Abstract

Engaging men in addressing violence against women (VAW) has become a strategy in the global prevention of gender-based violence. Concurrently, Western public health frameworks have been utilized to guide prevention agendas worldwide. Using qualitative methods, this study describes how global anti-violence organizations that partner with men conceptualize primary prevention in their work. Findings suggest that ‘primary prevention’ is not a fixed term in the context of VAW and that front-line prevention work challenges rigidly delineated distinctions between levels of prevention. Much can be learned from global organizations’ unique and contextualized approaches to the prevention of VAW.

Keywords: Violence against women, engaging men, primary prevention

Given persistently high global rates of violence against women, there have been increased calls domestically and internationally to develop, implement and rigorously evaluate primary prevention programs that eliminate violence against women and specifically intimate partner violence (IPV) before it begins (World Health Organization (WHO), 2010). Violence against women is broadly understood as physical, emotional and psychological violence within the context of an intimate relationship, sexual assault (Kilpatrick, 2004,) sexual harassment, and trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation (UN Women, 2012). Violence against women is highlighted as a priority because of consistent evidence that women and girls are more frequently victims of severe and injurious forms of interpersonal abuse both in the U.S. (Basile & Black, 2011) and globally (WHO, 2010). A preventive intervention or program is considered primary if it is targeted before the onset of the social issue (Cohen & Chehimi, 2010). Engaging men as allies and partners has been increasingly promoted as one such primary prevention strategy (Tolman & Edleson, 2011), and this approach has been endorsed by such agencies as the WHO, the United Nations, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Flood, 2011).

With this push for increased primary prevention activities to prevent violence against women there is a tacit assumption that Western “science-based” public health strategies are essential for preventing violence against women (Chamberlain, 2008; Hammond, Whitaker, Lutzker, Mercy, & Chin, 2006; Prothrow-Stith & Davis, 2010). As Prothrow-Stith & Davis (2010) suggest: “Public health leaders and practitioners who understand effective, quality prevention have the theoretical and practical expertise needed to enrich efforts to reduce violence” (p. 343). Concomitant with the increasing adoption of a public health approach to understanding and preventing interpersonal violence is the emergence of programs aimed at proactively engaging men and boys as partners in efforts to end violence against women. Research has not yet, however, examined the overlap of these trends. Despite the growing acceptance of public health approaches to the prevention of violence against women, there has been no exploration into how prevention is understood by organizations that engage men as a prevention strategy.

The purpose of this study is to explore how global anti-violence organizations that partner with men conceptualize, construct, and operationalize prevention in their work. Although there are global dialogues about the importance of a public health approach to preventing violence against women, they seem largely driven by Western conceptualizations of prevention. Therefore we are not seeking to determine if organizations are implementing primary prevention activities as prescribed by these dominant frameworks, but rather to ascertain how agencies engaging men in violence prevention describe and implement front-line prevention. Therefore the ultimate goal is to learn from these global efforts and inform the development and evaluation of more community specific and contextualized prevention agendas. To frame this analysis, we briefly review frameworks that have been highly influential in operationalizing prevention (particularly in Western contexts), and then summarize extant literature related to how and to what extent these frameworks have been implemented and evaluated on the ground and in global contexts.

CONCEPTUALIZING PRIMARY PREVENTION

Feminist perspectives on prevention

Early feminist scholars such as Yllo and Bograd (1988) and Schechter (1982) contended that gender needed to be situated at the center of our understanding of prevention and the root causes of violence against women. These antecedents include community-level factors such as narrow gender roles for men and women and social norms that are permissive of violence (Heise, 1998; Prothrow-Stith & Davis, 2010) as well as gendered distributions of economic and political power within communities (WHO, 2010). Furthermore, a feminist perspective on prevention calls attention to gender socialization and structural inequities based on gender as inherent in legitimate prevention endeavors. For example, in a critical examination of gender equity promotion programs globally, researchers for the WHO concluded that programs that are “gender-sensitive” and included explicit attention to gender roles, and social constructions of masculinity, were more likely than programs not deemed gender sensitive to be effective at influencing participants’ attitudes and behaviors (WHO, 2009). Specific strategies that hold potential for reducing and/or ameliorating violence against women include economic, social, and policy approaches to improving gender equality; challenging gender-based social norms by redefining negative masculine norms; school-based prevention activities with children and youth; strengthening the social safety net; and reducing poverty and preventing incidents of child abuse (WHO, 2009). Examples of effective primary prevention programs that are predicated on promoting gender equitable social norms and fostering attitudes that are intolerant to violence against women include the SafeDates program in the U.S (Foshee, Bauman, Ennett, Linder, Benefield & Suchindran, 2004) and the Stepping Stones program in South Africa (Jewkes et al., 2008).

Public health perspectives on the primary prevention of intimate partner violence

Western public health prevention models have historically focused on infectious diseases and promoting general health (Silverman, 2003) and have more recently been applied to multidimensional social issues such as violence against women including intimate partner violence and sexual assault. The field of public health has been positioned as bringing “a perspective that has been missing from this field, that is, a multidisciplinary scientific approach that is directed explicitly toward identifying effective approaches to prevention” (Hammond, et al., 2006, p. 113). Public health prevention strategies are classified in two ways, the first being the point of intervention and the second being the target population. An intervention is considered primary prevention if it is targeted before onset, secondary prevention once early indicators have emerged, and tertiary prevention is rehabilitation to prevent reoccurrence (Cohen & Chehimi, 2010; Chamberlain, 2008; O'Connell, Boat & Warner, 2009). The second system of classification is the population that is being affected: universal (everyone will benefit), selective (people at higher risk than average) and indicated (people with early, detectable signs of the problem) (Chamberlain, 2008; O'Connell, et al., 2009). Since these distinctions were initially grounded in preventing health problems such as tobacco usage, there are inherent challenges in translating them to meet the “real-world” demands of complex social issues such as violence against women.

