Abstract

Objective

To analyze the association between patient characteristics and the probability of undergoing any uterine-sparing procedure (endometrial ablation, myomectomy, and uterine artery embolization) compared with hysterectomy as the first uterine leiomyoma (index) procedure, and the probability of undergoing a specific uterine-sparing procedure.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis using a commercial insurance claims database containing over 13 million enrollees annually. Based on the index procedure performed 2004–2009, women were classified into one of the four procedure cohorts. Eligible women were aged 25–54 years on the index date, continuously insured through 1-year baseline and 1-year follow-up, and had a baseline uterine leiomyoma diagnosis. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between patient characteristics and leiomyoma procedure.

Results

The study sample comprised 96,852 patients (endometrial ablation=12,169; myomectomy=7,039; uterine artery embolization=3,835 and hysterectomy=73,809). Patient characteristics associated with undergoing any uterine-sparing procedure compared with hysterectomy included health maintenance organization health plan enrollment, Northeast region residence, the highest income and education quintiles based on ZIP-code, an age-race interaction, and baseline diagnoses including menstrual disorders, pelvic pain, anemia, endometriosis, genital prolapse, and infertility. Among those that had a uterine-sparing procedure, characteristics associated with undergoing uterine artery embolization or endometrial ablation compared to myomectomy included increasing age, being from Midwest relative to Northeast, and certain baseline conditions including menstrual disorder, pelvic pain, endometriosis, and infertility.

Conclusion

Both clinical and nonclinical factors were associated with the receipt of alternatives to hysterectomy for uterine leiomyomas in commercially insured women.

Introduction

Uterine leiomyomas are a benign and very common gynecologic condition in reproductive age women, and are associated with significant morbidity including menstrual disorders, anemia, and adverse reproductive outcomes.(1) Evidence is limited regarding comparative effectiveness between existing uterine leiomyoma treatment procedures, and uncertainty remains regarding how different patient characteristics are associated with different procedures.(2) Although hysterectomy is the most commonly performed procedure for uterine leiomyoma treatment, a recent national survey of women found that hysterectomy is the least preferred procedure irrespective of whether they desire future pregnancies.(3)

Better understanding of the factors that influence the probability of undergoing a specific uterine leiomyoma treatment procedure would help deliver patient-centric uterine leiomyoma care. Based on limited data, the authors of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) systematic review identified the evidence gap that exists with regard to how the uterine leiomyoma features and patient risk factors likely influence the operative procedures that patients undergo for uterine leiomyoma treatment.(2, 4) Therefore, the primary aims of this study are twofold: (i) to analyze the association between patient characteristics and the probability of undergoing any uterine-sparing procedures (USPs) [myomectomy, endometrial ablation, and uterine artery embolization] versus hysterectomy as the first uterine leiomyoma treatment procedure; and (ii) among those who underwent a USP, to quantify the patient characteristics that are associated with the specific USP that they choose.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective analysis drew data from Truven’s MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) database. Details of this database have been published (5, 6). Briefly, the CCAE database compiles data from U.S. employer-sponsored private health plans containing medical and drug claims of over 13 million employees and their dependents annually covered under a variety of fee-for-service and capitated health plans. This study includes patients enrolled under comprehensive fee-for-service indemnity plans, exclusive provider organizations (EPOs), health maintenance organizations (HMOs), point-of-service (POS) plans, preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and consumer directed health plan or high deductible health (CDHP or HDHP) plan. Medical claims are linked to deidentified individual enrollment information. Inclusion in the database is contingent on whether or not Truven provided technical infrastructure for administering a particular claim. In that sense, the Truven database is a large convenience sample. Moreover, CCAE database blinds provider identifiers to protect business-sensitive information; as such, the provider type for each patient cannot be assessed. The CCAE database has data from all 50 U.S. states. Geographic regions were defined by census data. Approximately 47% of the patients are from the South, 21% from the Midwest, 19% from the West and 13% from the Northeast., Since the CCAE database primarily collects data from large self-insured employers, the study sample used in the present study may be considered representative of commercially insured patients from large employers in the U.S.. (5, 6) CCAE captures adjudicated health care claims through automated electronic data capture. Within one year of service, the database has a complete record of claims for nearly 99% of cases, with a low risk of error since the claims are closed. (6)

We used 2003–2010 CCAE data for women aged 25–54 with uterine leiomyoma diagnosis (defined as one inpatient claim, or two outpatient claims at least 30 days apart) who had myomectomy, endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization or hysterectomy between 2004 and 2009. The date of the first procedure during the study period (2004–2009) was defined as the index date, and the procedure on the index date defined the corresponding study cohort. Baseline for each patient was defined as the 366-day period ending two weeks prior to the index date. A 2-week period prior to the index date was allowed for pre-operative diagnostic assessments (pre-operative period). All patients were required to have a uterine leiomyoma diagnosis during the baseline, and to be continuously insured during the baseline through the 1-year follow-up including the pre-operative period. The organization of the timeline for the study ensured capture of at least one year of baseline and follow-up data for each patient.

Patients were excluded if they had any uterine leiomyoma-related procedure other than those analyzed in our study between 2003 and the index date, if they had any malignancy diagnosis, or if they became pregnant during the study period.

The first outcome measure was represented by a dichotomous variable indicating whether the patient had a USP or hysterectomy. The second outcome measure was the specific USP that the patient underwent on the index date. (See Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, for the corresponding Current Procedural Terminology or CPT codes.)

