Abstract

Recently, the two-repeat human telomeric d(TAGGGTTAGGGT) sequence has been shown to form interconverting parallel and antiparallel G-quadruplex structures in solution. Here, we examine the structures formed by the two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) sequence, which differs from the human sequence only by one G-for-A replacement in each repeat. We show by NMR that this sequence forms two novel G-quadruplex structures in Na+-containing solution. Both structures are asymmetric, dimeric G-quadruplexes involving a core of four stacked G-tetrads and two edgewise loops. The adjacent strands of the G-tetrad core are alternately parallel and antiparallel. All G-tetrads adopt syn·syn·anti·anti alignments, which occur with 5′-syn-anti-syn-anti-3′ alternations along G-tracks. In the first structure (head-to-head), two loops are at one end of the G-tetrad core; in the second structure (head-to-tail), two loops are located on opposite ends of the G-tetrad core. In contrast to the human telomere counterpart, the proportions of the two forms here are similar for a wide range of temperatures; their unfolding rates are also similar, with an activation enthalpy of 153 kJ/mol.

Keywords: G-quadruplex polymorphism, G-quadruplex unfolding kinetics, interconversion between quadruplex topologies, telomeric DNA

Introduction

Guanine-rich sequences are found in a number of important DNA regions, such as promoter regions of many oncogenes, centromere and telomeres. In particular, telomeres contain highly repeated G-rich sequences which consist of (TTAGGG)n in human, (TTGGGG)n in Tetrahymena and (TTTTGGGG)n in Oxytricha. G-rich oligonucleotides can form four-stranded G-quadruplex structures involving planar G-tetrads. Currently, the G-quadruplex structures from the telomeric G-rich strand are a potential target for development of anticancer drugs.1–3

G-quadruplexes are highly polymorphic with respect to three mutually related factors: the orientation of the strands; the syn/anti glycosidic conformations of guanine bases; and the loop connectivities. The preferred structures depend on the nature of monovalent cations, such as potassium or sodium. Oligonucleotides containing one, two, or four G-stretches can form tetrameric, dimeric, or monomeric G-quadruplexes, respectively.4,5 In tetrameric G-quadruplexes studied so far, strands were parallel and guanine bases were anti,4 indicating that this structure is preferred in the absence of looping constraints. In dimeric and monomeric G-quadruplexes, loops connect G-stretches. The loops can be classified into three major families: edgewise loops connecting two adjacent antiparallel strands; diagonal loops connecting two opposing antiparallel strands; and double-chain-reversal loops connecting adjacent parallel strands.4 These various looping motifs, which combine with different strand orientations and syn/anti distributions, have been found in many different monomeric (intramolecular) G-quadruplexes.6–11 However, most of the dimeric (bimolecular) G-quadruplexes characterized so far display loops in the diagonal-loop family, together with syn·syn·anti·anti alignment around the G-tetrads.12–18

Recently, Parkinson et al. reported that, in a K+-containing crystal, the two-repeat human telomeric d(TAGGGTTAGGGT) sequence formed a novel dimeric G-quadruplex structure with all parallel strands, anti guanine bases and double-chain-reversal loops.7 On the other hand, in K+-containing solution, the same sequence forms both parallel and antiparallel G-quadruplex structures,19 which coexist in solution and have different kinetics of folding and unfolding. In this study, we examine the structures formed by the two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGG GGT) sequence, which differs from the human sequence only by one G-for-A replacement in each repeat. We show that in Na+-containing solution this sequence forms two novel dimeric G-quadruplex structures, which are both asymmetric and completely different from the topologies of the human sequence. The thermodynamic properties and unfolding kinetics of these two structures are similar for a wide range of temperatures, in contrast to the two G-quadruplex forms of the human telomere counterpart.19

Nomenclature

The G-tetrad is a cyclic, hydrogen-bonded square planar alignment of four guanine bases (Figure 5(b)). A G-quadruplex is a four-stranded structure built from the stacking of multiple G-tetrads. Four strands can be independent or connected by linkers (loops).

