Summary

Background

Treatment-resistant major depressive disorder is common and potentially life-threatening in older persons, in whom little is known about the benefits and risks of augmentation pharmacotherapy.

Methods

We conducted a multi-site, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to test the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole augmentation for older adults with treatment-resistant depression. We treated 468 participants aged 60 and older with current major depressive episode with venlafaxine extended-release (ER); 96 (20.5%) did not complete this open phase, 191 (40.8%) remitted, and 181 (38.7%) did not remit and were randomized to 12 weeks of double-blind augmentation with aripiprazole or placebo. The computer-generated randomization was done in blocks and stratified by site. The primary endpoint was remission, defined as Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale scores ≤10 (and at least two points below the score at the start of the randomized phase) at both of the final two consecutive visits. We also assessed resolution of suicidal ideation, and safety and tolerability with cardiometabolic and neurological measures. Analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00892047.

Findings

Older adults on aripiprazole had a higher remission rate than those on placebo (44% versus 29%; odds ratio [OR]=2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.7, p=0.03; number needed to treat [NNT]=6.6 [95% CI 3.5–81.8]). Overall, remission was stable during 12 additional weeks of continuation treatment. The resolution of suicidal ideation was more marked with aripiprazole than with placebo. Akathisia was the most common adverse effect (27% of participants on aripiprazole). Compared to placebo, aripiprazole was also associated with more Parkinsonism but not with treatment-emergent suicidal ideation, QTc prolongation, or increases in adiposity, glucose, insulin, or lipids.

Interpretation

In older adults who fail to achieve remission from depression with a first-line antidepressant, the addition of aripiprazole is effective in achieving and sustaining remission. Tolerability concerns include potential for akathisia and Parkinsonism.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health, UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry, Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute.

Keywords: depression, elderly, treatment resistance, aripiprazole, antidepressant

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in older adults, leading to disability, suicidality, and increased mortality which can be mitigated by treatment.1–4 Most older adults with depression receive treatment in general medical settings,5 and the geriatric mental health workforce projections show that the vast majority of older adults with depression will continue to be treated chiefly in the primary care sector.6 A major problem is treatment-resistance to first-line therapies: 55–81% of older adults with MDD fail to remit with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor(SNRI).7–10 Yet, unlike younger adults,11, 12 there is little evidence from controlled trials to guide second-line or augmentation pharmacotherapy.13, 14 Second-line treatments including mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation with lithium, psychostimulants, or second generation antipsychotics, interpersonal psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), have been proposed. Of these treatments, replicated evidence in older adults support only lithium augmentation, which is often difficult to tolerate in this age group.13–15 Without evidence, clinicians cannot weigh the benefits and risks of these treatments in older adults.16

Aripiprazole is a second generation (“atypical”) antipsychotic approved by the Food and Drug Administration for augmentation treatment of MDD. Its pharmacodynamic actions include dopamine D2 and D3 receptor partial agonism and serotonin 5HT1a and 5HT2a receptor antagonism.17–19 Industry-sponsored trials in younger depressed adults have demonstrated the efficacy of aripiprazole as an augmentation to SSRIs or SNRIs.20 However, minimal data exist to clarify benefits of aripiprazole in older adults with MDD.21–23 Additionally, little is known about its safety and tolerability in this population. This is concerning, as aripiprazole in younger patients with MDD is associated with neurological and cardiometabolic adverse effects, particularly akathisia (restlessness) and weight gain.20 Older adults may be more vulnerable to such adverse effects.16 Lastly, antipsychotics are associated with increased mortality in older adults with dementia, possibly due to QTc prolongation, arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.16

In summary, aripiprazole augmentation has potential benefits and risks in the treatment of late-life depression, neither of which is adequately informed by existing data. Accordingly, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole augmentation in older adults whose depression did not respond to an adequate trial of venlafaxine. We hypothesized that, compared to placebo, aripiprazole would be associated with a higher rate of remission (primary outcome), a greater improvement of depressive symptoms and resolution of suicidal ideation, and stability of remission. We also hypothesized that use of aripiprazole might lead to a higher rate of akathisia. We also examined treatment-emergent Parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia, and change in adiposity, weight, lipids, glucose, and QTc.

Methods

The study was conducted in three academic centers (University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA [coordinating site]; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Canada, and Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) after approval by the institutional review boards. An independent data and safety monitoring board oversaw the study. All participants provided written, informed consent. From July 2009 to January 2014, we recruited adults age 60 and older, who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive episode with at least moderate symptoms, as defined by a Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)24 score ≥15 (ranges 0–60; higher scores indicate greater severity of depression). Exclusion criteria included dementia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, current psychotic symptoms, and alcohol or substance abuse or dependence within the past six months. Dementia was based on a view of medical records, cognitive screening, a formal review of dementia criteria, and for unclear cases, an informant’s interview.

