Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most aggressive and lethal type of brain tumor. Both therapeutic resistance and restricted permeation of drugs across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) play a major role in the poor prognosis of GBM patients. Accumulated evidence suggests that in many human cancers, including GBM, therapeutic resistance can be attributed to a small fraction of cancer cells known as cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs have been shown to have stem cell-like properties that enable them to evade traditional cytotoxic therapies, and so new CSC-directed anti-cancer therapies are needed. Nanoparticles have been designed to selectively deliver payloads to relevant target cells in the body, and there is considerable interest in the use of nanoparticles for CSC-directed anti-cancer therapies. Recent advances in the field of nanomedicine offer new possibilities for overcoming CSC-mediated therapeutic resistance and thus significantly improving management of GBM. In this review, we will examine the current nanomedicine approaches for targeting CSCs and their therapeutic implications. The inhibitory effect of various nanoparticle-based drug delivery system towards CSCs in GBM tumors is the primary focus of this review.

Keywords: Targeted nanomedicine, Glioblastoma multiforme, Cancer stem cells, Blood–brain barrier, Therapeutic resistance, Chemosensitization

1. Introduction

High-grade malignant glioma, glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is the most aggressive and lethal form of brain tumor characterized by extensive infiltration into the surrounding brain parenchyma [1]. High rates of recurrence, overall resistance to therapy, devastating neurological deterioration, and dismal survival rates make GBM one of the most dreaded cancers [2]. Under the standard treatment regimen, which includes resection followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy [typically temozolomide (TMZ)], GBM patients can expect a median survival of 14.6 months. Less than 5% of patients live longer than 5 years [3]. This poor prognosis is due primarily to: A) the highly aggressive and infiltrative nature of GBM tumors resulting in incomplete resection; B) limited delivery of therapeutics across the blood–brain barrier (BBB); and C) therapeutic resistance which results in tumor recurrence [4]. Concurrent treatment with the alkylating agent TMZ and radiation has demonstrated only limited efficacy in newly diagnosed GBM patients with an extension of median survival by just 2.5 months when compared to radiation therapy alone [5]. Furthermore, even in patients with strong initial responses, the majority of these patients later develop recurrences wherein TMZ treatment is largely ineffective [6]. Thus, there is a critical need for means to overcome this drug resistance and improve the efficacy of current GBM therapies.

2. Chemoresistance of GBM CSCs

The cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis suggests that tumors are initiated from, and maintained by, a small fraction of tumor cells that have stem cell-like properties including expression of stem cell markers, long term self-renewal, and the ability to reproduce the original parent tumor when grown as in vivo xenografts [7]. Stem cell-like properties afford resistance to cytotoxic therapies and allow CSCs to continue to differentiate into rapidly proliferating progenitor-like and more differentiated tumor cells (non-CSCs). This cellular hierarchy has been identified in GBM tumors as well as many human cancers including leukemia, breast, colon, lung, and prostate [8].

It has been suggested that CSCs might be the postulated mediator of therapeutic resistance because their cellular properties give them the ability to be refractory to current treatment strategies [9,10]. In GBM tumors, CSCs tend to be more resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy than non-CSCs [11,12]. Recent studies have shown CSCs to have intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy [10,13]. For example, the increased transcription of anti-apoptotic genes and efflux transporters was reported in CD133-positive GBM CSCs [14,15]. They also possess increased abilities to repair DNA damage and to promote angiogenesis [16,17]. Therefore, although anti-cancer therapies could effectively debulk the tumor mass, surviving CSCs can reinitiate tumor formation [18]. Such recurrences are often metastatic and more resistant to therapies. Unfortunately, the majority of currently existing cancer therapies – including hormonal, radiation, and chemotherapy – may not efficiently eliminate CSCs. Thus, given their critical role in tumor initiation, maintenance, and recurrence, a great deal of effort is currently focused on the therapeutic targeting of CSCs as a new strategy in drug design for cancer treatment and the prevention of recurrence [10–12,19]. However, a formidable challenge in CSC-specific therapies involves the development of effective means for specifically delivering the therapeutics to the CSCs.

