Abstract

Objective:

To investigate whether traditional Chinese herbal formula Yupingfeng (YPF) powder has an anti-inflammatory effect on colonic inflammation, and to explore the mechanism involved.

Materials and Methods:

YPF powder was orally administrated to trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis mice at the dose of 3, 6, and 12 g/kg/d for 7 consecutive days. Body weight, stool consistency, histopathological score, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity were tested to evaluate the effect of YPF powder on colonic inflammation while colonic enterochromaffin (EC) cell density and serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) content were investigated to identify the effect of YPF powder on colonic 5-HT availability.

Results:

The results showed that the body weight of colitis mice was markedly decreased by 10, 12, 14, and 17% at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days (P < 0.05), whereas stool consistency score (3.6 vs. 0.4, P < 0.05), histopathological score (3.6 vs. 0.3, P < 0.05), and MPO activity (2.7 vs. 0.1, P < 0.05) in colitis mice were significantly increased compared to that of the normal mice; YPF powder treatment dose-dependently increased the body weight (7–13% increase) and decreased the stool consistency score (0.4–1.4 decrease), histopathological score (0.2–0.7 decrease), and MPO activity (0.1–0.9 decrease) in colitis mice. Colonic EC cell density (70% increase) and 5-HT content (40% increase) were markedly increased in colitis mice (P < 0.05), YPF powder treatment dose-dependently reduced EC cell density (20–50% decrease), and 5-HT content (5–27% decrease) in colitis mice.

Conclusion:

The findings demonstrate that the anti-inflammatory effect of YPF powder on TNBS - induced colitis may be mediated via reducing EC cell hyperplasia and 5-HT content. The important role of YPF powder in regulating colonic EC cell number and 5-HT content may provide an alternative therapy for colonic inflammation.

KEY WORDS: Colonic inflammation, enterochromaffin cell, serotonin, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC), a chronic intestinal inflammatory disease, is characterized by severe diarrhea, pain, fatigue, and weight loss.[1] Based on the statistical analysis data, the incidence of UC has been increasing throughout the world, especially in the developing countries, this increasing trend in UC epidemiology may increase the healthcare burden and hinder economic development.[2] Although the causes of colonic inflammation have not been clearly identified, it is believed to have a correlation with genetic susceptibility, immune imbalance, and alterations in commensal microbiota.[3] Increased intestinal immune cells, such as T-cells, macrophages, enterochromaffin (EC) cells, as well as the altered cytokines, and chemokines are associated with immune imbalance of gut and has been considered as the therapeutic targets for the treatment of colonic inflammation.[4]

It is well known that nearly 95% of the body's serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) comes from the gut, with large amount stored in EC cells. As a neurotransmitter and intercellular signaling molecule, 5-HT activates both intrinsic and extrinsic primary afferent neurons, therefore, regulates the gastrointestinal activity. Increased intestinal EC cell number and 5-HT bioavailability have long been reported to play an important role in intestinal symptoms generation, such as visceral pain, motility dysfunction, and the altered barrier permeability.[5] Recently, several studies have shown that 5-HT may contribute to the initiation of intestinal inflammation.[6] It is reported that increase of 5-HT content in intestinal tissue by knocking out 5-HT reuptake transporter can exaggerate the severity of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis and spontaneous colitis that arises from interleukin-10 deletion[7,8] while decrease in the production of mucosal 5-HT by selectively inhibiting or knocking out the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for 5-HT synthesis can markedly attenuate experimental colitis in mice.[9,10] Given the important role of 5-HT in intestinal inflammation, it is proposed that strategies that aim at decreasing intestinal 5-HT bioavailability may provide an alternative therapeutic target to ameliorate symptoms of colonic inflammation.[11]

Until now, no guaranteed curative therapeutic regimen has been developed for colonic inflammation. The currently used management, such as corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as immune-modulators, primarily focus on promoting remission and preventing relapse.[12,13] In view of the side effects of conventional therapeutic medicines, more and more colitis sufferers seek the help of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Nowadays, TCM is not only used by colitis patients across Asia, but also by various proportions of Western patients with colitis, ranging from 23% to 49%.[14,15] Yupingfeng (YPF) powder is a traditional Chinese herbal formula, which was first recorded in Dan-Xi-Xin-Fa (Dan Brook Heart Law) and has been widely prescribed to treat spontaneous sweating, allergic rhinitis, as well as respiratory infection in China, Japan, and Korea. YPF powder consists of three Chinese herbals, i.e., Radix Astragali (Huang-Qi), Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae (Bai-Zhu), and Radix Saposhnikoviae (Fang-Feng). According to the theory of Chinese medicine, YPF powder can invigorate Qi and consolidate the body's defensive ability, which has been considered as an anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory agent.[16,17] Recently, results from one clinical study showed that YPF powder had a therapeutic effect in children with persistent diarrhea,[18] the underlying mechanism may have a correlation with its immunomodulatory function.[19]

