Abstract

Objective

In this paper we introduce the construct of “internalized gay ageism,” or the sense that one feels denigrated or depreciated because of aging in the context of a gay male identity, which we identify as an unexplored aspect of sexual minority stress specific to midlife and older gay-identified men.

Methods

Using a social stress process framework, we examine the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms, and whether one’s sense of mattering mediates or moderates this association, controlling for three decades of depressive symptom histories. The sample is 312 gay-identified men (average age = 60.7 years, range = 48 – 78, 61% HIV-negative) participating in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) since 1984/85, one of the largest and longest running studies of the natural history of HIV/AIDS in the U.S., who provided contemporary (2012/13) reports of stress experiences.

Results

We find that internalized gay ageism can reliably be measured among these men, is positively associated with depressive symptoms net of an array of other factors that may also influence symptomatology (including depressive symptom histories), and mattering partially mediates but does not moderate its effect on depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Midlife and older gay men have traversed unparalleled historical changes across their adult lives and have paved the way for younger generations of sexual minorities to live in a time of less institutionalized discrimination. Still, they are at distinct risk for feeling socially invisible and devalued in their later years.

Keywords: Gay Men, Ageism, Homophobia, Mattering, Depressive Symptoms, Minority Stress

INTRODUCTION

This study examines whether “internalized gay ageism”– feeling denigrated or depreciated because one is aging as a gay man – is associated with depressive symptoms among a sample of midlife and older gay-identified men. We further examine whether one’s sense of “mattering” affects any relationship between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptomatology. This study introduces the construct of internalized gay ageism and examines its role as a relevant minority stressor within a social stress process framework.

Ageism and Homophobia

Ageism can broadly be defined as “prejudice and discrimination against older people based on the belief that aging makes people less attractive, intelligent, sexual, and productive” (Wilkinson and Ferraro 2002). Thus, ageism, as experienced by older adults, is explicit, e.g., age discrimination in hiring practices, and implicit, e.g., biased attitudes and stigmas toward older persons (Levy 2001). Ageism is socially tolerated for the most part (Levy and Banaji 2002), which is surprising given the steadily and rapidly growing numbers of older persons in the U.S. (Hess et al., 2009). In the social stress process literature, ageism– age discrimination in particular – is considered one of the many forms of “discrimination stress” (along with stress experiences associated with gender, race-ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, etc.) that may exceed individuals’ adaptive capacities, leading to distress (Thoits 2010). In addition, ageism has the potential to become a chronic social stressor in the lives of older adults (Allen 2015). Ageism is internalized to the extent that negative social stereotypes about aging become incorporated into the older individual’s self-identification (Allen 2015; Emlet 2006; Kooden 1997), representing a form of stress that can lead to negative physical and mental health outcomes (e.g., Allen 2015; Levy et al., 2002; Sabik 2015). Most forms of explicit age discrimination (e.g., in housing, employment) are illegal at the federal level in the United States but implicit and internalized ageism are normative and remain ongoing sources of stress.

In comparison, homophobia generally is defined as societal or interpersonal stigma and prejudice directed at gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons (Herek 2004). Like ageism, it may become internalized to the extent that it influences how one sees and identifies oneself as a stigmatized member of society (Malyon 1982). Internalized homophobia may be particularly germane to midlife and older gay men because these cohorts of men were pathologized in their younger years, before homosexuality per se was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1973 (Krajeski 1996). Their social identities also were tainted by AIDS stigmas when the AIDS epidemic emerged in the 1980s and gay men were subject to a negative societal response, regardless of their HIV serostatus (Herek and Capitanio 1999). Internalized homophobia is one aspect of “sexual minority stress” (other aspects include feelings of sexual orientation stigma, experiences of discrimination, and sexual identity concealment [Meyer 2003a, 2003b]). Like internalized ageism, internalized homophobia has been shown to negatively affect health (Newcomb and Mustanski 2010). Unlike internalized ageism, homophobia appears to be declining in many parts of the U.S. (Altman et al., 2012) as part of the overall social enfranchisement of sexual minorities. Nonetheless, acceptance is far from universal and laws and policies discriminating against sexual minorities remain in effect in much of the country (Institute of Medicine [IOM] 2011).

Thus, ageism is commonplace but age discrimination is illegal. Homophobia appears to be declining, although discrimination against sexual minorities is widely institutionalized and they face enduring stigma (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010). Little is known about how the confluence of these two social phenomena – ageism and homophobia – may be jointly internalized among midlife and older gay men. A small body of work touches upon some of these issues. For example, it has been noted that some gay men may experience a sense of “accelerated aging,” or the feeling that they are old even when they are relatively young because youth and physical attractiveness are disproportionately valued in the gay male community (Grant 2010, Schope 2005). Feelings of “accelerated aging” may mostly be applicable to gay men who are single and looking for sexual partners (Hostetler 2012) or who are actively involved in gay sexual subcultures (Kertzner 2001). Regardless, many older gay men endure a particular sting associated with natural aging processes because they often feel ignored within the gay male community (IOM 2011).

In addition, there is a persisting stereotype of the “predatory older homosexual” who preys upon younger men and boys (Knauer 2009). This view is partially a carry-over from laws put into place decades ago to segregate homosexual men from children and is based upon the discredited belief that there is an inherent pedophilia in homosexuality (Jacobson 1998). Thus, midlife and older gay men came of age during a time when they may have been discouraged or legally prevented from interacting with young people based on the illusory correlation between being gay and a sexual attraction toward children. This enduring stereotype may blemish societal perceptions of mature gay men, complicating their social interactions, even within the gay community (Knauer 2009; Wahler and Gabbay 1997).

