Abstract

Idioms of distress communicate suffering via reference to shared ethnopsychologies, and better understanding of idioms of distress can contribute to effective clinical and public health communication. This systematic review is a qualitative synthesis of “thinking too much” idioms globally, to determine their applicability and variability across cultures. We searched eight databases and retained publications if they included empirical quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research regarding a “thinking too much” idiom and were in English. In total, 138 publications from 1979–2014 met inclusion criteria. We examined the descriptive epidemiology, phenomenology, etiology, and course of “thinking too much” idioms and compared them to psychiatric constructs. “Thinking too much” idioms typically reference ruminative, intrusive, and anxious thoughts and result in a range of perceived complications, physical and mental illnesses, or even death. These idioms appear to have variable overlap with common psychiatric constructs, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. However, “thinking too much” idioms reflect aspects of experience, distress, and social positioning not captured by psychiatric diagnoses and often show wide within-cultural variation, in addition to between-cultural differences. Taken together, these findings suggest that “thinking too much” should not be interpreted as a gloss for psychiatric disorder nor assumed to be a unitary symptom or syndrome within a culture. We suggest five key ways in which engagement with “thinking too much” idioms can improve global mental health research and interventions: it (1) incorporates a key idiom of distress into measurement and screening to improve validity of efforts at identifying those in need of services and tracking treatment outcomes; (2) facilitates exploration of ethnopsychology in order to bolster cultural appropriateness of interventions; (3) strengthens public health communication to encourage engagement in treatment; (4) reduces stigma by enhancing understanding, promoting treatment-seeking, and avoiding unintentionally contributing to stigmatization; and (5) identifies a key locally salient treatment target.

Keywords: cultural concept of distress, idiom of distress, depression, anxiety, PTSD, ethnopsychology, global mental health, transcultural psychiatry

Introduction

Several decades ago, Nichter (1981) outlined a research agenda that takes idioms of distress as its theoretical object, defining them as “socially and culturally resonant means of experiencing and expressing distress in local worlds” (Nichter, 2010, 405). Terms used to describe such experiences or expressions have been alternatively labeled idioms of distress, culture bound syndromes, or cultural syndromes. With the publication of DSM-5, the term cultural concepts of distress has been adopted to refer to “ways that cultural groups experience, understand, and communicate suffering, behavioral problems, or troubling thoughts and emotions” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, 787).

Scholars have suggested that such constructs be incorporated into research and interventions in efforts to better understand forms of suffering; to improve clinical communication, service usage, and treatment outcomes; and to reduce stigma (Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez 2010; Kohrt et al. 2008; Kohrt et al., 2010; Kleinman, 1988). For example, Kohrt et al. (2010) report that in Nepal, NGO and health professionals referred to psychological trauma using terminology that was stigmatizing due to ethnopsychological associations with karma. They suggest that treatment initiatives incorporate idioms of distress, contextualized within Nepali ethnopsychology, to avoid inadvertently stigmatizing mental health patients.

Additionally, researchers have used idioms of distress to develop and adapt locally relevant assessment instruments for use in epidemiological and clinical studies and to guide decisions regarding appropriate treatments and programs (Betancourt, et al., 2009; Haroz et al., 2014; Kohrt et al., 2011; Verdeli, et al., 2008). For example, researchers recognize that using measurement instruments designed to capture DSM or ICD-defined syndromes may result in missing culturally relevant symptoms that are associated with impaired functioning (Flaherty, et al., 1988; Kleinman, 1987; Weaver & Kaiser, 2015). Some studies have thus drawn on idioms of distress alongside standard measures, making assessment more culturally sensitive (Hinton et al., 2012c; Kaiser et al., 2013; Weaver & Kaiser, 2015). Such an approach proved successful in Sri Lanka, where idioms of distress predicted functional impairment above and beyond a PTSD scale and depression inventory (Jayawickreme et al., 2012).

However, anthropologists have critiqued some applications of idioms of distress, arguing that they are reduced to psychiatric categories in interventions. Unlike psychiatric categories, idioms of distress can communicate suffering that does not reference psychopathological states, instead expressing collective social anxiety, engaging in symbolic protest, or providing “metacommentary on social injustice” (Abramowitz, 2010; De Jong & Reis, 2010; Nichter, 2010, 404; Pedersen et al., 2010). Also unlike psychiatric categories, idioms of distress are explicitly situated within a cultural milieu that is recognized to be complex and dynamic (Briggs et al. 2003; Kirmayer & Young, 1998; Massé, 2007). Considering idioms of distress as communicative tools draws attention to questions of power, such as who defines categories of distress? and what forms of distress are most relevant in healing contexts? (Guarnaccia et al., 2003; Kohrt et al., 2014).

For anthropologists, much of the value of idioms of distress derives from the way they reflect notions of personhood, local moral worlds, and engagement with social change and struggle, elements that are often disregarded in interventions. Some anthropologists have therefore critiqued psychiatrists and public health practitioners for ignoring this broader context and more nuanced meaning (Abramowitz, 2010; Sakti, 2013). Abramowitz presents an example of humanitarian organizations reducing a Liberian cultural syndrome (Open Mole) to psychiatric phenomena like PTSD, largely because they more readily fit the organizations’ biomedical epistemology. In this process of translation, organizations ultimately invalidated the narratives of suffering and loss that were being experienced and communicated as Open Mole. In this review, we aim to consider idioms of distress in a way that privileges local meaning while also attending to potential means of informing psychiatric and public health interventions.

To date, the majority of research on idioms of distress has been limited to a specific cultural context. While there is long and ongoing practice of testing applications of psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., DSM and ICD criteria) across cultural populations, there is a gap in the research with regard to examining idioms of distress that may share similarities across cultural groups and settings. The first major attempt to do this was the work of Simons and Hughes (1985), who developed a taxonomy of culture bound syndromes, which categorized syndromes by the presumed level of biological pathogenicity and the type of symptom clusters. In the past 30 years, there has been a lack of effort to re-examine shared elements of idioms of distress across cultures. We chose to evaluate one previously unexamined category of idioms of distress that appears to be common across cultural groups: thinking too much.

“Thinking too much” idioms have appeared frequently in ethnographic studies of mental distress and represent one of the cultural concepts of distress in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013: 834). Given that “thinking too much” is often mentioned in studies related to non-European/North American cultures and contexts, we set out to more fully understand the descriptive epidemiology and complex meaning of these idioms in the literature. The current study aimed to systematically review the “thinking too much” literature from several perspectives: (1) to give an overview of studies to date by geographical area and population; (2) to describe and compare the phenomenology, course and consequences, etiology, and vulnerability factors; (3) to examine studies identifying associated psychiatric disorders; and (4) to examine and compare local attempts at coping with these forms of distress. Our goal is to provide an in-depth description and analysis of “thinking too much” idioms in an effort to determine the applicability and variability of this concept across cultures, as well as explore implications for assessment and treatment cross-culturally. The review is particularly timely given the inclusion of “thinking too much” as one of the cultural concepts of distress in DSM-5.

Methods

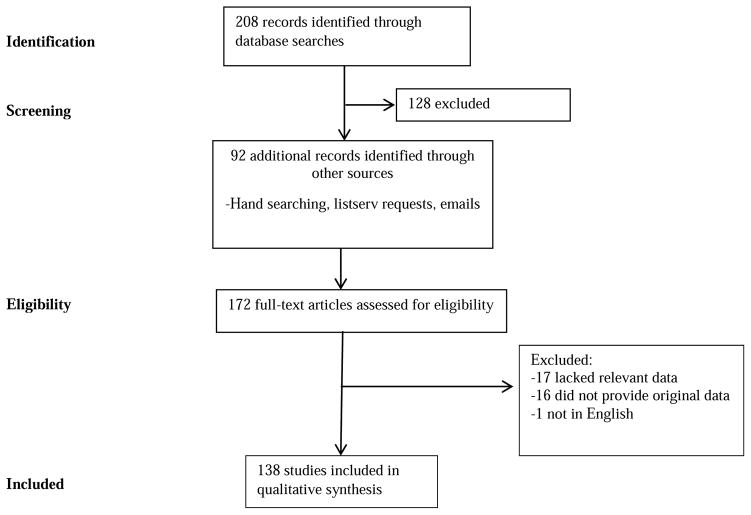

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). First, we searched eight databases: PubMed, PsychInfo, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Embase, Sociological Abstracts, Anthrosource, and Anthropology Plus with the following search terms: (Anthropology OR Ethnology OR “Cross-Cultural Comparison” OR Ethnopsychology OR “Cultural Characteristics” OR Ethnography OR “cross cultur*” OR “idioms of distress” OR “mental health” OR psychology) and (“Thinking too much” OR “Too much thinking” OR “lots of thinking” OR “lots of thoughts” OR “too many thoughts”). There were no limits in terms of language or publication date on any of the searches. In addition, we searched Google Scholar for the term “thinking too much” and contacted listservs related to medical and psychological anthropology, transcultural psychiatry, and community participatory research to ensure that we had as complete a reference list as possible. Initial publications were collected over a two-week period in November 2012, with a second database search conducted in December 2014. Publications included in the review consisted of articles, book chapters, dissertations, books, unpublished manuscripts, and reports. See Figure 1 for a summary of our search process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review process

