Abstract

Objective:

The study is aimed to evaluate anti-inflammatory activity of Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) flower extract (CBFE) and to study its effect on radiographic outcome in adjuvant induced arthritis and authentication by high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) chemical fingerprinting.

Materials and Methods:

CBFE was administered orally (30, 100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt.) and tested for its anti-inflammatory activity in carrageenan-induced inflammation, cotton pellet induced chronic granulomatous inflammation and autacoids-induced inflammation. Effect on radiographic outcome was tested in adjuvant-induced arthritis. CBFE was HPTLC fingerprinted in suitable solvent system.

Result:

In carrageenan-induced inflammation, CBFE produced significant inhibition in edema volume at all the doses (30, 100 and 300 mg/kg b.wt.) and percentage of inhibition was 28.68, 31.00, and 22.48, respectively as compared to control at 5 h of its administration. In cotton pellet granuloma assay, CBFE significantly decreased the granuloma weight at 300 mg/kg dose level by 22.53%. CBFE (300 mg/kg) caused significant inhibition by 37.5, 44.44, and 35.29% edema volume, at ½, 1 and 3 h after 5-hydroxytryptamine injection, respectively. Radiographic score of animals treated with 300 mg/kg CBFE was significantly decreased when compared to arthritic control animals.

Conclusion:

The extract was found to possess significant anti-inflammatory activity. CBFE treatment improved the bony architecture in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. The developed HPTLC fingerprint would be helpful in the authentication of C. bonducella flower extract.

KEY WORDS: 5-hydroxy tryptamine, Caesalpinia bonducella, carrageenan-induced inflammation, cotton pellet granuloma, high performance thin layer chromatography, radiography

Introduction

Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) is a shrub found in coastal areas of South Asian countries. Various parts are used for different purposes in ethno pharmacology.[1] Previous investigations have revealed analgesic, antipyretic[2] anthelmintic, antimicrobial, hypoglycemic, and antihyperglycemic effects of seed and potent analgesic effect of ethanolic extract of flowers.[3] Another plant of this genus, C. pulcherrima Swartz was known to possess various pharmacological properties and the presence of peltogynoids, flavonoids, diterpene esters, and ellagitannins have been reported. Infusions of flowers were prescribed in bronchitis, as tonic and emmenagogue and found to possess anticancer properties.[1] Flavonoids possessing anti-inflammatory activity were isolated from C. pulcherrima.[4] There is no information available on anti-inflammatory activity of C. bonducella Fleming (Caesalpineacea) flower extract (CBFE). Chemical fingerprinting will serve as an effective tool in authentication and quality control of herbs. Chromatography can readily ascertain the presence of the essential chemical constituents of a medicinal plant and detection of their presence in a drug preparation.[5] Different chemical fingerprint analysis is currently developed for quality control in Chinese medicine and has been accepted by the World Health Organization for the assessment of herbal medicines.[6] The State Food and Drug Administration of China require all herbal medicine-derived injections and related materials to use chromatographic fingerprints[7] in standardization. High performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) is being used for fingerprint profiling of medicinal plant extracts since long. HPTLC fingerprint profile has been proved to be an effective tool in differentiating closely related species and detecting adulteration and substitution in raw drugs of Indian systems of medicine.[8] The technique is used in standardization of many medicinal raw drugs used in Indian system of medicine. Hence, this study was carried out to investigate anti-inflammatory activity of CBFE and to study its effect on radiographic outcome in adjuvant induced arthritis and its authentication by HPTLC chemical finger printing.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Flowers of C. bonducella were collected in September, from Bareilly and botanically identified by Dr. B.N. Pandey, Department of Botany, Bareilly College, Bareilly (India). The voucher specimen (ID: 2000:23) was deposited in the herbarium of the Division of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar (India).

