TREATMENT STRATEGIES FOR ACUTE VARICEAL BLEEDING

Background

Acute variceal bleeding has a significant mortality which ranges from 5% to 50% in patients with cirrhosis[1]. Overall survival is probably improving, because of new therapeutic approaches, and improved medical care. However, mortality is still closely related to failure to control haemorrhage or early rebleeding, which is a distinct characteristic of portal hypertensive bleeding and occurs in as many as 50% of patients in the first days to 6 weeks after admission et al[2]. Severity of liver disease is recognised as a risk factor for both early rebleeding and short-term mortality after an episode of variceal bleeding[3]. Active bleeding during emergency endoscopy (e.g. oozing or spurting from the ruptured varix) has been found to be a significant indicator of the risk of early rebleeding[4,5]. Increased portal pressure (HVPG > 16 mmHg) has been proposed as a prognostic factor of early rebleeding in a study of continuous portal pressure measurement immediately after the bleeding episode[6], and recently Moitinho et al[7] have shown a failure to reduce portal pressure more than 20% from baseline is associated with a worse prognosis as well as early rebleeding.

Effective resuscitation, accurate diagnosis and early treatment are key to reducing mortality in variceal bleeding. The aims are not only to stop bleeding as soon as possible but also to prevent early re-bleeding. Early rebleeding, as with the peptic ulcer disease, is significantly associated with worsening mortality[5]. Thus treatments regime should be evaluated not only in terms of immediate cessation of haemorrhage, but also in terms of providing a bleed free interval of at least 5 d. This allows some recovery of the patient, and provides an opportunity for secondary preventative therapy to be instituted.

Diagnosis

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is essential to establish an accurate diagnosis, as 26%-56% of patients with portal hypertension and GI bleeding will have a non-variceal source[8], particularly from peptic ulcers and portal hypertensive gastropathy. Endoscopy should be performed as soon as resuscitation is adequate, and preferably with 6 h of admission. This may need to be done with prior endotracheal intubation if there is exsanguinating haemorrhage or if the patient is too encephalopatic because of the substantial risk of aspiration.

Despite many authors and junior doctors proclaiming endoscopic prowess, it is the authors opinion that a definitive endoscopic diagnosis during or shortly after upper GI bleeding can be difficult, because the view can be obscured by blood. A diagnosis of bleeding varices is accepted either when a venous (non pulsatile) spurt is seen, or when there is fresh bleeding from the O-G junction in the presence of varices, or fresh blood in the fundus when gastric varices are present. In the absence of active bleeding (approximately 50%-70% of cases) either the presence of varices in the absence of other lesions, or a “white nipple sign” - a platelet plug on the surface of a varix[9,10], suggests varices as the source of haemorrhage.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, repeat endoscopy during re-bleeding is mandatory as it will show a variceal source in over 75% of patients[8]. Gastric varices are particularly difficult to diagnose, because of pooling of blood in the fundus. Endoscoping the patient on the right side, with the head up may help. If the diagnosis is still not made, splanchnic angiography will establish the presence of varices, and may display the bleeding site if the patient is actively haemorrhaging.

In the true emergency situation in which the patient is exsanguinating and varices are suspected on the basis of history and examination, a Sengstaken Blakemore tube (SBT) should be passed[11]. If control of bleeding is obtained, varices are likely to be the source of haemorrhage. If blood is still coming up the gastric aspiration port, then varices are less likely to be the cause of blood loss (although fundal varices are not always controlled by tamponade). In practice the position of the SBT has to be re checked and adequate traction applied. If there is still continued bleeding the diagnosis of variceal bleeding should be questioned or fundal bleeding suspected, and emergency angiography performed.

Therapeutic aims in acute variceal bleeding

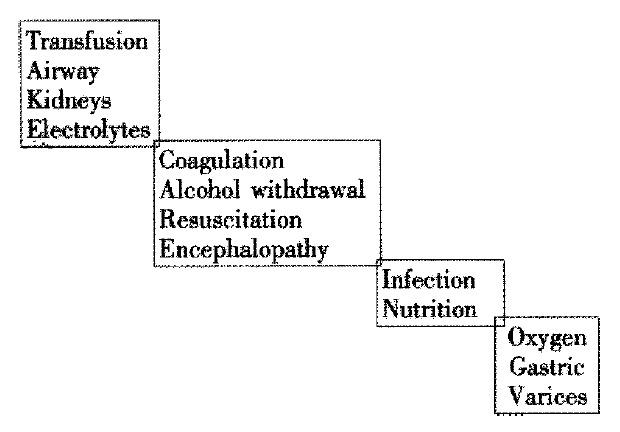

The important point is to treat the patient and not just the source of bleeding (Figure 1). The specific aims are: ① Correct hypovolaemia; ② Stop bleeding as soon as possible; ③ Preven rebleeding; ④ Prevent complications associated with bleeding; ⑤ Prevent deterioration in liver function.

Figure 1.

Take care in OGV.

It is important to identify those at high risk of dying during the initial assessment. Individuals in this category should have early definitive therapy, the precise treatment regimen depending on availability Predictive factors for early deaths are: Severity of bleeding[12], Severity of liver disease[13], Presence of infection[14], Presence of renal dysfunction[15], Active bleeding[4,5], Early rebleding[5,6,10,16,17], Presence of cardiorespiratory disease, and Portal pressure[7].

Early rebleeding is also associated with many of the same factors associated with mortality including infections[18] and is a strong indication of increased mortality.

Transfusion

Optimal volume replacement remains controversial. Following variceal bleeding in portal hypertensive animal models, return of arterial pressure to normal with immediate transfusion results in overshoot in portal venous pressure, with an associated risk of further bleeding[19]. This effect may not be relevant in clinical practice as volume replacement is always delayed with respect to the start of bleeding. Over-transfusion should certainly be avoided, and it is usual to aim for an Hb between 9-10 g/dL, and right atrial pressure at 4 to 8 mmHg, but fluid replacement may need to be greater in the presence of oliguria to be sure that the circulation is filled. Large volume transfusion may worsen the haemorrhagic state, as well as lead to thrombocytopenia so that fresh frozen plasma and platelets need to be replaced. Optimal regimens for this are not known. It is reasonable to give 2 units of FFP after every 4 units of blood, and when the PT is > 20 seconds. Cryoprecipitate is indicated when the fibrinogen level is less than 0.2 g/L.

Platelet transfusions are necessary to improve primary haemostasis and should be used if the baseline count is 50 × 109/L or less. Platelet count may show little change following platelet transfusion in patients with splenomegaly. It is also routine to give intravenous vitamin K to cirrhotics, but no more than three doses of 10 mg are required. Many cirrhotics have a background tendency of fibrinolysis. Transfusion of more than 15 units of blood results in prolongation of the prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time[20] in normal individuals, and occurs with smaller volumes of blood transfusion in cirrhosis.

Massive transfusion may cause pulmonary microembolism, and the use of filters is recommended for transfusions of 5 L or more in normal humans[21]. Therefore, the routine use of filters in variceal haemorrhage could be considered, but rapid transfusions cannot be administered with these, limiting their application.

