INTRODUCTION

Although several specific detecting methods had been applied to determine the hepatitis virus, there was a lot of cryptogenic hepatitis without any known hepatitis infectious marker[1]. The prevalence of hepatitis G virus (HGV) (also known as GB-C virus) infection has been reported to be 5%-13% in patients with non-A-E hepatitis and cirrhosis, however, there is little evidence suggesting that HGV causes hepatitis in human[2-6]. Although cryptogenic liver diseases are almost certainly related to a variety of etiologies, one or more as-yet-unidentified infectious agents are likely to account for a proportion of these cases.

In December 1997, a novel DNA virus was reported by Nishizawa et al[7] to be associated with elevated aminotransferase levels in patients with post-transfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology (non-A-G hepatitis). This virus was designated transfusion transmitted virus (TTV). Then, Luo et al[8] and Wei et al[9] also detected TTV in the sera of patients from an outbreak of cryptogenic hepatitis in south China. And TTV was also detected in patients with post-transfusion hepatitis in China[10]. In subsequent analyses, TTV is an un-enveloped single-stranded DNA virus for which a sequence of 3800 bases was determined[11]. Evidence of potential hepatotropism of TTV was reported with TTV DNA detected in liver tissue[12]. Histopathological study indicated that the characteristics of liver histology of TTV infected patients are portal inflammation and interlobular bile duct damage[13]. TTV was proposed as the part of causative agent of non-A to G hepatitis. Seroepidemiological studies have shown TTV to have global distribution[12,14,15]. Although the potential association of TTV with cryptogenic hepatitis is intriguing, the pathological and clinical significance of this virus remains to be established. To assess more thoroughly the etiological role of TTV in the causation of hepatitis, we determined the frequency of TTV infections and their relationship to liver disease in several cohorts of liver diseases and rural population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Rural population

Nighty males and 89 females aged from 1 to 73 years were from a natural village with total population of 190 in southeast of Yunnan Province. Among them, 90 persons were of nationality of Han, others of Yi.

Patients with cryptogenic hepatitis

Forty-four patients with cryptogenic hepatitis were admitted in hospital between January 1993 and May 1999, with negative assays for sera marker of hepatitis virus A-E, and also negative assays for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, EB virus antibody, CMV antibody and anti-mitochondrial antibody. Part of patients were confirmed with liver biopsy suggestive of acute hepatitis.

Patients with HBV related chronic liver diseases

The prevalence of TTV infection was also determined in five cohorts of HBV related chronic liver disease: ① HBsAg asymptomatic carrier (AsC) (n = 52); ② Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) (n = 46); ③ Chronic hepatic failure (n = 40); ④ Active liver cirrhosis (n = 39); ⑤ Hepatocyte carcinoma (HCC) (n = 21). The diagnosis accorded with diagnostic criterion of viral hepatitis in the Fifth Science Meeting of Infectious Disease and Verminosis (Beijing, 1995)[16].

Nested PCR for the detection of TTV DNA

Evidence for TTV infection was determined by detection of TTV DNA by nested PCR. Nucleic acids were extracted from 100 μL serum. TTV DNA was determined by PCR with nested primers described by Okamoto et al[11] that sensitively detect TTV DNA, irrespective of different genotypes, as well as by Ampli-Taq- DNA Polymerase. In brief, the first round of PCR was performed with RD038 primer (sense: 5’-TGACTGTGCTAAAGCCTCTA-3’) and NG059 (antisense: 5’-ACAGACAGAGGAGAAGGCAACATG-3’) for 35 cycles (94 °C, 45 s; 54 °C, 45 s; 72 °C, 60 s [additional 7 min for the last cycle]), and the second-round PCR was performed with NG061 (sense: 5’-GGCAACATGTTATGGATAGACTGG-3’) and NG063 (antisense: 5’-GACCGTAAAATGGTAAAGGTTTCA-3’) for 35 cycles with the same conditions. The size of the second-round PCR was 271 bp. The amplicons were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under ultraviolet light. All assays were performed in an amplicon-free work area. Positive and negative results were confirmed with repeated assays.

Direct sequencing of the amplicons

Direct sequencing of the amplicons was carried out by Cybersyn.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of TTV infection (as measured by TTV DNA detectable in serum by PCR) in rural population and several cohorts of liver disease was determined. Data analysis was carried out using χ2 test. And the liver function test of chronic hepatitis B was analysed using t test.

RESULTS

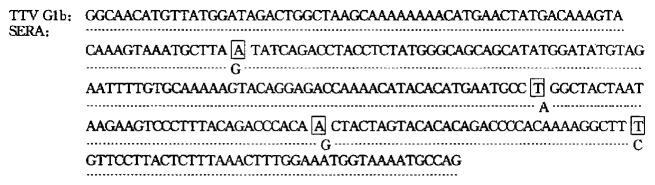

Sequencing of the amplicons (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Comparison of nucleic acids sequence bet ween TTV G1b and amplicons and nucleic acids sequence nt1935-2205 of TTV G1b, sera amplicons had a homogeneity of 98.5%, suggesting the presence of TTV DNA in sera.

