Abstract

Aim:

Black grape peel possesses a substantial amount of polyphenolic antimicrobial compounds that can be used for controlling the growth of pathogenic microorganisms. The purpose of this study was to assess antibacterial and antifungal activity of black grape peel extracts against antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria and toxin producing molds, respectively.

Materials and Methods:

Peel of grape was subjected to polyphenolic extraction using different solvents viz., water, ethanol, acetone, and methanol. Antibiotic-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterobacter aerogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, and Escherichia coli were screened for the antibacterial activity of different grape extracts. Antibacterial activity was analyzed using agar well diffusion method. Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium expansum, Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus versicolor were screened for the antifungal activity. Antifungal activity was determined by counting nongerminated spores in the presence of peel extracts.

Results:

As compared to other solvent extracts, methanol extracts possessed high antibacterial and antifungal activity. S. typhimurium and E. coli showed complete resistance against antibacterial action at screened concentrations of grape peel extracts. Maximum zone of inhibition was found in case of S. aureus, i.e., 22 mm followed by E. faecalis and E. aerogenes, i.e., 18 and 21 mm, respectively, at 1080 mg tannic acid equivalent (TAE)/ml. The maximum and minimum percent of growth inhibition was shown by P. expansum and A. niger as 73% and 15% at 1080 TAE/ml concentration of grape peel extract, respectively.

Conclusions:

Except S. typhimurium and E. coli, growth of all bacterial and mold species were found to be significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited by all the solvent extracts.

KEY WORDS: Antibacterial activity, antifungal activity, polyphenolic compounds, Vitis vinifera L, zone of inhibition

Introduction

Today scientist community is running a race of making drugs and antimicrobial systems for limiting the growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacterial species and toxin producing molds. In this race, extracts containing polyphenols of plant origin gained more attention of researchers for their use against drug-resistant food borne pathogens.[1] Moreover, antimicrobials or antibiotics from these sources have been found to work more efficiently with fewer side effects and less cost of production.[2,3]

Black grape (Vitis vinifera) skin or is a great source of phenolic compounds. Grape polyphenols contain from simple compounds (monomers) to complex tannin type substances (oligomers and polymers). There are many classes of negatively charged polyphenols have been identified in grapes, such as phenolic acids (benzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids), stilbene derivatives (resveratrol), flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin), flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), anthocyanins, etc.[4] These polyphenols possesses many beneficial effects on human health such as inhibition of free radical damage, antibacterial, antifungal, decreasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, etc.[4,5,6,7]

As an antimicrobial agent, these polyphenols can penetrate the semi permeable cell membrane where they react with the cytoplasm or cellular proteins. This potential is higher in grape peel extract as phenolic acids are present in un-dissociated form.[8] Therefore, these highly negative charged antimicrobial polyphenolic compounds can be used for combating the growth of antibiotic resistant pathogenic bacteria and toxin producing molds. From the extraction point of view, different kind of solvents can be used as the solubility of polyphenols depends on the aqueous and nonaqueous medium.[9,10,11]

The objective of this in vitro study was to screen antimicrobial activity of different grape peel extracts against antibiotic resistant bacterial species and toxin producing molds. Antibacterial activity was assessed against Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterobacter aerogenes, Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. These bacteria are well known for food borne pathogenesis. Their growth may cause the death of the patient. Antifungal activity was analyzed against Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium expansum, Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus versicolor. The mold used in this investigation are known for their mycotoxins production and toxic nature. A. niger, A. versicolor, P. expansum (blue mold) and P. chrysogenum produces ochratoxin, sterigmatocystin, patulin and citrinin, respectively. Ochratoxin and citrinin are nephrotoxic; sterigmatocystin is mutagenic and tumigenic while patulin is genotoxic in nature.[12]

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Chemicals

Sharad seedless variety of black grape (V. vinifera L.) was purchased from the local market, Varanasi (India). All the chemicals used were procured from Himedia and Merck (Mumbai, India).

Microbial Cultures

Amoxycillin, cloxacillin, and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus; amoxycillin and ampicillin resistant E. aerogenes; vancomycin and gentamycin resistant E. faecalis; ciprofloxacin resistant S. typhimurium; cloxacillin and gentamycin resistant E. coli (collected from human infections) were provided by Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi (India). Before use, the antibiotic resistant nature was further verified by us. P. chrysogenum, P. expansum, A. niger and A. versicolor were provided by Department of Plant Pathology, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi (India).