In summary, due to experiences of internalized ageism and homophobia, midlife and older gay men may be exposed to unique, previously unexamined sources of stress. Such experiences may exacerbate aging-related problems and place them at elevated risk for poor mental health. We hypothesize that the particular overlap between internalized ageism and internalized homophobia among midlife and older gay men generates “internalized gay ageism.”

Social Stress Process: Internalized Gay Ageism, Mattering, and Mental Health

Social stress process theory posits that exposure to stressors leads to the experience of stress, which then may lead to distress or mental disorder (Pearlin et al., 1981). We conceptualize internalized gay ageism as a social stressor that is uniquely harmful to gay men’s mental health. Moreover, internalized gay ageism is conceived of as a particular source of minority stress, because it uniquely affects a stigmatized or marginalized population (Meyer 2003b) – midlife and older gay men.

Prior studies show that psychosocial resources may ameliorate the negative health effects of multiple forms of social stress (Thoits 2011), including sexual minority stress (e.g., Lehavot and Simoni 2011; Szymanski and Owens 2008; Wight et al., 2012). One’s sense of “mattering” is such a resource. Mattering refers to the degree to which people feel they are an important part of the world around them (Rosenberg and McCullough 1981; Taylor and Turner 2001; Elliott et al., 2004). Mattering, or at least the perception of mattering, is profoundly important to one’s sense of self, and appears to be distinguishable from self-consciousness, self-esteem, self-monitoring, alienation, and perceived social support. A key differentiation between mattering and these other concepts is that it refers to one’s subjective feelings of being significant to other people, feelings which may guard against existential despair (Thoits 2011).People with a high sense of mattering feel that others think about them, seek their advice, or care about what happens to them. In contrast, those with a low sense of mattering feel that others do not share themselves meaningfully, do not listen, and do not find them interesting (Elliott et al., 2004). There is evidence to suggest that sense of mattering declines with age (Fazio 2010), meaning that older individuals may not realize its benefits at a time of life when it would be most useful. Yet, mattering has received relatively little empirical attention in social stress research (Thoits 2011).

Many midlife and older gay men feel they are socially invisible (Knauer 2009) and dually stigmatized for both being gay and older (de Vries 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen and Muraco 2010). Moreover, they face a gay subculture that celebrates youth, vigor, and physical beauty (Grant 2010). They are also more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to live alone (Wallace et al., 2011). We contend that these day-to-day realities – isolation, invisibility, and devaluation – make mattering especially relevant to gay men as they age. Collectively they may diminish mattering in its two most fundamental forms: (a) reducing the degree to which these men feel they are the focus of attention from others; and (b) minimizing the degree to which their interpersonal relationships reward them with the feeling that they are important to another, or that another relies on them for the satisfaction of their own wants or needs (Elliott et al., 2004). Mattering may be an important psychosocial resource that acts as a mechanism by which internalized gay ageism influences mental health.

Conceptual Framework

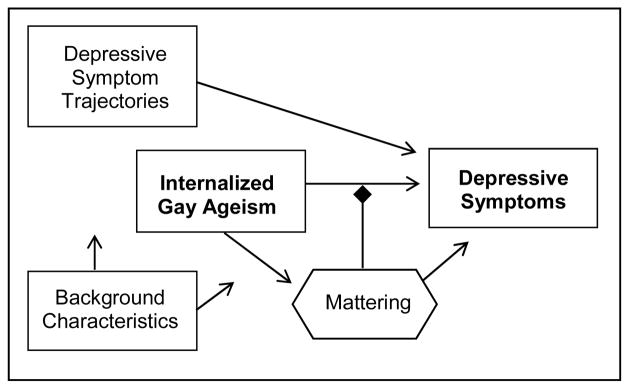

As shown in Figure 1, we hypothesize a “focal relationship” between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms in our social stress process model. A focal relationship is the foundation from which the theory driving a key association is tested and from which further tests of alternative explanations of that association can be evaluated (Aneshensel 2013). We account for multiple background characteristics that may represent alternative explanations for the focal relationship. Accounting for these “essential controls” (Wheaton and Clarke 2003) is part of an exclusionary strategy that helps rule out a spurious (i.e., false) focal relationship and enhances the hypothesized causal inference in the model (Aneshensel 2013). Essential controls include characteristics such as relationship status, education, age cohort, health status, and area of residence (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the items comprising the internalized gay ageism scale.

| How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements as they relate to your getting older as a gay man? a | Mean (SD) | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| A. As I get older, I feel good about myself as a gay man | 3.41 (0.74) | 0.49 |

| B. Aging is especially hard for me because I am a gay man | 2.08 (0.89) | 0.66 |

| C. I am not too worried about looking older | 2.63 (0.83) | 0.40 |

| D. As I get older, I feel more invisible when I am with other gay men | 2.59 (0.84) | 0.52 |

| E. I feel that older gay men are respected in the gay community | 2.30 (0.72) | 0.49 |

| F. I feel pressured to try to look younger than my age | 2.28 (0.72) | 0.41 |

|

| ||

| Total Score b | 2.27 (0.49) | |

| α | 0.66 | |

Note. SD=Standard deviation.

Response categories: 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Agree; 4 = Strongly Agree.

After reverse coding items A, C, and E.

