Abstract

Fludarabine (F) and cyclophosphamide (C) remain backbones of up-front chemotherapy regimens for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). We report long-term follow-up of a randomized F versus FC trial in untreated, symptomatic CLL (NCT00003764, clinicaltrials.gov). With median follow-up of 88 months, estimated median progression-free survival (PFS) was 19.3 versus 48.1 months for F (N=109) and FC (N=118) respectively (p<0.0001), while median overall survival (OS) was 88.0 versus 79.1 months respectively (p=0.96). In multivariable analyses, variables associated with inferior PFS and OS respectively were older age (p=0.002, p<0.001), Rai stage ≥II (p=0.006, p=0.02) and sex (p=0.03, PFS only). Occurrence of del(17)(p13.1) predicted shorter PFS and OS (p<0.0001 for each), as did del(11q)(22.3) (p<0.0001 and p=0.005, respectively), trisomy 12 with mutated Notch1 (p=0.003 and p=0.03, respectively) and unmutated IGHV (p=0.009 and p=0.002, respectively), all relative to patients without these features. These data confirm results from shorter follow-up and further justify targeted therapies for CLL.

Keywords: fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, chemotherapy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia

INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by the progressive accumulation of malignant CD5+/CD19+ B-cells in the periphery, lymph nodes, spleen and bone marrow. The diversity of clinical outcomes in CLL is well established, but the factors that lead to this diversity are only partially understood. To better define CLL patient subsets that will require early treatment or will have a poor response with therapy, a number of prognostic factors have been identified that include IGHV gene mutational status and associated ZAP-70 expression [1–4], CD38 expression [1], interphase cytogenetic abnormalities [5], and the presence of non-silent p53 mutations [6], among others. Although efforts are underway to incorporate such molecular and biologic characteristics into the decision to initiate therapy as part of early intervention clinical trials, outside of clinical investigation, CLL is typically treated only upon the appearance of symptoms.

For many years, initial treatment for fit CLL patients who lack the del(17)(p13.1) abnormality have typically included fludarabine (F) with or without cyclophosphamide (C) [7–10]. These agents resulted in notable improvements in response and progression-free survival (PFS) over the previous standard chlorambucil, although in the four-year follow-up analysis, they did not improve overall survival (OS) [9]. The addition of CD20-directed monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab to up-front chemotherapy regimens introduced the potential to prolong survival of patients with CLL, with manageable toxicities [11,12]. Despite these improvements, CLL remains incurable and continues to present significant clinical challenges. Recently, advancements in CLL B-cell biology prompted the introduction of agents that inhibit the B-cell receptor pathway. Such drugs, exemplified by the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib [13–15] and the PI3 kinase inhibitor idelalisib [16,17], have produced impressive results in both previously treated and refractory CLL patients, with modest side effects. Other therapeutics not yet approved for marketing such as ABT-199 also have shown significant promise [18]. These data are extremely encouraging, and will likely represent the foundation of future combination strategies with biologic approaches such as monoclonal antibodies, antibody-like engineered molecules, and chimeric antigen receptor T-cells. However, at this time F and C remain central components of the standard, up-front CLL treatment regimen for non-del(17)(p13.1) and otherwise fit CLL patients [19].

We previously reported the results of a randomized Phase III clinical trial comparing F monotherapy with the FC combination in treatment-naive CLL [ECOG 2997/CALGB 10103/SWOG E2997 (E2997)] [20]. This clinical investigation showed that the addition of C provided superior complete response (CR) rates and longer PFS over F alone without impacting the rate of infections. OS was not observed to be prolonged with the addition of C, potentially due to the relatively short follow-up. We also conducted companion studies examining an array of baseline molecular and biologic factors and their impact on the achievement of CR as well as PFS; OS data were not previously reported in the context of genetic features [21]. In those studies, cytogenetic abnormalities del(17)(p13.1) and del(11)(q22.3) were associated with reduced PFS, but not CR. These findings were not different by treatment arm. Other potential predictive markers including IGHV gene mutation status and expression levels of CD38 and ZAP-70 did not provide additional prognostic information with respect to CR and PFS. Here, we provide long-term follow-up information on this uniformly-treated CLL population, including investigation of new markers that have arisen since the original analysis as well as re-investigation of several key molecular markers in this context.

