Abstract

Percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVADs) and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) are used to provide mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Contemporary trends in their utilization and impact on in-hospital mortality are not known. Using the National Inpatient Sample (2004–2012), we identified 5031 patients who received a PVAD and 122,333 who received an IABP on the same day as PCI using ICD9 codes. Utilization of MCS increased from 1.3% of all PCIs in 2004 to 3.4% in 2012 (P trend<0.001), with increase in the use of both PVAD (<1/10000 PCIs [2004–2007] to 38/10000 [2012]) and IABP (132/10000 PCIs [2004] to 299/10000[2012] P<0.0001 for both). PVAD recipients were older (69 vs. 65 years), more likely to have heart failure (68% vs. 41%), chronic kidney disease (27% vs. 11%, P<0.001 for all), and be admitted electively (30% vs. 11%), but less likely to have AMI (52% vs. 90%), cardiogenic shock (23% vs. 50%) or need mechanical ventilation (16% vs. 29%) compared to IABP recipients. Unadjusted in-hospital mortality was lower in PVAD compared to IABP recipients (12.8% vs. 20.9%, P<0.001). However, in propensity-matched analyses (1:2), in-hospital mortality was similar in both groups (odds ratio 0.88, 95% CI 0.70–1.09). In conclusion, there has been a marked increase in the utilization of MCS in patients undergoing PCI. Unadjusted mortality with use of PVADs is lower than IABP but may be due to their selective use in lower-risk patients. Randomized trials are necessary to establish their effectiveness in supporting high-risk PCI.

Keywords: percutaneous coronary intervention, mechanical circulatory support, percutaneous left ventricular assist devices, intra-aortic balloon pump, utilization

Introduction

Nearly 1 million patients undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the United States each year,1 of which 18% are considered high risk. Risk of mortality is nearly two-fold higher in patients undergoing high-risk PCI compared to other PCI patients.2 Use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices is supported by clinical practice guidelines in patients undergoing high-risk PCI procedures.3 Until recently, the choice of MCS was limited to intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP). However, percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVAD), namely the Impella and the TandemHeart, which provide superior hemodynamic support compared to IABP are increasingly used in clinical practice.4, 5 In spite of expert consensus on utility of MCS devices in high risk PCI,6 empirical data regarding the comparative effectiveness of MCS in patients undergoing high-risk PCI are lacking. Despite limited evidence, use of MCS devices especially PVADs has increased in recent years.5 We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data – a large national administrative database of hospitalized patients, to examine contemporary use of MCS on the same day as a PCI procedure. We examined national trends in the use, clinical characteristics and patient outcomes in patients receiving MCS devices on the same day as PCI, and compared use of PVAD with IABP in this setting.

Methods

The NIS is the largest all-payer database of hospitalized patients in the United States, managed under the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The design of the NIS has been described previously,5 and has been included in the Appendix. Briefly, the NIS is comprised of a random 20% sample of patients hospitalized at acute-care hospitals from participating states during a given year, obtained after stratification of hospitals by bed-size, teaching status and census region. Patient-level and hospital-level weights were provided to obtain national estimates. The NIS includes detailed information on patient characteristics including demographic variables (e.g. age, sex, race, etc.), primary and secondary discharge diagnoses and procedures. Both diagnoses and procedures are available as International Classification of Diseases – 9th Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes as well as their validated combinations into broad categories using the Clinical Classification of Diseases Software (CCS). We used a combination of ICD-9 and CCS codes to identify comorbid conditions and inpatient procedures. A maximum of 25 discharge diagnoses and 15 procedures can be included for each patient. For each procedure, the day of the procedure is also available. Given that PVAD procedures were first included in the NIS in the year 2004, we restricted our study cohort to years 2004–2012

