Highlights

-

•

Bevacizumab was an effective agent in one case of advanced uterine PNET.

-

•

VEGF was expressed by the tumor, supporting a mechanism for effectiveness.

-

•

Cisplatin/etoposide/bevacizumab should be further studied in clinical trials.

-

•

Patient remains disease-free forty-eight months following intervention.

Keywords: Primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Uterine neoplasm, Uterine PNET, Central-type PNET, cPNET, Bevacizumab

1. Introduction

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are rare neoplasms that can occur in the female genital tract, among other visceral sites. The most common location within the female genital tract is the ovary, followed by the uterine corpus (Euscher et al., 2008), vagina, and cervix (Snijders-Keilhotlz et al., 2005).

PNETs can present in pure form or admixed with other components, including endometrioid adenocarcinoma, adenosarcoma, carcinosarcoma (metaplastic carcinoma), and heterologous sarcomas (Nogales, 2003, Bartosch et al., 2011). When considering PNET as a diagnosis, the differential should include poorly-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma, non-keratinized squamous cell carcinoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, lymphoma, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, and metastasis.

To date, over 58 cases of uterine PNETs have been published in the literature, the largest being a seventeen-patient case series by Euscher et al. (2008). While these cases share the same diagnosis, they vary in their presentation, management, and outcomes (Table 1). We report an additional case of cPNETs of the uterine corpus, with this being the first case treated with surgical debulking and adjuvant cisplatin, etoposide and bevacizumab, with no evidence of disease recurrence forty-eight months following intervention.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, surgical management, adjuvant chemotherapy, and follow-up of reported cases of uterine PNET.

| Author | Age | Initial sign/symptom | FIGO stage | Surgery | Chemotherapy | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartosch et al. (2011) | 58 | Vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, weight loss | IV | TAH, BSO, segmental enterectomy, total colectomy, right PLND | Carboplatin Paclitaxel |

Died, 11 months with sepsis from pyelonephritis |

| Celik et al. | 32 | Abdominal pain, pelvic mass | IIIA | TAH, BSO, PLND, PALND, omentectomy, appendectomy | Cisplatin Ifosfamide Adriamycin Vincristine (PIAV) |

NED, 38 months |

| Bhardwaj et al. | 50 | Vaginal bleeding, pelvic mass | IIIC | TAH, BSO, omentectomy, PLND | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | NED, 6 months |

| Odunsi et al. (2004) | 66 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO, omentectomy, PLND, PALND | Not done | NED, 2 years |

| Odunsi et al. (2004) | 65 | Vaginal bleeding | IIIC | TAH, BSO, omentectomy, PLND, PALND, upper vaginectomy | Cisplatin Doxorubicin Etoposide Paclitaxel |

Lung metastasis, 3 months AWD, 12 months |

| Karseladze et al. | 16 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO, omentectomy | Vincristine Cyclophosphamide Doxorubicin |

NED, 4 years |

| Hendrickson and Scheithauer | 12 | Vaginal bleeding, pelvic mass | IVB | TAH, LSO | Cyclophosphamide Doxorubicin Vincristine |

Pelvic recurrence, 12 months DOD, 2 years |

| Hendrickson and Scheithauer | 57 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine mass | IIB | TAH, BSO, PALND | Cisplatin Vinblastine Bleomycin |

Lung metastasis, 5 months DOD, 2 years |

| Rose et al. Ward et al. |

17 | Vaginal bleeding, pelvic mass | IIIC | RH, PLND, bilateral ovarian wedge biopsy | Vincristine Cisplatin Doxorubicin Dactinomycin Cyclophosphamide Etoposide |

NED, > 10 years |

| Daya et al. | 67 | Vaginal bleeding, enlarged uterus | IIIC | SCH, BSO | Cisplatin Doxorubicin Carboplatin 5-FU |