We started open treatment with venlafaxine extended release (ER) in 468 participants to determine prospectively treatment resistance, defined by failure to remit after at least twelve weeks of treatment with at least four weeks at the highest tolerated dose (minimum of 150mg/d and maximum 300 mg/d). Remission was defined as a MADRS score ≤10 at both of the final two consecutive visits. The majority of participants were treated for 12–14 weeks but protocol guidelines allowed for a longer trial (up to 24 weeks) if needed to clarify remission status.

Those who did not achieve remission with venlafaxine monotherapy were then randomized to the addition of aripiprazole or placebo, while maintaining the final dose of venlafaxine achieved during initial open treatment. Randomization was performed using a permuted block approach to ensure treatment balance within each study site. Treatment was double-blinded; only the database administrator and research pharmacists had knowledge of treatment assignment. In this 12-week randomized phase, aripiprazole or matched placebo tablets were started at 2mg daily and titrated as tolerated to a target dose of 10mg daily that could be increased up to 15mg daily if needed. To assess stability of remission, participants who achieved remission were then followed for an additional 12 weeks during which the study medication (aripiprazole or placebo) was continued under double-blinded conditions. Adherence was monitored in all phases by self-report and pill counts.

Efficacy Outcomes

The MADRS was administered at each weekly or biweekly visit. We carried out regular intersite sessions to maintain interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] in this study: 0.997). The primary efficacy outcome was remission, defined as completing the randomized phase with a MADRS score ≤10 at both of the final two consecutive visits with at least a two-point drop from the start of the phase. For these visits the MADRS was administered by an independent evaluator. To identify participants who needed a different intervention during the 12-week continuation phase, we ascertained relapse, defined as having enough symptoms to meet criteria for a current major depressive episode.25 We also examined changes in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17-item (Ham-D)26 and both the resolution and the emergence of suicidal ideation using the Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI).27 Finally, we examined changes in health-related quality of life, using the 36-item Medical Outcome Survey.28

Safety and Tolerability Outcomes

Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured at all visits by study physicians using three validated scales:29 the Barnes Akathisia Scale(outcome: global akathisia item), the Simpson Angus Scale(treatment-emergent Parkinsonism defined by a 2-point increase in total score), and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (global involuntary movements item). There was adequate-to-excellent interrater agreement for these scales (ICCs range: 0.57–0.74). Cardiometabolic indices were measured at the beginning and end of the randomized phase. The primary cardiometabolic outcome was change in whole body adiposity quantified using DEXA scanning.30 We also measured changes in weight, fasting plasma lipids (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides), and fasting blood glucose and insulin. We also measured changes in QTc on EKG at the beginning and end of the 12-week randomized phase.

Self-reported somatic symptoms were elicited at each visit with the UKU scale,31 which characterizes 46 common side effects of psychotropic medications; a side effect was considered present if there was a 2-point increase on the corresponding UKU item. Finally, we recorded serious adverse events (SAEs) that resulted in death, life-threatening problems, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, hospitalization (or prolongation of hospitalization), or medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of these outcomes.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using the intention-to-treat principle. We had calculated that a sample size of 200 randomized participants would provide 80% power to show superior efficacy of aripiprazole, assuming a difference of 20% with placebo. For the primary efficacy outcome, a logistic regression compared the proportion of participants meeting criteria for remission at the end of the randomized phase; secondarily we examined time to remission using a Cox model. For the secondary efficacy outcome of depressive symptom change, we used mixed-effect modeling32 examining non-linear trajectories and using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to determine the best fitting model.33 Following a strategy outlined by Senn,34 we included site as a covariate in all efficacy analyses. For the primary neurological tolerability outcome, we examined the proportion of participants experiencing akathisia (and, secondarily, the proportions experiencing Parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia). For the MADRS outcome measured longitudinally, mixed effect models were employed. For the primary cardiometabolic tolerability outcome, we measured change in DEXA total fat (and, secondarily, changes in body fat percentage, weight, lipids, glucose, and QTc). We used SAS (Version 9) and R (version 3.0.1). P-values ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding and senior authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

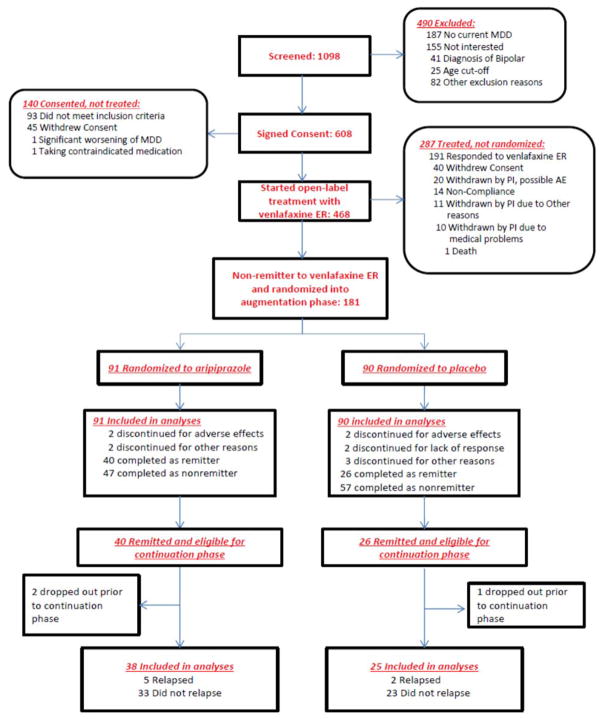

Of 468 eligible participants who started venlafaxine ER, 96 (20.5%) did not complete the open treatment phase because they withdrew consent, were withdrawn by the investigator, or for other reasons, 191 (40.8%) remitted, 181 (38.7%) did not remit, 91 were randomized to aripiprazole and 90 to placebo (Figure 1). Table 1 presents the characteristics of these 181 participants.

