Abstract

While parent and youth substance use prevention interventions have shown beneficial effects on preadolescents, many programs have typically targeted U.S born European American and African American families while overlooking the unique factors that characterize recent immigrant Latino families. This article presents the results on youth substance use when adding a culturally grounded parenting component, Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación (FPNG), to the existing and already proven efficacious classroom-based drug abuse prevention intervention, keepin’it REAL (kiR). Data come from youth (N=267) participating in the randomized control trial of the interventions who were surveyed at baseline (beginning of 7th grade) and 18 months later (end of 8th grade). Using multivariate linear regression path analyses, results indicate when FPNG and kiR are combined, youth had significantly lowered alcohol and cigarettes use at the end of 8th grade, mediated through anti-drug norms, when compared to youth who only participated in kiR without parental participation in FPNG. These findings indicate that adolescent normative beliefs and related behaviors can be changed through synchronized culturally grounded parent and youth interventions and together can play an important role in reducing adolescent substance use.

Keywords: substance use, interventions, adolescents, parents, Latino

Substance abuse prevention efforts have traditionally addressed youth substance use by directly targeting youth’s norms and behaviors (Brody et al., 2006; Spoth et al., 2009). More recently, parent or family focused prevention interventions have demonstrated adolescent decreases in the likelihood of initiating use, declines in the rate of growth, and increases in positive outcomes into adulthood, including increased socioeconomic success, reduced mental health disorders, and lowered prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (Brody et al., 2006; Spoth et al., 2009). Despite the apparent effectiveness of both of these approaches, few prevention interventions have synchronized the delivery of prevention efforts to youth and their parents, an approach that may strengthen the effects of the interventions than when conducted independently.

This synchronized approach to substance abuse prevention may be even more salient for Latino families given the impact of acculturation on family dynamics. Foreign-born Latino families have unique cultural and immigration factors impacting family functioning, parenting skills, and youth behaviors. For example, differential acculturation between parent and youth may exacerbate adolescent problem behaviors, including substance use (Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009; Voisine, Parsai, Marsiglia, Kulis, & Nieri, 2008). Thus, for Latino families, having a culturally grounded family-centered synchronized prevention intervention is key - as culturally grounded interventions have been shown to be more effective at communicating intervention messages, retaining participants, and impacting outcomes (Kulis et al., 2005; Dumka, Lopez, & Jacobs-Carter, 2002). This article presents the results on youth substance use when adding a culturally grounded parenting component, Families Preparing the New Generation (Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación)(FPNG), to the existing and already proven efficacious classroom-based drug abuse prevention intervention, keepin’it REAL (kiR) (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005). Drawing from the primary socialization theory and the theory of planned behavior, this article examines how these synchronized curricula reduce youth substance use mediated through strengthening youth’s anti-drug norms.

Transmission of Norms in the Family Context

Primary socialization theory (PST) states that substance use behaviors, like other behaviors, are learned through social interactions with family, school, and peers (Oetting & Donnermeyre, 1998). In the family, for norms to be successfully transmitted, two things must be present: 1) a strong bond; and 2) effective anti-substance use communication. Weak familial attachments or unclear norms about substance use increase the youth’s likelihood of adopting deviant substance use norms of peers (Oetting & Donnermeyre, 1998). Although there are certainly families where members engage in substance use and transmit deviant norms; more frequently, family bonds are eroded when parents do not have the skills to maintain healthy communication during the period of adolescent development (Oetting & Donnermeyre, 1998).

Norms in the family can be communicated verbally and through modeling. Effective and bidirectional verbal communication allows parents to provide feedback to their adolescents about what behaviors are acceptable, lowering the risk of delinquent behaviors (Davidson & Cardemil, 2009; Kelly, Comello, & Hunn, 2002). When parents model substance use behaviors, norms regarding the acceptability of using substances are reinforced to the adolescent (Andrews, Hops, & Duncan, 1997). When parents model substance use, their youth are more likely to develop substance use problems in adulthood (Walden, Iacono, & McGue, 2007).

The Impact of Acculturation on Transmission of Family Norms and Modeling

It has been hypothesized that the process of acculturation impacts Latino youth substance use (Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009), as reflected by the higher level of substance use among more acculturated Latino youth (De La Rosa, Holleran, Rugh, & MacMaster, 2005). Although acculturation can have positive effects on individuals - allowing them to succeed in the mainstream American society - acculturation may also erode the protective nature of cultural factors such as traditional family values and beliefs, family connections, and parenting processes (Bamaca-Colbert, Gayles, & Lara, 2011; Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009). These disruptions, however, may not occur if protective Latino cultural norms are retained within the family (Marsiglia et al., 2012).

Because youth are typically acculturating faster than their parents (Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006), studies have suggested that these differential rates of acculturation may lead to disruptions in the parent- child relationship, parental monitoring, and parent-child communication (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Marsiglia, Nagoshi, Parsai, & Castro, 2012; Martinez, 2006). Having a large discrepancy in acculturation levels between parents and adolescents weakens the parent’s ability to effectively communicate and transmit norms, values, and expectations (Martinez, 2006); and in turn, results in increased adolescent substance use (Marsiglia et al., 2012; Martinez, 2006).

