Abstract

Benign esophageal strictures refractory to the conventional balloon or bougie dilatation may be subjected to various adjunctive modes of therapy, one of them being endoscopic incisional therapy (EIT). A proper delineation of the stricture anatomy is a prerequisite. A host of electrocautery and mechanical devices may be used, the most common being the use of needle knife, either standard or insulated tip. The technique entails radial incision and cutting off of the stenotic rim. Adjunctive therapies, to prevent re-stenosis, such as balloon dilatation, oral or intralesional steroids or argon plasma coagulation can be used. The common strictures where EIT has been successfully used are Schatzki’s rings (SR) and anastomotic strictures (AS). Short segment strictures (< 1 cm) have been found to have the best outcome. When compared with routine balloon dilatation, EIT has equivalent results in treatment naïve cases but better long term outcome in refractory cases. Anecdotal reports of its use in other types of strictures have been noted. Post procedure complications of EIT are mild and comparable to dilatation therapy. As of the current evidence, incisional therapy can be used for management of refractory AS and SR with relatively short stenosis (< 1 cm) with good safety profile and acceptable long term patency.

Keywords: Endoscopic incisional therapy, Esophageal strictures, Anastomotic strictures, Needle knife, Radial incision and cutting

Core tip: Benign esophageal strictures refractory to conventional balloon or bougie dilatation can be subjected to endoscopic incisional therapy. The technique entails the use of needle knife or scissors for radial incision and cutting off of the stenotic rim. Adjunctive therapies with balloon dilatation or intralesional steroids may be needed for prevention of re-stenosis. Current evidence suggests use of incisional therapy for refractory short segment (< 1 cm) anastomotic strictures and Schatzki’s rings with good safety profile and acceptable long term patency.

INTRODUCTION

Benign esophageal strictures are a frequent challenge for the endoscopist. Peptic injury secondary to chronic acid exposure accounts for 80% of all benign esophageal strictures[1]. However, the remaining 20%-30% may be associated with Schatzki’s rings (SR), esophageal webs, post radiation injury, anastomotic strictures (AS) and caustic ingestion. Based on anatomical complexity the strictures are classified as either simple or complex[2]. Simple are those with short, straight strictures, usually allowing passage of normal diameter endoscopes and are easy to treat (webs, rings and peptic strictures). The difficult to treat complex strictures are longer (> 2 cm), angulated or with severely stenosed lumen, a consequence of fibrosis with cicatricial narrowing. AS, caustic strictures and radiation strictures are known to be complex strictures[2]. Dilatation by bougie or balloon dilators has been the age old technique for management of benign esophageal strictures and generally the simple ones respond adequately to 1-3 dilatations[3]. The more difficult ones require more sessions of dilatations or the need for additional modes of treatment. Henceforth, Kochman et al[4] have defined strictures as: (1) refractory, when there was a persisting dysphagia score of 2 or more, as a result of inability to successfully achieve a diameter of 14 mm over 5 sessions at 2 wk intervals; and (2) recurrent, when there was inability to maintain a satisfactory luminal diameter for 4 wk once the target diameter of 14 mm had been achieved.

Although dilatation is a time tested, safe and effective mode of therapy for esophageal strictures, 10% of patients may require repeated dilatations[4,5] and 90% of those who have a single recurrence will eventually develop further recurrence. Moreover, dilatation failure group will require adjunctive modes of therapy. The various endoscopic options (Table 1) besides dilatation are intralesional steroid injection[6-8] or topical mitomycin C[9,10], esophageal stenting (self-expanding metal stents[11-13], self-expanding plastic stents[14,15] and biodegradable stents[16-19]), rendezvous procedure (antegrade and retrograde dilatation)[20,21] and incisional therapy.

Table 1.

Endoscopic options of esophageal stricture management

| Dilatation |

| Balloon |

| Bougie |

| Dilatation with injection therapy |

| Intralesional triamcinolone |

| Topical mitomycin C |

| Incisional therapy |

| Stent placement |

| SEMS |

| SEPS |

| Biodegradable stents |

| Rendezvous procedure |

SEMS: Self expanding metal stents; SEPS: Self expanding plastic stents.

