Abstract

Early detection and accurate estimation of the extent of coarctation of the aorta (COA) is critical to long-term outcome. Peak-to-peak trans-coarctation pressure gradient (PKdP) higher than 20 mmHg is an indication for interventional/surgical repair. Patients with COA have reduced proximal and distal aortic compliances. A comprehensive study investigating the effects of variations of proximal COA and systemic compliances on PKdP, and consequently on the COA severity evaluation has never been done. This study evaluates the effect of aortic compliance on diagnostic accuracy of PKdP. Lumped parameter modeling and in vitro experiments were performed for COA severities of 50%, 75% and 90% by area. Modeling and in vitro results were validated against retrospective clinical data of PKdP, measured in fifty-four patients with COA. Modeling and in vitro. PKdP increases with reduced proximal COA compliance (+36%, +38% and +53% for COA severities of 50%, 75% and 90%, respectively; p<0.05), but decreases with reduced systemic compliance (−62%, −41% and −36% for COA severities of 50%, 75% and 90%, respectively; p<0.01). Clinical study. PKdP has a modest correlation with COA severity (R=0.29). The main determinants of PKdP are COA severity, stroke volume index and systemic compliance. Systemic compliance was found to be as influential as COA severity in PKdP determination (R=0.30 vs. R=0.34). In conclusion, PKdP is highly influenced by both stroke volume index and arterial compliance. Low values of PKdP cannot be used to exclude the severe COA presence since COA severity may be masked by reduced systemic compliance and/or low flow conditions.

Keywords: Coarctation of the aorta, Arterial compliance effect, Peak to peak pressure gradient, Catheterization

1. Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta (COA) is the most common congenital heart defect, accounting for 5% to 8% of all congenital heart defects, occurring in 8–11% of births annually (Roger et al., 2011). Despite ongoing advances in surgical techniques for COA repair the long-term results are not always satisfactory. The incidence of recurrence is significant (8-54%) and frequently requires repeat surgery (Cohen et al., 1989; Kopf et al., 1986). Surgical management of recurrent or residual COA is associated with some morbidity Williams et al., 1980). The long-term prognosis after repair of COA is not entirely benign. Associated structural cardiovascular lesions such as mitral or aortic valve disease, ventricular septal defect and cerebrovascular malformations are responsible for considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality. Hypertension may persist even after a successful correction of COA (Nanton and Olley, 1976; Maia et al., 2000).

Early detection and accurate estimation of COA severity are of primary importance for successful long-term outcome following the initial repair (Cohen et al., 1989). In the clinical setting, several invasive and non-invasive modalities have been used to determine the severity of COA before surgery as well as to evaluate residual hypertension and/or obstruction after balloon dilatation or after surgery. Among them, cardiac catheterization with angiography and hemodynamic evaluation is considered as the gold standard for definitive evaluation of COA severity (Yetman et al., 1997; Maheshwari et al., 2000; Warnes et al., 2008). Current AHA guidelines suggest a peak-to-peak systolic trans-coarctation pressure gradient (PKdP) > 20 mmHg as an indication for interventional/surgical repair (Brili et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 2005). Although many studies (Gardiner et al., 1994; Xu et al., 1997; Brili et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 2005) reported that patients with COA have pressure overload, in the arterial circulation proximal to the COA, and reduced compliances, in the proximal and distal aorta, little is known about the impact of variations in the arterial compliance on trans-coarctation pressure gradient (Xu et al., 1997). To the best of our knowledge a comprehensive study investigating the effects of variations of proximal COA and systemic compliances on the PKdP, and consequently on the evaluation of COA severity has never been done in the past.

The aim of the present work was to perform such a comprehensive study using combined lumped parameter modeling, in vitro measurements and retrospective clinical study.

2. Methods

2.1 Lumped parameter model

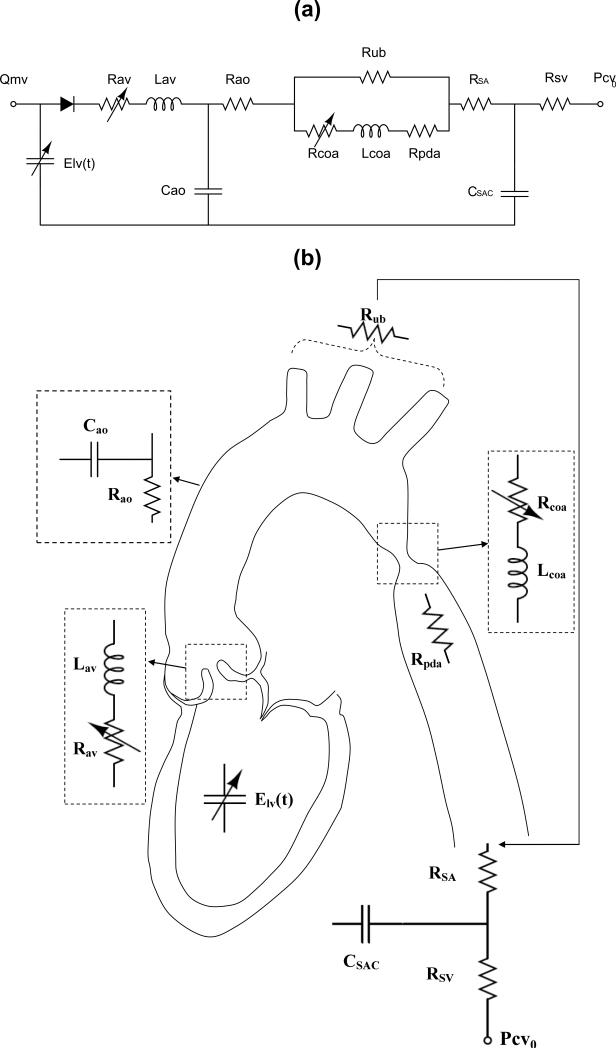

We introduced a lumped parameter model (Figure 1, Table 1) that describes the interaction between left ventricle (LV), COA, and arterial dynamics. The validation of the model has already been performed using in vivo MRI data (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2011; Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2014a). A schematic diagram of the model used in this study is presented in Figure 1. All parameters used in the lumped parameter model are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the lumped parameter model. (a) electrical representation, (b) anatomical representation. Abbreviations are similar as in Table 1

Table 1.