As shown in Figure 1, we additionally control for historical patterns of depressive symptoms. Population-based studies have shown heterogeneity in depressive symptom patterns across the life course (Liang et al., 2011; Montagnier et al., 2014), with some persons remaining relatively stable and others demonstrating substantial fluctuation over time. Recent work has chronicled how such depressive symptom histories are associated with current depressive symptomatology among these midlife and older gay men (Wight et al., 2015). In essence, it has been demonstrated that patterns of stability and change in depressive symptoms over nearly 30 years (e.g., being stably high or becoming more symptomatic over time) are largely at the root of current symptoms. Indeed, taking depressogenic histories into account may weaken the effects of risk factors that otherwise would be significant predictors of symptomatology (Kessler 1997). In addition to being informative of an individual’s predisposition to depressive symptomatology, adjusting for these historical patterns helps to clarify the causal direction of stress and mental health associations by reducing concerns about reverse causation.

Figure 1 also illustrates how mattering is conceptualized as an “intervening variable” because it may at least partly transmit or generate the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms. Mattering is a viable mediator of our focal relationship if the following basic criteria are met (Baron and Kenny 1986): (a) internalized gay ageism is significantly associated with depressive symptoms; (b) internalized gay ageism is significantly associated with mattering; and (c) mattering is significantly associated with depressive symptoms when internalized gay ageism is controlled. Additionally, mattering may moderate our focal relationship if the effect of internalized gay ageism is conditional or dependent upon levels of mattering, meaning that the depressive effect of internalized gay ageism varies across different levels of mattering. In Figure 1, a diamond-headed line illustrates this moderating or “stress buffering” effect.

Thus, we examine whether internalized gay ageism is associated with depressive symptoms independent of essential controls and prior depressive symptom histories, and whether this focal relationship is mediated and/or moderated by one’s sense of mattering.

METHODS

The Sample

Data are from two sources. The first was collected over three decades (beginning in 1984/85) from participants of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) (Detels et al., 1992), one of the largest and longest running studies of the natural history of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. The original sample comprised homosexual/bisexual men who were aged 18 years and older and showed no signs of AIDS illness when the study began (additional cohorts recruited for separate studies subsequent to 1984/85 are not included in this study). HIV had not yet been named or identified in 1984 and there was no test for the virus. As a result, both HIV-negative and HIV-positive men were enrolled, making this a historical sample of gay/bisexual men in general. A variety of recruitment techniques were used to enroll men in four U.S. metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, Baltimore, Chicago, and Pittsburgh; baseline n = 4,954) and the data for this study are from the Los Angeles study site (baseline n = 1,637; 49.5% were subsequently determined to have been HIV-positive). Additional methodological details of the original MACS have been published previously (Kaslow et al., 1987). Most surviving MACS participants have been assessed (e.g., physical exam, biomarker collection, interview administration) biannually since the study’s inception, except as described below, for a maximum of 58 completed visits at the time of this analysis. Over the lengthy course of the study some participants have opted to limit their participation to providing blood samples only, many have died from HIV/AIDS-related disease (Los Angeles n = 680) or other causes (Los Angeles n = 109), and some have been lost to other forms of attrition. Beginning at visit 23 (in 1995), temporary censoring of some low-risk HIV-negative participants was implemented for budgetary reasons (Los Angeles n = 536). Nearly half of these censored participants were re-entered to the study beginning at visit 36 in 2001 (Los Angeles n = 239). If a participant relocated to an area near one of the other MACS study sites, they were asked to continue participation at that site. Thus, the sample size for the Los Angeles MACS is variable, subject to ongoing attrition, re-entry, and participant relocation.

The second data source is The Aging Stress and Health among Gay Men Study (ASH-GM), a contemporary survey of these same Los Angeles-based MACS participants conducted over a 9 month period in 2012/13, the time span comprising MACS visit 58. The total number of Los-Angeles-based MACS participants eligible for this visit, including those who were originally from one of the other three MACS sites but subsequently relocated to the Los Angeles area, was 498. Participants were invited to complete a paper and pencil survey, which required approximately 30 to 40 minutes. Most were handed the survey at their usual visit and asked to complete and return it within 30 days. The survey was mailed to Los Angeles-based participants who moved out of the area entirely or who only agreed to be contacted about MACS sub-studies, and to those who missed having it offered to them at their regular study visit. Participants were provided with incentive gift cards.

In all, 433 surveys were distributed and 342 were returned (78.98% return rate). Of these, 30 were excluded from the current study because of ineligibility (e.g., did not self-identify as gay). The final analytic sample size is 312.

This research was approved by the UCLA Office of the Human Research Protection Program (Medical Institutional Review Board 1).

Stress Measures

Internalized gay ageism

A pilot study with a sub-sample of 202 UCLA MACS participants was conducted prior to ASH-GM implementation. After a series of questions regarding sexual minority and aging-related stress, participants were asked, “Are there any comments you would like to make about how stressful these types of experiences may have been?” Based on a review of the responses, 6 items were created to form the new internalized gay ageism scale. Overall, the items assessed sentiments regarding concerns about aging as a gay man, worries about aging-related physical appearance, and feelings of invisibility within the gay community. Respondents were asked how much they agreed (1 = strongly agree) or disagreed (4 = strongly disagree) with the 6 items. Responses were averaged across items.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the items comprising the internalized gay ageism scale. Consistent with published recommendations, a factor loading of at least 0.40 was considered acceptable for this new scale (e.g., Costello et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2010). Exploratory factor analysis indicated the items formed one factor, with an average factor loading of 0.50 (range = 0.40 to 0.66). The item with the highest average score was “As I get older, I feel good about myself as a gay man” and the item with the lowest average score was “Aging is especially hard for me because I am a gay man.” The scale demonstrated adequate reliability (α = 0.66), and the average score was indicative of “disagreement” with the statements (see Table 2) although each item demonstrated wide variability. The scale was normally distributed.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of gay men aged 48–78 years in 2012/13 (n = 312).