Ecological perspectives on primary prevention

Increasingly, primary prevention has been conceptualized using ecological models, which assume that risks for and solutions to social and behavioral problems reside in nested and mutually influential layers of individuals’ environments (CDC, 2004; Heise, 1998). For example, the Prevention Institute’s “Spectrum of Prevention” is one tool that has been utilized to guide primary prevention activities at all levels of the ecosystem (Cohen & Chehimi, 2010). The Spectrum of Prevention is applied to a variety of social and health issues and is regularly employed in the field of engaging men and boys in violence prevention (Flood, 2011). The six levels of strategy that make up Cohen and Chehimi’s (2010) Spectrum of Prevention include: 1) strengthening individual knowledge and skills; 2) promoting community education; 3) educating providers; 4) fostering coalitions and networks; 5) changing organizational practices; and 6) influencing policy and legislation. In the context of engaging men and boys in violence prevention, the Spectrum of Prevention approach encouraged organizations’ adoption of multiple approaches to engaging men and boys in violence prevention across multiple ecological levels. For example, Flood (2011) utilized the Spectrum of Prevention to categorize strategies for engaging men in violence prevention, from strengthening individual men’s knowledge and awareness of intimate partner and sexual violence to involving men in legislative advocacy efforts and reaching out to men in power.

Some have claimed that there has been “a profound shift toward primary prevention, aimed at preventing violence before it occurs” (Flood, 2011, p. 360). Rather than focusing on tertiary prevention strategies (such as batterers’ treatment or therapeutic counseling for victims,) a growing number of primary prevention models are being targeted at the population level (Graffunder, Cline & Lane, 2011). Although ecological and primary prevention approaches have received considerable attention, they have emerged primarily from Western conceptualizations of prevention and have not been rigorously evaluated to determine if they are germane internationally (WHO, 2007a). Additionally, it is important to clarify that there is considerable overlap between these models. Ecological models on the prevention of violence against women, for instance, still predominantly situate the role of societal gender norms in their analyses, and public health models both integrate ecological models of risk and protective factors and include gender among risk factors for victimization. Therefore, rather than see these as standalone or independent discourses, they should provide context on the multiple, and often intersecting, threads that embody the larger dialogue on preventing violence against women.

IMPLEMENTING PRIMARY PREVENTION

In practice, front-line organizations that address gender-based violence engage in a wide variety of prevention strategies. The WHO (2010) reported that organizations use early childhood and family based approaches, interventions to reduce alcohol abuse, public awareness campaigns, school-based programs, community-based approaches such as community mobilization and education, micro-finance programs and policy and legislative advocacy to challenge gendered social norms. In an earlier report, WHO (2007b) found that of 58 programs designed to promote gender equity, 29% were designated as “effective” at positively changing men’s attitudes and behaviors, and 38% as “promising.” Here, “effective” indicates strong program effects coupled with a rigorous evaluation, while “promising” connotes either moderate results, or less-rigorous evaluation methodology. Many organizations may not have the resources to access tested interventions or to evaluate their own efforts. Evidence from a previous analysis of the data used here suggests that prevention program evaluation is further complicated by a disjuncture between needs at a local level, and broader social structures, norms, policy or funding priorities (Casey et al., 2013). Indeed, across prevention efforts in other health promotion domains such as substance abuse prevention, there has been limited evidence of an impact on public health outcomes due to a low rate of implementing evidence-based programming (Biglan & Taylor, 2000; Sandler, Ostrom, Bitner, Ayers, Wolchik, et al., 2005) and a lack of fit between these programs and the “goals and capacities” of community–based agencies (Sandler, et al., 2005). Specific to sexual and domestic violence, Graffunder and colleagues (2011) have argued that many community-based agencies in the U.S. focus their prevention work largely on the dissemination of information about violence, which the authors note is a necessary but insufficient component of effective primary prevention and long-term behavioral change. This suggests that some gaps may exist between the way prevention is framed on a conceptual level, and how it is implemented in the field. However, aside from these studies, little research has examined how front-line organizations conceptualize their prevention work, or whether public health and ecological frameworks explicitly guide the prevention approaches selected by organizations. Further, the degree to which a public health approach to violence prevention is influential or relevant across global contexts, particular within men’s engagement efforts, remains under-examined.

In addition to a lack of research about the on-the-ground prevention practices of anti-violence agencies, there are a host of historical, financial and conceptual complexities that likely impact the ways that prevention is understood and implemented within organizations. Western domestic violence programs have historically prioritized interventions and services such as housing and advocacy for battered women, batterer’s treatment programs for perpetrators of abuse and responsive criminal justice based responses (McPhail, Busch, Kulkarni & Rice, 2007). In non-Western contexts, services to confront violence against women have emerged to foster broader social justice goals of promoting women’s economic autonomy, reducing poverty (WHO, 2009), delaying girls’ early marriage and promoting access to education (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2011), and to curtail the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (International Center for Research on Women, 2007; Maman, Campbell, Sweat & Gielen, 2000). As a result, prevention programming both domestically and internationally has been positioned within a broad constellation of other programs and services. Rather than positioned as being resistant to primary prevention (Cohen & Chehimi, 2010), as some have claimed, anti-violence programs are often tasked with the dual goals of meeting immediate needs of victims and survivors, as well as investing in primary prevention or what is sometimes referred to as upstream programming and organizational activities (Graffunder, et al., 2011).

