Abstract

Early life sensory experiences have a profound effect on brain organization, connectivity and subsequent behavior. In most mammals, the earliest sensory inputs are delivered to the developing brain through tactile contact with the parents, especially the mother. Prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) are monogamous and, like humans, are biparental. Within the normal prairie vole population, both the type and amount of interactions, particularly tactile contact, that parents have with their offspring varies. The question is whether these early and pervasive differences in tactile stimulation and social experience between parent and offspring are manifest in differences in cortical organization and connectivity. To address this question we examined the cortical and callosal connections of the primary somatosensory area (S1) in high contact (HC) and low contact (LC) offspring using neuroanatomical tracing techniques. Injection sites within S1 were matched so that direct comparisons between these two groups could be made. We observed several important differences between these groups. The first was that HC offspring had a greater density of intrinsic connections within S1 compared to LC offspring. The HC offspring had a more restricted pattern of ipsilateral connections while LC offspring had dense connections with areas of parietal and frontal cortex that were more widespread. Finally, LC offspring had a broader distribution of callosal connections than HC offspring and a significantly higher percentage of callosal labeled neurons. To date, this is the first study that examines individual differences in cortical connections and suggests that they may be related to natural differences in parental rearing styles associated with tactile contact.

Keywords: development, epigenetics, primary somatosensory cortex, S1, individual differences

Introduction

Everything we know about the world is relayed through our sensory receptor arrays. Early experiences mediated through our sensory systems, to a large extent, govern how we will process future sensory information and ultimately behave in a complex and dynamic physical and social environment. In most mammals, the earliest and most pervasive sensory inputs are delivered to the developing brain through contact with the parents, especially the mother.

The significance of this relationship was confirmed decades ago by Harlow and colleagues who demonstrated in macaque monkeys that the amount of time in contact with the mother has an enormous impact on offspring outcomes, with abnormalities in this relationship resulting in a variety of behavioral anomalies ranging from depression to psychosis (Harlow and Zimmermann, 1959). But what is it about mother/infant interactions that shape offspring development and subsequent behavior? Considering that early life represents a critical period for neural development, it is likely that the tactile, thermal and olfactory experience accompanying maternal (and paternal) interactions with the infant play a pivotal role in shaping the brain. Studies in rats support this supposition by demonstrating that tactile and social stimulation, such as licking and grooming by the mother, are linked to changes in subsequent behavior of the offspring including spatial learning (Liu et al., 2000a), the expression of oxytocin receptors (Francis et al., 2000), dendritic structure and function in both the neocortex and hippocampus (Pinkernelle et al., 2009; Smit-Rigter et al., 2009; Takatsuru et al., 2009), and changes in the expression of neurotrophic factors (Liu et al., 2000b; Macri et al., 2010). Finally, differential amounts of maternal licking and grooming determines levels of glucocorticoid receptor expression in the offspring's hippocampus that remain stable in adulthood and regulate stress responsivity (for review see (Hackman et al., 2010)). These effects are not genetically mediated, but are instead regulated through epigenetic mechanisms (Champagne, 2008; Champagne and Curley, 2009).

Nonetheless, this important work represents only one piece of the puzzle. It is well established that the basic pattern of cortical organization and connectivity is produced prenatally through a series of genetic cascades (e.g. (Bishop et al., 2002; Hamasaki et al., 2004), see (O'Leary and Sahara, 2008) for review). However, it is still not known how individual differences in these basic patterns of connections arise, whether early social experiences can alter neural circuitry, and how these anatomical changes are related to subsequent differences in social behavior.

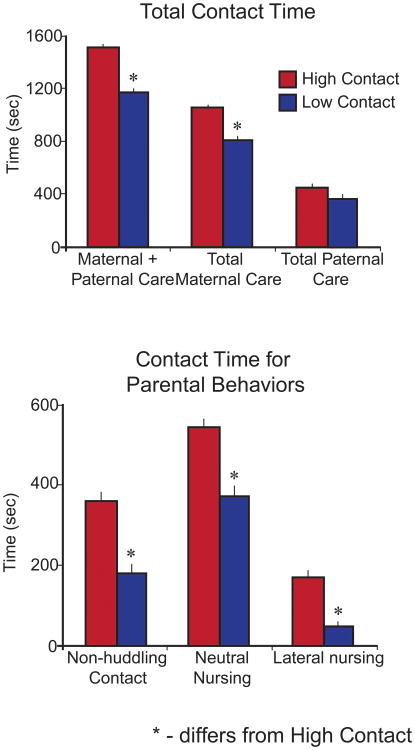

To address this question we use a unique animal model, the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster), which is one of only a small proportion of mammals that are monogamous, pair-bonded, and that rear their young bi-parentally (Getz et al., 1981; Perkeybile et al., 2013; Thomas and Birney, 1979; Williams et al., 1992). Similar to other small rodents, prairie voles have a gestational period of 21 days, experience eye opening around postnatal day (P) 10, and begin eating solid food around P15 (Perkeybile et al., 2013). Pair-bonded parents show remarkable variability in rearing styles, particularly in behaviors requiring close physical contact such as nursing, huddling, and non-huddling contact, all of which profoundly shape tactile experience (Fig. 1)(Perkeybile et al., 2013) and olfactory experience as well. Additionally, due to extensive research of their behavioral, hormonal, and anatomical organization (e.g. (Bales and Carter, 2003; Bales et al., 2013; Bales et al., 2007; Campi et al., 2010; Campi et al., 2007; Getz et al., 1981; Kenkel et al., 2014; Perkeybile et al., 2013)), prairie voles are an excellent model with which to study the neuroanatomical and neuroendocrine bases of social behavior and its consequences.

Figure 1. Behavioral assessment of high contact (HC) and low contact (LC) voles.

A) The total amount of time HC (red) and LC (blue) parents spend in contact with their pups. LC animals differ from HC animals on measures of maternal + paternal care (left) and total maternal care (center), but they did not differ on a measure of total paternal care (right). B) The amount of time HC and LC parents spend in specific pup-oriented behaviors. During non-huddling contact the fathers were quiescent and in contact with the pups. Lateral nursing involved the mother laying on her side with the pups latched to her ventrum. Neutral nursing involved standing over the pups in a relaxed position without locomotion. HC mothers (red) spent significantly more time than LC mothers (blue) engaging in each of these behaviors. Mean + s.e. * - significantly differs from HC. Adapted from Perkeybile et al., 2013.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 26 injections of neuroanatomical tracers were made in 13 adult prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) weighing 34 to 60 grams. To make precise comparisons between high contact and low contact animals, animals in each group had to be matched for sex and placement and size of the injection. For example, small injections in the forelimb representation in S1 in a low contact (LC; see Table 1 for abbreviations) female, could only be directly compared with an injection of a similar size in a similar location in S1 in a high contact (HC) female (rather than a large injection in the face representation of an HC female or male). Thus, of the 13 voles (and 26 injections), six injections (3 in HC animal and 3 in LC animals) were used for this study. None of the animals included in this study were littermates. Animals were born and housed in the Psychology Department Vivarium at the University of California, Davis (see Table 2 for details about individual subjects). These animals were descendants of a wild stock originally caught near Champaign, Illinois. The animals were pair housed in small laboratory cages (27 × 16 × 13 cm) in which food and water were available ad libitum. All animals were maintained on a 14:10 light/dark cycle with the lights on at 6 a.m. All experiments were performed under National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care of animals in research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis (protocol # 18000). All surgery was performed under isoflurane anesthesia, and all attempts were made to minimize suffering.

