TEXT

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a physiologic phenomenon occurring occasional ly in every human being, especially during the postprandial period. Regurgitation occurs daily in almost 70% of 4-month-old infants and about 25% of their parents do consider regurgitation as “a problem”[1,2]. Indeed, it seems against logic that the normal function of the stomach would reflux ingested material back into the esophagus. Whether all infants presenting with regurgitation need drug treatment is a controversial question.

DEFINITION

GER is best defined as the involuntary passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. The origin of the gastric contents can vary from saliva, ingested food and drinks, gastric, pancreatic to biliary secretions. Vomiting is used as a synonym for emesis, and means that the refluxed material comes out of the mouth “with a certain degree of strength” or “more or less vigorously”, usually involuntary and with sensation of nausea. Regurgitation is used if the reflux dribbles effortlessly into or out of the mouth, and is mostly restricted to infancy (from birth to 12 months)[2,3]. Vomiting can be regarded as the top of the iceberg in its relation to the incidence of GER-episodes.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Symptoms of reflux may be observed in normal individuals, but in those cases they are only found incidentally, and they occur more often and are more severe in pathological situations. The usual manifestations and unusual presentations of GER (-disease) are listed in Table 1[3]. Infants with a Roviralta Astoul syndrome have pyloric stenosis associated with hiatal hernia.

Table 1.

Symptoms of GER (-disease)

| Usual manifestations | Symptoms possibly related to complications of GER* |

| Specific manifestations | |

| Regurgitation | Symptoms related to anaemia (iron deficiency anaemia) |

| Nausea | Haematemesis and melaena |

| Vomiting | Dysphagia (as a symptom of oesophagitis or due to stricture formation) |

| Weight loss and/or failure to thrive | |

| Epigastric or retrosternal pain | |

| “Non-cardiac angina-like” chest pain | |

| Pyrosis or heartburn, pharyngeal burning | |

| Belching, postprandial fullness | |

| Irritable oesophagus | |

| General irritability (infants) | |

| Unusual presentations | |

| GER related to chronic respiratory disease (bronchitis, asthma, laryngitis, pharyngitis, etc.) | |

| Sandifer Sutcliffe syndrome | |

| Rumination | |

| Apnea, apparent life threatening event and sudden infant death syndrome | |

| Associated to congenital and/or central nervous system abnormalities | |

| Intracranial tumors, cerebral palsy, psychomotory retardation | |

A number of these symptoms may also be caused by other mechanisms.

Emesis and regurgitation are the most common symptoms of “primary” GER-disease but they are also a manifestation of many other diseases[2,3]. Such “secondary” GER-disease can be caused by infections (e.g. urinary tract infection, gastroenteritis, etc.), metabolic disorders and especially food allergy[2,4]. On clinical grounds, “secondary” reflux may be difficult to separate from “primary” reflux. “Secondary” reflux is the result of a stimulation of the vomiting center in the dorsolateral reticular formation by all kinds of efferent and afferent impulses (visual stimuli, the olfactory epithelium, labyrinths, pharynx, gastrointestinal and urinary tracts, testes, etc.). “Secondary” GER is not further discussed in this paper. It is obvious that treatment of “primary” GER-disease should focus on motility and/or acid suppression, and that therapeutic management of “secondary” GER should focus on the etiologic phenomenon.

PATIENT GROUPS

The following approach is a generalization that, like all generalizations, may need to be modified for an individual patient[3]. First, interest is focused on uncomplicated GER, mostly restricted to regurgitating infants. In a second paragraph, a proposal is made for optimal management in patients with complicated GER disease (symptoms suggestive of esophagitis). There is a continuum between normal infants with regurgitation and GER and those with severe GER which leads to disability, discomfort or impairment of function. An approach is proposed for the management of patients with atypical presentations of GER.

