Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to examine changes in utilization of reproductive health services by wealth status from 2000 to 2011 in Vietnam.

Methods: Data from the Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys in 2000, 2006, and 2011 were used. The subjects were 550, 1023, and 1363 women, respectively, aged between 15 and 49 years who had given birth in the previous one or two years. The wealth index, a composite measure of a household’s ownership of selected assets, materials used for housing construction, and types of water access and sanitation facilities, was used as a measure of wealth status. Main utilization indicators were utilization of antenatal care services, receipt of a tetanus vaccine, receipt of blood pressure measurement, blood examination and urine examination during antenatal care, receipt of HIV testing, skilled birth attendance at delivery, health-facility-based delivery, and cesarean section delivery. Inequalities by wealth index were measured by prevalence ratios, concentration indices, and multivariable adjusted regression coefficients.

Results: Significant increase in overall utilization was observed in all indicators (all p < 0.001). The concentration indices were 0.19 in 2000 and 0.06 in 2011 for antenatal care, 0.10 in 2000 and 0.06 in 2011 for tetanus vaccination, 0.23 in 2000 and 0.08 in 2011 for skilled birth attendance, 0.29 in 2006 and 0.12 in 2011 for blood examination, and 0.18 in 2006 and 0.09 in 2011 for health-facility-based delivery. The multivariable adjusted regression coefficients of reproductive health service utilization by wealth category were 0.06 in 2000 and 0.04 in 2011 for antenatal care, 0.07 in 2000 and 0.05 in 2011 for skilled birth attendance, and 0.07 in 2006 and 0.05 in 2011 for health-facility-based delivery.

Conclusions: More women utilized reproductive health services in 2011 than in 2000. Inequality by wealth status in utilization of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery had been reduced.

Keywords: inequality, reproductive health services, Vietnam

Introduction

Maternal mortality remains one of the significant public health challenges. Globally, the number of maternal deaths was reduced by 50% between 1990 and 2010, from more than 540,000 deaths in 1990 to 287,000 deaths in 20101). Nevertheless, this burden is unevenly distributed across the world; women in developing countries face a 15 times higher risk of dying during pregnancy or from childbirth-related complications than women in developed countries2).

In the last few decades, Vietnam has experienced a political change and rapid economic growth and has achieved a remarkable improvement in maternal health. The political and economic reforms launched in 1986 transformed Vietnam from one of the poorest countries in the world to a lower middle income country with a per capita income of 1130 USD by the end of 20103). The maternal mortality ratio fell from 233/100,000 live births in 1990 to 69/100,000 live births in 2009; however, slowdown of the rate of reduction between 2006 and 20094) indicates that the government needs to make major efforts to reduce maternal mortality by finding breakthroughs in policies and health programs5).

A growing body of evidence suggests that stark disparities in maternal mortality and utilization of reproductive health services exist both between countries and within countries6). Inequalities in antenatal care (ANC), skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery between groups according to wealth quintile7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16), education status8, 9, 12, 15), and urban versus rural areas8, 10,11,12,13, 15, 16) have been documented in different settings. On the other hand, there has been a paucity of research on the rich-poor gap in the utilization of various reproductive health services in Vietnam; earlier studies in Vietnam were based on local samples or on a single survey17,18,19). Additionally, studies on inequality in reception of specific components of antenatal care services, including blood pressure measurement, blood examination, and urine examination, and HIV testing during pregnancy, are limited.

Using three rounds of nationally representative data in Vietnam, we attempted to assess changes in the inequalities associated with utilization of seven indicators of reproductive health services, namely a) receiving antenatal care; b) receiving tetanus toxoid vaccination (TT); c) receiving ANC components recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), namely blood pressure measurement, blood examination, urine examination, and HIV testing; d) skilled birth attendance; e) delivery at a health facility; and f) cesarean section delivery by wealth status. The objective of this study was to examine the trends of inequalities in utilization of reproductive health services in Vietnam from 2000 to 2011.

Methods

Data sources and sampling

We used datasets from three rounds of the Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted in 2000 (MICS 2000), 2006 (MICS 2006), and 2011 (MICS 2011). These surveys were conducted by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, Ministry of Health of Vietnam, and Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs of Vietnam and were supported technically by the United Nations Children’s Fund.

In the MICS, households were selected by two stage sampling from urban and rural areas. The primary sampling units were census enumeration areas, and they were selected with probability proportional to size. The secondary sampling units were households, and they were selected by systematic sampling from the household list for each sampled enumeration area.

Subjects

In each survey, women aged 15 to 49 years were eligible to complete the women’s questionnaires on maternal and child health behaviors and outcomes. The numbers of respondents were 9117 of the 9346 eligible women in the MICS 2000 (response rate: 97.5%), 9473 of the 10,063 eligible women in the MICS 2006 (94.1%), and 11,663 of the 12,115 eligible women in the MICS 2011 (96.3%).

Among respondents, those who had given birth to a live infant within 2 years preceding the date of the interview in the MICS 2006 (n = 1023) and the MICS 2011 (n = 1363) were included in our study. In the MICS 2000, data were collected from women who had a live infant within 1 year preceding the date of interview (n = 550). Detailed descriptions of the study design and the methods used for data collection are described in household survey reports20,21,22).