Further measures in patients who continue to bleed despite balloon tamponade include the use of desmopressin (DDAVP)[22] and antifibrinolytic factors. In stable cirrhotics the former produces a 2-4 fold increase in factors VIII and VWF, presumably by release from storage sites and may shorten or normalize the bleeding time[23]. However, in one study of variceal bleeding DDAVP in association with terlipressin was shown to be detrimental compared to terlipressin alone[24].

The use of antifibrinolytics has not been studied in variceal bleeding, although their role has been established in liver transplantation in our unit as well as others[25]. Their clinical utility should be established in clinical trials, and preferably when increased fibrinolysis has been documented. Recombinant factor VIII may be useful in variceal bleeding as it has been shown to normalize prothrombin time and bleeding times in cirrhotics[26].

PREVENTION OF COMPLICATIONS AND DETERIORATION IN LIVER FUNCTION

Infection control and treatment

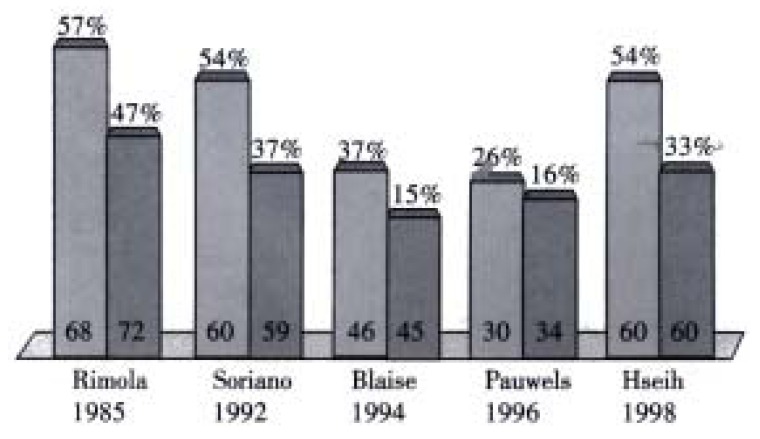

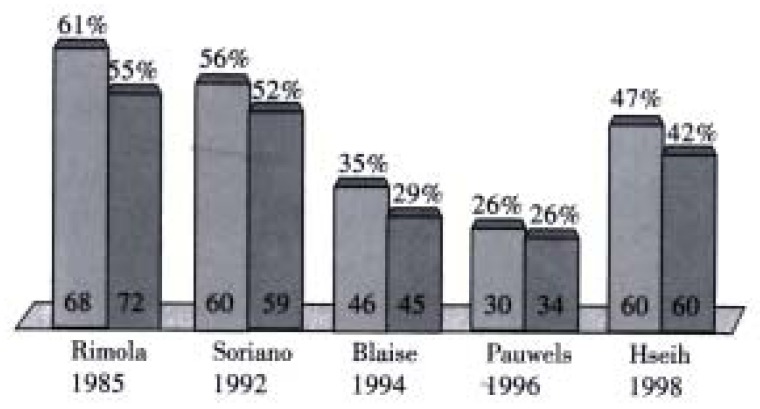

Bacterial infections have been documented in 35%-66% of patients with cirrhosis who have variceal bleeding, with a incidence of SBP ranging from 7%-15%. However if only patients with ascites and gastrointestinal bleeding are considered, the incidence of SBP is very high. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis significantly increased the mean survival rate (9.1% mean improvement rate, 95%CI: 2.9-15.3, P = 0.004) and also increased the mean percentage of patients free of infection (32% mean improvement rate, 95% confidence interval: 22-42, P < 0.001)[27] (Figure 2, Figure 3). Finally our group has recently shown that bacterial infection, diagnosed on admission, is an independent prognostic factor of failure to control bleeding or early rebleeding[4]. These data may support a role of bacterial infection in the initiation of variceal bleeding[28]. All cirrhotics with upper gastrointestinal bleeding should receive prophylactic antibiotics whether sepsis is suspected or not. The optimal regimen is yet to be decided but oral or intravenous quinolones have been used.

Figure 2.

Antibiotics in GI bleeding in cirrhotics (Bernard 1999). Free of infection-mean improvement 32% (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Antibiotics in GI bleeding in cirrhotics (Bernard 1999). Survival-mean improvement 9% (P = 0.0042).

Ascites and renal function

Renal failure may be precipitated by a variceal bleed, usually due to a combination of acute tubular necrosis, and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) associated with deterioration in liver function and sepsis. HRS is associated with an over 95% mortality. Thus any iatrogenic precipitants must be avoided. The intravascular volume should be maintained preferably with Human Albumin Solution or blood initially. Normal saline should be avoided as it may cause further ascites formation. Catheterisation of the bladder and hourly urine output measurement is mandatory and nephrotoxic drugs should be avoided, especially aminoglycosides and non-steroidal drugs.

Dopamine was the first drug used due its vasodilator effect when given in subpressor doses. Dopamine is frequently prescribed to patients with renal impairment, and yet no studies have ever shown any convincing benefit[29,30]. It is our impression that occasionally a patient responds with an increase in urine output. It is therefore our practice to give a 12-h trial of dopamine, and stop treatment if there has been no improvement of urine output.

Increasing ascites may occur shortly after bleeding, but should not be the main focus of fluid and electrolyte management until bleeding has stopped and the intravascular volume is stable. If there is a rising urea and creatinine, all diuretics should be stopped, and paracentesis performed if the abdomen becomes uncomfortable, re-infusing 8 gr. of albumin for every litre removed.

When the patient has stopped bleeding for 24 h, nasogastric feeding can be commenced with low sodium feed. This avoids the need for maintenance fluid, and removes the risk of line sepsis. An unexplained rise in creatinine and urea may indicate sepsis. Evidence of sepsis should be sought by blood, ascitic, cannulae, and urine culture, and non-nephrotoxic broad-spectrum antibiotics commenced, regardless of evidence of sepsis. An undiagnosed delay in effective treatment of infection may increase mortality. In advanced cirrhosis, endotoxins and cytokines play an increasingly important role in advancing the hyperdynamic circulation and worsening renal function[31].

There is now increasing evidence for the use of vasopressin analogues in patients who develop renal impairment during the variceal bleeding episode, probably through maintenance of renal perfusion. Indeed, the beneficial effect of terlipressin with respect to bleeding and survival in trials to date may be through the prevention of this catastrophic complication[32-34].

Porto systemic encephalopathy

The precipitant factors include: haemorrhage, sepsis, sedative drugs, constipation, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. These should be evaluated and corrected. Hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and hypoglycaemia may precipitate encephalopathy and should be aggressively corrected (e.g. a patient with ascites and a serum potassium of 3.0 mmol/L is likely to require in excess of 100 mmol over 24 h).

As soon as the patient is taking oral fluid, lactulose 5 mL-10 mL QDS can be started. Phosphate enemas are also useful.

Alcohol withdrawal

It is important to be alert to the possibility of withdrawal from the patient’s history. Encephalopathy and withdrawal may co-exist, and careful use of benzodiazepines may be required. Short acting benzodiazepines or oral chlormethiazole can be used. Intravenous preparations should be avoided, particularly of chlormethiazole, because of the risk of oversedation and aspiration.

