SUMMARY

In Escherichia coli, acquisition of new spacers in the course of CRISPR-Cas adaptation is dramatically stimulated by preexisting partial matches between bacterial CRISPR cassette spacer and a protospacer sequence in DNA of infecting bacteriophage or plasmid transformed. This phenomenon, which we refer to as “priming”, can be used for very simple and rapid construction of multiple E. coli strains capable of targeting, through CRISPR interference, any phage or plasmid of interest. Availability of such strains should allow rapid progress in the analysis of CRISPR-Cas system function against diverse mobile genetic elements.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, CRISPR, Cas proteins, bacteriophage, spacers, strain construction

INTRODUCTION

In Escherichia coli, the CRISPR-Cas system is dormant at least at laboratory conditions (1–3). However, elevated expression of cas genes is sufficient to make cells resistant to transformation with plasmids or infection with some phages, provided that the CRISPR cassette contains a spacer that matches a protospacer in plasmid being transformed or phage used to infect (2, 4). Increased cas gene expression can be achieved by a deletion of a gene coding for global transcription repressor H-NS, which negatively controls cas gene transcription (1–3). Another strategy is to co-overexpress cas genes from a plasmid. Compatible plasmids expressing the cas3 gene, and the casABCDE12 genes have been described (4). We developed a series of E. coli K12-based strains with chromosomal cas genes fused to inducible promoters (Ref. 5, and Fig. 1). These strains appear to be preferable to plasmid-borne cas co-overexpression since there is no gross overproduction of Cas proteins in induced cells. On the other hand, the level of expression is sufficiently high to lead to a much more prominent CRISPR interference/adaptation response than that observed in the hns mutant. The later strain also does not allow one to control cas gene expression level and has various pleiotropic effects due to derepression of multiple genes that are normally repressed by H-NS.

