Abstract

Lipids are used as cellular building blocks and condensed energy stores and also act as signaling molecules. The glycerolipid/ fatty acid cycle, encompassing lipolysis and lipogenesis, generates many lipid signals. Reliable procedures are not available for measuring activities of several lipolytic enzymes for the purposes of drug screening, and this resulted in questionable selectivity of various known lipase inhibitors. We now describe simple assays for lipolytic enzymes, including adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), hormone sensitive lipase (HSL), sn-1-diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL), monoacylglycerol lipase, α/β-hydrolase domain 6, and carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) using recombinant human and mouse enzymes either in cell extracts or using purified enzymes. We observed that many of the reported inhibitors lack specificity. Thus, Cay10499 (HSL inhibitor) and RHC20867 (DAGL inhibitor) also inhibit other lipases. Marked differences in the inhibitor sensitivities of human ATGL and HSL compared with the corresponding mouse enzymes was noticed. Thus, ATGListatin inhibited mouse ATGL but not human ATGL, and the HSL inhibitors WWL11 and Compound 13f were effective against mouse enzyme but much less potent against human enzyme. Many of these lipase inhibitors also inhibited human CES1. Results describe reliable assays for measuring lipase activities that are amenable for drug screening and also caution about the specificity of the many earlier described lipase inhibitors.

Keywords: adipose triglyceride lipase, alpha/beta hydrolase domain 6, hormone sensitive lipase, diacylglycerol lipase, monoacylglycerol lipase, fatty acid amide hydrolase

Hydrolysis of glycerolipids generates FFAs for further usage as a source of energy. Besides FFA production, lipolysis is also an important source of several metabolic signals. As an integral part of the glycerolipid/fatty acid cycle (1), lipolysis produces lipid signals that modify cellular functions such as glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (2) and metabolic pathways and also alter transcription of various genes (1, 3). TG breakdown to glycerol and fatty acids is accomplished by the sequential action of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), which hydrolyzes TG to 2,3- or 1,3-diacylglycerol (DAG), followed by hormone sensitive lipase (HSL)-mediated DAG hydrolysis to generate 1- or 2-monoacylglycerol (MAG) (1, 3). Finally MAG is hydrolyzed by either the classical MAG lipase (MAGL) or the recently described α/β-hydrolase domain 6 (ABHD6) to glycerol and FFA (4–6). Receptor-mediated signaling at the plasma membrane leads to the phospholipase-C-dependent formation of 1,2-DAG, which is further hydrolyzed by sn-1-DAG lipases (DAGL) α or β (7), to form mostly 2-MAG.

Recent studies indicated the physiological importance of many of these lipases. Thus, ATGL has been implicated in lipid homeostasis in adipocytes, myocardium and skeletal muscle, cancer cachexia (1, 3, 8), and the regulation of insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells (9). HSL was shown to be important in adipose lipid metabolism (10) and in the regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (11, 12). MAGL, which hydrolyzes the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol, has been implicated in the control of pain mechanisms (13) and cancer cell proliferation (14). DAGL enzymes have been found to be important in the production of 2-arachidonoylglycerol and in the control of appetite and pain (15) and also in the regulation of Ca2+ influx into cells (16). We recently showed that 1-MAG is a coupling factor linking glucose metabolism to insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells and that ABHD6 specifically controls β-cell 1-MAG levels (4).

Various compounds have been used to inhibit particular lipolytic enzymes, assuming that the inhibitor is specific. However, no systematic studies have been done comparing the specificity of many of these inhibitor compounds and whether their effectiveness differs among species. These issues make a significant impact on our understanding of lipid metabolism in different organisms and also on the discovery of drugs targeting these enzymes for a possible use against human diseases. It is necessary to have reliable assay procedures to measure the activity of an enzyme before embarking on identifying its physiological role and also for the development of drugs targeting the particular enzyme.

In the present study, we describe reliable assays of lipolytic enzymes using recombinant human and mouse enzymes either in cell extracts or using purified enzymes. Our findings reveal that some of the inhibitors available commercially as “specific” against a particular enzyme are in fact not specific and also that certain inhibitors discovered using rodent enzymes are ineffective against their human counterparts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Purified carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) and RHC80267 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Purified human HSL (hHSL), human MAGL (hMAGL), Cay10499, WWL70, JZL184, JZL195, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor screening assay kit (#10005196) and 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). ThioGlo-1 was from Covalent Associates (Corvallis, OR). ATGL inhibitors ATGListatin (17) and WWL64, HSL inhibitors WWL11 (18) and Compound 13f (19), DAGL inhibitors KT109 and KT172, and ABHD6 inhibitor KT195 (20) were synthesized according to the published procedures. All stock solutions of inhibitors were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide and diluted in assay medium at required concentrations just prior to assays. Plasmids for the expression of human ABHD6 (hABHD6) (pCMV6-AC; SC320252), human ATGL (hATGL) (pCMV6-XL5; SC107379), mouse ATGL (pCMV6; MC210442), hHSL (pCMV6-XL5; SC303624), mouse HSL (pCMV6; MC200824), and human DAGLα (hDAGLα) (pCMV6-XL5; SC101029) were obtained from OriGene (Rockville, MD). All other chemicals used were of the highest purity available. Fluorescence and absorbance were measured using the FLUOstar Optima reader (BMG, Ortenberg, Germany). Antibodies against hATGL and hHSL were from Cell Signaling, anti-DAGLα antibody was from AbNova, and anti-tubulin antibody was from Abcam. Anti-ABHD6 antibody was a gift from Dr. J. Mark Brown (Cleveland, OH). Secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz and BioRad.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose, 4 mM l-glutamine without sodium pyruvate (HyClone, Logan, UT), supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). For lipase expression, 9 × 105 cells were cultured overnight in a 10 cm Petri dish and then transfected with 20 μg of lipase expression plasmids using 20 μl of lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 3 ml of Opti-MEM media (Invitrogen) and 10 ml of above DMEM. After 24 h, transfection medium was replaced by DMEM. Cells were harvested 72 h posttransfection in the corresponding lysis buffers described below, for different lipases after two washes in PBS.

