Abstract

Mammary carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor in women, and it is the leading cause of mortality, with an incidence of >1,000,000 cases occurring worldwide annually. It is one of the most common human neoplasms, accounting for approximately one-quarter of all cancers in females worldwide and 27% of cancers in developed countries with a Western lifestyle. They exhibit a wide scope of morphological features, different immunohistochemical profiles, and unique histopathological subtypes that have specific clinical course and outcome. Breast cancers can be classified into distinct subgroups based on similarities in the gene expression profiles and molecular classification.

Keywords: breast cancer, histological variant of breast carcinoma, molecular classification, invasive ductal carcinoma, lobular carcinoma

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common human neoplasms, accounting for approximately one-quarter of all cancers in females worldwide and 27% of cancers in developed countries with a Western lifestyle.1 Breast cancer can also occur in men, but it is more than 100 times more common in women than in men. It usually has bad prognosis due to delays in diagnosis.2

Breast cancer occurs in any of the cells of the mammary gland and exhibits a wide scope of morphological features, different immunohistochemical profiles, and unique histopathological subtypes that have specific clinical course and outcome. Breast carcinomas are the most common malignant lesion, although different types of sarcomas and lymphomas can also be encountered. Nowadays, with the wide use of mammography as a screening tool, more cases of preinvasive breast lesions are detected. The WHO Working Group agreed that more clinical follow-ups and genetic data are needed for a better understanding of the natural history of these lesions.3

Breast Carcinoma

Most of the breast malignancies are adenocarcinomas, which constitute more than 95% of breast cancers.4 Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is the most common form of invasive breast cancer. It accounts for 55% of breast cancer incidence upon diagnosis.5 Breast carcinomas arise from the same segment of the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU). The typing of invasive breast carcinoma and its histological variants is well established. In general, breast carcinoma is divided into ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and IDC. DCIS is a noninvasive potentially malignant intraductal proliferation of epithelial cells that is confined to the ducts and lobules. Invasive or infiltrative carcinoma refers to malignant abnormal proliferation of neoplastic cells in the breast tissue, which has penetrated through the duct wall into stroma. Invasive carcinoma and carcinoma in situ were classified as ductal and lobular based on the site from which the tumor originated. Cancers originating from the ducts are known as ductal carcinomas, while those originating from the lobules are known as lobular carcinomas. However, it is now found that this sort of tumor growth variation is not related to the site or the cell of origin, but there could be differences in tumor cell biology: whether the tumor cells express E-cadherin or not.4

Microscopic Types

Breast carcinoma is usually classified primarily by its histological appearance, originating from the inner lining epithelium of the ducts or the lobules that supply the ducts with milk. For the morphological study of breast carcinoma, two main questions should be answered: is the tumor limited to the epithelial component of the breast (in situ carcinoma) or has invaded the stroma to become invasive carcinoma and does the tumor arise from the duct (ductal carcinoma) or from the lobule (lobular carcinoma)? Both tumor types arise from the same segment of the mammary gland, TDLU. For diagnostic purposes, in daily histopathological practice, the cytoarchitectural features should be used to determine the tumor to be ductal or lobular, rather than its precise location within the breast tissue.6

Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

It is a neoplastic proliferation of epithelial cells limited to the ducts or lobules, characterized by cellular and nuclear atypia, potential malignant capacity, and obligate and nonobligate tendencies to develop subsequent invasive breast cancer.1 The myoepithelial cells of the outer ductal layer are usually preserved but may be attenuated or decreased in number. The spread of DCIS throughout the ducts into the lobular acini producing extensive lesions is called lobular cancerization.4

DCIS is considered a precursor lesion for the subsequent development of invasive carcinoma with a high-risk index factor than that expected in women without DCIS. Since 1983, a tremendous increase in the detection of these lesions has been achieved with the widespread use of screening mammography and increasing awareness of breast cancer in the general population.3 Death due to DCIS is extremely rare, but death occurring after initial diagnosis of DCIS is either because of undetected invasive component or due to recurrence of invasive lesion after the treatment.1

Morphological types of DCIS

Historically, DCIS has been divided into five architectural subtypes:

comedo,

solid,

cribriform,

papillary, and

micropapillary.

Some cases of DCIS have a single growth pattern, but the majority shows a mixture of patterns.4

A minority of DCIS lesion shows rarely additional morphologic variations, which include signet ring cells, neuroendocrine differentiation or multinucleated giant cells,7 apocrine metaplastic cells,8 and squamous features (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) in cases.9

Grades of DCIS

Currently, there is no universal consensus on the classification and grading of DCIS. Most modern systems use nuclear grade alone or in combination with necrosis and/or cell polarization. Depending primarily on the degree of nuclear atypia, intraluminal necrosis, and, to a lesser extent, mitotic activity and calcification, DCIS is generally divided into three types1:

Low-grade DCIS is composed of small, monomorphic cells growing in arcades, micropapillae, cribriform, or solid patterns. The nuclei are of uniform size and have a regular chromatin pattern with inconspicuous nucleoli, and mitotic figures are rare (Table 1).

