Abstract

Background

Practice guidelines recommend surveillance endoscopy every 2–3 years among patients with Barrett's esophagus (BE) to detect early neoplastic lesions. Although surveys report that > 95% of gastroenterologists recommend or practice BE surveillance, the extent and patterns of surveillance in clinical practice are unknown.

Objective

Identify the extent and determinants of endoscopic surveillance among BE patients.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

121 VA facilities nationwide

Patients

Veteran patients with BE diagnosed during 2003–2009 with follow-up through September 30, 2010.

Interventions

Not an interventional study

Main Outcome Measurements

The proportions of patients with BE who received any EGD after the index BE EGD date. In the subgroup of patients with at least 6 years of follow-up, we also calculated proportions for regular (EGD during both 3-year intervals), irregular (EGD in only 1 interval), and no surveillance. We examined differences in demographics, clinical and facility factors among these groups in unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Results

We identified 29,504 patients with BE; 97% were men, 83% white, and their mean age was 61.8 years. During a 3.8 years median follow-up period, 45.4% of BE patients received at least one EGD. Among the subgroup of 4,499 BE patients who had at least 6 years of follow-up, 23.0% had regular surveillance and 26.7% had irregular surveillance. There was considerable facility-level variation in percentages with surveillance EGD across the 112 facilities and by geographic region of these facilities. Demographic and clinical factors did not explain these variations. Patients with at least one EGD were significantly more likely to be white, younger than 65 with low comorbidity, to have GERD, obesity, dysphagia or esophageal strictures, to have more outpatient visits and to be seen in smaller hospitals (<87 beds) than those without any EGD.

Limitations

Possibility of misclassification of BE and surveillance EGD. Lack of pathology data on dysplasia, which dictates surveillance intervals.

Conclusions

Endoscopic surveillance for BE is considerably less commonly practiced in VA than self-reported by physicians. Although several clinical factors are associated with variations in surveillance, facility-level factors play a large role. The comparative effectiveness of the different practice based surveillance patterns needs to be examined.

Keywords: VA, epidemiology, risk factors, GERD

BACKGROUND

Barrett's esophagus (BE) is the precancerous lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma, which is the fastest rising malignancy in white men in the United States. The prevalence of BE in persons with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who undergo endoscopy is 6 to 13%, and up to 1% of the general adult population (1–3). Once BE is diagnosed, surveillance endoscopy is recommended to detect and treat early neoplastic lesions (i.e. dysplasia or early cancer) through endoscopic or surgical ablation or resection. Current practice guidelines published by the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) recommend surveillance endoscopy every 2–3 years among patients with non dysplastic-BE diagnosis (4); whereas, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends surveillance endoscopy every 3 years (5).

The extent and patterns of endoscopic surveillance among BE patients in clinical practice is unclear. Previous survey-based studies examining physicians’ beliefs and attitudes about surveillance endoscopy found that up to 95% of gastroenterologists recommend or perform BE surveillance (6). However, the actual practice of BE surveillance endoscopy is unclear. There have been no large-scale studies from community or healthcare system settings in the United States documenting the use of surveillance endoscopy among well-defined BE populations.

Examining practice patterns is important to identify gaps in clinical practice where there is under- or over-utilization of endoscopic surveillance compared to clinical practice guidelines; and possible determinants of these gaps including patient-, provider, and facility- factors. These determinants could be used to identify potential targets for better implementation of guideline-concordant surveillance care. In addition, examining BE surveillance practice patterns is essential to test the feasibility of conducting comparative effectiveness studies among these practices using extant clinical practice data.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States. Veteran users of VA Healthcare systems (VHA) are disproportionately older men, and therefore the prevalence of BE is expected to be high.

We conducted this study to examine the frequency and determinants of surveillance endoscopy among patients with BE diagnosed at VA facilities nationwide with special emphasis on identifying practices consistent with AGA’s and ACG’s practice guidelines for BE surveillance.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients with BE using national VA data to examine the patterns and predictors of endoscopic surveillance. The institutional review board at Baylor College of Medicine approved the study protocol.

Data Source

The Veterans Affairs Health Administration (VHA) maintains Medical SAS® Datasets that contain national administrative data for VHA-provided health care utilized primarily by Veterans. These data are extracted from the National Patient Care Database (NPCD), maintained by the VHA Office of Information at the Austin Information Technology Center (AITC), the central repository for VA data. In 1997, the VA started a Medical SAS Outpatient File that contains up to 10 diagnosis codes according to the 9th revision of the International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and up to 20 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for each outpatient encounter. We also utilized the Medical SAS Inpatient File that contains ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes related to each patient’s inpatient stay.

Study Cohort

For this study, we identified a cohort of BE patients with BE recorded in VA outpatient files between October 1, 2003 and September 30, 2009 (Fiscal Years (FY) 2004 to 2009). The diagnosis of BE was ascertained by the presence of ICD-CM-9 code 530.85, combined with at least one EGD test (CPT codes 43200 – 43259, excluding 43246) within 12 months after the BE code date. We chose this observational time period because the ICD-9 code for BE was introduced in early 2003. The closest EGD within 1 year of BE index date was defined as index date of BE diagnosis. The length of follow-up for each patient was calculated from the date of index EGD to the date of last VA inpatient or outpatient encounter or the date of esophageal or gastrointestinal cancer (if any) before September 30, 2010.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We included BE patients defined above who were between the ages of 18 and 90 years old and had at least one year of follow-up after their BE index date. In order to construct a cohort representing patients who were eligible for surveillance, we excluded those with any gastric duodenal or esophageal cancers, abdominal surgery, decompensated liver disease, feeding tube, any metastatic cancer, or any chemotherapy, which were confirmed by the ICD-9 codes being present within 5 years preceding BE index date.

