Abstract

Objective

(Primary) To establish the effect of antenatal group self-hypnosis for nulliparous women on intra-partum epidural use.

Design

Multi-method randomised control trial (RCT).

Setting

Three NHS Trusts.

Population

Nulliparous women not planning elective caesarean, without medication for hypertension and without psychological illness.

Methods

Randomisation at 28–32 weeks’ gestation to usual care, or to usual care plus brief self-hypnosis training (two × 90-minute groups at around 32 and 35 weeks’ gestation; daily audio self-hypnosis CD). Follow up at 2 and 6 weeks postnatal.

Main outcome measures

Primary: epidural analgesia. Secondary: associated clinical and psychological outcomes; cost analysis.

Results

Six hundred and eighty women were randomised. There was no statistically significant difference in epidural use: 27.9% (intervention), 30.3% (control), odds ratio (OR) 0.89 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.64–1.24], or in 27 of 29 pre-specified secondary clinical and psychological outcomes. Women in the intervention group had lower actual than anticipated levels of fear and anxiety between baseline and 2 weeks post natal (anxiety: mean difference −0.72, 95% CI −1.16 to −0.28, P = 0.001); fear (mean difference −0.62, 95% CI −1.08 to −0.16, P = 0.009) [Correction added on 7 July 2015, after first online publication: ‘Mean difference’ replaced ‘Odds ratio (OR)’ in the preceding sentence.]. Postnatal response rates were 67% overall at 2 weeks. The additional cost in the intervention arm per woman was £4.83 (CI −£257.93 to £267.59).

Conclusions

Allocation to two-third-trimester group self-hypnosis training sessions did not significantly reduce intra-partum epidural analgesia use or a range of other clinical and psychological variables. The impact of women's anxiety and fear about childbirth needs further investigation.

Tweetable abstract

Going to 2 prenatal self-hypnosis groups didn't reduce labour epidural use but did reduce birth fear & anxiety postnatally at < £5 per woman.

Keywords: Cost-analysis, epidural, group antenatal training, hypnosis, labour pain, psychological outcomes, randomised trial

Introduction

Epidural analgesia is the most effective form of labour pain relief.1 It is currently used in around 30% of births in the UK, and over 60% in the USA.2,3 However, it does not necessarily result in high levels of satisfaction.4 In most settings, the majority of pregnant women would prefer to experience labour without medical intervention, including pharmacological pain relief.5,6 Nulliparous women who receive epidural analgesia are more likely to require clinical interventions, with the risk of associated morbidity and extra costs.7 The most commonly used alternative, narcotic analgesia, does not provide effective pain relief, and is associated with adverse neonatal effects.1

In response to rising demand from service users, private and public service providers are offering alternative labour pain solutions, including hypnosis programmes.8 The hypothesised mechanism of effect of hypnosis on pain perception is activation of the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with reduced perceptions of pain and unpleasantness.9 Reduced use of epidural analgesia for labour, especially for nulliparous women, could also reduce rates of interventions such as instrumental birth and neonatal antibiotic administration for pyrexia.10

Hypnosis is effective for some patients with chronic pain11,12 but the current Cochrane review of hypnosis for labour pain notes that ‘research so far conducted has not conclusively shown benefit’.13 Of the seven studies in the review, only one was undertaken in the UK. It had 65 participants and was published in 1986. As a result of rising use of hypnosis for labour pain, and following agreement with local service users and staff that this was a research priority, we undertook a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) with the primary objective of establishing the effect of a group self-hypnosis programme undertaken in the third trimester of pregnancy on rates of epidural use in labouring nulliparous women.

Methods

We originally designed the project as a feasibility study in one UK Trust, to inform the design of a future, larger RCT. In the event, with an agreed extension from the funder, we also undertook an internal pilot, then rolled out the study as a definitive trial to two more Trusts (a total of seven clinical sites). In 2013, the annual birth rates in the three participating Trusts were 10 300, 6900, and 4500. Sites included two alongside midwife-led birth centres (ABCs), two freestanding midwife-led birth centres (FSBCs) and three hospitals (Supporting Information Table S1, Characteristics of study sites).

