Abstract

Objective

Adolescent overweight and obesity and smoking continue to be very important health challenges because of their lasting affects on overall health. Weight gain after smoking cessation is a barrier to quitting as well as a consequence of health status. This study reports changes in the body mass index (BMI) z-scores of adolescent smokers participating in a dose-ranging clinical trial of bupropion SR (150mg/day and 300mg/day) for smoking cessation.

Methods

A total of N=296 adolescent smokers (placebo n=100, 150mg/day n=101, 300mg/day n=95) with a BMI z-score of 0.5 (sd: 1.4), 0.5 (sd: 1.3), and 0.5 (sd: 1.2) in the placebo, 150 mg/day and 300 mg/day groups, respectively, were followed for six months.

Results

Adolescents in the 300mg/day group had a significant reduction in BMI z-score at 6 week post quit (β = −0.16, CI= (−0.29, −0.04), p-value = 0.01). This result was not sustained at the six-month follow up.

Conclusion

A reduction in BMI z-score during smoking cessation with bupropion has important implications for the future of adolescent smoking cessation. These results are particularly relevant for adolescents who are either overweight or obese, or have reservations about quitting for fear of gaining weight or BMI.

Keywords: BMI z-score, Tobacco cessation, Adolescents, bupropion SR

Introduction

Adolescent smoking and the rise in rates of people with obesity top public health priorities. Sixteen percent of all adolescents have smoked in the last 30 days(1), which remains well above Healthy People 2020 goals. Over 20% of American adolescents are obese(2) and are at greater risk of serious health problems that continue into adulthood(3).

Furthermore, teen smoking and weight are related. This is not surprising since risk factors for poor health are often found in multiples(4). In particular, 92% of smokers engage in at least one other risky behavior(5), sometimes in the form of unhealthy eating behaviors. Solidifying this link, adolescents who are overweight and obese are more likely to smoke(6) and many adolescent smokers, regardless of BMI, do so to control their weight (7).

Unfortunately, when most people quit smoking they gain weight(8). Individuals and health providers face a difficult trade off when considering this fact. The health gains from quitting can be offset by the risks of increased body weight. On the other hand, continuing to smoke is clearly not a healthy option. Gaining weight is a barrier of cessation for adolescents, particularly girls(9). The reverse is also true; adolescents who are trying to lose weight are 30% more likely to be cigarette smokers (10). Approaches to smoking cessation that mitigate weight gain would be the optimal solution. In one study of nicotine replacement therapy for adolescent cessation, there was no difference in weight gain for those who quit at the end of the treatment(11) but measuring weight changes, rather than z-scores of body mass index (BMI) may not have adequately characterizing these changes(12). In adults, bupropion has shown to limit post-cessation weight gain(8). Understanding factors that contribute to BMI changes during cessation is an important part of future adolescent cessation research.

This study reports the change in BMI z-score of adolescents in a dose-ranging phase III clinical trial designed to test the efficacy of bupropion for smoking cessation.

Methods

We previously reported a study testing the efficacy of sustained-release bupropion hydrochloride for adolescent smoking cessation, clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00344695 (13). It was a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging phase III clinical trial of healthy, smoking adolescents. A total of 312 adolescents were recruited and randomly assigned to placebo (n=103), 150 mg/day (n=105), or 300 mg/day (n=104) SR bupropion hydrochloride. This paper reports on participants who had height and weight measurements at baseline.

Participants

Participants were adolescents between the ages of 14 to 17 years who smoked at least 6 cigarettes a day, exhaled carbon monoxide levels of over 10 ppm, had at least 2 past quit attempts, and met other inclusion criteria(13).

