Abstract

As evidence accumulates on the use of genomic tests and other health-related applications of genomic technologies, decision makers may increasingly seek support in identifying which applications have sufficiently robust evidence to suggest they might be considered for action. As an interim working process to provide such support, we developed a horizon-scanning method that assigns genomic applications to tiers defined by availability of synthesized evidence. We illustrate an application of the method to pharmacogenomics tests.

BACKGROUND

Since the Human Genome Project concluded a decade ago, the landscape of genomic medicine has become increasingly complex, burgeoning with applications for clinical or personal use.1–3 The state of evidence surrounding implementation of genetic tests, however, has been described by some as a dilemma.4 Indeed, oftentimes no guidelines exist that aid in decision making on the implementation of genomics-based technologies. When guidelines do exist, they often frustrate clinical and other audiences due to findings of insufficient evidence on their use.5 Furthermore, not all guideline development groups use the same methods to arrive at recommendations; therefore, if different groups were to address the same topic, they might come to dissimilar conclusions. As a result of this variability in methods, conclusions on the same topic may differ. Potential discrepancies may be resolved by careful comparison of guidelines; however, it would be useful to have a systematic approach that allows decision makers a horizon scanning of synthesized evidence sources relevant to the use of a particular genetic test.

The Office of Public Health Genomics (OPHG) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program, recently modified an existing classification system6 and created an evolving table of genomic tests sorted by level of evidence.7 The table presents an evidence-ordered classification of “genomic applications” (defined here as the use of gene-based tests in specific clinical scenarios, or use of genome-related information, such as knowledge about a specific variant, to aid in clinical decision making in specific clinical scenarios), rather than a classification of laboratory assays themselves. We have previously described classification of cancer genomic tests (http://blogs.cdc.gov/genomics/2012/08/23/evidence-matters-in-genomic-medicine-round-2/) and family history applications (http://blogs.cdc.gov/genomics/2012/09/27/evidence-matters-in-genomic-medicine-round-3/) into the three-tiered system in blogs that are available on the OPHG website. Here, we describe the methodological underpinnings of this system and use the example of pharmacogenomics tests to illustrate how this system can be used to classify genomic applications.

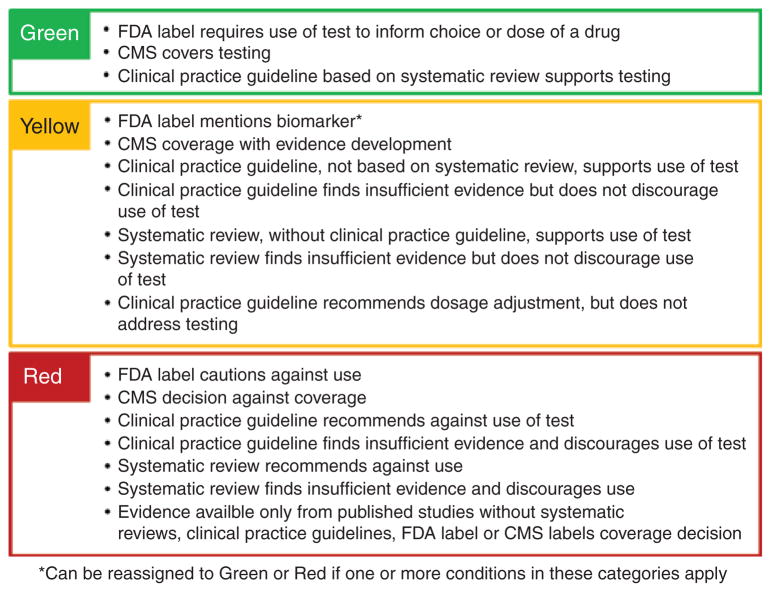

We supplement our three-tier classification system with a color scheme that emulates the workings of a traffic signal to emphasize that the evidence under consideration relates to whether or not the application is likely to be considered for action. Our classification scheme stratifies applications into three categories:

Tier 1/Green genomic applications have a base of synthesized evidence that supports implementation in practice.

Tier 2/Yellow genomic applications have synthesized evidence that is insufficient to support their implementation in routine practice. Nevertheless, the evidence may be useful for informing selective use strategies (such as in clinical trials) through individual clinical, or public health policy, decision making.

Tier 3/Red applications either (i) have synthesized evidence that supports recommendations against or discourages use, or (ii) no relevant synthesized evidence is available.

We have developed a simple classification method to aid in the tier assignment process. When coupled with the aforementioned online table, the method may be viewed as the basis of an interim, working process intended to inform critical evaluation of genomic applications by end users until the evidence base becomes more robust and more comprehensive resources (e.g., ClinGen, funded by the National Institutes of Health, which aims to catalog medically relevant human gene variants) become available. It is intended to serve as a launching point for health researchers and as a guideline for developers, policy makers, and others looking for a basic overview of the amount of synthesized evidence relevant to particular genes or tests. It offers a first, quick look at how much synthesized evidence is available for use in decision making, as well as a subjective overview of what that evidence has to say about implementation. We have designed the approach primarily to benefit an audience of clinicians and public health policy makers interested in implementing specific genomic applications. This horizon-scanning method can also point quickly to existing evidence gaps and/or lack of guidelines and recommendations. Our approach is not, however, intended to supplant clinical decision making. The approach does not prescribe how evidence synthesis or guidelines can be arrived at. The following sections describe the method and illustrate its application through the lens of pharmacogenomic applications. In tandem, we highlight salient characteristics of the processes currently used for guideline development and evidence synthesis by the many groups working to address the field of genomic medicine.