The study was a multi-site, pragmatic, non-blinded RCT based on intention to treat and contextualised by interviews and questionnaires. Data collected in all of the phases contributed to the final analysis. Follow up continued until 6 weeks after birth. We also conducted a full economic evaluation (reported elsewhere). The focus of this paper is the primary clinical cost and psychological analyses. Information from interviews with participants will be published separately.

Participants

Participants were at 27–32 weeks’ gestation at the time of randomisation, could read and understand English, were not on medication for hypertension or psychological illness, and were not planning an elective caesarean section. Birth partners were eligible to take part if they returned a consent form.

Recruitment

Women attending antenatal clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation were informed about the study, and were asked to return a reply slip or notify the research team if they were interested in participating. If still eligible at 27 weeks’ gestation, respondents were sent further information, consent forms, and baseline questionnaires for themselves and their birth companion. Randomisation occurred when the Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) received the consent form.

Randomisation and protection against bias

We used a computer-generated sequence on a one-to-one basis, without stratification or blocking. The allocation was uploaded automatically to the participant management database, accessible by password to the research team, to allow for session allocation for the intervention group. Outcomes data were collected by staff that did not know group allocation, and returned separately to the CTU for data linkage. It was not possible to blind participants or the hypnosis trainers to group allocation. Questionnaires were sent from and returned directly to the CTU, and scanned into the outcomes database. Group allocation and outcome data were linked by confidential codes at the end of the study for analysis.

Outcome measures

Prior to transfer of the total data set from the CTU, the Trial Management Group (TMG) agreed on the primary and secondary outcomes that would be analysed and reported in the primary study report (Supporting Information Appendix S1: Clinical and psychological outcome measurements).

Primary outcome

Use of epidural analgesia for labour pain relief.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical

Hypertension after randomisation; spontaneous onset of labour; use of opioids or epidural; caesarean section; instrumental birth or caesarean section; spontaneous vaginal birth; length of labour, length of second stage; breastfeeding at 6 weeks; admission to neonatal unit (NNU); stillbirth; more than 5 days in NNU; extra postnatal care for mother and blood transfusion for mother.

Psychological

Satisfaction with labour pain relief; memory of labour pain; psychological morbidity/wellbeing; satisfaction with life, and expectation and experience of anxiety and fear.

Economic analysis

Economic analysis used the Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER), based on resource use per quality-adjusted life year (QALY), measured using the EQ-5D instrument.14 This paper provides a comparison of costs by treatment group, based on three specific phases of resource utilisation the activities undertaken during the antenatal period, an inventory of the resources required during labour, and services required as part of postpartum admissions (Supporting Information Table S2, Unit costs of antenatal activities and health services).

Questionnaires

As well as a baseline questionnaire, respondents were sent a follow-up postal questionnaire at 36 weeks’ gestation, and at 2 weeks and 6 weeks postnatal. Questionnaires were designed for the study and included a mix of validated instruments and study-specific sections. Email, text, and phone reminders were automatically triggered by the CTU systems, to a maximum of three reminders each, 2 weeks apart, for each questionnaire distributed.

Intervention

The intervention group received self-hypnosis training in addition to usual care. Two 90-minute group sessions were offered, 3 weeks apart, at around 32 and 35 weeks’ gestation (Supporting Information Appendix S2, Outline of intervention sessions, and Appendix S3).

The hypnosis scripts used in a recent Australian trial of self-hypnosis for labour pain15 were adapted, based on a methodology developed for the control of abdominal symptoms by members of the research team (P.W., V.M.)16 in thousands of patients. They were further modified by two of the study hypnosis midwives who had prior expertise and experience in hypnosis for childbirth (M.W., M.P.B.).

Participants were invited to attend group sessions at their local Trust, with or without their intended birth companion. They were also advised to listen to a 26-minute self-hypnosis CD daily (recorded by V.M.) until the birth of the baby, and to complete logs of this practice and of other antenatal educational activities.

Fifteen midwives were trained in hypnosis techniques by the same trainers (though at different times). All hypnosis midwives were visited by a member of the research team at least once during a self-hypnosis session to ensure fidelity to the intervention protocol.