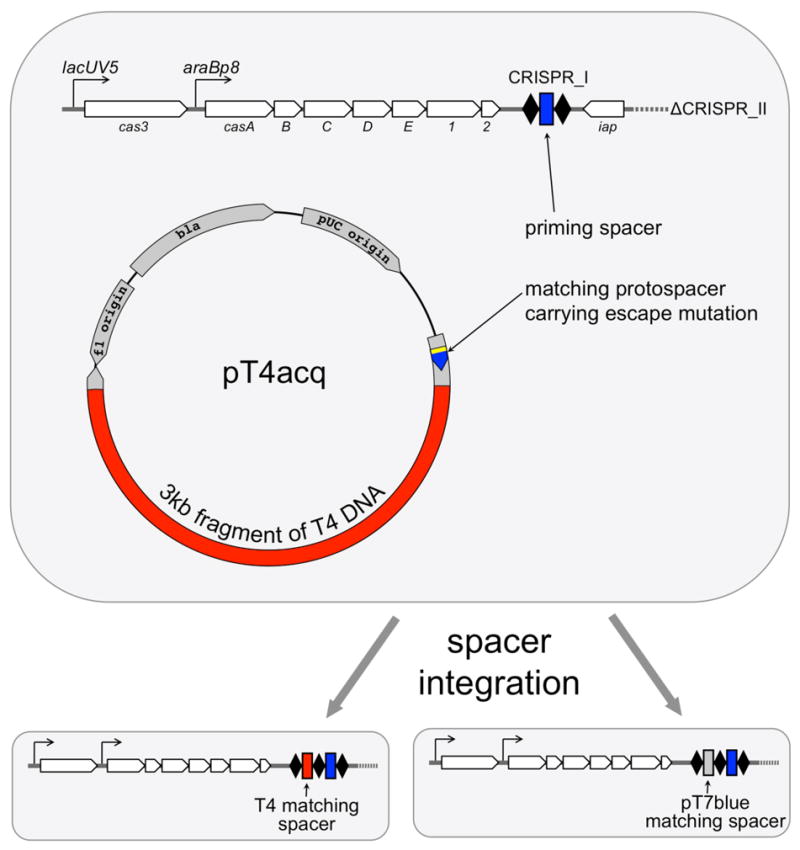

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of E. coli strain KD263 transformed with T4 capture plasmid pT4acq. The strain contains cas genes driven by the lacUV5 (cas3) and araBP8 (casABCDE12) promoters. The CRISPR II cassette has been deleted, while the CRISPR I cassette has been reduced and contains two repeats separated by a g8 spacer (blue) derived from the M13 phage (6). pT4acq is based on the pT7-blue vector and contains a fragment corresponding to G8 protospacer with escape substitution (6, blue) and a ~3 kbp insert of bacteriophage T4 genomic DNA. Primed spacer acquisition leads to expanded CRISPR I cassette carrying phage insert of plasmid vector derived spacer (below).

To study CRISPR interference response directed to a specific mobile genetic element one needs, in addition to sufficient levels of cas gene expression, a CRISPR cassette with a spacer targeting a protospacer in foreign DNA. In practice, one has to test multiple different spacers to observe strong interference, for the magnitude of CRISPR interference appears to vary from one spacer to another for reasons, which are not yet understood, but may involve not just the strength of crRNA-Cascade interaction with target DNA but also the location of the protospacer in the phage or plasmid genome. Up to recently, specific “targeting” E. coli strains had to be created by genetic engineering of genomic CRISPR cassettes using a modified version of the recombineering technique (5). For various reasons (mostly having to do with the presence of multiple identical repeats in the cassette) the procedure for engineering expanded CRISPR cassettes has been technically challenging, time-consuming, and did not lend itself to multiplexing.

While studying the CRISPR adaptation process in E. coli we discovered a curios phenomenon that we refer to as “priming”. We observed that if foreign DNA contained a mutated protospacer that rendered CRISPR interference inactive (due to a single-nucleotide substitution in the PAM or the seed sequence, Ref. 6), very efficient acquisition of additional spacers derived from DNA located in cis with respect to such protospacer is observed (5). The molecular mechanism of the priming phenomenon is not understood yet, however, it is clear that it must be biologically significant, for it provides molecular “memory” of prior encounters with foreign DNA that allows specific adaptive response to targets that managed to escape initial interference. The priming phenomenon is very useful for facile construction of new strains targeting various regions of phage and/or plasmid DNA. Such strains can be used to study the molecular details of CRISPR-Cas function directed against various mobile genetic elements. A general procedure to use priming-mediated construction of targeting E. coli strains is described below.

Procedure outline

Priming-mediated strain construction involves creation of a plasmid containing a escape protospacer targeted by a resident CRISPR spacer and a fragment of DNA that needs to be targeted. Following transformation and induction of CRISPR adaptation, clones that have lost the plasmid and expanded their CRISPR cassettes are selected. Upon sequencing, clones that acquired spacers from DNA of interest are identified and used for downstream applications.

Strains and plasmids

The KD263 E. coli strain contains the cas3 gene under the control of lacUV5 promoter and the casABCDE12 operon under the control of araBp8 promoter (Fig. 1). The strain has been additionally modified to remove the CRISPR II cassette and the CRISPR I cassette has been reduced to a minimum, with just a single repeat-spacer-repeat unit. The spacer, referred to as g8, is derived from bacteriophage M13 and is described in reference 6. Similar strains containing both E. coli K12 CRISPR cassettes with CRISPR I expanded (or not) by a single repeat-spacer unit containing the g8 spacer are also available (BW40119 and BW40114, respectively, Ref. 5). The strains are available from the authors upon request.