In this study, we hypothesized that YPF powder can attenuate colonic inflammation in experimental UC induced by intracolonic TNBS instillation. While colonic EC cell density and 5-HT content were also investigated in order to identify whether the therapeutic effect of YPF powder on colonic inflammation have a correlation with its effect on regulating colonic 5-HT availability.

Materials and Methods

Materials

TNBS, hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, o-dianisidine dihydrochloride, and pentobarbital sodium were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). YPF powder was purchased from Yunnan Baiyao Group Co, Ltd., (Kunming, Yunnan, China). Methanol was of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade (Fisher Scientific, NJ, USA). All other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and were commercially available.

Animals

Male Balb/c mice (aged 8 weeks with a body weight around 22 g) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Lanzhou University. All the mice were maintained at 25°C under 12 h-12 h alternating light-dark cycle with free access to food and water. Studies were carried out in accordance with the proposals of the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Gansu College of TCM (Approval ID: 2014–031).

Development of Colitis Model

Mice were fasted overnight and then anesthetized by pentobarbital sodium intraperitoneal administration (50 mg/kg). A plastic catheter was inserted into the colon at a depth of 4 cm from the anus. TNBS solution (2.5 mg in 50% ethanol, 100 μl) was instilled slowly into the colon, after that the catheter was gently removed. The mice in the control group were given with 100 μl saline instead of TNBS solution.[20] All the mice were left on a warm pad until they recovered from anesthesia. At 1 and 3 days post TNBS administration, body weight and stool consistency were evaluated and recorded, the mice that showed soft or diarrhea stool with body weight decrease were selected as the colitis mice.

Study Design

The colitis mice were randomly divided into five groups. Group 1 (n = 10) was set as the colitis model group, mice in this group were orally treated with water. Mice in group 2, 3, and 4 (n = 10 per group) were orally treated with YPF powder at the dose of 3, 6, and 12 g/kg, respectively, the dosage was selected based on the previous study.[21] Group 5 (n = 10) was set as the positive control, mice in this group were orally treated with sulfasalazine (SASP) at the dose of 500 mg/kg.[22] Group 6 (n = 10) was set as a normal control, mice in this group were orally treated with water. The body weight change and stool consistency (0: Normal; 2: Soft; 4: Diarrhea) was scored according to previous methods at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days after drugs administration.[23] All the drugs were administered for consecutive 7 days and after the final drugs administration, the mice were sacrificed. A 3 cm long proximal colon was collected and divided into 2 parts, one part was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for EC cell counting, and the other part was frozen at −20°C for 5-HT content determination. A 3 cm long distal colon was collected and divided into 2 parts; the proximal was fixed in formalin for inflammation evaluation; the distal part was frozen at −20°C for myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity determination.

Histopathological Evaluation

The colon sections (5 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All sections were observed by a pathologist blinded to the group setting. The severity of colonic inflammation was recorded according to previous macroscopic and histological scoring criteria.[24] Five random fields were selected in each slide; all the scoring data were analyzed using ImageJ NIH software.

Myeloperoxidase Activity Determination

MPO activity was determined by the modified method described as full. Briefly, the colon tissues were homogenized in 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide 0.5 mL/50 mg of colon tissue; then the homogenates were centrifuged at 18,000 gat 4°C for 15 min. Aliquots of 40 mL supernatant were mixed with 60 μL potassium phosphate buffer (50 mmol, pH 6.0) with o-dianisidine dihydrochloride and hydrogen peroxide. MPO activity was obtained from the rate of absorbance alteration in 1 min at 460 nm.

