Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to examine the self-report of experiences, attitudes, and perceived educational needs of American Chiropractic Association members regarding practice in integrated health care settings.

Methods

This was a descriptive observational study of the American Chiropractic Association members. Participants completed an electronic survey reporting their current participation and interest in chiropractic integrated practice.

Results

The survey was completed in 2011 by 1142 respondents, for a response rate of 11.8%. The majority of respondents (82.9%) did not currently practice in an integrated setting, whereas 17.1% did. Those practicing in various integrated medical settings reported delivering a range of diagnostic, therapeutic, and case management services. Participation in administrative and scholarly activities was less common. Respondents not practicing in integrated settings reported being interested in delivering a very similar array of clinical services. Doctors of chiropractic practicing in hospital or outpatient medical facilities reported frequent engagement in interprofessional collaboration. Both nonintegrated and integrated respondents reported very similar educational interests on a range of clinical topics.

Conclusion

The findings of this survey provide insight into the experiences, participation, and interests in integrated clinical practice for members of the American Chiropractic Association.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic; Delivery of health care, integrated; Interdisciplinary communication; Cooperative behavior

Introduction

Over the past decade, the chiropractic profession has seen expanded collaboration with and participation in mainstream health care delivery systems. Previous investigators have described chiropractic clinical services in the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, and private health care systems.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 It has been recommended by the Institute of Alternative Futures that the chiropractic profession continue to emphasize integration into mainstream health care to ensure a strong future.11 However, integrating new providers into established health care settings is a difficult task; and the resulting health care structures, processes, and outcomes can vary considerably.11, 12, 13, 14 Although there is some knowledge of the participation of doctors of chiropractic (DCs) in various integrated medical systems, the phenomenon continues to develop and broaden without national coordination. Consequently, a clear description of integrated clinical practice characteristics has not been presented. This lack of baseline knowledge presents an impediment to analyzing and maximizing the value of current integration efforts and supporting further integration.9 Because there are limited opportunities for DCs to train in integrated medical systems, either as students or postgraduates, unmet educational needs may exist among these providers.

Collaboration in practice between medical doctors (MDs) and DCs is growing; thus, it is important to understand how these professions work together successfully and to examine characteristics of current integrated approaches to identify features that can be assessed, modeled, and/or implemented in other settings.8, 9

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess a self-report of participating American Chiropractic Association (ACA) members’ experiences, attitudes, and perceived educational needs regarding practice in mainstream integrated medical settings. The specific aims were to (1) explore group experiences with integrated practice, (2) understand group attitudes toward integrated practice, and (3) identify perceived informational and training needs.

Methods

This project used a descriptive observational survey. The study population included all licensed DCs who were members of the ACA on the study commencement date. Potential subjects were identified through the ACA membership list database, including the General, Family, New Practitioner, Sustaining, International, and Governor’s Advisor Cabinet membership categories. This represented a total of 9691 individuals. Doctors of chiropractics who became ACA members following the start of the study, who were retired, or who were registered as student status were excluded from the study.