Cardiovascular parameters used in the lumped parameter modeling to simulate coarctation of the aorta

| Description | Abbreviation | Value | Maximum error* |

|---|---|---|---|

| COA and valve parameters | |||

| Effective orifice area | EOA | From COA and aortic valve data | |

| Energy loss coefficient | ELCo | From COA and aortic valve data | |

| Variable resistance | Rcoa & Rav | From COA and aortic valve data | |

| Inductance | Lcoa & Lav | From COA and aortic valve data | |

| Systematic circulation parameters | |||

| Aortic resistance | Rao | 0.05 mmHg.s.mL−1 | 0.31% |

| Aortic compliance | Cao | Initial value: 0.5 mL/mmHg Adjust for each degree of hypertension (Proximal COA compliance) | 0.41% |

| Systemic vein resistance | RSV | 0.05 mmHg.s.mL−1 | 0.26% |

| Systemic arteries and veins compliance | CSAC | Initial value: 2 mL/mmHg Adjust for each degree of hypertension (Systemic compliance) | 0.91% |

| systemic arteries resistance (including arteries, arterioles and capillaries) | RSA | 0.8 mmHg.s.mL−1 | 1.13% |

| Upper body resistance | Rub | Adjusted to have 15% of total flow rate in healthy case (McDonald, 1974) | 0.55% |

| Proximal descending aorta resistance | Rpda | 0.05 mmHg·s·mL−1 | 0.48% |

| Output condition | |||

| Central venous pressure | PCVO | 4 mmHg | |

| Input condition | |||

| Mitral valve mean flow rate | Qmv | ||

| Other | |||

| Constant blood density | 1050 kg/m3 | ||

| Heart rate | HR | 70 beats/min | |

| Duration of cardiac cycle | T | 0.857 s |

Maximum error in computed PKdP from sensitivity analysis in response to independent variation (±30%) in each parameter.

2.1.1 Heart-arterial model

The ventricle is filled by a normalized physiological mitral flow waveform adjusted for the required stroke volume (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2011; Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2014a). Coupling between LV pressure and volume is performed through a time varying elastance E(t) which is a measure of cardiac muscle stiffness.

| (1) |

Where PLV(t), V(t) and V0 are left ventricular time-varying pressure, time-varying volume and unloaded volume, respectively (Suga et al., 1973; Senzaki et al., 1996). The amplitude of E(t) can be normalized with respect to maximal elastance Emax, i.e., the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relation, giving EN(tN)=E(t)/Emax. Time then can be normalized with respect to the time to reach peak elastance, TEmax (tN=t/TEmax). These normalized time-varying elastance curves EN(tN) have similar shapes in the normal human heart under various inotropic conditions or in affected human hearts irrespective of disease etiology (Suga et al., 1973; Senzaki et al., 1996).

| (2) |

This normalized curve can be described mathematically (Fourier series, polynomial description), and therefore, if EN(tN) is given, the relation between PLV(t) and V(t) can be determined for the left ventricle.

2.1.2 Modeling coarctation of the aorta

We provide here a succinct description, more details can be found in Keshavarz-Motamed et al. (2011). The characteristics of the arterial system are of primary importance when modeling COA since only a portion of total flow rate will cross the COA. To take this into account in the model, two parallel branches are considered. The first branch simulates the flow towards the upper body, or the flow bypassing the COA (including aortic arch arteries and potential collaterals). A second branch simulates the flow crossing COA and directed towards descending aorta. This branch includes a resistance for the proximal descending aorta, and a time-varying resistance and an inductance which together represent the trans-COA net pressure gradient induced by the COA:

| (3) |

And

| (4) |

where , , A, ρ and Q are the energy loss coefficient of the COA, the effective orifice area of the COA, aortic cross sectional area downstream of the COA, the fluid density and the trans-COA flow rate, respectively. The energy loss coefficient is then expressed in terms of the aortic cross section just downstream of the COA and the effective orifice area of the COA (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2011).

2.1.3 Determining arterial compliance

Physiologically, arterial hypertension is determined by two factors (Safar et al., 2003): 1) a reduction in the caliber of small arteries or arterioles with an ensuing increase in systemic vascular resistance and mean blood pressure, and 2) a reduction in the arterial compliance with a resulting increase in pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic blood pressure). In this study, for each degree of hypertension, we fitted the predicted pulse pressure to the actual pulse pressure obtained from in vitro study by adjusting compliances (proximal COA (Cao) and systemic (CSAC)). Therefore, compliance adjustment was done by a simple trial and error for each degree of hypertension (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2014a).

2.1.4 Computational algorithm

A lumped parameter model was analyzed numerically by creating and solving a system of ordinary differential equations in Matlab Simscape (MathWorks, Inc), enhanced by adding additional codes to meet demands of cardiac model in circuit. A Fourier series representation of an experimental normalized elastance curve for human adults (Senzaki et al., 1996) was used to generate a signal to be fed into the main program. The pressure gradient across the COA and the aortic valve was represented by an inductance and a variable resistor (Figure 1, Equation 3). Simulations start at the onset of isovolumic contraction. Left ventricle volume, V(t), is calculated using left ventricle pressure, PLV, and time varying elastance values (equation 1). PLV used in the beginning of calculation is the initial value assumed across the variable capacitor and is automatically adjusted later by system of equations as solution advances. Left ventricle flow rate subsequently was calculated as time derivative of left ventricle volume. Matlab's ode23t trapezoidal rule variable-step solver was used to solve system of differential equations with initial time step of 0.1 milliseconds. Convergence residual criterion was set to 10−5 and initial voltages and currents of capacitors and inductors set to zero.