Immunohistochemistry and Enterochromaffin Cell Counting

Tissue sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated for immunostaining. Antiserotonin primary antibody (1:4000, Sigma) was incubated at 4°C overnight. After that, sections were labeled streptavidin biotin (LSAB + system-HRP kit; Dako). The primary antibody was omitted as a negative control. Five fields at ×20 magnifications were captured for each section by a pathologist blinded to the group setting. The areas of colonic mucosa were measured using ImageJ NIH software, and EC cell density was expressed as the number of EC cells per mm2 of the mucosal area.

5-hydroxytryptamine Content Determination

5-HT content of colon tissue was performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC coupled to an Agilent 6460 Tripe-Quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with the electrospray ionization interface.[25] Briefly, colon tissue was homogenized in 15% iced trichloroacetic acid, then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant 20 μL were added to acetonitrile (containing 1 μg/mL methimazole) 20 μL, and the mixtures were vortexed for 5 min. For derivatization, borate buffer (sodium tetraborate, 100 mM in water) and benzoyl chloride (2% in acetonitrile, v/v) were added to the mixtures and vortexed under room temperature for 5 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 8 min, a 20 μL aliquot was transferred to the vial, and 5 μL was injected for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies, USA) analysis. The results were expressed as nanogram per milligram (wet weight of the tissue).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as a mean ± standard error. Differences between two groups were analyzed by Student's t-test. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Effects of Yupingfeng Powder on Body Weight and Stool Consistency in Colitis Mice

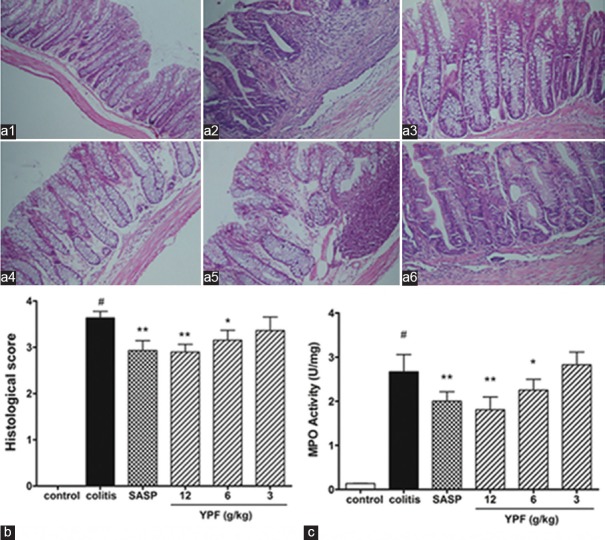

As shown in Figure 1a, the body weight in colitis mice was decreased about 10, 12, 14, and 17% at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days, respectively, when compared to that of the control, and SASP treatment markedly elevated the body weight in colitis mice after 5 and 7 days’ drug administration (P < 0.01). After YPF powder administration, the body weight in high (12 g/kg) and median (6 g/kg) dose treated mice were significantly elevated after 3, 5, and 7 days’ drug treatment when compared to that of the colitis mice (P < 0.05). Consistent with the findings from body weight change, the results from stool consistency score [Figure 1b] also found that colitis mice showed elevated score when compared to that of the control, SASP treatment, as well as YPF powder treatment at high and median dose markedly decreased the stool consistency score when drugs were administered for 5 and 7 days (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of Yupingfeng powder on body weight and stool consistency in trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis. (a) Statistical analysis of the body weight change, (b) the statistical analysis of stool consistency. Data are presented as a mean ± standard error of mean, n = 10 per group. §P < 0.05 versus normal mice, *P < 0.05 versus trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis mice