Nutrition

Only a few cirrhotics are not malnourished[35], particularly with severe liver disease. This may be exacerbated in hospital, as often they do not want to eat, are “nil by mouth” because of investigations, and the food itself may be “unappealing”.

A fine bore nasogastric tube should be passed 24 h after cessation of bleeding to commence feeding. There is no evidence that this may precipitate a variceal bleed, and it allows treatment of encephalopathy in comatose patients and makes fluid management easier. It is extremely rare that parental nutrition is required.

Vitamin replacement: All patients with a significant alcoholic history should be assumed to be folate and thiamine deficient, and be given at least three doses of the latter intravenously. It is easier and more practical to assume all such patients are vitamin deficient rather than delay treatment whilst awaiting red cell transketolase activity levels.

Transfer of the patient with bleeding varices and use of balloon tamponade

Inter-hospital transfer should not be attempted unless the bleeding has been controlled, either with vasopressor agents/endoscopic therapy or tamponade. If there is any suggestion of continued blood loss, and the source is known to be variceal, then a modified Sengstaken tube must be inserted prior to transfer.(i.e. with an oesophageal aspiration channel such as the Minnesota Tube).

DRUG THERAPY IN ACUTE VARICEAL BLEEDING

Pharmacological agents

The number of placebo controlled trials is relatively small, whilst in the case of octreotide there have been a large number of trials comparing with another form of therapy another drug, or sclerotherapy.

Vasopressin

Only 4 trials compared the efficacy of vasopressin with a placebo[36-39], and two of these studies used an intrarterial route of administration[38,39]. Using meta-analysis, there was a significant reduction in failure to control bleeding (Pooled Odds Ratio 0.22, 95%CI 0.12-0.43), but no benefit in terms of mortality.

Glypressin

The 3 trials are shown in Table 1. There has been criticism of these studies. The trial by Walker et al included other therapies, the timing of which is unclear, and the other two trials are hampered by insufficient patient numbers to avoid a type 2 error. These issues will be addressed in forthcoming trials.

Table 1.

Randomized studies of terlipressin

| Study (ref) | Number of patients | Child C | Failure to control bleeding | Death |

| C/T | % | C/T | C/T | |

| Terlipressin vs placebo | ||||

| Walker, 1986[40] | 25/25 | 50 | 12/5 | 8/3 |

| Freeman, 1989[41] | 16/15 | 29 | 10/6 | 4/3 |

| Soderlund, 1990[42] | 29/31 | 33 | 13/5 | 11/3 |

| Levacher, 1995[43] | 43/41 | 81 | 23/12 | 20/12 |

| POR (95%CI) | 0.33 | 0.38 | ||

| (0.19-0.57) | (0.22-0.69) | |||

| P value | 0.0001 | 0.001 |

A recent study in which terlipressin together with a nitrate patch or placebo was administered before arriving at hospital, based on reasonable evidence of bleeding varices, also showed a reduced mortality of glypressin in grade C patients. How this may have occurred deserves further examination, as there was no difference in blood pressure or early blood product requirements between the drug and placebo arms of the trial, and only three doses of the drug were given. Nonetheless, Terlipressin is a powerful splanchnic vasoconstrictor, and may be preserving renal blood flow and hence preventing the development of hepatorenal syndrome, in a situation similar to the use of vasopressin anolgues in established hepatorenal failure.

It remains to be seen whether these data can be reproduced. Terlipressin is not licensed in the USA.

Somatostatin/Octreotide

The first 2 placebo controlled trials came to opposite conclusions. The trial by Valenzuela et al[44] suggested that somatostatin is no more effective than placebo, when the end point was a bleed-free period of 4 h. Furthermore, the 83% placebo rate is the highest reported in the literature. In contrast, the trial by Burroughs et al[45] reported a statistically significant benefit for somatostatin in controlling variceal bleeding over a 5 d treatment period, with failure to control bleeding seen in 36% of patients receiving somatostatin, compared with 59% of patients receiving placebo. This emphasizes the problem of differences in end point selection, making meaningful comparisons difficult. The third study[46] also showed no effect of somatostatin, but it took 5 years to recruit 86 patients.

There has been only one randomised placebo controlled trial examining the efficacy of octreotide, and this has only been published in abstract. 383 patient admissions were randomised to 5 d octreotide or placebo. 58% of bleeding episodes in the drug arm were controlled compared with 60% in the placebo arm[45].

Trials comparing drug with drug have shown little statistical difference, though the side effect profile has generally favoured somatostatin/octreotide[47]. Trials in which drugs are examined in association with sclerotherapy are reviewed below.

Randomised controlled trials of emergency sclerotherapy in the management of acute variceal bleeding

Injection sclerotherapy, first introduced in 1939 and “rediscovered” in the late 1970’s, rapidly became the endoscopic treatment of choice for the control of acute variceal bleeding. Paradoxically the best evidence for the value of sclerotherapy in the management of acute variceal bleeding has come from a comparatively recent published study by the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Variceal Sclerotherapy Group[48]. In this study sclerotherapy, compared to sham sclerotherapy, stopped haemorrhage from actively bleeding esophageal varices (91% in sclerotherapy arm compared to 60% in sham sclerotherappy, P < 0.001) and significantly increased hospital survival (75% vs 51%, P = 0.04).

Today it is generally accepted that sclerotherapy should be performed at the diagnostic endoscopy, which should take place as soon as possible, because there is evidence that this is beneficial compared with delayed injection. Volumes of sclerosant should be small, 1-2 mls in each varix and should be applied in the distal 5 cm of the oesophagus. More than two injection sessions are unlikely to arrest variceal bleeding within a 5-day period and are associated with significant complications rate including ulceration and aspiration[2]. Several sclerosing agents have been used for injection ie. polidocanol 1%-3%, ethanolamine oleate 5%, sodium tetradecyl sulfate 1%-2% and sodium morrhuate 5%. There is no evidence that any one sclerosant can be considered the optimal sclerosant for acute injection. As it has been shown that a substantial proportion of intravariceal sclerosant ends up in the paravariceal tissue and vice-versa there is no evidence that one technique is better than the other. One of the main shortcomings of sclerotherapy is the risk of local and systemic complications-although this varies greatly between trials and may be related to the experience of the operator.

Sclerotherapy vs drugs

There are 10 studies, including 921 patients: vasopressin was used in 1[49] terlipressin in 1[50], somatostatin in 3[51-53], and octreotide in 5[54-58], involving 921 patients. The evaluation of the treatment effect was performed at the end of the infusion of the drug (from 48 hrs to 120 hrs). The overall efficacy of sclerotherapy was 85% (range 73%-94%) in studies of 12 to 48 h drug infusion[49,52-56,58] and 74% (68%-84%) in studies of 120 hrs drug infusion[49,51,57]. There was significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05) in the evaluation of failure to control bleeding in these studies was, which was mainly due to the different extent of benefit from sclerotherapy rather than different outcomes in individual studies: only two of the ten studies[55,56], reported that drugs were better than sclerotherapy but in neither did this reach statistical significance. Failure to control bleeding was statistically significantly less frequent in patients randomized to sclerotherapy (Der Simonian and Laird method: POR, 1.68 [95%CI, 1.07-2.63]). The NNT to avoid one rebleeding episode is 11 (95%CI, 6-113). Publication bias assessment showed that 9 null or negative studies would be needed to render the results of this meta analysis non-significant.