Multiple independent variables were captured in the CCAE database. Prior to the analysis, we decided to categorize age on the index date into the following three age categories: 25–34 years, 35–44 years and 45–54 years. The rationale for assessing age effects in these categories was due to the fact that both the likelihood of pregnancy and the likely outcomes of pregnancy are different for the 3 groups: women aged 25–34 years have high fecundity, low risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and those aged 35–44 years have low fecundity, higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Finally, the age group 45–54 years is generally perimenopausal, so reproductive concerns are generally minimal; in addition, since the average menopausal age in the U.S. is 51, therefore we restricted our sample to women of age 54 or below. Baseline comorbidity profile for each patient was captured through the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which was categorized into three categories : CCI =0, CCI=1 and CCI>1, with CCI=0 representing the healthiest patients.(7) Presence of comorbid conditions during the baseline period was captured through dichotomous variables and broadly categorized into three categories: uterine leiomyoma-related conditions, other gynecologic conditions and non-gynecologic conditions. (See Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, for relevant codes) Since baseline inpatient (IP) admission or emergency room (ER) visit may indicate additional patient severity, presence of an all-cause baseline IP and ER admission was reported and adjusted in the multivariate models. Baseline use of prescription-strength non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and hormone therapy as captured in the claims database were also used, which might be used to mitigate uterine leiomyoma symptoms. (See Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, for the detailed list.)

We obtained the socioeconomic characteristics associated with each of the 5-digit ZIP-code residence from the 2000 U.S. Census data, including the percent of black residents, median household income, and percent of residents with a college degree. Quintiles of the distribution of these variables were reported and adjusted in the multivariate models.

Patient characteristics were described by their frequencies and corresponding percentages for the individual study cohorts. Differences in patient characteristics between the study cohorts were assessed by Chi-square test. A logistic regression was used to assess the association between patient characteristics and the probability of a USP versus hysterectomy. The association between patient characteristics and the probability of undergoing a specific USP (uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation or myomectomy) was modeled using a multinomial logistic (MNL) regression model.(8) The MNL framework models log odds of a procedure relative to a reference procedure as a linear function of the independent variables, which can then be used to estimate the relative risk ratio (RRR) of a procedure compared to the reference procedure. The assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives underlying the MNL model was tested through Hausman test.(9) We also tested for potential interactions of race with age, income and education in both the logit and the MNL models. For the interacting covariates, marginal effects (effects on the predicted probability of undergoing a specific procedure) were estimated.(10) In order to correct for multiple tests, the p-values and the 95% confidence intervals in the logit and multinomial logit models were corrected using Bonferroni correction (11). Stata SE 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

Since the study used deidentified data, it was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota.

Results

The final analytic sample had 96,852 patients (myomectomy=7,039 or 7.27%; endometrial ablation=12,169 or 12.56%; uterine artery embolization=3,835 or 3.96%; and hysterectomy=73,809 or 76.21%). (See Appendix 4, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, for details on how the sample size was obtained from the database). The dominant route for myomectomy was abdominal (73.95%), followed by laparoscopic (17.76%), vaginal (6.34%) and others (1.96%). The dominant route for hysterectomy was also abdominal (55.69%) followed by laparoscopic or robotic (23.76%), and vaginal (12.64%); the rest of the hysterectomies did not have information on the routes of hysterectomy (7.91%).

Patient characteristics are provided in Table 1 by uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy as well as by specific uterine-sparing procedures (UAE, EA, and myomectomy). Myomectomy was more common among younger women with 27% and 57% of the women undergoing myomectomy aged 25–34 years and 35–44 years compared to 16% women aged 45–54 years having myomectomy. In contrast, endometrial ablation and hysterectomy were more frequently used by older women, with 53% of women in each cohort aged 45–54 years compared to 43% and 4% of women aged 35–44 years and 25–34 years in the endometrial ablation cohort, and 42% and 5% of women aged 35–44 years and 25–34 years in the hysterectomy cohort(p<0.001). The South had disproportionately more of all of the procedures (between 46% and 56%) than other regions (p<0.001). The percent of patients with baseline CCI=0 ranged from 81% for the hysterectomy cohort to 86% for the myomectomy cohort, indicating an overall healthy cohort. Over 90% of the patients in each cohort were enrolled in PPO, HMO or POS health plans. The thresholds for the quintiles of the ZIP code level variables are provided in Table 1. In general, higher quintiles of the ZIP-code level variables – percent of black residents, median household income, and percent of college graduates – were more likely to undergo a uterine-sparing procedure.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics by Study Cohorts

| Patient Characteristics | UAE N=3,835 (1) | EA N=12,169 (2) | Myomectomy 7,039 (3) | Uterine-Sparing Procedure N=23,043 (4)=(1)+(2)+(3) | Hysterectomy N=73,809 (5) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | ||||||

| 25–34 | 122 (3.18%) | 457 (3.76%) | 1916 (27.22%) | 2495 (10.83%) | 3378 (4.58%) | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 1755 (45.76%) | 5246 (43.11%) | 4034 (57.31%) | 11035 (47.89%) | 31047 (42.06%) | |

| 45–54 | 1958 (51.06%) | 6466 (53.14%) | 1089 (15.47%) | 9513 (41.28%) | 39384 (53.36%) | |

| Geographic Regions | ||||||

| Northeast | 543 (14.16%) | 1464 (12.03%) | 996 (14.15%) | 3003 (13.03%) | 6303 (8.54%) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 709 (18.49%) | 3143 (25.83%) | 998 (14.18%) | 4850 (21.05%) | 17026(23.07%) | |

| South | 2037 (53.12%) | 5573 (45.8%) | 3924 (55.75%) | 11534 (50.05%) | 37851 (51.28%) | |

| West | 546 (14.24%) | 1989 (16.34%) | 1121 (15.93%) | 3656 (15.87%) | 12629 (17.11%) | |

