Abstract

The heavy metal ATPase (HMA) family plays an important role in transition metal transport in plants. However, this gene family has not been extensively studied in Populus trichocarpa. We identified 17 HMA genes in P. trichocarpa (PtHMAs), of which PtHMA1–PtHMA4 belonged to the zinc (Zn)/cobalt (Co)/cadmium (Cd)/lead (Pb) subgroup, and PtHMA5–PtHMA8 were members of the copper (Cu)/silver (Ag) subgroup. Most of the genes were localized to chromosomes I and III. Gene structure, gene chromosomal location, and synteny analyses of PtHMAs indicated that tandem and segmental duplications likely contributed to the expansion and evolution of the PtHMAs. Most of the HMA genes contained abiotic stress-related cis-elements. Tissue-specific expression of PtHMA genes showed that PtHMA1 and PtHMA4 had relatively high expression levels in the leaves, whereas Cu/Ag subgroup (PtHMA5.1- PtHMA8) genes were upregulated in the roots. High concentrations of Cu, Ag, Zn, Cd, Co, Pb, and Mn differentially regulated the expression of PtHMAs in various tissues. The preliminary results of the present study generated basic information on the HMA family of Populus that may serve as foundation for future functional studies.

Keywords: Populus, P1B-type ATPases, HMA gene, heavy metal stress, phytoremediation

Introduction

One of the negative effects of industrialization is heavy metal pollution, which is deleterious not only to the environment but also to human health. Heavy (transition) metals cause toxicity at the cellular level by binding to sulfhydryl groups in proteins and inhibiting enzyme activity or protein function. Exposure to heavy metals may also induce deficiencies in other essential ions by disrupting cellular transport processes and causing oxidative damage (Williams and Mills, 2005). Plants have evolved regulatory mechanisms on heavy metal ion toxicity tolerance and ensure an adequate supply of essential nutrients. Membrane transport proteins play an important role as scavengers of heavy metals. In recent years, progress in the development of genetic and molecular techniques has helped with in identification of various gene families that function in metal transportation (Williams and Mills, 2005).

The P1B-type ATPase, also known as the heavy metal ATPases (HMAs), which belongs to the large P-type ATPase family, plays an important role in transition metal transport in plants (Mills et al., 2003; Gravot et al., 2004; Hussain et al., 2004). It can selectively absorb and transport essential metal ions (Cu2+, Zn2+, and Co2+) for plant growth and development, as well as participate in the distribution of non-essential heavy metal ions (Cd2+ and Pb2+). The typical P1B-ATPase consists of approximately 6–8 transmembrane helices, a soluble nucleotide binding domain, phosphorylation domain, and a soluble actuator domain. The interactions of these three domains play an important part in the mechanism (Smith et al., 2014). In addition, both sides of the N-terminal and C-terminal metal binding sites comprise metal binding domains that interact with and bind specific metal ions (such as Cd2+/Pb2+). P1B-type ATPase is also located in this site, which is a heavy metal-associated regulatory domain as well (Williams and Mills, 2005; Arguello et al., 2007).

HMAs provides metal resistance, absorption, and transport. Based on metal substrate specificity, HMAs can be clustered into two major phylogenetic subclasses, namely, the Cu/Ag P1B-ATPase group and the Zn/Co/Cd/Pb P1B-ATPase group (Axelsen and Palmgren, 1998). The HMA proteins have been studied at the genomic scale in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice (Oryza sativa). There are eight and nine members of P1B-ATPase in A. thaliana and O. sativa, respectively (Williams and Mills, 2005). AtHMA1–4 in A. thaliana and OsHMA1–3 in O. sativa belong to the former group, whereas AtHMA5–8 and OsHMA4–9 belong to the latter group (Williams and Mills, 2005). The Arabidopsis disruption mutant of AtHMA1 is sensitive to high concentrations of Zn (Moreno et al., 2008). Overexpression of AtHMA3 induces Cd accumulation in plants, with a 2.5- and 2-fold higher in the roots and shoots, respectively (Morel et al., 2009). AtHMA4 knockout plants are more sensitive to excess Zn(II) and Cd(II), and accumulate Zn less in shoots and more in roots than wild-type plants (Verret et al., 2004; Mills et al., 2005). High Cu concentrations elevate the expression of OsHMA5 (Deng et al., 2013). Some members of P1B-type ATPases were identified in other plant species, including barley, wheat, Thlaspi caerulescens, and A. halleri (Deng et al., 2013).

Early phytoremediation studies have shown that Populus trichocarpa, a fast-growing tree species, could be a suitable candidate for the treatment of heavy metal-polluted soils (Cunningham, 1996). Poplars transpire large amounts of water, thereby reducing contaminants from soil and water (Zacchini et al., 2009). Because of this feature, Populus spp. has attracted the attention of researchers working on remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils. The completion of the P. trichocarpa genome sequence in 2006 presents an excellent opportunity to investigate the metal transporter families in this plant species (Tuskan et al., 2006). Although HMA genes have been extensively studied in various plants, including Arabidopsis, rice, and barley, investigations on the HMA gene family in Populus are limited. To compare the mechanisms on metal phytoremediation between woody and herbaceous plants that maintain different life cycles and considering the importance of the HMA gene family in plant responses to heavy metal stresses, we investigated HMA genes in Populus. In the present study, we performed a genome-wide analysis of the P. trichocarpa HMA gene family, its phylogenetic analysis, chromosomal distribution, and expressional analysis. We identified a total of 17 HMA genes in P. trichocarpa. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that the HMA genes in Populus were differentially regulated by excessive Cu, Ag, Zn, Cd, Co, Pb, and Mn stress. The results provide insights for future investigations into the roles of these candidate HMA genes in responds to metal stress in Populus.

Materials and methods

Identification of HMA genes in populus

We used Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) to query HMA genes in the P. trichocarpa genome. All Populus HMA genome sequences could be directly downloaded from Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/) and NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The downloaded HMA candidates sequences were analyzed manually using the SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) database to verify the presence of the HMA domain (Letunic et al., 2004). A. thaliana and O. sativa HMA subfamily sequences were downloaded from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR, http://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp, release 10.0) and Rice Information Resource (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/index.shtml), respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of the full-length protein sequences was performed using the ClustalX (version 1.83) program (Thompson et al., 1997) and manually adjusted using the BioEdit 7.1 software (Hall, 1999). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, with a bootstrap test performed using 1000 iterations in MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2007). Bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates was used to evaluate the significance of the nodes. Gene clusters referred to the homologs within the three species (P. trichocarpa, A. thaliana, and O. sativa) that were identified based on the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Chromosomal location and subcellular location of HMA genes

The chromosomal localization of all genes was determined and plotted with PopGenIE (http://www.popgenie.org/). Genes separated by =5 gene loci within a range of 100-kb distance were considered tandem duplicates (Hu et al., 2010). Identification of homologous chromosome segments resulting from whole-genome duplication events was conducted as described by Tuskan et al. (2006) WoLF PSORT (http://wolfpsort.org/) was used to predict the subcellular localization of the HMA proteins (Horton et al., 2007).

Exon-intron structure and motif analysis

The online software Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS; Guo et al., 2007) was used to generate the exon/intron organization of HMA genes by comparing the cDNAs to its corresponding genomic DNA sequences in Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/search.php). The Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elucidation (MEME) system (Version 4.9) was used to investigate conserved motifs for each HMA gene (Bailey et al., 2006).

Promoter cis-element identification and microarray analyses

Promoter sequences, located 2000 kb upstream of the translation start site, were searched using NCBI, and were analyzed in the Plant Care database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) (Lescot et al., 2002). To obtain the expression of each gene in different tissues and organ, we searched the microarray dates from PopGenIE v2.0 (http://popgenie.org/gp) in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database using the series accession number GSE6422.