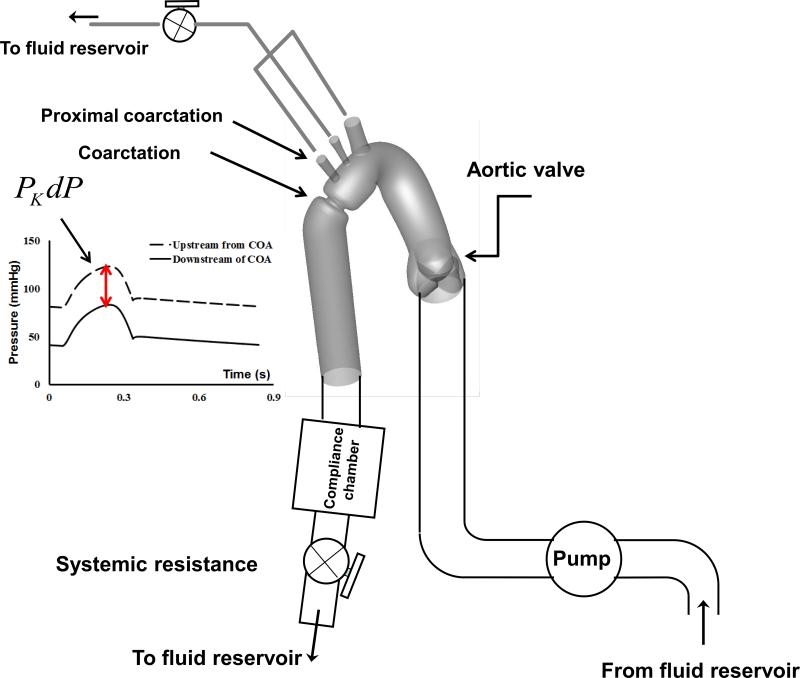

2.2 In vitro measurements

We designed and constructed a mock flow circulation model, consisted of a fluid reservoir, a gear pump, realistic elastic three-dimensional models of the aorta, an adjustable systemic arterial resistance and compliance (Figure 2). This model has been previously validated (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2012; Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2014b). Please refer to Appendix A for details about in vitro setups.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the in vitro flow model. PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient

2.2.1 Experimental conditions

Three different COA severities of 50%, 75% and 90% by area, corresponding to the diameter ratio (COA/Aorta) of 0.7, 0.5 and 0.31, respectively, under 4 different total flow rates of 3, 4, 5 and 6 L/min, and with a heart rate of 70 bpm were investigated. As patients with COA classically have upper extremity hypertension and reduced systemic compliance in proximal and distal segments of the COA (Gardiner et al., 1994; Xu et al., 1997; Brili et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 2005), the impact of the arterial compliance on PKdP was evaluated in this study by: 1) Changing the proximal COA compliance (normal proximal compliance: 0.45 to 0.5 mL/mmHg; low proximal compliance: 0.25 to 0.45 mL/mmHg; very low proximal compliance: 0.1 to 0.25 mL/mmHg); 2) Changing the systemic compliance (normal systemic compliance: 1.9 to 2 mL/mmHg; low systemic compliance: 1.4 to 1.9 mL/mmHg; very low systemic compliance: 0.85 to 1.4 mL/mmHg). Proximal COA compliance was reduced, in vitro, using custom-made fixtures designed to fit the region. These fixtures locally reduced the elasticity of the phantom without introducing any geometrical deformation that may have an impact on the fluid flow. Using these fixtures, experiments with different levels of rigidity of the proximal COA were performed. The changes in the systemic arterial compliance were obtained by modifying the pressure conditions in the systemic compliance module using a column of water (Figure 2).

2.3 Clinical data measurements

2.3.1 Ethics statement

Patients with COA, requiring diagnostic or interventional cardiac catheterization, were considered for this study. Measurements were performed according to the American College of Cardiology & American Heart Association guidelines (Tracy et al., 2000; Pepine et al., 1991). The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Milad-Noor Hospital affiliated Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. All patients provided written informed consent under the supervision of the Institutional Review Board.

2.3.2 Study population

Fifty-nine patients with COA, ranged in age from 4 to 26 years, referred to Milad-Noor Hospital between April 2010 and December 2012, were included in this study. Associated cardiovascular lesions included bicuspid aortic valve (eighteen patients), mild and moderate tricuspid aortic valve stenosis (eight patients), small patent ductus arteriosus (four patients), small ventricular septal defect (one patient) and mild mitral stenosis (two patients).

2.3.3 Measurements

A diagnostic catheterization was performed to determine the exact morphology and the pressure gradient of the COA in all patients. Angiography was performed in lateral and anteroposterior or left anterior oblique projections. Measurements of the aorta were made and averaged at five different sites: ascending aorta, isthmus proximal coarctation, coarcted region, descending aorta distal to the coarctation as well as at the level of the diaphragm. For the assessment of COA, the pullback PKdP was obtained across the COA site. Pressure drop estimation was unsuccessful in five neonates with coarctation and a patent ductus arteriosus and interrupted aortic arch, resulting in a total of fifty-four successful studies.

