Abstract

Importance

Few studies have evaluated the relationship between influenza vaccination and pneumonia, a serious complication of influenza infection.

Objective

Assess the association between influenza vaccination status and hospitalization for community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia.

Design, Setting and Participants

The Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study was a prospective observational multicenter study of hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia conducted from January 2010 through June 2012 in four US sites. We used EPIC study data from patients ≥6 months of age with laboratory-confirmed influenza infection and verified vaccination status during the influenza seasons, and excluded patients with recent hospitalization, from chronic care residential facilities, and with severe immunosuppression. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios, comparing the odds of vaccination between influenza-positive (cases) and influenza-negative (controls) pneumonia patients, controlling for demographics, co-morbidities, season, study site and timing of disease onset. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as (1-odds ratio) × 100%.

Exposure

Influenza vaccination, verified through record review.

Outcome

Influenza pneumonia, confirmed by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction performed on nasal/oropharyngeal swabs.

Results

Overall, 2767 patients hospitalized for pneumonia were eligible for the study; 162 (5.9%) were influenza positive. Twenty-eight (17%) of 162 cases with influenza-associated pneumonia and 766 (29%) of 2605 controls with influenza-negative pneumonia had been vaccinated. The adjusted odds ratio of prior influenza vaccination between cases and controls was 0.43 (95% CI 0.28–0.68 [estimated vaccine effectiveness 56.7% (95% CI 31.9–72.5)]).

Conclusions and relevance

Among children and adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia, those with laboratory confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia, compared to those with pneumonia not associated with influenza, had lower odds of having received influenza vaccination.

Keywords: Influenza, vaccine, odds ratio, effectiveness, pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Influenza remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the United States (US), seasonal influenza epidemics are responsible for an estimated average of 226,000 hospitalizations and between 3,000–49,000 deaths each year.1,2 Pneumonia, the leading infectious cause of hospitalization and death in the US, is a relatively common and serious complication of influenza.3

The primary strategy to reduce influenza burden is vaccination. Currently, the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends annual influenza vaccination for all persons ≥6 months of age.1,2 Supporting evidence from randomized controlled trials, conducted mainly in outpatient settings, indicates that influenza vaccines are effective in preventing influenza-associated acute respiratory illnesses among healthy children and adults.4,5

Vaccine effectiveness studies based on laboratory-confirmed influenza infections and verified vaccinations are essential to evaluate the public health value of influenza vaccines and to inform vaccination policies.6,7 Recent observational studies have consistently shown that vaccination is associated with lower odds of hospitalization for laboratory-confirmed influenza acute respiratory infections.3,7–14

However, whether influenza vaccines can decrease the risk of influenza associated-hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia remains unclear.5,6,15 Since influenza vaccination is currently recommended for all persons ≥6 months old in the US, observational studies are the only option to assess vaccine effectiveness. We sought to determine whether influenza vaccination was associated with reduced odds of hospitalizations for laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia.

METHODS

Study design and population

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) Study was conducted from January 2010 through June 2012.16,17 Children and adults admitted with community-acquired pneumonia were enrolled at eight hospitals in four sites: Nashville, TN; Memphis, TN; Chicago, IL; and, Salt Lake City, UT. Pneumonia was defined as evidence of acute infection, symptoms of respiratory illness, and radiologic findings compatible with pneumonia. Patients with history of recent hospitalization, children who were residents of chronic care facilities, adults who were nursing home residents and not independently functioning (defined as score >7 in the Activities of Daily Living Scale18), and patients with severe immunosuppression were excluded.16,17 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their caretakers. After enrollment, research personnel collected socio-demographic characteristics (including interview self-reported race/ethnicity), pneumonia risk factors, and healthcare utilization information, including vaccination history. Since children <6 months are not eligible for influenza vaccination, the study was restricted to patients ≥6 months. Institutional Review Boards of the research sites and CDC approved the study.16,17

Laboratory confirmation of influenza virus infections

Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal (NP/OP) swabs were collected from each patient at enrollment, placed into transport medium and delivered to the site research laboratories. Samples were stored at −70°C and then tested in batches for influenza and other respiratory viruses using CDC’s real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) protocols.16,17 To assure integrity of the samples, the presence of human RNaseP, a housekeeping gene, was required for evaluable samples. Laboratory personnel conducting the RT-PCR testing were blinded to the patients’ vaccination status and study hypotheses.

Cases and controls

A case was a patient hospitalized for pneumonia whose NP/OP swabs collected within 72 hours of admission tested positive for influenza by RT-PCR with a cycle threshold value of <40. A control was a patient hospitalized for pneumonia who tested negative for influenza.3,7–14,19 Only patients with verified influenza infection status were included in the study.20,21

Influenza vaccination status

The study exposure was verified influenza vaccination status for the current influenza season. Detailed influenza vaccination history was collected in the study interview, and medical records were reviewed for verification. We also obtained vaccination information from state vaccination registries and from healthcare providers and pharmacies. Vaccination status included receipt of monovalent vaccines (2009–2010 season) or trivalent inactivated or live attenuated influenza vaccines (2010–2011 and 2011–2012 seasons). Per ACIP recommendations, children <9 years were considered vaccinated if they had received: 1) Two vaccine doses for the current influenza season, given ≥28 days apart with the second dose >14 days before their disease onset, or 2) One or more vaccine doses in the prior influenza season(s) and one dose for the current season >14 days before their disease onset. Children ≥9 years old and adults were considered vaccinated if they had received any influenza vaccine for the current season >14 days before their disease onset.1,2 Partially vaccinated children and patients of any age whose influenza vaccination history could not be verified were excluded.

Influenza seasons

To assure a proper evaluation of the association between influenza pneumonia risk and prior influenza vaccination, we restricted our analyses to periods of influenza activity at each site, based on CDC surveillance data (http://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/fluportaldashboard.html). We defined the beginning of the influenza season as the first week of continuous influenza activity with ≥2 positive tests for influenza virus identified in each of two consecutive weeks by the respective regional surveillance system. The season ended on the last of two consecutive weeks with <2 positive tests detected per week.22 Study enrollment was conducted from January 2010 through June 2012, and thus included part of the 2009–2010 season, and the complete 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 influenza seasons. See supplementary table 1S and figure 1S for additional details.