Limited literature exists on endoscopic incisional therapy (EIT) and this review will deal with indications, techniques and the outcome of this modality in the management armamentarium of benign esophageal strictures.

DESCRIBED USES OF EIT

After the first description of its utility by Raskin et al[22] for Schatzki’s ring in 1985, incisional therapy has been found to be useful in a number of other causes such as AS[23-25], strictures after esophageal endoscopic sub mucosal dissection (ESD) or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[26,27], corrosive strictures[28], upper esophageal webs[29] and a host of other benign strictures.

TECHNICAL DETAILS OF INCISIONAL THERAPY

Pre procedure assessment

Before subjecting a patient to EIT a proper assessment of the indication, the suitability of the procedure and the safety of the patient has to be done. The baseline symptom profile including the grade of dysphagia has to be recorded. Usually, strictures refractory to conventional modes of therapy are subjected to EIT as use of EIT for naive strictures (without prior dilatation therapy) has not been found to be superior to the conventional dilatation[30]. Active inflammation or underlying malignancy has to be ruled out with histology. Contrast esophagography and cross sectional imaging are needed for proper delineation of the stricture anatomy. The diameter of the stricture can be roughly estimated on endoscopy as: (1) size of 10 mm or more if a standard endoscope tip can be passed (GIF-H180 with insertion tube diameter of 9.8 mm; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan); (2) size of 5-10 mm if standard ultrathin scope can be passed (GIF-N180 with insertion tube diameter of 4.9 mm); (3) size of 2-5 mm if the ultrathin scope cannot be passed; and (4) less than 2 mm (pin point strictures) if the outer sheath of the needle-knife catheter (1.7-mm needle diameter) (Wilson Cook Medical Inc, Winston-Salem, NC) can just be passed or not pass through. The depth of the lesion is assessed by comparing with the length of the needle knife (approximately 4 mm). This documentation will help in outcome assessment post therapy. Finally, patients with bleeding diathesis, respiratory failure, severe or unstable cardiac disease and anastomotic leakage or infection need correction of these risk factors before therapy.

Instruments required

EIT has been carried with a host of electrocautery and mechanical devices including polypectomy snares and argon plasma coagulation[31]. However, the most widely used are the needle knives that are nothing but “naked” diathermy wires[32]. The standard needle knife designed for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreaticography is a diathermy wire that protrudes out of the catheter sheath by a handle mechanism and electrocautery is done powered by electrosurgical generators. This free hand technique is a cause of concern for fear of perforation. To minimize this risk, a modification has been made with the addition of an insulated ceramic tip (insulated tip needle knife, IT knife) allowing only cutting at the side. Other modifications such as the hook tip knife can also be used[32].

Mechanical devices that have been used are the Heiss-Device flexible endoscopic scissors (Telemed Systems, Hudson, Mass) and the FS-3L-1, endoscopic suture scissors (Olympus America Corp, Melville, NY).

A combined mechanical and electrocautery device, originally devised for ESD, known as SB Knife Jr (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan) has also been used. It is a scissor-type knife with rotatable monopolar scissors and insulated coating for enhanced incision power while protecting surrounding tissues. A comprehensive table of the various instruments with their specifications has been depicted in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Instruments for incisional therapy

| Distal tip outer diameter (Fr) | Knife length (mm) | Knife diameter (mm) | Min. channel size (mm) | Working length (cm) | |

| Needle knives | |||||

| Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) | |||||

| Triple lumen needle knife | 5 | 5 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 195 |

| Hook knife | Hook length 1.3 mm | 4.5 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 165/230 |

| Needle knife (require handle) | |||||

| KD-10Q-1.B | NA | 3 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 195 |

