Abstract

Aim

To refine and psychometrically test the Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care questionnaire. Background. Inadequate transition to adult care for adolescents with special health care needs has been associated with greater risk of treatment non-adherence, lack of medical follow-up, increased morbidity and mortality. Presently there are no well-validated measures assessing adolescents’ readiness to transition from paediatric to adult medical care.

Design

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Methods

The Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care questionnaire was refined to improve the instrument’s methodological soundness. A literature review informed the revisions. A convenience sample of 200 adolescents, 12–19 years, was recruited from four outpatient clinics at a paediatric hospital in Western Canada between April – June 2012. Construct validity was evaluated by Exploratory Factory Analysis; concurrent validity was assessed using the Psychosocial Maturity Index. Internal consistency was evaluated by computing Cronbach’s alpha estimates.

Results

Factor analysis of the knowledge items identified a 14-item unidimensional scale. Knowledge and behaviour sub-scale scores increased with age, with a stronger relationship between knowledge and age. Psychosocial maturity correlated with both sub-scale scores, but had a stronger association with behaviour. Psychosocial maturity and age had a weak but significant correlation suggesting age is a loose proxy for maturity. Only 27% of 17-year-olds, but 62% 18-year-olds, scored above the behaviour cut-off for transition readiness.

Conclusion

The Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care questionnaire is a psychometrically sound measure that has potential to be used as a readiness assessment tool in both clinical practice and research.

Keywords: adolescent health, chronic illness, factor analysis, instrument development, psychosocial nursing

INTRODUCTION

Significant medical advances and improvements to health care in recent decades have led to increases in quality of life and life expectancy of children with chronic medical conditions (Viner 2008). As a result, more than 90% of children with special health care needs (SHCN) now survive to adulthood and require transitional services (Betz & Telfair 2007). During the health care transition period, youth are at risk of being lost between paediatric and adult services and at increased risk of withdrawing from health care services (Singh 2009). A study on the prevalence of successful transition from paediatric to adult cardiac health care found only 47% of paediatric cardiac patients successfully transferred to adult cardiac care (Reid et al. 2004). Similar findings from a study of transition care of young adults with type 1 diabetes indicate a health care dropout rate of 48% between paediatric and adult services, which the researchers suggest could be a conservative estimate of the problem (Scott et al. 2005). Both of these Canadian studies report transition to adult care usually occurs before patients reach 18 years of age. High rates of unsuccessful transition are a serious concern for youth with SCHN as inadequate transition has been associated with greater risk of treatment non-compliance, lack of medical follow-up and increased morbidity and mortality (Viner 2008).

The transition literature recognizes the need to improve transition from paediatric to adult medical services for adolescents with SHCN generally and in several health care sub-specialties. The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM) has outlined fundamental principles of transition, including: services that are appropriate for chronological age and developmental attainment, which address common concerns of youth, increase the patient’s autonomy and personal responsibility and promote self-reliance (Rosen et al. 2003). There is limited information regarding how to determine when adolescents are adequately prepared and ready to successfully transition to adult medical care. Current evidence suggests youth with SHCN continue to confront many difficulties at the time of transition (Tuchman et al. 2008).

Nursing has a key role in educating and facilitating youth and their families through the transition period, as well as evaluating the overall process (Hauser & Dorn 1999, Visentin et al. 2006). The construct of transition has been inextricably linked to nursing theory, as it addresses changes due to health-illness events (Chick & Meleis 1986). The middle-range transition theory by Meleis and colleagues (2000) identifies transitions as a vital time for health care professionals to facilitate positive health outcomes by providing appropriate therapeutics to meet patients’ needs. Focusing on both the process and outcomes enables clinicians, especially nurses, to assess what stage of transition a person is in and to use interventions and strategies that address the individual’s current needs (Meleis & Trangenstein 1994, Meleis et al. 2000). Assessing patient readiness for transition is regarded as an essential best practice (Fair et al. 2010) and readiness assessment measures are needed to evaluate youths’ level of preparedness. There is a need for psychometrically sound and reliable instruments that assess adolescents’ transition readiness. Such instruments would improve transitional care services by enabling clinicians to use specific strategies and interventions that target adolescents’ knowledge and/or skill deficits to better prepare patients for transition to adult care.

BACKGROUND

Developmentally appropriate care is a fundamental principle of transition services in policies by SAHM (Blum et al. 1993, Rosen et al. 2003), American Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Physicians – American Society of Internal Medicine (2002) and the Canadian Paediatric Society (2011). The ON Taking Responsibility for Adolescent/Adult Care (ON TRAC) transition model was developed from an extensive consultative process involving a series of focus groups with more than a dozen clinicians (physicians, nurses, dieticians and other health care professionals) from specialty clinics in a Canadian tertiary children’s hospital in the late 1990s. The objective of the ON TRAC model was to help develop a transition planning program for the large number of adolescents who transfer to adult care from the children’s hospital each year (Paone et al. 2006). The ON TRAC framework is based on a conceptual model of self-management and transition theory. It uses stages of normal adolescent development and is divided into three age-specific transition stages: early (10–12 years), middle (13–15 years) and late (16–18 years) (Paone et al. 2006). This model established specific indicators and strategies for each developmental stage to assist adolescents in acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills to smoothly progress towards independently managing their health care (Paone et al. 2006). ON TRAC accentuates a holistic approach to transition that addresses six domains of transition: 1) self-advocacy and self-esteem; 2) independent/self-management health care behaviours; 3) sexual health; 4) social supports; 5) educational, vocational and financial planning; and 6) health and lifestyle (Paone et al. 2006). In a review of transition programs for youth with SHCN in Canada, the ON TRAC model was found to meet all nine of the Canadian Pediatric Society and SAHM recommendations for best practice for transition care (Grant & Pan 2011). The ON TRAC framework has greatly influenced transition services, as many of its elements including the Am I On TRAC for Adult Care (ON TRAC) questionnaire have been incorporated and adapted by transition programs in North America and the United Kingdom (Royal College of Nursing 2004, Grant & Pan 2011).