Persistent DOD, 6 months |

| Daya et al. | 68 | Vaginal bleeding, enlarged uterus | IVB | TAH, BSO, PLND | Cisplatin | Persistent DOD, 12 months |

| Daya et al. | 69 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO, PLND | Not done | NED, 6 years |

| Daya et al. | 68 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO | Not done | NED, 5 years |

| Molyneux et al. | 72 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO | Not done | DOD, 8 months |

| Fragetta et al. | 78 | Vaginal bleeding | IB | TAH, BSO, PLND | Not done | NED, 9 months |

| Sorenson et al. | 62 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO | Vincristine Cyclophosphamide Cisplatin |

DOD, 18 months |

| Taieb et al. | 36 | Uterine enlargement | I | RH, BSO, PLND | Not done | NR |

| Ng et al. | 48 | Vaginal bleeding | IIIC | TAH, BSO | Not done | |

| Blattner et al. (2007) | 26 | Pelvic mass noted at cesarean section | III | RH, PLND, bilateral ovarian transposition | Vincristine Doxorubicin Cyclophosphamide Etoposide |

NED, 16 months |

| Mittal et al. (2007) | 24 | Fever, abdominal pain, pelvic mass | II | TAH, BSO, omentectomy | Vincristine Doxorubicin Cyclophosphamide Ifosfamide Etoposide |

Recurrence, 1 months |

| Akbayir et al. | 22 | Vaginal bleeding, adnexal mass | I | TAH, BSO, PLND, PALND, omentectomy | Cisplatin Doxorubicin |

NED, 10 months |

| Peres et al. | 15 | Abdominal pain, fever, pelvic mass | I | TAH, PLND | Carboplatin Etoposide |

NED, 12 months |

| Varghese et al. (2006) | 43 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine enlargement | IIIC | TAH, BSO, PLND | Cytoxan Adriamycin Vincristine Etoposide |

NED, 2 months |

| Park et al. | 30 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine enlargement | IVB | None | Vincristine Doxorubicin Ifosfamide Carboplatin Etoposide |

DOD, 16 months |

| Shah et al. (2009) | 59 | Vaginal bleeding, pelvic mass | IIIC | TAH, BSO, PLND, PALND, omentectomy | Paclitaxel Carboplatin |

AWD, 12 months |

| Majeed et al. | 27 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine mass | NR | TAH/BSO | Vincristine + Etoposide + Doxorubicin + Ifosfamide/ Vincristine + Ifosfamide |

NED, 2 years |

| Ren et al. | 56 | Vaginal bleeding | IB | TAH, BSO, PLND | Ifosfamide Etoposide Cisplatin |

NED, 41 months |

| Fukunaga et al. | 54 | Unknown | NR | TAH, BSO | Cyclophosphamide Cisplatin Doxorubicin 5-FU |

AWD, 3 months |

| Venizelos et al. | 68 | Vaginal bleeding | I | TAH, BSO | Not done | NED, 10 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 58 | Vaginal bleeding with palpable mass | IIIC | Unknown surgery | Not done | DOD, 2 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 31 | Back pain from metastatic disease | IV | Not done | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | DOD, 20 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 72 | Vaginal bleeding | IA | Unknown | Unknown | DOD, 11 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 48 | Unknown | IIIC | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 81 | Vaginal bleeding | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 66 | Pelvic mass | IIIC | Unknown surgery | Letrozole | NED, 41 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 53 | Vaginal bleeding | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | DOD, 22 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 51 | Vaginal bleeding | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | DOD, 12 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 31 | Vaginal bleeding | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | DOD, 26 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 64 | Cervical polyp | IIB/ possible IIIC |