Plant materials and treatment

Clonally propagated P. trichocarpa genotype Nisqually-1 was cultured in half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) at 23–25°C. Plants were exposed to the following: 100 μM CdCl2, 100 μM CuSO4,60 μM MnSO4, 750 μM Pb(NO3)2, 200 μM ZnSO4, and 1 mM AgNO3, and 50 μM CoCl2. Each treatment lasted for 0, 1, 3, and 10 h, and samples were collected at each time point. Three biological replicates were prepared for each stress treatment. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. Non-treated plants were used as control.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the roots, stems, and leaves using the CTAB method (Jaakola et al., 2001). Prior to cDNA synthesis, RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions to rule out DNA contamination. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Perfect Real Time; Takara, Dalian, China). Primer Premier 5 was used to design gene-specific primers for all HMA genes based on its corresponding CDS. BLAST was used to check each primer to determine its specificity for the respective gene, and was further confirmed by melting curve analysis of real-time PCR reactions. All primer sequences are presented in Table S1.

SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was used to perform qRT-PCR to determine the transcript levels of HMA genes in P. trichocarpa under different metal stresses. Reactions were prepared in a total volume of 20 μL that contained the following: 2 μL of template, 10 μL of 2 × SYBR Premix, 6 μL of ddH2O, and 1 μL of each specific primer, prepared to a final concentration of 10 μM. Three technical replicates were performed for each sample to ensure the accuracy of the results. The P. trichocarpa actin gene (GenBank Acc. No.: XM_002298674) was used as reference gene (An et al., 2011). A relative quantification method (2−ΔΔCT) was used to evaluate quantitative variation among replicates. The PCR conditions and relative gene expression calculations were as previously described (Zhang et al., 2013).

Results

Identification of HMA genes in Populus

We identified a total of 17 HMA genes (Table 1), of which PtHMA4(1), PtHMA4(2), PtHMA4(3), PtHMA4(4), PtHMA4(5) could be attributed to alternative splicing of mRNA with PtHMA4, which generates a variety of mature RNA transcripts that produce protein isoforms. The identified PtHMA genes encoded proteins that varied in length from 626 to 1228 amino acids (AA), and with an average of 928 AA. We used WoLF PSORT to predict the location of the proteins and noticed that most PtHMA genes were predicted as plasma membrane proteins, except PtHMA1 and PtHMA5.1, which were located in the cytoplasm (Table 1).

Table 1.

The HMA gene family in Populus trichocarpa.

| Gene name | Accession number | NCBI Locus ID | Length(AA) | Protein subcellular Localization prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtHMA1 | POPTR_0007s10480 | XM_002310080.2 | 833 | cytoa |

| PtHMA4 | POPTR_0006s07650 | XM_002327518.1 | 1228 | plas |

| PtHMA4(1) | 873 | |||

| PtHMA4(2) | 1126 | |||

| PtHMA4(3) | 1169 | |||

| PtHMA4(4) | 1170 | |||

| PtHMA4(5) | 1193 | |||

| PtHMA5.1 | POPTR_0003s12580 | XM_002303545.1 | 983 | cyto |

| PtHMA5.2 | POPTR_0001s09210 | XM_002299504.2 | 985 | plas |

| PtHMA5.3 | POPTR_0003s12570 | XM_002303544.2 | 987 | plas |

| PtHMA5.4 | POPTR_0001s05650 | XM_002299198.1 | 974 | plas |

| PtHMA5.5 | POPTR_0003s20380 | XM_006385962.1 | 626 | plas |

| PtHMA6.1 | POPTR_0001s21290 | XM_002299649.2 | 807 | plas |

| PtHMA6.2 | POPTR_0003s01850 | XM_002304058.2 | 808 | plas |

| PtHMA7.1 | POPTR_0001s15900 | XM_002326412.1 | 1010 | plas |

| PtHMA7.2 | POPTR_0003s07330 | XM_002303313.1 | 1008 | plas |

| PtHMA8 | POPTR_0018s08380 | XM_006371981.1 | 889 | plas |

plas, plasma membrane; cyto, cytoplasm.

Phylogenetic, gene structural, and conserved motif analyses of PtHMA genes

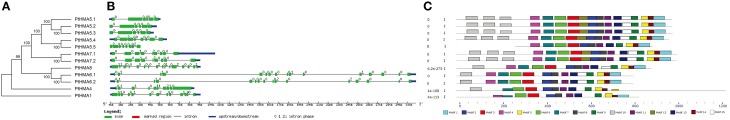

To examine the phylogenetic relationships among the Populus HMA domain proteins in Populus, an unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed from alignments of the full-length HMA sequences (Figure 1A). We classified 12 HMA genes into two subgroups, namely, Zn/Co/Cd/Pb (PtHMA1–4) and Cu/Ag (PtHMA5–8). Near 8000 pairs of paralogous genes are distributed in the Populus genome (Guo et al., 2009). By phylogenetic analysis, four paralogous pairs among the 12 Populus HMA genes were identified (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships, gene structure, and motif composition of HMA genes in P. trichocarpa. (A) Multiple alignments of 12 full-length amino acids of HMA genes were executed by ClustalX 1.83, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 5.0 using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. (B) Exon/intron structures. Exons and introns are represented by green boxes and black lines, respectively. (C) Schematic representation of the conserved motifs elucidated by MEME. Each motif is represented by a number in the colored box. The black lines represent the Non-conserved sequences.

A comparison of the exon/intron organization of the coding sequences of individual PtHMA genes showed that most closely related members shared similar exon/intron structures either according to the number of introns or exon length. These results were consistent with the characteristics defined in the above phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1A). The coding sequences of most of the HMA genes were disrupted by introns, with the number of introns ranging from 5 to 16. PtHMA8 exhibited the largest number of introns (16), followed by PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2 (15) and PtHMA1 (12). Other genes had less than 10 introns (Figure 1B).

Table S2 presents the conserved motifs that were shared among related proteins within the family and 15 distinct motifs (Table S2). The number of HMA motifs in Populus HMA proteins and the spacing of amino acids between adjacent HMA motifs varied, which was similar to that observed in Arabidopsis and rice HMA proteins. Most of the closely related members in the phylogenetic tree shared common motifs, and all HMA genes contained common motifs, except for motifs 1, 4, 10, 12, and 15 (Figure 1C). All HMA family members contained motif 10, except PtHMA1, thereby indicating that at least one motif was lost in this gene during its divergence from a common ancestor. Moreover, differences in gene organization and motif composition among related members suggested that these genes may be functionally divergent.