Figure 1.

Enrollment and Outcomes

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Randomized to Augmentation Treatment with Aripiprazole or Placebo50,51

| N Missing |

All N=181 Median (25th/75th centile) or % (n) |

Aripiprazole N=91 Median (25th/75th centile) or % (n) |

Placebo N=90 Median (25th/75th centile) or % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Years |

0 | 66.0 (62.8/70.5) | 66.4 (62.8/71.6) | 65.7 (62.8/69.8) |

| % (n) > 70 yrs | 0 | 27 (49) | 30 (27) | 24 (22) |

| % (n) Female | 0 | 57 (103) | 57 (52) | 57 (51) |

| % (n)White | 0 | 88 (159) | 88 (80) | 88 (79) |

| Education (yrs) | 0 | 14.0 (12.0/16.0) | 14.0 (12.0/16.0) | 14.0 (12.0/16.0) |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale50 Total |

0 | 9.0 (7.0/13.0) | 10.0 (7.0/13.0) | 9.0 (7.0/12.0) |

| Count | 0 | 6.0 (4.0/7.0) | 6.0 (4.0/8.0) | 6.0 (4.0/7.0) |

| % (n) diagnosed with diabetes | 6 | 15 (26) | 18 (16) | 11 (10) |

| % (n) diagnosed with hypertension | 6 | 54 (94) | 51 (44) | 57 (50) |

| # of coprescribed non- study medications | 0 | 5 (3/8) | 5 (3/8) | 6 (3/8) |

| % (n) taking benzodiazepines | 0 | 40 (73) | 40 (36) | 41 (37) |

| RBANS Total Index Score | 3 | 95.0 (85.0/107.0) | 98.0 (85.0/108.0) | 94.0 (85.0/102.0) |

| Brief Symptom Inventory47– Anxiety Subscale scorea | 0 | 0.8 (0.3/1.3) | 1.0 (0.5/1.3) | 0.5 (0.3/1.3) |

| % (n) with recurrent depression | 0 | 71 (129) | 68 (62) | 74 (67) |

| Age at first depressive episode (yrs) | 0 | 40.0 (20.0/57.0) | 44.0 (24.0/57.0) | 35.0 (17.0/57.0) |

| Duration of current episode (wks) | 2 | 104.0 (35.0/364.0) | 118.0 (45.0/364.0) | 104.0 (28.0/317.0) |

| % (n) who have failed to respond to at least one adequate antidepressant trial during the current episode | 3 | 74 (132) | 73 (66) | 75 (66) |

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale Enrollment |

0 | 28.0 (25.0/32.0) | 29.0 (25.0/33.0) | 28.0 (24.0/32.0) |

| Randomization | 0 | 23.0 (18.0/28.0) | 24.0 (18.0/29.0) | 23.0 (18.0/26.0) |

| Venlafaxine dose at randomization (mg/d) | 0 | 300 (300/300) | 300 (300/300) | 300 (300/300) |

RBANS: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; scaled score mean is 100, standard deviation 15.52

Measured at randomization (i.e, end of initial open treatment with venlafaxine).

Continuous data are shown as median (IQR); baseline comparisons are not made with inferential statistics as per the recommendations of Senn et al.34

Efficacy Outcomes

Remission

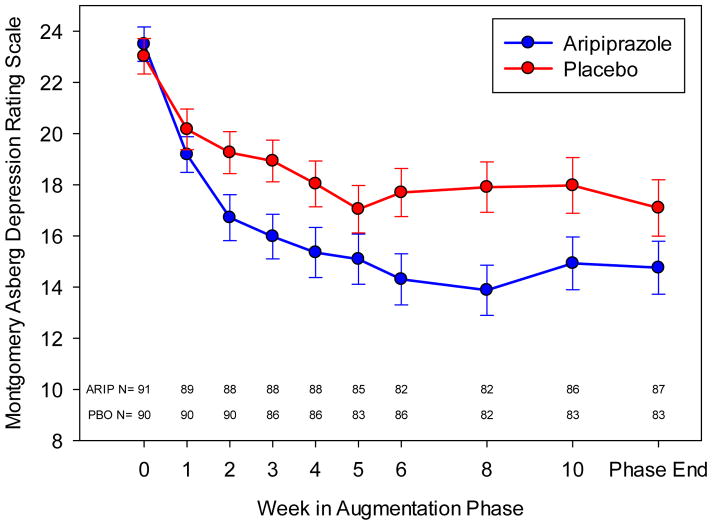

Forty of the 91 (44.0%) participants randomized to aripiprazole and 26 of the 90 (28.9%) randomized to placebo achieved remission, a significant difference (Table 2). Time to first remission similarly favored aripiprazole (Figure S1). The median final aripiprazole dose was 7 mg/d (range: 2–15) in remitters and 10 mg/d (range: 2–15) in non-remitters (Figure S2). Those randomized to aripiprazole experienced a larger decrease in their MADRS scores (Figure 2) and Ham-D scores (Figure S3).