Table 1. List of Abbreviations.

| AC | Auditory cortex |

| Cing | Cingulate cortex |

| CT | Caudotemporal area |

| FM | Frontal myelin field |

| HC | High contact |

| LC | Low contact |

| M1 | Primary motor cortex |

| MM | Multimodal cortex |

| PC | Pyriform cortex |

| PR | Perirhinal cortex |

| PV | Parietal ventral area |

| S1 | Primary somatosensory cortex |

| S2 | Secondary somatosensory cortex |

| V1 | Primary visual cortex |

| V2 | Secondary visual cortex |

Table 2. Subjects.

| Case # | Sex | Weight (g) | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11-188 | F | 34 | Low Contact |

| 11-207 | F | 44 | High Contact |

| 12-24 | F | 37 | Low Contact |

| 12-140 | M | 51 | Low Contact |

| 12-144 | F | 37 | High Contact |

| 13-81 | M | 60 | High Contact |

Behavioral assessment

Subjects were the offspring of animals that had been previously assessed for parenting style. The behavioral assessments involved in this determination have been described previously (Perkeybile et al., Submitted; Perkeybile et al., 2013). Briefly, breeder pairs were observed interacting with their offspring during the first three postnatal days. Maternal and paternal behavior towards the pups was identified and categorized into behavioral types, including huddling, licking and grooming, retrieval, nest building, and nursing. The amount of time spent in each of these behaviors was quantified and summed to generate the total amount of time each breeding pair spent in contact with the pups (Fig. 1 vole behavior). The breeding pairs in the top and bottom quartiles of total contact time were assigned into the HC and LC groups, respectively. In all cases, parental behavior towards a second litter was also assessed to determine if parenting style was consistent across litters.

Surgery

Surgeries were performed using standard sterile surgical procedures. On the day of surgery, subjects were weighed and anesthetized using isoflurane (1-2%). Temperature was maintained and respiratory rate was monitored throughout the experiment. A longitudinal incision was made along the midline of the scalp and a small hole was drilled over the perioral/face representation within S1 and 0.2 μl of Fluoro-ruby (FR) or Fluoro-emerald (FE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was injected into the cortex using either a picospritzer (4 animals; General valve Corp., Fairfield, NJ) or a calibrated 1.0-μl Hamilton syringe (2 animals; Hamilton Co., Reno, NV). Following the injection, the hole was closed using Gelfoam (Pfizer, New York, NY) and cyanoacrylate adhesive (Gluture; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). The scalp was then sutured and secured with cyanoacrylate adhesive. The animal was administered post-surgical analgesic (buprenorphine, 0.03 mg/kg) and allowed to recover for 6-7 days to allow for transport of the tracer.

Histology

Following the completion of the experiment, animals were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (250 mg/kg, IP) and transcardially perfused with 15 mL of 0.9% saline, followed by 15 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer, and then 15 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde with 10% sucrose. Following perfusion, the brain was extracted and the cortex was removed from the subcortical structures. In all cases the neocortex was flattened between two glass slides and left to soak overnight in phosphate buffer. The flattened tissue was sectioned at 20 μm using a freezing microtome. Alternating cortical sections were stained for myelin and mounted for fluorescent microscopy.

Data Analysis

All reconstructions were done blind to the condition of the animal. In each case, camera lucida reconstructions of individual myelin sections were made with a stereomicroscope (Zeiss Stemi SV6; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY). As described previously [e.g. (Seelke et al., 2012)], whereas individual sections can contain many partial anatomical boundaries, the entire series of sections was examined and combined into a single comprehensive reconstruction to determine the full extent of cortical field boundaries (Fig. 2). Each reconstruction contained the outline of the section, blood vessels, tissue artifacts, probes, and architectonic borders. Sections were aligned using these landmarks and compiled into one composite image.

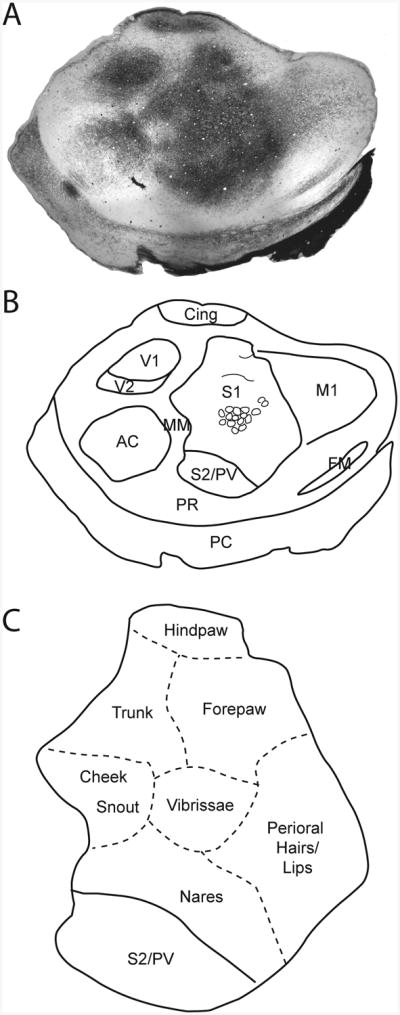

Figure 2. Reconstruction of the flattened vole cortex.

A) A tangential section of cortical tissue stained for myelin. Darkly staining fields correspond to S1 and S2/PV. Note that S1 is not homogeneous but is broken into myelin light and dark regions that separate major body part representations. Using an entire series of myelin sections, we are able to identify the borders of the sensory areas, and divisions within S1 (B). The representations of different body parts within S1 are indicated in (C). Adapted from Campi et al., 2010. Conventions as in previous figures.

Injection sites and retrogradely labeled cell bodies (Figs. 3 & 4) were plotted using an X/Y stage encoding system (MD Plot, Minnesota Datametrics, MN; htSeqTools, RRID:OMICS_01233) that was mounted to a fluorescent microscope and connected to a computer. Blood vessels and tissue artifacts from these sections were then aligned with histologically processed tissue, and all of the data were compiled into one comprehensive reconstruction in which architectonic boundaries of the neocortex were related to patterns of connections. These methods have been described previously in our laboratory [e.g. (Campi et al., 2010; Dooley et al., 2013)]. For both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, the number of labeled cells in each architectonically defined cortical field was counted (see below).