ATGL assay

Human and mouse ATGL were expressed separately in 293T cells. Cell extracts were prepared in 1 ml of buffer A (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 2% DMSO, 0.1% Triton X-100), by three cycles of freeze (in liquid nitrogen)/thaw sonication at high power in a cup horn sonicator (Misonix Sonicator 3000; Qsonica LLC, CT) for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used as the source of ATGL after measuring protein concentration. Aliquots containing 2–4 µg/µl of proteins were stored at −80°C. ATGL expression was verified by Western blotting using antibodies against human (Cell Signaling #2138) or mouse ATGL (Cell Signaling #2439). ATGL activity was assayed using EnzChek lipase substrate (Life Technologies) (21). Control cell extracts prepared from empty vector-transfected cells were used to ascertain that the lipase activity measured is due to the overexpressed ATGL. Assays were performed in 96-well opaque black plates (Corning #3915) containing 30 μg of ATGL cell extract in 90 μl of buffer A, to which 5 μl of test inhibitor (diluted in 30% DMSO to appropriate working stock concentrations to achieve different inhibitor concentrations) was added to give the required final concentration. After 30 min preincubation at room temperature with 700 rpm orbital shaking, 5 µl of 20 μM EnzChek lipase substrate working solution was added to each well to a final concentration of 1 µM to start the reaction at 37°C. EnzChek lipase substrate stock solution (1 mM) was prepared in DMSO and then diluted 1:50 in buffer A, just before use. Final concentration of DMSO was kept at 5% (v/v) in all the wells. Fluorescence (excitation 485 nm; emission 510 nm) was recorded every 30 s for 60 to 90 min with 2 s of shaking preceding each reading. ATGL activity was calculated by subtracting background activity (no enzyme added), using the linear portion of the velocity curve, after the first 15 min of the reaction. Endogenous ATGL activity in extracts prepared from non- or empty vector-transfected cells was found to be low and did not contribute significantly to the activity measured with ATGL enzyme extracts.

HSL assay

Human and mouse HSL proteins were expressed separately in 293T cells. Cell extracts were prepared in PBS as described above for ATGL. Human and mouse HSL expression was verified using HSL antibody (Cell Signaling #4107) in Western blots. Alternatively, we also tested commercially available purified hHSL for some assays. The assay conditions were similar to those described below for ABHD6, except that potassium phosphate buffer was adjusted to pH 7.0 and 1 µg cell extract/well was used. Because HSL is capable of hydrolyzing 1-MAG, we used 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol as the substrate and measured the release of thioglycerol at 37°C using ThioGlo-1 (see ABHD6 Assay below for more details).

sn-1-DAGL assay

DAGLα could not be expressed using the plasmid pCMV6-XL5-hDAGLα from OriGene in 293T cells. The DAGLα cDNA harbors relatively long 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs; 104 and 2,570 bp, respectively). In addition, the 5′ UTR has several out of frame ATG start sites. We observed a similar expression problem when using adenoviral vector with the same DAGLα cDNA. We realized that the 5′ UTR interfered with protein expression. Thus, we have used a PCR-based strategy to remove both 5′ and 3′ UTRs, keeping only the coding sequence and the natural ATG start site. The coding sequence (3,129 bp long) from the pCMV6-XL5-hDAGLα was amplified by PCR using DAGL forward primer 5′ CAT CTA GAG CCA TGC TGC CCG GGA TCG TGG T and the reverse primer 5′ CAC TCG AGC TAG CGT GCT GAG ATG ACC A. The amplified product was purified and subcloned into pIRES2-EGFP (enhanced green fluorescence protein) plasmid (Clontech). DNA sequencing was performed to confirm in frame ligation of the construct. The plasmid pIRES2-DAGLα thus generated was used to transfect 293T cells, and cell extracts were prepared in 300 µl of 0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 (buffer B). To this end, cells were lysed by three rapid cycles of freeze/thaw/sonication 2 min (10 s on/off cycles) at high power in ice-cold water in a cup horn sonicator, and the extract was centrifuged at 51,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The membrane pellet was suspended in 200 µl buffer B by sonication, and the protein content was measured. Aliquots containing 2–5 µg/µl of protein were stored at −80°C. DAGLα expression was verified using hDAGLα antibody (Abnova #PAB11515) in Western blots. DAGLα activity was assayed by following the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenylbutyrate (pNPB), as described earlier (22). Endogenous DAGLα activity in extracts prepared from pIRES2-EGFP-transfected cells was found to be low and did not contribute significantly to the activity measured with DAGLα enzyme extracts. The assay system premix in a 96-well black plate with clear bottom (PerkinElmer Viewplate-96 F TC), in a volume of 90 μl per well, contained 0.25 M sucrose, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 (buffer C), and 10 μg DAGLα enzyme (cell membranes) extract to which 5 μl of test inhibitor (diluted in 30% DMSO) was added. After 10 min preincubation at room temperature with 700 rpm orbital mixing and 20 min incubation at 37°C with mild shaking, 5 µl of freshly prepared 7.88 mM pNPB (in 70% DMSO in buffer C) was added to each well to start the reaction. The plates were shaken rapidly, and change in absorbance at 405 nm was measured every 30 s for 45 min. DAGLα activity was calculated by subtracting background activity (wells without enzyme extract) using the linear portion of the velocity curve. The final concentration of DMSO was adjusted to 5% in all wells. Activity was also measured using membrane extracts prepared from EGFP-expressing cells and was found to be negligible.

DAGLα was also assayed using EnzChek lipase substrate described above for the ATGL assay. The assay system in a 96-well black plate was similar to the one used with pNPB above. However, reactions were started with 5 µl of 100 μM EnzChek lipase substrate solution to a final concentration of 5 µM. In parallel wells, CaCl2 was added at 5 mM final concentration. Enzyme was preincubated with 6 μM KT109 DAGL inhibitor where indicated, prior to substrate addition. Fluorescence was recorded as described for the ATGL assay above.

MAGL assay

hMAGL was assayed using purified recombinant enzyme (Cayman Chemical). The assay conditions were similar to those described below for ABHD6 with potassium phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 7.4 and an enzyme dilution of 1:7,500 in potassium phosphate buffer. Final concentration of MAGL enzyme protein in the assay was 0.025 ng per well. 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol was used as the substrate, and the release of thioglycerol at 37°C was measured with ThioGlo-1 (see below).

ABHD6 assay

hABHD6 was expressed in 293T cells by transfecting with pCMV6-AC-hABHD6 plasmid. Cell extracts were prepared in PBS as described above for ATGL. ABHD6 expression was verified using ABHD6 antibody (kindly provided by Dr. J. Mark Brown, Cleveland, OH) in Western blots. Aliquots containing 4 µg/µl of protein were stored at −80°C. ABHD6 assay was based on the hydrolysis of 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol to release 1-thioglycerol, which spontaneously reacts with ThioGlo-1 to form a fluorescent adduct (23). Assays were performed in 96-well opaque black plates containing 90 µl of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 and 5 µl of test inhibitor in 30% DMSO. The plates were then preincubated for 30 min at room temperature, after which 5 µl of premixed 100 µM 1-S-arachidonolythioglycerol and 0.26 mM ThioGlo-1 in 20% DMSO was added to all but the gain and background wells. These wells received the ThioGlo-1 only. The plates were immediately placed in the plate reader at 37°C and shaken for 10 s, and fluorescence was continuously recorded at excitation 380 nm and emission 510 nm for 45 min at 30 s intervals. Sensitivity of the detection was adjusted via modifying photomultiplier tube gain from wells containing 1 µM thioglycerol only. Final DMSO concentration in all wells was kept at 2% (v/v). Another control to measure endogenous ABHD6 activity was also set up using cell extract prepared from empty vector-transfected 293T cells. Activity was calculated from the linear portion of the curve after background correction.