Clinicians have explicitly acknowledged the importance of evaluating adolescents’ readiness for transition by assessing their level of knowledge, skills, responsibility and independence (Fair et al. 2010). Researchers and clinicians have explored the concept of transition readiness and individual transition programs have developed assessment tools and checklists that include readiness measures (Betz 2004, Ledlie 2007, Rapley & Davidson 2010). However, most transition readiness measures are condition or location specific and have not been validated for use as diagnostic instruments to assess and determine preparedness to successfully transfer to adult care (Betz 2004, Rapely & Davidson 2010, Sawicki et al. 2011).

An extensive search of the literature found only three other published measures specifically developed for assessing transition readiness in youth with SHCN and one tool for identifying disease related knowledge deficits (Benchimol et al. 2011) and each have limitations. A 24-item Readiness Questionnaire for Cystic Fibrosis (CF) patients consisting of knowledge and behaviour items was developed and validated by Capelli et al. (1989). However, it is a disease specific measure only appropriate for youth with cystic fibrosis. Sawicki et al. (2011) developed the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) with older adolescents (16–26 years). This 29-item instrument evaluates self-care management and self-advocacy skills of adolescents with various SHCN preparing for transition. Sawicki et al. (2011) used the stages of change model as the framework; they propose the instrument can identify adolescents’ developmental stage of readiness for transition. A psychometric evaluation of the TRAQ in a younger Canadian adolescent population was unable to reproduce the measure’s factor structure and raises questions about whether the TRAQ is a suitable measure to evaluate readiness among younger adolescents (Moynihan et al. 2013). Both the Readiness Questionnaire for CF and the TRAQ are predominantly medically focused and do not include items about normative adolescent risk behaviours that may complicate the health of youth with SHCN. The Self-Management Skills Assessment Guide, developed for a Canadian children’s hospital, consists of youth and parent-rated questionnaires that assess medical self-management and readiness to transition among adolescents (Williams et al. 2011). Influenced by the ON TRAC model (Williams et al. 2011) this tool consists of 21 items focused on skills associated with medical self-management and advocacy and includes double-barreled and problematic items from the original ON TRAC questionnaire. The preliminary report of the Self-Management Skills Assessment Guide had a small sample and did not evaluate the measures’ internal structure. Additionally, most of these measures have been evaluated only as part of their original development and further validation of these assessment tools are critically needed.

A holistic approach to preparation and evaluation of readiness for transition must address more than adolescents’ condition-related knowledge and skills and should include psychosocial and vocational components (Viner 2008). There continues to be a need for a valid and reliable measure of transition readiness (Betz 2004, Betz & Telfair 2007, Pai & Schwartz 2011) that uses a holistic perspective to determine adolescents’ physical, medical and social transition readiness. The original ON TRAC questionnaire, developed to holistically assess youths’ transition readiness, has been adapted and used in clinical settings for more than a decade. Content validity of the original questionnaire was performed with expert clinicians during its development, but its psychometric properties were never evaluated. The goal of revising the ON TRAC questionnaire is to provide a methodologically sound, clinically relevant, valid and reliable readiness assessment measure.

THE STUDY

Aims

The purpose of the study was to revise and test the psychometric properties of the Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care (ON TRAC) questionnaire, an instrument designed to assess youths’ capabilities in performing life skills required to actively participate in their health care and function independently as adults. A descriptive correlational cross-sectional study was conducted in two phases: (1) revision of the instrument; and (2) psychometric evaluation including association with relevant measures.

Methodology

Phase one: instrument revision

The original ON TRAC questionnaire consisted of 23 Likert-type items, using a five-point response scale (‘I’m there - got this done’ to ‘No way!’), which assessed youths’ capabilities of performing life skills required to actively participate in their health care. Instrument revision was part of a renewed effort to improve transition programs at the paediatric hospital where the ON TRAC model was created. A literature review of 40 transition programs globally focused on clinical pathways, transition checklists and key transition issues resulted in a comprehensive list of transition indicators. These indicators were grouped into the six ON TRAC transition domains. The revised ON TRAC questionnaire includes at least one item for each of the transition domains. Specifically, the objective of the revision was to construct a methodologically sound and clinically relevant questionnaire. This involved reviewing the original questionnaire to identify problematic items and modifying items to ensure they were clearly worded, not double-barreled, written at an appropriate reading level and addressed the knowledge, skills and behaviours identified by the transition indicators as essential for successful transition. For example the double-barreled item ‘I have a family doctor I like and will continue to see as an adult’ became two separate items ‘I have a family doctor’ and ‘I visit my family doctor when I need to (For example: to have check-ups, get birth control, or if I have the flu)’. Items were divided into two types of questions, knowledge or behaviour, which used different response scales. Response options were changed to standard response scales better suited to quantitative analysis.