Prevalence of TTV infection (Table 1)

Table 1.

Prevalence of TTV infection among study cohorts

| Groups | TTV positive rate (n) | TTV negative rate (n) | Total |

| Rural population | 10.61 (19) | 89.39 (160) | 179 |

| Cryptogenic hepatitisa | 38.63 (17) | 61.37 (27) | 44 |

| HBsAg asymptomatic carrier | 9.62 (5) | 90.38 (47) | 52 |

| Chronic hepatitis Bb | 15.22 (7) | 84.78 (39) | 46 |

| HBV related active liver cirrhosisc | 22.5 (9) | 77.5 (31) | 40 |

| HBV related hepatic failured | 23.08 (9) | 76.92 (30) | 39 |

| Hepatocyte carcinomae | 9.52 (2) | 90.48 (19) | 21 |

| Total | 16.15 (68) | 83.85 (353) | 421 |

χ2 = 20.486, P < 0.005 vs rural population;

χ2 = 0.713, P > 0.25 vs HBsAg asymptomatic carrier;

χ2 = 0.749, P > 0.25 vs chronic hepatitis B;

χ2 = 0.853, P > 0.25 vs chronic hepatitis B;

χ2 = 0.000, P > 0.9 vs HBsAg asymptomatic carrier.

Rural population

Ninteen of 179 (10.61%) unselected healthy peoples were detected TTV DNA positive. The prevalence of TTV infection was inde pendent of sex, age and nationality (Table 2).

Table 2.

The prevalence of TTV infection in a natural village in Yunnan Province, regarding of sex, nationality and age

| Result |

Sexa |

Nationalityb |

Agec |

|||||||

| Male | Female | Total | Han | Yi | Total | < 14 | 14-55 | > 55 | Total | |

| TTV positive | 7 | 12 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 19 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 19 |

| TTV negative | 83 | 77 | 160 | 82 | 78 | 160 | 47 | 102 | 11 | 160 |

| Total | 90 | 89 | 179 | 90 | 89 | 179 | 52 | 115 | 12 | 179 |

| Prevalence (%) | 7.8 | 13.5 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 12.4 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 8.3 | 10.6 |

χ2 = 1.535, P > 0.2;

χ2 = 0.568, P > 0.4; cχ2 = 0.178, P > 0.9.

Patients with cryptogenic hepatitis

The prevalence of TTV infection in patients with cryptogenic hepatitis was 38.63% (17 of 44). Two of the TTV-infected patients with fulminant hepatic failure, while the others with mild hepatitis.

Patients with HBV related chronic liver disease

The prevalence of TTV infection of AsC, CHB, ALC, CHF and HCC was 9.62% (5/47), 15.22% (7/39), 22.5% (9/31), 23.08% (9/30) and 9.52% (2/19), respectively. It seemed that the state of illness was related with the co-infection of TTV. However, there was no statistical difference between the prevalences (Table 1).

Effect on liver function test of TTV co-infection

Whileco-infected with TTV, the state of illness did not exacerbate in patients with CHB (Table 3). In patients with active liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatic failure, there were no significant differences in results of laboratory tests in patients with and without TTV DNA (P > 0.2) whereas the co-infection of TTV increased the mortality of patients with hepatic failure (P = 0.038).

Table 3.

Effect on liver function test of TTV co-infection in patients with chronic hepatitis B

| Liver function test | TTV negative | TTV positive | t value | P value |

| ALT (U/L) | 347.0 ± 286.5 | 282.3 ± 230.2 | 0.523 | > 0.5 |

| AST (U/L) | 199.9 ± 171.8 | 140.8 ± 105.3 | 0.742 | > 0.2 |

| Protein A/G | 1.24 ± 0.28 | 1.26 ± 0.12 | 0.140 | > 0.5 |

| TBil (μmol/L) | 34.1 ± 30.6 | 22.8 ± 9.3 | 0.883 | > 0.2 |

| Prothrombin (s) | 17.7 ± 5.5 | 15.6 ± 1.53 | 0.783 | > 0.2 |

DISCUSSION

The recent discovery in Japan by Nishizawa et al[7] of a novel parenterally transmissible, unenveloped, single-stranded DNA virus (TTV) in patients with non-A-G posttransfusion hepatitis had raised some important questions about TTV as a potential cause of liver disease.