In order to compare the overall sensitivity of ABHD6 assays using the artificial substrate 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol and the natural substrate 1-palmitoylglycerol, extracts from hABHD6-overexpressing 293T cells were used, and extracts from untransfected 293T cells were used as control. The assay system in a final volume of 100 μl contained 10 µg protein of extracts, 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.2, without or with 5 μM WWL70 and either 5 µM 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol or 5 or 50 µM 1-palmitoylglycerol. Assay with 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol was described above. Incubations with 1-palmitoylglycerol were at 37°C for 30 min with constant mixing. Reactions were terminated by 5 µl 70% perchloric acid, and after complete mixing, pH was brought to 5–7 using 2 M KOH. Tubes were kept on ice 30 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g. Supernatants were processed for measuring glycerol, released during hydrolysis of 1-palmitoylglycerol, by radiometric method (24).

CES1 assay

Purified human CES1 (hCES1) was used to assay CES1 activity. The assay conditions were similar to those described above for ABHD6, with potassium phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 7.5 and an enzyme concentration of 60 ng/well purified hCES1. 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol was used as a substrate, and the release of thioglycerol at 37°C was measured with ThioGlo-1. CES1 shows robust activity with many carboxyl esters including 1-MAG.

FAAH assay

Assay was performed using the FAAH inhibitor screening assay kit from Cayman Chemicals according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Release of the fluorescent product, 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC), from the hydrolysis of AMC-arachidonoyl amide, mediated by FAAH at 37°C, was recorded using a plate reader with an excitation filter of 340–360 nm and an emission filter of 450–465 nm. Inhibitors were preincubated for 30 min at indicated concentrations with the enzyme prior to the addition of substrate to initiate the reaction. Change in fluorescence with time was taken as enzyme activity and the extent of inhibition was calculated from the initial rates. Positive control for FAAH inhibition was used using JZL195. Final DMSO concentration was kept at 2% (v/v) in the assay.

Data analysis

Percentage of inhibition was calculated from lipase activity at initial rates measured using enzyme extracts treated with the inhibitors relative to the activity measured with vehicle-treated extracts. IC50 values were determined using Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) based on percentage of inhibition values. Results shown represent two to three separate experiments with triplicate observations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Simplified assays for ATGL, HSL, MAGL, ABHD6, and CES1

Lipases are important in the metabolism of various lipids and thus play a critical role in the cell from membranogenesis to the generation of several signaling molecules. Several assays have been described before for different lipase enzymes, but many of them are cumbersome and use radioactive or custom-made substrates not available to all investigators. We have developed simplified and reliable assays of different lipases using recombinant human and mouse enzymes either in the form of cell extracts or purified enzymes. Even though the assays described here cannot be used directly for measuring the corresponding endogenous enzyme activities as many lipases have overlapping substrate specificities, they are adaptable for high-throughput screening of larger libraries of compounds. They may also be adapted for measuring endogenous lipase activity in case a highly specific inhibitor is available to distinguish its activity from other lipases. As we describe below, many such “specific” inhibitors previously described are indeed not specific.

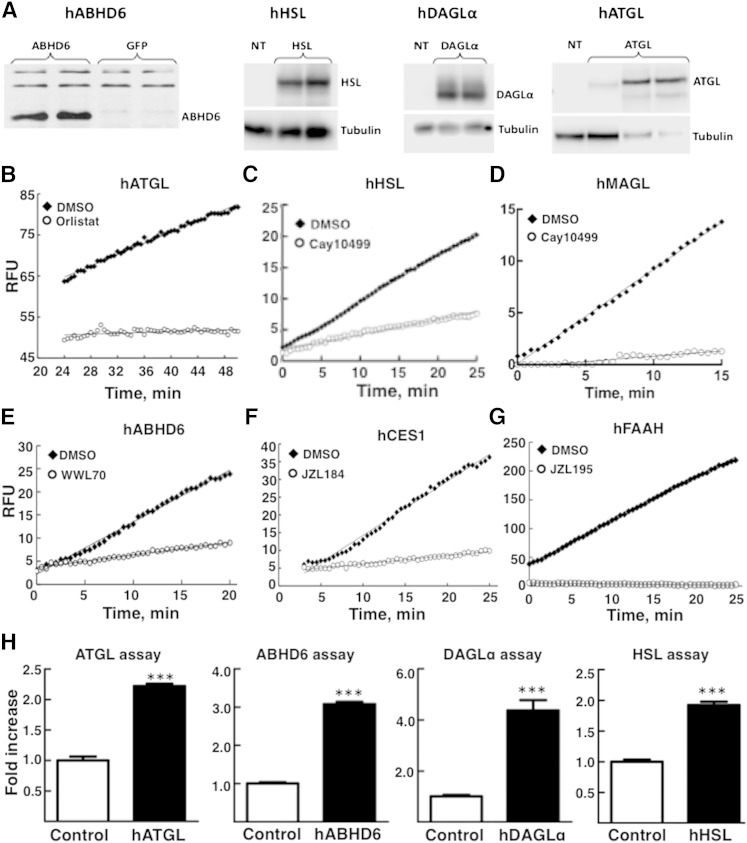

ATGL assay.

Using whole cell extracts from 293T cells overexpressing hATGL (Fig. 1A) or mouse ATGL, this enzyme activity could be assayed with EnzChek lipase substrate. We noticed that it is necessary to let the fluorescence stabilize for the first 15 to 20 min (not shown). The actual enzyme activity is recorded only after this initial stabilization, which is reflected by steady increase in fluorescence for at least 45 min. ATGL activity was almost completely inhibited by the panlipase inhibitor orlistat (Fig. 1B). Similar results were noticed with mouse ATGL, also expressed in 293T cells (data not shown). We also examined the need for added ATGL activator, CGI58 (3), for measuring ATGL activity. Coexpression of CGI58 along with ATGL or addition of separately expressed CGI58 to ATGL assay had no significant effect on the measured ATGL activity (not shown), which suggested that under the present assay conditions, ATGL is fully active. This also simplifies the assay procedure significantly. This assay, which does not involve any radioactive materials or reaction product extraction, could be easily adapted to high-throughput screening for the discovery of selective inhibitors of hATGL. This assay could also be adapted for measuring ATGL activity in various tissues where the enzyme is well expressed.