Table 2.

Remission from Depression during Augmentation with Aripiprazole or Placebo.

| Variable | Level | DF | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study arm | Aripiprazole vs. Placebo§ | 1 | 2.0 (1.1–3.7) | 0.03 |

| Site | Pittsburgh vs. Toronto§ | 2 | 2.6 (1.2–5.8) | 0.047¶ |

| Washington University vs. Toronto§ | 2.4 (1.1–5.3) |

Intention to treat (ITT) cohort based on all 181 randomized participants

Baseline level used for calculation of odds ratio

Test based on a Wald chi square statistic with 2 degrees of freedom

NOTE: interactions between cell and site variables are non-significant

Figure 2. Reduction in Depressive Symptoms during Augmentation with Aripiprazole or Placebo.

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) mean scores (± standard error bars) plotted at the protocol specified sampling times in the augmentation phase. Number of patients at each time is indicated at the bottom of the plot. Analyses used time as a continuous measure calculated using dates. Based on the BIC, a cubic model best fit the trajectory of MADRS scores over the span. The model indicates that both groups showed improvement over time but the aripiprazole group showed a significantly greater improvement. Based on the modeled data, the aripiprazole group decreases approximately 7.5 points over 12 weeks while the placebo group decreases approximately 5.0 points over the same time period.

Resolution of Suicidal Ideation

30/91 (33.0%) participants on aripiprazole and 25/90 (27.8%) on placebo had suicidal ideation at baseline; it resolved in 22/30 (73.3%) vs. 11/25 (44.0%) (Wald chisq[1]=5.2, p=0.02).

Health-Related Quality of Life

The MOS-Physical Component Score changed from 42.9 (SD 12.8) to 40.9 (SD 11.3) for participants on aripiprazole and from 41.6 (SD 11.4) to 41.4 (SD 11.0) for participants on placebo, a non-significant difference between groups (F[1,167]=2.08, p=0.15). The aripiprazole-treated participants showed a greater improvement in the MOS-Mental Component Score (from 29.5 [SD 9.4] to 42.2 [SD 14.4]), compared to placebo-treated participants (from 31.2 [SD 9.8] to 37.9 [SD 13.6]), (F[1,167]=7.41, p=0.007).

Safety and Tolerability Outcomes (Table 3)

Table 3.

Adverse Events and Tolerability Measures during the Augmentation Phase

| Aripiprazole (n=91) | Placebo (n=90) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of SAEs | 4/91 (4.4%) | 2/90 (2.2%) |

| Number of AEs leading to discontinuation of study medication | 3/91 (3.3%) | 3/90 (3.3%) |

| Emergent suicidal ideation (in those with no ideation at start of phase) | 13/61 (21.3%) | 19/65 (29.2%) |

| Suicide | 1/91 (1.1%) | 0/90 (0%) |

| Extrapyramidal syndromes | ||

| Akathisia | 24/91 (26.7%) | 1/90 (12.2%) |

| Mild | 19/91 (20.9%) | 9/90 (10%) |

| Moderate-severe | 5/91 (5.5%) | 2/90 (2.2%) |

| Persistent (still present at last visit of phase) | 5/85 (5.9%) | 2/84 (2.4%) |

| Incidence of Dyskinesia | 0/85 (0%) | 2/84 (2.4%) |

| Parkinsonism | 15/86 (17.4%) | 2/81 (2.5%) |

| QTc prolongation on EKG (to ≥480msec) | 1/78 (1.3%) | 0/79 (0%) |

| QTc change, mean (SD) msec | +1.9 (30.8) | +1.6 (25.9) |

AE=adverse events, SAE=Severe adverse events

One participant on aripiprazole committed suicide after five weeks of double-blind treatment; this was neither due to emergent suicidal ideation nor to aripiprazole side effects but was determined by investigators to be a result of the individual’s ongoing and longstanding suicidal ideation. Early discontinuation of medication and SAEs: 5/91 (5.5%) participants randomized to aripiprazole discontinued medication prior to the end of the randomized phase (1 completed suicide; 1 due to jitteriness/akathisia, 1 due to worsening Parkinsonism; and 2 withdrew consent) vs. 8/90 (8.9%) on placebo (2 due to lack of efficacy; 1 due to worsening Parkinsonism; 2 due to headaches; and 3 withdrew consent). SAEs were seen in 4/91 (5%) participants on aripiprazole (1 each: completed suicide; hospitalized for congestive heart failure; suffered mild stroke; hospitalized for diverticulitis) and 2/90 (2%) on placebo (myocardial infarction; hospitalized for vomiting attributed to accidentally taking extra venlafaxine).