Previous study indicated that TTV infection was common in healthy individuals, blood donors, HBsAg AsC, patients on hemodialysis and patients with various liver diseases, however played a minimal role on liver disease[17-26]. Another paper suggested TTV may cause chronic hepatitis in a limited number of patients, but remains dormant most of the time[27]. In our study, we found 10.61% of healthy individuals with normal liver function test were infected with TTV, and the prevalence was independent of sex, age and nationality. The result indicated TTV infection was common in healthy individuals. However, frequency of TTV infection in patients with cryptogenic hepatitis was significantly higher. As evidence of potential hepatotropism of TTV had been reported with TTV-DNA titers shown to be 10 to 100 folds greater in liver tissue than in serum[11,12], TTV would account for part of the reason for patients with cryptogenic hepatitis. As we know that there are many HBsAg AsC, whereas HBV causes many hepatitises. This study suggested that the majority of individuals with TTV could be asymptomatic carriers, with only a small proportion of carriers actually developing hepatitis.

Generally, co-infection of hepatitis virus would lead to exacerbation of hepatitis. While co-infected with hepatitis A and B virus, patients encountered exacerbation of illness, with more severe abnormal results of laboratory tests and higher mortality[28]. In histopathological evaluation, co-infection of hepatitis virus had no significant difference in development of liver cirrhos is[29]. Previous study indicated that superinfection of TTV does not exert deleterious effects on the liver disease induced by HCV. Triple infection, HCV and TTV plus HBV or HGV, did not cause severe liver disease[27]. In current study, prevalence of TTV infection in HBsAg AsC and patients with chronic hepatitis B, HBV related liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatic failure was 9.62%, 15.22%, 22.5% and 23.08% respectively. There was no significant difference among prevalence of TTV infection, suggesting the minor effect on liver disease of co-infection of TTV. The comparison of levels of ALT, AST, total bilirubin, A/G of serum protein and prothrombin time between TT virus-positive and-negative patients did not show any differences, as accorded with another report[30]. However, TTV co-infection increased the mortality of patients with hepatic failure.

Most cases of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC in developed countries are caused by HBV or HCV infections and heavy alcohol intake. A relatively small proportion of liver diseases is of unknown etiology. The recently discovered HGV seems to have no actual role in causing acute or chronic liver disease[31], whereas the role of the more recently discovered TTV is still to be defined. To inquire the relationship between TTV infection and HCC, we investigated the prevalence of TTV infection in HBV infected patients with HCC, and compared with HBsAg AsC. The result indicated similar prevalence in both cohorts (9.52% vs 9.62%, P > 0.9), which did not support the hypothesis of an association between TTV infection and HCC, and accorded with previous studies[32,33]. Another report indicated that TTV was not specific for HBV-negative and HCV-negative patients with HCC. For all TTV-positive patients, the TTV genome was not integrated into host hepatocyte DNA[34]. In conclusion, TTV was common in general population and several cohorts of liver disease. Though the majority of individuals with TTV could be asymptomatic carriers, TTV would account for part of cryptogenic hepatitis. As TTV co-infection did not affect the state of HBV infection, further study on pathogenic effect on liver disease of TTV infection should be continued.

Footnotes

Supported by Science Fund of Military Medical Science for the Ninth Five-Year Key Research, No.98Z073