The starting plasmid is a pT7blue vector (EMD Millipore, USA) with a DNA fragment corresponding to one of the resident CRISPR spacers cloned into the EcoRV site. The plasmid-borne protospacer should either carry a single-nucleotide substitution in the PAM or in the seed (as in the example below) to render CRISPR-Cas interference inactive. When using strains other than KD263 or BW40119, for example, BW40114, which contains inducible cas genes and natural CRISPR I and CRISPR II cassettes (5), hns mutants (6), or cells expressing cas genes and pre-crRNA from plasmids (4), plasmids harboring a priming protospacer matching one of the spacers in genomic CRISPR cassette have to be created. A protocol presented below used for construction of pT7blue plasmid with a g8 protospacer insert works well.

Step 1. Creating a plasmid harboring a priming protospacer

A plasmid carrying a mutant protospacer is constructed by cloning a synthetic oligonucleotide duplex in the pT7blue vector. In the example provided below, two complementary oligonucleotides whose sequences correspond to the g8 spacer (6) with a substitution at the seed sequence (C1T, highlighted in bold typeface) and functional ATG PAM sequence (underlined) are used. In this particular example oligo sequences are:

pg8_F: 5′-ATGTTGTCTTTCGCTGCTGAGGGTGACGATCCCGC-3′ and

pg8_R: 5′-GCGGGATCGTCACCCTCAGCAGCGAAAGACAACAT-3′

Protocol 1: Preparation of synthetic priming protospacer duplex and its ligation into a plasmid

Combine equimolar amounts of each oligonucleotide (100 pmol) in 10 μl of buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, incubate for 3 min at 95 °C in a heatblock or water bath and then transfer to room temperature and leave for an hour to anneal.

-

Dilute annealed oligos with nuclease-free water 100-fold and mix 1 μl of the duplex (0.1 pmol) with 4 μl of water and 5 μl of End Conversion Mix (Perfectly Blunt® Cloning Kit from the EMD Millipore). Incubate the mixture at 22 °C for 15 min. Incubate reactions at 75 °C for 5 min and briefly cool on ice for 2 min. Alternatively, the duplex can be phosphorylated using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK from New England BioLabs® Inc.) In this case, perform the reaction in 10 μl of 1xligase buffer (New England BioLabs® Inc.),, at 37 °C for 30 min, inactivate the enzyme by heating at 65 °C for 20 min.

Note: The kinase must be inactivated before the ligation to avoid high vector background due to vector phosphorylation and subsequent self-ligation. The procedure described above is only needed if non-phosphorylated oligos were purchased from the vendor and is not necessary 5-end phosphorylated oligos were used to create the duplex.

For ligation, add 1 μl of the pT7blue blunt-end vector from Perfectly Blunt® Cloning Kit and 1 μl of T4 DNA ligase directly to 10 μl of phosphorylated duplex obtained in the previous step. Incubate at 22 °C for 30 min. An insert:vector molar ratio under these conditions is 3:1 and gives a good yield of recombinant plasmids containing single-copy inserts. The blunt-end vector can also be prepared in house from intact pT7blue plasmid using appropriate standard procedures (digestion with EcoRV and dephosphorylation).

Transform the ligation mixture into competent E. coli. Ready-to-use competent E. coli cells can be obtained from various suppliers (we use NovaBlue Singles™ from EMD Millipore) Competent E. coli cells can also be prepared in house.

Protocol 2: Preparation of chemically-competent E. coli cells

Streak an appropriate E. coli strain (such as DH5α or similar) on an LB agar plate. Grow the plate overnight at 37 °C.

Inoculate a single colony from the plate into 3 ml of liquid LB medium. Grow at 37 °C with agitation overnight.

Add 1 ml of overnight culture to 100 ml liquid LB and incubate at 37 °C with agitation until OD600 reaches 0.5. Chill the culture on ice for 10 min. It is important to keep the cells at 4 °C for the rest of the procedure. Collect the cells by centrifuging at 3,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Pour off the supernatant and gently resuspend the cell pellet in 50 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M CaCl2 solution. Keep cells on ice for 30 min.

Centrifuge at 3,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C and resuspend the cell pellet in 10 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M CaCl2. Incubate on ice for 30 min.