METHODS

Patients and samples

Patients had previously untreated CLL requiring therapy according to NCI 1996 criteria [22] and provided written, informed consent under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol for treatment and research use of their samples. A total of 278 patients were randomized to receive F or FC in the intergroup Phase III clinical trial [20], and a subset of 235 patients participated in the correlative studies [21]. Material required to conduct additional molecular analyses for this study was available on 227 (97%) of the originally described 235 patients, and there were no significant differences in this subset relative to the entire study population [20,21]. The median age at time of enrollment was 61 (range 33–86) and 73% were male. Peripheral blood, obtained immediately prior to treatment, was shipped overnight to a central processing laboratory. Mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved using standard techniques.

Molecular characterizations

Methods for interphase cytogenetic analysis by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) [23], IGHV mutation analysis [24,25], and quantitative ZAP-70 methylation analysis at CpG+223 [4,26] have been described. For this study, gene mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were newly examined using temperature gradient capillary electrophoresis (Transgenomic, Omaha NE). All samples with abnormal peaks were sequenced by Sanger methodology. Results were compared with human genome reference sequences (BRAF: GRCh37/hg19 Feb. 2009; all others: NCBI36.3/hg18 Mar. 2006) using Lasergene Software (DNASTAR, Madison WI) and BLAT searches (genome.ucsc.edu). SNPs were distinguished using dbSNP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). Genes examined included p53 (complete coding region), Notch1, XPO1/CRM1, MDM2 (SNP309), BRAF and BTK.

Statistical analysis

Of the 278 patients enrolled on E2997, the 227 cases with available data were included in this study investigating the association of clinical characteristics and genetic markers with clinical outcomes. PFS was defined as the time from randomization until documented disease progression or death without progression, censoring patients alive and progression-free at the date of last reported contact. OS was defined as the time from randomization until date of death, censoring patients alive at last contact date. Associations between clinical and genetic features with PFS or OS were initially explored using Kaplan-Meier plots and differences evaluated with the log-rank test. Multivariable models were fit using Cox proportional hazards models and included a treatment effect. Other variables considered for inclusion were gender, age, Rai stage, white blood cell count, and a cytogenetic/molecular classification with five groups: del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation, unmutated IGHV, and all others. These genetic categories were defined as such by incorporating molecular information into the already developed cytogenetic hierarchical model of Dohner et al. [5] through standard modeling procedures. Specifically, patients who harbored multiple genetic abnormalities including del(17)(p13.1) were classified in the del(17)(p13.1) group (n = 17). Among remaining patients, those who harbored del(11)(q22.3) with or without other genetic abnormalities were classified in the del(11)(q22.3) group (n = 35). In patients without del(17)(p13.1) or del(11)(q22.3), patients with trisomy 12 would typically be classified next. However, modeling results showed that PFS, and to a lesser extent OS, were different between patients with trisomy 12 plus a Notch1 mutation and patients with trisomy 12 patients without a Notch1 mutation. This led to a separate classification group of patients with trisomy 12 plus mutated Notch1 (n = 19). In addition, modeling results showed that PFS and OS were similar among the remaining cytogenetic groups [del(6)(q23) (n = 8), trisomy 12 without Notch1 mutation (n = 30), normal interphase cytogenetics (n = 38), and del(13)(q14.3) (n = 74)], but that PFS and OS were different according to IGHV status in these patients. Hence, patients without del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), or trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation were grouped as either unmutated IGHV (n = 57) or other (n = 66). Patients with missing FISH data (n = 5), trisomy 12 but missing Notch1 data (n = 1), and lower-risk genetic abnormalities but missing IGHV data (n=27) were not included in the cytogenetic/molecular classification. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