Transmission of norms for adolescent behavior change

The path between transmissions of norms to adolescent behavior change is best explained by the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991). TPB theorizes that attitudes, norms, and perceptions influence intentions, which in turn, drive behavior (Ajzen, 1991). It has been argued that attitudes and perceptions are based on norms (Keyes et al., 2012), thus norms are the precursor to driving behaviors. Furthermore, studies have found that norms have a direct effect on substance use behaviors (Keyes et al., 2012; Eisenberg & Forster, 2003). Following a more direct association between norms and behaviors, it is theorized that, over time, as events occur that change or alter norms, behaviors are revised and changed (Ajzen, 2011). Thus, TBP is an important theory in determining the antecedents of substance using behaviors and has been shown to successfully predict experimental substance use (Harakeh et al., 2004).

Parents have the potential to affect both the associations and beliefs related to substance use and establish subjective norms regarding use. Norms surrounding substance use can be positively influenced by parents through a quality parent-child relationship, including warm communication and parental monitoring (Harakeh, et al., 2004; Perez & Cruess, 2014). Although parents have the greatest impact on adolescent behavior, previous research has shown that prevention programs that engage both parents and youth are more effective than those that target either parents or children (Kumpfer, Molgaard & Spoth, 1996). The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) provides a theoretical foundation for explaining why multiple influential systems -including parenting- can lead to behavioral changes in adolescents through affecting adolescent norms concerning substance use.

Purpose of This Study

Initial efficacy results have been noted on strengthening open communication (Williams, Ayers, Garvey, Marsiglia, & Castro, 2012), improving positive parenting practices (Marsiglia, Williams, Ayers, & Booth, 2013), and decreasing heavy episodic drinking in parents when compared to the control group (Williams, Marsiglia, Baldwin, & Ayers, 2014). This article presents the results of the longer term (18 months) effects on youth’s substance use through changing anti-drug norms. It is hypothesized that: (1) youth who had parents participate in FPNG will have lower substance use at the end of 8th grade compared to youth who only received kiR; and (2) these effects will be mediated through strengthening youth’s anti-drug norms.

Methods

Because kiR is a universal school-based program, all participants (parents and youth) were recruited at the school the youth attended. Eligible schools were those that had a large percentage (>70%) of Latino students and were located within the boundaries of the city of Phoenix. After block randomization, nine schools were randomized into three conditions (3 schools per condition): Parent &Youth (PY), Youth Only (Y), and Control (C). Because this study is focused on youth who had parents participate in FPNG (PY) compared to youth who only received kiR (Y), the C group is not included in the analyses. Thus, for the remainder of the paper, only two groups will be discussed – PY and Y.

Participants & Procedures

All 7th grade students and their parents were eligible to participate in the study. Trained study personnel initiated recruitment procedures in each 7th grade classroom. Youth were told about the program, and parental consents were sent home with each adolescent. In addition, all 7th grade parents with a valid phone number were simultaneously recruited to attend an informational “cafecito” - social gatherings where refreshments are served and a topic of interest to parents is discussed. Parents were invited to participate in the FPNG program or just cafecitos in the future. The parents that participated in the study were overwhelmingly female (82.8%), 38.5 years old, had completed some high school but did not have a diploma (34.7%), and were married or cohabitating (76.4%). Ninety percent reported a Latino ethnicity, and over half of the parents spoke only Spanish (53.5%) compared to 3.5% who spoke only English.

Because kiR is a universal prevention program delivered during regular school hours by regular classroom teachers, youth only receiving the programming were not asked to provide assent in order to receive the curriculum. The survey administration did require active parental permission and youth assent. Separate and apart from the youth procedures, parents were invited to attend a parenting program. The parents did not have to consent in order to participate in the program. The parental survey administration did require an active consent. While all 7th grade students and their parents were invited to participate, because of the voluntary nature of this research study, there were instances of parents or youth receiving the intervention while declining to participate in data collection for the research study. While data were collected on all consented adults and permissioned youth, only those families in which both a parent and youth participated in the data collection (38%) were included in the final sample of the study. It should be noted that youth were more likely to have parents participate if the family lived in a two-parent household; and in the Y group, lower academic grades predicted greater parent participation.

In compliance to Institutional Review Board requirements, youth completed surveys at three data collection points: (W1) Wave 1 was collected in the fall (September – November) semester, at the beginning of the youth’s 7th grade year, and prior to any intervention; (W2) Wave 2 was collected in the spring (March–May) of the same school year, at the end of 7th grade, and after completion of the intervention; and (W3) Wave 3 was collected in the spring (March–May) of the following school year, at the end of the youth’s 8th grade – 18 months post baseline. The sample for this study includes those 7th grade youth whose parents also consented to participate in the study and who completed the basic demographic questions at W1 (N=267).

Each school had a three-person bilingual field team who ensured coordination between the youth and parent interventions: (1) Facilitators delivered the parenting curriculum, FPNG or the cafecitos, to parents; (2) Parent Coordinators assisted the facilitators during the curriculum delivery and worked closely with school parent liaisons to support parents; and (3) School Liaisons worked with the youth and supported the classroom teachers during kiR. The team that developed the FPNG facilitator manuals also facilitated and delivered the curriculum to all parent participants; and provided fidelity. All members of the field team were employed and supervised by the research team. Formal weekly meetings were held between the field team and research team to ensure proper coordination of the interventions, as described below.