Publications were included for full review if they met the following criteria: (1) the publication mentioned “thinking too much” or a closely related idiom in the body of the text, (2) the publication included empirical qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research regarding the idiom, and (3) the publication was in English. Regarding criterion 1, although our database search terms were broader than “thinking too much” (including “too much thinking,” “lots of thinking,” “lots of thoughts,” and “too many thoughts”), this was done in order to be inclusive in our initial search. Review of publications then identified those referencing a relevant idiom. Rather than any reference to troubled cognition or problematic thoughts, the idiom of distress had to include a component of excess or “too much.” For example, a publication mentioning “problems with thoughts” would not be sufficient to meet inclusion criteria. However, when publications that otherwise meet inclusion criteria describe problems with thoughts as part of their characterization of “thinking too much,” we do include such descriptions in our analysis. In our Results, we present English translations of idioms as reported by authors and also include idioms in the original language when possible.

Two steps were taken in reviewing the publications. Initially, titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine whether they met the above criteria. If the title and abstract provided insufficient information to determine whether criteria were met, the publication was retained for full review. Second, the publications were classified as either an “in depth” or a “briefly mentioned” publication. “In depth” publications focused on “thinking too much” as a main focus of the work and generally provided a qualitative description of the idiom’s phenomenology, etiology, and course. “Briefly mentioned” publications mentioned “thinking too much” in the text but did not provide extensive information on the idiom. Authors BNK and EH independently reviewed all publications for inclusion/exclusion and achieved 78% agreement. In cases of disagreement, publications were checked collaboratively and decided by consensus. In addition, the authors reviewed and discussed all eligible publications in order to classify them as “briefly mentioned” or “in depth.”

For coding and analysis, each publication was imported into MaxQDA (VERBI, 1989–2010). Two authors (BNK and EH) coded all of the publications; to increase consistency, BNK coded all “in depth” publications, and EH coded all “briefly mentioned” publications. Coding and analysis focused on (1) descriptive epidemiology, including world region and population; (2) descriptions of “thinking too much,” including phenomenology, course and consequences, etiology and vulnerability groups, and ethnopsychological information that contributes to the understanding of the idiom; (3) comparative diagnoses; and 4) treatment and coping mechanisms associated with the idiom. Coding also included method of elicitation, such as whether “thinking too much” was part of a questionnaire administered by the researchers or whether it emerged during qualitative work and methods for drawing comparison to psychiatric constructs, as well as whether “thinking too much” represented a symptom, syndrome, and/or cause.

Results

A total of 138 articles, books, book chapters, unpublished dissertations and manuscripts, and programmatic reports were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Of these publications, 61 were classified as “in depth” and 77 as “briefly mentioned.” Publication dates ranged from 1979–2014. See Supplemental Table 1 for a list of all publications [INSERT LINK TO SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE].

Aim 1. Geographic Locations and Populations

All publications (n=138) reported the geographic origin of the study population: Africa (n=60, 43.5%), Southeast Asia (n=41, 29.7%), Central America/Caribbean (n=13, 9.4%), South Asia (n=12, 8.7%), United States/Europe (n=4, 2.9%), Australia (n=4, 2.9%), the Middle East (n=3, 2.2%), and South America (n=1, 0.7%). A total of 27.5% (n=38) included data on refugee or immigrant populations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of publications by region and type of population (n=138)a

| Number of study populations | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Region of the world | ||

| Africa | 60 | 43.5 |

| Australia | 4 | 2.9 |

| Central America/Caribbean | 13 | 9.4 |

| Middle East | 3 | 2.2 |

| South America | 1 | 0.7 |

| South Asia | 12 | 8.7 |

| Southeast Asia | 41 | 29.7 |

| United States/Europe | 4 | 2.9 |

| Refugee/immigrant populationb | 37 | 26.8 |

| Afghans | 3 | 7.5 |

| Bhutanese | 1 | 2.5 |

| Cambodians | 19 | 47.5 |

| Congolese | 1 | 2.5 |

| Hmong | 1 | 2.5 |

| Karenni | 1 | 2.5 |

| Somali | 1 | 2.5 |

| Sudanese | 4 | 10.0 |

| Tibetan | 1 | 2.5 |

| Ugandan | 2 | 5.0 |

| Vietnamese | 3 | 7.5 |

| Study population | ||

| General adult | 63 | 45.7 |

| Women only | 29 | 21.0 |

| Men only | 4 | 2.9 |

| Children and/or adolescents | 14 | 10.1 |

| Older adults | 3 | 2.2 |

| Health workers | 7 | 5.1 |

| Other/not specified | 18 | 13.0 |

Percentages sum up to more than 100% because some studies included more than one study population

Percentages of each ethnicity represent the percent out of the total number of refugee study populations

Publications were classified into several population categories, including n=63 (45.6%) publications that involved general adult populations of mixed sex, n=29 (21.0%) that only included women in the samples, and n=14 (10.2%) that focused on children and adolescents. The other studies involved men only (n=4, 2.9%), older adults (n=3, 2.2%), health workers (n=7, 5.1%) and other or not specified (n=18, 13.0%; Table 1). Publications that focused on descriptions of idioms by health workers included traditional healers, community health workers, and homecare workers. Table 2 shows the “thinking too much” idioms used across cultural settings.

Table 2.

Idioms used for “thinking too much” across cultural settings

| Setting | Idiom | Translation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

AFRICA

| |||

| Congolese refugees in Tanzania | Kichwa na kinajaa na mawazo | Thinking too much (literally “my head is full of thoughts”) | Mann, 2010 |

| Eritrea | Ĥasab | Thinking too much | Almedom et al. 2003 |

| Ghana | Taamebubasugbor | Thinking too much | Avotri & Walters, 1999; Avotri 1997; Avotri & Walters, 2001 |

| Kenya | Jachir | Thinking too much | Ice and Yogo 2005 |

| Malawi | Kuganiza kwambiri | Too much thinking | Peltzer, 1989 |

| South Sudan | Par keter | Thinking too much | Ventevogel et al., 2013 |

| Uganda | Alowooza nyo | Thinking a lot | Muhwezi et al., 2008 |

| Zimbabwe | Kufungisisa | Thinking too much | Abas et al., 2003; Abas et al., 1994; Abas & Broadhead, 1997; Chibanda et al., 2010; Chibanda et al., 2011; Patel, 1995; Patel et al., 1995a; Patel & Mann, 1997; Patel et al., 1995b; Winston & Smith, 2000 |

|

| |||

|

ASIA

| |||

| Cambodia | Kut careen, keut chreun | Thinking too much | Hinton et al., 2012b; Meyer et al., 2014 |

| Indonesia | Kepikiran | Thinking too much | Andajani-Sutjahjo et al., 2007 |

| Indonesia | Ma-‘tangna’-tangna’ | Think too much (literally “to think and think”) | Hollan & Wellenkamp, 1994 |

| Laos | Khut Lāi | Thinking too much | Westermeyer, 1979 |

| Malaysia | Banyak fikir | Thinking too much | Abdul Kadir & Bifulco, 2010 |

| Thailand | Kaankhitmaak | Thinking a lot | Muecke, 1994 |

|

| |||

|

AUSTRALIA/PACIFIC ISLANDS

| |||

| Australia | Kulini-kulini | Too much thinking | Brown et al., 2012 |

| Papua New Guinea | Tingting planti | Thinking too much | Hinton & Earnest, 2010 |

| Timor-Leste | Hanoin barak | Thinking too much | Le Touze et al., 2005; Sakti, 2013 |