Intermediate-grade DCIS is composed of cells that are cytologically similar to those of low-grade DCIS, forming solid, micropapillary patterns but with some ducts containing intraluminal necrosis. Other intermediate-grade DCISs display nuclei with occasional nucleoli and coarse chromatin; necrosis may or may not be present.3

High-grade DCIS lesion is usually larger than 2 mm, but a duct of any size with the typical morphological features is sufficient for diagnosis. It consists of one layer of highly atypical cells, forming micropapillae, cribriform, or solid patterns. Nuclei are of high grade, markedly pleomorphic, with irregular contour and prominent nucleoli. Mitotic figures are usually common, but their presence is not required. Generally, comedo necrosis is characteristically surrounded by a solid proliferation of large pleomorphic tumor cells. However, intraluminal necrosis is not obligatory. Even a single layer of highly anaplastic cells lining the duct in a flat fashion is sufficient.3

Table 1.

Minimal criteria for low-grade DCIS.

| Cytological Features |

| 1. Monotonous, uniform round cells population |

| 2. Subtle increase in nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio |

| 3. Equidistant or highly organized nuclear distribution |

| 4. Round nuclei |

| 5. Hyperchromasia may or may not present |

| Architecture Features |

| Arcades, cribriform, solid and or micropapillary pattern |

From Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (Eds.): WHO Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2003.

Evolution of DCIS

The natural history of DCIS seems to be quite different depending on its grade and type. The risk of developing invasive carcinoma is directly proportional to the grade of the DCIS. Untreated lesions will inevitably progress to an invasive carcinoma, but the transformation of pure DCIS to an invasive phenotype is not obligatory, and when it takes place, the process extends for many years or decades.6

According to the finding of Farabegoli et al, DCIS is a possible but not an obligate precursor of invasive breast cancer, which suggests that pure DCIS and DCIS associated with IDC may be genetically distinct. The evolution from DCIS to IDC may follow multiple pathways and not a linear model.10

Lobular Carcinoma in Situ

It is the intralobular proliferation of small, fairly uniform, and loosely cohesive cells, originating in the TDLU, with or without pagetoid involvement of terminal ducts. Long-term follow-up for the women with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) concluded that it constitutes a risk factor and a nonobligatory precursor for the subsequent development of invasive carcinoma.3 It has no distinguishing features on gross examination and is usually found incidentally in breast specimen or biopsy performed for other reasons. It is multicentric in about 70% of cases and bilateral in approximately 30%–40% of cases.6

Microscopically, LCIS generally leaves the underlying architecture intact and is recognizable as lobules; there are a relatively uniform population of round, small-to-medium-sized cells that have normochromatic nuclei filling the distended lobules in a noncohesive pattern. Atypical changes such as pleomorphism, mitosis, and necrosis are absent or rarely present. Intracellular mucin droplets are commonly seen sometimes with signet ring nuclei.11,12

There are two immunohistochemical markers to distinguish LCIS, the lack of E-cadherin and β-catenin expressions and the positivity for high molecular weight (HMW) keratin.13 In addition to a specific expression of CK8-18, which shows a distinctive perinuclear expression pattern, while it stains the peripheral cytoplasm of the ductal cells14? On the contrary, DCIS is consistently positive for E-cadherin and β-catenin and shows a reduced or no HMW keratin, which is normally expressed in the ductal basal cell layer, with typical peripheral CK8–18 expression. Aberrant expression of these markers is not uncommon, and some of the cases with intermediate features also show hybrid immunohistochemical features. The loss of E-cadherin in LCIS is due to gene mutations.6

Prognosis and Predictive Factors of LCIS

LCIS constitutes a risk factor and a nonobligate precursor for subsequent development of invasive carcinoma. Invasive carcinoma develops in 25%–35% (about 1% per year) of patients observed for more than 20 years.4 The relative risk of subsequent development of invasive carcinoma among patients with LCIS ranges from 6.9 to 12 times than that in women without LCIS. Retrospective studies of 1,174 women having LCIS and treated by excision biopsy alone reported that 181 (15.4%) developed subsequent invasive carcinoma with almost equal risk of both.3 Both the types of breast carcinomas, ductal or lobular, arise from LCIS.1 The current recommended management for LCIS is, therefore, a lifelong follow-up with or without tamoxifen treatment.6

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

Invasive ductal carcinomas are breast cancers having malignant ductal proliferation along with stromal invasion in the presence or absence of DCIS, apart from their relative proportion.

The appearance of the invasive component should be determined from the subtypes of IDC rather than from the types of DCIS or its grade. IDC is classified into many histological subtypes according to a wide range of criteria, including cell type (as in apocrine carcinoma), amount, type and location of secretion (as in mucinous carcinoma), architectural features (as in papillary, tubular, and micropapillary carcinoma),6 and immunohistochemical profile (as in neuroendocrine carcinoma).