Study Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the receipt of any outpatient or inpatient EGD, as identified by CPT codes (43200 – 43259, excluding 43246) and ICD-9 procedure codes (4223, 4224, 4413, 4414, 4513, 4514, 4516) at least one year after the index date of EGD. Because current AGA and ACG practice guidelines recommend endoscopic surveillance for BE patients every 2–3 years, we examined receipt of EGD in a subgroup of patients with at least 6 years of follow-up (i.e., had two complete 3-year intervals). Regular surveillance was operationally defined by receipt of an EGD during both intervals, and irregular surveillance was defined by receipt of an EGD in only one interval.

We assessed several patient-level variables including GERD and obesity within 5 years preceding BE index date and dysphagia, esophageal stricture or H. pylori infection within one year after the BE index date. GERD was identified by ICD-9 diagnosis codes (530.10, 530.11, 530.12, and 530.81) and a definite GERD diagnosis was defined as the presence of codes in at least one inpatient record or any two outpatient record which were 30 days apart, otherwise a single outpatient code was defined as possible GERD.

We measured the burden of co-existing conditions using the Deyo comorbidity score in the one year before and after the BE index date (7). We also estimated the total number of inpatient and outpatient encounters during follow-up for each patient, and ascertained whether or not the patients lived in rural areas according to zip codes based on home residence at the date of index EGD.

Several facility- level variables were also examined. Every patient was assigned to one VA facility where he/she obtained his/her index BE EGD. Total hospital operating beds and academic affiliation as indicated by the number of resident slots per 10,000 patients in 2003 were determined for each facility. Finally, we classified VA facilities into five regions in the US according to where each facility is located (Midwest, Northeast, South, West, and Puerto Rico/Virgin Islands).

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportions of patients with BE who received any EGD after the index BE date in the entire cohort, and the proportions of receiving regular, irregular and no surveillance EGD among patients who had at least 6 years of follow-up after the BE index date (to have at least two 3-year periods to evaluate AGA and ACG concordant guidelines). We also calculated the proportion of patients with 3 or more EGDs and defined them as “probable overutilizers.” We examined associations of patient, clinical and facility factors with the surveillance status. Chi-square tests were used to examine the association between these categorical factors and receipt of surveillance EGD. We plotted the facility-level proportions of BE patients receiving surveillance EGD (and regular surveillance) in descending order of quintiles; facilities with less than 5 patients with BE and those with no surveillance EGD were excluded from the plot.

A binary logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the predictors for likelihoods of receiving at least one surveillance EGD during follow-up after BE diagnosis. A multinomial logistic regression was used to evaluate the predictors for the likelihoods of receiving regular, irregular, or no surveillance EGD examined as a trichotomous variable among patients with at least 6 years follow-up. A similar logistic regression model was constructed to examine potential predictors of overuse of surveillance EGD (vs. BE patients who received at least one but less than 3 EGDs). Wald tests were used in assessing the significance of predictors respectively. A stepwise regression approach was used to reduce the set of predictor variables included in the final model; only predictor variables that remained significant (P< 0.10) were retained. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each predictor variable.

Sensitivity Analysis

To examine the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses in two subgroups of patients with (1) “continual VA use” defined by having at least one VA inpatient or outpatient encounter during each year of follow-up irrespective of duration of follow-up; and (2) “6 years of follow-up” as defined by having at least one visit per year during each of the successive 6 years after BE index date. In the two subgroups, we calculated the proportions of patients receiving at least one EGD at any time after BE diagnosis and probable overuse of EGD, as well as regular and irregular surveillance EGD in the patients with continual VA use for all 6 years of follow-up. In this third subgroup, we also examined the extent and determinants of probable overuse in a subgroup of patients with “at least one surveillance EGD.”

We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of 29,504 patients with BE met the inclusion and exclusion criteria during FY 2004–09 and were included in this analysis. The patients were seen in 121 VA facilities, mostly in the southern region of the United States (37.0%) followed by Midwest (24.8%) and Western (23.1%) regions. Most BE patients in this cohort were men (96.9%), and there was a large proportion of Caucasians (83.2%). The mean age of BE patients in this cohort was 61.8 years, and 34.5% of these patients were diagnosed at 65 years or older (Table 1). Approximately three quarters had either definite (67.2%) or possible (8.1%) GERD diagnosis during the five years preceding the BE index date, whereas one quarter (24.7%) had no prior GERD diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical determinants of surveillance during a 3.8 year median follow-up after BE diagnosis.

| Variable | Total (N=29,504) n (%) |

At least one EGD after BE diagnosis (n=13,381) n (%) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | |||

| Year of BE Diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||

| 2004 | 6597 (22.3) | 4258 (31.8) | |

| 2005 | 5064 (17.2) | 2908 (21.7) | |

| 2006 | 4766 (16.2) | 2387 (17.8) | |

| 2007 | 4534 (15.4) | 1906 (14.2) | |

| 2008 | 4454 (15.1) | 1273 (9.5) | |

| 2009 | 4089 (13.8) | 649 (5.0) | |

| Age | <0.0001 | ||

| <50 | 3355 (11.4) | 1549 (11.6) | |

| 50–54 | 3362 (11.4) | 1709 (12.8) | |

| 55–59 | 6746 (22.8) | 3364 (25.1) | |

| 60–64 | 5877 (19.9) | 2484 (18.6) | |

| >65 | 10164 (34.5) | 4275 (31.9) | |

| Gender | 0.54 | ||

| Male | 28589 (96.9) | 12975 (97.0) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 24547 (83.2) | 11410 (85.3) | |