Group 1. Uncomplicated reflux: regurgitation

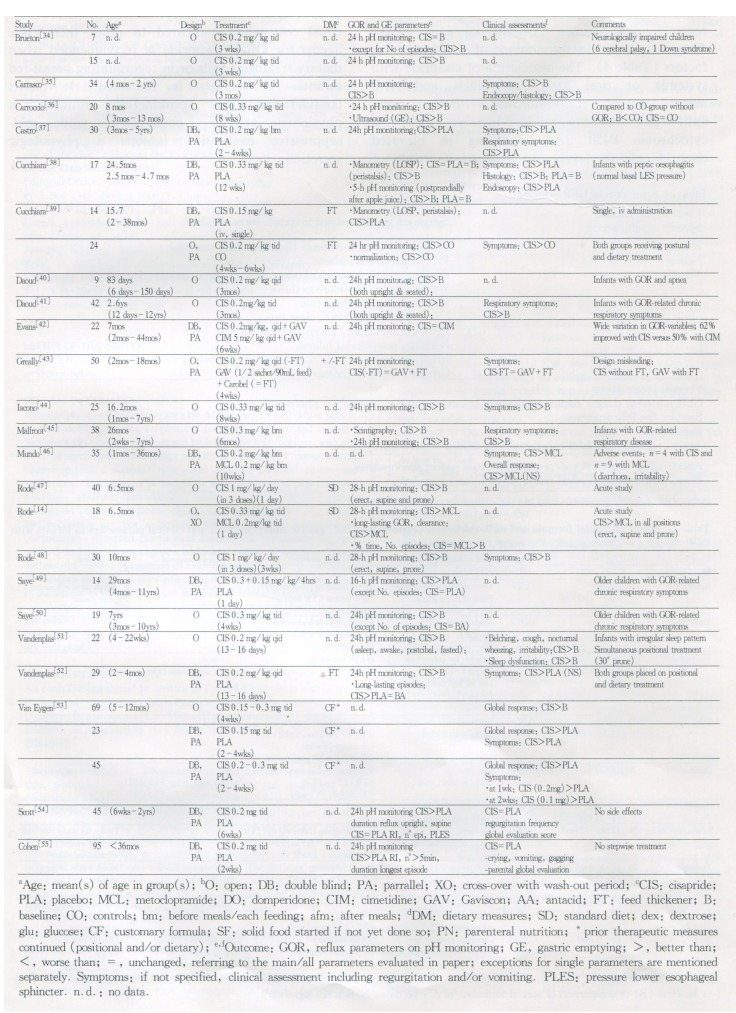

Regurgitation may occur in children who are normal and do not have complaints of GER-disease such as nutritional deficits, esophagitis, blood loss, structures, apnea or airway manifestations. There is no difference in the incidence of regurgitation in breast-fed and formula-fed infants[5]. But, infants with uncomplicated regurgitation are frequently perceived by their parents as having a problem, and their parents often seek medical attention. The approach of the infants presenting with “excessive” regurgitation and of their parents has to be well balanced, and cannot be subject to overconcern or disregard. This group of patients are mostly restricted to infants younger than 6 months, or at the most 12 months[1,3,5]. A careful history, observation of feeding, and physical examination of the infant are mandatory. Although the following statement has not been thoroughly validated because randomization is not possible (only anxious parents seek medical help), it is rather unlikely that regurgitation will result in severe GER-disease. The effect of parental reassurance is suggested by m any placebo-controlled studies showing a similar efficacy of placebo and the tested intervention[6,7]. If simple reassurance fails, dietary intervention is recommended, including restriction of the volume in clearly overfed babies, and change to a thickened “anti-regurgitation” formula[5-7]. Larger food volumes and high osmolality increase the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations and drifts to almost undetectable levels of LES-pres sure[8]. Both are well known pathophysiologic mechanisms provoking GER in infants, which might also explain why feed thickeners sometimes aggravate their symptoms. The thickening of the formula, with starch (e.g. from rice, potato, etc.) or non-nutritive thickeners (bean gum), decreases the frequency and volume of regurgitation[5-7,9] (Figure 1). Some of these “anti-regurgitation” formulae are casein-predominant (casein/whey 80/20%) to optimize the curd formation, while others contain 100% whey (hydrolysate) enhancing gastric emptying. However, the effect of these formulae on GER-parameters, when measured with pH monitoring or scintigraphy are not convincing: most studies show that reflux parameters can improve, remain unchanged or worsen in approximately one third of infants for each possibility[6,7,10]. In other words, “anti regurgitation” formulae do what they claim to do: they reduce regurgitation[5-7] but they do not influence (acid) GER. Thickened formula also increases the duration of sleep[5,6]. Therefore, anti-regurgitation formula should be considered as the first step in medical treatment, and should only be available on prescription[3,5-7]. Anti-regurgitation formula and/or dietary intervention in general should be nutritionally safe[34]. However, regurgitation may be par t of the spectrum of symptom(s) of GER-disease, necessitating an effective intervention to decrease the number and intensity of the GER-episodes. In this situation, an intervention that is limited to alleviate the presenting manifestation (regurgitation) will not suffice. Differentiation between regurgitation and (pathologic) vomiting can be difficult on clinical grounds, since there is a continuum between both conditions[5]. It is not always obvious in this patient group whether the parental complaints relate to physiological regurgitation or whether they suggest GER-disease. In practice, feed thickeners or special formula can not be given to breast-fed infants. Therefore, if the infant is breast-fed and/or in case of GER-disease, drug treatment with prokinetics should be considered prior to diagnostic procedures.