| KD-11Q-1.B | NA | 3 | 0.7 (flat) | 2.0 | 195 |

| IT-Knife-L | Ceramic tip with diameter 2.2 mm | 4 | 0.4 | 2.6 | |

| Boston scientific (Natick, Mass) | |||||

| RX needle knife | 5.5 | 5 | 200 | ||

| MicroknifeTMXL triple lumen knife | 7-5.5 | 200 | |||

| Cook medical (Winston Salem, NC) | |||||

| Fusion needle knife | 6 | 4 | 4.2 | 200 | |

| Zimmon needle | 5 | 7 | 2.0 | 200/320 | |

| Scissors | |||||

| Surgical scissors FS-3L-1 (Olympus): Min. channel size - 2.8 mm Working length - 165 cm | |||||

| Heiss-Device flexible endoscopic scissors (Telemed Systems, Hudson, Mass): 1.7 mm blade diameter × 2.5 mm blade length 1.7 mm shaft diameter 180 cm shaft length Single-action blade | |||||

| SB knife Jr (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan): Width 4.4 mm × Length 3.5 mm Rotatable monopolar scissors | |||||

Fr: French; NA: Not applicable; IT knife: Insulated tip knife.

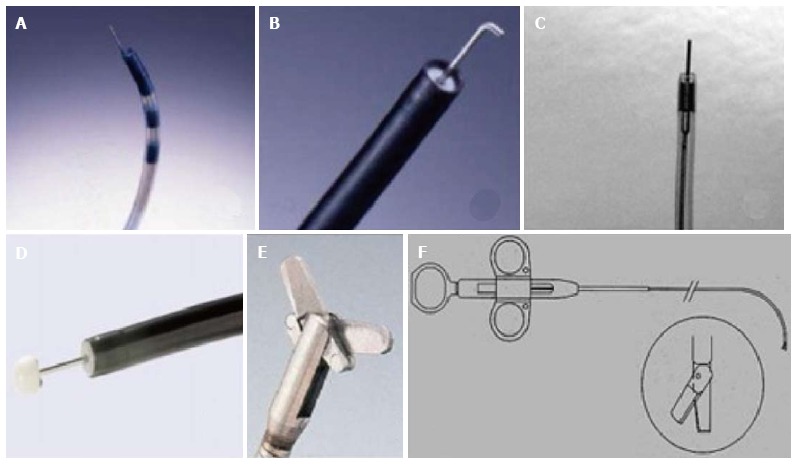

Figure 1.

Accessories for incisional therapy. A: Triple lumen needle knife; B: Hook knife; C: Needle knife (KD 10Q); D: Insulated tip knife; E: Endoscopic surgical scissors (Image courtesy of Olympus); F: Heiss-Device flexible endoscopic scissors (image courtesy of Telemed systems).

The technique

First applied to SR, the most commonly used incisional therapy is the needle knife electroincision and will be dealt with in detail here. Although most commonly the standard needle knife is used, with the advent of various modifications, the IT-knife is preferred for short strictures[32]. The basic principle of this modality is the same as dilatation, i.e., disruption or displacement of the fibrotic tissue to help restore a satisfactory lumen diameter and prevent the reorganization of the fibrotic tissue.

The electroincision requires use of radial incisions with the knife attached to an electrosurgical unit such as UES-30 generator (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or more commonly ERBE generator (Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) with software controlled fractionated cuts either in the pure cut or blended cut modes.

The technique used has been essentially the application of radial incision of the stricture area and was rechristened with the term of “radial incision and cutting” (RIC) method by Muto et al[25] RIC is carried out in the following steps (Figure 2): (1) The stricture area is incised under direct vision with the needle knife in a radial fashion parallel to the longitudinal axis of the esophagus. Usually a virtual line connecting the cranial and the caudal sides of the lumen is presumed and the incision line is guided accordingly. Precise movement is imperative for appropriate use of needle knife and can be achieved better with the endoscope tip movement rather than the needle itself; (2) The length and the number of incisions are guided by the need to completely remove the rim of stenosis. On an average, 8-12 radial incisions are needed[24]. The incision depth is assessed using the needle-knife length as a comparator; (3) While for short segment strictures, the technique is pretty straight forward, but for long segment ones, many times an opening needs to be created with multiple, short radial incisions before the scope can be negotiated for distal segments. Thus, technically difficult as it is for long segment ones, complete removal of the stenosed rim may not always be feasible; and (4) The parts of the strictured site in between the incision lines are then sliced off using the knife and the procedure is usually terminated once the scope can be easily passed across the strictured segment.