| Black | 1191 (4.0) | 485 (3.6) | |

| Hispanic | 551 (1.9) | 224 (1.7) | |

| Other | 320 (1.1) | 141 (1.0) | |

| Missing | 2895 (9.8) | 1121 (8.4) | |

| Rural Zip Code | .87 | ||

| No | 19879 (67.4) | 9009 (67.3) | |

| Yes | 9625 (32.6) | 4372 (2.5) | |

| VA Visits after BE diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||

| MEDIAN | 69 visits | 90 visits | |

| Quartile 1 (1 to 36) | 7237 (24.5) | 1801 (13.5) | |

| Quartile 2 (37 to 68) | 7457 (25.3) | 3176 (23.7) | |

| Quartile 3 (69–124) | 7367 (25.0) | 3795 (28.4) | |

| Quartile 4 (125–2344) | 7443 (25.2) | 4609 (34.4) | |

| Clinical Factors | |||

| GERD (before BE) | <0.0001 | ||

| None | 7273 (24.7) | 2896 (21.6) | |

| Possible | 2409 (8.1) | 1054 (7.9) | |

| Definite | 19822 (67.2) | 9431 (70.5) | |

| Obesity (before BE) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 22769 (77.2) | 10114 (75.6) | |

| Yes | 6735 (22.8) | 3267 (24.4) | |

| Dysphagia (after BE) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 29228 (99.1) | 13301 (99.4) | |

| Yes | 276 (0.9) | 80 (0.6) | |

| Esophageal Stricture (after BE) | 0.0001 | ||

| No | 29072 (98.5) | 13146 (98.2) | |

| Yes | 432 (1.5) | 235 (1.8) | |

| Comorbidity Score | <0.0001 | ||

| 0 | 15171 (51.4) | 7259 (54.3) | |

| 1 | 8403 (28.5) | 3757 (28.1) | |

| 2+ | 5930 (20.1) | 2365 (17.6) | |

| H. pylori | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 791 (2.7) | 328 (2.5) | |

During 114,322 person years of follow-up (median 3.8 years) after BE index date, 45.4% (n= 13, 381) of BE patients received at least one surveillance EGD in 119 VA facilities. Most (61.2%) patients who received any EGD received only one EGD, whereas 24.1% 2 EGDs and 14.7% with 3 or more surveillance EGDs. The first EGD occurred at a median of 1.8 years after BE index date. BE patients who had at least one surveillance EGD after BE diagnosis were significantly more likely to be Caucasian and less than 65 years of age (p<0.0001) compared with patients receiving no surveillance EGD. They were also more likely to have GERD diagnoses, obesity, dysphagia and esophageal strictures and less likely to have high comorbidity score (Deyo 2+) (Table 1).

In the subgroup analysis of 4,499 BE patients who had at least 6 years of follow-up (median 6.5 years), 1034 (23.0%) had regular EGD surveillance and 1202 (26.7%) had irregular surveillance. Compared to the 2263 (50%) patients with no surveillance, similar to the findings of the full sample analyses, patients with GERD, esophageal strictures and having more frequent VA visits were more likely to receive regular surveillance. However, among those who received at least one EGD surveillance, there were no temporal, demographic or clinical differences between the two surveillance groups (regular and irregular); none of the comparisons reached statistical significance at p<0.05 (data not shown). During the first 3 years, 459 (10.2%) patients had 2 or more EGD, and in the second 3 years, 330 (7.3%) had 2 or more EGD.

High number of VA visits (for any reason) was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of receiving surveillance EGD in the total cohort (Table 1) and in the cohort with at least 6 years of follow-up (Table 2). In the multivariable analysis, having a surveillance EGD was strongly associated with the highest quartile of patient visits with an odds ratio of 3.54 (95% CI 3.26–3.85) in the total cohort (Table 4) and also in the group with at least 6 years of follow-up with an odds ratio of 3.50 (95%: 3.19 to 3.85) (data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical patient-level determinants of receiving regular or irregular EGD surveillance after BE diagnosis. The analysis is limited to 4499 BE patients who had at least 6 years of follow-up. Regular surveillance was defined by receipt of at least one EGD in each 3-year follow-up period and irregular surveillance by receipt of at least one EGD in only one 3-year period.

| Variable | None n (%) |

Irregular n (%) |

Regular n (%) |

P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 2263 | 1202 | 1034 | |

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Year of BE Diagnosis | 0.74 | |||