In many ways this discussion highlights the dialogues that are informing the infusion of public health approaches into domestic violence agencies and underscores a larger intervention/prevention tension that exists between anti-violence organizations and public health oriented entities. Rather than endorsing one discourse over another, the goal here is to provide a backdrop for understanding the complexities involved in using Western prevention approaches to understand the larger global understanding of preventing violence against women.

The primary objectives of this paper are to describe the ways that front- line agencies that engage men as a prevention strategy understand and articulate primary prevention, explore how these conceptualizations get translated or operationalized into organizationally specific prevention activities, and ultimately start a dialogue about the relevance of Western public health prevention frameworks are for guiding the prevention of violence against women.

METHOD

Procedures

This study is part of a larger research project titled Mobilizing Men for Violence Prevention (MMVP), which aimed to describe the nature and extent of worldwide efforts to engage men in the prevention of violence against women through both a quantitative survey and more in-depth qualitative interviews. Additional articles from this same research project have outlined the social processes and strategies that have been utilized to engage men in anti-violence organizations, as well as the tensions inherent in a men’s engagement approach to anti-violence work. Please see Carlson et al. (in press) and Casey et al. (2013) for more in-depth descriptions of the findings that emerged from these prior analyses.

Generally speaking we approached this article from an interpretivist epistemology which constructs meaning as being co-created between the investigators and the research participants (Crotty, 1998). Our goal was to “understand, explain and demystify social reality,” (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2007, p.19) rather than present an objective version of truth. Our research team was composed of faculty and doctoral student researchers at three universities in the United States. We all have worked in the field of domestic violence as researchers and practitioners in various locales throughout the United States.

Participants in this study were drawn from a larger pool of program representatives from around the world who responded to an earlier online, quantitative survey of organizations that engage men to end violence (see Carlson et al., in press, for details regarding the first phase of this project). Respondents to the online survey were recruited via violence and prevention-related listservs, professional networks and programs around the world. Eligibility was defined as having part or all of an organizational mission dedicated to engaging men in violence prevention (operationalized as “men taking action to stop violence against women and children before it begins by advocating for and creating respectful relationships”). Out of the 165 programs responding to the online survey, 104 provided contact information and expressed a willingness to be recontacted for future research phases. Of these, we contacted 48 organizations by email to invite a program representative to participate in our in-depth interview for this study, and 29 agreed to participate. The 104 organizations were reduced to the 48 invited in the following ways. All responding organizations that provided information from Africa, Asia, Europe and Central and South America were re-contacted, with a goal of increasingly global representation. Additionally, a sample of organizations in Australia and North America, stratified for size and organizational type, were re-contacted. Programs indicating a willingness to participate in interviews completed an online consent form and were scheduled for a phone or Skype interview with one of the four interviewers on the research team.

Sample

Our final sample for this study consisted of 29 organizational representatives from programs in Australia, Brazil, Canada, England, Grenada, India, Kenya, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Rwanda, Scotland, South Africa, Syria, Thailand, Uganda and the United States. Of the 48 who initially expressed interest, nineteen organizations either did not respond to the invitation to participate, or did not follow up to schedule an interview. Participating organizations’ length of program history ranged from less than two years (7%, n=2), two to five years (41%, n=12), six to eight years (14%, n=4), and eight or more years (38%, n=11). Organizations also varied in identification of organizational structure. Thirteen (45%) were stand-alone programs, largely non-profits, with a primary focus on engaging men; 6 (21%) were units within larger agencies that sponsored a range of activities and services; 6 (21%) were regional or multi-country coalitions, 2 (7%) operated within university settings; and 2 (7%) were governmental organizations. Organizations reported a range of activities, including school-based prevention education, community education and mobilization, community-based men’s awareness or activist groups and convening national or international anti-violence coalitions. Additionally, although we recruited programs that work to stop violence before it begins, a handful of responding organizations could also be classified as fully or partially batterers’ intervention programs. These respondents positioned their work as falling within primary prevention, however. Given varied and blended perceptions among respondents of what constituted prevention, we retained these interviews for analyses.

Data Collection

We interviewed all organizational representatives over the phone or via Skype in English. Interviews varied from approximately 45 to 90 minutes in length. The interview guide was semi-structured, with broad questions designed to elicit information about the program’s strategies for engaging men, the frameworks that guide their work, the prevention approaches they use and the challenges and barriers inherent in their work of engaging men. As an initial screening question, organizational representatives were specifically asked to describe how their organization understood primary prevention or violence before it begins, and what approaches they used to meet these prevention goals. Topics particularly informing the analyses described here included questions regarding the program’s goals, definitions of prevention and specific prevention activities. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

We used a directed thematic content analysis approach that proceeded in two phases. First, we identified and created a list of sensitizing concepts connected to extant definitions of prevention that we anticipated might exist within the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Examples of the types of sensitizing codes we utilized included: primary prevention (before onset) and universal (available for the whole population). This step served to reflect on pre-existing notions of what we expected to find in the data, and to be clear how we collectively understood and applied prevention concepts. Second, we inductively identified codes representing concepts and themes within the data (Saldana, 2009), only keeping sensitizing concepts that indeed emerged from the data itself. For example, we initially included universal, indicated and selective prevention programs as a priori codes, however since these concepts never inductively emerged they were discarded. Codes emerging from the data were later organized into non-hierarchical categories such as within the category “Goals of Prevention Efforts,” where some of the following codes included were: public awareness, long-term social change, and promoting healthy masculinity. We generated a codebook that was continually amended and updated to reflect additional codes and themes.