Extraction Procedure

Wilted flowers were shade dried, powdered and extracted with 70% ethanol (80°C) under reflux for 8 h. The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and made free of solvent to obtain a semisolid mass (yield 6.82%). In the preliminary phytochemical screening, CBFE was found to have flavonoids, terpene, tannin, and chlorophyll.[9]

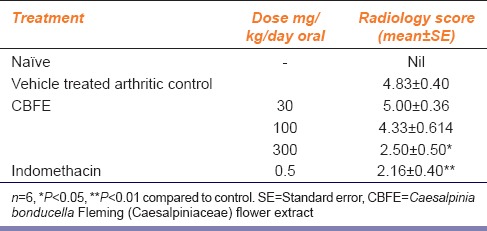

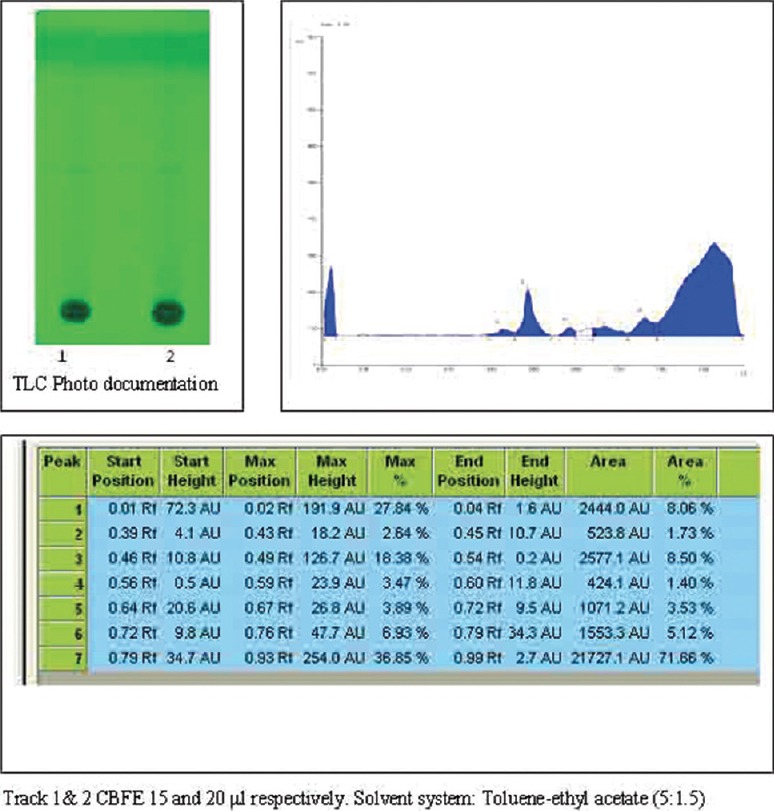

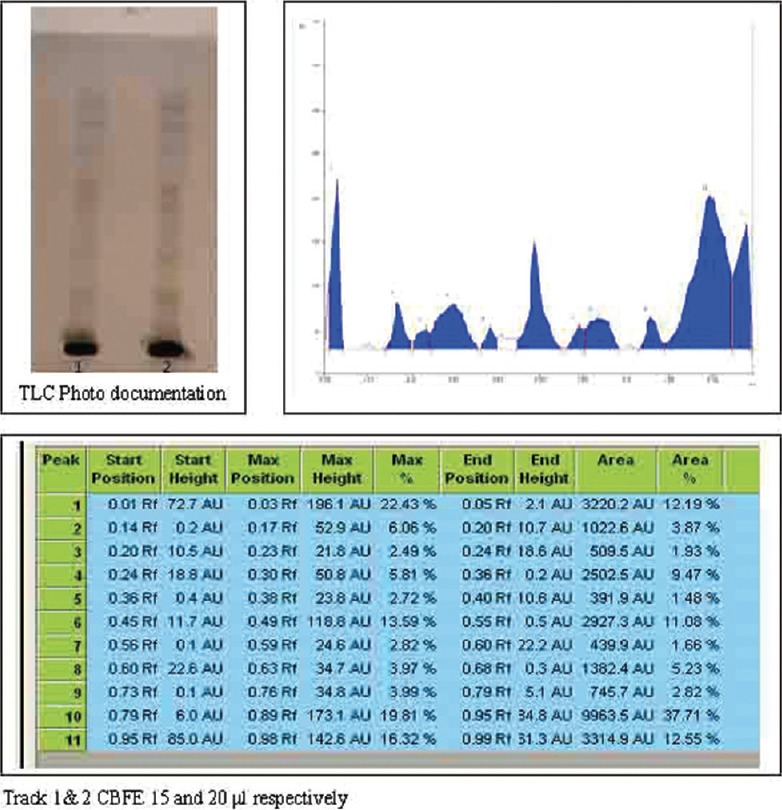

High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography Fingerprinting of Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) Flower Extract

4 g of wilted flower was shade dried, powdered extracted with 40 ml of 70% ethanol (80°C) under reflux for 8 h. The extract was concentrated to 10 ml solution under reduced pressure. From this solution, 20 µl and 15 µl were applied on a precoated silica gel 60 F254 (E. Merk) of 2 mm thickness aluminum plates to a band width of 6 mm using CAMAG HPTLC system equipped with TLC Linomat IV applicator, TLC scanner 3 and win CATS 1.4.4. software was used for HPTLC analysis. The plate was developed in a solvent system of toluene and ethyl acetate in the proportion of 5 and 1.5 up to 80 mm and the developed plates were visualized and scanned under ultraviolet (UV) 254 nm (D2 lamp) and 366 nm (Hg lamp) and under white light at 520 nm (Tungsten) after derivatization in vanillin-sulfuric acid spray reagent. Rf values of the spots were recorded.

Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade and most of them were procured from Sigma Chemical Co., USA.

Animals

Wistar rats (150–180 g) and mice of either sex were procured from the Laboratory Animal Resource Section of the Institute and acclimatized to the laboratory conditions at least 1 week before experimentation. The animals were kept under standard environmental conditions and maintained on a standard rodent diet provided by Feed Technology Unit of the Institute and water was provided ad libitum. The experimental procedures were duly approved (EC No. F1-53/2000–2001) by the Institute Animal Ethics Committee, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, Bareilly, UP.

Administration of Drugs

The CBFE, aspirin, ibuprofen, and indomethacin were suspended in 1% tween 80. The volume administered was 1 ml/kg in case of rats and 10 ml/kg in case of mice.