Fig. 1.

Expression of different recombinant lipases of human origin in 293T cells and assay of their activities and inhibition by corresponding inhibitors. Recombinant hABHD6, hHSL, hDAGLα, and hATGL were expressed in 293T cells as described in Materials and Methods. A: Western blot analysis of hABHD6, hHSL, hDAGLα, and hATGL. Control cell and lipase-expressing extracts (30 μg protein per lane) were processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Blots were probed with either anti-hABHD6 antibody (1:1,000 dilution), anti-hHSL antibody (1:1,000 dilution), anti-DAGLα antibody (1:1,000 dilution), or anti-hATGL antibody (1:1,000 dilution). The protein bands were visualized by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution) and chemiluminescence. Tubulin was probed as the loading control (1:10,000 dilution). Activities of recombinant human lipase enzymes using either cell extracts with overexpressed enzymes or purified proteins were measured as described in Materials and Methods. B: ATGL (30 μg whole cell extract protein) was assayed without and with 5 μM orlistat. C: HSL (1 μg whole cell extract protein) without or with 1 μM Cay10499. D: MAGL (0.025 ng purified enzyme protein per well) without or with 1 μM JZL184. E: ABHD6 (1 μg whole cell extract protein) without or with 2 μM WWL70. F: CES1 (0.06 μg purified enzyme) without or with 1 μM JZL184. G: FAAH (22.5 μg protein recombinant enzyme) without or with 1 μM JZL195. Reactions (relative fluorescence units, RFU) were measured continuously for up to 60 min, and the linear portion of the reaction progression is shown. The data are representative of two to three separate experiments. H: Lipase activities in control and lipase-overexpressing cells. Extracts from cells not transfected (control for hABHD6 assays) or vector transfected (control for hDAGL, hHSL, and hATGL assays) were used as control cell extracts. Enzyme activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods using fluorescence-based assays. N = 4 for all the assays, and all the activities were corrected for background (change in fluorescence without added enzyme) in the corresponding assays. Results are expressed as fold increase above corresponding control extracts and are mean ± SEM; *** P < 0.001, compared with control. The actual activities (RFU × 103/min/mg protein) for control cells are as follows: ATGL, 2.9 ± 0.04; ABHD6, 243 ± 8; DAGLα, 0.0313 ± 0.002; HSL, 697 ± 10.

HSL assay.

hHSL exists in multiple isoforms (25), and in the present study, we used the long form (118.3 kDa), which is available as purified recombinant enzyme commercially. We also used extracts of cells overexpressing either hHSL (118.3 kDa form; Fig. 1A) or mouse HSL (87.3 kDa), for assessing inhibitor sensitivity. hHSL could be rapidly assayed in 96-well format, using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol, an analog of 1-MAG, as substrate (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained with the mouse enzyme (not shown). Both human and mouse HSL enzymes were inhibited by Cay10499, although to different degrees (see below). This assay is adaptable for high-throughput screening.

MAGL assay.

As for HSL, MAGL activity was determined using both purified recombinant hMAGL (Fig. 1D) and extracts of cells overexpressing hMAGL (not shown), using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol as the substrate. Purified hMAGL activity was strongly inhibited by the recently described (26) MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (Fig. 1D).

ABHD6 assay.

We recently demonstrated (4) that the previously suggested MAG hydrolase ABHD6 (6) is indeed a MAG hydrolase. Even though an assay procedure for measuring the activity of ABHD6 was described earlier, it was based on the measurement of glycerol release with 1- and 2-arachidonoylglycerol as substrates using a tedious coupled enzyme assay (5) and is not amenable for high-throughput screening. We currently describe a simple single-step assay using cell extracts containing recombinant hABHD6 (Fig. 1A) that does not involve any product isolation and is adaptable for high-throughput screening. The ABHD6 assay is based on the hydrolysis of 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol, an analog of 1-MAG, to release thioglycerol, which is detected by fluorescent adduct formation with ThioGlo-1 (Fig. 1E). Recombinant hABHD6 is strongly inhibited by WWL70, an inhibitor described as an ABHD6-specific inhibitor (27).

CES1 assay.

hCES1 could also be assayed using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol as substrate as this enzyme is capable of hydrolyzing a wide variety of carboxylic acid esters. Interestingly, we found that the MAGL inhibitor JZL184 was also a powerful inhibitor of CES1 (Fig. 1F), as recognized recently (28).

FAAH assay.

A fluorescence-based commercially available FAAH assay kit that uses recombinant human FAAH (hFAAH) and the hydrolysis of AMC-arachidonoyl amide was used. hFAAH showed total inhibition by JZL195 (Fig. 1G), a dual inhibitor of MAGL and FAAH (29), and also by JZL184, a MAGL inhibitor (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibitor effectiveness and specificity of different lipases of human origin

| Inhibitor | Inhibition (%) at 5 μM | ||||||

| ATGL | HSL | DAGLα | MAGL | ABHD6 | FAAH | CES1 | |

| ATGL inhibitors | |||||||

| Orlistat | 100 | 20 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 5 | 70 |

| WWL64 (18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 85 |

| ATGListatin (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 25 |

| HSL inhibitors | |||||||

| Cay10499 | 95 | 67 | 60 | 95 | 90 | — | 95 |

| WWL11 (18) | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 70 |

| Compound 13f (19) | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 65 | — | 90 |

| DAGLα inhibitors | |||||||

| KT109 (20) | 0 | 0 | 95 | 10 | 85 | 0 | 90 |

| KT172 (20) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 90 |

| RHC20867 | 0 | 26 | 10 | 20 | 80 | — | 90 |

| MAGL inhibitor | |||||||

| JZL184 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 95 |

| MAGL/FAAH inhibitor | |||||||

| JZL195 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 95 |

| ABHD6 inhibitors | |||||||

| WWL70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95 | 0 | 95 |

| KT195 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 90 |

Activities of recombinant human lipase enzymes were measured using either cell extracts with overexpressed enzymes (hATGL, hHSL, hDAGLα, hABHD6) or purified proteins (hMAGL, hFAAH, hCES1) as described in Materials and Methods. The dashes indicate “not determined.” Values shown are average of two to six determinations.

There is an ∼2- to 4-fold increase in corresponding lipase activity in extracts from cells overexpressing ATGL, ABHD6, DAGLα, and HSL, measured using fluorescence-based assays (Fig. 1H). Background activity measured in control empty vector-transfected cell extracts was used to correct the corresponding enzyme activity measured in overexpressed cell extracts while calculating the inhibitor specificities.