Control group

Those randomised to this group continued with usual NHS antenatal care.

Usual care for both groups

Usual NHS care included antenatal clinic attendances, screening and treatment, according to NICE guidelines.17 Antenatal education is not standardised across the NHS. In most of the study locations, this included four to five classroom-type sessions, covering a range of topics, such as pregnancy concerns and new baby care and feeding advice, as well as information about available labour pain relief methods. Some areas also provided additional resources, such as aqua-natal sessions. Women from both groups also had access to a wide range of privately provided sessions, including those offered by private hypnotherapists.

Data collection and handling

The SHIP database was updated once or twice a week, with the date of birth of all study neonates born in that period. The CTU were informed by phone and email of any untoward outcomes to stop postnatal questionnaires being sent inappropriately. In the early feasibility stages of the study, a co-investigator not involved in data collection (HS) regularly reviewed a convenience sample of questionnaires for completeness and to identify any questions that respondents appeared to find problematic.

Questionnaire returns were scanned into the study database by the CTU. Intervention group logs were returned to the research team and entered onto an EXCEL file, then transferred to the CTU for data linkage.

Clinical birth outcomes, including use of epidural analgesia, were collected from electronic hospital systems and health records by the on-site research teams blind to study allocation, on scannable data collection forms, and were sent to the CTU to be scanned into the primary trial database.

For the cost analysis, resource use data was collected from the birth outcomes form, and from questionnaire returns at 36 weeks gestation and 2 and 6 weeks postnatal.

Sample size calculations

It was agreed with clinical and service user representatives and the research team that a reduction in epidural usage from 25% (the local rate at the time of the study design) to 15% would be clinically significant. With an 80% power (beta) and two-tailed alpha of 5%, 550 participants were required in the study. Over-recruitment was planned, to preserve the sensitivity of the analysis of the 6-week follow-up data while allowing for dropout. Based on a pre-study survey of women's agreement to take part in principle, it was anticipated that up to 800 women might be recruited.

Analytic strategy

Quantitative clinical and psychosocial outcomes were analysed using a two-sample t-test, with results reported as the estimated mean difference, 95% confidence interval for the mean difference, and P-value for a two-sided test of the null hypothesis that the true mean difference is zero. Binary outcomes were analysed as a two-by-two contingency table, with results reported as the estimated odds ratio, 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio and P-value for a two-sided test of the null hypothesis that the true odds ratio is one. No sub-group analyses were planned for the ITT data for the primary outcome.

The cost analysis was conducted from the perspective of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services (PSSRU).18 Costs of antenatal classes were considered potential substitutes of hypnotherapy classes. The time horizon was 28 weeks’ gestation to 6 weeks postnatal. Costs were estimated using resource use for each woman and applying unit costs obtained from the PSSRU database and the NHS Resource use database for the year 2012.19,20

Data monitoring

Data monitoring was the remit of The Trial Steering Group (TSG). Following agreement with the TSG, we did not plan or undertake an interim analysis.

Results

Feasibility and internal pilot stages

Recruitment to the feasibility phase began in August 2010 and recruitment to the full trial commenced in March 2011 once the trial registration process had been completed. Recruitment ended in April 2013 and follow up continued until July 2013 (once the final 6 week postnatal questionnaires were returned).

During the feasibility and pilot phases of the project, seven substantial amendments were submitted to ethics and governance scrutiny, and were approved. None of the amendments affected the central design of the study, so data from all phases were included in the final analysis.