Treatment

Participants took bupropion SR (150 mg/d or 300 mg/d) or placebo once a day for the first three days then twice a day for the remaining treatment phase. Participants were seen for a pre-quit visit, on their quit date, then weekly for the 6 weeks of treatment and an additional in-person follow-up at week 7 and 26. Each of these visits assessed self-reported smoking status, adherence to regimen by counting remaining doses, safety, vital signs, height and weight.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this analysis is change in BMI z-score. BMI z-score was calculated using the WHO BMI-for-age reference standards(14) and is an important tool for considering under- and over- weight in children since BMI varies with age and sex for growing children(12). Weight and height were measured at baseline, weekly during the 6 weeks of treatment and at week 26. Those who were missing baseline weight measurement (n=4), baseline height (n=7) or both (n=5) were excluded from the analysis. If height was missing at week six but was recorded for at least one of the previous two weeks, we used the previous height value to calculate BMI. Seven-day point prevalence smoking abstinence was self-report. Percent adherence was calculated by dividing the number of doses taken by the total number of dose in the regimen.

Statistical methods

This was a post-hoc analysis to investigate BMI change in study subjects. We tested differences in baseline characteristics using a χ2 for categorical variables or ANOVA for continuous variables. We used a mixed methods repeated measures (MMRM) linear model with an unstructured covariance structure to test for longitudinal differences in BMI z-score across the three time points. This method controls for the within-person standard deviation of BMI z-score. Covariates included the visit week, treatment group, week-by-treatment group and the baseline BMI z-score. This modeling approach handles missing data by assuming that they are missing at random(15) and does not need complete cases. Statistical analyses used R software (16).

Results

A total of N=296 participants provided height and weight at baseline (placebo group n=100, 150mg/day group n=101, 300mg/day group n=95). Table 1 reports participant characteristics. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics of sex, age, BMI z-score, and adherence to study regimen. Twenty-four percent of the participants at week 6, and 53% of participants at week 26 were lost to follow-up or were missing height and weight measurements.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Placebo | 150 mg/day | 300 mg/day | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=100 | N=101 | N=105 | χ 2 | p-value | |

| Female | 43.0% | 52.5% | 43.2% | 2.36 | 0.31 |

| BMI z-score categories | |||||

| - Obese (≥2 sd) | 15.0% | 11.9% | 13.7% | 4.90 | 0.56 |

| - Overweight (≥1, < 2 sd) | 20.0% | 22.8% | 19.0% | ||

| - Normal (≥−2, < 1 sd) | 61.0% | 63.4% | 67.4% | ||

| - Thinness (≤−2 sd) | 4.0% | 2.0% | 0.0% | ||

| x̄ (σX) | x̄ (σX) | x̄ (σX) | |||

| Age | 16.3 (1.0) | 16.5 (0.9) | 16.5 (0.9) | ||

| Adherent to study protocol | 73.6% (27.6%) | 73.2% (28.1%) | 75.9% (24.6%) | ||

| Baseline BMI z-score | 0.5 (1.4) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.2) |

The MMRM model revealed a reduction in BMI z-score at week 6 for those in the 300mg group (Table 2). Those in the 300mg/day group had a BMI z-score that was 0.16 less than at baseline. BMI z-score change was not significant six months post cessation.

Table 2.

Mixed model repeated measures linear regression showing the relationship of BMI z-score change with treatment of bupropion

| β | (CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BMI z-score | 0.97 | (0.95, 0.98) | <0.01 |

| Placebo | - | ||

| 150mg bupropion | 0.00 | (−0.08, 0.08) | 0.99 |

| 300mg bupropion | 0.00 | (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.98 |