IDCs are a heterogenous group of tumors classified according to cytoarchitectural features, as they have wide scope of morphological variation. Some of them have enough distinctive features and particular behavior to be classified as special subtypes, while the majority, which constitute about 75% of IDC, fail to exhibit sufficient morphological features to be classified as specific histological types and are generally designated as IDC not otherwise specified (NOS). Also a few others prefer to use “no special type” (NST) to emphasize the distinction from specific-type tumors, which is internationally accepted.1

Classic IDC NST

IDC no specific type (NST) is the most common type of IDC that constitutes about 40%–75% of all mammary invasive carcinomas in the published series.15 IDC NST is implied when we use the term breast carcinoma. It is usually present with a wide scope of morphological variation and clinical behaviors, such as tumor size, grade, relative proportion of tumor cell and stroma, and types of margins. The tumor shows a heterogenous type of growth, including diffuse sheets, nests, cords, or singly distributed cells with variable amount of ductal differentiation. The amount of ductal differentiation ranges from more than 70% of tumor tissue to complete absence. Tumor cells are pleomorphic, vary in shape and size, and are usually with prominent nucleoli and numerous mitoses. The areas of necrosis and calcification can be detected in 60% of cases. Foci of squamous metaplasia, apocrine metaplasia, or clear cell changes are sometimes present. The amount of stroma is variable, ranging from none to abundant.6

Tubular carcinoma

Tubular carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, distinct, special type of breast carcinoma with an excellent prognosis, constituting about 2% of IDC in published series. Tubular carcinoma is more common in elderly women and is less likely to have lymph node metastasis. Sometimes, there is a concomitant occurrence of potentially premalignant epithelial proliferative breast lesions such as DCIS, LCIS, and flat epithelia atypia.3

Microscopically, it is characterized by the proliferation of angulated, oval, or elongated tubules with haphazard arrangement and has open lumina lined by a single layer of epithelium without supporting the outer layer of myoepithelial cell and basement membrane, with multifocal invasion of the stroma and fat at the periphery of the tumor.6 About 10%–20% of the patients have been found to have multifocal (multicentric) tubular carcinomas growing as separate foci in one or more quadrants.15

When the tumor has areas of invasive lobular and tubular carcinoma in different proportions, it is referred to as tubulolobular carcinoma; multifocality is more frequent in tubulolobular carcinoma than in pure tubular carcinoma.16

Metastases to axillary lymph nodes occur in approximately 10% of cases; sometimes, areas of a tubular carcinoma and IDC NST are present. The prognosis of these mixed tumors is substantially worse than that of pure tubular carcinoma.6

Invasive cribriform carcinoma

Invasive cribriform carcinoma is a special, rare type of breast carcinoma associated with favorable prognosis. It is more likely to occur in older patients, aged 53–58 years, constituting about 0.8%–3.5% of breast cancer patients.6

Microscopically, there are islands of uniform tumor cells with low-grade atypia that have a cribriform appearance similar to that seen in cribriform DCIS, but there is a clear-cut stromal invasion. Minor areas of tubular differentiation are seen in 25% of cases; the concomitant DCIS component is usually of cribriform or micropapillary type. Well-differentiated mixed cribriform–tubular carcinoma is applicable whenever combined growth patterns of cribriform and tubular carcinoma are seen.15

Mucinous carcinoma

Mucinous carcinoma is a rare, special subtype of breast carcinoma associated with good prognosis, it is a disease of elderly patient, over 60 years, and usually occurs in postmenopausal women. It accounts for only 2% of total breast carcinomas. Other terms that are used to identify this tumor include gelatinous carcinoma, colloid carcinoma, mucous carcinoma, and mucoid carcinoma.6 The classical pure mucinous carcinomas have been described as tumors that have no nonmucinous infiltrating duct carcinoma but extracellular mucin constituting at least 33% of the lesion and mucinous differentiation constituting not less than 90% of the tumor tissue.1

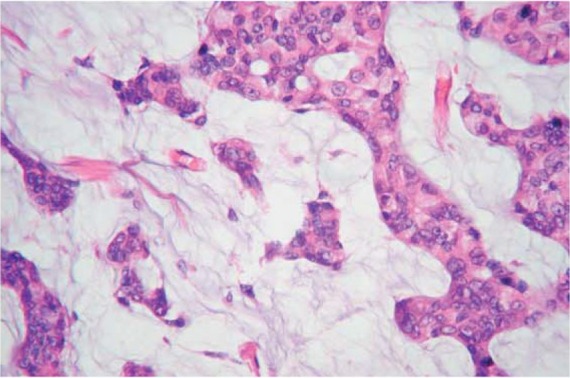

Microscopically, the tumors comprising small clusters of uniform epithelial tumor cells with mild nuclear atypia float in abundant mucus as shown in Figure 1. These cell clusters are arranged as solid, acinar, or micropapillary structures. The mucin is almost entirely extracellular.6

Figure 1.

Mucinous carcinoma. Epithelial cells with mild atypia floating in abundant extracellular mucin.

Other mucin-producing carcinomas of the breast include a variety of carcinomas that are characterized by the production of abundant extracellular and/or intracellular mucin.