Out of 46 possible side effects queried (Table S1), the most frequently reported with aripiprazole compared to placebo were increased dream activity (26.7% vs. 13.8%), weight gain (19.8% vs. 9.2%), and tremor (5.8% vs. 0%).

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Akathisia was observed at some point during the randomized phase in 26.7% participants randomized to aripiprazole vs. 12.2% on placebo (exact p=0.02). Typically, akathisia was mild and did not persist to the end of the treatment phase; however, akathisia was associated with a temporary increase in suicidal ideation in 3 (3.3%) on aripiprazole vs. 0 on placebo. Incidence of dyskinesia was 0% with aripiprazole vs. 2/84 (2.4%) with placebo, while the rate of Parkinsonism was higher: 15/86 (17.4%) with aripiprazole vs. 2/81 (2.5%) with placebo. Both akathisia and Parkinsonism occurred at a median (Interquartile Range [IQR]) aripiprazole dose of 7 mg/d (5, 10), range 2–15 mg/d.

Cardiometabolic outcomes

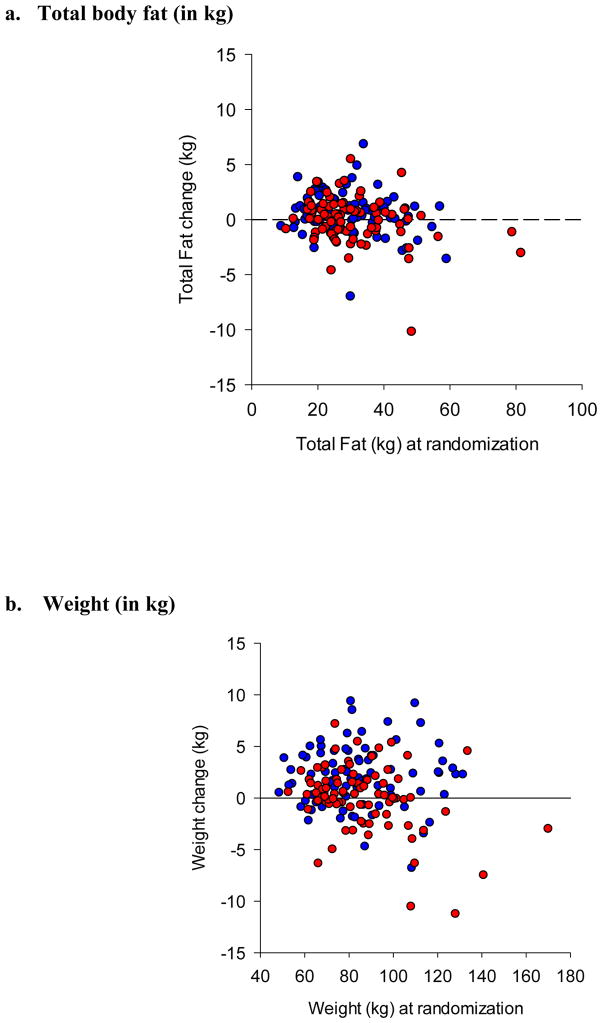

Participants randomized to aripiprazole showed greater increase in body weight, but not in total body fat than those randomized to placebo (Figure 3). There were no differences between groups in changes in percentage of body fat, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, glucose, or insulin levels (Table S2).

Figure 3. Changes in Cardiometabolic Parameters during Augmentation with Aripiprazole or Placebo.

mean (SD) total fat change was +0.54 kg (1.98) with aripiprazole (n=81) vs. −0.06 (2.08) with placebo (n=83), F (1,160)=3.49, p=0.064.

Mean (SD) total weight change was +1.93 kg (3.00) with aripiprazole (n=84) vs. 0.01 (3.15) with placebo (n=85), F(1,165)=16.26, p<0.001.

Stability of remission and other continuation outcomes

63/66 remitters (38 on aripiprazole; 25 on placebo) participated in the 12-week continuation phase. The two groups did not differ significantly in rates of depression relapse or change in MADRS scores (Figure S4). Incidence of dyskinesia in this phase was 2/38 (5.3%) for aripiprazole and 1/25 (4.0%) for placebo. Mean (SD) body weight changes in this phase were +0.84 kg (2.55) for aripiprazole and −0.16 (2.49) for placebo; we did not measure DEXA body fat or any other cardiometabolic biomarkers in this phase.