Preparation of Extracts

Black grapes were washed thoroughly with water to remove dirt particles. Washed grapes were then depeeled manually and peel was mixed with different solvents for the solvent extraction in the ratio 1:10 (grapes: Volume of solvent). Thereafter, the mixture was placed in a shaker incubator at 50°C temperature and 150 rpm for 12 h. Each extract was then filtered with whatman paper number 1 to separate polyphenols of black grapes in solvent and cell mass of grapes. This process was repeated up to 3 times to ensure complete migration of polyphenolic compounds to solvent, which was indicated by the color of peel. Every extract was vacuum oven dried at 50°C for the assessment of total phenolic content, antibacterial and antifungal activity.

Total Phenolic Content Determination

The total phenolic content of the extracts was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteau method with some modifications.[13] 5 g/50 ml of sample was filtered with whatman number 1 paper. To 0.5 ml of the sample, 2.5 ml of 0.2 N Folin–Ciocalteau reagent was added and kept at room temperature for 5 min. After that, 2 ml of sodium carbonate (75 g/l) was added to reaction mixture and the total volume was made up to 25 ml using distilled water. The solution was then kept for incubation at room temperature for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 760 nm using 1 cm cuvette in ultraviolet - 1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). All procedures were performed with three replicates. Tannic acid (0.1–0.5 mg/ml) was used to produce a standard calibration curve. The correlation equation constructed with tannic acid was y = 1.633X (R2 = 0.985). Total phenolic content was expressed as milligrams of tannic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg TAE/g).

Antibacterial Activity Determination

S. aureus, E. aerogenes, E. faecalis S. typhimurium and E. coli were cultured in Mueller hinton (MH) broth at 37°C. The agar well diffusion method as described by Uhlman et al.[14] was used for screening the antagonistic activity of the extracts against different pathogenic microbes. MH agar (38 g/l) plates were inoculated with 106 colony forming units per ml of overnight cultures of the corresponding indicator bacterial strain. Wells were done on agar with the back of a sterile pasteur pipette and 10 μl of each extract containing 260 mg TAE/ml (A1), 540 mg TAE/ml (A2) and 1080 mg TAE/ml (A3) of grapes extract were inoculated in each well. After diffusion, plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Bacterial growth was inhibited by different extracts leads to the formation of inhibition zones. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of inhibition zones with no bacterial growth in mm. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration where no viability was observed after 24 h on the basis of zones of growth. All the determinations were conducted in triplicates.

Antifungal Activity

Antifungal activity determined as a percent of inhibition of conidia germination. The effect of grape peel extracts on the conidia germination was carried out according to the method described by Droby et al.[15] P. chrysogenum NCIM 709, P. expansum MTCC 2006, A. niger NCIM 596 and A. versicolor NCIM 698 were stored on potato dextrose agar (PDA) slants at 4°C and grown on PDA plates for 1 week at 25°C. From 2 weeks old cultures grown on PDA, was used to prepare spore suspensions. Conidia were removed from the surface of the cultures with a sterile bacteriological loop in 5 ml of sterile distilled water. Thereafter, suspensions were filtered through four layered muslin cloth to remove fungal mycelia. Spore concentration was estimated with a hemacytometer and the concentration was adjusted to 6 × 106 spores/ml. Aliquots of 100 μl of spore suspension of indicator fungal species were added to the wells of tissue culture plates containing 900 μl of PDA containing 260 mg TAE/ml, 540 mg TAE/ml and 1080 mg TAE/ml of grapes extract. Thirty μl aliquots were placed on sterile microscope slides and incubated at 30°C for 24 h under dark conditions in sterile petri dishes lined with moist filter paper. After that, germinated and nongerminated spores were visualized under a microscope and represented as an antifungal activity. All treatments consisted of three replicates and experiments were repeated 3 times.

Antifungal activity (percent of inhibition of growth) = Spores not germinated/number of spores present in control × 100

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was tested by employing one-way and two-way analysis of variance and comparison between means was made by least significant difference pair-wise comparison with the help of Microsoft excel and Systat software.