| Sample Characteristics

|

% or M (SD)

|

|---|---|

| Background characteristics | |

| Age, years | 60.63 (6.32) |

| Born before baby boom | 19.23 |

| Born during early baby boom | 41.67 |

| Born during late baby boom | 39.10 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 90.38 |

| ≥4 years of college | 71.15 |

| Employed full time | 42.31 |

| HIV-status | |

| HIV-negative since baseline | 61.22 |

| HIV-positive at baseline | 24.68 |

| HIV-positive converted after baseline | 14.10 |

| Self-rated excellent health | 18.91 |

| Relationship status | |

| Same-sex married | 11.22 |

| Same-sex domestic partner | 10.58 |

| Same-sex committed relationship | 24.68 |

| Single | 46.79 |

| Other | 6.73 |

| Grew up in Southern California | 25.64 |

| Currently lives in Southern California | 79.17 |

| Methodological Controls | |

| UCLA Original Cohort | 89.10 |

| Temporarily Censored | 38.78 |

| Stress Domains | |

| Internalized gay ageism (1–4) | 2.27 (0.49) |

| Ageism (0–7) | 1.79 (1.75) |

| Internalized homophobia (0–4) | 0.30 (0.72) |

| Mattering (1–4) | 3.24 (0.65) |

| Mental Health | |

| Depressive symptoms (0–60) | 11.84 (11.17) |

Ageism was a count of 7 items (developed specifically for this study) assessing any occurrence in the past year of the following acts or impressions attributed to one’s age: bullied, made fun of by a stranger/strangers, ignored by others, called a derogatory name, rejected by younger people, not taken seriously, and treated like a child (α = 0.78). The score ranged from 0 to 7.

Internalized Homophobia was a count of 4 items adapted from Frost and Meyer (2009) assessing any occurrence in the past year of the following sentiments: felt it best to avoid personal or social involvement with gay people, tried to stop being attracted to men, felt that my sexual orientation was a personal shortcoming, and tried to become more sexually attracted to women (α = 0.68). The score ranged from 0 to 4.

Mattering was assessed with the 5-item Global Mattering Scale (Marcus and Rosenberg 1987), which assessed the degree to which (not at all [1] to a lot [4]) participants felt: important to other people, other people paid attention to them, others would miss them if they went away, people were interested in what they had to say, and depended on by other people (α = 0.89). Responses were averaged across items.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive Symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff 1977), and included items such as “I felt depressed,” “I felt lonely,” and “I could not ‘get going.’” Participants were asked how often (0 [rarely or none of the time] to 3 [all of the time]) in the past week they experienced the symptom (visit 58 α = 0.89). Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Aneshensel et al., 1981), all CES-D scores were log transformed in the analyses (after adding a value of 1) to improve their non-normal distribution. CES-D data were collected at every MACS visit.

Control Variables

Depressive symptom trajectories

For visits 1 through 57 (i.e., biannual data collected between 1984/85 and 2012/13) long term trajectories of depressive symptoms were created (Wight et al., 2015). CES-D data were considered complete if the participant answered at least fifteen of the 20 items; in cases where 1 to 5 items were missing, the person’s modal response for the other items at that visit was imputed (average number of imputed cases per visit = 5.61). If a participant was missing more than five CES-D items at a visit, they were coded as missing for that visit. The number of CES-D visits ranged from 4 to 57, with an average of 40.93. There was variation in the number who completed the CES-D at each visit, ranging from a maximum of 311 at visit 1 to a minimum of 150 at visits 32 and 35 (during censoring). The mean number of participants across all 57 preceding visits was 224.04. For visit 58 (n = 312) we use CES-D data collected as part of the ASH-GM survey.

To develop longitudinal depressive symptom trajectories, we used a latent class mixture model, which is a semi-parametric method that identifies distinctive clusters of relatively homogeneous individual trajectories of depressive symptoms over time (Jones et al., 2001; Nagin and Odgers 2010). Depressive symptoms since MACS baseline (visits 1 – 57) were operationalized as clusters of trajectories. Maximum likelihood estimates were obtained using the “traj” command in Stata, a customized version of the SAS “Proc Traj” command (Jones and Nagin 2013), which also provides Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) to determine the optimal number of groups with the most appropriate number of individuals per group (Jones et al., 2001). A minimum of three time points per participant is required to properly estimate a trajectory (Andruff et al., 2009). The latent class mixture model accommodates missing data but assumes it is random. Data are not missing at random in the current sample subsequent to the administrative censoring period, thus necessitating the inclusion of an indicator variable for censored vs. not in the elaborated OLS models. Baseline data (age, cohort, education, race/ethnicity, HIV-status) were included as risk factors for group membership in preliminary trajectory models but were not statistically significant and are not included in group modeling solutions. However, these variables are controlled in multivariate regression models (see below).