Discussion

This is the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in late life. There are three main findings: first, the addition of aripiprazole was effective at getting older adults with treatment-resistant depression to remission and maintaining remission over 12 weeks of continuation. Second, aripiprazole was associated with some akathisia and Parkinsonism. Third, aripiprazole was not associated with an increase in cardiometabolic risk as measured by changes in whole body adiposity, plasma lipids, glucose, or insulin. These findings help clarify the risk-benefit ratio of aripiprazole augmentation for clinicians facing the common situation of treatment-resistant depression in their older patients.35

Aripiprazole was effective in inducing remission, with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 6.6 relative to placebo, which is comparable to augmentation treatments for treatment-resistant depression in young adults (lithium NNT=5, atypical antipsychotics NNT=9).20, 36 For further perspective, an NNT of 13 for the overall efficacy of short-term pharmacotherapy of late-life depression has been reported.37 Almost one-half (44%) of aripiprazole-treated participants remitted, in spite of their history of treatment resistance: all had failed to remit after moderate to high-dose SNRI treatment, and three-quarters had also failed to respond to at least one adequate antidepressant trial prior to enrolling in this study. By comparison, less than a third of younger patients with MDD and this degree of treatment resistance remit when treated in randomized trials.11, 12 The benefits of aripiprazole included a reduction of suicidal ideation. This is important because depressed older adults are at high risk for completed suicide (many of whom have seen a primary care physician within the past month).4 Moreover, the remission attained during the initial 12 weeks of treatment appeared stable over a 12-week continuation period. This is a relatively short follow-up period but most relapses in late-life depression occur soon after attaining remission.25, 38, 39

Our safety and tolerability data address several concerns about the use of atypical antipsychotics, particularly in older adults. First, the high rate of akathisia in young adults with depression treated with aripiprazole20 raises concerns in older adults who may be at higher risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects.40 Indeed, we found a higher rate of akathisia with aripiprazole than with placebo (26.7% vs. 12.2%). However, akathisia was typically mild with comparable rates in both groups by the end of the randomized phase (5.9% vs. 2.4%), suggesting it is transient and can be managed with watchful waiting or dose reduction. Akathisia was associated with a temporary increase in suicidal thoughts in three participants treated with aripiprazole and it led to aripiprazole discontinuation in another one. These more concerning issues did not occur in any participant randomized to placebo. Aripiprazole was also associated with higher rates of Parkinsonism and complaints of tremor. Clinicians need to be aware of these adverse effects of aripiprazole and adjust dose or potentially switch treatment. However, we found no increased risk of tardive dyskinesia with aripiprazole, relative to placebo, over 24 weeks of treatment. This observation is important because the incidence of tardive dyskinesia in older patients has been reported to be as high as 25% over six months of exposure to first generation antipsychotics.41 However, this study does not address the question of risk of tardive dyskinesia with chronic (i.e., years’) use of aripiprazole.

Regarding the cardiometabolic risks, we did not find that aripiprazole significantly increased either the amount or percentage of body fat. Further, aripiprazole did not cause an increase in fasting lipids, glucose, or insulin. Therefore, over the short term at least, aripiprazole did not typically induce cardiometabolic risks: of an average of 1.9kg weight gain during 12 weeks of acute treatment, only about 30% was due to fat gain. Most weight gain, therefore, may be either re-gain as described with successful antidepressant treatment,42 hydration, or peripheral edema as described with antipsychotic use.16 The difference between the weight and adiposity changes underscores the importance of utilizing direct measures of adiposity to characterize the effects of treatments on cardiometabolic risk.43 Nevertheless, increases in adiposity, lipids, and glucose are well-known adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics; clinicians need to follow guidelines and monitor cardiometabolic parameters when prescribing aripiprazole.44

Additional safety concerns with antidepressant treatment include treatment-emergent suicidal ideation, which has been hotly debated since the advent of a “black box warning” on all antidepressants for this risk in adolescents and young adults, but not in older adults.45 We did not find any evidence for increased treatment-emergent suicidal ideation with aripiprazole. Nevertheless, we recommend ongoing assessment of suicidal ideation and suicide risk in depressed older adults during treatment.46 Additionally, we did not detect any QTc prolongation with aripiprazole, which is important because many psychotropic medications have that potential, particularly in older adults.47 Finally, drug interactions can occur between aripiprazole and some commonly-prescribed antidepressants (such as paroxetine and duloxetine), and we chose venlafaxine as a lead-in antidepressant in part to avoid this potential interaction.

Limitations of the study included our sample size being slightly smaller than our target sample size and a relatively small number of participants age 75 and older, in whom rates of cognitive impairment and incipient dementia are higher.46 Also, with the exclusion of patients with dementia, our sample size, and the 12-week duration of follow-up, our study cannot fully address tolerability and safety concerns with aripiprazole in older adults, and it does not allay safety concerns with antipsychotic use in older adults with dementia.16, 48 Also, given the high frequency of treatment non-response to first-line antidepressants, it is unclear how aripiprazole augmentation should fit into structured depression management approaches for older adults.49 For example, it remains unknown whether venlafaxine should be increased to very high doses (>300mg/day) prior to attempting augmentation.

In conclusion, we found that aripiprazole is moderately effective in older adults with treatment-resistant depression. Clinicians prescribing this medication should be aware of its propensity to cause akathisia and Parkinsonism. However, the potential benefits of remission from depression and greater reductions in suicidal ideation outweigh these usually mild adverse events.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Before undertaking the study, we searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.govfor studies published or underway that examined augmentation or second-line pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in older adults. The search included the terms “treatment resistance”, “depression”, “elderly”, “augmentation strategy”, “antidepressant.” The search also utilized the investigators’ familiarity with the literature and ongoing research in the area.