| Comorbidity Status | ||||||

| CCI=0 | 3221 (83.99%) | 10020 (82.34%) | 6080 (86.38%) | 19321 (83.85%) | 59778 (80.99%) | <0.001 |

| CCI=1 | 457 (11.92%) | 1568 (12.89%) | 703 (9.99%) | 2728 (11.84%) | 9140 (12.38%) | |

| CCI>1 | 157 (4.09%) | 581 (4.77%) | 256 (3.64%) | 994 (4.31%) | 4891 (6.63%) | |

| Health Plan Typeb | <0.001 | |||||

| Comprehensive | 146 (3.81%) | 553 (4.54%) | 208 (2.95%) | 907 (3.94%) | 3411 (4.62%) | |

| EPO | 30 (0.78%) | 92 (0.76%) | 72 (1.02%) | 194 (0.84%) | 507 (0.69%) | |

| HMO | 1132 (29.52%) | 2876 (23.63%) | 1775 (25.22%) | 5783 (25.10%) | 15518 (21.02%) | |

| POS | 572 (14.92%) | 1605 (13.19%) | 1097 (15.58%) | 3274 (14.21%) | 10079 (13.66%) | |

| PPO | 1823 (47.54%) | 6588 (54.14%) | 3616 (51.37%)) | 12027 (52.19%) | 41227 (55.86%) | |

| CDHP/HDHP | 83 (2.16%) | 314 (2.58%) | 172 (2.44%) | 569 (2.47%) | 2037 (2.76%) | |

| Race Quintilec | ||||||

| 1 | 10 (0.26%) | 113 (0.93%) | 21 (0.3%) | 144 (0.62%) | 1001 (1.36%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 89 (2.32%) | 941 (7.73%) | 180 (2.56%) | 1210 (5.25%) | 5737 (7.77%) | |

| 3 | 492 (12.83%) | 2435 (20.01%) | 841 (11.95%) | 3768 (16.35%) | 13870 (18.79%) | |

| 4 | 1149 (29.96%) | 4378 (35.98%) | 2105 (29.9%) | 7632 (33.12%) | 24238 (32.84%) | |

| 5 | 2095 (54.63%) | 4302 (35.35%) | 3892 (55.29%) | 10289 (44.65%) | 28963 (39.24%) | |

| Income Quintiled | ||||||

| 1 | 317 (8.27%) | 804 (6.61%) | 679 (9.65%) | 1800 (7.81%) | 7017 (9.51%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 323 (8.42%) | 1272 (10.45%) | 688 (9.77%) | 2283 (9.91%) | 9964 (13.5%) | |

| 3 | 606 (15.8%) | 1961 (16.11%) | 1157 (16.44%) | 3724 (16.16%) | 13908 (18.84%) | |

| 4 | 748 (19.5%) | 2641 (21.7%) | 1542 (21.91%) | 4931 (21.4%) | 16678 (22.6%) | |

| 5 | 1841 (48.01%) | 5491 (45.12%) | 2973 (42.24%) | 10305 (44.72%) | 26242 (35.55%) | |

| Education Quintilee | ||||||

| 1 | 139 (3.62%) | 453 (3.72%) | 260 (3.69%) | 852 (3.7%) | 3439 (4.66%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 285 (7.43%) | 1243 (10.21%) | 558 (7.93%) | 2086 (9.05%) | 9520 (12.9%) | |

| 3 | 572 (14.92%) | 2106 (17.31%) | 1099 (15.61%) | 3777 (16.39%) | 14882 (20.16%) | |

| 4 | 862 (22.48%) | 3085 (25.35%) | 1703 (24.19%) | 5650 (24.52%) | 18853 (25.54%) | |

| 5 | 1977 (51.55%) | 5282 (43.41%) | 3419 (48.57%) | 10678 (46.34%) | 27115 (36.74%) | |

| Baseline uterine Leiomyoma-related Conditions | ||||||

| Menstrual Disorders | 2164 (56.43%) | 9744 (80.07%) | 3140 (44.61%) | 15048 (65.3%) | 40134 (54.38%) | <0.001 |

| Pelvic Pain | 910 (23.73%) | 2768 (22.75%) | 2281 (32.41%) | 5959 (25.86%) | 23062 (31.25%) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1093 (28.5%) | 2801 (23.02%) | 1395 (19.82%) | 5289 (22.95%) | 13188 (17.87%) | <0.001 |

| Urinary Problems | 128 (3.34%) | 303 (2.49%) | 281 (3.99%) | 712 (3.09%) | 2585 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| Constipation or Gas | 106 (2.76%) | 309 (2.54%) | 224 (3.18%) | 639 (2.77%) | 2126 (2.88%) | 0.061 |

| Baseline Other Gynecologic Conditions | ||||||

| Endometriosis | 83 (2.16%) | 264 (2.17%) | 344 (4.89%) | 691 (3%) | 3367 (4.56%) | <0.001 |

| Disorders of Uterus (unclassified) | 753 (19.63%) | 1860 (15.28%) | 975 (13.85%) | 3588 (15.57%) | 11266 (15.26%) | <0.001 |

| Genital Prolapse | 19 (0.5%) | 101 (0.83%) | 49 (0.7%) | 169 (0.73%) | 2872 (3.89%) | <0.001 |

| Benign Neoplasm of the Uterus or Ovary | 3 (0.08%) | 28 (0.23%) | 38 (0.54%) | 69 (0.3%) | 354 (0.48%) | <0.001 |

| Infertility | 36 (0.94%) | 54 (0.44%) | 644 (9.15%) | 734 (3.19%) | 354 (0.48%) | <0.001 |

| Baseline Non-gynecologic Conditions | ||||||

| Inflammatory Disease | 530 (13.82%) | 1464 (12.03%) | 1306 (18.55%) | 3300(14.32%) | 8552 (11.59%) | <0.001 |