Figure 1.

Effect of special formula and milk-thickening products on GOR, gastric emptying (GE) and clinical parameters in infants with GOR disease (=: unchanged, <: worse, >: better).

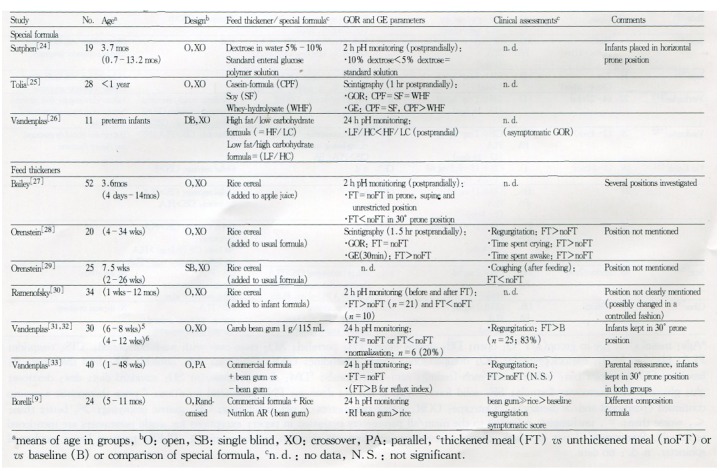

It seems reasonable to add medication such as prokinetics to the treatment of cases that are refractory to dietary intervention. They reduce regurgitation via their effects on the LES pressure and motility, esophageal peristalsis and gastric emptying[11]. For this reason, they interact with the pathophysiologic mechanisms of regurgitations in infants, which are related to immaturity of the gastroesophageal motor function[12]. A link between cisapride and increased salivary secretion has been demonstrated[13]. This indicates that, in combination with increased peristalsis and hence esophageal clearance, cisapride therapy may protect the esophagus via salivary components, such as bicarbonate and non-bicarbonate buffers, thus facilitating symptomatic relief and healing of the esophagus. Metoclopramide and domperidone have anti-emetic properties due to their dopamine-receptor blocking activity, whereas cisapride is a prokinetic acting through indirect release of acetylcholine in the myenteric plexus[11]. Although all three agents have been shown to reduce regurgitation in infants[6,7], data for cisapride are more convincing (Figure 2, Table 2). When compared to metoclopramide, cisapride appears to be more effective in reducing p H-metric[14], has a faster onset of action[15], and is better tolerated[15]. Cisapride has also been shown to heal oesophagitis[16]. Domperidone has been reported to be as effective as metoclopramide[17] (less effective than cisapride). Extrapyramidal reactions and increased prolactine levels are effects related to the dopamine-receptor blocking activity o f these drugs. In case of cisapride, which is devoid of dopamine- blocking properties at therapeutic doses, the most common adverse effects are transient diarrhea and colic (in about 2%)[11,18]. The isolated reports of more serious adverse reactions, i.e., side-effects on the central nervous system, including extrapyramidal reactions and seizures (in epileptic patients), cholestasis (in extreme prematures) and cardiac interactions. Indeed, cisapride, which is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4, has the potential to prolong the QT-interval[18]. However, an extensive review of the literature resulted in reassuring safety consensus statements[18].To date, serious cardiac adverse reactions have not been reported in patients treated with a dosage within the recommended regimen (0.8 mg/kg daily, max. 40 mg/day) and in the absence of additional risk factors (Table 2). The association of cisapride with systemic or oral azole antifungals and with macrolides is contraindicated. Both azole-antif ungals and macrolides interact with the cytochrome P450 3A4, resulting in elevated cisapride plasma levels. In view of its mode of action, efficacy and safety, as well as its lower or equal cost when compared to other therapeutic agents for GER, cisapride is recommended when dietary treatment fails or in regurgitating breast-fed infants, if therapy is indicated. It merits consideration that prokinetics stimulate a physiologic activity (peristalsis), while acid-suppressive medication inhibit s a physiologic secretion.

