Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of varying approaches to CDH repair timing on survival and need for ECMO when controlled for anatomic and physiologic disease severity in a large consecutive series of CDH patients.

Summary Background Data

Our publication of 60 consecutive CDH patients in 1999 showed that survival is significantly improved by limiting lung inflation pressures and eliminating hyperventilation.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 268 consecutive CDH patients, combining 208 new patients with the 60 previously reported. Management and ventilator strategy were highly consistent throughout. Varying approaches to surgical timing were applied as the series matured.

Results

Patients with anatomically less-severe left liver-down CDH had significantly increased need for ECMO if repaired in the first 48 hours, while patients with more-severe left liver-up CDH survived at a higher rate when repair was performed before ECMO. Overall survival of 268 patients was 78%. For those without lethal associated anomalies, survival was 88%. Of these, 99% of left liver-down CDH survived, 91% of right CDH survived. and 76% of left liver-up CDH survived.

Conclusions

This study shows that patients with anatomically less severe CDH benefit from delayed surgery while patients with anatomically more severe CDH may benefit from a more aggressive surgical approach. These findings show that patients respond differently across the CDH anatomic severity spectrum, and lay the foundation for the development of risk specific treatment protocols for patients with CDH.

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a common and frequently lethal birth defect that has occupied the hearts and minds of pediatric surgeons, neonatologists, and devastated parents for decades. Currently, the best estimate of overall survival is 67%, as reported by the CDH study group, which is made up of centers interested in this disease and which voluntarily report their results(1). The real survival rate for CDH may be well less than this, but conservatively at least 1 in 3 infants born with CDH do not survive.

Improvement in survival has occurred over the last 2 decades, most likely due to the wide permeation of techniques of gentle ventilatory support for these patients, pioneered by Wung(2), and first reported for CDH in the 1990’s (3–5). These concepts have almost universally been successful in improving outcomes in centers that adopt them. (6–10). Adoption of gentle ventilatory techniques is usually paired with the adoption of delayed repair of the CDH. (3,4,11,12). While the pertinent literature strongly supports the role of gentle ventilation in CDH, the case for survival benefit specifically attributed to delayed repair of CDH is missing, especially as any effect is difficult to separate from the effect of improved ventilatory techniques(12–14). While it is well known that anatomic markers of CDH severity exist with correspondingly different survival rates(15–17), previous reports evaluating the effects of surgical timing on CDH survival have not addressed these differences.

In 1992 we adopted the gentle ventilation strategies of Wung and Stolar(3), and published our first sixty patients in 1999(5). The notable survival rates in that series, 78% overall and 89% in patients without associated lethal anomalies, resulted in the development of both an expanded referral practice to our center. Since our original report we have accrued an additional 208 consecutive patients, now totaling 268.

The gentle ventilation strategies we originally described have remained highly consistent, but over the course of this series we have applied varying approaches to surgical timing. In this study we postulated that patients with more severe CDH face different physiologic challenges from patients with less severe CDH, and might respond differently to varying treatment strategies. We critically review our 19-year experience to see how differences in surgical timing may have affected survival outcomes and need for ECMO across the spectrum of CDH anatomic severity.

Methods

All newborns with Bochdalek CDH, symptomatic in the first 6 hours of life and cared for at the University of Florida and Shands Hospital for Children between September, 1992 and December 31, 2011 were included, regardless of associated anomalies, degree of pulmonary hypoplasia, and medical condition on arrival. Two separate hospital medical record queries were cross-referenced with operative records, autopsy records, a pediatric surgery database, and 2 prenatal evaluation databases to assure that no patients were missed. Patients with Morgagni CDH, diaphragmatic eventration, and patients in whom diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia was delayed more than 48 hours after delivery were not included. This study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Type of Study

A retrospective review was performed. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Florida, and supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute(18). Data collected and used for this analysis include gestational age, birth weight, Apgar at 1 minute, Apgar at 5 minutes, predicted survival (19), date, time, and place of delivery, side of defect, stomach position, liver position, presence of associated anomalies and surgical details including patch. Anatomic findings were reported from direct observation at surgical repair, autopsy, or prenatal imaging if neither was available. Use and type of ECMO, duration of ECMO, and condition at discharge were also collected. Time of CDH repair and of ECMO initiation were collected and analyzed. Total days on ECMO and number of ECMO runs were recorded. Patients who received ECMO prior to repair of CDH were judged to have had “opportunity” for repair if they had pre-ductal saturations above 90% and adequate hemodynamic stability for 16 hours after birth for surgical repair to have been possible, had it been chosen. Those who did not meet these criteria were judged to “not have opportunity” for repair before ECMO. CDH study group predicted survival was retrospectively calculated from http://nicutools.org.

Evaluation and Treatment

Patients referred for prenatal evaluation were counseled optimistically and terminations for isolated CDH did not occur. Delivery was planned between 38 and 39 weeks, with vaginal delivery preferred. EXIT to ECMO was not used. The pediatric surgeon attended the deliveries and prenatally diagnosed patients were intubated immediately. Apgar scores were independently assigned by the neonatal staff. Ventilator strategy, blood gas goals, fluid management, and hemodynamic support have been previously published(5) and did not change appreciably. The attending pediatric surgeon provided management oversight throughout the hospitalization.

Nitric oxide was used as first-line rescue for critical instability (OI > 40) and ECMO was only used for persistent or recurrent critical instability (OI>40), and only after optimization of ventilation and medical support, including use of pressors, steroids, and other vasoactive medications as deemed indicated.