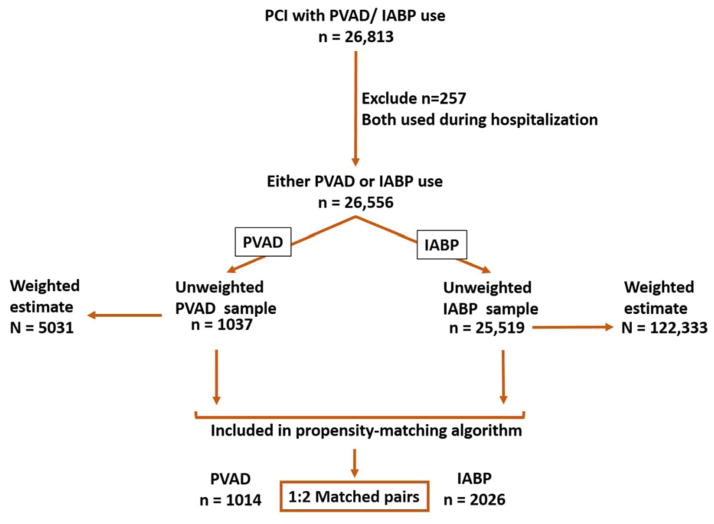

We identified all patients, age 18 years and above, who underwent PCI (CCS-code: 45) during 2004–2012 along with placement of either a PVAD (ICD-9CM code – 37.68) or an IABP (ICD-9CM code – 37.61) on the same day as the PCI procedure. Patients where both PVAD and IABP were used in the same hospitalization were excluded (n=257). Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of patient selection.

Figure 1.

Flow sheet summarizing process of selection of cases

First, we examined calendar-year trends in use of PCI procedures supported by either PVAD or IABP. Second, we compared patient demographics, co-morbidities, discharge disposition (e.g. home, home with home health, other healthcare institution) and length of stay for PVAD and IABP groups using the Rao-Scott chi square for categorical variables and survey specific paired t-test for continuous variables. Since length of stay was not normally distributed, we transformed that variable to its natural logarithm and compared the geometric mean of the transformed length of stay variables between the two groups. Next, we compared unadjusted inhospital mortality using similar methods as above. All descriptive analyses used to obtain unbiased national estimates of outcome frequencies, means, and variances, while accounting for the survey design.7