| Non-inflammatory Disease | 533 (13.9%) | 2139 (17.58%) | 1238 (17.59%) | 3910 (16.97%) | 13916 (18.85%) | <0.001 |

| Any Inpatient Admission | 190 (4.95%) | 555 (4.56%) | 291 (4.13%) | 1036 (4.5%) | 4151 (5.62%) | <0.001 |

| Any Emergency Room Admission | 789 (20.57%) | 2581 (21.21%) | 1618 (22.99%) | 4988 (21.65%) | 16290 (22.07%) | 0.004 |

| Any NSAID Use | 1056 (27.54%) | 3336 (27.41%) | 1757 (24.96%) | 6149 (26.68%) | 19889 (26.95%) | 0.001 |

| Any Hormone Use | 1199 (31.26%) | 4522 (37.16%) | 2782 (39.52%) | 8503 (36.9%) | 23552 (31.91%) | <0.001 |

Note: UAE=Uterine Artery Embolization; EA=Endometrial Ablation.

Based on Chi-squared tests comparing UAE, EA, myomectomy and hysterectomy.

Percentages do not add up to 100 because there are approximately 1% missing observations for this variable.

Quintile of % black in ZIP code, 2000 Census:1=0% black; 2=0.1%–0.3%; 3=0.4%–1.3%; 4=1.4%–8.5% black, 5= ≥8.6%

Quintile of median income in ZIP code, 2000 Census: 1=$0–$28,280; 2 = 28,281-$33,680; 3=$33,681-$39,204; 4=$39,205-$48,749 ; 5=≥$48,750

Quintile of % with college degree in ZIP code, 2000 Census, Quintiles assigned so equal number of ZIP Codes in each quintile: 1=lowest values, 5=highest values: 1 = 0%–7% with college degree, 2 = 8%–11%, 3=12%–15%, 4=16%–24% and 5= ≥25%

Women in each of the procedure groups significantly differed for all uterine leiomyoma-related symptoms, except for constipation or gas (Table 1). Prevalence of menstrual disorders ranged from 45% for myomectomy patients to 80% for endometrial ablation patients. Among the treatment groups, the prevalence of pelvic pain ranged between 23–32% and anemia ranged from 18% to 29%. Baseline infertility was highest for the myomectomy cohort at 9%, and less than 1% for the other cohorts (p<0.001).

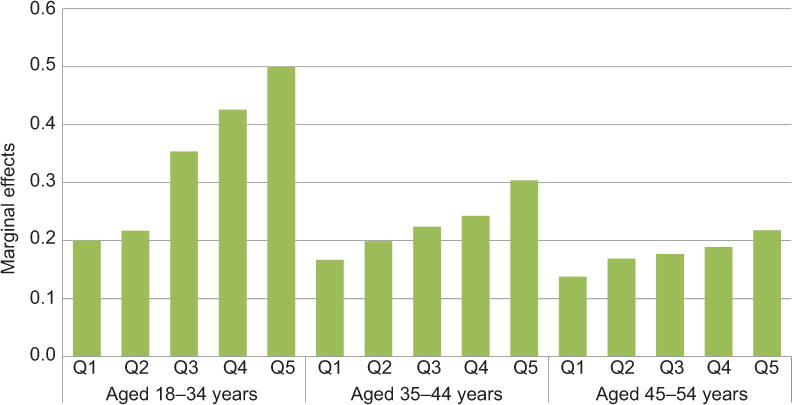

Table 2 presents odds ratios associated with each patient characteristic included in the logistic regression that modeled the probability of uterine-sparing uterine leiomyoma procedure versus hysterectomy. Although the odds ratios associated with the interaction of race and age were not significant, it was the marginal effects of the interaction terms that provided the relevant information on the effects of interactions on the probability of undergoing USP versus hysterectomy. (10) As seen from Figure 1 and Appendix 5 (Appendix 5 is available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx), the marginal effects for race-age interaction indicate that women from the two younger age groups (25–34 years and 35–44 years) were more likely to undergo a USP than older women (45–54 years), and this likelihood increases as the proportion of black residents in the patient’s ZIP-code area increases. For example, the probability of undergoing a USP for a woman from the youngest age group (25–34 years) was as high as 50% if she lived in the ZIP code area with the highest concentration of black residents (top quintile), and this probability slides down to 43%, 35%, 22% and 20% if she was from areas with proportion of black residents in the fourth, third, second and first quintile, respectively. Similar patterns are observed for the two older age groups.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression of Uterine-Sparing Procedures versus Hysterectomy

| Patient Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% LCLa | 95% UCLb | Adjusted P-Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group (Ref: 25–34) | ||||

| 35–44 | 0.794 | 0.219 | 2.873 | 1.000 |

| 45–54 | 0.623 | 0.174 | 2.236 | 1.000 |

| Race Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||

| 2 | 1.111 | 0.305 | 4.054 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 2.298 | 0.670 | 7.884 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 3.175 | 0.939 | 10.729 | 0.090 |

| 5 | 4.380 | 1.304 | 14.708 | 0.003 |

| Age Group & Race Quintile Interaction (Ref: Age Group=1, Race Quintile=1)d | ||||

| 2#2 | 1.126 | 0.283 | 4.476 | 1.000 |

| 2#3 | 0.638 | 0.171 | 2.378 | 1.000 |

| 2#4 | 0.515 | 0.140 | 1.888 | 1.000 |

| 2#5 | 0.519 | 0.143 | 1.893 | 1.000 |

| 3#2 | 1.164 | 0.296 | 4.582 | 1.000 |

| 3#3 | 0.594 | 0.161 | 2.196 | 1.000 |

| 3#4 | 0.468 | 0.129 | 1.702 | 1.000 |

| 3#5 | 0.409 | 0.113 | 1.480 | 1.000 |

| Health Plan Type (Ref: Comprehensive) | ||||

| EPO | 1.158 | 0.842 | 1.592 | 1.000 |

| HMO | 1.213 | 1.054 | 1.396 | <0.001 |

| POS | 1.047 | 0.904 | 1.213 | 1.000 |

| PPO | 1.024 | 0.896 | 1.170 | 1.000 |

| CDHP/HDHP | 0.936 | 0.761 | 1.151 | 1.000 |

| Geographic Regions (Ref: Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | 0.643 | 0.584 | 0.709 | <0.001 |