2.3.4 Systemic arterial compliance

Systemic arterial compliance (CSAC) was determined as (Keshavarz-Motamed et al., 2014a):

| (5) |

where SVi, PP are stroke volume indexed by the body surface area and brachial pulse pressure, respectively. Stroke volume was measured using Doppler echocardiography either at catheterization or 24 hours before catheterization with a commercially available echocardiography machine (Vivid 3, GE Ultrasound, Horten, Norway).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. In the multivariate analysis, we included all variables with p<0.05 in the univariate analysis as the criterion for entry of the variable into the model. Standardized regression coefficients were presented as mean ± standard error (βeta coeff ± SE). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1 In vitro measurements and lumped parameter modeling

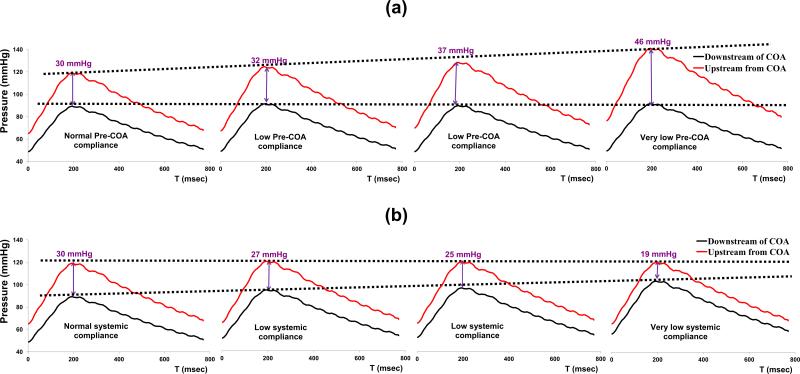

Figure 3 represents a sample of the in vitro data for a COA with a 90% reduction in area and for a total flow rate of 6 L/min. It can be noticed that as a result of changing proximal COA compliance, the PKdP substantially increases from 30 mmHg to 46 mmHg (Figure 3a); while, interestingly, changes in systemic compliance have an opposite effect leading to a decrease in PKdP from 30 mmHg to 19 mmHg.

Fig. 3.

(a) Example of variations in in vitro PKdP due to changes in proximal COA compliance; (b) Example of variations in in vitro PKdP due to changes in systemic compliance. PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient. Total flow rate: 6 L/min; COA severity: 90%

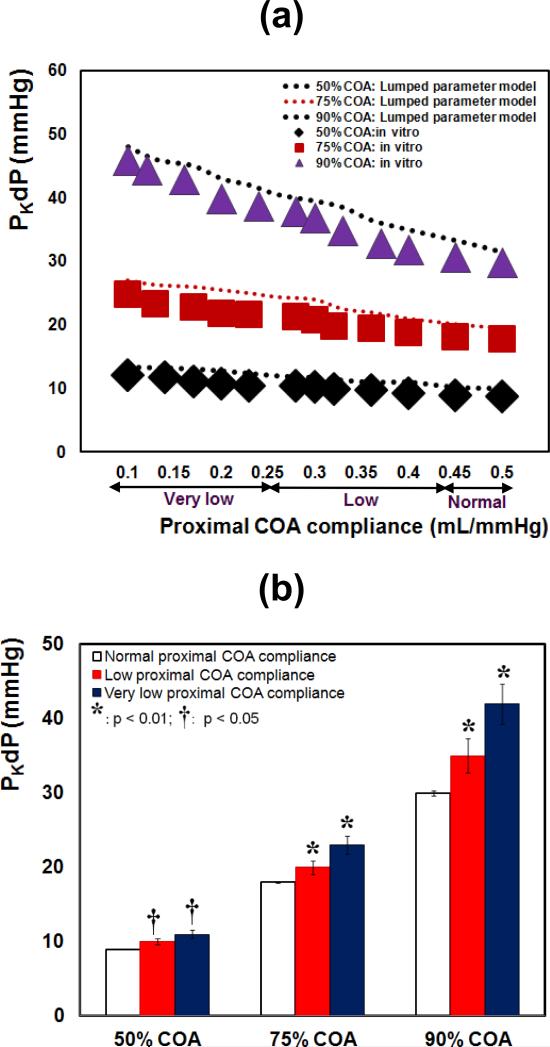

3.1.1 Effect of reduced proximal coa compliance on PKdP

Results from both in vitro measurements and lumped parameter model (Figure 4a) demonstrated that PKdP is greatly affected by the variation of the proximal COA compliance. For all COA severities, PKdP increases significantly, when proximal COA compliance was reduced from 0.5 to 0.1 mL/mmHg. In vitro, PKdP increased by +36% (9 to 12.3 mmHg) for 50% COA, by +38% (18 to 25 mmHg) for 75% COA and by +53% (30 to 46 mmHg) for 90% COA. PKdP with reduced proximal COA compliance was significantly higher than with normal COA compliance for all COA severities (Figure 4b, p < 0.05 for 50% COA; p < 0.01 for 75% COA and 90% COA). In all conditions, lumped parameter model predictions are consistent with in vitro findings. The slopes of the lines fitted to the in vitro and model results, are within the range of 3% to 7% (Figure 4a).

Fig. 4.

(a) in vitro and simulated PKdP variations with proximal COA compliance for different COA severities; (b) in vitro PKdP variations with proximal COA compliance (*: p<0.01 compared with normal proximal COA compliance; †: p<0.05 compared with normal proximal COA compliance). PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient. Total flow rate: 6 L/min