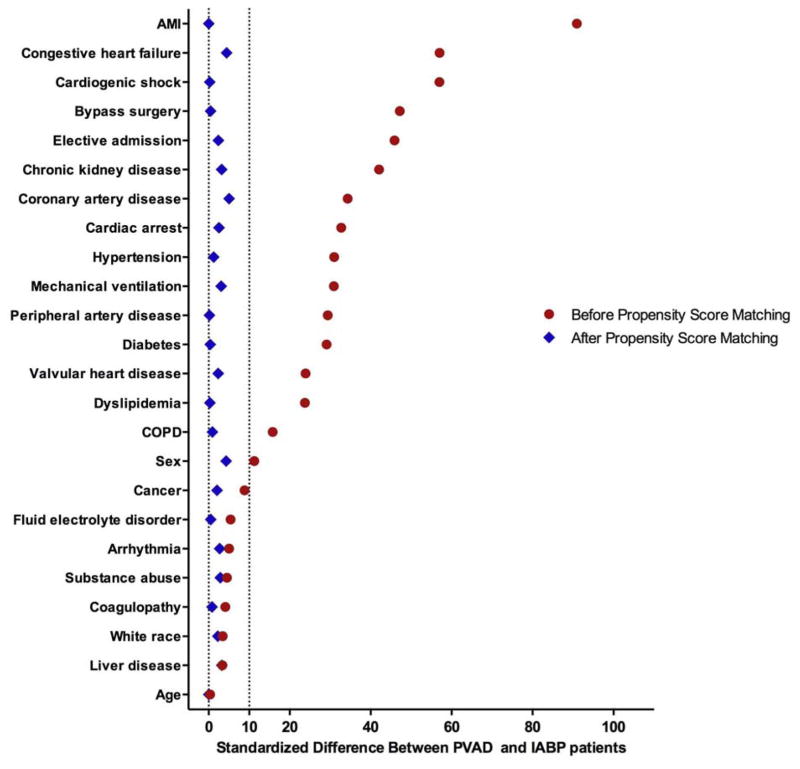

To examine the association between the type of mechanical circulatory support device (PVAD vs. IABP) and in-hospital mortality, we conducted a matched propensity score analysis to explicitly account for confounding by indication (selection bias). In our model, which explicitly accounted for the survey design of the NIS, we matched each PVAD recipient to 2 IABP recipients with similar covariates, represented as propensity scores. Variables used in our model for estimating propensity scores included age, sex, race, discharge diagnoses (cardiogenic shock, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), cardiac arrest, prior coronary atherosclerosis, heart failure, valvular heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias, peripheral arterial disease), co-morbidities (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, fluid-electrolyte disorder, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coagulopathy, substance-use disorder), procedures (coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG] or mechanical ventilation) and nature of admission (non-elective vs. elective). Details of the propensity-matching algorithm are included in the Appendix. To test whether our matching algorithm was successful in achieving covariate balance, we calculated standardized differences for all covariates and compared them between PVAD and IABP groups before and after matching. A standardized difference of <10% for all covariates after matching is indicative of a successful match.8 We used the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for matched data to compare the effect of PVAD with IABP on in-hospital mortality.

Given that risk of mortality in patients undergoing PCI differs according to the level of acuity, we repeated our analyses above to examine mortality separately in patients with (1) cardiogenic shock, (2) AMI without cardiogenic shock, and (3) patients without AMI or cardiogenic shock. The subgroup of patients without AMI or cardiogenic shock likely represents patients undergoing high-risk elective PCI, given the absence of acute indications for hemodynamic support (i.e. AMI, cardiogenic shock). For comparative and subgroup analysis, we used domain analysis which ensures that the assumption of an infinite discharge universe is satisfied (central to the analysis of the NIS data) and that the estimated population statistics and measures of variance are accurate.7

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings. First, to account for unmeasured confounding due to differences in hospitals with and without PVAD programs, we restricted IABP recipients to those hospitals where at least 1 PVAD device was used in a given year. Second, to account for the availability of Impella devices, we limited the analysis to years 2009 through 2012 to capture the years after the approval of the first Impella device (Impella 2.5 Recover) in May 2008.9

The level of significance was set at a P value of 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC), including SAS PROC SURVEYMEANS and PROC SURVEYFREQ for analysis of complex survey data. The study was reviewed by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board, which waived the requirement for informed consent.