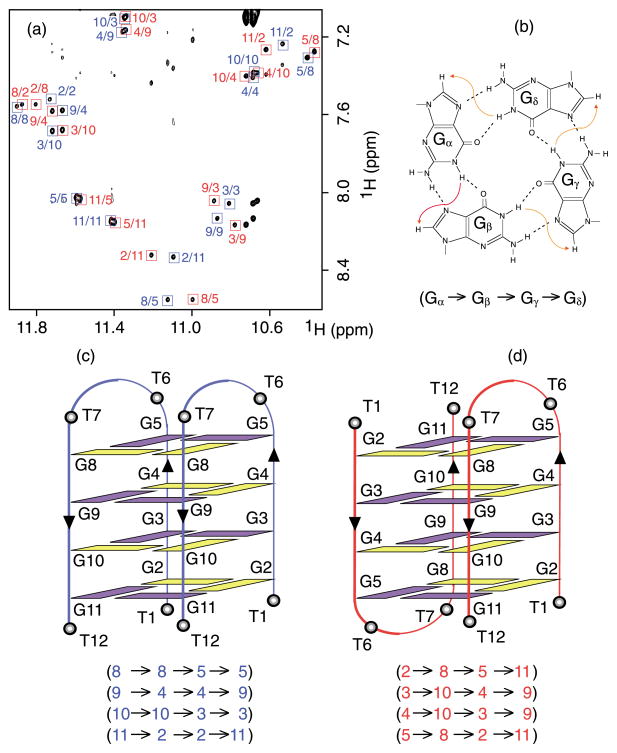

Figure 5.

(a) NOESY spectrum (mixing time, 400 ms) (same conditions as for Figure 3(b)). The imino–H8 cross-peaks are framed and labeled with the number of imino protons in the first position and that of H8 in the second position. (b) Specific imino–H8 connectivity pattern around a G-tetrad (Gα·Gβ·Gγ·Gδ) indicated with arrows (connectivity between Gδ and Gα implied). (c) and (d) Schematic structures that satisfy NOE connectivities shown in parentheses. Violet and yellow represent anti and syn guanine bases, respectively. Note that two strands of each form are colored identically (blue or red) regardless of their difference in structure.

Results

d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) forms different G-quadruplex structures in solution

One-dimensional proton spectra of the two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) sequence in 100 mM Na+ are plotted in Figure 1. Sharp resonances at 10–12 ppm are characteristic of G-quadruplex structures.6,12 Several imino protons persist when dissolving the sample in 2H2O (Figure 1(b)), since guanine imino protons within G-tetrads are protected from exchange with solvent.12 There are 32 guanine imino protons (see below), corresponding to four different strand structures (eight guanine bases per strand). However, at this point we do not know the number of different G-quadruplex structures; this depends on the number of different strands in each structure.

Figure 1.

One-dimensional proton spectra of d(TGGG GTTGGGGT) at 600 MHz: (a) in 95% H2O, 5% 2H2O; (b) after 15 minutes in 99.99% 2H2O, showing slowly exchanging imino protons from internal G-tetrads (except for peaks labeled with stars from an external G-tetrad). Experimental conditions: 25 °C; 100 mM NaCl; pH 7; strand concentration 1.3 mM.

Determination of stoichiometry

NMR determination of stoichiometry was based on the titration of the concentration-dependent equilibrium between different structural forms.20 Figure 2(a) shows spectra of guanine imino protons for two different strand concentrations. These protons are characteristic of (different) G-quadruplexes. At a wide range of concentrations, the relative intensities of different peaks remained unchanged, indicating that (different) G-quadruplex structures were of the same stoichiometry.

Figure 2.

Determination of stoichiometry by NMR titration. (a) Imino proton spectra at 50 °C equilibrium. The relative intensities of peaks from different structured forms are independent of DNA concentration, indicating that they are of the same stoichiometry. (b) Part of the aromatic spectral region, showing the peaks of the structured forms (grey) and the peaks of the unstructured single strand (black), whose relative intensities are dependent on DNA concentration. (c) NMR titration of the equilibrium strand concentrations of the multimer structures and of the unstructured monomer. A line of slope 2 is drawn through the data points. Experimental conditions: 50 °C; 80 mM NaCl; 20 mM sodium phosphate; pH 7.

On the other hand, spectra in Figure 2(b) show that the relative intensities of peaks corresponding to the structured (G-quadruplex) forms and the unfolded form are dependent on DNA concentration. The unfolded form (monomer) was identified as the species, which is predominant at low concentration and/or high temperature, showing sharp non-exchangeable protons but no imino proton signals. The slope of 2 (Figure 2(c)) from the NMR titration of the concentration-dependent equilibrium between G-quadruplexes and unfolded monomer indicated that the G-quadruplex structures were dimers.

Resonance assignments

Guanine imino protons were assigned unambiguously to their positions in the sequence by the site-specific, low-enrichment approach21,22 using samples that were 2% 15N-labeled. The power of the method can be appreciated by examining the spectra in Figure 3(a), which allow assignment of all 32 guanine imino protons. The guanine imino proton of each site-specific labeled residue was recognized on the basis of its intensity in the 15N-filtered spectrum (Figure 3(a)). Each spectrum showed four intense peaks corresponding to the labeled residue in the sequence. Again, this indicated the presence of four different structures of a strand in solution.

Figure 3.