Among these are mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, columnar cell mucinous carcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma. The histopathological criteria of mucin-producing carcinomas are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mucin-producing breast carcinoma.

| HISTOLOGICAL TYPE | LOCATION OF MUCIN | GROWTH PATTERN | IN SITU COMPONENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mucoid (colloid) carcinoma | Extracellular | Clusters of cells in mucin lakes | Ductal |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | Intracellular and extracellular | Large cyst, columnar cells, papillae, solid area | Ductal |

| Columnar mucinous carcinoma | Intracellular | Round and convoluted glands lined by single columnar cells | Ductal |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | Intracellular | Isolated cells, cords or clusters | Mainly lobular |

Medullary carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma (MC) is a rare, special subtype of breast cancer presented by a well-defined tumor mass and anaplastic morphology; nonetheless, it has favorable prognosis and better outcome than the common IDC. It affects women about 50 years of age. It is particularly common in carriers of BRCA1 mutations.17 It accounts for less than 5% of mammary carcinomas in most series, but frequency as high as 7% has also been reported.16 The gross appearance can easily be mistaken for a fibroadenoma, but it lacks the trabeculation of fibroadenoma and has a homogenous cut surface. Small foci of necrosis can also be present.6

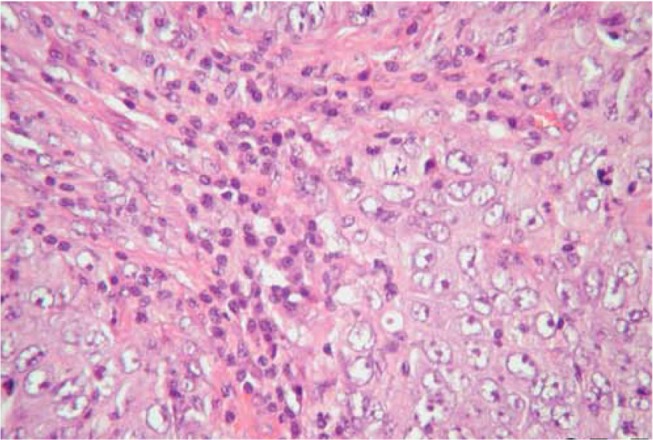

Microscopically, MC is a “well-circumscribed carcinoma composed of poorly differentiated cells with scanty stroma and prominent lymphoid infiltration” and the borders are always of the pushing type. The pattern of growth is diffuse; meanwhile, there should be no glandular differentiation, DCIS lesion, or mucin secretion. The tumor cells are large and pleomorphic with indistinct cellular border, forming syncytial pattern of growth with numerous mitoses and large nuclei having prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2). Other commonly seen features include spindle cell metaplasia, bizzare tumor giant cell, and necrosis. A cardinal microscopic feature is diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate involving the tumor substance and the periphery of the tumor. The lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate represents a reaction of the host tissues to the neoplasm. Axillary lymph node metastases are common.6

Figure 2.

MC. A syncytial sheet of tumor cells separated by abundant lymphoplasmacytic cells.

Invasive papillary carcinoma

Invasive papillar carcinoma is a very rare subtype of breast carcinoma with better prognosis than classic IDC, mostly affecting the postmenopausal women and is more common among white women. It comprises less than 1%–2% of invasive breast cancers.6 Most papillary carcinomas of the breast are predominantly intraductal lesions. The invasive papillary carcinoma should have a predominantly papillary morphology not less than 90% in the invasive component. The invasive nonpapillary carcinoma associated with papillary intraductal lesions should not be considered as invasive papillary carcinoma but should be classified according to the type of invasive component. According to the recent WHO classification of breast tumors, the malignant intraductal papillary lesions include three entities such as intraductal papillary carcinoma, encapsulated papillary carcinoma, and solid papillary carcinoma.1

Microscopically, the invasive elements are showing predominantly papillary architecture, the papillae formed by malignant cells are having mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia with delicate fibrovascular core devoid of myoepithelial cells. Papillary DCIS can be seen in more than 70% of cases.15