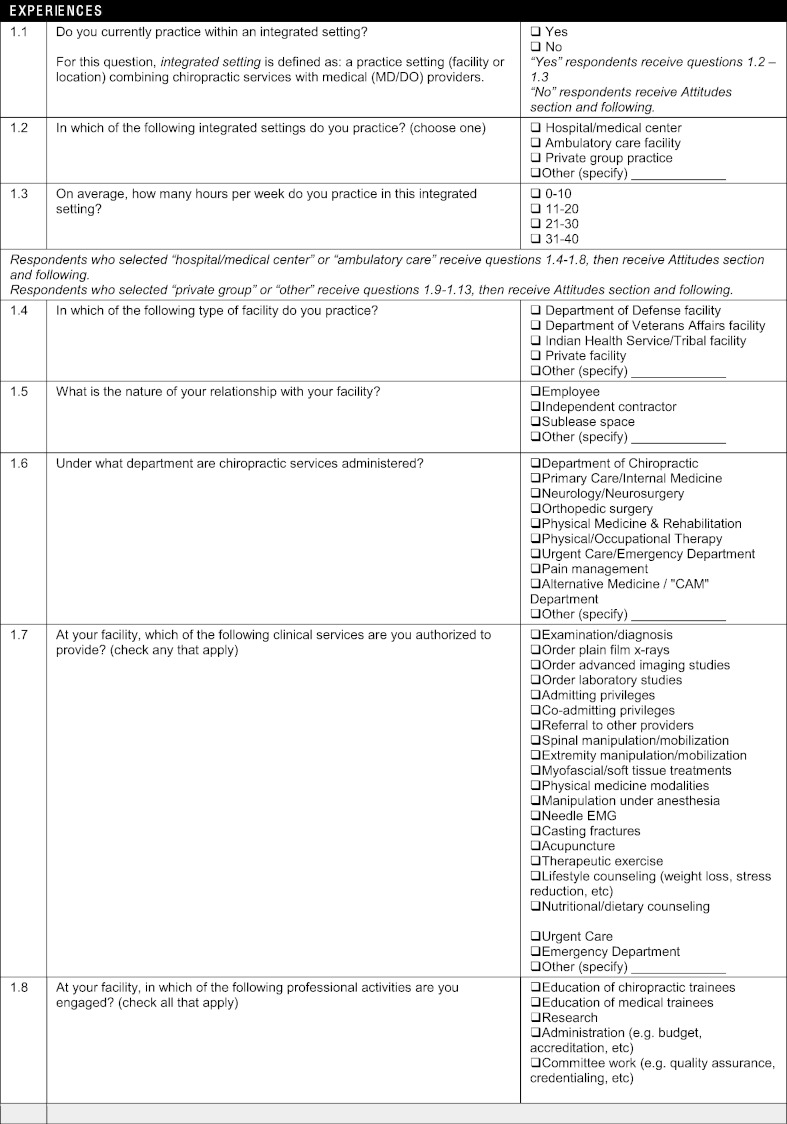

At the beginning of the study, which commenced on November 29, 2011, and ended on December 20, 2011, the e-mail addresses of all ACA members were entered into the Question Pro (questionpro.com) online survey software. This system then sent invitational e-mails to all ACA members. Subjects were asked to complete an electronic survey inquiring about their integrative experiences to date, details about their facilities and practice, their general attitudes towards integration, and educational interests about various clinical services. Subjects were also asked to list their basic demographics, such as age, sex, and time of graduation. For the purpose of this study, we defined integrated practice as a practice setting (facility or location) where DCs and medical (MD/DO) doctors both provide patient care. We did not ask respondents to describe characteristics related to work with any other provider types.