Results

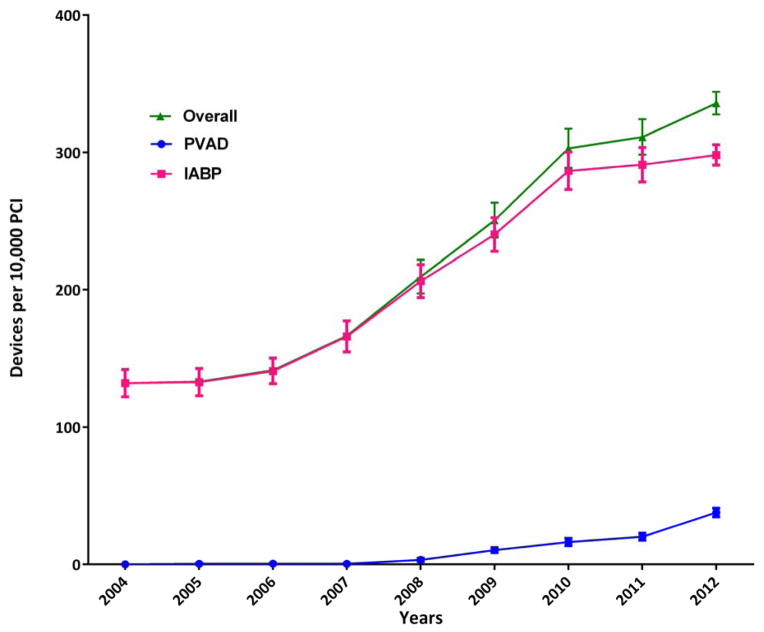

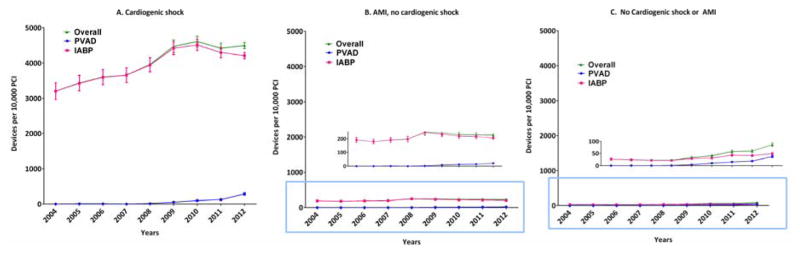

During 2004–2012, we identified 1037 patients who received a PVAD, and 25,519 patients who received an IABP on the same day as PCI in the NIS data, which translates to an estimated 5031 PVAD, and 122,333 IABP procedures in the United States during this period (Figure 1). Overall, a percutaneous MCS device (PVAD or IABP) was used in 2.1% of all PCI patients. Within subgroups, a percutaneous MCS device was used in 40.7% of patients with cardiogenic shock and 2.2% of patients with AMI and no cardiogenic shock. Utilization of MCS increased from 1.3% of all PCIs in 2004 to 3.4% in 2012 (P for trend <0.0001) with simultaneous increase in utilization of both PVADs (less than 1 device per 10,000 PCIs during 2004–2007 to 38 devices per 10,000 PCIs in 2012, P for trend <0.0001) and IABP (132 devices per 10,000 PCIs in 2004 to 299 devices per 10,000 PCIs in 2012, P for trend <0.0001) (Figure 2). Increase in utilization of MCS devices occurred within subgroups of patients with cardiogenic shock, AMI without cardiogenic shock as well as patients without cardiogenic shock or AMI (Figure 3A–3C).

Figure 2.

Calendar-year trends in use of mechanical circulatory support devices, overall and for percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVAD) and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)

Figure 3.

Calendar-year trends in use of mechanical circulatory support devices in patients with (A) cardiogenic shock, (B) AMI, no cardiogenic shock and (C) No cardiogenic shock or AMI

Table 1 summarizes differences in patients who received PVAD compared to IABP on the same day as PCI. Patients who received PVAD were more likely to be older, male, and have CHF, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and diabetes but less likely to have AMI, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, undergo CABG or require mechanical ventilation (P<0.0001 for all, Table 1) compared to IABP recipients. Although length of stay was significantly longer in PVAD patients, the magnitude of difference was small (8.3 days vs. 7.8 days). Compared to IABP recipients, patients who received PVAD on the same day as PCI had lower unadjusted inhospital mortality (20.9% in IABP vs. 12.8% in PVAD, P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient-level characteristics where percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVADs) and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) were used on the same day as percutaneous coronary intervention, National Inpatient Sample 2004 – 2012

| Characteristics | PVAD | IABP | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated number (N)a | 5031 (351) | 122333 (4661) | |

| Mean Age in years (SEM) | 69.0 (0.4) | 64.7 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 64.6 (1.5%) | 50.3 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Male Sex | 74.1 (1.3%) | 69.0 (0.3%) | 0.0002 |

| Race | 0.0243 | ||

| White | 65.7 (2.0%) | 67.4 (1.1%) | |

| Black | 9.1 (1.2%) | 6.1 (0.3%) | |

| Others | 16.2 (1.6%) | 14.9 (0.7%) | |

| Missing/unknown | 8.9 (1.7%) | 11.6 (1.1%) | |

| Income quartilesb | 0.0019 | ||

| 0–25 | 32.9 (2.1%) | 26.3 (1.0%) | |

| 26 to 50 | 25.3 (1.5%) | 25.0 (0.8%) | |

| 51 to 75 | 21.8 (1.5%) | 24.5 (0.6%) | |

| 76 to 100 | 20.1 (2.1%) | 24.2 (1.4%) | |

| Discharge diagnoses/procedures | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 52.5 (1.7%) | 89.7 (0.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 23.3 (1.7%) | 49.6 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 68.5 (1.7%) | 41.3 (0.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 12.2 (1.1%) | 24.7 (0.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 21.6 (1.4%) | 12.7 (0.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 38.4 (1.5%) | 40.6 (0.4%) | 0.16 |