(a) Guanine imino proton spectra with assignments indicated over the reference spectrum (ref). Imino protons were assigned in 15N-filtered spectra of samples, 2% 15N-labeled at the indicated positions. The reference spectrum was recorded using the same pulse sequence but with a different phase cycle. There are four peaks assigned for each imino proton. (b) Through-bond correlations between imino and H8 protons via 13C5 at natural abundance, using long-range J-couplings shown in the inset. Assignments of guanine H8 protons, labeled with residue numbers, were obtained from the already assigned imino protons. Peaks from T(H6) are labeled with stars. Experimental conditions: 25 °C; 100 mM NaCl; pH 7; strand concentration (a) 0.7–1.3 mM, (b) 10 mM.

The assignments of guanine H8 protons were obtained by through-bond correlation with the already assigned imino protons (Figure 3(b)) via 13C5 at natural abundance.23

Methyl and H6 protons of T6 and T7 were assigned by 13C-filtered experiments using site-specific 2% 13C,15N-labeled samples21,22 (see Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material).

Determination of the number of different G-quadruplexes

As mentioned above, although we know that the number of different strands is four, we do not know the number of different G-quadruplex structures built from these four strands. In order to determine how many different structures are present in solution, we performed a highly sensitive nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) experiment with a high-concentration sample (Figure 4). A NOESY cross-peak between two protons would indicate that these protons belong to the same structure. All cross-peaks were between different residues in the sequence, providing their dipolar nature, rather than exchange.

Figure 4.

NOESY spectrum (mixing time, 400 ms) (same conditions as for Figure 3(b)). This imino–imino proton region allows identification of two groups of peaks (blue and red) corresponding to two different structures, since in this experiment a NOE connectivity occurs only between protons belonging to the same structure. Both structures are asymmetric: each group has two sets of resonances corresponding to two different strands.

The very well resolved imino proton region (Figure 4) allowed us to sort out two sets of peaks in the spectrum (blue and red), which give rise to NOESY cross-peaks only within each family. In particular, 32 guanine imino protons could be divided into two groups of 16 peaks each (Figure 4). This indicated that there were two different structures, each of them containing two strands of different conformations. In other words, there were two different asymmetric dimeric G-quadruplexes in equilibrium in solution.

From G-tetrad alignments to G-quadruplex and loop folding topologies

The G-tetrad alignments could be defined from NOESY spectra (Figure 5(a)) on the basis of the specific imino–H8 connectivity pattern in a G-tetrad (Figure 5(b)). For example, in a G-tetrad (Gα·Gβ·Gγ·Gδ), the imino proton of Gβ, is connected to the H8 proton of the next guanine base, Gγ, while the H8 proton of Gβ is connected to the imino proton of the preceding Gα. Such a connectivity pattern determines the alignment of G-tetrads and the (donor–acceptor) hydrogen bond directionality around each G-tetrad. Examination of NOESY imino–H8 connectivities between already assigned imino and H8 protons (Figure 5(a)) revealed the formation of four G-tetrads for each structure: (G8·G8·G5·G5), (G9·G4·G4·G9), (G10·G10·G3·G3) and (G11·G2·G2·G11) for the “blue” structure; (G2·G8·G5·G11), (G3·G10·G4·G9), (G4·G10·G3·G9) and (G5·G8·G2·G11) for the “red” structure.

The G-quadruplex folding topologies were drawn from G-tetrad alignments. First, the G-tetrad core was established (see Figure S2 of the Supplementary Material) with four G-tracks as four columns (two G2–G3–G4–G5 and two G8–G9–G10–G11 for a dimer). The G-tetrad core of the two structures was similar in both strand orientations and glycosidic conformations (syn guanine bases were identified by strong intensities of H1′ –H8 cross-peaks in NOESY spectra). All G-tetrads adopted syn·syn·anti·anti alignments, which occurred with 5′-syn-anti-syn-anti-3′ alternations along G-tracks. The hydrogen bond directionalities around G-tetrads alternated clockwise and anticlockwise. The G-tetrad cores of the two structures differed in the relative position of G-tracks: two adjacent strands (α) and (β) mutually changed place in the blue structure compared to the red one (Figure S2).

Next, the loops T6–T7 were drawn by connecting G5 and G8. In the case of the blue structure, two edgewise loops at the same end of the G-tetrad core (Figure 5(c)) is the only possibility for connecting G5 to G8; connections by two diagonal loops would make a steric clash. In the case of the red structure, one can connect G5 to G8 by two edgewise loops at opposite ends of the G-tetrad core (Figure 5(d)), i.e. each loop connects G5 and G8 of the same G-tetrad. In both structures, the arrangement of loops on top of (and under) the G-tetrad core is supported by NOEs detected between the protons of T6/T7 and the protons of the external G-tetrads (Figure S1 in Supplementary Material and data not shown). For example, in the case of the red structure, such NOEs exclude double-chain-reversal loops, located in grooves and connecting G5 and G8 of opposite ends of the G-tetrad core. The topologies presented in Figure 5(c) and (d) are consistent with NOESY cross-peaks observed in other spectral regions such as the imino–imino and aromatic-sugar proton regions (Figure 4, and data not shown). They are also supported by the results of the exchange experiments, where the imino protons of the internal G-tetrads exchanged most slowly with the solvent (Figure 1(b)). From now on, we refer to the blue and the red structures as head-to-head and head-to-tail structures, respectively.