Repeat the centrifugation step and resuspend cells in 0.5 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M CaCl2. Incubate on ice for 60 min.

Distribute 50 μl aliquots into sterile pre-chilled 1.5 ml tubes, and flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Store at −80 °C.

Protocol 3: Transformation of competent E. coli

When using commercial competent cells, follow the protocol provided by the supplier. When using in-house cells:

Add 1–2 μl of ligation reaction (above) or solution containing ~1 ng of pure plasmid to a 50 μl aliquot of thawed ice-cold competent cells

Incubate the mixture on ice for 5 min, heat-shock at 42 °C for 30 sec, and return immediately on ice for 2 min.

Add 250 μl of pre-warmed (37 °C) liquid LB and incubate for 30–60 min at 37 °C with agitation.

Plate 10 and 100 μl on two separate LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml carbenicillin or ampicillin, 80 μM mM IPTG and 70 μg/ml X-gal. Incubate the plates overnight at 37 °C.

Pick up several white colonies that are likely to contain an insert using a sterile toothpick, inoculate 3 ml of liquid LB containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin, grow overnight and prepare plasmid DNA.

Confirm the presence of insert by sequencing.

A plasmid created in this way using the G8 protospacer oligos has been named pT7blue_G8. The orientation of the protospacer (defined by the location of the ATG PAM) matches the direction of the lacZ α peptide transcription (Fig. 1). However, plasmids containing either orientation of the protospacer insert can be used.

Note: It is not necessary to incubate competent cells for the outgrowth period after heat shock for ampicillin-resistant plasmids, however this step may increase cloning efficiency.

Note: Carbenicillin is preferred as a selection agent for clones containing ampicillin-resistant plasmids as it is more stable than ampicillin and so less secondary-growth “satellite” colonies that do not contain a plasmid are formed.

Note: There is no need to add IPTG and X-gal when transforming making a spacer capture plasmid or transforming KD263 competent cells with an already prepared spacer capture plasmid, below.

Step 2. Creating a capture plasmid harboring an escape protospacer and a fragment of phage DNA

Once a plasmid containing a priming protospacer is created, it is used to construct a plasmid containing a fragment of DNA from a phage or another plasmid one is interested in. A fragment of phage DNA is amplified using appropriate primers and cloned into the priming protospacer plasmid using standard procedures. The procedure presented below was used to create a pT4acq plasmid containing a fragment of bacteriophage T4 DNA.

Protocol 4: Preparation of phage genomic DNA

While in most cases PCR amplification directly from cell lysates obtained after phage infection can by successfully used, we find that longer fragments of phage DNA (5 kbp or more) are best amplified from purified phage genomic DNA. A method described in Lee and Rasheed (7) developed for plasmid purification works well for most phage lysates.

Take 450 μl of phage lysate (a titer of 109 plaque forming units/ml or higher), add 50 μl of 0.5.M EDTA, and 400 μl buffer-saturated phenol. Vortex for 10 seconds at highest Vortex settings. Ware gloves as phenol may leak.

Centrifuge on a microfuge at highest speed for 10 minutes at room temperature and transfer the upper aqueous phage into a fresh Eppendrof tube.

Add 400 μl of phenol-chloroform (50:50) solution and vortex/centrifuge as above.

Transfer the aqueous phase to a fresh Eppendorf tube and extract with 400 μl choloroform as above.

Add 1 ml of ice-cold 95% ethanol and precipitate phage DNA by incubating at −20°C for 15 minutes.

Centrifuge on a microfuge at highest speed for 10 minutes at room temperature, discard the supernatant.

Wash the precipitate, which contains phage DNA with ice-cold 70% ethanol.

Air dry the pellet and dissolve in 100 μl of distilled water.