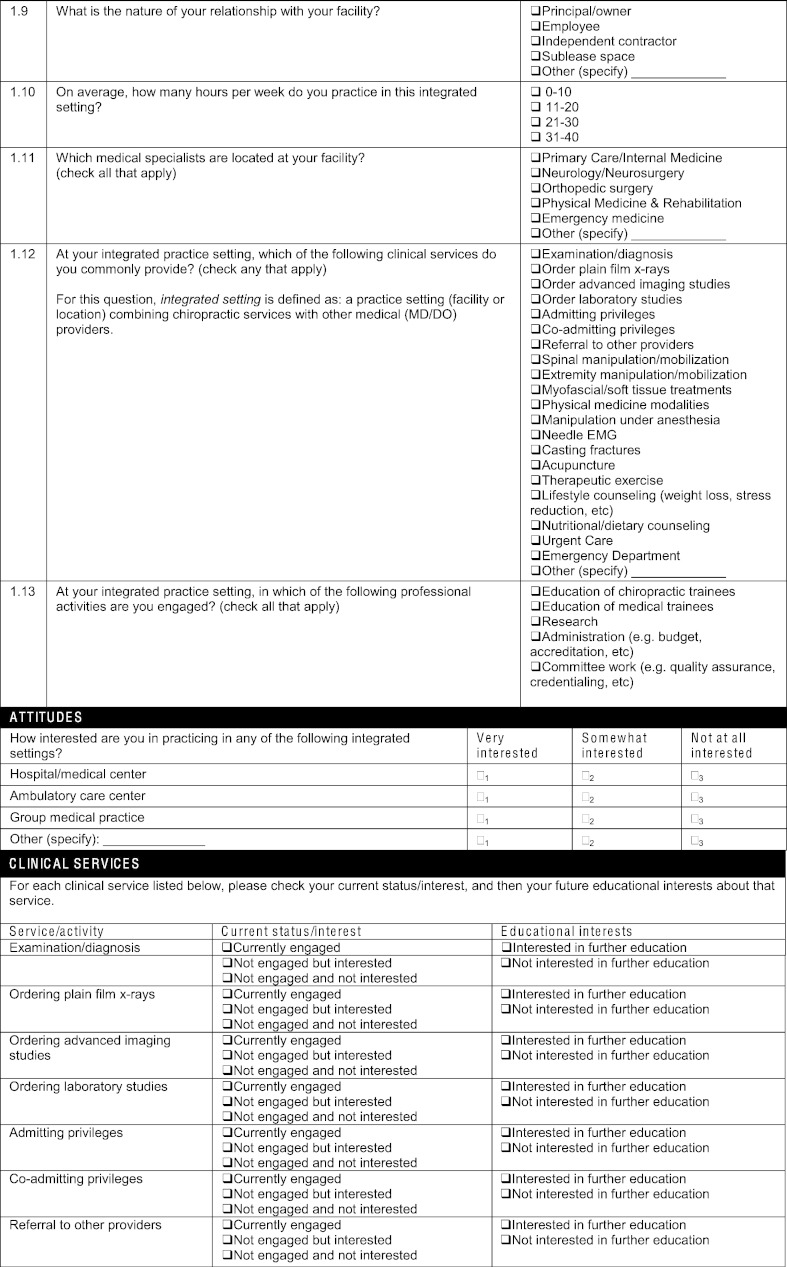

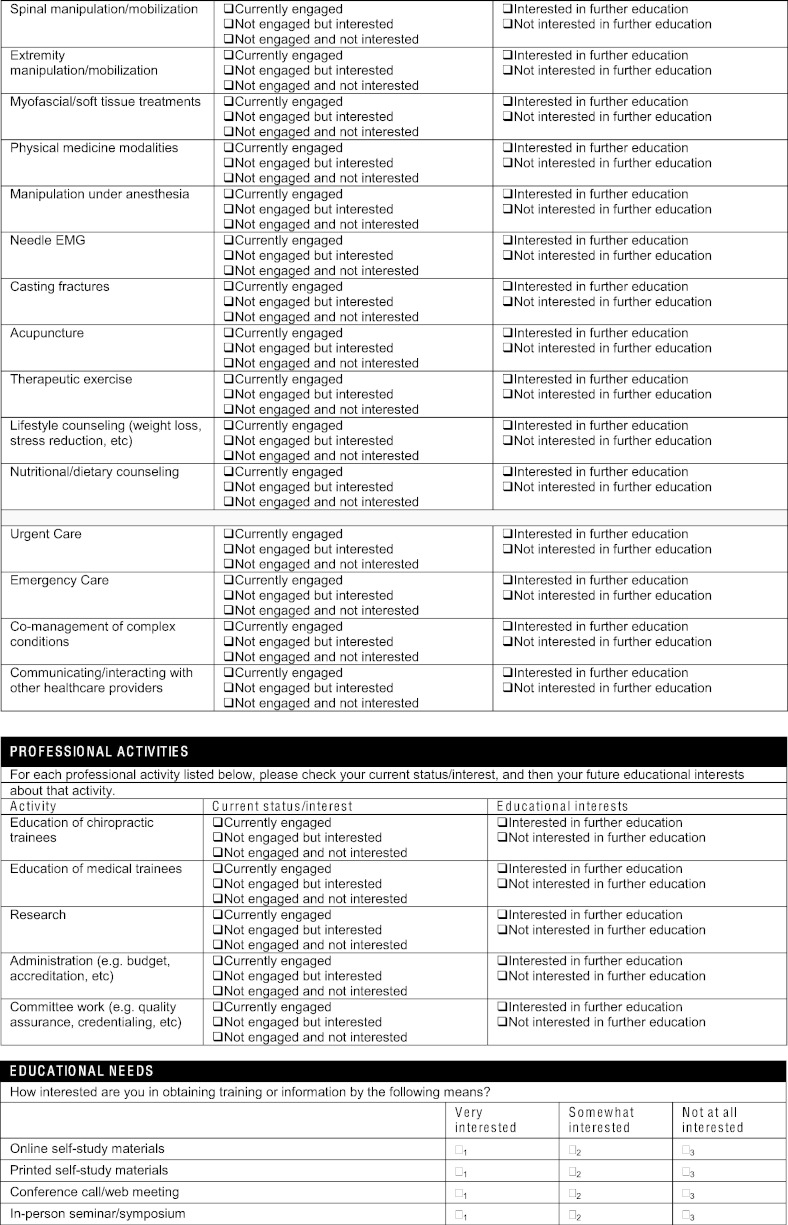

The survey was modeled after previous surveys assessing (1) characteristics of DCs in integrated settings1 and (2) experiences and educational needs of medical physicians.11, 15 Following an iterative process, survey questions were developed by the authors. The survey instrument was pilot tested among a convenience sample of DCs known to the investigators to have experience in integrated practice. Results of pilot testing led to a few minor revisions and suggested that survey questions were clear and the instrument was easy to use and able to be completed in 10 to 15 minutes. The full survey is presented in Appendix A.