The revised ON TRAC questionnaire is comprised of 26 items, phrased as either knowledge or behaviour based statements. The knowledge statements, which form the knowledge scale, use a four-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and purposefully do not include a neutral response option to avoid the risk of response set bias. The behaviour statements, grouped as an index, employ a five-point ordinal scale (never to always) and ask youth to report how frequently they engage in particular health related behaviours. The revised questionnaire has a Flesch-Kincaid reading level of 5.2, which is appropriate for youth 12 years and older.

Phase two: psychometric evaluation including association with other variables

Psychometric evaluation of the revised ON TRAC questionnaire included an assessment of the knowledge scale’s factor structure through Exploratory Factory Analysis (EFA). Its internal consistency reliability was estimated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

The TRAQ (Sawicki et al. 2011) was originally included to test convergent validity. However, our results were unable to reproduce the original TRAQ factor structure with this younger sample (Moynihan et al. 2013). Consequently, it could not be used for convergent validity. Concurrent validity was assessed using two subscales of the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (PMI), participant age, years with condition and ON TRAC stage.

Sample/Participants

Two hundred youth were recruited from a large paediatric hospital in Western Canada through convenience sampling from April to June 2012. Participants attended one of four outpatient clinics (diabetes, cardiology, gastroenterology, neurology) that provide care for adolescents who will need to transition to adult health care services. Inclusion criteria for the study were: 1) age 12–19 years, 2) currently outpatient at one of four clinics, 3) having a SHCN that will require transitioning to an adult health care clinic, 4) diagnosed for at least six months. Exclusion criteria: 1) youth with developmental delay, because this is identified in the literature as a major impediment to the transition process (Reiss et al. 2005, Sawicki et al. 2011); and 2) non-English speakers, because the study instruments were only available in English. It was estimated that approximately 20 to 30 participants in each age category and a total sample of 200 participants, the minimum sample size needed to perform factor analysis, was required to meet the study objectives (Floyd & Widaman 1995).

Instruments

Demographic data

Data on gender, age, years with condition and outpatient clinic were collected.

Revised Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care Questionnaire

The revised 26-item ON TRAC questionnaire was conceptualized as a combination of knowledge, skills and behaviours, developed to have two independent scores: a knowledge scale and behaviour index. The 17-item knowledge scale asks adolescents to rate their level of knowledge or ability to perform tasks on a four-point Likert-type scale related to both their condition and more general medical self-care. The knowledge score is summed, with higher scores indicating youth are more knowledgeable about their condition. The behaviour index is composed of nine items that were not conceptualized as theoretically connected elements, but important individual behaviours. These items assess frequency, using five-point ordinal response options, that youth engage in behaviours which are conceptually related to the developmental model of transition, such as communicating with health care providers and participating in activities to stay healthy. However, since many different elements can motivate individuals to adopt different behaviours (friends, family, living situation, socioeconomic status etc.), it was determined these items do not have a latent or manifest construct and would not form a scale. Instead, an index that measures consistent patterns of behaviour was established, with the items hypothesized as a skill set that youth must achieve at a minimum level to be considered ready to transition to adult care and self-manage their condition. The behaviour index has both a raw score and a cut-off score, with higher scores indicating youth are more frequently engaging in health care related behaviours. Since there are no empirically derived cut-off scores for the minimal level of behaviours needed for successful transition, the investigators created theorized cut-offs for each item, based on clinical experience and consultation with other nurses, as a minimum frequency at which youth need to practice the behaviours to be considered ready for adult care. Responses below the designated cut-off received a zero and responses at or above the cut-off were counted as one. Item 19 (I feel my family cares about me) was excluded from the index, because it did not assess a behaviour. The highest achievable cut-off score was eight and a score of seven was required for adolescents to meet the minimal level considered ready to transition.

Psychosocial Maturity Inventory

Two sub-scales (self-reliance and work orientation) of the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (PMI) were used to assess concurrent validity of the revised ON TRAC questionnaire. Greenberger and Sørensen (1974) proposed psychosocial maturity is an integrative concept comprised of three general capacities that societies expect mature individuals to possess: the capacity to function on their own, the capacity to interact adequately with others and the capacity to contribute to social cohesion. The 20-items of the self-reliance and work orientation subscales are especially relevant to assessing adolescents’ readiness for transition. The PMI is a validated tool that documents the course of psychosocial maturity over the school-age years and is appropriate for comparing groups of individuals (Greenberger et al. 1975).

Ethical Considerations

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Review Boards of the researchers’ university and the participating hospital. Participants were provided with a study information letter outlining the study purpose, data collection procedure, potential risks and benefits of participation and how the data will be used. Data collection was anonymous. Participants were informed completing and returning the study package indicated they had consented to be part of the study. Participants were made aware involvement in the study was voluntary, that they could choose not to answer any question or stop at any time without incurring any penalties or deprivation of services.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armock, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to investigate the factor structure of the ON TRAC knowledge scale using principal component analysis (PCA). The following criteria were used to determine the number of factors to retain: parallel analysis (Zwick & Velicer 1986), visual inspection of Scree plots (Floyd & Widaman 1995) and item loadings > 0.4 on any one factor (Floyd & Widaman 1995). Parallel analyses were conducted using an online parallel analysis engine (Patil et al. 2007) that generates a hundred random correlation matrices and provides the 95th percentile eigenvalues, which were compared to the corresponding eigenvalue from the study dataset. Internal consistency reliability of the knowledge scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Pearson’s product correlations were used to examine the relationships between PMI scores, age, ON TRAC stage, knowledge scale scores and behaviour index scores. The data was analyzed using casewise deletion of missing data, which resulted in a small loss of subjects due to incomplete response data and varied by instrument.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 215 youth were approached to participate and 201 youth completed the study package, for a 93.5% participation rate. One participant did not meet the inclusion criteria and their data was excluded from the analysis (final N=200). Youth ranged in age from 12–19, with a mean age of 15.33 (SD=1.88). Fifty-seven percent were male and participants were distributed across the clinics, with 36% from diabetes, 27% cardiology, 27% gastroenterology and 10% neurology. Table 1 describes the sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Youth Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | n | % | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 115 | 57.5 | ||