| 2004 | 2172 (96.0) | 1149 (96.0) | 995 (96.0) | |

| 2005 | 91 (4.0) | 53 (4.0) | 39 (4.0) | |

| 2006 | NA | NA | ||

| 2007 | NA | NA | ||

| 2008 | NA | NA | ||

| 2009 | NA | NA | ||

| Age | 0.16 | |||

| <50 | 264 (11.6) | 152 (12.6) | 116 (11.2) | |

| 50–54 | 328 (14.5) | 177 (14.7) | 145 (14.0) | |

| 55–59 | 543 (24.0) | 289 (24.0) | 251 (24.3) | |

| 60–64 | 327 (14.5) | 166 (24.0) | 188 (18.2) | |

| >65 | 801 (35.4) | 418 (34.7) | 334 (32.3) | |

| Gender | 0.62 | |||

| Male | 2205 (97.4) | 1165 (96.9) | 1008 (97.5) | |

| Race | 0.19 | |||

| White | 1961 (86.6) | 1057 (87.9) | 906 (87.6) | |

| Black | 105 (4.6) | 42 (3.5) | 29 (2.8) | |

| Hispanic | 51 (2.3) | 21 (1.8) | 18 (1.7) | |

| Other | 20 (0.9) | 13 (1.1) | 9 (0.9) | |

| Missing | 126 (5.6) | 69 (5.7) | 72 (7.0) | |

| Rural Zip Code | .73 | |||

| No | 1502 (66.4) | 811 (67.5) | 698 (67.5) | |

| Yes | 761 (33.6) | 391 (32.5) | 336 (32.5) | |

| VA Visits after BE diagnosis | <0.01 | |||

| MEDIAN | 113 visits | 141 visits | 138.5 visits | |

| Quartile 1 (1 to 36) | 137 (6.0) | 26 (2.2) | 19 (1.8) | |

| Quartile 2 (37 to 68) | 413 (18.3) | 173 (14.4) | 152 (14.7) | |

| Quartile 3 (69–124) | 709 (31.3) | 312 (25.9) | 285 (27.6) | |

| Quartile 4 (125–2344) | 1004 (44.4) | 691 (57.5) | 578 (55.9) | |

| Clinical Factors | ||||

| GERD before BE | 0.01 | |||

| None | 401 (17.7) | 174 (14.5) | 164 (15.9) | |

| Possible | 185 (8.2) | 104 (8.6) | 59 (5.7) | |

| Definite | 1677 (74.1) | 924 (76.9) | 811 (78.4) | |

| Obesity before BE | 0.69 | |||

| No | 883 (26.4) | 768 (22.9) | ||

| Yes | 319 (27.6) | 266 (23.0) | ||

| Dysphagia (after BE) | NA | |||

| No | 2263 (100.0) | 1202 (100.0) | 1034 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Esophageal Stricture (after BE) | 0.01 | |||

| No | 2226 (98.4) | 1163 (96.8) | 1008 (97.5) | |

| Yes | 37 (1.6) | 39 (3.2) | 26 (2.5) | |

| Comorbidity Score | 0.42 | |||

| 0 | 1276 (56.4) | 672 (56.0) | 599 (58.0) | |

| 1 | 625 (27.6) | 358 (29.7) | 286 (27.6) | |

| 2+ | 362 (16.0) | 172 (14.3) | 149 (14.4) | |

| H. pylori | 0.59 | |||

| Yes | 47 (2.1) | 23 (1.9) | 16 (1.6) | |

Table 4.

Results from Logistic regression models examining the effects of patient characteristics, clinical factors and facility factors on receiving EGD*. NA: not applicable because the variable dropped out of the final model.

| Variable | Any EGD after BE diagnosis | Regular EGD Surveillance |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | ||

| Fiscal Year of BE diagnosis | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| 2004 | Reference | Reference |

| 2005 | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 0.94 (0.63–1.38) |

| 2006 | 0.64 (0.59–0.69) | NA |

| 2007 | 0.53 (0.49–0.58) | NA |

| 2008 | 0.31 (0.28–0.34) | NA |

| 2009 | 0.15 (0.13–0.16) | NA |

| Age | ||

| <50 | Reference | Reference |

| 50–54 | 1.11 (1.0–1.23) | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) |

| 55–59 | 1.09 (1.0–1.19) | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) |

| 60–64 | 1.03 (0.94–1.14) | 1.24 (0.93–1.66) |

| >65 | 0.85 (0.78–0.93) | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) |

| Sex | ||

| Male vs. Female | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) | 1.08 (0.67–1.75) |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 0.80 (0.70–0.91) | 0.57 (0.37–0.88) |

| Hispanic | 0.82 (0.68–1.01) | 0.91 (0.52–1.59) |

| Other | 0.99 (0.78–1.27) | 0.98 (0.44–2.18) |

| Missing | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) | 1.55 (1.13–2.14) |

| Visits (quartiles) | ||

| 1 (1 to 36) | Reference | Reference |

| 2 (37 to 68) | 1.97 (1.83–2.13) | 2.80 (1.67–4.71) |

| 3 (69–124) | 2.59 (2.40–2.80) | 3.21 (1.94–5.33) |

| 4 (125–2344) | 3.54 (3.26–3.85) | 5.14 (3.12–8.49) |

| Clinical Factors | ||

| GERD | ||

| None | Reference | Reference |

| Possible | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 0.79 (0.55–1.12) |

| Definite | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | 1.17 (0.95–1.43) |

| Obesity | ||

| Obese vs. not | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | NA |

| Esophageal stricture | ||

| Present vs. not | NA | 1.43 (0.85–2.40) |

| Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | 0.86 (0.72–1.03) |

| 2+ | 0.64 (0.60–0.69) | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) |

| Facility Factors | ||

| Region | ||

| 1 (Midwest) | Reference | Reference |

| 2 (Northeast) | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) |

| 3 (South) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) |

| 4 (West) | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) |

| 5 (Puerto Rico/Virgin Islands) | 0.67 (0.39–1.13) | NA |

| Total Hospital Operating Beds (quartiles)* | ||

| 1 (<90) | Reference | Reference |

| 2 (90–149) | 0.67 (0.62–0.73) | 0.63 (0.50–0.79) |

| 3 (150–280) | 0.73 (0.67–0.79) | 0.70 (0.56–0.88) |

| 4 (283–450) | 0.64 (0.59–0.70) | 0.73 (0.59–0.91) |

| Academic Affiliation Resident Slots per 10,000 Unique Patients (quartiles) | ||

| 1 (0–7.1) | Reference | Reference |

| 2 (7.6–12.3) | 1.08 (0.99–1.16) | NA |

| 3 (12.7–19.2) | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | NA |

| 4 (19.3–47.3) | 1.13 (1.04–1.23) | NA |

Variables with p-values > 0.1 were not included in the final multivariate models.