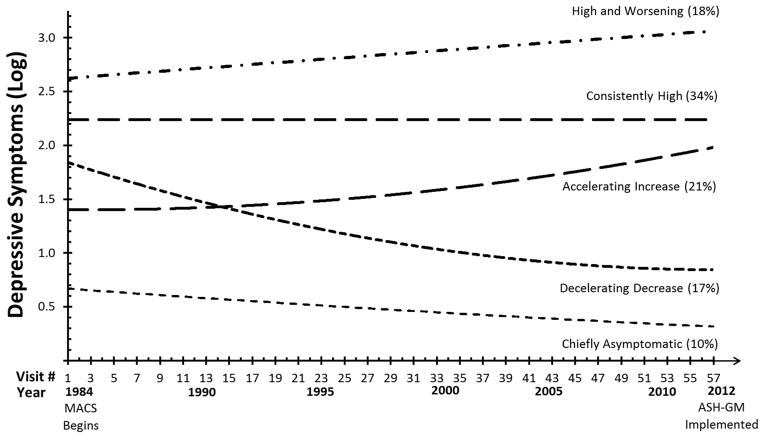

Figure 2 shows the trajectories calculated for depressive symptoms over time (Wight et al., 2015). After examining BIC criterion, posterior probabilities (PP), and sample sizes for multiple group solutions, a five-group model was identified as best describing the data (BIC = −15578.82). The CES-D trajectories were operationalized as a series of dummy variables (i.e, belongs to trajectory group 1 yes/no, belongs to trajectory group 2 yes/no, etc.). The first group, chiefly asymptomatic (9.62%, n = 30), was initially lowest on symptoms and thereafter showed a slight decline. The second group, decelerating decrease (16.99%, n = 53), started with moderately high symptoms at baseline and showed a curvilinear decline (improvement) over the three decades. The third group, accelerating increase (21.15%, n = 66), started with similar levels of symptoms as the decelerating decrease group but, contrastingly, showed a curvilinear increase in symptoms over time. The fourth group, consistently high (34.29%, n = 107), was at the same high level of depressive symptomatology across the entire span of the study. The fifth group, high and worsening (17.95%, n = 56), displayed the highest depressive symptoms at baseline and showed an increase with time.

Figure 2.

Three decade depressive symptom trajectories among gay men aged 48–78 years in 2012/13 (n = 312).

Background Characteristics

As discussed above, our analyses control for multiple background factors (i.e., “essential controls”) that may influence the observed findings in an effort to rule out spuriousness, or false findings. Relationship status was assessed with a categorical measure: (a) same-sex registered domestic partnership; (b) same-sex legal marriage; (c) same-sex partnership with no legal status; (d) something else; and (e) single (the reference group). Area of residence was controlled (currently resides in Southern California, yes/no), as was area of origin (originally from Southern California, yes/no). Participant health was assessed as self-rated excellent health (yes/no). Other control variables were clinically assessed HIV status (HIV-positive at baseline, seroconverted from HIV-negative to HIV-positive during the study, HIV-negative throughout the study [the reference group]), current age (in years, to identify simple linear effects), cohort (pre-baby-boomer born before 1946 vs. baby boomer); non-Hispanic white vs. not, four or more years of college vs. not, and employed full time vs. not.

Methodological controls

Whether the participant was part of the original UCLA Los Angeles cohort vs. originally being enrolled at another study sites (yes/no) and whether they were temporarily censored between 1995 and 2001 (yes/no) were included as methodological controls to account for study design issues that may influence findings.

Analysis: Testing Social Stress Process Models

We used sequential ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to assess theorized associations, based on the Elaboration Model (Aneshensel 2013). First, the focal relationship between current depressive symptoms and internalized gay ageism was estimated. Next, ageism and internalized homophobia were included in the model to assess whether internalized gay ageism influenced depressive symptoms independent of the two constructs from which it was derived. Background variables were then controlled. CES-D trajectories were subsequently added to the model. Finally, mattering was added to test whether it mediated the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms, net of all controls. The Sobel test was used to assess the statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05) of any mediating effect (Baron and Kenny 1986; Sobel 1982). Interactions between internalized gay ageism and mattering (both mean centered) were also added to test for stress moderation or “buffering.” The Wald test sequentially assesses model fit by testing whether the effects for added variables significantly differ from zero. Minimal missing data (≤ 3.2%) were imputed with the mode.

RESULTS

The Sample

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average participant was 60 years old (range = 48 – 78 years) with nearly 20% born before the beginning of the baby boom period (i.e., before 1946). The majority were non-Hispanic white and college graduates. Less than half were employed full time. Most were HIV-negative, although one-quarter were HIV-positive at baseline in 1984/85 and 14% seroconverted between 1984/85 and 2012/13. Nearly one in five rated their health as excellent. Slightly less than half were single, around 10% were in same-sex marriages with a similar number being in domestic partnerships, and 25% were in a non-legally recognized same-sex relationship. One-quarter grew up in Southern California and nearly 80% currently resided in Southern California. Nine in ten participants were originally members of the UCLA MACS cohort and 38.78% were temporarily censored between 1995 and 2001. Both ageism and internalized homophobia were low and mattering was relatively high. The mean CES-D score at the time of the ASH-GM survey was 11.84, indicative of moderate levels of depressive symptoms.

The Impact of Internalized Gay Ageism on Depressive Symptoms

As shown in Table 3, Model 1, the focal relationship between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms was positive and statistically significant. Internalized gay ageism accounted for 18% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Model 2 added ageism and internalized homophobia to the previous model, significantly improving the fit of the model to the data and accounting for an additional 5% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The coefficient for internalized gay ageism was reduced in magnitude but remained statistically significant. The coefficients for ageism and internalized homophobia were also statistically significant. Separate analyses (not shown) indicated that the three constructs were all significantly (p < 0.001) correlated with each other (internalized gay ageism with ageism, R = 0.41; internalized gay ageism with internalized homophobia, R = 0.28; ageism with internalized homophobia, R = 0.29). Thus, there was conceptual overlap between the three constructs although they were not collinear.