Measurement

To assess reproductive health services utilization, we analyzed six binary dependent variables: 1) at least one ANC visit; 2) receipt of any TT; 3) receipt of ANC components as recommended by the WHO, i.e., blood pressure measurement, blood examination, urine examination, and HIV testing during the most recent pregnancy; 4) skilled birth attendance; 5) health-facility-based delivery; and 6) cesarean section delivery for the most recent live-birth delivery. Skilled birth attendance was defined as attendance by a doctor, nurse, or midwife at delivery. Delivery at a health facility was defined as delivery at a government or private health facility. Because of unavailability of data regarding blood pressure measurement, blood examination, and urine examination in MICS 2000, we analyzed MICS 2006 and MICS 2011 for these variables. Because of unavailability of data regarding cesarean section delivery in MICS 2000 and MICS 2006, we analyzed MICS 2011 for this variable.

The household wealth index was developed by a principal component analysis using data on a household’s ownership of selected assets, such as televisions and bicycles, materials used for housing construction, and types of water access and sanitation facilities20,21,22). Each household was then weighted by the number of household members, and the household population was divided into five groups of equal size, from the first quintile (poorest) to the fifth quintile (richest), based on the wealth index scores of the households in which the household members were living20,21,22).

We included theoretically pertinent socioeconomic and demographic factors as independent variables. We classified current maternal age into three groups: a younger group (15–24 years), a middle-age group (25–34 years), and an older age group (35–49 years). Maternal education was classified based on the formal education system in Vietnam: no education (0 years), primary education (1–5 years), secondary education (6–9 years), and higher education (10 years or more). Then, the binary variable for education, incomplete primary education or lower and primary education or higher, was used for analyses. Place of residence was categorized as rural or urban. Parity was categorized as one, two, and three or more.

Statistical analysis

The overall prevalence was calculated by year of survey, and the difference by year was examined by a chi-squared test for trend. The increases in prevalence between 2000 and 2011 and between 2006 and 2011 were calculated.

As measures of inequalities, the prevalence difference, prevalence ratio, and concentration index were calculated for each dependent variable.

The prevalence differences were calculated by subtracting the prevalence for the poorest wealth quintile from the prevalence for the richest quintile. The prevalence ratios were calculated by dividing the prevalence for the richest wealth quintile by the prevalence for the poorest quintile.

Concentration curves were drawn by plotting the cumulative percentages of the health variable (y-axis) against the cumulative percentages of the population, ranked according to living standards, beginning with the poorest and ending with the richest (x-axis). Drawing the concentration curves in this way showed the cumulative use of health interventions by each wealth quintile. Concentration curves that fall below the diagonal line (line of equality) signify the presence of inequality favoring the rich, whereas concentration curves that fall above the line of equality signify that the inequality favors the poor. Concentration curves for the same variable in different time periods can be plotted on the same graph. If the concentration curve for one time period lies everywhere closer to the line of equality than the concentration curve for another time period, the first curve is said to dominate the second, and the ranking by degree of inequality is unambiguous. Non-dominance arises when concentration curves cross, and when they cross, a summary index of inequality is required in order to rank time periods by degree of inequality.

The standard concentration index was defined as twice the area between the concentration curve and the diagonal line, and it provides a measure of the extent of inequalities in health service utilization that are systematically associated with socioeconomic status. Concentration index values range between –1 and +1, with 0 indicating perfect equality, –1 indicating that all the health service utilization is concentrated in the hands of the most disadvantaged persons, and +1 indicating that all the health service utilization is concentrated in the hands of the least disadvantaged persons23). We also calculated the corrected concentration index for the binary health indicator proposed by Erreygers24).

We created a fully adjusted model to analyze the risk factors of each health service utilization outcome by entering all the covariates simultaneously into a linear regression model. Multicollinearity in the linear regression analyses was checked by examining the variance of inflation factors. No variance inflation factor was higher than 2.0 in the present analyses, and no variables were removed from the model. We estimated adjusted regression coefficients to assess the strength of associations and used 95% confidence intervals for significance testing. The Stata MP V.11 Statistical Software (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA) was used to perform all of the analyses.

Ethical considerations

This study was a data analysis of publicly available data, which did not contain any individual identifiers. After being read a document emphasizing the voluntary nature of this project, outlining the potential risks, and explaining that the information gathered would be used to assess health care needs and to plan health services, all of the eligible subjects were asked to give their informed consent to participation in the survey. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the survey at any time.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic profile of the women. The proportion of women who had completed primary education increased from 64.4% in 2000 to 90.4% in 2011, and the proportion of women with three or more children decreased from 29.1% in 2000 to 16.4% in 2011 (all P < 0.001 by chi-square test for trend in proportions).

Table 1. Frequency distribution of characteristics of women aged 15–49 years who had given birth in the previous 2 years, Vietnam, 2000–2011.

| Characteristics | 2000 (N = 550) | 2006 (N = 1023) | 2011 (N = 1363) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Age category | ||||||

| 15–24 years | 221 | 40.9 | 362 | 34.9 | 453 | 33.9 |

| 25–34 years | 243 | 44.7 | 522 | 51.5 | 755 | 55.1 |

| 35–49 years | 86 | 14.4 | 139 | 13.6 | 155 | 11.0 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 92 | 18.5 | 226 | 23.1 | 542 | 29.1 |

| Rural | 458 | 81.5 | 797 | 76.7 | 821 | 70.9 |

| Relative wealth category | ||||||

| Poorest | 187 | 27.8 | 284 | 19.0 | 327 | 21.7 |

| Poorer | 103 | 18.6 | 178 | 16.1 | 223 | 19.0 |

| Middle | 99 | 18.7 | 194 | 21.5 | 240 | 18.2 |

| Richer | 91 | 18.8 | 195 | 23.1 | 268 | 19.5 |

| Richest | 70 | 16.0 | 172 | 20.4 | 305 | 21.6 |

| Education | ||||||

| Incomplete primary | 218 | 35.4 | 304 | 25.8 | 135 | 9.6 |

| Primary or higher | 332 | 64.4 | 719 | 74.2 | 1228 | 90.4 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1 | 182 | 35.8 | 404 | 42.2 | 599 | 45.3 |

| 2 | 178 | 35.1 | 357 | 36.3 | 525 | 38.3 |

| ≥ 3 | 190 | 29.1 | 262 | 21.5 | 239 | 16.4 |

Numbers are unweighted; percentages are adjusted by weighting.