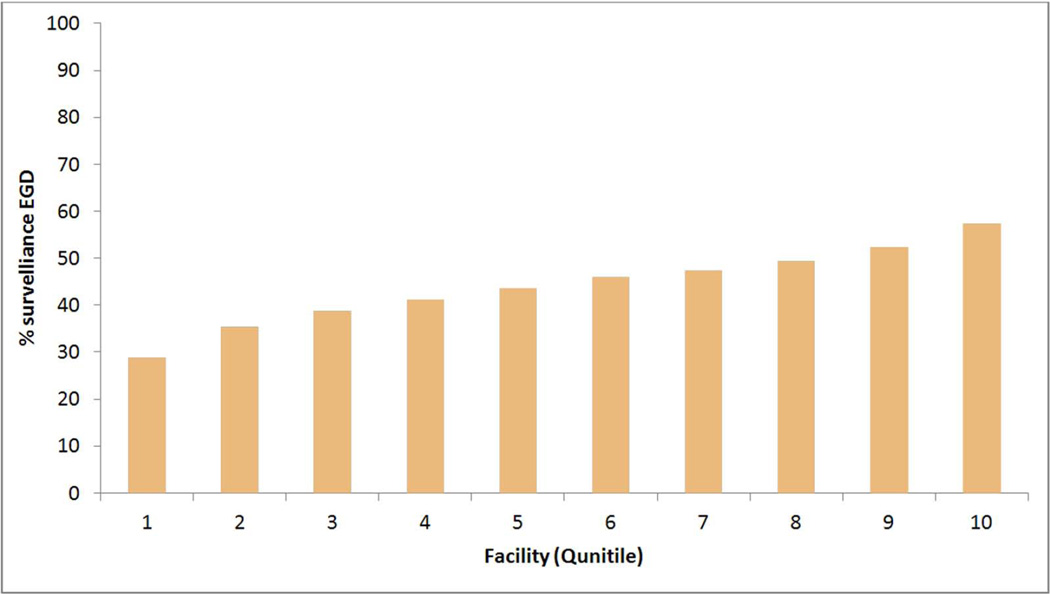

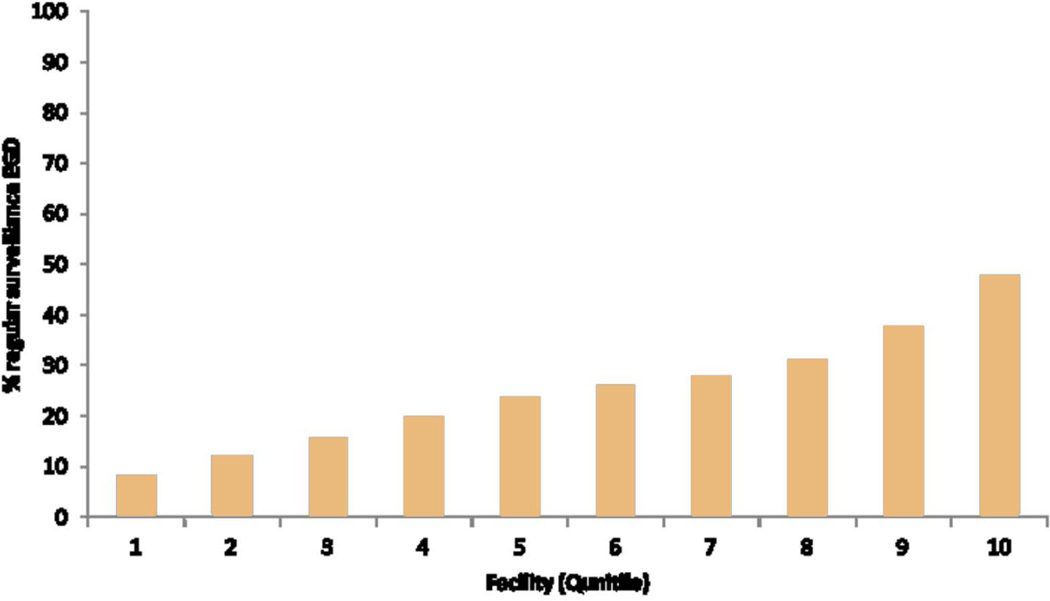

There were significant facility-level variations in the performance of surveillance EGD in the overall cohort across 121 VA facilities (median 45.1%, interquartile range 38.6%- 49.6%) (Figure 1.a) and in performing regular surveillance (median 24.6%, interquartile range 15.2%–31.1%) in the group with at least 6 years follow-up across 106 facilities (Figure 1.b). BE patients seen in VA facilities in the Midwest (47.3%) and Northeastern regions (47.7%) were more likely to receive a surveillance EGD than those in Western (43.1%) or Southern (44.6%) regions (p<0.0001). Patients seen in smaller VA facilities (<87 beds vs. >283 beds) were significantly more likely to have surveillance EGD (Table 3). Although there was an overall association between the number of resident trainees slots in any given facility and receipt of surveillance EGD among BE patients in that facility, there was no discernable trend. In the multivariable analysis, the differences among geographic regions were slightly attenuated but remained significant after adjusting for variations in patient level demographic and clinical factors (data not shown). However, adding the other two facility-level variables of hospital size and academic affiliation to the multivariable model further attenuated the observed association between facility region and receipt of EGD (Table 4). In the group with at least 6 years follow-up, there were only minor differences in the geographic distribution of VA facilities (119 VA facilities) between the regular and irregular surveillance; these differences were not significant in the multivariable model adjusting for demographic, clinical and facility factors (Table 4).

Figure 1.

a. Facility level proportions of patients with BE who received at least one surveillance EGD during follow-up (116 VA facilities). The proportions are arranged in descending order of quintiles. Facilities with <5 BE patients, and those with no surveillance EGD were excluded from the plot.

b. Facility level proportions of patients with regular endoscopic surveillance defined as at least one EGD in each 3-year follow-up period (106 VA facilities). All patients had at least 6 years of follow after BE EGD index date. The proportions are arranged in descending order of quintiles. Facilities with <5 BE patients, and those with no regular EGD were excluded from the plot.

Table 3.