DESCRIPTION OF CLASSIFICATION METHOD

Synthesized evidence on genomic applications can be considered the input for our method, and the output is an evidence-based classification of applications. Thus, the process will not yield conclusions such as “testing for gene X is a Tier 2/Yellow application.” Instead, conclusions are of the form “testing for gene X to predict susceptibility to disease Y, in people with characteristics Z1,2,…n is a Tier 2/Yellow application.” The classification method (Figure 1) incorporates evidence derived from US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) coverage decisions, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), and systematic reviews (SRs). Classification centers on (i) intent of guidance (e.g., to inform decisions on use of a test vs. decisions on use of the results of a test) and (ii) applicability of sources, rather than methodological rigor in review or guideline development processes.

Figure 1.

Method for classification of genomic applications by levels of evidence for implementation. The list is read from top to bottom to determine whether a genomic test meets any of the criteria for each of the three color-coded categories or tiers. The listing of criteria should be viewed as “OR” statements, so only one criterion needs to be met for categorization. CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Guidelines reporting their basis to be an SR are categorized by our process as evidence based, regardless of whether the SR has been published or is publicly available. If a review process appears to have involved prespecified search terms regarding key questions, we consider it to be an SR, even if the authors did not label it as such. Examples of some major sources of evidence, and how they could be classified for use in our method, are provided in Table 1. We have not included guidelines and reviews that are primarily aimed at facilitating laboratory practice.

Table 1.

Examples of some evidence sources (i.e., CPGs and SRs) of interest in public health genomics and how their corresponding products could be classified for use with our system

| Classification | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Guidelines | ||

| ACOG (Practice Bulletin) | CPG based on SR | 55–58 |

| ACMG (Practice Guideline) | CPG based on SR | 36,59 |

| ASCO (Provisional Clinical Opinion) | CPG based on SR | 30 |

| EGAPP (Recommendation Statement) | CPG based on SR | 32,45,60–65 |

| NICE (Guidance) | CPG based on SR | 66 |

| NCCN | CPG based on SR | 31 |

| USPSTF (Recommendation Statement) | CPG based on SR | 67 |

| CPIC | CPG on dose | 34,35,39, 68–72 |

| PWG | CPG on dose | 24,25 |

| Systematic reviews | ||

| AHRQ EPC | SR | 73 |

| Cochrane | SR | 74 |

| BCBSA TEC | SR | 29 |

| CMS (Technology Assessment) | SR | 75 |

ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; ACOG, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AHRQ EPC, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; BCBSA TEC, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CPG, clinical practice guideline; CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium; EGAPP, Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; PWG, Pharmacogenetics Working Group; SR, systematic review; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

DEFINING GENOMIC APPLICATIONS

The genomic application to be classified must be clearly described before relevant evidence can be identified. Our definition process is based on methods for topic development used by the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group, and we echo its view-point that “. . . clear definition of the clinical scenario is of major importance, as the performance characteristics of a given test may vary depending on the intended use of the test, including the clinical setting (e.g., primary care, specialty settings), how the test will be applied (e.g., diagnosis or screening), and who will be tested (e.g., general population or selected high risk individuals).”8 Thus, inspired by the EGAPP and the precedent ACCE (analytic validity, clinical utility, ethical legal and social implications) model process,9 we consider the disorder, the test, and the context in which the test is used (the clinical scenario) in describing specific genomic applications.8

ASSEMBLING THE EVIDENCE

Once the genomic application has been specified, the first step toward classification is to identify the synthesized evidence to be considered. The CDC OPHG has previously created a broad-based horizon-scanning process to track the introduction of genomic applications into clinical research and practice,10 and we assess the findings for sources of synthesized evidence on genomic applications. We use regular, weekly PubMed searches to identify relevant literature, such as published SRs, and Google Alerts to probe key areas of the gray literature. We also regularly check the websites of major guideline development groups, such as the US Preventive Services Task Force,11 the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG),12 and many others, for new or updated guidelines. General resources such as the National Guideline Clearinghouse,13 National Institutes of Health Genetic Testing Registry,14 PharmGKB,15 and PubMed16 are also highly effective tools in searching for evidence. PharmGKB also includes criteria for levels of evidence for variant-drug combinations, and although these criteria differ from those presented here, the results are nonetheless useful in determining what type of evidence is available to support use of pharmacogenomics tests. The information we find on newly introduced tests and guidelines is searchable online at the Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Knowledge Base (GAPP KB) (http://www.hugenavigator.net/GAPPKB/home.do), and any information identified from synthesized evidence sources is used to update the table of genomic tests by level of evidence7 on an as-needed basis.