Protocol 6: Amplification of phage DNA fragment for cloning

-

Design a primer pair to amplify a 1 –5 kbp fragment of phage DNA. In the example given here primers T4B_7–F (TTTTTGGATCCGCGACTTTACCAGCGAATG), and T4S_7–R (TTTTTGAGCTCGGTAATGCAGCTTCAGGAAAA) were used to amplify a 2.3 kpb fragment of bacteriophage T4 DNA between genomic positions 83,951 and 86,9411. The amplified fragment contains the entire T4 gene 7 and part of gene 8 (both genes encode T4 virion proteins). T4B_7–F and T4S_7–R primers contain, correspondingly, engineered BamHI and SacI recognition sites (underlined). The amplified T4 fragment does not contain the recognition sites for these restriction endonucleases. When designing your primer pairs, different restriction endonuclease sites can be introduced into oligonucleotide primers, however the amplified phage DNA fragment shall not contain the recognition sites for these enzymes. After PCR amplification, the amplified phage DNA fragment was purified from an agarose gel, treated with BamHI and SacI and then re-purified from an agarose gel after electrophoresis. The T4 fragment was cloned between the BamHI and SacI sites located in the polylinker of the pT7blue_G8 plasmid that has been digested with BamHI and SacI. The resulting plasmid was named pT4acq. It allows one to capture T4-insert derived spacers as described below.

Note: Some phage-encoded proteins are highly toxic. When creating a spacer capture plasmid try to avoid phage DNA fragments containing intact phage genes known to encode toxic proteins.

Step 3. Primed adaptation

Generally, the chance of obtaining an E. coli strain with a CRISPR spacer derived by primed adaption from phage DNA segment of a spacer capture plasmid increases together with the increase of the size of phage insert. We routinely use fragments of 1–5 kbp. Since the size of pT7blue is 2,881 bp, screening of strains that acquired spacers from phage becomes very easy. The procedure presented below is based on an example with the pT4acq plasmid and the KD263 cells.

Protocol 7: The adaptation experiment

Transform competent KD263 cells with spacer capture plasmid pT4acq and select transformants on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml carbenicillin or ampicillin.

Pick up an individual colony and grow overnight in 5 ml of liquid LB in the presence of ampicillin at 37 °C.

Transfer 0.1 ml of overnight culture into a 5 ml of liquid LB and after 1 hour of growth in incubator shaker at 37 °C induce the culture by the addition of 1 mM arabinose and 1 mM IPTG. Allow the culture to grow for 8 hours or overnight.

Plate aliquots of serial dilutions of induced culture on LB agar plates to obtain individual colonies.

Select a dozen individual colonies and using toothpicks and plate each on LB agar plates with and without ampicillin. Be sure to properly label the plates such that matching clones on both plates can be identified.

After overnight growth at 37 °C, identify clones that have lost ampicillin resistance (usually, less than 10% of colonies remain ampicillin-resistant, and, therefore, harbor the plasmid after growth in the presence of inducers).

Protocol 8: Screening for CRISPR cassette expansion

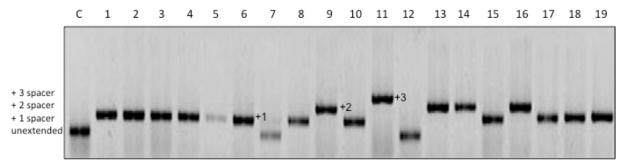

Use colony PCR to screen ampicillin-sensitive colonies for CRISPR cassette expansion with Ec-LDR-F (5′-AAGGTTGGTGGGTTGTTTTTATGG - 3′) and M13g8 (5′ – GGATCGTCACCCTCAGCAGCG – 3′) primers. The latter primer anneals to the g8 spacer. A different primer has to be designed when looking for expansion of CRISPR cassettes using capture plasmids harboring priming protospacers corresponding to different CRISPR cassette spacers. Primer Ec-LDR-F anneals to the leader sequence of E. coli CRISPR I cassette. A different primer is needed when looking for expansion of CRISPR II cassette (recall that this cassette is absent in KD263). A very good protocol for colony PCR can be found in the PET system manual (http://lifeserv.bgu.ac.il/wb/zarivach/media/protocols/Novagen%20pET%20system%20manual.pdf). Results of a typical experiment obtained with cells that have lost pT4acq are shown in Fig. 2.