Response rates and data completeness

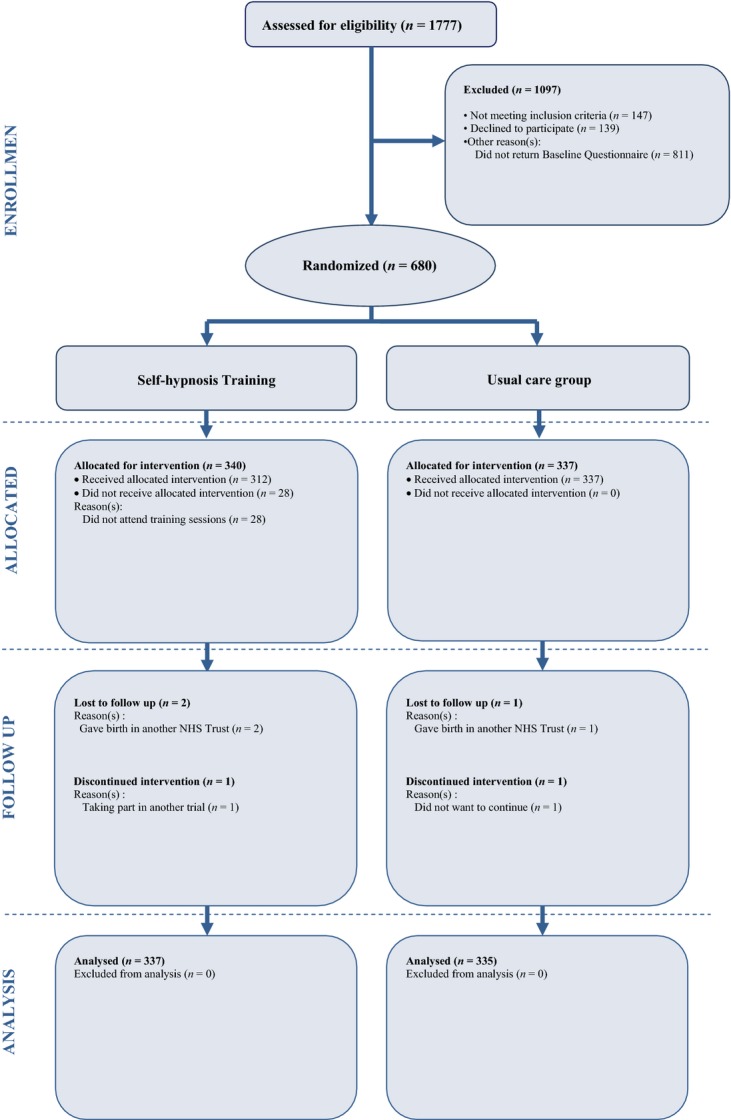

In all, 680 women were randomised, three in error. Two women asked to withdraw from the study and three were lost to follow up. Data are therefore available for 672 women (337 intervention and 335 control). Full details of the screening and randomisation process are outlined in the CONSORT flowchart in Figure1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Data on epidural use for labour pain was available for 670 women (99.7%). Response rates to the questionnaires decreased over time, from 100% at baseline to 67% at 2 weeks postnatal, and 58% at 6 weeks postnatal (Supporting Information Table S3, Questionnaire response rates) with a concomitant reduction in data completeness for variables assessed at those time-points.

Baseline characteristics were balanced between the two groups and are highlighted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Total | Intervention |

Control |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 672 | 337 | 28.4 | 5.5 | 335 | 28.5 | 5.2 |

| Gestation at randomisation | 669 | 335 | 27.8 | 1.0 | 334 | 27.8 | 1.1 |

| QOL (EQ5D)* | 667 | 334 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 333 | 5.6 | 1.0 |

| Pain expectation** | 666 | 335 | 6.5 | 0.8 | 331 | 6.4 | 0.9 |

| Views on Self-hypnosis** | 665 | 335 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 330 | 5.7 | 1.1 |

| Life Satisfaction*** | 668 | 336 | 28.0 | 4.8 | 332 | 28.1 | 5.0 |

| State Anxiety**** | 655 | 329 | 10.1 | 3.3 | 326 | 10.5 | 3.7 |

| Depression***** | 666 | 335 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 331 | 6.4 | 4.5 |

| Anxiety about labour** | 662 | 331 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 331 | 4.8 | 1.6 |

| Fear about labour** | 670 | 336 | 5.2 | 1.5 | 334 | 4.9 | 1.6 |

| N | n | n of event | % | n | n of event | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education (% GCSE or below) | 665 | 333 | 70 | 21.0 | 332 | 54 | 16.3 |

| Ethnicity (% White) | 670 | 336 | 320 | 95.2 | 334 | 303 | 90.7 |

| BMI > 40 (%) at booking | 672 | 337 | 8 | 2.4 | 335 | 9 | 2.7 |

| Income (% below 24 000) | 652 | 324 | 99 | 30.6 | 328 | 89 | 27.1 |

| Birth companion identified (% yes) | 669 | 335 | 331 | 98.8 | 334 | 334 | 100.0 |

| Type of Maternity Care (% midwife led) | 655 | 327 | 287 | 87.8 | 328 | 288 | 87.8 |

| Predicted use of Epidural (% yes) | 571 | 280 | 40 | 14.3 | 291 | 44 | 15.1 |

Fifteen point scale.