Table 2 shows the reproductive health services utilization by year and by place of residence. Percentage of utilization of individual components of reproductive health services increased between 2000 and 2011: the greatest increase between 2000 and 2011 was in skilled birth attendance (increased by 23.3 percentage points), and this was follwed by the increase in HIV testing (increased by 22.3 percentage points), ANC utilization (increased by 17.1 percentage points), and receiving TT (increased by 13.8 percentage points) (all P < 0.001 by chi-square test for trend in proportions). There were increases in utilization of all three ANC components between 2006 and 2011: blood pressure measurement (increased by 9.8 percentage points), blood examination (increased by 16.6 percentage points), and urine examination (increased by 21.5 percentage points) (all P < 0.001 by chi-square test). Delivery at a government or private health facility increased by 7.8 percentage points between 2006 and 2011.

Table 2. Utilization of reproductive health services, Vietnam, 2000–2011.

| Overall | Place of residence | Difference byplace of residence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | |||

| Utilization of antenatal care services | ||||

| 2000 | 77.6 | 96.8 | 73.2 | 23.6 (18.1 to 29.1) |

| 2006 | 90.9 | 98.2 | 88.7 | 9.6 (6.7 to 12.4) |

| 2011 | 94.6 | 98.0 | 93.3 | 4.7 (2.7 to 6.8) |

| Increase a | 17.1 (13.3 to 20.9) | 1.2 (–2.6 to 4.9) | 20.1 (15.5 to 24.6) | |

| Increase b | 3.8 (1.6 to 5.9) | –0.2 (–2.4 to 2.0) | 4.6 (1.8 to 7.4) | |

| Receipt of a tetanus vaccine | ||||

| 2000 | 75.6 | 90.5 | 72.2 | 18.3 (11.0 to 25.6) |

| 2006 | 87.5 | 95.1 | 85.2 | 9.9 (6.1 to 13.7) |

| 2011 | 89.4 | 93.5 | 87.7 | 5.9 (2.7 to 9.0) |

| Increase a | 13.7 (9.7 to 17.8) | 3.0 (–3.4 to 9.4) | 15.4 (10.6 to 20.2) | |

| Increase b | 1.9 (–0.8 to 4.5) | –1.6 (–5.3 to 2.1) | 2.5 (–0.8 to 5.8) | |

| Receipt of a blood pressure measurement | ||||

| 2006 | 74.4 | 88.7 | 69.6 | 19.1 (13.7 to 24.6) |

| 2011 | 82.0 | 91.9 | 77.7 | 14.2 (10.4 to 18.0) |

| Increase b | 7.5 (4.0 to 11.1) | 3.1 (–1.8 to 8.1) | 8.1 (3.6 to 12.5) | |

| Receipt of a urine examination | ||||

| 2006 | 46.8 | 71.6 | 38.4 | 33.2 (26.2 to 40.2) |

| 2011 | 67.8 | 82.7 | 61.4 | 21.4 (16.5 to 26.2) |

| Increase b | 21 (16.9 to 25.2) | 11.1 (4.1 to 18.1) | 23.0 (18.1 to 27.9) | |

| Receipt of a blood examination | ||||

| 2006 | 34.5 | 63.5 | 24.7 | 38.8 (31.6 to 45.9) |

| 2011 | 50.7 | 71.1 | 41.9 | 29.1 (23.6 to 34.6) |

| Increase b | 16.2 (12.1 to 20.4) | 7.6 (–0.2 to 15.3) | 17.2 (12.6 to 21.8) | |

| Receipt of an HIV test | ||||

| 2000 | 10.3 | 38.9 | 3.8 | 35.1 (25.1 to 45.1) |

| 2006 | 16.4 | 43.4 | 8.2 | 35.1 (28.4 to 41.9) |

| 2011 | 32.6 | 52.6 | 24.4 | 28.2 (22.7 to 33.8) |

| Increase a | 22.3 (18.7 to 25.9) | 13.7 (2.7 to 24.6) | 20.6 (17.3 to 23.8) | |

