Abstract

PURPOSE

To investigate the efficacy and safety of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer-dexamethasone conjugate (P-Dex) in the collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mouse model.

METHODS

HPMA copolymer labeled with a near infrared fluorescence (NIRF) dye was administered to mice with CIA to validate its passive targeting to inflamed joints and utility as a drug carrier system. The CIA mice were treated with P-Dex, dexamethasone (Dex) or saline and the therapeutic efficacy and skeletal toxicity evaluated using clinical scoring and micro-computed tomography (µ-CT).

RESULTS

The NIRF signal of the HPMA copolymer localized to arthritic joints consistent with its passive targeting to sites of inflammation. While the CIA mice responded more rapidly to P-Dex compared to Dex, the final clinical score and endpoint µ-CT analyses of localized bone erosions indicated that both single dose P-Dex and dose equivalent daily Dex led to comparable clinical efficacy after 30 days. µ-CT analysis of the proximal tibial metaphyses showed that P-Dex treatment was associated with significantly higher BMD and BV/TV compared to Dex and the saline control, consistent with reduced glucocorticoid (GC) skeletal toxicity.

CONCLUSION

These results validate the therapeutic efficacy of P-Dex in the CIA mouse model. P-Dex treatment averted the adverse effects of GC’s on systemic bone loss, supporting its utility in clinical development for the management of rheumatoid arthritis.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid, prodrug, HPMA copolymer, collagen-induced arthritis, ELVIS

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of methotrexate and leflunomide and the development of new biologic therapies targeting inflammatory cytokines and immune cell subsets have improved the outcomes and quality of life for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Nevertheless, over one third of the RA population continues to experience joint inflammation and progressive joint damage [1,2]. Recent studies have shown that the addition of systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) to the existing treatment regimens markedly enhances the clinical outcomes. However, the lack of tissue specificity and associated systemic toxicity of GCs has limited their widespread use as an adjuvant therapy and there is a need for a selective glucocorticoid agonist with specificity for inflamed joints with limited non-target organ systemic toxicity [3].

Our team has developed an acid-labile arthrotropic macromolecular dexamethasone prodrug based on N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer (P-Dex) [4], and demonstrated its superior anti-inflammatory efficacy compared with an equivalent dose of free dexamethasone (Dex) in the rat adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) model [5]. The arthrotropism and local retention of P-Dex were attributable to the enhanced vascular permeability in arthritic joints and the internalization of P-Dex by synovial cells, which we have termed extravasation through leaky vasculature and inflammatory cell-mediated sequestration (ELVIS) [6]. The present studies were undertaken to provide further validation of the clinical efficacy of the prodrug in an additional model of RA, since the AA model of inflammatory arthritis does not completely replicate the human disease. Secondly, the joint inflammation and damage in the AA model is transient and normally undergoes resolution after one month [7]. This duration is not long enough for the detection of long-term GC toxicity on the skeleton. Thirdly, in the previous study, we used histological examination of ankle joints to assess inflammation and bone and cartilage loss. Histologic analyses provided information on the cellularity and dynamic indices of bone remodeling but did not provide data regarding peri-articular and systemic trabecular bone microarchitecture, which are important determinants of the quantitative as well as qualitative status of bone architecture [8]. In the present studies we utilized high-resolution 3D imaging techniques with micro-CT, which directly measures bone microarchitecture without relying on any stereologic models involved in 2D histologic analysis.

In current study, we have examined the therapeutic efficacy of P-Dex in the collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model and compared the long-term effects P-Dex compared to free Dex on clinical signs of joint inflammation. Micro-CT was used to assess the microstructure of the calcaneus and proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM) to compare the effects of the treatments on peri-articular and systemic bone architecture.

Materials and Methods

Murine CIA model and clinical assessment

Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) was induced in DBA/1J mice of 7 to 8 weeks (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) by immunizing the animals with type II collagen in Freund’s adjuvant on day(s) 0 and 21 [9]. Following the day 21-booster injection, the mice were regularly monitored for the development and severity of paw inflammation. Each paw was individually scored as follows: 0 = Normal; 1 = one toe inflamed and swollen; 2 = more than one toe, but not entire paw, inflamed and swollen, or mild swelling of entire paw; 3 = entire paw inflamed and swollen; 4 = maximally inflamed paw with ankylosis [9,10]. Scores for all 4 paws were summed for each mouse, and the mean score for each group was calculated. The ankle diameter (medial to lateral) was measured using a digital caliper (World Prescision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA) on a weekly basis.

Mice with established arthritis (at least one paw achieving a score of 2) were randomly assigned into three groups (6/group). A fourth healthy, untreated group was included as control. P-Dex (equivalent Dex dose = 60 mg/kg) was administered via tail vein injection to one group of the CIA mice. An equivalent total dose of water-soluble free Dex (dexamethasone sodium phosphate) was divided into 30 aliquots and administered as intraperitoneal injections to the second group of mice on a daily basis. Saline was similarly given to the third group of mice as a control. The arthritic scores of all 4 paws were monitored for one month, as described above.

All animal experiments were performed according to a protocol approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Institutes of Health publication 85-23, revised in 1985).