Management strategies regarding timing of CDH repair and management of repair decisions related to ECMO evolved through the 19-year experience. As no convincing data existed showing superiority of any surgical timing strategy(20), a variety of timing strategies were employed over the series and provide significant variation for analysis. Treatment difficulties and survival trends appreciated during the series resulted in ongoing evolution of the repair paradigm. Delay of repair beyond 48 hours was the prevalent strategy, but repairs prior to this did occur, sometimes for specific clinical reasons, and sometimes not. Delay of repair in more severe patients resulted in the majority of those patients arriving to ECMO unrepaired, and several such patients we thought should have survived suffered poor outcomes. To avoid the situation of arriving to ECMO unrepaired, we slowly evolved a more aggressive approach to surgical repair in patients we deemed likely to need ECMO. This conclusion was based on prenatal and post-natal data such as LHR, liver position, and blood gas trends. This analysis was designed to define which repair strategies worked best and for which patients.

For patients who arrived to ECMO unrepaired strategies for repair also evolved. Earlier in the series these patients were generally repaired on ECMO, whereas later in the course attempts were made to stratify those patients as eventually weanable from ECMO or not, judged on a clinical estimate of pulmonary parenchymal volume. Patients judged to have “more” lung parenchyma based on clinical and radiographic criteria were treated with the goal of repair following ECMO, whereas patients judged to have critically small lungs were repaired on ECMO, usually early in the course. Surgical technique and hemostasis were exacting, and Amicar was not used routinely.

Results were analyzed for the 240 patients without lethal associated anomalies in aggregate, and stratified by the anatomic cohorts of left liver-down, right, and left liver-up CDH. Survival to discharge and need for ECMO were compared by univariate and multivariate techniques, looking specifically at risk for ECMO related to surgical timing, and survival based on the order relationship of surgical repair to ECMO. Patients who did not have “opportunity for repair” before ECMO were not included in the comparison of survival outcomes related to order of surgical repair and ECMO. Prenatal evaluation data such as LHR was available for the majority of patients, but were missing in enough that these data were excluded from this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise specifically noted, comparison of continuous cohorted variables was performed using 2-tailed T-test, and exact analysis of proportion was performed using Fisher’s Exact Test. Quantitative variables are expressed as the mean +/− standard deviation. All tests were 2-sided and the threshold for statistical significance was set to p<0.05. We used logistic regression to evaluate the effect of ECMO first vs. Surgery first on survival (yes or no) when controlling for CDH Study Group predicted survival(19). We also used multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the effect of timing of surgery (within 48 hours vs. after 48 hours) on the need for ECMO when controlling for predicted survival. The distributions of survival time were estimated using the adjusted Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess prognostic and treatment factors for overall survival and to compute hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. The ability to do multivariate analysis of anatomic sub-group outcomes as it related to surgical decisions was limited by the low number of events (deaths) in the anatomic subgroups. Only a single added variable was statistically appropriate for multivariate analysis, and predicted survival as calculated from the CDH study group, which fit the model well (Table 2), was used. Analyses were performed with R statistical software (Vienna, Austria; version 2.15.0).

Table 2.

Anatomic Sub-groups (Lethal associated anomalies excluded)

N=240

| Left liver down (n=97) |

Right (n=42) |

Left liver up (n=101) |

p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gestational age mean±SD; median [IQR] |

37.4±2.1; 38 [37, 39] |

36.9±2.8; 37 [36, 38] |

37.2±2.1; 38 [36, 38] |

p=0.321* |

|

Birth weight mean±SD; median [IQR] |

3022±582; 3117 [2650, 3440] |

2926±550; 2984 [2563, 3210] |

2769±680; 2840 [2400, 3175] |

p=.0169* |

|

Apgar-1 mean±SD; median [IQR] |

5.26±2.27; 5 [4, 7] |

3.90±2.15; 4 [2, 6] |

3.52±2.24; 3 [1, 5] |

p<.0001* |

|

Apgar-5 mean±SD; median [IQR] |

7.60±1.59; 8 [7, 9] |

6.37±2.07; 6 [5, 8] |

5.69±2.18; 6 [4, 7] |

p<.0001* |

|

CDH SG Pred. Surv. mean±SD; median [IQR] |

73.8%±16.4%; 79% [66%, 86%] |

61.7%±18.8%; 64% [50%, 78%] |

52.6%±25.0%; 54% [38%, 75%] |

p<.0001** |

| Survival (n, %) |

96 (99.0%) |

38 (90.5%) |

76 (75.2%) |

p<.0001*** |

IQR=Interquartile range (the 25th and 75th percentiles)

p-values are the results of

ANOVA, with pairwise comparisons adjusted using Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons;

Kruskal-Wallis test, with pairwise comparisons adjusted using Bonferroni’s method for multiple comparisons;

chi-square test, with pairwise comparisons adjusted using Bonferroni’s method for multiple comparisons.

Results

A total of 268 CDH patients were identified. Sixty of these were previously reported(5), and 208 are new. Overall survival to discharge was 210 patients (78%). The CDH Study Group Predicted Survival for this group, based on birth weight and 5 minute Apgar score was 59.8%, p<0.001. All patients were discharged home breathing spontaneously, without surgical airways, and on no support other than nasal cannula oxygen.

A total of 28 patients had associated anomalies which we deemed lethal or highly severe, and which either independently or in combination with the CDH had a devastating effect on the patient’s chance for survival (Table 1). The majority of these were diagnosed prenatally and were not treated with intent to cure. Five were treated, did not survive, and are included here because of the severity of the associated anomaly, which if included would confound the treatment analysis. These 28 patients are excluded from subsequent analysis, which follows.

Table 1.