Facility-level potential determinants of EGD surveillance among patients with Barrett's esophagus.

| Variable | Total | At least one EGD after BE diagnosis |

P-Value | Received EGD surveillance during 6 years after BE diagnosis |

P- Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Irregular | Regular | |||||

| Number of patients | 29,504 | 13381 | 2360 | 1202 | 1034 | ||

| Region (%) | <.0001 | .03 | |||||

| 1(Midwest) | 7330(24.8) | 3469 (47.3) | 547 (48.5) | 318 (28.2) | 263 (23.3) | ||

| 2 (Northeast) | 4356 (14.8) | 2077 (47.7) | 296 (46.6) | 169 (26.6) | 170 (26.8) | ||

| 3 (South) | 10908 (37.0) | 4866 (44.6) | 822 (50.7) | 427 (26.3) | 374 (23.0) | ||

| 4 (West) | 6828 (23.1) | 2943 (43.1) | 592 (53.5) | 287 (26.0) | 227 (20.5) | ||

| 5 (Puerto Rico/Virgin Islands) | 82 (0.1) | 23 (31.7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Total Hospital Operating Beds* (%) | <.0001 | .002 | |||||

| Quartile 1 (<90) | 7317 (24.8) | 3596 (17.5) | 462 (45.2) | 286 (28.0) | 274 (26.8) | ||

| Quartile 2 (90–149) | 6856 (23.2) | 3017 (44.0) | 595 (54.0) | 286 (26.0) | 221 (20.0) | ||

| Quartile 3 (150–280) | 7658 (26.0) | 3452 (45.1) | 623 (51.8) | 309 (25.7) | 271 (22.5) | ||

| Quartile 4 (283–450) | 7536 (25.5) | 3292 (43.7) | 583 (49.7) | 321 (27.4) | 268 (22.9) | ||

| Academic Affiliation Resident Slots per 10,000 Unique patients (%) | <.0001 | .12 | |||||

| 1 (0–7.1) | 7136 (24.2) | 3282 (46.0) | 480 (49.3) | 253 (26.0) | 241 (24.7) | ||

| 2 (7.6–12.3) | 7009 (23.8) | 3197 (45.6) | 464 (46.9) | 282 (28.5) | 244 (24.6) | ||

| 3 (12.7–19.2) | 7991 (27.1) | 3538 (44.3) | 680 (52.2) | 340 (26.1) | 282 (21.7) | ||

| 4 (19.3–47.3) | 7231 (24.5) | 3340 (46.2) | 639 (51.8) | 327 (26.5) | 267 (21.7) | ||

Information was not available for 137 patients from New Orleans during 2004

Patients with 3 or more EGDs were defined as probable overutilizers of surveillance EGD. They constituted 1961 (6.7%) of the 29,504 overall cohort, 1653 (6.6%) of the 24,987 cohort with continual VA use, 1961 (14.7%) of 13,381 patients with at least one surveillance EGD, and 720 (20.1%) of the 3576 cohort with at least 6 years of follow-up. The significant determinants of overuse compared with those with at least one but less than 3 surveillance EGDs and (Table 5) included Caucasian race (compared with blacks), highest quartile of number of VA visits, low comorbidity score and attending large VA facilities.

Table 5.

Determinants of potential overutilization of surveillance EGD (defined as 3 more surveillance EGD after index BE EGD).

| Variable | Probable Overutilizer |

Remainder of Cohort |

Adjusted OR ((95% CI) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1961 (14.66%) n (%) |

11,420 (85.34%) n (%) |

|||

| Year of BE Diagnosis | <.0001 | |||

| 2004 | 967 (49.3) | 3291 (28.8) | Reference | |

| 2005 | 485 (24.7) | 2423 (21.2) | .75 | |

| 2006 | 277 (14.1) | 2110 (18.5) | .52 | |

| 2007 | 148 (7.6) | 1758 (15.4) | .38 | |

| 2008 | 73 (3.7) | 1200 (10.5) | .30 | |

| 2009 | 11 (0.6) | 638 (5.6) | .09 | |

| Race | .01 | |||

| White | 1729 (88.2) | 9681 (84.8) | Reference | |

| Black | 54 (2.7) | 431 (3.8) | .65 | |

| Hispanic | 27 (1.4) | 197 (1.7) | .72 | |

| Other | 14 (0.7) | 127 (1.1) | .69 | |

| Missing | 137 (7.0) | 984 (8.6) | 1.19 | |

| VA Visits after BE Diagnosis | <.0001 | |||

| Quartile 1 (1 to 36) | 97 (4.9) | 1704 (14.9) | Reference | |

| Quartile 2 (37 to 68) | 297 (15.2) | 2879 (25.2) | 1.5 | |

| Quartile 3 (69–124) | 532 (27.1) | 3263 (28.6) | 2.22 | |

| Quartile 4 (125–2344) | 1035 (52.8) | 3574 (31.3) | 2.90 | |

| Esophageal Stricture (after BE) | <.0001 | |||

| No | 1889 (96.3) | 11257 (98.6) | Reference | |

| Yes | 72 (3.7) | 163 (1.4) | 2.16 | |

| Comorbidity Score | .03 | |||

| 0 | 1062 (56.2) | 6197 (54.3) | Reference | |

| 1 | 562 (28.6) | 3195 (27.9) | .94 | |

| 2+ | 337 (17.2) | 2028 (17.8) | .82 | |

| Facility Factors | ||||

| Region | .0002 | |||

| 1 | 518 (26.4) | 2951 (25.9) | Reference | |

| 2 | 326 (16.6) | 1751 (15.3) | 1.10 | |

| 3 | 743 (37.9) | 4123 (36.1) | 1.22 | |

| 4 | 371 (18.9) | 2572 (22.5) | .86 | |

| 5 | 3 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) | .90 | |

| Academic Affiliation | <.0001 | |||

| 1 | 457 (23.3) | 2825 (24.7) | Reference | |

| 2 | 420 (21.4) | 2777 (24.3) | .95 | |

| 3 | 601 (30.7) | 2937 (25.7) | 1.37 | |

| 4 | 483 (24.6) | 2857 (25.1) | 1.05 | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 24 (.2) | ||

| Hospital Size | .0001 | |||

| 1 | 516 (26.3) | 3080 (27.0) | Reference | |

| 2 | 414 (21.1) | 2603 (22.8) | .76 | |

| 3 | 474 (24.2) | 2978 (26.1) | .76 | |

| 4 | 557 (28.4) | 2735 (23.9) | .81 | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 24 (0.2) | ||