Figure 2.

Effects of cisapride (CIS) on GOR disease in infants.

Table 2.

Contraindications and risk factors for use of cisapride

| Contraindications to cisapride administ ration in pediatric patients |

| -Combination with medication also known to prolong the QT interval or potent CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as astemizole, fluconazole, |

| itraconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, eythromycin, clarithromycin, troleandomycin, nefazodone, indinavir, ritonavir, josamycin, |

| diphemanil, terfaridine. |

| -Use of the above medications by a breast-feeding mother, as secretion i n mother's milk of most of these drugs is unknown. |

| -Known hypersensitivity to cisapride. |

| -Known congenital long QT syndrome or known idiopathic QT prolongation. |

| Precautions for cisapride administration in pediatric patients |

| -Prematurity (a starting dose of 0.1 mg/kg, 4 times daily may be used, although 0.2 mg/kg is also for prematures the normal dose) |

| -Hepatic or renal failure (particularly when on chronic dialysis). In these cases, it is recommended to start with 50% of the |

| recommended dose. |

| -Uncorrected electrolyte disturbances (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocal cemia), as may occur in prematures, |

| in severe diarrhea, in treatment with potassium-wasting diuretics such as furosemide or acetazolamide. |

| -History of significant cardiac disease including serious ventricular arrhythmia, second or third degree antrioventricular block, congestive heart failure or ischaemic |

| heart disease, QT prolongation associated with diabetes mellitus. |

| -History of sudden infant death in a sibling, and/or history of a “serious ” apparent life threatening event in the infant or a sibling. |

| -Intracranial abnormalities, such as encephalitis or haemorrhage, grape fruit juice. |

In the non-breast-fed infant, a change to a (thickened) hydrolysate or amino- acid formula should be considered, if regurgitation is resistant to a thickened formula with normal proteins and to prokinetics, since protein allergy may present as therapy-resistant GER-disease.

Non-drug treatment (positional therapy, dietary advice) can help convince the parents of the physiologic nature of the regurgitations[3]. The influence of position on the incidence and duration of GER episodes has been demonstrated in adults, children and infants both in asymptomatic healthy controls and symptomatic individuals. The 30° prone reversed Trendelenburg position is nowadays generally recommended and accepted as an essential element of treatment[3,6,7]. However, positional treatment is in practice very difficult to apply correctly in infants and rather unfriendly to the babies, since they have to be tied up in their beds or cot to prevent them from sliding down under the blankets, since an angle of 30° has to be achieved and maintained. The ample evidence that the prone sleeping position is a risk factor in sudden infant death, independent of overheating, smoking or way of feeding[6]. Positional treatment remains, in view of its efficacy, a valid “adjuvant” treatment in patients not responding to other therapeutic approaches or beyond the age of sudden infant death[6].