Identifying relevant FDA-approved drug label information is relatively simple using the FDA Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels,17 which points directly to the appropriate label sections. However, this table may not necessarily be a complete listing, e.g., cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 inclusion in the label for sertraline hydrochloride is not found in the current FDA table; therefore, additional sources may increase yield. The FDA 510(k) premarket notification database is a good source to search for approved tests that may be required in FDA labeling18; however, search fields require some previous knowledge of the device, applicant, or other specialized information. CMS coverage decisions are also relatively easy to locate in the Medicare Coverage Database19; however, the user must devise appropriate search terms to retrieve relevant information.

APPLYING THE CLASSIFICATION METHOD

After synthesized evidence for a genomic application has been identified and collected, the list of criteria (Figure 1) is simply read from top to bottom. Four sources of evidence are considered: (i) FDA drug label information, including companion diagnostic designation; (ii) CMS national coverage determination, local coverage determination, and coverage with evidence development (CED) determination; (iii) CPGs; and (iv) SRs. Examples of some major sources of evidence, and how they could be considered using our method, are provided in Table 1. If any of the evidence for the test conforms to one or more of the bulleted descriptions in the Tier 1/Green category, then the process is complete, and the assignment is Tier 1/Green. If none of the Tier 1/Green descriptions apply, then the process is repeated for the Tier 2/Yellow category and then for the Tier 3/Red category, if necessary. In general, if more than one bulleted description can be applied, then the higher tier/category is assigned. An exception occurs when the Tier 2/Yellow description “FDA label mentions biomarker” applies; in this case, reassignment to the lower category remains possible if any Tier 3/Red descriptions also apply.

Criteria for Tier 1/Green

Tier 1/Green genomic applications have been deemed ready to implement in clinical practice. There are three possible paths leading to the Green category: (i) an FDA-approved drug label requires the use of a genomic test to inform the choice or dose of a drug, or (ii) CMS covers (national coverage determination or local coverage determination) use of a genomic test, or (iii) there is at least one CPG, based on findings of an SR, that supports use of a genomic test.

Determining whether an FDA label requires a genomic application, rather than simply recommending a test or mentioning a biomarker, is not always as straightforward as it might seem, and specific examples are presented in the next section. We have chosen to use Agarwal’s proposed definition of companion diagnostics as “. . . any type of diagnostic test that must be administered before a drug can be prescribed, not just genetic or protein arrays. For inclusion, the diagnostic test must be part of the FDA approved label for the drug and language in the label must require testing and provide information on the required outcomes of the testing. Testing also must be mandated for all potential patients or at least one patient segment (e.g. women of child-bearing age, children). Drugs with labels that only recommended testing are not included nor are drugs in which the testing is at the discretion of an individual physician.”20 Therefore, presence of a biomarker in the FDA Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels17 is not in itself sufficient for Tier 1/ Green classification because the biomarker may only be mentioned in the label with no requirement for testing, as described above. In many cases, pharmacogenomic information in drug labels may not refer to genetic testing but can be an aid to clinical decision making (e.g., in warning of potential drug interactions due to common metabolic pathways) as well as the basis of a genomic application as we have defined the term above. We have considered these labels to refer to genomic applications only when relevant information on a specific genetic variant is provided; otherwise, we have excluded them from classification. Moreover, it is necessary to read the entire label carefully to determine whether or not a genomic application is required. On the other hand, no additional review is needed for applications listed in the FDA Table of Companion Diagnostic Devices: In Vitro and Imaging Tools21; because the FDA requires their use, they are classified as Tier 1/Green.

The process of determining whether a drug label actually requires testing is averted when Tier 1/Green can be assigned based on CMS coverage or based on a CPG with SR. Caveats are that with CMS decisions, although a national coverage determination or local coverage determination may qualify for Tier 1/Green, CED does not. If a CPG is the basis of Tier 1/Green assignment, then the CPG must be based on the findings of an SR covering the same clinical scenario.

Criteria for Tier 2/Yellow

The Tier 2/Yellow category designates genomic applications that may be useful in the context of informed clinical decision making. As shown in Figure 1, there are seven paths leading to the Yellow category. When an FDA label mentions a genetic test but does not require it, the genomic application is classified as Tier 2/Yellow; however, if any other criteria from Tier 3/Red or Tier 1/Green apply, it is reclassified accordingly. For example, if pharmacogenomic information is mentioned in an FDA-approved drug label, but there is no requirement for testing or other action, and a CPG recommends against use of the test, then the genomic application is classified as Tier 3/Red.

Genomic applications meeting any of the remaining Tier 2/Yellow criteria cannot be reclassified downward by our method into Tier 3/Red on the basis of additional conditions. Genomic applications covered under CMS CED are considered Tier 2/Yellow because there has been a formal decision process leading to restricted coverage with a requirement for data collection and the understanding that it will be used to facilitate reexamination of coverage in the future.22 Positive recommendations in CPGs that are not based on SRs, such as many consensus guidelines, qualify a genomic application for Tier 2/Yellow, as do positive findings from an SR that has no associated CPG. Any CPG or SR that determines there is insufficient evidence (IE) to support the use of a genomic application, but does not go on to discourage use of the test based on findings, is also a qualifier for Tier 2/Yellow. It should be noted that some guideline development groups, such as the EGAPP Working Group, qualify IE recommendations along lines of encouraging, neutral, or discouraging.8 For CPGs from groups that do not make such qualifications, we consider IE recommendations to be positive or neutral unless the authors clearly present negative contextual factors that they expect would outweigh any potential benefits from testing. Admittedly, the use of different language and different rules in stating conclusions among various groups developing SRs and CPGs can make the distinction between Tier 2/Yellow and Tier 3/Red a subjective interpretation; this may be unavoidable unless more detailed tools are used (see Discussion section).

