Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is the commonest cancer affecting women in Malawi, which has the highest rate of this disease in the world. Most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Aim

To describe the symptom burden, palliative care interventions, and outcomes of cervical cancer patients who entered care at Tiyanjane Clinic in Blantyre, Malawi, between January and December 2012.

Methods

We reviewed the case files of 72 patients presenting to our hospital-based palliative care service over one year.

Results

The mean age was 49.5 years. Twenty-six patients (36%) were HIV-positive and the majority of these (n = 22; 85%) were on antiretroviral medication at presentation to palliative care. Pain (n = 66; 92%), vaginal discharge (n = 44; 61%), and unpleasant odour (n = 37; 51%) were commonly reported. Over a third of patients (n = 26; 36%) reported pain in two or more sites. Fourteen patients (19%) reported vaginal bleeding. Spousal breakdown (through widowhood or divorce) was noted in over half (n = 41; 57%) of all cases. Pain relief was provided to 69 (96%) of the patients (morphine to 40 patients; 56%). Common interventions provided included metronidazole tablets (used vaginally), sanitary items, and counselling. At the end of the study period, 18 patients (25%) were still under the care of palliative services.

Conclusions

Access to medications such as morphine, metronidazole and tranexamic acid can improve quality of life, even when radiotherapy is limited. Health care teams require necessary skills and training, including how to perform a comprehensive assessment, with an emphasis on the provision of psychosexual counselling, to assist with the complexity of symptoms occurring in this vulnerable group.

Introduction

Cancer of the cervix is the leading cause of cancer death among African women. According to statistics from the World Health Organisation (WHO), Malawi has the world's highest age-standardised rate for both incidence (76 per 100,000) of cervical cancer and mortality (50 per 100,000) from the disease.1 In Africa, for a variety of reasons, women with cancer of the cervix are often diagnosed late, requiring a palliative approach from the time of presentation. Opportunities for screening may be missed,2 and delivery of screening services is beset by multiple challenges.3 Invasive cancer of the cervix is categorised as a WHO stage IV AIDS-defining condition. This means that all women with this condition who test positive for HIV qualify automatically to start on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), irrespective of CD4 count.4 In Malawi, there is a well-organised country-wide system for HIV testing and initiation of antiretroviral medication.5 Radiotherapy, a commonly utilised treatment modality for the palliative management of patients with cancer of the cervix,6 is not yet available, unless patients travel outside the country.

Tiyanjane Clinic started in 2003 and currently runs hospital-based (inpatient and outpatient) and community-based palliative care services from Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), along with a home-based care service from Ndirande Health Centre. Service delivery is integrated into the public sector, with supplementary external funding utilised to boost capacity. There are currently 10 Tiyanjane staff members: four nurses, three clinicians, and three support staff. The team have around 300 patient contacts per month. Patients with cancer of the cervix are referred to Tiyanjane Clinic from the gynaecology unit, as well as from other sites within and outside the hospital.

The WHO and other international bodies, such as the African Palliative Care Association (APCA), have highlighted the importance of palliative care. The literature, however, remains sparse on the specifics of the symptom burden and what interventions palliative care services offer in daily practise.7

This study was undertaken in order to describe the symptom burden, palliative care interventions, and outcomes of cervical cancer patients who entered care at Tiyanjane Clinic between January and December 2012.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective review of case notes of new patients with cervical cancer who presented between January and December 2012. Eligible patients were identified from Health Managment Information System (HMIS) records, and their Tiyanjane case files were retrieved manually.

Information concerning demographics (including HIV-related data) and symptom burden at the time of their initial assessment presentation were collated. Follow-up appointment notes were reviewed, with any interventions offered, as well as outcome at the last reported follow-up (within the study period) recorded. Data were analysed using SPSS Version 20. Ethical permission to undertake this study was obtained from the University of Malawi's College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC).

Results

Between January and December 2012 Tiyanjane Clinic staff saw a total of 1107 new patients. Eighty-seven (8%) had cancer of the cervix. Of these, 72 (83%) case files were located and included in the analysis.

Age distribution of patients with cancer of the cervix

The ages of study participants ranged from 20 to 80 years, with a mean age of 49.5 years and a modal age of 40 years.

Social status and HIV infection

Demographic data from this case file review revealed that more than half of women with cancer of the cervix did not have spouses: 15 (21%) were divorced and 26 (36%) were widowed.

Twenty-six (36%) of the study participants were HIV-positive and, of these, 4 (15%) were not on HAART at the time of first presentation to palliative care services. At presentation to palliative care services, 17 (24%) of the patients were of uknown HIV status.