| Prior coronary artery diseasec | 95.2 (0.7%) | 85.2 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 70.6 (1.6%) | 55.8 (0.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 46.5 (1.7%) | 32.3 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemiad | 57.8 (1.6%) | 46.1 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 27.2 (1.5%) | 11.0 (0.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorder | 26.4 (1.6%) | 28.8 (0.6%) | 0.16 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 19.8 (1.3%) | 14.1 (0.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 8.7 (1.0%) | 7.7 (0.3%) | 0.33 |

| Cancer | 9.3 (0.9%) | 7.0 (0.2%) | 0.005 |

| Coagulation disorder | 9.5 (1.0%) | 10.6 (0.3%) | 0.34 |

| Substance-abuse | 1.2 (0.3%) | 1.7 (0.1%) | 0.0310 |

| Coronary bypass | 1.3 (0.3%) | 13.0 (0.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 15.9 (1.2%) | 28.6 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Disposition | <0.0001 | ||

| Home or self-care | 56.3 (1.7%) | 48.6 (0.8%) | |

| Short term hospital | 1.3 (0.4%) | 5.2 (0.3%) | |

| Skilled care facility | 15.8 (1.3%) | 12.9 (0.3%) | |

| Home health care | 13.6 (1.2%) | 12.0 (0.3%) | |

| Against medical advice or unknown | 0.2 (0.1%) | 0.4 (0.04%) | |

| Died | 12.8 (1.2%) | 20.9 (0.5%) | |

| Payment source | <0.0001 | ||

| Medicare | 65.7 (1.7%) | 49.2 (0.5%) | |

| Medicaid | 7.2 (0.8%) | 7.2 (0.3%) | |

| Private insurance | 21.5 (1.5%) | 32.9 (0.5%) | |

| Others | 5.6 (0.8%) | 10.7 (0.3%) | |

| Elective admission | 29.6 (2.0%) | 11.4 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay in days (SEM) | 7.8 (0.3) | 8.3 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 12.8 (1.2%) | 20.9 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation, SEM – standard error of mean

All numbers in the parenthesis represent standard errors, unless otherwise specified

- Estimated numbers obtained after application of patient-level discharge weights

- Median household income quartiles based on patient zip code

- Prior coronary artery disease (CCS code 101) – includes patients with prior documented coronary disease - represented by history of coronary bypass, previous PCI, prior myocardial infarction or angina pectoris. Does not include acute myocardial infarction in index hospitalization

- Dyslipidemia (CCS code 53) – includes any of these - hypercholesterolemia (ICD-9 code – 272.0), hypertriglyceridemia (272.1), mixed hyperlipidemia (272.2), hyperchylomicronemia (272.3) and Other hyperlipidemia (272.4)

Table 2.

Propensity matched analysis of in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with use of percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVADs) or intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP).

| Patient group | Sample size (unweighted) | Unadjusted in-hospital mortality (standard error) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| PVAD | IABP | PVAD | IABP | PVAD | IABP | ||

| Overall | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1037 | 25519 | 12.8 (1.2%) | 20.9 (0.5%) | 0.56 (0.45 – 0.68) | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| After propensity-matching | 1014 | 2026 | 0.88 (0.70 – 1.09) | 1.00 | 0.23 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Cardiogenic shock (CS) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Unadjusted | 243 | 12751 | 38.3 (3.5%) | 31.4 (0.5%) | 1.36 (1.02 – 1.82) | 1.00 | 0.0377 |

| After propensity-matching | 241 | 481 | 1.37 (0.99 – 1.90) | 1.00 | 0.0541 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), no CS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Unadjusted | 336 | 10759 | 8.4 (1.7%) | 11.3 (0.5%) | 0.72 (0.47 – 1.12) | 1.00 | 0.15 |

| After propensity-matching | 336 | 672 | 0.72 (0.46 – 1.14) | 1.00 | 0.16 | ||

|

| |||||||

| No AMI or CS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Unadjusted | 462 | 2126 | 2.6 (0.7%) | 6.6 (0.6%) | 0.37 (0.20 – 0.70) | 1.00 | 0.0017 |