| Female | 85 | 42.5 | ||

| Clinic | ||||

| Diabetes | 72 | 36 | ||

| Cardiology | 54 | 27 | ||

| Gastroenterology | 54 | 27 | ||

| Neurology | 20 | 10 | ||

| ON TRAC Stage | ||||

| Early (12 years) | 19 | 9.5 | ||

| Middle (13–15 years) | 82 | 41 | ||

| Late (16–19 years) | 99 | 49.5 | ||

| Age | 15.33 (1.88) | 12–19 | ||

| Years with condition | 8.03 (5.46) | 0.5–19 | ||

N = 200

Construct validity

EFA analyses were performed to estimate the number of components in the 17-item ON TRAC knowledge scale. We hypothesized the scale could be composed of two correlated components: health condition specific knowledge and general health self-management items. An oblique rotation and non-rotated PCA were performed. The rotation did not provide clear and distinct components and component correlations did not support the use of an oblique rotation. Consequently, the non-rotated PCA was determined to be optimal and its results are reported. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.84, indicating suitability for factor analysis and Bartlett’s test was significant (χ2 = 822.54, d.f. = 136, p < 0.001). A visual inspection of the Scree plot showed a clear inflexion after the first component and strongly suggested a single component solution. Results from parallel analysis also supported a one component solution. The first component accounted for 30.3% of the explained variance, had item loadings ranging from 0.37–0.67, with 16 items loading > 0.4 (Table 2). Item 14 – My family supports me in managing my health – was the only item that loaded < 0.4 on the first component. Although item 2 (I have a family doctor) and item 3 (I visit my family doctor when I need to) had loadings > 0.4 it was determined they were not part of the latent construct the knowledge scale is trying to measure, as they do not assess either adolescents’ knowledge or capabilities.

Table 2.

Component Loadings, Eigenvalues and Percentage of Variance for Principal Component Analysis of the 17-item ON TRAC Knowledge Scale (n=179)

| ON TRAC Knowledge Item | Component

|

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 1. I can describe my health condition to others | .55 |

| 2. I have a family doctor | .45 |

| 3. I visit my family doctor when I need to (For example: to have check-ups, get birth control, or if I have the flu) | .44 |

| 4. I know what my long-term health problems might be | .61 |

| 5. I know what patient confidentiality means | .61 |

| 6. I understand the risks and benefits of health care treatments before consenting to those treatments | .65 |

| 7. I know how to get my medical records | .63 |

| 8. I know the names of my medications | .67 |

| 9. I know what each of my medications are for | .65 |

| 10. I know the side effects of the medications I take | .59 |

| 11. I can get to my clinic appointments on my own | .48 |

| 12. I know how my condition might affect my sexual health | .57 |

| 13. I know how to prevent sexual health risks such as pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | .56 |

| 14. My family supports me in managing my health | .37 |

| 15. I know how my health condition might limit my career choices | .48 |

| 16. I know how my health condition affects my physical activities | .46 |

| 17. I know how alcohol, drugs and tobacco can affect my medications | .47 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.14 |

| Percentage of variance | 30.25% |

Note. Component loadings > .40 are in boldface. Only components supported by the parallel analysis are shown.

A non-rotated PCA was conducted on the remaining 14-item knowledge items. The KMO=.85 and Barlett’s=χ2 (91) = 676.78, p < 0.001 verified the sampling adequacy for analysis. Both the Scree test and parallel analysis signified a one component solution was optimal. Component one accounted for 33.66% of the explained variance. Item loadings ranged from 0.44–0.66. Table 3 summarizes the PCA results of the 14-item ON TRAC knowledge scale. The 14-item scale provided the optimal solution and fits best with the theoretical development of the revised ON TRAC questionnaire.

Table 3.

Component Loadings, Eigenvalues and Percentage of Variance for Principal Component Analysis with No Rotation of the 14-item ON TRAC Knowledge Scale (n=180)

| ON TRAC item | Component

|

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 1. I can describe my health condition to others | .56 |

| 4. I know what my long-term health problems might be | .60 |

| 5. I know what patient confidentiality means | .62 |

| 6. I understand the risks and benefits of health care treatments before consenting to those treatments | .66 |

| 7. I know how to get my medical records | .65 |

| 8. I know the names of my medications | .66 |

| 9. I know what each of my medications are for | .65 |

| 10. I know the side effects of the medications I take | .59 |

| 11. I can get to my clinic appointments on my own | .50 |

| 12. I know how my condition might affect my sexual health | .60 |

| 13. I know how to prevent sexual health risks such as pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | .57 |

| 15. I know how my health condition might limit my career choices | .50 |

| 16. I know how my health condition affects my physical activities | .44 |

| 17. I know how alcohol, drugs and tobacco can affect my medications | .46 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.71 |

| Percentage of variance | 33.66 |

Note. Component loadings > .40 are in boldface. Items 2, 3 and 14 removed. Only components supported by the parallel analysis are shown.

