (IND)/Investigational Device Exemption (IDE)-enabling GLP studies, and on the common practice for screening immunotoxic xenobiotics and pharmaceuticals [83]. Since the most common quality issue of nanoformulations in the pre-clinical phase is the potential for contamination with endotoxin, which may confound the results of both toxicity and efficacy studies, the essential first step is evaluation of sterility and endotoxin testing. If the test nanoformulation contains endotoxin at levels above the EL, analysis of its components and precursors is usually helpful for pinpointing the exact source of the endotoxin contamination and pyrogenicity. The decision about the method to use in terminal sterilization/depyrogenation or depyrogenation of individual components followed by repeating synthesis under sterile, pyrogen-free conditions is driven by the type of formulation. The stability of the formulation as well as its individual components to various sterilization and depyrogenation methods is usually considered when selecting the appropriate method. The next steps are intended to assess the nanoformulation for potential interactions with blood components and the immune cells. The second tier of tests includes the analysis of nanoparticle hemolytic properties, complement activation, thrombogenicity (analysis of platelets, plasma coagulation time, and leukocyte procoagulant activity), leukocyte proliferation, and cytokine secretion. If the particle’s physicochemical properties allow it to be isolated from the plasma without affecting its integrity, then assessing the total binding of plasma proteins helps in evaluating the “stealthiness” of the test particles; higher protein binding suggests that the particle will not stay in the bloodstream very long and will be quickly eliminated by the MPS [85, 86]. Studying the identity of the proteins bound to the nanoparticle surface is not essential for understanding its potential to distribute to the MPS, but may be helpful in understanding the mechanism of interaction with certain cell types and toxicity [132, 133]. The potential to distribute to the MPS may affect formulation efficacy [120] and may also lead to toxicity [47], so assessing this potential is an important step. Due to the established correlation between the proteins’ binding to the nanoparticle surface and their uptake by macrophages, another test could be used to assess the stealth properties if the isolation of the particle from plasma is not feasible. This test, which evaluates the particle uptake by macrophages, may also be unfeasible for some nanoparticles (e.g., dendrimers and polymeric nanomaterials) and may require particle labeling with an isotope or a fluorescent probe in order to detect the uptake. To further assess the effects of nanomaterials on the immune system, additional third tier in vitro tests should be considered and include an analysis of both the nanoparticle’s effect on various types of immune cells and functional assays intended for discovering indications of delayed-type toxicities that result from immunosuppression and immunomodulation. These additional in vitro assays include immunophenotyping and assessing activation markers in whole blood specimens; assessing macrophage phagocytic function, antigen- and mitogen-induced leukocyte proliferation, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and NK cell cytotoxicity, and DC maturation; and colony-forming unit assays after exposure to the test nanomaterials. Tier IV studies are intended to understand the mechanism(s) of toxicities identified in tier II and tier III assays. To avoid species differences, human whole blood or its derivatives, or relevant human cell lines are preferable for these in vitro tests. It is important that immunotoxicity is assessed in parallel with other attributes of nanoformulation through physicochemical characterization and pharmacology/toxicology studies. A strategy for designing exploratory toxicology studies for novel drug entities has been described and is also helpful in conducting such assessments for nanotechnology-based formulations [134]. The quantities of nanoparticles available for toxicity studies during early development steps are often limited. It creates a necessity to prioritize toxicity assays so that high likelihood toxicities are identified early on, and the development efforts are focused on more promising formulations. In the Table 2 I summarize nanoparticle-based formulation properties and high likelihood immunotoxicities associated with them. This table can be consulted to select and prioritize assays to select the lead candidate with desirable immunocompatibility profile.

Figure 6. Tiered approach for assessing nanoparticle compatibility with the immune system in vitro during early-phase pre-clinical development.