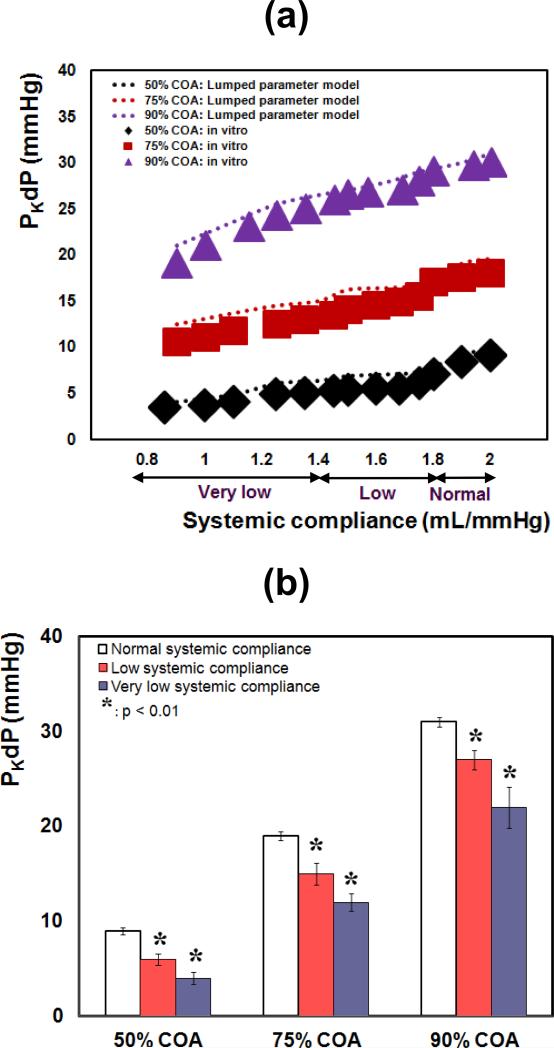

3.1.2 Effect of reduced systemic compliance on PKdP

Both in vitro measurements and the lumped-parameter modeling show that the effect of the systemic compliance on the PKdP is the inverse of that of the proximal COA compliance: reduction in the systemic compliance increases the PKdP (Figure 5a). In this case, for all COA severities, PKdP decreased significantly, when systemic compliance was reduced from 2.0 to 0.85 mL/mmHg. In vitro, PKdP decreased by 62% (9 to 3.4 mmHg) for 50% COA, by 41% (18 to 10.6 mmHg) for 75% COA and by 36% (30 to 19 mmHg) for 90% COA. PKdP with reduced systemic compliance was significantly lower than with normal compliance for all COA severities (Figure 5b, p < 0.01). In all conditions, lumped parameter model predictions are consistent with in vitro findings. The slopes of the lines fitted to the in vitro and model results, are within the range of 3.5% to 8% (Figure 5a).

Fig. 5.

(a) in vitro and simulated PKdP variations with systemic compliance for different COA severities; (b) in vitro and simulated PKdP variations with systemic compliance (*: p<0.01 compared with normal systemic arterial compliance). PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient. Total flow rate: 6 L/min

Finally, note that, for simplicity, only results at the flow rate of 6 L/min and symmetric COAs are displayed, similar observations were also made with the other three flow rates (3, 4 and 5 L/min) and with asymmetric COAs with the same severities.

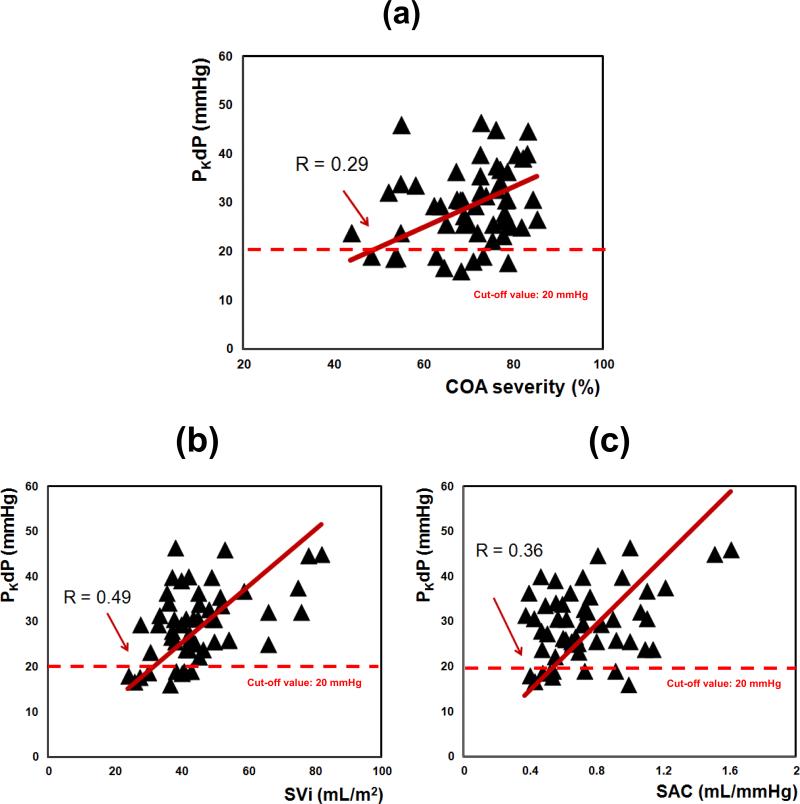

3.2 Clinical study

Baseline characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 2, including mean blood pressure of 100 ± 10.25 mmHg, mean COA diameter of 14 ± 1.6 mm and mean COA severity of 70 ± 9.73%, corresponding to a mean diameter ratio (COA/Aorta) of 0.59 ± 0.87. According to these data, there was a modest correlation between PKdP and COA severity (R = 0.29, Figure 6a), SVi (R = 0.49, Figure 6b) and CSAC (R = 0.36, Figure 6c). Nevertheless, multivariate analysis showed that COA severity, SVi and CSAC were the main independent determinants of PKdP. These variables together explained all the variance of PKdP (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