3. Emerging role of nanomedicine in anti-cancer therapies

Owing to rapid advances in protein engineering and materials sciences, considerable progress has been made recently in the field of nanomedicine to develop novel nanoscale strategies for cancer diagnosis and treatment [20]. Many different types of delivery systems have been developed including liposome, polymers, and inorganic nanoparticles (NPs). Approximately 150 drugs are in development for cancer treatment based on nanotechnology [21]. Some of them are currently undergoing clinical trials and over 20 therapeutic nanomedicines have been approved for clinical use [22]. Compared to conventional drug formulations, carefully designed nano-formulations can offer significant advantages such as increased drug solubility, extended retention time and stability in the body, selective targeting, and reduced side effects while delivering treatments that are more potent [21]. Another advantage is facilitation of drug delivery across biological barriers, such as BBB which limits access to brain tumors [4]. Additionally, NPs can also facilitate a combination of diagnostics with therapeutics (theranostics) for cancer [23]. Various nanomedicine strategies are being applied to enhance the therapeutic response in drug-resistant tumors including strategies for anti-CSC therapy by directly targeting them for elimination.

4. Targeted drug delivery using nanoparticles: passive vs active

Delivering effective quantities of drug into the right target cells through clinically feasible methods represents a major challenge for the successful development of cancer nanomedicines. Various biological barriers (such as mucosal and BBB) significantly hamper in vivo delivery of drugs to the tumor site [24]. To reach tumor by systemic administration, NPs have to travel through the blood stream, extravasate through the vessels, diffuse through the extracellular matrix, penetrate the tumor cell membranes, and be released into the cytoplasm. Thus, a series of biological barriers stands between systemically administered NPs and their target site inside the cells [25]. Nanodelivery platforms designed to overcome such barriers and can be divided into two classes.

4.1. Passive targeting

As a result of rapid and defective angiogenesis, blood vessels in tumors may have a leaky endothelium failing in its normal barrier function thus allowing entry of macromolecules (up to 400 nm in size) [26]. When administered intravenously, NPs passively extravasate into tumor tissue through the leaky vasculature, accumulate in the tumor bed due to dysfunctional lymphatic drainage, and release therapeutic payloads into the vicinity of tumor cells. This process is known as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [27]. All nanomedicines that are currently approved for clinical use in the treatment of solid tumors rely on the EPR effect [20]. However, the passive targeting strategies suffer from several limitations because the EPR effect depends entirely on the diffusion of drugs, and it is difficult to control diffusion and some drugs cannot diffuse efficiently. Moreover, the permeability of tumor vessels may not be the same throughout a single tumor, and certain tumors may not even exhibit the EPR effect at all [28]. In the case of brain tumors, the EPR effect is very unlikely to be efficient due to a dense brain matrix impeding diffusion and the elevated interstitial fluid pressure [1].