To solicit a diversity of interpretive viewpoints and strengthen the overall analysis of the data, the first author shared her thoughts on emerging codes, categories and themes with the research team throughout the analysis process. Only minor discrepancies in interpretation emerged, and we were able to discuss and incorporate divergent interpretations into the final analysis. For example, the larger theme related to community awareness included both general awareness and skill building, but these concepts were later disaggregated as a result of analysts’ discussions. In addition to facilitating reflexivity, we used memos to identify relationships and patterns in the data which helped us refine themes. Once we applied codes to all the transcripts, we generated tables which compared codes both within and across the interviews (Ayres, Kavanaugh, & Knafl, 2003) and focused on the themes that surfaced across the all of the interviews. Divergent cases were noted and considered in the analysis, as well. It was through this process of “codeweaving” (Saldana, 2009) that we collaboratively identified the key processes and prominent themes presented in this paper. All data was stored and organized using ATLAS.ti version 6.

RESULTS

Global organizations engaging with men and boys conceptualized prevention broadly and in diverse ways. Across organizations, these conceptualizations ranged in their clarity, from some difficulty articulating a programmatic definition of prevention to defining prevention as encompassing multiple goals, sometimes at multiple levels. Additionally, rather than adopting or reflecting Western public health frameworks of clear distinctions between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, participating programs blended these concepts in organizationally-specific ways. Given the small number of organizations in each country or region of the world and the non-representative nature of the sample, it was not possible to categorize these emergent prevention conceptualizations regionally.

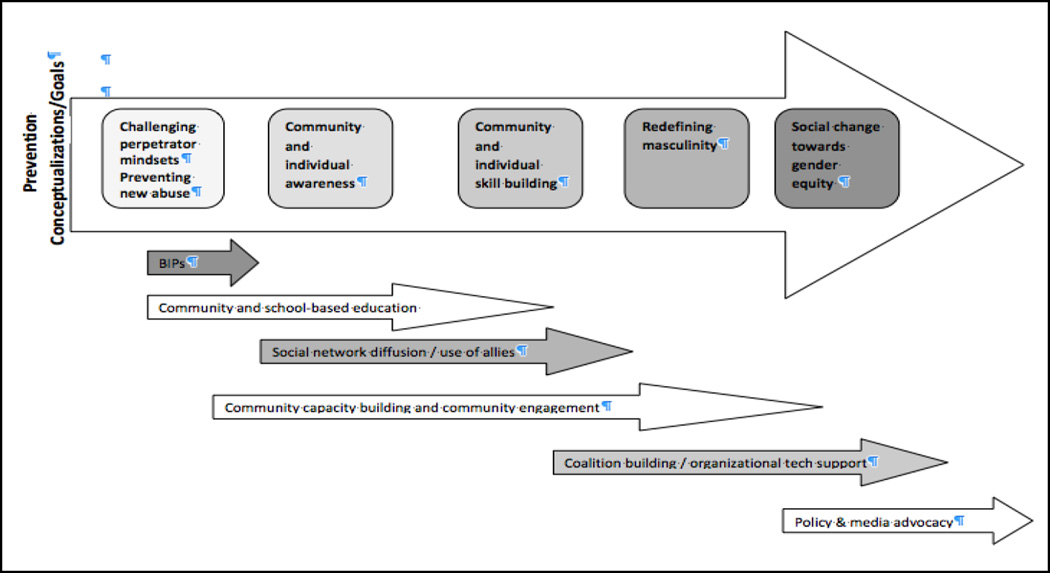

These prevention conceptualizations included: 1) preventing new incidents of abuse; 2) generating individual and community awareness and providing education about violence against women; 3) fostering individual competencies and skill building among non-indicated community members; 4) redefining masculinity at the individual, community and societal levels and; 5) advocating for long-term institutional and social change such as promoting gender equality, human rights and healthy relationships. Rather than rigid designations, most programs identified more than one of these conceptualizations as within their organizational goals and displayed a blending of prevention conceptualizations and approaches. Since these groupings of prevention conceptualizations are not static, they should not be seen as stages in adopting prevention orientations nor do they necessarily reflect changes in perceptions over time. Figure 1 was constructed to depict the emergence of this continuum of prevention conceptualizations and approaches. The large arrow which moves from left to right illustrates each type of prevention conceptualization from preventing new incidents of abuse to prevention as social change/gender equality. In addition to this continuum, each smaller arrow below contains a specific activity that organizations have described as a tool or mechanism for achieving their prevention goals. There was not always a neat correspondence of prevention goals and approaches. It became clear that different organizations used unique strategies to reach their prevention goals—some evidencing a clear rationale for their use of their approach while others did not.

Figure 1.

Approaches to Achieving Prevention Goals.

Preventing new incidents of abuse

Beginning on the left side of the prevention continuum illustrated in Figure 1, organizational representatives who could primarily or partially be classified as staffing batterers’ intervention programs, envisioned their work as prevention focused because it was transforming perpetrator mindsets and reinforcing perpetrator accountability which would ideally prevent new incidents of abuse. The corresponding prevention approaches included: therapeutic support groups for men, men’s “healing circles” and voluntary or mandated batterers’ treatment programs. As organizational representative #76 who coordinates multi-dimensional men’s groups from North America elucidated “we’re not only doing prevention, we’re doing healing. You have to do healing because all of the men and boys we deal with have wounds.” Although some organizational representatives acknowledged that their work could be seen as “primarily working with the men who use violence after the violence has been occurring” (#12, Europe), and thus not primary prevention by public health definitions, they still conceptualized their work as being prevention focused because it could prevent additional incidents of abuse. Representative #18 from an organization in Australia that coordinates batterers’ intervention programs and school-based prevention programs noted: “So the prevention part…is to put some strategies into place so that there are no further incidents, that men are accountable for their behavior.” The focus is still on preventing an individual perpetrator to not “reoffend,” however these therapeutic groups were also seen as mechanisms to prevent the intergenerational continuity of interpersonal violence. That is, by preventing men from re-abusing, they were reducing the likelihood that their children would become abusers themselves. Therefore by interrupting the cycle of violence, future generations would not model their abusive parent’s behaviors.