| COA Patients (n=54, mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|

| Patient description | |

| Mean age, years | 13.1 ± 3.3 (4-26) |

| Gender | |

| Male, n | 33 |

| Female, n | 21 |

| Mean weight, kg | 39.2 ± 18.4 (13-94) |

| Stroke volume index (SVi)(mL.m−2) | 43 ± 8.47 (25.97-66) |

| Arterial hemodynamics | |

| Systemic arterial compliance (CSAC) (mL.mmHg−1) | 1 ± 0.26 (0.31-1.61) |

| Systolic arterial pressure (mmHg) | 142 ± 18 (107-180) |

| Diastolic arterial pressure (mmHg) | 79 ± 9.57 (56-100) |

| Coarctation description | |

| COA length, mm | 25 ± 6.2 (10-35) |

| COA diameter, mm | 14 ± 1.6 (10.3-18.2) |

| COA severity, % | 70 ± 9.73 (44-85) |

| Diameter ratio (COA/Aorta) | 0.59 ± 0.87 (0.38-0.75) |

| Associated cardiovascular lesions | |

| Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) | 18 |

| Tricuspid aortic valve stenosis (AS) | |

| Moderate, n | 7 |

| severe, n | 1 |

| Small patent ductus arteriosus | 4 |

| Small ventricular septal defect | 1 |

| Mild mitral stenosis | 2 |

Fig. 6.

Clinical variations of (a) PKdP with COA severity; (b) PKdP with stroke volume index (SVi); (c) PKdP with systemic arterial compliance (CSAC). PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for peak-to-peak pressure gradient, PKdP

| PKdP Based on clinical data | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Std βeta coefficient ± SE | p-value | R | *Std βeta coefficient ± SE | p-value | R | |

| COA severity (%) | 0.29 ± 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.34 |

| SVi (mL/m2) | 0.49 ± 0.07 | < 0.001 | 0.49 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.3 |

| CSAC (mL/mmHg) | 0.36 ± 3.71 | < 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.30 ± 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.3 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 0.11 ± 7.89 | 0.45 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

Std βeta coeff ± SE: Standardized βeta coefficient and standard error

p<0.05 in the Univariate analysis is the criterion for entry of the variable into the Multivariate analysis

The total R of the multivariable model was 0.94

4. Discussion

The most important predictor of successful long-term outcome in patients with COA is age at time of initial repair (Cohen et al., 1989). As a consequence, early detection and accurate estimation of COA severity is of primary importance. Cardiac catheterization with significant PKdP across the coarcted segment (PKdP > 20 mmHg) is an important indication of significant COA (Maheshwari et al., 2000; Ralph-Edwards et al., 1995; Beekman et al., 1981). Many studies reported that patients with COA have reduced compliances, in the proximal and distal aorta (e.g., Gardiner et al., 1994; Xu et al., 1997; Brili et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 2005). However little to no literature is treating about the impact of variations in the arterial compliance on trans-coarctation pressure gradient, and consequently on the evaluation of COA severity (Xu et al., 1997; Seifert et al., 1999). The main findings of this study are the followings: 1) reduction in proximal aortic compliance increases PKdP; 2) reduction in systemic compliance deceases PKdP; 3) the main determinants of the variations in PKdP are SVi, COA severity and systemic compliance; 4) systemic compliance is as important as COA severity in the determination of PKdP.

4.1 Patients with COA and reduced proximal COA compliance

Patients with COA usually have upper extremity hypertension and are characterized by reduced compliance in both proximal and distal of COA (Gardiner et al., 1994; Xu et al., 1997; Brili et al., 1998; Vogt et al., 2005). A widespread structural alteration of the aortic wall in patients with COA may be responsible for these abnormalities (Gardiner et al., 1994). However, proximal COA was stiffer than distal aorta in patients with COA (Xu et al., 1997). The results of this study show that reduced proximal COA compliance interacts with COA and amplified PKdP. This could in part explain why some patients who have had a good repair of COA may have residual upper body hypertension at rest or with exercise despite having little evidence of significant recoarctation (Nanton and Olley, 1976; Maia et al., 2000; Gunthard et al., 1996).

4.2 Patients with COA and reduced systemic compliance

Patients with COA have higher incidence of systemic hypertension (up to 68%) even after successful repair of the COA (Clarkson et al., 1983; Maia et al., 2000). Systemic hypertension is associated with elevated systemic resistance and reduced systemic compliance. The results of this study show that PKdP is significantly affected by the variation in systemic compliance: PKdP reduced by a decrease in systemic compliance. Furthermore, in the clinical data set, PKdP correlated significantly with systemic compliance and was found to be as important as COA severity in determination of PKdP variations.