-

Identify clones containing CRISPR cassettes expanded by a single repeat-spacer unit (Fig. 2) and subject several amplified expanded cassette DNA fragments to sequencing to identify phage-derived spacers. A typical result is presented in Table 1.

Note: While the procedure described above is very efficient, not all phage-derived spacers may lead to efficient interference. To increase the proportion of cells harboring interference-capable spacers, one can infect cells after growth in the presence of inducers with a phage one is working with at a high multiplicity of infection, collect surviving cells, restreak for single colonies on an LB agar plate and identify clones with expanded cassettes as described above.

Figure 2. Screening for CRISPR cassette expansion.

An agarose gel showing the results of analysis of 18 clones obtained from an induced culture of pT4acq-containing KD263 E. coli that lost ampicillin-resistance is shown. Lane labeled “C” is a control lane (amplification of CRISPR cassette from KD263 E. coli that has not been transformed with any plasmid). Clones that undergone cassette expansion by 1, 2, or 3 repeat-spacer units are indicated.

Table 1.

Sequence analysis of spacers acquired during primed acquisition experiment with the pT4acq plasmid.

| P | Protospacer sequence | PAM sequence | Phage/Plasmid | Strand | Protospacer position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CCATACCAAACGACGAGCGTGACACCACGATG | AAG | pT7blue vector | nP | 1378 |

| 2 | TATATATGAGTAAACTTGGTCTGACAGTTACC | AAG | pT7blue vector | P | 1759 |

| 3 | TTGGCCGCAGTGTTATCACTCATGGTTATGGC | AAG | pT7blue vector | P | 1272 |

| 4 | TCATTCTGAGAATAGTGTATGCGGCGACCGAG | AAG | pT7blue vector | P | 1167 |

| 5 | TGCTCATCATTGGAAAACGTTCTTCGGGGCGA | AAG | pT7blue vector | P | 1076 |

| 6 | AAAGAAGACGTATTCAACCCGGATATGCGAAT | AAG | T4 | nP | 84327 |

| 8 | ACCCGACTAGATGGGGATATGAAGATAATCTC | AAG | T4 | nP | 86806 |

| 10 | GAACCACGATATATTCATTCGTGCATCTATTT | AAG | T4 | P | 86781 |

| 15 | ATGCTATTGAACACATTCCGGTATCAGGAACA | AAG | T4 | P | 86586 |

| 17 | GGAGCTGAGTTACACACTACAATATCGTTAAT | TAA | T4 | P | 86503 |

| 18 | CAAATCCTTTCCTTTAACCCCACGAATAATTT | AAG | T4 | P | 85600 |

| 19 | ATAACACTTGAATCATTCATCTATTTTAACCT | TAG | T4 | P | 86170 |

The table presents the results of analysis of 12 clones containing CRISPR cassettes expanded by a single repeat-spacer unit (Fig. 2). For each spacer it sequence, the PAM of the corresponding protospacer, the source of the spacer (plasmid or T4 insert part of the pT4acq plasmid) the strand (“P” being primed strand, “nP” – non-primed strand) and the location of the PAM proximal protospacer base (in pT7 blue vector or T4 phage genome) is shown.

Protocol 9: Phage sensitivity test

The sensitivity of cells that acquired distinct phage-derived spacers to phage infection is easily determined by a spot test method.

Grow selected clones that acquired phage-derived spacers in LB supplemented with 1 mM arabinose and 1 mM IPTG at 37 °C until OD600 reaches 0.5–0.7.

Overlay the LB agar plate containing 1 mM arabinose and 1 mM IPTG with 1 ml of melted soft (.75%) agar containing 50 ml of cell culture. The soft agar temperature should be no higher than 45 °C when the cells are added!