Generating individual and community awareness and providing education about violence against women

Primary prevention programs and events were also seen as tools for raising awareness about violence against women and educating individuals about the frequency and dynamics of domestic violence. The types of organizational activities or forums used to achieve these educational and awareness goals often include: one-time events such as walks or campaigns, community, campus and school-based presentations and tabling at community events such as health fairs. As one organizational representative from Africa stated: “But most of our prevention work revolves around raising levels of awareness, because we believe [people] have very little information” (#30,) illustrating that the distribution of information is seen as an important component of a prevention agenda. For some programs, the activities associated with information sharing and community awareness were not explicitly or conceptually linked to longer-term objectives related to prevention. For example, an organizational representative from North America who provides consulting and organizational support around primary prevention relayed a conversation he had with another anti-violence program to whom he was providing technical assistance:

“I was talking to the [domestic violence program] coordinator and I said: ‘So what’s the purpose behind your education events?’ She’s like: ‘Well, what do you mean?’ [I asked,] ‘Why do you want people to be aware of domestic violence? What’s your intent? What are you trying to change?’ And she only thought of it as just telling people it’s a problem. She never really thought about saying why am I organizing? What am I trying to get out of this awareness?” (#97).

In this example, the organization’s prevention agenda centers around sponsoring activities that have a primary intent of raising awareness about the existence of domestic violence, but displays a disconnect between how this increased community awareness could eventually translate to preventing violence against women. Rather than nesting increased awareness into a broader multilevel prevention agenda, the sole focus of this type of prevention effort is to increase the visibility of violence against women. What is missing is an articulation of the specific mechanisms that connect the activity to the overarching outcome of preventing violence against women.

Fostering Individual Competencies and Skill-Building

Beyond raising awareness that violence against women is a significant social issue, there was a related theme that primary prevention involves tangible skill-building and the nurturing of individual competencies to enact community-level changes. In other words, beyond just educating community members about the existence of domestic violence, there is a distinct goal “to develop… skills in people to actually make a change” (#47, Africa,). The programmatic activities that correspond with these goals can include campus and community based bystander programs and more intensive multiple session trainings. Organizational representatives emphasized that individual skill building as advocates and allies enabled them to become active change agents in their own communities. As organizational representative #108 who is employed at a multi-service, ecologically-oriented non-profit from Africa states: “We enable them to understand … the root cause of violence against women, as well as also help them to develop skills around how to prevent violence in their relationships, how do they prevent violence in their own communities, as well as they are taking action.” More specifically these skills can include knowing how to confront male peers making sexist comments, learning how to be empathetic and support survivors of violence and talking to ones’ male children about positive masculinity. Beyond just strengthening these individual competencies there is the implicit goal that these individuals will take the skills and tools they learned and bring them back to their own social networks. As organizational representative #34 who coordinates community education efforts with young men in Asia articulated: “Our strategy is that we’ll get people trained up and educated in the next ten months. [Then] we’ll have people who will get the tools and information and then hopefully they can replicate that within their small groups. So, hopefully in their families or in their group of friends, do some of the similar work.” This quote illustrates a desired diffusion effect whereby the nurturing of individual skills can spread back to the individual men’s social networks.

Redefining masculinity at the individual and community level

Another distinct conceptualization of prevention regards challenging dominant gender norms or notions of masculinity that both foster communities that are permissive to violence against women and that position men as inherently “violent. ” As organizational representative #61 from North America stated:

“What we say is men are naturally loving, caring and sensitive with women, children and other men …[it] is based on the assumption that … we’re not born with the violence genes or whatever… that we are taught and trained. The experiences that we have teach us to use violence as an acceptable and appropriate way to react to certain situations.”

The goal, in other words, is to help nurture a new kind of healthy masculinity that negates dominant social stereotypes about men’s biological or genetic propensity for violence. The types of programs used to achieve this goal include: universal school and community based bystander education programs, community education presentations, and campus and community-based men’s groups. The goal of these programmatic interventions is to go beyond just raising awareness about domestic violence, and to focus on dismantling the roots of violence against women—unhealthy gender norms. This approach is focused on “liberating” individual men from “the chains of masculinity and patriarchy” (#30, Africa) and in turn transforming broader social norms about masculinity. This is illustrated by the following two quotes:

“We’re looking at our own tendency of sexism as individuals… So engaging them in a way they can identify their participation or recognize how some kind of normal male interactions are supportive of violence of women, subordination of women and then‥ challenge them to step up and become active in confronting the… sexism in the culture.” (#96, North America).

“We’re fairly focused on targeting men and youth and campaigns that promote healthy ways to be men that try to recast some of the more prevalent notions of masculinity that are associated with men.” (#106, Asia).

Although individual men are still very much the vehicle for achieving social change, the emphasis on transforming the sexist underpinnings of violence against women underscores that these prevention approaches are interrelated to the broader social change approaches discussed in the next section.

Promoting long-term gender transformation and social change

The last prevention approach that emerged includes a broad category of promoting long-term social change. While some organizations defined prevention as promoting gender equality and others use language around the human rights of women, the core goal of these approaches was to focus on upstream or macro-level approaches that challenge the institutional and social norms that reinforce violence against women and girls. The following two organizational representatives capture the tenor of these approaches:

“Primary prevention is about preventing violence before it occurs in the first instant. So, it’s about systems and structures and understanding the key determinants of what can lead to violence, certain attitudes and behaviors are supportive of violence. I am working very much down at that end.” (#10, Australia).

“Our mission is to build a movement to prevent violence against women and we are focusing more our own social transformation, we are working towards changing norms, beliefs and attitudes that perpetrate violence against women because for us, our analysis of all kinds of violence is really about the root causes of violence, which is imbalance of gender between men and women. So, we are fostering a process of social change to create more equitable social norms and processes and relationships between men and women.” (#108, Africa).