Statistical analyses

We examined bivariate associations between potential confounders (identified a priori) and verified vaccination status as well as laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia. Potential confounders included age, gender, race/ethnicity, family composition (e.g., presence of young or school-aged children), smoking status, insurance status, use of oxygen supplementation at home, timing of admission relative to disease onset, timing from beginning of the influenza season to admission (as the disease risk may vary during the seasons), the specific influenza season, and the presence of immunosuppressive conditions (including also cancer [except skin cancer] and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection [with CD4 counts ≥200/mm3]) and other chronic medical conditions associated with influenza-associated complications including cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver/kidney disease, and neurological disease.1–3,8

We compared the odds of influenza vaccination during the current season >14 days before disease onset between influenza cases and controls using a multivariable logistic regression model, and calculated odds ratios adjusted for relevant confounders. Influenza vaccine effectiveness (%) was estimated as (1-aOR) × 100,11, 12 where aOR was the adjusted odds ratio for influenza vaccination from the final regression model.

Planned sensitivity analyses included: 1) Inclusion of vaccination status based on self-report to assess the statistical effect of exposure misclassification; 2) Exclusion of the first influenza season (2009–2010), because our study only included part of this season; 3) Redefining the influenza seasons to periods with either at least 4% or 5% of test positive samples detected in surveillance systems, to evaluate the sensitivity of our estimates to the influenza season definition; 4) Restriction to cases and controls hospitalized within 7 and 14 days of symptom onset, to address concerns that influenza may be a concurrent infection and not the cause of pneumonia in patients with longer duration of symptoms prior to presentation;20,21 5) Restriction to patients with radiologic evidence of alveolar consolidation, infiltrate or pleural effusion, as determined by independent study radiologists, a common endpoint in pneumonia studies;23 6) Considering patients who tested negative for influenza but positive for other non-influenza viruses (including coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43; human metapneumovirus; human rhinovirus; parainfluenza viruses 1,2,3; and respiratory syncytial virus), and those patients who tested negative for all study viruses as alternate controls, to assess the hypothesis that influenza vaccination may increase the risk of non-influenza viral infections,24,25 including pneumonia, and to assess potential differential detection of respiratory viruses;20,21,25–27 7) Exclusion of patients who reported use of influenza antivirals prior to admission, as such use may interfere with RT-PCR detection of influenza infections;28 8) Reanalyzing our data adjusting for propensity scores3,8 created using variables from the main analysis and 16 additional variables for specific comorbidities, to address concerns about residual confounding; and, 9) Using respiratory syncytial virus associated-pneumonia as cases and excluding all influenza cases, to assess the specificity of the main findings.

Subgroup analyses included estimations by age group, presence of immunosuppressive and chronic conditions, study site and influenza season. For these subgroups analyses, interaction terms between subgroup and vaccination status were examined. Estimates for each subgroup were calculated using linear combinations of coefficients from the regression models that included the interaction terms. Separate exploratory analyses for influenza type/subtype, and influenza cases with and without co-detection of other pathogens16 were also conducted.

All reported tests were 2-sided and a p value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 and R 3.0.2.

RESULTS

Study population

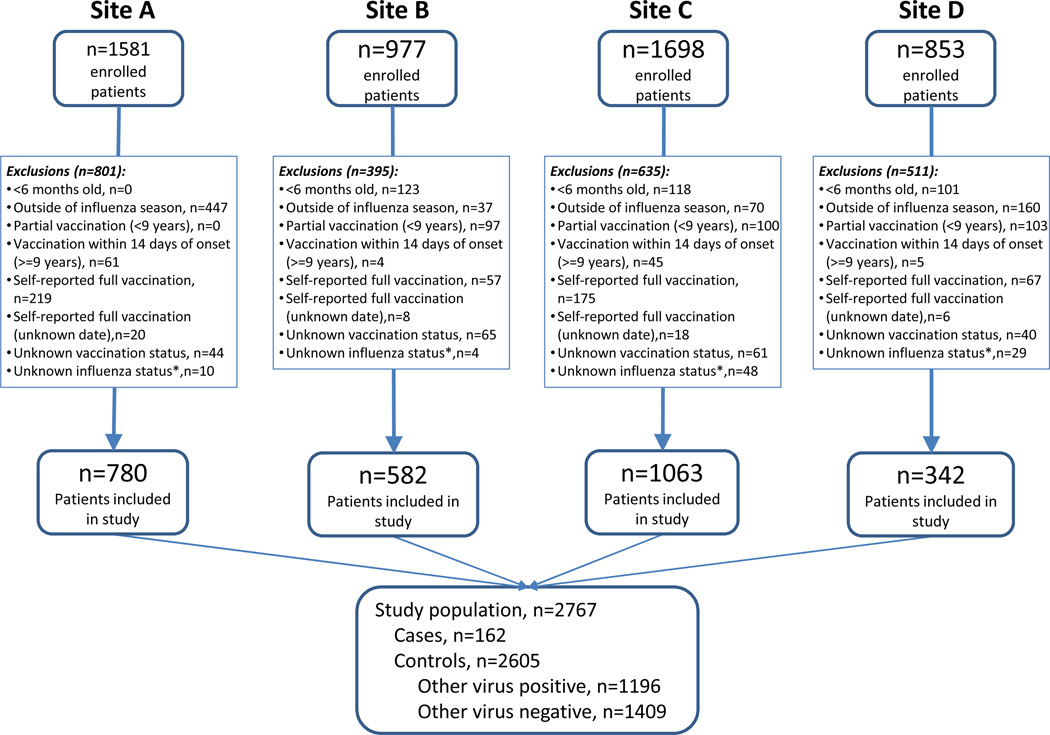

Forty-six percent of patients enrolled in the EPIC study (n=5109) were excluded for the following reasons: age <6 months (n=342, 7%), enrollment outside of the influenza season (714, 14%), children with partial vaccination (300, 6%), vaccination within 14 days of disease onset (115, 2%), self-reported vaccination (518, 10%), self-reported vaccination with unknown vaccination date (52, 1%), unknown vaccination status (210, 4%) and unknown influenza infection status (91, 2%). After exclusions, 2767 patients were included in this study (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Patient flow chart in study.