This framework was developed based on the traditional approach used in discovery-level toxicology for xenobiotics and novel low-molecular-weight pharmaceuticals, and common toxicities for nanoparticle-formulated drug failure in pre-clinical development. The first tier is intended for the identification of microbial and endotoxin contamination, which, when present, may confound results of toxicity and efficacy studies. The second tier is focused on identifying toxicities commonly responsible for nanoparticle failure in pre-clinical studies. This tier focuses on identifying acute toxicities. The third tier is focused on myelo- and lymphotoxicities affecting the immune cell function. This tier aims at identifying potential concerns for the long-term toxicities. The fourth tier is intended for the identification and understanding of the mechanisms of toxicities. It may involve both in vitro and in vivo studies, and is used to inform lead candidate selection and to support the design of pre-clinical GLP studies required for regulatory filings of investigational drugs. The inclusion of individual components of the final formulation along with precursors is helpful in identifying the source of toxicity when the final formulation is found to be toxic. “(If feasible)” refers to the analysis of formulations, which, in these assays, is not trivial because of the particle physical properties and the limitations of currently available methodologies.

Table 2. Properties of nanoparticle-based formulations and high likelihood immunotoxicites associated with these properties.

Information presented in the table is based on the 10 years of applying NCL immunology assay cascade for characterization of over 300 nanoparticle-based formulations as well as on the literature reports [27, 35, 55, 77, 78, 103, 113–115, 126, 135–137]. The information about nanoparticle properties summarized in the left column can be used to prioritize toxicity assays to identify formulations with high likelihood of certain types of immunotoxicities.

| NANOPARTICLE/FORMULATION PROPERTY |

HIGH LIKELIHOOD IMMUNOTOXICITY |

|---|---|

| Nanoparticle or one or more of its components is cationic |

|

| Nanoparticle is formulated to carry therapeutic nucleic acid as API |

|

| Nanoparticle is formulated to carry DNA-intercallating cytotoxic drugs (e.g DXR) |

|

| Formulation contains surfactants |

|

| Formulation is based on PEGylated liposome |

|

| Nanoparticle or formulation is lipid based |

|

| One or more components of nanoparticle/formulation was produced in E.coli |

|

| PEG is not covalently attached or otherwise unstable |

|

| Particle size is above 300 nm ; solid, non-deformable particles with size above 200nm; charged particles |

|

| Nanoparticle is polyanionic or contains polyanionic component |

|

| High aspect ratio particles (e.g. CNT and cellulose) as well as Si and Ti containing particles |

|

API-active pharmaceutical ingredient; MPS – mononuclear phagocytic system; PCA – procoagulant activity; DIC – disseminated intravascular coagulation; PEG – poly(ethylene) glycol; DXR – doxorubicin; CARPA – complement activation related pseudoallergy; IL-8 interleukin 8, also known as CXCL8; IL-1 – interleukin 1; CNT – carbon nanotubes;

- depends on the surface properties of the base nanoparticle, please consult other rows to identify most relevant toxicities.

4. CONCLUSION

The goal of early-phase pre-clinical immunological studies is to obtain an understanding of potential immunotoxic effects of nanotechnology formulations. The in vitro assays are very useful for identifying a lead candidate with the most desirable immunological properties and offer several advantages, including higher throughput, the ability to reduce, replace, and refine the use of laboratory animals, and a faster turnaround. Experience gained with the in vitro immunoassays during the early pre-clinical phase facilitates the design of animal studies and helps reduce the cost by providing information on the type and the mechanisms of immunotoxicity, which may be encountered and can be resolved prior to regulatory filing. Once the lead candidate is selected, further development proceeds with animal studies and specialized immune function tests described in ICH S8 and ICH S6, as appropriate to the given nanoformulation [22].

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. I am grateful to Allen Kane and Nancy Parrish for the help with manuscript preparation; to Dr. Serguei Kozlov for the helpful critique; to the NCL technical staff Barry Neun, Timothy Potter, and Jamie Rodrigues for generating the data using various in vitro immunoassays; to the NCL’s chief toxicologist, Dr. Stephan Stern, and the former NCL chief chemist, Dr. Anil Patri, for sharing their expertise and help with establishing the in vitro–in vivo correlation for immunoassays and with understanding nanoparticle structure activity relationship; and to the NCL Director, Dr. Scott McNeil, for helpful suggestions about the information presented in the manuscript and for providing the opportunity to perform my research at the NCL.