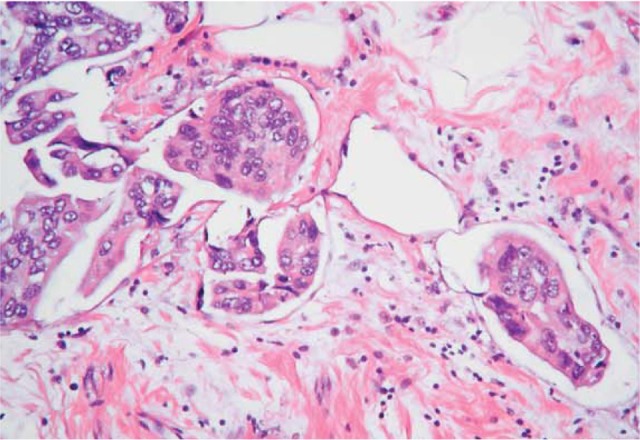

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma of breast is histologically characterized by the growth of cohesive tumor cell clusters within prominent clear stromal spaces, resembling dilated angiolymphatic vessels. Its growth pattern may be a manifestation of aggressive behavior as shown by frequent skin invasion and extensive nodal involvement. However, clinicopathologic features and outcome of invasive micropapillary carcinoma are not strongly dependent on the relative amount of micropapillary component.18 The recognition of invasive micropapillary carcinoma as a special subtype of IDC with distinct prognostic behavior is a relatively recent event. It accounts for only 2% of all invasive breast cancers; meanwhile, micropapillary differentiation is seen in about 3%–6% of conventional IDC. Age incidence is similar to that of classical IDC NST.6 It has a poor clinical outcome and a lower survival rate compared to conventional IDC. It has a high incidence of local recurrence, and lymph node metastasis is a common feature and seen in 70% of cases.19 Microscopically, its morphological and microscopic features are closely similar to micropapillary carcinoma of endometrium, ovary, and bladder. There is an aggregate of small epithelial clusters arranged in pseudopapillary structures lacking a fibrovascular core, free floating in clear empty spaces or hollow resemble lymphovascular spaces, and some of them really are lymphatic spaces (Fig. 3). The tumor cells display a characteristic feature of reverse polarity (inside–out pattern), whereby the apical pole of the neoplastic cells faces the stromal hollow rather than the inner lumen ductal space.1

Figure 3.

Micropapillary carcinoma. Aggregate of tumor cells in empty space with an inside–out arrangement.

Apocrine carcinoma

Apocrine carcinoma is a rare variant of breast carcinoma, accounting for 1%–4% of all cases of breast cancer, with prominent apocrine differentiation comprising not less than 90% of cancer cells. Apocrine carcinomas are often of high grade with bad prognosis. However, the survival rate does not differ from other high-grade tumors with a different designation.15 It is likely that some apocrine carcinomas arise from metaplastic apocrine epithelium coexisting with benign proliferative breast lesion rather than de novo.16

Microscopically, the tumor cells are large having an abundant acidophilic, granular cytoplasm, positive for Periodic Acid Schiff staining (PAS). The nuclei are vesicular with prominent nucleolus.6 Bizarre tumor cells with multilobulated nuclei may also be present. Glandular differentiation is usually found; noninvasive apocrine DCIS component with high nuclear grade is a common finding.15

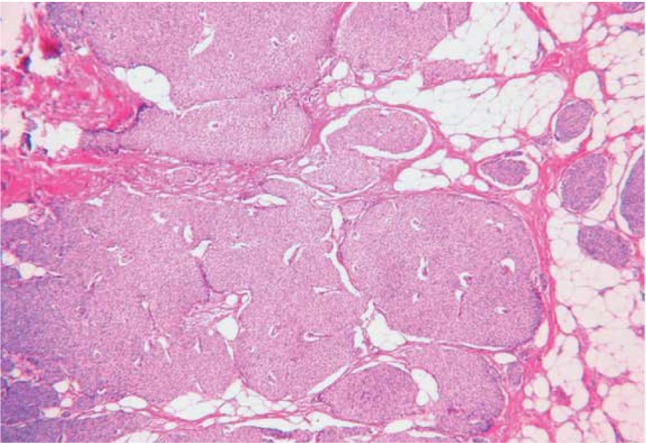

Neuroendocrine tumor

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast is a rare, special subtype of breast cancer representing about 2% of breast carcinoma. It exhibits morphological and immunohistochemical features similar to those of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) of both gastrointestinal tract and lung and has more than 50% of tumor cells that express the neuroendocrine markers. Conventional invasive breast carcinoma NOS and some special variant exhibiting focal neuroendocrine differentiation are not uncommon features. It is more common in postmenopausal women.3

Microscopically, there is an infiltrative growth pattern with solid aggregates of tumor cells arranged in alveolar, nest, trabecular, and rosette patterns with a tendency to make peripheral palisading (Fig. 4). The neoplastic cells are of different cell morphology and are round cells, spindle cells, or small cells. The tumor cells often show a salt-and-pepper chromatin pattern and fine granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm.15

Figure 4.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma with an alveolar pattern of distribution.

According to the 2012 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast, NET can be classified histologically into three distinct subtypes:

NET, well differentiated.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma, poorly differentiated/small cell carcinoma.

Invasive breast carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation.

Histological grading is one of the most important prognostic parameters. Neuroendocrine breast carcinomas may be graded using modified Bloom–Richardson–Elston grading system that is based on classical grading criteria, which is applied to grade classical IDC NST, since there is no specific grading guideline for NET.1 This tumor subtype consistently expresses chromogranin A and synaptophysin markers, which are mandatory to settle the final diagnosis of neuroendocine tumor.

Metaplastic carcinoma

Metaplastic carcinoma is an aggressive invasive beast carcinoma, characterized by the dominant component of metaplastic differentiation (squamous, spindle, and mesenchymal). It represents less than 1% of all invasive breast carcinomas. It affects postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years, and in it, metastases to axillary nodes are relatively uncommon. Metaplastic carcinomas can be classified into several subtypes according to the type and amount of metaplastic tissue of the tumor as shown in Table 3.3

Table 3.