|

| |||

|

CENTRAL/SOUTH AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN

| |||

| Haiti | Kalkile twòp | Thinking too much | Rasmussen et al., 2015 |

| Haiti | Maladi kalkilasyon | Thinking too much (literally “thinking/calculating sickness”) | McLean et al., 2015 |

| Haiti | Panse anpil | Thinking too much | Bolton et al., 2012 |

| Haiti | Reflechi twòp | Thinking too much | Kaiser et la., 2013; Kaiser et al., 2015; Kaiser et al., 2014; Keys et al., 2012; Khoury et al., 2012 |

| Nicaragua | Pensando mucho | Thinking too much | Yarris, 2011a; 2011b; 2014 |

|

| |||

|

NORTH AMERICA AND EUROPE

| |||

| Cambodian refugees in US | Geut caraeun, kit craen, koucherang, kut caraeun, | Thinking too much | D’Avanzo & Barab, 1998; D’Avanzo et al., 1994; Frye & D’Avanzo, 1994a; Frye & McGill, 1993; Frye, 1995; Frye & D’Avanzo, 1994b; Hinton et al., 2012a; Hinton et al., 2013a; Hinton et al., 2001a; Hinton et al., 2001b; Hinton et al.., 2012b; Hinton & Otto, 2006; White, 2004 |

| Mexican immigrants in US | Anda pensando | Too much thinking | Lackey, 2008 |

| Thai immigrants in US | Kid-mak | Thinking too much, persistent thinking | Soonthornchaiya & Dancy, 2006 |

| Vietnamese immigrants in US | Nghi nhieu qua | Thinking too much | Merkel, 1996; Yeo et al., 2002 |

Note: Many publications discussed “thinking too much” but did not provide the idioms in the local language. This table only includes translations of full idioms provided in publications

Aim 2. Comparative description

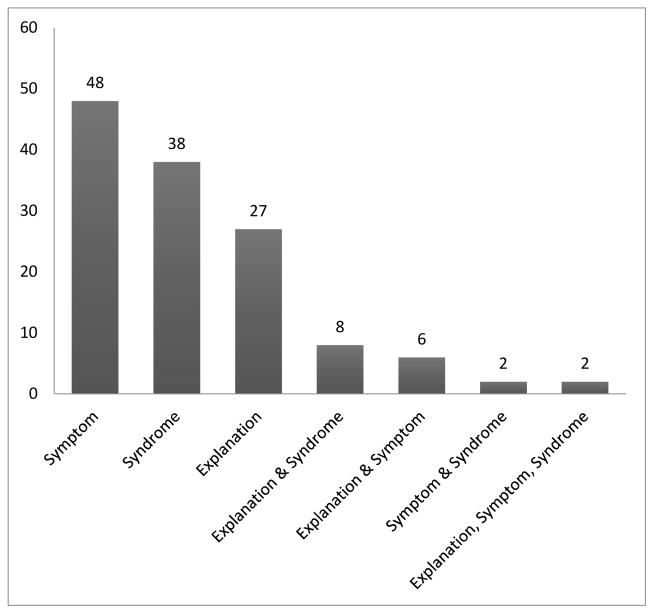

“Thinking too much” as symptom, syndrome, and cause

“Thinking too much” idioms were analyzed as symptoms, syndromes, and/or causes of distress, depending on the particular cultural and social context. Symptoms were defined as individuals’ reports of their subjective experience; syndromes were defined as the co-occurrence of a group of symptoms that together form the presence of a disease/disorder; and causes were considered to be when individuals attributed their illnesses to “thinking too much” (Burgur & Neeleman, 2007). These categories were not mutually exclusive; publications could be classified as invoking “thinking too much” in relation to symptom, syndrome, and cause. There were n=48 (34.8%) publications in which “thinking too much” was primarily used as a symptom of a broader mental health syndrome. For example, as Shankar et al. (2006) describe, “The impact of mental illness was seen on the patient through psychological and behavioral symptoms […] such as thinking too much” (p. 226). Similarly, Okello et al. (2012) found that “the most common singular symptom used by participants to characterize depression was rumination about worries or ‘having too many thoughts” (p. 42).

In n=38 (27.5%) publications “thinking too much” was discussed as itself a mental health related syndrome, or a certain elaborated constellation of symptoms. For example, Bolton et al. (2012) found “thinking too much” described as a syndrome: Moun yo panse anpil (people think a lot), which included symptoms related to difficulty sleeping, chin on palm, and loss of weight/appetite. Baganda men in Uganda also used “thinking too much” as a syndrome when they described what happened after wives leave: “He says ‘I will never have her again’ so he develops the illness of the thoughts as they say… He is thinking a lot” (Okello & Ekblad, 2006, 297).

There were n=27 (19.6%) publications in which “thinking too much” was used as an explanation/cause of either a physical or other mental health problem. In 18 publications (13.0%), “thinking too much” was used in multiple manners (e.g. as a symptom and an explanation/cause; see Figure 2). Of these n=18 publications; n=8 publications used “thinking too much” as an explanation/cause and syndrome, n=6 as an explanation/cause and symptom, n=2 as a syndrome and symptom, and n=2 as all three. In studies involving Southeast Asia populations, “thinking too much” was frequently used as a syndrome (n=19 publications, 46.3% of SE Asia), followed by use as a symptom (n=11, 26.8% of SE Asia) or an explanation/cause (n=10). In studies based in Africa and South Asia, it was used as a symptom (Africa: n=24, 40.0% of Africa; South Asia: n=7, 58.3% or SA) followed by use as a syndrome (Africa: n=14, 23.3%; South Asia: n=1, 8.3%) or an explanation/cause (Africa: n=14, 23.3%; South Asia: n=3, 25.0%). This variability in basic usage and description of “thinking too much” idioms adds complexity to a cross-cultural comparison of such idioms.

Figure 2.

Use of thinking too much in reviewed publications

Content of “thinking too much”

Descriptions of “thinking too much” idioms included characterizations of rumination and intrusive or obsessive thoughts. Apt metaphors likened “thinking too much” to having thoughts move past like a film reel (Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster, 1996) or a cassette tape “going round and round,” machine-like (Yarris, 2014, 489). Other authors likened “thinking too much” idioms to worry or stress. For example, one Quechua man in Peru described such worrying thoughts:

They suffered with pinsamientuwan (worrying thoughts) that they were about to die. Much of their suffering was due to the killing of six of their family members [and] they thought they were about to be killed as well (Pedersen et al., 2010, 287).

The content of thoughts differed across studies. In several instances, “thinking too much” was brought about by an accumulation of life problems, such as in Nicaragua and Ghana and among Shan Buddhists (Avotri, 1997; Eberhardt, 2006; Yarris, 2014). In other cases it consisted of fixation on a single problem, such as in Haiti and among South Asian immigrants in the US (Kaiser et al. 2014; Karasz, 2005a). Similarly, there was variation in whether thoughts centered on only current concerns or also included past events – such as traumatic experiences or death of a family member – such as reported particularly frequently among Cambodian populations (D’Avanzo & Barab, 1998; Frye, 1995; Hinto et al., 2012a; Hinton et al., 2015). Fifteen studies (10.9%) across all world regions linked “thinking too much” idioms to sadness, either as a precipitating factor or as an outcome.

Overall, descriptions suggested that “thinking too much” idioms include phenomena similar to both rumination and worry, with thought content consisting of either present concerns or past experiences, such as trauma, and to a lesser extent future concerns, such as concern for one’s safety.

Symptoms and sequelae of “thinking too much”

Studies reported a range of associated phenomena, including emotional, physiological, and behavioral sequelae of “thinking too much” idioms; forms of functional impairment; and multiple cognitive and somatic symptoms. Across settings, n=21 (15.2% of all studies) associated “thinking too much” idioms with depression-related phenomena including depressed affect, lack of interest in activities, seeming distracted and preoccupied as though one’s mind is elsewhere, and social withdrawal. Such descriptions were found in Sub-Saharan African countries, as well as among Haitians, Inuit, Cambodian refugees, and East Timorese. “Thinking too much” idioms were linked to social isolation and withdrawal in studies from Africa, Haiti, Cambodia, and among Bhutanese and Cambodian refugees in the US. In contrast, a smaller number of studies (n=9, 6.5%) described individuals as having an agitated affect (Thailand: Cassaniti, 2011), being panicky (Zimbabwe: Patel et al., 1995), irritable (South Sudan: Ventevogel et al., 2013), easily angered (Cambodia: Meyer et al., 2014), behaving strangely (Ghana; Avotri, 1997; Avotri & Walters, 2001; Walters et al., 1999), or a combination of these (Cambodian refugees in the US: D’Avanzo et al., 1994; Hinton et al., 2015).