There was no significant heterogeneity in the evaluation of mortality in these studies: only two studies[54,56] reported a lower mortality in the drug arm but in neither was this statistically significant. Overall there were statistically significantly fewer deaths in patients randomized to sclerotherapy (POR, 1.43 [95%CI, 1.05-1.95]). The NNT to avoid one death is 15 (NNT, 15 [95%CI, 8-69]). Finally the type of complications recorded in 8 studies[50-57] differed considerably, resulting in a significant heterogeneity ( P = 0.04). Four studies reported more complications in the sclerotherapy arm while 3 reported more complications[50,55,57] in the drug arm and one found equal numbers in both arms[56]. The meta analysis showed a trend in favour of drug treatment but the result was not statistically significant (Der Simonian and Laird method: POR, 0.71 [95%CI, 0.41-1.2]).

Sclerotherapy plus drugs vs sclerotherapy alone

This group comprised 5 studies[59-64] including 610 patients which compared sclerotherapy plus somatostatin, octreotide, or terlipress in with scleotherapy alone. Only three studies were placebo controlled[59,60,62]. Combination therapy was more effective (POR 0.42; 95%CI 0.29-0.6; failure to control bleeding sclerotherapy + drugs 22%, sclerotherapy alone 38% ARR 16, NNT = 6, 95%CI 4-10). No effect on mortality was demonstrated. Only two studies provided data on complication[59,60]. There were no significant differences between arms.

Sclerotherapy vs variceal ligation

There are only two studies specifically designed to compare sclerotherapy with variceal ligation for the management of the acute bleeding episode[65,66]. Other data come from 10 studies of long term sclerotherapy versus variceal ligation[67-76]. There was no statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.21) in the analysis of failure to control bleeding from the twelve studies[66-77], including a total of 419 patients. There was no difference between the two treatment modalities, although there was a trend in favour of variceal ligation (POR, 0.66 [95%CI, 0.36-1.18]). Short-term mortality was reported only in two studies[66,77] in both there was a trend in favour of variceal ligation but the result was not statistically significant. Finally only the two studies specifically designed to compare emergency sclerotherapy with variceal ligation[66,77] reported incidence of complications. Complications were less frequent in the variceal ligation arm in both studies and the result reached statistical significance in one[66].

Randomised controlled trials of emergency surgery in the management of acute variceal bleeding

Four randomised trials, performed during the previous decade, compared sclerotherapy to emergency staple transection[78-81]. Failure to control bleeding was reported only in two of these studies, with divergent results. Teres et al[80] reported that efficacy of transection in their study was only 71%, the lowest in the literature, compared to 83% in the sclerotherapy arm. In contrast in the largest study performed by Burroughs et al[81], a 5 d bleeding free interval was achieved in 90% of the transected patients (none rebled from varices) compared to 80% in those who had 2 emergency injection sessions. There was no difference in mortality between the two treatment modalities. Cello et al[78] showed that emergency porta-caval shunt was more effective than emergency sclerotherapy (followed by elective sclerotherapy) in preventing early rebleeding (19% vs 50%). Hospital and 30 d mortality was not significantly different. Finally Orloff et al[82] reported, in a small study, that portacaval shunt, performed in less than 8 h from admission, was significantly better than medical treatment (vasopressin/balloon tamponade) in the control of acute variceal bleeding. Survival was also better in the shunted patients but the difference was not statistically significant.

Randomized controlled trials of tissue adhesives in the management of acute variceal bleeding

Two types of tissue adhesives (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate [Histoacryl] and isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate [Bucrylate]) have been used for the control of variceal bleeding[83]. The adhesives could offer better immediate control of bleeding because they harden within seconds upon contact with blood[84]. However extra care must be taken to ensure that the adhesive does not come into contact with the endoscope and blocks the channels of the instrument. This can be prevented if the adhesive is mixed with lipiodol to delay hardening. Ideally, the sclerotherapy needle should be carefully placed within the varix prior to injection, to avoid leak of the adhesive[84]. Two randomised controlled trials compared sclerotherapy alone with the combination of sclerotherapy and Histoacryl for the control of active variceal bleeding[85,86]. The combined treatment was more effective than sclerotherapy alone in both studies. Two further studies compared Histoacryl to variceal ligation for the control of bleeding from oesophageal[87] or oesophagogastric varices[88]. The overall success rate for initial haemostasis of both treatment modalities was similar in these studies. However Histoacryl was superior to variceal ligation for the control of fundic variceal bleeding, but it was less effective for the prevention of rebleeding (67% vs 28%). Finally, in a recent small study[89], a biological fibrin glue (Tissucol) was more effective than sclerotherapy with polidocanol in the prevention of early rebleeding and had significantly lower incidence of complications. More studies are necessary to confirm these data and examine the potential risks of activation of coagulation, systemic embolism and transmission of infections with the human plasma derived fibrin glue.

Emergency transhepatic porto-systemic stent shunt

The first reports of TIPS used clinically were in patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding. In this very ill group of patients TIPS was found to have a life saving role, stopping bleeding in over 90% of patients; over half of these were leaving hospital alive, figures that were unachievable before. Prolonged expensive postoperative ventilation on intensive care was avoided, a situation with a well-defined high mortality[90]. Perhaps as a consequence of this apparent efficacy, there have been no controlled trials of emergency TIPS against other forms of salvage therapy.

One of the biggest problems in discussing uncontrolled variceal bleeding is that there is no accepted definition for this clinical situation. At Baveno 2[91], the panel was unable to reach a consensus as to what this term meant and what its defining parameters were. A re-evaluation of this was recommended at Baveno 3[92] and justified by a prospective evaluation in France[93]. However the reduced efficacy of repeated sclerotherapy is well established, with bleeding control achieved in 70% after the first session and 90% after two sessions. Risk of aspiration, complications of sclerotherapy itself and the general deterioration of the patient render further endoscopy potentially hazardous, as established by Bornman et al[94] and at our unit[95] with no improvement in the control of bleeding. Thus with respect to esophageal varices, many use the definition of continued bleeding despite two sessions of therapeutic endoscopy within 5-day period of the index bleed. To this group of patients one can add those who continue to bleed despite a correctly positioned Sengstaken Blakemore tube (approximately 10% of patients with Sengstaken tube[96], and those patients who continue to bleed from gastric or ectopic varices despite vasoconstrictor therapy.

The results of emergency TIPS are shown in Table 2. There is a predictable proportion of patients with Pugh’s C cirrhosis and patients with bleeding gastric varices. In the largest series of salvage TIPS, gastric varices were shown to be no different in terms of bleeding characteristics and portal haemodynamics when compared with oesophageal varices[97].

Table 2.