Seven point scale.

35 max score: high = better.

Max score 24: high = worse.

Max score 30: high = worse.

Protocol adherence

In all, 92% of participants randomised to the intervention attended the first session, 85.4% the second one, and 84.5% both. Group size ranged from 2 to 12.

A total of 39.4% of practice logs were returned (135/343). Based on these, the median time spent practising in total was 624 minutes (IQR 428–940 minutes). The median number of times practice took place was 24 (IQR 15–35), which approximates to three practice sessions a week. The mean amount of time per practice session was 26.35 minutes. Birth companions were reported to practise with participants for 24.5% of the sessions. It is logical to assume that women who were most likely to undertake regular practice were over-represented among those who returned their logs. Conservatively, therefore, fidelity to the protocol was likely to be lower over the whole intervention group.

Other antenatal sessions and use of hypnosis in labour

All respondents to the 2-week postnatal questionnaire reported participation in some kind of antenatal education. Of the intervention participants, 72.6% (n = 171/234) reported using self-hypnosis in labour. No-one in the usual care group attended any SHIP hypnosis training sessions, but 9.4% (n = 20/216) reported using self-hypnosis in labour.

Place of birth

There were no differences in the place of birth between the two groups. Data were available for 665 participants (334 from the intervention group and 331 from the usual care group). In all, 75.1% (n = 251) of intervention group participants and 75.5% (n = 250) of the usual care group gave birth in an obstetric-led unit in a hospital; 10.5% (n = 35) of the intervention group and 11.2% (n = 37) of the usual care group gave birth in an alongside midwifery unit; and 14.4% (n = 48) of the intervention group and 13.3% (n = 44) of women receiving usual care gave birth in a freestanding midwifery-led unit.

Findings

Primary outcome

Rates of epidural analgesia use in labour were 27.9% (n = 94) in the intervention and 30.3% (n = 101) in the control group, the odds ratio (OR) was 0.89, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.64–1.24 (see Supporting Information Table S4).

Secondary outcomes

We found no significant difference in secondary clinical outcomes relating to experience of pain in labour or clinical outcomes (Table S4).

Two of the 15 psychological measures reached statistical significance. Women in the intervention group had a greater reduction than those in the control group between the levels of anxiety and fear that they expected to feel during labour and birth (when asked at baseline) and the levels they actually reported experiencing in labour (when asked at 2 weeks postnatal). However, these findings need to be interpreted in the light of response rates for the 2-week follow-up questionnaires (67% overall), and the difference in returns between the two study arms (69% in the intervention group and 64% in the control group).

Cost analysis

The full cost-effectiveness analysis is reported elsewhere. This paper reports on cost analysis findings. This was based on antenatal activities, resources used during labour, and maternal admissions. Costs were marginally higher in the intervention group (mean extra cost £4.83 per woman, CI −£257.93 to £267.59) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted* mean costs (and 95% CI)

| Self-hypnosis Mean [95% CI] | Control Mean [95% CI] | Difference between groups Mean [95% CI]** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (£) | |||

| Antenatal activities*** | 99.23 [89.06–109.4] | 60.74 [30.88–90.61] | 38.49 [6.64 to 70.33] |

| During Labour**** | 1934.31 [1805.23–2063.39] | 1936.98 [1791.36–2082.6] | −2.67 [−191.66 to 186.32] |

| Admissions after labour***** | 474.34 [411.33–537.34] | 505.32 [414.75–595.89] | −30.99 [−138.9 to 76.93] |

| Total | 2507.88 [2339.99–2675.77] | 2503.05 [2299.88–2706.21] | 4.83 [−257.93 to 267.59] |

Presented figures are based on the complete cases to conduct economic analysis (n = 252).