TAH, BSO | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | NED, 36 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 64 | Vaginal bleeding with pain | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 69 | Vaginal bleeding | IV by imaging | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 62 | Uterine fibroids | IIIC | Unknown | Unknown | DOD, 22 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 55 | Vaginal bleeding with fibroids | IB | TAH, BSO | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | NED, 38 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 52 | Unknown | IV | Unknown | Unknown | NED, 6 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 58 | Vaginal pressure with passage of tissue | IV | Not done | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | NED, 6 months |

| Euscher et al. (2008) | 57 | Unknown | IIIC | Not done | Unknown chemotherapy regimen | NED, 35 months |

| Stolnicu et al. | 12 | Vaginal bleeding with passage of tissue | Unknown | Not done | Etoposide, Bleomycin, Cisplatin | NED, 36 months |

| Vignali et al. | 31 | Vaginal bleeding, intermittent abdominal pain | IIIC | Unknown | Cisplatin, Etoposide | NED, 24 months |

| Cate et al. | 25 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine inversion and prolapse | Unknown | TAH | Not done | NED, 18 months |

| Dizon et al. | 50 | Abdominopelvic pain | Unknown | TAH, BSO, omentectomy, | Carboplatin, Etoposide | NED, 16 months |

| Shimada et al. | 63 | Constipation | Unknown | TAH, BSO | Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Adriamycin | NED, 24 months |

| Yi et al. | 29 | Abdominal swelling and pain | IVB | TAH, BSO, PALND, PLND, omentectomy | Neoadjuvant docetaxel and carboplatin. Vincristine, Adriamycin, Cyclophosphamide |

AWD, 18 months Liver metastasis |

| Aminimoghaddam et al. | 32 | Vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain | TAH, BSO, PLND | Holoxan, Mesna, Cisplatin, Paclitaxol, Carboplatin | AWD, unknown | |

| Current case | 26 | Vaginal bleeding, uterine mass | IV | TAH, BSO, omentectomy, PLND | Carboplatin Etoposide Avastin |

NED, 48 months |

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; LSO, left salpingo-oophorectomy; DOD, died of disease; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; PALND; pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection; RH, radical hysterectomy; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; NED, no evidence of disease; SCH, supracervical hysterectomy; AWD, alive with disease; NR, not recorded.

2. Case report

A 26 year-old nulligravid, Hispanic female presented to an outside institution with dysfunctional uterine bleeding for four months. She was treated with oral contraceptives without resolution of her symptoms. A transvaginal ultrasound was performed, which showed an enlarged uterus with a 5.7 × 7 × 7 cm homogenous mass located within the lower uterine segment, as well as an enlarged right ovary. An endometrial biopsy showed endometrial tissue with possible small cell neuroectodermal tumor. The patient was then referred to our institution where a repeat endometrial biopsy showed high-grade malignant tumor infiltrating cervical tissue, favoring PNETs. A computed tomography (CT) study demonstrated a large uterus measuring up to 8.2 cm in width with a 5.8 × 4.2 cm mass within the myometrium, a 4.1 cm cystic lesion in the right adnexa, ascites, a left-sided pleural effusion, and mildly enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes. Dilatation and curettage were performed, and pathologic examination revealed a high grade malignant tumor, favoring PNETs. The patient then underwent an exploratory laparotomy with radical tumor debulking, total abdominal hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and removal of tumor from the posterior cul-de-sac. Intra-operative findings were consistent with stage IV uterine cancer. Although the patient was optimally surgically debulked, there was still residual tumor measuring less than 1 cm at the conclusion of the procedure.