4.2. Active targeting

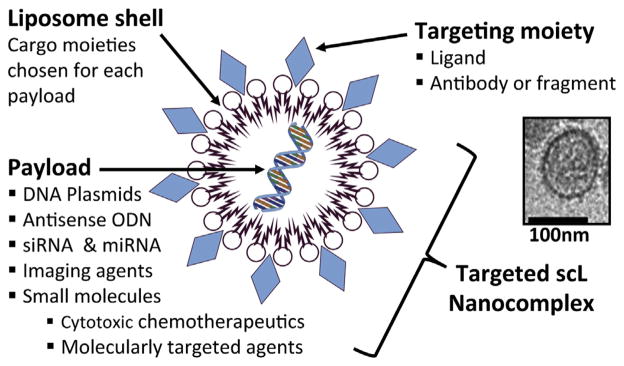

To overcome the above limitations, active targeting strategies have incorporated onto NPs affinity molecules such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers that bind to antigens or receptors on the target cells to enhance the therapeutic efficacy by increasing cellular uptake and accumulation [20,29]. Generally, actively targeted NPs comprise a targeting moiety and a cargo-carrying moiety (Fig. 1). Payloads can be packaged inside the cargo moiety, and the surface of these NPs can be engineered to incorporate the targeting moiety. After binding of the NPs to certain receptors, the NPs can be internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis thereby increasing cellular uptake of their payload. Some receptors rapidly recycle to the cell surface to allow repeated cycles of uptake. Another important consideration for targeted NPs is to engineer the targeting moiety to enable payload ‘piggybacking’ without disrupting the normal receptor-binding properties [25]. Recent identification of putative markers of CSCs has led to a quest for methods to deliver therapeutic agents to CSCs in various types of cancer using these markers. While the relevance of putative CSC surface markers remains controversial [11,30], a few studies have reported targeting of CSCs based on the distinct stem cell surface antigens [2,31–33].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of targeted scL nanocomplex. scL is comprised of a targeting and cargo moiety. Various payloads can be packaged inside a cargo moiety made of cationic liposome shell. TfRscFv was incorporated on the surface of scL as a cancer cell- and CSC-targeting moiety to form nano-sized complexes. A representative electron microscopic image of scL complex is shown. The scale bar represents 100 nm.

5. Crossing the BBB: a challenge for GBM therapy

The BBB is a highly selective diffusion barrier that protects the brain from toxins and other compounds from blood [4]. However, a consequence of this protection is that entry of therapeutic molecules from blood to brain is also impeded [34]. To address this issue, conventional approaches utilized injection of therapeutics directly into the brain through stereotactic surgery or employed passive targeting based on the EPR effect. In GBM, a disruption of BBB by the primary tumor sites is often observed [35]. This altered BBB allows passive accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs in the vicinity of the disruption [36]. However, the degree of BBB disruption varies depending on the region of the GBM tumors and may be negligible for certain tumors. Because BBB is intact near the growing edge of the infiltrative tumor area where the invasive tumor cells may reside [37], the infiltrating tumor cells cannot be reached efficiently by passive targeting [38,39]. Because isolated CSCs have been identified in the infiltrative peritumoral parenchyma of GBM [40], it is necessary to have a more effective means to transport therapeutic molecules across the BBB.

Strategies have been proposed for CNS drug delivery involving mechanical or chemical disruptions of the BBB by MRI-guided focused ultrasound [41], convection enhanced diffusion [42], microdialysis catheter [43], hyperosmotic agents [44], hydrophilic surfactants such as polysorbate 80 [45,46], or chemical modulators of blood vessels [47]. Clearly, a general disruption of the BBB to allow therapeutic agents to enter the brain would compromise the normal protective role of the BBB. Moreover, these approaches to disrupt the BBB have resulted in minimal therapeutic improvements generally speaking since the drugs and/or particles would still need to penetrate the brain parenchyma and effectively reach their target cell populations [4].