Lethal or Highly-Severe Associated Anomalies (28 of 268, 10%)

(Removed from subsequent treatment analysis)

| Chromosomal | 4 | |

| Trisomy 12 | (1) | |

| Trisomy 18 | (1) | |

| Tetrasomy 12p | (2) | |

| Cardiac | 8 | |

| Hypoplastic L heart | (2) | |

| DORV | (1) | |

| Transposition, single ventricle | (1) | |

| Truncus arteriosus | (1) | |

| Tricuspic atresia | (1) | |

| Complete heart block | (1) | |

| Non-compaction cardiomyopathy | (1) | |

| CNS Malformations | 3 | |

| Iniencephaly | (1) | |

| Serious Brain malformation w/ hydrocephalus. Rx withheld | (2) | |

| Multiple combined | 5 | |

| Cloacal exstrophy, myelomeningocele | (1) | |

| Hepatopulmonary fusion, AV canal | (1) | |

| Combined severe vertebral and chest wall deformity | (3) | |

| Bilateral CDH | 6 | |

| Bilateral | (5) | |

| Bilateral with DORV | (1) | |

| DOA (outborn, arrived w/o vitals, CPR in progress, pupils fixed) | 2 |

Two hundred forty patients without lethal associated anomalies were encountered. Prematurity of 34 weeks or less affected 30 patients (30 of 240, 12%), Patients with Tetralogy of Fallot (n=2), coarctation of the aorta (n=2), VSD (18), and ASD (n=15) are included, as are a number of patients with non-lethal chromosomal inversions, additions, and deletions. Two patients with congenital CMV, both of whom died and diagnosis of CMV was made at autopsy, are also included in the treatment analysis. Two hundred ten of 240 patients (88%) without associated lethal anomalies survived.

Anatomic Subsets

Mean birth weight, Apgar-1, Apgar-5, predicted survival and observed survival all declined significantly across the CDH spectrum, with left liver-down the least severe, right CDH was intermediate, and left liver-up CDH the most severe (Table 2). Details of treatment related to repair, ECMO, and survival outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Anatomic Subgroups and outcomes

| CDH (lethal associated anomalies removed) | Total | Left liver down | Right | Left Liver Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Patients | 240 | 97 | 42 | 101 |

| Survived (%) | 210 (88%) | 96 (99%) | 38 (91%) | 76 (75%) |

| # non-ECMO | 144 | 86 | 19 | 39 |

| Mean time to Repair (hrs) | 106 +/− 71 | 106 +/− 77 | 87 +/− 44 | 117 +/− 68 |

| Survived (%) | 138 (96%) | 86 (100%) | 19 (100%) | 33 (85%) |

| # ECMO | 96 (40%) | 11 (11%) | 23 (55%) | 62 (61%) |

| Survived (%) | 72 (75%) | 10 (91%) | 19 (83%) | 43 (69%) |

| # ECMO in 1st 16 hours of life | 27 | 0 | 8 | 19 |

| Survived (%) | 17 (63%) | – | 7 (88%) | 10 (53%) |

| # ECMO patients with “opportunity for repair” | 69 | 11 | 15 | 43 |

| # ECMO patients repaired first, ECMO second | 30 | 6 | 6 | 18 |

| Mean time to Repair (hrs) | 40.9 +/− 43 | 27 +/− 15 | 35 +/− 26 | 48 +/− 53 |

| Survived (%) | 27 (90%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (67%) | 17 (94%) |

| # ECMO pts. ECMO first | 39 | 5 | 9 | 25 |

| Mean time to ECMO (hrs) | 45 +/− 40 | 31 +/− 10* | 34 +/− 16 | 47 +/− 42 |

| Survived | 28 (72%) | 4 (80%) | 8 (89%) | 16 (64%) |

| All ECMO firsts, repair on ECMO | 34 of 66 | 0 of 5 | 12 of 17 | 22 of 44 |

| Survived | 23 (68%) | – | 12 (100%) | 11 (50%) |

| All ECMO firsts, repair after ECMO | 25 of 66 | 4 of 5 | 4 of 17 | 17 of 44 |

| Survived | 22 (88%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 15 (88%) |

| All ECMO firsts, did not achieve repair | 7 of 66 | 1 of 5 | 1 of 17 | 5 of 44 |

| Survived (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Survival Comparison Repair 1st vs. ECMO 1st (controlled for CDH SG Predicted Survival) | p=0.132 | p=ns | p=ns | p=0.0549 |

Analysis of Survival related to timing of repair relative to ECMO, All Patients

Ninety-six patients were treated with ECMO. Twenty-seven of these went on ECMO in the first 16 hours and were not considered to have opportunity for repair. Sixty-nine patients required ECMO and had opportunity for repair before ECMO. Twenty-seven of 30 patients repaired first followed by ECMO survived (90%) and 28 of 39 patients treated with ECMO first survived (72%).

Combined

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (p=0.0656), multivariate logistic regression controlling for predicted survival (p=0.132), and Cox Proportional Hazards Model (p=0.1196) showed a trend to improved survival in patients repaired before ECMO but did not achieve statistical significance.

Left Liver-Down (LLD)

Only 11 of 97 LLD patients required ECMO and only one died, severely limiting statistical analysis of this sub-group. Univariate analysis (p=0.455) and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (p=0.273) showed no statistically significant relationships between surgical repair and ECMO survival.

Right

42 patients with right CDH were treated and 23 required ECMO. Univariate analysis (p=0.525) and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (p=0.307) showed no significant difference in outcomes in patients repaired before ECMO versus those who arrived on ECMO unrepaired.