2.1. Pathology

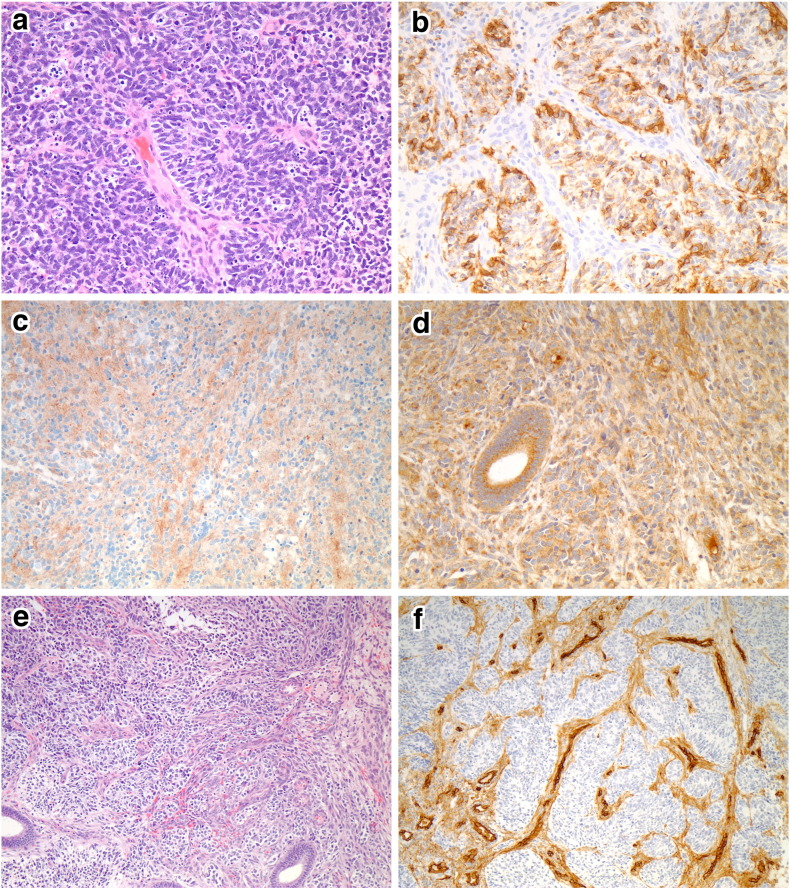

On gross examination, the uterus contained an exophytic 7.1 × 6.0 × 2.6 cm white-tan marbled mass with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis, occupying the entirety of the endometrial cavity, and infiltrating the full thickness of the myometrium (2.6 cm). In addition, the mass involved both right (7.1 × 5.5 × 2.5 cm) and left ovaries (4.8 × 2.6 × 2.4 cm), with extension from the fallopian tubes. Hematoxylin and eosin microscopic examination showed a proliferation of sheets and nests of cells with round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei, finely granular chromatin, conspicuous multiple nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. Homer-Wright rosettes and pseudo-rosettes were frequently observed (Fig. 1a). Widespread lymphovascular invasion was present, and mitotic figures were common (48/10 high power fields). Immunohistochemical stains demonstrated that the tumor cells were negative for CK 8/18, CK AE1/3, CD10, CD34, desmin, MSA, Myf-4, GFAP, chromogranin, neurofilament, CD99 and FLI1. Positive stains included vimentin, CD56, NSE, and synaptophysin (Fig. 1b–c). Antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (VG1 clone, Novus) showed positive cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 1d). In addition, CD34 and MSA highlighted a prominent network of endothelial cells within the sheets and nests of small hyperchromatic cells (Fig. 1e–f). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis using a LSI EWSR1 dual color, break-apart probe (Abbot Molecular) revealed no evidence of EWSR1 gene rearrangement.

Fig. 1.

The tumor was composed of small hyperchromatic cells with scant cytoplasm. Homer-Wright rosettes and pseudo-rosettes were present (a). The tumor cells were positive for CD56 (b), synaptophysin (c), and VEGF (d). A prominent vascular network was present (e), which is highlighted by CD34 (f).

2.2. Treatment

Following discussion of the patient's case at our institution's gynecologic oncology tumor board, the decision was made to treat the patient with six cycles of cisplatin and etoposide. Bevacizumab was added to the regimen for the second through sixth cycles given the finding of ascites. Response to treatment was followed with physical examination, serial CA-125 levels, and CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis.