| After propensity-matching | 428 | 856 | 0.54 (0.27 – 1.06) | 1.00 | 0.07 | ||

Using our propensity matching algorithm, we successfully matched 1014 PVAD recipients with 2026 IABP patients. After matching, standardized difference between all measured covariates was < 10% suggesting that propensity matching was successful in achieving covariate balance (Figure 4). In matched analysis, we found no difference in in-hospital mortality in both groups (Odds-ratio [OR] for PVAD group −0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.70 – 1.16, P=0.40, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Standardized differences between covariates before and after propensity matching for percutaneous ventricular assist devices (PVAD) vs. intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The region between dotted lines represents the acceptable range of standardized difference between covariates after propensity matching (0 to 10%). Abbreviations: AMI – Acute myocardial infarction, COPD – Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In patients with cardiogenic shock, unadjusted mortality was higher in the PVAD group (31.4% vs. 38.3%, P = 0.04). However, difference in mortality was non-significant in the propensity-matched analysis (OR – 1.37, 95% CI 0.99 – 1.90) (Table 2). In patients with AMI without cardiogenic shock, mortality in PVAD and IABP patients was similar in both unadjusted (8.4 % vs. 11.3%, P=0.15) and propensity-matched analysis (OR −0.72 95% CI 0.46 – 1.14, P=0.16). In patients without AMI or cardiogenic shock, the unadjusted mortality was lower in the PVAD group (2.6% vs. 6.6%, P=0.0017), but was non-significant in the propensity-matched analysis (OR – 0.5, 95% CI 0.27 – 1.06; P=0.07) (Table 2).

In our sensitivity analysis, upon restricting IABP patients to hospitals with at least 1 PVAD procedure in a given year, similar to our primary analysis, we found lower unadjusted mortality in the PVAD group compared to IABP (12.8% vs 20.6%, P<0.0001) which was not significantly different in propensity-matched analysis (OR for mortality with PVAD −1.00; 95% C.I. 0.79 – 1.26). After further restricting the study cohort to years 2009 through 2012 and to hospitals where at least 1 PVAD was used in a given year, mortality was lower with PVADs in unadjusted analysis (13.3% vs. 20.4 % in IABP, P<0.0001) but was not significant after propensity-matching (OR 1.03, 95% C.I. 0.81 – 1.31).

Discussion

In this study using recent data from a nationally representative database, we found that more than 100,000 patients undergoing PCI received hemodynamic support with either a PVAD or an IABP on the same day as the PCI procedure. Utilization of both IABP and PVAD increased during this period, with greater increase in the use of PVADs in recent years. We found important differences between the PVAD and IABP group with IABP patients more likely to have high acuity conditions (e.g., AMI, cardiogenic shock) and PVAD patients were more likely have chronic co-morbidities (e.g., CHF and CKD). Although in-hospital mortality was lower in PVAD recipients compared to IABP in unadjusted analyses, this difference was no longer present after adjustment for differences in patient characteristics. A number of our findings are important and merit further discussion.

There are several factors that likely contribute to the increasing use of MCS devices in PCI. First, advances in PCI techniques and operator experience have likely expanded the use of PCI in patients who were previously considered to be ‘too high-risk’. Second, patients undergoing high-risk PCI have twice the risk of mortality compared to other PCI patients,2 and maintaining coronary perfusion pressure during high-risk PCI procedures is presumed to be beneficial.6 MCS devices maintain coronary blood flow in patients with tenuous hemodynamics especially during balloon inflation or stent deployment. The BCIS-1 trial showed a significant reduction in intra-procedural hypotension (OR 0.11; 95% CI, 0.01–0.49)10 with the use of IABP during PCI,10 which likely increases operator comfort during complex procedures. Similarly, use of PVADs in PCI is associated with improvement in hemodynamic parameters.11 However, randomized trials have not shown a reduction in PCI-related mortality with the use of either device in PCI and ACC/AHA guidelines recommend their use in high-risk PCI as a Class IIb indication.3 Experts have acknowledged the utility of these devices but have called for studies to guide appropriate use.6