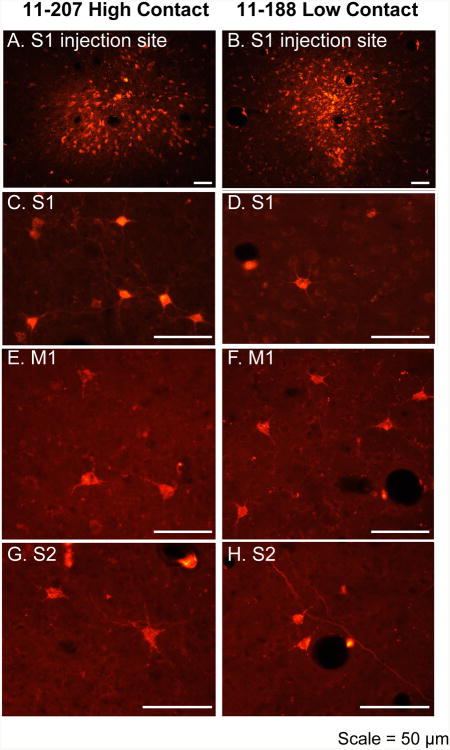

Figure 3. Examples of injections and cells retrogradely labeled with Fluoro Ruby.

Digital images showing the injection site in S1 of cases 11-207 (A) and 11-188 (B). In both cases the injection site is small and localized to S1. Labeled cells resulting from these injection sites were clearly visible. In high contact (HC; C) animals, S1 contained a higher proportion of labeled cells than in low contact (LC; D) animals. In contrast, M1 (E, F) and S2 (G, H) contained a lower proportion of labeled cells in HC than LC animals. For all cases, the number and percent of labeled cells were quantified. See Table 1 for abbreviations. Scale = 50 μm

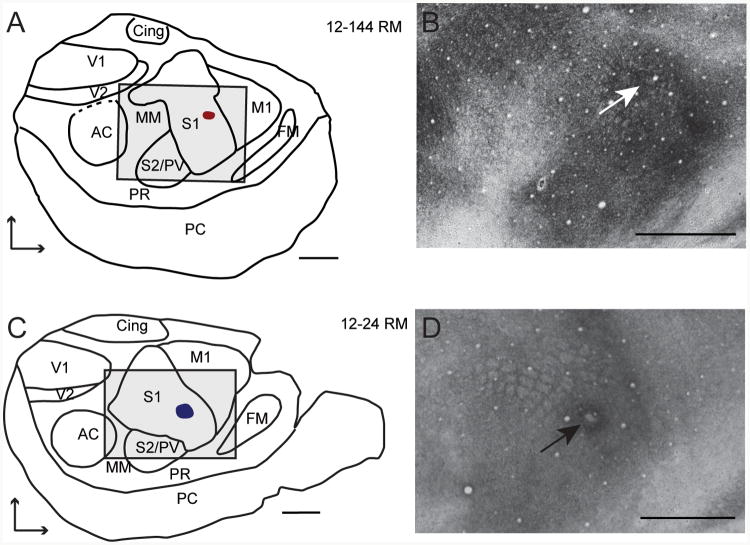

Figure 4. The location of matched injections sites.

Sites are shown in a high contact animal (A) and a low contact animal (C) relative to architectonic boundaries in tissue stained for myelin (B, D). The boxes in A and C delineate the extent of the area shown in the myelin stained tissue in B and D. The boundaries drawn in A and C were determined from the entire series of myelin stained sections. Arrows indicate the location of the injection sites. Medial is up, rostral is right. Scale = 1mm. Conventions as in previous figures.

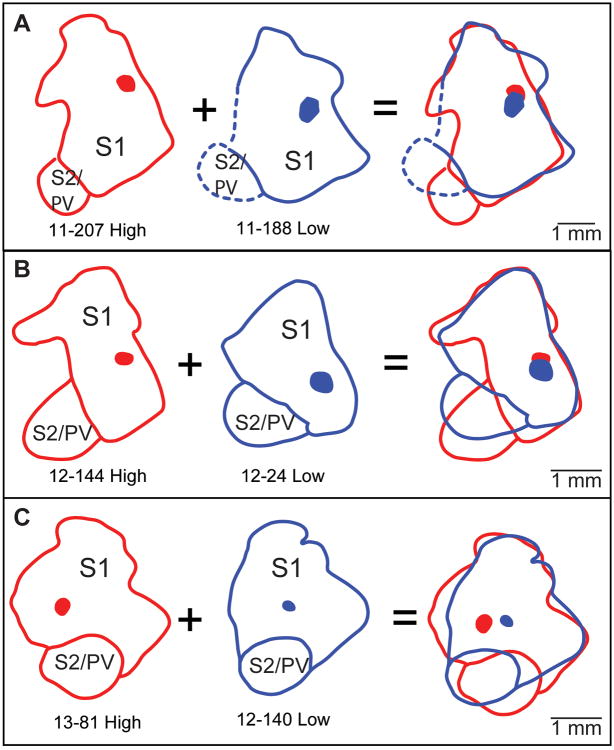

As noted above, subjects from HC and LC groups were matched by sex, injection size, and injection location. In previous studies in our laboratory, we demonstrated that that the functional boundaries of S1 are co-extensive with architectonic boundaries determined using myelin stains, and thus we could accurately estimate the major body part representation in which our injections were located (Fig. 2, e.g. face versus forelimb). Injection sizes and locations in high- and low-contact groups were matched by aligning the rostral border of S1 and comparing the relative placement of injection sites (Fig. 5). In order to be considered matching, injection sizes had to be in a comparable location and of a comparable size. Once matching high- and low-contact cases were identified, the proportion of labeled cells was calculated by counting the total number of cells in each hemisphere and dividing the number of labeled cells in each cortical field by the total number of cells in each hemisphere. Although we strictly matched both the size and location of injections, there may still be natural variation of neuronal uptake of the tracer molecule. This variation can lead to differences in the total number of labeled cells, which can bias any reporting of the number of labeled cells per unit area. For this reason we express neuronal density as a proportion of total labeled cells. This approach eliminates this potential confound and allows us to standardize the numbers across all the animals used in the study (see (Cooke et al., 2012) for details)

Figure 5. Matching injection sites.

A schematic illustrating how injection locations and sizes were matched for analysis in high and low contact (A – C). The boundaries of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) are shown as thick red (high contact) and blue (low contact) lines. The extent of the injection sites are indicated by translucent red (high contact) and blue (low contact) ovoids. This includes the injection site and the halo surrounding the site. Injection site locations and sizes were matched by aligning the rostral and lateral boundaries of S1. Injection sites were considered to be matched when they were of similar size and located in close proximity to each other (400 microns). Conventions as in previous figures. Scale = 1mm.

We next examined the difference between the proportion of labeled cells in each cortical field in HC and LC cases. The proportion of labeled cells in each cortical field was averaged across HC cases and across LC cases, and the average of the LC cases was subtracted from the average of the HC cases.

The proportion of labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere of HC and LC cases was compared as well. To do this, for each case the total number of labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere was divided by the total number of cells in both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. These values were first compared between matched HC and LC cases, then the values for all HC cases and all LC cases were averaged. The mean HC value was compared against the mean LC value using a t-test. For all statistical tests, α = 0.05. Figures were made in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA; RRID:nlx_157287), and statistics were performed using JMP statistical analysis software (JMP, SAS, Cary, NC; RRID:nif-0000-31484).