Results

Total Phenolic Content

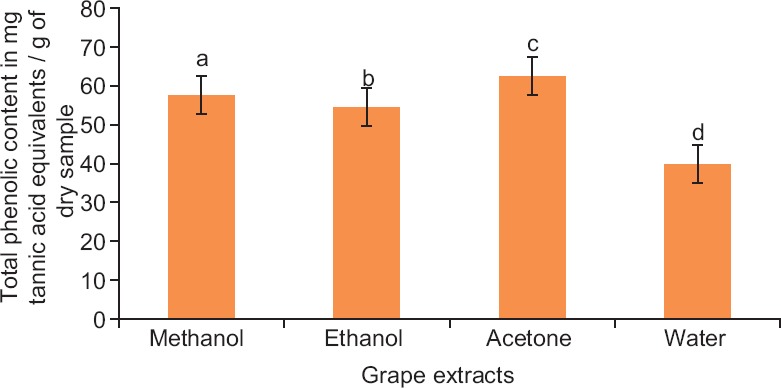

It can be clearly seen from Figure 1 that acetone extract exhibited high phenolic content, i.e., 62.44 mg/g of dry sample. All the finding were statistically justified at P < 0.05 and found significantly different. The ability to extract polyphenols was as follows:

Figure 1.

Total phenolic content of grape extracts. Each value is mean ± standard error of mean of triplicate samples and bars with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Acetone extracts > Methanol extracts > Ethanol extracts > Water extracts

Antibacterial Activity

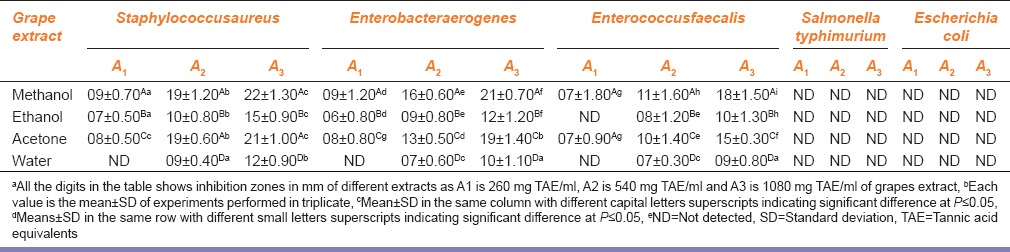

Antibacterial activity of different extracts is represented in Table 1. Methanol and acetone extracts showed MIC of 260 mg TAE/ml polyphenols against S. aureus, E. aerogenes and E. faecalis. Ethanol extracts followed the same pattern of MIC at 260 mg TAE/ml except against E. faecalis, which showed MIC of 540 mg TAE/ml. Whereas, water extracts showed the MIC 540 mg TAE/ml against S. aureus, E. aerogenes, and E. faecalis. Data from Table 1 clearly indicates that S. typhimurium and E. coli was found completely resistant against the antibacterial action of grape peel extracts screened at all concentrations.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of different grape extracts

Antifungal Activity

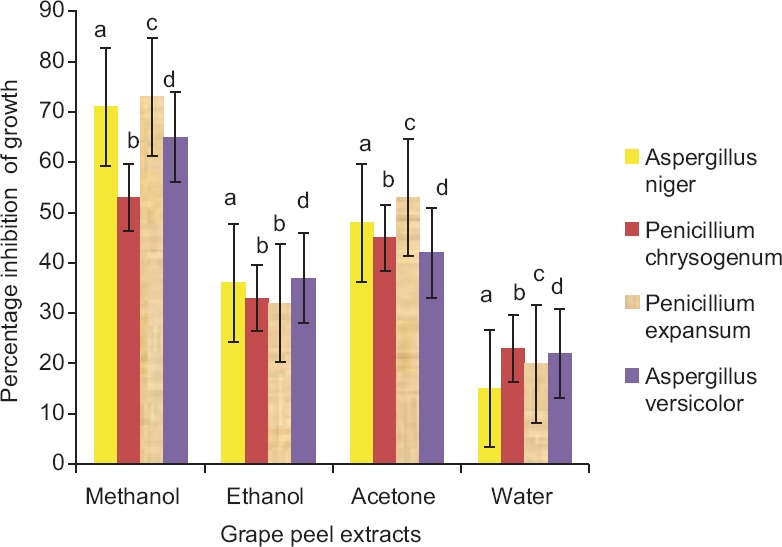

Grape peel extracts at a concentration of is 260, 540 and 1080 mg TAE/ml were screened against the growth of different molds; P. chrysogenum, P. expansum, A. niger and A. versicolor. The trend of mold growth inhibition observed was as follows [Figure 2]:

Figure 2.