Synthesis of HPMA copolymer-dexamethasone conjugate (P-Dex)

P-Dex was synthesized by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) copolymerization as described previously [5]. Briefly, N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA, 444 mg, 3.1 mmol) and N-methacryloylglycylglycylhydrazyl dexamethasone (MA-Dex, 128 mg, 0.22 mmol) were copolymerized at 50 °C under Argon for 48 hr with 2,2’-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 2.7 mg, 16.4 µmol) as the initiator and S,S’-bis(α, α’-dimethyl-α”-acetic acid) trithiocarbonate (CTA, 2.36 mg, 8.9 µmol) as the RAFT agent. The resulting polymer were purified by LH-20 column (GE HealthCare, Waukesha, WI) to remove unreacted monomers, dialyzed and then lyophilized to yield 290 mg of P-Dex. After complete hydrolysis by HCl, the Dex content in the copolymer was determined as 92 mg/g of P-Dex. No free Dex was detectable by HPLC (Agilent 1100 HPLC system, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The FPLC (GE HealthCare, Piscataway, NJ) analysis results showed that the average molecular weight (Mw) of P-Dex was 36 kDa with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.4 using HPMA homopolymers for calibration.

Synthesis of IRDye 800CW-Labeled HPMA Copolymer (P-IRDye)

N-3-Aminopropyl methacrylamide (APMA)-containing polymer, poly (HPMA-co-APMA), was synthesized as previously described [11]. The product was purified by LH-20 column (GE HealthCare, Piscataway, NJ) to remove the unreacted low molecular weight compounds and then lyophilized. The amine content of the copolymer was determined as 5.5 ×10−5 mol/g using the ninhydrin assay [11]. The FPLC (GE HealthCare, Piscataway, NJ) analysis results showed that the Mw of P-IRDye was 37 kDa with a PDI of 1.3.

Poly(HPMA-co-APMA) (15.6 mg, containing 0.86 µmol of primary amine) and IRDye 800CW NHS ester (0.5mg, 0.43 µmol, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) were dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF, 400 µL) with N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 10 µL). The solution was stirred overnight in darkness at room temperature. The product was then purified on a LH-20 column and lyophilized. The IRDye 800CW content was determined as 1.2 ×10−5 mol/g using a Lambda 10 UV/vis spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT).

Near Infrared Fluorescence (NIRF) Optical Imaging

The in vivo NIRF imaging was performed on mice with established arthritis. Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in oxygen throughout all procedures. After acquisition of a background image, the mice were given a bolus injection of P-IRDye (100 nmol of IRDye 800CW equivalence per kilogram body weight) via tail vein. Mice were imaged at 2 h, 5 h, 1d, 3d, and 7 d post-injection. The imaging was accomplished using a 200 Series XENOGEN IVIS Imaging System (Hopkinton, MA). A laser source produced light at wavelengths of 785 nm for illumination of the entire animal in a light-proof box inside the device. The emitted fluorescence signals were detected with an intensified charge-coupled device camera. Image acquisition and analysis were performed with the Living Imaging 2.0 software.

Micro-CT analysis

Mice were sacrificed 1-month post treatment and both hind limbs were isolated and fixed. Each hind limb (ankle) was scanned and reconstructed into a 3D-structure using micro-CT (Skyscan 1172, Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium) with a voxel size of 4.8 µm. The X-ray tube voltage was 60 kV and the current was 170 µA, with a 0.5 mm thick Al filter. Exposure time was 530 ms. The X-ray projections were obtained at 0.7° intervals with a scanning angular rotation of 180° and six frames were averaged for each rotation. 3D reconstructions were performed using NRECON (Skyscan) software. Calcaneus (heel) bone was analyzed to quantify bone erosion while proximal tibial metaphysic (PTM) was analyzed to evaluate the effects of Dex on systemic bone architecture.

The final analyses were done on a volume of interest (VOI) of 75 slides, for which a constant spherical (0.55mm × 0.55mm) region of interest (ROI) was defined and placed centrally in the trabecular region of the calcaneus. Specific threshold settings were used and kept constant for all samples. The following parameters were measured and calculated: bone mineral density (BMD) of trabecular bone, bone volume (BV), bone volume to tissue volume or bone volume density (BV/TV), bone surface to tissue volume or bone surface density (BS/TV), trabecular number (Th. N), and trabecular separation (Tb. Sp). 3D images were reconstructed using CT-Vox and CT-Vol software (Skyscan) to produce a visual representation of the results.

Statistical methods

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was done by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni/Tamhane’s T2 test as a post-hoc test. Differences between groups are indicated as significant (p < 0.05) or non-significant (NS).