The initial survey launch was quickly discovered to have been compromised by respondents from outside of the target population and by instances of duplicate responses from given individuals. This was identified by automated reports in the QuestionPro software. Data collection was thus halted, and the online survey methodology was upgraded to ensure responses only from the individuals to whom the invitational e-mail was sent, while still masking respondent identity (QuestionPro Respondent Anonymity Assurance). The survey was then relaunched with these enhanced electronic survey security features.

Participation reminders were e-mailed on days 7, 14, and 20 to those who had not yet completed the survey and had not indicated that they wished to opt out of further contact. Announcements of the study were additionally disseminated through various ACA member communications including publications in newsletters, Web sites, and announcements on conference calls.

Subjects were informed of the potential risks and benefits of study participation and granted consent electronically. Responses were entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) and analyzed with descriptive statistics. The University of Bridgeport Institutional Review Board chair reviewed this study and gave it exempt status.

Results

Out of the 9691 potential participants, 1435 subjects began the survey, with 293 dropping out before completion. This resulted in 1142 complete respondents, for a response rate of 11.8%. The QuestionPro software anonymously cross-referenced respondents’ e-mail addresses with the ACA member e-mail database and identified no discrepancies or duplicate respondents.

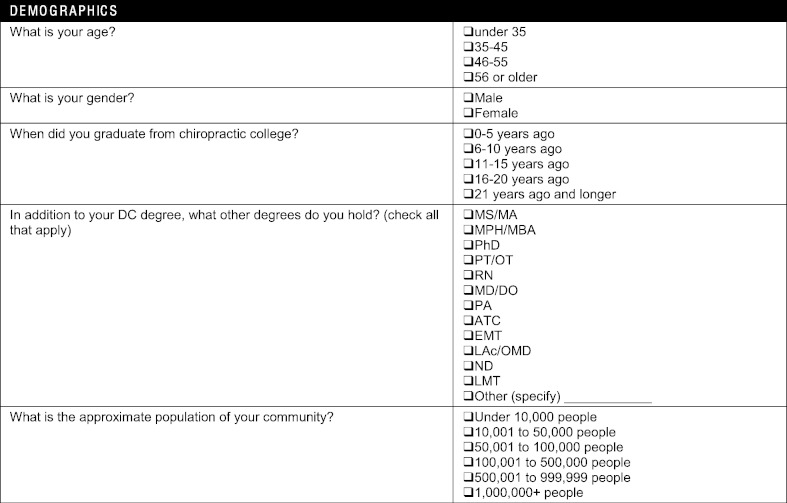

Demographics are reported in Table 1. Most respondents were male and in practice for 21 years or longer. Few respondents had advanced academic degrees or health care degrees other than DC.

Table 1.

All Respondent Demographics (n = 1142)