Patients and treatment outcome

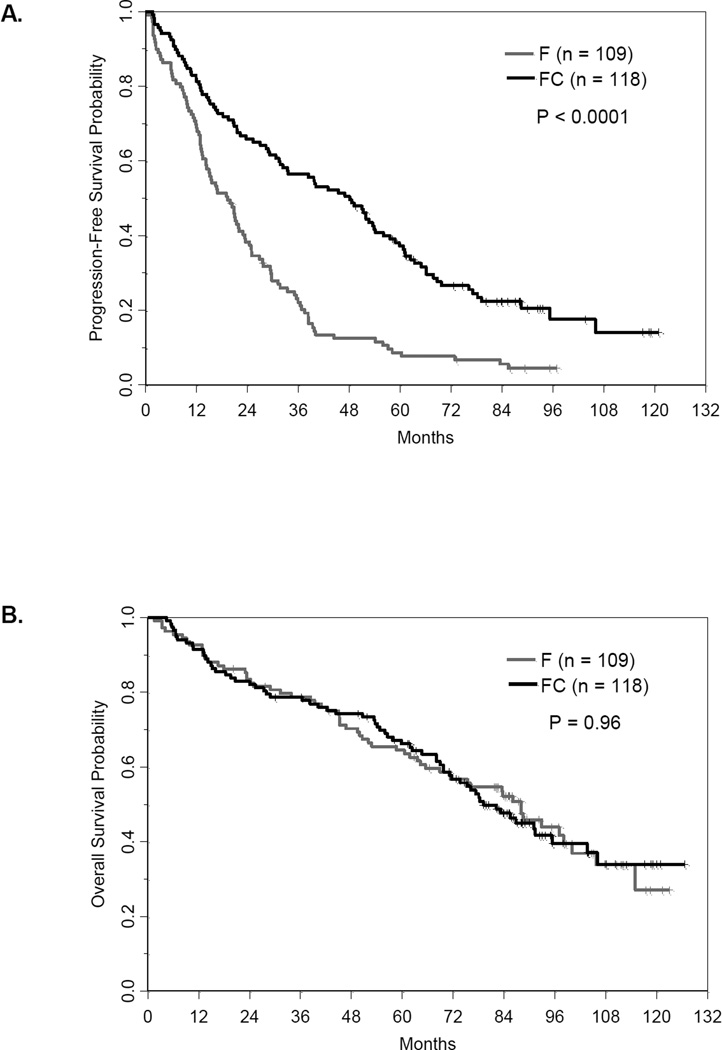

Here we report follow-up data from 227 patients (F=109, FC=118) with clinical and molecular data available (Table I). With median follow-up of 88 months, PFS was significantly longer with the combination versus F alone (median PFS 48.1 and 19.3 months, respectively; P<0.0001) (Figure 1A). However, even with this extended follow-up time, OS did not differ significantly between patients treated with FC versus F (median OS 79.1 versus 88.0 months, respectively; P=0.96) (Figure 1B). The finding that the addition of C to F treatment provides no OS benefit is in agreement with reports from similar studies with shorter follow-up [27,28].

Table I.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | N = 227 |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 61 (33 – 86) |

| Male, n (%) | 166 (73) |

| Rai Stage, n (%) | |

| 0/I | 61 (27) |

| II | 64 (28) |

| III/IV | 102 (45) |

| Median hemoglobin, g/dL (range) | 12.4 (4.7 – 16.3) |

| Median platelet count ×109/L (range) | 157 (32 – 425) |

| Median leukocyte count ×109/L (range) | 73.7 (7.4 – 542.7) |

| FISH abnormality prioritization, n (%) | |

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 (8) |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 (16) |

| +12 | 50 (23) |

| del(6)(q23) | 8 (4) |

| Normal | 38 (17) |

| del(13)(q14.3) | 74 (33) |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Notch1 mutation, n (%) | |

| Absent | 192 (87) |

| Present | 29 (13) |

| Unknown | 6 |

| IGHV status, n (%) | |

| Mutated | 85 (44) |

| Unmutated | 109 (56) |

| Unknown | 33 |

| ZAP-70 methylation, n (%) | |

| Methylated (≥20%) | 32 (24) |

| Unmethylated (<20%) | 103 (76) |

| Unknown | 92 |

| Cytogenetic/molecular prioritization, n (%) | |

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 (9) |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 (18) |

| +12 with Notch1 mutation | 19 (10) |

| Unmutated IGHV | 57 (29) |

| All others | 66 (34) |

| Unknown | 33 |

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves by treatment arm.

A) Progression-free survival; B) Overall survival.