Left Liver-Up (LLU)

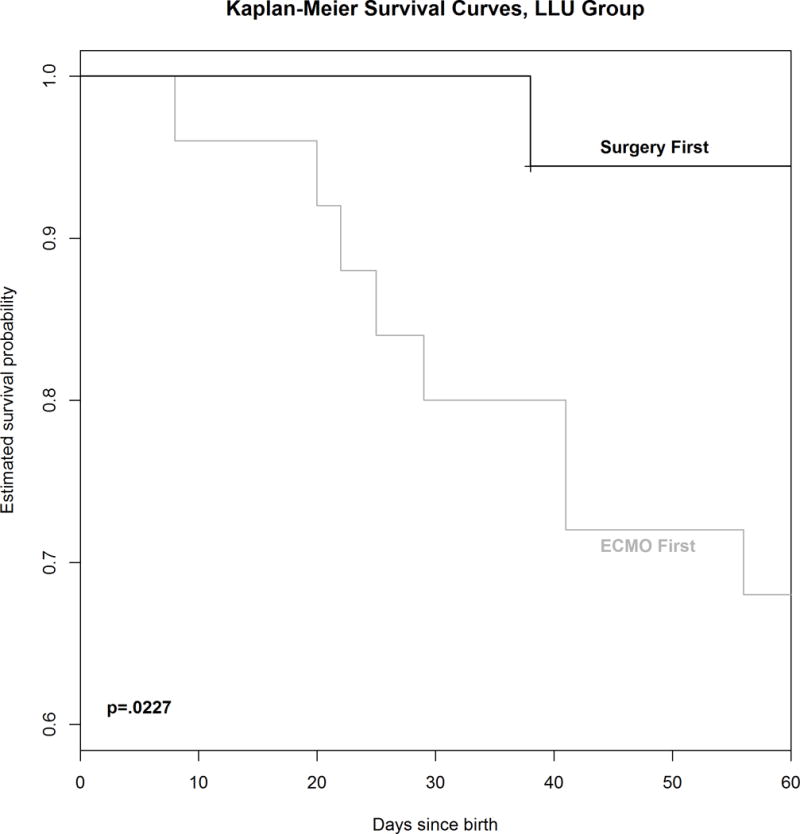

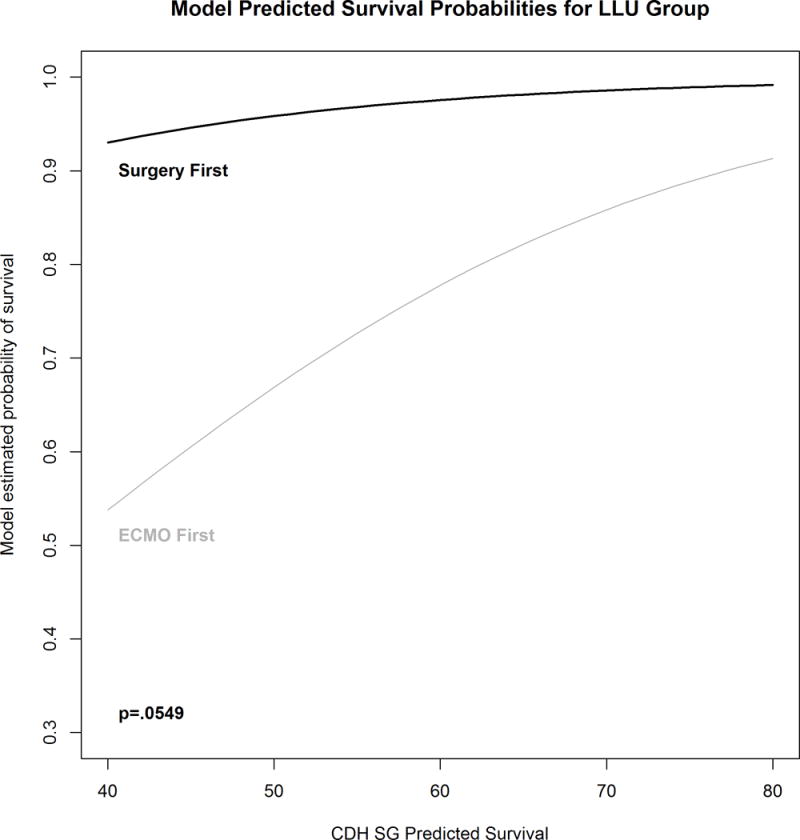

Forty-three LLU patients who required ECMO had opportunity for repair. Eighteen were treated with repair first and seventeen survived (94%), while 25 arrived on ECMO unrepaired and 16 survived (64%, p=0.028). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis is shown in Figure 1. Mean predicted survival in the patients who underwent repair first was 59.3+/−24%, while the mean predicted survival in patients treated with ECMO first was 52.8%+/− 19%. Multivariate logistic regression controlling for Predicted Survival (Figure 2) showed a strong trend to improved survival with repair first that failed to meet accepted standards for statistical significance, p=0.0549. Cox Proportional Hazards modeling showed that survival was marginally better in the repair-first group (p=0.067). It is estimated by this model that left liver-up patients who were repaired before ECMO faced 0.14 times the hazard of death as ECMO-first LLU patients (95% CI={0.017, 1.15}.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve comparing 18 patients with left CDH, Liver-up who underwent repair before ECMO to 25 patients who went to ECMO unrepaired.

Figure 2.

Multivariate logistic regression model comparing survival in 18 left liver-up CDH patients who underwent repair before ECMO to 25 who had opportunity for repair but went to ECMO un-repaired, controlled for CDH SG Predicted Survival. It is estimated that patients who are repaired first have 11.4 times the odds of survival as patients who arrive to ECMO unrepaired (95% CI=[1.41, 286]. The relationship does not quite reach statistical significance p=0.0549.