| Age (y) | < 35 | 21.6% |

| 35-45 | 23.4% | |

| 46-55 | 26.7% | |

| ≥ 56 | 28.3% | |

| Sex | Male | 79.9% |

| Female | 20.1% | |

| Chiropractic college graduation | 0-5 y ago | 19.2% |

| 6-10 y ago | 12.3% | |

| 11-15 y ago | 11.7% | |

| 16-20 y ago | 10.1% | |

| ≥ 21 y ago | 46.7% | |

| Degrees held in addition to DC | BS/BA | 62.8% |

| MS/MA | 12.5% | |

| MPH/MBA | 8.2% | |

| PhD | 6.7% | |

| PT/OT | 2.2% | |

| RN | 1.5% | |

| MD/DO | 1.5% | |

| PA | 1.2% | |

| ATC | 0.8% | |

| EMT | 0.7% | |

| LAc/OMD | 0.5% | |

| ND | 0.4% | |

| LMT | 0.4% | |

| None | 0.4% | |

| Other | 0.1% |

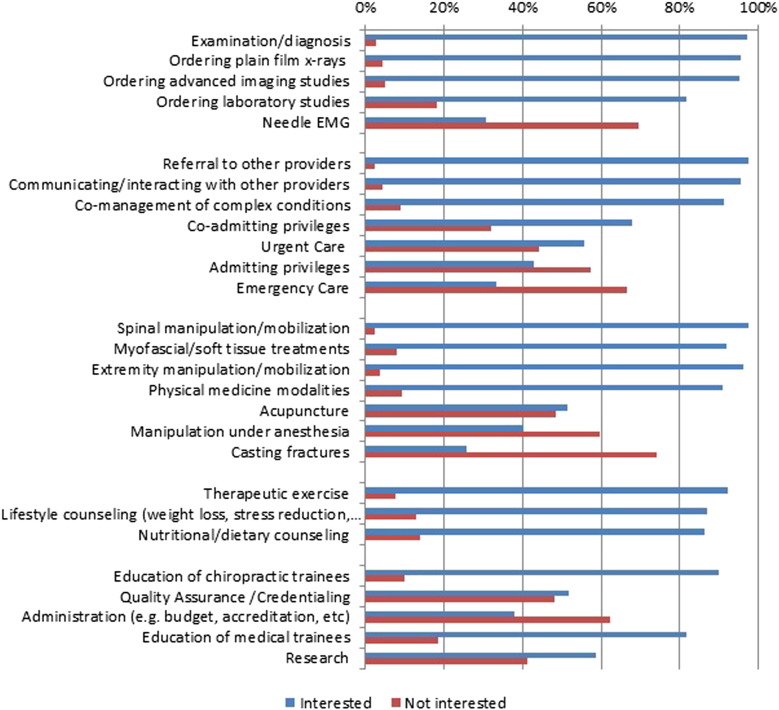

The majority of respondents (n = 1255, 82.9%) did not currently practice in an integrated setting. Within the nonintegrated group, a majority reported interest in delivering a wide range of diagnostic, therapeutic, and case management services and/or participating in professional activities in an integrated setting (Fig 1). A majority reported not being interested in delivering specific clinical services including needle electromyography, emergency care, manipulation under anesthesia, and casting fractures. In regard to professional activities, most of the nonintegrated respondents were interested in educating chiropractic and medical trainees, and less interested in administration.

Fig 1.

For those who were not in integrated settings, the amount of interest in integrated settings. (Color version of figure appears online.)

A minority of respondents (n = 187, 17.1%) reported currently working in integrated settings (Table 2). Of these, 50 (29.1%) reported working in a medical facility (hospital or outpatient) and 137 (70.9%) reported working in a private group practice or other setting (Table 3).

Table 2.

Integrated Respondents’ Characteristics

| All Respondents Practicing in Integrated Settings (n = 187a) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Integrated setting type | Hospital/medical center | 13.4% |

| Ambulatory/outpatient care facility | 15.7% | |

| Private group practice | 59.3% | |

| Other (specify) | 11.6% | |

| Average h/wk practicing in the integrated setting | 0-10 | 21.3% |

| 11-20 | 13.8% | |

| 21-30 | 12.6% | |

| 31 + | 52.3% | |

| Hospital/Medical Center/Ambulatory or Outpatient Respondents (n = 50) | ||

| Facility type | Private sector | 46.0% |

| Other | 24.0% | |

| Department of Defense | 16.0% | |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | 14.0% | |

| Business relationship | Employee | 44.0% |

| Independent contractor | 30.0% | |

| Sublease space | 12.0% | |

| Other | 14.0% | |

| Private Group Practice/Other Respondents (n = 137a) | ||

| Business relationship | Principal/owner | 54.8% |

| Employee | 20.9% | |

| Sublease space | 11.3% | |

| Independent contractor | 9.6% | |

| Other | 3.5% | |

Not all questions were answered by all respondents.

Table 3.

Hospital/Ambulatory Care Facility Respondents (n = 50)

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you receive referrals from MDs/DOs at your facility? | 2.0% | 7.8% | 9.8% | 45.1% | 35.3% |

| How often do you send referrals to MDs/DOs at your facility? | 5.9% | 3.9% | 29.4% | 52.9% | 7.8% |

| How often do you have discussions with MDs/DOs at your facility to make shared case management decisions? | 2.0% | 21.6% | 33.3% | 37.3% | 5.9% |

| How often do you include your clinical documentation into the same medical record used by MDs/DOs at your facility? | 17.6% | 11.8% | 2.0% | 9.8% | 58.8% |

DO, doctor of osteopathy; MD, medical doctor.