Finally, Tier 2/Yellow contains genomic applications for which a CPG recommends dosage adjustment (or other clinical action) based on results of the test, if available, but does not address whether or not testing should be done. Guidelines from two groups devoted to pharmacogenomic applications, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium23 and the Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy’s Pharmacogenetics Working Group,24,25 address what to do with the results under the assumption that they are available, but not whether testing should be done.26 With the plummeting cost of whole-genome sequencing, there is an expectation that the existing paradigm of clinical testing for one or several genetic variants at a time will be replaced by one in which millions of results will be readily available. Critical questions will be which results should be used and how they should be used. Groups such as the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics,27 the EGAPP,28 and others have recently begun to grapple with the question of how to deal with incidental findings from whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing tests. The novel approaches to pharmacogenomic guideline development, pioneered by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and the Pharmacogenetics Working Group, seem to correspond with current thinking on how genomic information overload may be managed in the future. Nevertheless, as a basis for informed decision making on whether or not to use a test, supplementing these sources with evaluations of clinical utility may be helpful.

Criteria for Tier 3/Red

The Tier 3/Red category designates genomic applications that are not suitable for implementation in clinical practice because either there is no supporting synthesized evidence or there is evidence that potential harms outweigh potential benefits at the current time. Instances in which adequate synthesized evidence suggests that a genomic application is neither harmful nor helpful would also be considered Tier 3/Red. When there is no synthesized evidence, a coherent case can be made for not applying our classification method at all, and leaving such genomic applications unassigned until some evidence is available. Ultimately, however, this is a value judgment that various users will be able to make for themselves. In the way that we have chosen to use the classification method, there are five paths leading to the Red category, as shown in Figure 1.

Although more than 100 FDA-approved drug labels include information on pharmacogenomic biomarkers,17 we have not found any that specifically caution against use of an associated test. This path was retained in our method to address the possibility that this type of information could be included in future label revisions. CMS national coverage determinations or local coverage determinations that result in noncoverage place a genomic application in Tier 3/Red. CMS CED decisions are not considered noncoverage for the purposes of our method. CPGs (whether based on an SR or not) and SRs (whether associated with a CPG or not) that either find IE and discourage use of a test or find adequate evidence to recommend against use of a test are sufficient for Tier 3/Red placement. Finally, the lack of any synthesized evidence in the form of sources listed above results in Tier 3/Red placement.

SPECIFIC EXAMPLES

This section illustrates the use of our horizon-scanning method with several specific examples. The examples have been chosen to (i) demonstrate how the method works and (ii) present cases for which classification is difficult and involves greater use of subjective judgment. Pharmacogenomic examples are used wherever possible because they are often the most challenging in terms of classification. Readers wishing to examine results for all the genomic applications that we have classified to date are encouraged to look at the evolving online table of Genomic Tests and Family History by Levels of Evidence that is maintained and updated periodically on the CDC OPHG website.7

Tier 1/Green example

This example, of KRAS testing in metastatic colorectal cancer, illustrates how placement can change with evidence development over time. In 2008, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center issued a technology assessment29 supporting KRAS mutation analysis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who are being considered for anti–epidermal growth factor receptor therapy as a means to predict nonresponse to treatment with cetuximab or panitumumab. Rigorous technology assessments, such as those conducted by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center are considered as an SR in our method. If our method had been developed at that time, this information would have been sufficient for placing KRAS testing, with the designated clinical scenario (use in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who are being considered for anti–epidermal growth factor receptor therapy as a means to predict nonresponse. . .), into the Tier 2/Yellow category. Subsequently, however, CPGs became available in the form of an American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion,30 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, 31 and finally, a recommendation statement from the EGAPP Working Group.32 Each of these subsequent evidence sources supported testing in the same clinical scenario, and consideration of any one of them could warrant placement into Tier 1/Green. The EGAPP recommendation was based on pre-existing SRs, including the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center assessment, whereas the processes and sources described in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines were deemed sufficient to consider them based on unpublished SRs. If the method were initially applied today, the classification process would be completed based on the first criterion because there are FDA-approved products as companion diagnostic devices21 for this genomic application, which—by default—means that testing is required in the FDA labels for cetuximab and panitumumab.