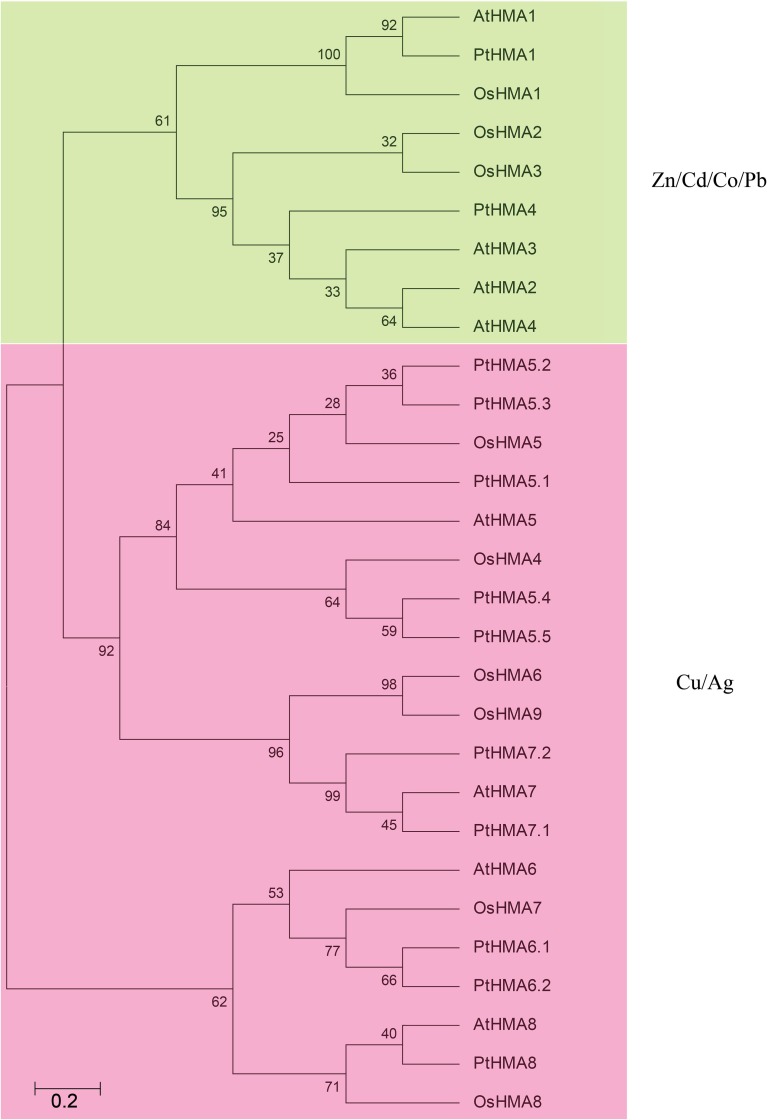

Comparative analysis of the HMA genes in Populus, Arabidopsis, and rice

We examined the phylogenetic relationship among the HMA domain proteins in Populus (12 genes), rice (9 genes), and Arabidopsis (8 genes) that were constructed from alignments of full-length HMA protein sequences (Figure 2). The tree topologies produced by the three algorithms were largely comparable, and there were only minor modifications at interior branches (data not shown). Therefore, we further analyzed only the NJ phylogenetic tree in the present study. The HMA gene family contains different numbers and types of HMAs. There are eight and nine members of P1B-ATPase in A. thaliana and rice, respectively (Williams and Mills, 2005). These were then further divided into two groups: Zn/Cd/Co/Pb and Cu/silver (Ag) transporters (Axelsen and Palmgren, 1998). AtHMA1–AtHMA4 and OsHMA1–OsHMA3 belonged to the Zn/Co/Cd/Pb subgroup, whereas AtHMA5–AtHMA8 and OsHMA4–OsHMA9 comprised the Cu/Ag subgroup (Williams and Mills, 2005). PtHMA1 and PtHMA4 belonged to the Zn/Co/Cd/Pb subgroup, whereas the rest of the genes were classified into the Cu/Ag subgroup (Figure 2). The number of genes in the Populus (10 genes) Cu/Ag subgroup was significantly higher than that in rice (6 genes) and Arabidopsis (4 genes).

Figure 2.

All HMA proteins of P. trichocarpa (12), A. thaliana (8), and O. sativa (9) were divided into two distinct subfamilies. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 5.0 using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Green represents the Zn/Cd/Co/Pb subgroup; pink indicates the Cu/Ag subgroup.

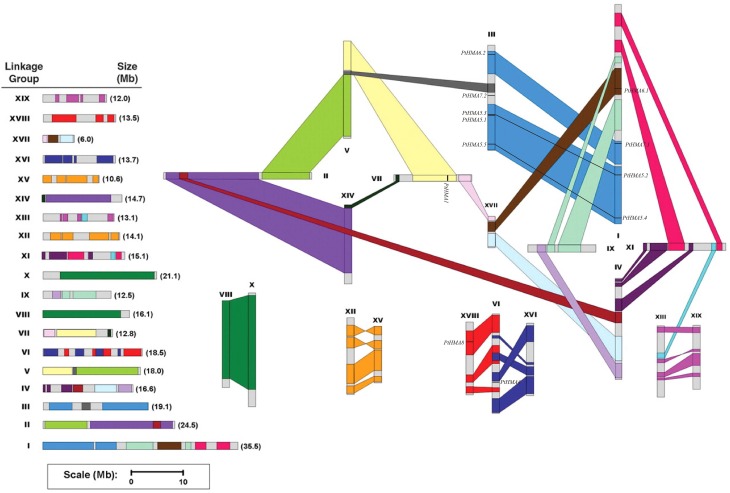

Chromosomal location and gene duplication of Populus HMAs

In silico mapping of gene loci showed that all 12 Populus HMA genes were physically located on 19 linkage groups (LG). A previous study revealed that the Populus genome has undergone genome-wide duplications, followed by multiple segmental duplications, tandem duplications, and transposition events (Hu et al., 2012). Populus HMA genes were differentially expressed in various tissues (Figure 4). The PtHMA genes were located on chromosomes I, III, VI, VII, and XVII. Chromosome III harbored the highest number of HMA genes (five), followed by chromosome I (four). Only one HMA gene was detected on each of chromosomes VI, VII, and XVII (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chromosomal location of Populus HMA genes. A total of 12 HMA genes are mapped to the 19 linkage groups (LG). A schematic view of chromosome reorganization by recent whole-genome duplication in Populus is shown. Segmentally duplicated homologous blocks are indicated with the same color. The scale represents megabases (Mb). The LG numbers are indicated at the top of each bar.

The segmental duplication associated with the salicoid duplication event that occurred 65 million years ago largely contributed to the expansion of several multi-gene families (Kalluri et al., 2007; Barakat et al., 2009, 2011; Wilkins et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010). We used the duplicated blocks established in a previous study (Tuskan et al., 2006) to confirm the possible relationship between HMA genes and potential segmental duplications. The distribution of HMA genes relative to the corresponding duplicate blocks is illustrated in Figure 3. In this study, of the 12 Populus HMA genes, 10 were located in duplicated regions and two were located outside duplicated blocks. Among these 10 genes, four were preferentially retained duplicates that were located in both duplicated regions, whereas the others were only in one of the blocks and lacked duplicates in the corresponding block. These results indicated that duplication events and tandem repeats contributed to the expansion of the HMA gene family in the Populus genome.

Promoter cis-elements analysis

Phytohormones such as salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET), and abscisic acid (ABA) enable plants to adapt to abiotic stresses (Fujita et al., 2006; Santner and Estelle, 2009). We identified putative cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (Table 2) on the basis of the obtained promoter sequences (2000 bp). The PtHMA gene family promoter sequences showed several cis-elements that were related to phytohormones and environmental stress signal responsiveness. Most of the 12 HMA genes contained cis-elements such as ABA responsive (ABREs and AREs), heat stress responsive (HSEs), MYB binding site involved in drought-inducibility (MBS), and defense and stress responsive TC-rich repeat elements. PtHMA1, PtHMA4, PtHMA5.1, PtHMA5.2, PtHMA6.2, PtHMA7.1, and PtHMA8 contained the cis-element TCA-element, which is involved in salicylic acid responsiveness. SA appears to be an effective therapeutic agent in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Rivas-San Vicente and Plasencia, 2011). It was also reported that SA induced adaptability to Cd, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Mn toxicity (Mostofa and Fujita, 2013). The CGTCA-motif or TGACG-motif involved in MeJA-responsiveness was identified in seven genes (Table 2). Moreover, PtHMA1 and 5.4 contained the cis-acting regulatory element, as-2-box, and as1, which are involved in shoot-specific and root-specific expression, respectively. PtHMA5.5 contained a CAT-box that is related to meristem expression.