Table 3.

Ordinary least squares regressions of current depressive symptoms (log transformed) on internalized gay ageism among gay-identified men aged 48–78 years in 2012/2013 (n = 312).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressor | |||||

| Internalized gay ageism (1–4) | 0.91 (0.11)*** | 0.68 (0.12)*** | 0.63 (0.12)*** | 0.31 (0.10)** | 0.21 (0.10)* |

| Ageism (0–7) | 0.09 (0.03)** | 0.09 (0.03)** | 0.06 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.03) | |

| Internalized homophobia (0–4) | 0.22 (0.08)** | 0.18 (0.07)* | 0.16 (0.06)* | 0.11 (0.06) | |

| Stress Mediator | |||||

| Mattering (1–4) | −0.34 (0.08)*** | ||||

| Background Characteristics | |||||

| Born before baby boom | −0.14 (0.14) | −0.19 (0.12) | −0.18 (0.11) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | −0.26 (0.19) | −0.16 (0.16) | −0.13 (0.15) | ||

| ≥4 years of college | −0.25 (0.11)* | −0.17 (0.09) | −0.12 (0.09) | ||

| Employed full time | −0.39 (0.11)*** | −0.24 (0.09)** | −0.20 (0.09)* | ||

| HIV-positive at baseline a | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.04 (0.12) | 0.04 (0.12) | ||

| HIV-positive converted after baseline a | 0.09 (0.17) | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.06 (0.14) | ||

| Self-rated excellent health | −0.61 (0.17)*** | −0.40 (0.11)*** | −0.34 (0.11)** | ||

| Same-sex married b | −0.28 (0.17) | −0.03 (0.14) | 0.05 (0.14) | ||

| Same-sex domestic partner b | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.11 (0.14) | ||

| Same-sex committed relationship b | −0.07 (0.12) | −0.02 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.10) | ||

| Other relationship status b | 0.07 (0.21) | 0.24 (0.18) | 0.26 (0.17) | ||

| Grew up in Southern California | 0.17 (0.12) | 0.07 (0.10) | 0.06 (0.10) | ||

| Currently lives in Southern California | 0.02 (0.13) | −0.04 (0.11) | −0.05 (0.10) | ||

| Methodological Controls | |||||

| UCLA Original Cohort | −0.07 (0.17) | 0.08 (0.14) | 0.12 (0.14) | ||

| Temporarily censored | 0.23 (0.13) | 0 16 (0.11) | 0.13 (0.10) | ||

| Depressive Symptom Trajectories c | |||||

| Chiefly asymptomatic (Group 1) | −0.33 (0.17)* | −0.30 (0.17) | |||

| Accelerating increase (Group 3) | 0.55 (0.14)*** | 0.55 (0.13)*** | |||

| Consistently high (Group 4) | 0.83 (0.13)*** | 0.85 (0.12)*** | |||

| High and worsening (Group 5) | 1.40 (0.15)*** | 1.35 (0.15)*** | |||

| Constant | 0.04 (0.26) | 0.33 (0.26) | 1.13 (0.37)** | 0.96 (0.33)** | 2.16 (0.42)*** |

|

| |||||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| F | 67.35*** | 30.42*** | 9.30*** | 16.07*** | 17.24*** |

| Degrees of freedom | (1,310) | (3,308) | (18,293) | (22,289) | (23,288) |

| Wald test (compared to previous Model) | 10.00*** | 4.15*** | 29.96*** | 3.55* | |

| Degrees of freedom | (2,308) | (15,293) | (4,289) | (2,288) | |

Note. Regression coefficients (b) are unstandardized; SE=Standard error.

p ≤ 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Reference group = HIV-negative since baseline in 1984/1985.

Reference group = Single.

Reference group = Decelerating decrease (Group 2).

Model 3 added the background variables, slightly reducing the unstandardized regression coefficient for internalized gay ageism, which remained significant. This model accounted for 36% of the variance in depressive symptoms and significantly improved the fit of the model to the data compared to Model 2. Having four or more years of education, being employed full time, and being in excellent health were significantly associated with low depressive symptomatology.

Model 4 added the depressive symptom trajectories, reducing the unstandardized regression coefficient for internalized gay ageism by half. The R2 was .55 and Model 4 significantly improved the fit of the model to the data in comparison to Model 3. All background variables that previously were significant remained so except for having four or more years of education. Thus, controlling for prior depressive symptom histories reduced the amount of current depressive symptomatology that could be explained and diminished the effect of internalized gay ageism on current depressive symptoms but, importantly, not to the extent that this effect was no longer significant. In terms of the depressive symptom trajectories, Group 2 (decelerating decrease) was chosen as the reference category for ease of interpretation since this group’s association with depressive symptoms was significantly different from almost all of the other groups. Compared to group 2 (decelerating decrease), men in group 1 (chiefly asymptomatic) had significantly less frequent depressive symptoms. However, compared to group 2, men in groups 3 (accelerating increase), 4 (consistently high), and 5 (high and worsening) had significantly more frequent depressive symptoms. Supplemental comparisons indicated that coefficients for all trajectory groups significantly differed from one another in terms of their associations with current depressive symptomatology, with the exception of group 3 (accelerating increase) in comparison to group 4 (consistently high) (p > 0.05).