Risk of ECMO

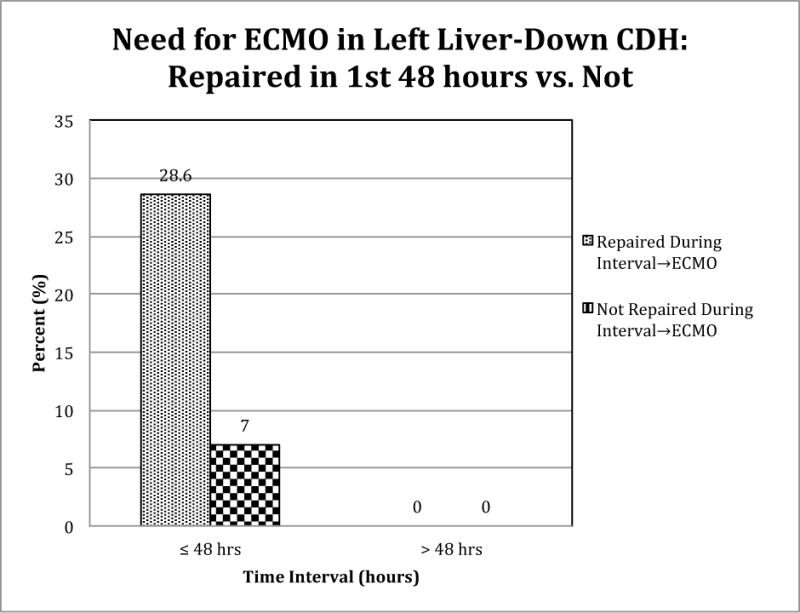

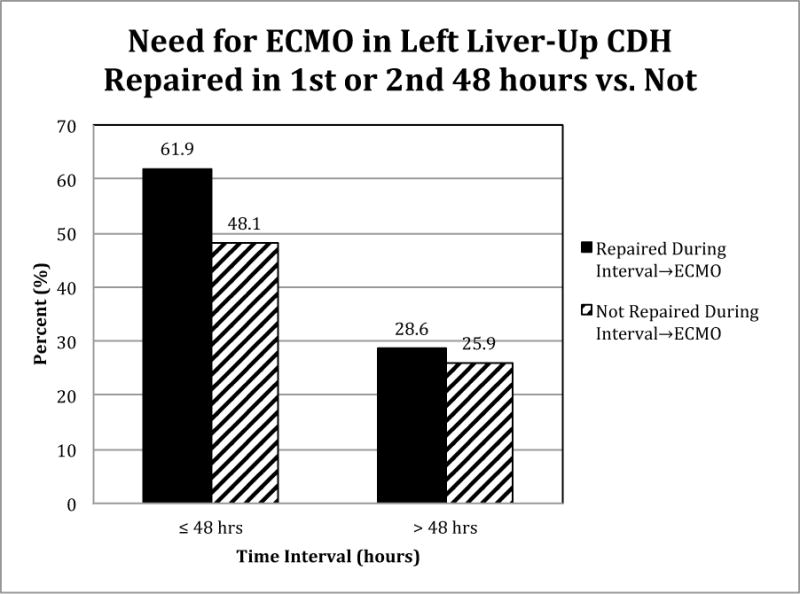

The majority of risk for ECMO occurred in the first 48 hours in left liver-down patients, and in the first 96 hours in left liver-up patients. We calculated the incidence of ECMO in patients who underwent repair in the first and second 48 hour intervals after birth and compared these to patients not repaired during these periods, and who were not already repaired or on ECMO.

Total

Timing of surgery proved to be a significant predictor of ECMO in CDH patients. Multivariate logistic regression controlled for Predicted Survival estimated that patients repaired within the first 48 hours of life have 2.5 times the odds of ECMO compared to patients repaired later or not at all (95% CI=[1.23,5.13], p=0.0113. CDH Study Group Predicted Survival is a significant predictor of needing ECMO p<.0001.

Left Liver-Down

Six of 21 LLD CDH patients repaired in the first 48 hours (29%) went on to ECMO while only 5 of 71 (7%) not repaired during this time interval went to ECMO (Figure 3). Multivariate logistic regression controlling for Predicted Survival estimated a 6.3 fold increase in risk of needing ECMO in LLD CDH patients repaired in the first 48 hours (p=.0110).

Figure 3.

Timing of surgery is a significant predictor of ECMO in CDH patients with left liver-down. Logistic regression controlled for Predicted Severity estimated that patients repaired within the first 48 hours have 6.3 times the odds of ECMO (95% CI=[1.55, 28.1]) p=0.0110 compared to patients repaired later or not at all.

Right

Five of 9 (55%) of patients with right CDH repaired in the first 48 hours went to ECMO while 10 of 24 (42%) not repaired in the first 24 hours went to ECMO. One of 8 repaired in the second 48 hours went to ECMO whereas 2 of 9 not repaired went to ECMO. Multivariate analysis showed that timing of surgery is not a significant predictor of ECMO for right CDH patients (p=0.399)

Left Liver-Up

Thirteen of 21 (62%) repaired in the first 48 hours went to ECMO while 25 of 52 (48%) not repaired in the first 48 hours went to ECMO. Two of 7 (29%) repaired in the second 48 hours went to ECMO while 7 of 27 (26%) not repaired went to ECMO. Repair of CDH in the first or second 48 hours (Figure 4) was not a significant predictor of ECMO by univariate or multivariate techniques (p=.4330).

Figure 4.

Timing of surgery is not a significant predictor of ECMO for LLU patients. p=0.4330

Discussion

The results of this large series, now matured over 19 years and 268 consecutive patients, demonstrate several important findings. First, high survival rates were achieved using gentle ventilatory techniques and presently available treatment modalities. This finding is not new and has also been shown by others(21–24), but the size of this experience and the magnitude of survival achieved make it important nonetheless. After removal of patients judged to have associated lethal anomalies, which represented 10% of the total, survival of left liver-down CDH was 99%, right CDH 90%, left liver-up CDH was 76%, and the aggregate survival in these patients was 88%. Survivors were discharged breathing spontaneously and on no additional respiratory support than supplemental oxygen, verifying that even patients with significant pulmonary hypoplasia can have good pulmonary outcomes. This information is important for physicians and prospective parents in evaluating treatment options and pregnancy termination.