Reports of TIPS for acute variceal bleeding

| Authors | Patients | Child score A/B | Source of bleeding, Gastric/Oesophageal/42 d (%) | Immediate control of bleeding (in completed TIPS) | Early rebleeding (within 1mo) | Mortality |

| Other | ||||||

| McCormick (1994)[116] | 20 | 1/7/12 | 3/17/- | 20/20 | 6 | 11 (55) |

| Jalan (1995)[109] | 19 | 3/3/13 | -/19 | 17/17 | 3 | 8 (42) |

| Sanyal (1996)[117] | 30 | 1/7/22 | 4/26/- | 29/29 | 2 | 12 (40) |

| Chau (1998)[97] | 112 | 5/27/80 | 28/84/- | 110 | 15 | 41 (37) |

| Gerbes (1998)[114] | 11 | 1/3/7 | 8/11 | 10 | 3 | 3 (27) |

| Banares (1998)[112] | 56 | 11/22/23 | 19/37/- | 53/55 | 8 | 15 (28) |

Key Concepts:﹒ Aim is not only stop bleeding but prevent early rebleeding as this significantly impairs survival﹒ Prophylactic use of antibiotics is manadatory﹒ Vasoactive drugs administered before diagnostic endoscopy for at least 48 h, and perhaps 5 d﹒ No more than 2 sessions of endoscopic therapy during the first 5 d of admission﹒ TIPS as salvage therapy for continued bleeding

Patients with bleeding varices that are inaccessible to an endoscope or respond poorly to sclerotherapy are well suited to TIPS. Typical cases include fundal varices, small bowel varices (classically around anastomotic or surgical resection sites[98,99] intraabdominal varices (punctured during large volume paracentesis[100], stomal varices[101,102] (usually in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and sclerosing cholangitis), and bleeding rectal varices[103]. These sites are also amenable to embolization via shunt. TIPS have been successfully placed in infants[104,105], and children[106-108] with similar efficacy.

The results of emergency TIPS are good, especially when compared historically with surgery[109], but the mortality in these series of patients with uncontrolled bleeding is high. There is a need to try to improve patient selection. A number of markers of outcome have been identified. Including the APACHE score[110], presence of hyponatremia and child C liver disease[111], hepatic encephalopathy before TIPS, presence of ascites and serum albumin[112]. Artificial neural network have been developed and validated[113], though many of these series have mixed patients having elective TIPS and those having the procedure as an emergency. The authors feel that this latter group of patients is likely to be different from patients having an elective procedure, with characteristics of haemodynamic instability, worse liver function, lower platelets counts, and higher serum urea concentrations.

At Royal Free Hospital a score system was developed on 54 patients undergoing emergency TIPS as salvage therapy[115]. A prognostic index was developed, based on six factors independently predicted death on multivariate analysis: presence of moderate/severe ascites, requirement for ventilation, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum creatinine and partial tromboplastine time. The score was validated in a further 31 patients and shown to be accurate in predicting mortality. The use of TIPS as a salvage therapy in patients who have uncontrolled variceal bleeding is likely to remain the most established indication for TIPS, and clinical experience to date suggest that this procedure will be required in 10%-20% of patients presenting portal hypertension related bleeding.

CONCLUSION

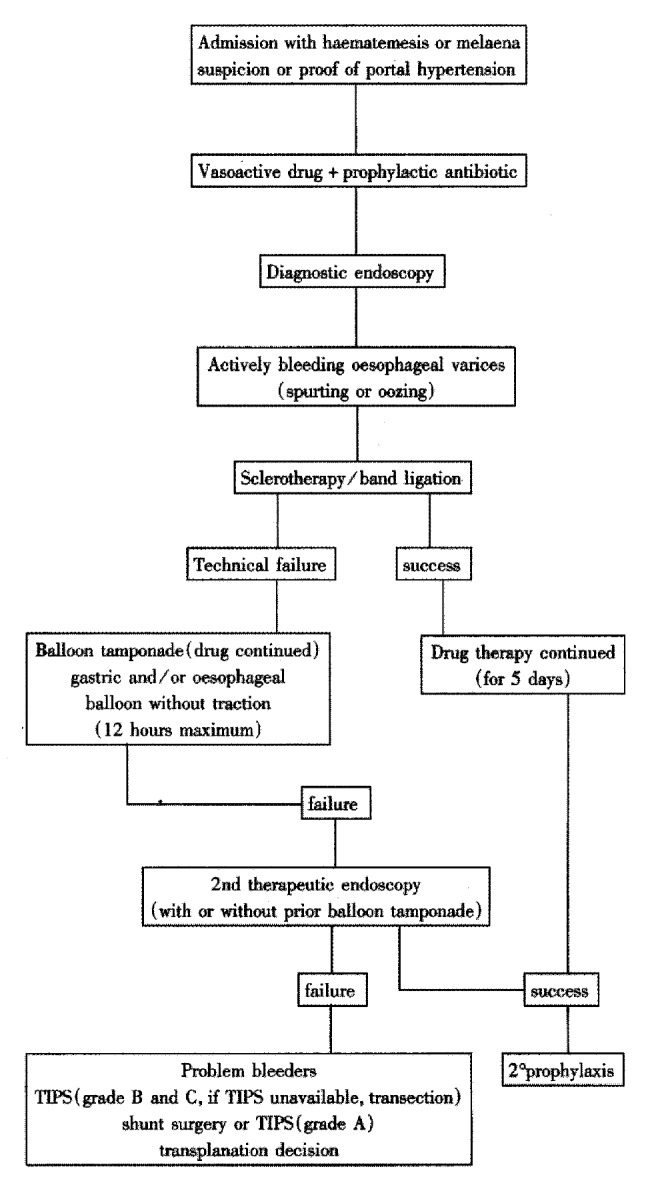

Today the therapeutic approach in cirrhotic patients with bleeding varices must include the prophylactic use of antibiotics, early endoscopic diagnosis and endoscopic therapy, probably combined use of vasoactive agents. The best evidence for an improvement in mortality is for terlipressin, but only data for 48-h treatment exists; for somatostatin, which is an alternative, there is data for 5-d use. However mortality is unchanged in trials of endoscopic therapy versus endoscopic therapy combined with vasoactive agents. Further trials are indicated in this area. Although no randomized trials on emergency TIPS exist, this procedure is very effective in stopping bleeding and has virtually eliminated the need for emergency surgery, and reduced ITU stays. If new trials are to be done, comparison with glues or thrombin may be justified.