Acute Toxicity Study

The extract was administered orally to four groups of four mice each (3, 4.5, 6.75, and 10.125 g/kg) to evaluate the acute toxicity.[10] The animals were observed for signs and symptoms of toxicity and mortality, if any, up to a period of 72 h.

Carrageenan-induced Hind Paw Edema in Rats (Acute Inflammation)

Adult male wistar rats weighing 150–180 g were randomly divided into five groups containing six animals each. Animals were fasted for 16 h but allowed fresh water ad libitum. The paw volume 0 h was measured using plethysmometer (Ugo Basile, Italy). Group I which served as control received vehicle. Group II to IV received CBFE in doses of 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt., respectively. Group V received standard drug aspirin (300 mg/kg b.w). CBFE and reference drug was administered orally 1 h before injection of phlogistic agent to the hind paw. The phlogistic agent carrageenan was prepared as 1% suspension in sterile normal saline. Carrageenan was injected (0.1 ml), subcutaneously into the plantar aponeurosis of hind paw of each rat. The volume of injected paw of each rat was measured 3 and 5 h later. The edema volume (ml) was calculated by subtracting the 0 h reading from 3 to 5 h reading. From the mean edema volume, the percentage of inhibition of edema was calculated between treated and control groups.[11]

Cotton Pellet Granuloma in Rats

The effect of the extract was studied in proliferative phase of inflammation induced by cotton pellet in wistar rats.[12] The rats were randomly divided into five groups of six animals each. Autoclaved cotton pellets weighing 35 ± 1 mg each were implanted (subcutaneously) one on each side, in the flanks or axillae of rats. From the day of cotton pellet insertion, for 7 consecutive days the oral administration of the drugs was done. Group II, III, and IV were received the test drug CBFE at the dose rate of 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt., respectively. Group V received the standard drug aspirin (200 mg/kg b.wt.) while group I served as control group receiving comparable volume of vehicle. Rats were killed on day 8 and the pellets covered by granulation tissue were dissected out and dried in hot air oven at 60°C for 48 h until constant weight was obtained. Percent inhibition was compared with the untreated control group.