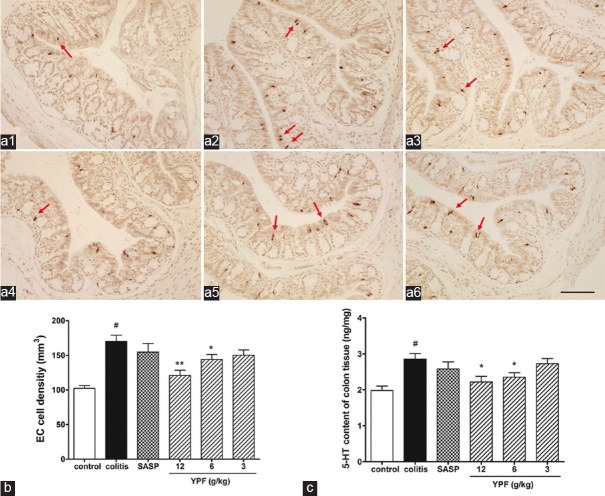

Effects of Yupingfeng Powder on Inflammation Severity in Colitis Mice

As shown in Figure 2, the results from histopathological evaluation [Figure 2a and b] and MPO activity assay [Figure 2c] showed that TNBS colonic administration induced acute inflammation in the colon tissue of mice with markedly increased histological score and MPO activity (P < 0.01), whereas SASP treatment significantly decreased both histological score and MPO activity when compared to that of the colitis mice (P < 0.01), suggesting that SASP had anti-inflammatory effect on TNBS-induced colitis. YPF powder treatment dose-dependently decreased histological score and MPO activity in colitis mice. There were significantly difference (P < 0.05) in both high (12 g/kg) and median (6 g/kg) dose of YPF powder-treated mice when compared to that of colitis mice, indicating that YPF powder can reduce the severity of colonic inflammation in TNBS-induced colitis.

Figure 2.

Effects of Yupingfeng powder on colonic inflammation in trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis. (a) The representative histological changes of distal colon tissue from (a1) normal mice; (a2) trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis mice; (a3) sulfasalazine-treated mice; and (a4) high dose; (a5) median dose; (a6) low dose Yupingfeng powder-treated mice (H and E, scale bar, 200 µm). Statistical analysis of the pathological score and myeloperoxidase activity (b and c, respectively). Data are presented as a mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 10 per group. #P < 0.01 versus normal mice, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis mice

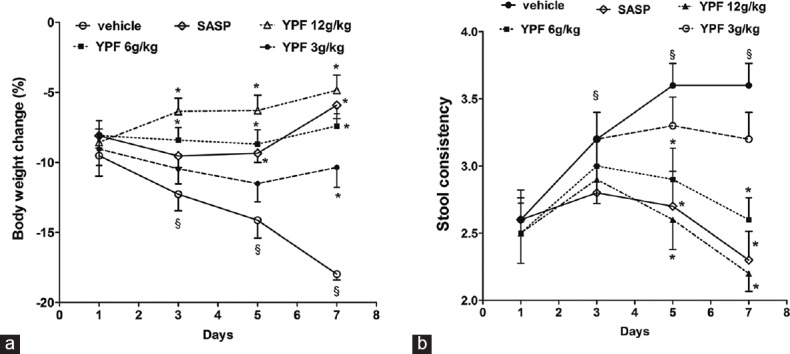

Effects of Yupingfeng Powder on Colonic Enterochromaffin Cell Density and 5-hydroxytryptamine Content in Colitis Mice

As shown in Figure 3, the colonic EC cell density [Figure 3a and b] and 5-HT content [Figure 3c] were both significantly increased in colitis mice (about 70% increase in EC cell density, about 40% increase in 5-HT content) when compared to that of the control (P < 0.05), suggesting the occurrence of EC cell hyperplasia in the colon of colitis mice. Compared with the colitis mice, SASP treatment slightly decreased the EC cell density and 5-HT content, but no significant difference was found between SASP treated mice and colitis mice. YPF powder treatment dose-dependently decreased the colonic EC cell density (20–50%) and 5-HT content (5–27%) in colitis mice, but only the mice that treated with high (12 g/kg) and median (6 g/kg) dose of YPF powder showed significant difference when compared to that of the colitis mice, suggesting that YPF powder can reduce colonic EC cells hyperplasia and 5-HT content in colitis mice.

Figure 3.

Effects of Yupingfeng powder on colonic enterochromaffin cell density and 5-hydroxytryptamine content in trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis. (a) The representative enterochromaffin cells (arrowhead) in colonic mucosa of the (a1) normal mice; (a2) trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis mice; (a3) sulfasalazine-treated mice; and (a4) high dose; (a5) median dose; (a6) low dose Yupingfeng powder-treated mice (DAB, scale bar, 200 µm). Statistical graph of enterochromaffin cell density (b), and 5-hydroxytryptamine content (c). Data are presented as a mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 10 per group. #P < 0.01 versus normal mice, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus trinitrobenzene sulfonic-induced colitis mice

Discussion

YPF powder has been widely prescribed in China to treat spontaneous sweating and respiratory infection. As an anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory agent, YPF powder is recently found to have a therapeutic effect on chronic colitis in patients,[18] but the underlying mechanism has not been clarified. This study investigated the anti-inflammatory effect of YPF powder on colonic inflammation using the TNBS-induced, colitis model. Our study provides the first evidence that YPF powder can effectively attenuate colonic histological score and MPO activity via reducing colonic EC cell density and 5-HT content in colitis mice. The findings from this study confirmed that YPF powder can be used as an alternative herbal agent in attenuating intestinal inflammation.