Confidence interval (CI) generated using bootstrapping.

Antenatal activities included Self-Hypnosis Training, NHS Classes, Antenatal Yoga, Yoga Birth, HypnoBirthing, Active Birth, Aqua-Birth, NCT classes and Birth, Bumps & Beyond.

Cost during labour were calculated based on the mode of birth and opioid pain relief.

Admissions after labour accounted for maternal admission.

Discussion

Main findings

The data from this study do not support the primary SHIP hypothesis that allocation to two group-based self-hypnosis training sessions in the third trimester of pregnancy, along with practice CDs and (in most cases) birth companions, reduces the use of epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour. Twenty-seven of the 29 pre-specified outcomes did not demonstrate significant differences between the two groups. At 2 weeks postnatal, there was a significantly lower score for actual experiences of anxiety and fear associated with childbirth for those randomised to the intervention group versus the control group, when compared with the baseline scores given for their expectations in this area. The response rate at 2 weeks postnatal limits the generalisibility of this result. However, there was a similar finding in a recent Danish study of self-hypnosis for labour pain,21 so this outcome should be considered in any future trials of self-hypnosis for labour pain.

As far as we are aware, this cost analysis is the first to be planned in relation to self-hypnosis training in pregnancy. Results of the cost analysis suggest that the extra cost of the self-hypnosis sessions was very low for the participants in this study.

Strengths and weaknesses

The SHIP trial is the largest RCT on self-hypnosis for labour undertaken in the UK to date. Except for a study carried out in the US in 2004 where one practitioner visited three sites to provide intra-partum hypnosis, over 10 years,22 the SHIP trial is also the only trial located in more than one centre, and and the only one that has included a range of types of place of birth. It is also the only trial involving a large group of hypnosis practitioners, increasing the external generalisibility of the findings. In addition, the study included birth companions, which does not seem to be the case in other trials in this area.

However, the ability of the study to address the study objectives is limited by the fact that approximately 10% of the control group reported using self-hypnosis in labour. This illustrates both the current popularity of hypnosis-based antenatal education sessions and the general methodological difficulty of undertaking a controlled study to evaluate a technique that is popular and relatively widely available privately. The two other recent trials in this area report access to antenatal education, including hypnosis, outside of the trial protocol, but neither report rates of use of hypnosis in labour for each of the randomised groups.15,23

We took the pragmatic decision to test a form of self-hypnosis training that was delivered earlier in pregnancy than with most other trials in this area, and with fewer sessions—two versus three for most other trials. The earlier start was on the advice of the hypnosis experts involved, as, in their anecdotal experience, patients with chronically painful medical conditions benefited more the earlier hypnosis was instituted and the more it was practised. We reduced the number of face-to-face taught sessions to two as there were a large number of drop outs for the third session in the Cyna study that was completing at the same time as we were designing our protocol,15 but we strongly encouraged women to keep listening to the CD daily from the time they attended the first session until the birth of their baby. However, the SHIP trial does not answer the question as to whether longer courses of hypnosis training starting even earlier in pregnancy, might have an impact. We did not have a ‘sham’ group, as it was agreed by the team that the positive effect of being in a group is an intrinsic part of this kind of therapy. We also did not assess the degree to which attending labour ward staff were blinded to group allocation. Lower than optimal return rates of the postnatal questionnaires, and of the intervention group antenatal logs reduces the generalisability of some of the findings.

Interpretation

Our findings support those of the recent Australian and Danish studies in this area.15,21,23 Adding prenatal self-hypnosis training to usual care in a UK setting does not seem to affect the rates of epidural analgesia or of most of the intra-partum and psychosocial variables tested in this study. It is therefore unlikely that a short course of hypnosis will change rates of epidural use in high resource settings where such analgesia is widely available.

There was a significant impact on postnatal maternal assessment of childbirth anxiety and fear when compared with antenatal expectation. The generalisibility of this is limited by the low response rate at 2 weeks postnatal. However, a recent Danish study23 also noted an effect on childbirth fear, and this might be an area for examination in future.