keepin’ it REAL & Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación

keepin’ it REAL (kiR) is a National Model Program identified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). This culturally grounded, evidence-based substance use prevention program for middle school youth is designed to: (a) strengthen the use of drug resistance skills; (b) advance anti-substance use attitudes and norms; and (c) improve decision making and communication skills (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005). Delivered by teachers in regular school classrooms during the regular school day, this 10-week program teaches the REAL drug resistance strategies – Refuse, Explain, Avoid, and Leave (R-E-A-L; see Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2003). kiR was initially tested in a randomized control trial with 35 schools and 6,035 youth over a 48-month period. Results indicated youth in kiR had significantly less alcohol use, cigarette use, and pro-drug norms over time when compared to a control group (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005). The intervention was also found to be effective for Latino youth, with stronger effects found for English-language dominant Latino youth, the most at-risk sub-group (Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005). Latinos who spoke primarily Spanish used fewer substances at the beginning of the intervention and continued to use less at the end, consistent with traditional cultural norms that discourage substance use (Marsiglia, et al., 2005).

While kiR demonstrated efficacy for youth at post-intervention and follow-up (Hecht et al., 2003), the developers, in partnership with community members, reengaged in community-based participatory research to develop the parenting curriculum, Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación (FPNG) (see Parsai, et al., 2011). FPNG is drawn from the efficacious kiR (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005) and Familias Unidas programs (Prado et al., 2012). Like Familias Unidas, FPNG is a culturally-specific, prevention intervention for Latino families that is guided by the Ecodevelopmental Theory (Pantin et al., 2003; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) and supports strengthening family functioning as a means of preventing adolescent substance use and other risky behaviors (Perrino et al., 2014; Prado et al., 2012; Perrino, Gonzalez-Soldevilla, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2000; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). FPNG is designed as a universal parenting curriculum and specifically integrates the R-E-A-L drug-resistance strategies the adolescents are learning in the kiR curriculum.

The overall goals of the FPNG curriculum are to: (a) empower parents to help their adolescent to resist substance use by employing the R-E-A-L strategies; (b) build and strengthen family functioning to foster pro-social behavior in adolescents; and (c) increase communication skills and problem solving abilities within the family. The FPNG curriculum includes eight workshops: (1) You Are Not Alone: participants identify support networks; (2) Introduction to keepin it REAL: participants learn the R-E-A-L strategies; (3) Knowing Your Child’s World: participants gain knowledge on adolescent development; (4) Communicating with Your Child: participants develop positive, respectful, and supportive ways of communication; (5) Giving & Receiving Support: participants identify how to foster a positive, respectful, and supportive relationship; (6) Managing Your Child’s Behavior Effectively: participants practice skills like positive parenting practices and parental monitoring; (7) Talking with Teens about Risky Behaviors: parents practice how to have sensitive conversations; and (8) Putting It All Together: parents review key elements from previous workshops.

The manualized facilitated curriculum uses didactic methods as the primary mode of delivery. The curriculum is designed to provide learning opportunities through a variety of methods – listening, observing, writing, reflecting, and practicing. For example, parents have opportunities to learn through role playing activities, discussing scenarios in small groups, watching videos and talking about them in large groups, and reflecting through writing what they have learned. FPNG was delivered by trained bilingual facilitators in either English-only or Spanish-only intervention groups (the great majority were conducted in Spanish) at the school their youth attended. Parents met once a week over an eight-week period, with groups typically occurring in the early evening or on weekends. Childcare was provided free-of-charge for parents. Parents, on average, attended 6 of the 8 workshops, with 69% completing the program.

The kiR and FPNG programs are synchronized interventions in skills, strategies, concepts, and processes. For example, while youth in the kiR intervention are learning about I-statements, norms, and values, parents in FPNG intervention are learning the same information with similar activities. In both curricula, the four substance use resistance strategies are taught – Refuse, Explain, Avoid, and Leave – with both parents and youth watching the same videos and doing similar role playing exercises. Parents are also given homework assignments to complete at home with their adolescent to reinforce the concepts learned in both curricula.

Measures

Substance Use at W3

Past month’s amount of youth substance use was examined. Substance use was self-reported by the youth, and for the remainder of the paper, the mention of “substance use” will coincide with self-reported substance use. Substance use was assessed by how much (amount) and how often (frequency) youth used alcohol and cigarettes, using developmentally appropriate questions for this age group (Kandel & Wu, 1995). For alcohol amount, youth were asked, “How many drinks of alcohol (more than a sip of beer, wine, or liquor) have you had in the last 30 day” with responses ranging from (1) none to (7) more than 30 drinks. Alcohol frequency measured the number of times in the last 30 days the youth had “drunk more than a sip of alcohol (beer, wine, or liquor),” with responses ranging from (1) zero times to (7) 40 or more times. Cigarette amount was measured by asking the youth, “How many cigarettes have you smoked in the last 30 days?” with responses ranging from (1) none to (7) more than 20 cigarettes. To measure cigarette frequency, adolescents noted the number of times they had “smoked cigarettes in the last 30 days” from (1) zero times to (7) 40 or more times.

Antidrug Norms at W3

Youth’s norms surrounding the acceptability of using substances were measured separately for alcohol and cigarettes. Youth were asked, “Is it OK for someone your age to drink alcohol [smoke cigarettes]?” Responses ranged from (1) definitely ok to (4) definitely not ok.

Treatment Group

For the purposes of these analyses, the PY group, in which parents received FPNG and their youth received kiR, will be compared to the Y group, in which youth received kiR, but parents did not receive FPNG.