Expression of recombinant hDAGLα and its assay

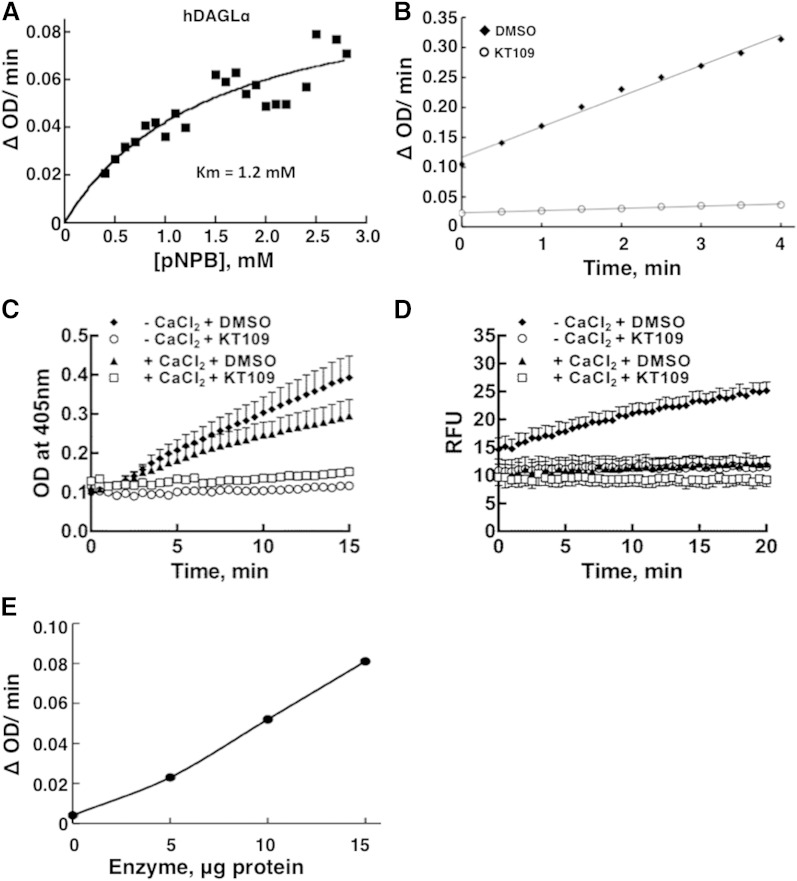

The commercially available plasmid and adenoviral constructs of hDAGLα were not found to be effective for DAGL expression in several mammalian cell lines (293T, A549, and HeLa), probably because of the presence of other start sites in the 5′ UTR. We constructed a novel DAGLα expression vector (pIRES2-DAGLα), using only the coding sequence from the commercial plasmid of DAGLα without the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Using 293T cells, we could express hDAGLα in ample quantities (Fig. 1A), after transfection with pIRES2-DAGLα. We noticed that both the 5′ and 3′ noncoding UTRs in the original DAGLα cDNA somehow interfere with the expression of DAGLα thus, they need to be removed. The recombinant hDAGLα could hydrolyze the artificial substrate pNPB effectively, as described earlier (22), with a Km of 1.2 mM (Fig. 2A). This activity is suppressed by the recently described DAGL inhibitor (20) KT109 (Fig. 2B), indicating that the activity being measured is indeed due to DAGLα. There was negligible activity with extracts prepared from control plasmid transfected cells (not shown). It is important to note that in order to minimize the contaminating activities, DAGLα is measured in the cell membrane extracts and not in the whole cell extracts. Contrary to the Ca2+ dependence of DAGLα activity described earlier (7), we noticed that the enzyme activity with either pNPB or EnzChek lipase substrate as substrates is actually lower in the presence of added Ca2+ (Fig. 2C, D). DAGLα has been shown to act on EnzChek fluorogenic lipase substrate (30). The reason for this apparent discrepancy on calcium dependency is not clear but may relate to the ability of calcium to complex and precipitate the released fluorescent fatty acid or the yellow-colored pNPB. The recombinant DAGLα cell membrane extracts showed good linearity of enzyme activity with increasing protein concentration (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Assay of hDAGLα and its inhibition by KT109. hDAGLα-expressing cell extracts (10 μg cell membrane extract protein) were used as enzyme source. A: Substrate concentration curve, using pNPB. B: DAGLα activity assayed without or with 1 μM KT109. C: DAGLα activity with pNPB substrate is not stimulated by CaCl2 (5 mM) but is inhibited by KT109. D: DAGLα activity with EnzChek lipase substrate is lower with CaCl2 (5 mM) and is inhibited by KT109. E: Effect of enzyme protein concentration on the activity. The data are representative of two to three separate experiments.

ABHD6 activity and inhibition

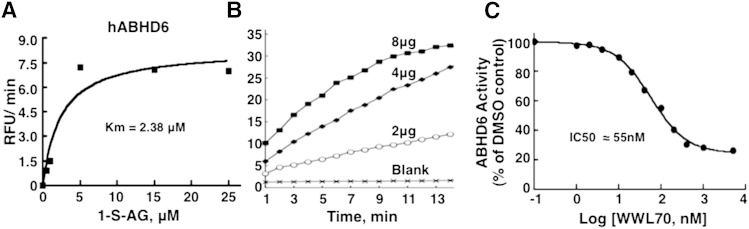

Recombinant hABHD6 showed high affinity for 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol, with a Km of 2.38 μM (Fig. 3A). The recombinant ABHD6 also showed increased activity with increase in enzyme protein concentration (whole cell extract) (Fig. 3B), and this activity is strongly inhibited by WWL70, with an IC50 of 55 nM (Fig. 3C), which is similar to the earlier reported values (∼70 nM), using different type of assay procedures (27). Using the ABHD6 assay described here, we could screen a small library of 120 compounds for identifying selective inhibitors for this enzyme (not shown). The 120 compound library is a focused library developed based on the structure of WWL70, a known ABHD6 inhibitor. While most of these 120 compounds were inhibitory to ABHD6, identification of the compounds that showed selectivity toward ABHD6 was achieved by testing the inhibitory potency of these compounds against other lipases using the assays described in the present work.

Fig. 3.