Footnote: Research sites B and D enrolled only children, site A enrolled only adults and site C enrolled both children and adults; *Influenza infection status could not be determined in 91 patients (1.8% of total enrolled), including patients without samples available for testing and patients with samples collected after 72 hours of admission or with missing data on the time of sample collection.

One hundred sixty-two of 2767 pneumonia patients tested positive for influenza (5.9%) by RT-PCR and were defined as cases, including 62 (38%) with A(H1N1)pdm09, 51 (31%) with A(H3N2), 43 (27%) with influenza B, 4 with influenza A with no available subtype information (3%) and 2 co-infections with influenza A and B (1%). Among 162 influenza cases, 116 cases had only influenza viruses detected, 32 had a viral co-detection and 14 had a bacterial co-detection. A total of 2605 controls were identified for comparison, including 1196 controls that tested positive for other respiratory viruses and 1409 controls that tested negative for all viruses tested.

Characteristics of cases and controls

Compared with influenza-negative controls, influenza-positive cases had similar age distribution but were more likely to be black and enrolled during the 2010–2011 influenza season. The distribution of influenza cases differed by study site. The prevalence of congenital heart disease and heart failure was higher among controls. Relative to cases, controls were admitted earlier during the influenza seasons. The distribution of other socio-demographic factors and co-morbidities was generally similar in both groups (Tables 1 and 2). There were 2 (1%) in-hospital deaths among cases, and 29 (1%) among controls.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study patients by influenza infection and vaccination status

| Controls - non influenza pneumonia (n=2605) |

Cases – influenza pneumonia (n=162) |

P value | Non-vaccinated (n=1973) |

Vaccinated (n=794) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children, % (n) | 50% (1309) | 42% (68) | 0.04 | 50% (994) | 48% (383) | 0.31 |

| Overall age, median (IQR) | 17 (3, 55) | 31 (5, 54) | 0.18 | 17 (3, 53) | 28 (2, 65) | <0.001 |

| Children age (years), median (IQR) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (1, 9) | 0.23 | 3 (1, 7) | 2 (1, 6) | 0.06 |

| Adults age (years), median (IQR) | 55 (44, 68) | 52.5 (40, 63) | 0.03 | 53 (41.5, 64) | 63 (52, 74.5) | <0.001 |

| Female gender, % (n) | 48% (1259) | 45% (73) | 0.42 | 48% (943) | 49% (389) | 0.57 |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | 0.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 42% (1096) | 31% (50) | 39% (771) | 47% (375) | ||

| Black | 39% (1016) | 48% (77) | 43% (858) | 30% (235) | ||

| Hispanic | 14% (361) | 15% (25) | 13% (249) | 17% (137) | ||

| Other | 5% (132) | 6% (10) | 5% (95) | 6% (47) | ||

| Children <5 years old at home % (n) | 0.06 | 0.70 | ||||

| 0 | 22% (563) | 23% (38) | 22% (432) | 21% (169) | ||

| 1 or more | 44% (1143) | 35% (56) | 43% (845) | 45% (354) | ||

| Unknown | 35% (899) | 42% (68) | 35% (696) | 34% (271) | ||

| Children 5–17 years old at home % (n) | 0.90 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 22% (577) | 23% (37) | 21% (406) | 26% (208) | ||

| 1 or more | 45% (1175) | 43% (70) | 47% (933) | 39% (312) | ||

| Unknown | 33% (853) | 34% (55) | 32% (634) | 35% (274) | ||

| Research Site, % (n) | 0.004 | <0.001 | ||||

| A | 28% (717) | 39% (63) | 30% (587) | 24% (193) | ||

| B | 21% (544) | 23% (38) | 25% (497) | 11% (85) | ||

| C | 39% (1017) | 28% (46) | 34% (664) | 50% (399) | ||

| D | 13% (327) | 9% (15) | 11% (225) | 15% (117) | ||

| Influenza Season, % (n) | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2009–2010 | 12% (305) | 4% (6) | 13% (266) | 6% (45) | ||

| 2010–2011 | 49% (1283) | 60% (97) | 48% (954) | 54% (426) | ||

| 2011–2012 | 39% (1017) | 36% (59) | 38% (753) | 41% (323) | ||

| Insurance, % (n) | 0.01 | <0.001 | ||||

| Public | 54% (1396) | 56% (91) | 52% (1035) | 57% (452) | ||

| Private | 30% (785) | 25% (40) | 29% (581) | 31% (244) | ||

| Both | 7% (176) | 3% (5) | 5% (104) | 10% (77) | ||

| None/other | 10% (248) | 16% (26) | 13% (253) | 3% (21) |

Footnote: Research sites B and D enrolled only children, site A enrolled only adults and site C enrolled both children and adults; Additional information on the characteristics of the study population is available in supplementary tables 2S and 3S.

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of study patients by influenza infection and vaccination status

| Controls - non influenza pneumonia (n=2605) |

Cases – influenza pneumonia (n=162) |

P value | Non-vaccinated (n=1973) |

Vaccinated (n=794) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities and risk factors | ||||||

| Need oxygen supplementation at home, % (n) | 7% (190) | 6% (10) | 0.59 | 5% (96) | 13% (104) | <0.001 |

| Adult BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 27.4 (23.0, 33.0) | 27.9 (25.1, 34.7) | 0.08 | 27.4 (23.1, 32.9) | 27.7 (23.0, 33.4) | 0.76 |

| Children BMI categories | 1.00 | 0.84 | ||||

| Underweight | 20% (149) | 20% (8) | 19% (115) | 20% (42) | ||

| Normal | 55% (419) | 54% (22) | 55% (324) | 56% (117) | ||

| Overweight | 11% (85) | 12% (5) | 11% (65) | 12% (25) | ||

| Obese | 14% (108) | 15% (6) | 15% (88) | 12% (26) | ||

| Smoking, % (n) | 0.007 | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-smoking | 68% (1773) | 61% (99) | 68% (1346) | 66% (526) | ||