Results

Clinical evaluation of CIA disease course

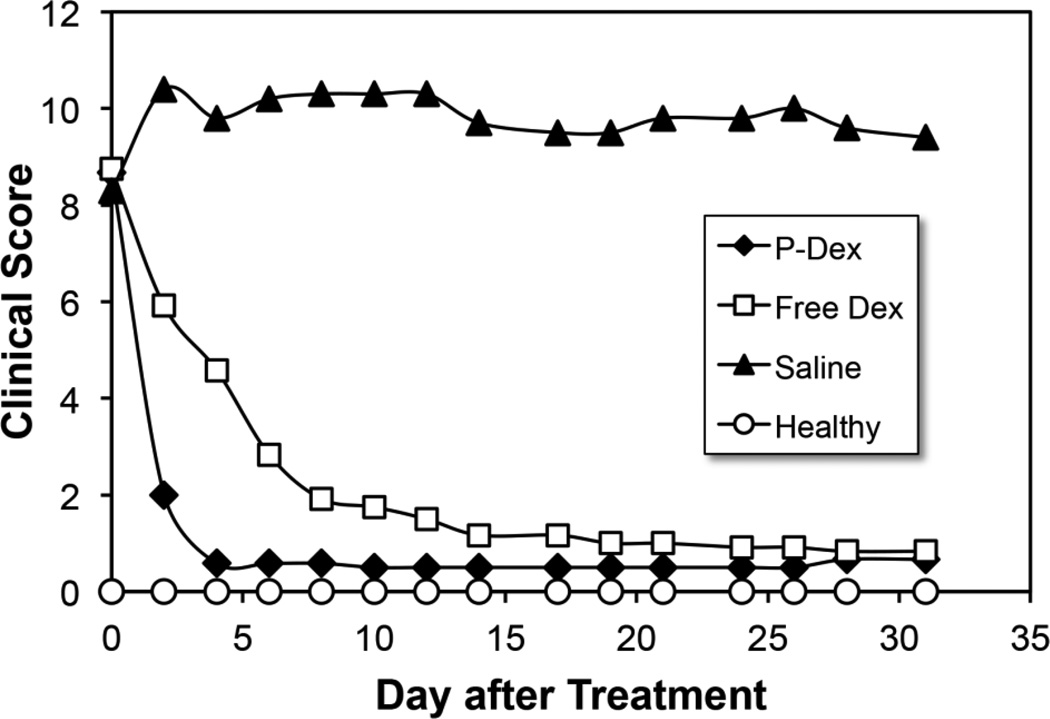

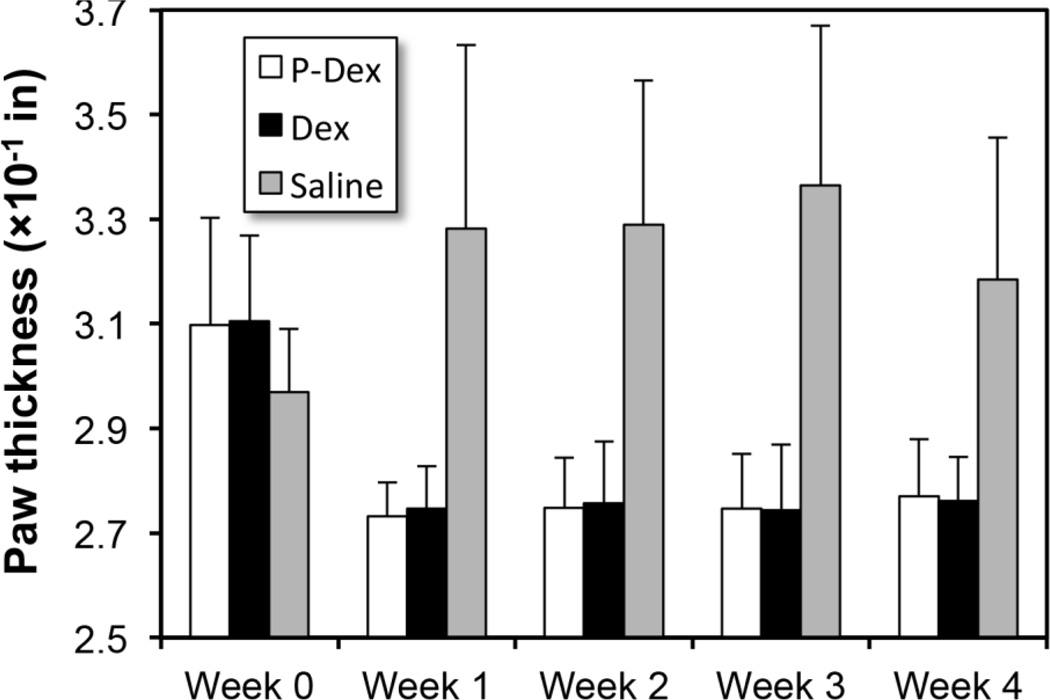

As can be seen in Figure 1, both free Dex and P-Dex treatments resulted in paw/joint inflammation resolution, with the P-Dex treated animals responding more rapidly to the treatment compared to the free Dex group. One injection of P-Dex led to the inhibition of clinical signs of disease during the entire disease course, which was comparable to the inhibitory effect of an equivalent daily dose of free Dex. Consistent with the clinical scoring, measurements of paw swelling indicated that both P-Dex and free Dex were highly effective in reducing joint inflammation. For both groups, caliper measurements did not increase from week 1 through week 4 (Figure 2). On day 31 post-treatment, one mouse in P-Dex group showed evidence of joint inflammation.

Figure 1.

Clinical scores of the P-Dex, Dex and saline treated groups of mice with CIA and healthy controls. Scores for all four paws were summed for each mouse. Error bars have been omitted for clarity of presentation.

Figure 2.

The effect of P-Dex, Dex, saline on paw swelling in the CIA mice.