| Increase b | 16.2 (12.8 to 19.6) | 9.2 (1.1 to 17.3) | 16.2 (12.8 to 19.5) | |

| Delivery attended by skilled workers | ||||

| 2000 | 69.5 | 96.9 | 63.2 | 33.6 (27.8 to 39.4) |

| 2006 | 87.7 | 98.2 | 84.5 | 13.7 (10.6 to 16.9) |

| 2011 | 92.8 | 98.8 | 90.4 | 8.3 (6.2 to 10.5) |

| Increase a | 23.3 (19.1 to 27.5) | 1.9 (–1.8 to 5.5) | 27.2 (22.2 to 32.1) | |

| Increase b | 5.2 (2.7 to 7.6) | 0.5 (–1.5 to 2.6) | 5.9 (2.7 to 9.1) | |

| Delivery in a health facility | ||||

| 2006 | 84.8 | 98.7 | 80.6 | 18.1 (14.9 to 21.3) |

| 2011 | 92.6 | 99.0 | 90.0 | 9.0 (6.9 to 11.1) |

| Increase b | 7.8 (5.2 to 10.5) | 0.3 (–1.4 to 2.1) | 9.4 (6.0 to 12.8) | |

| Delivery by cesarean section | ||||

| 2011 | 20.0 | 30.8 | 15.5 | 15.3 (15.3 to 15.4) |

a Increase in prevalence from 2000 to 2011. b Increase in prevalence from 2006 to 2011. The numbers of subjects included in each analysis differed because of missing data. The numbers of subjects with missing data were as follows: HIV test, 116 in MICS 2000; HIV test, 147 in MICS 2006; blood pressure measurement, blood examination, and urine examination, 147 in MICS 2006; HIV test, 158 in MICS 2011; and blood pressure measurement, blood examination, and urine examination, 97 in MICS 2011.

The increase in the utilization between 2000 and 2011 or between 2006 and 2011 tended to be higher in rural areas than in urban areas for all the reproductive health service variables. The difference between rural and urban areas tended to be narrower between 2000 and 2011 or between 2006 and 2011 for all the reproductive health service variables, except receipt of an HIV test, which showed a stable urban and rural difference between 2000 and 2006.

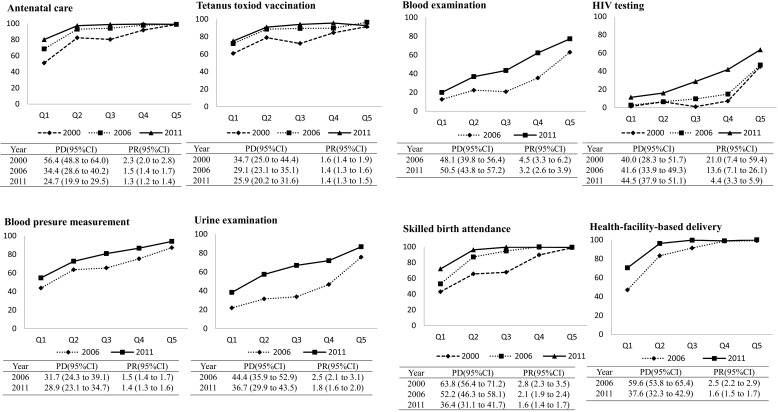

Figure 1 shows the trend in the reproductive health services utilization by wealth status. The differences between the poorest and the richest groups tended to decrease over time in regard to visiting an ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery, based on both the prevalence difference and the prevalence ratios.

Figure 1.

Trends in utilization of reproductive health services by wealth index category (Wealth index quintiles: Q1, poorest; Q2, poorer; Q3, middle; Q4, richer; Q5, richest), Vietnam, 2000–2011. PD, prevalence difference comparing Q5 with Q1; PR, prevalence ratio comparing Q5 with Q1. The vertical axis represents the percentage of women who utilized the service.

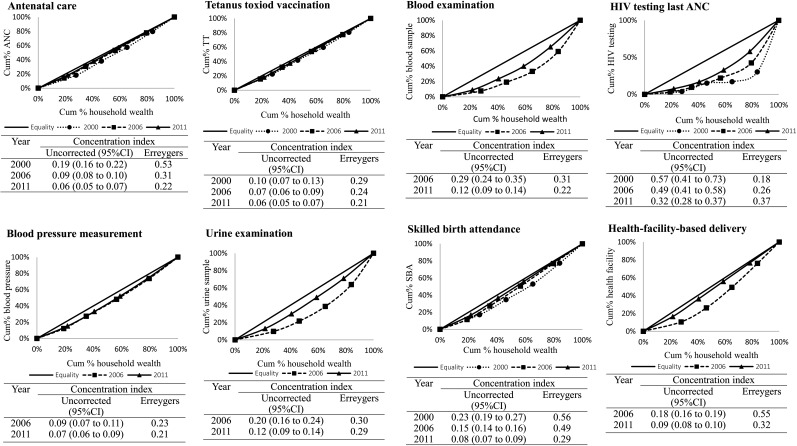

Figure 2 presents concentration curves of individual variables. For all reproductive health services, the curves were below the line of equality in all three years. The concentration indices for ANC, urine examination, blood examination, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery tended to be lower between 2000 and 2011.

Figure 2.

Inequalities in utilization of reproductive health services by wealth status, Vietnam, 2000-2011. Cum%, cumulative percentage. Both uncorrected and Erreygers’ corrected concentration indices are shown. Positive values for the concentration index indicate increasing inequality favoring the rich, meaning that richer groups are utilizing services disproportionately more than poorer groups.

Multivariate analysis

Table 3 shows the partial regression coefficients for reproductive health services utilization according to sociodemographic characteristics after adjustment for the change in education, place of residence, age, and parity. Mothers in the richer households were significantly more likely to utilize individual services, except for receipt of a tetanus vaccine in 2000 and receipt of blood pressure measurement in 2006 (both P > 0.05). An increase in the magnitude of the point estimates of the association between wealth index and indicators related to reproductive health service utilization from 2000 or 2006 to 2011 was observed for receipt of blood pressure measurement, blood examination, urine examination, and HIV testing. The regression coefficients tended to decrease for utilization of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery.