Statistical Analyses

Using Mplus, version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012), multivariate linear regression path analyses were conducted to determine if youth in the PY group had lowered alcohol and cigarette use compared to the Y group, and if antidrug norms mediated the effect. For each model, the direct effects of substance use on the PY group compared to the Y group were estimated; while simultaneously testing if youth in the PY group would have significantly different anti-drug norms, which, in turn, would reduce substance use. In each model, the W1 control variables include amount and frequency of substance use, anti-drug norms, US born (compared to non-US born), free lunch status at school, gender, and usual grades in school. It should be noted that additional analyses were examined including growth curve models to assess significant group differences in substance use trajectories over the three waves of data, as well as, testing if family processes (parental monitoring, parent-child communication, and positive parenting practices) mediate the impact of the intervention on frequency and amount of youth substance use. These analyses showed no significant differences between the PY group and the Y group.

Of the 289 youth participating in the study, 22 were missing on the W1 demographic control variables and were excluded from the analyses. The remaining youth (N=267) had an attrition rate at W3 of 19.1%, with the Y group having a higher attrition rate. To account for missing data, full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) with robust standard errors was used. Three goodness of fit statistics evaluate the overall model fit: (1) the normed chi-square (Χ2/df), with acceptable fit less than 5.0 (Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977); (2) the CFI, with acceptable fit greater than .90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999); (3) the RMSEA, with good fit equaling less than .08 (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). The standardized betas (β) are reported for the direct and indirect paths.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the sample are presented in Table 1. At W1, the PY group has a higher frequency and amount of alcohol use; however by W3, the higher alcohol use for both frequency and amount are seen in the Y group. For cigarette use, the PY group remains stable between W1 and W3, while the Y group increases across waves. For both groups, there is a decrease in anti-drug norms between W1 and W3 – by the end of 8th grade youth are reporting it is “more OK” to use alcohol and cigarettes. Demographically, the two groups are similar to each other. Youth have grades in school that are, on average, mostly B’s with some C’s. The overwhelming majority was born in the US and received free lunch at school. There were slightly more boys than girls in the sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of analytic sample (N=267).

| Treatment Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent & Youth (PY) | Youth Only (Y) | |||||

| N=117 | N=150 | |||||

| M (%) | SD | N | M (%) | SD | N | |

| Alcohol Use | ||||||

| Alcohol Frequency (w1) | 1.27 | .77 | 116 | 1.16 | .52 | 147 |

| Alcohol Frequency (w3) | 1.40 | .93 | 101 | 1.61 | 1.23 | 113 |

| Alcohol Amount (w1) | 1.36 | .78 | 116 | 1.32 | .76 | 149 |

| Alcohol Amount (w3) | 1.59 | 1.34 | 101 | 1.81 | 1.52 | 114 |

| Cigarette Use | ||||||

| Cigarette Frequency (w1) | 1.03 | .23 | 116 | 1.04 | .20 | 145 |

| Cigarette Frequency (w3) | 1.03 | .17 | 100 | 1.28 | 1.11 | 113 |

| Cigarette Amount (w1) | 1.03 | .18 | 115 | 1.09 | .42 | 148 |

| Cigarette Amount (w3) | 1.02 | .14 | 101 | 1.25 | .93 | 114 |

| Anti-Drug Norms | ||||||

| Anti-Alcohol Norms (w1) | 3.60 | .66 | 117 | 3.59 | .59 | 148 |

| Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) | 3.38 | .73 | 101 | 3.09 | .89 | 113 |

| Anti-Cigarette Norms (w1) | 3.81 | .45 | 117 | 3.73 | .47 | 149 |

| Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) | 3.67 | .57 | 101 | 3.46 | .73 | 112 |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Usual grades in school | 3.26 | 1.6 | 117 | 2.84 | 1.32 | 150 |

| Born in the US (w1) | (77.78%) | 117 | (81.33%) | 150 | ||

| Gender-Female (w1) | (47.01%) | 117 | (46.67%) | 150 | ||

| Free lunch in school (w1) | (88.03%) | 117 | (83.33%) | 150 | ||

The means for usual grades in school are between (3) Mostly B’s and (4) B’s and C’s.