Considering the large amount of body's 5-HT located in the gastrointestinal tract, the role of 5-HT in regulating gastrointestinal activity has been investigated widely. Nowadays, it is found that increased colonic 5-HT bioavailability play a vital role in gastrointestinal symptoms generation, i.e., visceral pain, motility dysfunction, increased barrier permeability, and the initiation of intestinal inflammation.[5,6] Evidence also showed that EC cell number and 5-HT content are elevated in inflamed intestinal mucosa from Crohn's disease patients and in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease.[26] The discovery of the important role of 5-HT in intestinal inflammation has attracted more attention about intestinal 5-HT bioavailability. We all known that intestinal 5-HT is mainly stored EC cells, so the number and function of EC cells are considered to play a critical role in intestinal inflammation. Results from this present study showed that YPF powder can dose-dependently attenuate colonic inflammation, suggesting YPF powder has a potential therapeutic effect on colitis. Our results also found that YPF powder can markedly and dose-dependently reduce colonic EC cell density and 5-HT content in colitis mice, indicating that the reduced EC cell number and intestinal 5-HT level in YPF powder-treated mice may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effect of YPF powder in colitis mice.

It is not very clear how does 5-HT signaling modulate the process of intestinal inflammation. 5-HT is well known for its immune-modulatory effect, for there are many 5-HT receptors expressed on lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. It is possible that the elevated 5-HT level may modulate overly active immune response or dysfunctional inflammatory process,[27] which may partially explain the role of 5-HT in driving intestinal inflammation. Moreover, 5-HT is also known as a neurotransmitter, which activates intrinsic and extrinsic primary afferent neurons, and thus regulates the gastrointestinal function, such as sensitivity, motility, permeability, and secretion.[5] It is possible that the increased intestinal 5-HT level during inflammation may also contribute to the symptoms exaggeration in colitis, such as visceral pain, diarrhea, and even urgency.

YPF powder is a classical Chinese herbal formula commonly used to treat respiratory tract diseases.[16] This study found that YPF powder had anti-colitis activity in TNBS-induced colitis mice, this finding was consistent well with previous results which showed that YPF powder could shorten the duration of disease and reduce diarrheal recurrence rate, and the underlying mechanism may have correlation with its immunomodulatory function.[19] YPF powder has been commonly considered as an anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory agent, it has been found to promote proliferation of spleen cells and balance the ratio of helper (Th) 1/Th2 cells in allergic airway disease model in mice.[28] Knowing that there are numerous components in Chinese herbal formula, even though the bioactive components that responsible for the anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory effects of YPF powder have not been identified, the pharmacological effects of many components of YPF powder have been reported previously. For example, flavonoids of Huang-Qi show antioxidant and antiviral activity, total saponin in Huang-Qi promotes antibody production and immune responses while chromone glycosides in Fang-Feng, as well as atractylenolide I and III in Bai-Zhu are considered as an anti-inflammatory components.[29] To further explore the bioactive components and the mechanism of YPF powder on colonic inflammation, as well as intestinal 5-HT bioavailability, more studies are still needed in the future.

Conclusions

This study reveals that Chinese herbal formula YPF powder can dose-dependently attenuate colonic inflammation in the mice model of colitis, and the underlying mechanism may be mediated via reducing colonic EC cell density and 5-HT content. These data support YPF powder as a potential therapeutic formula for the treatment of colitis.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

This work was supported by the foundation of Key laboratory for gastrointestinal diseases of Gansu province in China (No. gswcky-2013-001).

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the foundation from the Key laboratory for gastrointestinal diseases of Gansu province in China (No. gswcky-2013-001).