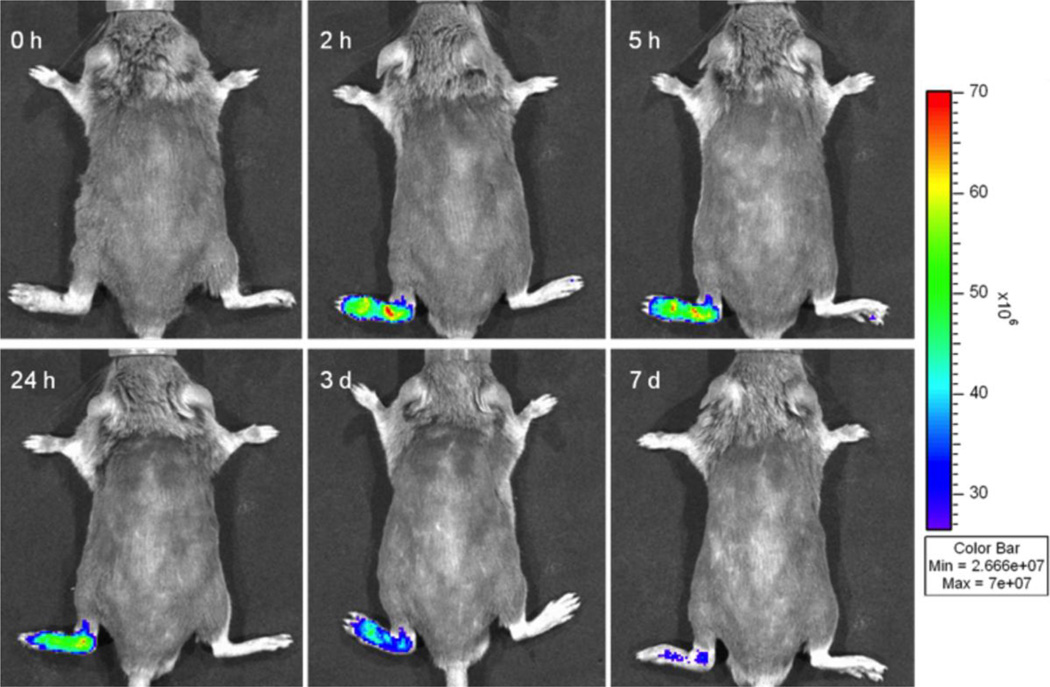

NIRF imaging

Prior to the injection of IRDye 800CW-labeled HPMA copolymer conjugate, no background signal was detectable in either healthy or arthritic limbs (Figure 3). After the injection, a visible NIRF signal was detected in the arthritic limbs. Imaging at 2 h post injection showed peak fluorescence signals in the arthritic limbs. The signal intensity was generally retained with a slow decline thereafter. At 7 days post injection, the fluorescence signals were still clearly detectable. No signal was detected in the non-arthritic limbs.

Figure 3.

Representative in vivo NIRF imaging of mice at different time points post-injection of IRDye CW 800-labeled HPMA conjugate (P-IRDye). The mouse had one arthritic limb (left hind) and three non-arthritic limbs. Persistent NIR fluorescence signals were detected only in arthritic limb, consistent with targeting and retention of the polymeric carrier in the arthritic joint.