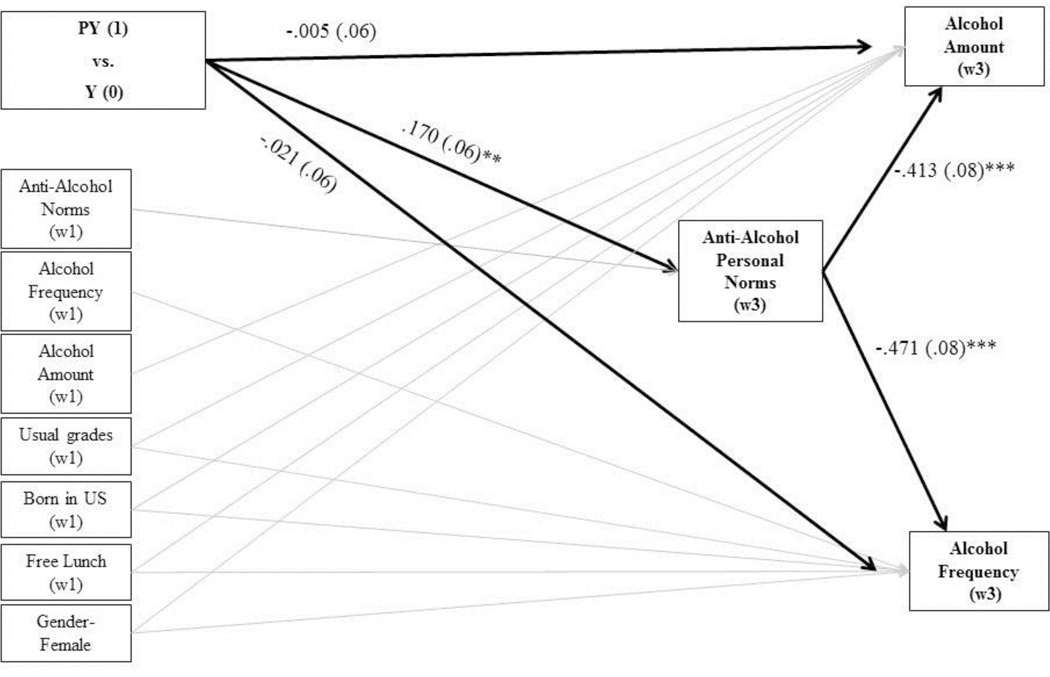

Figure 1 and Table 2 present the path analysis of alcohol amount and frequency. Compared to the Y group, the PY group has no direct effects on alcohol amount (β=−.005, p=.93) or alcohol frequency (β=−.021, p=.71). The PY group has significantly stronger anti-alcohol norms, compared to those youth in the Y group (β=.170, p<.01), and having stronger anti-alcohol norms is associated with a significantly lower amount of alcohol use (β=−.413, p<.001) and frequency of use (β=−.471, p<.001) at W3. There are significant indirect effects of the intervention. The indirect path between the PY group and alcohol amount is mediated through anti-alcohol norms (β=−.070, p<.05). Similarly, the indirect path between the PY group and alcohol frequency through anti-alcohol norms is significant (β=−.08, p<.05). The majority of the effect of the intervention on alcohol use is explained through the mediated path − 93% for alcohol amount and 79% for alcohol frequency. While the chi-square statistic is significant (Χ2=37.69(25), p<.05), the normed chi-square of 1.51, the CFI of .93, and the RMSEA of .04 all indicate a good fitting model.

Figure 1.

Path analysis of alcohol amount and frequency on receipt of keepin’ it REAL and Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación mediated through anti-alcohol norms (N=267)

Table 2.

Standardized parameter estimates of alcohol amount and frequency on receipt of keepin’ it REAL and Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación (N=267)

| Direct Effects | β | S.E. |

|---|---|---|

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | −.005 | .06 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | −.021 | .06 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) | .170** | .06 |

| Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | −.413*** | .08 |

| Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | −.471*** | .08 |

| Indirect Effects | ||

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) Alcohol Amount (w3) | −.070* | .03 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) Alcohol Frequency (w3) | −.080* | .03 |

| Control Variables | ||

| Alcohol amount (w1) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | .090 | .06 |

| Alcohol frequency (w1) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | .003 | .08 |

| Usual grades in school (w1) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | −.023 | .06 |

| Usual grades in school (w1) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | −.048 | .06 |

| Born in the US (w1) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | −.098 | .07 |

| Born in the US (w1) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | .016 | .06 |

| Gender-Female (w1) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | .005 | .06 |

| Gender-Female (w1) Alcohol Frequency (w3) | −.004 | .07 |

| Free lunch in school (w1) → Alcohol Amount (w3) | .059 | .06 |

| Free lunch in school (w1) → Alcohol Frequency (w3) | .012 | .06 |

| Anti-alcohol norms (w1) → Anti-Alcohol Norms (w3) | .250*** | 007 |

| Goodness of Fit Indices | ||

| Χ2 (df) | 37.69 (25)* | |

| CFI | .927 | |

| RMSEA | .044 | |

p<.001.