The second important finding is that patients along the anatomic CDH spectrum are different and appear to benefit from different approaches to surgical timing. The data show with significant clarity that repair of CDH in the first 48 hours of life increases need for ECMO, and that this effect is most prominent in the least anatomically severe patients. While the effect diminishes rapidly as CDH anatomic severity increases, these data show clearly that delay of repair beyond 48 hours is indicated in most patients in order to decrease subsequent need for ECMO.

The data also strongly suggest that patients on the severe end of the anatomic severity spectrum, those with left liver-up CDH, enjoy a survival benefit when repaired before ECMO. Although the multivariate analysis doesn’t quite reach statistical significance, Figure 2 shows increasing divergence of the expected survival curves as Predicted Survival falls, supporting the postulate that patients with increasingly severe CDH benefit from a surgically more aggressive approach. This concept is new, and may be counter-intuitive for a generation of CDH physicians who have witnessed improvements in survival associated with delaying surgical repair. However, it may be that the main benefit in delaying repair is in decreasing need for ECMO, with resultant improved survival due to decreased need for ECMO.

The optimal use of the findings of this study requires refining our ability to define those left liver-up patients most likely to need ECMO. Examples of such predictive methods currently exist, but will likely will need to be center specific for optimal utility(25–27). Further application of prenatal imaging in order to quantify liver in left chest as several authors have suggested, could also potentially aid in predicting risk for ECMO. (15,28,29).

Other methods for improving survival in CDH patients who arrive on ECMO unrepaired are described in the literature. A recent report from the CDH study group showed that repair after ECMO rather than repair on ECMO was associated with improved survival(30), although the improved survival reported (approximately 65%) did not achieve the survival here (94%). Similarly Dassinger reported good results with early repair on ECMO (71%)(31) . Neither of these studies reflected a pure experience with left liver-up patients.

We see these data as representing an important step in understanding the differing effects of anatomic severity on CDH treatment effects and outcomes. Further work in this area is indicated, and while some might embrace the concept of repair before ECMO in patients with left liver-up CDH, at the very least these data are expected to help CDH physicians understand at a deeper level which patients benefit from surgical delay, and which patients might benefit from earlier correction of surgical anatomy. Further, these data should help us to interpret already published studies and plan better future studies by asking if the data are controlled for anatomic severity, and to question if the conclusions apply equally to all patients across the CDH spectrum.

This study might be criticized for the relatively high utilization of ECMO. This rate is virtually identical to other contemporary studies. (5,23,31). Further, we do not employ exclusion criteria from ECMO based on disease severity, which may increase our use compared to others.

This report suffers from several weaknesses. The first is weakness inherent in a retrospective review, but this study is strengthened by its size, and by the consistency of a single institution experience with a highly consistent ventilation protocol and therapeutic oversight. Second, although there are strong trends in the data favoring a more aggressive surgical approach in patients with anatomically more severe CDH, the final multivariate analysis of the question posed here failed to meet accepted statistical significance with a p value of 0.0549. Third, anatomic data such as LHR and volume of herniated liver, which could further sub-divide anatomic severity in the left liver-up group, were lacking in enough patients over this 19-year experience that these data were not included. Finally, the clinical applicability of the observation that repair of CDH before ECMO appears to be beneficial in patients with severe CDH may be seen as providing little clinical guidance to bedside decision making, as the clinical decline in patients who subsequently require ECMO may be precipitous and leave little opportunity for safe repair.

In summary, these data show that patients with anatomically less severe CDH survive at high rates and have less risk of needing ECMO if repair is delayed beyond 48 hours. Patients with left liver-up CDH however, appear to have a survival benefit when undergoing repair before ECMO. These data confirm the postulate that CDH patients respond differently to treatment strategies across the anatomic severity spectrum, and lay important groundwork for the development of a risk specific treatment strategy for optimal management of CDH. Finally, the survival attained in this large and inclusive series of CDH patients should be reassuring to physicians and parents faced with a new prenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Discussion of ASA Paper Number 30 (13-00620)

Long-Term Maturation of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Treatment Results.

DISCUSSANT

DR. PETER DILLON (Hershey, PA): The authors present the largest single-institution retrospective CDH experience that has been published to date with truly outstanding clinical results. In 19 years, they have treated over 260 patients, 264, as was elucidated, with CDH and have an overall survival rate of 79%. When the infants with lethal anomalies were removed, their survival rate is 88%, and they have been able to maintain that over the 20 years. This is truly remarkable considering the registry data we have that is multi-institutional has the highest survival rate of 67%.

The core hypothesis that the authors attempt to address here is the timing of surgery in relation to the institution of ECMO therapy, and that is the area that I would like to focus on in my questions.

In terms of their results, they showed that the infants who had liver up, in other words, liver in the left chest, above the diaphragmatic defect, had a greater chance of survival if surgery was performed early in the course of treatment before the initiation of ECMO, which runs a bit counter to current therapy, where delayed therapy, sometimes as long as several weeks, has been proposed. In the manuscript, you mentioned at the very end the inborn/outborn status. I would be curious to know how that factored into your data analysis, at least in some type of multivariate regression, because I’m concerned that you may still have a selection bias in terms of how you ultimately arrived at surgical decision to manage those cases.

In the group that had surgical repair prior to or in anticipation of ECMO, how do you know that they truly needed ECMO? You did not have any standard criteria, I believe. And it was at the discretion of the surgical intervention that you chose to follow that pathway.

In the aggregate group, did you analyze your results over specific time periods? You put everything together into this data analysis. What would happen if you broke the process up into decade analysis or other time intervals to see if there was indeed a change in your results over time?

Finally, in those patients who had surgical repair before ECMO, how do you explain your higher survival rate over the same category of patient in the CDH registry? What solid criteria can you propose for determining when surgery should be done before, during, or after ECMO?