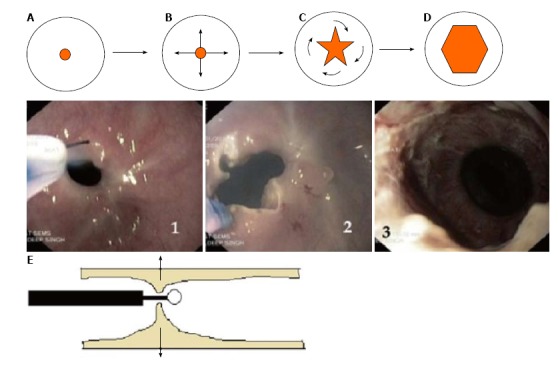

Figure 2.

The technique of endoscopic incisional therapy procedure. A-D: Schematic front view of stricture site; B: Arrows depict the radial direction of incision; C: Curved arrows depict the slicing off of the intervening areas; D: Final outcome at the end of procedure; E: Lateral view of stricture site depicting the transverse working domain of the needle knife (arrows); 1: Use of needle knife for incision; 2: After radial incision; 3: At the end of EIT and balloon dilatation. EIT: Endoscopic incisional therapy.

A modification to the technique proposed by Lee et al[24] was the use of a transparent hood attached to the scope tip for better visualization of the work field.

Post-procedure the patients are observed for immediate complications such as pain, significant bleeding or perforation. Once these have been ruled out, the patients can be discharged and assessed on a regular basis for recurrence of symptoms, grade of dysphagia or weight loss for which repeat assessment and redo of the therapy may be needed. Similar to the needle knife used for EIT various other devices such as the polypectomy snare[31] or scissors[28,33] have also been used.

Adjunctive measures

In the post-procedure phase, when the tissue has been freshly incised and chances of re-formation of stenosing fibrotic scar are high, various adjunctive measures have been described. Endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) with CRE balloon dilators (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) have been done post-procedure and repeated frequently till the scarring of the cut surface[23,25,27]. Nonaka et al[28] have described the use of oral steroids for the prevention of re-stenosis. Yamaguchi et al[34] also demonstrated prevention of stricture after ESD with prednisolone. It has already been established in literature that use of intralesional steroids can prevent stricture recurrence[6-8]. The study of the efficacy of the same after EIT is currently being carried out in a large multi-center randomized control trial in Japan (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000014017). Argon plasma coagulation use has also been described along with incision for stepwise reduction of the scar tissue[31].

Evaluation of the treatment outcome

Recurrence of symptoms with dysphagia more than grade II or the inability to pass a standard endoscope (9.5 mm) across the stricture site is considered as recurrent stenosis. If this condition arises even after 5 sessions of EIT, it is considered as treatment failure[30]. Post-procedure relief of symptoms, need for repeat procedure and the long term patency are factors assessed for the efficacy assessment of the procedure.

OUTCOME OF INCISIONAL THERAPY

The incisional therapy has been an alternate modality for the management of benign refractory strictures. The average time required for the procedure ranges from 6-14 min[24,25]. The majority of the published studies describe its use primarily in SR and AS. Anecdotal case reports have been found of its use in other conditions.