Cognitive sequelae identified in studies included absentmindedness, lack of awareness, and memory loss and were reported particularly among South and Southeast Asian populations and in Sub-Saharan Africa and Haiti. For example, caregivers of depressive patients in Uganda reported that “thinking too much” resulted in poor concentration, diminished problem-solving, and difficulty sustaining conversation (Muhwezi et al., 2008).

Physical sequelae were common across studies (n=42, 30.4%), including tiredness and trouble sleeping (n=25), headache (n=22), and loss of appetite (n=14). A description from Ghana echoes that seen in many studies regarding trouble sleeping: “I think a lot… in the night too when I go to bed, I can’t sleep. I’ll be turning and turning on my bed… I have observed that it is the thinking that is causing all this sleeplessness” (Avotri, 1997, 131). Of the 25 studies reporting trouble sleeping, 14 (56.0%) were from Africa. Of the 22 studies reporting headaches, 10 (45.5%) were from South and Southeast Asian populations. Exhaustion, low energy, and weakness were also reported.

Less common physical symptoms included bodily pains, fever, and more serious sequelae such as chest pain, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, and shortness of breath. Such severe symptoms were reported often among South and Southeast Asian populations, as were reports that “thinking too much” resulted in severe physical disorders like diabetes, heart attack, and stroke. In one study among Turkana women, experience of “thinking too much” was found to be associated with significantly increased salivary cortisol, a hormone that serves as a stress biomarker (Pike & Williams, 2006). Among Cambodians and Cambodian refugees, various physiological and mental disasters were thought to result from “thinking too much,” including insanity, tinnitus, permanent forgetfulness, “dementia,” heart attack, and khyâl attack, a culturally salient syndrome that includes prominent panic-like symptoms such as dizziness, palpitations, and fears of death (Hinton et al., 2012a; Hinton et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2014).

Overall, “thinking too much” idioms appeared to be commonly characterized as consisting of symptoms typically associated with mood and anxiety disorders, with studies rarely reporting psychotic symptoms, such as delusions or hallucinations. “Thinking too much” associated symptomology perhaps suggest locally salient forms of embodied life distress, which can be experienced as more severe in some cultural groups.

Course and functional impairment

Publications included reports of functional impairment associated with “thinking too much,” including impaired social functioning, lack of ability to work, and difficulty competing daily tasks. One participant in Uganda described the link between physical symptoms associated with “thinking too much” and resulting functional outcomes: “I feel pain in all parts of my body. My body is so weak; feel pain in all my bones! I am thinking all the time that I am not able to do even the small things that I would otherwise do” (Okello et al., 2012, 41). These forms of functional impairment did not exist in isolation but often co-occurred. For instance, Muhwezi and colleagues (2008) describe the far-reaching impacts of “thinking a lot” across multiple domains:

Symptoms associated with thinking a lot or worrying too much, such as slowness in activity, poor concentration, and persistent fatigue were reported to affect the economic output of the patient. Patients’ inactivity was reported to result in loss of income, which presented hardships to the family. In some cases, family structure and aspects of family functioning like composition, decision making, social interaction, and access to health care had been fundamentally affected by the illness of a family member. (p. 1108)

In terms of course, “thinking too much” idioms were in several instances seen as spectrums, with potential progression to psychosis or other severe conditions (Kirmayer et al., 2009; Le Touze et al., 2005; Pedersen et al., 2010; Sakti, 2013; van de Put & Eisenbruch, 2004). A more common finding (n=19, 13.8%) was that “thinking too much” can result in more severe mental disorder, typically referred to as “craziness,” “madness,” “insanity” or an equivalent local idiom. Such findings were reported most often in Southeast Asian populations (n=10) and the Caribbean (n=3). In two cases, “thinking too much” idioms were thought to contribute to dementia among Bhutanese and Vietnamese populations living in America (Chase, 2011; Yeo et al., 2002). One study reported that among the Inuit, “thinking too much” is sometimes associated with delusions or hallucinations (Kirmayer et al., 2009). In 14 studies (10.1%) across multiple locations, “thinking too much” idioms were believed to potentially result in death, including through suicide. For example, Goodman (2004) describes how Sudanese refugees encouraged each other to suppress thoughts in order to evade death:

Sometimes it was very hard. Whenever I heard about something new it gave me a sickness. Somebody might come and comfort you. They tell you “don’t think about it.” They tell you to forget those things so that you may live. […] If you keep something in your heart you can die of thinking […] So we did this, and that’s how life went. And if they hadn’t advised me, maybe I would have lost my hope and then died also because of thinking those thoughts. (p. 1185)

“Thinking too much” idioms appeared to have a range of associated outcomes, including other physical and mental health syndromes and disorders and even death.

Etiology

As suggested by the variability in thought content associated with “thinking too much,” perceived etiology of the idioms also differed. It should be clarified that the cause of “thinking too much” may be some combination of having misfortunes to think about or having a mental or physical problem that predisposes to “thinking too much.” In the next section we consider vulnerability.

Approximately one-third (n=53, 38.4%) of publications referenced one or more causes for “thinking too much.” A relatively large range of factors were reported to cause “thinking too much.” The most common causes were troubled social relationships (n=37, 69.8% of publications referencing causes), economic concerns and structural barriers (n=36, 67.9% of causes), adverse past events (n=29, 54.7% of causes), and illnesses (n=16, 49.1% of causes).

Participants attributed “thinking too much” to a range of social relationship problems. Fifteen studies (40.5% of publications referencing social causes), most of them in Africa, focused on “thinking too much” brought about by a husband’s infidelity, abuse, or lack of support for his wife and children. Several studies in Ghana and Uganda reported “thinking too much” about insecurity in marriage or single parenting (Avotri, 1997; Avotri & Walters, 2001; Okello & Ekblad, 2006). General lack of social support or passing long periods of time alone was also said to cause “thinking too much” in studies from Africa and Southeast Asia (n=14, 37.8% of social causes). Worrying about children’s safety, education, and health, was another common cause (n=15, 40.5% of social causes) across all regions. Several publications involving refugee populations (n=7, 18.9% of social causes) found that the strains of living far from family or losing loved ones were distinctive stressors for this population. Similarly, Yarris (2014) describes problems of “thinking too much” among Nicaraguan women experiencing both worry about their daughters who emigrated and profound feelings of abandonment (Yarris, 2011a).

Economic and structural barriers were also a common cause of “thinking too much.” Publications included references to poverty, lack of food, unemployment, inability to pay for school fees, costs of healthcare, household financial responsibilities, and debts. Such etiologic factors were shared across all world regions. Several publications (n=10, 27.8% of publications referencing economic/structural causes) from various world regions referenced a broader sense of disadvantage, disempowerment, and lack of control brought about by structural inequalities beyond poverty (Australia/South Pacific, Ghana, Haiti, Inuit, Nicaragua, and Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees in the US). For example, Brown and colleagues (2012) found that Australian Aboriginal men describe “thinking too much” and depressive symptoms as caused by:

The pervasive and cumulative impact of chronic stress, the experience of socioeconomic disadvantage, and the down-stream impact of colonisation, through the lived experience of oppression and rapid and severe socio-cultural change […] This was experienced as forced and painful separation from the fundamental essential elements of Aboriginal life and Aboriginal ways of being (p. 103).

A subset of publications mentioned the particular difficulties faced by refugees, including cultural and language differences, marginalization, and lack of ability to pursue a career. Although most etiologic factors in this category were clearly driven by dynamics outside individuals’ control, publications from Haiti, Papua New Guinea, and Thailand reported that it is lack of ability to live up to one’s potential or achieve the life they imagine that proves particularly troubling (Hinton & Earnest, 2010; Kaiser et al., 2014; Muecke, 1994; Yarris, 2014).

Another frequently named cause of “thinking too much” was adverse past events (n=29, 54.7% of causes). These references were particularly common in studies based in Southeast Asia, especially among Cambodian populations who reported ruminating on their experiences during the Pol Pot years (D’Avanzo & Barab, 1998; Eisenbruch, 1992; Frye & D’Avanzo, 1994a; Hinton et al., 2012a; Hinton et al., 2015). Death, particularly of a family member or that occurred suddenly or unexpectedly, also caused “thinking too much” (n=15, 51.7% of publications referencing adverse past events as causes). However, attributing “thinking too much” to adverse past events alone can be an oversimplification. For example, Sakti (2013) explains that a massacre in Timor Leste caused “thinking too much” via ongoing disruption of social relationships and typical channels of reconciliation.