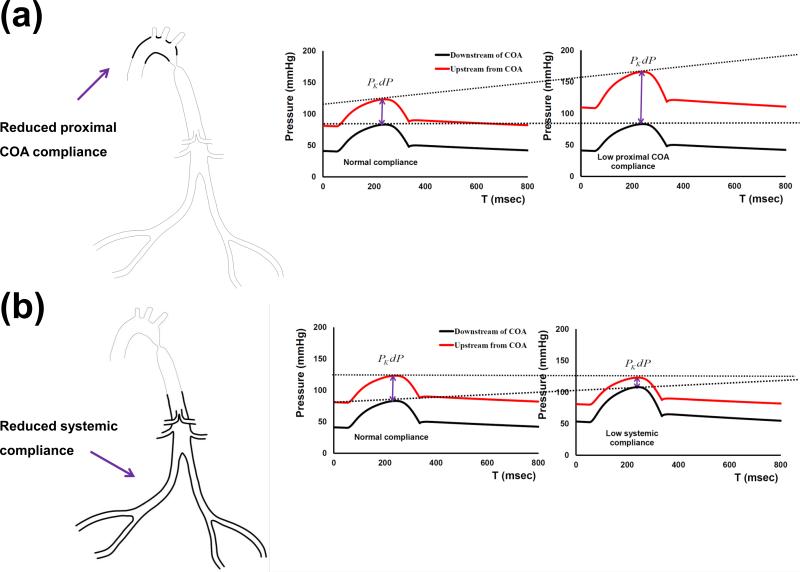

4.3 Potential role of pressure-wave reflections on PKdP in patients with COA

Effects of proximal COA and systemic arterial compliances on the variations of PKdP can be partially explained by pressure-wave reflections in the aorta in the presence of the COA. COA causes a significant mismatch in terms of the dispensability between the ascending aorta and the descending aorta. COA also represents a localized site for the enhancement of pressure-wave reflections towards the ascending aorta but also towards the lower body (O'Rourke and Cartmill, 1971; Van den wijngaard et al., 2009). As a consequence, changes in the compliances upstream (proximal aorta) and downstream (systemic arterial compliance) of the COA further amplify pressure wave reflections irrespective of COA severity (schematic diagram in Figure 7). A reduction in the proximal aortic compliance leads to an early return of the reflected pressure waves from the COA into the ascending aorta. This leads to an increase in the peak-aortic systolic pressure (O'Rourke and Cartmill, 1971). As a consequence, the PKdP is increased without any changes in the COA severity (Figure 7a). In contrast, a lower systemic compliance leads to an early return of the reflected pressure waves from the lower body towards the COA region. Thus, with no change in the COA severity, the PKdP falls as peak systolic pressure downstream of the COA rises (Figure 7b).

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of (a) variations in PKdP due to changes in proximal COA compliance changes; (b) variations in PKdP due to changes in systemic compliance. PKdP: peak-to-peak pressure gradient

5. Conclusion

PKdP recordings must be used with caution in patients with reduced proximal COA compliance and /or systemic compliance. In particular, low recorded values of PKdP should not be used to exclude severe COA in patients since this may result from reduced flow rate and/or reduced systemic arterial compliance. The aforementioned results suggest that COA is in fact a much more complex disease than previously thought and that limiting its evaluation to the determination of the PKdP is probably a gross oversimplification that may lead to erroneous conclusions.

6. Limitations of the study

The lumped parameter model presented in this study is capable of modeling different COA configurations and anatomical abnormalities of the aortic arch after successful repair of COA (Ou et al., 2004) through adjusting compliances (proximal COA (Cao) and systemic arteries (CSAC)) as well as resistances (aortic (Rao) and systemic arteries (RSA)) using the method introduced in Keshavarz-Motamed et al. (2014a). However, investigation of various COA configurations and anatomical abnormalities of the aortic arch has not been covered in this study. Also, patients with severe COA are usually hypertensive and might exhibit physiological changes such as variation in the heart rate. These physiological changes are out of the scope of this study. Nevertheless, this study did reveal that PKdP is highly influenced by the stroke volume index and arterial compliance. Future studies can investigate the above mentioned parameters in vitro and in silico.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partly by research grants of Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (grant # 343165–07). Dr. Zahra Keshavarz-Motamed was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRSQ). Dr. Julio Garcia was supported by American Heart Association (AHA) and National Council of Science and Technology-Mexico (CONACyT).

Footnotes

9. Contributors

ZKM: Conceptualized and designed the research, developed the lumped parameter model, ran simulations, designed a unique custom made in vitro set up, performed experiment, analyzed data, interpreted results, drafted, edited and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. ERE: Conceptualized and designed the research, interpreted the results, gave inputs that substantially improved the manuscript, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. PKM: Coordinated data collection, interpreted the results, help analysing the data, gave inputs that substantially improved the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JG: Designed a unique custom made in vitro set up, performed experiment, helped analysing data, interpreted the results, reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. ND: Interpreted the results, gave inputs that substantially improved the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LK: Conceptualized and designed the research, interpreted the results, gave inputs that substantially improved the manuscript, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

7. Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Beekman RH, Rocchini AP, Behrendt DM, Rosenthal A. Reoperation for coarctation of the aorta. American Journal of Cardiology. 1981;48:1108–1114. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brili S, Dernellis J, Aggeli C, Pitsavos C, Hatzos C, Stefanadis C, Toutouzas P. Aortic elastic properties in patients with repaired coarctation of aorta. American Journal of Cardiology. 1998;82:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemla D, Hebert JL, Coirault C, Zamani Z, Suard I, Colin P, Lecarpentier Y. Total arterial compliance estimated by stroke volume-to-aortic pulse pressure ratio in humans. American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1998;274:500–505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Fuster V, Steele P, Driscoll D, McGoon D. Coarctation of the aorta, long-term follow-up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction. Circulation. 1989;80:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson PM, Nicholson MR, Barratt-Boyes BG, Neutze JM, Whitlock RM. Results after repair of coarctation of the aorta beyond infancy: a 10 to 28 year follow-up with particular reference to late systemic hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 1983;51:1481–1488. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mey S, Segers P, Coomans I, Verhaaren H, Verdonck P. Limitations of Doppler echocardiography for the post-operative evaluation of aortic coarctation. Journal of Biomechanics. 2001;34:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner HM, Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Thomas O, Deanfield JE. Arterial reactivity is significantly impaired in normotensive young adults after successful repair of aortic coarctation in childhood. Circulation. 1994;89:1745–1750. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthard J, Buser PT, Miettunen R, Hagman A, Wyler F. Effects of morphologic restenosis, defined by MRI after coarctation repair, on blood pressure and arm-leg Doppler gradients. Angiology. 1996;47:1073–1080. doi: 10.1177/000331979604701107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herment A, Lefort M, Kachenoura N, Cesare DA, Taviani V, Graves MJ, Pellot-Barakat C, Frouin F, Mousseaux E. Automated estimation of aortic strain from steady-state free-precession and phase contrast MR images. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;65:986–993. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MD, Meadows AK, Hope TA, Ordovas KG, Saloner D, Reddy GP, Alley MT, Higgins CB. Clinical evaluation of aortic coarctation with 4D flow MR imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2010;31:711–718. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Garcia J, Pibarot P, Larose E, Kadem L. Modeling the impact of concomitant aortic stenosis and coarctation of the aorta on left ventricular workload. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44:2817–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Garcia J, Maftoon N, Bedard E, Chetaille P, Kadem L. A new approach for the evaluation of the severity of coarctation of the aorta using Doppler velocity index and effective orifice area: in vitro validation and clinical implications. Journal of Biomechanics. 2012;45:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Garcia J, Gaillard E, Capoulade R, LeVen F, Cloutier G, Kadem L, Pibarot P. Non-invasive determination of left ventricular workload in patients with aortic stenosis using magnetic resonance imaging and Doppler echocardiography. PLoS ONE. 2014a;9:e86793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Garcia J, Gaillard E, Maftoon N, DiLabbio G, Cloutier G, Kadem L. Effect of coarctation of the aorta and bicuspid aortic valve on flow dynamics and turbulence in the aorta using particle image velocimetry. Experiments in Fluids. 2014b;55:1696. [Google Scholar]