Group 2. Overt GER-disease

Patients in this group did not either respond to the previous approach (parental reassurance, dietary treatment and prokinetics) or present with symptoms suggesting esophagitis (hematemesis, retrosternal, epigastric pain, etc.) (Table 1). Therefore, an underlying anatomic malformation should be excluded, and endoscopy is the investigation of choice[3,19]. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in infants and children should only be performed by experienced and qualified physicians[19]. If the question being asked is restricted to underlying anatomic malformations, upper gastrointestinal series can be considered[19]. If symptoms and/or the esophagitis do not improve despite adequate medical treatment and controlled compliance, upper gastrointestinal series should be performed to exclude anatomical problems such as gastric volvulus, intestinal malrotation, annular pancreas, etc.

Antacids are reported to be effective in the treatment of GER[6], although experience is limited in infants. Their capacity to buffer gastric acid is strongly influenced by the time of administration[20], and requires multiple doses. Gaviscon (a combination of an antacid and sodium salt of alginic acid) is as effective as antacids and appears to be relatively safe, since only a limited number of side effects have been reported. Occasional formation of large bezoar-like masses of agglutinated intragastric material has been reported with the use of Gaviscon, and it can increase the sodium content of the feeds to an undesirable degree especially in preterm infants (1 g Gaviscon-powder contains 46 mg sodium, and the suspension contains twice this amount of sodium)[6].

H2-receptor antagonists, of which ranitidine is by far the mostly used, are effective in healing reflux esophagitis in infants and children[6]. Many new drugs have been developed (misoprostil, sucralfate, omeprazole, etc.). Of these, the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been studied best, although experience in infants and children is limited[21]. PPIs are effective in supp ressing the acidity in patients with gastric stress ulcer (s) and also in neurolo gically impaired children. Even in patients with circular esophageal ulcerations , recent experience suggests that PPIs should be given a chance prior to surgery[21]. Omeprazole is known to be effective in patients with severe esophagitis refractory to H2 blockers[21]. Sucralfate was shown to be as effective as cimetidine for esophagitis in children[22].

Immediate or early surgery is rarely indicated in life threatening conditions where medical management will be of no benefit. Surgery can be life-saving in severely affected patients (notably the neurologically impaired children with recur rent and life-threatening aspiration, etc.). Prior to surgery, a full diagnostic work-up including upper gastrointestinal series, endoscopy, pH monitoring, eventually completed with manometry and gastric emptying studies is recommended.

Group 3. Patients with unusual presentations of GER

The most obvious difference between this patient group and groups 1 and 2, is that this patient group does not present with emesis and regurgitation (Table 1). Since these patients do not vomit, GER-disease is “occult”. Before considering GER as a cause of the symptoms, classic causes of the manifestations need to be excluded, such as allergy in a wheezing patient, tuberculosis in a patient with chronic cough, etc.

If GER-disease is suspected, pH monitoring of long duration (18-24 h) is the investigation of choice. In this group of patients, pH monitoring may need to be performed in simultaneous combination with other investigations in order to relate pH changes to events (e.g. polysomnography in the infants presenting with an apparent life threatening event). In patients suspected of pulmonary aspiration, a scintigraphy might prove the association (although a negative scintigraphy does not exclude reflux related aspiration, and the therapeutic approach will be identical).

If pH monitoring is abnormal or if events are clearly related to pH changes, prokinetics, eventually in combination with H2 receptor antagonists or PPIs, are indicated[19,21]. In this group, repeat pH monitoring under treatment conditions in combination with a clinical follow-up is mandatory. Depending on the unusual presentation, treatment can be stopped after 6 to 12 months, since a possible mechanism for GER in association with unusual manifestations may be self-perpetuating GER[23]. Once reflux occurs, acid gastric contents containing pepsin and sometimes bile comes into contact with the esophageal mucosa, which increases the esophageal permeability to acid and makes the esophageal mucosa much more susceptible to inflammatory changes. Esophageal inflammation, even restricted to the lower esophagus, impairs LES pressure and function, and favors GER[23].