Results

A previous study characterized the differences in high contact and low contact parenting styles (Perkeybile et al., 2013). To reiterate, high contact pups received significantly more total parental contact than low contact pups (n = 304, F1,228 = 3.69, adjusted p = 0.05; Fig. 1), and this effect was driven by an increase in the amount of maternal contact (F1,228 = 9.51, adjusted p = 0.002; Fig. 1). In particular, high contact parents spent significantly more time engaging in non-huddling contact (F1,228 = 30.24, adjusted p = 0.0004; Fig. 1), neutral nursing (F1,228 = 32.06, adjusted p = 0.0006; Fig. 1), and lateral nursing (F1,228 = 29.17, adjusted p = 0.0006; Fig. 1), than low contact parents. Please refer to (Perkeybile et al., 2013) for a complete description of these data.

Although it is likely that a number of cortical and subcortical structures may vary due to differences in the amount of early sensory stimulation, we focused our study on the connections of the primary somatosensory area (S1) because much is known about its functional organization and connectivity. In addition, this field is likely to be one of structures impacted by differences in early tactile contact. For all animals, injection sites and reconstructed labeled cells were directly related to architectonically defined cortical field boundaries previously described by our laboratory (Fig. 4)(Campi et al., 2007).

Staining the neocortex for myelin clearly reveals the borders of distinct cortical fields, including the primary sensory processing areas (Fig. 2A, B). The myelination patterns found within the prairie vole neocortex have been described in detail in previous studies in our laboratory (Campi et al., 2010; Campi et al., 2007), and the results obtained here do not differ from these previous reports. Briefly, the primary visual area (V1) is located on the caudal pole of the neocortex, and it stains darkly for myelin, while the second visual area (V2) is located immediately lateral to V1 and stains less darkly for myelin. Auditory cortex (AC) is located lateral to V1 and V2, and is a round structure that stains moderately for myelin. The primary somatosensory area (S1) is immediately rostral to V1 and V2, and the second somatosensory areas (+ the parietal ventral areas, PV) are located just rostral to and adjacent to the lateral edge of S1. S1 and S2/PV both stain darkly for myelin, however the internal organization revealed by the stain is quite different for these areas. S2/PV is much smaller than S1 and stains relatively uniformly. In contrast, S1 is heterogenous in appearance, revealing the outlines of various body part representations. The most obvious of these is the barrel field, which corresponds with the functional representation of the vibrissae. As with most mammals, the hindlimb is represented medially, followed by the forelimb, vibrissae, and then the nose and snout laterally (Fig. 2C). The primary motor area, M1, is located immediately rostral to S1. These area stains moderately for myelin. The frontal myelinated region (FM), which stains darkly for myelin, is found lateral to M1 and medial to the rhinal sulcus. Finally, cingulate cortex (Cing) is located on the medial wall of the neocortex, but can be revealed during the flattening process. Cing stains very darkly for myelin.

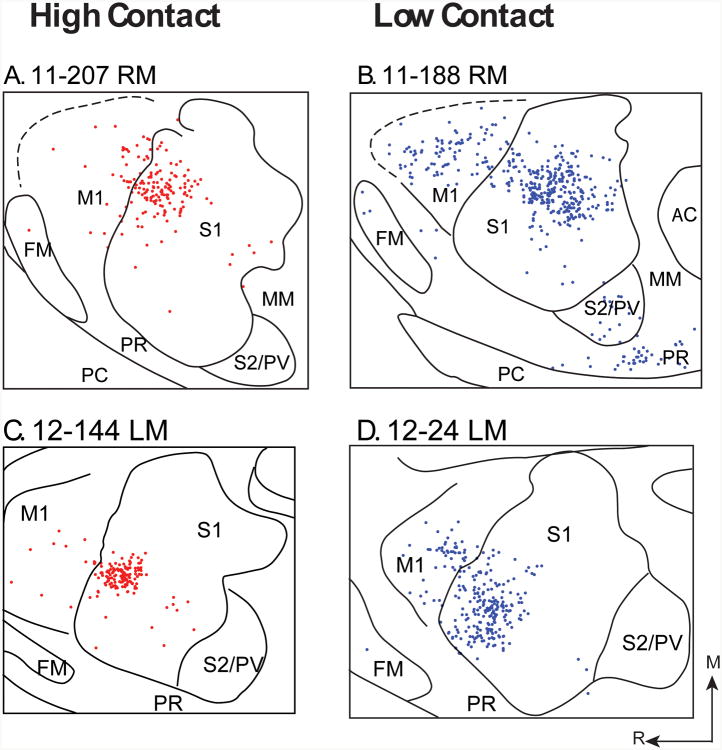

When the tracer injections were matched for location and size we saw similar overall patterns of connections in both LC and HC groups, but the density of those connections and the distribution of projection cells varied between groups. (Figs. 6-7). Patterns of connectivity that were observed for both groups included intrinsic connections with other portions of S1 as well as ipsilateral connections with areas M1, FM, MM, S2/PV, and PR (Table 1). In both HC and LC groups the majority of labeled cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere were intrinsic to S1 (Fig. 8).

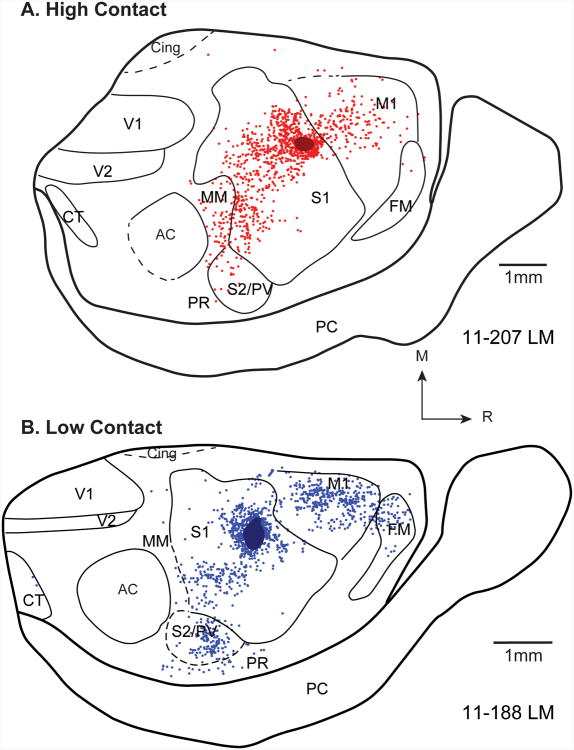

Figure 6. Patterns of ipsilateral connections.

Comparison of patterns of ipsilateral cortical connections resulting from size and location matched S1 injections in high (A) and low (B) contact voles. Red and blue dots denote individual neurons labeled by the neuroanatomical tracer in high and low contact animals, respectively. A) In the high contact animal (11-207), most ipsilateral label is intrinsic to S1. Moderate label is seen in M1, and weak label is found in S2/PV, MM, and FM. B). In the low contact animal (11-188), most ipsilateral label is intrinsic to S1. Moderate label is seen in M1 and S2/PV, and weak label is found in FM, MM, and PR. Note the difference in the distribution of labeled cells, particularly in M1, FM and S2/PV. See Figure 8 for the quantified differences in the distribution of labeled cells. Conventions as in previous figures.

Figure 7. Patterns of ipsilateral connections.