Cytogenetic and molecular features

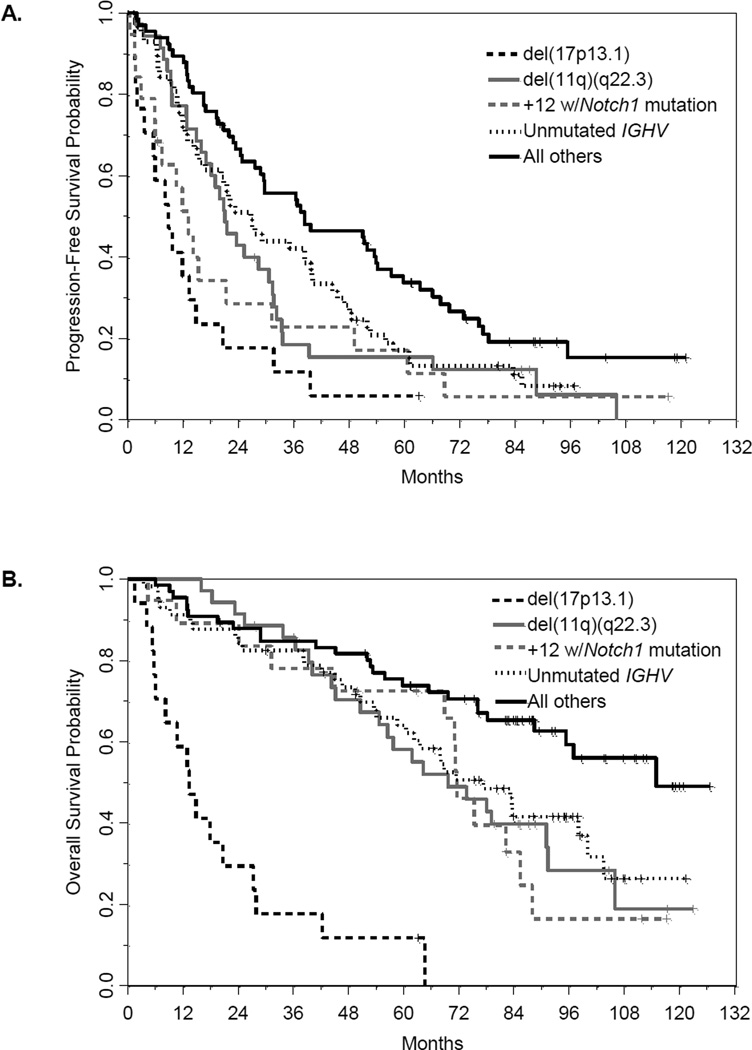

As in the first report of data from these patients [21], the Dohner hierarchical classification was initially used to prioritize patients with multiple cytogenetic aberrations by FISH. As expected, patients with del(17)(p13.1) had aggressive disease (n=17, 8%), where all but one progressed within 4 years of treatment and few appeared to be salvaged for any length of time, as demonstrated by the steep decline in OS (Tables II, III; Figure 2). A total of 35 patients (16%) were classified as del(11)(q22.3) and were previously shown to have short PFS. With extended follow-up, it is clear that these patients also have shorter OS with standard chemotherapy, although not nearly to the extent of those with del(17)(p13.1). Historically, the impact of trisomy 12 on clinical outcome has been unclear. However, in this dataset, we observed a significant association between patients classified as trisomy 12 and those harboring a Notch1 mutation (p<0.0001), a mutation that has been previously significantly associated with poorer outcome and is generally mutually exclusive with p53 mutations [29,30]. Among the 29 patients (13%) with a Notch1 mutation, 19 were classified as trisomy 12, and these patients tended to have shorter PFS and OS than the 30 patients classified as trisomy 12 without a Notch1 mutation (p=0.02 and p=0.10, respectively). Furthermore, all but two patients with trisomy 12 and Notch1 mutations have progressed, with clinical outcomes similar to those of patients harboring del(11)(q22.3). Among patients without del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), or trisomy 12 plus mutated Notch1 and with an IGHV result (n = 123), the presence of IGHV unmutated disease (n = 57) appeared to further delineate clinical outcome (PFS: p=0.03, OS: p=0.02). Other molecular features analyzed included mutations in p53, BRAF, XPO1/CRM1, and BTK, as well as the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position 309 of MDM2. However, the small numbers of patients with these features precluded assessment of impact on clinical outcome.

Table II.

Median Progression-Free Survival (PFS) by Genomic Features

| Feature | Total No. Pts |

PFS (months) |

No. Pts Receiving F |

PFS for Pts Receiving F |

No. Pts Receiving FC |

PFS for Pts Receiving FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytogenetics: | ||||||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 | 8.9 | 7 | 8.2 | 10 | 10.8 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 | 21.1 | 12 | 17.0 | 23 | 28.4 |

| +12 | 50 | 24.9 | 28 | 21.2 | 22 | 56.0 |

| del(6)(q23) | 8 | 47.8 | 1 | 26.8 | 7 | 48.5 |

| Normal | 38 | 37.9 | 22 | 14.3 | 16 | 61.8 |

| del(13)(q14.3) | 74 | 33.4 | 35 | 22.9 | 39 | 57.6 |

| Notch1 mutation: | ||||||

| No | 192 | 28.4 | 93 | 20.9 | 99 | 47.0 |

| Yes | 29 | 13.1 | 14 | 8.9 | 15 | 49.1 |

| IGHV status: | ||||||

| Mutated | 85 | 29.7 | 42 | 21.1 | 43 | 53.8 |

| Unmutated | 109 | 20.9 | 53 | 14.9 | 56 | 31.4 |

|

Cytogenetic/molecular group: |

||||||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 | 8.9 | 7 | 8.2 | 10 | 10.8 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 | 21.1 | 12 | 17.0 | 23 | 28.4 |

| +12 w/Notch1 mut. | 19 | 13.1 | 10 | 9.6 | 9 | 49.1 |

| Unmutated IGHV | 57 | 26.8 | 29 | 16.8 | 28 | 42.8 |

| Other | 66 | 38.3 | 34 | 23.5 | 32 | 67.8 |

Table III.