All studies should now adhere to consensus definition[92] so that the field can accumulate evidence for optimal treatment strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Not available

Footnotes

Edited by Rampton DS and Ma JY

References

- 1.D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–354. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burroughs AK, Mezzanotte G, Phillips A, McCormick PA, McIntyre N. Cirrhotics with variceal hemorrhage: the importance of the time interval between admission and the start of analysis for survival and rebleeding rates. Hepatology. 1989;9:801–807. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Burroughs AK, Pagliaro L, Makuch RW, Bosch J, Stiegmann GV, Henderson JM, de Franchis R, et al. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding: an AASLD single topic symposium. Hepatology. 1998;28:868–880. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulis J, Armonis A, Patch D, Sabin C, Greenslade L, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection is independently associated with failure to control bleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1998;27:1207–1212. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Ari Z, Cardin F, McCormick AP, Wannamethee G, Burroughs AK. A predictive model for failure to control bleeding during acute variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol. 1999;31:443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ready JB, Robertson AD, Goff JS, Rector WG. Assessment of the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices by continuous monitoring of portal pressure. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1403–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moitinho E, Escorsell A, Bandi JC, Salmerón JM, García-Pagán JC, Rodés J, Bosch J. Prognostic value of early measurements of portal pressure in acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:626–631. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell KJ, MacDougall BR, Silk DB, Williams R. A prospective reappraisal of emergency endoscopy in patients with portal hypertension. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou MC, Lin HC, Kuo BI, Lee FY, Schmidt CM, Lee SD. Clinical implications of the white nipple sign and its role in the diagnosis of esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2103–2109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siringo S, McCormick PA, Mistry P, Kaye G, McIntyre N, Burroughs AK. Prognostic significance of the white nipple sign in variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlavianos P, Gimson AE, Westaby D, Williams R. Balloon tamponade in variceal bleeding: use and misuse. BMJ. 1989;298:1158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6681.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garden OJ, Motyl H, Gilmour WH, Utley RJ, Carter DC. Prediction of outcome following acute variceal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1985;72:91–95. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Dombal FT, Clarke JR, Clamp SE, Malizia G, Kotwal MR, Morgan AG. Prognostic factors in upper G.I. bleeding. Endoscopy. 1986;18 Suppl 2:6–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleichner G, Boulanger R, Squara P, Sollet JP, Parent A. Frequency of infections in cirrhotic patients presenting with acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1986;73:724–726. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.del Olmo JA, Peña A, Serra MA, Wassel AH, Benages A, Rodrigo JM. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)68827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarin SK. Long-term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardin F, Gori G, McCormick P, Burroughs AK. A predictive model for very early rebleeding from varices. Gut. 1990:31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goulis J, Armonis A, Patch D, Sabin C, Greenslade L, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection is independently associated with failure to control bleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1998;27:1207–1212. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kravetz D, Bosch J, Arderiu M. Abnormalities in organ blood flow and its distribution during expiratory pressure ventilation. Hepatology. 1989;9:808–814. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck EA, Bove JR, Högman CF, Langdell RD, Schorr JB, Tullis JL, Veltkamp JJ. Which is the factual basis, in theory and clinical practice, for the use of fresh frozen plasma. Vox Sang. 1978;35:426–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1978.tb02961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins JA. Abnormal hemoglobin-oxygen affinity and surgical hemotherapy. Bibl Haematol. 1980;(46):59–69. doi: 10.1159/000430548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cattaneo N, Teconi P, Albera I, Garcia V. Subcutaneous desmopressin shortened the prolonged bleeding time in pa-tients with cirrhosis. Br J Hepatol. 1981;47:283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burroughs AK, Matthews K, Qadiri M, Thomas N, Kernoff P, Tuddenham E, McIntyre N. Desmopressin and bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:1377–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6506.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Franchis R, Arcidiacono PG, Andreoni B. Terlipressin plus desmopressin versus terlipressin alone in acute variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotics: interim analysis of double blind multicentre placebo controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1992:102. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith O, Hazlehurst G, Brozovic B, Rolles K, Burroughs A, Mallett S, Dawson K, Mehta A. Impact of aprotinin on blood transfusion requirements in liver transplantation. Transfus Med. 1993;3:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1993.tb00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papatheodoridis GV, Chung S, Keshav S, Pasi J, Burroughs AK. Correction of both prothrombin time and primary haemostasis by recombinant factor VII during therapeutic alcohol injection of hepatocellular cancer in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:747–750. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655–1661. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goulis J, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of variceal bleeding. Lancet. 1999;353:139–142. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett WM, Keeffe E, Melnyk C, Mahler D, Rösch J, Porter GA. Response to dopamine hydrochloride in the hepatorenal syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saló J, Ginès A, Quer JC, Fernández-Esparrach G, Guevara M, Ginès P, Bataller R, Planas R, Jiménez W, Arroyo V, et al. Renal and neurohormonal changes following simultaneous administration of systemic vasoconstrictors and dopamine or prostacyclin in cirrhotic patients with hepatorenal syndrome. J Hepatol. 1996;25:916–923. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navasa M, Follo A, Filella X, Jiménez W, Francitorra A, Planas R, Rimola A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: relationship with the development of renal impairment and mortality. Hepatology. 1998;27:1227–1232. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cervoni JP, Lecomte T, Cellier C, Auroux J, Simon C, Landi B, Gadano A, Barbier JP. Terlipressin may influence the outcome of hepatorenal syndrome complicating alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2113–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganne-Carrié N, Hadengue A, Mathurin P, Durand F, Erlinger S, Benhamou JP. Hepatorenal syndrome. Long-term treatment with terlipressin as a bridge to liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1054–1056. doi: 10.1007/BF02088218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadengue A, Gadano A, Moreau R, Giostra E, Durand F, Valla D, Erlinger S, Lebrec D. Beneficial effects of the 2-day administration of terlipressin in patients with cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome. J Hepatol. 1998;29:565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loguercio C, Sava E, Marmo R, del Vecchio Blanco C, Coltorti M. Malnutrition in cirrhotic patients: anthropometric measurements as a method of assessing nutritional status. Br J Clin Pract. 1990;44:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merigan TC, Plotkin GR, Davidson CS. Effect of intravenously administered posterior pituitary extract on hemorrhage from bleeding esophageal varices. A controlled evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1962;266:134–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196201182660307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fogel MR, Knauer CM, Andres LL, Mahal AS, Stein DE, Kemeny MJ, Rinki MM, Walker JE, Siegmund D, Gregory PB. Continuous intravenous vasopressin in active upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:565–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conn HO, Ramsby GR, Storer EH, Mutchnick MG, Joshi PH, Phillips MM, Cohen GA, Fields GN, Petroski D. Intraarterial vasopressin in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a prospective, controlled clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mallory A, Schaefer JW, Cohen JR, Holt AS, Norton LW. Se-lective intraarterial vasopressin infusion for upper gastrointes-tinal tract hemorrhage: a controlled trial. Ar Surg. 1980;115:30–32. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1980.01380010022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker S, Stiehl A, Raedsch R, Kommerell B. Terlipressin in bleeding esophageal varices: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Hepatology. 1986;6:112–115. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freeman JG, Cobden I, Record CO. Placebo-controlled trial of terlipressin (glypressin) in the management of acute variceal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:58–60. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198902000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soderlund C, Magnusson I, Torngren S, Lundell L. Terlipressin (triglycyl-lysine vasopressin) controls acute bleeding oesoph-ageal varices. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:622–630. doi: 10.3109/00365529009095539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levacher S, Letoumelin O, Pateron D, Blaise M, Lapandry C, Pourriat JL. Early administration of terlipressin plus glyceryl trinitrate to control active upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Lancet. 1995;346:865–868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valenzuela JE, Schubert T, Fogel MR, Strong RM, Levine J, Mills PR, Fabry TL, Taylor LW, Conn HO, Posillico JT. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of somatostatin in the management of acute hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1989;10:958–961. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burroughs AK, McCormick PA, Hughes MD, Sprengers D, D'Heygere F, McIntyre N. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of somatostatin for variceal bleeding. Emergency control and prevention of early variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gøtzsche PC, Gjørup I, Bonnén H, Brahe NE, Becker U, Burcharth F. Somatostatin v placebo in bleeding oesophageal varices: randomised trial and meta-analysis. BMJ. 1995;310:1495–1498. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6993.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feu F, DelArbol LR, Banares R, Plsanas R, Bosch J, Mas A, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bordas JM, Salmeron JM, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing terlipressin and somatostatin for acute variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1291–1299. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartigan PM, Gebhard RL, Gregory PB. Sclerotherapy for actively bleeding esophageal varices in male alcoholics with cirrhosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Variceal Sclerotherapy Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westaby D, Hayes PC, Gimson AE, Polson RJ, Williams R. Controlled clinical trial of injection sclerotherapy for active variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1989;9:274–277. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooperative Spanish-French group for the treatment of bleed-ing esophageal varices. Randomised controlled trial compar-ing terlipressin vs endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in the treat-ment of acute variceal bleeding and prevention of early rebleeding (abstract) Hepatology. 1997;26:249A. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shields R, Jenkins SA, Baxter JN, Kingsnorth AN, Ellenbogen S, Makin CA, Gilmore I, Morris AI, Ashby D, West CR. A prospective randomised controlled trial comparing the efficacy of somatostatin with injection sclerotherapy in the control of bleeding oesophageal varices. J Hepatol. 1992;16:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Planas R, Quer JC, Boix J, Canet J, Armengol M, Cabre E, Pintanel T, Humbert P, Oller B, Broggi MA, et al. A prospective randomised trial comparing somatostatin and sclerotherapy in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1994;20:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Febo G, Siringo S, Vacirca M. Somatostatin (SMS) and urgent sclerotherapy (US) in active oesophageal variceal bleeding [Abstract] Gastroenterology. 1990;98:583A. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sung JJ, Chung SC, Lai CW, Chan FK, Leung JW, Yung MY, Kassianides C, Li AK. Octreotide infusion or emergency sclerotherapy for variceal haemorrhage. Lancet. 1993;342:637–641. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91758-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jenkins SA, Shields R, Davies M, Elias E, Turnbull AJ, Bassendine MF, James OF, Iredale JP, Vyas SK, Arthur MJ, Kingsnorth AN, Sutton R. A multicentre randomised trial comparing octreotide and injection sclerotherapy in the management and outcome of acute variceal haemorrhage. Gut. 1997;41:526–533. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poo JL, Bosques F, Garduno R, Marin E, Moran MA, Bobadilla J, Maldonado EP, Morales D, Garcia-Cantu D, Uribe M. Octreotide versus emergency sclerotherapy in acute variceal haemorrhage in liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1996:110. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kravetz D, Group for the study of Portal Hypertension. Octreotide vs sclerotherapy in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1996:24. [Google Scholar]

