Abstract

Context:

Increased media attention on surgical procedures that were performed on the wrong anatomic site or wrong patient has prompted the health care industry to identify and address human factors that lead to medical errors.

Objective:

To increase patient safety in the perioperative setting, our objective was to create a climate of improved communication, collaboration, team-work, and situational awareness while the surgical team reviewed pertinent information about the patient and the pending procedure.

Methods:

A team of doctors, nurses, and technicians used human factors principles to develop the Preoperative Safety Briefing for use by surgical teams, a briefing similar to the preflight checklist used by the airline industry. A six-month pilot of the briefing began in the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Anaheim Medical Center in February 2002. Four indicators of safety culture were used to measure success of the pilot: occurrence of wrong-site/wrong procedures, attitudinal survey data, near-miss reports, and nursing personnel turnover data.

Results:

Wrong-site surgeries decreased from 3 to 0 (300%) per year; employee satisfaction increased 19%; nursing personnel turnover decreased 16%; and perception of the safety climate in the operating room improved from “good” to “outstanding.” Operating suite personnel perception of teamwork quality improved substantially. Operating suite personnel perception of patient safety as a priority, of personnel communication, of their taking responsibility for patient safety, of nurse input being well received, of overall morale, and of medical errors being handled appropriately also improved substantially.

Conclusions:

Team members who work together and communicate well can quickly detect and more easily avoid errors. The Preoperative Safety Briefing is now standard in many operating suites in the KP Orange County Service Area. The concepts and design of this project are transferable, and similar projects are underway in the Departments of Radiology and of Labor and Delivery at KP Anaheim Medical Center.

Introduction

Our patients and their families reasonably expect us to maintain patient safety in the medical environment. Until recently, however, this critical component of medical care did not receive the attention it deserves. Against a background of increased mass media attention to hospital errors, such as performing wrong procedures or performing procedures on the wrong anatomic site or wrong patient as reported in the Institute of Medicine’s 1999 report, “To Err is Human”1 and in Lucien Leape’s landmark article, “Error in Medicine,”2 the medical profession has finally realized that safety is an integral part of the health care that we deliver. These trends, coupled with three wrong-site surgeries and several near misses in the previous year, prompted the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Orange County Service Area (OCSA) to embrace a fundamental cultural change that emphasized safety as part of clinical quality standards of defining the care experience for our health care providers and patients.

Other industries, most notably the aviation industry, have long known the importance of human factors in the etiology of errors and have sought to identify and address human factors that result in errors. KP OCSA already followed several patient safety policies and procedures in the surgical suite, such as use of the Patient Procedure Site Marking Verification Form, to meet Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) regulations. However, the Safety, Human Factors, and Preoperative Safety Briefing project was intended to supplement and to add another dimension to patient safety practices by creating a culture whereby team members are formally identified and create a shared mental model by focusing on the patient minutes before the surgical procedure. The project was designed and implemented by a team consisting of surgeons, operating room nurses, anesthesiologists, nurse anesthetists, scrub technicians, quality coordinators, risk managers, and administrators (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preoperative Safety Briefing Team members

Team leadership:

|

|

|

Team members:

|

According to the JCAHO, breakdown in communication is the primary cause of serious sentinel events in the healthcare setting; 75% of these events result in patient death.3 On the basis of this and other human factors analysis and design, a Preoperative Safety Briefing for surgical teams in the KP OCSA was developed: a document and procedure very similar to the preflight checklist used by pilots. The purpose of the briefing is to maximize the ability of health care providers to effectively identify and manage human error and other threats to patient safety. Important elements of the project design included creation of a climate of improved communication, collaboration, team-work, and situational awareness in the perioperative setting.

The Safety, Human Factors, and Preoperative Safety Briefing project focused on these five specific objectives:

To build awareness of safety culture and identify safety needs.

To build support by enhancing staff knowledge of the existing “operating suite culture” and potential barriers to safety inherent in that environment.

To develop a Preoperative Safety Briefing model to enhance effective communication and anticipation/management of threats and errors.

To educate all stakeholders and implement the Preoperative Safety Briefing model in the operating suite.

To evaluate the model’s success using prepilot and postpilot attitudinal surveys.