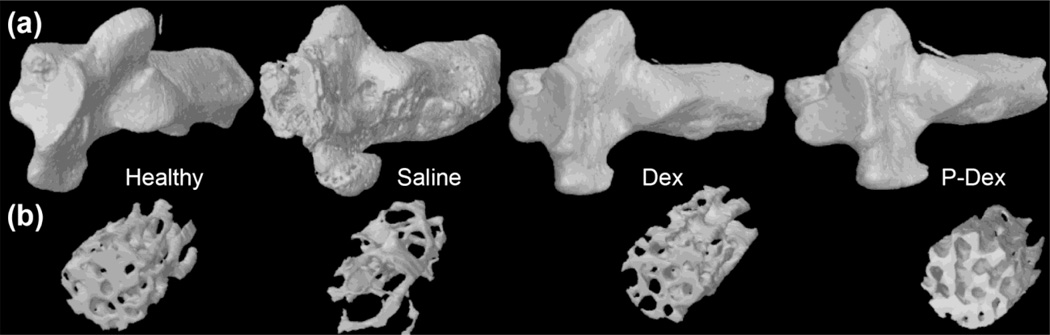

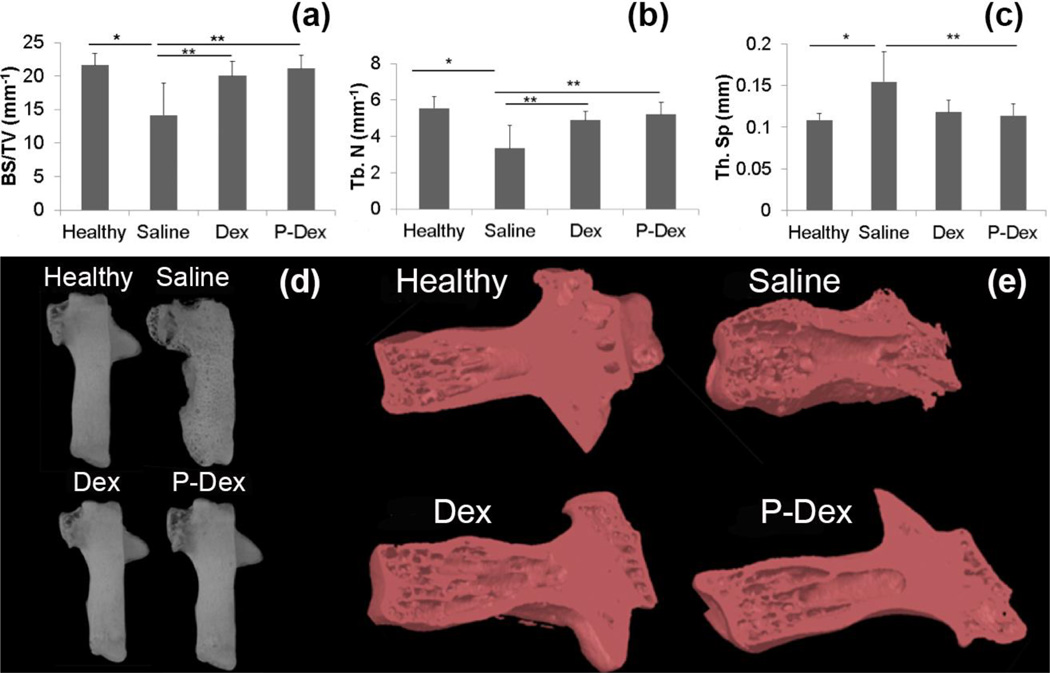

Micro-CT analysis of the calcaneus

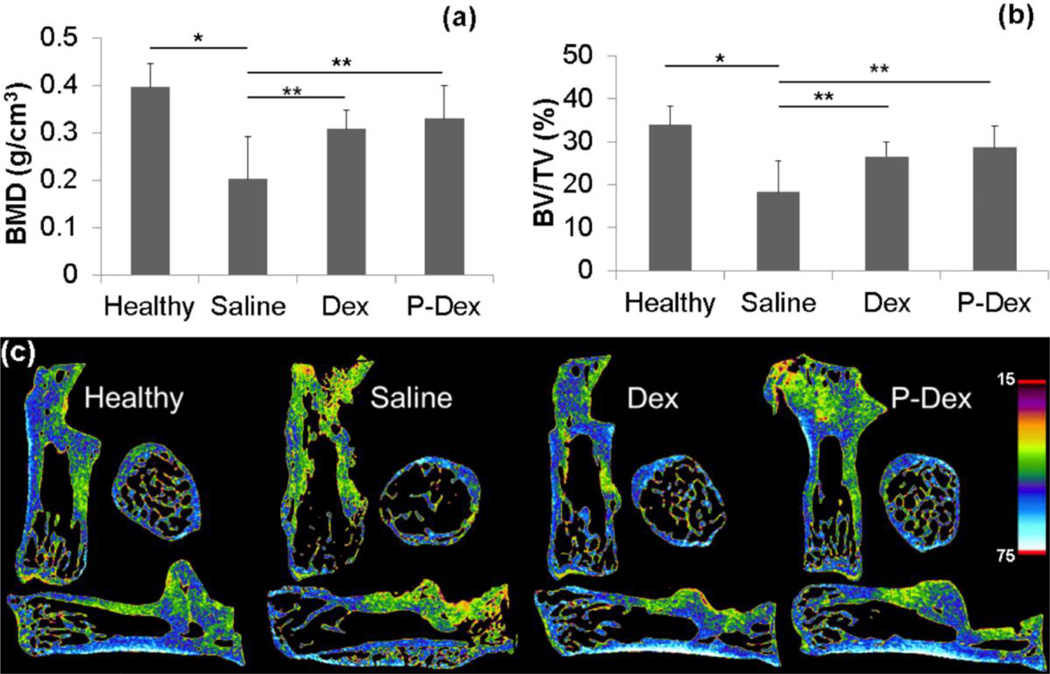

We first assessed the effects of treatment on BMD in the calcaneus using micro-CT. BMD was significantly higher in mice treated with Dex (0.30 ± 0.04 g/cm3, p=0.012) and P-Dex (0.33 ± 0.07 g/cm3, p=0.001) vs saline (0.20 ± 0.09 g/cm3) (Fig.4a and 4c). BV/TV (%) also differed significantly between saline (18.27 ± 7.18) vs Dex (26.57 ± 3.25, p=0.004) and P-Dex (28.63 ± 4.99, p<0.001) (Fig. 4b, 4c and 5b).

Figure 4.

Micro-CT analysis of the calcaneus in CIA mice after different treatments. Graphical representation of the BMD (a) and BV/TV (b) values among all the treatment groups. Density changes among all the treatment groups are as visualized in images from Data viewer in all three planes i.e. coronal, transaxial and saggital planes (c), using color-coded bar. Blue color with higher number represents bone with higher density.

Figure 5.

Micro-CT analysis of the calcaneus in CIA mice from the different treatment groups. 3D-reconstructed images of the calcaneus (a). Note the eroded bone surface in the untreated group, which is reverted back to normal in treatment groups. 3D representation of the trabecular bone analyzed inside the calcaneus (b).