CLOSING DISCUSSANT

DR. DAVID W. KAYS: The first question was about inborn versus outborn status. There was a tremendous increase in our inborn status. Multiple reports have shown that, in general, inborn patients are a higher-risk group and have lower survival than patients that are outborn. This might seem counterintuitive, but the sickest patients that are outborn die and never make it to management at the inborn hospital. This results in a selection bias as inborn patients are more ill and the fact that the survival was maintained with a tremendous increase in inborn patients adds to the power of the results.

How did we know if the patients truly needed ECMO when we operated on them before ECMO? This is an important and difficult question that we addressed as best we could with comparisons of multiple variables. We compared the patients who needed ECMO with those that did not and showed significant differences. We then compared the patients who needed ECMO but were repaired first with those who went to ECMO first and did not find significant differences, showing the patients who were treated with repair before ECMO were similar to the patients treated with ECMO first. You asked about the indications for ECMO, and I think I can best respond that it is our goal to never use ECMO, and we use all available modalities to what we consider are their therapeutic-toxic limits trying to avoid ECMO. ECMO is never instituted based on risk of needing ECMO, but only because of serious clinical declines affecting both pre- and post-ductal oxygenation. Going forward, it would be very valuable to develop robust methods and equations for predicting ECMO.

We did look at our own data to try to predict ECMO. We did logistic regression, starting with anatomic severity as the first variable, then adding lung-to-head ratio to the model. Although lung-to-head ratio was independently highly correlated with outcomes, the addition of that variable into the logistic regression equation did not give us acceptable sensitivity and specificity to predict ECMO well. We are continuing to analyze these data and are including more post‐natal physiologic data such as CO2 elimination and PO2 levels extended to various time points to see if we can improve our predictive abilities. We hope to report those results soon.

You asked a very interesting question about survival in different time eras over the 19 year experience. While not presented here, the reason we started intervening more aggressively with surgical repair in sicker patients was the loss of a few patients in the middle of the experience who were treated with surgical delay. Our paradigm at that time was affected by national trends to delay surgery while focusing on pulmonary hypertension, but after losing these unrepaired patients on ECMO, patients we felt were otherwise completely survivable, we became more aggressive about getting the anatomy corrected as a key part of CDH treatment.

If we reported our results over 4 or 5 year time intervals you would actually see that in the middle eras, our results worsened. I considered reporting this, but the numbers do not reach statistical significance over those intervals, only in aggregate. Since we have fully embraced a more aggressive surgical approach in the sickest patients, survival rates have recovered and exceed 90%.

You asked why survival in our patients exceeds that in the CDH registry. This is surely multifactorial and beyond the scope of this discussion, but we believe each patient can survive and treat with that expectation. Also, our team benefits from consistent leadership with a clear therapeutic approach which covers all aspects of care including ventilation, fluids, repair and ECMO. This results in a very high level of treatment consistency which, we believe, contributes to good outcomes.

DISCUSSANT

DR. DENNIS P. LUND (Phoenix, AZ): I rise to congratulate you on the contributions that the University of Florida Gainesville has made in the care of patients with diaphragmatic hernias. This has been one of the great problems for pediatric surgeons.

I have two questions.

The first is related to your ventilatory strategy over time. I was intrigued by the fact that your ECMO utilization rate did not really change between the first 60 patients you presented and the 200-plus you present here. It would strike me that if you had gone to a kinder, gentler ventilation strategy like most pediatric diaphragmatic hernia centers, your ECMO utilization rate would rise. So, I would ask you to comment on that.

The second question has to do with prenatal diagnosis and the advice that you give to parents who come to see you. The Holy Grail for in-utero intervention has been to predict children who might need prenatal intervention based on things like lung-to-head ratio, liver-up, etcetera. Based on your experience, what advice are you giving to families who have potentially very severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients? And are you referring any of them to centers for consideration of in-utero therapy?

CLOSING DISCUSSANT

DR. DAVID W. KAYS: Our ECMO utilization did not change significantly over the two periods. We were ventilating gently the whole time, and the ventilatory strategy really did not change. We did learn from this analysis that operating on babies on the milder end of the spectrum in the first 48 hours actually increases need for ECMO. We look forward to decreasing ECMO utilization in the future as we apply new lessons learned.

How do we deal with the prenatal evaluations? We believe, at a very fundamental level, that these babies have what it takes to survive and we treat each one as though they are going to survive. Although not presented here but described in the manuscript, there were 44 patients from other states around the U.S. who travelled to the University of Florida Shands Children’s Hospital for delivery and post-natal management. Of those 44 that did not have lethal or severe associated anomalies, 42 went home with their families, for a 95.5% survival rate. In short, we are very optimistic about CDH patients treated at our institution, and at this point do not refer them out for prenatal interventions. We inform them of our results and let them make their own decisions.

DISCUSSANT

DR. ROBERT J. TOULOUKIAN (New Haven, CT): My question is about selecting the size and the position of the liver as the best surrogate for survival. As you know, there are many studies that use other parameters. You have mentioned lung development, certainly. But there are others, including the progression of lung size over time, the presence of the stomach above or below the diaphragm, and the issue of whether pneumothorax was present at the time of birth. What percentages of patients were inborn and whether you tested liver-up and liver-down against any of the other standard surrogates for survival?

CLOSING DISCUSSANT

DR. DAVID W. KAYS: We actually started our analysis with a five-step definition of anatomic severity, one right-sided and four left-sided. We looked at left liver-down, stomach-down; we looked at liver-down, stomach-up. We looked at liver-up, small amount of liver; and then liver-up, large amount of liver, to give us four left-sided groups. Because the numbers were small relative to left sided, we did not look at sub-groups of right-sided CDH. A great deal of effort went into analyzing all of these sub-groups.