Table 3. Multivariable adjusted partial regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals of utilization of reproductive health services by sociodemographic characteristics, Vietnam, 2000–2011.

| 2000 | 2006 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Ultilization of antenatal care services | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09) | 0.04 (0.03, 0.05) | 0.04 (0.03,0.04) |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.16 (–0.23, –0.08) | –0.11 (–0.15, –0.08) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.08) |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.04 (–0.07, 0.14) | –0.11 (–0.51, 0.03) | –0.04 (–0.06, –0.01) |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.11 (–0.22, 0.01) | –0.06 (–0.11, 0.00) | –0.08 (–0.13, –0.04) |

| 25–34 years | –0.07 (–0.17, 0.03) | 0.00 (–0.05, 0.05) | –0.03 (–0.07, 0.01) |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.19 (0.09, 0.29) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.14) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) |

| 2 children | 0.16 (0.07, 0.24) | 0.04 (–0.00, 0.09) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.11) |

| Receipt of tetanus vaccine | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.03 (–0.01, 0.06) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.05) |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.14 (–0.22, –0.06) | –0.08 (–0.13, –0.03) | –0.05 (–0.11, –0.00) |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.05 (–0.07, 0.17) | 0.04 (–0.02, 0.09) | –0.02 (–0.06, 0.02) |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.03 (–0.16, 0.10) | –0.05 (–0.12, 0.03) | –0.02 (–0.09, 0.04) |

| 25–34 years | 0.08 (–0.03, 0.19) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.09) | –0.04 (–0.09, 0.02) |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.16 (0.06, 0.28) | 0.13 (0.07, 0.19) | 0.12 (0.06, 0.17) |

| 2 children | 0.17 (0.07, 0.26) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.14) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.15) |

| Receipt of blood pressure measurement | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.01 (–0.01, 0.04) | 0.06 (0.04, 0.07) | |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.09 (–0.16, –0.02) | –0.04 (–0.11, 0.03) | |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.11 (0.04, 0.18) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | |

| Maternal age (reference, 35-49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.19 (–0.29, –0.08) | –0.03 (–0.12, 0.05) | |

| 25–34 years | 0.03 (–0.06, 0.12) | –0.07 (–0.14, 0.00) | |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.29 (0.19, 0.37) | 0.00 (–0.07, 0.07) | |

| 2 children | 0.19 (0.11, 0.27) | –0.03 (–0.10, 0.03) | |

| Receipt of urine examination | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.00 (–0.08, 0.07) | –0.04 (–0.13, 0.04) | |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.21 (0.13, 0.29) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15) | |

| Maternal age (reference, 35-49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.15 (–0.26, –0.03) | 0.07 (–0.03, 0.17) | |

| 25–34 years | –0.02 (–0.12, 0.08) | 0.03 (–0.05, 0.12) | |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.24 (0.14, 0.34) | 0.09 (0.01, 0.18) | |

| 2 children | 0.20 (0.11, 0.29) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.12) | |

| Receipt of blood examination | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.04 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.05 (–0.12, 0.02) | 0.02 (–0.06, 0.11) | |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.27 (0.19, 0.35) | 0.11 (0.05, 0.18) | |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.11 (–0.22, 0.00) | –0.00 (–0.11, 0.10) | |

| 25–34 years | 0.00 (–0.09, 0.09) | –0.01 (–0.10, 0.08) | |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.19 (0.10, 0.29) | 0.22 (0.13, 0.31) | |

| 2 children | 0.15 (0.06, 0.24) | 0.09 (0.01, 0.18) | |

| Receipt of HIV testing | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.06) | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.06) | –0.03 (–0.11, 0.05) |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.27 (0.19, 0.34) | 0.24 (0.18, 0.30) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15) |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | 0.01 (–0.07, 0.09) | –0.07 (–0.15, 0.02) | –0.03 (–0.13, 0.07) |

| 25–34 years | 0.00 (–0.07, 0.07) | –0.00 (–0.07, 0.07) | 0.00 (–0.08, 0.08) |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | –0.10 (–0.17, –0.03) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.19) | 0.14 (0.06, 0.22) |

| 2 children | –0.07 (–0.13, –0.01) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.17) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.15) |

| Skilled birth attendance | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.07 (0.04, 0.10) | 0.07 (0.06, 0.08) | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.19 (–0.28, –0.12) | –0.16 (–0.20, –0.12) | –0.01 (–0.05, 0.04) |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.09 (–0.02, 0.21) | –0.03 (–0.72, 0.01) | –0.02 (–0.05, 0.01) |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.15 (–0.28, –0.03) | –0.12 (–0.17, –0.06) | –0.05 (–0.10, –0.00) |

| 25–34 years | –0.04 (–0.15, 0.07) | –0.05 (–0.10, –0.00) | –0.01 (–0.05, 0.04) |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.18 (0.07, 0.29) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.16) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.14) |

| 2 children | 0.08 (–0.15, 0.18) | 0.07 (0.02, 0.11) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) |

| Health-facility-based delivery | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.07 (0.06, 0.09) | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) | |

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | –0.17 (–0.21, –0.13) | 0.00 (–0.04, 0.00) | |

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | –0.02 (–0.06, 0.03) | –0.02 (–0.05, 0.01) | |

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.13 (–0.19, –0.07) | –0.07 (–0.12, –0.02) | |

| 25–34 years | –0.41 (–0.09, 0.01) | –0.01 (–0.06, 0.03) | |

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.16 (0.10, 0.21) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | |

| 2 children | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.12) | |

| Cesarean section delivery | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||

| Per 1 category increase | 0.06 (0.05, 0.08) | ||

| Maternal education (reference, primary or higher) | |||

| Incomplete primary | 0.03 (–0.04, 0.10) | ||

| Place of residence (reference, rural) | |||

| Urban | 0.00 (–0.05, 0.06) | ||

| Maternal age (reference, 35–49 years) | |||

| 15–24 years | –0.21 (–0.29, –0.13) | ||

| 25–34 years | –0.11 (–0.18, –0.04) | ||

| Parity (reference, 3 or more children) | |||

| 1 child | 0.12 (0.05, 0.19) | ||

| 2 children | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.08) | ||

The β values were estimated by multivariable linear regression analyses. All covariates in the table were included in the regression model.