Growth inhibition of different molds by solvent extracts (1080 mg tannic acid equivalent/ml). Each value is mean ± standard error of mean of triplicate samples and within the group, bars with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Methanol extracts > Acetone extracts > Ethanol extracts > Water extracts

The results were found significantly (P < 0.05) different among the fungistatic effects of peel in all four solvents. As the concentrations of extracts were increasing, the percentage of inhibition was increasing. The MIC of all extracts (except ethanol and water extracts against A. niger) was found at 260 TAE/ml. On the other hand, MIC of ethanol and water extracts was noticed at 540 TAE/ml. P. expansum showed maximum (73%) and A. niger exhibited least percent of growth inhibition (15%) on antibacterial action of methanol and water extract (at 1080 TAE/ml), respectively.

Discussion

Total Phenolic Content

Black grapes have their color because of the presence of anthocyanins, which is present in a huge amount as compared to other polyphenolic compounds. The amount of total polyphenols in the black grape varieties is higher as compared to that of green grapes, due to the presence of the anthocyanins.[16] Thus, the solvent extract which possess higher polyphenolic contents will have maximum extractability of anthocyanins. In the present study, acetone was proved to be a better solvent for the extraction polyphenols from different grape fractions, showing resemblance with Cheng et al.[11] who found that acetone was more efficient than methanol and ethanol for the extraction of polyphenols from red grapes. Although, Oki et al.[10] reported methanol and 70% acetone as better solvents for catechin and procyanidins extraction, respectively. Thus, found 3 times higher value of total soluble solids and polyphenols on the extraction of red-hulled rice using methanol rather than water. However, Arts and Hollman[9] obtained maximum catechin yields in case of both acetone and methanol (On the other hand, methanol is more acceptable to work with). They also found that the extraction process is greatly influenced by type and concentration of the solvent. Variations were justified by the well-known tendency of phenols to combine themselves through polymerization reactions during oxidation.[15]

Antibacterial Activity

Black grape contains a higher amount of dimers and trimers of (-) epicatechin which possess a higher antimicrobial activity than monomer ones.[4] Scalbert[15] proposed that the antibacterial activity of tannins could be due to the inhibition of extracellular microbial enzymes, can be a reason for antibacterial action of black grape. Moreover, the complexation of metal ions from the bacterial growth environment could also be a possible mechanism for their antimicrobial properties. Almost similar results were obtained by Nirmala and Narendhirakannan[17] found that the inhibition zone of ethanolic extract of grape (Muscat variety) skin extract against S. aureus and E. faecalis was 7 mm and 5.9 mm at 250 mg/ml grape skin extract, respectively. The maximum inhibition zone was observed in methanolic extracts than acetone, ethanolic and water extracts, infers that antimicrobial compounds from grape peel are more soluble in methanol, showed resemblance with Cheng et al.[11] The present study was found complementary to those reported by Baydar et al.[18] and Ozkan et al.[19] in which they showed that different mixture of solvents containing polyphenols from black grape, significantly inhibited the growth of E. aerogenes, E. faecalis and S. aureus. Our study was also found in agreement with Papadopoulou et al.[20] demonstrated that S. aureus was most sensitive against antibacterial action of wine extracts and showed 25 mm inhibition zone at 21,200 mg gallic acid equivalent/liter. Our findings revealed that S. typhimurium and E. coli were resistant at all concentrations of grape polyphenols. S. typhimurium and E. coli are Gram-negative bacteria. It may be possible that the lipo-polysacharidic wall of Gram-negative bacteria represented a great barrier for extracted polyphenols to get into the cytoplasm, hence no inhibition was achieved. Similarly, Oliveira et al.,[4] Kabir et al.[7] Nirmala and Narendhirakannan[17] Ozkan et al.[19] and Papadopoulou et al.[20] found that S. typhimurium and E. coli were quite resistant against antimicrobial action of grape extracts.