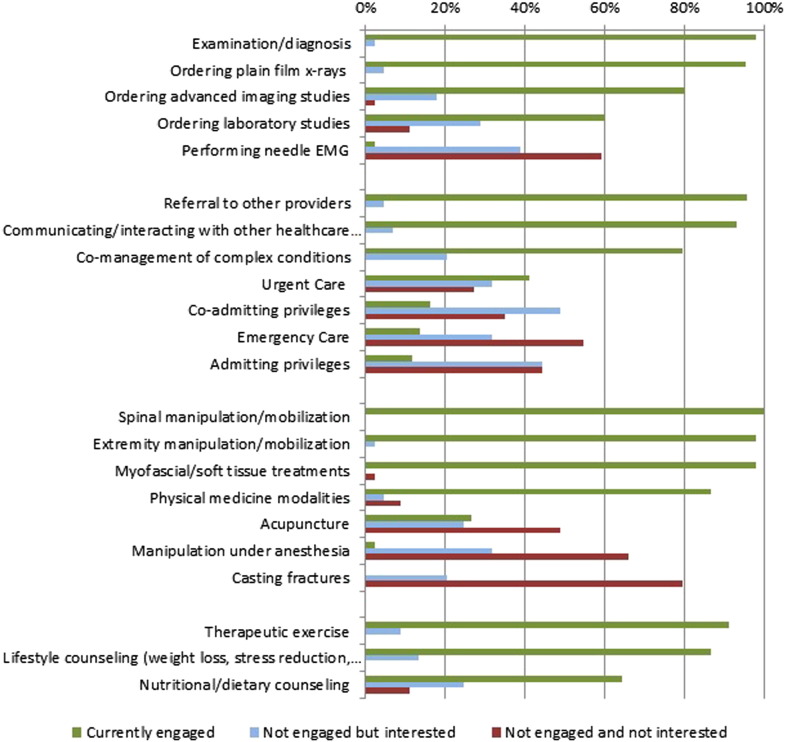

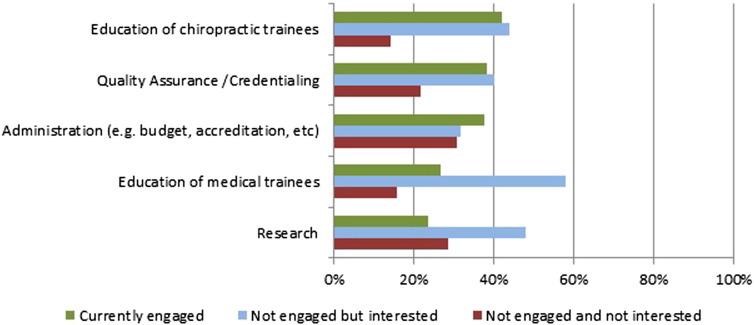

Among the integrated respondents, similar to their nonintegrated counterparts, the majority expressed interest in providing a wide range of diagnostic, therapeutic, and case management services and similar disinterest in needle electromyography, emergency care, manipulation under anesthesia, and casting fractures. The integrative group additionally reported a disinterest in the administration of clinical acupuncture (Fig 2). The subgroup of 50 medical facility–based integrated practice respondents reported varying degrees of engagement/interest in key professional activities (Fig 3). The group was most commonly engaged in education of chiropractic trainees and least engaged in research. This group also reported interest in providing education to medical trainees and participating in research.

Fig 2.

For those who were in integrated settings, the amount of engagement and interest. (Color version of figure appears online.)

Fig 3.

For the 50 medical facility–based integrated practice respondents, the amount of engagement/interest in key professional activities. (Color version of figure appears online.)

Lastly, the top 5 responses in regard to general clinical educational interests were reported similarly for both groups. The content areas with the highest concordance between both nonintegrated and integrated respondents were examination/diagnosis (87.6% and 82.6%, respectively), ordering laboratory studies (79.4% and 78.5%), therapeutic exercise (81.9% and 83.5%), comanagement of complex cases (86.2% and 83.3%), and communicating/interacting with other health care providers (85.9% and 78.5%).

Discussion

Chiropractic integration into health care settings can facilitate interprofessional collaboration (IPC),5 the phenomenon of varying medical professionals working together toward a common goal of more rounded and cohesive care for their patients. In general, IPC appears to be increasing and corresponds with improved patient outcomes.16, 17 When chiropractic services are integrated into medical systems, the results may include improved patient outcomes, decreased use of other health care services, greater likelihood of adherence to clinical practice guidelines, satisfaction among stakeholders, and decreased health care costs.7, 18, 19 Barriers to chiropractic integration into medical settings may exist. One barrier may be the lack of interprofessional education. Interprofessional education is a natural precursor to IPC and can be used as a way to improve how professionals work together, thus enhancing patient care.17, 20, 21

There have been increasing awareness and interest in the use of chiropractic services within integrated medical settings, and physician interest is widely documented in many Western countries. In a 2001 survey of Midwestern medical physicians, 54% indicated the desire to offer chiropractic service for their patients, 54% indicated that they have previously referred a patient to a DC, and 17% had themselves received the therapy.22 In an English survey study of hospital doctors from South West Thames Regional Health Authority and medical students from St George's Hospital Medical School, Perkin et al22 found that medical students were generally less informed about alternative therapies when compared with medical doctors; however, they are more enthusiastic about offering them to future patients. This supports an increasing demand for and acceptance of chiropractic within mainstream allopathic medicine. A large proportion of doctors revealed making referrals to practitioners for alternative medicine without knowledge of provider’s qualifications and felt that an introduction to alternative medicine should be taught as a topic course in medical school.23