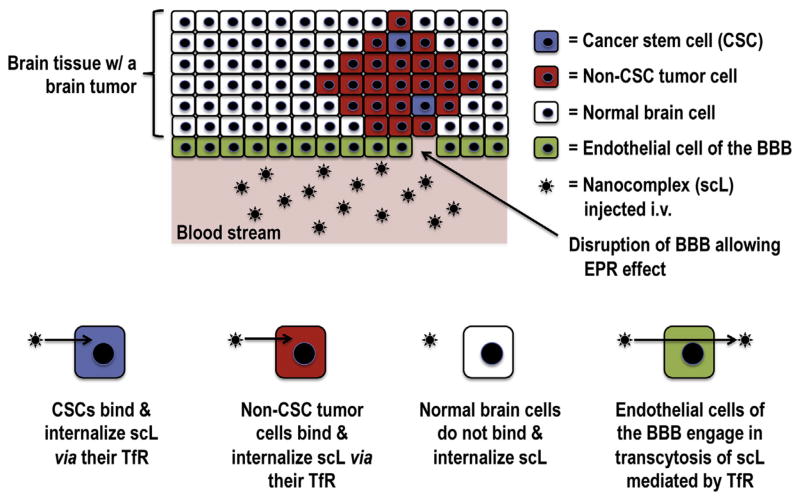

Nanomedicines relying on receptor-mediated transcytosis might facilitate more efficient entry of therapeutic molecules across the BBB with deeper tumor penetration [48]. Various receptor and/ or transporter systems already exist on the BBB including glucose transporters, insulin receptors, and transferrin receptors (TfR) normally used for iron delivery to the brain via its ligand, diferric transferrin. Antibodies or ligands that bind to TfR [6,48], glutathione receptor [49], and insulin receptor [50] have been reported to facilitate transcytosis of NPs via binding to these receptors on endothelial cells [51]. In a study using dendrimer NPs conjugated with transferrin (Tf), increased accumulation of tamoxifen in glioma cells were observed in an in vitro BBB model [52]. In our previous study, we demonstrated that the systemically administered TfR-binding NPs (designated as scL) are able to cross the BBB via transcytosis and efficiently deliver the payloads to intracranial tumors (Fig. 2) [48]. In our NPs, an anti-TfR single-chain antibody fragment (TfRscFv) was used as a targeting moiety. After binding to TfR on cerebral endothelial cells, scL actively traverses the BBB via receptor-mediated transcytosis. The TfRscFv has advantages in human use over the Tf molecule itself or a full-length monoclonal antibody (MAb) against TfR, namely: A) the small size (~28 kDa) of the TfRscFv can maintain the nanosize of the complex; B) the recombinant nature of TfRscFv has practical advantages for large-scale production, which will ultimately be required for commercialization or the proposed therapy; C) its recombinant nature (as opposed to a blood product like Tf) also presents no issues related to potential contamination with blood borne pathogens; and D) because TfRscFv lacks the Fc region of the MAb, non-antigen-specific binding through Fc receptors is eliminated.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of active targeting of CSCs and non-CSC tumor cells using scL nanocomplex. In the blood stream, scL can either actively transcytose endothelial cells mediated by TfR or passively extravasate through the disrupted BBB allowing the EPR effect. Once crossing the BBB, scL binds to TfR on the surface of non-CSC tumor cells and CSCs, but not normal brain cells. After receptor binding, scL-receptor complex readily internalizes via receptor-mediated endocytosis.

6. Anti-CSC nanomedicine in GBM

Although there are numerous studies reporting the potential of nanomedicines in GBM therapy, only a few address the targeting of CSCs. One example of a CSC-directed therapy involves cationic polyurethane-short branch polyethylenimine (PU-PEI) NPs that delivers plasmid DNA encoding a tumor-suppressive microRNA145 (miR145) [53]. This study showed radiosensitization and chemosensitization of CSC-derived brain tumors and prolongation of animal survival after local intracranial injection of PU-PEI-miR145 NPs. Although this NP lacks a CSC-targeting moiety, reduction of CSC-like properties was observed because miR145 down-modulated the expression of Oct4 and Sox2 genes related stemness. However, the absence of active CSC-targeting and the requirement for intracranial administration will likely be hurdles for this delivery system in translation to the clinic.

A nanomedicine has been described employing a CD133 MAb recognizing the CSC surface marker CD133 as a targeting moiety [2]. In this proof of principal study, photothermal therapy using single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) conjugated with anti-CD133 MAbs (CDSWNTs) demonstrated a selective lysis of CD133-positive GBM CSCs, while CD133-negative GBM cells remained intact in vitro. In the same study, inhibition of tumor growth was also observed after near-infrared laser irradiation of subcutaneous xenograft tumors derived from CDSWNTs-laden, CD133-positive GBM CSCs. This study demonstrated the concept of targeted elimination of CSCs using a CSC-targeting nanomedicine. It is noteworthy that this particular study used an ectopic GBM tumor model and did not assess systemic delivery of the nanomedicine.

It is plausible that the depletion of CSCs may not be sufficient to eliminate tumors if the remaining differentiated tumor cells are still capable of sustaining growth in a tumor mass [8,54]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that GBM non-CSCs may have the plasticity to dedifferentiate into GBM CSCs in response to microenvironment stresses such as hypoxia or radiation [55,56]. Therefore, a more effective therapeutic approach would be to target both CSC and non-CSC populations using a common target [e.g., TfR or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)].