Randomized clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of MCS devices in improving clinical outcomes have revealed mixed results. The BCIS-1 trial revealed no benefit with use of IABP electively prior to high-risk PCI in reducing the rate of major cardiac and cardiovascular events (MACCE) at hospital discharge or risk of mortality at 6 months of follow up.10 However, all-cause mortality at a median 51 month follow up in the elective IABP cohort was lower than the no IABP group (hazard ratio 0.66; 95% C.I. 0.44–0.98), but the cause of death was not known.12 Moreover, a recent meta-analysis of 2123 patients undergoing PCI from 12 randomized trials showed no improvement in 30-day mortality with use of IABP in AMI patients with or without cardiogenic shock (OR: 0.96 95% CI, 0.74–1.24).13 In contrast to the BCIS-1 trial, the IABP-SHOCK II trial assessing use of IABP in AMI with cardiogenic shock did not show a benefit of IABP on all-cause mortality or MACCE at 12 month follow up.14 Although studies have demonstrated that PVADs provide greater hemodynamic support compared to IABP,11, 15, 16 the evidence on improvement in clinical outcomes is weak. The PROTECT II trial, which was powered to evaluate the clinical benefit of PVAD over IABP in the high-risk PCI setting, did not show an improvement in either 30-day or 90-day MACCE rate in the primary intention-to-treat analysis.17 A slight improvement in 90-day outcomes was noted with the use of Impella in per-protocol analysis (40.0% vs. 51.0% with IABP, P=0.023) and in a sub-analysis where the threshold of CK-MB for classification as post-procedure MI was redefined.18 Therefore, there is significant subjectivity in the selection of patients where MCS devices are used during PCI and is likely determined by operator preference or institutional policies.6

Our study adds to the existing body of evidence by evaluating real-world outcomes with MCS for supporting PCI at U.S. hospitals over a 9-year period. We found that while the use of IABP exceeded use of PVAD by more than 20-fold, use of PVAD for supporting PCI is increasing. Moreover, we found that patients receiving PVADs were more likely to be older, admitted electively with higher prevalence of chronic comorbidities where as IABP recipients were more often acutely ill with AMI and cardiogenic shock. It is likely that the greater ease of placement, and more widespread availability of IABPs explains the preferential use of IABPs in acute conditions. In this study, we did not find evidence for a clear benefit of PVADs compared to IABPs among patients undergoing PCI including important patient subgroups (cardiogenic shock, and AMI with or without cardiogenic shock) that were excluded from the PROTECT II study. However, our analyses may be limited due to the observational nature of our study. Since the number of high-risk PCI procedures requiring the use of MCS devices is likely to rise, further evidence from randomized controlled studies is needed to guide selection of patients undergoing PCI, who might benefit from one MCS device over another, given the incremental cost and risk of complications associated with the use of PVADs over IABP.19 Given its administrative design, it is unclear if some of the recent rise in MCS utilization in PCI represents overuse in low-risk patients, and would be best evaluated in a dedicated future study.

Our study has several limitations. First, in order to capture concurrent use of MCS for supporting PCI, we only included patients who received PVAD or IABP the same day as their PCI procedure in this study. However, since data regarding the time of procedure is not available in NIS, it is possible that we included some patients who received PVAD or IABP following PCI (on the same day) due to occurrence of procedural complications. Second, we cannot distinguish Impella from TandemHeart, since both share the same ICD-9 code. However, Impella devices represent a majority of devices used in clinical practice.5, 19 Moreover, in the PCI setting both Impella and TandemHeart have been shown to have comparable efficacy and complication rates.20 Third, while we used propensity-matched analysis to account for confounding due to indication (selection bias), and our matching algorithm was successful in achieving covariate balance, information on important patient characteristics (e.g., coronary anatomy, left ventricular ejection fraction, etc.) was not available. Therefore, there is potential for residual confounding due to unmeasured variables. Fourth, given the administrative nature of the database we cannot reliably differentiate between pre-existing conditions from conditions arising out of complications of hospitalization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award K08HL122527 (Dr. Girotra).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Horwitz receives grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, St Jude Medical, and Biotronik. None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan JM, Curtis JP, Dai D, Fitzgerald S, Khandelwal AK, Spertus JA, Rao SV, Singh M, Shaw RE, Ho KK, Krone RJ, Weintraub WS, Weaver WD, Peterson ED National Cardiovascular Data R. Enhanced mortality risk prediction with a focus on high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: results from 1,208,137 procedures in the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:790–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, Khot UN, Lange RA, Mauri L, Mehran R, Moussa ID, Mukherjee D, Nallamothu BK, Ting HH American College of Cardiology F, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G, Society for Cardiovascular A and Interventions. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werdan K, Gielen S, Ebelt H, Hochman JS. Mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:156–167. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khera R, Cram P, Lu X, Vyas A, Gerke A, Rosenthal GE, Horwitz PA, Girotra S. Trends in the use of percutaneous ventricular assist devices: analysis of national inpatient sample data, 2007 through 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:941–950. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rihal CS, Naidu SS, Givertz MM, Szeto WY, Burke JA, Kapur NK, Kern M, Garratt KN, Goldstein JA, Dimas V, Tu T Society for Cardiovascular A, Interventions Heart Failure Society of A, Society of Thoracic S American Heart A, American College of C. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS Clinical Expert Consensus Statement on the Use of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiovascular Care: Endorsed by the American Heart Assocation, the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencion; Affirmation of Value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:e7–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houchens R, et al. HCUP Method Series Report # 2003-02. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed 5/13/2014]. 2005. Final Report on Calculating Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Variances, 2001. ONLINE June 2005 (revised June 6, 2005) Available: http://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/CalculatingNISVariances200106092005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Premarket Notification. 2008 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf6/K063723.pdf.