Item analysis and reliability

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the 14-item unidimensional knowledge scale was 0.84, at the upper end of the range of acceptable values for alpha (Tavakol & Dennick 2011), with all scale items contributing and demonstrating adequate internal consistency.

Association with other variables

We examined the relationships between the three ON TRAC scores (knowledge, behaviour and behaviour cut-off) with age, psychosocial maturity as measured by the PMI, ON TRAC stage and patient’s number of years with their condition (Table 4). The correlation between psychosocial maturity and age was significant but weak. Age had a significant moderate relationship with the knowledge scale and both behaviour measures. The PMI also had significant moderate correlations with the ON TRAC scores. Age had a stronger relationship with the knowledge score, but psychosocial maturity had a stronger relationship with behaviour scores. The strongest relationships were found between the ON TRAC scores themselves, with a correlation between the knowledge scale and the behaviour index overall score of 0.53 and with the cut-off score of 0.49. There was no correlation between any ON TRAC scores and the number of years adolescents had their condition.

Table 4.

Correlations between Age, PMI, ON TRAC Knowledge Score, ON TRAC Behaviour Index Raw Score, ON TRAC Behaviour Index Cut-off Score, ON TRAC Stage and Years with Condition

| Age | PMI | Knowledge Scale | Behaviour Index Raw Score | Behaviour Index Cut-off Score | ON TRAC Stage | Years with Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Age | 1 | ||||||

| PMI | .16* | 1 | |||||

| Knowledge Scale | .43** | .30** | 1 | ||||

| Behaviour Index Raw Score | .30** | .39** | .53** | 1 | |||

| Behaviour Index Cut-off Score | .34** | .39** | .49** | .91** | 1 | ||

| ON TRAC Stage | .89** | .12 | .41** | .25** | .29** | 1 | |

| Years with Condition | .35** | .14 | .13 | .05 | .06 | .26** | 1 |

p < .05,

p < .01

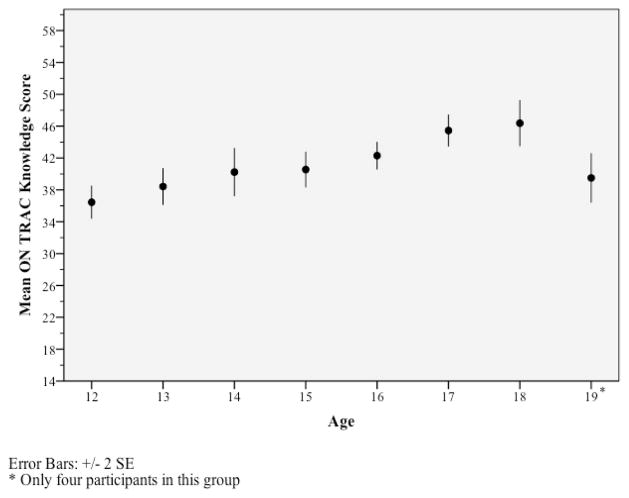

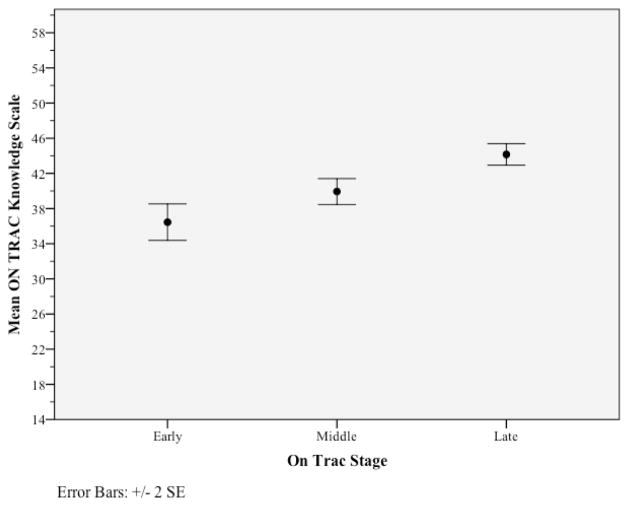

To illustrate these relationships the mean, minimum and maximum knowledge scores differed based on participant age, with scores slightly increasing with age. Twelve year olds had the lowest mean (36.44, SD 4.41) and maximum scores and 18 year olds had the highest mean (46.37, SD 6.33) and second highest maximum score. A deviation from this general trend was the 19 year olds who had the third lowest mean (39.50, SD 3.11) and second lowest maximum score. However, we anticipated 19 year olds might have lower scores, since they were still patients at a paediatric hospital. It is hospital policy to transfer patients to adult care at 18 and reasonable to expect 19-year-old participants might have delayed development and lack the knowledge and/or skills required for adult medical care, which is why they remained at the paediatric clinics. Knowledge scores between the different clinics were comparable, with means ranging from 40.7 for cardiology to 43.6 for diabetes. Figures 1 and 2 display the mean ON TRAC knowledge scores based on age and ON TRAC stage.

Figure 1.

Mean ON TRAC Knowledge Scores by Age

Figure 2.