Antifungal Activity

Grape peel contains significant amount of catechins and epicatechins.[3] Catechins and other polyphenols are highly negative charged phytochemicals, which can be related to antifungal activity of black grape.[14,21] Even though, acetone extract was having great amount of polyphenols, but it showed less antifungal activity as compared to methanol extract. Solvent differential solubility of antifungal compounds leads to variation in the percentage of growth inhibition. Some growth retarding effect has been attributed to isolated phenolic acids such as coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, and sinapic acid as well as to isolated flavonoids such as (+)-catechin, kaempferol and quercetin.[14,12] Hence, the presence and solubility of some of these compounds in extracts is likely to be responsible for the growth inhibitory effect of different extracts.

Conclusions

So far, acetone was very active in extracting polyphenolic compounds but it was not effective as methanol in extracting antibacterial and antifungal compounds from black grapes. Except S. typhimurium and E.coli, growth of all bacterial and mold species were found to be greatly inhibited by all the solvent extracts.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for funding this research in Banaras Hindu University (Varanasi), India.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for funding this research in Banaras Hindu University (Varanasi), India. We are also highly thankful to Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences and Department of Plant pathology, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University for providing facilities, bacteria and molds for this study.

References

- 1.Siva R, Palackan MG, Maimoon L, Geetha T, Bhakta D, Balamurugan P, et al. Evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant properties of some food dyes. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2011;20:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khushwaha A, Singh RP, Gupta V, Singh M. Antimicrobial properties of peels of citrus fruits. Int J Univers Pharm Life Sci. 2012;2:24–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nurmahani MM, Osman A, Hamid AA, Ghazali FM, Dek MS. Antibacterial property of Hylocereus polyrhizus and Hylocereus undatus peel extracts. Int Food Res J. 2012;19:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira DA, Salvador AA, Smânia A, Jr, Smânia EF, Maraschin M, Ferreira SR. Antimicrobial activity and composition profile of grape (Vitis vinifera) pomace extracts obtained by supercritical fluids. J Biotechnol. 2013;164:423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daglia M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgiev V, Ananga A, Tsolova V. Recent advances and uses of grape flavonoids as nutraceuticals. Nutrients. 2014;6:391–415. doi: 10.3390/nu6010391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabir F, Sultana MS, Kurnianta H. Antimicrobial activities of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) pomace polyphenols as a source of naturally occurring bioactive components. Afr J Biotechnol. 2015;14:2157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulus W, editor. Microbicides for the Protection of Materials – A Handbook. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1993. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arts IC, Hollman PC. Optimization of a quantitative method for the determination of catechins in fruits and legumes. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:5156–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oki T, Masuda M, Kobayashi M, Nishiba Y, Furuta S, Suda I, et al. Polymeric procyanidins as radical-scavenging components in red-hulled rice. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7524–9. doi: 10.1021/jf025841z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng VJ, Bekhit AE, McConnell M, Mros S, Zhao J. Effect of extraction solvent, waste fraction and grape variety on the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of extracts from wine residue from cool climate. Food Chem. 2012;134:474–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett JW, Klich M. Mycotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:497–516. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng W, Wang SY. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in selected herbs. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5165–70. doi: 10.1021/jf010697n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlman L, Schillinger U, Rupnow JR, Holzapfel WH. Identification and characterization of two bacteriocin-producing strains of Lactococcus lactis isolated from vegetables. Int J Food Microbiol. 1992;16:141–51. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(92)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Droby S, Wisniewski ME, Cohen L, Weiss B, Toutou D, Eilam Y, et al. Influence of CaCl2 on Penicillium digitatum, grape fruit peel tissue and biocontrol activity of Pichia guilliermondii. Biol Control. 1997;87:310–5. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalbert A. Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3875–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nirmala G, Narendhirakannan RT. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of grapes (Vitis vinifera L) seed and skin extracts – Muscat variety. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;3:242–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baydar NG, Ozkan G, Sagdic O. Total phenolic contents and antibacterial activities of grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) extracts. Food Control. 2004;15:335–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozkan G, Sagdic O, Baydar NG, Kurumahmutoglu Z. Antibacterial activities and total phenolic contents of grape pomace extracts. J Sci Food Agric. 2004;84:1807–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadopoulou C, Soulti K, Roussis IG. Potential antimicrobial activity of red and white wine phenolic extracts against strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans. Food Biotechnol. 2005;43:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia EQ, Deng GF, Guo YJ, Li HB. Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:622–46. doi: 10.3390/ijms11020622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]