Classification of metaplastic carcinoma.

| Purely epithelial |

| Squamous |

| Large cell keratinizing |

| Spindle cell |

| Acantholytic |

| Adenocarcinoma with spindle cell differentiation |

| Adenosquamous, including mucoepidermoid |

| Mixed epithelial and Mesenchymal (specify components) |

| Carcinoma with chondroid metaplasia |

| Carcinoma with osseous metaplasia |

| Carcinosarcoma (specify components) |

Microscopically, the precise cell type that gives rise to metaplastic carcinoma remains uncertain.16 The common histological pattern of metaplastic carcinoma is a typical IDC component combining with dominant metaplastic tissue, including squamous cells with or without spindle cells differentiation, or mesenchymal differentiation such as chondroid, osseous, and myoepithelial differentiation. Myoepithelial carcinoma (malignant myoepithelioma) represents the same entity as sarcomatoid (metaplastic) carcinoma with myoepithelial differentiation.15

Lipid-rich carcinoma

Lipid-rich carcinoma is a very rare, special subtype of mammary carcinoma, with an incidence of less than 1%–1.6%, in which a vast majority (90%) of neoplastic cells contain abundant cytoplasmic neutral lipids. It covers a wide range of ages from 33 to 81 years.1 At present, it is uncertain to consider lipid-rich carcinoma as an aggressive tumor.3

Microscopically, the tumor cells infiltrates the stroma with ductal or lobular growth pattern, and the tumor cells having foamy or vacuolated cytoplasm contain abundant intracytoplasmic neutral fat demonstrated by oil red O-stain. The tumor cells usually show uniform round to oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli.15

Secretory carcinoma (juvenile carcinoma)

Secretory carcinoma is a very rare, low-grade mammary carcinoma that represents less than 0.15% of all breast cancers. It has a wide scope of age occurrence from childhood, adolescent, and elderly women. It carries a good prognosis when affecting children and adults and has more aggressive course in elderly women.3

Microscopically, the tumor consists of cells with pale pink cytoplasm and a small nuclei characterized by three different architectural patterns of growth, a microcystic or honeycombed pattern composed of small cysts, a tubular pattern containing luminal secretions, and a solid pattern with abundant intracellular and extracellular eosinophilic secretory materials and numerous cytoplasmic lumina.15 Cytoplasmic vacuolization suggests a diagnosis of secretory carcinoma in an Fine Needle Aspirate (FNA) cytology specimen. Signet ring cell forms can be present.16

Oncocytic carcinoma

This is very rare variant of breast cancer as occasional cases has been reported, since some cases misdiagnosed as apocrine carcinoma. The mean age of occurrence is 66 years. The oncocytic cells constitute more than 70% of tumor cells in order to designate the tumor as an oncocytic subtype.3 The oncocytic cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm due to high number of mitochondria. Oncocytic carcinoma shows a solid sheet of large cells having abundant granular, strongly eosinophilic cytoplasm with pleomorphic nuclei having prominent nucleolus and well-defined cell borders.1

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a very rare variant of mammary carcinoma with low-grade malignant lesion associated with favorable prognosis. It accounts for 0.1% of all breast cancers. It has histological features similar to its salivary counterparts.3 The incidence age is between 25 and 80 years, but it occurs more frequently after menopause.16 Axillary node metastases have been reported. Distant metastases occur in about 10% of cases, and the lung is the most common site.20

Microscopically, the tumor cells consisting of epithelial and myoepithelial cell types arrange in three basic patterns: tubular, cribriform, and solid. The tumor cells are characteristically arranged into two types of structures: true glandular spaces, lined by epithelial tumor cells and containing PAS-diastase-positive mucin. Pseudolumina, surrounded by myoepithelial cells, results from the invagination of the stroma; sometimes, the pseudolamina are filled by small spherules or cylinders of hyaline material. A third type of cell is occasionally seen in some of the cases consisting of sebaceous elements that can occasionally be numerous.1

Acinic cell carcinoma

Acinic cell carcinoma is a very rare, special subtype of breast carcinoma affecting women between 35 and 80 years (mean 56 years). It has histological features similar to its salivary counterparts.3

Microscopically, histological features are variable depending on the grade of the tumor. A combination of microglandular, microcystic, and solid areas is common, and areas of comedo-like necrosis can be seen. The tumor cells are large having abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, and the granules are coarse and red similar to those of Paneth cells. The cells are bland with round-to-ovoid nuclei.15

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second major biologically distinct invasive mammary carcinoma other than IDC. It constitutes 5%–15% of invasive breast carcinoma and usually affects older age group women affected by conventional IDC.1 ILC tumor cells are typically round, small, relatively uniform, and noncohesive and have characteristic growth pattern with single-file infiltration of the stroma. The diagnosis of ILC can be made in the presence of these cytoarchitectural features even in the absence of in situ component. On the contrary, an invasive tumor cannot be designated as ILC because it is associated with LCIS; rather, it should have the typical microscopic features of the invasive component.6 The incidence of ILC appears to be increasing, particularly in postmenopausal women, and this finding may, at least partly, be related to hormone replacement treatment.3 Inactivations of E-cadherin by mutation, loss of heterozygosity, or methylation are characteristic molecular changes in ILC, particularly the pleomorphic subtype.21 ILC has five distinct histological variants.