- 10.Perera D, Stables R, Thomas M, Booth J, Pitt M, Blackman D, de Belder A, Redwood S, Investigators B. Elective intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjauw KD, Konorza T, Erbel R, Danna PL, Viecca M, Minden HH, Butter C, Engstrom T, Hassager C, Machado FP, Pedrazzini G, Wagner DR, Schamberger R, Kerber S, Mathey DG, Schofer J, Engstrom AE, Henriques JP. Supported high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention with the Impella 2. 5 device the Europella registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2430–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perera D, Stables R, Clayton T, De Silva K, Lumley M, Clack L, Thomas M, Redwood S, Investigators B. Long-term mortality data from the balloon pump-assisted coronary intervention study (BCIS-1): a randomized, controlled trial of elective balloon counterpulsation during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2013;127:207–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.132209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad Y, Sen S, Shun-Shin MJ, Ouyang J, Finegold JA, Al-Lamee RK, Davies JE, Cole GD, Francis DP. Intra-aortic Balloon Pump Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:931–939. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, Ferenc M, Olbrich HG, Hausleiter J, de Waha A, Richardt G, Hennersdorf M, Empen K, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, Hambrecht R, Lauer B, Bohm M, Ebelt H, Schneider S, Werdan K, Schuler G Intraaortic Balloon Pump in cardiogenic shock IIti. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (IABP-SHOCK II): final 12 month results of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1638–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon SR, Henriques JP, Mauri L, Sjauw K, Civitello A, Kar B, Loyalka P, Resnic FS, Teirstein P, Makkar R, Palacios IF, Collins M, Moses J, Benali K, O’Neill WW. A prospective feasibility trial investigating the use of the Impella 2.5 system in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (The PROTECT I Trial): initial U.S experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I, Frohlich G, Bott-Flugel L, Byrne R, Dirschinger J, Kastrati A, Schomig A. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1584–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neill WW, Kleiman NS, Moses J, Henriques JP, Dixon S, Massaro J, Palacios I, Maini B, Mulukutla S, Dzavik V, Popma J, Douglas PS, Ohman M. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2. 5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the PROTECT II study. Circulation. 2012;126:1717–1727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.098194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dangas GD, Kini AS, Sharma SK, Henriques JP, Claessen BE, Dixon SR, Massaro JM, Palacios I, Popma JJ, Ohman M, Stone GW, O’Neill WW. Impact of hemodynamic support with Impella 2. 5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump on prognostically important clinical outcomes in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (from the PROTECT II randomized trial) Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah AP, Retzer EM, Nathan S, Paul JD, Friant J, Dill KE, Thomas JL. Clinical and economic effectiveness of percutaneous ventricular assist devices for high-risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2015;27:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacic JC, Nguyen HT, Karajgikar R, Sharma SK, Kini AS. The Impella Recover 2. 5 and TandemHeart ventricular assist devices are safe and associated with equivalent clinical outcomes in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:E28–37. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.