Bone surface density (BS/TV) was used to measure surface roughness/erosion. The saline (14.17 ± 4.78 mm−1) group showed significant erosion/roughness compared to the healthy control (21.62 ± 1.78 mm−1, p=0.004) group. Dex (20.06 ± 2.13 mm−1, p=0.022, +42%) and P-Dex (21.15 ± 1.97 mm−1, p=0.007, +49%) groups showed significant preservation of bone and joint integrity compared to the saline treated group (Fig. 5 and 6). The preserved density and volumetric changes in the treatment groups were attributable to the trabecular structural architecture, i.e. increase in Tb. N and decrease in Tb. Sp, as shown in Fig. 6b, 6c and 6e. For mean Tb.N, significant differences were found in Dex (4.90 ± 0.49 mm−1, p=0.021, + 46%) and P-Dex (5.22 ± 0.67 mm−1, p=0.006, + 56%) vs saline (3.35 ± 1.26 mm−1). Tb.Sp differed among the groups, Dex (0.12 ± 0.014 mm, p=0.069 (NS), − 20%) and P-Dex (0.11 ± 0.014 mm, p=0.036, − 27%) vs saline (0.15 ± 0.036 mm) (Fig.5b and 6).

Figure 6.

Micro-CT analysis of the calcaneus in CIA mice from the different treatment groups. (a), (b) and (c) show the differences among groups for BS/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp respectively. (d) Images from CT-Vox between the groups. Note the increased porosity, eroded surface and exaggerated periosteal reaction of the untreated group. (e) 3D coronal cuts using CT-Vol, to have a visual representation of bony architecture inside the calcaneus.

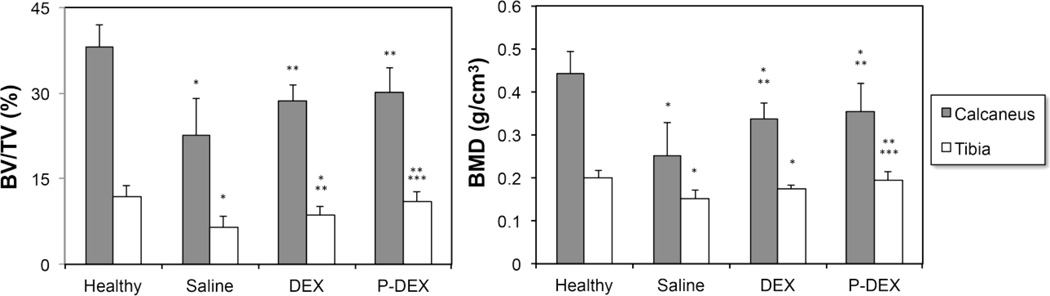

Micro-CT analysis of proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM)

Bone quality at a peripheral site (e.g. PTM), was analyzed by micro-CT. Consistent with the calcaneus assessment, both P-Dex and free Dex groups had significantly better BMD and BV/TV values than the untreated saline group. However, unlike the calcaneus, where P-Dex and Dex had equivalent effects on bone preservation, PTM analysis (Figure 7) showed that the P-Dex group had significantly higher BMD (0.19 ± 0.02 g/cm3) than the free Dex (0.17 ± 0.01 g/cm3, p = 0.01) treatment group. Similarly, higher BV/TV (%) value was also observed with P-Dex treatment (11.10 ± 1.58) than free Dex (8.61 ± 1.51, p = 0.001).

Figure 7.

Comparison of BMD and BV/TV measurement of calcaneus and proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM) in four groups. *Significantly different from healthy control group, p < 0.05; **Significantly different from saline group, p < 0.05; *** Significantly different from free Dex group, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Previously, our team has developed a macromolecular dexamethasone prodrug based on N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer (P-Dex) [5] and has provided evidence demonstrating its superior anti-inflammatory efficacy compared with an equivalent dose of free dexamethasone (Dex) using the adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) model [4–6]. Although AA is a validated model for assessing the effects of therapeutic interventions on joint tissues and structures, it has several limitations [7]. First, in the AA model, the cartilage damage is relatively limited compared to human RA. Secondly, the joint inflammation and damage in the AA model is transient and undergoes spontaneous resolution within 4–6 weeks [7]. This duration is not long enough for the detection of long-term GC toxicity on the skeleton. In addition, the immunologic disease mechanism differs from RA in that the susceptibility to adjuvant-induced disease is not associated with genes encoding major histocompatibility class II molecules. This model is also T cell and neutrophil dependent with no requirement for B cells [7,12]. The present studies were therefore undertaken to investigate the efficacy of P-Dex in an additional animal model that more accurately recapitulates the features of human RA and importantly is associated with a more protracted disease course permitting the assessment of the long-term effects of GCs on local and systemic skeletal architecture.

In the CIA model, arthritis is induced in mice by immunization with autologous or heterologous type II collagen in adjuvant [7,12]. Susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis is strongly associated with major histocompatibility complex class II genes, and the development of arthritis is accompanied by a robust T- and B-cell response to type II collagen. The chief pathological features of CIA include a proliferative synovitis with infiltration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells, pannus formation, cartilage degradation, erosion of bone, and fibrosis. In recent years, the CIA model has been instrumental in the testing and development of the new biologically based therapeutics that have revolutionized the treatment of RA and for these reasons we have extended studies to the evaluation of the efficacy and safety of P-Dex in the CIA model.