5-hydroxytryptamine-induced Hind Paw Edema

Wistar rats divided into three groups and their paw volume was measured by plethysmometer; Group II served as test group and was administered CBFE 300 mg/kg b.wt. p.o. Group I served as control group which received vehicle. Group III was administered standard drug ibuprofen (30 mg/kg bw p.o.). 30 min after the drug administration, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) prepared as 1% solution was injected (0.1 ml) into the right hind paw. The volume of the injected paw was measured at ½, 1 and 3 h, post 5-HT injection. The difference from the normal paw volume was taken as the edema volume at corresponding time intervals and the percent inhibition of edema volume was calculated at different time intervals between the treated and control groups.[13]

Ulcerogenic Activity in Rats

This test is based on the procedure[14] in which the rats were randomly divided into four groups of eight animals each. Group I served as control and received the vehicle. Groups II, III and IV were given CBFE at the dose rate of 30,100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt. orally once daily for 4 days. Group V was given indomethacin 16 mg/kg b.w orally once daily for 4 days. On day 1, 6 h after dosing, half of the group (4 animals) was sacrificed, and the stomach was removed, cut along the greater curvature. Contents were washed and mucosal surface checked for presence of ulcers. Same procedure was adopted on day 4 to study the chronic ulcerogenic activity with the remaining 4 animals in all groups. Ulcerogenic score following a 5 point scale was employed.[15] Score zero was given to neither ulcer nor irritation, score 1 was given to irritation, score 2 was given to 1 or 2 ulcers, score 3 was given to 3 or 4 ulcers and score 4 was given if more than 4 ulcers.

Adjuvant-induced Arthritis

In this experiment, young female rats weighing 90–110 g were selected and divided into six animals each. Adjuvant was prepared by weighing appropriate amount of desiccated Mycobacterium butyricum to give 10 mg/ml solution and transferred into mortar in a bio-safety cabinet. The grinding surface of the pestle was moistened with water and Mycobacterium was ground to fine powder. One-third of the mineral oil was added to the mortar and the mixture was ground to create fine suspension. This procedure was repeated until all the mineral oil has been added to make the mixture into fine suspension. This mixture was prepared fresh. On day 1, the freshly prepared adjuvant was injected (0.1 ml) intradermally into the proximal quarter of the tail. Pressure was maintained at the site of injection to prevent leakage.[16] All the animals of groups I to V were injected the adjuvant except group VI, which served as a negative arthritic control group. CBFE (30, 100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt. p. o.) was administered once daily for 21 days starting from day 0 for groups II, III, and IV. Group I served as a vehicle-treated control. Group V was given indomethacin (0.5 mg/kg b.wt., p. o.). Animals were X-rayed before inducing arthritis to confirm the absence of boney lesions. At the end of the experiment, rats were premedicated with atropine (1 mg/kg s.c.) and anaesthetized by injecting ketamine (100 mg/kg i.p.) and xylazine (15 mg/kg i.m.). Anesthetized rats were placed on a radiographic box at a distance of 107 cm from the X-ray source. Radiographic analysis of normal and arthritic hind paws was performed using X-ray machine with a 48 k Vp exposure for 0.5 mAs. A blind and independent assessment of the radiological score was performed by two observers. The following radiological criteria were considered: Score 1, tissue swelling and edema; score 2, joint erosion; score 3, bone erosion and osteophyte formation.[17] Total radiology scores were calculated from the sum of both hind paws, with a maximum possible score of 6 for each rat.