Physical symptom burden

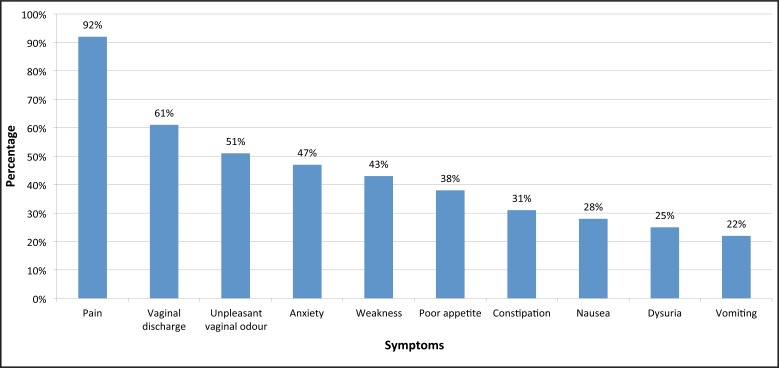

Pain was the most common presenting symptom, found in 66 patients (92% ). Over a third (26 patients; 36%) had pain in two or more different sites. For the most severe pain felt, as reported by the patients, the modal score was 4 (using a pain scale of 0–5). Vaginal discharge (44 patients; 61%) and unpleasant odour (37 patients; 51%) were commonly reported, and 14 patients (19%) reported vaginal bleeding. The average number of symptoms per patient was 4, with a range of 1 to 11.

Palliative care interventions

Pain medication was provided to 69 patients (96%). Forty patients (56%) were prescribed morphine. Other drugs used included metronidazole for 38 patients (53%) and oral tranexamic acid tablets to control vaginal bleeding in 6 patients (8%). Sanitary pads were provided to 21 (29%) of the women.

After provision of analgesia, counselling was the next most frequently recorded intervention. Sixty-six patients (92%) received counselling on disease understanding, 62 (86%) on spiritual needs, and 58 (81%) on HIV and sexuality.

Outcomes

At the end of one year, 18 patients (25 %) were still under review at the palliative care clinic, 24 (33%) of the patients were lost to follow-up, and 8 (11%) were recorded to have died during the period under review. Of the others, 8 (11%) moved out of the district and 5 (7 %) were referred to another palliative care unit within the district.

Discussion

This case note review provides an insight into the routine palliative care case management of patients with advanced cervical cancer at QECH's Tiyanjane Clinic in Blantyre, Malawi, where access to radiotherapy is limited.

Pain was the most common symptom reported in this case file review, as similarly reported in literature from other African settings.8 It is recognised that pain is experienced throughout the cancer journey, with pain prevalence and severity likely to increase as the disease advances. Such pain is commonly undertreated, even in settings where a variety of opioids plus alternative approaches to drug management of pain exist. Over half of the patients in our case review required morphine to manage their pain. This is similar to the findings of Herce et al. in their rapid evaluation of palliative care services established in Neno district in rural Malawi.9 In many countries, access to morphine has been a rate-limiting step in palliative care expansion. Through partnership and sustained advocacy, Malawi is reported to have had some success in improving the adequacy of morphine supply,10 though prolonged stockouts are still experienced at many hospitals across the country (Palliative Care Association of Malawi Drug Advocacy Officer, 2015, personal communication). Other medication and supplies, such as tranexamic acid and sanitary pads, are not routinely available through public health services; Tiyanjane Clinic purchases these items using well-wisher donations. Following WHO guidelines, oral metronidazole tablets as vaginal pessaries are utilised to reduce the smell of discharge.11

Alongside the provision of symptom control drugs, counselling and education were the most commonly recorded interventions. Topics that are covered by the team include education relating to HIV issues and advice on how best to provide appropriate sexual satisfaction to support the sexual needs of the relationship. Disease understanding and advanced planning may be explored, guided by the wishes of the patient and their carers. For such concerns to be confidently disclosed and discussed, advanced counselling skills and an appropriate environment are required.

HIV infection is known to be associated with an increased risk of developing cervical cancer. Our case note review recorded that one quarter of patients were of unkown HIV status at the time of presentation to our palliative care service. However, most of the patients who were known to be HIV-positive (22 patients; 85%) were already taking antiretroviral medication. Discussion of the need for HIV testing and provision of HAART plays a role in palliative care consultation in Malawi and similar settings of high HIV prevalence, with care taken to deliver suitable messages to the patient and her partner (if present) about safe sexual practises.

Notably, patients with advanced cancer of the cervix attending palliative care services at QECH had a high rate of loss of spousal support, with 40 women (56%) in this case review either widowed or divorced. Data from national surveys (Malawi Demographic Health Survey 2010), in a younger population, show that less than 10% of women aged 15 to 49 years are divorced (4.9%) or widowed (3.6%).