Being associated with tumorigenesis and aggressive phenotypes, both wild-type EGFR and the EGFRvIII deletion mutant have been major targets for GBM therapy. However, clinical trials of EGFR- and EGFRvIII-targeted therapies yielded unsatisfactory results [57]. EGFR is overexpressed in the majority of GBM tumors including some of the CSC populations. In a recent study, a CSC-targeted therapy was tested that utilizes cetuximab that binds both EGFR and the EGFRvIII deletion mutant. Cetuximab was conjugated to iron-oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), and cetuximab-IONPs were infused by intratumoral convection-enhanced delivery in an orthotopic rodent GBM model [58]. Extended survival was observed in animals treated with cetuximab-IONPs compared with cetuximab-treated animals, demonstrating in vivo efficacy of the anti-EGF nanomedicine in GBM tumors. However, the fate of CSCs and the molecular basis for the observed therapeutic benefits are still unclear in this study.

Another approach has used either the ligand [diferric transferrin (Tf)] or antibodies against TfR, since various types of cancer cells display elevated TfR expression [59]. Once ligand (or antibody) is bound to the TfR, the receptor-ligand (or receptor-antibody) complex is internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Importantly, we have observed that TfRs are overexpressed on both CSCs and non-CSCs in various types of cancer including GBM [8]. Thus, the TfR is an attractive target for both anti-CSC and anti-cancer therapy in GBM more broadly.

One example is Tf-conjugated lipopolyplex NPs (Tf-NPs). In vitro treatment of CSC-enriched GBM tumor-spheres with Tf-NPs delivering miR1 resulted in significant inhibition of cell migration and expressions of EGFR and MET [60]. However, systemic treatment with Tf-NP-miR1 was not tested to assess in vivo targeting of GBM CSCs.

Employing an anti-TfR single-chain antibody fragment as a targeting moiety, we have tested whether TfR-binding scL NPs can target both tumor cells and CSCs. In vitro and in vivo targeting studies demonstrated that scL NPs can cross the BBB via transcytosis and efficiently deliver payloads into both CSC and non-CSC populations in GBM (Fig. 2) [8,48]. This scL nanodelivery platform is currently in multiple clinical trials. A systemically administered tumor- and CSC-targeted nanocomplex (in a product called SGT-53) is capable of delivering the exogenous wild-type tumor suppressor gene p53 across the BBB and results in sensitization of highly TMZ-resistant GBM tumors to TMZ and improved survival in an rodent model [48]. Furthermore, SGT-53 treatment in combination with TMZ resulted in extensive apoptosis of CD133-positive CSCs [48]. In the follow up study, we also demonstrated that SGT-53 could inhibit development of TMZ resistance in TMZ-sensitive GBM [6]. These results suggest that combining CSC-targeting SGT-53 with conventional TMZ treatment could limit the development of, and overcome TMZ resistance, thereby prolonging TMZ’s anti-tumor effect to yield what could be a much more effective therapy for GBM. Continuing advances in the therapeutic delivery methods raise hope that new innovative nanomedicines might eventually provide effective novel therapies against GBM. SGT-53 is now being tested in a clinical trial for recurrent glioblastoma in combination with TMZ (Clinical-Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02340156).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Celia E. Reynolds for her editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript. This study was supported in part by NCI grant 5R01CA132012-02 (EHC), a research grant from SynerGene Therapeutics Inc. (KFP), and National Foundation for Cancer Research grant HU0001 (EHC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Drs. Chang, Pirollo, and Kim are three of the inventors of the described technology, for which several patents owned by Georgetown University have been issued. The patents have been licensed to SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. for commercial development. Dr. Chang owns equity interests in SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. and serves as a non-paid scientific consultant to SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Harford serves as salaried President & CEO of SynerGene Therapeutics and own stock in same.

Transparency document

Transparency document related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.137.