Median Overall Survival (OS) by Genomic Features

| Feature | Total No. Pts |

OS (months) |

No. Pts Receiving F |

OS for Pts Receiving F |

No. Pts Receiving FC |

OS for Pts Receiving FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytogenetics: | ||||||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 18 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 | 70 | 12 | NR | 23 | 70 |

| +12 | 50 | 88 | 28 | 88 | 22 | 85 |

| del(6)(q23) | 8 | 72 | 1 | 49 | 7 | 75 |

| Normal | 38 | 106 | 22 | 84 | 16 | NR |

| del(13)(q14.3) | 74 | 115 | 35 | 115 | 39 | NR |

| Notch1 mutation: | ||||||

| No | 192 | 88 | 93 | 88 | 99 | 83 |

| Yes | 29 | 71 | 14 | 71 | 15 | 72 |

| IGHV status: | ||||||

| Mutated | 85 | 91 | 42 | 97 | 43 | 91 |

| Unmutated | 109 | 71 | 53 | 71 | 56 | 69 |

|

Cytogenetic/molecular group: |

||||||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 17 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 18 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 35 | 70 | 12 | NR | 23 | 70 |

| +12 w/Notch1 mut. | 19 | 72 | 10 | 75 | 9 | 72 |

| Unmutated IGHV | 57 | 77 | 29 | 71 | 28 | 77 |

| Other | 66 | 115 | 34 | 115 | 32 | NR |

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves by cytogenetic/molecular classification.

A) Progression-free survival; B) Overall survival.

Models combining clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular predictors of outcome

Collectively, using patterns observed in our own data and in previous studies, an enhanced classification system incorporating both cytogenetic and molecular markers formed five groups: del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), trisomy 12 with Notch1 mutation, IGHV unmutated disease, and lastly, those without del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), trisomy 12 with Notch1 mutation, or IGHV unmutated disease. Multivariable models were fit using these categories and adjusting for treatment arm as well as other significant clinical characteristics. In the final model for PFS (Table IV), treatment with FC was significantly protective and was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.37 (p<0.0001). Other clinical variables associated with PFS were Rai stage (HR for stage ≥II = 1.66; p=0.006), sex (HR for females = 0.66; p=0.03) and age (HR for 10-year increase = 1.33; p=0.002). The cytogenetic/molecular classification group was an independent prognostic factor, where del(17)(p13.1) was associated with a HR of 4.55 (p<0.0001), del(11)(q22.3) with a HR of 2.54 (p<0.0001), trisomy 12 plus mutated Notch1 with an HR of 2.31 (p=0.003), and IGHV unmutated disease with a HR of 1.70 (p=0.009), all relative to patients without these high-risk genetics. In contrast, the model for OS (Table V) did not reveal a protective effect of FC versus F (HR=0.98; p=0.91). However, most other variables that impacted the modeling of PFS also impacted the modeling of OS, and included: Rai stage ≥II (HR=1.68; p=0.02); increased age (HR for 10-year increase = 1.54; p<0.001); del(17)(p13.1) (HR=15.17; p<0.0001); del(11)(q22.3) (HR=2.23; p=0.005); trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation (HR=2.10; p=0.03); and IGHV unmutated disease (HR=2.27; p=0.002). In both PFS and OS models, the effect of cytogenetic/molecular classification on outcome did not differ by treatment arm (p=0.21 and p=0.46, respectively). Together, these observations provide long-term validation of commonly applied prognostic markers in CLL, and highlight the need to identify new treatment strategies for patients with high-risk genetic and clinical features, particularly del(17)(p13.1).

Table IV.