The two ends of the G-tetrad core in both structures were capped similarly with four thymine bases. However, the exchange times of imino protons of the external G-tetrads indicated that the top of the head-to-head structure was most protected from solvent (peaks with stars in Figure 1(b)), while the bottom of the same structure was least protected from solvent (data not shown).

Two G-quadruplexes are similarly stable in solution

Proton NMR spectra were recorded at equilibrium at different temperatures. The relative proportions of the two G-quadruplex forms, which were derived from the intensities of their corresponding imino, aromatic and methyl protons, were similar in a wide range of temperature, the head-to-head form being only slightly more favorable than the head-to-tail form at higher temperatures (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Imino proton spectra at equilibrium at (a) 25 °C and (b) 50 °C, showing that the relative proportion of the two G-quadruplexes depends weakly on the temperature. Imino protons of the head-to-head form and of the head-to-tail form are labeled with residue numbers in blue and red, respectively. At 25 °C, the fractions of the two forms are almost equal; at 50 °C, the head-to-head form is slightly more favored. Experimental conditions: 100 mM NaCl; pH 7; strand concentration 0.7 mM.

Unfolding kinetics of different G-quadruplexes

We studied the unfolding kinetics of the two G-quadruplex forms using the complementary-strand-trap method:19 the complementary C-strand was added in excess into the solution of the G-strand and the decay of the G-quadruplex concentrations was monitored by the intensities of guanine imino protons (Figure 7). It has been shown for the human telomere sequences that the unfolding times of G-quadruplexes measured by the complementary-strand-trap method were reliable and consistent with the measurements by the concentration-jump method.19 This is supported further by the fact that at a given temperature the unfolding times obtained here are independent of the concentration (0.2–2 mM) of the C-strand (data not shown). The unfolding times of the two G-quadruplex forms were similar for a wide range of temperature. They are plotted in Figure 8 as a function of temperature. The activation enthalpy was 153 kJ/mol. These unfolding times were about three times longer than those of the human telomere counterpart in K+-containing solution.19

Figure 7.

Measurement of unfolding times for G-quad-ruplexes by complementary strand trapping. (a) and (b) Imino proton spectra of the mixture (a) at time t = 0.1 hour and (b) at t = 14 hours. (c) An example of monitoring G-quadruplex concentration decay as a function of time by intensities of guanine imino protons (expanded from framed peaks in (a)). Imino protons of the head-to-head form and of the head-to-tail form are labeled with × and #, respectively. Experimental conditions: 35 °C; 80 mM NaCl; 20 mM sodium phosphate; pH 7; strand concentration, 0.4 mM for the G-strand and 2 mM for the C-strand.

Figure 8.

Unfolding times of the two G-quadruplexes as a function of temperature. Squares and triangles represent head-to-head and head-to-tail forms, respectively. For a comparison, unfolding times of the two G-quadruplexes from the human telomere d(UAGGGT5BrUAGGG) sequence,19 the antiparallel and the parallel G-quadruplexes, are plotted as broken lines with short and long dashes, respectively. Experimental conditions: 80 mM NaCl; 20 mM sodium phosphate; pH 7; strand concentration 0.04–0.4 mM.

Discussion

Novel asymmetric edgewise-looped dimeric G-quadruplex topologies

We have demonstrated that the two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) sequence formed two different asymmetric edgewise-looped dimeric G-quadruplex structures in Na+-containing solution. The two structures coexist at comparable proportions and interconvert in solution. The two structures, called head-to-head (Figure 5(c)) and head-to-tail (Figure 5(d)), have two edgewise loops at one end and at two opposite ends of the G-tetrad core, respectively.

For the G-tetrad core, the two structures are similar in strand orientations and glycosidic conformations of guanine bases (Figure S2 in Supplementary Material): the adjacent strands are alternately parallel and antiparallel; glycosidic conformations of the guanines are syn·syn·anti·anti around each G-tetrad and 5′-syn-anti-syn-anti-3′ along each G-track. The hydrogen bond directionalities, similar for the two structures, are alternately (starting from the top) clockwise and anticlockwise between adjacent G-tetrads in the quadruplex. The only difference in the G-tetrad core between the two structures is their relative position of G-tracks, which is related to the position of the loops.