Baseline CA-125 was 372 U/mL. CA-125 levels obtained prior to administration of the second through sixth cycles were 189 U/mL, 31 U/mL, 22 U/mL, 15 U/mL, and 15 U/mL respectively. Three months following the last cycle, the CA-125 level was 12 U/mL. Her most recent CA-125 was 10 U/mL, sixty-one months post-treatment.

A CT scan following the third cycle of cisplatin/etoposide/bevacizumab showed resolution of ascites and pleural effusion with mildly enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Three months after completion of chemotherapy, imaging showed stability of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes without evidence of disease. Her most recent scan, performed forty-eight months after completion of therapy, shows no evidence of recurrence.

2.3. Toxicity

The patient tolerated the chemotherapy with resultant Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Grade 3 nausea and vomiting which required hospitalization three times for IV hydration and IV antiemetics. Because of ECOG Grade 3 neutropenia, she was given pegfilgrastim on day 3 of each subsequent cycle. Given the patient's response to the chemotherapy regimen of cisplatin/etoposide/bevacizumab in treating her stage IV endometrial primitive neuroectodermal tumor, the patient was placed on surveillance. At sixty-two months following treatment, the patient is disease-free based on tumor markers, physical examination, and CT imaging studies.

3. Discussion

PNETs are small round cell tumors with glial, neural, and ependymal differentiation, thought to be derived from fetal neuroectodermal tissue (Hart & Earle, 1973). PNETs can be further classified based on degree of differentiation, location and genetic signatures into peripheral and central types. Peripheral-type PNET/Ewing sarcoma (pPNET/ES) is believed to originate from neural crest and occur outside of the central nervous system. Immunohistochemically, the great majority of pPNET/ES demonstrate CD99 and FLI1 positivity, and cytogenetics demonstrate the characteristic t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation and EWSR1/FLI1 gene fusion (Nogales, 2003, Varghese et al., 2006). cPNET/neuroblastoma are derived from the central neuraxis and involve central structures including the brain and spinal cord, and generally lack the EWSR1 gene rearrangement (Hart & Earle, 1973). The majority of primary uterine PNETs lack the EWSR1 gene translocation, as in our case, and therefore resemble a cPNET.

Uterine PNETs are rare tumors that typically present in postmenopausal women although a minority present in the second decade, highlighting a bimodal age distribution. Abnormal uterine bleeding is the most common presenting symptom, and a uterine mass the most common finding on exam. Uterine PNETs are frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, highlighting their aggressive nature. The two-year survival of younger patients and postmenopausal patients has been reported as 75% and 32%, respectively (Odunsi et al., 2004). Factors that portend a poor prognosis for the PNET family of tumors include metastatic disease at presentation (as confirmed by imaging, as well as cytologic and histologic examination of the bone marrow), primary extraosseous tumor, central or pelvic disease, age at diagnosis of 26 or older, tumor size greater than 8 cm, poor response to chemotherapy, absence of EWS-FLI1 fusion gene, and elevated pretreatment LDH (Mittal et al., 2007, Burchill, 2003).

There is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment of uterine PNETs. Patients treated with surgery and radiation have a relapse rate approaching 90% (Blattner et al., 2007). Multimodal therapy improves disease free survival, but the optimal chemotherapeutic regimen has not yet been demonstrated (Shah et al., 2009). Our patient underwent surgical management with optimal debulking as defined by measurable disease less than 1 cm followed by adjuvant chemotherapy alone. We chose to treat this patient with cisplatin and etoposide. Because the patient exhibited a large amount of ascites intraoperatively, as well as pleural effusion on post-operative imaging, the decision was made to add bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against VEGF, to this regimen. VEGF has been implicated as a stimulator of vascular permeability, a contributing factor to malignant ascites (Mesiano et al., 1998). Because she did not exhibit any evidence of disease following chemotherapy, she did not receive post-operative radiation.