It turned out that what really mattered in our series was liver-down versus liver-up, and sub-definitions added little to the analysis. Survival in patients that were liver-down, whether it was stomach-up or stomach-down, was 99%, and adding the variable stomach-down or stomach-up was not useful. To define the amount of liver-up, we noted the position of the falciform ligament at the time of surgery or autopsy, with liver up to falciform ligament defined as “small” liver-up and greater than this being “large” liver-up. But in a series that spanned 19 years, we did not have that level of definition in all patients and felt that assigning this without clear data risked adding bias, so we removed that sub-grouping. In the end it turned out that the analysis was cleaner and more meaningful using the simple but powerful variable of liver-down or liver-up.

The other reason we favored analysis by anatomic rather than lung measurement data was we had this level of anatomic data on every patient, whereas we did not have lung-to-head ratio data for all of our patients. Especially early in the series, many of the patients were out-born and had no prenatal data. Regarding pneumothorax as a defining variable, our pneumothorax rate is less than 1% and therefore is not an adequate discriminator. But there is no doubt that other grading systems can be used, and modern MRI analysis can further refine liver-up severity.

A final message I would like to reiterate with this group of esteemed surgeons is that congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a surgical disease. The survival of unrepaired patients, except in those minimally affected, is zero. We greatly appreciate the opportunity to present these data, and thank you for your attention and questions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Florida UL1 TR000064

This work was also supported by a philanthropic grant from the Greek Orthodox Ladies Philoptochos Society

Footnotes

This is a single center, retrospective review of a 19-year experience in congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

All authors deny any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Seetharamaiah R, Younger JG, Bartlett RH, et al. Factors associated with survival in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a report from the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1315–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wung JT, James LS, Kilchevsky E, et al. Management of infants with severe respiratory failure and persistence of the fetal circulation, without hyperventilation. Pediatrics. 1985;76:488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wung JT, Sahni R, Moffitt ST, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: survival treated with very delayed surgery, spontaneous respiration, and no chest tube. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:406–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson JM, Lund DP, Lillehei CW, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia–a tale of two cities: the Boston experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Mar;32(3):401–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kays DW, Kays DW, Langham MR, et al. Detrimental effects of standard medical therapy in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Surg. 1999;230:340–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00007. discussion348–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonoff MB, Hustead VA, Groth SS, et al. Protocolized management of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: effect on survival. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidry CA, Hranjec T, Rodgers BM, et al. Permissive hypercapnia in the management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: our institutional experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:640–645. 647.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.036. discussion646–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagolan P, Cuenca AG, Winfield RD, et al. Impact of a current treatment protocol on outcome of high-risk congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.009. discussion313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann SR, Stadler K, Heilmann A, et al. Stabilisation of cardiopulmonary function in newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia using lung function parameters and hemodynamic management. Klin Padiatr. 2012;224:e1–e10. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masumoto K, Colvin J, Reiss I, et al. Improvement in the outcome of patients with antenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia using gentle ventilation and circulatory stabilization. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:487–92. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reickert CA, Hirschl RB, Schumacher R, et al. Effect of very delayed repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on survival and extracorporeal life support use. Surgery. 1996;120:766–72. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80029-8. discussion772–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyer V, Moya F, Tibboel R, et al. Late versus early surgical correction for congenital diaphragmatic hernia in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001695. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nio M, Haase G, Kennaugh J, et al. A prospective randomized trial of delayed versus immediate repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:618–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90725-0. Available from: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=8035269&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.la Hunt de MN, Adewumi A, Langham MR, et al. Is delayed surgery really better for congenital diaphragmatic hernia?: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1554–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90176-1. Available from: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=8943121&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazar DA, Ruano R, Cass DL, et al. Defining “liver-up”: does the volume of liver herniation predict outcome for fetuses with isolated left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia? J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1058–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitano Y, Nakagawa S, Kuroda T, et al. Liver position in fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia retains a prognostic value in the era of lung-protective strategy. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1827–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann PC, Morriss FHJ, Klein JM. Prediction of survival in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia based on stomach position, surgical timing, and oxygenation index. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29:383–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1304817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Mortellaro VE, Beierle EA, Guidry CA, Saxonhouse MA, Douglas-Escobar M, et al. “Pulling the plug–”management of meconium plug syndrome in neonates. J Surg Res. 2012;175:e43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Estimating disease severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the first 5 minutes of life. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:141–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online).

- 21.Boloker J, Bateman DA, Wung J-T, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in 120 infants treated consecutively with permissive hypercapnea/spontaneous respiration/elective repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:357–66. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher JC, Jefferson RA, Arkovitz MS, et al. Redefining outcomes in right congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downard CD, Jaksic T, Garza JJ, et al. Analysis of an improved survival rate for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:729–32. doi: 10.1016/jpsu.2003.50194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryner BS, Kim AC, Khouri JS, et al. Right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia: high utilization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and high survival. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:883–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park HW, Lee BS, Lim G, et al. A simplified formula using early blood gas analysis can predict survival outcomes and the requirements for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:924–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odibo AO, Najaf T, Vachharajani A, et al. Predictors of the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and survival in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a center’s 10-year experience. Prenat Diagn. 2010 Jun;30(6):518–21. doi: 10.1002/pd.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaible T, Busing KA, Felix JF, et al. Prediction of chronic lung disease, survival and need for ECMO therapy in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: additional value of fetal MRI measurements? Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1076–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victoria T, Bebbington MW, Danzer E, et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging in prenatal prognosis of the fetus with isolated left congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:715–23. doi: 10.1002/pd.3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danzer E, Victoria T, Bebbington MW, et al. Fetal MRI-calculated total lung volumes in the prediction of short-term outcome in giant omphalocele: preliminary findings. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012;31:248–53. doi: 10.1159/000334284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group, Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Bryner BS, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: does timing of repair matter? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.022. discussion1171–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dassinger MS, Copeland DR, Gossett J, et al. Early repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:693–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]