Classic type

The classic type of ILC expresses the typical cytoarchitectural features of ILC; typically, the presence of small uniform tumor cells distributed singly in the stroma, forming Indian file pattern and surrounded by the lobules in a concentric (targetoid) pattern. Foci of stromal elastosis around ducts and veins with disparate lymphoctic infiltrate are commonly seen. Glandular differentiation is not a feature of this variant.6

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma consists entirely or in part of cells larger than the cells in classical ILC with relatively abundant, eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nucleus is hyperchromatic and eccentric with prominent nucleolus;16 meanwhile, this variant has the same pattern of growth as classic ILC but commonly shows focal signet ring cells and apocrine differentiation.6 This variant usually has negative hormonal receptor expression with higher expression of P53 and HER2/neu.22

Histiocytoid carcinoma

Histiocytoid lobular carcinoma entirely consists of large tumor cells arranged in a diffuse pattern of growth. The tumor cells are large with foamy cytoplasm containing abundant granules. In most cases, E-cadherin is negative.6

Signet ring carcinoma

Signet ring ILC usually shows cytoarchitectural features of classic ILC combined with significant number of signet ring cells with eccentric, semilunar nuclei and transparent cytoplasmic vacuoles.16 It is important to differentiate this variant from mucinous carcinoma with signet ring features because of their different prognoses.

Tubulolobular carcinoma

Tubulolobular carcinoma is a variant of ILC characterized by dual expression of both small tubular formations with or without lumen and singly growing cells forming linear pattern of classic ILC. The in situ component is usually present. It is mostly ductal or lobular, but sometimes both of them can be seen.6

Molecular Classification

In the last decade, many efforts have been concentrated to supplement the morphological classification of breast carcinoma with molecular parameters that can provide a clearer appreciation for the heterogeneity of breast cancer and for better prediction of tumor behavior to improve therapeutic strategies. Perou et al classified breast cancers into distinct subgroups based on similarities in the gene expression profiles using the microarray technology.23 This new approach has been accepted by the medical and scientific community with the hope that this new classification, which later updated into molecular classification, will provide new insights into the biology of breast cancers and would affect the therapeutic approach of breast cancers. Some investigators have predicted that the microarray technique will rule, while conventional pathologic assessment will no longer be of use.6 The translation of molecular approaches into clinical daily practice to support morphological features and immunohistochemical profile is critical; moreover, it is fraught with difficulties.24 The subtypes of breast cancers recognized by their gene signature are as follows.

Luminal A

Luminal A accounts for 50% of invasive breast cancers. It is ER/PR positive or HER2 negative. It includes a wide range of low-grade variants, such as tubular carcinoma, cribriform carcinoma, low-grade IDC NST, and classic lobular carcinoma and usually expresses low molecular weight cytokeratins, which highlight the luminal ductal cells, with high expression of hormone receptors and associated genes. It has a good prognosis and is typically of low grade and ER positive.6

Luminal B

This category comprises 20% of invasive breast cancers. The ER/PR is positive, while HER2/neu expression is variable (positive or negative). The proliferation index rate expressed by Ki-67 and histological grades are higher than luminal A. It includes most of grade 2 IDC NST and micropapillary carcinoma. The expression of the low-molecular weight cytokeratins of the luminal epithelial cells is a rule, with moderate-to-weak expression of hormone receptors and associated genes. The response to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy is variable, and its prognosis is poorer than luminal A.6

HER2 overexpression

This group accounts for 15% of all invasive breast cancers. The ER/PR is usually negative, while by definition, HER2/neu is strong positive. The Ki-67 expression is high and TP53 mutation is common. These tumors are more likely to be of high grade and having lymph node metastasis. Their gene signature shows high expression of HER2 and low expression of ER and associated genes.6 This group of breast cancer implies poor prognosis and shows the highest sensitivity to trastuzumab (herceptin) therapy.

Basal like

The basal class is so named due to its pattern of expression that is similar to basal epithelial cells and normal myoepithelial cells of mammary tissue. It is typically CK5/6 and/or EGFR positive, ER/PR negative, and HER2 negative (triple negative),25 with a high expression of Ki-67 index and TP53 mutation, which is common. It comprises about 15% of all invasive breast cancers. The gene expression patterns include high expression of basal epithelial genes, positive for basal cytokeratins; low expression of ER and associated genes; and low expression of HER2/neu.6 Most of high-grade invasive cancers and other distinct low-grade special subtypes of IDC with good prognosis, which expressed low proliferation index rate of Ki-67, such as medullary, adenoid cystic, and secretory carcinoma, are also included in this group. It has no response to endocrine therapy or trastuzumab but appears to be sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy and poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. It has generally poor prognosis (but not uniformly poor).26,27

Currently, there are many trails to use a panel of antibodies to assign breast tumors to the various molecular subtypes (Table 4). These antibodies include ER, PR, HER2/neu, cytokeratin 5/6, EGFR, and Ki-67. Discordance is not uncommon, and currently, there are no widely agreed criteria to define a positive immunostain for this purpose.6

Table 4.

Immunohistochemical profile for the molecular subtypes of breast cancer.