Due to the rare nature of uterine PNET and few case reports in the literature, it is difficult to determine the optimal course of treatment. Because cases of PNET are so rare, it is also problematic to accurately predict rates of survival or recurrence of this particular type of malignant neoplasm. To date there have been no case reports in the literature using the combination of cisplatin/etoposide/bevacizumab for adjuvant treatment of uterine PNET. Bevacizumab has been previously shown to be a potential therapeutic modality in vitro (Dalal et al., 2005), and a case series exploring its therapeutic value in the management of recurrent medulloblastoma have yielded objective response rates (Aguilera et al., 2013). Oberstein et al. reviewed three phase II clinical trials employing bevacizumab in the management of pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas, including PNET, showing a partial response rate ranging from 0 to 56% and mean progression-free survival ranging from 4.2 months to 23.7 months (Oberstein & Saif, 2012).

The presence of neoplastic endothelial proliferation and VEGF positivity within the tumor provides a rational explanation to the effectiveness of this novel chemotherapy modality against uterine cPNET. This treatment option was tolerated by our patient with the side effects of Grade 3 nausea, which was supported with hospitalization and administration of IV fluids and antiemetics, and Grade 3 neutropenia, which was improved by the addition of pegfilgrastim and supportive care. Based on our patient's histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of this particular cPNET, and the favorable response to treatment using cisplatin/etoposide/bevacizumab, prospective clinical trials are required to evaluate the efficacy of this treatment schema in the management of advanced-stage uterine cPNET.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Euscher E.D., Deavers M.T., Lopez-Terrada D., Lazar A.J., Silva E.G., Malpica A. Uterine tumors with neuroectodermal differentiation: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. Feb 2008;32(2):219–228. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318093e421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders-Keilhotlz A., Ewing P. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the cervix: a case report — changing concepts in therapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;98(3):516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales F.T.F. Sex cord-like, neuroectodermal and neuroendocrine tumours, lymphomas and leukemias. In: DP T.G.A., editor. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs: WHO Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; Lyon: 2003. pp. 255–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch C., Vieira J., Teixeira M.R., Lopes J.M. Endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the uterus: a poor prognostic subtype of uterine tumours. Med. Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9579-z. (May 29, 2010. e-pub) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart M.N., Earle K.M. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the brain in children. Cancer. Oct 1973;32(4):890–897. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197310)32:4<890::aid-cncr2820320421>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese L., Arnesen M., Boente M. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus: a case report and review of literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. Oct 2006;25(4):373–377. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000215300.39900.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odunsi K., Olatinwo M., Collins Y., Withiam-Leitch M., Lele S., Spiegel G.W. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Gynecol. Oncol. Feb 2004;92(2):689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal S., Sumana G., Gupta M., Gupta B. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus: a case report. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. Mar–Apr 2007;17(2):524–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill S.A. Ewing's sarcoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications of molecular abnormalities. J. Clin. Pathol. Feb 2003;56(2):96–102. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner J.M., Gable P., Quigley M.M., McHale M.T. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus. Gynecol. Oncol. Aug 2007;106(2):419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J.P., Jelsema J., Bryant C.S., Ali-Fehmi R., Malone J.M., Jr. Carboplatin and paclitaxel adjuvant chemotherapy in primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterine corpus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Feb 2009;200(2):e6–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesiano S., Ferrara N., Jaffe R.B. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian cancer: inhibition of ascites formation by immunoneutralization. Am. J. Pathol. Oct 1998;153(4):1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65669-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S., Berry A.M., Cullinane C.J. Vascular endothelial growth factor: a therapeutic target for tumors of the Ewing's sarcoma family. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(6):2364–2378. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera D., Mazewski C., Fangusaro J. Response to bevacizumab, irinotecan, and temozolomide in children with relapsed medulloblastoma: a multi-institutional experience. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2013;29(4):589–596. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-2013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberstein P.E., Saif M.W. Update on novel therapies for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. JOP. 2012;13(4):372–375. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/964. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22797392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]