- Kopf G, Hellenbrand W, Kleinman C, Lister G, Talner N, Laks H. Repair of aortic coarctation in the first three months of life: Immediate and long-term results. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1986;41:425–430. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia MM, Aiello VD, Barbero-Marcial M. Coarctation of the aorta corrected during childhood. Clinical aspects during follow-up. Arquivos Brasileiros De Cardiologia. 2000;74:167–180. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2000000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari S, Bruckheimer E, Fahey JT, Hellenbrand WE. Balloon angioplasty of postsurgical recoarctation in infants: the risk of restenosis and long-term follow-up. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 2000;35:209–213. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markl M, Arnold R, Hirtle D, Muhlen CVZ, Harloff A, Langer M, Hennig J, Frydrychowicz A. Three-dimensional flow characteristics in aortic coarctation and poststenotic dilatation. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 2009;33:776–778. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181906766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DA. Blood flow in arteries. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, USA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Nanton MA, Olley PM. Residual hypertension after coarctation in children. American Journal of Cardiology. 1976;37:769–972. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke MF, Cartmill TB. Influence of aortic coaretation on pulsatile hemodynamies in the proximal aorta. Circulation. 1971;44:281–292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke M, Farnsworth A, O'Rourke J. Aortic dimensions and stiffness in normal adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2008;1:749–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou P, Bonnet D, Auriacombe L, Pedroni L, Balleux F, Sidi F, Mousseaux L. Late systemic hypertension and aortic arch geometry after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. European Heart Journal. 2004;25:1853–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepine CJ, Allen HD, Bashore TM, Brinker JA, Cohn LH, Dillon JC, Hillis LD, Klocke FJ, ParmLey WW, Ports TA. ACC/AHA guidelines for cardiac catheterization and cardiac catheterization laboratories. American college of cardiology/american heart association ad hoc task force on cardiac catheterization. Circulation. 1991;84:2213–2247. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph-Edwards AC, Williams WG, Coles JC, Rebeyka IM, Trusler GA, Freedom RM. Reoperation for recurrent aortic coarctation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1995;60:1303–1307. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00619-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, Simone GD, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Greenlund KJ, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Ho PM, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McDermott MM, Meigs JB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Rosamond WD, Sorlie PD, Stafford RS, Turan TN, Turner MB, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:118–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar ME, Levy BL, Struijker-Boudier H. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2003;107:2864–2869. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069826.36125.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzaki H, Chen CH, Kass DA. Single-beat estimation of end-systolic pressure-volume relation in humans. A new method with the potential for noninvasive application. Circulation. 1996;94:2497–2506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert BL, DesRochersa K, Taa M, Giraud G, Zarandi M, Gharib M, Sahn DJ. Accuracy of Doppler methods for estimating peak-to-peak and peak instantaneous gradients across coarctation of the aorta: an in vitro study. Journal of American Society of Echocardiography. 1999;12:744–753. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(99)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H, Sagawa K, Shoukas AA. Load independence of the instantaneous pressure-volume ratio of the canine left ventricle and effects of epinephrine and heart rate on the ratio. Circulation Research. 1973;32:314–322. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy CM, Akhtar M, DiMarco JP, Packer DL, Weitz HH, Winters WL, Achord JM, Boone AW, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Lorell BH, Rodgers GP, Tracy CM, Weitz HH. American college of cardiology/american heart association clinical competence statement on invasive electrophysiology studies, catheter ablation, and cardioversion: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association/american college of physicians-american society of internal medicine task force on clinical competence. Circulation. 2000;102:2309–2320. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den wijngaard JP, Siebes M, Westerhof BE. Comparison of arterial waves derived by classical wave separation and wave intensity analysis in a model of aortic coarctation. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 2009;47:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt M, Kühn A, Baumgartner D, Baumgartner C, Busch R, Kostolny M, Hess J. Impaired elastic properties of the ascending aorta in newborns before and early after successful coarctation repair: proof of a systemic vascular disease of the prestenotic arteries. Circulation. 2005;111:3269–3273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP, Jr, Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP, Webb GD, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with CHD. Circulation. 2008;118:714–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams W, Shindo G, Trusler G, Dische M, Olley P. Results of repair of coarctation of the aorta during infancy. Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery. 1980;79:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Shiota T, Omoto R, Zhou X, Kyo S, Ishii M, Rice MJ, Sahn DJ. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of regional aortic wall stiffness, distensibiLy, and compliance in patients with coarctation of the aorta. American Heart Journal. 1997;134:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetman AT, Nykanen D, McCrindle BW, Sunnegardh J, Adatia I, Freedom RM, Benson L. Balloon angioplasty of recurrent coarctation: a 12-year review. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 1997;30:811–816. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.