| South | 0.557 | 0.509 | 0.609 | <0.001 |

| West | 0.601 | 0.543 | 0.666 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity Status (Ref: CCI=0) | ||||

| CCI=1 | 0.957 | 0.882 | 1.038 | 1.000 |

| CCI>1 | 0.770 | 0.672 | 0.882 | <0.001 |

| Income Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||

| 2 | 0.927 | 0.819 | 1.048 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 1.106 | 0.982 | 1.245 | 0.265 |

| 4 | 1.139 | 1.012 | 1.282 | 0.015 |

| 5 | 1.442 | 1.274 | 1.631 | <0.001 |

| Education Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||

| 2 | 0.887 | 0.758 | 1.038 | 0.607 |

| 3 | 1.013 | 0.870 | 1.180 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 1.064 | 0.913 | 1.239 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 1.292 | 1.104 | 1.511 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Uterine Leiomyoma-related Conditions | ||||

| Menstrual Disorders | 1.506 | 1.425 | 1.592 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic Pain | 0.772 | 0.726 | 0.820 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1.267 | 1.188 | 1.352 | <0.001 |

| Constipation or Gas | 1.054 | 0.899 | 1.235 | 1.000 |

| Urinary Problems | 0.975 | 0.839 | 1.133 | 1.000 |

| Baseline Other Gynecologic Conditions | ||||

| Endometriosis | 0.560 | 0.483 | 0.651 | <0.001 |

| Disorders of Uterus (unclassified) | 1.002 | 0.932 | 1.078 | 1.000 |

| Genital Prolapse | 0.237 | 0.181 | 0.309 | <0.001 |

| Benign Neoplasm of the Uterus or Ovary | 0.705 | 0.445 | 1.116 | 0.613 |

| Infertility | 5.657 | 4.516 | 7.085 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Non-gynecologic Conditions | ||||

| Inflamatory Disease | 1.207 | 1.116 | 1.304 | <0.001 |

| Noninflamatory Disease | 0.921 | 0.859 | 0.988 | 0.006 |

| Any Inpatient Admission | 0.779 | 0.686 | 0.885 | <0.001 |

| Any Emergency Room Admission | 0.927 | 0.868 | 0.990 | 0.007 |

| Any NSAID Use | 0.982 | 0.925 | 1.043 | 1.000 |

| Any Hormone Use | 1.139 | 1.078 | 1.204 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 0.229 | 0.067 | 0.778 | 0.004 |

Notes:

LCL=Bonferroni-corrected Lower Confidence Limit.

UCL= Bonferroni-corrected Upper Confidence Limit. Bold-faced numbers indicates statistical significance with p-value<0.05.

Adjusted p-values are based on Bonferroni correction.

Age Groups: 1:18–34; 2:35–44; 3:45–54; 2#2 means interaction of age group 2 and race quintile 2, and so on.

Figure 1.

Marginal effects of age–race interactions (interactions between age groups and race quintiles). Q1 refers to quintile 1 of the distribution of proportion of blacks; similar interpretation for Q2–Q5. The covariates used as adjustors are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that, compared to the Northeast, patients from the South, West and Midwest were 44% (OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.51–0.61), 40% (OR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.54–0.67) and 36% (OR=0.64, 95% CI: 0.58–0.71) less likely to undergo a USP. Patients from areas with higher median household income were more likely to undergo a USP, with 14% (OR=1.14, 95% CI: 1.01–1.28) and 44% (OR=1.44, 95% CI: 1.27–1.63) higher likelihoods of undergoing a USP for patients in the 4th and 5th income quintiles, respectively compared to patients in the 1st income quintile.

Menstrual disorders (OR=1.51, 95% CI: 1.43–1.59) and infertility (OR=5.66, 95% CI: 4.52–7.09) were key baseline comorbid conditions that were associated with increased likelihood of receiving a USP than hysterectomy. On the other hand, women with baseline endometriosis (OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.48–0.65) and genital prolapse (OR=0.24, 95% CI: 0.18–0.31) were less likely to have a uterine-sparing uterine leiomyoma procedure compared to hysterectomy, respectively.

Table 3 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression that models the probability of undergoing either uterine artery embolization or endometrial ablation, compared with myomectomy as the reference procedure. The relative risk of undergoing uterine artery embolization was about 7 and 26 times higher for women in the age groups 35–44 (Relative risk ratio or RRR=6.66, 95% CI: 4.72–9.40) and 45–54 (RRR=25.82, 95% CI: 18.07–36.89) relative to the age group 25–34 years.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression of Uterine-Sparing Procedures (Reference: Myomectomy)

| UAE | EA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Relative RR | 95% LCLa | 95% UCLb | Adjusted P-Valuec | Relative RR | 95% LCLa | 95% UCLb | Adjusted P-Valuec |

| Age Group (Ref: 25–34) | ||||||||

| 35–44 | 6.663 | 4.722 | 9.400 | <0.001 | 5.186 | 4.196 | 6.410 | <0.001 |

| 45–54 | 25.816 | 18.067 | 36.888 | <0.001 | 21.219 | 16.806 | 26.791 | <0.001 |