Our cost analysis suggests that providing a short programme of self-hypnosis training in pregnancy is likely to incur relatively low costs.

Before doing further similar trials, it would be prudent to pool all the data currently available across all published trials, to establish the impact, if any, on sub-groups, so that future studies can be tailored more precisely. Studies of self-hypnosis training via different routes might also be useful. Because of the known effect of labour ward context, organisational ethos, and practitioner preference on women's decision-making about interventions in childbirth, future studies should include more in-depth qualitative work. The cost-effectiveness of different methods of providing hypnosis, including on-line apps or packages, and schemes starting earlier in pregnancy, could also be assessed. Consideration should be given to the most meaningful primary outcome measure, and to ways of maximising response rates for longitudinal data collection.

Conclusions

The SHIP trial found no statistically significant difference in the use of epidural analgesia between women receiving two NHS-funded group-based sessions of hypnosis training alongside reinforcement with a CD as well as standard care, and women receiving standard care only, in a context where both epidural analgesia and private hypnosis training for labour pain are widely available. There is no evidence of extra risk for either mother or baby, and the extra cost of providing the programme appears to be minimal. The generalisibility of the finding of reduced levels of childbirth fear and anxiety in women randomised to self-hypnosis needs to be tested in future studies with higher response rates at follow up. Such studies could include alternative means of delivering self-hypnosis training, and different programme lengths. Interviews with women and detailed economic analysis should also be considered.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the women and birth companions who participated in this trial.

The following people and institutions made significant contributions to the running of the SHIP Trial:

Trial Steering Committee—S.D., P.S., C.M., K.F., Andrew Weeks (Professor of Women's & Children's Health, University of Liverpool), Tina Lavender (Professor of Midwifery, University of Manchester), Gill Gyte (Parents’ representative, member of committee), Steven Lane (Lecturer in Biostatistics, University of Liverpool), Pierre-Martin Hirsch (Consultant Gynaecological Oncologist, Royal Preston Hospital), Catherine Gedling (Research & Development Manager, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust).

Trial Working Group—S.D., H.S., P.D., P.S., P.W., V.M., S.H., C.M., K.F., S.A., M.W., Louise Dunn (ELHT MSLC Chair) Professor David Torgerson (Director of York Trials Unit), Linda Gregson (Deputy Research & Development Manager, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust).

Collaborating Hospitals (*indicates Principal Investigator at collaborating site)

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust: C.M.*, M.W., S.H., C.G., L.G., L.D., Hasan Javed, Nicola Moss, Matthew Leluga, Megan Blease, Rachael Evans, Gillian Parker Evans, Helen Carr, Sarah Jackson, Joanne Lambert, Glenys Gallagher, Mercedes Perez-Botella, Bev Hammond, Shirley Bibby, Pam Inniss, Dawn Mullin & Geraldine Geraghty [Correction added on 7 July 2015, after first online publication: Pam Inniss, Dawn Mullin & Geraldine Geraghty have been added to the Acknowledgements.].

Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust: Katrina Rigby*, Angela Philipson, Julie Butler, Susan Burt, Janet Edwards, Deepsi Khatiwada, Gemma Whiteley, Marie Holden.

Liverpool Women's Hospital NHS Foundation Trust: Gillian Houghton*, Michelle Dower, Heather Longworth, Angela Pascall, Falak Diab, Paula Cato, Joan Ellard, Anne Hirrell, Jennifer Bright, Gillian Vernon, Louise Hardman.

York Clinical Trials Unit: David Torgerson, Andrew Foster, Val Wadsworth, Ben Cross, Maggie Gowlett, Sarah Gardner.

University of Central Lancashire: S.D., K.F., Naseerah Akooji, Laura Elizabeth Bangs-Hoskin, Fallon Dyer, Rebecca Knapp, Frank Longdon, Alexandra Scurr.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

All authors were involved equally in the development and design of the trial, the conduct of the trial, drafting of the manuscript, revision for intellectual content and approval of the final submitted version. S.D. is guarantor.