After solidification for 5 min, deposit 5 ml drops of 10-fold serial dilutions of phage lysate on the soft agar surface.

The serial dilutions of phage lysate are created in sterile Eppendorf tubes clearly marked (“10−2”, “10−4” etc.) by adding 10 μl of stock phage lysate of known titer to 990 μl of liquid LB, mixing, then withdrawing 100 μl and placing that into 990 μl of liquid LB and so on up to a 10−8/10−10 dilution (5 μl of the last dilution should contain an estimated 10–100 plaque forming units).

Allow the drops containing phage stock dilutions to dry and incubate at 37 °C overnight.

-

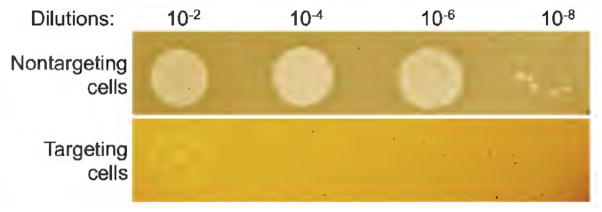

Determine efficiency of plaquing (e.o.p.) as a ratio of most dilute phage titers where individual phage plaques are observed on lawns of cells expressing phage targeting crRNA and non-targeting control cell lawns. An e.o.p. of 1 indicates that there is no interference. An e.o.p. around 10−4 – 10−5 can be attained with some crRNAs/phage pairs. Intermdeiate e.o.p. values (ca. 10−2 are also often observed). Results of a representative phage sensitivity spot test experiment is shown in Fig. 3.

Note: Induced cell cultures can be prepared in advance stored at 4 °C for up for a week and used for phage susceptibility tests.

Figure 3. Phage susceptibility test.

A results of phage-titering on two plates seeded with lawns of KD263 cells expressing a phage-targeting crRNA from a spacer acquired during the adaptation experiment (bottom) or a control, non-targeting crRNA (top) are shown. The dilutions of phage stock are indicated above.

Conclusions

We have successfully used the procedure described above to obtain numerous E. coli strains containing CRISPR spacers targeting multiple bacteriophages and plasmids. The availability of such strains opens up new interesting areas of research, for example, allowing one to determine the requirements for efficient CRISRP/Cas interference besides a spacer-protospacer match and the presence of a functional PAM motif. The procedure can be made even more powerful by using libraries of spacer capture plasmids containing the entire genome of a phage or an episome being studied. Various more specialized application, such as creating E. coli strains capable of targeting of specific regions of their own DNA and thus leading to defined genomic lesions are also possible.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM10407, Molecular and Cell Biology Program grant from the Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium, and Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation project 14.B25.31.0004.

References

- 1.Pul U, Wurm R, Arslan Z, Geissen R, Hofmann N, Wagner R. Identification and characterization of E. coli CRISPR-cas promoters and their silencing by H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1495–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pougach K, Semenova E, Bogdanova E, Datsenko KA, Djordjevic M, Wanner BL, Severinov K. Transcription, processing and function of CRISPR cassettes in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:1367–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westra ER, Pul U, Heidrich N, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Stratmann T, Wurm R, Raine A, Mescher M, Van Heereveld L, Mastop M, Wagner EG, Schnetz K, Van Der Oost J, Wagner R, Brouns SJ. H-NS-mediated repression of CRISPR-based immunity in Escherichia coli K12 can be relieved by the transcription activator LeuO. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:1380–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJ, Snijders AP, Dickman MJ, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, van der Oost J. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datsenko KA, Pougach K, Tikhonov A, Wanner BL, Severinov K, Semenova E. Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system. Nat Commun. 2012;3:945. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semenova E, Jore MM, Datsenko KA, Semenova A, Westra ER, Wanner B, van der Oost J, Brouns SJ, Severinov K. Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10098–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SY, Rasheed S. A simple procedure for maximum yield of high-quality plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 1990;9:676–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]