Mean ON TRAC Knowledge Scores by ON TRAC Stage

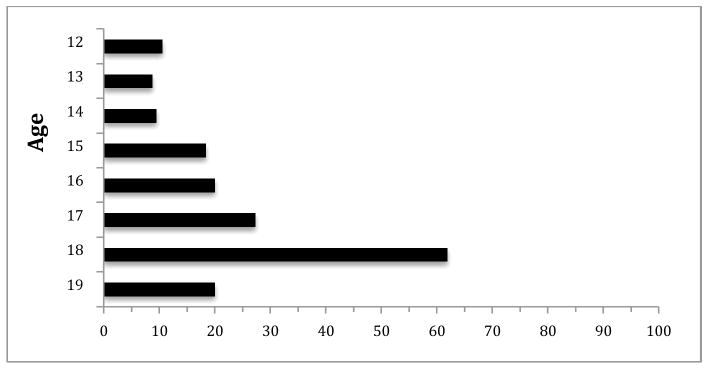

The behaviour index overall score means increased slightly with age, ranging from 25.8–31.1. Again, 19-year-old participants did not fit the general pattern. Minimum scores ranged from 18–21 and maximum scores ranged from 34–40. The largest increase in maximum score occurred between 15 and 16 year olds. The percentage of adolescents that met the theorized cutoff score of seven and satisfied the minimal requirements for successful transition increased steadily after 14 years of age. Twelve to 14 year olds had similar percentages of acceptable cutoff scores; at 15 years the percentage nearly doubled and continued to increase until 18. The greatest increase in number of youth deemed ready for transition occurred between 17 and 18, with 27% of 17 year olds versus 62% of 18 year olds obtaining cut-off scores of seven or higher. Figure 3 displays the percentage of youth who meet the behaviour cut-off score at each age.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Youth that Met the Behaviour Index Cut-off Score Grouped by Age

DISCUSSION

The 25-item revised Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care questionnaire showed evidence of acceptable construct validity and internal consistency of its subscales. These measures are embedded in theoretical practice and capture adolescents’ knowledge, skills and behaviour related to SHCN and general health care self-management. Factor analysis of the 14-item knowledge scale supports a unidimensional construct. Items 2 (I have a family doctor) and 14 (My family supports me in managing my health) did not conceptually fit with the knowledge scale, but are pertinent to transition readiness. Having a family doctor and a supportive family can directly affect adolescents’ abilities to manage their health and are important issues for clinicians to discuss with youth. Consequently, it was decided these items should remain in the questionnaire but would not be included in the knowledge scale score. Item 3 (I visit my family doctor when I need to) was removed from the knowledge scale because it inquires about a behaviour and has been included on the behaviour index. Item 19 (I feel my family cares about me) was removed from the index, because it did not assess a behaviour. Adolescents between 12 to 19 years old from a variety of outpatient clinics had no difficulty completing the questionnaire, which provides evidence that the items are clear and understandable.

Age is the most frequently used criterion for determining when transition from paediatric to adult medical care occurs (Betz 2004). As a primary determinant for transition, age is used to estimate an adolescent’s developmental level and employed as a guide for coordinating transition care (Pai & Ostendorf 2011). The correlations between adolescents’ age, psychosocial maturity, ON TRAC knowledge score and both ON TRAC behaviour scores provide support for its developmental appropriateness in assessing readiness. Age had the strongest relationship with the knowledge scores, but had significant moderate correlations with both knowledge and behaviour scores. Other investigations that have assessed readiness have also identified a significant relationship between age and transition related knowledge (McPherson et al. 2009, Sawicki et al. 2011). Psychosocial maturity had the strongest relationship with the ON TRAC behaviour scores, but also significantly and moderately correlated with the ON TRAC knowledge scores. These results are consistent with earlier research and provide further evidence to support chronological age may not be the best indicator of transition readiness. Studies by Cappelli et al. (1989) and Williams et al. (2011) also determined age was not the most important marker for evaluating readiness for transition. Cappelli et al. (1989) found the results from their readiness questionnaire for adolescents with cystic fibrosis to be a better predictor of transition readiness than age. Williams et al. (2011) reported adolescents’ medical self-management scores were strongly associated with scores of functional independence, but had small and non-significant correlations with age and were closely associated with their independence in other areas. We found a significant but weak correlation between psychosocial maturity and age, which suggests age is a loose proxy for development and maturity and for youth with chronic conditions, age may have a poorer relationship with maturity. Our results suggest there is not a set age at which adolescents consistently perform the behaviours necessary for successful transition; some youth may potentially be ready for adult care at 15, while others may take longer to satisfy the minimum requirements. Together with these other studies, our findings suggest hospitals may need to re-consider having a standard age for determining when transition occurs and look more closely at health and self-management behaviours.

The revised ON TRAC questionnaire is the first transition readiness measure to assess the frequency that youth are engaging in health care related behaviours. Another study examining mastery of health care management found young adults had higher scores in performing health care management behaviours compared with youth (Annuziato et al. 2011), but fewer than half of the young adults reported consistently managing their health care independently, making their own appointments and understanding insurance issues (Annunziato et al. 2011). These findings demonstrate the importance of assessing adolescents’ health care related behaviours, to determine whether they are comprehensively managing their own care before transitioning to the adult system. The behaviour index could facilitate educational interventions to assist youth to consistently engage in health care related behaviours.