SR

After the first description of electrosurgical incision of SR by Raskin et al[22] in 1985, various studies have used it. When used as the initial intervention modality for SR (i.e., without prior dilatation therapy), Guelrud et al[35] produced excellent results with 14 out of 17 patients (82.4%) becoming asymptomatic after a single session of EIT during a follow up of 46 mo. In the dilatation unresponsive group, Burdick et al[36] showed improvement in dysphagia in 6 out of 7 patients (85.7%) after a single session of EIT over a 36 mo follow-up, however later studies failed to replicate a similar outcome. DiSario et al[37] conducted EIT on 11 patients, who had a median of 3 dilatations prior to incision, out of whom 4 (36%) remained symptom free but 7 (64%) required further incisions or dilatations during a median follow-up of 55 mo. However, they found that there was a significant increase in the mean duration of improvement immediately after incision as compared with that of dilatation (17 mo vs 5 mo; P = 0.034).

In a prospective randomized study, comparing bougie dilatation with EIT as the initial therapy for symptomatic SR, Wills et al[38] demonstrated that both modalities had similar efficacy in symptom control, dysphagia and GERD, during a 12 mo follow-up period. However, the EIT group had longer symptom free survival time compared with the bougie dilatation group (7.99 mo vs 5.86 mo; P = 0.03).

AS

The most common esophageal stricture variant where EIT has been studied is the anastomotic stricture, mostly esophago-gastric anastomosis. Esophageal AS develops in 5%-46% of patients after surgical resection[2,39] and is secondary to post-operative complications such as bleeding, fistulization, leak development, anastomotic site infection and ischemia of the gastric anastomosis[2,39,40]. The success of balloon dilatation ranges from 70%-90% while 40% require more than 3 dilatations for optimal result[39-41]. A viable alternate management option has been the use of EIT as demonstrated in various studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Various studies of incisional therapy in esophageal anastomotic stricture

| Ref. | Type of stricture | No. of patients | Length of stricture | No. of pre-procedure dilatations1 | Follow-up duration (mo) | Outcome of single session |

| Schubert et al[31], 2003 | Treatment naive | 15 | 6.1 mm | NA | 23 | No recurrence - 14/15 (93%) |

| (3-10 mm) | ||||||

| Simmons et al[23], 2006 | Refractory | 9 | -- | 6 | 3-14 | No dysphagia - 4/9 (44.4%) |

| No response - 1/9 (11%) | ||||||

| Hordijk et al[42], 2006 | Refractory | 20 | < 1 cm - 12 cm | 8 | 12 | No dysphagia - 12/20 (60%) |

| > 1 cm - 8 cm | Recurrence - 8/20 (40%) | |||||

| Treatment failure - 2/20 (10%) | ||||||

| 2Hordijk et al[30], 2009 | Treatment naive | EIT arm - 31 | EIT arm - 1.35 cm | N/A | 6 | No difference in the success rate (80.6% vs 67.7%) |

| SB arm - 31 | SB arm - 0.55 cm (mean) | Treatment failure- EIT arm - 1; SB arm - 5 | ||||

| Lee et al[24], 2009 | Treatment naive | 24 | < 1 cm - 21 cm | N/A | 24 | No recurrence - 21/24 (87.5%) |

| > 1 cm - 3 cm | Restricture - 3/24 (12.5%) | |||||

| Muto et al[25], 2012 | Refractory | EIT - 32 | ≤ 5 mm - 49 mm | 10 | EIT - 14.8 | Short term - 93.8% improvement |

| EBD - 22 | > 5 mm - 5 mm | EBD - 17.2 | Long term - EIT better than EBD |

Mean number of dilatations;

Randomized prospective study. Treatment naïve: No previous dilatation; EIT: Endoscopic incisional therapy; SB: Savary bougienage; EBD: Endoscopic balloon dilatation; NA: Not applicable.

In cases of treatment naïve patients, after a single session of EIT, recurrence free course over a 6-24 mo follow up has been found to be 80.6% to 93%[24,30,31]. Thus, it is quite an effective therapy compared to dilatation without the need for repeated sessions for a considerable period of time. In fact, in a comparative trial with bougie dilatation, Hordijk et al[30] demonstrated that both EIT and dilatation were equally efficacious (80.6% vs 67.7%) at 6 mo follow-up.