Developing the Preoperative Safety Briefing

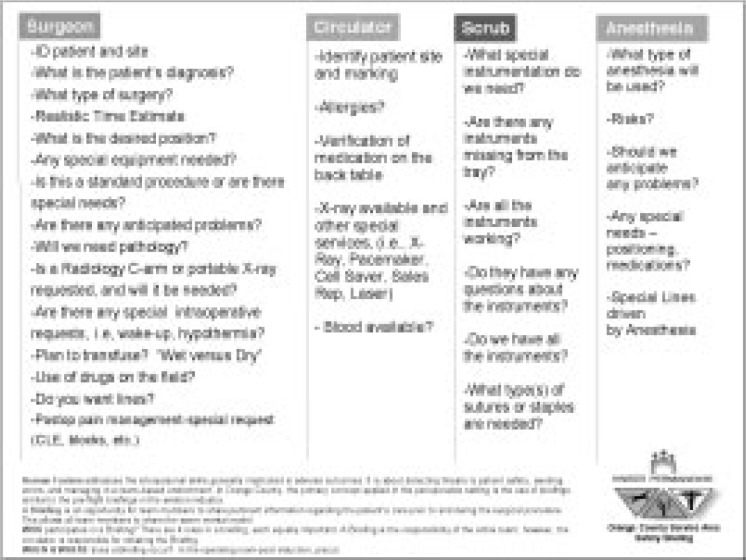

The project centered around the Preoperative Safety Briefing, a brief activity in which the members of the surgical team discuss the background of the case, assess threats and risks, and offer any other relevant information. A one-page document reminds team members of key relevant questions regarding patient safety (Figure 1). The briefing is required after induction and before a surgical procedure. Briefings are also encouraged at handoffs and other special situations (eg, training new team members). Although simple, the briefing design encourages and requires collaboration and consensus from each member of the perioperative team. In addition, the check-in procedure fosters a more collegial atmosphere, which encourages monitoring, facilitates cross-checking, and empowers all team members to be proactive about patient safety in the perioperative setting.

Figure 1.

Preoperative Safety Briefing document used by surgical teams in the KP Orange County Service Area.

(Logo of the University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice reproduced by permission of the Center.)

The Human Factors Steering Committee presented the original concept to key members of the operating staff, anesthesia department, and surgical services at the KP Anaheim Medical Center in October 2001. Components of the Preoperative Safety Briefing were designed by a team consisting of operating room and anesthesia staff and surgeons from different disciplines, who then met monthly to develop and later to refine the design used in training their staff and colleagues until the pilot started in February 2002. Quantitative results of monthly surveys during the pilot helped the team to improve the design, identify other safety supplements and tools (such as a training module), and offer rapid feedback to operating suite staff and physicians about the influence of the briefing on safety and teamwork climate. Anonymous suggestions collected in a box outside the Perioperative Services Department Administrator’s office provided qualitative data. Both sets of information allowed the team to quickly identify and resolve concerns during the pilot period. For example, one anonymous suggestion proposed placing a whiteboard in each of the operating rooms to list the four primary roles and the name of each person in that role for the current case. Studies have shown that knowing the names of other team members greatly improves prevention of adverse outcomes. This simple addition to the Preoperative Safety Briefing added tremendous value; more important, this type of rapid cycle change process provided the global framework for problem-solving in the operating suite.

Preoperative Safety Briefing Pilot

The Preoperative Safety Briefing six-month pilot beginning in February 2002 consisted of several steps.

Program Measures

Measuring clinical outcomes as a result of improved operating suite safety culture is difficult. Unexpectedly poor clinical outcomes in the operating suite that are attributable to human factors are rare, especially in a culture that drives toward zero tolerance of performing wrong-site/wrong procedures. However, various types of risk data were collected and, as a means to measure the program’s progress and success, the following four indicators of safety culture were used: occurrence of wrong-site/wrong procedures, questionnaire results, near-miss reports, and nurse turnover data.

Risk Data

The risk data compiled were the number and severity of Unusual Occurrence Reports; the number of near-miss reports; reports of faulty or missing equipment or instrumentation (or both) with subsequent case delays; nurse retention rates and nursing position openings; concerns and issues raised confidentially via a closed message box in the operating suite; and comments by operating suite team members after cases, as written in an open (ie, nonconfidential) log kept at the front desk.