Severely neurologically impaired children

The vast majority of neurologically impaired children suffer from severe GER-disease. Most of these children are under specialized follow-up, and only brief recommendations will be given here. The pathophysiological mechanism of GER-disease in these children is particularly multifactorial: the neurological disease itself (which might cause delayed esophageal clearance and delayed gastric emptying), the fact that most of these children are bedridden (gravity improves esophageal clearance), many are constipated (which increases abdominal pressure and favors GER), etc.

CONCLUSIONS

The diagnostic approach of GER (-disease) in infants and children principally depends on its presenting features. Infants with typical symptoms of uncomplicated GER (the majority of regurgitating babies) should be treated without prior investigations. Endoscopy, in specialized centers, is recommended if esophagitis is suspected. Long-term esophageal pH monitoring is the investigation of choice and occupies a central position in the diagnostic approach of the patient suspected of unusual or atypical presentations of GER-disease (“occult” GER-disease). Non-drug treatment (the importance of parental reassurance cannot be stressed enough) and dietary treatment are an effective and safe approach in infant regurgitation, but does not treat GER-disease. If the symptoms are refractory to this approach, or in reflux-disease, cisapride is the drug of choice. PPIs or H2-receptor antagonists, in combination with prokinetics, are recommended in (ulcerative) esophagitis. There is no excuse to persist with an ineffective management of a disease which might result in stunting, chronic illness, persistent pain, esophageal scarring or even death. Management of GER (-disease) in infants and children should therefore be well overthought, avoiding overinvestigations and o vertreatment of a self-limiting condition, but also avoiding underestimation of potential severe disease, accompanied by serious morbidity.