Assay of hABHD6 and its inhibition by WWL70. hABHD6-expressing 293T cell extracts were used as the enzyme source, and the activity was assayed using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol (1-S-AG). A: Substrate concentration curve showing a Km of 2.38 μM. B: Effect of enzyme protein concentration on activity. C: IC50 for WWL70. The data are representative of two to five separate experiments.

hCES1 activity and inhibition

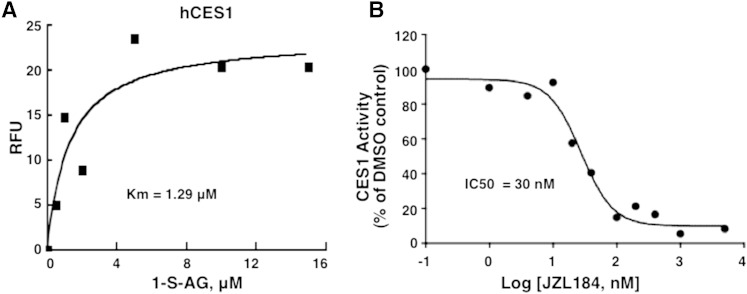

Using the assay described here, we measured a Km of 1.29 μM for 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol for purified hCES1 (Fig. 4A). The classical MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (26) showed a strong inhibitory potency for CES1, with an IC50 of 30 nM (Fig. 4B). In order to adapt this assay for cell extracts, it is necessary to eliminate other contaminating hydrolase activities. Screening of several inhibitors, supposedly specific for individual lipases, surprisingly revealed that all of these also inhibit CES1 (Table 1). Thus, caution must be exercised when using these “specific” inhibitors for dissecting out the role of individual lipases/hydrolases in biological processes.

Fig. 4.

Assay of hCES1. Purified hCES1 was used with the substrate 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol (1-S-AG). A: Substrate concentration curve, showing a Km of 1.29 μM. B: IC50 for JZL184. The data are representative of two to three separate experiments.

Inhibitor specificities of different lipases of human and murine origin

Using the new lipase assays, we examined the effectiveness of various commercially available and also recently described inhibitors against these enzymes (Table 1). Some of the inhibitors were not found to be as specific as previously reported.

ATGL inhibitors.

A panlipase inhibitor, orlistat, was able to strongly inhibit hATGL, hDAGLα, hMAGL, hABHD6, and hCES1. Orlistat’s effect on hHSL was modest, and hFAAH was not inhibited. A recent study on serine hydrolase inhibitors (18) using rodent tissues showed that WWL64 is a specific inhibitor of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 2/ATGL. Another study (17) reported a specific ATGL inhibitor, ATGListatin, using recombinant mouse ATGL. We tested both of these inhibitors and surprisingly found that they do not affect hATGL (Table 1). Furthermore, we found that hCES1 could be inhibited strongly by WWL64, whereas ATGListatin showed moderate inhibition. Neither WWL64 nor ATGListatin affected other lipases tested.

HSL inhibitors.

Similarly, we also examined the specificity of known HSL inhibitors. Cay10499, which was previously shown to also inhibit hMAGL (31), was found to inhibit all the human lipases tested (Table 1 and Table 2). An HSL inhibitor, WWL11, discovered using the activity-based protein profiling approach against mouse HSL (18), was found to have much less effect on hHSL but significantly inhibited hCES1. Another mouse HSL-directed inhibitor, Compound 13f, described recently (19), also showed much less inhibition of hHSL, but it inhibited both hABHD6 and hCES1 (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

IC50 of known inhibitors for different human lipases

| Inhibitor | IC50, nM | |||||

| ATGL | HSL | DAGLα | MAGL | ABHD6 | CES1 | |

| ATGL inhibitors | ||||||

| Orlistat | 1.2 | >5,000 | ∼3 | 233 | 33 | >1,000 |

| WWL64 (18) | >5,000 | >5,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | 12.7 |

| ATGListatin (17) | >5,000 | >5,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 |

| HSL inhibitors | ||||||

| Cay10499 | 66 | 79.8 | ∼5,000 | 54.3 | 209 | 0.9 |

| WWL11 (18) | >1,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | ∼600 |

| Compound 13f (19) | >1,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | 191 | 30.3 |

| DAGLα inhibitors | ||||||

| KT109 (20) | >1,000 | >5,000 | 8 | >1,000 | 23 | 24 |

| KT172 (20) | >1,000 | >5,000 | 6 | >1,000 | 15 | 16 |

| RHC20867 | >1,000 | >5,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | 1,130 | 960 |

| MAGL inhibitor | ||||||

| JZL184 | >1,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | 65 | >5,000 | 30 |

| MAGL/FAAH inhibitor | ||||||

| JZL195 | >1,000 | >1,000 | >5,000 | 11.3 | 435 | 4.2 |

| ABHD6 inhibitors | ||||||

| WWL70 | >1,000 | >5,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | 55 | 1.1 |

| KT195 (20) | >1,000 | >5,000 | >5,000 | >1,000 | 150 | 15 |

Activities of recombinant human lipase enzymes were measured using either cell extracts with overexpressed enzymes (hATGL, hHSL, hDAGLα, hABHD6) or purified proteins (hHSL, hMAGL, hCES1) as described in Materials and Methods. To generate IC50 values, inhibitors were used at concentrations ranging from 0.5 nM to 5 µM. Values shown are average of two to six determinations.

DAGLα inhibitors.

Two recently reported inhibitors against mouse DAGLβ, KT109 and KT172, were found to inhibit hDAGLα effectively, but these compounds also inhibited hABHD6, as noted before (20), and also hCES1 (Tables 1 and 2). The widely used DAGL inhibitor, RHC20867, actually barely inhibited hDAGLα at 5 μM but inhibited hHSL, hMAGL, hABHD6, and hCES1 to different degrees (Table 1). DAGL activity with either pNPB or EnzChek lipase substrate was inhibited by KT109, and the presence or absence of Ca2+ did not affect this inhibition (Fig. 2C, D)

MAGL inhibitors.

JZL184 was found to be relatively more specific to MAGL, even though it also strongly inhibited FAAH and CES1 (Table 1), and to a lesser extent ABHD6, as noted earlier (26). However, JZL195, the dual inhibitor of MAGL and FAAH, also inhibited ABHD6, CES1, and, to a lesser extent, HSL.

ABHD6 inhibitors.

WWL70 and KT195 were found to be relatively more specific to ABHD6, with only CES1 being inhibited among other lipases tested.

Overall, the results show that many of the inhibitors described earlier against rodent enzymes do not effectively inhibit the corresponding human enzymes and also that several of the compounds lack specificity. The IC50 values (Table 2) of the tested inhibitors for some of these human lipases (ATGL, HSL, DAGLα, MAGL, ABHD6, and CES1) relate to their inhibitory effects seen at 5 μM concentration (Table 1). Thus, results obtained using these compounds to specifically target a given lipase in a human cell/ tissue system must be interpreted cautiously, taking into account of the presence/absence of other enzymes, which may also be targeted. The specificity of these inhibitors against murine enzymes remains to be assessed.