Although risk reduction was inherent in design of the project, the data were minimally reviewed at each monthly pilot project team meeting to safeguard against unrecognized negative impacts or unintended consequences.

Safety Attitudes Questionnaire

The largest source of data was a series of Safety Attitudes Questionnaires (SAQs) administered to physicians and operating suite staff. Attitude, as measured by validated instruments, can predict work performance and can be changed through training and environmental changes. Attitude in personnel in the health care setting can be related statistically to patient outcome; aggregated attitude scores reflect the culture or climate of the organization.4–6

The SAQs used in our pilot were developed by the Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice at the University of Texas7 and have been used in more than 450 hospitals and their departments in the United States, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. SAQs are designed to assess the following factors that are linked to risk-adjusted patient mortality and nursing turnover:4 job satisfaction, perceptions of management, teamwork climate, safety climate, stress recognition, and working conditions. Participants read a series of statements and are asked to respond with “Agree Strongly,” “Agree Slightly,” “Neutral,” “Disagree Slightly,” or “Disagree Strongly.” Table 2 shows sample SAQ statements; responses to this subset of statements were used to measure the perceived safety climate of the participant’s clinical area. An SAQ was administered in the OCSA in August 2001, which was six months before project design began, and again in September 2002, after completion of the pilot. Each participant was given a survey and asked to return the completed survey in a sealed envelope to the charge nurse. Response rate for the prepilot SAQ was 75% and for the postpilot SAQ was 88%; 59 operating suite staff and 60 surgeons at KP Anaheim Medical Center were surveyed. In addition, a subset of questions from the SAQ was administered to participants monthly during the pilot to track progress.

Table 2.

Subset of statements on the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire used to evaluate the perceived safety climate in the perioperative setting8

| I would feel safe being treated here as a patient. |

| I am encouraged by my colleagues to report any patient safety concerns I may have. |

| Patient safety is constantly reinforced as the priority in this clinical area. |

| I know the proper channels to direct questions regarding patient safety in this clinical area. |

| Medical errors are handled appropriately in this clinical area. |

| The culture of this clinical area makes it easy to learn from the mistakes of others. |

| Personnel frequently disregard rules or guidelines (eg, hand washing, sterile field, etc) that are established for this clinical area. |

Results

Improved Safety Indicators

Three wrong-site surgeries were reported in 2001, but none were reported in 2002; in fact, the Orange County Surgical Services Team has not experienced a single wrong-site/wrong procedure incident since the introduction of the Preoperative Safety Briefing. Quality Management analyzed the three incidents in 2001 and determined that they might have been prevented with use of the Preoperative Safety Briefing.

Quality Management monitored the number of reports of near misses and of faulty or missing equipment to measure change in situational awareness and nurturing of a blame-free environment. An increase in the number of near misses reported was assumed to signal that operating suite staff and surgeons were becoming more willing to admit errors; the number of near misses reported increased from zero in 2001 to 5 in 2002. Compared with 2001, reports of faulty or missing equipment and instrumentation decreased slightly in 2002, but the frequency at which operating suite or anesthesia time was extended or cases were delayed or canceled subsequent to issues with equipment may have decreased and is being evaluated. These results suggest that the Preoperative Safety Briefing facilitates early reporting of equipment issues and that this reporting leads to timely solutions that enhance patient care in the perioperative setting and minimize operational costs.

Improved Safety and Teamwork Climate

The improved SAQ scores occurred after the pilot validated the importance of the briefing in changing the teamwork and safety climate in the operating suite; each of the factors linked to risk-adjusted patient mortality and nursing turnover showed statistically significant improvement. Team identification, communication, and collaboration also increased significantly.