- 58.El-Jackie A, Rowaisha I, Waked I, Saleh S, Abdel Ghaffar Y. Octreotide vs sclerotherapy in the control of acute variceal bleed-ing in schistosomal portal hypertension: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 1999:28. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Besson I, Ingrand P, Person B, Boutroux D, Heresbach D, Bernard P, Hochain P, Larricq J, Gourlaouen A, Ribard D. Sclerotherapy with or without octreotide for acute variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:555–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avgerinos A, Rekoumis G, Klonis C. Propranolol in the preven-tion of recurrent upper gastrointestinal-bleeding in patients with cirrhosis undergoing endoscopic sclerotherapy-a random-ized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 1993;19:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Averignos A, Nevens F, Raptis S, Fevery J, the ABOVE study group. Early administration of somatostatin and efficacy of sclerotherapy in acute oesophageal variceal bleeds: the Euro-pean Acute Bleeding Oesophageal Variceal Episodes (ABOVE) randomised trial. Lancet. 1997;350:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Signorelli S, Negrini F, Paris B, Bonelli M, Girola M. Sclero-therapy with or without somatostatin or octreotide in the treat-ment of acute variceal haemorrhage: our experience. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1326A. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brunati S, Ceriani R, Curioni R, Brunelli L, Repaci G, Morini L. Sclerotherapy alone vs sclerotherapy plus terlipressin vs sclero-therapy plus octreotide in the treatment of acute variceal haemorrhage (abstract) Hepatology. 1996;24:207A. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Signorelli S, Paris B, Negrini F, Bonelli M, Auriemma L. Esoph-ageal varices bleeding: comparison between treatment with sclerotherapy alone vs sclerotherapy plus octreotide. Hepatology. 1997:26. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jensen LS, Krarup N. Propranolol in prevention of rebleeding from oesophageal varices during the course of endoscopic sclerotherapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:339–345. doi: 10.3109/00365528909093057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Huang JS, Hsu PI, Chiang HT. Emergency banding ligation versus sclerotherapy for the control of active bleeding from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, Korula J, Lieberman D, Saeed ZA, Reveille RM, Sun JH, Lowenstein SR. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laine L, el-Newihi HM, Migikovsky B, Sloane R, Garcia F. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Hwu JH, Chang CF, Chen SM, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of sclerotherapy versus ligation in the management of bleeding esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1995;22:466–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hou MC, Lin HC, Kuo BI, Chen CH, Lee FY, Lee SD. Comparison of endoscopic variceal injection sclerotherapy and ligation for the treatment of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a prospective randomized trial. Hepatology. 1995;21:1517–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jain AK, Ray PP, Gupta JP. Management of acute variceal bleed: randomised trial of variceal ligation and sclerotherapy. Hepatology. 1996:23. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mostafa I, Omar MM, Fakry S. Prospective randomised comapartive randomised comapartive study of injection scle-rotherapy and band ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1996:23. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarin SK, Govil A, Jain AK. Prospective randomised trial of endoscopic sclerotherapy versus variceal band ligation for esophageal varices: influence on gastropathy, gastric varices and variceal recurrence. J Hepatol. 1997;26:826–832. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shiha GE, Farag FM. Endoscoscopic variceal ligation versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for the management of bleeding varices: a prospective randomisedtrial. Hepatology. 1997:26. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fakhry S, Omar MM, Mustafa I. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus endoscopic variceal ligation for the management of bleeding varices: a final report of prospective randomised study in schistosomal hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 1997:26. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gimson AE, Ramage JK, Panos MZ, Hayllar K, Harrison PM, Williams R, Westaby D. Randomised trial of variceal banding ligation versus injection sclerotherapy for bleeding oesophageal varices. Lancet. 1993;342:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jensen DM, Kovacs TOG, Randall GM. Initial results of randomised prospective study of emergency banding versus esclerotherapy for bleeding gastric or esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993:39. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cello JP, Crass R, Trunkey DD. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus esophageal transection of Child's class C patients with variceal hemorrhage. Comparison with results of portacaval shunt: preliminary report. Surgery. 1982;91:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huizinga WK, Angorn IB, Baker LW. Esophageal transection versus injection sclerotherapy in the management of bleeding esophageal varices in patients at high risk. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Terés J, Baroni R, Bordas JM, Visa J, Pera C, Rodés J. Randomized trial of portacaval shunt, stapling transection and endoscopic sclerotherapy in uncontrolled variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 1987;4:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burroughs AK, Hamilton G, Phillips A, Mezzanotte G, McIntyre N, Hobbs KE. A comparison of sclerotherapy with staple transection of the esophagus for the emergency control of bleeding from esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:857–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909283211303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Orloff MJ, Bell RH, Orloff MS, Hardison WG, Greenburg AG. Prospective randomized trial of emergency portacaval shunt and emergency medical therapy in unselected cirrhotic patients with bleeding varices. Hepatology. 1994;20:863–872. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840200414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soehendra N, Grimm H, Nam VC, Berger B. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a supplement to endoscopic sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 1987;19:221–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Franchis R, Bañares R, Silvain C. Emergency endoscopy strategies for improved outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1998;226:25–36. doi: 10.1080/003655298750027128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feretis C, Dimopoulos C, Benakis P, Kalliakmanis B, Apostolidis N. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) plus sclerotherapy versus sclerotherapy alone in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices: a randomized prospective study. Endoscopy. 1995;27:355–357. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thakeb F, Salama Z, Salama H, Abdel Raouf T, Abdel Kader S, Abdel Hamid H. The value of combined use of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and ethanolamine oleate in the management of bleeding esophagogastric varices. Endoscopy. 1995;27:358–364. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sung JY, Lee YT, Suen R. Banding is superior to cyanoacrylate for the treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A prospec-tive randomised study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:210. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duvall GA, Haber G, Kortan P. A prospective randomised trial of cyanoacrylate (CYA) versus endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) for acute esophagpgastric variceal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:172. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zimmer T, Rucktäschel F, Stölzel U, Liehr RM, Schuppan D, Stallmach A, Zeitz M, Weber E, Riecken EO. Endoscopic sclerotherapy with fibrin glue as compared with polidocanol to prevent early esophageal variceal rebleeding. J Hepatol. 1998;28:292–297. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(88)80016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shellman RG, Fulkerson WJ, DeLong E, Piantadosi CA. Prognosis of patients with cirrhosis and chronic liver disease admitted to the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:671–678. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.De Franchis R. Portal Hypertension II. Proceedings of the Sec-ond Baveno International Consensus Workshop on Definitions, Methodology and Therapeutic Strategies. Oxford 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Franchis R. Updating Consensus in portal hypertesnion: report of thr Baveno III consensus workshop on definitions, methodology and therapeutic strategies in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2000;33:846–852. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Calès P, Lacave N, Silvain C, Vinel JP, Besseghir K, Lebrec D. Prospective study on the application of the Baveno II Consensus Conference criteria in patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2000;33:738–741. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bornman PC, Terblanche J, Kahn D, Jonker MA, Kirsch RE. Limitations of multiple injection sclerotherapy sessions for acute variceal bleeding. S Afr Med J. 1986;70:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burroughs AK, Hamilton G, Phillips A, Mezzanotte G, McIntyre N, Hobbs KE. A comparison of sclerotherapy with staple transection of the esophagus for the emergency control of bleeding from esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:857–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909283211303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Panés J, Terés J, Bosch J, Rodés J. Efficacy of balloon tamponade in treatment of bleeding gastric and esophageal varices. Results in 151 consecutive episodes. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:454–459. doi: 10.1007/BF01536031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chau TN, Patch D, Chan YW, Nagral A, Dick R, Burroughs AK. "Salvage" transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: gastric fundal compared with esophageal variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)00640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jonnalagadda SS, Quiason S, Smith OJ. Successful therapy of bleeding duodenal varices by TIPS after failure of sclerotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:272–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.270_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Medina CA, Caridi JG, Wajsman Z. Massive bleeding from ileal conduit peristomal varices: successful treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Urol. 1998;159:200–201. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Arnold C, Haag K, Blum HE, Rössle M. Acute hemoperitoneum after large-volume paracentesis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:978–982. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bernstein D, Yrizarry J, Reddy KR, Russell E, Jeffers L, Schiff ER. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of intermittently bleeding stomal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2237–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Johnson PA, Laurin J. Transjugular portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding stomal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:440–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1018850910271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Godil A, McCracken JD. Rectal variceal bleeding treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Potentials and pitfalls. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:460–462. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199709000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sergent G, Gottrand F, Delemazure O, Ernst O, Bonvarlet P, Mizrahi D, L'Hermine C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in an infant. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:588–590. doi: 10.1007/s002470050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cao S, Monge H, Semba C, Cox KL, Berquist W, Concepcion W, So SK, Esquivel CO. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in an infant: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Steventon DM, Kelly DA, McKiernan P, Olliff SP, John PR. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt prior to liver transplantation. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:84–86. doi: 10.1007/s002470050072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Johnson SP, Leyendecker JR, Joseph FB, Joseph AE, Diffin DC, Devoid D, Eason J. Transjugular portosystemic shunts in pediatric patients awaiting liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;62:1178–1181. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199610270-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hackworth CA, Leef JA, Rosenblum JD, Whitington PF, Millis JM, Alonso EM. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation in children: initial clinical experience. Radiology. 1998;206:109–114. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jalan R, John TG, Redhead DN, Garden OJ, Simpson KJ, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. A comparative study of emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt and esophageal transection in the management of uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1932–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rubin RA, Haskal ZJ, O'Brien CB, Cope C, Brass CA. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting: decreased survival for patients with high APACHE II scores. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:556–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jalan R, Elton R, Redhead DN, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. Analy-sis of prognostic variables in the prediction of mortality, shunt failure, variceal rebleeding and encephalopathy following transjugular intrahepatc porto-systemic stent shunt for va-riceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol. 1995;93:75–99. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bañares R, Casado M, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Camúñez F, Matilla A, Echenagusía A, Simó G, Piqueras B, Clemente G, Cos E. Urgent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for control of acute variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.075_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jalan R, Hiltunen Y, Haag K. Training and validation of an artificial neural network to predict early mortality in patients undergoing the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) for variceal haemorrhage: analysis of data on 398 patients from two centres. Hepatology. 1999:26. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gerbes AL, Gülberg V, Waggershauser T, Holl J, Reiser M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for variceal bleeding in portal hypertension: comparison of emergency and elective interventions. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2463–2469. doi: 10.1023/a:1026686232756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Patch D, Nikolopoulou VN, McCormick PA. Factors related to early mortality afetr trasnjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) for uncontrolled variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol. 1998;28:454–460. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.McCormick PA, Dick R, Panagou EB, Chin JK, Greenslade L, McIntyre N, Burroughs AK. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic stent shunting as salvage treatment for uncontrolled variceal bleeding. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1324–1327. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sanyal AJ, Freeman AM, Luketic VA. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for patients with active variceal hemorrhage unresponsive to sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:138–146. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]