As described in two recent critical reviews of the topic,13, 14 few trials of any kind and no well-powered trials currently exist to provide evidence for clinicians to make well-reasoned decisions about second-line treatment in the common scenario of treatment-resistant late-life depression.

Added value of this study

Our findings bridge this critical gap by providing clinicians with evidence on the benefits and risks of augmenting an antidepressant with an atypical antipsychotic, aripiprazole, in older adults with a depression that did not remit with a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Implications of all of the available evidence

About one-half of older adults with a major depressive disorder do not remit with first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Aripiprazole has a favorable risk/benefit ratio in these older adults, most of whom receive treatment in primary care or general medical settings. The NNT of aripiprazole of 6.6 is comparable to the NNT in young adults of the two most well-studied augmentation therapies: lithium (NNT= 5; Crossley and Bauer, Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68(6):935-40) and atypical antipsychotics (NNT = 9; Nelson and Papakostas, Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166(9):980-91).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported primarily by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH083660 and P30 MH90333 to University of Pittsburgh, R01 MH083648 to Washington University, and R01 MH083643 to University of Toronto). Additional funding was provided by the UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry, the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research (at Washington University), the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto. Bristol-Myers Squibb contributed aripiprazole and placebo tablets, and Pfizer contributed venlafaxine extended release capsules for this study. The authors thank the clinical and data management staff and the patient participants of the “IRL GREY study (Incomplete Response in Late-Life Depression: Getting to Remission)”, and the Data and Safety Monitoring Board Members: Joel Streim, M.D., University of Pennsylvania; Jeff Williamson, M.D., Wake Forest University; J. Craig Nelson, M.D., University of California San Francisco; Joel Greenhouse, Ph.D., Carnegie Mellon University; Steven Roose, M.D., Columbia University.

Footnotes

Contributors: EJL, BHM, JWN, MAD, MAB, and CFR designed the study and wrote the protocol. EJG, BHM, DMB, JFK, JAS, and CFR recruited patients for the study and participated in coordination. EJL, SJA, AEB, and CFR had access to all the data and analyzed the data. EJL, BHM, SJA, and CFR were responsible for the decision to submit the report, and drafted it. All authors read, critically revised, and approved the report.

Declaration of Interests: Dr. Lenze has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), Roche, Lundbeck, the Sidney R. Baer Foundation, the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research, the Barnes-Jewish Foundation, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation.

Dr. Mulsant currently receives research funding from Brain Canada, the CAMH Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the US National Institute of Health (NIH). During the last five years, he also received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial), Eli-Lilly (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial), and Pfizer (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). He directly owns stocks of General Electric (less than $5,000).

Dr. Blumberger has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD), National Institute of Health (NIH), Temerty Family through the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Foundation and the Campbell Research Institute. He receives research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. and he is the site principal investigator for three sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He also receives in-kind equipment support from Magventure for an investigator-initiated study. None the above represent a conflict of interest with manuscript under consideration.

Dr. Karp has received medication supplies for investigator initiated trials from Pfizer and Reckitt Benckiser.

Dr. Newcomer reports Data Safety Monitoring Board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Data Safety Monitoring Board for Merck, honoraria from VIVUS, Data Safety Monitoring Board from Amgen.

Dr. Anderson reports receiving grant support from the NIH grants P30 MH090333, R01 MH090250, R01 MH084921.

Dr. Dew receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, and serves on the editorial boards of numerous clinical journals. None of these activities represent a conflict of interest with the manuscript under consideration.

Dr. Butters has received research support from the National Institutes of Health. She served as a consultant for Medtronic and Northstar Neuroscience from whom she received remuneration for neuropsychological evaluations performed within the context of clinical trials. She also served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, from whom she received remuneration for participating in cognitive disorder diagnostic consensus conferences for research participants in a clinical trial. None of the above represents a conflict of interest with the manuscript under consideration.

Ms. Stack and Ms. Begley report no conflicts.

Dr. Reynolds reports receiving pharmaceutical support for NIH-sponsored research studies from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, Pfizer, and Lilly; receiving grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Aging, National Center for Minority Health Disparities, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the John A Hartford Foundation, National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC), Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; and serving on the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry editorial review board. He has received an honorarium as a speaker from MedScape/WEB MD. He is the co-inventor (Licensed Intellectual Property) of Psychometric analysis of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) PRO10050447 (PI: Buysse).