In the more difficult group of refractory strictures, the symptom free rate dropped to 60% to 65%[25,42] with 44% requiring re-treatment. However, when compared to continued dilatation therapy, EIT performed better than dilatation with significantly higher patency rates at 6 mo (65.3% vs 19.8%, P < 0.005) and 12 mo (61.5% vs 19.8%, P < 0.005) follow-up[25].

The other most important contributor of EIT response is the length of the stricture. Hordijk et al[42] had demonstrated that while patients with stricture length less than 1 cm had recurrence free course, all patients with stricture length greater than 1 cm had recurrence. Similar finding has been shown by Lee et al[24] wherein only 4.8% patients with stricture < 1 cm had re-stricture as compared to 66.7% in the group with stricture > 1 cm. This has been attributed to the increased amount of fibrosis in the longer strictures and hence decreased response.

Other strictures

In a retrospective study of 8 patients with post chemo-radiotherapy, ESD or EMR induced strictures, EIT improved dysphagia in all patients in the immediate post-procedure phase but 3 mo lumen patency was seen in only 3 (37.5%) patients[26].

Anecdotal case reports of use of endoscopic scissors have been used for management of corrosive strictures[28] and fibrous scar in proximal esophagus[33]. Stricture after surgery for esophageal atresia in a 4-year-old child has also been reported to be managed with EIT along with stenting[43].

Author’s experience

A total of 14 patients with benign esophageal strictures (AS 5, corrosive strictures 4) have been subjected to incisional therapy along with balloon dilatation. Incisional therapy was done with Microknife™ XL Triple lumen knife (Boston Scientific, Natick, United States) followed by balloon dilatation with CRE™ Balloon Dilator (Boston Scientific, Natick, United States). Successful dilatation was achieved in 11 of the 14 after 3-9 sessions. No complications were noted.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications of EIT include pain, bleeding or perforation. Perforation is the most dreaded complication and can occur because of inability to gauge the depth of the esophageal wall or the length of the stricture during the incision therapy. Bleeding is usually self-limited and lesser known complication as the fibrotic strictures subjected to incisional therapy are relatively avascular. The complication rate of EIT appears to be mild comparable to dilatations with bougies or balloons, which can have perforation or significant hemorrhage at a rate of 0.1% to 0.4%[3]. For EIT, the reported perforation rate ranges from 0%-3.5%[24,25,30,37,42] with no reported evidence of significant bleeding. Perforation can be managed essentially with conservative treatment and if it fails, can be subjected to stent placement or surgery. Bleeding can be easily managed with methods such as balloon tamponade. Thus, EIT is a safe therapeutic option for stricture management.

CURRENT STATUS OF INCISIONAL THERAPY

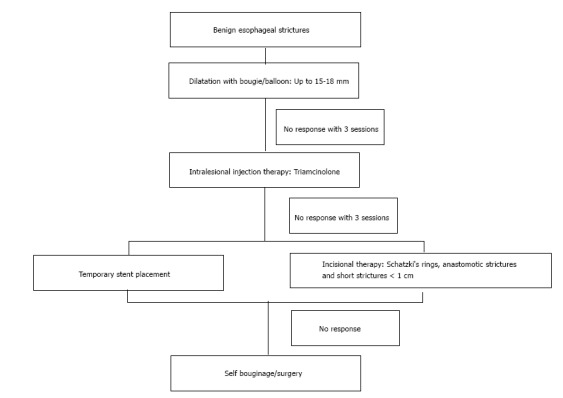

As of the current evidence, EIT can be used as a treatment modality for refractory SR and AS with relatively short stenosis (< 1 cm). A suggested algorithm for the management of benign strictures has been shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the management of benign esophageal strictures.

AREAS OF FUTURE RESEARCH

A number of questions need to be answered through larger trials before a standardized recommendation can be made regarding the use of incisional therapy in esophageal stricture management: (1) it can be used for all refractory strictures; (2) number of balloon or bougie dilatations before considering EIT; (3) cumulative risk of the procedure; (4) efficacy and applicability of instruments other than needle knife; (5) the choice of adjunctive therapy to prevent re-stenosis; (6) cost effectiveness of the therapy in the long run; and (7) technical expertise and applicability issues in day-to-day practice.