Tier 2/Yellow examples

This example illustrates a step-by-step approach to categorizing TPMT (thiopurine methyltransferase) testing in patients with leukemia before treatment with mercaptopurine to inform dosage. Proceeding through the list of criteria from the top down, the first step is to determine whether an FDA label requires use of a test to inform choice or dose of a drug. The FDA Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels17 contains an entry indicating that TPMT is at least mentioned in the label contents. Following links from the table to the latest labeling revision,33 we find that “[h]eterozygous patients with low or intermediate TPMT activity accumulate higher concentrations of active thioguanine nucleotides than people with normal TPMT activity and are more likely to experience mercaptopurine toxicity,” and “TPMT genotyping or phenotyping . . . can identify patients who are homozygous deficient or have low or intermediate TPMT activity,” and that “[s]ubstantial dose reductions are generally required for homozygous-TPMT deficiency patients (two non-functional alleles) to avoid the development of life threatening bone marrow suppression.” Although this information could be used for decision making, there is no statement that testing is required. The second criterion, CMS coverage, is examined by a search of the Medicare Coverage Database19 by document type, selecting “National and Local Coverage Documents” and “Geographic Area/Region: All States,” for the keyword “TPMT.” No documents are returned from this search; hence, we move on to the last criterion for Tier 1/Green placement, a CPG based on an SR that supports testing in this clinical scenario. Our horizon-scanning efforts have returned only one CPG,34 along with a subsequent update35 from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. The original CPG contains recommendations on TPMT-based dosing but does not address whether testing should or should not be done34; therefore, we move to Tier 2/Yellow and consider where this information fits. The CPG update does not change the original recommendation but provides updated information.35 It is found that the CPG and update satisfy the last criterion listed under Tier 2/Yellow, and therefore the classification is complete. Once it was determined that Tier 1/Green criteria were not met, the FDA labeling information qualified this genomic application for Tier 2/Yellow, but this assignment would be conditional on no Tier 3/Red criteria being met.

Another informative example of Tier 2/Yellow placement is the case of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 testing in patients before treatment with warfarin to inform dosage. In 2008, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics published a CPG36 on this topic, based on an SR.37 The result was an IE statement, and although testing was not endorsed by the guideline developers, they pointed to the need for more studies, 36 so we do not consider it a “discouraging” statement. In 2009, the CMS issued a CED to cover this testing in clinical studies and under certain conditions.38 In 2011, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium issued a CPG informing dose adjustment but not use of the test.39 The FDA-approved drug label for warfarin includes information on CYP2C9 and VKORC1 but does not require that testing be done.40 Furthermore, there is an FDA 510(k)-approved genotyping assay,41 but no apparent requirement for testing. Each of the items mentioned fit neatly into one of the Tier 2/Yellow criteria, and any of these sources on their own would warrant placement in Tier 2/Yellow.

Tier 3/Red example

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 testing to inform dosage of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant drugs in adults with major depression is an example of Tier 3/Red assignment. Looking at the clinical scenario of using this testing before treatment with paroxetine to inform dosage, one finds that the FDA-approved drug label mentions CYP2D6 but does not require testing. Moreover, the label refers to an entirely different clinical scenario, involving CYP2D6 enzyme inhibition, which may result in drug interactions,42 rather than the testing-based genomic application we initially set out to classify. There is an FDA 510(k) substantial equivalence determination for a CYP2D6 genotyping test that is “intended to identify a patient’s CYP2D6 genotype . . . [which] may be used as an aid to clinicians in determining therapeutic strategy and treatment dose for therapeutics that are metabolized by the CYP2D6 gene product.”41 This description could fit the scenario of interest in this example, but again, there is no requirement for testing. An evidence review has been conducted on this topic by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-Based Practice Center,43,44 and this was the basis for a recommendation statement by the EGAPP Working Group in 2007.45 The EGAPP recommendation found IE and “discourage[d] use of CYP450 testing for patients beginning SSRI treatment until further clinical trials are completed.”45 The FDA labeling information alone would have led to classification as Tier 2/Yellow; however, this is an example of conditional classification; the IE/discouraging result of a CPG based on an SR supersedes it, and Tier 3/Red classification is the result. It is up to users to decide how far to go back temporally for including evidence. In this case, the latest labeling revision is relatively recent, whereas the superseding CPG is 6 years old. However, in most cases Tier 3/Red assignment is based on the lack of any synthesized evidence, making the classification decision straightforward.

DISCUSSION

In beginning to address questions of clinicians, healthcare payers, and patients about whether or not to offer a genomic application, cover it, or use it, simple heuristic devices can help in gathering, organizing, and understanding existing relevant evidence. Our classification method and associated table are primarily designed to answer two questions: (i) what are the sources of synthesized evidence on a particular genomic application and (ii) what do these sources have to say, in general terms, about whether or not the genomic application is ready for implementation. They are not intended to answer the ultimate question of whether or not to implement an application; rather, we hope they will help to direct decision makers toward genomic applications for which there is some supporting synthesized evidence so that more formal decision-making techniques can be focused on the most promising areas. For those who wish to base implementation on current sources of synthesized evidence, Tier 1/Green and Tier 2/Yellow listings should be of immediate assistance in obtaining an overview of which genomic applications are associated with existing supportive evidence from CPGs and SRs, as well as with information from the FDA and the CMS.