Approximately one-third of publications referencing a specific etiology named illness as an important cause of “thinking too much.” While most of these instances referenced one’s own illness, many participants in African studies reported “thinking too much” about the illness of a parent, child, or other close relative. When a specific illness was named, it was typically HIV/AIDS (n=9, 56.3% of publications referencing illness causes).

In addition to these shared etiologic factors, there were also causes particular to certain studies. These causes ranged from witchcraft and spirits (Abbo et al., 2008; Okello & Ekblad, 2006) to substance abuse (Mains et al., 2013; Muhwezi et al., 2008) and worry about work-related concerns (Muhwezi et al., 2008). One author reported, “People may even ruminate about how they ruminate too much” (Hollan & Wellenkamp, 1994, 177).

Vulnerability factors

Fewer than 10% of studies specifically mentioned sub-populations at greater risk of “thinking too much.” Those that did were largely focused on women as a risk group. This risk was often attributed to financial dependence, oppression, and social status – exposures that make women vulnerable to the primary etiologic factors of “thinking too much.” In one study in Thailand, women were thought to be physiologically prone to “thinking too much” (Muecke, 1994). However, Muecke argues that women are instead vulnerable to such experiences due to their social and gendered positions. While men and wealthy and educated individuals are socialized to practice khit pen meditation – believed to be particularly effective against “thinking too much” – for poor women, this practice is not readily accessible. In various studies, other vulnerable populations included poor, unemployed, less educated, rural, or elderly individuals.

Despite the emphasis on vulnerable sub-populations, Mains (2011) indicates that in Ethiopia it is particularly common among young, urban males. This population has their basic needs met, and – unlike their female counterparts – they are not burdened with household tasks, leaving them with ample free time to ruminate. Few publications adopted such a focus on men, making it difficult to assess whether women are indeed particularly vulnerable or are simply a more common focus of studies. Publications would suggest that the cause of “thinking too much” may vary, suggesting different paths to “thinking too much,” such as poverty, experiencing adverse events in the past, endemic relationship violence, or general livelihood insecurity, and that sometimes all such paths are present in a particular case.

Aim 3: Associated psychiatric constructs

When “thinking too much” was presented in association with psychiatric constructs, the ways that authors arrived at these comparative diagnoses differed widely. These methodological and analytic differences complicate cross-cultural comparison of “thinking too much” idioms to psychiatric categories.

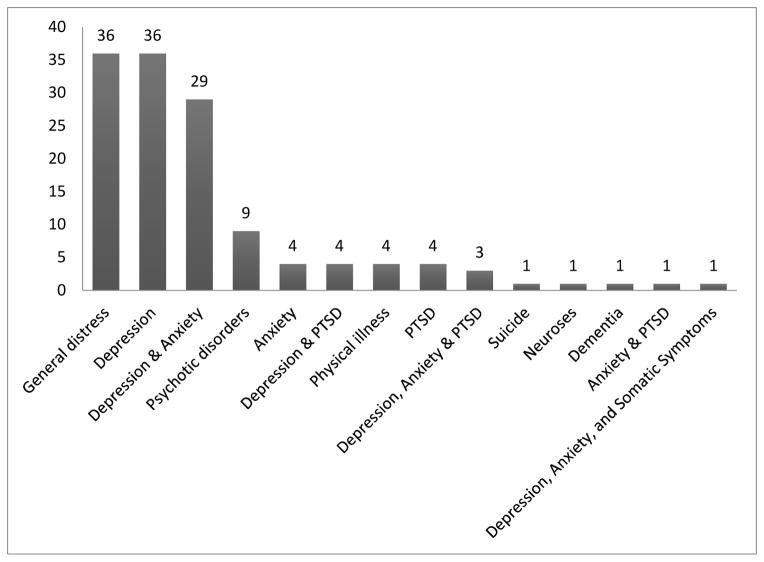

Most studies did not draw on clinical diagnosis or screening instruments but highlighted descriptive similarities between symptoms of “thinking too much” idioms and DSM criteria. Almost all descriptive comparisons were to general distress (n=36, 26.1%) or major depressive disorder (n=36, 26.1%), with authors stressing symptoms such as loss of purpose or self-worth, loss of pleasure, sadness, decreased social interaction, trouble sleeping, and appetite loss (Figure 3). Studies also drew links to anxiety disorders (n=4 generalized anxiety; n=1 generalized anxiety & PTSD; n=39 mix of depression and anxiety disorders; see Figure 3), indicating that “thinking too much” is linked to ruminative worry, panic attacks, and problems thinking and sleeping (Hinton et al., 2013). Rasmussen and colleagues (2011) likened “thinking too much” among Darfur refugees to the rumination or intrusive thoughts characteristic of PTSD. However, several studies highlighted distinctions between “thinking too much” and DSM criteria and advised caution in drawing connections between the two (Lackey, 2008; Okello et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Sakti, 2013). For example, Okello et al. (2012) noted that rumination associated with “thinking too much” was not focused on sad mood or anhedonia as conceptualized in clinical depression.

Figure 3.

Association of thinking too much and psychiatric constructs by publication

Another common way that “thinking too much” was linked to psychiatric diagnoses was through the use of case vignettes. Researchers constructed vignettes to depict DSM disorders, with the aim of eliciting local terminology and etiology. Vignettes that were labeled as “thinking too much” by participants were typically about depression (Abbo, 2011; Karasz, 2005b; Niemi et al., s2010; Okello & Ekblad, 2006; Patel et al., 1995), though vignettes about psychotic depression (Abbo et al., 2008), adjustment disorder with depressed mood (Okello & Ekblad, 2006), somatization (Sorsdahl et al., 2010), and schizophrenia (Sorsdahl et al., 2010) were also sometimes termed “thinking too much.” In other cases, vignettes that were attributed to “thinking too much” were considered not to represent illnesses per se but merely “problems” (Muga & Jenkins, 2008; Sorsdahl et al., 2010).

Other studies indicated that participants themselves related “thinking too much” to depression, though it was often unclear whether this referred to the psychiatric construct or to a more idiomatic expression (Avotri, 1997; Brown et al., 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2009; Yarris, 2014). Martinez et al. (2011) note that Latino immigrants in the US often named “thinking too much” as a symptom of depression, while Hunleth (2011) found that in Zambia “thinking too much” is thought to lead to depression. Fenton and Sadiq-Sangster (1996) report that among South Asian women in Britain, few of their participants used the term depression, sometimes indicating that it was a term that doctors used.

Approximately one-fifth of studies involving a comparison to psychiatric diagnoses used a screening instrument and drew either descriptive or quantitative links to “thinking too much.” For example, participants in Indonesia meeting clinical cut-offs for depression (Andajani-Sutjahjo et al., 2007) or with elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety (Bass et al., 2012) were either locally- or self-identified as experiencing “thinking too much” or described their condition as such. Others found that scores on depression and anxiety screeners were significantly higher among those endorsing “thinking too much” (Kaiser et al., 2015; Patel et al., 1995). Miller and colleagues (2006) found that in a factor analysis of the locally-developed Afghan Symptom Checklist, “thinking too much” loaded strongly on the same factor as depression symptoms such as feeling hopeless, sad, and irritable. Finally, Hinton and colleagues (2012a; 2013; 2015) found “thinking too much” to be one of the best differentiators among three levels of PTSD severity as measured using the PTSD Symptom Checklist.

In the few studies involving participants clinically diagnosed with depression, “thinking too much” was frequently used to describe their illness (Abdul Kadir & Bifulco, 2010; Okello et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2001; Patel & Mann, 1997), was named as a primary cause (Ilechukwu, 1988), or was endorsed significantly more by depressed than non-depressed individuals (Rasmussen et al., 2015). Of the studies that named one or more comparative psychiatric diagnoses, approximately one-fifth provided no further explanation or justification for the comparison.

In summary, in the majority of publications in which “thinking too much” was referenced in relation to a psychiatric category, common mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD or general psychological distress were most frequently mentioned (n=36 publications, 73.5% of publications referencing psychiatric category). In n=9 publications (18.6%), “thinking too much” was associated with a serious psychiatric condition or psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or psychosis. In n=38 publications (77.6%), the idiom was associated with multiple, comorbid psychiatric constructs. However, it is difficult to compare across studies, as evidence brought to bear on these associations differed widely, and most were based on authors’ descriptive comparisons.