In sensitivity analyses that included only BE patients with continual VA use (had at least one VA visit during each year of available follow-up), the proportion with at least one surveillance EGD was essentially unchanged (11,123 of 24,987, 44.5%) compared with the main analysis. Having a surveillance EGD was strongly associated with the highest quartile of patient visits with an odds ratio of 3.50 (95%: 3.19 to 3.85) in the multivariable logistic regression models. Similarly, among patients with 6 years of follow-up with at least one VA visit in each of these years, we found 2650 of 3576 (74.1%) to have had at least one surveillance EGD and this was strongly associated with the highest quartile of patient visits with an odds ratio of 3.26 (95% CI 1.81–5.88). In the latter cohort, the proportions of those with regular (877 of 3576, 24.5%) and irregular (957 of 3576, 26.8%) surveillance were similar to those calculated from the overall cohort.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 29,504 newly diagnosed BE patients, surveillance EGD was performed in less than half (45.3%) of these patients during a median follow-up of 3.8 years. In a subgroup of BE patients who had follow-up period of at least 6 years, 23% had regular surveillance as defined by AGA or ACG guidelines, 27% had irregular surveillance, whereas 50% had no surveillance EGD. Both regular follow-up as well as frequency of follow-up were strong predictive factors of receipt of surveillance EGD. Patients who underwent EGD surveillance were generally healthier and younger, more likely Caucasian and had more clinical features of severe GERD than those with no surveillance EGD. Variations in proportions of BE patients undergoing endoscopic surveillance were observed across VA facilities. Other facility factors such as facility bed size and academic affiliation seem to explain a large proportion of the observed geographic differences, with only a small proportions contributed by patient level demographic and clinical factors.

Endoscopic surveillance for BE is considerably less commonly practiced than self-reported by physicians. In this study, less than one in four patients with non-dysplastic BE received AGA or ACG guideline-concordant surveillance EGD. Previous studies that examined surveillance patterns or adherence to practice guidelines among patients with BE have primarily relied on self-reported information (e.g., survey questionnaires) (8–10), however and the validity of self-reported answers is unknown. Studies that examined actual practices relied on single or few centers experience with dedicated BE surveillance programs (11–13), and therefore they have limited generalizability (14–17). These studies often describe overutilization that appears to result from insurance-status or facility associated factors (14). The current study provides a novel description of practice patterns for surveillance EGD among patients with BE in a geographically-diverse, health system sample. Although the possibility of overutilization was present in 6.7% of our total study cohort and in approximately 15% among patients who received at least one surveillance EGD, it remains relatively small compared to non VA studies (14). Our findings in a VA setting where there is no financial incentive for endoscopy present a sharp contrast to prior work demonstrating overutilization of surveillance endoscopy, and underscore the Institute of Medicine’s observation that overuse and underuse can occur simultaneously across the health system (18).

The low rates of BE patients receiving endoscopic surveillance may reflect underutilization of EGD among these patients in VA practice. However, justifiable exclusions that could not be identified in this study (i.e., patient refusal or no-show, EGD performed at a non-VA facility, uncaptured comorbidities, etc.) may also contribute a portion of these low rates. Even if we could be able to account for these unobserved factors, the surveillance rates would still be much lower than those reported by physicians. Similar explanations can be made for the possible over utilization that was observed in smaller proportions. Detailed review of medical records may provide further insight but would be impractical to do manually, given the large size of study cohort. Although some demographic and clinical predictors found in this study to be significantly different between the groups with and without surveillance EGD may not be clinically meaningful because of the very small absolute difference (e.g., age, obesity, H pylori, stricture), the large racial variations indicating that blacks are much less likely to receive an EGD as well as participate in regular surveillance EGD compared with Caucasians brings to light a racial disparity that needs further study.

If surveillance EGD underutilization is truly present, then there is little that is known about the reasons for this observation. We expect that our observational study has unmeasured patient- and provider- behavioral explanations for variation in surveillance practices. For instance, what are the factors that are related to patients’ and physicians’ perceptions of cancer risk, expectations that cancer prevention will reduce risk, clinical heuristics that guide physician decision making and the affective responses to BE diagnosis and surveillance? Explaining these findings requires an understanding of the joint determinants of physicians’ and patients’ behaviors pertaining to surveillance and treatments for BE. To address these questions we are currently conducting qualitative studies with BE patients and treating physicians.

Surveillance EGD may be overestimated in this study because we denoted all EGD after BE index date as “surveillance” endoscopy. Although our exclusion of patients with gastroesophageal cancer, surgery or several severe comorbidities including liver disease from the study cohort would have increased the likelihood of capturing surveillance EGD, some procedures may have been performed for a different purpose. Although the intention of performing endoscopy in a BE patient is quintessential in defining “surveillance” endoscopy, the surveillance benefit (detection of early neoplasia) is likely to be achieved in most elective EGDs irrespective of intention. On the other hand, it is also possible that some patients received additional EGD at non-VA facilities that was not captured by the study, especially after age of 65 when most veterans qualify for Medicare benefits. To examine surveillance rates in patients more consistently using the VA for their healthcare, we conducted a sensitivity analyses in which we examined only BE patients with at least one visit to a VA facility in each year of additional follow-up and it yielded similar results to the main analyses. We also looked at differences in EGD utilization in two groups stratified by age (≥65 years and <65 years old) to estimate the effect of non-VA use when Medicare eligibility starts for most patients. We found only a small absolute difference between the groups: 31.9% at least one EGD in 65 and older vs. 34.5% in the overall group. On balance, we believe that overall our estimates were representative of the VA practice of surveillance EGD during our study period.