Table 2.

The cis-elements of HMA gene promoter in P. trichocarpa that are related to stress.

| Gene name | cis-elements related to abiotic stress |

|---|---|

| PtHMA1 | TGACG-motif |

| PtHMA4 | |

| PtHMA5.1 | |

| PtHMA5.2 | ERE CCAAT-box |

| PtHMA5.3 | ERE |

| PtHMA5.4 | ERE |

| PtHMA5.5 | ERE CAT-box |

| PtHMA6.1 | |

| PtHMA6.2 | |

| PtHMA7.1 | |

| PtHMA7.2 | ERE |

| PtHMA8 | ERE |

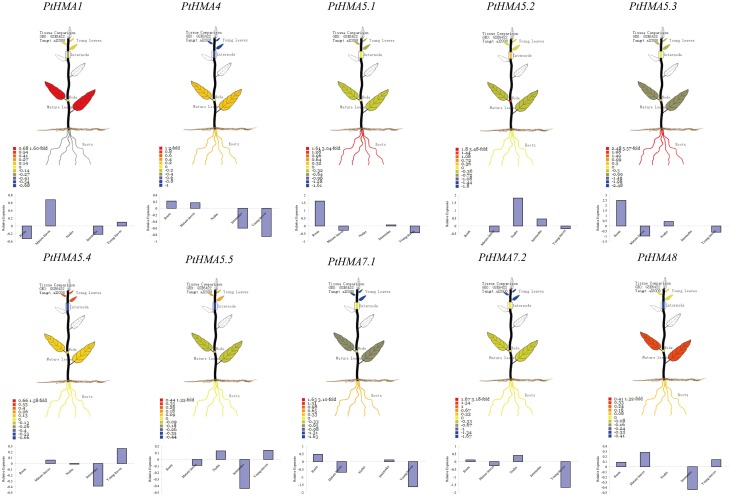

Tissue-specific expression profile in PopGenIE v2.0

The expression profiles of 10 HMA genes from the Affymetrix (GSE6422) microarray data showed specific expression patterns in different tissues (Figure 4). Two HMA genes (PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2) did not have corresponding microarray sequences in the database, which suggested that the two genes were pseudogenes. Alternatively, the two genes showed a low level of transcript abundance or had special temporal and spatial expression patterns that were not examined in the libraries. The microarray data showed high expression levels of PtHMA1 and PtHMA4 in leaves. We also observed high expression levels of PtHMA4 in the roots. Cu/Ag subgroup members (PtHMA5.1–PtHMA8) also showed higher expression levels in the roots than in other tissues. PtHMA5.4 and PtHMA5.5 had higher expression levels in young leaves than in other tissues. In addition, in promoters of PtHMA5.4 and PtHMA5.5, the genes were related to meristem expression.

Figure 4.

Organ-specific expressions of PtHMA genes in mature-leaves, young-leaves, roots, nodes, and internodes. The visual images were searched from PopGenIE v2.0. Each gene is indicated in every graph.

Expression of HMA genes under different heavy metal stresses

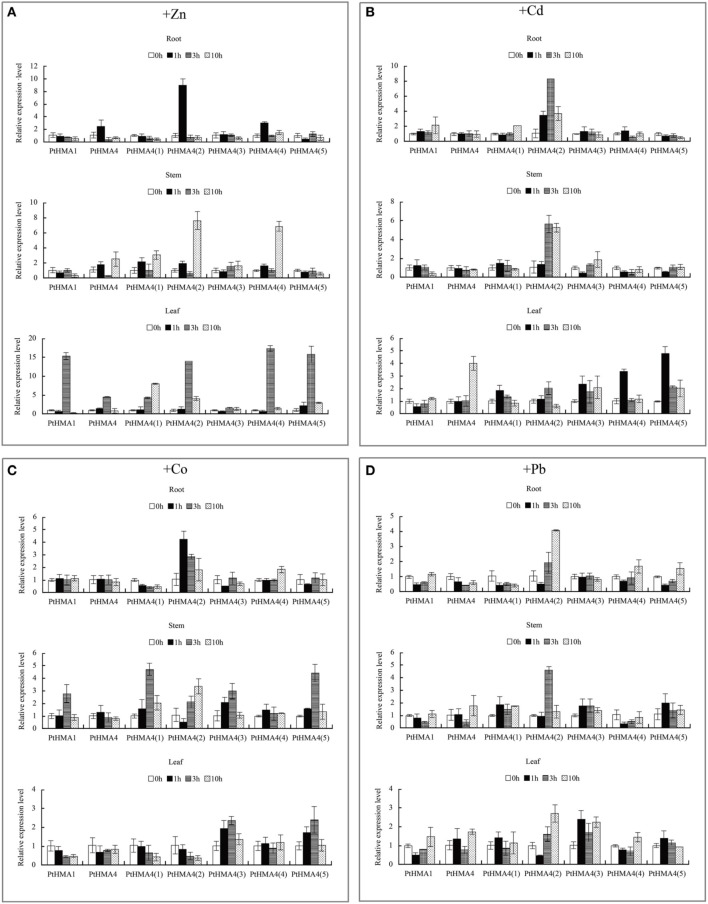

We studied the expression profiles of PtHMA genes in P. trichocarpa under heavy metal stress (Figure 5). The genes PtHMA1 and PtHMA4 and its five alternatively spliced genes (Zn/Co/Cd/Pb subgroup) were exposed to Zn, Cd, Co, and Pb stresses. Under Cd stress, the expression of PtHMA1 gradually increased in the roots compared to the non-treated samples, the expression level increased in the stem after 1 h of treatment, and the expression level of PtHMA1 in the leaves gradually increased with treatment time (Figure 5B). Therefore, Populus HMA1 might not only be involved in Zn transport, but also in Cd transport from the roots to the leaves. The expression level of the PtHMA4(2) gene was higher compared to that of the other alternatively spliced genes [PtHMA4(1), PtHMA4(3), PtHMA4(4), and PtHMA4(5)] under excess Zn, Cd, Co, and Pb stresses. In the 200 μM ZnSO4 treatment, PtHMA4(2) was upregulated at 1 h in the roots and 10 h in the stems compared to that observed in the roots and leaves, and the expression in the roots peaked at 3 and 10 h of Zn treatment (Figure 5A). The transcription levels of PtHMA4(2) were higher in the roots and stems than that in the leaves with Cd treatment at all-time points. Moreover, PtHMA4(2) was upregulated in the roots, stems, and leaves after exposure to excessive Pb (Figure 5D), and in the roots and leaves with exposure to high amounts of Co (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of the PtHMA genes under heavy metal conditions. QRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression patterns of 7 PtHMA genes in the roots, stems, and leaves under excessive amounts of Zn (A), Cd (B), Co (C), and Pb (D). X-axis represents different genes. The y-axis represents relative gene expression levels normalized to the Populus reference gene, actin. Standard deviations were derived from three replicates of each experiment.