For both structures, there are four thymine bases located in similar arrangements at each end of the G-tetrad core (Figure 5(c) and (d)). These residues may form T-tetrads, similar to those previously observed in the center of a G-quadruplex structure,24 and cap the ends of the G-tetrad core. Measurements of imino proton exchange times from external G-tetrads indicated the degrees of protection from solvent provided by these “caps”. In a comparison among the four ends, the head-to-head structure has the strongest protection from the two-loop end (the top end in Figure 5(c)) and the weakest protection from the other end, while the head-to-tail structure has similar medium protection from both ends. These degrees of protection are probably related to the stabilization (and/or destabilization) contributions of the loop and the terminal residues. Since the two structures coexist at comparable proportions and their G-tetrad core is similar, the (de)stabilization contributions of the loop and terminal residues must be similar for the two structures. This is consistent with the formation of one “strong cap” and one “weak cap” in the case of the head-to-head structure versus the formation of two “medium caps” in the case of the head-to-tail structure.

An interesting feature in each of the two dimers presented here is the inequivalence (or asymmetry) of the two (identical) strands. Considering the inherent difference between the G2–G5 and G8–G11 segments, the asymmetry is related to the G-tetrad core itself, involving the hydrogen bond directionalities. This asymmetry may be better described when one considers that each structure consists of two different hairpins (see Figure S3 of Supplementary Material). For instance, in one hairpin (A) the G5·G8 hydrogen bond alignment is formed through the imino/amino protons of G5 (Figure S3a), while in the other hairpin (B) the same G5·G8 hydrogen-bond alignment is formed through the imino/amino protons of G8 (Figure S3b). It is important to note that each hairpin (A and B) is present in both structures. The two structures are formed by two different ways of hetero-association of the two hairpins, namely head-to-head and head-to-tail. It is interesting that no “homodimers” (e.g. hairpin A/hairpin A or hairpin B/hairpin B) were observed for this sequence. A homodimeric association of the two hairpins would generate a different G-tetrad core (with all adjacent strands antiparallel and syn·anti·syn·anti alignments around G-tetrads), which is probably less stable than the observed G-tetrad core (as described above).

We have examined the two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) sequence in K+-containing solution. The NMR spectra were sensitive to the sample preparation procedures (e.g. time of dialysis, time and temperature for annealing), but in all cases were very different from those in Na+-containing solution presented here. Although the quality of NMR spectra we obtained so far was insufficient for detailed structural analysis, they suggested the presence of yet another G-quadruplex folding topology (our unpublished results). We are currently working on identifying sample preparation procedures that improve NMR spectra quality for more detailed structural characterization.

Comparison with other G-quadruplex topologies

So far, the most frequently studied dimeric G-quadruplex topology is the head-to-tail diagonal-looped G-quadruplex.12–18 The first structure from this family was the G-quadruplex structure of the two-repeat Oxytricha telomeric d(G4T4G4) sequence solved by NMR.12,13 This sequence forms in the presence of various monovalent cations, including Na+ or K+, a dimeric G-quadruplex with diagonal loops at opposite ends. The G-tetrad core of this Oxytricha G-quadruplex is similar to that of the Tetrahymena sequence from this study with respect to strand orientations, syn/anti distributions and hydrogen bond directionalities. However, the loop topologies of the latter are quite different from the loop T4 of the Oxytricha sequence, which spans the diagonal, not the edge of the quadruplex. The formation of the same G-tetrad core with different loop motifs suggests that such a G-tetrad core topology (as described above) is more stable compared to alternative G-tetrad core topologies. In addition, the stabilization contributions of the G-tetrad core are probably much larger than those of the loops.

The head-to-tail edgewise-looped dimeric G-quadruplex topology has been observed on several occasions,25–29 including recently in the antiparallel G-quadruplex from human telomeric DNA.19 However, in all these cases, in contrast to the head-to-tail structure from this study, the G-tetrad core was formed with all adjacent strands antiparallel, which resulted in syn·anti·syn·anti alignments around G-tetrads.

The head-to-head edgewise-looped dimeric G-quadruplex topology has been proposed.5 So far, it has been observed only for a quadruplex with G·C·G·C-tetrads by X-ray30 and for another quadruplex with G·C·G·C/A·T·A·T-tetrads by NMR.31 In these examples, again, all adjacent strands from the quadruplex were antiparallel, in contrast to the parallel/antiparallel alternation in the head-to-head structure from this study.

The topologies observed in this study expand the repertoire of bimolecular G-quadruplexes, which is in continuous growth, with recent identifications of a propeller-type parallel-stranded G-quadruplex7,19 and a mixed edgewise/diagonal G-quadruplex.32 The importance of the connecting linker and terminal residue sequences are clear from these studies.