When comparing urban with rural areas, the difference in prevalence declined from 0.11 in 2006 to 0.06 in 2011 for receipt of blood pressure measurement, from 0.21 in 2006 to 0.09 in 2011 for urine examination, from 0.27 in 2006 to 0.11 in 2011 for blood examination, and from 0.27 in 2000 to 0.24 in 2006 and 0.09 in 2011 for HIV testing. For other utilization variables, the difference by place of residence was not significant, except for utilization of antenatal care service in 2011, which showed a significantly higher prevalence in rural areas than in urban areas.

Mothers with 1 child were more likely to utilize all of the seven indicators of reproductive health services than mothers with 3 children or more, except for receipt of blood pressure measurement in 2011 and receipt of HIV testing in 2000.

Discussion

The findings from analysis of three rounds of a large nationally representative survey showed a substantial increase in the utilization of reproductive health services between 2000 and 2011. Both the prevalence ratios and concentration indices showed that inequality in reproductive health services utilization favoring wealthier mothers decreased over time for utilization of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery. On the other hand, an increasing tendency was observed in at least one of the inequality measures for receipt of TT vaccination, blood pressure measurement, urine examination, blood examination, and HIV testing. The cesarean section rate in 2011 was higher than the rate of 15% recommended by the WHO. The utilization rate of cesarean section was found to be higher among the richer women than poorer women.

The overall percentages of utilization of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and delivery at health facilities have achieved reasonable levels, and inequalities in the utilization of these services by wealth status have declined in Vietnam. However, inequalities in utilization of components of reproductive health services continue to favor wealthier women.

Women’s health care in Vietnam has improved over the past several decades. Facilities, hospitals, clinics, and training of medical personnel have all gradually improved, and the improvements have made reproductive health services accessible to all women in the country25, 26). From 2000 to 2011, the number of health-care facilities increased from 13,117 to 13,467 units, and the number of midwifes increased from 142,000 to 268,00027, 28).

There are factors that were not directly captured by the current study that may stand as barriers causing the lower utilization of reproductive health services among poor mothers. These include distance to health facilities as well as a lack of transportation and accommodations for mothers and their family members; shortages of equipment, drugs, and staff at health facilities; informal payments; and a growing private sector, together with a weak public health insurance system, and they are important determinants of the lower rates of reproductive health services utilization, particularly for poor women29-35). Further efforts to improve equality in the utilization of reproductive health services by poor mothers are therefore essential in Vietnam.

The results of the present study showed that rural mothers were less likely to utilize reproductive health services than mothers in urban areas. This finding was consistent with results of several other studies in developing countries28,29,30,31,32), and similar results were also obtained in some previous studies in Vietnam33,34,35). Although reproductive health services in Vietnam have been expanded in the last two decades, their expansion has not promoted health equality because the expansion has largely been in urban centers27, 28). As a result, the utilization of reproductive health services by the poor, particularly by the ethnic minorities in the hills and underserved rural regions, has remained low18).

Our findings also revealed that the differences in prevalence declined for receipt of all three ANC components and HIV testing when comparing urban areas with rural areas. These results are consistent with findings in Bangladesh, where urban and rural differences in the prevalence of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery declined between 1995 and 201036). The present results may be caused by the expansion of reproductive health services in Vietnam in the last decade, particularly those for receipt of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery in rural areas.

Our findings showed the existence of a huge rich-poor gap in HIV testing utilization among pregnant women in Vietnam even during the decade between 2000 and 2011. The low rate of HIV testing utilization even where care is free-of-charge suggests that other factors, such as potential stigma and cultural constraints, have played important roles in discouraging pregnant women from utilizing HIV testing services37). Moreover, the recent financial crisis has resulted in funding cuts for the HIV diagnosis program in Vietnam38,39,40), and for that reason, HIV diagnosis might not be free in some locations in Vietnam, meaning that pregnant women might have to pay. Around half of Vietnamese have a daily income below 2 USD, and nearly a quarter of the population lives below the international poverty line41). Since the cost of an HIV test is substantial, approximately 3 USD, it is a large financial burden for poor women42, 43). Reducing poverty and making services more available and accessible to the poor may be essential to improving the utilization of HIV testing in Vietnam.

The results of our study showed a high cesarean section rate (20%) in 2011. This figure is higher than the WHO’s recommended optimal level (15%)44). Both increased demand and increased supply may act as drivers for such a higher rate of cesarean section delivery in Vietnam. On the demand side, when having one child is the norm, older and rich women may request a cesarean section for reasons such as fear of pain, safety of the child, fast recovery, and better sex life than after vaginal delivery45,46,47,48,49). Our findings also demonstrated that wealthier, one-child, or older (25–49 years) mothers were more likely to utilize cesarean section delivery than the poorest, higher-parity, or younger mothers. On the supply side, the influence of physicians in choosing cesarean section in nonemergency situations has been well documented by previous studies50, 51). Furthermore, many families in Vietnam opt for cesarean section because they want their babies to arrive at a lucky time of day. Further in-depth analyses are needed in order to understand the high rate of cesarean section delivery, particularly that among rich mothers in Vietnam.