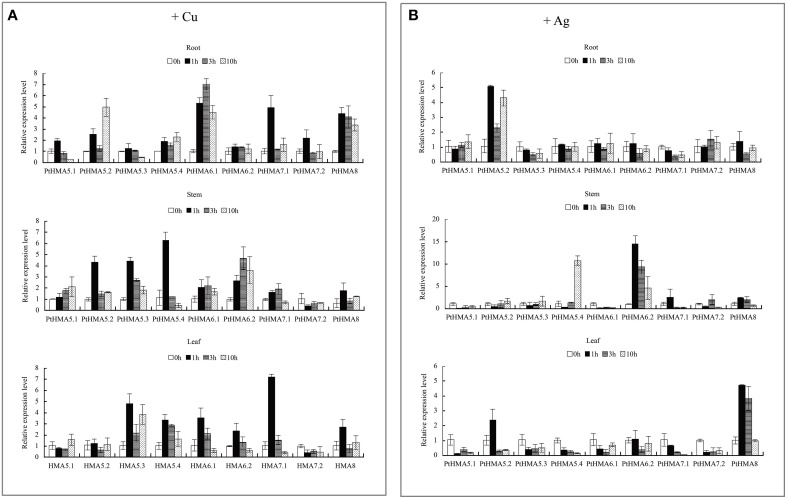

We further evaluated the expression patterns of PtHMA5–PtHMA8 of the Cu/Ag subfamily. The number of genes for PtHMA5 (5 genes), PtHMA6 (2 genes), PtHMA7 (2 genes) was higher than those of its alternatively spliced Arabidopsis counterparts. We also examined the expression of nine candidate genes subjected to excessive Cu and Ag treatments (Figure 6). The genes PtHMA5.2, 5.4, 6.1, 7.1, and 8 were unregulated in response to Cu treatment, whereas PtHMA5.1 and 5.3 were downregulated in the roots (Figure 6A). However, the expression of five genes (i.e., PtHMA5.2, 5.4, 6.1, 7.1, and 8) in the roots remained unaffected with Cu treatment (Figure 6A). On the other hand, PtHMA5.2, 5.3, and 5.4 were considerably upregulated in poplar stems after exposure to Cu for 1 h, whereas PtHMA 6.2 was upregulated at all time points, with the highest expression detected after 3 h. In leaves, PtHMA5.3, 5.4, 6.1, 6.2, and 7.1 showed considerably high expression levels after 1 h of exposure to excessive levels of Cu (Figure 6A). The gene expression patterns of the four Populus PtHMA5 genes were divided into two groups based on the time point when the highest transcript levels were observed in different tissues and organs (Figure 6A). One group (PtHMA5.1 and PtHMA5.3) accumulated the highest transcripts in the roots at 1 h after Cu treatment, whereas that of the other groups, PtHMA5.2 and PtHMA5.4, exhibited two peaks, namely, at 1 and 10 h, of Cu treatment. The expression level of PtHMA5.1 in the stems and leaves gradually increased with treatment time. The highest transcription levels for PtHMA5.2, 5.3, and 5.4 were observed in the roots at 3 and 10 h of excessive Cu treatment. PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2 were highly expressed in the roots but were also expressed in stems and leaves. These results suggest that PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2 play a role in Cu transport during plant growth and development. The expression of PtHMA7.1, PtHMA7.2, and PtHMA8 was upregulated in the roots, stems, and leaves, and PtHMA7.1 was considerably upregulated in the leaves (Figure 6A). The expression level of PtHMA8 in the roots was higher than that in the stems and leaves. In the roots, PtHMA5.1, 5.2, and 7.2 were upregulated in response to Ag treatment, whereas the other genes remained unaffected at all-time points. In the stems, PtHMA5.4, 6.2, and 8 showed a significant increase in transcript levels at 10 h, and 6.2 presented a higher expression level at all-time points compared to that of the control (Figure 6B). Ag treatment increased the expression level of the PtHMA5.2, PtHMA5.4, PtHMA6.2, and PtHMA8 transcripts compared to the five other HMA genes (PtHMA5.1, PtHMA5.3, PtHMA6.1, PtHMA7.1, and PtHMA7.2). The expression of PtHMA5.4 and PtHMA6.2 in the stems peaked at 10 and 1 h after excess Ag treatment, respectively. PtHMA8 was expressed in the entire plantlet, whereas its expression level was higher in the leaves than in the stems and roots under excess Ag stress. In contrast, PtHMA6.2 and PtHMA8 had the highest levels of transcript abundance in the stems and leaves relative to those of the other HMA genes with Ag treatment.

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression patterns of nine PtHMA genes in the roots, stems, and leaves under excessive amounts of Cu (A) and Ag (B). X-axis represents different genes. The y-axis represents relative gene expression levels normalized to the Populus reference gene, actin. Standard deviations were derived from three replicates of each experiment.