Limitations

There are some study limitations to consider. First, all responses were self-report, rather than observations from others and thus may represent an over- or under-estimation of capability and frequency of self-care. Second, although the study involved adolescents from different clinics who had a variety of diagnoses, the clinics were all from one children’s hospital in Western Canada; the study should be replicated elsewhere to offer further evidence of validity and reliability among adolescents. Third, the revised ON TRAC questionnaire is only available in English and translation into other languages should be considered for future studies. Fourth, the PMI does not provide information about expected normative scores based on age; as a result, we were unable to determine if participants’ psychosocial maturity scores were within an acceptable normative range for their age and whether adolescents’ with SHCN mature at a similar rate as adolescents generally. Finally, although the scales measure readiness as conceptualized in the transition literature, further research would be needed to determine whether the readiness scores, especially the behaviour cut-off, actually predict appropriate timing for successful transition to adult medical care.

CONCLUSION

The revised ON TRAC questionnaire has potential application for both clinical practice and research. As a clinical tool, it can be used as a psychometrically sound measure to evaluate youths’ level of preparedness for transition and to measure change in adolescents’ readiness to transition over time. The questionnaire will assist nurses and other clinicians to identify critical areas of knowledge, skills and/or behaviours deficits and address these issues with adolescents and their family prior to transition. Targeted interventions could be developed to ensure youth are sufficiently prepared to meet the expectations of the adult health care system.

The revised ON TRAC questionnaire shows promise for being able to predict successful transition, but we still do no know if this measure of readiness will lead to better transition outcomes or successful navigation of the adult medical system. Longitudinal research should be conducted to test the predictive capacity of the ON TRAC questionnaire scores. Due to improvements to paediatric health care children with SHCN are living to adulthood; we now need to ensure youth have the necessary knowledge and skills to successfully transition to adult medical care and are able to optimize their health as young adults.

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

Why was this research needed?

Current evidence suggests youth with special health care needs continue to confront many difficulties at the time of transition.

There is limited information regarding how to determine when adolescents are adequately prepared and ready to successfully transition to adult medical care.

Psychometrically sound and reliable instruments that assess adolescents’ transition readiness could improve transitional care services by enabling clinicians to develop targeted interventions to better prepare patients for adult care.

What are the key findings?

The revised ON TRAC questionnaire, a measure of adolescents’ knowledge, skills and behaviour related to SHCN and general health care self-management, showed evidence of acceptable construct validity and internal consistency.

The correlation between psychosocial maturity and age was significant but weak, which suggests that age is a loose proxy for development and maturity.

It is important to assess adolescents’ health care related behaviours to determine whether youth are comprehensively managing their own care before transitioning to the adult system.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

The ON TRAC questionnaire should be used as a clinical tool to evaluate youths’ level of preparedness for transition and to measure change in adolescents’ readiness to transition over time.

To determine if ON TRAC questionnaire scores are able to differentiate between individuals who successfully transition and those who do not adolescents should complete the questionnaire throughout the transition process.

Hospitals may need to re-consider having a standard age for determining when transition to adult care occurs and look more closely at health and self-management behaviours.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the clinicians, hospital staff and youth for participating in the study as well as Sarah Dobson for editorial assistance with the final manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the Katharine MacMillan Fund, UBC School of Nursing, and grant #CPP86374 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Melissa MOYNIHAN, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia. Research Assistant, Stigma and Resilience Among Vulnerable Youth Centre.

Elizabeth SAEWYC, Professor, School of Nursing & Division of Adolescent Health and Medicine, University of British Columbia. Director, Stigma and Resilience Among Vulnerable Youth Centre. Senior Scientist, Child Family Research Institute, BC Children’s Hospital.

Sandra WHITEHOUSE, Clinical Associate Professor, Division of Emergency Medicine, University of British Columbia, Department of Pediatrics, Medical Lead, Transition Initiative, BC Children’s Hospital.

Mary PAONE, Nursing lead for transition/clinical Coordinator, BC Children’s Hospital.