Footnotes

Edited by Ma JY

References

- 1.Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:569–572. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orenstein S. Gastroesophageal reflux. In: Hyman PE, ed , editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal motility disorders. New York: Academy Professional Information Services; 1994. pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenplas Y, Ashkenazi A, Belli D, Boige N, Bouquet J, Cadranel S, Cezard JP, Cucchiara S, Dupont C, Geboes K, et al. A proposition for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children: a report from a working group on gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:704–711. doi: 10.1007/BF01953980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvaraio F, Iacono G, Montalto G, Soresi M, Tumminello M, Carroccio A. Clinical and pH metric characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux secondary to cow's milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:51–56. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenplas Y, Lifshitz JZ, Orenstein S, Lifschitz CH, Shepherd RW, Casaubón PR, Muinos WI, Fagundes-Neto U, Garcia Aranda JA, Gentles M, et al. Nutritional management of regurgitation in infants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:308–316. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandenplas Y, Belli D, Benhamou P, Cadranel S, Cezard JP, Cucchiara S, Dupo nt C, Faure C, Gottrand F, Hassall E, et al. A critical appraisal of current management practicies for infant regurgitation-recommendations of a working party. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:343–357. doi: 10.1007/s004310050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandenplas Y, Belli D, Cadranel S, Cucchaiara S, Dupont C, Heymans H, Polan co I. Dietary treatment for regurgitation-recommendations from a working party. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:462–468. doi: 10.1080/08035259850157129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cucchiara S, De Vizia B, Minella R, Calabrese R, Scoppa A, Emiliano M, Iervolino C. Intragastric volume and osmolality affect mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in children with GOR disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:468 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borelli O, Salvia G, ampanozzi A, Franco MT, Moreira FL, Emiliano M, Campa nozzi F, Cucchiara S. Use of a new thickened formula for treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in infants. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandenplas Y. Clinical use of cisapride and its risk-benefit in paediatric patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:871–881. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199810000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verlinden M, Welburn P. The use of prokinetic agents in the treatment of gastro-intestinal motility disorders in childhood. In: Milla PJ, ed. Disorders of gastrointestinal motility in childhood. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1988. pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boix-Ochoa J. The physiologic approach to the management of gastric esophageal reflux. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(86)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heading RC, Baldi F, Holloway RH, Janssens J, Jian R, McCallum RW, Richter JE, Scarpignato C, Sontag SJ, Wienbeck M. Prokinetics in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. International symposium. Paris, France, 5 September 1996. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:87–93. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199801000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rode H, Stunden RJ, Millar AJ, Cywes S. Esophageal pH assessment of gastroesophageal reflux in 18 patients and the effect of two prokinetic agents: cisapride and metoclopramide. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mundo F, Feregrino H, Fernandez J, Teramoto O, Abord P. Clinical evalu ation of gastroesophageal reflux in children: double-blind study of cisapride vs metoclopramide. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:A29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cucchiara S, Staiano A, Capozzi C, Di Lorenzo C, Boccieri A, Auricchio S. Cisapride for gastro-oesophageal reflux and peptic oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:454–457. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.5.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Loore I, Van Ravensteyn H, Ameryckx L. Domperidone drops in the symptomatic treatment of chronic paediatric vomiting and regurgitation. A comparison with metoclopramide. Postgrad Med J. 1979;55 Suppl 1:40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenplas Y, Belli DC, Benatar A, Cadranel S, Cucchiara S, Dupont C, Gottrand F, Hassall E, Heymans HS, Kearns G, et al. The role of cisapride in the treatment of pediatric gastroesophageal reflux. The European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:518–528. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandenplas Y, Ashkenazi A, Belli D, Blecker U, Boige N, Bouquet J, Cad ranel S, Cezard JP, Cucchiara S, Devreker T, et al. Reflux oesophagitis in infants and children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:413–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutphen JL, Dillard VL, Pipan ME. Antacid and formula effects on gastric acidity in infants with gastroesophageal reflux. Pediatrics. 1986;78:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel DM, Hassall E. Omerprazole and other proton pump inhibitors: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety, with special reference to use in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:568–579. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argüelles-Martín F, González-Fernández F, Gentles MG, Navarro-Merino M. Sucralfate in the treatment of reflux esophagitis in children. Preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;156:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenplas Y. Physiopathological mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux: is motility the clue? Rev Med Brux. 1994;15:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutphen JL, Dillard VL. Dietary caloric density and osmolality influence gastroesophageal reflux in infants. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:601–604. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolia V, Lin CH, Kuhns LR. Gastric emptying using three different formulas in infants with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;15:297–301. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandenplas Y, Sacre L, Loeb H. Effects of formula feeding on gastric acidity time and oesophageal pH monitoring data. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;148:152–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00445926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey DJ, Andres JM, Danek GD, Pineiro-Carrero VM. Lack of efficacy of thickened feeding as treatment for gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 1987;110:187–189. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orenstein SR, Magill HL, Brooks P. Thickening of infant feedings for therapy of gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 1987;110:181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Putnam PE. Thickened feedings as a cause of increased coughing when used as therapy for gastroesophageal reflux in infants. J Pediatr. 1992;121:913–915. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramenofsky ML, Leape LL. Continuous upper esophageal pH monitoring in infants and children with gastroesophageal reflux, pneumonia, and apneic spells. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:374–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(81)80698-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandenplas Y, Sacré-Smits L. Gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants. Evaluation of treatment by pH monitoring. Eur J Pediatr. 1987;146:504–507. doi: 10.1007/BF00441604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandenplas Y, Sacré L. Milk-thickening agents as a treatment for gastroesophageal reflux. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1987;26:66–68. doi: 10.1177/000992288702600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandenplas Y, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Casteels A, Mahler T, Loeb H. A clinical trial with an "anti-regurgitation" formula. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:419–423. doi: 10.1007/BF01983405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brueton MJ, Clarke GS, Sandhu BK. The effects of cisapride on gastro-oesophageal reflux in children with and without neurological disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32:629–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb08547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrasco S, lama R, Prieto G, Polanco I. Treatment of gastroesopha geal reflux and peptic oesophagitis with cisapride. In: Heading RC, Wood JD (eds ) Gastrointestinal dysmotility: focus on cisapride, editors. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 326–327. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrocio A, Iacono G, Voti L. Gastric emptying in infants with gastroe sophageal reflux. Ultrasound evaluation before and after cisapride administratio n. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:799–804. doi: 10.3109/00365529209011187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castro HE, Ferrero GB, Cortina LS, Salces C, Lima M. Effectividad del cisapride en el trtamiento del reflujo gastroesofagico (RGE) in nonos. Valoracion de un estudio a doble ciego. An Espegnol Pediatr. 1994;40:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cucchiara S, Staiano A, Capozzi C, Di Lorenzo C, Boccieri A, Auricchio S. Cisapride for gastro-oesophageal reflux and peptic oesophagitis. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:454–457. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.5.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cucchiara S, Staiano A, Boccieri A, De Stefano M, Capozzi C, Manzi G, Camerlingo F, Paone FM. Effects of cisapride on parameters of oesophageal motility and on the prolonged intraoesophageal pH test in infants with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1990;31:21–25. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daoud G, Gonzalez L, Medina M, Stanzione C, Abraham A, Puig M, Daoud N, Martinez M. Efficacy of cisapride in infants with apnea and gastroesophageal r eflux evaluated by prolonged intraesophageal pH monitoring. 2nd UEGW, Barcelona, Spain, 19-23/07/1993, A107 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daoud G, Stanzione C, Abraham A, Lopez C, Henriquez S, Dahdah J, Puig M, Daoud N. Response to cisapride in children with respiratory symptoms and gast roesophageal reflux evaluated by prolonged intraesophageal pH monitoring. 2nd UE GW, Barcelon, Spain, 19-23/07/1993, A108 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans DF, Ledingham SJ, Kapila L. The effect of medical tehrapy on gas troesophageal reflux disease in children. World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Sydney, Australia, 26-31/08/1990, A53 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greally P, Hampton FJ, MacFadyen UM, Simpson H. Gaviscon and Carobel compared with cisapride in gastro-oesophageal reflux. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:618–621. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.5.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iacono G, Carrocio A, Montalto G. Vulutazione dell' efficacia della ci sapride nel trattamento del reflusoo gastroes-ofageo. Minerva Pediatr. 1992;44:613–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malfroot A, Vandenplas Y, Verlinden M, Piepsz A, Dab I. Gastroesophageal reflux and unexplained chronic respiratory disease in infants and children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1987;3:208–213. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950030403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mundo F, Feregrino H, Fernandez J. Clinical evaluation of gastroesopha geal reflux in children: double-blind study of cisapride vs metoclopramide. A m J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:A29. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rode H, Stunden RJ, Millar AJ, Cywes S. Esophageal pH assessment of gastroesophageal reflux in 18 patients and the effect of two prokinetic agents: cisapride and metoclopramide. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rode H, Millar AJW, Melis J, Cewis S. Pharmacological control of gastr o-oesophageal reflux with cisapride in infants: long-term evaluation. In: Head ing RC, Wood JD, eds , editors. Gastrointestinal dysmotility: focus on cisapride. New York: Rave Press; 1992. p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saye Z, Forget PP. Effect of cisapride on esophageal pH monitoring in children with reflux-associated bronchopulmonary disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:327–332. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198904000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saye ZN, Forget PP, Geubelle F. Effect of cisapride on gastroesophageal reflux in children with chronic bronchopulmonary disease: a double-blind cross-over pH-monitoring study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1987;3:8–12. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vandenplas Y, Deneyer M, Verlinden M, Aerts T, Sacre L. Gastroesophageal reflux incidence and respiratory dysfunction during sleep in infants: treatment with cisapride. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:31–36. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandenplas Y, de Roy C, Sacre L. Cisapride decreases prolonged episodes of reflux in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:44–47. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Eygen M, Van Ravensteyn H. Effect of cisapride on excessive regurgitation in infants. Clin Ther. 1989;11:669–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott RB, Ferreira C, Smith L, Jones AB, Machida H, Lohoues MJ, Roy CC. Cisapride in pediatric gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:499–506. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen RC, O'Loughlin EV, Davidson GP, Moore DJ, Lawrence DM. Cisapride in the control of symptoms in infants with gastroesophageal reflux: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1999;134:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]