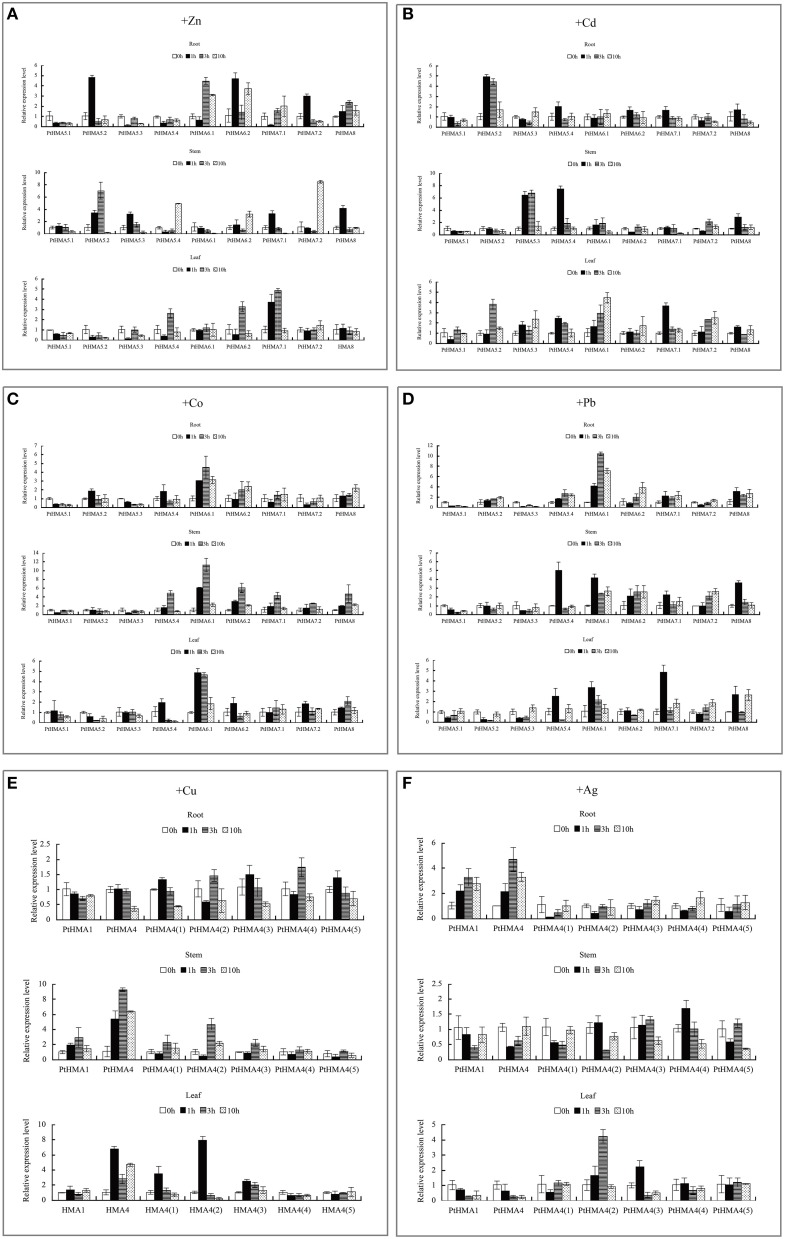

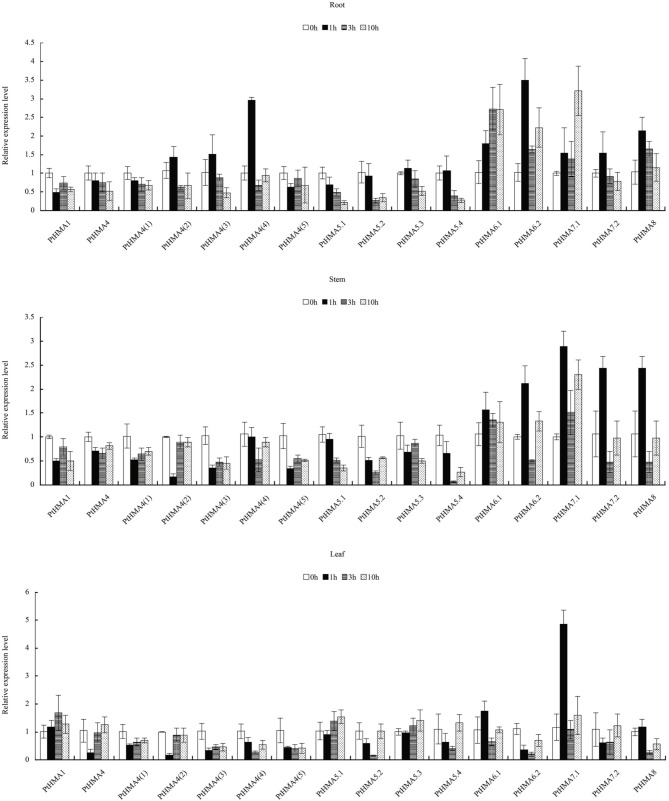

Our qRT-PCR data further showed that PtHMA5–PtHMA8 might have also been induced by Zn, Cd, Co, or Pb. Of these genes, two homologous genes (PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2) exhibited particularly high transcript accumulations in the roots, stems, and leaves after exposure to excessive amounts of Zn, Co and Pb, especially the roots (Figure 7). The expression level of PtHMA5.2, PtHMA5.3, PtHMA5.4, PtHMA6.1, PtHMA7.1, and PtHMA7.2 increased in different tissues under excessive Cd stress. The expression of PtHMA6.1 was higher in the leaves than in the roots and stems (Figure 7B). The PtHMA1–PtHMA4 phylogenetic cluster with the Zn/Cd/Co/Pb subclass of HMAs (Figure 2) was possibly induced by Cu or Ag. For example, PtHMA4 and PtHMA4(2) were mainly expressed in the stems under excessive Cu stress (Figure 7E). Also, PtHMA1 and PtHMA4 were upregulated in the roots compared to that observed in the stems and leaves after excessive Ag stress (Figure 7F). Mn is an important micronutrient that is required in various stages of plant growth and development. Five genes (PtHMA6.1, PtHMA6.2, PtHMA7.1, PtHMA7.2, and PtHMA8) showed higher transcript levels in the roots, stems, and leaves under Mn stress, with peak expression at 1 and 10 h of excess Mn treatment (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

qRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression patterns of nine PtHMA genes in the roots, stems, and leaves under excessive amounts of Zn (A), Cd (B), Co (C), and Pb (D), and seven PtHMA genes in the roots, stems, and leaves under excessive amounts of Cu (E) and Ag (F). X-axis represents different genes. The y-axis represents relative gene expression levels normalized to the Populus reference gene, actin. Standard deviations were derived from three replicates of each experiment.

Figure 8.

qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression patterns of 16 PtHMA genes in the roots, stems, and leaves under excessive Mn stress. X-axis represents different genes. The y-axis represents relative gene expression levels normalized to the Populus reference gene, actin. Standard deviations were derived from three replicates of each experiment.

Discussion

The HMA gene family in Populus

In the present study, we identified 12 full-length HMA genes and five alternatively spliced genes of PtHMA4 in the P. trichocarpa genome, each of which contains at least one HMA motif. The lengths of these sequences significantly varied, implying a high degree of complexity among the HMA genes. Furthermore, WoLF PSORT analyses allowed us to putatively localize the genes. However, experimental validation may be required for a more accurate localization. Preliminary analysis of the HMA gene family was performed in the plant models, Arabidopsis and rice (Williams and Mills, 2005; Takahashi et al., 2012). These studies revealed that AtHMA1, AtHMA6, and AtHMA8 were located in the chloroplast; AtHMA2, AtHMA4, and AtHMA5 were located in plasma membrane; and AtHMA3 and AtHMA7 were in the vacuole and Golgi, respectively (Williams and Mills, 2005). The present study showed that most of the HMA genes were predicted as plasma membrane proteins, except PtHMA1 and PtHMA5.1. PtHMA1 was located in the cytoplasm, though it was placed in the same group as PtHMA4 (Zn/Cd/Co/Pb). PtHMA5.1 was also located in the cytoplasm, which differed from the other members of PtHMA5 (i.e., PtHMA5.2–PtHMA5.5). These results indicated that the same phylogenetic grouping based on sequence similarity did not necessarily correspond to the same subcellular localization. Therefore, homologous genes may show differences in gene function and signal transduction. Although our preliminary prediction showed that PtHMA1 and PtHMA5.1 were located in the cytoplasm, we could not determine the specific organelle which the genes were associated with. Further studies may help to determine the exact location of these genes. However, subcellular localization of these genes in Populus might change with varying metal supply, as seen in the mammalian Wilson's disease protein, ATP7B, which moves from the Golgi to the plasma membrane at higher metal concentrations (Petris et al., 1996). We speculate that the localization of HMA family proteins changes with differences in metal supply and utilize specific mechanisms with various metal stresses.

It has been reported that exon-intron increase or decrease can be caused by the integration and realignment of gene fragments (Xu et al., 2012). Therefore, structural gene variation plays a major role in the evolution of gene families (Xu et al., 2012). In the evolutionary history of Populus, members of the HMA gene family underwent rigorous selection. The structure of Populus HMA genes is well conserved, and these genes have different numbers of exons. Although PtHMA5–8 belonged to the same phylogenetic group (group Zn/Cd/Co/Pb), their number of exons varied. PtHMA6.1 and PtHMA6.2 had more exons than the others, which in turn may be expressed in specific tissues.

Comparative analysis of the HMA genes in Populus, Arabidopsis, and rice

In Arabidopsis, the Cu subgroup has three domains, E1-E2 ATPase domains (PF00122), a heavy metal-associated domain (PF00403), and a haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase (PF00702). The Zn subgroup has two domains, namely, the E1-E2 ATPase and haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase (Table S3). Unlike Arabidopsis, the HMAs of P. trichocarpa has similar domains. However, phylogenetic analysis showed that PtHMA5.5 had only an E1-E2 ATPase and a haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase domain compared to the other members of its subgroup. Our analysis also revealed that the number of Populus, Arabidopsis, and rice HMA genes varied in most subfamilies. For example, Arabidopsis and rice just have one of each of the HMA5, HMA6, HMA7 genes. However, Populus has five members of HMA5 and two members of HMA6 and HMA7. Populus lacks HMA2 and HMA3, but alternative splicing of PtHMA4 may occur and compensate for the two missing genes. Therefore, the present study provides a platform for future studies on the role of HMA genes in Populus.

Chromosomal location and gene duplication

Tuskan et al. (2006) suggested that the Populus genome underwent at least three rounds of genome-wide duplication, followed by multiple segmental duplication, tandem duplication, and transposition events such as retroposition and replicative transposition. Gene duplication events, including tandem and segmental duplication, play an important role in genomic expansions and realignments (Vision et al., 2000; Kumar et al., 2011). In the present study, 5/6 of the Populus HMA genes were located in duplicated regions, whereas only two genes were located outside the duplicated blocks. These results suggest that dynamic rearrangements might have occurred following the segmental duplication, which led to the loss of some genes. These findings also showed that PtHMA5.2 and PtHMA5.3, and PtHMA5.4 and PtHMA5.5 belonged to the same branch of the phylogenetic tree and were present in homologous regions of chromosomes I and III, respectively (Figure 3). This finding might explain the homology of the two genes. The tandem duplications might have impacted the expansion of the HMA gene family. Our results also showed that only one pair (PtHMA5.1/5.3) of the HMA genes underwent tandem duplication, as indicated by the >90% similarity in amino acid sequence. In comparison, two segmental duplications (PtHMA5.2/5.3 and PtHMA5.4/5.5) were identified. These results corroborate the findings of previous studies involving other gene families (Kalluri et al., 2007).