Literature cited

- 1.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callahan CM, Kroenke K, Counsell SR, Hendrie HC, Perkins AJ, Katon W, et al. Treatment of depression improves physical functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):367–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo JJ, Morales KH, Bogner HR, Raue PJ, Zee J, Bruce ML, et al. Long term effect of depression care management on mortality in older adults: follow-up of cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care. BMJ. 2013;346:f2570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eden J, Maslow K, Le M, Blazer D, editors. The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? Washington DC: 2012 by the National Academy of Sciences; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allard P, Gram L, Timdahl K, Behnke K, Hanson M, Sogaard J. Efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine in geriatric outpatients with major depression: a double-blind, randomised 6-month comparative trial with citalopram. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(12):1123–30. doi: 10.1002/gps.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schatzberg A, Roose S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in geriatric outpatients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):361–70. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194645.70869.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, Sheikh J, Xu J, Dinkel JJ, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):900–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kok R, Nolen W, Heeren T. Venlafaxine versus nortriptyline in the treatment of elderly depressed inpatients: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(12):1247–54. doi: 10.1002/gps.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Stewart JW, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Quitkin F, Warden D, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maust DT, Oslin DW, Thase ME. Going beyond antidepressant monotherapy for incomplete response in nonpsychotic late-life depression: a critical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(10):973–86. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31826576cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper C, Katona C, Lyketsos K, Blazer D, Brodaty H, Rabins P, et al. A systematic review of treatments for refractory depression in older people. Am J Psych. 2011;168(7):681–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Dew MA, Martire LM, Miller MD, Cyranowski JM, Lenze E, et al. Treating depression to remission in older adults: a controlled evaluation of combined escitalopram with interpersonal psychotherapy versus escitalopram with depression care management. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1134–41. doi: 10.1002/gps.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose T, Uwahodo Y, Yamada S, Miwa T, Kikuchi T, Kitagawa H, et al. Mechanism of action of aripiprazole predicts clinical efficacy and a favourable side-effect profile. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(3):375–83. doi: 10.1177/026988110401800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conway CR, Chibnall JT, Cumming P, Mintun MA, Gebara MA, Perantie DC, et al. Antidepressant response to aripiprazole augmentation associated with enhanced FDOPA utilization in striatum: a preliminary PET study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;221(3):231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mamo D, Graff A, Mizrahi R, Shammi CM, Romeyer F, Kapur S. Differential effects of aripiprazole on D(2), 5-HT(2), and 5-HT(1A) receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: a triple tracer PET study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1411–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steffens DC, Nelson JC, Eudicone JM, Andersson C, Yang H, Tran QV, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder in older patients: a pooled subpopulation analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(6):564–72. doi: 10.1002/gps.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheffrin M, Driscoll HC, Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Miller MD, et al. Pilot study of augmentation with aripiprazole for incomplete response in late-life depression: getting to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):208–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutherford B, Sneed J, Miyazaki M, Eisenstadt R, Devanand D, Sackeim H, et al. An open trial of aripiprazole augmentation for SSRI non-remitters with late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22 (10):986–91. doi: 10.1002/gps.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1130–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(2):343–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Medical Outcomes Trust; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweet RA, DeSensi EG, Zubenko GS. Reliability and applicability of movement disorder rating scales in the elderly. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5(1):56–60. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamel EG, McNeill G, Van Wijk MC. Change in intra-abdominal adipose tissue volume during weight loss in obese men and women: correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and anthropometric measurements. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(5):607–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kass RE, Wasserman L. A reference Bayesian test for nested hypotheses and its relationship to the Schwartz criterion. JASA. 1995;90:928–34. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senn S. Testing for baseline balance in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1994;13(17):1715–26. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unutzer J, Park M. Older adults with severe, treatment-resistant depression. JAMA. 2012;308(9):909–18. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):935–40. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS. Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):558–67. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181693288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized controlled trial in patients older than 59 years. JAMA. 1999;281(1):39–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Frank E, Perel JM, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Begley A, et al. High relapse rate after discontinuation of adjunctive medication for elderly patients with recurrent major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;153(11):1418–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeste DV, Maglione JE. Treating older adults with schizophrenia: challenges and opportunities. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):966–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinon BJ, Kollack-Walker S, Jeste D, Gupta S, Chen L, Case M, et al. Incidence of Tardive Dyskinesia in Older Adult Patients Treated With Olanzapine or Conventional Antipsychotics. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0891988714541867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber E, Stack J, Pollock BG, Mulsant B, Begley A, Mazumdar S, et al. Weight change in older depressed patients during acute pharmacotherapy with paroxetine and nortriptyline: a double-blind randomized trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8(3):245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haupt DW, Fahnestock PA, Flavin KA, Schweiger JA, Stevens A, Hessler MJ, et al. Adiposity and insulin sensitivity derived from intravenous glucose tolerance tests in antipsychotic-treated patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(12):2561–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amiel JM, Mangurian CV, Ganguli R, Newcomer JW. Addressing cardiometabolic risk during treatment with antipsychotic medications. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):613–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328314b74b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedman RA. Antidepressants’ black-box warning--10 years later. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1666–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor WD. Clinical practice. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1228–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1402180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beach SR, Celano CM, Noseworthy PA, Januzzi JL, Huffman JC. QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications. Psychosom Med. 2013;54(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodoulou M, Douglas S, McShane R, Kossakowski K, et al. The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): long-term follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):151–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leontjevas R, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M, Teerenstra S, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Koopmans RT. A structural multidisciplinary approach to depression management in nursing-home residents: a multicentre, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9885):2255–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41(3):237–48. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derogatis L. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. 3. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Randolph C. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.