As we noticed that some of the previously described inhibitors against mouse lipases were ineffective against the corresponding human enzymes, we directly examined this by comparing the inhibitor efficacy against recombinant human and mouse ATGL and HSL (Table 3). While orlistat and Cay10499 were inhibitory against both human and mouse enzymes, hHSL was relatively less inhibited by either of these compounds. The inhibitors developed against mouse ATGL (WWL64 and ATGListatin) and mouse HSL (WWL11 and Compound 13f) were highly effective in inhibiting the corresponding mouse enzymes but have much less effect on the human enzymes (Table 3). On the other hand, DAGLα inhibitors (KT109, KT172, and RHC20867) and MAGL inhibitors (JZL184 and JZL195) were inhibitory to mouse ATGL and HSL to a variable extent, even though these compounds showed no significant effect on hATGL and hHSL.

TABLE 3.

Different inhibitor sensitivity of human and mouse ATGL and HSL

| Inhibitor | Inhibition (%) at 5 μM | |||

| ATGL | HSL | |||

| Human | Mouse | Human | Mouse | |

| ATGL inhibitors | ||||

| Orlistat | 90 | 90 | 36 | 95 |

| WWL64 (18) | 0 | 32 | 0 | 80 |

| ATGListatin (17) | <10 | 84 | 0 | 0 |

| HSL inhibitors | ||||

| Cay10499 | 95 | 95 | 67 | 95 |

| WWL11 (18) | 0 | 0 | 16 | 80 |

| Compound 13f (19) | 0 | 0 | 17 | 90 |

| DAGLα inhibitors | ||||

| KT109 (20) | 0 | — | 0 | 70 |

| KT172 (20) | 0 | — | 0 | 75 |

| RHC20867 | 0 | 28 | 26 | 98 |

| MAGL inhibitor | ||||

| JZL184 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| MAGL/FAAH inhibitor | ||||

| JZL195 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 70 |

| ABHD6 inhibitors | ||||

| WWL70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KT195 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Activities of recombinant human lipase enzymes were measured using cell extracts with overexpressed enzymes as described in Materials and Methods. The dashes indicate “not determined.” Values shown are average of two to six determinations.

The different effects of these compounds on mouse and human enzymes may be because of subtle but significant differences in their amino acid sequences and reactivity toward these inhibitors. Several recent studies have used some of these compounds to “specifically” target a given lipase in human and also rodent cells, without realizing their efficacy as well as specificity. Results from such studies can lead to erroneous conclusions and need to be interpreted cautiously. Thus, it is important to ensure that the inhibitors developed against rodent enzymes also work against human enzymes, if the compounds are to be used with human cells and tissues. This becomes particularly important for drug discovery applications.

Advantages of the described simplified assays for lipases

The available procedures for measuring the reaction products (e.g., glycerol or fatty acids) of the lipases using their natural authentic substrates (such as acyl glycerides) are not as sensitive as the currently described methods. For example, ABHD6 assay using its “authentic” natural substrate, 1-palmitoylglycerol, requires measuring the reaction products glycerol or palmitate. We show that measurement of glycerol released in this reaction is much less sensitive and reliable as compared with measuring the activity of this enzyme (same amount of enzyme protein) using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol as the substrate (Table 4). In fact, signal-to-noise ratio for the measurement of glycerol produced from 1-palmitoylglycerol was only about 1.2 to 1.9 in comparison with 7 to 23 for the fluorogenic assay with 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol. Measurement of palmitate requires its extraction, derivatization, and processing for HPLC, which is very laborious and cumbersome with low sensitivity and yields. Neither of these approaches is amenable for high-throughput screening protocols. The same logic applies for ATGL, HSL, and DAGL, which use acylglycerides as the substrates and produce fatty acids and glycerol.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of ABHD6 assays using 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol and 1-palmitoylglycerol as substrates

| Enzyme Source | 1-S-Arachidonoylthioglycerol 5 μM (RFU/min/mg protein) × 103 | 1-Palmitoylglycerol (cpm/min/mg protein) × 103 | |

| 5 μM | 50 μM | ||

| Activity | Activity | Activity | |

| NT | 243 ± 8 | — | — |

| NT + 5 µM WWL70 | 215 ± 10 | — | — |

| ABHD6 transfected | 748 ± 14 | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 26.7 ± 7 |

| ABHD6 transfected + 5 µM WWL70 | 314 ± 15 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 2 |

NT, extract from not transfected 293 cells; ABHD6 transfected, extract from ABHD6-overexpressing 293 cells. N = 4 for 1-palmitoylglycerol assays, and N = 5 for 1-S-arachidonoylthioglycerol assays. Background corrected values are shown. Results are mean ± SEM.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the importance of lipases in health and disease, there are no simplified screening assays for measuring their activity and for the discovery of specific drugs targeting these enzymes. We describe here simplified and reliable assays of lipolytic enzymes using recombinant human and mouse enzymes either in cell extracts or using purified enzymes. Using these assays, we could screen a small library of 120 compounds and test the specificity of several known inhibitors of the lipases. These assays are easily adaptable for high-throughput screening with larger libraries of compounds, even though they cannot be directly used for measuring endogenous enzyme activities. The results from this study caution other researchers regarding the use of some of the previously described “highly specific” lipase inhibitors, as they are in fact not found to be specific and certain inhibitors discovered using rodent lipases are ineffective against their human counterparts.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ABHD6