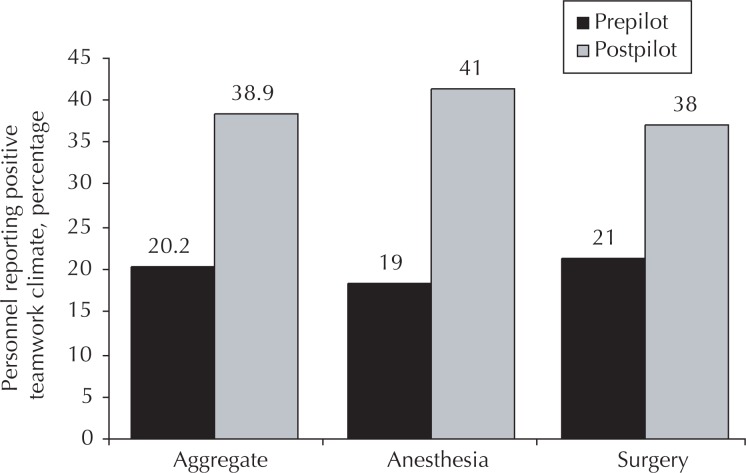

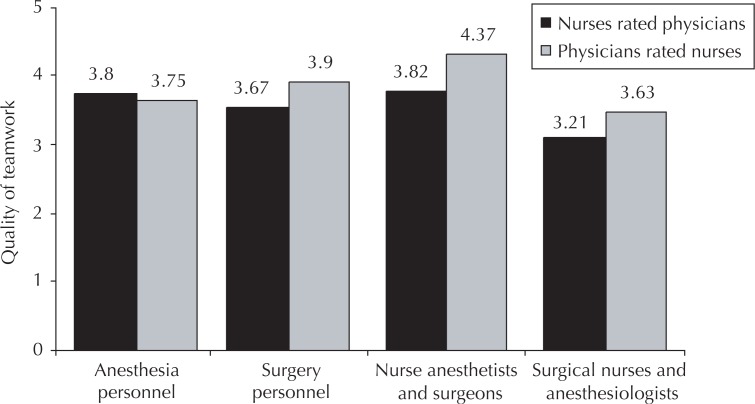

The percentage of operating suite personnel who agreed or strongly agreed that the safety climate in the perioperative setting was good increased from 51.1% to 62.9% after completion of the pilot, a substantial increase. Substantial improvement was also seen in operating suite personnel perceived team-work climate (Figure 2) and in their perception of priority of patient safety in the operating suite, of communication, of their taking responsibility for patient safety, of nurse input being well received, and of medical errors being handled appropriately. In addition, personnel reportedly found it easier to speak up when they identified a problem in patient care and found it easier to discuss mistakes. Throughout the reporting period, the perception of teamwork was somewhat influenced by the discipline and job of participants; physicians consistently gave nurses higher teamwork scores than nurses gave physicians (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Change in the perception of teamwork climate among operating suite personnel after implementation of Preoperative Safety Briefing. Anesthesia personnel included physicians and certified registered nurse assistants. Surgery personnel included surgeons and operating suite team members.

Figure 3.

Comparison of perceived quality of teamwork between disciplines and personnel throughout the pilot study. Quality of Teamwork rated on a scale from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very high”).

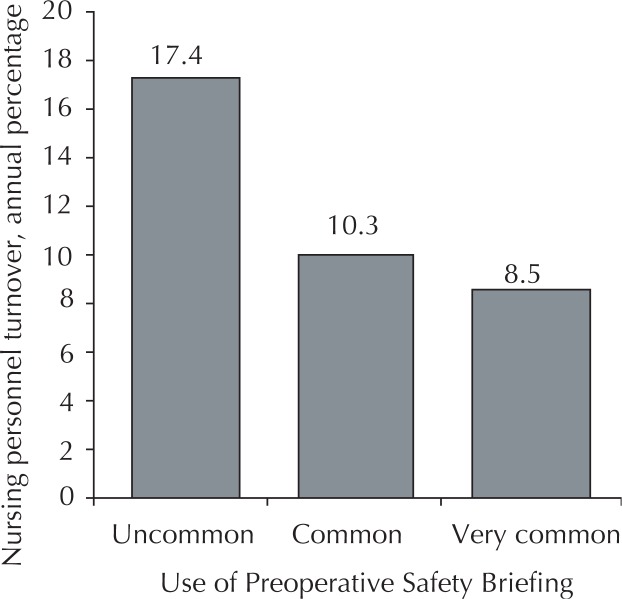

Improved Morale

As use of the Preoperative Safety Briefing became more common, morale among operating suite personnel improved—especially among nurses—an improvement that was reflected by increased nurse retention rates (Figure 4). In May 2001, Orange County had 20 open nursing positions, and the turnover rate was 23%. In May 2003, six nursing positions were open, and the turnover rate was 7%.