| Current smoking | 14% (374) | 23% (38) | 17% (327) | 11% (85) | ||

| Past smoking | 18% (458) | 15% (25) | 15% (300) | 23% (183) | ||

| Unknown | 4% (99) | 6% (10) | 4% (85) | 3% (24) | ||

| Chronic conditions | 62% (1628) | 56% (91) | 0.11 | 59% (1159) | 71% (560) | <0.001 |

| Asthma or Reactive Airway Disease | 33% (852) | 33% (53) | 1.00 | 32% (635) | 34% (270) | 0.36 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 11% (292) | 11% (18) | 0.97 | 9% (170) | 18% (140) | <0.001 |

| Congenital Heart Disease | 3% (87) | 0% (0) | 0.02 | 3% (51) | 5% (36) | 0.008 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 14% (358) | 15% (24) | 0.70 | 11% (211) | 22% (171) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 11% (279) | 5% (8) | 0.02 | 7% (145) | 18% (142) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13% (337) | 12% (19) | 0.66 | 12% (227) | 16% (129) | <0.001 |

| Blood Disorder (e.g. sickle cell disease) | 7% (189) | 5% (8) | 0.27 | 6% (120) | 10% (77) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 8% (221) | 6% (9) | 0.19 | 6% (125) | 13% (105) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Liver Disease | 3% (82) | 6% (9) | 0.10 | 3% (60) | 4% (31) | 0.25 |

| Splenectomy | 1% (31) | 0% (0) | 0.16 | 1% (16) | 2% (15) | 0.02 |

| Non-cancer immunosuppressive condition | 9% (236) | 11% (18) | 0.38 | 7% (134) | 13% (106) | <0.001 |

| HIV | 2% (43) | 4% (6) | 0.06 | 1% (25) | 3% (24) | <0.002 |

| Cancer | 9% (230) | 8% (13) | 0.73 | 7% (131) | 14% (112) | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppression | 15% (393) | 17% (28) | 0.45 | 7% (142) | 14% (112) | <0.001 |

| Seizure disorder | 5% (137) | 6% 10) | 0.62 | 5% (95) | 7% (52) | 0.07 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 3% (86) | 2% (3) | 0.31 | 2% (45) | 6% (44) | <0.001 |

| Cerebral Palsy | 1% (35) | 2% (3) | 0.59 | 1% (22) | 2% (16) | 0.07 |

| Dementia | 1% (24) | 1% (1) | 0.69 | 1% (14) | 1% (11) | 0.09 |

| Stroke | 3% (72) | 1% (2) | 0.24 | 2% (45) | 4% (29) | 0.04 |

| Guillain-Barre Syndrome | 0% (4) | 1% (1) | 0.18 | 0% (2) | 0% (3) | 0.12 |

| Scoliosis | 1% (14) | 1% (1) | 0.89 | 1% (10) | 1% (5) | 0.69 |

| Down’s Syndrome | 1% (38) | 0% (0) | 0.12 | 1% (18) | 3% (20) | <0.001 |

| Other Chromosomal Abnormality | 1% (36) | 1% (2) | 0.88 | 1% (23) | 2% (15) | 0.14 |

| Currently on steroids | 11% (289) | 11% (18) | 1.00 | 10% (192) | 14% (115) | <0.001 |

| Influenza and vaccination status, and timing of admission | ||||||

| Verified influenza vaccination, % (n) | 29% (766) | 17% (28) | 0.002 | 0% | 100% | − |

| Influenza confirmed by RT-PCR, % (n) | 0% | 100% | − | 7% (134) | 4% (28) | <0.001 |

| Disease onset to admission, median days (IQR) | 3 (2,7) | 3 (2, 6) | 0.78 | 3 (2, 7) | 3 (2, 6) | 0.51 |

| Admission week in flu season, median (IQR) | 20.0 (13.0, 31.0) | 26.0 (18.0, 32.8) | <0.001 | 18 (11, 29) | 27 (19, 35) | <0.001 |

| Days from vaccination to admission, median (IQR) | 108.5 (64.0, 163.0) | 124.0 (90.2, 150.2) | 0.52 | 109.5 (64.2, 162.8) | ||

| Days from season start to admission, median (IQR) | 138 (84, 214) | 180 (124, 224) | <0.001 | 124 (76, 198) | 184 (127, 240) | <0.001 |

Footnote: Immunosuppression included non-cancer immunosuppressive conditions, cancer (other than skin cancer) and HIV infection with CD4 count ≥200/mm3; chronic conditions encompass medical conditions associated with influenza-associated complications including cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, blood disorders, chronic liver/kidney disease, immunosuppressive conditions (including cancer), and neuromuscular diseases. BMI categories for children were determined per CDC guidelines: Underweight (<5th BMI-for-age percentile), Normal (5th – <85th percentile), Overweight (85th – <95th percentile), and Obese (>=95th percentile). Additional information on the characteristics of the study population is available in supplementary tables 2S and 3S.

Characteristics of vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with pneumonia

A total of 794 (29%) patients with pneumonia were vaccinated during current influenza seasons. Compared with unvaccinated patients, vaccinated patients were older, more likely to be white and enrolled during the 2010–2011 influenza season. The prevalence of influenza vaccination differed by study research site. The prevalence of current smoking was lower among vaccinated patients, although they were more likely to be past smokers and require home oxygen supplementation. The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and other chronic medical conditions was generally higher among vaccinated than unvaccinated patients. Unvaccinated patients were admitted earlier than vaccinated patients during the respective influenza seasons (Tables 1 & 2). There were 11 (1%) in-hospital deaths among vaccinated patients, and 20 (1%) among unvaccinated patients. See supplementary tables 2S and 3S for additional details.

Association between prior influenza vaccination and hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia

Of 162 influenza-associated pneumonia cases, 28 (17%) were vaccinated compared with 766 (29%) of 2605 influenza-negative controls. The adjusted odds ratio comparing the odds of prior vaccination among those with influenza-positive pneumonia (cases) with the odds of prior vaccination among those with influenza-negative pneumonia (controls) was 0.43 (95% CI 0.28–0.68 [estimated vaccine effectiveness 56.7% (31.9%-72.5%)]). See supplementary table 4S for additional details.