Comparison of patterns of ipsilateral cortical connections resulting from size and location matched S1 injections in high (A) and low (B) contact voles. Red and blue dots indicate individual neurons labeled by the neuroanatomical tracer in high and low contact animals, respectively. Patterns of label in S1, M1 and S2/PV are similar to those observed for high and low contact animals in the previous case (Fig. 6), but with differences in density. See Table 1 for abbreviations. Rostral is to the right and medial is up. Scale = 1mm. Conventions as in previous figures.

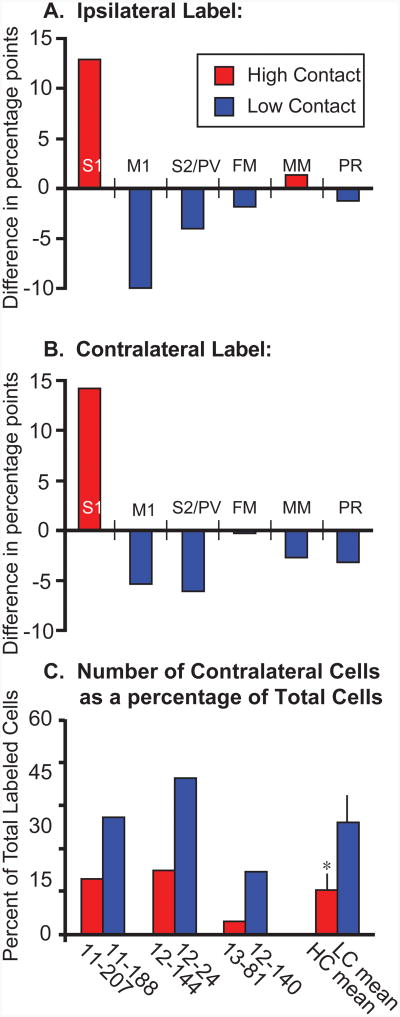

Figure 8. Distribution of labeled cells in high- and low-contact animals.

Difference in the distribution of labeled cells in high and low contact animals in both the ipsilateral (A) and contralateral (B) hemispheres. The proportion of labeled cells in each cortical field was averaged across animals within a condition (N=3). Within the ipsilateral hemisphere the mean percentages for the low contact (LC) animals were subtracted from the mean percentages for the high contact (HC) animals. The same calculations were performed for the contralateral hemisphere (“Contralateral Label”, B). Positive values indicate a higher proportion of labeled cells in a given cortical field in the HC animals, while negative values indicate a higher proportion of labeled cells in the LC animals. Thus in both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, HC animals had a higher proportion of labeled cells in S1 (12.8% more ipsilaterally, 14.2% more contralaterally) than LC animals, while LC animals had a higher proportion of labeled cells in M1 (9.8% more ipsilaterally, 5.1% more contralaterally), S2/PV (3.9% more ipsilaterally, 6.1% more contralaterally), and PR (1.2% more ipsilaterally and 3.2% more contralaterally) than HC animals. C) The proportion of labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere out of the total number of labeled cells in both hemipsheres was also determined for both HC (red) and LC (blue) voles. In matched pairs and means across each group, HC voles had proportionally fewer contralaterally labeled cells than LC voles. * - significantly different from LC.

Although S1 contained the majority of labeled cells in both groups, there were distinct differences between the distribution of labeled cells in the ipsilateral cortex of HC and LC groups. To quantify these differences, we calculated the average proportion of labeled cells in each cortical field for HC and LC groups (See Tables 3 and 4 for values). We then subtracted the mean proportion of labeled cells in each cortical area in LC animals from those in HC animals (Figs. 8A, B). This revealed that HC voles contain a much higher proportion of labeled cells in S1 (81.1%) than LC voles (68.3%). In contrast, areas M1 and S2/PV contained a higher proportion of labeled cells in LC animals than in HC animals (M1: 9.3% in HC voles, 19.1% in LC voles; S2/PV: 4.8% in HC voles, 8.6% in LC voles).

Table 3.

Ipsilateral Connections. Values indicate the percentage of labeled neurons that are found within a given cortical area.

| Case # | Condition | S1 | M1 | S2/PV | FM | MM | PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-207 | HC | 77.57 | 14.92 | 1.88 | 0.36 | 5.27 | 0 |

| 12-144 | HC | 70.82 | 13.50 | 12.01 | 0 | 2.40 | 1.26 |

| 13-81 | HC | 98.87 | 0 | 0.47 | 0 | 0.66 | 0 |

| 11-188 | LC | 59.03 | 28.04 | 9.97 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 2.34 |

| 12-24 | LC | 60.82 | 24.46 | 11.90 | 0.43 | 0 | 2.38 |

| 12-140 | LC | 88.07 | 6.88 | 4.65 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.20 |

Table 4.

Callosal connections. Values indicate the percentage of labeled neurons that are found within a given cortical area.

| Case # | Condition | S1 | M1 | S2/PV | FM | MM | PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-207 | HC | 77.71 | 21.08 | 0 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0 |

| 12-144 | HC | 92.16 | 7.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13-81 | HC | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11-188 | LC | 68.19 | 19.13 | 3.74 | 0.62 | 0.21 | 8.11 |

| 12-24 | LC | 79.55 | 18.94 | 0 | 0.38 | 0 | 1.14 |

| 12-140 | LC | 78.93 | 5.75 | 14.56 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 |

There was only one similarity in contralateral connections between HC and LC animals; specifically, both groups had dense projections from S1 of the opposite hemisphere (Fig. 9). In both conditions, the majority of labeled cells in S1 were in a location homotopic to the injection site in the opposite hemisphere. However, as was seen in the ipsilateral hemisphere, the contralateral cortex of HC voles contained a higher proportion of labeled cells in S1 than did LC voles (89.7% versus 75.4%). In LC voles, the contralateral M1 had only a few labeled cells compared to M1 in HC voles. Interestingly, there were some contralateral projections to S1 in LC voles that were not present in HC voles including projections from S2/PV and PR.

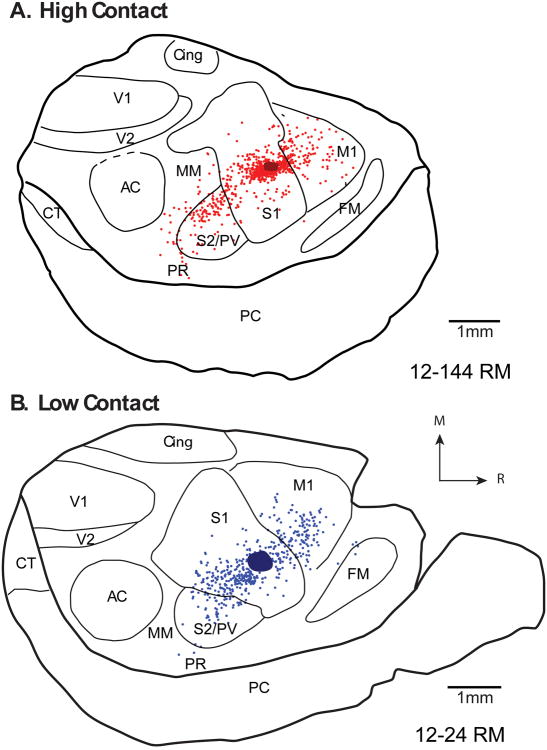

Fig 9. Patterns of contralateral connections.