| At week 6 | 0.02 | (−0.06, 0.11) | 0.62 |

| At week 26 | −0.09 | (−0.19, 0.01) | 0.08 |

| 150mg × week 6 | −0.05 | (−0.17, 0.08) | 0.44 |

| 150mg × week 26 | 0.00 | (−0.15, 0.15) | 0.99 |

| 300mg × week 6 | −0.16 | (−0.29, −0.04) | 0.01 |

| 300mg × week 26 | 0.05 | (−0.10, 0.20) | 0.50 |

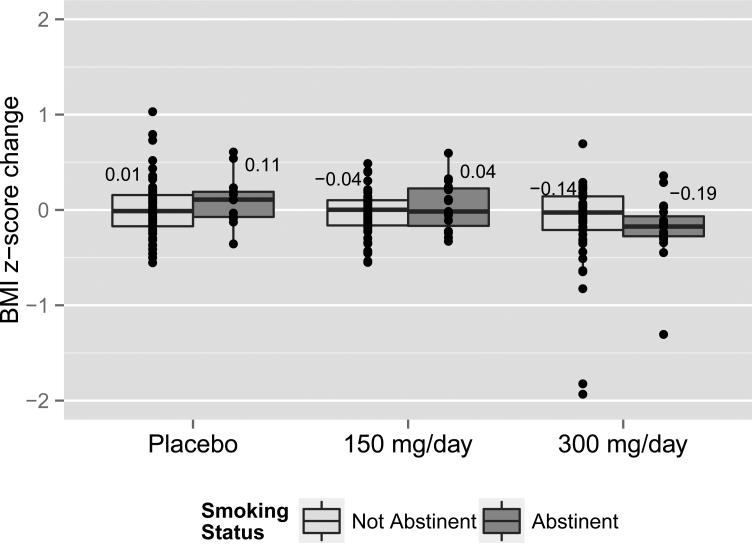

Figure 1 illustrates the mean change in BMI z-score from baseline to the end of the treatment period by groups and smoking status. Those in the placebo group and abstinent had a 0.11 (0.26) increase in their BMI s-score and those not abstinent had almost no change (0.01 (0.30)). Those in the 150 mg/day group and abstinent had an increase in BMI z-score of 0.04 (0.26) while those who were not abstinent had a −0.04 (0.24) change. In the 300mg/day group, those abstinent had a decrease in BMI z-score of −0.19 (0.34) and those not abstinent had a decrease of −0.14 (0.47).

Figure 1.

BMI z-score change by abstinence and treatment group at week 6 post quit

Discussion

This study is the first to look at weight changes in adolescents treated with bupropion SR for smoking cessation. We see in the MMRM model that those in the 300mg group had a reduction in BMI z-score regardless of abstinence status. This is not unexpected. Bupropion has a known, dose dependent, weight negative effect (17) Adult studies have shown that weight gain after cessation is mitigated with use of bupropion (8, 18). Bupropion SR is first-line therapy for adult smoking cessation(19). First-line medications for adult cessation have consistently demonstrated lower efficacy in adolescents (13, 20). Information about how these medications affect other deterrents to adolescent cessation other that nicotine withdrawal, e.g. weight gain, is valuable. In our study, adolescents who received 300mg/day had better quit rates than the placebo group at the end of treatment (13). There was not a significant different in BMI z-score change 26 weeks after the start of treatment. It is unclear from this study whether the BMI z-score reduction was not sustained or because the loss to follow-up rendered insignificance.

Unfortunately this study was not powered adequately to assess interaction with abstinence in the MMRM model. The data shown in Figure 1 suggests that there might be differences between those who quit tobacco and those who did not. However the conclusions based on these data alone and not modeled with an approach that account for the loss to follow-up could be misleading and are thus were not preformed. It should be noted that we show self-reported quit rates. The trial also used biochemical verification for abstinence (urinary cotinine and exhaled carbon monoxide levels); these methods showed lower abstinence rates (13).

There were 3 observations whose BMI z-score change was greater than 1 standard deviation in the 300 mg/day group. We examined the weekly weight of these three participants and found that it steadily decreased over the course of the treatment period, which indicates that these were true values and not a result of a data entry error. We also checked all height measurements for errors and found none. The negative BMI z-score change for these participants and others could be attributed to positive changes in lifestyle while making a quit attempt. The motivation to quit smoking might have been coupled with a motivation to also improve one's eating habits or engage in physical activity. Assessment of these factors was out of the scope of this study.

A post-hoc analysis has the advantage of hindsight, but the many strengths of the study design (randomized, double-blind, large sample-size, and height and weight assessment at each visit) would suggest that this advantage was minimized. A study limitation study was the use of self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence that may be less reliable than other biologically confirmed methods.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrated that BMI increases can potentially be mitigated in adolescents after smoking cessation with bupropion SR. These results are particularly relevant for adolescents who are either overweight or obese, or have reservations about quitting for fear of gaining weight or BMI. Longer-term studies with bupropion are warranted.