Multivariable Model for Progression-Free Survival

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm: FC vs. F | 0.37 | 0.27–0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Age: 10 year increase | 1.33 | 1.11–1.59 | 0.002 |

| Sex: Female vs. Male | 0.66 | 0.46–0.95 | 0.03 |

| Rai stage: II/III/IV vs. 0/I | 1.66 | 1.16–2.37 | 0.006 |

| Cytogenetic/molecular group: | |||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 4.55 | 2.56–8.09 | <0.0001 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 2.54 | 1.60–4.03 | <0.0001 |

| +12 w/Notch1 mutation | 2.31 | 1.33–4.02 | 0.003 |

| Unmutated IGHV | 1.7 | 1.14–2.53 | 0.009 |

| Other (Reference) | --- | --- | --- |

Table V.

Multivariable Model for Overall Survival

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm: FC vs. F | 0.98 | 0.67–1.43 | 0.91 |

| Age: 10 year increase | 1.54 | 1.23–1.92 | <0.001 |

| Rai stage: II/III/IV vs. 0/I | 1.68 | 1.07–2.65 | 0.02 |

| Cytogenetic/molecular group: | |||

| del(17)(p13.1) | 15.17 | 7.64–30.11 | <0.0001 |

| del(11)(q22.3) | 2.23 | 1.27–3.93 | 0.005 |

| +12 w/Notch1 mutation | 2.1 | 1.08–4.10 | 0.03 |

| Unmutated IGHV | 2.27 | 1.35–3.83 | 0.002 |

| Other (Reference) | --- | --- | --- |

Prognostic significance of ZAP-70 CpG+223 methylation

ZAP-70 expression is a well-established prognostic indicator in CLL [31–33]. However, reproducible measurement of its protein or mRNA remains challenging in clinical laboratories. We [4,26] and others [34,35] have reported the prognostic value of DNA methylation in the regulatory region of ZAP-70. Therefore, ZAP-70 CpG+223 methylation was quantitatively assessed in a subset of 135 patients for whom material was available; clinical as well as biological characteristics of this subset were similar to the entire study population. Using the 20% cut point recently published [4], high ZAP-70 methylation (n=32) was associated with extended PFS across treatment arms (p=0.03), but not with OS (p=0.30). When incorporating ZAP-70 methylation in lieu of IGHV mutational status in the cytogenetic/molecular classification group, the model for PFS showed that low levels of ZAP-70 methylation in patients without the high-risk genetic abnormalities del(17)(p13.1), del(11)(q22.3), or trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation were associated with a HR of 1.97 (p=0.03) relative to patients without these high-risk genetic abnormalities and high ZAP-70 methylation. In the model for OS, low ZAP-70 methylation was associated with a HR of 2.14, although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08).

DISCUSSION

Here we provide updated analyses, using data mature for both PFS and OS, to evaluate the impact of cytogenetic and molecular markers in previously untreated patients with symptomatic CLL who received F monotherapy or FC combination therapy as part of an intergroup Phase III clinical trial. Samples from this study, obtained from 227 patients prior to treatment, were investigated for a variety of new molecular markers that have arisen in recent years as well as those with established relevance in CLL prognostication. Of these, cytogenetic evaluation by FISH provided the strongest prognostic information in a multivariable analysis. Incorporating Notch1 mutation status into the trisomy 12 classification further improved its prognostic value [36], an example of the additional benefits provided by integrating molecular information to refine subsets and inform biological investigations [37]. Although IGHV unmutated disease has long been associated with inferior outcome in CLL [2], it was not significantly associated with PFS in the original analysis of this dataset. However by identifying high-risk patients with del(17)(p13.1)/ del(11)(q22.3)/ trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation, and comparing patients with IGHV unmutated versus mutated disease among the remaining patients, IGHV status did impact both PFS (p=0.009) and OS (p=0.002). The genetic characterizations performed here further support previous work and again indicate the necessity of improved therapies particularly for the del(17)(p13.1) patient subset, but for other subsets as well. Since the addition of monoclonal antibodies to CLL chemotherapy regimens has now been shown to improve OS [11,12] and B-cell receptor targeted agents appear poised to do the same [38], better characterization of genetic subgroups from a historical study with extended follow-up provides valuable information with which results from these new agents can be compared.

Clinical outcomes according to treatment arm in this subset of patients are in close agreement with earlier reports both from this trial [20] and from similar trials [27,28], in that the FC combination significantly extended PFS relative to F alone (p<0.0001), but provided no OS advantage even after extended observation (p=0.96). The addition of C has been also reported to increase the incidence of hematologic toxicities [20,27,28] and may increase the risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasia (in E2997, 4.6% and 8.2% at 7 years for F and FC respectively; P=0.09) [39]. However, the general consensus has been that FC is superior to F for patients able to tolerate such treatments.