Our method classifies genomic applications into one of three categories, with implications for what available evidence has to say about implementation. In addition, this scheme points to key evidence sources that can be useful in informed decision-making processes. The approach is flexible so that modifications in evidence sources considered, or in how they are weighted, can be tailored to meet the needs and address the values of various decision makers. In many instances, the classification results convey a general idea of the types of research needed to strengthen an existing evidence base or to determine whether a genomic application may be productively implemented in the future.

We are using the classification method presented here to populate an evolving online table of Genomic Tests and Family History by Levels of Evidence.7 Because the authors are involved in public health–driven approaches to genomic implementation, being associated with CDC OPHG and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program, our approach may favor higher evidence thresholds than some would propose. Arguments could be made that applying common thresholds to all genomic applications is not warranted, or that implementation might be reasonable in some situations where no synthesized evidence is likely to be available, such as with some rare disorders. Therefore, in deciding which source material to consider “evidence-based,” we have taken a some-what liberal view. Ultimately, we acknowledge that this is an area of widespread disagreement,46 and others may choose to use our classification method with more or less restrictive criteria to account for different priorities and values. Ideally, as synthesized evidence continues to accumulate, we might expect to see movement of genomic applications away from the Tier 2/Yellow category as clear recommendations for or against use become increasingly possible. We are committed to updating the online table on a regular basis in order to test this hypothesis. We are also interested in engaging in active dialogue with researchers, policy makers, providers, and test developers on the best approaches to collecting and synthesizing evidence for genomic applications in specific scenarios. Ultimately, we plan to keep the online table as current as possible, as an ongoing service to decision makers in the field. For those whose philosophy on thresholds diverges from our approach, the method may still be helpful as a basis for modifications.

The incorporation of evidence derived from US federal sources (e.g., the FDA and the CMS) make our classification method and table a somewhat US-centered tool; however, the system could easily be modified to meet the specialized needs of other regions, e.g., by substituting European Medicines Agency information for FDA data. Our other sources, such as CPGs and SRs, have not been limited to those produced in the United States or those based on studies of the US population. Our system involves classification based on synthesized evidence in the form of SRs and CPGs rather than individual studies. We recognize that individual studies (whether clinical, cost focused, modeling based, or others) are crucial for the successful implementation of genomic tests; nevertheless, such studies must be synthesized into SRs, CPGs, and FDA and CMS decision processes if we are to thoroughly understand how they fit into the larger evidence base. Some may object to Tier 1/ Green assignment based solely on FDA labeling or CMS coverage decisions because these processes do not exactly match the model proposed in the Institute of Medicine report titled “Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.”47 Our rationale for their inclusion is that FDA drug labeling and CMS coverage decisions are constructed through defined, deliberative processes that use the best available evidence. These sources warrant a similar level of consideration as high-quality CPGs (based on SRs) when considering implementation strategies. For example, the CMS convenes the Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee as an independent consensus advisory panel that “judges the strength of the available evidence and makes recommendations to CMS based on that evidence.”48 Moreover, we included CMS and FDA into our tiering scheme where others have not as we felt that their regulatory and/or cleavage decisions affect the use of these applications.

It might be argued that the Tier 3/Red category contains two qualitatively different subsets that should not be combined: (i) applications with recommendations against use and (ii) applications for which no synthesized evidence in the form of a CPG, an SR, or CMS or FDA information is available. For those who may be interested in conducting additional research and incorporating the latest primary study results into decision making, combining these subsets in the Tier 3/Red category may not be ideal. We have designed the system primarily to benefit an audience of clinicians and public health policy makers interested in implementing genomic applications, or not, on the basis of existing synthesized evidence. For this audience, Tier 3/ Red applications are expected to be of little interest until some supporting synthesized evidence is available.

An acknowledged weakness of our approach is that our classification system is not designed to finely differentiate among guidelines on the basis of quality criteria or rigor because not all guidelines are created equal.47 In addition, the use of different conventions in evaluating evidence and reporting of results among various groups creating SRs and CPGs cannot be corrected for in rough classification systems such as ours. More indepth evaluation is possible using instruments such as AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines, Research, and Evaluation)49,50 and has been done quite effectively to compare genomic guideline products51 and methods.52 Instead, we have focused on the intent and general conclusions of evidence sources (e.g., informing use, choice, and dose) while providing a rough classification involving a few source types (SR, CPG, FDAapproved drug label, and Medicare coverage) that are critical for successful implementation. Because of this, our classification process can generally be completed and updated more quickly than is possible with more detailed instruments.

Another weakness of this and any other summary of evidence is that clinical scenarios may not always be specified or well defined in source documents. Even when clinical scenarios and recommendations are clear, some degree of interpretation, condensation, and/or simplification is necessary when presenting results in tabular form. Critical nuances included in FDA-approved drug labels, CMS determinations, CPGs, and SRs may be missed during the classification process. Our classification method and evolving table are designed to make rough interpretations of the evidence base and point users to the relevant sources of evidence, thus saving time spent searching. Nevertheless, decision makers must actually read the indicated evidence sources in order to effectively apply their findings.