Details of ethics approval

This study was submitted to an independent ethics committee via the IRAS system (REC Ref – 10/H1011/31) and was given a favourable opinion on 7 June 2010. The trial was also approved by University ethics committee and by the Research & Development offices at all three NHS Trust sites. Each participant provided written informed consent before taking part in the study.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0808-16234). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Supporting Information

Table S1. Characteristics of study sites.

Table S2. Unit costs of antenatal activities and health services.

Table S3. Questionnaire response rates.

Table S4. Clinical and psychological outcomes.

Appendix S1. Clinical and psychological outcome measurements.

Appendix S2. Outline of intervention sessions.

Appendix S3. Detail of hypnosis scripts used for intervention group.

References

- 1.Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, Alfirevic Z, Gates S, Newburn M, et al. Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD009234. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009234.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hospital Episode Statistics: NHS Maternity Statistics 2012–13. [ http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB12744]. Accessed 27 May 2014.

- 3.Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Listening to Mothers SM III: Pregnancy and Birth. New York: Childbirth Connection; 2013. [ http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/LTM-III_Pregnancy-and-Birth.pdf]. Accessed 17 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Howell C. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD000331. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub2. 1469-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scotland GS, McNamee P, Cheyne H, Hundley V, Barnett C. Preferences for aspects of labor management: results from a discrete choice experiment. Birth. 2011;38:36–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lally JE, Murtagh MJ, Macphail S, Thomson R. More in hope than expectation: a systematic review of women's expectations and experience of pain relief in labour. BMC Med. 2008;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossignol M, Chaillet N, Boughrassa F, Moutquin J. Interrelations between four antepartum obstetric interventions and cesarean delivery in women at low risk: a systematic review and modeling of the cascade of interventions. Birth. 2014;41:70–8. doi: 10.1111/birt.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Choices. Hypnotherapy. [ http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/hypnotherapy/Pages/Introduction.aspx]. Accessed 16 July 2014.

- 9.Faymonville ME, Laureys S, Degueldre C, DelFiore G, Luxen A, Franck G, et al. Neural mechanisms of antinociceptive effects of hypnosis. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1257–67. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman E, O'Donoghue C. Unintended effects of epidural analgesia during labor: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;185(5 Suppl Nature):S31–68. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonsalkorale WM, Toner BB, Whorwell PJ. Cognitive change in patients undergoing hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:271–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkins G, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Hypnotherapy for the management of chronic pain. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2007;55:275–87. doi: 10.1080/00207140701338621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madden K, Middleton P, Cyna AM, Matthewson M, Jones L. Hypnosis for pain management during labour and childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD009356. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009356.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kind P. The EuroQoL instrument: an index of health-related quality of life. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Rivera; 1996. pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cyna AM, Crowther CA, Robinson JS, Andrew M, Antoniou G, Baghurst P. Hypnosis antenatal training for childbirth: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2013;120:1248–59. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller V, Whorwell PJ. Hypnotherapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders: a review. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2009;57:279–92. doi: 10.1080/00207140902881098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) NICE Guideline number 62 2012. Routine antenatal care for healthy pregnant women. [ http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG062PublicInfo.pdf]. Accessed 27 May 2014.

- 18.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2008. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent. [ http://www.pssru.ac.uk]. Accessed 27 May 2014.

- 19.Department of Health. National schedule of reference costs 2007-08 for NHS Trusts and PCTs. [ http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_098945]. Accessed 27 May 2014.

- 20.British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary September 2008. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner A, Uldbjerg N, Zachariae R, Sen CW, Nohr EA. Antenatal hypnosis training and childbirth experience: a randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2013;40:272–80. doi: 10.1111/birt.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehl-Madrona LE. Hypnosis to Facilitate Uncomplicated Birth. Am J Clin Hypn. 2004;46:299–312. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2004.10403614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner A, Uldbjerg N, Zachariae R, Rosen G, Nohr EA. Self-hypnosis for coping with labour pain: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2013;120:346–53. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Characteristics of study sites.

Table S2. Unit costs of antenatal activities and health services.

Table S3. Questionnaire response rates.

Table S4. Clinical and psychological outcomes.

Appendix S1. Clinical and psychological outcome measurements.

Appendix S2. Outline of intervention sessions.

Appendix S3. Detail of hypnosis scripts used for intervention group.