Results from sensitivity analyses that evaluated key study definitions and assumptions were similar to the main findings. There was no association between influenza vaccination and respiratory syncytial virus-pneumonia (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity Analyses

| Sensitivity Analyses | Vaccinated / Cases (%) |

Vaccinated / Controls (%) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Estimated vaccine effectiveness (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall estimate | 28 / 162 (17%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.43 (0.28, 0.68) | 56.7 (31.9, 72.5) |

| Including self-reported vaccination | 56 / 190 (29%) | 1241 / 3270 (38%) | 0.52 (0.37, 0.75) | 47.5 (25.3, 63.2) |

| Influenza season defined using >4% positive tests per week | 28 / 154 (18%) | 579 / 1563 (37%) | 0.41 (0.26, 0.65) | 59.1 (35.3, 74.1) |

| Influenza season defined using >5% positive tests per week | 28 / 153 (18%) | 523 / 1458 (36%) | 0.40 (0.25, 0.63) | 60.1 (36.8, 74.8) |

| Season 2010–2012 | 28 / 156 (18%) | 721 / 2300 (31%) | 0.44 (0.28, 0.69) | 56.4 (31.2, 72.3) |

| Restricted to 7 days of symptoms onset | 23 / 136 (17%) | 624 / 2071 (30%) | 0.41 (0.25, 0.68) | 58.9 (32.3, 75.0) |

| Restricted to 14 days of symptoms onset | 26 / 154 (17%) | 710 / 2379 (30%) | 0.43 (0.27, 0.68) | 57.3 (31.7, 73.2) |

| Restricted to radiographic consolidation or pleural effusion | 24 / 139 (17%) | 700 / 2389 (29%) | 0.43 (0.27, 0.71) | 56.6 (29.2, 73.4) |

| Use of influenza (−), other virus (+) as controls | 28 / 162 (17%) | 368 / 1196 (31%) | 0.37 (0.23, 0.61) | 62.8 (39.5, 77.1) |

| Use of influenza (−), other virus (−) as controls | 28 / 162 (17%) | 398 / 1409 (28%) | 0.46 (0.29, 0.74) | 53.8 (25.5, 71.4) |

| Exclude subjects with previous use of antivirals | 27 / 155 (17%) | 750 / 2546 (29%) | 0.44 (0.28, 0.70) | 56.2 (30.4, 72.4) |

| Propensity score-adjusted analysis | 28 / 162 (17%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.45 (0.29, 0.72) | 54.9 (28.5, 71.5) |

| Use of respiratory syncytial virus-pneumonia as cases | 125 / 396 (32%) | 641 / 2209 (29%) | 1.18 (0.88, 1.58)* | −18.0 (−57.6, 11.7) |

Footnote: Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as (1-adjusted odds ratios) × 100; where odds ratios compared the odds of vaccination between cases and controls while controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, presence of children at home, smoking status, insurance status, use of oxygen supplementation at home, timing of admission relative to disease onset, timing from beginning of the influenza season to admission, the specific influenza season, and the presence of immunosuppressive conditions and other chronic medical conditions associated with influenza-associated complications including cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver/kidney disease, and neurological disease. Sensitivity analyses included: inclusion of self-reported vaccination data; influenza seasons defined as having at least 4% or 5% positive influenza tests per week; restriction to complete seasons 2010–2011 & 2011–2012; restriction to hospitalizations within 7 & 14 days of disease onset; restriction to patients with independent radiologic assessment indicating consolidation, infiltrate or pleural effusion; defining control pneumonia patients as those who were influenza negative but tested positive for other respiratory viruses; defining control pneumonia patients as those who tested negative for all respiratory viruses; excluding patients with any antiviral use before admission; propensity score-adjusted analysis included 16 additional variables for individual chronic medical conditions; and, a separate analysis that evaluated the association between influenza vaccination and respiratory syncytial virus-pneumonia.

Although this odds ratio was not statistically different from 1, the point-estimate odds ratio greater than 1 (and the corresponding negative vaccine effectiveness point-estimate) indicates that the odds of vaccination among cases was numerically higher than the odds of vaccination among controls.

In subgroup analyses, 7 (10%) of 68 children cases were vaccinated compared with 376 (29%) of 1309 control children (adjusted odds ratio 0.25; 95% CI 0.11–0.58); whereas among adults, 21 (22%) of 94 cases were vaccinated compared with 390 (30%) of 1296 controls (adjusted odds ratio 0.59, 95% CI 0.34–1.02). Among children 0.5–4 years old, 3 (8%) of 40 cases and 266 (31%) of 850 controls were vaccinated, (adjusted odds ratio 0.16, 95% CI 0.05–0.53). Among older children and adults, the differences in vaccination between cases and controls were more modest. Among patients without immunosuppression, 13 (10%) of 147 cases were vaccinated compared with 592 (27%) of 2212 controls; whereas, among patients with immunosuppression, 15 (54%) of 28 cases were vaccinated compared with 174 (44%) of 393 controls. The adjusted odds ratio of prior vaccination between cases and controls was significantly lower among patients without immunosuppression (0.27; 95% CI: 0.15–0.49) compared with patients with immunosuppression (1.22; 95% CI: 0.55–2.71). Influenza vaccination was higher among patients with chronic diseases than among those without, and in both groups, vaccination in cases was lower than vaccination in controls (adjusted odds ratio point estimates 0.54 and 0.24, respectively). Differences in vaccination by site likely reflected the age of the study populations at the sites, and the adjusted odds ratios point estimates ranged from 0.26 to 0.50 across sites. In each of the two complete study influenza seasons, 2010–2011 and 2011–2012, vaccination was lower among cases than among controls, and the odds ratio point estimate was 0.44 for both seasons. However, some subgroup analyses had limited precision due to small numbers (Table 4). In separate analyses that evaluated influenza pneumonia cases with and without co-pathogen detections, the odds ratio of vaccination between cases and controls was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.25–0.73) and 0.42 (95% CI: 0.18–0.99), respectively.