Results

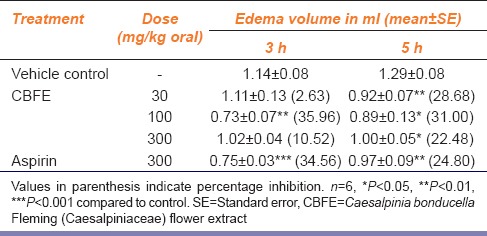

The results of oral administration of CBFE on carrageenan-induced edema are summarized in Table 1. CBFE produced significant inhibition in edema volume at all the doses (30, 100, and 300 mg/kg b.wt.) and percentage inhibition of 28.68, 31.00, and 22.48, respectively as compared to control at 5 h of its administration. The reference drug aspirin (300 mg/kg) inhibited significantly the edema at 3rd and 5th h following its administration and the percentage inhibition was found to be 34.56 and 24.80, respectively.

Table 1.

Effect of CBFE on carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats

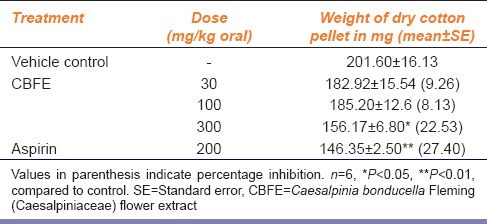

The results of orally administered CBFE on cotton pellet granuloma test in rats are summarized in Table 2. CBFE significantly decreased the granuloma weight at 300 mg/kg dose level by 22.53%. The standard drug aspirin (200 mg/kg) significantly decreased the granuloma weight by 27.40%.

Table 2.

Effect of CBFE on cotton pellet granuloma in rats

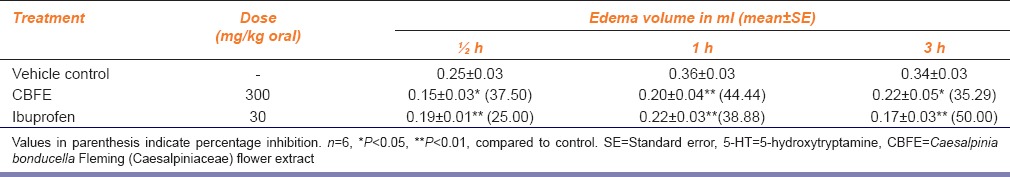

Table 3 shows the results of 5-HT induced inflammation and effect of CBFE on it. CBFE (300 mg/kg) caused significant inhibition by 37.5, 44.44 and 35.29% in edema volume, respectively at ½, 1 and 3 h of 5-HT injection. Ibuprofen (30 mg/kg) caused significant inhibition in edema volume at ½, 1 and 3 h with percent inhibition of 25, 38.88 and 50 respectively.

Table 3.

Effect of CBFE on 5-HT-induced hind paw edema in rats

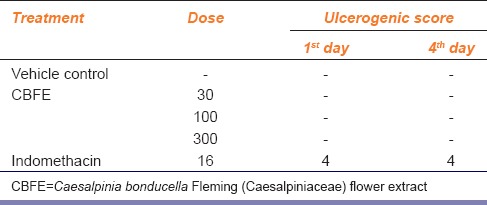

Table 4 shows the ulcerogenic score of CBFE for acute as well as chronic administration. CBFE did not produce any ulcer in both the study whereas the reference drug indomethocin which produced strong ulcers both in acute as well as chronic administration with the ulcerogenic score of four.

Table 4.