It is concerning that our study reports a high loss to follow-up (24 patients; 33%) during the period under review. Similar findings were reported in our earlier published audit of inpatient palliative care at QECH.12 In 2012 Tiyanjane Clinic had a motorbike and a shared car with which to conduct visits to patients' homes within a 50 km radius from the hospital. This capacity is limited. Improving mobile outreach services and active case finding of non-attendees and would enable Tiyanjane Clinic to provide care for women even when they can no longer manage (either physically or financially) to get to the health facility.

As a retrospective case note review, this study was not able to assess the efficacy of pain medication or other interventions. Additionally, the precise detail of the holistic concerns of patients and their families could not be ascertained. Further prospective qualitative and quantitative studies are required to investigate these important areas.

Conclusions

This paper reports the common symptoms experienced by women with advanced cancer of the cervix attending palliative care services at QECH, the interventions received, as well as outcomes. Palliative care services at QECH support patients and families through a significant part of their illness journey. Pain is common and frequently severe, with over half of women requiring oral morphine. Vaginal discharge, odour, and bleeding can be managed using safe, inexpensive medications and supplies. Loss to follow-up from our central teaching hospital palliative care service is significant.

Africa is set to see continuing expansion in the numbers of patients with cancer, many of whom are diagnosed once their disease is at a late stage. All women with advanced cancer of the cervix need access to HIV testing, and those who test HIV-positive require HAART. Health systems must provide access to suitable medications such as morphine, metronidazole, and tranexamic acid, which can improve quality of life even when access to radiotherapy is limited. Health care teams require necessary skills and training, including how to perform a comprehensive assessment, with an emphasis on the provision psychosexual counselling.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of study patients

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients presenting with the 10 most common presenting symptoms

Table 1.

Marital and HIV status data of study patients

| HIV positive | HIV negative | HIV status unknown |

Total | |

| Married | 11 | 16 | 4 | 31 |

| Widowed | 12 | 7 | 7 | 26 |

| Divorced | 3 | 6 | 6 | 15 |

| Total | 26 | 29 | 17 | 72 |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge J. Mtonga and S. Mamba for their invaluable contributions to this work.

References

- 1.2014 Africa Cervical Cancer Incidence & Mortality Multi Indicator Scorecard [Internet] London: Africa Health, Human & Social Development Information Service; 2014. [cited 2014 Oct 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2014/africa_cancer_mortality.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taulo F, Malunga E, Ngwira A. Audit of gynaecological cancers Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre. Malawi Med J. 2008 Dec;20(4):140–142. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v20i4.10974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS. Health systems challenges in cervical cancer prevention program in Malawi. Glob Health Action. 2015 Jan 22;8:26282. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.26282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Malawi, author. Clinical management of HIV in children and adults: Malawi integrated guidelines for providing HIV services in antenatal care, maternity care, under 5 clinics, family planning clinics, exposed infant/pre-ART clinics, ART clinics [Internet] Lilongwe: Ministry of Health, Malawi; 2011. [cited 2015 Aug 4]. 79 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/malawi_art.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, Mwaungulu F, Mvula H, Munthali F, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Lancet. 2008 May 10;371(9624):1603–1611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eze JN, Emeka-Irem EN, Edegbe FO. A six-year study of the clinical presentation of cervical cancer and the management challenges encountered at a state teaching hospital in southeast Nigeria. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2013 Jun 27;7:151–158. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.African Palliative Care Association, author. Palliative care for women living with HIV and cervical cancer [Internet] Kampala: African Palliative Care Association (APCA) and Open Society Initiative of Southern Africa (OSISA); 2013. [cited 2014 Oct 20]. 24 p. Available from: http://www.osisa.org/sites/default/files/pc_and_cervical_cancer_in_wlwh.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding R, Selman L, Agupio G, Dinat N, Downing J, Gwyther L, et al. The prevalence and burden of symptoms amongst cancer patients attending palliative care in two African countries. Eur J Cancer. 2011 Jan;47(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herce ME, Elmore SN, Kalanga N, Keck JW, Wroe EB, Phiri A, et al. Assessing and responding to palliative care needs in rural sub-Saharan Africa: results from a model intervention and situation analysis in Malawi. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 14;9(10):e110457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duthey B, Scholten W. Adequacy of opioid analgesic consumption at country, global, and regional levels in 2010, its relationship with development level, and changes compared with 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 Feb;47(2):283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization, author. Palliative care: symptom management and end-of-life care— integrated management of adolescent and adult illness: interim guidelines for first-level facility health workers [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [cited 2015 Feb 15]. 50 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapsfield JB, Bates MJ. Hospital based palliative care in sub- Saharan Africa; a six month review from Malawi. BMC Palliat Care. 2011 Jul 9;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]