To confirm the arthrotropism of HPMA copolymer as a drug carrier in CIA mice, the IRDye labeled polymer (P-IRDye) was administered to the animals via tail vein injection and followed by a series of optical imaging studies. Unlike the AA model in which most limbs are involved, CIA mice may have arthritic joints in one to four limbs. Therefore, we were able to select a CIA mouse with a single diseased limb, and use the other three non-arthritic limbs as an internal control. We observed that P-IRDye demonstrated strong arthrotropism exclusively to the inflamed joints, which agrees with our previous joint-targeting capability of DOTA/Gd3+-labeled HPMA copolymer using an MRI imaging technique in the AA model [4]. Moreover, P-IRDye accumulated more extensively in severely inflamed joints compared to minimally inflamed joints (data not shown). These results support the utility of the HPMA copolymer as a drug carrier platform to deliver therapeutic agents to arthritic joints.

In the treatment study in the CIA model, P-Dex (containing 60 mg Dex/kg animal) was administered as one bolus injection, while an equivalent dose of free Dex was given on a daily basis (2 mg/kg per day). A single injection of P-Dex led to almost complete resolution of joint inflammation for a month. In the previous AA treatment study, a 4-day free Dex treatment schedule only ameliorated the joint inflammation for a short period after which the arthritis worsened immediately upon cessation of free Dex administration [5]. In the current study, free Dex was administered on a daily basis until the end of the experiment. Overall, a single P-Dex treatment and dose equivalent daily free Dex treatment provided similar amelioration of the arthritis. However, we observed that the animals demonstrated a more rapid reduction in joint inflammation with the P-Dex treatment compared to the free Dex treatment. We speculate that the differential effect may be related to the enhanced arthotropism of the P-Dex compared to free Dex. Additionally, the synoviocyte cell uptake, sequestration and subsequent release of Dex by subcellular processing, which we have demonstrated in our previous studies, could provide a sustained local concentration of Dex in the inflamed tissues thereby enhancing its therapeutic efficacy. In contrast to the P-Dex, the large volume of distribution and rapid clearance of the free Dex could result in a less favorable local joint concentration compared to the P-Dex.

In our studies we employed 3-D micro-CT imaging to analyze trabecular bone microarchitecture, which permits quantitative assessment of bone loss and microarchitecture. To assess the effects of synovial inflammation on joint structure, we specifically focused on the calcaneus, as it is spatially isolated from other bones of the ankle and is of sufficient size and relatively uniform in density and consistently is involved in the arthritic joint process. Consistent with the improved clinical scoring and reduced inflammation, calcaneal BMD and BV/TV were significantly higher in the mice treated with P-Dex and free Dex compared to the saline group. Assessment of bone surface density (BS/TV), which provides information concerning the presence of bone erosions, revealed that both the free Dex and P-Dex treatment groups showed significantly higher BS/TV compared to the saline group, consistent with preservation of bone and joint integrity and prevention of osteoclast-mediated bone erosion. These conclusions were also supported by the observed increase in Tb. N and decrease in Tb. Sp in the P-Dex and free Dex treatment groups.

Systemic administration of GCs is associated with a marked increase in osteoporosis and an increased fracture risk. These complications are observed, even in individuals receiving relatively lose dose GCs [13–17]. We developed the P-Dex system with the goal of creating a unique drug carrier system that could preferentially localize and retain the GC at the sites of joint inflammation and pathology while avoiding general exposure of the skeleton and non target organs to the potential long-term toxicities of GCs. To assess the effects of the P-Dex and free Dex on the noninvolved skeletal sites, we selected the proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM) for the micro-CT analysis. The saline treatment group had significantly lower BMD and BV/TV values compared to the healthy controls, consistent with the adverse effects of the local joint inflammation on the overall skeletal homeostasis. While daily high-dose free Dex treatment effectively ameliorated joint inflammation and reduced local peri-articular bone loss, it was associated with reduced BMD values in the PTM. In contrast, a single administration of P-Dex led to significantly higher BMD and BV/TV values compared to the free Dex treated and saline treated controls, consistent with protection from the adverse systemic effects of Dex on skeletal homeostasis. These results complement our earlier studies in which we evaluated the efficacy of P-Dex in the AA model of RA and in other models of local bone destruction [18–20], and show that systemically administered P-Dex can effectively target sites of bone pathology associated with inflammation and suppress the bone resorptive and inflammatory process while averting the adverse effects of GCs on the general skeleton.

Conclusion

The present study in the CIA model of RA extends our previous observations demonstrating the therapeutic efficacy of a HPMA copolymer-based dexamethasone prodrug (P-Dex) in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. Importantly, P-Dex was able to circumvent the adverse effects of GC on general skeletal homeostasis. Collectively, based on the clinical efficacy and reduced systemic toxicity of P-Dex, these data in combination with our previous findings in the AA rat model support the development of P-Dex as a novel therapeutic for the treatment of RA.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 AR053325 and Nebraska Arthritis Outcome Research Center (NAORC). We thank Mr. Arun Tatiparthi of Micro Photonics for his assistance with the micro-CT analysis. Y.Z. was supported by the Bukey Fellowship from University of Nebraska Medical Center.