References

- 1.Bardazzi F, Odorici G, Virdi A, Antonucci VA, Tengattini V, Patrizi A, et al. Autoantibodies in psoriatic patients treated with anti-TNF-a therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:401–6. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:91–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu XR, Liu CQ, Feng BS, Liu ZJ. Dysregulation of mucosal immune response in pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3255–64. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danese S. New therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: From the bench to the bedside. Gut. 2012;61:918–32. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiller R. Serotonin and GI clinical disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin AD, van den Brink GR. Selective inhibition of mucosal serotonin as treatment for IBD? Gut. 2014;63:866–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haub S, Ritze Y, Bergheim I, Pabst O, Gershon MD, Bischoff SC. Enhancement of intestinal inflammation in mice lacking interleukin 10 by deletion of the serotonin reuptake transporter. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:826–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischoff SC, Mailer R, Pabst O, Weier G, Sedlik W, Li Z, et al. Role of serotonin in intestinal inflammation: Knockout of serotonin reuptake transporter exacerbates 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G685–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90685.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghia JE, Li N, Wang H, Collins M, Deng Y, El-Sharkawy RT, et al. Serotonin has a key role in pathogenesis of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1649–60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margolis KG, Pothoulakis C. Serotonin has a critical role in the pathogenesis of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1562–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolis KG, Stevanovic K, Li Z, Yang QM, Oravecz T, Zambrowicz B, et al. Pharmacological reduction of mucosal but not neuronal serotonin opposes inflammation in mouse intestine. Gut. 2014;63:928–37. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SJ, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Clinical characteristics and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: A comparison of Eastern and Western perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11525–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ko JK, Auyeung KK. Inflammatory bowel disease: Etiology, pathogenesis and current therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:1082–96. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawsthorne P, Clara I, Graff LA, Bernstein KI, Carr R, Walker JR, et al. The Manitoba inflammatory bowel disease cohort study: A prospective longitudinal evaluation of the use of complementary and alternative medicine services and products. Gut. 2012;61:521–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opheim R, Bernklev T, Fagermoen MS, Cvancarova M, Moum B. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Results of a cross-sectional study in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1436–47. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.725092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J, Li J, Zheng SR, Jin Y, Huang Y. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of Yupingfeng powder on chronic bronchitis rats. Chin J Integr Med. 2013;19:353–9. doi: 10.1007/s11655-013-1442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao J, Li J, Shao X, Jin Y, Lü XW, Ge JF, et al. Antiinflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of total glucosides of Yupingfeng powder. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1636–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenjin W. Therapeutic effect of yupingfeng powder on chronic diarrhea in children. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med. 2013;22:150–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng RD, Wu L, Zhang R, Wang ZX. Yupingfeng powder immunomodulatory effects on children with persistent diarrhea. Chin J Immunol. 2014;30:61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teixeira LB, Epifânio VL, Lachat JJ, Foss NT, Coutinho-Netto J. Oral treatment with Hev b 13 ameliorates experimental colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junying Z, Lifeng Z, Dongfeng W, Chen C, Weidong C, Yingcun B, et al. Comparative study of radix hedyseri and radix astragali alternative yupingfeng san on apoptosis of spleen lymphocyte in aging mice. Pharmacol Clin Chin Mater Med. 2013;29:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu X, Fan T, Li W, Huang H, Zhang Y, Xing W. Protective effect of sanguinarine against acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;267:256–65. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam MS, Murata T, Fujisawa M, Nagasaka R, Ushio H, Bari AM, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of phytosteryl ferulates in colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:812–24. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris GP, Beck PL, Herridge MS, Depew WT, Szewczuk MR, Wallace JL. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Kang A, Dai C, Liang Y, Xie T, Xie L, et al. Quantitative analysis of neurochemical panel in rat brain and plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84:10044–51. doi: 10.1021/ac3025202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costedio MM, Coates MD, Danielson AB, Buttolph TR, 3rd, Blaszyk HJ, Mawe GM, et al. Serotonin signaling in diverticular disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1439–45. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0536-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Margolis KG, Stevanovic K, Li Z, Yang QM, Oravecz T, Zambrowicz B, et al. Pharmacological reduction of mucosal but not neuronal serotonin opposes inflammation in mouse intestine. Gut. 2014;63:928–37. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jun G, Jinjin J, Chaobin S, Lei L, Qiang D, Kuangcheng X, et al. Effects of “jude-screen powder” on Th1/Th2 balance in mice model of systemic allergic airway disease. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;39:50–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen D, Xie X, Zhu Z, Yu X, Liu H, Wang H, et al. Screening active components from Yu-ping-feng-san for regulating initiative key factors in allergic sensitization. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]