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<.10

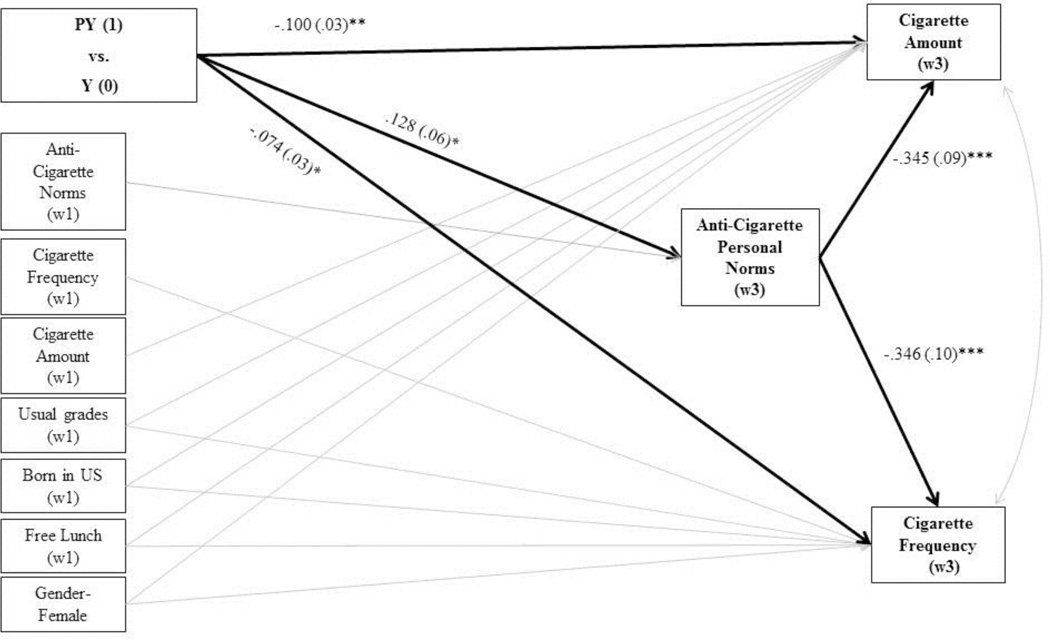

Figure 2 and Table 3 present the path analysis of cigarette amount and frequency. The PY group, compared to the Y group, has a direct effect on lowering the amount of cigarettes smoked (β=−.100, p<.01) and in reducing the frequency of smoking cigarettes (β=−.074, p=<.05). Youth in the PY group have stronger anti-cigarette norms compared to those in the Y group (β=.128, p<.05). Stronger anti-cigarette norms is associated with a significantly lower amount of cigarettes smoked (β=−.345, p<.001) and a decrease in frequency of smoking cigarettes (β=−.346, p<.001) at W3. The indirect path between the PY group on lowered cigarette amount (β=−.044, p<.10) and cigarette frequency (β=−.043, p<.10) through anti-cigarette norms is marginally significant. For cigarettes, the majority of the effect is explained through the direct path, with only 7% and 31% of the effect on cigarette frequency and cigarette amount explained through the indirect path. The chi-square statistic is not statistically significant (Χ2=33.10(24), p=.102). The normed chi-square of 1.38, the CFI equaling .906, and the RMSEA of .038 are well below the desired levels.

Figure 2.

Path analysis of cigarette amount and frequency on receipt of keepin’ it REAL and Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación mediated through anti-cigarette norms (N=267)

Note: Control variables are presented with light gray lines. Coefficients and significance levels are presented in Tables.

Table 3.

Standardized parameter estimates of cigarette amount and frequency on receipt of Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación (N=267)

| Direct Effects | β | S.E. |

|---|---|---|

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | −.100** | .03 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | −.074* | .03 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) | .128* | .06 |

| Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | −.345*** | .09 |

| Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | −.346*** | .10 |

| Indirect Effects | ||

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) → Cigarette Amount | −.044† | .03 |

| PY (1) vs. Y (0) → Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) → Cigarette Frequency | −.043† | .03 |

| Control Variables | ||

| Cigarette amount (w1) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | .179 | .12 |

| Cigarette frequency (w1) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | .407 | .41 |

| Usual grades in school (w1) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | .059 | .06 |

| Usual grades in school (w1) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | .085 | .07 |

| Born in the US (w1) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | .058† | .04 |

| Born in the US (w1) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | .067† | .04 |

| Gender-Female (w1) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | .073 | .07 |

| Gender-Female (w1) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | −.028 | .07 |

| Free lunch in school (w1) → Cigarette Amount (w3) | −.023 | .09 |

| Free lunch in school (w1) → Cigarette Frequency (w3) | −.016 | .08 |

| Anti-Cigarette norms (w1) → Anti-Cigarette Norms (w3) | .202** | .08 |

| Goodness of Fit Indices | ||

| Χ 2 (df) | 33.10 (24), p=.102 | |

| CFI | .906 | |

| RMSEA | .038 | |

p<.001.

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<.10

Discussion

This randomized control trial of keepin’ it REAL complemented with Familias Preparando la Nueva Generación provides evidence that involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention intervention can be efficacious in curbing Latino adolescent substance use over time. This is particularly important given that Latino 8th graders are consistently drinking more than their non-Latino counterparts (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013). For Latino families, having interventions designed and tailored to cultures of origin, cultural assets and strengths, and other cultural characteristics provide promising evidence that involving the family is an effective way to reduce adolescent substance use. The combination of kiR and FPNG appears to be particularly potent as family-focused prevention interventions have been shown to decrease the likelihood of substance use in later adolescence and into adulthood (Brody et al., 2006; Spoth et al., 2009) – a finding echoed in this study by the decrease in substance use in Latino adolescents 18 months after participating in the prevention program.

The ecodevelopmental perspective integrated with primary socialization theory and theory of planned behavior appropriately guided this study’s hypotheses. The first hypothesis stated that youth who had parents participate in FPNG would have lower substance use at the end of 8th grade compared to youth who only received kiR. While there were no direct effects seen on lowering alcohol use, youth who participated in kiR and whose parents participated in FPNG had significantly lowered cigarette amount and frequency by the end of 8th grade – a finding that only partially supports the first hypothesis. This can be compared to the original kiR study in which youth who participated in the intervention reported significantly less alcohol use at the end of 8th grade and less cigarette use at earlier waves when compared to the control group (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005). The second hypothesis, the effects will be mediated through youth’s anti-drug norms, was supported for both alcohol and cigarettes. In comparison to only youth who received kiR, adolescents receiving kiR and the parent receiving FPNG, have stronger anti-drug norms. In turn, having stronger anti-drug norms reduced both alcohol and cigarette use. Again this can be contrasted with the original trial of kiR, in which the differences in anti-drug norms were significant at earlier waves but dissipated by the end of 8th grade (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005).