TABLE 4.

Subgroup analyses

| Subgroups | Vaccinated / Cases (%) |

Vaccinated / Controls (%) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Estimated vaccine effectiveness (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Estimate | 28 / 162 (17%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.43 (0.28, 0.68) | 56.7 (31.9, 72.5) |

| Groups (p=0.096) | ||||

| Children | 7 / 68 (10%) | 376 / 1309 (29%) | 0.25 (0.11, 0.58) | 74.6 (42.5, 88.8) |

| Adults | 21 / 94 (22%) | 390 / 1296 (30%) | 0.59 (0.34, 1.02) | 41.5 (−2.2, 66.5) |

| Age groups (p=0.412) | ||||

| Age 0.5–4 years | 3 / 40 (8%) | 266 / 850 (31%) | 0.16 (0.05, 0.53) | 84.3 (47.3, 95.3) |

| Age 5–17 years | 4 / 28 (14%) | 110 / 459 (24%) | 0.48 (0.16, 1.44) | 52.4 (−43.5, 84.2) |

| Age 18–49 years | 4 / 36 (11%) | 76 / 433 (18%) | 0.57 (0.19, 1.73) | 43.1 (−72.5, 81.2) |

| Age 50–64 years | 9 / 38 (24%) | 122 / 354 (34%) | 0.66 (0.29, 1.50) | 33.9 (−49.7, 70.8) |

| Age 65+ years | 8 / 20 (40%) | 192 / 409 (47%) | 0.52 (0.20, 1.33) | 48.4 (−33.3, 80) |

| Immunosuppression (p=0.003) | ||||

| No | 13 / 134 (10%) | 592 / 2212 (27%) | 0.27 (0.14, 0.49) | 73.4 (51.1, 85.5) |

| Yes | 15 / 28 (54%) | 174 / 393 (44%) | 1.22 (0.55, 2.71)£ | −21.9 (−170.7, 45.1) |

| Chronic Diseases (p=0.141) | ||||

| No | 5 / 71 (7%) | 229 / 977 (23%) | 0.24 (0.09, 0.62) | 75.7 (37.6, 90.6) |

| Yes | 23 / 91 (25%) | 537 / 1628 (33%) | 0.54 (0.32, 0.91) | 45.9 (8.6, 67.9) |

| Research Sites (p=0.825) | ||||

| A* | 11 / 63 (17%) | 182 / 717 (25%) | 0.49 (0.24, 1.02) | 51.1 (−1.56, 76.41) |

| B** | 2 / 38 (5%) | 83 / 544 (15%) | 0.26 (0.06, 1.10) | 74.2 (−10.5, 94) |

| C | 12 / 46 (26%) | 387 / 1017 (38%) | 0.50 (0.25, 0.99) | 50.5 (1.1, 75.3) |

| D** | 3 / 15 (20%) | 114 / 327 (35%) | 0.33 (0.09, 1.21) | 67.2 (−20.8, 91.1) |

| Influenza Seasons*** (p=0.981) | ||||

| Season 2010–2011 | 18 / 97 (19%) | 408 / 1283 (32%) | 0.44 (0.25, 0.77) | 55.9 (22.5, 74.8) |

| Season 2011–2012 | 10 / 59 (17%) | 313 / 1017 (31%) | 0.44 (0.22, 0.90) | 55.9 (9.8, 78.4) |

| Virus type/subtype**** | ||||

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 9 / 62 (15%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.40 (0.19, 0.87) | 59.5 (13.0, 81.2) |

| A(H3N2) | 14 / 51 (27%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.55 (0.28, 1.09) | 45.1 (−9.3, 72.4) |

| B | 4 / 43 (9%) | 766 / 2605 (29%) | 0.28 (0.09, 0.83) | 72.0 (16.8, 90.6) |

Footnote: Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as (1-adjusted odds ratios)*100; where odds ratios compared the odds of vaccination between cases and controls while controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, presence of children at home, smoking status, insurance status, use of oxygen supplementation at home, timing of admission relative to disease onset, timing from beginning of the influenza season to admission, the specific influenza season, and the presence of immunosuppressive conditions and other chronic medical conditions associated with influenza-associated complications including cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver/kidney disease, and neurological disease.

Although this odds ratio was not statistically different from 1, the point-estimate odds ratio greater than 1 (and the corresponding negative vaccine effectiveness point-estimate) indicates that the odds of vaccination among cases was numerically higher than the odds of vaccination among controls.

Adult only site;

Children only site;

Estimates for season 2009–2010 could not be calculated separately because there were no vaccinated subjects among the influenza cases;

Separate estimates were conducted for influenza virus type/subtype. Reported p values correspond to the interaction term between subgroup and vaccination status. Subgroup estimates were calculated using linear combinations of coefficients from the regression models that included the interaction terms.

In separate assessments, the odds ratio of vaccination between cases and controls was 0.41 (95% CI: 0.19–0.87) for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, 0.55 (95% CI: 0.28–1.09) for influenza A(H3N2), and 0.28 (95% CI: 0.09–0.83) for influenza B (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that the odds of influenza vaccination among cases hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia was lower than among non-influenza pneumonia controls, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.43 (95% CI 0.28–0.68 [estimated vaccine effectiveness 56.7%]) during 2009–2012 influenza seasons. This large multi-center study addressed several concerns identified in previous influenza vaccine effectiveness assessments. By performing systematic influenza testing for all patients with pneumonia, our study relied on an unbiased sample of laboratory-confirmed influenza-pneumonia hospitalizations. Our patients with pneumonia were prospectively identified, minimizing concerns about outcome misclassification. To assure a proper evaluation of the association between influenza pneumonia risk and prior influenza vaccination, the study was restricted to influenza seasons and to patients with similar propensity to require hospital care. Furthermore, vaccination information was actively collected, and only patients with pneumonia and verified influenza vaccination history were included in our main analyses.