Figure 4.

Turnover of registered nurses in KP OCSA decreased as use of the Preoperative Safety Briefing became more common among operating suites.

Minimal Cost and Change to Organizational Structure

Minimal fiscal support was required. Support necessary for the initial design and implementation phase of the Preoperative Safety Briefing included a project manager (at 0.25 FTE) and ancillary support time (at 0.25 FTE) and training materials. Nonpersonnel resources included conferences, the implementation toolkit, and training sessions at a total project cost of approximately $49,500. Physician and Labor leadership, after implementation and continued ancillary support time, will be required to sustain the gains at an estimated cost of $15,500. As part of our efforts to sustain the success of the Briefing, KP Orange County has institutionalized the role of the Physician Director of Patient Safety (with administrative time attached) to support a broader culture of safety there. Much of the administrative time spent on this project by the Perioperative Department Administrator, the Quality Management Coordinator, Quality Leader, and Risk Manager was absorbed by their normal daily operations. The operating suite staff members were compensated for attending the steering committee meetings and for attending training sessions.

Discussion

As an organization that cares about its members and employees, KP has a responsibility to create and maintain a culture of safety, because “Safety comes first, before quality, service, and profit.” Injuries and errors such as wrong-site surgeries have tremendous personal cost to the patient and employee and are a significant financial liability for KP. In addition, the factors that enable severe errors also lead to decreased morale and poor staff retention rates. Human Factors principles provide a straightforward method for preventing errors by improving team communication and collaboration. Creating a team with a healthy balance between vertical and lateral communication allows team members to identify variation in processes and to develop system modifications to reduce inappropriate variation, which ultimately empowers everyone—-surgeon, anesthesia and operating room staff alike—to act as an agent for change.

In 2002, KP Orange County personnel reported that briefings were approximately 1.5 times more common than the year before, and respondents who reported good team-work climate nearly doubled during this time. Team identification, communication, and collaboration have increased substantially, potential problems are identified and resolved preoperatively, and situational awareness has been heightened as shown by increased reporting of near-miss situations.

After its introduction in 2002, the Preoperative Safety Briefing potentially improved the safety of every patient who had a procedure done in the operating suite at the KP Anaheim Medical Center. In 2002, OCSA membership was more than 340,000, and of the 16,042 operating suite procedures performed in Orange County in 2002, 6795 (43%) were done at the KP Anaheim Medical Center.

A small investment was necessary for designing and implementing the change, but the resource allocation was easily absorbed into the existing cost structure and required a minimal, shared commitment among the perioperative team members. The rewards of this change were a clear, shared focus on the patient. The goal was achieved of lessening the gap between positive perception of teamwork by physicians rating nurses and somewhat lower positive perception of team-work by nurses rating physicians. Greater satisfaction among operating suite staff was indicated by decreased nurse turnover. Increased operational efficiency was indicated by reduced delays in receiving operating suite equipment and reduced case delays or cancellations and an overall heightened awareness of patient safety initiatives.

Broad-based Participation

The critical success factor of this project has been the project’s team commitment to designing and implementing these cultural changes in their environment. The multidisciplinary project team consisted of surgeons, operating suite nurses, anesthesiologists, nurse anesthetists, scrub technicians, quality coordinators, and administrators. Janice Bouma, RN, represented the United Nurses’ Association of California, and Ed Marthaler, CRNA, represented the Kaiser Permanente Nurse Anesthetist Association (KPNAA). Five of the 16 members, or approximately 31% of the Steering Committee, represented Labor. From the project’s inception to implementation and refinement, Labor was a true partner. The local Leadership Team’s recognition of the Human Factors principles’ impact on patient and workplace safety and their support through application to other services reaffirm this project’s value to Labor and Labor’s commitment to share in the accountability of developing a safety culture throughout the OCSA. Labor representatives submitted testimonials praising the program (Table 3).