The failure of chemotherapy regimens (F-based and others) to prolong OS of CLL patients is recognized, although the data showing this have largely been obtained from studies with shorter follow-up. In addition to the F vs. FC studies mentioned [20,27,28], a Phase III trial in older (>65 years) previously untreated CLL patients found no difference in OS between F monotherapy and chlorambucil [40], and bendamustine failed to prolong OS relative to chlorambucil [41]. An earlier Phase III trial of previously untreated CLL patients also showed no difference in OS between F monotherapy and chlorambucil [9]. Interestingly, however, in that study a modest long-term survival advantage with F began to emerge with extended follow-up (31% of F-treated vs. 19% of chlorambucil-treated patients were alive at 8 years; covariate-adjusted P=0.07) [42]. In our current report, there were 193 events in 227 patients (85%) for PFS, whereas in the earlier report of E2997 in 2007, there were only 129 events in 278 patients (46%) [20]. While early estimates for PFS curves are similar, we now have much longer follow-up and better estimates for the later time points that were not previously available. In this update, the median PFS for the FC group is 48.1 months versus 19.3 months for the F group, while in 2007 the median PFS estimates for the FC and F groups were 31.6 months and 19.2 months, respectively. The longer median PFS in the current study may possibly be due to a skew in early censoring in the original analysis. In terms of OS, there are now 125 events in 227 patients (55%), whereas there were only 55 events in 278 patients (20%) at the time of the 2007 publication. No curves were previously shown for OS, but the 2-year estimates reported were 79% for the FC group and 80% for the F group. In the current study, 2-year estimates are 83% for each group, very similar our previous report. In addition, we provide long-term survival estimates with little censoring prior to 6 years. These observations together support the value of long-term follow-up, at least in clinical studies where such analysis is feasible.

Regardless, our data confirm the lack of a significant survival advantage with chemotherapy regimens for most patients, and the strong need to incorporate non-chemotherapy agents (i.e. monoclonal antibodies, targeted agents) into CLL treatment to extend OS. This effort is clearly gaining substantial ground with the B-cell receptor targeted agents idelalisib [16] and ibrutinib [13] (reviewed by Cheson [38]), and the advent of chimeric antigen receptor-engineered cellular therapy offers the impressive potential to activate the immune system for long-term disease control and perhaps even eradication [43].

Our data also confirm and extend the observation that there is substantial heterogeneity in CLL patient outcomes with F-based chemotherapy regimens. These therapies are insufficient for patients with del(17)(p13.1), who progress quickly and do not achieve long-term survival; in addition, patients with del(11)(q22.3), trisomy 12 plus Notch1 mutation, and/or unmutated IGHV also have reduced PFS and OS relative to patients without these high-risk genetic factors. Although such chemotherapy regimens are likely to continue to be used worldwide for some time, our results underscore the importance of moving CLL treatment away from chemotherapy toward safer, targeted agents to have the greatest impact on patient outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patients and the physicians who participated in E2997 and contributed samples, and the cooperative groups (ECOG, SWOG and CALGB, now Alliance) that joined in this effort. The correlative studies described here were supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 CA088647 and P50 CA140158). The E2997 clinical study was coordinated by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (Robert L. Comis and Mitchell D. Schnall, Co-Chairs) and supported in part by NIH grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA180820, CA180794, CA16116, CA180802, CA180791, CA14958, CA11083, CA13650, CA180790, CA35431, CA31946, CA32102, CA20319, and CA17145. RC receives a fellowship from the German Research Society (DFG) and is supported by the German Cancer Aid (Max Eder stipend, DKH 110461). CP is supported by the NIH (P01 CA101956), the German Cancer Research Center, and the German Cancer Consortium. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT: No authors have conflicts of interest with this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