The results of our study provide a baseline description of ACA member experiences, attitudes, and perceived educational needs regarding practice in integrated medical settings. The demographics of all study respondents were similar to those previously reported for US DCs in the National Board of Examiner survey in terms of sex, degrees held in addition to DC, and years in practice.24 Our survey findings also show comparable engagement in patient treatment approaches. These were seen in examination, diagnosis, spinal and extremity manipulative therapies, myofascial treatments, therapeutic exercise prescription, and lifestyle/nutritional counseling. One notable discrepancy seen was a small percentage of US DCs (2.5%) identifying themselves as the sole providers in treating fracture, whereas none of our survey respondents noted current engagement in casting fractures.24 Previous data show that the typical US DC is more likely to send referrals to MDs rather than receive referrals from them.23 The percentage of our respondents who actively refer patients to other practitioners was congruent with national reports.24 Our study suggests that DCs practicing in an integrated environment are more likely to receive patient referrals from MDs than DCs not practicing in integrated settings. Furthermore, 4.4% of our survey respondents reported holding hospital privileges, similar to the 3.6% of all US DCs, and appear to make and receive an even higher number of referrals when compared nationally.21 The authors opine that this is most likely due to the comfort level for patient exchange in a collaborative environment whereby the medical physician may have more knowledge about and confidence in the given DC’s clinical competence.

We anticipated that the respondents who categorized themselves as working in hospital or ambulatory care settings would exhibit a varying degree of interprofessional collaboration characteristics, and our results supported this. Almost a third of these respondents reported that they never or rarely included their clinical documentation in the same medical record as the facility’s MD/DO physicians, and about 10% reported that they never or rarely received referrals from the facility’s MD/DO physicians. This suggests that the addition of DCs into integrated medical facilities may in some instances result in processes of care that are still separate and/or fragmented.

Understanding the experiences and attitudes of DCs toward allopathic integration can be useful for planning future integration efforts. Our survey indicates that there is a high interest by DCs to become involved within an integrated medical settings, specifically as a musculoskeletal specialist. These results can help to inform the strategies of chiropractic educational and professional institutions. It is essential to determine DC’s values within integrated practice and identify training disparities among them to better develop educational and/or advocacy strategies aimed at advancing chiropractic integration. Greater integration will create more opportunity and is necessary in providing well-rounded health care. 9, 11

Limitations

Our results are subject to limitations inherent with survey methodology including respondent self-selection, recall and/or reporting bias, and constraints of closed-ended questions. This particular survey was not externally validated; however it was modeled off of previously validated studies. Our population consisted of ACA member DCs; therefore, the results of this work cannot be extrapolated to other DCs. Our operational definition of integrated practice was intentionally limited to only include interactions with MD/DO physicians; thus, our results cannot be generalized to integration with other provider types. This study was also limited by a response rate of 11.7%; thus, it is not certain if these findings represent the prevailing attitudes of the ACA members. Potential reasons for the low response rate may be that some subjects were discouraged or confused by the repeat launch of the survey or found completion too time consuming. Nevertheless, recent work has shown that survey research with lower response rates can be as accurate as those with higher rates.25, 26 Further investigation is needed to better understand the integration of chiropractic services into mainstream medical settings. The results of this study may help inform such work and support the development of education and advocacy strategies aimed at advancing chiropractic integration to improve patient care.13

Conclusion

This study describes the self-reported experiences of ACA member DCs practicing in integrated settings with MD/DO physicians and identifies their attitudes toward future integration. These findings present self-reported unmet educational needs for integration.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources were reported for this study. Leo Bronston is the Chairman of the ACA Integrated Practice Committee, the ACA Current Procedural Terminology Advisor, Member Health Care Professionals Advisory Committee Review Board , and Vice President of ACA Council of Delegates. Anthony Lisi is the Director of the Chiropractic Program for the Veterans Health Administration. Kevin Donovan is a member of the Rhode Island Board of Chiropractic Examiners and Rhode Island Delegate to the ACA.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument for Project: A Survey of Chiropractors' Experiences, Attitudes, and Educational Needs Regarding Integrated Clinical Practice

ACA Member Survey

Investigators

xxxx

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to assess chiropractors' experiences, attitudes, and educational needs regarding practice in mainstream medical settings.

Your Involvement

You are asked to complete the following electronic survey, which should take about 15 to 20 minutes. The survey includes questions about your experiences, attitudes, and educational needs regarding integrated clinical practice. We also will ask for some demographic information (eg, age, training) so that we can describe general traits of DCs who participate in the study.

Benefits of this Study

There are no specific benefits for an individual participating in this study. The study may reveal information that can assist in creating professional development strategies for providers.