Previous studies that used a similar design have shown that influenza vaccination is effective in preventing hospitalizations for acute respiratory illnesses associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza.3,7–14 Although some studies had limited precision, the point estimates of effectiveness ranged from 53% to 67% among children,10,11 from 54% to 71% among all adults,3,12 and from 42% to 61% among adults 65 years or older.8,13 However, few studies have examined the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in preventing complications of influenza infections, such as pneumonia. In a recent multinational randomized controlled trial of a new quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in children 3–8 years old, a post-hoc analysis of influenza-associated lower respiratory tract illness alone yielded a vaccine efficacy estimate of approximately 80%.29 Likewise, a recent case-control study estimated that influenza vaccination was associated with a 74% reduction in the odds of pediatric intensive care units admission during the 2010–2012 seasons.30

Although previous studies focusing on the prevention of all-cause pneumonia have suggested a modest effectiveness of influenza vaccines,15,31 using all-cause pneumonia as the outcome for influenza vaccine effectiveness assessments is problematic because influenza is responsible for only a fraction of all pneumonias and varies seasonally, resulting in an underestimation of the true vaccine effectiveness.6,20,21,32 Our study avoided this misclassification by applying a prospective and systematic approach for confirming influenza infections and a standardized definition of hospitalizations for pneumonia. The estimated odds ratio of vaccination between cases and controls, and derived vaccine effectiveness from this study, could be used to inform subsequent estimations of the national number of hospitalizations for pneumonia averted by influenza vaccination.33

Findings from our subgroup analyses suggest that the odds ratio of prior influenza vaccination between cases and controls was higher in patients with immunosuppressive conditions, including cancers and HIV infection, suggesting lower vaccine effectiveness. Although several studies have described reduced immunogenicity of influenza vaccines in immunosuppressed patients, few have evaluated the vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza pneumonia in patients with these conditions. A small, open label randomized controlled trial of influenza vaccination among patients with multiple myeloma reported a non-significant reduction in all-cause pneumonia, but the number of events was small and the study included only one season.34 Other observational influenza vaccine effectiveness studies have reported reductions in all-cause pneumonia in patients with immunosuppressive conditions; but these events were not confirmed influenza infections.35 Evidence for the effectiveness of influenza vaccines in preventing pneumonia among patients with HIV infection is also limited.36 While these findings warrant replication in other settings, they highlight the vulnerability of older adults and patients with immunosuppressive conditions, and the need for additional measures to reduce their risk of influenza infection and related complications.

One concern with observational studies of influenza-associated hospitalizations is the control of unmeasured or poorly measured confounding factors, such as disease severity or baseline characteristics that increase the likelihood that pneumonia will require hospitalization. For example, retrospective studies of influenza vaccination and all-cause mortality have reported that indicators of poor functional status are relevant confounders because they are associated with both likelihood of not being vaccinated and risk of death, but are rarely considered.37 Our study used a test-positive case test-negative control design, a design widely used for vaccine effectiveness assessments that has been shown to be superior to case-control studies of hospitalized cases with population controls, since the likelihood of hospitalization is implicitly accounted for.20,21 In addition, our study excluded nursing home residents with limited functional status and prospectively gathered information on risk factors for pneumonia.20,38,39

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, although we conducted an extensive evaluation of potential threats to the validity of our estimates, our observational design is vulnerable to some misclassification and residual confounding. Nevertheless, the use of a well-established design, and the consistency of findings in a number of pre-specified sensitivity analyses conducted to evaluate key assumptions should help allay these concerns. Second, despite enrollment over three consecutive seasons, a relatively small number of influenza-associated pneumonia cases met eligibility criteria, resulting in limited precision for some subgroup analyses. Thus, the association between influenza vaccines and pneumonia in older adults remains controversial, and additional studies in this group are needed.2,5,7 Although there are different types of vaccines available and some ecological evidence suggest that influenza A(H3N2) strains are associated with higher pneumonia mortality,40 more detailed assessments by vaccine type, specific influenza types/subtypes or history of previous vaccination were not possible. Third, patients missing verified vaccination status were excluded from our main analysis. However, a sensitivity analysis showed that including patients with un-verified but self-reported vaccination information likely introduced misclassification and diluted the observed association. If influenza cases that were excluded because of unknown vaccination were indeed not vaccinated, then our findings could have overestimated the true odds ratios (and underestimated the vaccine effectiveness). Fourth, while our study comprised a diverse population, it only included four US geographical areas, which may prevent direct extrapolation of our findings to other settings. Fifth, our study included only a few influenza seasons during which vaccine strains were generally well matched with the circulating influenza strains.40 Sixth, we acknowledge that it is possible that some pneumonia cases were secondary to an earlier influenza infection that could have been missed by our tests. However, this concern is attenuated since the median time from disease onset to hospitalization was only 3 days. Finally, our study focused on pneumonia hospitalizations only, and additional studies in the ambulatory setting would be useful to complement these findings.2,7

Conclusion

Among children and adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia, those with laboratory confirmed influenza-associated pneumonia, compared to those with pneumonia not associated with influenza, had lower odds of having received influenza vaccination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Zhu reports grants from CDC. Dr. Self reports grants from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; other from CareFusion, grants from BioMerieux, grants from Affinium Pharmaceuticals, grants from Astute Medical, grants from Crucell Holland BV, grants from BRAHMS GmbH, grants from Pfizer, grants from Rapid Pathogen Screening, grants from Venaxis, grants from Cempra Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from BioFire Diagnostics; In addition, Dr. Self has a patent 13/632,874 (Sterile Blood Culture Collection System) pending. Dr. Ampofo reports grant from CDC, and collaboration with BioFire Diagnostics, Inc on several NIH projects. Dr. Pavia reports personal fees from BioFire Diagnostics, grants from AHRQ/Pfizer, personal fees from Medscape Inc, personal fees from Antimicrobial Therapy Inc. Dr. Stockmann reports grants from American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education. Dr. Arnold reports grants from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Wunderink reports personal fees from Visterra Inc, other from Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc,; personal fees from bioMerieux. Dr. Anderson reports grants and non-financial support from MedImmune, grants and non-financial support from Roche. Dr. Griffin reports grants from MedImmune. Dr. Edwards report grants from NIH and CDC, and Novartis, and participation in Data Monitoring Boards for University of Maryland and Novartis.