Gladys MCPHERSON, Assistant professor, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians & American College of Physicians – American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):1304–1306. Retrieved on March 20, 2010 from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/110/Supplement_3/1304.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato RA, Parkar S, Dugan CA, Barsade S, Arnon R, Tamir M, Iyer K, Kerkar N, Shemesh E. Brief report: Deficits in health care management skills among adolescent and young adult liver transplant recipients transitioning to adult care settings. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(2):155–159. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol EI, Walters TD, Kaufman M, Frost K, Fiedler K, Chinea Z, Zachos M. Assessment of knowledge in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease using a novel transition tool. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 2011;17(5):1131–1137. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz CL. Transition of adolescents with special health care needs: Review and analysis of the literature. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2004;27(3):179–241. doi: 10.1080/01460860490497903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz CL, Telfair J. Health care transitions: An introduction. In: Nehring WM, editor. Promoting health care transitions for adolescents with special health care needs and disabilities. Paul H Brookes Publishing; Baltimore, MD: 2007. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Blum RWM, Garell MD, Hodgman CH, Jorissen TW, Okinow NA, Orr DP, Slap GB. Transition from child-centered to adult-centered systems for adolescents with chronic conditions: a position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14(7):570–576. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needs. 2011 doi: 10.1093/pch/12.9.785. Retrieved on April 10, 2011 from: http://www.cps.ca/english/statements/AM/AH07-01.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cappelli M, MacDonald NE, McGrath PJ. Assessment of readiness to transfer to adult care for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Children’s Health Care. 1989;18(4):218–224. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc1804_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick N, Meleis A. Transitions: A nursing concern. In: Chinn PL, editor. Nursing research methodology. Aspen Publication; Boulder, CO: 1986. pp. 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Fair CD, Sullivan K, Gatto A. Best practices in transitioning youth with HIV: Perspectives of pediatric and adult infectious disease care providers. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2010;15(5):515–527. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.493944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E, Carter B, Gillibrand W. The transition of adolescents with diabetes from the children’s health care service into the adult health care service: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002;11(5):560–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(3):286–299. Retrieved on September 24, 2012 from: http://mres.gmu.edu/pmwiki/uploads/Main/FloydWidaman95.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Grant C, Pan J. A comparison of five transition programmes for youth with chronic illness in Canada. Child: care, health and development. 2011;37(6):815–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Josselson R, Knerr C, Knerr B. The measurement and structure of psychosocial maturity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1975;4(2):127–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01537437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Sørensen AB. Toward a concept of psychosocial maturity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1974;3(4):329–358. doi: 10.1007/BF02214746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser E, Dorn L. Transitioning adolescents with sickle cell disease to adult centered care. Pediatric Nursing. 1999;25(5):479–488. Retrieved on January 15, 2010 from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ehost/detail?sid=a8dd482e-53614f6b935c4a8e6da37cef%40sessionmgr14&vid=1&hid=7&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledlie SW. Methods of assessing transition health care needs. In: Nehring WM, editor. Promoting health care transitions for adolescents with special health care needs and disabilities. Paul H Brookes Publishing; Baltimore, MD: 2007. pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lostein DS, McPherson M, Strickland B, Newacheck PW. Transition planning for youth with special health care needs: Results from the national survey of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1562–1568. doi: 10.1542/peds2004-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Thaniel L, Minniti CP. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: Assessing patient readiness. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2009;52:838–841. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI, Sawyer LM, Im EO, Hilfinger Messias DK, Schumacher K. Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Advances in Nursing Science. 2000;23(1):12–28. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006. Retrieved on September 30, 2010 from: http://journals.lww.com/advancesinnursingscience/Abstract/2000/09000/Experiencing_Transitions__An_Emerging_Middle_Range.6.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI, Trangenstein PA. Facilitating transitions: redefinition of the nursing mission. Nursing Outlook. 1994;42(6):255–259. doi: 10.1016/0029-6554(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan M, Saewyc E, Whitehouse S, Paone M, McPherson G. Evaluation of the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) in a younger adolescent population. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(2):S71–S72. [Google Scholar]

- Pai ALH, Ostendorf HM. Treatment adherence in adolescents and young adults affected by chronic illness during the health care transition from pediatric to adult health care: a literature review. Children’s Health Care. 2011;40(1):16–33. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2011.537934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pai ALH, Schwartz LA. Introduction to the special section: Health care transitions of adolescents and young adults with pediatric chronic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(2):129–133. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil VH, Singh SN, Mishra S, Donavan DT. Parallel Analysis Engine to Aid Determining Number of Factors to Retain [Computer software] 2007 Available from http://ires.ku.edu/~smishra/parallelengine.htm.; Utility developed as part of Patil V. H., Singh S.N., Mishra S. & Donovan D.T. (2008) Efficient Theory Development and Factor Retention Criteria: A Case for Abandoning the ‘Eigenvalue Greater Than One’ Criterion. Journal of Business Research. 61(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC model for transitional care of adolescents. Progress In Transplantation. 2006;16(4):291–302. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600403. Retrieved on April 27, 2010 from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&hid=7&sid=76691f4c-9571-4a21-a81f-64f73df42461%40sessionmgr14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley P, Davidson PM. Enough of the problem: A review of time for health care transition solutions for young adults with a chronic illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(3–4):313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss JG, Gibson RW, Walker LR. Health care transition: Youth, family and provider perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):112–120. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, Sananes R, Ritiva PG, Siu SC, Webb GD. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3):e197–e205. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e197. Retrieved on February 16, 2010 from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/113/3/e197.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DS, Blum RW, Britto M, Sawyer SM, Seigel D. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00208-8. Retrieved on February 16, 2010 from: http://www.adolescenthealth.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Position_Papers&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. Adolescent transition care: guidance for nursing staff. Royal College of Nursing; London, UK: 2004. Retrieved on March 15, 2013 from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assests/pdf-file/0011/78617/002313.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, Demars N, Huang I, Livingood W, Reiss J, Wood D. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ – transition readiness assessment questionnaire. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(2):160–171. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Vallis M, Charette M, Murray A, Latta R. Transition of care: Researching the needs of young adults with type 1 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2005;29(3):203–210. Retrieved on February 16, 2010 from: http://www.diabetes.ca/Files/Scott--Transitionpages203-210.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP. Transition of care from child to adult mental health services: The great divide. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009;22(4):386–390. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2011;2:53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman LK, Slap GB, Britto MT. Transition to adult care: Experiences and expectations of adolescents with a chronic illness. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2008;34(5):557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365.2214.2008.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin K, Koch T, Kralik D. Adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Transition between diabetes services. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15(6):761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM. Transition of care from paediatric to adult services: One part of improved health services for adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2008;93(2):160–163. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.103721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Sherman EMS, Dunseith C, Mah JK, Blackman M, Latter J, Mohamed I, Slick DJ, Thornton N. Measurement of medical self-management and transition readiness among Canadian adolescents with special health care needs. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health. 2011;3(4):527–535. Retrieved on June 15, 2012 from: https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=22999. [Google Scholar]

- Zwick WR, Velicer WF. Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(3):432–442. [Google Scholar]