Comparison of patterns of contralateral cortical connections resulting from size and location matched S1 injections in high (A and C) and low (B and D) contact voles. Red and blue dots indicate individual cells labeled by the neuroanatomical tracer in high and low contact animals, respectively. High contact (HC) cases are characterized by dense homotopic connections within S1, sparse or no label within M1, and a lack of labeled cells within S2/PV. In contrast, while low contact (LC) cases also showed dense homotopic connections within S1, they had moderate numbers of labeled cells within M1. Labeled cells were additionally found within S2/PV, MM, FM, and PR. See Table 1 for abbreviations. Rostral is to the left and medial is up. Scale = 1mm. Conventions as in previous figures.

To determine whether the distribution of labeled cells in the contralateral cortex differed between HC and LC groups, we calculated the average proportion of labeled cells in each cortical field and then subtracted the mean proportion of labeled cells in each cortical area in LC animals from those in HC animals. As in the ipsilateral cortex, the contralateral cortex of HC voles contains a much higher proportion of labeled cells in S1 than LC voles (Figs. 8 and 9). In contrast, areas M1 and S2/PV contained a higher proportion of labeled cells in LC animals than in HC animals (M1: 9.6% in HC voles, 14.6% in LC voles; S2/PV: 0% in HC voles, 6.1% in LC voles). These results are summarized in Figure 10.

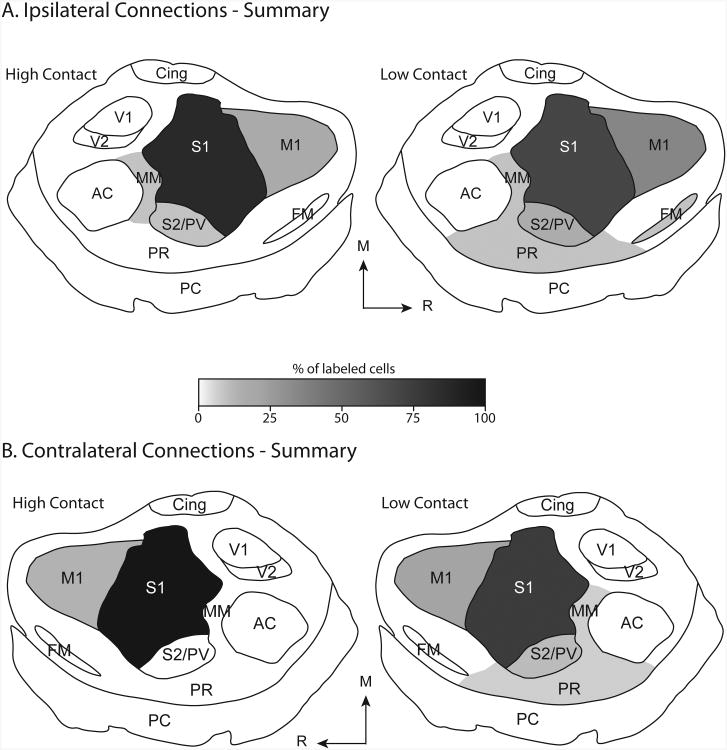

Fig 10. Summary of HC and LC connections.

Schematic representing the distribution of labeled cells in the ipsilateral and contralateral cortex of high contact (HC) and low contact (LC) voles following the injection of neuroanatomical tracers into S1. The mean proportion of labeled cells found within a given cortical area is represented by a gradient ranging from black (100% of labeled cells) to white (0% of labeled cells). Within the ipsilateral hemisphere of HC voles (A, left), S1 contained 81% of labeled cells, S2/PV contained 5% of labeled cells, M1 contained 9% of labeled cells, and MM contained 3% of labeled cells. Within the ipsilateral hemisphere of LC voles (A, right), S1 contained 68% of labeled cells, S2/PV contained 9% of labeled cells, M1 contained 19% of labeled cells, and FM, MM, and PR contained 2%, 1%, and 2% of labeled cells, respectively. Within the contralateral hemisphere of HC voles (B, left), S1 contained 90% of labeled cells and M1 contained 10% of labeled cells. Within the contralateral hemisphere of LC voles (B, right), S1 contained 75% of labeled cells, S2/PV contained 6% of labeled cells, M1 contained 15% of labeled cells, and MM and PR each contained 3% of labeled cells. Areas containing less than 1% of labeled cells were not included in this analysis. Conventions as in previous figures.

Another critical difference between the two groups involves the proportion of labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere overall (Fig. 8C). For each case, the number of labeled cells in the contralateral cortex was divided by the total number of labeled cells in both cortical hemispheres. Voles in the LC group exhibited almost three times more labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere than voles in the HC group (10.3% versus 26.1%). A paired, two-tailed t-test confirmed that the LC group contained significantly larger percentage of labeled cells in the contralateral hemisphere than the HC group (t3 = 3.70, p<0.05).

Discussion

Prairie voles are unusual among mammalian species in that they are both socially monogamous and biparental (Getz et al., 1981; Perkeybile et al., 2013; Thomas and Birney, 1979; Williams et al., 1992). These attributes make them an ideal model for examining the endocrine and neuroanatomical underpinnings of many social behaviors, including variations in parental care. We previously categorized the rearing style of pair-bonded voles by quantifying the amount of time parents spend in contact with pups; voles that scored in the top quartile are termed high contact (HC) while those that scored in the bottom quartile are termed low contact (LC) (Perkeybile et al., 2013). The natural variability in parental contact with offspring displayed by prairie voles is remarkably similar to the variability in licking and grooming behavior seen in rat dams (Champagne et al., 2003; Francis et al., 1999; Perkeybile et al., 2013). Furthermore, these variations result in differences in subsequent social behavior. For example, the offspring of HC voles spend more time sniffing a novel animal and less time autogrooming when compared to the offspring of LC voles and both LC and HC perform like their parents on an alloparental care test, thus perpetuating these two distinct phenotypes (Perkeybile et al., 2013).

Cross-fostering of offspring indicates that at least some of these differences in behavior are a result of early experience rather than heredity (Perkeybile et al., Submitted). Specifically, the behavior of cross-fostered offspring mimics that of the adoptive parents rather than their biological parents. This demonstrates that experience alone can generate differences in subsequent social and parental behaviors. The question is whether these behavioral differences are associated with measurable differences in brain organization and connectivity. A relationship between differential sensory experience, parental rearing styles, and cortical connectivity of the brain has never been established. In fact, the development of differences in connectivity within a population has itself never been examined.

Here we compared the distribution and density of ipsilateral and contralateral connections of the primary somatosensory area (S1) in prairie voles reared by HC and LC parents. We chose to target the perioral region for two reasons. First, prairie voles are born with very immature visual and auditory systems, and during early development, they depend primarily upon somatosensory and olfactory stimulation for their interactions with the environment and their parents. Second, the perioral structures are disproportionately represented within the primary somatosensory cortex (Fig. 2) (Seelke et al., 2012). Thus, the majority of sensory information (both olfactory and somatosensory) that these very young animals receive comes through the snout and perioral region. By targeting this area we were able to examine both the largest body part representation within S1 as well as the area that received the greatest amount of sensory stimulation during early development.