Funding/Support

This study was funded by the Influenza Division in the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Role of the Funders/Sponsors

Investigators from CDC, the study sponsor, participated in the conduct of the study; collection, management, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The sponsors did not perform any of the study analyses.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Authors’ contributions

Drs. Grijalva and Zhu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Study concept and design: Grijalva, Griffin, Edwards.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Grijalva, Zhu, Williams, Self, Ampofo, Pavia, Stockmann, McCullers, Arnold, Wunderink, Anderson, Lindstrom, Fry, Foppa, Finelli, Bramley, Jain, Griffin, Edwards

Drafting of the manuscript: Grijalva, Griffin, Edwards.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Grijalva, Zhu, Williams, Self, Ampofo, Pavia, Stockmann, McCullers, Arnold, Wunderink, Anderson, Lindstrom, Fry, Foppa, Finelli, Bramley, Jain, Griffin, Edwards

Statistical analysis: Grijalva, Zhu.

Obtained funding: Ampofo, McCullers, Wunderink, Edwards.

Study supervision: Grijalva, Finelli, Bramley, Jain, Griffin, Edwards.

Declaration of interests

Other authors: nothing to disclose.

Previous Presentation

An abstract of part of this work was presented at the IDWeek Annual meeting 2013; San Francisco, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) - United States, 2014–15 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(32):691–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot HK, Zhu Y, Chen Q, Williams JV, Thompson MG, Griffin MR. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine for preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations in adults, 2011–2012 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1774–1777. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belshe RB, Edwards KM, Vesikari T, et al. Live attenuated versus inactivated influenza vaccine in infants and young children. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7):685–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belongia EA, Shay DK. Influenza vaccine for community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):352–354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61137-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin MR. Influenza vaccination: a 21st century dilemma. South Dakota medicine : the journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association. 2013;Spec no:110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talbot HK, Griffin MR, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Williams JV, Edwards KM. Effectiveness of seasonal vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in community dwelling older adults. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(4):500–508. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treanor JJ, Talbot HK, Ohmit SE, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines in the United States during a season with circulation of all three vaccine strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):951–959. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staat MA, Griffin MR, Donauer S, et al. Vaccine effectiveness for laboratory-confirmed influenza in children 6–59 months of age, 2005–2007. Vaccine. 2011;29(48):9005–9011. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menniti-Ippolito F, Da Cas R, Traversa G, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against severe laboratory-confirmed influenza in children: Results of two consecutive seasons in Italy. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4466–4470. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puig-Barbera J, Diez-Domingo J, Arnedo-Pena A, et al. Effectiveness of the 2010–2011 seasonal influenza vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza hospitalizations in adults: a case-case comparison, case-control study. Vaccine. 2012;30(39):5714–5720. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwong JC, Campitelli MA, Gubbay JB, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations among elderly adults during the 2010–2011 season. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(6):820–827. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castilla J, Godoy P, Dominguez A, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing outpatient, inpatient, and severe cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(2):167–175. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferdinands JM, Gargiullo P, Haber M, Moore M, Belongia EA, Shay DK. Inactivated influenza vaccines for prevention of community-acquired pneumonia: the limits of using nonspecific outcomes in vaccine effectiveness studies. Epidemiology. 2013;24(4):530–537. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182953065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Johnson E, Cross RT, Monto AS. Efficacy studies of influenza vaccines: effect of end points used and characteristics of vaccine failures. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(9):1309–1315. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine. 2013;31(17):2165–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM, Shay DK. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31(30):3104–3109. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355(1):31–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherian T, Mulholland EK, Carlin JB, et al. Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(5):353–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, Nishiura H, et al. Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):1778–1783. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaram ME, McClure DL, VanWormer JJ, Friedrich TC, Meece JK, Belongia EA. Influenza vaccination is not associated with detection of noninfluenza respiratory viruses in seasonal studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(6):789–793. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly H, Jacoby P, Dixon GA, et al. Vaccine Effectiveness Against Laboratory-confirmed Influenza in Healthy Young Children: A Case-Control Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(2):107–111. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318201811c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cowling BJ, Nishiura H. Virus interference and estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness from test-negative studies. Epidemiology. 2012;23(6):930–931. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b300e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fry AM, Goswami D, Nahar K, et al. Efficacy of oseltamivir treatment started within 5 days of symptom onset to reduce influenza illness duration and virus shedding in an urban setting in Bangladesh: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain VK, Rivera L, Zaman K, et al. Vaccine for prevention of mild and moderate-to-severe influenza in children. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2481–2491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferdinands JM, Olsho LE, Agan AA, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine against life-threatening RT-PCR-confirmed influenza illness in US children, 2010–2012. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(5):674–683. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Neuzil KM, Barlow W, Jackson LA. Influenza vaccination and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent elderly people: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson ML, Yu O, Nelson JC, et al. Further evidence for bias in observational studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness: the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(8):1327–1336. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostova D, Reed C, Finelli L, et al. Influenza Illness and Hospitalizations Averted by Influenza Vaccination in the United States, 2005–2011. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musto P, Carotenuto M. Vaccination against influenza in multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology. 1997;97(2):505–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eliakim-Raz N, Vinograd I, Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Leibovici L, Paul M. Influenza vaccines in immunosuppressed adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD008983. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008983.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck CR, McKenzie BC, Hashim AB, et al. Influenza vaccination for immunocompromised patients: summary of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. 2013;7(Suppl 2):72–75. doi: 10.1111/irv.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson LA, Nelson JC, Benson P, et al. Functional status is a confounder of the association of influenza vaccine and risk of all cause mortality in seniors. International journal of epidemiology. 2006;35(2):345–352. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming DM, Andrews NJ, Ellis JS, et al. Estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness using routinely collected laboratory data. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(12):1062–1067. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.093450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orenstein EW, De Serres G, Haber MJ, et al. Methodologic issues regarding the use of three observational study designs to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):623–631. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu Activity & Surveillance[Internet site] [Accessed June 15 2015]; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivitysurv.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.