Ulcerogenic potency of CBFE in rats

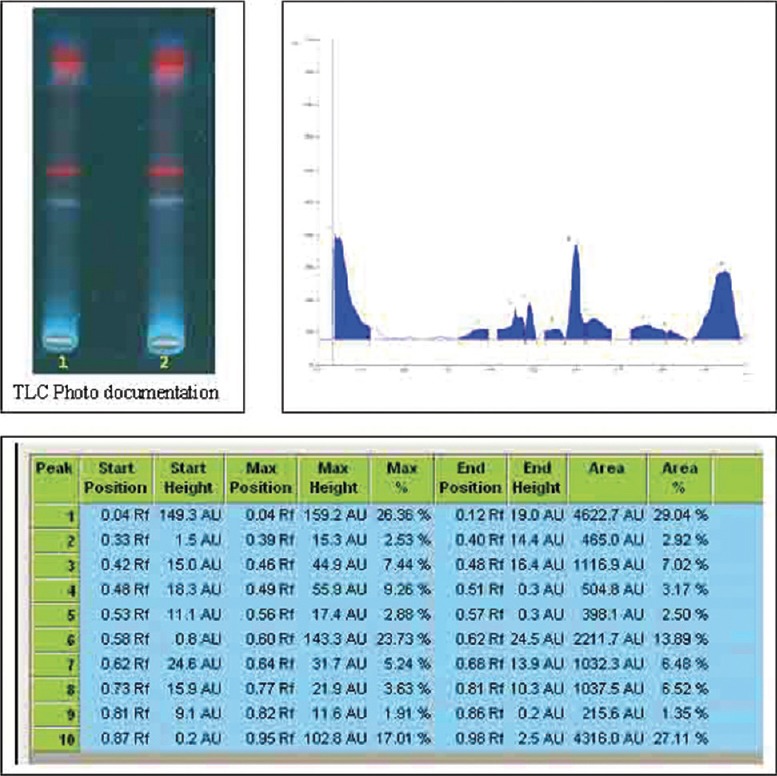

Figure 4 depicts the radiographic pictures of normal, arthritic, CBFE at 30 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg and reference drug indomethacine treated arthritic groups.

Figure 4.

Representative radiographic picture of normal, arthritic, Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) flower extract at 30 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg and reference drug indomethacine treated groups

Figure 2.

High performance thin layer chromatography finger print profile with its Rf value of Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) flower extract under 366 nm

Table 5 shows the radiographic score of the study. In negative arthritic animals, the mediolateral radiograph of pelvic limb taken before induction of arthritis showed long bones having normal radiographic density and appearance, sharp articular surfaces and well defined joint space. The metatarsus was relatively less dense. The tarsal joints were well formed with normal tarsus. Positive arthritic animals showed soft tissue swelling with lysis of epiphyseal end of the tibia. There was fluffy appearance of articular ends of tibia and femur as well. The changes were more pronounced in tarsal than stifle joint. In 30 mg CBFE-treated animals, the intensity of radiographic features of 30 mg CBFE-treated animals varied. Soft tissue swelling and osteolysis of articular surfaces of long bones were comparable to that of positive arthritic animals. Soft tissue swelling seen in animals treated with 100 mg CBFE was more or less comparable to those of arthritic animals. The integrity of articular surfaces on long bones was, however, maintained. 300 mg CBFE treated animals mild to moderate degree of soft tissue swelling was seen in animals treated with CBFE at 300 mg/kg b.wt. The articular surfaces of long bones particularly those forming stifle joint appeared fluffy. The bones which formed the tarsal joint, however, had the normal radiological appearance. In indomethacin treated animals, mild degree of soft tissue swelling was seen around the articular joint. The integrity of bone and joints was, however, maintained. In radiographic score assessment significant reduction in radiographic score observed both in 300 mg CBFE treatment and indomethacin treatment as well.

Table 5.

Mean radiological scores in different groups of rats

In HPTLC fingerprinting, CBFE on HPTLC analysis revealed 14 and 9 spots at various Rf when viewed under UV 254 nm and 366 nm. On spraying with vanillin-sulfuric acid and heating at 105°C for 5 min, 10 spots were observed at various Rf as shown in Figures 1-3.

Figure 1.

High performance thin layer chromatography finger print profile with its Rf value of Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) flower extract under 254 nm

Figure 3.