Our data indicate that there are quantifiable differences in the connectivity of the primary somatosensory area in LC and HC offspring. Individuals that received more tactile contact have less broadly distributed connection profiles and more intrinsic connectivity within S1. Individuals that experienced less tactile contact have more broadly distributed connections both ipsilaterally and contralaterally and less intrinsic connectivity within S1. While it is difficult to postulate what these differences in connections mean for sensory processing, these patterns of connectivity suggest that the offspring of LC parents have a greater potential for rapid (monosynaptic) multimodal sensory integration than HC offspring. These results are both novel and intriguing, but we should caution that they are also preliminary. More work, including cross-fostering studies, examination of expression of genes associated with the formation of cortical and subcortical connections, and OT receptor binding analyses will elucidate the mechanisms underlying these different patterns of connections, and uncover a causal relationship between parental rearing style and alterations in brain organization and connectivity.

Although phenotypic variety is the cornerstone of evolution by natural selection, naturally occurring individual differences in cortical organization and connectivity within a population have rarely been studied. In fact, most experiments endeavor to minimize individual differences, going so far as to only examine biological processes within one sex of a few select species (see (Krubitzer and Seelke, 2012) for review). However, when examined, individual variability within a population has been observed. For example, the functional organization of primary sensory and motor areas in the neocortex subtly, and sometimes dramatically, differs between individuals of the same species (Adams and Horton, 2003; Jain et al., 1998; Jain et al., 2001; Seelke et al., 2011; Tennant et al., 2011) (see (Krubitzer and Seelke, 2012) for review). Likewise, the architectonic boundaries of cortical areas vary between individuals (Karlen and Krubitzer, 2006), as does the distribution of vasopressin receptors (Hammock and Young, 2002). Given the importance of understanding how individual differences within a population emerge, it is somewhat surprising how little research has been done looking at how these differences are expressed at multiple levels of organization (i.e., behavior, anatomy, and genome) and the factors that contribute to these differences.

While there are only a few studies that examine individual differences of some aspect of cortical organization within a population, numerous studies have examined the role of early sensory experience in establishing aspects of cortical organization and thalamocortical connectivity. For example, in rats, exposure to continuous auditory stimuli during early development results in a loss of tone-evoked responsiveness over a large area of the primary auditory cortex (Chang and Merzenich, 2003). Similarly, removal of vibrissae in rats results in an increased functional representation and size of vibrissae “barrels” of adjacent vibrissae representations and a decrease or loss of barrels associated with the removed vibrissae (Fox, 1994; Shepherd et al., 2003). Finally, the lack of visual experience during critical periods, whether due to eyelid suturing or a blockade of activity (e.g. tetrodotoxin), results in alterations to the normal formation of ocular dominance columns in the primary visual cortex and eye-specific layers in the lateral geniculate nucleus (Chapman, 2000; Chapman et al., 1986; Tagawa et al., 2005). These relatively dramatic changes in cortical organization have all been generated through experimental manipulation of early sensory experience. However, no studies have taken advantage of the natural variations in sensory experience generated by different parenting styles.

What are the underlying mechanisms that generate these differences in cortical connectivity within a population? Of course, genes play an important role in how the neocortex differentiates into distinct areas with specific patterns of connectivity (Krubitzer and Dooley, 2013; O'Leary and Sahara, 2008; Rash and Grove, 2006). However, cross-fostering work in rats (Francis et al., 1999), and voles (Perkeybile et al., Submitted), indicates that subsequent social behavior and the type of parenting style that the offspring ultimately adapt are based on how they were reared (LC versus HC) rather than the biological relationship to the parent. Thus, we propose that variations in parent/infant tactile contact might drive some features of cortical connectivity by invoking epigenetic modifications in gene expression during development; modifications that remain stable into adulthood.

The word epigenetics is used to describe stable changes in gene expression without an underlying change in gene sequence (Goldberg et al., 2007). Given the tight temporal and spatial control of gene transcription that unfolds as development proceeds, it is not surprising that epigenetic mechanisms are involved in neuronal differentiation, migration, maturation, and circuit formation (Chittka, 2010; Cho et al., 2011; Fuentes et al., 2012; Golshani et al., 2005; Nott et al., 2013). The fact that epigenetic mechanisms also mediate environmental effects on the brain sheds light on why cortical development is particularly sensitive to environmental cues, such as the amount of tactile contact during critical periods. This sensitivity to external fluctuations allows brain development to be highly dynamic and subsequent behavior to be contextually appropriate.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Cindy Clayton, DVM, and the rest of the staff at the UC Davis Psychology Department Vivarium. Additional thanks to Julie Van Westerhuyzen for assistance during the experiments.

Support: This work was supported by grants to Leah Krubitzer (NIH R21 NS071225 and R01 EY 015387) and Karen Bales (NIH R21 060117).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no identified conflicts of interest.