| Health Plan Type (Ref: Comprehensive) | ||||||||

| EPO | 0.907 | 0.371 | 2.217 | 1.000 | 1.095 | 0.536 | 2.237 | 1.000 |

| HMO | 1.403 | 0.912 | 2.158 | 0.659 | 1.238 | 0.859 | 1.784 | 1.000 |

| POS | 1.147 | 0.733 | 1.794 | 1.000 | 1.139 | 0.780 | 1.662 | 1.000 |

| PPO | 1.035 | 0.683 | 1.570 | 1.000 | 1.182 | 0.832 | 1.679 | 1.000 |

| CDHP/HDHP | 0.931 | 0.496 | 1.747 | 1.000 | 1.066 | 0.645 | 1.763 | 1.000 |

| Geographic Regions (Ref: Northeast) | ||||||||

| Midwest | 1.421 | 1.077 | 1.875 | 0.001 | 2.076 | 1.649 | 2.614 | <0.001 |

| South | 1.179 | 0.926 | 1.500 | 1.000 | 1.758 | 1.435 | 2.154 | <0.001 |

| West | 0.856 | 0.643 | 1.141 | 1.000 | 1.123 | 0.889 | 1.419 | 1.000 |

| Comorbidity Status (Ref: CCI=0) | ||||||||

| CCI=1 | 1.075 | 0.844 | 1.370 | 1.000 | 1.217 | 0.997 | 1.485 | 0.073 |

| CCI>1 | 0.952 | 0.616 | 1.473 | 1.000 | 1.257 | 0.876 | 1.802 | 1.000 |

| d Race Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||||||

| 2 | 0.975 | 0.228 | 4.161 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 0.342 | 2.530 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 1.175 | 0.293 | 4.718 | 1.000 | 0.664 | 0.255 | 1.729 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 1.144 | 0.287 | 4.552 | 1.000 | 0.496 | 0.192 | 1.284 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 1.273 | 0.321 | 5.055 | 1.000 | 0.268 | 0.104 | 0.692 | <0.001 |

| e Income Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||||||

| 2 | 1.019 | 0.703 | 1.479 | 1.000 | 1.316 | 0.968 | 1.788 | 0.162 |

| 3 | 1.174 | 0.829 | 1.662 | 1.000 | 1.130 | 0.839 | 1.522 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 1.070 | 0.752 | 1.521 | 1.000 | 1.293 | 0.962 | 1.738 | 0.199 |

| 5 | 1.319 | 0.918 | 1.894 | 0.656 | 1.384 | 1.019 | 1.882 | 0.017 |

| f Education Quintile (Ref: Quintile 1) | ||||||||

| 2 | 0.934 | 0.571 | 1.530 | 1.000 | 1.161 | 0.776 | 1.735 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 0.932 | 0.583 | 1.491 | 1.000 | 0.868 | 0.587 | 1.282 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 0.830 | 0.517 | 1.331 | 1.000 | 0.808 | 0.547 | 1.193 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 0.800 | 0.495 | 1.293 | 1.000 | 0.550 | 0.370 | 0.818 | <0.001 |

| Baseline uterine leiomyoma-related Conditions | ||||||||

| Menstrual Disorders | 1.541 | 1.318 | 1.803 | <0.001 | 4.987 | 4.358 | 5.706 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic Pain | 0.786 | 0.659 | 0.938 | <0.001 | 0.710 | 0.614 | 0.820 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 1.362 | 1.139 | 1.629 | <0.001 | 0.926 | 0.793 | 1.082 | 1.000 |

| Urinary Problems | 0.887 | 0.539 | 1.342 | 1.000 | 0.680 | 0.593 | 1.269 | 1.000 |

| Constipation or Gas | 0.851 | 0.586 | 1.344 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 0.476 | 0.973 | 0.017 |

| Baseline Other Gynecologic Conditions | ||||||||

| Endometriosis | 0.596 | 0.376 | 0.946 | 0.012 | 0.604 | 0.422 | 0.864 | <0.001 |

| Disorders of Uterus (unclassified) | 1.458 | 1.187 | 1.790 | <0.001 | 0.908 | 0.760 | 1.084 | 1.000 |

| Genital Prolapse | 0.598 | 0.214 | 1.673 | 1.000 | 0.935 | 0.436 | 2.003 | 1.000 |

| Benign Neoplasm of the Uterus or Ovary | 0.158 | 0.019 | 1.280 | 0.239 | 0.374 | 0.125 | 1.117 | 0.118 |

| Infertility | 0.117 | 0.063 | 0.217 | <0.001 | 0.051 | 0.030 | 0.085 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Non-gynecologic Conditions | ||||||||

| Inflammatory Disease | 0.864 | 0.698 | 1.070 | 1.000 | 0.768 | 0.643 | 0.918 | <0.001 |

| Non-inflammatory Disease | 0.787 | 0.634 | 0.976 | 0.010 | 0.987 | 0.832 | 1.172 | 1.000 |

| Any Inpatient Admission | 1.087 | 0.749 | 1.576 | 1.000 | 0.948 | 0.686 | 1.310 | 1.000 |

| Any Emergency Room Admission | 0.921 | 0.758 | 1.119 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.852 | 1.173 | 1.000 |

| Any NSAID Use | 1.250 | 1.049 | 1.488 | 0.001 | 1.266 | 1.092 | 1.467 | <0.001 |

| Any Hormone Use | 0.765 | 0.651 | 0.900 | <0.001 | 0.869 | 0.763 | 0.990 | 0.021 |

| Constant | 0.040 | 0.009 | 0.181 | <0.001 | 0.176 | 0.061 | 0.510 | <0.001 |

Notes:

LCL= Bonferroni-corrected Lower Confidence Limit.

UCL= Bonferroni-corrected Upper Confidence Limit.