Organizational representatives #10 and #108, both of whom engage in upstream activities such as community capacity building and coalition building, are emphasizing the benchmarks of primary prevention, which is to focus on the antecedents of violence against women and the social institutions that reinforce these dominant social norms.

There are additional noteworthy characteristics of organizations working at this level, including engaging in multilevel prevention efforts and devising a diversity of approaches to prevent violence. In general, the work reported by these organizations focus on upstream activities such as community capacity building, training other non-profits, media and policy advocacy and policing, and local, national and international coalition building. At the same time, these same organizations incorporated more grassroots activities such as hosting community theater events, anti-violence murals, and sponsoring informal “chats” in marketplaces about violence against women and girls. Organizational representative #32 from Africa emphasized how the utilization of multiple prevention approaches can help reach larger audiences. She states:

“So we do a whole range of things. So, there’s drama, there’s soap opera, a whole range of things recognizing that we have to reach people in many different ways, over many different times and many different people…[We do a] whole range of different tools because what’s going to speak to somebody is not probably going to speak to somebody” [else].

In terms of engaging in multilevel prevention approaches, organizational representative #47 from Africa underscored that there is a diversity of ways to get at the root causes of violence against women. She goes on to say:

“One of the things we try to do is not focus on manifestations of violence. But actually the core issue and for us that is the power imbalance between men and women…, kind of big picture. So, not just working with a set of survivors or a group of perpetrators, or a group of just regular community members, but everybody at the same time.”

Therefore, working with victims, perpetrators, bystanders and larger institutions in concert with one another can help chip away at the underlying issue of gender inequality that contributes to violence against women.

Burgeoning understandings of primary prevention

Although the majority of organizational representatives interviewed in this study conceptualized prevention somewhere along the continuum presented in Figure 1, it should be noted that a minority of interviewees provided emerging, though currently underdeveloped articulations of primary prevention. For instance, some responded to the question about defining prevention by describing specific activities the organization uses, rather than articulating the activities’ intended goals or the larger organizational perspective on prevention. One expressed skepticism about whether prevention was even possible: “Prevention is something which is not going to happen. It’s just a form of justifying ourselves to the funders, [to] the government…” (#49, Europe). Others noted that allowing prevention to be community-driven sometimes meant that goals shifted fluidly with the needs and context of a dynamic and changing population: “…our programming is very fluid, meaning we design programs on identified need and most of the time, the need arises from experiences, from our network” (#30, Africa). Similarly, as organizational representative #27 from Asia stated plainly that he is so consumed with the day-to-day operations of the program that he doesn’t “have much time to think about the philosophical aspect of our program,” and interviewee #49 from Europe concurred that rather than having a guiding prevention framework that their work is “tugged in the direction” of “people’s requests.”

DISCUSSION

Our analysis clearly showed that prevention is not a fixed term, but rather an array of understandings about primary prevention among programs partnering with men to combat violence against women. Primary prevention was conceptualized as everything from preventing new incidents of abuse to generating public awareness about intimate partner violence to actually organizing and advocating for institutional change. While some of these approaches would be consistent with Western public health frameworks like the Spectrum of Prevention, other strategies, such as engaging abusive men in treatment or discussion groups, would be defined within these existing frameworks as tertiary prevention efforts. However, we also saw examples of innovative multilevel prevention efforts that could serve as guides for more integrated approaches to prevention. In the following section we will discuss the emergence of this translational gap between public health and practice understandings of primary prevention, explore some of the lessons that can be learned from multilevel prevention efforts and present strategies for supporting organizations to develop foundational understandings of prevention.

Exposing a translational gap: blending of prevention approaches

While all of the interviewees contended that they were conducting primary prevention activities to engage men in violence prevention, it became clear that the majority of organizations were blending various primary, secondary and tertiary approaches in organizationally specific ways. The language of universal, selective, and indicated prevention efforts did not appear to infuse interviewees’ perspectives on primary prevention. We saw organizations that were engaging with men in single-service prevention activities such as batterer’s treatment, as well as multi-service agencies that conducted men’s groups in combination with community-level education and media campaigns. Interestingly, interviewees included all of these activities under a broad banner of primary prevention. While there was some consistency with the WHO’s (2007) description of types of primary prevention activities currently being conducted, the breadth of conceptualizations and activities revealed in this analysis expands the more finite distinctions between levels of prevention discussed in the existing literature. On the ground, these finite distinctions are broadened to include multi-level and tailored approaches.

Rather than critique some of these global efforts to engage men in violence prevention as “not primary prevention,” the blended approaches and broader organizational definitions of primary prevention raise important questions about how relevant clearly delineated Western public health frameworks, with prescribed definitions of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention approaches, are to the field of violence against women both globally and domestically. In this sense, it could be fair to say that there is a translational gap or mismatch between public health models of primary prevention and anti-violence organizations that are partnering with men in violence prevention. For example, while a batterers’ intervention program could easily be classified as tertiary prevention program in terms of hoping to reduce recidivism among perpetrators, if successful in reducing further perpetration, such an intervention can also be a tool of primary prevention by limiting the exposure of participating men’s children to additional violence as well as reaching broader audiences of men in the larger community.

What lessons can be learned from global multilevel prevention efforts?

While certainly not all organizations were engaging in multilevel prevention efforts to engage men and boys, those that were offer a potent place for learning how to move organizations beyond individual-level prevention agendas. There were a number of organizations that were modeling ecological prevention agendas consistent with public health prevention models, as well as some who blended prevention approaches in unique and organizationally specific ways.