Aim 4: Treatment and coping

“Thinking too much” in the context of cultural ideals and ways of coping

Several authors described perceptions of “thinking too much” as situated within a particular worldview of ideal or valued states of mind, which is relevant for understanding treatment and coping. For example, Yarris (2014) argues that “thinking too much” reflected a failure to achieve the moral ideal of solidarity. Additionally, publications reported that people should have control over their thoughts; those who do not are considered weak. The majority of such studies were based on Southeast Asian populations, with frequent reference to Buddhist principles to explain such views. Those who experience “thinking too much” were often regarded negatively, as being spiritually weak, unskilled at decision-making, and overly serious (Cassaniti, 2011; Eberhardt, 2006; Merkel, 1996). For example, Merkel describes how “thinking too much” was situated in a broader value system among Vietnamese refugees in the United States:

The cultural ideal of spiritual and psychological well-being is the ability to maintain stoic equanimity in the face of adversity, to act virtuously and unselfishly, controlling one’s passions and emotions […] The complaint of nghinhieu qua, “thinking too much,” is therefore a serious complaint, implying loss of ability to maintain internal harmony (Merkel, 1996, 1272).

“Thinking too much” was also viewed as being discouraged in Buddhism because it represents a form of attachment and an attempt to control one’s karma. Rather, individuals should strive for acceptance of one’s fate, mortality, and impermanence (Lewis, 2013). In fact, Hinton and colleagues argue that among Cambodian refugees, “thinking a lot” is the appositive of the Buddhist ideal of focused mind characteristic of mindfulness and meditation. Eberhardt (2006) reports a similar viewpoint among Shan Buddhists: reflecting on broader cosmology and one’s impermanence was encouraged, whereas thinking about specific, local problems was problematic. A final reason that “thinking too much” was particularly discouraged in these populations was a belief regarding one’s relation to others: it is believed that everyone suffers, so one should not talk about his/her specific problems (van de Put & Eisenbruch, 2004).

While “thinking too much” was often stigmatized in populations centered on Buddhist moral tenets, in other settings the idiom was considered less stigmatizing than certain other mental disorders (Eberhardt, 2006; Le Touze et al., 2005; Muecke, 1994). In some cases, “thinking too much” represented a potentially valuable locus for intervention before one progresses to more severe – and highly stigmatized – disorder (Chase, 2011; Kaiser et al., 2014), and being visited by a lay health worker for “thinking too much” was considered non-stigmatizing (Chibanda et al., 2011). Such mixed findings demonstrate the importance of situating “thinking too much” and other idioms within their broader ethnopsychological contexts. These examples also contribute to understanding how idioms of distress might help alleviate stigma produced by other forms of mental health communication.

Treatment and coping

Treatments in the form of medication or biomedical therapy were rarely mentioned in relation to “thinking too much.” Several studies reported that medications were believed to be ineffective or that participants were specifically told to stop medication use (Abdul Kadir & Bifulco, 2010; D’Avanzo et al., 1994; Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster, 1996; Hollan & Wellenkamp, 1994). Similarly, whereas some participants reported improvement after visiting a doctor (Bolton et al., 2012; Muhwezi et al., 2008), other studies included local perceptions that medical care is unnecessary or inadequate or that mental healthcare is highly stigmatized and thus avoided (Frye & D’Avanzo, 1994b; Yarris, 2014). When treatment was suggested among lay participants, it typically included symptom management, such as taking sleeping pills and pain killers. In Uganda, anti-depressants were found to decrease participants’ experience of “thinking too much” (Okello et al., 2012).

Rituals, teas, and traditional medicines were in some studies reported as preferred treatment modalities (Abbo et al., 2008; Muecke, 1994; Sakti, 2013; White, 2004). Westermeyer (1979) describes Lao ceremonies to retrieve lost souls that were performed “just in case” of supernatural causation; however, these ceremonies were ultimately seen as ineffective because they did not result in recovery.

Efforts to engage in culturally appropriate coping strategies were specified in approximately one-quarter of studies. The most frequently cited coping strategy – referenced in over half of these studies – was to control or suppress one’s thoughts. In particular, several studies reported prescriptions against thinking about the dead or potential problems, as such thoughts are believed to bring trouble on oneself or others (Avotri, 1997; Eberhardt, 2006; Nepveux, 2009). Although commonly named, it was unclear how effective this technique was. For example, Goodman (2004) reports that Sudanese refugees in the US avoided short-term problems by suppressing thoughts of traumatic events, but this was not seen as an effective long-term strategy. Similarly, one participant compared the suggestion to avoid troubling thoughts to being told “don’t be ill, stop being ill” (Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster, 1996, 76). Other suggestions focused on calming oneself, whether through meditation, relaxation, or quiet time to work through one’s problems.

One-third of the studies included reports that alone time only exacerbated “thinking too much.” Instead, participants preferred to busy themselves through activities and social interaction. Although a small number of studies reported use of substances (e.g. alcohol, khat, and other street drugs) to distract oneself from life problems or pass the time (Avotri, 1997; Bolton et al., 2012; Mains et al., 2013), other studies specifically reported taboos against the use of alcohol and drugs by individuals who are “thinking too much” (D’Avanzo et al., 1994; Frye & D’Avanzo, 1994a; Frye & McGill, 1993).

Seeking out social support from family or community members was recommended by participants in approximately 60% of studies. Talking about their problems or receiving informal counseling and advice was beneficial. Caregivers reported providing encouragement and laughter more so than specific advice. Seeking out religious leaders, such as pastors, Buddhist monks, or church prayer groups, was reported across many settings but was a particularly common recommendation in studies in Uganda. Okello and Ekblad (2006) argue that being prayed over in a communal church setting specifically helped counteract the social isolation typical of “thinking too much.” Others reported that trusting in God and attending to one’s spiritual needs were beneficial, whether in a social capacity or not. Two cases reported that being around community members is helpful, but actually talking about problems can be harmful, as it can bring misfortune to others (Nepveux, 2009; Roberts et al., 2009).

In just under one-fifth of studies, participants stated that the only way to improve “thinking too much” is to address the underlying causes; for example, improvements would only come about through resolving life problems, such as having employment, improved healthcare, resolution of ongoing war, and other improvements in sociopolitical conditions. Indeed, in one study in Haiti (Kaiser et al., 2014), coping strategies focused on distraction were perceived to be successful only for those without enduring economic problems. Yarris (2014) also found that “thinking too much” – linked as it is to immutable, troubling socio-economic arrangements – was seen as chronic unless circumstances changed.

In summary, several coping strategies were commonly perceived as effective across studies, including controlling or suppressing thoughts, distraction, and engaging in social activities, and social support was found to be important in a majority of studies.

Discussion

Summary of findings

The specific aims of this review were to (1) provide an overview of the geographical areas and study populations where “thinking too much” has been studied; (2) describe the phenomenology, course, and vulnerability factors associated with these idioms; (3) examine comparisons of “thinking too much” to DSM disorders; and (4) characterize local forms of coping with “thinking too much.” We found that in general “thinking too much” idioms are used across all major world regions. “Thinking too much” idioms typically referenced rumination, worry, and/or intrusive thoughts, though content of thoughts varied widely both across and within settings. Symptoms associated with these idioms most commonly included social isolation/withdrawal, depressed mood, lack of interest, absentmindedness, memory loss, poor concentration, tiredness, sleep problems, headaches, loss of appetite, and impaired ability to function in work and family life. Perceived etiology included social relationships, economic and structural barriers, traumatic events, and illnesses. Women were commonly identified as being more likely to experience “thinking too much” and its related sequelae. “Thinking too much” was often studied in comparison with depression, as well as anxiety and PTSD. However, the varied methodological approaches taken by authors in drawing such comparisons complicate cross-study comparison. Finally, the most commonly mentioned coping strategy was controlling or suppressing thoughts, and seeking social support was widely recommended. Formal treatments or medications for “thinking too much” have rarely been studied.

Idioms of distress and their implications

“Thinking too much” overlaps with symptoms represented in European/North American psychiatric nosology, such as rumination, perseveration, and worry. However, neither within nor across cultures did “thinking too much” idioms function as synonymous with a single psychiatric construct. Indeed, our findings suggest that there is potential harm associated with reducing these idioms to a single, closest psychiatric diagnosis. In our review, “thinking too much” idioms were found to more saliently communicate distress, as they reference locally meaningful ethnopsychological constructs, value systems, and social structures. In fact, Hinton and colleagues (2015a) argue that “thinking a lot” better predicts PTSD than individual DSM-5 symptoms: “Thus, not assessing “thinking a lot” among Cambodian refugees and other populations results in poor content validity for the trauma construct” (p. 13).