What is already known about this subject:

Overweight, obesity and tobacco use are risk factors that are related.

Overweight, obesity and tobacco use negatively affect the health of adolescents.

Smoking cessation causes BMI gain in both adults and adolescents, thus reducing the overall health benefits of cessation by increasing risk for serious health problems.

What this study adds:

This study demonstrates the potential for bupropion SR to mitigate adolescents’ BMI z-score gain during smoking cessation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grant RO1 CA77081.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2013. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC : 2002) 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. Epub 2014/06/12. PubMed PMID: 24918634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama. 2014;311(8):806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. Epub 2014/02/27. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. PubMed PMID: 24570244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2007;150(1):12–7. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. Epub 2006/12/26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. PubMed PMID: 17188605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR. Multiple health behavior change research: an introduction and overview. Preventive medicine. 2008;46(3):181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001. Epub 2008/03/06. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001. PubMed PMID: 18319098; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2288583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pronk NP, Anderson LH, Crain AL, Martinson BC, O'Connor PJ, Sherwood NE, et al. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors. Prevalence, clustering, and predictors among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;27(2 Suppl):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.022. Epub 2004/07/28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.022. PubMed PMID: 15275671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanza HI, Grella CE, Chung PJ. Does adolescent weight status predict problematic substance use patterns? American journal of health behavior. 2014;38(5):708–16. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.5.8. Epub 2014/06/17. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.38.5.8. PubMed PMID: 24933140; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4066210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harakeh Z, Engels RC, Monshouwer K, Hanssen PF. Adolescent's weight concerns and the onset of smoking. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(12):1847–60. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682149. Epub 2010/04/15. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682149. PubMed PMID: 20388007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farley AC, Hajek P, Lycett D, Aveyard P. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD006219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub3. Epub 2012/01/20. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub3. PubMed PMID: 22258966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavallo DA, Duhig AM, McKee S, Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender and weight concerns in adolescent smokers. Addictive behaviors. 2006;31(11):2140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JL, Eaton DK, Pederson LL, Lowry R. Associations of trying to lose weight, weight control behaviors, and current cigarette use among US high school students. Journal of School Health. 2009;79(8):355–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorner-Bantug E, Jaszyna-Gasior M, Schroeder JR, Collins CC, Moolchan ET. Weight gain, related concerns, and treatment outcomes among adolescent smokers enrolled in cessation treatment. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009;101(10):1009–14. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31067-1. Epub 2009/10/29. PubMed PMID: 19860300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? European journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;59(3):419–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602090. Epub 2005/01/28. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602090. PubMed PMID: 15674315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muramoto ML, Leischow SJ, Sherrill D, Matthews E, Strayer LJ. Randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(11):1068. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) Supplement. 2006;450:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. Epub 2006/07/05. PubMed PMID: 16817681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell ML, Fairclough DL. Practical and statistical issues in missing data for longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. Statistical methods in medical research. 2014;23(5):440–59. doi: 10.1177/0962280213476378. Epub 2013/02/22. doi: 10.1177/0962280213476378. PubMed PMID: 23427225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, Sonbol MB, Altayar O, Undavalli C, et al. Drugs Commonly Associated With Weight Change: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100(2):363–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3421. Epub 2015/01/16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3421. PubMed PMID: 25590213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hays JT, Hurt RD, Rigotti NA, Niaura R, Gonzales D, Durcan MJ, et al. Sustainedrelease bupropion for pharmacologic relapse prevention after smoking cessation. a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(6):423–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-6-200109180-00011. Epub 2001/09/19. PubMed PMID: 11560455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008;35(2):158–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. Epub 2008/07/12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. PubMed PMID: 18617085; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4465757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moolchan ET, Robinson ML, Ernst M, Cadet JL, Pickworth WB, Heishman SJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of the nicotine patch and gum for the treatment of adolescent tobacco addiction. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e407–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1894. Epub 2005/04/05. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1894. PubMed PMID: 15805342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]