As expected, there were positive associations between a primary or higher level of maternal education and the utilization of ANC, skilled birth attendance, health-facility-based delivery, and TT vaccination. Numerous studies conducted in developing countries over the past decade have also shown a nearly universal, positive association between maternal education and the utilization of reproductive health services, and this association has been found in many societies even when the household socioeconomic status remained constant6, 8, 11, 14, 52, 53).

The results of the present study also revealed a significant negative association between higher parity and reproductive health services utilization. This finding is consistent with the results reported by studies6, 54, 55) conducted in other developing countries, in which higher parity mothers were found to be less likely to utilize reproductive health services. Furthermore, mothers in Vietnam who were expecting their third or higher child may have neglected to attend prenatal care sessions for fear of being reprimanded because of the government’s two-child policy, even though this policy was officially abolished in 200356). Thus, this prior policy may have created yet another barrier to the utilization of maternal health services.

Our findings in the present study suggest the need for strategies, programs, and policies that aim to enable and enhance the access of women to reproductive health services and their satisfaction with such services, as well as the need to provide clear information about health services, particularly to women in lower economic strata and those living in rural areas.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the present study is that the data came from three large nationally representative surveys performed in 2000, 2006, and 2011. A national sample of women aged 15–49 years who had given birth to a live infant in the 1 or 2 years preceding the surveys provided a sufficient sample size for the multivariable analysis of most of the outcome variables to be statistically significant as well as for all of the concentration indices to be significantly greater than 0. The standardized questionnaire format was carefully developed to ascertain accurate information from the participants, the interviewers were trained, and the fieldwork was monitored by representatives of the Ministry of Health in Vietnam and UNICEF. Our analyses to measure the household economic statuses of the participants were based on the household wealth index, which is generally considered a good proxy for household economic status, especially in developing country like Vietnam, where it is hard to obtain reliable income and expenditure data. We applied measures of inequality that were appropriate for assessing the long-term trends in inequalities in reproductive health services utilization in Vietnam, and such an assessment is essential to making decisions about future health policy. Evaluation of inequality using various indices enabled us to better interpret the trends by wealth index.

This study had several limitations. The first limitation was that because the data was based on self-report, recall bias may have been possible. However, the recall period was limited to 1 or 2 years to minimize recall bias. Second, three or more ANC visits are recommended 57, 58); however, we could not consider number of visits in our study, as MICS 2000 and MICS 2006 did not collect such information. We would certainly consider this point in future. Third, because no data were available for women aged 15–49 years who had given birth to a live infant in the 2 years preceding the date of the interview in the MICS 2000, we only considered data for eligible women had given birth to a live infant in the 1 year preceding the survey for the year 2000, and this limitation may have led to more accurate information from 2000 data when compared with the MICS 2006 and MICS 2011 data.

Conclusions

Over the 12-year period of 2000 to 2011, inequality in the utilization of ANC, skilled birth attendance, and health-facility-based delivery decreased in Vietnam. The present study showed that utilization of reproductive health services favored wealthier mothers in 2000 and that there was still a persistent wealth gap in reproductive health services utilization in 2011. Higher parity women, women of low education level, women living in rural areas, and younger women had lower likelihoods of reproductive health services utilization.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the teams that conducted the Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990–2010 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation Word Health Statistics 2012. WHO Library Cataloguing-in- Publication. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Bank: Vietnam overview [http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview].

- 4.Vietnam Ministry of Health Joint Annual Health Review 2010. Hanoi: Ministry of Health (MoH); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. Millennium Development Goals. [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs290/en/].

- 6.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering groupMaternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006; 368: 1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingle A, Powell-Jackson T, Goodman C. A decade of improvements in equity of access to reproductive and maternal health services in Cambodia, 2000-2010. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 51. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molina HF, Nakamura K, Kizuki M. Reduction in inequality in antenatal-care use and persistence of inequality in skilled birth attendance in the Philippines from 1993 to 2008. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002507. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman M, Haque SE, Mostofa MG. Wealth inequality and utilization of reproductive health services in the Republic of Vanuatu: insights from the multiple indicator cluster survey, 2007. Int J Equity Health 2011; 10: 58. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathak PK, Singh A, Subramanian SV. Economic inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992-2006. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e13593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Sirilak S. Trends and inequities in where women delivered their babies in 25 low-income countries: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Reprod Health Matters 2011; 19: 75–85. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37564-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axelson H, Gerdtham UG, Ekman B. Inequalities in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health in Vietnam: a retrospective study of survey data for 1997-2006. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 456. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Say L, Raine R. A systematic review of inequalities in the use of maternal health care in developing countries: examining the scale of the problem and the importance of context. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 812–819. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.035659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houweling TA, Ronsmans C, Campbell OM. Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: an international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 745–754. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.038588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collin SM, Anwar I, Ronsmans C. A decade of inequality in maternity care: antenatal care, professional attendance at delivery, and caesarean section in Bangladesh (1991-2004). Int J Equity Health 2007; 6: 9. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zere E, Tumusiime P, Walker O. Inequities in utilization of maternal health interventions in Namibia: implications for progress towards MDG 5 targets. Int J Equity Health 2010; 9: 16. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran TK, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HD. Urban - rural disparities in antenatal care utilization: a study of two cohorts of pregnant women in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res 2011; 11: 120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goland E, Hoa DT, Målqvist M. Inequity in maternal health care utilization in Vietnam. Int J Equity Health 2012; 11: 24. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Målqvist M, Lincetto O, Du NH. Maternal health care utilization in Vietnam: increasing ethnic inequity. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91: 254–261. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.112425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health, Government of Vietnam Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2000, Final Report. Hanoi, Vietnam; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Government of Vietnam Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006, Final Report. Hanoi, Vietnam; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health, Government of Vietnam Vietnam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2011, Final Report. Hanoi, Vietnam; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagstaff A, Paci P, van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 1991; 33: 545–557. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90212-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erreygers G. Correcting the concentration index. J Health Econ 2009; 28: 504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health, Government of Vietnam. Vietnam’s national strategy on reproductive health care for the 2001-2010 periods. [http://www.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/English/strategies/strategiesdetails?categoryId=29&articleId=3034].