Table 3.

Testimonials submitted by Labor Representatives after implementation of the Preoperative Safety Briefing

| “Safety Briefings I believe have done a lot of things particularly for safety in the OR from the scrub tech point of view. It helps me focus on what I should be prepared to do for the procedure. Cases go smoothly when you have all the supplies that you need and the atmosphere in the room is much more enjoyable for ‘all’ because you know you’re ready. Good communication and teamwork is always better.” — Nerisa Contreras, OR Technician |

| “I think Safety Briefings done before surgery are great! Good for patients and for the OR team. Because of the Briefings, everyone is on the same page and cases run smoothly, with less time for the Circulators running for equipment. I would not want to work in an OR without Human Factors Safety Briefings” — Tommy Encinas, OR Technician |

| “I have enjoyed the concept and practice of the Safety Briefing. This is an opportunity for a collegial atmosphere that can set the tone for each operation, if not the entire day. All of us strive to do our best and safest work for each patient and this exercise can help keep each provider in sync.” — Kathi Ryan, CRNA |

| “When the surgeon takes the time for the Safety Briefing prior to starting the case, to address each issue regarding the patient’s surgery with the whole OR team, the whole case flows more smoothly and questions can be addressed prior to the start of surgery. It is nice to hear the expectations of the surgeon, anesthesia, circulator and scrub before the start of surgery, putting us all on the ‘same page.’ All of the above does contribute to the overall safety and well-being of the patient and staff.” — Sharon Romerson, RN |

| “For the few focused moments the Safety Briefing requires, it has produced so much valuable information for all the surgical team members. Many times either the surgeon or myself has produced new information from the patient or old charts which have changed the patient care. The old saying ‘Oh, by the way, did you know …?’ comes alive in the briefing. Many times this changes our approach in anesthesia and immediate post-op care. It is always reassuring to have one last team focus on the correct side, correct procedures and correct patient. Such a short process—such rewards.” — Ed Marthaler, CRNA |

| “From a circulating nurse’s point of view, the Human Factors/Safety Briefings begin in the holding area when we verify the procedure with the patient verbally and by marking the operative site. This immediately reassures the patient that we are beginning a process of avoiding mistakes. The process continues in the room with the surgeon present along with the scrub nurse and anesthesia. At this time, the team verifies all of the pertinent items from the Human Factors components, and each member of the team is given an opportunity to contribute any information particular to their function. This sharing of parts is what makes for more of a team atmosphere, although the participation of surgeons varies. “Anticipation is one of the catchwords of any surgery nurse. Using the Safety Briefings, the nursing staff receives information that allows us to prepare better for the surgeon’s needs with the goal of reducing unnecessary delays. From a nursing standpoint, we are now proactive rather than reactive to the surgeon’s request and progress of the procedure. “Not only are we sharing information about the patient and the procedure, but also the team members are communicating better among themselves. This is a good thing!” — Helen Burney, RN, and Lori Tokeshi, RN |

Toward Continued Safety Improvement

The Preoperative Safety Briefing has become the safety standard norm in the KP Anaheim Medical Center operating suites and will become the norm in our contract hospital operating rooms throughout the OCSA. The project has transitioned from pilot mode to process improvement mode. The goal is to add additional components to the Preoperative Safety Briefing to continue to build the safety culture in the perioperative setting. For example, the team is currently developing and implementing a Postoperative Debriefing and determining how to strengthen briefings at handoffs and breaks. The Regional Coordinating Chief of Anesthesia continues to work with the Chiefs of Anesthesia, Perioperative Department Administrators, and Joint Anesthesia Management Committee (JAMCO) to support local implementation throughout the region.

Both the specific implementation of a Preoperative Safety Briefing and the general concept of using Human Factors principles to improve patient safety are highly transferable. Within KP, the Physician Champion, Dr James DeFontes, MD, who is also the Regional Coordinating Chief of Anesthesia, has formally presented the Preoperative Safety Briefing concept at the Perioperative Summit for KP Southern California, the Regional Anesthesia Symposium, the Regional Anesthesia Chiefs of Service Meeting, the Perioperative Departmental Administrators Meeting, and the Anesthesia Departmental Administrators Meeting. Through his discussions with JAMCO and the Chiefs of Anesthesia, an SAQ was administered throughout the KP Southern California Region. On the basis of these results, the Chiefs of Anesthesia and JAMCO supported the recommendation to work collaboratively on opportunities for safety improvements at their local sites and agreed to conduct another survey within a year after improvements were made.