Adjusted p-values are based on Bonferroni correction. Bold-faced numbers indicates statistical significance with p-value <0.05.

Quintile of %black in ZIP code, 2000 Census: 1=0% black; 2=0.1%–0.3%; 3=0.4%–1.3%; 4=1.4%–8.5% black, 5= ≥8.6%

uintile of median income in ZIP code, 2000 Census: 1=$0–$28,280; 2 = 28,281-$33,680; 3=$33,681-$39,204; 4=$39,205-$48,749; 5=≥$48,750 values

Quintile of percentage with college degree in ZIP code, 2000 Census: 1=lowest values, 5=highest values: 1 = 0%–7% with college degree, 2 = 8%–11%, 3=12%–15%, 4=16%–24% and 5= ≥25%

Patients with baseline uterine conditions including menstrual disorder, anemia and disorders of uterus were 1.5, 1.4 and 1.5 times more likely to receive uterine artery embolization than a myomectomy. Patients with endometriosis and infertility at the baseline were 0.60 and 0.12 times less likely to undergo uterine artery embolization.

Compared to the youngest patient group (25–34 years), those in the older age groups, 35–44 years (RRR=5.19, 95% CI: 4.20–6.41) and 45–54 years (RRR=21.22, 95% CI: 16.81–26.79) had higher relative risk of undergoing endometrial ablation than myomectomy. Having endometriosis (RRR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.42–0.86) or infertility (RRR=0.05, 95% CI: 0.03–0.09) at the baseline was associated with significantly less likelihood of undergoing endometrial ablation compared to myomectomy. Patients’ geographic location was also associated with the receipt of endometrial ablation, with patients from the Midwest (RRR=2.08, 95% CI: 1.65–2.61) and South (RRR=1.76, 95% CI: 1.44–2.15) regions were 2.1 and 1.8 times more likely to receive endometrial ablation than myomectomy. Patients from ZIP-code areas with the highest proportion of black residents were less likely to receive endometrial ablation compared to myomectomy (RRR=0.27, 95% CI: 0.10–0.69 for patients from the top quintile of the percent of black residents). Patients from the highest income quintile were more likely to undergo endometrial ablation over myomectomy (RRR=1.38, 95% CI: 1.02–1.88); in contrast, patients from areas with highest proportion of college graduates (top quintile) were less likely to have endometrial ablation over myomectomy (RRR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.37–0.82).

Baseline menstrual disorders were significantly associated with the receipt of endometrial ablation compared to myomectomy (RRR=4.99, 95% CI: 4.36–5.71).

Discussion

Using a large commercial claims database, our study quantified the association between numerous patient characteristics and alternatives to hysterectomy for uterine leiomyomas. Strengths of this study include the large number of procedures performed in a geographically and racially diverse population-based cohort with substantial information on comorbidities and patient characteristics.

While the association of age and race independently with uterine leiomyoma has been well-documented (12–16), our study highlights this age-race interaction in a more nuanced manner. We found that, within each age category, the odds of undergoing any USP over hysterectomy increase monotonically with higher proportion of black residents by the patient’s geographic location. This age-race interaction was highest among the youngest women (25–34 years), where the odds of having a USP ranged from 20% to 50%. This is consistent with a synergy among younger women’s desire to maintain fertility, the onset of symptomatic disease at an earlier age in black women who are also more likely to desire USPs over hysterectomy.(4, 14)

The majority of the remaining findings regarding the association between patient characteristics and the odds of a USP use over hysterectomy are consistent with prior studies: decreasing age, increasing income and education are all associated with decreased hysterectomy use. Similarly, our findings are consistent with clinical impressions; infertility is strongly associated with alternatives to hysterectomy, especially myomectomy, and concomitant endometriosis or genital prolapse are associated with increasing use of hysterectomy. (20, 21, 22) The fact that menstrual disorders were associated with higher odds of having USPs compared with hysterectomy is in line with the current understanding of the effectiveness of USPs for leiomyoma symptoms.(17–19)

The findings on the association between patient characteristics and the probability of undergoing a specific USP were more complex and nuanced. While increasing age was strongly associated with both embolization and ablation, for education and race, only the highest quintile was associated with decreased use of endometrial ablation compared to myomectomy. Endometriosis at baseline was an independent risk factor for undergoing myomectomy compared to both endometrial ablation and uterine artery embolization, while the opposite was true of menstrual disorders. Collectively, these findings appear to suggest that younger women (25–34 years) were more likely to optimize fertility.(24) There were also significant regional differences with increased use of embolization in the Midwest and endometrial ablation in the Midwest and South as compared to the Northeast. Patients from areas with highest proportion of black residents tend to undergo myomectomy more than endometrial ablation potentially because black women are more likely to develop leiomyoma-induced bulk symptoms and leiomyomas occur earlier in black women, perhaps before completing childbearing.(14, 25)

The modest association between HMO type health plans and the likelihood of undergoing a USP found in our study needs to be interpreted with caution as coverage restrictions for specific procedures might have been in place. However, it likely merits further study since this was the only insurance type significantly associated with increased utilization of USPs and understanding the facets of these plans or the people who elect these plans may give insight regarding how to decrease the hysterectomy rate for leiomyomas.

Potential limitations to generalizability of these findings include the possibility that patients could have a procedure prior to the start of the study, the requirement for continuous insurance coverage which excluded a large number of women who might be potentially different, and neither Medicaid nor uninsured women were included. Another potential limitation is the fact that ZIP-code level rather than individual-level socioeconomic characteristics were assessed. However, the use of ZIP-code level socioeconomic characteristics is widely prevalent health outcomes research and is known to detect differences in health outcomes as well (26). Finally, it is possible that some of observed differences were related to the availability of treatment options and practice pattern in different areas, rather than the socioeconomic characteristics alone. Further research is necessary to determine whether and to what extent the detected difference was from patients’ preference or treatment availability reflecting health disparities in leiomyoma care.