High performance thin layer chromatography finger print profile along with its Rf value of Caesalpinia bonducella Fleming (Caesalpiniaceae) flower extract after derivatisation with vanillin-sulphuric acid reagent

Discussion

In this study, acute inflammation was induced by injecting 0.01 ml of 1% carrageenan into right hind paw of rats. The development of edema in the paw of rat after injection of carrageenan is a biphasic event. The initial phase (1 h) of the edema has been attributed to the release of histamine and serotonin, the edema with increased vascular permeability maintained during the plateau phase to kinin-like substances (up to 2 h) and second accelerating phase of swelling which was associated with migration of leucocytes (2½–6 h) to the release of prostaglandin like substances.[18] Anti-inflammatory activity was noticed in CBFE as comparable to that of reference drug. We observed that the effect was dose-dependent at 30 and 100 mg of CBFE. Hence, it can be assumed that at these dose levels CBFE is more effective. To assess the efficacy of CBFE against chronic inflammation, cotton pellet granuloma test was employed. This model is an indicator of proliferative phase of inflammation. Inflammation involves proliferation of macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and multiplication of small blood vessels, which are the basic source of forming a highly vascularized reddish mass, termed granulation tissue. At 300 mg/kg level, CBFE showed significant decrease in granuloma weight indicating suppression of proliferative phase by extract. Along with flavonoids and terpinoids, other phytochemical principles such as tannins may also contribute to the anti-inflammatory effect of CBFE. Potent anti-inflammatory activity of C. bonducella seed coat extract has been reported.[19] Autacoids are one of the most important mediators of inflammation. They sensitize the nerve ending for pain sensation and enhance the inflammatory mediators to be released at the site of insult. Most of the anti-inflammatory drugs possessing varying levels on inhibition at autocoid level potentiate the anti-inflammatory effect. Prostaglandins produced by inflamed tissue sensitize nociceptors to inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin and 5-HT.[20] Therefore, to elucidate the probable mechanisms of action, autacoids-induced inflammation models were used. In 5-HT induced edema, CBFE and ibuprofen inhibited the edema volume significantly from ½ h to 3 h. This shows that both CBFE and ibuprofen may antagonize the 5-HT - induced inflammation or reduce the sensitization or facilitation of 5-HT edema by PGE2.

The adjuvant induced arthritis model in rat has been used for many years for evaluation of antiarthritic/anti-inflammatory agents and is well characterized. In our laboratory conditions, young female rats weighing 90–100 g alone developed arthritis effectively. These animals developed chronic swelling in multiple joints, with influx of inflammatory cells, erosion of joint cartilage and bone destruction. These inflammatory changes ultimately result in the complete destruction of joint integrity and function of the affected joints. Anti-inflammatory drugs like cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, such as indomethacin, which has been useful for the treatment in human diseases, ameliorates the joint inflammation in this rat model.[21] The rat adjuvant model is also useful for the development of newer therapeutic agents, such as COX-2 inhibitors.[22] Phyto constituents like flavonoids seems to modulate functioning of immune and nonimmune inflammatory cells.[23] Suppression of inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factors-α, PGs and NO) and the inhibition of inducible COX and nitric oxide synthase enzymes by plant flavonoids have been reported in stimulated macrophages.[24]

Radiographs provide a measure of damage that occurs in patients with arthritis. Macrophages are the initiators of the pathogenic cascade in rheumatic arthritis pathology. When macrophages are activated in the synovial tissue, they are involved in the activation of inflammatory cells, cell contact, over expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and cytokine production. Auto antibody production results in antigen antibody reaction leads to compliment cascade activation. These reactions results in fluid accumulation in the synovium and damage in joints results in increased arthritic score.[25] Prostaglandins are among the mediators, treatment with indomethacin protected the bone damage. CBFE at 300 mg/kg bw and reference drug indomethacin 0.5 mg/kg bw significantly reduced the arthritic score compared to vehicle treated arthritic animals. The HPTLC fingerprinting analysis showed that CBFE possess various phytochemicals with high biological profile.

Limitations of the Study

Part of the plant used in this study is flowers. Being seasonal, availability may be a problem during other seasons. Shelf life study may be required for effectiveness of the extract and to decide its half-life.