Finally, it is interesting to compare the structures of the dimeric G-quadruplexes reported here with the G-quadruplex structure of the four-repeat Tetrahymena d(T2G4)4 sequence in Na+-containing solution reported previously.8 The latter sequence folds intramolecularly into a G-quadruplex containing three G-tetrads connected by two edgewise loops and one double-chain-reversal loop. The structures presented here for the two-repeat Tetrahymena sequence are very different and do not share any similarity in the loop topology, the orientation of strands or the alternation of glycosidic syn/anti conformations with the four-repeat counterpart. These results were surprising, since G-stretches of these sequences are separated by the same TT linker. It would be interesting to understand the origin of this difference.

G-quadruplex unfolding: kinetics and possible pathways

In contrast to the two G-quadruplexes from the human telomere counterpart,19 the head-to-head and head-to-tail G-quadruplex structures in this study unfold at very similar rates for a wide range of temperatures. For each structure, the unfolding could first occur by unzipping of two hairpins.

Technical benefits for G-quadruplex research

The propensity of G-rich sequences to form a variety of G-quadruplex topologies leads to many occasions when there is coexistence of several interconverting structures in solution. The two-repeat Tetrahymena telomeric d(TGGGGTTGGGGT) sequence described here is an example of a highly challenging and complicated case, since four different strand conformations coexist in solution. However, the folding topology of each structure could be elucidated unambiguously using site-specific, low-enrichment labeling and through-bond correlations at natural abundance. This study illustrates NMR methods for investigation of unusual DNA structures and, in particular, demonstrates the utility of NMR techniques for monitoring interconverting G-quadruplexes at high resolution.

The novel G-quadruplex topologies presented here could be studied further by other techniques such as UV, CD, Raman, or UV resonance Raman spectroscopy to identify new markers for novel structural motifs.33

Biological significance

The telomere is a nucleoprotein structure located at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes. It is essential for genome integrity. Telomeric DNA contains tandem repeats of G-rich sequences on one strand and corresponding C-rich sequences on the other strand. Most of telomeric DNA is double-stranded, except for the extreme 3′-terminal G-rich overhang, which is single-stranded.34 This overhang strand, and even a terminal duplex portion, may invade the preceding telomeric double-stranded part, forming the so-called t-loop.35,36 Thus, in the telomere, the G-rich strand can exist in many states, as a single strand or in different complexes with the complementary strand.

While the G-rich strand can form the G-quadruplex, the C-rich strand can form another unusual structure, called the i-motif, with intercalated C·C+ base-pairs.37,38 In vitro, the 1:1 mixture of the G-rich and the C-rich strands forms predominantly a Watson–Crick duplex under near-physiological conditions, but the duplex could unfold to form the G-quadruplex and the i-motif, respectively, under other conditions such as low pH.39 In cells, interactions of either strand with other molecules, such as proteins, could modulate the structure of the complexes. For example, a protein could specifically recognize only one of the two G-quadruplex forms for biological functions in telomeres. We are currently working on identifying specific ligands that target only one G-quadruplex form, which in turn can be used to study such biological functions.

On the other hand, the single-stranded 3′ overhang G-rich strand is considered to be more likely to form G-quadruplex structures. It has been shown that such structures inhibit telomerase, the enzyme responsible for telomere replication.40 Therefore, the G-quadruplex structures from telomeric sequences are convincingly considered potential targets for anticancer drugs. In order to design better ligands, one should understand the folding topology of G-quadruplexes. So far, most of the identified ligands interact with G-quadruplexes by stacking on the external G-tetrads. In the two G-quadruplex topologies presented here, one can target separately one or the other end of the head-to-head structure, or the two similar ends of the head-to-tail structure.

Another factor that could determine the amount of G-quadruplexes in the telomere during the cell-cycle is their folding/unfolding kinetics. This parameter depends on the environment conditions and can be modulated by interactions with proteins or small ligands.41–43

In addition, we note that understanding G-quadruplex structural elements (G-tetrad core and loops), as well as their folding/unfolding kinetics, would also help in designing new scaffolds for useful molecular shapes10,44 or for basis of nanodevices.45,46

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

The unlabeled and site-specific low-enrichment labeled oligonucleotides were synthesized and purified as described.6 Eight samples (2% 15N-labeled at individual G positions) and two samples (2% 15N,13C-labeled at T6 or T7) were synthesized at a 2 μmol scale with low-enrichment labeled phosphoramidites prepared as described.21,22 In all cases, samples were dialyzed successively against 50 mM NaCl and against water. Unless stated otherwise, the strand concentration of the NMR samples was typically 0.5–10 mM; the solutions contained 100 mM NaCl; the sample pH was adjusted to pH 7 with HCl and NaOH solutions. The samples were heated at 90 °C for three minutes and annealed slowly to room temperature.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

NMR experiments were performed on a 600 MHz Varian Unity INOVA spectrometer. Experiments in H2O used the jump-and-return (JR) water suppression47 for detection. Resonances were assigned using site-specific, low-enrichment labeling,21,22 through-bond correlations at natural abundance20,23 and NOESY (see Results). NMR titration for stoichiometry determination was performed at 50 °C on samples in H2O based on signals of different imino and aromatic protons, using the JR pulse sequence with a repetition delay of five seconds.