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMMUNOPROFILE | LUMINAL A | LUMINAL B | HER2/NEU | BASAL-LIKE |

| ER, PR | ER and/or PR+ | ER and/or PR+ | ER−, PR− | ER−, PR− |

| HER2 and others | HER2−Low Ki-67 (<14%) | HER2+ or HER2− Ki-67 = 14% or more | HER2+ | HER2− CK5/6 and/or EGFR+ |

Conclusion

Mammary carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor in women, and it is the leading cause of mortality with an incidence of >1,000,000 cases occurring worldwide annually. Carcinoma of the breast is a truly complex disease with a large intertumoral and intratumoral heterogeneity, leading to markedly variable clinical course and response to treatment modalities. There are only a few data that have explained the heterogeneity of cells within a tumor; in general, this feature is not fully understood.28

Breast cancers are classified according to the histological features or molecular characteristics of the tumor. Each of them influences the outcome and response to the treatment. The description of a breast cancer optimally includes all of these factors.

Most breast carcinomas are derived from the epithelium lining of the ducts or lobules; accordingly, they are classified as ductal or lobular carcinoma.

The current molecular classification of breast cancers still has many drawbacks. The basal-like subtype is highly heterogeneous. Although most of the tumors included in this category are of high grade with bad prognosis, low-grade tumors with good prognosis also belong to this group, such as MC, secretory carcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma. It is important to subgroup this category into a low-grade and a high-grade category of basal-like carcinoma.6

Nowadays, in our daily clinical pathology practice, the clinical value of assigning invasive breast cancers beyond routine histologic type, histologic grade, and ER/PR/HER2 status has not been established. The translation of molecular approaches into clinical daily practice to support morphological features and immunohistochemical profile is critical; moreover, it is fraught with difficulties.24

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Dama Laxminarayana, Editor in Chief

PEER REVIEW: Nine peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 927 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: Author discloses no external funding sources.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Author discloses no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) Provenance: the author was invited to submit this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceived the concepts: JM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: JM. Developed the structure and arguments for the paper: JM. Made critical revisions: JM. The author reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, Tan PH, Van de Vijver MJ, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Fourth ed. IARC; Lyon: 2012. ISBN.13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peter B, Bernard L. World Cancer Report. International Agency for Research on Cancer; WHO Press; Lyon, France: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fattaneh AT, Peter D. WHO Classification Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinay K, Abul KA, Jon CA, Nelson F. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Eight ed. Elsevier; Lyon, France: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eheman CR, Shaw KM, Ryerson AB, Miller JW, Ajani UA, White MC. The changing incidence of in situ and invasive ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1763–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology. Tenth ed. Elsevier; Lyon, France: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne JD. DCIS and LCIS with multinucleated giant cells – a report of 4 cases. Histopathology. 2007;50:669–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leal C, Rui H, Paula M, et al. Apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: histologic classification and expression of biologic markers. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:487–93. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.24327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes MM, Peterse JL, Yavuz E, Vischer GH, Eusebi V. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the breast: a light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of a previously undescribed lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1414–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31803d15dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farabegoli F, Champeme MH, Bieche I, Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Derenzini M. Genetic pathways in the evolution of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. J Pathol. 2002;196:280–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanby AM, Hughes TA. In situ and invasive lobular neoplasia of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnitt SJ, Morrow M. Lobular carcinoma in situ. current concepts and controversies. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1999;16:209–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastracci TL, Tjan S, Bane AL, O’Malley FP, Andrulis IL. E-cadherin alterations in atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:741–51. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tien Y, Carolyn M. Application of immunohistochemistry to breast lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:349–58. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-349-AOITBL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farid M. Essentials of Diagnostic Breast Pathology, Practical Approach. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen PP. Rosen’s Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Lyon, France: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armes JE, Venter DJ. The pathology of inherited breast cancer. Pathology. 2002;34:309–14. doi: 10.1080/00313020220147113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hind N, Tracy W, Aleodor A, Jyotirmoy D, Volkan A, Daniel V. Clinicopathologic analysis of invasive micropapillary. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:836–41. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yerushalmi R, Hayes MM, Gelmon KA. Breast carcinoma – rare types: review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1763–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colome MI, Ro JY, Ayala AG. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the kidney. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1996;4:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cristofanilli M, Gonzalez-Angulo A, Sneige N, et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma classic type: response to primary chemotherapy and survival outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:41–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YY, Hwang ES, Roy R, et al. Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1683–94. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b18a89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peter S, Lakhani SR. Recent developments in the molecular pathology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2009;98:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shawarby MA, Al-Tamimi DM, Ahmed A. Molecular classification of breast cancer: an overview with emphasis on ethnic variations and future perspectives. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2013;1:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnitt SJ. Will molecular classification replace traditional breast pathology? Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:162S–6. doi: 10.1177/1066896910370771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correa Geyer F Reis-Filho JS. Microarray-based gene expression profiling as a clinical tool for breast cancer management: are we there yet? Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:285–302. doi: 10.1177/1066896908328577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makki J, Myint O, Wynn AA, Samsudin AT, John DV. Expression distribution of cancer stem cells, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and telomerase activity in breast cancer and their association with clinicopathologic characteristics. Clin Med Insights Pathol. 2015;8:1–16. doi: 10.4137/CPath.S19615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]