Transcript profiles of HMA genes in Populus

Plant metal homeostasis must be tightly regulated to ensure sufficient micronutrient (e.g., Zn, Cu, and Fe) supply to different organs, and to prevent non-essential metals (e.g., Cd and Pb) to reach toxic levels that may result in deleterious effects (Hall, 2002). Metal transporters play important roles in various aspects of essential and toxic metal distribution in plants. All members of HMAs in A. thaliana are functionally characterized (Deng et al., 2013). AtHMA1 and OsHMA1 are involved in Zn transport (Kim et al., 2009). AtHMA1 transports Zn, Cu, and Ca (Williams and Mills, 2005; Seigneurin-Berny et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2009). However, the present study did not indicate transcript accumulation of PtHMA1 under excessive Cu stress. Our data showed that the expression patterns of PtHMA1 and AtHMA1 were not similar. The HMA1 in Populus not only transported Zn and Cu but also Cd from the roots to the leaves. AtHMA4 is induced by Cd and Zn and is expressed in tissues surrounding the vascular vessels of the root vascular (Mills et al., 2003). In this study, in addition to Cd and Zn, PtHMA4(2) was also induced by Pb and Co. The transcription levels of PtHMA4(2) were almost unregulated in the roots, stems, and leaves (Figure 5). The above results indicated differential expression patterns for various PtHMAs in the roots, stems, and leaves, thus confirming tissue-specific expression. These findings may have significant implications in Populus. AtHMA5 is involved in the Cu translocation from the roots to the shoots or Cu detoxification of roots (Kobayashi et al., 2008). AtHMA6, AtHMA7, and AtHMA8 also play an important role in transport Cu (Woeste and Kieber, 2000; Shikanai et al., 2003; Abdel-Ghany et al., 2005; Catty et al., 2011). OsHMA5 is involved in loading Cu to the xylem of the roots and other organs (Deng et al., 2013). The results of the present study suggested that the role of PtHMA5 may differ from that of AtHMA5 and OsHMA5. AtHMA5 is involved in Cu detoxification, whereas OsHMA5 is responsible for xylem loading of Cu. However, PtHMA5 plays an important role in Ag detoxification in addition to Cu detoxification. PtHMA6.1, PtHMA6.2, PtHMA7.1, PtHMA7.2, and PtHMA8 are similar to their homologs in Arabidopsis and function in transporting or detoxifying Cu. PtHMA6.2 and PtHMA8 had higher transcription levels under Ag stress. PtHMA6.1, PtHMA6.2, PtHMA7.1, PtHMA7.2, and PtHMA8 were induced by Mn in the roots, stems, and leaves, suggesting that PtHMA genes help in scavenging excess Ag and Mn. The considerable differences in expression among PtHMA genes suggest that these genes perform varying physiological and biochemical functions to adapt to complicated challenges.

Metal transporters play important roles in various aspects of essential and toxic metal distribution in plants. Moreover, under different metal stress, the expression of PtHMAs varied in the roots, stems, and leaves, thereby confirming tissue-specific expression. In summary, the present study provides a theoretical basis to select metal-specific genes for related functional validation. Expression studies of PtHMA genes suggest their special roles during the plant growth and developmental stages. Their functions are similar to that in rice or Arabidopsis, although more complicated. The results of the present study led to a better understanding of the Populus phenotype and help to lay out the first step toward engineering a hyper accumulating Populus phenotype that may be utilized in phytoremediation. However, the specific functions of the most PtHMA genes remain unknown. Further experiments, such as Western blotting should be carried out to demonstrate that those HMA genes accounting for the responses to metal stress are real. Also, ectopic expression of PtHMA genes in Arabidopsis or other plant species is necessary to investigate heavy metal accumulation or tolerance phenotypes of the transgenic plants in response to heavy metal treatments. It would improve on the results of this study.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: DL, CL. Performed the experiments: DL, HZ. Analyzed the data: DL, XH, XX, and CL. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: DL, QL, ZW, HW, HL, MW, ZW, and CL. Wrote the paper: DL, CL. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant number 2572015EA05) and the Innovation Project of State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding (Northeast Forestry University; Grant number 2013A04) supported this study.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.01149

Phylogenetic tree of the HMA protein families in P. trichocarpa was constructed based on the alignments of the full-length HMA protein sequences. The tree was generated using the MEGA5 program with the neighbor-joining method. For statistical reliability, bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates.

The primers of PtHMA genes employed in qRT-PCR analysis. F represents the forward primer, whereas R represents the reverse primer.

Motif sequences of the HMA genes identified in Populus trichocarpa.

Domains of the HMA genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and P. trichocarpa.