- 26.Ministry of Health, Government of Vietnam National master plan on safe motherhood 2003-2010. Hanoi; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vietnam General Statistics Office Vietnam statistical yearbook of Vietnam 2005. Statistical publishing house. Hanoi; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vietnam General Statistics Office Vietnam statistical yearbook of Vietnam 2011. Statistical publishing house. Hanoi; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jahn A, Dar Iang M, Shah U. Maternity care in rural Nepal: a health service analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5: 657–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abel-Smith B, Rawal P. Can the poor afford ‘free’health services: a case study of Tanzania. Health Policy Plan 1992; 7: 329–341. doi: 10.1093/heapol/7.4.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahar S, Costello A. The hidden cost of ‘free’ maternity care in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan 1998; 13: 417–422. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.4.417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haque SE, Rahman M, Mostofa MG. Reproductive health care utilization among young mothers in Bangladesh: does autonomy matter? Womens Health Issues 2012; 22: e171–e180. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shelah S. Bloom, David W, Monica DG. Dimensions of Women’s Autonomy and the Influence on Maternal Health Care Utilization in a North Indian City. JSTOR 2001; 38: 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Målqvist M, Hoa DT, Thomsen S. Causes and determinants of inequity in maternal and child health in Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 641. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graner S, Mogren I, Duong Q. Maternal health care professionals’ perspectives on the provision and use of antenatal and delivery care: a qualitative descriptive study in rural Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 608. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajizadeh M, Alam N, Nandi A. Social inequalities in the utilization of maternal care in Bangladesh: Have they widened or narrowed in recent years? Int J Equity Health 2014; 13: 120. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0120-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinh LT, Dibley MJ, Byles J. Determinants of antenatal care utilization in three rural areas of Vietnam. Public Health Nurs 2007; 24: 300–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Assembly Law on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control. In 64/2006/QH11. Hanoi; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le CT, Vu TT, Luu MC. Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Vietnam: an assessment of progress and future directions. J Trop Pediatr 2008; 54: 225–232. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNIAIDS & World Bank The Global Economic Crisis and HIV Prevention and Treatment Programmers: Vulnerabilities and Impact. Geneva; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.United Nations Millennium Development Goals Report. Vietnam; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.UNDP Human Development Report. Vietnam; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanh NT, Gammeltoft TM, Rasch V. Number and timing of antenatal HIV testing: evidence from a community-based study in Northern Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health OrganizationAppropriate technology for birth. Lancet 1985; 2: 436–437. 2863457 [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Connell MP, Lindow W. Caesarean section controversy. Further research is needed on why rates of caesarean section are increasing. BMJ 2000; 320: 1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng XL, Xu L, Guo Y. Factors influencing rising ceasarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ 2012; 90: 30–39. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.090399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lei H, Wen SW, Walker M. Determinants of caesarean delivery among women hospitalized for childbirth in a remote population in China. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003; 25: 937–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sufang G, Padmadas SS, Fengmin Z. Delivery settings and caesarean section rates in China. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 755–762. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.035808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collard TD, Diallo H, Habinsky A. Elective cesarean section: why women choose it and what nurses need to know. Nurs Womens Health 2008; 12: 480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2008.00382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hantoushzadeh S, Rajabzadeh A, Saadati A. Caesarean or normal vaginal delivery: overview of physicians’ self-preference and suggestion to patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009; 280: 33–37. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0858-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner M. Choosing caesarean section. Lancet 2000; 356: 1677–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03169-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Titaley CR, Dibley MJ, Roberts CL. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shariff A, Singh G. Determinants of Maternal Health care Utilization in India: Evidence from a Recent Household Survey. Edited by no.85 S. New Dehli: National Council of Applied Economic Research; 2002.

- 54.Ochako R, Fotso JC, Ikamari L. Utilization of maternal health services among young women in Kenya: insights from the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2003. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011; 11: 1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tey NP, Lai SL. Correlates of and barriers to the utilization of health services for delivery in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The Scientific World J 2013; Doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Standing committee of the national assembly Ordinance on Population. In: 06/2003/PL-UBTVQH11 on 9/1/2003 Edited by National Assembly Office. Hanoi; 2003.

- 57.Villar J, Ba’aqeel H, Piaggio G. WHO Antenatal Care Trial Research GroupWHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet 2001; 357: 1551–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04722-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ministry of Health National clinical guidelines on reproductive health care services. Volume 3367/QD-BYT, Medical Publising House, Hanoi, 2003; 45–56. [Google Scholar]