References and Notes

- Adams DL, Horton JC. Capricious expression of cortical columns in the primate brain. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(2):113–114. doi: 10.1038/nn1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Carter CS. Sex differences and developmental effects of oxytocin on aggression and social behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Horm Behav. 2003;44(3):178–184. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Perkeybile AM, Conley OG, Lee MH, Guoynes CD, Downing GM, Yun CR, Solomon M, Jacob S, Mendoza SP. Chronic intranasal oxytocin causes long-term impairments in partner preference formation in male prairie voles. Biological psychiatry. 2013;74(3):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, van Westerhuyzen JA, Lewis-Reese AD, Grotte ND, Lanter JA, Carter CS. Oxytocin has dose-dependent developmental effects on pair-bonding and alloparental care in female prairie voles. Horm Behav. 2007;52(2):274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KM, Rubenstein JL, O'Leary DD. Distinct actions of Emx1, Emx2, and Pax6 in regulating the specification of areas in the developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22(17):7627–7638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07627.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi KL, Bales KL, Grunewald R, Krubitzer L. Connections of auditory and visual cortex in the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster): evidence for multisensory processing in primary sensory areas. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(1):89–108. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi KL, Karlen SJ, Bales KL, Krubitzer L. Organization of sensory neocortex in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) J Comp Neurol. 2007;502(3):414–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA. Epigenetic mechanisms and the transgenerational effects of maternal care. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2008;29(3):386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Curley JP. Epigenetic mechanisms mediating the long-term effects of maternal care on development. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2009;33(4):593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Francis DD, Mar A, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiology & behavior. 2003;79(3):359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EF, Merzenich MM. Environmental noise retards auditory cortical development. Science. 2003;300(5618):498–502. doi: 10.1126/science.1082163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B. Necessity for afferent activity to maintain eye-specific segregation in ferret lateral geniculate nucleus. Science. 2000;287(5462):2479–2482. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Jacobson MD, Reiter HO, Stryker MP. Ocular dominance shift in kitten visual cortex caused by imbalance in retinal electrical activity. Nature. 1986;324(6093):154–156. doi: 10.1038/324154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittka A. Dynamic distribution of histone H4 arginine 3 methylation marks in the developing murine cortex. PloS one. 2010;5(11):e13807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho B, Kim HJ, Kim H, Sun W. Changes in the Histone Acetylation Patterns during the Development of the Nervous System. Experimental neurobiology. 2011;20(2):81–84. doi: 10.5607/en.2011.20.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DF, Padberg J, Zahner T, Krubitzer L. The functional organization and cortical connections of motor cortex in squirrels. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(9):1959–1978. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley JC, Franca JG, Seelke AMH, Cooke DF, Krubitzer LA. A connection to the past: Monodelphis domestica provides insight into the organization and connectivity of the brains of early mammals. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2013;521:3877–3897. doi: 10.1002/cne.23383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzurumlu RS, Gaspar P. Development and critical period plasticity of the barrel cortex. The European journal of neuroscience. 2012;35(10):1540–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. The cortical component of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in the rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1994;14(12):7665–7679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07665.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 1999;286(5442):1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD, Champagne FC, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal behaviour are associated with differences in oxytocin receptor levels in the rat. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2000;12(12):1145–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes P, Canovas J, Berndt FA, Noctor SC, Kukuljan M. CoREST/LSD1 control the development of pyramidal cortical neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(6):1431–1441. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, Carter CS, Gavish L. The Mating System of the Prairie Vole, Microtus-Ochrogaster- Field and Laboratory Evidence for Pair-Bonding. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1981;8(3):189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AD, Allis CD, Bernstein E. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell. 2007;128(4):635–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshani P, Hutnick L, Schweizer F, Fan G. Conditional Dnmt1 deletion in dorsal forebrain disrupts development of somatosensory barrel cortex and thalamocortical long-term potentiation. Thalamus & related systems. 2005;3(3):227–233. doi: 10.1017/S1472928807000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(9):651–659. doi: 10.1038/nrn2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamasaki T, Leingartner A, Ringstedt T, O'Leary DD. EMX2 regulates sizes and positioning of the primary sensory and motor areas in neocortex by direct specification of cortical progenitors. Neuron. 2004;43(3):359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock EA, Levitt P. Oxytocin receptor ligand binding in embryonic tissue and postnatal brain development of the C57BL/6J mouse. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2013;7:195. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock EA, Young LJ. Variation in the vasopressin V1a receptor promoter and expression: implications for inter- and intraspecific variation in social behaviour. The European journal of neuroscience. 2002;16(3):399–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow HF, Zimmermann RR. Affectional responses in the infant monkey; orphaned baby monkeys develop a strong and persistent attachment to inanimate surrogate mothers. Science. 1959;130(3373):421–432. doi: 10.1126/science.130.3373.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Catania KC, Kaas JH. A histologically visible representation of the fingers and palm in primate area 3b and its immutability following long-term deafferentations. Cereb Cortex. 1998;8(3):227–236. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Qi HX, Catania KC, Kaas JH. Anatomic correlates of the face and oral cavity representations in the somatosensory cortical area 3b of monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429(3):455–468. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010115)429:3<455::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlen SJ, Krubitzer L. Phenotypic diversity is the cornerstone of evolution: variation in cortical field size within short-tailed opossums. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2006;499(6):990–999. doi: 10.1002/cne.21156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel WM, Suboc G, Carter CS. Autonomic, behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates of paternal behavior in male prairie voles. Physiology & behavior. 2014;128:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L, Dooley JC. Cortical plasticity within and across lifetimes: how can development inform us about phenotypic transformations? Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2013;7:620. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer LA, Seelke AMH. Cortical evolution in mammals: the bane and beauty of phenotypic variability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(Suppl 1):10647–10654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201891109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Day JC, Francis DD, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal synaptogenesis and cognitive development in rats. Nature Neuroscience. 2000a;3(8):799–806. doi: 10.1038/77702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Day JC, Francis DD, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal synaptogenesis and cognitive development in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2000b;3(8):799–806. doi: 10.1038/77702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macri S, Laviola G, Leussis MP, Andersen SL. Abnormal behavioral and neurotrophic development in the younger sibling receiving less maternal care in a communal nursing paradigm in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(3):392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan I. Oxytocin suppresses basal glutamatergic transmission but facilitates activity-dependent synaptic potentiation in the medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of neurochemistry. 2011;119(2):324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott A, Nitarska J, Veenvliet JV, Schacke S, Derijck AA, Sirko P, Muchardt C, Pasterkamp RJ, Smidt MP, Riccio A. S-nitrosylation of HDAC2 regulates the expression of the chromatin-remodeling factor Brm during radial neuron migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(8):3113–3118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218126110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DD, Sahara S. Genetic regulation of arealization of the neocortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(1):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen SF, Tuncdemir SN, Bader PL, Tirko NN, Fishell G, Tsien RW. Oxytocin enhances hippocampal spike transmission by modulating fast-spiking interneurons. Nature. 2013;500(7463):458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkeybile AM, Delaney-Busch N, Hartman S, Grimm KJ, Bales KL. Intergenerational transmission of alloparenting and oxytocin and vasopressing receptor distribution. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00191. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkeybile AM, Griffin LL, Bales KL. Natural variation in early parental care correlates with social behaviors in adolescent prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2013;7:21. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkernelle J, Abraham A, Seidel K, Braun K. Paternal deprivation induces dendritic and synaptic changes and hemispheric asymmetry of pyramidal neurons in the somatosensory cortex. Developmental neurobiology. 2009;69(10):663–673. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash BG, Grove EA. Area and layer patterning in the developing cerebral cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelke AMH, Dooley JC, Krubitzer LA. The emergence of somatotopic maps of the body in s1 in rats: the correspondence between functional and anatomical organization. PloS one. 2012;7(2):e32322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelke AMH, Padberg J, Disbrow E, Purnell S, Recanzone G, Krubitzer L. Topographic maps within Brodmann's area 5 of macaque monkeys. Cerebral Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM, Pologruto TA, Svoboda K. Circuit analysis of experience-dependent plasticity in the developing rat barrel cortex. Neuron. 2003;38(2):277–289. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit-Rigter LA, Champagne DL, van Hooft JA. Lifelong impact of variations in maternal care on dendritic structure and function of cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in rat offspring. PloS one. 2009;4(4):e5167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa Y, Kanold PO, Majdan M, Shatz CJ. Multiple periods of functional ocular dominance plasticity in mouse visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(3):380–388. doi: 10.1038/nn1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatsuru Y, Yoshitomo M, Nemoto T, Eto K, Nabekura J. Maternal separation decreases the stability of mushroom spines in adult mice somatosensory cortex. Brain Res. 2009;1294:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant KA, Adkins DL, Donlan NA, Asay AL, Thomas N, Kleim JA, Jones TA. The organization of the forelimb representation of the C57BL/6 mouse motor cortex as defined by intracortical microstimulation and cytoarchitecture. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21(4):865–876. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Birney EC. Parental Care and Mating System of the Prairie Vole, Microtus-Ochrogaster. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1979;5(2):171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Catania KC, Carter CS. Development of Partner Preferences in Female Prairie Voles (Microtus-Ochrogaster) - the Role of Social and Sexual Experience. Horm Behav. 1992;26(3):339–349. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(92)90004-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AD, Charvet CJ, Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J Neurosci. 2013;33(17):7368–7383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JJ, Li SJ, Zhang XD, Miao WY, Zhang D, Yao H, Yu X. Oxytocin mediates early experience-dependent cross-modal plasticity in the sensory cortices. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(3):391–399. doi: 10.1038/nn.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]