No horizon-scanning system will be perfectly sensitive, and it is a certainty that we have not collected all of the synthesized evidence. There are also enormous challenges associated with maintaining a horizon-scanning system and organizing results, due to the rapidly evolving evidence base in public health genomics. Even as final revisions to this article are being completed, our horizon scans have identified an SR that may have the potential to elevate the Tier 3/Red example used in this article to Tier 2/Yellow.53 We will continue horizon scanning and classification of results on a continuous basis, acknowledging that classifications must be expected to change as evidence develops and evolves. Our system has led to an expanding and evolving table of Genomic Tests and Family History by Levels of Evidence,7 which we hope will prove useful as a rough guide to stakeholders in the field of genomic medicine.

The original impetus for our classification system came from a 3 × 3 risk–benefit policy matrix, risk–benefit profile by level of uncertainty, developed by Veenstra et al.54 Although an enormously useful tool, we sought to develop an approach that did not require formal decision-analytic modeling and resulted in fewer and simpler categories. We hope that our simplified approach will prove useful in helping to shape future studies. Ongoing translational research can be tailored specifically to each of the tier/color classification levels. For applications in Tier 1/Green, research is needed on effective integration of tests into practice, whereas evidence on when to implement assumes increased importance in Tier 2/Yellow scenarios, and accumulating relevant evidence on clinical utility will be needed. A key question for Tier 3/Red scenarios is whether, and in which cases, additional research on validity and utility might be justified. Although our classification system cannot provide detailed answers to these questions, we hope that it will help to identify, organize, and prioritize future research while serving decision makers as a heuristic to guide the beginnings of more detailed assessments of evidence.

Note: While this article was in press, new data were published suggesting that no improvement in anticoagulation control with warfarin resulted from adding genotype to clinical variables in a dosing algorithm (Kimmel et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 19 November 2013, Online First). The results of this original study do not immediately affect placement in our classification scheme but could be integrated into future guidelines or systematic reviews. Rapid progress in the field underscores the need for continuous horizon scanning of the evidence.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Manolio TA, Green ED. Genomics reaches the clinic: from basic discoveries to clinical impact. Cell. 2011;147:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei Y, Xu F, Li P. Technology-driven and evidence-based genomic analysis for integrated pediatric and prenatal genetics evaluation. J Genet Genomics. 2013;40:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans JP, Meslin EM, Marteau TM, Caulfield T. Genomics. Deflating the genomic bubble. Science. 2011;331:861–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1198039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoury MJ, Berg A, Coates R, Evans J, Teutsch SM, Bradley LA. The evidence dilemma in genomic medicine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:1600–1611. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petitti DB, Teutsch SM, Barton MB, Sawaya GF, Ockene JK, DeWitt T U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: insufficient evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:199–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury MJ, Coates RJ, Evans JP. Evidence-based classification of recommendations on use of genomic tests in clinical practice: dealing with insufficient evidence. Genet Med. 2010;12:680–683. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f9ad55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics. [Accessed 14 June 2013];Genomic tests and family history by levels of evidence. < http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/tier.htm>.

- 8.Teutsch SM, et al. EGAPP Working Group. The Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Initiative: methods of the EGAPP Working Group. Genet Med. 2009;11:3–14. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318184137c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddow JE, Palomaki GE. An introduction to assessing genomic screening and diagnostic tests. Nutrition Today. 2011;46:162–168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwinn M, et al. Horizon scanning for new genomic tests. Genet Med. 2011;13:161–165. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182011661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Preventive Services Task Force. [Accessed 14 July 2013]; < http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/>.

- 12.American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. [Accessed 14 July 2013]; < http://www.acmg.net/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home3>.

- 13.Kost GJ. National guideline clearinghouse. Clin Chem. 2000;46:141–142. Www.guideline.gov/index.asp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubinstein WS, et al. The NIH genetic testing registry: a new, centralized database of genetic tests to enable access to comprehensive information and improve transparency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D925–D935. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whirl-Carillo M, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glover J. Searching for the evidence using PubMed. Med Ref Serv Q. 2002;21:57–65. doi: 10.1300/J115v21n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 14 June 2013];Table of pharmacogenomic biomarkers in drug labels. < http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm>.

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 24 July 2013];510(k) Premarket Notification Database. < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm>.

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 24 July 2013];Medicare Coverage Database. < http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/>.

- 20.Agarwal A. Do companion diagnostics make economic sense for drug developers? N Biotechnol. 2012;29:695–708. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 14 June 2013];Companion diagnostic devices: in vitro and imaging tools. < http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/InVitroDiagnostics/ucm301431.htm>.

- 22.Olsen LA, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, editors. IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; Washington, DC: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium of the pharmacogenomics research network. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:464–467. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swen JJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte–an update of guidelines. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:662–673. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swen JJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:781–787. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott SA. Personalizing medicine with clinical pharmacogenetics. Genet Med. 2011;13:987–995. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318238b38c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green RC, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goddard KA, et al. Description and pilot results from a novel method for evaluating return of incidental findings from next-generation sequencing technologies. Genet Med. 2013;15:721–728. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blue Cross Blue Shield Association TEC. KRAS mutations and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allegra CJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2091–2096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Febbo PG, et al. NCCN Task Force report: evaluating the clinical utility of tumor markers in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(suppl 5):S1–32. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0137. quiz S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: can testing of tumor tissue for mutations in EGFR pathway downstream effector genes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer improve health outcomes by guiding decisions regarding anti-EGFR therapy? Genet Med. 2013;15:517–527. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 25 July 2013];Mercaptopurine Labeling Revision (05/27/2011) < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/009053s032lbl.pdf>.