An additional limitation of the study includes the potential for misclassification of BE cases using ICD-9 diagnosis codes alone. We previously examined the validity of IC9-codes for BE in VA administrative databases in a review of medical records of 336 patients with BE codes and 337 patients with GERD codes but no BE diagnosed. We showed a moderately high positive predictive value for our algorithm of using a BE code accompanied by an EGD code within 1 year (19). In 79% of cases, a BE diagnosis was found in the medical records based on recorded or reported endoscopic and histological findings. Conversely, the absence of BE code in the presence of EGD was highly predictive of absence of BE in the medical-record review (negative predictive value of 89%). Misclassification of BE by the study definition may also account for a small part of the observed low rate of BE surveillance. If one considers that only 79% of patients in this study had true BE, then the observed receipt of at least surveillance EGD would be 57.4%. Furthermore, given the absence of endoscopy report review, it is unclear how many patients had irregular Z-lines or "ultra" short segment BE, in whom surveillance may not have been indicated. Similarly, GERD diagnosis which was found to be predictive of increased surveillance may indicate the presence of long segment BE which could not be ascertained in the study. The generalizability of this single center chart validation study to other VA facilities is unknown which may require further validations in future studies.

The study has several strengths including the unprecedented sample size of 29,504 BE patients seen among 121 facilities. We also limited the study cohort to those with a high likelihood of using VA healthcare (those with at least one visit and at least one year of follow-up after BE diagnosis). The relatively long follow-up (3.8 years) overall and exceptionally long follow-up (6.1 years) for a subgroup of patients as well as the chart validation of the BE definition are additional strengths.

One of the potential advantages of defining endoscopic surveillance practice patterns of BE in this study is to facilitate future comparative effectiveness studies. Existing studies examining the effectiveness of surveillance EGD are either retrospective population-based studies in which patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma were examined for the presence of pre-diagnosis endoscopy. These studies are limited because they do not examine the population-at risk (i.e., BE), or are small studies of BE patients with relatively short follow-up and very few cancer cases. Although providing information on the possible role of endoscopy in affecting the outcomes of cancer, these studies did not address the frequency or yield in the BE population at risk. In our study, we identified two large groups of approximately equal numbers who had regular or irregular surveillance among patients with at least 6 years of follow-up after BE index date. These groups had no relevant differences in their demographic or clinical features, and could be examined in future studies for comparative effectiveness of surveillance endoscopy.

In summary, this study provides a novel description of practice patterns of surveillance EGD among patients with newly recorded BE, and the patient- level as well as facility-level potential determinants of practice variations. The findings also indicate the feasibility of comparative effectiveness studies of endoscopic BE surveillance using the VA BE patient population, and the need for greater understanding of patient and provider related determinants of BE surveillance.

Acknowledgement

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-020), and by NIH grant RC4CA155844 awarded to Dr. El-Serag and the Texas Digestive Disease Center NIH DK58338.

Abbreviations

- BE

Barrett's esophagus

- EA

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- VA

Veterans Administration

- VHA

Veterans Affairs Health Administration

- EGD

endoscopy

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest exist for Drs. El-Serag, Kramer, Chen, Duan, Shakhatreh, Hinojosa-Lindsey, Hou, Naik, or Street.

References

- 1.Westhoff B, Brotze S, Weston A, et al. The frequency of Barrett's esophagus in high-risk patients with chronic GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:226–231. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin M, Gerson LB, Lascar R, et al. Features of gastroesophageal reflux disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1442–1447. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084–1091. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross CP, Canto MI, Hixson J, et al. Management of Barrett's esophagus: a national study of practice patterns and their cost implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3440–3447. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amamra N, Touzet S, Colin C, et al. Current practice compared with the international guidelines: endoscopic surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:789–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Sandick JW, Bartelsman JF, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Surveillance of Barrett's oesophagus: physicians' practices and review of current guidelines. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandal A, Playford RJ, Wicks AC. Current practice in surveillance strategy for patients with Barrett's oesophagus in the UK. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1319–1324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramus JR, Gatenby PA, Caygill CP, et al. Surveillance of Barrett's columnar-lined oesophagus in the UK: endoscopic intervals and frequency of detection of dysplasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:636–641. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832183bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Switzer-Taylor V, Schlup M, Lubcke R, et al. Barrett's esophagus: a retrospective analysis of 13 years surveillance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1362–1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gladman L, Chapman W, Iqbal TH, et al. Barrett's oesophagus: an audit of surveillance over a 17-year period. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:271–276. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crockett SD, Lipkus IM, Bright SD, et al. Overutilization of endoscopic surveillance in nondysplastic Barrett's esophagus: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harewood GC, Rathore O, Patchett S, et al. Assessment of adherence to published surveillance guidelines--opportunity to enhance efficiency of endoscopic practice. Ir Med J. 2008;101:248–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruijshaar ME, Kerkhof M, Siersema PD, et al. The burden of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2006;38:873–878. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bampton PA, Schloithe A, Bull J, et al. Improving surveillance for Barrett's oesophagus. BMJ. 2006;332:1320–1323. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Research Council. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. Front Matter. 1-4-2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Serag HB, Wieman M, Richardson P. The use of acid-decreasing medication in veteran patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder with and without Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1293–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]