To date, the concept of the Team Briefing has been institutionalized regionally as part of the Procedural Sedation Policy in the KP Medical Care Program, Southern California Region, Policies & Procedure Manual (P&P#: 03-167-01). Similarly, Dr Mark Gow, MD, who is also the KP Orange County Director of Patient Safety, has formally presented to the medical staff at Panorama City and will continue to share successful practices with his colleagues in other service areas. Application of the Preoperative Safety Briefing and Human Factors principles are expected in other perioperative settings in other service areas across the region.

The Preoperative Safety Briefing concept has been applied to other services within the OCSA, such as the Departments of Labor and Delivery and of Radiology, with support from the quality management coordinators. The briefing concept is also part of the Regional Labor Management Initiative, because it is one of the annual goals for JAMCO this year.

Interest has also been expressed from outside KP; inquiries have been received from Harvard University, the University of Michigan, and other health care institutions. Dr Gow and the Perioperative Department Administrator are working with our contract hospitals and other private hospitals, such as the City of Hope, to share this tool with their peers in the community. The project team is also committed to spreading these ideas and practices to other KP Regions.

Conclusions

A healthy team environment serves as the foundation for a conducive environment for change. In OCSA, the net effect of this project has been to transition the operating suite culture away from one of individual advocacy to one of an integrated team mentality that mitigates risks to patients, attains optimal operational efficiency, and empowers all participants to leverage improvements beyond patient safety.

Acknowledgments

Michael W Leonard, MD, Anesthesia, KP Colorado Franklin Medical Center; Suzanne M Graham, RN, PhD, KP California Regions Patient Safety Practice Leader; and Doug Bonacum, MBA, Vice President, Safety Management, provided training. Mark Alan Monroe, RN, KP National Environmental Health and Safety Department, provided statistical analysis.

From the University of Texas, J Bryan Sexton, PhD, assisted with data analysis; and William R Taggart, Human Factors Research Project, assisted with training.

Biographies

James DeFontes, MD, serves as the Physician Director of Surgical Services in the Orange County, CA MSA and as the Regional Coordinating Chief of Anesthesia for SCPMG. He is an Anesthesiologist with a Surgical Critical Care Fellowship. He has been with KP since 1984. E-mail: james.defontes@kp.org.

Stephanie Surbida, MPH, serves as a Project Manager to Business Administrator—Finance, Systems, & Consulting for SCPMG. She joined KP in 2001 as an Administrative Fellow. E-mail: stephanie.k.surbida@kp.org.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in AmericaKohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academic Press; 2000. Available from: www.nap.edu/openbook/0309068371/html/ (accessed March 18, 2004) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994 Dec 21;272(23):1851–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Accredited organizations Hospitals. Sentinel event statistics. Jan 29, 2004. Available from: www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/hospitals/sentinel+events/sentinel+event+statistics.htm (accessed March 17, 2004)

- 4.Shortell SM, Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, et al. The performance of intensive care units: does good management make a difference? Med Care. 1994 May;32(5):508–25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young GJ, Charns MP, Daley J, Forbes MG, Henderson W, Khuri SF. Best practices for managing surgical services: the role of coordination. Health Care Manage Rev. 1997 Fall;22(4):72–81. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199710000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young GJ, Charns MP, Desai K, et al. Patterns of coordination and clinical outcomes: a study of surgical services. Health Serv Res. 1998 Dec;33(5 Pt 1):1211–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Grillo SP. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) guidelines for administration. [Houston (TX)]: University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice; 2003. Technical report 03-02. Available from: www.uth.tmc.edu/schools/med/imed/patient_safety/SAQ%20Users%20Manual%200104.doc (accessed March 17, 2004) [Google Scholar]

- 8.University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice . Safety attitudes questionnaire (OR version) [Houston (TX)]: University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice; 2002. [Google Scholar]