References

- 1.Sehedic D, Cikankowitz A, Hindre F, et al. Nanomedicine to overcome radioresistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells and surviving clones. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:236–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang CH, Chiou SH, Chou CP, et al. Photothermolysis of glioblastoma stem-like cells targeted by carbon nanotubes conjugated with CD133 monoclonal antibody. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou LC, Veeravagu A, Hsu AR, Tse VC. Recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a review of natural history and management options. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodworth GF, Dunn GP, Nance EA, et al. Emerging insights into barriers to effective brain tumor therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2014;4:126. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain MC. Temozolomide: therapeutic limitations in the treatment of adult high-grade gliomas. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:1537–1544. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SS, Rait A, Kim E, et al. A tumor-targeting p53 nanodelivery system limits chemoresistance to temozolomide prolonging survival in a mouse model of glioblastoma multiforme. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SS, Rait A, Rubab F, et al. The clinical potential of targeted nanomedicine: delivering to cancer stem-like cells. Mol Ther. 2014;22:278–291. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundar SJ, Hsieh JK, Manjila S, et al. The role of cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37:E6. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.FOCUS14494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pointer KB, Clark PA, Zorniak M, et al. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells: biomarker and therapeutic advances. Neurochem Int. 2014;71:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esparza R, Azad TD, Feroze AH, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells and stem cell-targeting immunotherapies. J Neurooncol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1729-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez YP, Weatherbee JL, Wheelhouse RT, Ross AH. Glioblastoma multiforme therapy and mechanisms of resistance. Pharm Basel. 2013;6:1475–1506. doi: 10.3390/ph6121475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinogradov S, Wei X. Cancer stem cells and drug resistance: the potential of nanomedicine. Nanomedicine Lond. 2012;7:597–615. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho DY, Lin SZ, Yang WK, et al. The role of cancer stem cells (CD133(+)) in malignant gliomas. Cell Transpl. 2011;20:121–125. doi: 10.3727/096368910X532774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7843–7848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Labagnara M, Friedman M, et al. Glioblastoma: molecular pathways, stem cells and therapeutic targets. Cancers Basel. 2015;7:538–555. doi: 10.3390/cancers7020538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson M, Hassiotou F, Nowak A. Glioblastoma stem-like cells: at the root of tumor recurrence and a therapeutic target. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:177–185. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, et al. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain KK. Advances in the field of nanooncology. BMC Med. 2010;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallidi S, Watanabe K, Timerman D, et al. Prediction of tumor recurrence and therapy monitoring using ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging. Theranostics. 2015;5:289–301. doi: 10.7150/thno.10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alonso MJ. Nanomedicines for overcoming biological barriers. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SS, Garg H, Joshi A, Manjunath N. Strategies for targeted nonviral delivery of siRNAs in vivo. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, et al. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain RK. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Sci Am. 1994;271:58–65. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0794-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bamrungsap S, Zhao Z, Chen T, et al. Nanotechnology in therapeutics: a focus on nanoparticles as a drug delivery system. Nanomedicine Lond. 2012;7:1253–1271. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan CT. Cancer stem cells: controversial or just misunderstood? Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, et al. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1167–1174. doi: 10.1038/nm1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lang J, Lan X, Liu Y, et al. Targeting cancer stem cells with an (131)I-labeled anti-AC133 monoclonal antibody in human colorectal cancer xenografts. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naujokat C. Monoclonal antibodies against human cancer stem cells. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:290–308. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar P, Wu H, McBride JL, et al. Transvascular delivery of small interfering RNA to the central nervous system. Nature. 2007;448:39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long DM. Capillary ultrastructure and the blood–brain barrier in human malignant brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:127–144. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.2.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhowmik A, Khan R, Ghosh MK. Blood brain barrier: a challenge for effectual therapy of brain tumors. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:320941. doi: 10.1155/2015/320941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juillerat-Jeanneret L. The targeted delivery of cancer drugs across the blood–brain barrier: chemical modifications of drugs or drug-nanoparticles? Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noell S, Mayer D, Strauss WS, et al. Selective enrichment of hypericin in malignant glioma: pioneering in vivo results. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1343–1348. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glas M, Rath BH, Simon M, et al. Residual tumor cells are unique cellular targets in glioblastoma. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:264–269. doi: 10.1002/ana.22036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDannold N, Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, Livingstone MS. Temporary disruption of the blood–brain barrier by use of ultrasound and microbubbles: safety and efficacy evaluation in rhesus macaques. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3652–3663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allard E, Passirani C, Benoit JP. Convection-enhanced delivery of nanocarriers for the treatment of brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2302–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Lange EC, de Boer BA, Breimer DD. Microdialysis for pharmacokinetic analysis of drug transport to the brain. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1999;36:211–227. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyagami M, Tsubokawa T, Tazoe M, Kagawa Y. Intra-arterial ACNU chemotherapy employing 20% mannitol osmotic blood–brain barrier disruption for malignant brain tumors. Neurol Med Chir Tokyo. 1990;30:582–590. doi: 10.2176/nmc.30.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreuter J. Nanoparticulate systems for brain delivery of drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47:65–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calvo P, Gouritin B, Chacun H, et al. Long-circulating PEGylated polycyanoacrylate nanoparticles as new drug carrier for brain delivery. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1157–1166. doi: 10.1023/a:1010931127745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dean RL, Emerich DF, Hasler BP, Bartus RT. Cereport (RMP-7) increases carboplatin levels in brain tumors after pretreatment with dexamethasone. Neuro Oncol. 1999;1:268–274. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/1.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SS, Rait A, Kim E, et al. A nanoparticle carrying the p53 gene targets tumors including cancer stem cells, sensitizes glioblastoma to chemotherapy and improves survival. ACS Nano. 2014;8:5494–5514. doi: 10.1021/nn5014484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birngruber T, Raml R, Gladdines W, et al. Enhanced doxorubicin delivery to the brain administered through glutathione PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (2B3-101) as compared with generic Caelyx, (®)/Doxil(®)–a cerebral open flow microperfusion pilot study. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103:1945–1948. doi: 10.1002/jps.23994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boado RJ, Lu JZ, Hui EK, et al. Pharmacokinetics and brain uptake in the rhesus monkey of a fusion protein of arylsulfatase a and a monoclonal antibody against the human insulin receptor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/bit.24795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendricks BK, Cohen-Gadol AA, Miller JC. Novel delivery methods bypassing the blood–brain and blood-tumor barriers. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38:E10. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, He H, Jia X, et al. A dual-targeting nanocarrier based on poly(amidoamine) dendrimers conjugated with transferrin and tamoxifen for treating brain gliomas. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3899–3908. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang YP, Chien Y, Chiou GY, et al. Inhibition of cancer stem cell-like properties and reduced chemoradioresistance of glioblastoma using micro-RNA145 with cationic polyurethane-short branch PEI. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1462–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beier D, Schulz JB, Beier CP. Chemoresistance of glioblastoma cancer stem cells–much more complex than expected. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berezovsky AD, Poisson LM, Cherba D, et al. Sox2 promotes malignancy in glioblastoma by regulating plasticity and astrocytic differentiation. Neoplasia. 2014;16:193–206. 206 e119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jun HJ, Bronson RT, Charest A. Inhibition of EGFR induces a c-MET-driven stem cell population in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2014;32:338–348. doi: 10.1002/stem.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lo HW. EGFR-targeted therapy in malignant glioma: novel aspects and mechanisms of drug resistance. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2010;3:37–52. doi: 10.2174/1874467211003010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaluzova M, Bouras A, Machaidze R, Hadjipanayis CG. Targeted therapy of glioblastoma stem-like cells and tumor non-stem cells using cetuximab-conjugated iron-oxide nanoparticles. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8788–8806. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyamoto T, Tanaka N, Eishi Y, Amagasa T. Transferrin receptor in oral tumors. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:430–433. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, Huang X, Yang Z, et al. Targeted delivery of tumor suppressor microRNA-1 by transferrin-conjugated lipopolyplex nanoparticles to patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2014;15:839–846. doi: 10.2174/1389201015666141031105234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.