- 34.Relling MV, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and thiopurine dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:387–391. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Relling MV, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and thiopurine dosing: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:324–325. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flockhart DA, et al. ACMG Working Group on Pharmacogenetic Testing of CYP2C9, VKORC1 Alleles for Warfarin Use. Pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 alleles for warfarin. Genet Med. 2008;10:139–150. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318163c35f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClain MR, Palomaki GE, Piper M, Haddow JE. A rapid-ACCE review of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 alleles testing to inform warfarin dosing in adults at elevated risk for thrombotic events to avoid serious bleeding. Genet Med. 2008;10:89–98. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815bf924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 26 July 2013];National Coverage Determination (NCD) for Pharmacogenomic Testing for Warfarin Response (90.1) 2009 < http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=333>. [PubMed]

- 39.Johnson JA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes and warfarin dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:625–629. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Food and Drug Administration. Warfarin Labeling Revision (10/04/2011) 2011 < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/009218s107lbl.pdf>.

- 41.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 30 September 2013];510(k) Substantial Equivalence Determination, Decision Summary, 510(k) number: k042259. < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K042259.pdf>.

- 42.US Food and Drug Administration. Paroxetine Mesylate Labeling Revision (04/28/2011) 2011 < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/021299s024lbl.pdf>.

- 43.Matchar DB, et al. Testing for cytochrome P450 polymorphisms in adults with non-psychotic depression treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;146:1–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thakur M, et al. Review of evidence for genetic testing for CYP450 polymorphisms in management of patients with nonpsychotic depression with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Genet Med. 2007;9:826–835. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31815bf98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: testing for cytochrome P450 polymorphisms in adults with nonpsychotic depression treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Genet Med. 2007;9:819–825. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31815bf9a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg EP, Luce BR. Evidence based? Caveat emptor! Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:80–92. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 25 July 2013];Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee. < http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/FACA/MEDCAC.html>.

- 49.Brouwers MC, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ. 2010;182:1045–1052. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brouwers MC, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182:E472–E478. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simone B, De Feo E, Nicolotti N, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Methodological quality of English-language genetic guidelines on hereditary breast-cancer screening and management: an evaluation using the AGREE instrument. BMC Med. 2012;10:143. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gopalakrishna G, Langendam MW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM. Guidelines for guideline developers: a systematic review of grading systems for medical tests. Implement Sci. 2013;8:78. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altar CA, Hornberger J, Shewade A, Cruz V, Garrison J, Mrazek D. Clinical validity of cytochrome P450 metabolism and serotonin gene variants in psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25:509–533. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.825579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veenstra DL, Roth JA, Garrison LP, Jr, Ramsey SD, Burke W. A formal risk-benefit framework for genomic tests: facilitating the appropriate translation of genomics into clinical practice. Genet Med. 2010;12:686–693. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eff533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 89. Elective and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:231–241. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291580.39618.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology; ACOG Committee on Genetics; Society of Gynecologic Oncologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 103: hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:957–966. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a106d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 77: screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:217–227. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200701000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 78: hemoglobinopathies in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:227–237. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200701000-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hickey SE, Curry CJ, Toriello HV. ACMG Practice Guideline: lack of evidence for MTHFR polymorphism testing. Genet Med. 2013;15:153–156. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: can UGT1A1 genotyping reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with irinotecan? Genet Med. 2009;11:15–20. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818efd9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genet Med. 2009;11:35–41. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fa2ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: can tumor gene expression profiling improve outcomes in patients with breast cancer? Genet Med. 2009;11:66–73. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181928f56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genomic profiling to assess cardiovascular risk to improve cardiovascular health. Genet Med. 2010;12:839–843. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f872c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: routine testing for Factor V Leiden (R506Q) and prothrombin (20210G>A) mutations in adults with a history of idiopathic venous thromboembolism and their adult family members. Genet Med. 2011;13:67–76. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fbe46f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: does genomic profiling to assess type 2 diabetes risk improve health outcomes? Genet Med. 2013;15:612–617. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wierzbicki AS, Humphries SE, Minhas R Guideline Development Group. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1095. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.US Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:355–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hershfield MS, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for human leukocyte antigen-B genotype and allopurinol dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:153–158. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leckband SG, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:324–328. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin MA, Klein TE, Dong BJ, Pirmohamed M, Haas DW, Kroetz DL Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and abacavir dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:734–738. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scott SA, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450-2C19 (CYP2C19) genotype and clopidogrel therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:328–332. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scott SA, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317–323. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed 2 August 2013];About Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs) < http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/who-isinvolved-in-the-effective-health-care-program1/about-evidence-basedpractice-centers-epcs/>.

- 74.The Cochrane Library. [Accessed 29 October 2013];Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. < http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html>.

- 75.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed 2 August 2013];Technology Assessments. < http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/ta/index.html>.