ABBREVIATION

- AA

adjuvant-induced arthritis

- AIBN

2,2’-azobisisobutyronitrile

- BS/TV

bone surface to tissue volume or bone surface density

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BV/TV

bone volume to tissue volume or bone volume density

- CIA

collagen-induced arthritis

- Dex

dexamethasone

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- ELVIS

extravasation through leaky vasculature and inflammatory cell-mediated sequestration

- GC

glucocorticoid

- HPMA

N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide

- MA-Dex

N-methacryloylglycylglycylhydrazyl dexamethasone

- Mw

weight average molecular weight

- NIRF

near infrared fluorescence

- NS

non-significant

- P-Dex

dexamethasone prodrug based on N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer

- PDI

polydispersity index

- PTM

proximal tibial metaphysis

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RAFT

reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer

- ROI

region of interest

- Tb. Sp

trabecular separation

- Th.N

trabecular number

- VOI

volume of interest

REFERENCE

- 1.Klareskog L, Catrina AI, Paget S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2009 Feb 21;373(9664):659–672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60008-8. PubMed PMID: 19157532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Vollenhoven RF. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: state of the art 2009. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2009 Oct;5(10):531–541. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.182. PubMed PMID: 19798027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Buttgereit F, Bijlsma JW. Current view of glucocorticoid co-therapy with DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Dec;6(12):693–702. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.179. PubMed PMID: 21119718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D, Miller SC, Liu XM, Anderson B, Wang XS, Goldring SR. Novel dexamethasone-HPMA copolymer conjugate and its potential application in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2007;9(1):R2. doi: 10.1186/ar2106. PubMed PMID:17233911. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1860059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu XM, Quan LD, Tian J, Alnouti Y, Fu K, Thiele GM, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of a well-defined HPMA copolymer-dexamethasone conjugate for effective treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmaceutical research. 2008 Dec;25(12):2910–9. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9683-3. PubMed PMID: 18649124. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2593120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan LD, Purdue PE, Liu XM, Boska MD, Lele SM, Thiele GM, et al. Development of a macromolecular prodrug for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis: mechanisms involved in arthrotropism and sustained therapeutic efficacy. Arthritis research & therapy. 2010;12(5):R170. doi: 10.1186/ar3130. PubMed PMID: 20836843. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2990997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waksman BH. Immune regulation in adjuvant disease and other arthritis models: relevance to pathogenesis of chronic arthritis. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2002 Jul;56(1):12–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01106.x. PubMed PMID: 12100468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Journal of bone and mineral research. 1987 Dec;2(6):595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. PubMed PMID: 3455637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand DD, Latham KA, Rosloniec EF. Collagen-induced arthritis. Nature protocols. 2007;2(5):1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.173. PubMed PMID: 17546023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeuws S, Jacques P, Van Praet J, Drennan M, Coudenys J, Decruy T, et al. A multiparameter approach to monitor disease activity in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2010;12(4):R160. doi: 10.1186/ar3119. PubMed PMID: 20731827. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2945063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren K, Purdue PE, Burton L, Quan LD, Fehringer EV, Thiele GM, et al. Early detection and treatment of wear particle-induced inflammation and bone loss in a mouse calvarial osteolysis model using HPMA copolymer conjugates. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2011 Aug 1;8(4):1043–1051. doi: 10.1021/mp2000555. PubMed PMID: 21438611. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3148351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bendele AM. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2001 Jun;1(4):377–385. PubMed PMID: 15758488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001 Feb 14;285(6):785–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. PubMed PMID: 11176917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A, Capelli G, de Feo D, Giannini S, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone. 2006 Aug;39(2):253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.02.005. PubMed PMID: 16574519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein RS. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2001 Jan;2(1):65–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1010007108155. PubMed PMID: 11708295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathogenesis and management. Annals of internal medicine. 1990 Mar 1;112(5):352–364. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-5-352. PubMed PMID: 2407167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein MF, Fallon JJ, Jr, Harning R. Chronic glucocorticoid therapy-induced osteoporosis in patients with obstructive lung disease. Chest. 1999 Dec;116(6):1733–1749. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1733. PubMed PMID: 10593801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan F, Quan LD, Cui L, Goldring SR, Wang D. Development of macromolecular prodrug for rheumatoid arthritis. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012 Sep;64(12):1205–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.03.006. PubMed PMID: 22433784. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3572768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan L, Zhang Y, Crielaard BJ, Dusad A, Lele SM, Rijcken CJ, et al. Nanomedicines for inflammatory arthritis: head-to-head comparison of glucocorticoid-containing polymers, micelles, and liposomes. ACS nano. 2014 Jan 28;8(1):458–466. doi: 10.1021/nn4048205. PubMed PMID: 24341611. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3947749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren K, Dusad A, Yuan F, Yuan H, Purdue PE, Fehringer EV, et al. Macromolecular prodrug of dexamethasone prevents particle-induced peri-implant osteolysis with reduced systemic side effects. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2014 Feb 10;175:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.11.024. PubMed PMID: 24326124. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3946775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]