Risks or Discomforts

No risks or discomforts are anticipated from taking part in this study. If you feel uncomfortable with a question, you can skip that question or withdraw from the study altogether. If you decide to quit at any time before you have finished the questionnaire, your answers will not be recorded.

Confidentiality

Your responses will be anonymous and confidential. We will not know your IP address when you respond to this online survey.

Decision to Quit at Any Time

Your participation is voluntary; you are free to withdraw your participation from this study at any time. If you do not want to continue, you can simply leave this Web site. If you do not click on the "submit" button at the end of the survey, your answers and participation will not be recorded. You also may choose to skip any questions that you do not wish to answer.

How the Findings Will Be Used

The results of the study will be used for scholarly purposes only. The results from the study will be presented in educational settings and at professional conferences, and the results might be published in a professional journal.

Contact Information

If you have concerns or questions about this study, please contact xxxx.

By beginning the survey, you acknowledge that you have read this information and agree to participate in this research, with the knowledge that you are free to withdraw your participation at any time without penalty.

Integrated Practice Survey

Please answer the following questionnaire by checking the box that best applies to you for each statement. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers. It is important that you respond to each statement.

References

- 1.Lisi A.J., Goertz C., Lawrence D.J., Satyanarayana P. Characteristics of veteran’s health administration chiropractors and chiropractic clinics. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(8):997–1002. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green B.N., Johnson C.D., Lisi A.J., Tucker J. Chiropractic practice in military and veteran’s health care: the state of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53(3):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn A.S., Green B.N., Gilford S. An analysis of the integration of chiropractic services within the United States military and veterans' health care systems. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg C.K., Green B., Moore J. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boon H.S., Mior S.A., Barnsley J., Ashbury F.D., Haig R. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional health care teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson C. Health care transitions: a review of integrated, integrative, and integration concepts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lisi A.J., Khorsan R., Smith M.M., Mittman B.S. Variations in the implementation and characteristics of chiropractic services in VA. Med Care. 2014;52(Suppl. 5):S97–S104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner M.J., Birmingham M., Aker P. Developing integrative primary healthcare delivery: adding a chiropractor to the team. Explore (NY) 2008;4(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branson R.A. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carucci M.J., Lisi A.J. CAM services provided at select integrative medicine centers: what do their websites tell us? Top Integr Health Care. 2010;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Institute for Alternative Futures. The Institute for Alternative Futures; Alexandria (Va): 2005. The future of chiropractic revisited: 2005-2015. Web. 20 Dec 2014. < http://www.altfutures.com>. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson P.D., Parker L.E., Coulter I.D. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants as primary care providers in institutional settings. Inquiry. 1998–1999;35(4):432–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen A.H., Martin S.A., Soden R., Meyer M., Liss S., Hodson W.L. Integrating ophthalmological and optometric services in a VA hospital program. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(4):429–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang P., Yano E., Lee M., Chang B., Rubenstein L. Variations in nurse practitioner use in veterans affairs primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4):887–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanGeest J.B., Cummins D.S. White Paper Report 3. National Patient Safety Foundation; 2003. An educational needs assessment for improving patient safety: results of a national study of physicians and nurses. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwarenstein M., Goldman J., Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bednarz E.M., Lisi A.J. A survey of interprofessional education in chiropractic continuing education in the United States. J Chiropr Educ. 2014;28(2):152–156. doi: 10.7899/JCE-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen H., Wright M., Craig T., Mardekian J., Cheung R., Sanchez R. Tracking low back problems in a major self-insured workforce: toward improvement in the patient's journey. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(6):604–620. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammick M., Freeth D., Koppel I., Reeves S., Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):735–751. doi: 10.1080/01421590701682576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves S., Perrier L., Goldman J., Freeth D., Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD002213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rooney B., Fiocco G., Hughes P., Halter S. Provider attitudes and use of alternative medicine in a midwestern medical practice in 2001. WMJ. 2001;100(7):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perkin M.R., Pearcy R.M., Fraser J.S. A comparison of the attitudes shown by general practitioners, hospital doctors and medical students towards alternative medicine. J R Soc Med. 1994;87(9):523–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visser P.S., Krosnick J.A., Marquette J., Curtin M. Mail surveys for election forecasting? An evaluation of the Colombia Dispatch Poll. Public Opin Q. 1996;60:181–227. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2014. Practice analysis of chiropractic 2015. Web. 11 May 2015. < http://www.nbce.org/practiceanalysis/>. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeter S., Kennedy C., Dimock M., Best J., Craighil P. Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2006;70(5):759–779. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen M.G., Kollasch M.W., Hyland J.K. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; Greeley CO: 2010. Practice analysis of chiropractic 2010. [Google Scholar]