DML oversaw correlative sample collection, performed molecular characterizations and wrote the paper; ASR conducted statistical analyses and interpretation and wrote the paper; GL conducted molecular analyses and wrote the paper; GWD performed cytogenetics; AL, RC, CP, DFJ and JGG performed and/or directed molecular characterizations; IWF led the E2997 clinical trial and contributed patients/samples; DSN performed E2997 statistical analyses; EMP and JMB received patient samples and performed biological characterizations; MAH contributed patients/samples and represents SWOG; FRA contributed patients/samples and represents SWOG; RAL contributed patients/samples and represents Alliance; DFM contributed patients/samples and represents Mayo Clinic; MST contributed patients/samples and represents ECOG; JCB designed the studies and is the Principal Investigator (PI) of P50 CA140158 that supported some of the molecular characterizations; MRG designed the studies, wrote the paper, oversaw the project, and was the PI of R01 CA88647 that funded this work. All authors approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Principe MI, Del Poeta G, Buccisano F, et al. Clinical significance of ZAP-70 protein expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:853–861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claus R, Lucas DM, Ruppert AS, et al. Validation of ZAP-70 methylation and its relative significance in predicting outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:42–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-555722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordone I, Masi S, Mauro FR, et al. p53 expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a marker of disease progression and poor prognosis. Blood. 1998;91:4342–4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grever MR, Kopecky KJ, Coltman CA, et al. Fludarabine monophosphate: a potentially useful agent in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1988;30:457–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson S, Smith AG, Loffler H, et al. Multicentre prospective randomised trial of fludarabine versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CAP) for treatment of advanced-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The French Cooperative Group on CLL. Lancet. 1996;347:1432–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, et al. Fludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1750–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leporrier M, Chevret S, Cazin B, et al. Randomized comparison of fludarabine, CAP, ChOP in 938 previously untreated stage B and C chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Blood. 2001;98:2319–2325. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine and rituximab produces extended overall survival and progression-free survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term follow-up of CALGB study 9712. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1349–1355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:48–58. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O'Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown JR, Byrd JC, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110delta, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:3390–3397. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-535047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:997–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013;19:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2013 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:803–816. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flinn IW, Neuberg DS, Grever MR, et al. Phase III trial of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide compared with fludarabine for patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: US Intergroup Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:793–798. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of genetic and molecular features predicting outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the US Intergroup Phase III Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:799–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewald GW, Brockman SR, Paternoster SF, et al. Chromosome anomalies detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization: correlation with significant biological features of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jelinek DF, Tschumper RC, Geyer SM, et al. Analysis of clonal B-cell CD38 and immunoglobulin variable region sequence status in relation to clinical outcome for B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:854–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauerer K, Zahrieh D, Gorgun G, et al. Immunoglobulin gene segment usage, location and immunogenicity in mutated and unmutated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claus R, Lucas DM, Stilgenbauer S, et al. Quantitative DNA methylation analysis identifies a single CpG dinucleotide important for ZAP-70 expression and predictive of prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2483–2491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, et al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Hopfinger G, et al. Fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide versus fludarabine alone in first-line therapy of younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:885–891. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi D, Rasi S, Fabbri G, et al. Mutations of NOTCH1 are an independent predictor of survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;119:521–529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villamor N, Conde L, Martinez-Trillos A, et al. NOTCH1 mutations identify a genetic subgroup of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with high risk of transformation and poor outcome. Leukemia. 2013;27:1100–1106. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiestner A, Rosenwald A, Barry TS, et al. ZAP-70 expression identifies a chronic lymphocytic leukemia subtype with unmutated immunoglobulin genes, inferior clinical outcome, and distinct gene expression profile. Blood. 2003;101:4944–4951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crespo M, Bosch F, Villamor N, et al. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1764–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rassenti LZ, Huynh L, Toy TL, et al. ZAP-70 compared with immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene mutation status as a predictor of disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:893–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corcoran M, Parker A, Orchard J, et al. ZAP-70 methylation status is associated with ZAP-70 expression status in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2005;90:1078–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chantepie SP, Vaur D, Grunau C, et al. ZAP-70 intron1 DNA methylation status: determination by pyrosequencing in B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2010;34:800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Giudice I, Rossi D, Chiaretti S, et al. NOTCH1 mutations in +12 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) confer an unfavorable prognosis, induce a distinctive transcriptional profiling and refine the intermediate prognosis of +12 CLL. Haematologica. 2012;97:437–441. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.060129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riches JC, O'Donovan CJ, Kingdon SJ, et al. Trisomy 12 chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells exhibit upregulation of integrin signaling that is modulated by NOTCH1 mutations. Blood. 2014;123:4101–4110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheson BD. CLL and NHL: the end of chemotherapy? Blood. 2014;123:3368–3370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-563890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith MR, Neuberg D, Flinn IW, et al. Incidence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasia after initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with fludarabine-cyclophosphamide versus fludarabine: long-term follow-up of US Intergroup Study E2997. Blood. 2011;118:3525–3527. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-342485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3382–3391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knauf WU, Lissitchkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: updated results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:67–77. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, et al. Long-Term Survival Analysis of the North American Intergroup Study C9011 Comparing Fludarabine and Chlorambucil in Previously Untreated Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:536a. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]