References

- Abdel-Ghany S. E., Müller-Moulé P., Niyogi K. K., Pilon M., Shikanai T. (2005). Two P-type ATPases are required for copper delivery in Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplasts. Plant Cell 17, 1233–1251. 10.1105/tpc.104.030452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An X. M., Ye M. X., Wang D. M., Wang Z. L., Cao G. L., Zheng H. Q., et al. (2011). Ectopic expression of a poplar APETALA3-like gene in tobacco causes early flowering and fast growth. Biotechnol. Lett. 33, 1239–1247. 10.1007/s10529-011-0545-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguello J. M., Eren E., Gonzalez-Guerrero M. (2007). The structure and function of heavy metal transport P1B-ATPases. Biometals 20, 233–248. 10.1007/s10534-006-9055-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen K. B., Palmgren M. G. (1998). Evolution of substrate specificities in the P-type ATPase superfamily. J. Mol. Evol. 46, 84–101. 10.1007/PL00006286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W. W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W369–W373. 10.1093/nar/gkl198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat A., Bagniewska-Zadworna A., Choi A., Plakkat U., Diloreto D. S., Yellanki P., et al. (2009). The cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene family in Populus: phylogeny, organization, and expression. BMC Plant Biol. 9:26. 10.1186/1471-2229-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat A., Choi A., Yassin N. B., Park J. S., Sun Z., Carlson J. E. (2011). Comparative genomics and evolutionary analyses of the O-methyltransferase gene family in Populus. Gene 479, 37–46. 10.1016/j.gene.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catty P., Boutigny S., Miras R., Joyard J., Rolland N., Seigneurin-Berny D. (2011). Biochemical characterization of AtHMA6/PAA1, a chloroplast envelope Cu(I)-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36188–36197. 10.1074/jbc.M111.241034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S. D. (1996). Promises and prospects of phytoremediation. Plant Physiol. 110, 715–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng F., Yamaji N., Xia J., Ma J. F. (2013). A member of the heavy metal P-type ATPase OsHMA5 is involved in xylem loading of copper in rice. Plant Physiol. 163, 1353–1362. 10.1104/pp.113.226225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Fujita Y., Noutoshi Y., Takahashi F., Narusaka Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2006). Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 436–442. 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravot A., Lieutaud A., Verret F., Auroy P., Vavasseur A., Richaud P. (2004). AtHMA3, a plant P1B-ATPase, functions as a Cd/Pb transporter in yeast. FEBS Lett. 561, 22–28. 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00072-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A. Y., Zhu Q. H., Chen X., Luo J. C. (2007). GSDS: a gene structure display server. Yi Chuan 29, 1023–1026. 10.1360/yc-007-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. H., Yu Y. P., Wang D., Wu C. A., Yang G. D., Huang J. G., et al. (2009). GhZFP1, a novel CCCH-type zinc finger protein from cotton, enhances salt stress tolerance and fungal disease resistance in transgenic tobacco by interacting with GZIRD21A and GZIPR5. New Phytol. 183, 62–75. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02838.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. L. (2002). Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1–11. 10.1093/jexbot/53.366.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT, in Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, Vol. 41 (Oxford University Press; ), 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Park K. J., Obayashi T., Fujita N., Harada H., Adams-Collier C. J., et al. (2007). WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587. 10.1093/nar/gkm259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Chi X., Chai G., Kong Y., He G., Wang X., et al. (2012). Genome-wide identification, evolutionary expansion, and expression profile of homeodomain-leucine zipper gene family in poplar (Populus trichocarpa). PLoS ONE 7:e31149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Qi G., Kong Y., Kong D., Gao Q., Zhou G. (2010). Comprehensive analysis of NAC domain transcription factor gene family in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 10:145. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain D., Haydon M. J., Wang Y., Wong E., Sherson S. M., Young J., et al. (2004). P-type ATPase heavy metal transporters with roles in essential zinc homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 1327–1339. 10.1105/tpc.020487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola L., Pirttilä A. M., Halonen M., Hohtola A. (2001). Isolation of high quality RNA from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) fruit. Mol. Biotechnol. 19, 201–203. 10.1385/MB:19:2:201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri U. C., Difazio S. P., Brunner A. M., Tuskan G. A. (2007). Genome-wide analysis of Aux/IAA and ARF gene families in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 7:59. 10.1186/1471-2229-7-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Y., Choi H., Segami S., Cho H. T., Martinoia E., Maeshima M., et al. (2009). AtHMA1 contributes to the detoxification of excess Zn(II) in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 58, 737–753. 10.1111/j.1365-313XX.2009.03818.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Kuroda K., Kimura K., Southron-Francis J. L., Furuzawa A., Kimura K., et al. (2008). Amino acid polymorphisms in strictly conserved domains of a P-type ATPase HMA5 are involved in the mechanism of copper tolerance variation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 148, 969–980. 10.1104/pp.108.119933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Tyagi A. K., Sharma A. K. (2011). Genome-wide analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family from tomato and analysis of their role in flower and fruit development. Mol. Genet. Genom. 285, 245–260. 10.1007/s00438-011-0602-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M., Dehais P., Thijs G., Marchal K., Moreau Y., Van De Peer Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Copley R. R., Schmidt S., Ciccarelli F. D., Doerks T., Schultz J., et al. (2004). SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D142–D144. 10.1093/nar/gkh088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R. F., Francini A., Ferreira Da Rocha P. S., Baccarini P. J., Aylett M., Krijger G. C., et al. (2005). The plant P1B-type ATPase AtHMA4 transports Zn and Cd and plays a role in detoxification of transition metals supplied at elevated levels. FEBS Lett. 579, 783–791. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R. F., Krijger G. C., Baccarini P. J., Hall J. L., Williams L. E. (2003). Functional expression of AtHMA4, a P1B-type ATPase of the Zn/Co/Cd/Pb subclass. Plant J. 35, 164–176. 10.1046/j.1365-313XX.2003.01790.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel M., Crouzet J., Gravot A., Auroy P., Leonhardt N., Vavasseur A., et al. (2009). AtHMA3, a P1B-ATPase allowing Cd/Zn/Co/Pb vacuolar storage in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149, 894–904. 10.1104/pp.108.130294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno I., Norambuena L., Maturana D., Toro M., Vergara C., Orellana A., et al. (2008). AtHMA1 is a thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+/heavy metal pump. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9633–9641. 10.1074/jbc.M800736200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofa M. G., Fujita M. (2013). Salicylic acid alleviates copper toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings by up-regulating antioxidative and glyoxalase systems. Ecotoxicology 22, 959–973. 10.1007/s10646-013-1073-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petris M. J., Mercer J. F., Culvenor J. G., Lockhart P., Gleeson P. A., Camakaris J. (1996). Ligand-regulated transport of the Menkes copper P-type ATPase efflux pump from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane: a novel mechanism of regulated trafficking. EMBO J. 15, 6084–6095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-San Vicente M., Plasencia J. (2011). Salicylic acid beyond defence: its role in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 3321–3338. 10.1093/jxb/err031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santner A., Estelle M. (2009). Recent advances and emerging trends in plant hormone signalling. Nature 459, 1071–1078. 10.1038/nature08122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneurin-Berny D., Gravot A., Auroy P., Mazard C., Kraut A., Finazzi G., et al. (2006). HMA1, a new Cu-ATPase of the chloroplast envelope, is essential for growth under adverse light conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2882–2892. 10.1074/jbc.M508333200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikanai T., Müller-Moulé P., Munekage Y., Niyogi K. K., Pilon M. (2003). PAA1, a P-type ATPase of Arabidopsis, functions in copper transport in chloroplasts. Plant Cell 15, 1333–1346. 10.1105/tpc.011817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. T., Smith K. P., Rosenzweig A. C. (2014). Diversity of the metal-transporting P1B-type ATPases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 19, 947–960. 10.1007/s00775-014-1129-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Bashir K., Ishimaru Y., Nishizawa N. K., Nakanishi H. (2012). The role of heavy-metal ATPases, HMAs, in zinc and cadmium transport in rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 1605–1607. 10.4161/psb.22454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. (1997). The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan G. A., Difazio S., Jansson S., Bohlmann J., Grigoriev I., Hellsten U., et al. (2006). The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604. 10.1126/science.1128691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret F., Gravot A., Auroy P., Leonhardt N., David P., Nussaume L., et al. (2004). Overexpression of AtHMA4 enhances root-to-shoot translocation of zinc and cadmium and plant metal tolerance. FEBS Lett. 576, 306–312. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision T. J., Brown D. G., Tanksley S. D. (2000). The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 290, 2114–2117. 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins O., Nahal H., Foong J., Provart N. J., Campbell M. M. (2009). Expansion and diversification of the Populus R2R3-MYB family of transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 149, 981–993. 10.1104/pp.108.132795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. E., Mills R. F. (2005). P1B-ATPases-an ancient family of transition metal pumps with diverse functions in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 491–502. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woeste K. E., Kieber J. J. (2000). A strong loss-of-function mutation in RAN1 results in constitutive activation of the ethylene response pathway as well as a rosette-lethal phenotype. Plant Cell 12, 443–455. 10.1105/tpc.12.3.443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Guo C., Shan H., Kong H. (2012). Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1187–1192. 10.1073/pnas.1109047109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchini M., Pietrini F., Mugnozza G. S., Iori V., Pietrosanti L., Massacci A. (2009). Metal tolerance, accumulation and translocation in poplar and willow clones treated with cadmium in hydroponics. Water Air Soil Poll. 197, 23–34. 10.1007/s11270-008-9788-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Z., Yang J. L., Chen Y. L., Mao X. L., Wang Z. C., Li C. H. (2013). Identification and expression analysis of the heat shock transcription factor (HSF) gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Omics 6, 415–424. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree of the HMA protein families in P. trichocarpa was constructed based on the alignments of the full-length HMA protein sequences. The tree was generated using the MEGA5 program with the neighbor-joining method. For statistical reliability, bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates.

The primers of PtHMA genes employed in qRT-PCR analysis. F represents the forward primer, whereas R represents the reverse primer.

Motif sequences of the HMA genes identified in Populus trichocarpa.

Domains of the HMA genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and P. trichocarpa.