Furthermore, whenever “thinking too much” and psychiatric terms were discussed in relation to stigma, the idioms were considered less stigmatizing. Such findings suggest that drawing on “thinking too much” idioms – rather than displacing them with psychiatric constructs – could prove beneficial for stigma reduction, clinical communication, and therapeutic intervention. “Thinking too much” idioms and psychiatric diagnoses appear to perform different functions within health systems; idioms have great potential for social and communicative aspects of health exchange but not diagnostic specificity. Similarly, psychiatric diagnoses ideally serve the purpose of reliable and accurate identification of distress and selection of treatment regimens, but psychiatric labels have significant limitations with regard to health communication in global mental health.

Several of the studies in this review suggest that there are particular benefits to combining emic (e.g. idioms of distress) and etic (e.g. DSM) perspectives in mental health communication and measurement. Research from a psychiatric epidemiologic approach has demonstrated the utility of DSM categories for measuring the burden of psychiatric illness around the world, such as in the Global Burden of Disease studies (Murray, et al., 2013). Such research can contribute to building an evidence base for global mental health, facilitate cross-cultural communication about prevalences and areas of need, and substantiate calls for increased attention and funding for mental health. At the same time, utilizing a purely etic approach and overlooking local idioms of distress can underestimate local burden of disease and impose the assumption that European/North American concepts of disease and illness are relevant in all contexts (Weaver & Kaiser, 2015).

What has resulted from debates between universalist/particularistic or etic/emic approaches in global mental health has been an attempt to reconcile aims of cross-cultural communication and ethnographic validity via a hybrid approach (Draguns & Tanaka-Matsumi, 2003; Weaver & Kaiser, 2015). This approach recognizes that although symptoms and syndromes in the DSM have been identified in many cultures around the world, it is crucial to examine the local shaping and presentation of distress and disorders (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, 2011; Simons & Hughes, 1985), ultimately recognizing that measurement and communication that draw on both etic and emic categories can achieve complementary goals. Researchers have used such a hybrid approach to develop and adapt locally relevant assessment instruments for use in epidemiological and clinical studies, to facilitate clinical communication, and to guide decisions regarding appropriate treatments and programs (Betancourt, et al., 2009; Haroz, et al., 2014; Hinton, et al., 2012a, b; Kaiser et al., 2013; Kaiser et al. 2015; Kohrt, et al., 2011; Verdeli, et al., 2008).

Idioms of distress have often been key to these emic/etic approaches to bolstering clinical communication and measurement. For example, Miller and colleagues (2006) used “quick ethnography” to develop the Afghan Symptom Checklist (ASCL), which drew on idioms of distress including “thinking too much.” Rasmussen and colleagues (2014) then compared the locally-developed ASCL to the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20). They found that the SRQ-20 failed to capture aggression and dysphoria, elements of mental distress that were particularly locally salient. Additionally, salience of the measures differed by gender. Including emic measures alongside established cross-cultural tools thus provided a more holistic, locally salient approach to assessing distress. Similarly, Hinton and colleagues (2012a, b, 2013, 2015) found “thinking a lot” to be a key domain of evaluation and treatment among Cambodian refugees and thus advocate incorporating the idiom into routine screening and intervention.

Idioms of distress communicate powerfully in part because they draw on shared understandings of ethnopsychology, cultural history, and linguistic meaning systems. For example, in a study about South Asian women in Britain, the term “thinking and thinking” is almost always accompanied by references to dil (the heart). This idiom thus communicates the centrality of the heart-mind to interconnected thoughts and feelings, distinguishing “thinking and thinking” from everyday thoughts (Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster, 1996). Other studies of South Asian populations have similarly related “thinking too much” to the heart-mind, which contrasts with cognitive-emotional processes that are centered in other aspects of ethnophysiology (Desjarlais, 1992; Kohrt et al., 2008). Other authors indicate that “thinking too much” idioms linguistically communicate something other than typical, everyday thoughts. Weiss (2005) describes the term mawazo as indicating active, embodied thought, with similar terms existing in Amharic, Haya, and Swahili (Mains, 2011; Weiss, 2005). Such linguistic and ethnopsychological significance would suggest that there is value in preserving idioms of distress in clinical and public health communication.

At the same time, because “thinking too much” idioms – like other idioms of distress – can communicate suffering that is non-pathological, they should not be taken to imply a need for mental health treatment in all cases. For example, in her examination of pensando mucho (thinking too much) in Nicaragua, Yarris (2014) found that the idiom communicates a certain moral ambivalence in the context of transformed social lives. Yarris’s broader study (2011b) explored experiences of grandmothers caring for their migrant daughters’ children. While on the one hand appreciative of economic remittances, grandmothers nevertheless struggled with both persistent worry regarding daughters’ safety, as well as feelings of abandonment, judging the remittances to be “morally insufficient to make up for mothers’ absences” (Yarris, 2014, 481). Ultimately, their experiences of “thinking too much” and its embodiment as dolor de celebro (brainache) reflect failure to achieve moral ideals of unity and solidarity within the family. In a similar vein, Sakti’s (2013) study of “thinking too much” in Timor-Leste suggests that psychiatric intervention would be insufficient. She describes that biomedical practitioners often interpret hanoin barak (thinking too much) as a reaction to traumatic events, in particular the 1999 Passabe massacre. However, in her ethnographic study, she finds that “thinking too much” is driven not by individual traumatic events but by the disruption of typical channels of communication and reconciliation among closely related kin groups, which produces ongoing social rupture. In this case, social interventions informed by ethnographic context would likely be more successful than individual psychiatric treatment aimed at PTSD. Like other anthropological studies of idioms of distress, Yarris and Sakti’s extended examinations of “thinking too much” in socio-cultural and political perspective reveal the broader significance that is being communicated, yet is potentially missed, invalidated, or even exploited through the adoption of narrower psychiatric interpretation and response. Investigation of “thinking too much” idioms should thus remain open to the possibility that they communicate non-pathological distress – including collective social anxiety or symbolic protest (Abramowitz, 2010; De Jong & Reis, 2010; Nichter, 2010; Pedersen et al., 2010) – that would suggest a need for social, political, and economic reform more so than psychiatric intervention.

This review reveals further recommendations regarding what should not be done in global mental health intervention. For example, our findings suggest that categorization into etiology, symptom, and syndrome is likely an artifact of the researcher’s perspective rather than distinct categories of “thinking too much.” For most presentations cross-culturally, “thinking too much” appears to have aspects of all of these but is not reducible to any one categorization. The most problematic label in categorizing thinking too much is “syndrome.” The heterogeneity within and across cultures in interpretation and manifestation of “thinking too much” suggest that it should not be referred to as a “syndrome.” Instead, the flexibility of the term and its context-dependent meaning is what confers the potential for it to be less stigmatizing than psychiatric labels. Similarly, “thinking too much” should not be considered as a cultural gloss for common mental disorders in general or specific depressive, anxiety, or trauma-related disorders. This raises the potential for biomedical reification and pathologizing of what is a general category of distress that ranges from normative experience to severe forms of suffering.

Ultimately, while “thinking too much” might be a starting point for incorporating lessons learned in other cultural contexts into European/North American psychiatry, it is important to recognize that “thinking too much” idioms represents heterogeneous lay categories rather than a single construct. The complexity inherent in these idioms of distress, both within and across contexts, should thus be recognized and preserved.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this systematic review. First, we did not systematically search for non-English language publications or studies in the gray literature, which could have yielded a larger number of studies from a wider range of study settings. We also excluded closely-related idioms such as “brain fag,” “excessive thinking,” “over thinking,” and other idioms related to boredom and studying (e.g. Durst et al., 1993; Ferzacca, 2002; Fisher, 1985; Jervis et al., 2003; Ola et al., 2009; Prince, 1960; Yang et al., 2010). Several publications reported on studies by the same research team, potentially resulting in “double counting” the same reported data. In many of these cases, it was not possible to fully determine whether information came from the same study population due to analyses of subsamples, mixing of qualitative and quantitative samples, and use of illustrative qualitative examples for interpretation of results without specification of the qualitative sample. We have tried to note where suspected “double counting” may have occurred in the supplemental table. Ultimately, because the goal of this review is to provide a qualitative synthesis, we chose to err toward being overinclusive of publications. Moreover, we chose not to conduct inferential statistical analyses, which would have been biased by possible double counting.