Model 5 added mattering to assess whether it mediated the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms. Mattering met the empirical criteria (Baron and Kenny 1986) for being a viable mediator. As shown, mattering was significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms and its inclusion in the model diminished the unstandardized coefficient for internalized gay ageism. Model 5 represented a significant improvement in fit compared to Model 4, and accounted for 58% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The Sobel test was statistically significant (Z = 3.85; p < 0.001) and mattering mediated 35% of the total effect of internalized gay ageism on depressive symptoms. The interaction between internalized gay ageism and mattering (both mean deviated) was added to the model to test for stress buffering but the coefficient was not statistically significant and is not presented.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored “internalized gay ageism” and how this new minority stress construct is experienced in the lives of midlife and older gay men. In particular, we examined the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms, and whether one’s sense of mattering affects that association. To help rule out spuriousness, or false findings, our analysis accounted for essential control variables in addition to participants’ histories of depressive symptoms.

We find that: (a) Internalized gay ageism can reliably be measured among these men. (b) Internalized gay ageism is differentiated from both perceived ageism and internalized homophobia. (c) Internalized gay ageism is positively associated with depressive symptoms independent of an array of other factors that may also influence symptomatology. And (d), one’s sense of mattering partially mediates but does not moderate or “buffer” the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms.

These analyses suggest that internalized gay ageism represents an underexplored form of sexual minority stress specific to midlife and older gay men. As a historical cohort, they have experienced dramatic changes over the last 40 years. These men are survivors, as AIDS has become a defining aspect of their development across the adult life course (Halkitis 2014). They are now garnering social, personal, and legal benefits from the gay rights movement that gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s (IOM 2011). Notwithstanding these gains, they are aging within a larger social culture that continues to value youth and heterosexuality and a gay subculture that places a particular premium on youth and good looks (IOM 2011).

We have shown that the convergence of internalized ageism and internalized homophobia – as measured with a new internalized gay ageism scale – is consequential to the psychological well-being of these men. Along with other forms of sexual minority stress (Meyer 2003a, 2003b), internalized gay ageism adds to the sexual identity-related challenges that midlife and older gay men may face. Further research investigating its complex social and psychological origins is much needed. Future research must also examine internalized ageism among more diverse samples of gay men and other sexual minority populations (e.g., lesbians, bisexuals, transgender individuals) to deepen understandings of its role as a sexual minority stressor.

Consistent with previous work on the ameliorative aspects of mattering (Thoits 2011), we find that this personal resource is negatively associated with depressive symptoms. We also find that mattering partially mediates the association between internalized gay ageism and depressive symptoms in that high levels of internalized gay ageism appear to diminish one’s sense of mattering, which then leads to more frequent depressive symptoms. Conversely, low internalized gay ageism seems to amplify mattering and leads to less frequent depressive symptoms. Overall, mattering diminished the depressive effect of internalized gay ageism by 30% and accounted for an additional 9% of the variance in depressive symptoms in our regression model, demonstrating its powerful influence in the social stress process. Longitudinal data would support further analyses to help determine the extent to which internalized gay ageism diminishes one’s sense of mattering over time versus the extent to which one’s sense of mattering is a more stable psychosocial resource that promotes resilience in the face of internalized gay ageism. Similarly, longitudinal data are also needed to examine the degree to which mattering may fade with age, particularly among midlife and older gay men whose social networks have been greatly reduced by AIDS, with many losing peers who would now form a foundation for a greater sense of mattering (Pearlin and LeBlanc 2001).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. The sample was self-selected and volunteered to participate in the MACS in 1984/85 and to complete the ASH-GM survey in 2012/13. Characteristics of these men are similar to those most affected by HIV/AIDS at the onset of the epidemic in the early 1980’s (gay, non-Hispanic white men living in urban areas). Still, study results should not be generalized to the population of midlife and older gay men, although the construct of internalized gay ageism is clearly relevant to this population and future research with large representative samples is needed to broaden our understanding of its impact on a range of physical and mental health outcomes. The MACS, being a survivor cohort, may underestimate the prevalence of problems faced by midlife and older gay men. There is also the possibility that unobserved confounding variables are responsible for some significant effects (e.g., internalized gay ageism may be related to unmeasured personality traits, which could account for its significant association with depressive symptoms). Sample size may account for some of the non-significant findings and a larger sample would have allowed for a systematic examination of sub-groups of men, particularly men of color, for whom stress experiences may be compounded by other forms of minority stress (Thoits 2010). Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the ASH-GM study limits us from unequivocally establishing causal directions of the observed associations, even though we control for depressive symptom histories.

Conclusion

In summary, internalized gay ageism appears to be a unique form of sexual minority stress applicable to midlife and older gay men that may affect their psychological well-being. The influence of internalized gay ageism on depressive symptoms is partially mediated by one’s sense of mattering, a personal psychosocial resource that may be amenable to public health intervention. Aging within the context of a gay male identity merits greater consideration in the development of clinical- and community-based efforts designed to support midlife and older gay men. Future research is needed that expands how internalized gay ageism is measured and how it may be associated with other stress processes and health outcomes. These men have traversed unparalleled, personally relevant historical changes across their adult lives and have paved the way for younger generations of sexual minorities to live in a time of less institutionalized discrimination. Still, they are subject to feeling socially invisible and depreciated in their later years, especially within the gay male community.

Research Highlights.

Midlife and older gay men are subject to feeling depreciated and socially invisible.

Internalized gay ageism is the confluence of ageism and homophobia among gay men.

Internalized gay ageism is positively associated with depressive symptoms.

One’s sense of “mattering” offsets the health effect of internalized gay ageism.