Unfolding kinetic measurements

The unfolding times of the two G-quadruplexes were determined using the complementary-strand-trap method as described.19 At a given temperature, the complementary C-strand d(ACCCCAACCCCA) was added to the G-strand in order to trap the latter into a Watson–Crick duplex. The concentrations of G-quadruplex structures would decay through G-quadruplex-to-single strand transitions; the reverse reaction was inhibited because the unfolded G-strand was trapped. The unfolding of each G-quadruplex was followed in real time by their characteristic imino protons. In our experimental conditions (strand concentrations of the G-strand and of the C-strand were 0.05–0.4 mM and 0.2–2.0 mM, respectively), the hybridization between the two strands occurred quickly and was not a limiting step for the unfolding. The concentration of each G-quadruplex could be described as a single exponential decaying towards zero:

where C(0) and C(t) were the concentration of the G-quadruplex form at time zero and at time t, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jayakrishnan Nandakumar and Firaz Mohideen for their participation at the early stage of this study. This research was supported by NIH GM34504.

Abbreviations used

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- NOESY

NOE spectroscopy

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.042

References

- 1.Mergny JL, Hélène C. G-Quadruplex DNA: a target for drug design. Nature Med. 1998;4:1366–1367. doi: 10.1038/3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley LH. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2002;2:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrc749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neidle S, Parkinson G. Telomere maintenance as a target for anticancer drug discovery. Nature Rev Drug Des. 2002;1:383–393. doi: 10.1038/nrd793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel DJ, Bouaziz S, Kettani A, Wang Y. Structures of guanine-rich and cytosine-rich quadruplexes formed in vitro by telomeric, centromeric, and triplet repeat disease DNA sequences. In: Neidle S, editor. Oxford Handbook of Nucleic Acid Structures. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. pp. 389–453. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonsson T. G-quadruplex DNA structures—variations on a theme. Biol Chem. 2001;382:621–628. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure. 1993;1:263–282. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson GN, Lee MPH, Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the Tetrahymena telomeric repeat d(T2G4)4 G-tetraplex. Structure. 1994;2:1141–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the Oxytricha telomeric repeat d[G4(T4G4)3] G-tetraplex. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:76–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultze P, Macaya RF, Feigon J. Three-dimensional solution structure of the thrombin-binding DNA aptamer d(GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG) J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1532–1547. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuryavyi V, Majumdar A, Shallop A, Chernichenko N, Skripkin E, Jones R, Patel DJ. A double chain reversal loop and two diagonal loops define the architecture of a unimolecular DNA quadruplex containing a pair of stacked G(syn). G(syn).G(anti).G(anti) tetrads flanked by a G.(T-T) Triad and a T.T.T triple. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:181–194. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith FW, Feigon J. Quadruplex structure of Oxytricha telomeric DNA oligonucleotides. Nature. 1992;356:164–168. doi: 10.1038/356164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultze P, Hud NV, Smith FW, Feigon J. The effect of sodium, potassium and ammonium ions on the conformation of the dimeric quadruplex formed by the Oxytricha nova telomere repeat oligonucleotide d(G4T4G4) Nucl Acids Res. 1999;27:3018–3028. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath MP, Schultz SC. DNA G-quartets in a 1.86 Å resolution structure of an Oxytricha nova telomeric protein-DNA complex. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:367–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haider S, Parkinson GN, Neidle S. Crystal structure of the potassium form of an Oxytricha nova G-quadruplex. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00428-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haider SM, Parkinson GN, Neidle S. Structure of a G-quadruplex–ligand complex. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith FW, Lau FW, Feigon J. d(G3T4G3) forms an asymmetric diagonally looped dimeric quadruplex with guanosine 5′-syn-syn-anti and 5′-syn-anti-anti N-glycosidic conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10546–10550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crnugelj M, Hud NV, Plavec J. The solution structure of d(G4T4G3)2: a bimolecular G-quadruplex with a novel fold. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:911–924. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan AT, Patel DJ. Two-repeat human telomeric d(TAGGGTTAGGGT) sequence forms interconverting parallel and antiparallel G-quadruplexes in solution: distinct topologies, thermodynamic properties and folding/unfolding kinetics. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15021–15027. doi: 10.1021/ja037616j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phan AT, Guéron M, Leroy JL. Investigation of unusual DNA motifs. Methods Enzymol. 2001;338:341–371. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)38228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phan AT, Patel DJ. A site-specific low-enrichment 15N,13C isotope-labeling approach to unambiguous NMR spectral assignments in nucleic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1160–1161. doi: 10.1021/ja011977m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan AT, Patel DJ. Differentiation between unlabeled and very-low-level fully 15N,13C-labeled nucleotides for resonance assignments in nucleic acids. J Biomol NMR. 2002;23:257–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1020277223482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phan AT. Long-range imino proton-13C J-couplings and the through-bond correlation of imino and non-exchangeable protons in unlabeled DNA. J Biomol NMR. 2000;16:175–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355231085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel PK, Hosur RV. NMR observation of T-tetrads in a parallel stranded DNA quadruplex formed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomere repeats. Nucl Acids Res. 1999;27:2457–2464. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang C, Zhang X, Ratliff R, Moyzis R, Rich A. Crystal structure of four-stranded Oxytricha telomeric DNA. Nature. 1992;356:126–131. doi: 10.1038/356126a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kettani A, Kumar RA, Patel DJ. Solution structure of a DNA quadruplex containing the fragile X syndrome triplet repeat. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:638–656. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kettani A, Bouaziz S, Gorin A, Zhao H, Jones RA, Patel DJ. Solution structure of a Na cation stabilized DNA quadruplex containing G.G.G.G and G.C.G.C tetrads formed by G-G-G-C repeats observed in adeno-associated viral DNA. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:619–636. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouaziz S, Kettani A, Patel DJ. A K cation-induced conformational switch within a loop spanning segment of a DNA quadruplex containing G-G-G-C repeats. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:637–652. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kettani A, Basu G, Gorin A, Majumdar A, Skripkin E, Patel DJ. A two-stranded template-based approach to G.(C-A) triad formation: designing novel structural elements into an existing DNA framework. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:129–146. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard GA, Zhang S, Peterson MR, Harrop SJ, Helliwell JR, Cruse WB, et al. Self-association of a DNA loop creates a quadruplex: crystal structure of d(GCATGCT) at 1.8 Å resolution. Structure. 1995;3:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang N, Gorin A, Majumdar A, Kettani A, Chernichenko N, Skripkin E, Patel DJ. Dimeric DNA quadruplex containing major groove-aligned A.T.A.T and G.C.G.C tetrads stabilized by inter-subunit Watson–Crick A.T and G.C pairs. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:1073–1088. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crnugelj M, Sket P, Plavec J. Small change in a G-rich sequence, a dramatic change in topology: new dimeric G-quadruplex folding motif with unique loop orientations. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7866–7871. doi: 10.1021/ja0348694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krafft C, Benevides JM, Thomas GJ., Jr Secondary structure polymorphism in Oxytricha nova telomeric DNA. Nucl Acids Res. 2002;30:3981–3991. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makarov VL, Hirose Y, Langmore JP. Long G tails at both ends of human chromosomes suggest a C strand degradation mechanism for telomere shortening. Cell. 1997;88:657–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stansel RM, de Lange T, Griffith JD. T-loop assembly in vitro involves binding of TRF2 near the 3′ telomeric overhang. EMBO J. 2001;20:5532–5540. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gehring K, Leroy JL, Guéron M. A tetrameric DNA structure with protonated cytosine. cytosine base pairs. Nature. 1993;363:561–565. doi: 10.1038/363561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phan AT, Guéron M, Leroy JL. The solution structure and internal motions of a fragment of the cytidine-rich strand of the human telomere. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:123–144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phan AT, Mergny JL. Human telomeric DNA: G-quadruplex, i-motif and Watson–Crick double helix. Nucl Acids Res. 2002;30:4618–4625. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zahler AM, Williamson JR, Cech TR, Prescott DM. Inhibition of telomerase by G-quartet DNA structures. Nature. 1991;350:718–720. doi: 10.1038/350718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raghuraman MK, Cech TR. Effect of monovalent cation-induced telomeric DNA structure on the binding of Oxytricha telomeric protein. Nucl Acids Res. 1990;18:4543–4552. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang G, Cech TR. Characterization of a G-quartet formation reaction promoted by the β-subunit of the Oxytricha telomere-binding protein. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11646–11657. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han H, Cliff CL, Hurley LH. Accelerated assembly of G-quadruplex structures by a small molecule. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6981–6986. doi: 10.1021/bi9905922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jing N, Hogan ME. Structure-activity of tetrad-forming oligonucleotides as a potent anti-HIV therapeutic drug. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34992–34999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li JWJ, Tan WH. A single DNA molecule nanomotor. Nano Letters. 2002;2:315–318. doi: 10.1021/nl9011694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alberti P, Mergny JL. DNA duplex–quadruplex exchange as the basis for a nanomolecular machine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1569–1573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335459100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plateau P, Guéron M. Exchangeable proton NMR without base-line distortion using strong pulse sequences. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:7310–7311. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.