List of Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- API

active pharmaceutical ingredient

- ADA

anti-drug antibodies

- CSE

control standard endotoxin

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- CARPA

complement activation–related pseudoallergy

- CHAPS

3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-

- DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GLP

good laboratory practices

- IEC

inhibition/enhancement control

- ICH S8

International Conference on Harmonization Safety Guidelines Section 8

- IDE

Investigational Device Exemption

- IND

Investigational New Drug

- IDDS

innovative drug delivery systems

- LAL

Limulus amoebocyte lysate

- LPS

lipopolysacharide

- MAT

macrophage activation test

- MVD

maximum valid dilution

- MPS

mononuclear phagocytic system

- NCL

Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory

- NCI’s

National Cancer Institute’s

- NK

natural killer

- NBCD

non-biological complex drug

- Pharm/Tox

pharmacology and toxicology

- PCC

physicochemical characterization

- PHA-M

phytohemagglutinin-M

- PAMAM

polyamidoamine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- B

polymyxin

- RPT

rabbit pyrogen test

- STM

S. typhimurium mitogen

- TNAs

therapeutic nucleic acids

- TLR4

Toll-Like Receptor

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- USP

U.S. Pharmacopoeia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure

The author has no financial information to disclose related to this study.

References

- 1.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luebke R. Immunotoxicant screening and prioritization in the twenty-first century. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:294–299. doi: 10.1177/0192623311427572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DA, Schmid EF. Drug withdrawals and the lessons within. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2006;9:38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysowski DK, Nourjah P. Analyzing prescription drugs as causes of death on death certificates. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:520. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wysowski DK, Swartz L. Adverse drug event surveillance and drug withdrawals in the United States, 1969–2002: the importance of reporting suspected reactions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1363–1369. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilke RA, Lin DW, Roden DM, Watkins PB, Flockhart D, Zineh I, Giacomini KM, Krauss RM. Identifying genetic risk factors for serious adverse drug reactions: current progress and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:904–916. doi: 10.1038/nrd2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, Hawkins M, O'Shaughnessy J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libutti SK, Paciotti GF, Byrnes AA, Alexander HR, Jr, Gannon WE, Walker M, Seidel GD, Yuldasheva N, Tamarkin L. Phase I and pharmacokinetic studies of CYT-6091, a novel PEGylated colloidal gold-rhTNF nanomedicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6139–6149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng M, Chen H, Wang Y, Xu H, He B, Han J, Zhang Z. Optimized synthesis of glycyrrhetinic acid-modified chitosan 5-fluorouracil nanoparticles and their characteristics. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:695–710. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S55255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giacalone G, Bochot A, Fattal E, Hillaireau H. Drug-induced nanocarrier assembly as a strategy for the cellular delivery of nucleotides and nucleotide analogues. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:737–742. doi: 10.1021/bm301832v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimuk SK, Semple SC, Nahirney PN, Mullen MC, Bennett CF, Scherrer P, Hope MJ. Enhanced anti-inflammatory activity of a liposomal intercellular adhesion molecule-1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide in an acute model of contact hypersensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu B, Mao Y, Bai LY, Herman SE, Wang X, Ramanunni A, Jin Y, Mo X, Cheney C, Chan KK, Jarjoura D, Marcucci G, Lee RJ, Byrd JC, Lee LJ, Muthusamy N. Targeted nanoparticle delivery overcomes off-target immunostimulatory effects of oligonucleotides and improves therapeutic efficacy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:136–147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-407742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams MT, Koser ML, Seitzer J, Williams SC, DiPietro MA, Wang W, Shaw AW, Mao X, Jadhav V, Davide JP, Burke PA, Sachs AB, Stirdivant SM, Sepp-Lorenzino L. Evaluation of efficacy, biodistribution, and inflammation for a potent siRNA nanoparticle: effect of dexamethasone co-treatment. Mol Ther. 2010;18:171–180. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afonin KA, Viard M, Kagiampakis I, Case CL, Dobrovolskaia MA, Hofmann J, Vrzak A, Kireeva M, Kasprzak WK, KewalRamani VN, Shapiro BA. Triggering of RNA interference with RNA-RNA, RNA-DNA, and DNA-RNA nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015;9:251–259. doi: 10.1021/nn504508s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Strategy for selecting nanotechnology carriers to overcome immunological and hematological toxicities challenging clinical translation of nucleic acid-based therapeutics. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1163–1175. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1042857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etheridge ML, Campbell SA, Erdman AG, Haynes CL, Wolf SM, McCullough J. The big picture on nanomedicine: the state of investigational and approved nanomedicine products. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Gioacchino M, Petrarca C, Lazzarin F, Di Giampaolo L, Sabbioni E, Boscolo P, Mariani-Costantini R, Bernardini G. Immunotoxicity of nanoparticles. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:65S–71S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon EY, Yi GH, Kang JS, Lim JS, Kim HM, Pyo S. An increase in mouse tumor growth by an in vivo immunomodulating effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J Immunotoxicol. 2011;8:56–67. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2010.543995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadauskas E, Danscher G, Stoltenberg M, Vogel U, Larsen A, Wallin H. Protracted elimination of gold nanoparticles from mouse liver. Nanomedicine. 2009;5:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umbreit TH, Francke-Carroll S, Weaver JL, Miller TJ, Goering PL, Sadrieh N, Stratmeyer ME. Tissue distribution and histopathological effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles after intravenous or subcutaneous injection in mice. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:350–357. doi: 10.1002/jat.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bancos S, Tyner KM, Weaver JL. Immunotoxicity testing of drug-nanoparticle conjugates: regulatory considerations. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 671–685. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crommelin DJA, de Vlieger JSB, Muhlebach S. Defining the position of Non-Biological Complex Drugs. In: Crommelin DJA, de Vlieger JSB, editors. Non-Biological Complex Drugs. Basel: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapsford KE, Lauritsen K, Tyner KM. Current perspectives on the US FDA regulatory framework for intelligent drug delivery systems. Therapeutic Delivery. 2012;3:1383–1394. doi: 10.4155/tde.12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDER. Guidance for Industry: non-clinical safety evaluation of drug or biologic combinations. In: F.a.D.A. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDER. Guidance for Industry and Review Staff: non-clinical safety evaluation of reformulated drug products and products intended for administration by alternative route. In: U.D.o.H.a.H. Services, editor. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crist RM, Grossman JH, Patri AK, Stern ST, Dobrovolskaia MA, Adiseshaiah PP, Clogston JD, McNeil SE. Common pitfalls in nanotechnology: lessons learned from NCI's Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5:66–73. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20117h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clogston JD, Patri AK. Importance of physicochemical characterization prior to immunological studies. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adiseshaiah PP, Hall JB, McNeil SE. Nanomaterial standards for efficacy and toxicity assessment. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2:99–112. doi: 10.1002/wnan.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern ST, Adiseshaiah PP, Crist RM. Autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction as emerging mechanisms of nanomaterial toxicity. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stern ST, Hall JB, Yu LL, Wood LJ, Paciotti GF, Tamarkin L, Long SE, McNeil SE. Translational considerations for cancer nanomedicine. J Control Release. 2010;146:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afonin KA, Grabow WW, Walker FM, Bindewald E, Dobrovolskaia MA, Shapiro BA, Jaeger L. Design and self-assembly of siRNA-functionalized RNA nanoparticles for use in automated nanomedicine. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:2022–2034. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobrovolskaia MA, Neun BW, Clogston JD, Ding H, Ljubimova J, McNeil SE. Ambiguities in applying traditional Limulus amebocyte lysate tests to quantify endotoxin in nanoparticle formulations. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5:555–562. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobrovolskaia MA, Neun BW, Clogston JD, Grossman JH, McNeil SE. Choice of method for endotoxin detection depends on nanoformulation. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2014;9:1847–1856. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobrovolskaia MA, Patri AK, Potter TM, Rodriguez JC, Hall JB, McNeil SE. Dendrimer-induced leukocyte procoagulant activity depends on particle size and surface charge. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012;7:245–256. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilinskaya AN, Man S, Patri AK, Clogston JD, Crist RM, Cachau RE, McNeil SE, Dobrovolskaia MA. Inhibition of phosphoinositol 3 kinase contributes to nanoparticle-mediated exaggeration of endotoxin-induced leukocyte procoagulant activity. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2014;9:1311–1326. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Italiani P, Casals E, Tran N, Puntes VF, Boraschi D. Optimising the use of commercial LAL assays for the analysis of endotoxin contamination in metal colloids and metal oxide nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:462–473. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2014.948090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oostingh GJ, Casals E, Italiani P, Colognato R, Stritzinger R, Ponti J, Pfaller T, Kohl Y, Ooms D, Favilli F, Leppens H, Lucchesi D, Rossi F, Nelissen I, Thielecke H, Puntes VF, Duschl A, Boraschi D. Problems and challenges in the development and validation of human cell-based assays to determine nanoparticle-induced immunomodulatory effects. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen EJ, Henry TB, Zhao J, MacCuspie RI, Kirschling TL, Dobrovolskaia MA, Hackley V, Xing B, White JC. Identification and avoidance of potential artifacts and misinterpretations in nanomaterial ecotoxicity measurements. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:4226–4246. doi: 10.1021/es4052999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfaller T, Colognato R, Nelissen I, Favilli F, Casals E, Ooms D, Leppens H, Ponti J, Stritzinger R, Puntes V, Boraschi D, Duschl A, Oostingh GJ. The suitability of different cellular in vitro immunotoxicity and genotoxicity methods for the analysis of nanoparticle-induced events. Nanotoxicology. 2010;4:52–72. doi: 10.3109/17435390903374001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smulders S, Kaiser JP, Zuin S, Van Landuyt KL, Golanski L, Vanoirbeek J, Wick P, Hoet PH. Contamination of nanoparticles by endotoxin: evaluation of different test methods. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallhov H, Qin J, Johansson SM, Ahlborg N, Muhammed MA, Scheynius A, Gabrielsson S. The importance of an endotoxin-free environment during the production of nanoparticles used in medical applications. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1682–1686. doi: 10.1021/nl060860z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vetten MA, Yah CS, Singh T, Gulumian M. Challenges facing sterilization and depyrogenation of nanoparticles: effects on structural stability and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine. 2014;10:1391–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Nanoparticles and Endotoxin. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of immunological properties of engineered nanomaperials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng J, Clogston JD, Patri AK, Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Sterilization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Standard Gamma Irradiation Procedure Affects Particle Integrity and Biocompatibility. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2011;2011:001. doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.S5-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subbarao N. Impact of nanoparticle sterilization on analytical characterization. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of Immunological Properties of Engineered nanomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Understanding the correlation between in vitro and in vivo immunotoxicity tests for nanomedicines. J Control Release. 2013;172:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. In vitro assays for monitoring nanoparticle intercation with components of the immune system. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 581–634. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith MJ, McLouglin CE, W KL, Jr, G D. Evaluating the adverse effects of nanomaterials on the immune system with animal models. In: Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE, editors. Handbook of immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 639–663. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Majde JA. Microbial cell-wall contaminants in peptides: a potential source of physiological artifacts. Peptides. 1993;14:629–632. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90155-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dobrovolskaia MA, Vogel SN. Toll receptors, CD14, and macrophage activation and deactivation by LPS. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:903–914. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01613-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel SN. Lps: another piece in the puzzle. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:295–300. discussion 301-292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogel SN, Awomoyi AA, Rallabhandi P, Medvedev AE. Mutations in TLR4 signaling that lead to increased susceptibility to infection in humans: an overview. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11:333–339. doi: 10.1179/096805105X58724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoue K. Promoting effects of nanoparticles/materials on sensitive lung inflammatory diseases. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s12199-010-0177-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inoue K, Takano H. Aggravating impact of nanoparticles on immune-mediated pulmonary inflammation. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:382–390. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]