Conclusion

CBFE is effective for acute and chronic inflammatory conditions in rats. Although the extract is comparable to that of reference drugs, the side effects observed with standard drugs like ulcerogenicity was not present with CBFE treatment. The developed HPTLC chromatographic system will be useful for authentication of the extract.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly thankful to Direct General ICAR, Director General CCRAS and Assistant Director In charge, CSMRIASDD for providing facility to carry out the work.

References

- 1.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. New Delhi: CSIR; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archana P, Tandan SK, Chandra S, Lal J. Antipyretic and analgesic activities of Caesalpinia bonducella seed kernel extract. Phytother Res. 2005;19:376–81. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devi RA, Tandan SK, Kumar D, Dudhgaonkar SP, Lal J. Analgesic activity of Caesalpinia bonducella flower extract. Pharm Biol. 2008;46:668–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao YK, Fang SH, Tzeng YM. Anti-inflammatory activities of flavonoids isolated from Caesalpinia pulcherrima. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stahl I. Thin Layer Chromatography: A Laboratory Hand Book (Student edition) Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1969. pp. 52–86. 127-8, 903-4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. World Health Organization. Quality Control Methods for Medicinal Plant Materials; pp. 16–20. 25-8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beijing: SFDA; 2000. State Food and Drug Administration of China. Technical Requirements for the Development of Fingerprints of TCM Injections. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saraswathy A. HPTLC finger printing of some ayurveda drugs and their substitutes/adulterants. Indian Drugs. 2003;40:462–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peach K, Tracey MV. Modern Methods of Plant Analysis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weil CS. Tables for convenient calculation of median effective dose (LD50 or ED50) and instructions in their use. Biometrics. 1952;8:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenan-induced oedema in the hind paw of rat as an assay for anti-inflammatory activity. Proc Soc Exp Biol Ther. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter CA, Porter CC. Effect of alterations in side chain upon anti-inflammatory and liver glycogen activities of hydrocortisone esters. J Am Pharm Assoc Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:515–9. doi: 10.1002/jps.3030460902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh RK, Pandey BL. Anti-inflammatory activity of seed extracts of Pongamia pinnata in rat. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;40:355–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteley PE, Dalrymple SA. Models of inflammation: Measuring gastrointestinal ulceration in the rat. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2001;1010:2. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1002s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lwoff JM. Ulcerogenic Activity in the Rat. J Pharmacol (Paris) 1971;2:81–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiteley PE, Dalrymple SA. Protocols in Pharmacology. Vol. 55. Somerset NJ: John-Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1998. Models of inflammation: Adjuvant induced arthritis in rat; pp. 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Serraino I, Britti D, De Maio M, et al. Absence of endogeneous interleukin-10 enhances the evolution of murine type-II collagen-induced arthritis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2001;12:568–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinegar R, Schreiber W, Hugo R. Biphasic development of carrageenin edema in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969;166:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannur DM, Paranjpe MP, Sonavane LV, Dongre PP, Khandelwal KR. Evaluation of Caesalpinia bonduc seed coat extract for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2012;3:171–5. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.101010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Randall D, Neil KE. 2nd ed. Vol. 29. United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. Pain management. Disease Management: A Guide to Clinical Pharmacology; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Arman CG. Pathway to adjuvant arthritis. Fed Proc. 1976;35:2442–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visco D, Widmer R, Shen F, Orevillo C, Christen A, Chan CC, et al. Presented at the 10th International Conference on Prostaglandins and Related Compounds; 1996. The Effects of a Selective Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) Inhibitor on Adjuvant-induced Arthritis in the Rat; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middleton E, Jr, Kandaswami C. Effects of flavonoids on immune and inflammatory cell functions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1167–79. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manthey JA, Grohmann K, Montanari A, Ash K, Manthey CL. Polymethoxylated flavones derived from citrus suppress tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression by human monocytes. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:441–4. doi: 10.1021/np980431j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinne RW, Bräuer R, Stuhlmüller B, Palombo-Kinne E, Burmester GR. Macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:189–202. doi: 10.1186/ar86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]