CONCLUSION

EIT is a feasible, safe and effective treatment modality for benign short refractory esophageal strictures with established evidence in SR and AS. It has good immediate symptom improvement with acceptable long-term patency.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Espinel J, Tander B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 1, 2015

First decision: August 25, 2015

Article in press: November 4, 2015

References

- 1.Pasha SF, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lew RJ, Kochman ML. A review of endoscopic methods of esophageal dilation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:117–126. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira-Lima JC, Ramires RP, Zamin I, Cassal AP, Marroni CA, Mattos AA. Endoscopic dilation of benign esophageal strictures: report on 1043 procedures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1497–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochman ML, McClave SA, Boyce HW. The refractory and the recurrent esophageal stricture: a definition. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:474–475. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Boeckel PG, Siersema PD. Refractory esophageal strictures: what to do when dilation fails. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2015;13:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s11938-014-0043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holder TM, Ashcraft KW, Leape L. The treatment of patients with esophageal strictures by local steroid injections. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:646–653. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(69)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochhar R, Ray JD, Sriram PV, Kumar S, Singh K. Intralesional steroids augment the effects of endoscopic dilation in corrosive esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:509–513. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochhar R, Makharia GK. Usefulness of intralesional triamcinolone in treatment of benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:829–834. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Asmar KM, Hassan MA, Abdelkader HM, Hamza AF. Topical mitomycin C application is effective in management of localized caustic esophageal stricture: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1621–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagaich N, Nijhawan S, Katiyar P, Sharma R, Rathore M. Mitomycin-C: ‘a ray of hope’ in refractory corrosive esophageal strictures. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:203–205. doi: 10.1111/dote.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eloubeidi MA, Talreja JP, Lopes TL, Al-Awabdy BS, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Success and complications associated with placement of fully covered removable self-expandable metal stents for benign esophageal diseases (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eloubeidi MA, Lopes TL. Novel removable internally fully covered self-expanding metal esophageal stent: feasibility, technique of removal, and tissue response in humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1374–1381. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirdes MM, Siersema PD, Houben MH, Weusten BL, Vleggaar FP. Stent-in-stent technique for removal of embedded esophageal self-expanding metal stents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:286–293. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Repici A, Hassan C, Sharma P, Conio M, Siersema P. Systematic review: the role of self-expanding plastic stents for benign oesophageal strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1268–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ham YH, Kim GH. Plastic and biodegradable stents for complex and refractory benign esophageal strictures. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:295–300. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito Y, Tanaka T, Andoh A, Minematsu H, Hata K, Tsujikawa T, Nitta N, Murata K, Fujiyama Y. Usefulness of biodegradable stents constructed of poly-l-lactic acid monofilaments in patients with benign esophageal stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3977–3980. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basha J, Appasani S, Vaiphei K, Gupta V, Singh K, Kochhar R. Biodegradable stents: truly biodegradable with good tissue harmony. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E116–E117. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirdes MM, Siersema PD, van Boeckel PG, Vleggaar FP. Single and sequential biodegradable stent placement for refractory benign esophageal strictures: a prospective follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:649–654. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Boeckel PG, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD. A comparison of temporary self-expanding plastic and biodegradable stents for refractory benign esophageal strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bueno R, Swanson SJ, Jaklitsch MT, Lukanich JM, Mentzer SJ, Sugarbaker DJ. Combined antegrade and retrograde dilation: a new endoscopic technique in the management of complex esophageal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:368–372. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lew RJ, Shah JN, Chalian A, Weber RS, Williams NN, Kochman ML. Technique of endoscopic retrograde puncture and dilatation of total esophageal stenosis in patients with radiation-induced strictures. Head Neck. 2004;26:179–183. doi: 10.1002/hed.10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raskin JB, Manten H, Harary A, Redlhammer DE, Rogers AI. Transendoscopic electrosurgical incision of lower esophageal (Schatzki) rings: a new treatment modality. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:391–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(85)72257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simmons DT, Baron TH. Electroincision of refractory esophagogastric anastomotic strictures. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:410–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TH, Lee SH, Park JY, Lee CK, Chung IK, Kim HS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Hong SJ, Lee MS. Primary incisional therapy with a modified method for patients with benign anastomotic esophageal stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muto M, Ezoe Y, Yano T, Aoyama I, Yoda Y, Minashi K, Morita S, Horimatsu T, Miyamoto S, Ohtsu A, et al. Usefulness of endoscopic radial incision and cutting method for refractory esophagogastric anastomotic stricture (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yano T, Yoda Y, Satake H, Kojima T, Yagishita A, Oono Y, Ikematsu H, Kaneko K. Radial incision and cutting method for refractory stricture after nonsurgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Endoscopy. 2013;45:316–319. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamino H, Machida H, Tominaga K, Sugimori S, Okazaki H, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, et al. Endoscopic radial incision and cutting method for refractory esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial esophageal carcinoma. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:200–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nonaka K, Ban S, Aikawa M, Yamasaki A, Okuda A, Kounoe T, Naoe H, Sakurai K, Miyazawa M, Kita H, et al. Electrocautery therapy combined with oral steroid administration for refractory corrosive esophageal stenosis prevents restenosis. Esophagus. 2013;10:230–234. doi: 10.1007/s10388-013-0375-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtaka M, Kobayashi S, Yoshida T, Yamaguchi T, Uetake T, Sato T, Hayashi A, Kanai M, Yamamoto T, Hatsushika K, et al. Use of Sato’s curved laryngoscope and an insulated-tip knife for endoscopic incisional therapy of esophageal web. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:522–526. doi: 10.1111/den.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hordijk ML, van Hooft JE, Hansen BE, Fockens P, Kuipers EJ. A randomized comparison of electrocautery incision with Savary bougienage for relief of anastomotic gastroesophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schubert D, Kuhn R, Lippert H, Pross M. Endoscopic treatment of benign gastrointestinal anastomotic strictures using argon plasma coagulation in combination with diathermy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1579–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron TH. Snares, Knives, and Scissors. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;8:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beilstein MC, Kochman ML. Endoscopic incision of a refractory esophageal stricture: novel management with an endoscopic scissors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:623–625. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T, Hayashi T, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Shikuwa S, Kohno S, Nakao K. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guelrud M, Villasmil L, Mendez R. Late results in patients with Schatzki ring treated by endoscopic electrosurgical incision of the ring. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:96–98. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(87)71518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burdick JS, Venu RP, Hogan WJ. Cutting the defiant lower esophageal ring. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:616–619. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiSario JA, Pedersen PJ, Bichiş-Canoutas C, Alder SC, Fang JC. Incision of recurrent distal esophageal (Schatzki) ring after dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:244–248. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wills JC, Hilden K, Disario JA, Fang JC. A randomized, prospective trial of electrosurgical incision followed by rabeprazole versus bougie dilation followed by rabeprazole of symptomatic esophageal (Schatzki‘s) rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:808–813. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Honkoop P, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Stassen LP, Hop WC, van Blankenstein M. Benign anastomotic strictures after transhiatal esophagectomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy: risk factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:1141–1146; discussion 1147-1148. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(96)70215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeya T, Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Tanahashi Y, Takeyoshi I, Koyama T, Morishita Y. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign esophageal anastomotic stricture: factors influencing its effectiveness. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:959–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siersema PD, de Wijkerslooth LR. Dilation of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1000–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hordijk ML, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Kuipers EJ. Electrocautery therapy for refractory anastomotic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan Y, Wang X, Liu D, Huo J. Endoscopic incision plus esophageal stenting for refractory esophageal stricture in children. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E111–E112. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]