In addition, we did not formally establish inter-coder agreement before systematically coding publications. Formal calculations of inter-coder agreement are not always done with qualitative research (Armstrong, Gosling, Weinman & Marteau, 1997), and in some cases discussions between coders, rather than a statistical calculation of agreement, can be most beneficial (Barbour 2001). While the final application of the codes was done independently, the authors worked closely together to develop the codebook, practice coding, and discuss any disagreements in application of codes.

There was wide variability across publications in terms of amount and type of information provided regarding “thinking too much” idioms; for example, only ten percent of studies included any information regarding risk groups. It is thus difficult to determine how representative some elements of our review are in terms of the full range of “thinking too much” idioms. Moreover, information about “thinking too much” arose differently across studies: some authors elicited information about “thinking too much,” while in others, “thinking too much” idioms arose organically during general discussion of mental distress. Such differences in data collection strategies make it difficult to compare how significant “thinking too much” idioms are across settings. Moreover, as mentioned above, variation in study methods resulted in a lack of consistency for whether “thinking too much” idioms were defined as symptoms, syndromes, or causes. However, as indicated above, such variation in part reflects the complexity of these idioms, which cannot be reduced to a single, homogenous construct.

We call for future research that examines “thinking too much” idioms in a more rigorous and nuanced way, with attention to distinguishing potentially pathological forms of suffering that might require clinical intervention from non-pathological forms of distress that might call for other types of intervention. In addition, we suggest attending to whether certain population sub-groups are considered particularly vulnerable to “thinking too much.” Ethnographic research is informative here because it facilitates the identification of cultural concepts of distress that communicate the complex etiology, meaning, and response surrounding forms of suffering (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez 2010; Kohrt et al. 2010; Nichter 1981; Rubel 1964). In addition, this initial qualitative synthesis of the literature can provide the foundation for future hypothesis-driven inferential testing of existing studies while keeping in mind potential biases in the literature and limitations for meta-analyses that can be drawn from this qualitative description.

Conclusion

This systematic review found that “thinking too much” idioms of distress are common worldwide and show consistencies in phenomenology, etiology, and effective coping strategies. “Thinking too much” idioms cannot be reduced to any one psychiatric construct; in fact, they appear to overlap with phenomena across multiple psychiatric categories, as well as reflecting aspects of experience not reducible to psychiatric symptoms or disorders, such as socioeconomic vulnerability. Because of the nature of “thinking too much” idioms as something that appears to be both universal in regard to a reflection of distress and also non-specific with regard to any single disorder, they hold great potential to be a less-stigmatizing facilitators of screening, treatment adaptation, psychoeducation, and treatment evaluation. However, recognizing idioms of distress as communicative tools that can reference pathological or non-pathological distress, it is vital to incorporate a locally nuanced understanding of the idiom into potential interventions.

Based on these findings, there are several ways in which considering “thinking too much” and other idioms in their own right can improve mental health outcomes. First, such idioms should be incorporated into measurement and screening, as they provide ideal means of identifying those in need of services, as well as tracking outcomes of treatment that are personally and culturally salient (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2010; Kohrt et al., 2014). Second, such idioms of distress can be used as an entry point for exploring ethnopsychology, which in turn can inform culturally appropriate interventions (Hinton et al., 2012b). For example, numerous successful global mental health trials have shown increased feasibility and acceptability by framing interventions in the context of locally acceptable, non-pathological terms for distress (Patel et al., 2011). Such approaches have shown success in multiple settings (Kohrt et al., 2011; Hinton et al., 2012c). Third, idioms of distress should be incorporated into public health communication and stigma reduction activities in order to enhance understanding, promote treatment-seeking, and avoid unintentionally contributing to stigmatization. And fourth, “thinking too much” should be considered as a treatment target, as it seems to be a central nexus often involving social distress that gives rise to psychological and somatic distress and brings about certain local means of help seeking. However, due in large part to the heterogeneity of “thinking too much” idioms, no single treatment modality is recommended. Future research should explore both clinical and non-clinical forms of treatment, including traditional healing and social interventions, that have successfully addressed “thinking too much.” Ideally, local means of responding to “thinking too much” can be investigated and incorporated into treatment when possible, such as mindfulness meditation in Buddhist contexts (Hinton, et al., 2012b).

“Thinking too much” is an exemplar idiom of distress that has great potential to improve acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of mental health interventions. It is key avenue to understanding local conceptualizations and experiences of distress, and this knowledge can be used to prevent and address general psychological distress, as we have outlined. In cultural contexts where it is found, we advocate “thinking too much” be assessed and tracked in any evaluation or treatment dealing with psychopathology, and that it be incorporated into public health interventions.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Presents first cross-cultural review of the idiom of distress “thinking too much”

“Thinking too much” idioms are nearly universal yet heterogeneous across settings

They reference a range of pathological/non-pathological states, not a single psychiatric construct

They have been used successfully to strengthen measurement scales and clinical interventions

We highlight strong examples of balancing emic and etic approaches to understanding distress

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Craig Hadley for his helpful feedback on an earlier draft. BNK was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (#0234618). BAK was supported by “Reducing Barriers to Mental Health Task Sharing” funded by NIMH (K01MH104310-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbo C, Okello E, Ekblad S, Waako P, Musisi S. Lay concepts of psychosis in Busoga, Eastern Uganda: A pilot study. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review. 2008;3:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Kadir NB, Bifulco A. Malaysian Moslem Mothers’ Experience of Depression and Service Use. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010;34:443–467. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz SA. Trauma and Humanitarian Translation in Liberia: The Tale of Open Mole. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34:353–379. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andajani-Sutjahjo S, Manderson L, Astbury J. Complex emotions, complex problems: understanding the experiences of perinatal depression among new mothers in urban Indonesia. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2007;31:101–122. doi: 10.1007/s11013-006-9040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Avotri JY. Sociology. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University; 1997. “Thinking too much” and “worrying too much”: Ghanaian women’s accounts of their health problems. [Google Scholar]

- Avotri JY, Walters V. ‘We Women Worry a Lot About Our Husbands’: Ghanaian women talking about their health and their relationships with men. Journal of Gender Studies. 2001;10:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7294):1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Poudyal B, Tol W, Murray L, Nadison M, Bolton P. A controlled trial of problem-solving counseling for war-affected adults in Aceh, Indonesia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0339-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. A qualitative study of mental health problems among children displaced by war in northern Uganda. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2009;46(2):238–256. doi: 10.1177/1363461509105815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Surkan PJ, Gray A, Desmousseaux M. The mental health and psychosocial effects of organized violence: A qualitative study in northern Haiti. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49:590–612. doi: 10.1177/1363461511433945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs C, Hallin DC, Hallin DC with Clara Mantini-Briggs. Stories in the time of cholera: Racial profiling during a medical nightmare. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Scales U, Beever W, Rickards B, Rowley K, O’Dea K. Exploring the expression of depression and distress in aboriginal men in central Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger H, Neeleman J. A glossary on psychiatric epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61(3):185–189. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.019430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaniti J. Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago; 2011. Control in a World of Change: Emotion and Morality in a Northern Thai Town. [Google Scholar]

- Chase L. Coping, Healing, and Resilience: A Case Study of Bhutanese Refugees Living in Vermont. Dartmouth: Dartmouth College; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mesu P, Kajawu L, Cowan F, Araya R, Abas MA. Problem-solving therapy for depression and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: piloting a task-shifting primary mental health care intervention in a population with a high prevalence of people living with HIV. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:828. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avanzo C, Barab S. Depression and anxiety among Cambodian refugee women in France and the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1998;19:541–556. doi: 10.1080/016128498248836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avanzo CE, Frye B, Froman R. Stress in Cambodian refugee families. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1994;26:101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JT, Reis R. Kiyang-yang, a West-African postwar idiom of distress. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34:301–321. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais R. Body and emotion: The aesthetics of illness and healing in the Nepal Himalayas. University of Pennsylvania Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Draguns JG, Tanaka-Matsumi J. Assessment of psychopathology across and within cultures: issues and findings. Behaviour research and therapy. 2003;41:755–776. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durst R, Minuchin-Itzigsohn S, Jabotinsky-Rubin K. ‘Brain fag’ syndrome: Manifestation of transculturation in an Ethiopian Jewish immigrant. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 1993;30:223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]