Edited by Ma JY

References

- 1.Kodali VP, Gordon SC, Silverman AL, McCray DG. Cryptogenic liver disease in the United States: further evidence for non-A, non-B, and non-C hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Filippi F, Romeo R, Rumi MG, Donato MF, Del Ninno E, Colombo M. Low prevalence of HGV RNA in Italian patients with non A-E chronic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1996;24:499A. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita K, Oketani M, Oketani K, Yamauchi K, Sho Y, Arima T, Mawatari F, Hasegawa S, Komorizono Y, Ishimaru K, et al. Cryptogenic severe chronic liver dis-eases in South Japan. Hepatology. 1996;24:600A. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamid S, Jafri W, Khurshid M, Jarvis L, Shah H, Abbas Z, Sultana T, Siddiqui AA, Khan H, Simmonds P. Hepatitis G in the devel-oping world: impact of HGV on liver disease in Pakistan. Hepatology. 1996;24:520A. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aikawa T, Sugai Y, Okamoto H. Hepatitis G infection in drug abusers with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:195–196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601183340316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter HJ, Nakatsuji Y, Melpolder J, Wages J, Wesley R, Shih JW, Kim JP. The incidence of transfusion-associated hepatitis G virus infection and its relation to liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:747–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo KX, Zhang L, Wang SS, Nie J, Ge Y, Chen ZY, Yu SY, Liu YY, Yang SC, Liang WF, et al. An outbreak of enteric transmit-ted non A, non E viral hepatitis: primary study of clinical epide-miology and virology. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 1998;6:161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei LP, Liao DX, Liang WF. Investigation of an outbreak of new type of hepatitis in Gaoming of Guangdong Province. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:175–176. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang SS, Wu CH, Chen TH, Huang YY, Huang CS. TT viral infection through blood transfusion: retrospective investigation on patients in a prospective study of post transfusion hepatitis. World J Gastroentero. 2000;6:70–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamoto H, Nishizawa T, Kato N, Ukita M, Ikeda H, Iizuka H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Hepatol Res. 1998;10:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu DJ, Lang ZW, Wang GY, Yan HP, Xu RP, Li DF, Zhou YS, Wang HT. Detec tion of TTV DNA in liver tissue of patients with non A-G hepatitis. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 1999;7:96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge Y, Ren XF, Li DZ, Hu TH, Yang Q. Liver histologic characteristics of patients with TTV infection during an epidemic of TTV infection in Wuhan. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:1029–1030. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naoumov NV, Petrova EP, Thomas MG, Williams R. Presence of a newly described human DNA virus (TTV) in patients with liver disease. Lancet. 1998;352:195–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlton M, Adjei P, Poterucha J, Zein N, Moore B, Therneau T, Krom R, Wiesner R. TT-virus infection in North American blood donors, patients with fulminant hepatic failure, and cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;28:839–842. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Protocol of prevention and treatment for viral hepatitis. Zhonghua Chuanranbing Zazhi. 1995;13:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen TY, Zhang SL. Prognosis in TTV studies. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:420–421. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu EQ, Bai XF, Pan L, Li GY, Yang WS, Tang YM, Wang PZ, Sun JF. Investigation of TT virus infection in groups of defferent people in Xi'an. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:967–969. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu JG, Han JJ, Xiao DM, Yin YM, Shang QH, Zhou XM, Du QL, Zhang GS. Investigation of TTV infection and partial sequence analysis of TTV DNA in Shandong. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2000;8:352–354. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Wang YC, Zhang HY, Li HM. TTV infection in various kind of populations in China. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:497–498. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen XJ, Peng XM, Gao ZL, Lu JX, Yao JL. The significance of TTV infection in normal population and patients liver diseases. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CH, Zhou YS, Chen RG, Xie CY, Wang HT. The prevalence of transfusion transmitted virus infection in blood donors. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:268–270. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao JH, Chen W, Hsiang SC, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Prevalence and implication of TT virus infection: minimal role in patients with non-A-E hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1999;59:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<307::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forns X, Hegerich P, Darnell A, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Bukh J. High prevalence of TT virus (TTV) infection in patients on mainte-nance hemodialysis: frequent mixed infections with different genotypes and lack of avidence of associated liver disease. J Med Virol. 1999;59:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe K, Inami T, Asano K, Miyoshi C, Masaki N, Hayashi S, Ishikawa Ki, Takebe Y, Win KM, El-Zayadi AR, et al. TT virus infection is widespread in the general populations from different geographic regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2703–2705. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2703-2705.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh SY, Wu YH, Ho YP, Tsao KC, Yeh CT, Liaw YF. High prevalence of TT virus infection in healthy children and adults and in patients with liver disease in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1829–1831. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1829-1831.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeuchi T, Okuda K, Yokosuka O, Kanda T, Kobayashi S, Murata M, Hayashi H, Yokozeki K, Ohtake Y, Kashima T, et al. Superinfection of TT virus and hepatitis C virus among chronic haemodialysis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:796–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keeffe EB. Is hepatitis A more severe in patients with chronic hepatitis B and other chronic liver diseases? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colombari R, Dhillon AP, Piazzola E, Tomezzoli AA, Angelini GP, Capra F, Tomba A, Scheuer PJ. Chronic hepatitis in multiple virus infection: histopathological evaluation. Histopathology. 1993;22:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi K, Fukuda Y, Hayakawa T, Kumada T, Nakano S. [TT virus(TTV) infection in patients with acute hepatitis] Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:1322–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theodore D, Lemon SM. GB virus C, hepatitis G virus, or human orphan flavivirus? Hepatology. 1997;25:1285–1286. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tagger A, Donato F, Ribero ML, Binelli G, Gelatti U, Portera G, Albertini A, Fasola M, Chiesa R, Nardi G. A case-control study on a novel DNA virus (TT virus) infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. The Brescia HCC Study. Hepatology. 1999;30:294–299. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu T, Moriyama M, Matsumura H, Arakawa Y. [TT virus infection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma associated with non-A to G hepatitis: histopathological study] Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:1381–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto T, Kajino K, Ogawa M, Gotoh I, Matsuoka S, Suzuki K, Moriyama M, Okubo H, Kudo M, Arakawa Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinomas infected with the novel TT DNA virus lack viral integration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:339–343. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]