- α/β-hydrolase domain 6

- AMC

- 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- ATGL

- adipose triglyceride lipase

- CES1

- carboxylesterase 1

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- DAGL

- diacylglycerol lipase

- FAAH

- fatty acid amide hydrolase

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescence protein

- hABHD6

- human ABHD6

- hATGL

- human ATGL

- hCES1

- human CES1

- hDAGLα

- human DAGLα hFAAH, human FAAH

- hHSL

- human HSL

- hMAGL

- human MAGL

- HSL

- hormone sensitive lipase

- MAG

- monoacylglycerol

- MAGL

- monoacylglycerol lipase

- pNPB

- p-nitrophenylbutyrate

- UTR

- untranslated region

This work was supported by funds from Amorchem LP, Montreal, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants to M.P. and S.R.M.M. M.P. holds the Canada Research Chair in Diabetes and Metabolism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prentki M., and Madiraju S. R.. 2008. Glycerolipid metabolism and signaling in health and disease. Endocr. Rev. 29: 647–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentki M., Matschinsky F. M., and Madiraju S. R.. 2013. Metabolic signaling in fuel-induced insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 18: 162–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young S. G., and Zechner R.. 2013. Biochemistry and pathophysiology of intravascular and intracellular lipolysis. Genes Dev. 27: 459–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao S., Mugabo Y., Iglesias J., Xie L., Delghingaro-Augusto V., Lussier R., Peyot M. L., Joly E., Taib B., Davis M. A., et al. 2014. alpha/beta-Hydrolase domain-6-accessible monoacylglycerol controls glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 19: 993–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navia-Paldanius D., Savinainen J. R., and Laitinen J. T.. 2012. Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of human alpha/beta-hydrolase domain containing 6 (ABHD6) and 12 (ABHD12). J. Lipid Res. 53: 2413–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankman J. L., Simon G. M., and Cravatt B. F.. 2007. A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chem. Biol. 14: 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisogno T., Howell F., Williams G., Minassi A., Cascio M. G., Ligresti A., Matias I., Schiano-Moriello A., Paul P., Williams E. J., et al. 2003. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J. Cell Biol. 163: 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S. K., Eder S., Schauer S., Diwoky C., Temmel H., Guertl B., Gorkiewicz G., Tamilarasan K. P., Kumari P., Trauner M., et al. 2011. Adipose triglyceride lipase contributes to cancer-associated cachexia. Science. 333: 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyot M. L., Guay C., Latour M. G., Lamontagne J., Lussier R., Pineda M., Ruderman N. B., Haemmerle G., Zechner R., Joly E., et al. 2009. Adipose triglyceride lipase is implicated in fuel- and non-fuel-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 16848–16859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J. W., Wang S. P., Casavant S., Moreau A., Yang G. S., and Mitchell G. A.. 2012. Fasting energy homeostasis in mice with adipose deficiency of desnutrin/adipose triglyceride lipase. Endocrinology. 153: 2198–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peyot M. L., Nolan C. J., Soni K., Joly E., Lussier R., Corkey B. E., Wang S. P., Mitchell G. A., and Prentki M.. 2004. Hormone-sensitive lipase has a role in lipid signaling for insulin secretion but is nonessential for the incretin action of glucagon-like peptide 1. Diabetes. 53: 1733–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fex M., Haemmerle G., Wierup N., Dekker-Nitert M., Rehn M., Ristow M., Zechner R., Sundler F., Holm C., Eliasson L., et al. 2009. A beta cell-specific knockout of hormone-sensitive lipase in mice results in hyperglycaemia and disruption of exocytosis. Diabetologia. 52: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignatowska-Jankowska B. M., Ghosh S., Crowe M. S., Kinsey S. G., Niphakis M. J., Abdullah R. A., Tao Q., O’Neal S. T., Walentiny D. M., Wiley J. L., et al. 2014. In vivo characterization of the highly selective monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor KML29: antinociceptive activity without cannabimimetic side effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171: 1392–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura D. K., Lombardi D. P., Chang J. W., Niessen S., Ward A. M., Long J. Z., Hoover H. H., and Cravatt B. F.. 2011. Monoacylglycerol lipase exerts dual control over endocannabinoid and fatty acid pathways to support prostate cancer. Chem. Biol. 18: 846–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reisenberg M., Singh P. K., Williams G., and Doherty P.. 2012. The diacylglycerol lipases: structure, regulation and roles in and beyond endocannabinoid signalling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367: 3264–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L., Heneghan J. F., Michael G. J., Stanish L. F., Egertova M., and Rittenhouse A. R.. 2008. L- and N-current but not M-current inhibition by M1 muscarinic receptors requires DAG lipase activity. J. Cell. Physiol. 216: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer N., Schweiger M., Romauch M., Grabner G. F., Eichmann T. O., Fuchs E., Ivkovic J., Heier C., Mrak I., Lass A., et al. 2013. Development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting adipose triglyceride lipase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9: 785–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachovchin D. A., Mohr J. T., Speers A. E., Wang C., Berlin J. M., Spicer T. P., Fernandez-Vega V., Chase P., Hodder P. S., Schurer S. C., et al. 2011. Academic cross-fertilization by public screening yields a remarkable class of protein phosphatase methylesterase-1 inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108: 6811–6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebdrup S., Refsgaard H. H., Fledelius C., and Jacobsen P.. 2007. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship for a novel class of potent and selective carbamate-based inhibitors of hormone selective lipase with acute in vivo antilipolytic effects. J. Med. Chem. 50: 5449–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu K. L., Tsuboi K., Adibekian A., Pugh H., Masuda K., and Cravatt B. F.. 2012. DAGLbeta inhibition perturbs a lipid network involved in macrophage inflammatory responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8: 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu D., Manjur J., and Jin W.. 2011. Determination of lipoprotein lipase activity using a novel fluorescent lipase assay. J. Lipid Res. 52: 826–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedicord D. L., Flynn M. J., Fanslau C., Miranda M., Hunihan L., Robertson B. J., Pearce B. C., Yu X. C., Westphal R. S., and Blat Y.. 2011. Molecular characterization and identification of surrogate substrates for diacylglycerol lipase alpha. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411: 809–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Storey B. T., Alvarez J. G., and Thompson K. A.. 1998. Human sperm glutathione reductase activity in situ reveals limitation in the glutathione antioxidant defense system due to supply of NADPH. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 49: 400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley D. C., and Kaslow H. R.. 1989. Radiometric assays for glycerol, glucose, and glycogen. Anal. Biochem. 180: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampidonis A. D., Rogdakis E., Voutsinas G. E., and Stravopodis D. J.. 2011. The resurgence of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL) in mammalian lipolysis. Gene. 477: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long J. Z., Li W., Booker L., Burston J. J., Kinsey S. G., Schlosburg J. E., Pavon F. J., Serrano A. M., Selley D. E., Parsons L. H., et al. 2009. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W., Blankman J. L., and Cravatt B. F.. 2007. A functional proteomic strategy to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized hydrolases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129: 9594–9595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crow J. A., Bittles V., Borazjani A., Potter P. M., and Ross M. K.. 2012. Covalent inhibition of recombinant human carboxylesterase 1 and 2 and monoacylglycerol lipase by the carbamates JZL184 and URB597. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84: 1215–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long J. Z., Nomura D. K., Vann R. E., Walentiny D. M., Booker L., Jin X., Burston J. J., Sim-Selley L. J., Lichtman A. H., Wiley J. L., et al. 2009. Dual blockade of FAAH and MAGL identifies behavioral processes regulated by endocannabinoid crosstalk in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106: 20270–20275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu K-L., Tsuboi K., Speers A. E., Brown S. J., Spicer T., Fernandez-Vega V., Ferguson J., Cravatt B. F., Hodder P., and Rosen H.. 2010. Optimization and characterization of a triazole urea inhibitor for diacylglycerol lipase beta (DAGL-beta). In Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muccioli G. G., Labar G., and Lambert D. M.. 2008. CAY10499, a novel monoglyceride lipase inhibitor evidenced by an expeditious MGL assay. ChemBioChem. 9: 2704–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]