As was consistent with the literature (WHO, 2010; Graffunder et al., 2011), there was a perception among some interviewees that organizations cluster their prevention efforts around raising awareness about the existence of violence against women, challenging individual attitudes and providing general community education. In many ways these activities to transform individual mindsets and attitudes can be seen as an entry-point for more expansive and multilevel prevention agendas. Rather than de-emphasizing or viewing individual-level change efforts as “less than,” these finding suggest that individual-approaches have the potential to diffuse multi-generationally and across social networks. Instead, efforts to transform individual attitudes via community education, skill-building or consciousness raising can be seen as a foundation from which to build larger, multilevel approaches that foster the development of more social-change oriented prevention agendas.

We learned from the varied organizational activities presented in interviews that strategies to engage men and boys in multilevel violence against women prevention efforts can be blended and adapted to meet unique organizational and community needs. Adaptable prevention approaches offer the hope of reaching diverse audiences and satisfying different programmatic aims. Traditionally individual-level strategies, such as batterer’s intervention programs, could be reconstituted to become spaces for challenging individual gender norms and attitudes, creating new visions of masculinity, and helping program participants become better fathers and family members. Similarly, community level approaches could be strengthened by focusing on individual men’s skill building such as found in young men’s bystander programs, so they can become active, knowledgeable and trained agents of social change within their family, social and community networks. In addition, as we heard from some of our organizational representatives engaging in multilevel change activities, hosting interactive theater events, creating community murals, and sponsoring dialogues about healthy masculinity and gender equality can be important tools for addressing some of the root causes of violence against women and capturing the attention of audiences of young men who may not participate in traditional community education forums. A number of organizational representatives also discussed the importance of fostering community level coalitions for both information sharing and for engaging non-traditional allies such as elected officials, clergy members and local business leaders. This approach also makes it possible for communities, as a whole, to engage in more expansive and interdisciplinary multilevel prevention efforts, that a smaller non-profit couldn’t do in isolation.

Supporting organizations in enhancing understandings of prevention

Beyond fostering the development of multilevel prevention agendas, our interviews also surfaced some organizational needs related conceptualizing and programmatically operationalizing prevention. A small number of interviewees struggled to articulate their conceptualization of prevention or expressed some skepticism about the project of prevention entirely. Others demonstrated difficulty linking their designated program activities to larger aims focused on reducing violence or to the mechanisms that would link their activities to individual or community change. For instance, some interviewees responded that primary prevention was hosting a single-session awareness event or workshop, but were less clear about how this activity was “preventing violence before it began” or “challenging dominant masculine norms.” Primary prevention, in this instance, took the form of workshops. Both challenges of having an unclear understanding of prevention, and of conflating of activities and objectives, could be addressed with more in-depth, theory-driven, contextualized and culturally relevant training or technical assistance that links agencies’ deep knowledge about their communities and culturally compelling approaches with strong theories for change.

Limitations

We must note here a number of significant limitations to this project. This research project was not designed to be a thematic analysis on the varying conceptualizations of primary prevention; this was an unexpected finding that we thought warranted further exploration. The MMVP project was a larger effort to describe global efforts and strategies for engaging men. Therefore our interview questions and research design reflect the original purpose of the study. Additionally, all of these interviews were conducted in English, which was not the majority of the interviewee’s first language. All of the interviews only occurred at one time point and not in person, which could hinder the development of a deep engagement between the interviewer and the interview participant (Stige et al., 2009). Also the nature of thematic content analysis can result in an attention to what is common rather than the unique features of individual cases (Ayres, et al., 2003).

CONCLUSION

Globally engaging men as partners and allies in the prevention of violence against women has emerged in conjunction with both greater calls to focus on public health inspired models of primary prevention and the development of more comprehensive multilevel strategies to prevent violence. The findings in this study raise important questions about the relevance of public health frameworks with rigid distinctions between prevention interventions to those working to end violence against women. However, this statement should not be taken as a repudiation of the importance of primary prevention, but rather an endorsement of more holistic prevention agendas that promote multilevel approaches to combat gender-based violence. More expansive understandings of prevention, including an acknowledgement that there is significant overlap between various levels of prevention, could help ameliorate the tension between prevention and intervention priorities in organizational settings. Furthermore, a greater congruence between funding agencies and influential global stakeholders, that prescribe public health conceptualizations of prevention and direct service providers’ more fluid understandings’ of primary prevention is an important first step for developing and implementing contextualized and organizationally specific prevention programs that have the capacity to catalyze broad-scale change.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This research was supported by the University of Minnesota, College of Education and Human Development, International Research Grant Program and by NIMH grant T32MH20010. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Biographies

Heather Storer, MSW is a doctoral candidate at the University of Washington School of Social Work and is an ITHS TL1 scholar through the National Institute of Health. She has worked nationally in the fields of dating and domestic violence prevention, and positive youth development. Her research agenda broadly focuses on strategies to meaningfully engage youth as partners in the prevention of dating abuse and other high-risk behaviors. Her current work is exploring how social norms in adolescents’ micro, mezzo, and macro environments influence their active participation in intervening in dating abuse among their peers.

Erin Casey, PhD is an Associate Professor of Social Work at the University of Washington, Tacoma. She received her MSW and PhD in Social Welfare at the University of Washington, Seattle. Erin’s research examines the the etiology of sexual and intimate partner violence perpetration and ecological approaches to violence prevention, including engaging men proactively as anti-violence allies and proactive bystanders, and exploring intersections between violence, masculinities, and sexual risk.

Juliana Carlson, AM, PhD is currently an Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas School of Social Welfare. She received her doctorate from the University of Minnesota School of Social Work. In addition to a research interest in an international understanding of engaging men in the prevention of gender-based violence, Juliana’s interests include the interconnected issues of child exposure to domestic violence, child welfare and poverty, specifically how organizations impact expectant and new fathers’ experiences within community and economic contexts, and interventions that prevent family violence.