While clinical factors including leiomyoma symptoms, size, number and location influence the selection of a treatment procedure, this study demonstrates that many additional factors can also play an influential role including income, education, insurance type and the presence of baseline comorbid conditions. The delineation of age-race interaction on the probability of undergoing a USP versus hysterectomy is a novel contribution of this study. Our study’s methodologically rigorous quantification of the risk factors associated with the probability of undergoing different leiomyoma procedures may inform the delivery patient-centered care, thereby satisfying a key gap identified in the AHRQ report (4).

Supplementary Material

Précis.

In commercially insured women, besides clinical factors, nonclinical attributes including age, socioeconomic factors, geographic region, and health plan type are associated with uterine leiomyoma treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD060503), and NIH/NCRR CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024150 and a grant from the Focused Ultrasound Foundation.

Financial Disclosure: Shannon K. Laughlin-Tommaso has received NIH funding (5K12HD065987-O2) and research funding, paid to Mayo Clinic, from Truven Health Analytics and Insightec (Israel) for a focused ultrasound ablation clinical trial. She is on the data safety monitoring board for the ULTRA trial (Halt Medical, CA). Evan R. Myers has been a consultant to AbbVie for consulting related to uterine leiomyoma, and Merck, Inc for the HPV vaccine. He has received research funding for outcomes of HPV screening and treatment from GSK, Inc, GenProbe/Hologic, Inc. Elizabeth A. Stewart has been a clinical trial investigator for NIH grants HD063312 and HD060503. She has received research funding, paid to Mayo Clinic for patient care costs, from InSightec Inc. She has been a consultant to AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Bayer Health Care, Gynesonics and Viteava for consulting related to uterine leiomyoma, and to GlaxoSmithKline for consulting related to adenomyosis and to Welltwigs for consulting related to infertility. She has also received royalties from UpToDate and Massachusetts Medical Society.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- CCAE

Commercial Claims and Encounters

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CDHP

Consumer Directed Health Plan

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- EPO

Exclusive Provider Organization

- ER

Emergency Room

- HDHP

High Deductible Health Plan

- HMO

Health Maintenance Organization

- IP

Inpatient

- MNL

Multinomial Logistic

- POS

Point of Service

- PPO

Preferred Provider Organization

- RRR

Relative Risk Ratio

- USP

Uterine-Sparing Procedure

Footnotes

Bijan J. Borah and Xiaoxi Yao did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Myers ER, Barber MA, Couchman GM, Datta S, Gray RN, Gustilo-Ashby T, et al. Management of uterine fibroids. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan M, Hartmann KE, McKoy N, Stuart G, Rankins N, Thieda P, et al. Management of Uterine Fibroids: An Update of the Evidence. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Stewart EA. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jul 24; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gliklich R, Leavy M, Velengas P, Campion D, Mohr P, Sabharwal R, et al. (Report No.: 31).Identification of Future Research Needs in the Comparative Management of Uterine Fibroid Disease: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG. Health research data for the real world: The MarketScan databases. Thomson Medstat. 2006 ( http://patientprivacyrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Thomson-Medstat-white-paper.pdf)

- 6.Danielson E. Health research data for the real world: The MarketScan® databases. Truven Health Analytics. 2014 ( http://truvenhealth.com/Portals/0/Users/031/31/31/PH_13434%200314_MarketScan_WP_web.pdf)

- 7.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Train KE. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. Second. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausman J, McFadden D. Specification tests for the multinomial logit models. Econometrica. 1984;52:1219–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ai CR, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters. 2003;80(1):123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newson RB. Frequentist q-values for multiple-test procedures. Stata Journal. 2010;10(4):568. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, Zhang J, Goldhammer H, Jones ES, et al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Feb;198(2):168 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):967–73. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Borah BJ. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. Journal of women’s health. 2013 Oct;22(10):807–16. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, Kho RM, Wu JM. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Nov;205(5):492 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Stewart EA, Rosenberg L. Age-specific incidence rates for self-reported uterine leiomyomata in the Black Women’s Health Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Mar;105(3):563–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154161.03418.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, Galen D, Garza-Leal JG, Scott J, et al. A randomized, multicenter trial of safety and efficacy of the NovaSure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002 Nov;9(4):418–28. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DW, Gibson TB, Carls GS, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Stewart EA. Uterine fibroid treatment patterns in a population of insured women. Fertility and sterility. 2009 Feb;91(2):566–74. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stovall DW. Clinical symptomatology of uterine leiomyomas. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jun;44(2):364–71. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200106000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodwin SC, Spies JB. Uterine fibroid embolization. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 13;361(7):690–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0806942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynocologists (ACOG) Women’s health: Stats and facts. Washington, DC; 2011. http://www.acog.org/~/media/NewsRoom/MediaKit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson GF, Shaber RE, Armstrong MA, Hung YY. Changes in rates of hysterectomy and uterine conserving procedures for treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;196(6):601 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.009. discussion e5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker ER, Spalding J, DuChane J, Horowitz IR. Inpatient surgical treatment patterns for patients with uterine fibroids in the United States, 1998–2002. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Oct;97(10):1336–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falcone T, Parker WH. Surgical management of leiomyomas for fertility or uterine preservation. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Apr;121(4):856–68. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182888478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacoby VL, Fujimoto VY, Giudice LC, Kuppermann M, Washington AE. Racial and ethnic disparities in benign gynecologic conditions and associated surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;202(6):514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating Area‐Based Socioeconomic Status Indicators for Monitoring Disparities within Health Care Systems: Results from a Primary Care Network. Health services research. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.