These findings support the primary socialization theory and indicate that having a synchronized parenting intervention appears to aid parents to engage in effective anti-substance use communication and modeling behaviors to transmit norms regarding appropriate behavior. When parents maintain healthy communication and model appropriate substance use behaviors, adolescent pro-social norms are strengthened (Oetting & Donnermeyre, 1998). Prior studies examining the efficacy of FPNG have found that parents participating in the intervention strengthened their positive parenting practices (Marsiglia et al., 2013), enhanced their open family communication (Williams et al., 2012), and reduced heavy alcohol drinking (Williams et al., 2014), indicating that “known parenting practices relevant to reducing adolescent risk behavior are malleable to change.” (Williams et al., 2012, p. 302). The results presented in this article contribute to the existing knowledge by providing further evidence that a parenting intervention can strengthen anti-drug norms in Latino adolescents.

The theory of planned behavior is also relevant in understanding the findings of this study and endorses prior research which found that TPB can be used to predict experimental substance use (Harakeh et al., 2004). TPB suggests that norms change first, followed by behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The models in the study indicate that the synchronized parents and youth substance use interventions influence the proximal factor of anti-drug norms and indirectly affect adolescents alcohol and cigarette use. These findings support the premise that strengthening parenting factors coupled with youth’s refusal skills are distal factors that contribute to predicting lower adolescent alcohol and cigarette use. Influencing anti-alcohol norms appear to play a more prominent role in explaining the reduction in amount and frequency of alcohol use, than the strength of cigarette norms on cigarette use. This may be a reflection of societal and adult norms surrounding the acceptability of alcohol use compared to the overwhelming negative attitudes towards cigarette use – youth in this study have stronger anti-cigarette norms at wave 1 compared to anti-alcohol norms. These indirect effects of the interventions on youth substance may imply a shift in parents’ communication about and modeling of alcohol use to youth. The direct effects of kiR and FPNG appear only for cigarette use. It is hypothesized that with time, direct effects will be identified for alcohol.

From an ecodevelopmental perspective, involving the family in this youth prevention intervention boosts the effects of already proven efficacious youth-only interventions such as kiR. Future research should fully examine how the FPNG and kiR can be fully optimized using the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) (Collins, Murphy, & Strecher, 2007). The MOST process would lend itself well to understanding how the specific intervention and delivery components are working well to bolster the effects of kiR and to reduce typical adolescent substance use trajectories. Typically, anti-drug norms decrease and substance use increases over adolescence; and peaks when individuals are in their 20s. Results using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health indicate that during early adolescents Latino youth have the highest levels of substance use, which increase over time (Chen & Jacobson, 2012). Unfortunately, in both the original test of kiR as well as in the current study, the interventions, kiR and FPNG, cannot altogether stop these developmental trajectories. This is evident when growth curve analyses were run independently. For example, when examining alcohol use, the C group had the greatest increases in alcohol use over time. Although the Y group had steeper alcohol trajectories than the PY group, these trajectories were not significantly different. Thus, when FPNG is added to kiR, the typical developmental trajectory is augmented, but not halted all together. These results, with only three time points, indicate a need for longer follow-up in order to better understand the mechanisms that make synchronized interventions more effective and to gauge when the trajectory of the PY group becomes significantly different from the Y group. Furthermore, these findings are speaking to the reduction in substance use for the PY youth over above the Y group. Thus, the findings of the present study only allow researchers to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of a synchronized youth and parent drug use prevention intervention in reducing alcohol and cigarette use compared to youth who received the youth only intervention.

This study has other limitations. The mediating variables, anti-drug norms, were measured at the same time point as the variable of interest in this study, substance use; and as a single item measure. It should be noted that the questions related to anti-drug norms were also examined at W2; however no changes were detected, suggesting that changes in both anti-drug norms and actual substance use are taking place during the 12 months between W2 and W3. While it is possible that the directionality of the mediation could be reversed, our theoretical models of primary socialization theory and the theory of planned behavior suggest that norms are changed first, followed by behavior. These models do not include attitudes, perceptions, or intentions to use substances, and are only testing one aspect of the theory of planned behavior. Future studies should collect additional time points to gauge the timing of changes in anti-drug norms and substance use; and include attitudes, perceptions, and intentions to use substances to gain a richer understanding of the mechanisms at work. Because the anti-drug norms are single-item measures, this study can only speak to the concrete construct of the acceptability of alcohol (cigarette) use and cannot gauge different facets or dimensions of anti-drug norms across multiple substances simultaneously. However, it should be noted that results from the Monitoring the Future National Survey, acceptability of use varies for different substances (Johnston et al., 2013), indicating the need to analyze substance-specific norms. In addition, this study did not obtain formal fidelity measures or independent validation of actual substance use through a urinalysis. There is no way to definitively determine if the changes seen in substance use at W3 are actual use or because the intervention changed how youth view their substance use behavior. There has been, however, a prior demonstrated correspondence between urinalaysis and Latino youth’s self-report of substance use (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005).