Jeffrey L. Edleson, PhD, is Dean and Professor in the University of California, Berkeley School of Social Welfare. He is Professor Emeritus in the University of Minnesota School of Social Work and founding director of the Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse. He has published more than 120 articles and 12 books on domestic violence, group work, and program evaluation. Edleson served on the National Advisory Council on Violence Against Women and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare.

Richard M. Tolman, PhD is a Professor at the University of Michigan, School of Social Work. His work focuses on the effectiveness of interventions designed to change abusive behavior, and the impact of violence on the physical, psychological and economic well-being of victims. His current projects include research on prevention of abuse during pregnancy, adolescent partner violence and involvement of men and boys as allies to end violence against women.

Contributor Information

Heather L. Storer, University of Washington, Seattle, School of Social Work, 4101 15th Avenue NE, Seattle, Washington 98105, hlstorer@uw.edu, p: 408.547.7036, f: 206-543-1228

Erin A. Casey, University of Washington, Tacoma, ercasey@uw.edu.

Juliana Carlson, University of Kansas, School of Social Welfare, jmcarlson@ku.edu.

Jeffrey L. Edleson, University of California, Berkeley, jedleson@berkeley.edu.

Richard M. Tolman, University of Michigan, School of Social Work, rtolman@umich.edu.

REFERENCES

- Ayres L, Kavanaugh K, Knafl KA. Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(6):871–883. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Black MC. Intimate partner violence against women. In: Renzetti Claire M, Edleson JL, Bergen RK., editors. Sourcebook on Violence Against Women. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2011. pp. 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Taylor TK. Why we have been more successful in reducing tobacco use than violent crime. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:269–302. doi: 10.1023/A:1005155903801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J, Casey EA, Edleson J, Tolman R, Neugut T, Kimball E. Strategies to engage men and boys in violence prevention: a global organizational perspective. Violence Against Women. doi: 10.1177/1077801215594888. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Carlson J, Fraguela-Rios C, Kimball E, Neugut T, Tolman R, Edleson JE. Context, challenges, and tensions in global efforts to engage men in the prevention of violence against women: An ecological analysis. Men and Masculinities. 2013;16:227–249. doi: 10.1177/1097184X12472336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual violence prevention: beginning the dialogue. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain L. A Prevention Primer for Domestic Violence. VAWnet Applied Research Forum. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.vawnet.org/Assoc_Files_VAWnet/AR_PreventionPrimer.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Chehimi S. The imperative for primary prevention. In: Cohen L, Chavez V, Chehimi S, editors. Prevention is Primary. San Francisco, CA: Bass; 2010. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research Methods in Education. 6th edition. London: Routledge-Falmer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research. London: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flood M. Involving men in efforts to end violence against women. Men and Masculinities. 2011;14(3):358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Linder GF, Benefield T, Suchindran C. Assessing the long-term effects of the Safe Dates program and a booster in preventing and reducing adolescent dating violence victimization and perpetration. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:619–624. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WR, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, Mercy J, Chin P. Setting a violence prevention agenda at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. An Integrated, Ecological Framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Center for Research on Women. Reducing HIV Stigma and Gender Based Violence Toolkit for Health Care Providers in India. 2007 Available: http://www.icrw.org/publications/reducing-hiv-stigma-and-gender-based-violence-toolkit-health-care-providers-india. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: Cluster randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:391–395. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG. What is violence against women: Defining and measuring the problem. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1209–1234. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50(4):459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffunder CM, Cline R, Lane KG. Primary prevention. In: Renzetti CM, Edleson JL, Bergen RK, editors. Sourcebook on Violence Against Women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2011. pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- McPhail BA, Busch NB, Kulkarni S, Rice G. An Integrative Feminist Model. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(8):817–841. doi: 10.1177/1077801207302039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. Defining the scope of prevention. In: O’Connell ME, Boat, Warner, editors. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People. Washington D.C: The National Academies Press; 2009. pp. 59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prothrow-Stith D, Davis RA. A public health approach to preventing violence. In: Cohen L, Chavez V, Chehimi’s S, editors. Prevention is Primary. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. pp. 323–350. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ostrom A, Bitner MJ, Ayers TS, Wolchik S, Daniels VS, et al. Developing effective prevention services for the real world: A prevention service development model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35(3/4):127–142. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter S. Women and Male Violence. Boston, MA: South End; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM. Theories of primary prevention and health promotion. In: Gullotta TP, Bloom M, editors. Encyclopedia of primary and health promotion. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Pub.; 2003. pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stige B, Malterud K, Midtgarden T. Toward an agenda for evaluation of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(10):1504–1516. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Edleson JL. Intervening with men for violence prevention. In: Renzetti CM, Edleson JL, Bergen RK, editors. Sourcebook on Violence Against Women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 2011. pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Defining violence against women and girls. 2012 Available: http://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/295-defining-violence-against-women-and-girls.html. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Delaying Marriage for Girls in India. 2011 Available: http://www.icrw.org/publications/delaying-marriage-girls-india. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Primary prevention of intimate- partner violence and sexual violence: Background paper for WHO expert meeting. 2007a Available: http://www.nsvrc.org/publications/reports/primary-prevention-intimate-partner-violence-and-sexual-violence-background-pa-0.

- World Health Organization. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: Evidence from programme interventions. 2007b Available: http://www.who.int/gender/documents/Engaging_men_boys.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Violence Prevention: The evidence. 2009 Available: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/gender.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women. 2010 Available: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564007/en/index.html.

- Yllo K, Bograd M. Feminist Perspectives on Wife Abuse. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]