Internalized gay ageism is a unique, underexplored form of sexual minority stress.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R21-AG-042036, Richard G. Wight, Principal Investigator) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with co-funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-AI35040, Roger Detels, Principal Investigator). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Roger Detels, Carol S. Aneshensel, Dennis S. Miles, May Htike, Daniel Cheng, John Oishi, Kevin Barrett, Charles Doran, and Jessica Reit for assistance with the study’s implementation, and we are grateful to participants of the UCLA MACS for sharing their experiences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen JO. Ageism as a risk factor for chronic disease. The Gerontologist. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu158. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, Kong T, Reddy V, Harrad D, Reis T, Parker R. Men who have sex with men: Stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2012;380:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andruff H, Carraro N, Thompson A, Gaudreau P. Latent class growth modelling: A tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2009;5:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR, Clark VA. Family roles and sex differences in depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:379–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Theory-based data analysis for the social sciences. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detels R, Phair JP, Saah AJ, Rinaldo CR, Munoz A, Kaslow RA, Vermund S, et al. Recent scientific contributions to understanding HIV/AIDS from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of Epidemiology (Japan) 1992;2:S11–S119. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries B. LG(BT) persons in the second half of life: The intersectional influences of stigma and cohort. LGBT Health. 2014;1:18–23. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G, Kao S, Grant AM. Mattering: Empirical validation of a social-psychological concept. Self and Identity. 2004;3:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease:” Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. The Gerontologist. 2006;6:781–790. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio EM. Sense of mattering in late life. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, Wheaton B, editors. Advances in the Conceptualization of the Stress Process: Essays in Honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Muraco A. Aging and sexual orientation: A 25-year review of the literature. Research on Aging. 2010;32:372–413. doi: 10.1177/0164027509360355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM. Outing age 2010: Public policy issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender elders. Washington, D.C: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. The AIDS Generation: Stories of Survival and Resilience. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2004;1:6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. AIDS stigma and sexual prejudice. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42:1130–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Hinson JT, Hodges EA. Moderators of and mechanisms underlying stereotype threat effects on older adults’ memory performance. Experimental Aging Research. 2009;35:153–177. doi: 10.1080/03610730802716413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler AJ. Community involvement, perceived control, and attitudes toward aging among lesbians and gay men. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2012;75:141–167. doi: 10.2190/AG.75.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Building foundation for better understanding. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson RL. “Megan’s Laws” reinforcing old patterns of anti-gay police harassment. The Georgetown Law Journal. 1998;87:2431–2473. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS. A Stata plug-in for estimating group-based trajectory models. Presented at the Indiana University Social Science Research Commons Workshop in Methods.2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow RW, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;126:310–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM. The adult life course and homosexual identity in midlife gay men. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2001;12:75–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauer NJ. LGBT elder law: Toward equity in aging. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender. 2009;32:300–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kooden H. Successful aging in the middle-aged gay man. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 1997;6:21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Krajeski J. Homosexuality and the mental health professions: A contemporary history. In: Cabaj RP, Stein TS, editors. Textbook of homosexuality and mental health. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;2:159–170. doi: 10.1037/a0022839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR. Eradication of ageism requires addressing the enemy within. The Gerontologist. 2001;5:578–579. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Banaji MR. Implicit ageism. In: Nelson TD, editor. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older adults. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Xu X, Quinones AR, Bennett J, Ye W. Multiple trajectories of depressive symptoms in middle and late life: Racial/Ethnic variations. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:761–777. doi: 10.1037/a0023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus FM, Rosenberg M. Mattering: Its measurement and significance in everyday life. Paper presented at the Eastern Sociological Society Meetings; Cincinnati, OH. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Maylon AK. Psychotherapeutic implications of internalized homophobia in gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 1982;7:59–69. doi: 10.1300/j082v07n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93:262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003b;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnier D, Dartigues JF, Rouillon F, Peres K, Falissard B, Onen F. Ageing and trajectories of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling men and women. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29:720–729. doi: 10.1002/gps.4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, LeBlanc AJ. Bereavement and the loss of mattering. In: Owens TJ, Stryker S, Goodman N, editors. Extending Self-Esteem Theory and Research: Sociological and Psychological Currents. Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M, McCullough BC. Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Research in Community & Mental Health. 1981;2:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sabik NJ. Ageism and body esteem: Associations with psychological well-being among late-middle aged African American and European American women. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2015;70:191–201. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schope RD. Who’s afraid of growing old? Gay and Lesbian perceptions of aging. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2005;45:23–39. doi: 10.1300/J083v45n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Owens GP. Do coping styles moderate or mediate the relationship between internalized heterosexism and sexual minority women’s psychological distress? Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Turner RJ. A longitudinal study of the role and significance of mattering to others for depressive symptoms. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:310–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and supports to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52:145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahler J, Gabbay SG. Gay male aging. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 1997;6:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, Ford CL. The health of aging lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in California, Los Angeles, CA. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Clarke P. Space meets time: Integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:680–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, Harig F, Aneshensel CS, Detels R. Depressive symptom trajectories, aging-related stress, and sexual minority stress among midlife and older gay men: Linking past and present. Research on Aging. 2015:1–26. doi: 10.1177/0164027515590423. 0164027515590423 http://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515590423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, de Vries B, Detels R. Stress and mental health among midlife and older gay-identified men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:503–510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson JA, Ferraro KF. Thirty years of ageism research. In: Nelson TD, editor. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older adults. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. pp. 339–358. [Google Scholar]