Furthermore, while parenting variables have been shown to change as a result of participation in FPNG, the data collection points, only over 18-months, might not fully capture the impact of the synchronized parent and youth interventions on adolescent outcomes. As was found by the Familias Unidas trials, we expect that parenting effects on the youth take time and will appear a year or longer post-intervention (Perrino et al., 2014). While no causal conclusions can be made about the entire indirect paths between participation in kiR and FPNG and reducing adolescent substance use, these results point towards the need for a longer data collection time frame in order to understand the full and complex suggested mediated pathways, particularly how parents are strengthening parenting skills and family functioning which, in turn, influences youth substance use. Another limitation is that the majority of the adult participants were female and lived in predominately Latino neighborhoods, in a unique urban socio-political context, with the parents speaking only Spanish. A multisite, multi-city study is needed in order to be able to generalize to a broader range of Latino families. Because parent-child communication regarding substance use is gendered, with mothers typically engaging in more conversations (Kam & Yang, 2013), having mothers as the majority of participants may have produced stronger results than if the FPNG groups were more evenly distributed. Future research should examine if there are gender differences between mothers and fathers. However, even given these limitations, it is notable that these results emerged to highlight the results on youth substance use 18 months after receiving the intervention when adding a culturally grounded parenting component. A future cost-effectiveness analysis of the synchronized parent/child intervention could help further elucidate the value added of a parent component to an already efficacious youth intervention.

Conclusions

The current findings provide confirmation for the implementation of culturally specific family-centered interventions to complement adolescent school-based substance use prevention interventions with Latino youth. Adolescent normative beliefs can be influenced, changed, shaped, and altered through synchronized culturally grounded parent and youth interventions and can play an important role in reducing adolescent substance use. These results shine additional light on possible intervention pathways to successfully reduce adolescent substance use and attend to the unique qualities that characterize Latino families.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMHD or the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational, Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health. 2011;26:1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effects of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamaca-Colbert M, Gayles J, Lara R. Family correlates of adjustment profiles in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2011;33:123–151. doi: 10.1177/0739986311403724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, McNair L, Brown AC, Chen YF. The strong African American families program: prevention of youths' high-risk behavior and a test of a model of change. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:1–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro F, Stein J, Bentler P. Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette use and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:265–292. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson T, Cardemil E. Parent-child communication and parental involvement in Latino adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Holleran L, Rugh D, MacMaster Substance abuse among U.S. Latinos: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(4):404. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Jacobs-Carter S. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. New York, NY: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Forster JL. Adolescent smoking behavior: measures of social norms. American journal of preventive medicine. 2003;25(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin'it REAL: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of pre-adolescents of the southwest. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:119–142. doi: 10.2190/DXB9-1V2P-C27J-V69V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harakeh Z, Scholte R, Vermulst A, Vries H, Engels R. Parental factors and adolescents’ smoking behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P, Miller-Day M. Culturally grounded substance use prevention: an evaluation of the keepin'it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4:233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kam JA, Yang S. Explicating how parent–child communication increases Latino and European American Early adolescents’ intentions to intervene in a friend’s substance use. Prevention Science. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P. The contributions of mothers and fathers to the intergenerational transmission of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KJ, Comello MLG, Hunn LC. Parent-child communication, perceived sanctions against drug use, and youth drug involvement. Adolescence. 2002;37:775–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Li G, Hasin D. Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: the influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1304–1313. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Dustman P, Wagstaff DA, Hecht ML. Mexican/Mexican American adolescents and keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based substance use prevention program. Children and Schools. 2005;27:133–145. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Molgaard V, Spoth R. The Strengthening Families Program for the prevention of delinquency and drug use. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. 1996;3:241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. keepin’it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR Associates; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, Dran D. Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5(1–2):85–111. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Nagoshi J, Parsai M, Castro F. The influence of linguistic acculturation and parental monitoring on the substance use of Mexican-heritage adolescents in predominately Mexican enclaves in the Southwest US. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2012;11:226–241. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2012.701566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Williams L, Ayers SL, Booth JM. Familias: Preparando la Nueva Generación: A randomized control trial testing the effects on positive parenting practices. Research on Social Work Practice. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1049731513498828. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR. Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations. 2006;55(3):306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. Substance use & misuse. 1998;33:995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJ, Newman FL, Briones E, Prado G, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: The efficacy of an intervention to promote parental investment in Hispanic immigrant families. Prevention Science. 2003;4:189–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1024601906942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai MB, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, Valdez H. Using community based participatory research to create a culturally grounded intervention for parents and youth to prevent risky behaviors. Prevention Science. 2011;12:34–47. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GK, Cruess D. The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the United States. Health Psychology Review. 2014;8:95–127. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.569936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Brincks A, Howe G, Brown CH. Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prevention Science. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Gonzalez-Soldevilla A, Pantin G, Szapocznik J. The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:81–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, McCollister K. The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: Main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, Briones E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development. 2006;49:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Trudeau L, Guyll M, Shin C, Redmond C. Universal intervention effects on substance use among young adults mediated by delayed adolescent substance initiation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:620–632. doi: 10.1037/a0016029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing risk and protection for drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug Abuse: Origins and Interventions. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Voisine S, Parsai M, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. Effects of parental monitoring, permissiveness, and injunctive norms on substance use among Mexican and Mexican American adolescents. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2008;89(2):264–273. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden B, Iacono WG, McGue M. Trajectories of change in adolescent substance use and symptomatology: Impact of paternal and maternal substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(1):35–43. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Muthen B, Alwin DF, Summers G. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology. 1977;8:84–136. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Ayers SL, Garvey M, Marsiglia FF, Castro FG. The efficacy of a culturally-based parenting intervention: Strengthening open communication between Mexican-heritage parents and their adolescent children. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2012;3(4):296–307. doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Marsiglia FF, Baldwin A, Ayers SL. Unintended effects of an intervention supporting Mexican-heritage youth: Decreased parent heavy drinking. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1049731514524030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]